1. Introduction

Underground pipelines represent a core component of modern civil infrastructure, serving as vital “lifelines” for transporting water, wastewater, oil, and natural gas over long distances. Maintaining their durability and structural soundness is crucial for safeguarding public health, supporting economic activity, and protecting the environment. Although buried infrastructure plays a critical role, it remains vulnerable to a variety of geotechnical and hydraulic threats, with soil erosion from water exfiltration representing one of the most severe and complex hazards. When leakage or defects occur in pipelines, escaping water can gradually detach surrounding soil particles, generate subsurface voids, and compromise ground stability. This progressive process may ultimately result in pipeline distress, expressed through sinkhole formation, ground subsidence, structural displacement, or premature system failure [

1,

2].

A substantial body of experimental research has been devoted to understanding the mechanisms of soil erosion, cavity formation, and ground collapse triggered by water exfiltration from defective buried pipelines. Physical model testing remains an indispensable tool for visualizing the initiation and progression of internal erosion processes, validating theoretical models, and identifying the influence of key hydraulic and geometric parameters.

Liu et al. [

3] performed a series of laboratory model experiments to investigate the failure evolution of shallowly buried soils subjected to pipe leakage. Their study systematically evaluated how hydraulic head, defect size, and burial depth affect the transition from localized erosion to full-scale collapse. Three distinct erosion modes were identified: (1) minor disturbance, (2) cavity formation with gradual expansion, and (3) complete soil fluidization and collapse. They reported that when the ratio of internal water pressure head to burial depth exceeded approximately two, soil fluidization became inevitable. The tests also showed that larger leakage openings and higher-pressure heads promoted faster cavity development and more extensive ground deformation.

In a complementary study, Mao et al. [

4] examined the erosion and scouring behavior of cohesive soil subgrades under continuous water leakage using a controlled leakage erosion-damage soil test setup. Their results highlighted the strong resistance of cohesive soils against hydraulic detachment, where erosion rate decreased sharply with reduced flow velocity and smaller defect openings. The findings underscored that cohesive fine particles enhance soil stability through matrix suction and interparticle bonding significantly delaying the onset of internal erosion. However, once critical hydraulic gradients were reached, erosion propagated rapidly along preexisting weaknesses, leading to progressive cavity expansion and eventual surface settlement.

Other experimental investigations have focused on the role of particle size distribution and defect geometry in controlling erosion dynamics. Guo et al. [

5] utilized gap-graded glass beads to replicate natural soil heterogeneity and identified three primary erosion modes, clogging, partial erosion, and full erosion, governed by the proportion of fine particles and the number of infiltration–exfiltration cycles. They further derived a dimensionless parameter combining hydraulic and geometric factors, demonstrating that when this value exceeded approximately 1.75, the system transitioned into complete erosion after several cycles.

Collectively, these experimental studies have established the fundamental influence of hydraulic pressure, defect geometry, particle gradation, and soil cohesion on the evolution of internal erosion around buried pipes. Experimental efforts such as these have greatly advanced the understanding of soil–water interaction and subsurface instability near buried conduits. Laboratory tests have yielded important qualitative and quantitative information on erosion patterns, void formation, and sinkhole initiation under well-controlled conditions. However, while they provide valuable macroscopic observations, experimental setups often face limitations in capturing pore-scale flow behavior, interparticle stress redistribution, and long-term erosion kinetics. These constraints underscore the need for numerical modeling approaches, such as coupled CFD–DEM simulations, which can complement experimental findings by resolving the microscale mechanisms driving erosion and void formation [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

To address the limitations of traditional laboratory testing, numerical modeling has become a vital approach for investigating interactions between fluids and soil particles. Among the available computational techniques, the coupled CFD–DEM provides a versatile and detailed framework capable of representing multiphase erosion processes across diverse spatial and temporal scales [

1,

2,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Within this coupled modeling framework, the CFD component resolves the fluid flow field by numerically solving the Navier–Stokes equations, while the DEM component tracks the motion, interaction, and contact forces of individual soil particles. The integration of these two methods provides a detailed representation of fluid–solid interactions, enabling the analysis of erosion phenomena that encompass both large-scale flow behavior and particle-scale dynamics as the soil structure evolves over time.

Analytical and physics-based modeling of exfiltration-induced erosion has established key relationships that underpin contemporary CFD–DEM simulations. Using laboratory observations as constraints, Tang and co-authors [

6] formulated an analytical framework that links soil/water discharge to geometric and hydraulic controls. Their work shows that the soil-to-water flow–rate ratio scales exponentially with the ratio of defect size to particle size, largely independent of water level and defect location; this scaling is consistent with free-fall arch theory and provides a compact predictor for discharge partitioning under cohesionless conditions. They further proposed cavity-growth and kinematic formulations, derived from mass conservation and particle-velocity modeling, which estimate soil loss rate and through-defect velocities during erosion, and verified these models against laboratory measurements, including tests that varied defect position around the pipe circumference. Collectively, these results formalize how defect geometry and placement govern the width of the mobilized zone, erosion intensity, and the temporal evolution of the void, thereby offering closed-form guidance that CFD–DEM models can calibrate against and extend to 3D, transient conditions.

Complementary experimental–theoretical work on slot-type defects established additional scaling relevant to CFD–DEM. Building on granular-flow theory (e.g., Beverloo-type relations) and free-fall arch concepts, Tang et al. [

17] quantified how slot width, particle size, and defect position modulate discharge. They reported steady soil/water outflows until the eroded region intercepted the opening, documented a narrow-mobilized core above the defect bounded by slopes near the angle of repose, and demonstrated thresholds for jamming when the opening size (D) equals a few grain diameters (d). A simple analytical model was introduced to estimate coupled sand/water flow rates during erosion, capturing the competing roles of hydraulic drag and arching resistance near the outlet. These relations provide first-order constitutive targets (mobilized-zone size, velocity magnitude ranges, discharge trends with D/d and defect orientation) that CFD–DEM schemes can reproduce while resolving the pore-scale mechanics, fluid shear, porosity evolution, and contact force chains, beyond the reach of closed-form theory.

Together, these analytical developments supply (i) dimensionless predictors (e.g., exponential dependence of soil/water discharge on defect-to-particle size), (ii) cavity-growth relations grounded in conservation laws, and (iii) mechanistic interpretations of arching and mobilized-zone geometry. Modern CFD–DEM modeling builds directly on these insights to simulate two-way fluid–solid coupling, track porosity and stress redistribution, and visualize pathway formation from initial detachment to sustained transport—thereby generalizing the analytical results across defect positions, particle sizes, and pressure regimes, and enabling parametric exploration under realistic 3D boundary conditions.

Dai et al. [

11] carried out a combined experimental and numerical study to examine the mechanisms of ground collapse triggered by leakage from underground drainage pipes. A series of scaled laboratory experiments, complemented by three-dimensional CFD–DEM simulations, were used to replicate the initiation and evolution of subsurface cavities leading to surface failure. The progression of collapse was characterized by three distinct stages: (1) an initial period of structural stability, (2) gradual subsidence associated with the weakening of soil arching effects, and (3) final surface collapse as the supporting soil structure failed. The study identified groundwater level, defect aperture, and burial depth as key parameters governing the extent and rate of failure.

Experimental observations revealed that the resulting collapse pits were semi-elliptical in shape, with larger and deeper depressions forming when pipes were buried deeper or subjected to higher groundwater pressures. The numerical simulations successfully reproduced these behaviors, providing detailed visualization of particle-scale motion and the development and breakdown of soil arches, thereby clarifying the micromechanical processes controlling cavity formation. The analysis emphasized the dominant influence of seepage-induced erosion, as well as the cyclic creation and collapse of internal arches that govern the transition from gradual deformation to catastrophic failure. Strong agreement between the experimental results and CFD–DEM predictions validated the robustness of the coupled modeling framework in capturing seepage-driven ground instability and pipe-leakage-induced collapse phenomena.

Ibrahim and Meguid [

13] conducted a comprehensive numerical analysis using a coupled CFD–DEM modeling approach to investigate sand migration into damaged gravity pipelines under steady groundwater conditions. Their simulations examined the influence of groundwater head, defect size, crack inclination, and sand layer thickness on both the rate and magnitude of erosion. Findings showed that as the groundwater level increased, erosion accelerated rapidly until reaching a saturation limit, beyond which additional increases in hydraulic pressure produced negligible changes in erosion behavior. The study further demonstrated that defects located at the pipe crown caused the fastest onset of erosion, while inclined openings led to greater overall soil loss owing to enhanced particle transport along oblique flow paths. Conversely, changes in sand cover thickness had limited impact, as particle motion was largely controlled by a free-fall arching mechanism.

The researchers verified the dry-condition simulations through comparison with empirical formulations and subsequently derived simplified predictive relationships linking erosion magnitude to defect geometry, hydraulic head, and soil characteristics. These findings shed light on the hydromechanical mechanisms governing groundwater-driven soil loss and underscore the significance of key parameters, such as defect orientation and hydraulic boundary conditions, in evaluating the stability and erosion vulnerability of buried pipe systems.

Guo and Yu [

18] performed a comparative investigation of three prevalent CFD–DEM coupling schemes commonly applied to simulate soil surface erosion phenomena. Each scheme employed a different formulation of the fluid momentum equations, allowing for a systematic evaluation of their accuracy and computational behaviors under laminar flow conditions. Model validation began with the simulation of a single particle settling in fluid, which revealed minimal variation among the approaches when particle concentrations were low. However, when the models were extended to pipe flow scenarios involving dense particle–fluid interactions, clear differences emerged. These discrepancies were primarily attributed to variations in how each formulation handled fluid pressure distribution and porosity gradients within the computational domain. The findings highlighted that the assumptions embedded within each modeling approach critically influence the accuracy of fluid–particle interaction representation and the reliability of erosion predictions in multiphase flow environments.

Although numerous investigations have examined the influence of different factors on soil erosion near damaged underground pipelines subjected to groundwater exfiltration, the fundamental mechanisms governing erosion initiation and sinkhole development remain insufficiently understood. Key questions persist, such as: (1) What hydrogeological conditions trigger the onset of internal erosion? (2) How can the extent of soil loss induced by exfiltrating water be effectively quantified? (3) Which factors exert the most significant influence on the progression of erosion and subsequent ground instability?

In this research, a coupled CFD–DEM approach was utilized to analyze internal soil erosion mechanisms that occur around defective buried pipes subjected to water exfiltration. The primary goals of this research are to:

(1) Assess how exfiltration pressure affects the initiation, detachment, and transport rates of soil particles entering the pipe through a defect on pipe.

(2) Investigate the formation and temporal evolution of void zones generated by erosion within the surrounding soil under varying hydraulic gradients.

(3) Determine how defect size and particle diameter influence particle discharge behavior, velocity fields, and the progression of internal erosion.

(4) Validate the CFD–DEM coupling capability in capturing fluid–particle interactions, particle-scale motion, and the development of preferential flow paths associated with exfiltration-induced erosion.

Together, these objectives seek to deepen the understanding of erosion processes across multiple scales near buried infrastructures, while establishing a quantitative framework for evaluating erosion vulnerability and guiding the development of preventive measures to enhance pipeline stability and reduce the risk of ground deformation.

2. Materials and Methods

In this research, a coupled CFD–DEM model was established within the ANSYS simulation environment to analyze the interactions between fluid flow and discrete soil particles. The CFD module (ANSYS Fluent 2024 R1) solved the Navier–Stokes equations to describe the fluid dynamics, while the DEM module (ANSYS Rocky 2024 R1) computed the motion and contact forces of individual particles based on Newton’s laws of motion. The coupling between the two solvers enables bidirectional momentum exchange, where the fluid applies drag, lift, and pressure forces on the particles, and in turn, particle movement alters local porosity and introduces momentum sinks that influence the surrounding fluid field.

This integrated modeling framework enables realistic simulation of microscale fluid–particle coupling, especially for irregular or non-spherical grains where particle geometry plays a significant role in hydrodynamic and mechanical responses. The advanced shape-handling capabilities of ANSYS Rocky further improve the physical accuracy of the model, enabling accurate modeling of particle movement, erosion dynamics, and cavity development in complex fluid–particle systems.

2.1. Computational Framework

A coupled CFD–DEM methodology was employed to simulate the complex two-phase interactions between fluid flow and soil particles during the erosion process. The modeling framework follows a Eulerian–Lagrangian formulation, in which the fluid phase is represented as a continuous medium solved by the CFD module, while the DEM was applied to simulate the movement and interactions of individual soil particles. Within this modeling framework, the fluid phase is resolved using the finite volume method (FVM) implemented in ANSYS Fluent, whereas the motion and interactions of individual particles are simultaneously tracked through the DEM solver in ANSYS Rocky. This coupled setup allows for a detailed examination of fluid–solid interaction mechanisms and their impact on the initiation and evolution of erosion during the simulation process.

2.2. Fluid Phase (CFD)

In ANSYS Fluent, the flow field is computed by solving the governing incompressible Navier–Stokes equations:

where

u represents the fluid velocity vector,

ρf denotes the fluid density,

p is the pressure,

µf corresponds to the dynamic viscosity, and

fp is the source term that captures the momentum transfer between the fluid and solid particles.

To incorporate the effects of particle presence on fluid motion, a porosity-coupled formulation was applied, in which the local void fraction within each CFD cell was dynamically updated based on the spatial distribution and concentration of particles in the domain.

2.3. Particle Phase (DEM)

The Discrete Element Method (DEM) is employed to represent the individualized behavior of particles within the system. The motion of each particle is determined by applying Newton’s second law of motion, which governs both translational and rotational dynamics. Accordingly, the particle phase is described through equations that account for the linear and angular movements of every particle under the influence of external and contact forces:

where

mp and

Ip denote the mass and moment of inertia of each particle, respectively;

vp and

ωp correspond to the translational and angular velocities;

Fcontact and

Tcontact represent the forces and torques arising from particle–particle and particle–wall collisions; and

Ffluid and

Tfluid describe the hydrodynamic interactions between the particles and the surrounding fluid.

In this study, the soil particles were modeled as spherical elements using the shape modeling capabilities of Rocky DEM. This simplification allows for efficient computation while maintaining sufficient accuracy to capture the key features of fluid–particle interactions. Although natural soil grains are often irregular in shape, the spherical representation provides a practical approximation that reduces geometric complexity and enhances numerical stability without compromising the overall fidelity of the erosion process. This approach is particularly suitable for studying exfiltration-induced erosion, where the focus lies on the collective motion, detachment, and transport behavior of particles rather than individual grain morphology.

2.4. Coupling Strategy

The coupling between CFD and DEM was implemented using a one-way interaction scheme, as illustrated in

Figure 1. In this configuration:

The fluid velocity and pressure fields computed in ANSYS Fluent generate hydrodynamic forces, including drag and lift, applied to each particle at every time step.

The particle trajectories and spatial distributions, determined by ANSYS Rocky, subsequently influence the fluid momentum balance through source terms that represent momentum exchange between the two phases.

A time-integration strategy with sub-cycling was employed, wherein several DEM iterations were performed within each CFD time step to maintain numerical stability and accuracy, given the shorter collision timescales associated with particle interactions. During each coupling interval, ANSYS Fluent first resolved the fluid flow field and calculated the corresponding hydrodynamic forces acting on the particles. These forces were then transmitted to ANSYS Rocky, which updated the particle trajectories and rotational motion according to both fluid-induced and contact forces. This iterative exchange allowed for one-way coupling, effectively capturing the dynamic interaction between the fluid and particulate phases throughout the erosion process.

The drag and lift force formulations employed in this study are based on the models developed by Gidaspow, Bezburuah, and Ding [

19,

20] for drag and by Mei [

21] for lift. The Gidaspow model allows the model to transition smoothly between low and high particle concentrations, making it well suited for simulating the wide range of local solid volume fractions that occur during exfiltration-induced erosion. Similarly, the Mei [

21] lift model accounts for the relative slip velocity between fluid and particles and the associated pressure and shear gradients, providing realistic lift force estimation even under high-shear, turbulent conditions. Together, these formulations enable accurate representation of fluid–particle coupling in moderate-to-dense regimes near the defect zone, where transient clustering, particle bridging, and local fluidization can strongly affect erosion dynamics and void development.

In the coupled CFD–DEM framework, the porosity field within each CFD cell is dynamically updated at every coupling step to account for the instantaneous spatial distribution of particles. This update is performed using a volume-averaging approach, in which the local void fraction is computed as the ratio of fluid volume to total cell volume after subtracting the cumulative solid volume of particles residing within that cell. The updated porosity field directly influences the local fluid velocity, pressure, and momentum exchange terms, thereby ensuring realistic representation of transient changes in pore structure during erosion and void formation. This approach, consistent with the Eulerian–Lagrangian formulation implemented in the ANSYS Fluent–Rocky coupling interface, allows the model to accurately capture evolving permeability and flow redistribution as soil particles detach, migrate, and create preferential flow paths within the computational domain.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the CFD–DEM coupling procedure implemented in ANSYS Fluent and ANSYS Rocky. The CFD solver (

left) computes the fluid velocity and pressure fields through iterative convergence of the Navier–Stokes and continuity equations, while the DEM solver (

right) detects particle contacts, calculates interparticle forces, and updates particle motion using Newton’s laws. Interaction forces are exchanged between the two solvers at each coupling step, allowing dynamic momentum transfer and fluid–particle interaction throughout the simulation (Modified from Refs. [

13,

22]).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the CFD–DEM coupling procedure implemented in ANSYS Fluent and ANSYS Rocky. The CFD solver (

left) computes the fluid velocity and pressure fields through iterative convergence of the Navier–Stokes and continuity equations, while the DEM solver (

right) detects particle contacts, calculates interparticle forces, and updates particle motion using Newton’s laws. Interaction forces are exchanged between the two solvers at each coupling step, allowing dynamic momentum transfer and fluid–particle interaction throughout the simulation (Modified from Refs. [

13,

22]).

2.5. Rationale for Using One-Way Coupling and Associated Limitations

In this study, a one-way coupling scheme was adopted, where the fluid flow field governs particle motion, while the feedback influence of particle movement on the fluid phase is disregarded. This assumption is considered valid for low particle concentration conditions, where momentum transfer from the solid phase to the fluid is negligible. It is representative of the initial stages of internal erosion, when particle detachment and void growth are still limited. Employing a one-way coupling strategy considerably lowers computational cost and model complexity, allowing an efficient examination of how hydraulic loading and defect geometry affect the initiation and evolution of erosion around buried pipe openings.

Nonetheless, this simplification can lead to inaccuracies in scenarios with dense particle–fluid interactions, particularly near the defect during intense erosion episodes. Under such conditions, variations in porosity, drag, and turbulence caused by particle motion can significantly modify local flow characteristics, influencing pressure gradients and the overall erosion pattern. These feedback effects, including flow diversion, local fluidization, and transient backpressure, are not represented in the one-way formulation. Future developments of this model will focus on implementing two-way or fully coupled CFD–DEM interactions to better capture the complex feedback mechanisms governing advanced erosion and high particle concentration regimes.

In this study, the one-way coupling scheme was intentionally implemented to capture the early stages of internal erosion, during which soil particle concentration in the flow remains relatively low and the feedback of particle motion on the surrounding fluid field is negligible. Under these dilute conditions, hydraulic forces primarily govern particle detachment and initial migration, while the momentum exchange from the dispersed phase to the fluid can be safely neglected without compromising accuracy. This assumption allows efficient exploration of the parametric effects of hydraulic pressure and defect geometry on erosion initiation. However, as erosion progresses and particle concentration increases near the defect, the neglect of feedback effects may underestimate localized flow resistance, turbulence modulation, and backpressure buildup. To address these limitations, future extensions of this model will implement a fully two-way coupled CFD–DEM formulation to capture the dynamic interaction between the fluid and densely entrained particles, enabling simulation of advanced erosion stages where pore-scale feedback, flow diversion, and transient compaction become significant.

2.6. Boundary and Initial Conditions

Fluid boundaries: The exfiltration flow was modeled by imposing a pressure inlet boundary condition on the left side of the domain, while no-slip wall conditions were applied to the pipe boundaries to restrict tangential fluid movement.

Particle boundaries: Solid interfaces were assigned no-slip contact conditions, incorporating restitution and energy loss coefficients to represent realistic particle–wall collisions.

Inlet boundary condition: water pressures of 137.9, 206.8, and 275.8 kPa were applied, respectively, to simulate varying hydraulic loading conditions.

The internal pressure of residential water supply lines ranges between 310.26 (i.e., 45 psi) and 551.58 kPa (i.e., 80 psi). However, with a significant leak, the pressure typically drops to a range between 137.90 (i.e., 20 psi) and 275.8 kPa (i.e., 40 psi). Thus, three pipe internal pressures adopted for this study are 137.90, 206.8 (i.e., 30 psi for the baseline case), and 275.8 kPa.

Outlet boundary conditions: A pressure of 0 kPa was specified to represent atmospheric (open-air) conditions.

Initial conditions: Prior to initiating the flow, a granular bed was allowed to settle under gravitational loading to establish a stable pre-erosion configuration representative of natural soil deposition.

2.7. Simulation Setup

The numerical model was designed to examine erosion processes induced by water leakage through a localized defect in a buried pipe system. A coupled CFD–DEM framework was utilized to simultaneously capture the fluid flow behavior and particle-scale interactions within the surrounding soil. In this setup, the soil medium is represented as a collection of discrete granular particles that interact based on contact and collision mechanics, whereas the fluid motion is described by the locally averaged Navier–Stokes equations governing the continuous phase. This coupled formulation enables an accurate representation of momentum exchange between the seepage flow and the mobilized soil particles, providing detailed insight into the initiation and progression of internal erosion.

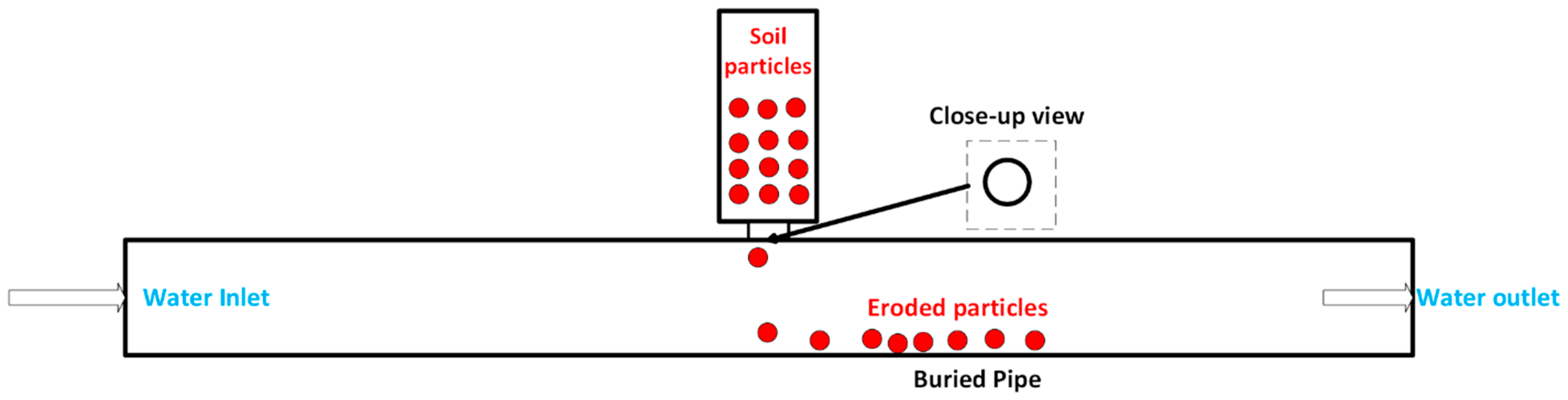

As shown in

Figure 2, the computational setup consists of a cylindrical pipe segment coupled with a porous soil chamber, where a designated defect opening acts as the pathway for exfiltrating flow. This defect, located at the interface between the pipe and surrounding soil, allows dislodged soil particles to be transported into the pipe interior. With ongoing exfiltration, particle detachment and migration occur sequentially, resulting in soil entrainment and downstream transport under the influence of the internal flow. A pressure inlet boundary condition was prescribed to establish the desired hydraulic gradient, while outlet boundaries were defined to maintain steady discharge and numerical stability throughout the simulation domain.

The soil particles in the simulation domain were generated following a representative particle-size distribution and interacted through friction-based contact models to reproduce the mechanical response of real granular soil. This configuration enables detailed observation of progressive erosion, void development, and soil transport dynamics under various hydraulic pressures, thereby providing a robust platform for understanding internal erosion mechanisms near defective pipeline structures.

A refined computational mesh was generated in ANSYS Fluent to resolve detailed fluid flow characteristics, while the DEM solver utilized small integration time steps to accurately capture particle movement and collision interactions. No-slip wall conditions were assigned to the fluid boundaries, and the soil base was fixed to prevent undesired movement. The CFD–DEM coupling scheme enabled continuous data exchange between the solvers at each time step, ensuring a physically consistent description of fluid–particle interactions. In the post-processing phase, particle trajectories were examined to evaluate displacement behavior, void initiation and evolution, and collective particle motion using color-coded visualization. These analyses provided detailed insights into the micromechanical processes driving internal erosion under different exfiltration pressure conditions.

Soil Properties: Uniform soil particles with diameters of 2.0, 2.8, and 4.0 mm were utilized in the CFD–DEM simulations. The corresponding particle counts within the computational domain were approximately 83,290, 27,427, and 10,276 for three different soil particle sizes, respectively.

Fluid Properties: In the simulations, water was selected as the exfiltrating medium, characterized by a density of 1000 kg/m3 and a dynamic viscosity of 0.001 Pa·s.

Flow condition: The Reynolds number varied between 4.22 × 105 and 5.97 × 105, corresponding to a fully turbulent flow regime.

Geometry: A three-dimensional axisymmetric model was constructed to simulate water exfiltration through a buried defective pipe embedded within a soil domain, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The simulated pipe has a diameter of 25.4 mm (1 in.), while the surrounding soil chamber measures 76.2 mm (3 in.) in diameter and 152.4 mm (6 in.) in height, providing sufficient space to accommodate the soil particles and capture the evolution of erosion throughout the analysis. The defect opening on the pipe surface was modeled with three different diameters, including 9.53 mm (3/8 in.), 12.7 mm (1/2 in.), and 19.05 mm (3/4 in.), to examine the influence of defect size on particle detachment and soil migration behavior.

2.8. Assessment of Mesh Resolution and Time-Step Sensitivity

To verify solution accuracy and minimize discretization errors, mesh refinement and time-step sensitivity studies were performed before the main simulations. ANSYS Fluent was used to test three mesh densities with total cells of 31,148; 44,387; and 98,275 cells and the peak flow velocity served as the criterion for mesh adequacy. Results indicated that velocity values stabilized once the cell count reached 44,387, confirming that further refinement produced negligible variation. Therefore, the selected mesh resolution of 44,387 was utilized in all subsequent simulations, providing an optimal balance between computational performance and solution accuracy.

Similarly, time-step sensitivity was evaluated by testing Δt values of 0.1 s, 0.05 s, and 0.025 s, with the total number of particles leaving the computational domain used as the primary indicator for assessing temporal resolution effects. Particle outflow converged for time steps of 0.05 s and smaller, indicating sufficient temporal resolution. Therefore, 0.05 s was adopted as the optimal time step, providing reliable accuracy with manageable computation time.

In the present one-way coupled simulations, the fluid flow field governs particle motion, while the feedback from particle movement to the fluid phase is neglected. Under this formulation, achieving convergence in the fluid velocity and pressure fields inherently ensures convergence of the derived fluid–particle interaction forces, including drag and lift. Mesh refinement tests confirmed that increasing the cell count beyond 44,387 resulted in no changes in peak fluid velocity and corresponding drag force estimates, indicating that the numerical resolution was sufficient to capture the dominant flow gradients influencing particle motion. Similarly, the lift forces exhibited stable magnitudes across successive mesh refinements, further validating consistency in local shear and pressure distribution. Because the one-way coupling decouples particle-induced perturbations from the fluid solution, once the fluid field reaches numerical convergence, the associated hydrodynamic forces acting on particles can be considered converged as well. This ensures that the selected mesh resolution provides reliable accuracy for predicting fluid–particle interactions during erosion initiation and progression.

The analyses verified that the chosen mesh resolution and time-step settings provide numerically stable and consistent outcomes, effectively representing the dominant erosion processes investigated in this work.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Effect of Exfiltration Pressure

Figure 3 illustrates the temporal evolution of soil particle outflow under exfiltration water pressures of 137.9, 206.8, and 275.8 kPa for three defect sizes and particle configurations. In

Figure 3a, where the defect size is 9.53 mm (3/8 in.) and the particle size is 2.0 mm, particle outflow remains relatively low across all pressures, with minor fluctuations over time and a maximum particle count below 12. The outflow trend suggests limited soil mobility due to the smaller defect opening, which restricts particle escape even under elevated pressures.

In

Figure 3b, corresponding to a larger defect size of 12.7 mm (1/2 in.) with the same particle size, a pronounced increase in particle discharge is observed, particularly at 206.8 kPa, where outflow rapidly rises to over 30 particles within the first 0.1 s and maintains a consistently high rate thereafter. This behavior indicates intensified erosion and particle transport driven by enhanced hydraulic gradients and pore connectivity. Interestingly, at the highest pressure (275.8 kPa), particle release decreases after an initial surge, likely due to local clogging or the formation of stable particle arches at the defect boundary that partially inhibit further outflow.

In

Figure 3c, representing the largest defect size of 19.05 mm (3/4 in.) and particle size of 2.8 mm, the outflow pattern differs significantly. A sharp initial burst of particle release occurs at 137.9 kPa, followed by a rapid decline, indicating a transient flushing event where most mobile particles are expelled early during exfiltration. However, at higher pressures of 206.8 and 275.8 kPa, the number of particles exiting is notably lower compared to 137.9 kPa. This reduction may be attributed to the increased hydraulic force compacting particles near the defect or promoting the formation of stable clusters that resist further movement.

Overall, these results highlight the complex interplay between hydraulic pressure, defect geometry, and particle size in governing soil erosion and transport dynamics, with intermediate pressures and moderate defect sizes producing the most sustained and active particle outflow.

Figure 4 presents the evolution of soil particle detachment and erosion progression under exfiltration pressures of (a) 137.9 kPa, (b) 206.8 kPa, and (c) 275.8 kPa. Each panel displays particle distributions at time intervals of 0, 10, and 20 s, with color-coded particle IDs used to visualize individual motion and the development of localized erosion zones. In all cases, the defect size is 12.7 mm (½ in.), and the particle size is 2.0 mm.

At the lowest pressure (137.9 kPa,

Figure 4a), particle detachment initiates gradually around the defect, producing a symmetric erosion pattern with limited upward migration. The erosion front remains localized, indicating that the hydraulic force is sufficient to mobilize particles near the defect but insufficient to induce widespread detachment. As the pressure increases to 206.8 kPa (

Figure 4b), a more extensive erosion zone develops, characterized by a funnel-shaped detachment region extending upward and laterally from the defect. The enhanced hydraulic gradient promotes particle displacement and pore structure expansion, leading to a steady progression of soil loss over time. At the highest pressure (275.8 kPa,

Figure 4c), erosion occurs rapidly during the early stage but subsequently stabilizes, showing reduced expansion of the detachment zone compared with the 206.8 kPa case. This pattern suggests that higher pressures may induce localized compaction or particle bridging near the defect, which temporarily resists further erosion despite strong hydraulic loading.

Overall, the visualization highlights the nonlinear relationship between hydraulic pressure and erosion behavior: moderate pressures promote continuous detachment and expansion, while excessively high pressures can lead to transient stabilization effects due to particle interlocking or clogging mechanisms.

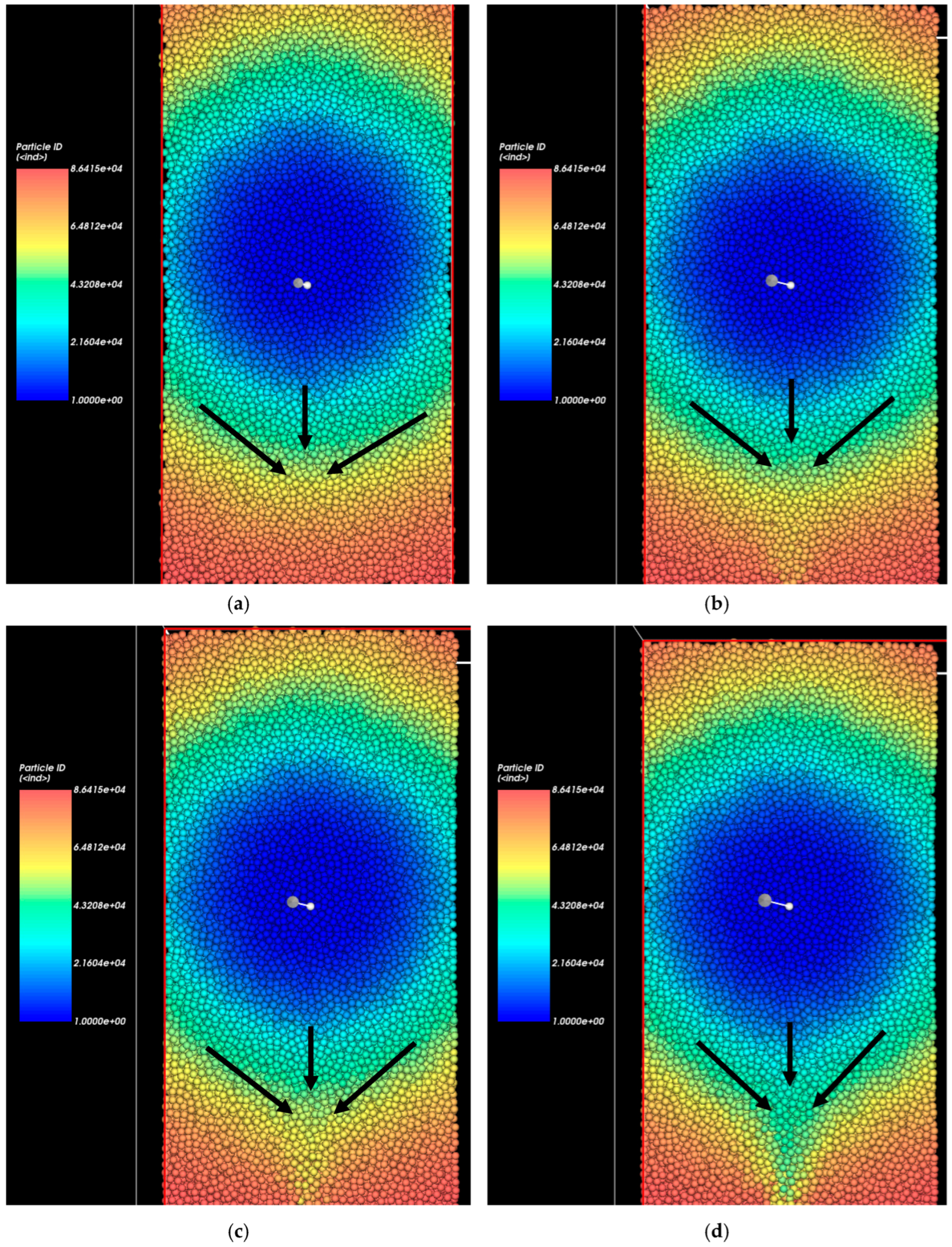

3.2. Temporal Evolution of Erosion Process

Figure 5 depicts the time-dependent development of soil particle erosion under an exfiltration pressure of 206.8 kPa and a defect diameter of 12.7 mm (½ in.). The sequence from (a) 0 s to (h) 20 s captures the progressive detachment, transport, and rearrangement of soil particles. Each particle is color-labeled by ID, allowing visualization of individual trajectories and erosion evolution throughout the simulation.

At the initial stage (0–1 s), the soil structure remains largely intact, with only minor disturbance near the defect opening as pore water pressure begins to act on the surrounding particles. By 2–5 s, particle detachment becomes more pronounced, and localized erosion initiates around the defect boundary, forming an incipient flow channel. Between 10–12 s, the erosion front expands both upward and laterally, accompanied by noticeable particle displacement, indicating increased hydraulic shear and internal instability. By 15–20 s, a well-defined funnel-shaped cavity develops, signifying sustained particle removal and the establishment of a preferential flow path for exfiltrating water.

Overall, the sequence reveals a clear progression from initial detachment to channelized erosion, demonstrating that under 206.8 kPa, the applied hydraulic pressure is sufficient to trigger continuous particle mobilization and structural deformation around the defect. The color-coded particle tracking highlights the transition from localized motion to large-scale rearrangement, emphasizing the critical role of hydraulic gradients in driving internal erosion.

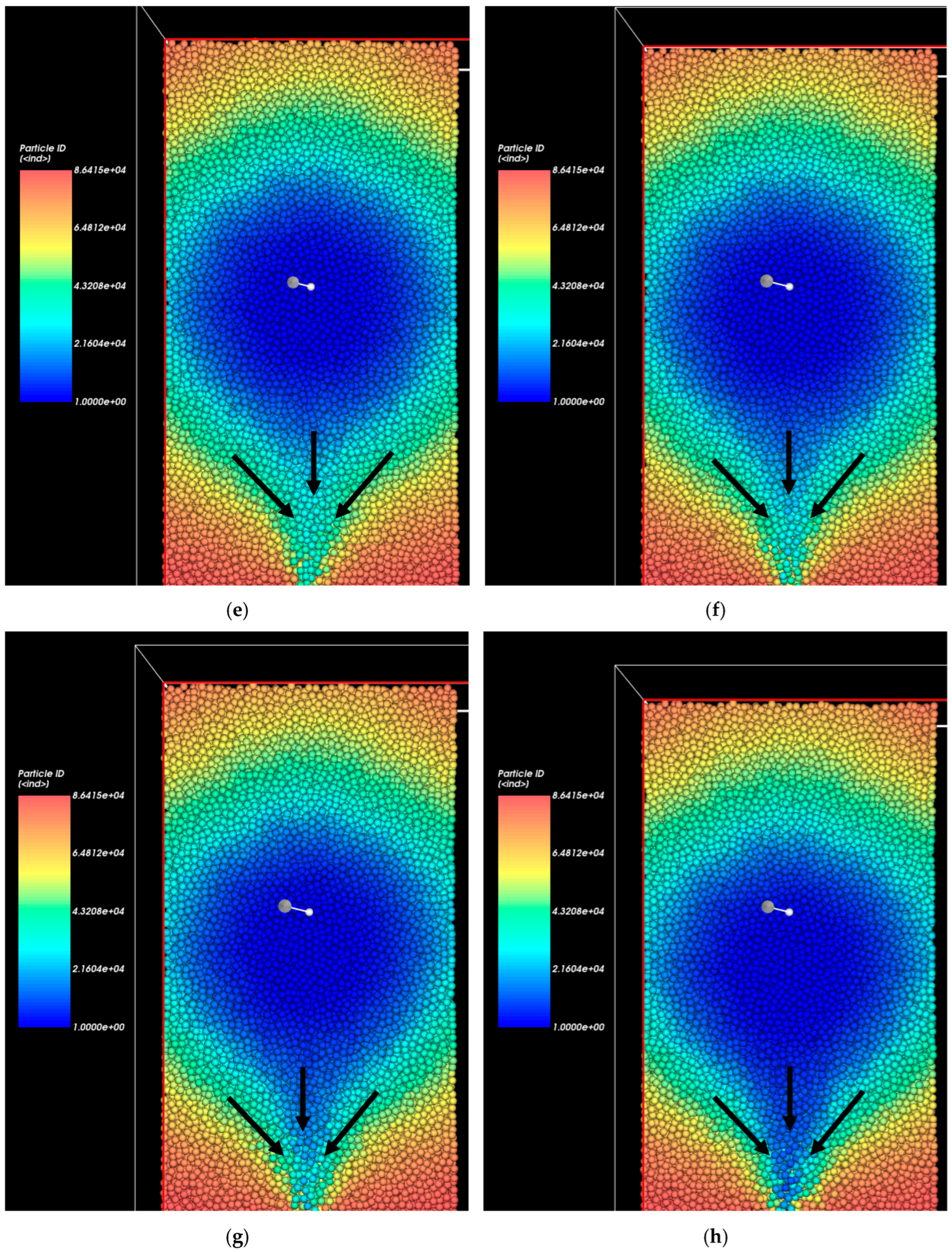

3.3. Effect of Particle Sizes

Figure 6 illustrates the effect of particle size on erosion development under an exfiltration pressure of 206.8 kPa with a defect size of 12.7 mm (½ in.). The figure presents erosion patterns at 10 s (left column) and 20 s (right column) for particle sizes of (a) 2.0 mm, (b) 2.8 mm, and (c) 4.0 mm. Soil particles are color-coded by particle ID to visualize areas of active motion and detachment throughout the erosion process.

For the smallest particle size (2.0 mm,

Figure 6a), a well-defined erosion channel develops rapidly around the defect, extending upward and laterally over time. The finer particles are more easily mobilized by the exfiltrating flow, leading to pronounced detachment and a clear funnel-shaped cavity by 20 s. In contrast, for the medium particle size (2.8 mm,

Figure 6b), the erosion front expands more gradually, with a narrower flow channel and reduced particle mobility. The movement remains concentrated near the defect, suggesting that larger particles require greater hydraulic energy to overcome interlocking resistance and initiate transport. For the coarsest particles (4.0 mm,

Figure 6c), only minimal erosion occurs, and the particle arrangement remains relatively stable even after 20 s, indicating that the hydraulic force at 206.8 kPa is insufficient to induce significant detachment for larger grains.

Overall, the results demonstrate that particle size plays a critical role in controlling erosion initiation and progression under exfiltration conditions. Smaller particles exhibit higher susceptibility to detachment and transport, while larger particles tend to stabilize the soil structure, reducing erosion rates and limiting cavity expansion near the defect.

3.4. Effect of Pipe Defect Sizes

Figure 7 shows the time-dependent variation in soil particle discharge for pipe defect diameters of 9.53 mm (blue), 12.7 mm (orange), and 19.05 mm (gray) under exfiltration pressures of (a) 137.9 kPa, (b) 206.8 kPa, and (c) 275.8 kPa. The results highlight the combined effects of hydraulic pressure and defect geometry on particle detachment and transport behavior during exfiltration-induced erosion.

At the lowest pressure (137.9 kPa,

Figure 7a), particle outflow remains relatively low across all defect sizes, with the largest defect (19.05 mm) showing slightly higher particle counts than the smaller ones. This indicates limited hydraulic energy for particle mobilization, where only localized detachment occurs near the defect opening. Under moderate pressure (206.8 kPa,

Figure 7b), the particle outflow for the 12.7 mm defect increases dramatically, reaching peaks around 20–25 particles, while both smaller and larger defects show significantly lower counts. The 9.53 mm defect restricts flow and particle escape due to its narrow opening, whereas the 19.05 mm defect likely experiences reduced particle ejection efficiency caused by localized arching and transient clogging near the defect boundary.

At the highest pressure (275.8 kPa,

Figure 7c), particle outflow again becomes irregular and less pronounced across all defect sizes. The 12.7 mm defect maintains moderate activity with intermittent bursts, but overall counts remain lower than at 206.8 kPa. This suggests that excessive hydraulic pressure may lead to temporary stabilization of the soil matrix through compaction or particle bridging, reducing sustained erosion.

Overall, the results demonstrate that erosion intensity is strongly influenced by both defect size and hydraulic pressure. The intermediate defect size (12.7 mm) consistently produces the highest and most sustained particle outflow, indicating an optimal balance between hydraulic driving force and particle mobility, while smaller and larger defects exhibit limited erosion due to geometric and mechanical constraints.

Figure 8 shows the distribution of soil particle IDs corresponding to pipe defect diameters of (a) 9.53 mm, (b) 12.7 mm, and (c) 19.05 mm under an exfiltration pressure of 137.9 kPa and a uniform particle size of 2.8 mm. Each panel shows the erosion configuration at 10 s (left) and 20 s (right), with particles color-coded by their IDs to visualize localized motion, detachment, and rearrangement during exfiltration-induced erosion.

For the smallest defect size (9.53 mm,

Figure 8a), only minor particle displacement occurs near the defect opening, and the overall soil structure remains stable over time. The limited outflow suggests that the hydraulic force is insufficient to overcome the constraining geometry, leading to minimal detachment and negligible erosion progression. In contrast, for the medium defect size (12.7 mm,

Figure 8b), a distinct erosion zone develops, characterized by a widening funnel-shaped cavity extending upward from the defect. Between 10 and 20 s, continued particle migration and rearrangement occur, indicating active erosion and internal soil weakening driven by moderate hydraulic gradients.

For the largest defect (19.05 mm,

Figure 8c), erosion becomes more asymmetric, with noticeable lateral instability and localized void formation along the side boundaries. The increased opening allows greater water flux, yet the larger defect also promotes uneven particle movement and localized collapse zones.

Overall, the results reveal that erosion severity and symmetry are highly dependent on defect size. The 12.7 mm defect produces the most continuous and balanced erosion pattern, while smaller defects limit erosion initiation and larger ones induce localized instability, demonstrating the interplay between hydraulic driving force and geometric confinement in governing soil detachment and transport behavior.

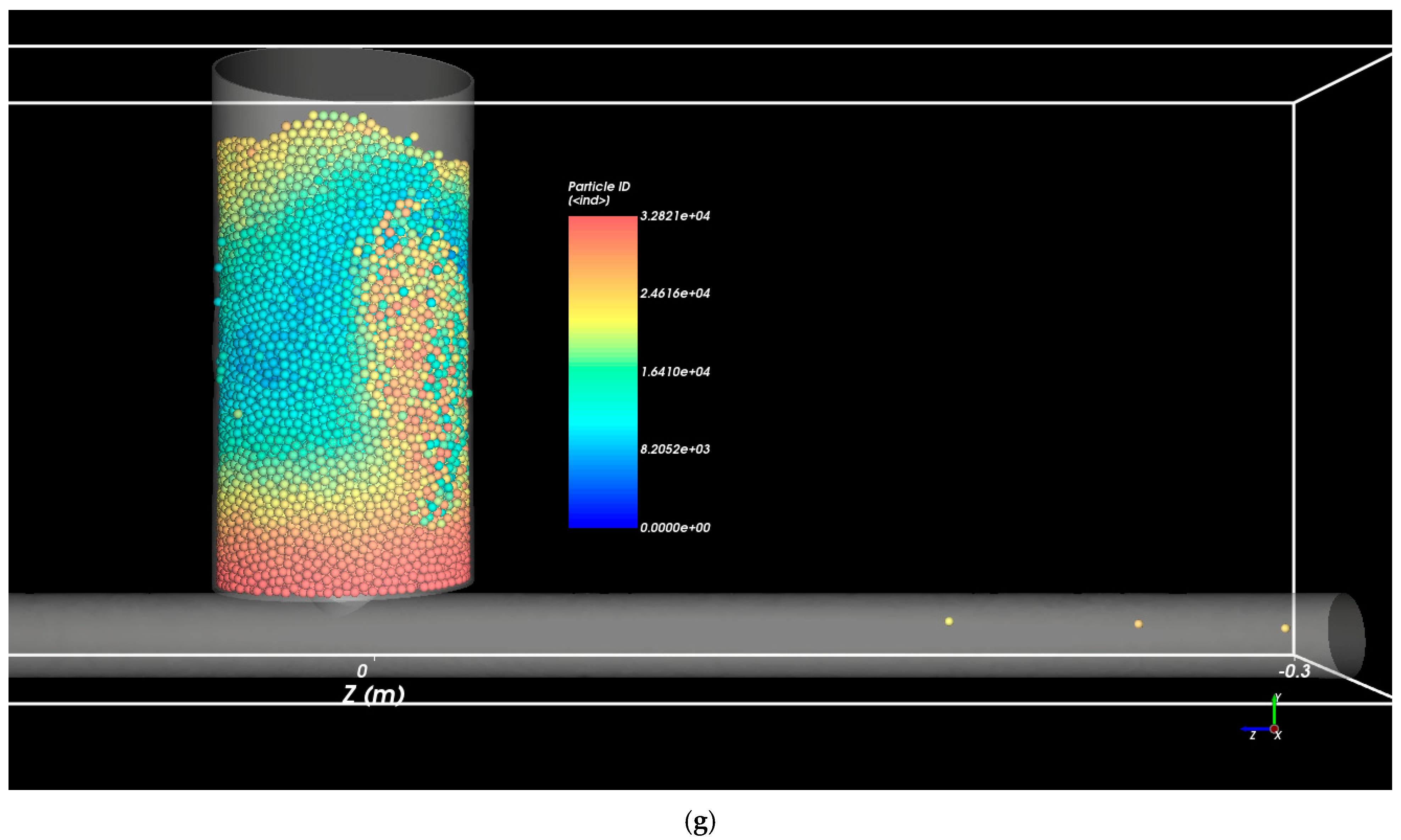

3.5. Dynamics of Soil Particle Transport Through Pipe Flow

Figure 9 presents a 3D depiction of the internal erosion process driven by water exfiltration through a pipe defect. The soil particles are color-labeled by ID group, allowing visualization of their movement trajectories and the progressive formation of erosion channels. The simulation sequence captures particle detachment, migration, and transport from the surrounding soil mass into the pipe interior under an inlet pressure of 137.9 kPa, with a defect opening of 19.05 mm (¾ in.) and a particle diameter of 2.8 mm. The time-lapse images correspond to (a) 0 s, (b) 0.1 s, (c) 0.2 s, (d) 5 s, (e) 10 s, (f) 15 s, and (g) 20 s, depicting the sequential stages of erosion evolution.

At the early stage (0–0.1 s), the soil structure remains largely undisturbed, with only slight movement observed near the defect opening. As exfiltration begins (0.2–5 s), localized particle detachment initiates around the defect boundary, producing a small but concentrated erosion zone driven by hydraulic pressure. Between 10 and 15 s, the erosion front expands upward and laterally, indicating the formation of preferential flow channels within the soil mass as interparticle contacts weaken under continuous seepage forces. By 20 s, a well-defined flow conduit is established, marking the transition from initial particle release to a steady state of sustained soil transport.

Overall, the 3D time-resolved visualization highlights the progressive and dynamic nature of exfiltration-induced internal erosion. The results demonstrate how hydraulic gradients, particle rearrangement, and localized arching collectively govern the evolution from stable soil packing to the development of continuous erosion pathways, ultimately leading to structural instability around the pipe defect.

3.6. Erosion Dynamics and Formation of Void Zones

The coupled CFD–DEM simulations reveal that exfiltration-induced internal erosion progresses through distinct and nonlinear stages, governed by the interplay among exfiltration pressure, defect geometry, and particle size. At the onset of exfiltration, detachment of soil particles occurs locally near the defect boundary where hydraulic gradients first exceed the critical threshold for particle motion. During this initiation phase, the erosion rate remains low because the local pore pressure is partially dissipated by the compact soil skeleton. As the flow continues, however, particle rearrangement and porosity increase in the vicinity of the defect, leading to a positive feedback mechanism that accelerates fluid flux and particle mobilization. This transition corresponds to the sharp rise in particle outflow observed in

Figure 3 and

Figure 7, particularly under moderate inlet pressures (e.g., 206.8 kPa).

The visualization results (

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) demonstrate that erosion evolves from a confined cavity to an extended funnel-shaped or vertically elongated void zone. The geometry and expansion rate of this void zone are closely linked to hydraulic and geometric boundary conditions. For smaller defects (e.g., 9.53 mm), erosion remains localized and self-limiting due to restricted flow paths. Intermediate defects (12.7 mm) promote sustained detachment and continuous channel formation, producing the highest and most stable particle outflow rates. Conversely, the largest defects (19.05 mm) generate asymmetric or intermittent erosion patterns; although greater flow enters the pipe, particle bridging and temporary clogging often suppress sustained transport. These behaviors highlight a non-monotonic dependence of erosion rate on defect size and pressure, with intermediate configurations yielding maximum erosion efficiency.

From a mechanistic perspective, the observed progression aligns with critical shear theory, wherein erosion transitions from initiation to propagation once local hydraulic shear stresses exceed the combined resistance from interparticle friction, contact locking, and cohesive effects. Beyond this threshold, detachment becomes self-sustaining and is accompanied by internal instability as particles lose mutual confinement. The color-coded particle ID tracking clearly delineates zones of concentrated stress and preferential flow pathways—early indicators of internal structural degradation and potential sinkhole initiation.

In this study, the term threshold shear stress refers to the critical hydraulic condition at which the local shear stress imposed by the exfiltrating fluid first exceeds the resisting forces that maintain particle stability. This condition marks the onset of erosion, corresponding to the transition from a stable soil matrix to initial particle detachment. The threshold behavior observed in the simulations is consistent with the critical shear stress framework described by Shields [

23] and later refined through impulse-based erosion criteria proposed by Diplas et al. [

24]. When the local hydraulic gradient surpasses this critical limit, pore pressures overcome the effective stress within the soil skeleton, initiating localized particle motion and void expansion. Below this limit, soil particles remain interlocked despite increasing fluid pressure, resulting in negligible erosion. Therefore, the identified threshold pressure in the present results represents the minimum hydraulic loading required to trigger continuous particle migration and sustained erosion under exfiltration conditions.

The simulations also underscore that particle size exerts a strong stabilizing influence on erosion dynamics. Finer particles (2 mm) respond rapidly to hydraulic forces, forming continuous erosion channels, while coarser particles (≥4 mm) resist detachment and inhibit cavity enlargement. This particle size dependence reflects the balance between drag force and interparticle contact strength, and it explains the shift from continuous erosion to intermittent flushing observed in the visualizations.

Overall, the CFD–DEM results confirm that even modest exfiltration pressures (≈137.9 kPa) can initiate progressive soil loss once local hydraulic and geometric conditions satisfy the detachment criterion. The coupled modeling approach captures both the microscale particle dynamics and the macroscale evolution of void zones, providing valuable insight into how localized leakage can escalate into large-scale instability around buried pipes.

These findings suggest that pipeline vulnerability assessments must consider not only hydraulic intensity but also defect geometry, soil gradation, and mechanical confinement effects. Integrating CFD–DEM simulations with field data could refine empirical erosion thresholds and inform preventive design strategies such as optimized bedding materials, pressure control, and early-warning monitoring systems. Future studies should extend this framework to explore long-term cyclic loading, partially saturated soils, and pipe–structure interactions to develop advanced predictive frameworks for underground erosion processes and sinkhole hazard assessment.

4. Discussion

The coupled CFD–DEM framework accurately modeled erosion phenomena induced by water exfiltration from defective buried pipelines, reproducing the stages of particle detachment, movement, and cavity evolution consistent with experimental findings. The results demonstrate that exfiltration pressure, particle size, and defect geometry govern the initiation and evolution of erosion. Increased hydraulic loading and larger defect openings accelerate particle detachment, producing more pronounced erosion cavities and enhancing the likelihood of soil instability. These observations highlight the combined influence of local hydraulic gradients, defect characteristics, and particle-scale interactions in shaping the erosion pathway and cavity morphology.

4.1. Relation to Prior Work and Major Findings

One of the principal outcomes of this research is the three-dimensional visualization of erosion development around defective pipelines, which enables direct observation of particle trajectories, void enlargement, and collapse events over time. The simulations reveal that erosion initiates near the defect and expands upward and outward, with preferential flow paths forming along high-pressure gradients. The formation and subsequent failure of soil arches were consistently observed—these structures temporarily stabilized the soil mass but collapsed once hydraulic stresses exceeded their bearing capacity, resulting in rapid soil loss and channel expansion.

The formation and collapse of particle bridges and soil arches observed in the simulations can be directly linked to the contact mechanics captured by the DEM framework. During the early stages of erosion, interparticle contact forces form localized load-bearing structures that temporarily resist hydraulic shear, creating arch-like configurations near the defect boundary. These transient force chains redistribute stress throughout the surrounding soil mass, stabilizing the structure until the increasing fluid pressure and drag forces exceed the interparticle friction and normal contact resistance. Once this critical condition is reached, the arches collapse abruptly, resulting in rapid particle release and localized void expansion. The cyclic formation and failure of these contact-force networks were evident in the DEM outputs as temporal fluctuations in contact number, reflecting the intermittent stability of the granular skeleton under evolving hydraulic loads. This dynamic arching mechanism provides a physical explanation for the observed oscillatory particle discharge and intermittent erosion patterns near the defect zone.

These findings align qualitatively with the experimental investigations of Tang et al., Guo et al., and Dai et al. [

6,

11,

17,

25], who documented similar patterns of defect-driven erosion using laboratory models. However, the present CFD–DEM approach extends their work by providing quantitative data on local flow velocity, pressure distribution, and particle displacement fields. While previous physical studies identified correlations between defect geometry and erosion rate, this study establishes a mechanistic explanation by resolving the coupled hydrodynamic and particle-scale interactions that control erosion onset and progression.

The current results also corroborate the numerical analyses of Ibrahim and Meguid [

13], confirming the presence of a free-fall arch regime and an erosion saturation threshold beyond which additional pressure produces limited increases in soil loss. Notably, our model further demonstrates that for larger defect sizes or elevated pressures, this threshold can be surpassed, leading to continuous erosion and cavity coalescence. Additionally, the influence of defect orientation is clearly evident defects located along the invert of the pipe promote more extensive erosion zones, while crown defects confine erosion to a localized region. These trends are consistent with observations from Wang et al. and Dai et al. [

1,

11], reinforcing the physical validity of the simulated erosion mechanisms.

Moreover, the simulation results confirm an exponential dependence between the soil-to-water flow ratio and the relative size of the defect opening to the particle diameter proposed by Tang et al. [

6] through extended Beverloo-type free-fall models. The CFD–DEM results enhance these formulations by identifying localized instability zones and capturing cavity geometry evolution, providing new granularity for erosion prediction and risk assessment.

To evaluate the reasonableness of the present one-way coupling approach, comparisons were made with previously published two-way coupled CFD–DEM studies. Ibrahim and Meguid [

13] demonstrated that fully coupled fluid–particle feedback becomes dominant only at later erosion stages, when particle concentrations are high and the local porosity drops significantly near the soil–fluid interface. Similarly, Guo and Yu [

18] compared three mathematical formulations of two-way coupling and found that for dilute or moderately dense regimes, the predicted flow velocity, pressure field, and drag force varied by less than 10%, confirming that simplified coupling schemes can accurately capture the early-stage erosion behavior. These observations are consistent with the present findings, where the one-way coupled framework successfully reproduces the initiation of particle detachment and the evolution of early void zones under low-concentration flow conditions. Future model development will incorporate two-way coupling to extend this framework to later erosion phases, allowing feedback-induced effects such as turbulence modulation, local pressure redistribution, and dense-phase momentum exchange to be fully resolved.

Overall, the proposed simulation framework integrates empirical observations, analytical modeling, and particle-scale mechanics, providing a deeper and more unified understanding of internal erosion and sinkhole formation mechanisms driven by pipe defects.

4.2. Critical Shear Conditions for Erosion Initiation

The initiation of particle motion in the simulated erosion process corresponds closely with the theoretical concept of critical shear stress (

τc)—the condition where hydrodynamic forces surpass interparticle resistance, contact resistance, and submerged weight [

23,

24,

26,

27]. In the present simulations, the onset of erosion occurred as local shear stress near the defect surpassed this critical value. Once this threshold was reached, particle motion propagated progressively outward, weakening soil arches and enlarging the erosion cavity.

The CFD–DEM framework provides a unique capability to evaluate hydraulic shear and contact forces directly at the particle scale, enabling visualization of how fluid–solid coupling drives erosion. Results indicate that after the critical shear stress is exceeded, erosion becomes self-sustaining, as detachment reduces confinement and enhances pore flow, producing a positive feedback mechanism. This progression, from initial detachment to rapid channel formation, agrees with established sediment transport theory and validates the physical realism of the simulated erosion processes.

Understanding the conditions governing the onset of erosion and the collapse of soil arches provides valuable insight into infrastructure vulnerability. These findings suggest that monitoring hydraulic gradients and defect geometry can serve as key indicators for early detection of erosion-prone zones, ultimately supporting the development of more robust and erosion-resistant buried pipeline infrastructure and preventive maintenance strategies.

4.3. Limitations of the Present Study

While the developed CFD–DEM framework effectively captures the mechanisms of internal soil erosion induced by exfiltration through defective buried pipes, several modeling assumptions constrain its broader applicability. The present simulations employ monodisperse, cohesionless spherical particles, which simplify soil representation and facilitate numerical stability but may not fully reflect the behavior of naturally graded or cohesive geomaterials. Consequently, key micro-mechanical processes such as particle interlocking, suction effects, and cementation are not explicitly represented. In addition, a one-way coupling scheme was adopted, where particle feedback to the fluid phase is neglected. Although this approach is suitable for dilute-erosion regimes, it may underestimate local flow alterations and backpressure effects in dense particle zones near the defect. The model also assumes steady hydraulic boundary conditions, whereas real-world exfiltration events often involve transient or cyclic pressures that can exacerbate erosion. Finally, the absence of experimental validation limits quantitative assessment of model accuracy, and further work integrating laboratory or field data will be necessary to verify and calibrate the simulation outcomes.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This study developed a coupled Computational Fluid Dynamics–Discrete Element Method (CFD–DEM) modeling framework to investigate the mechanisms of internal soil erosion and void formation induced by water exfiltration through defective buried pipelines. The simulations successfully reproduced the sequential processes of particle detachment, migration, and cavity evolution, providing detailed insights into how hydraulic and geometric parameters influence erosion dynamics. The results revealed that exfiltration pressure, particle size, and defect size exert a dominant influence on erosion initiation and progression. Higher pressures and larger openings accelerate soil detachment and void expansion, whereas smaller defect sizes tend to promote clogging or partial erosion. The study also demonstrated the capability of CFD–DEM modeling to visualize particle-scale motion, identify preferential flow paths, and quantify the temporal development of erosion zones.

The simulation findings were consistent with previously reported laboratory observations and theoretical models, reinforcing the physical reliability of the proposed approach. The results also support the existence of an exponential relationship between the ratio of soil-to-water discharge and the ratio of defect to particle size, validating earlier analytical predictions. Collectively, this work bridges the gap between empirical evidence, analytical theory, and micro-mechanical modeling, providing a comprehensive understanding of exfiltration-driven internal erosion mechanisms.

Despite these advances, several simplifying assumptions limit the scope of the current model. The simulations employed monodisperse, cohesionless spherical particles, which capture essential erosion behaviors but do not account for the complex interactions present in graded or cohesive soils. The use of a one-way coupling scheme neglects the feedback of particle motion on fluid flow, which may influence local pressure fields and turbulence at high particle concentrations. Additionally, steady-state boundary conditions were assumed, while actual leakage events often involve transient or cyclic pressure fluctuations.

Future extensions of this work should therefore focus on several aspects:

Future research will focus on experimental validation of the CFD–DEM modeling framework through controlled laboratory studies. These experiments will involve flume and exfiltration tests designed to quantify soil loss, pressure gradients, and cavity evolution under well-defined hydraulic and geometric conditions. The collected data will provide benchmark measurements for calibrating model parameters such as drag coefficients, particle contact properties, and critical shear thresholds. Quantitative comparison between measured and simulated erosion rates, void geometries, and temporal particle discharge will enable systematic model validation and uncertainty assessment. In addition, field-scale observations from pipeline leak monitoring will be integrated to further verify model scalability and realism. This combined numerical–experimental approach will strengthen the predictive reliability of the CFD–DEM framework and establish a validated basis for future applications in buried-pipe risk assessment and sinkhole prediction [

28].

Future work will expand the current modeling framework to incorporate more realistic soil characteristics by employing poly-disperse, non-spherical, and partially cohesive particle assemblies. The inclusion of particle shape irregularity through polyhedral or clumped-particle representations will enable more accurate simulation of interlocking behavior, frictional resistance, and load transfer within the soil matrix. Introducing particle-size gradation will allow investigation of packing density effects and fines migration mechanisms, which are critical in naturally heterogeneous soils. In addition, cohesive and bonded contact models will be implemented to represent suction, cementation, and electrochemical bonding between fine particles, thereby extending the framework’s applicability to cohesive and mixed-grained geomaterials. Collectively, these enhancements will bridge the gap between idealized numerical representation and real soil behavior, providing a more comprehensive and physically representative tool for studying exfiltration-induced erosion and sinkhole development.

Incorporation of particle breakage and cementation models to simulate natural soil resistance degradation.

Integration of structural–geotechnical coupling to assess how progressive erosion affects pipe deformation and failure.

Parametric exploration of defect geometry, inclination, and position to establish more comprehensive predictive relationships.

Future research will incorporate transient and cyclic hydraulic loading conditions to more accurately represent real-world leakage behavior in buried pipeline systems. In practice, pressure fluctuations caused by pump cycling, valve operation, and intermittent service demand can significantly influence the initiation and progression of internal erosion. These variations may lead to repeated pore pressure changes, cyclic shear stresses, and alternating phases of soil detachment and reconsolidation—mechanisms that cannot be captured under steady-state assumptions. To address this limitation, future CFD–DEM simulations will integrate time-dependent boundary conditions to model pulsating or periodic flow patterns, enabling detailed investigation of erosion fatigue, particle rearrangement, and defect enlargement under variable hydraulic regimes. Incorporating these transient effects will enhance the predictive capability of the model and provide more realistic insights into the long-term stability and failure risk of leaking buried pipelines.

Application of data-driven approaches, such as machine learning, to develop predictive erosion-risk assessment tools based on CFD–DEM outputs [

29].

The model will be extended to a fully two-way coupled CFD–DEM framework to accurately capture dense-phase interactions, pressure redistribution, and transient feedback between the fluid and particulate phases. Such coupling will enable simulation of advanced erosion stages where pore-scale hydrodynamics, particle-induced drag variation, and backpressure effects play dominant roles in the evolution of internal erosion and void development around buried pipes.

Future studies will emphasize improving the statistical robustness of CFD–DEM simulations through multiple stochastic realizations and uncertainty quantification. Because individual particle trajectories and contact events are inherently stochastic, single-run simulations can only capture qualitative trends in erosion behavior. To address this limitation, future work will perform replicate simulations under identical boundary conditions but with randomized initial particle packing and velocity distributions. The resulting data will be analyzed using ensemble averaging to quantify variability in key output parameters such as erosion rate, particle discharge, and void volume evolution. Additionally, sensitivity analyses will be conducted to evaluate the influence of mesh resolution, time step, and particle contact parameters on model uncertainty. These efforts will provide statistically meaningful error bounds and improve the confidence and reproducibility of numerical predictions for exfiltration-induced erosion.

By pursuing these directions, future research can build on the findings of this study to develop more realistic and predictive models for exfiltration-induced internal erosion. Such advancements will contribute to the design of more resilient buried infrastructure systems and improved risk assessment frameworks for ground instability associated with subsurface leakage.