Collapse Pressure Prediction for Marine Shale Wellbores Considering Drilling Fluid Invasion-Induced Strength Degradation: A Bedding Plane Slip Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

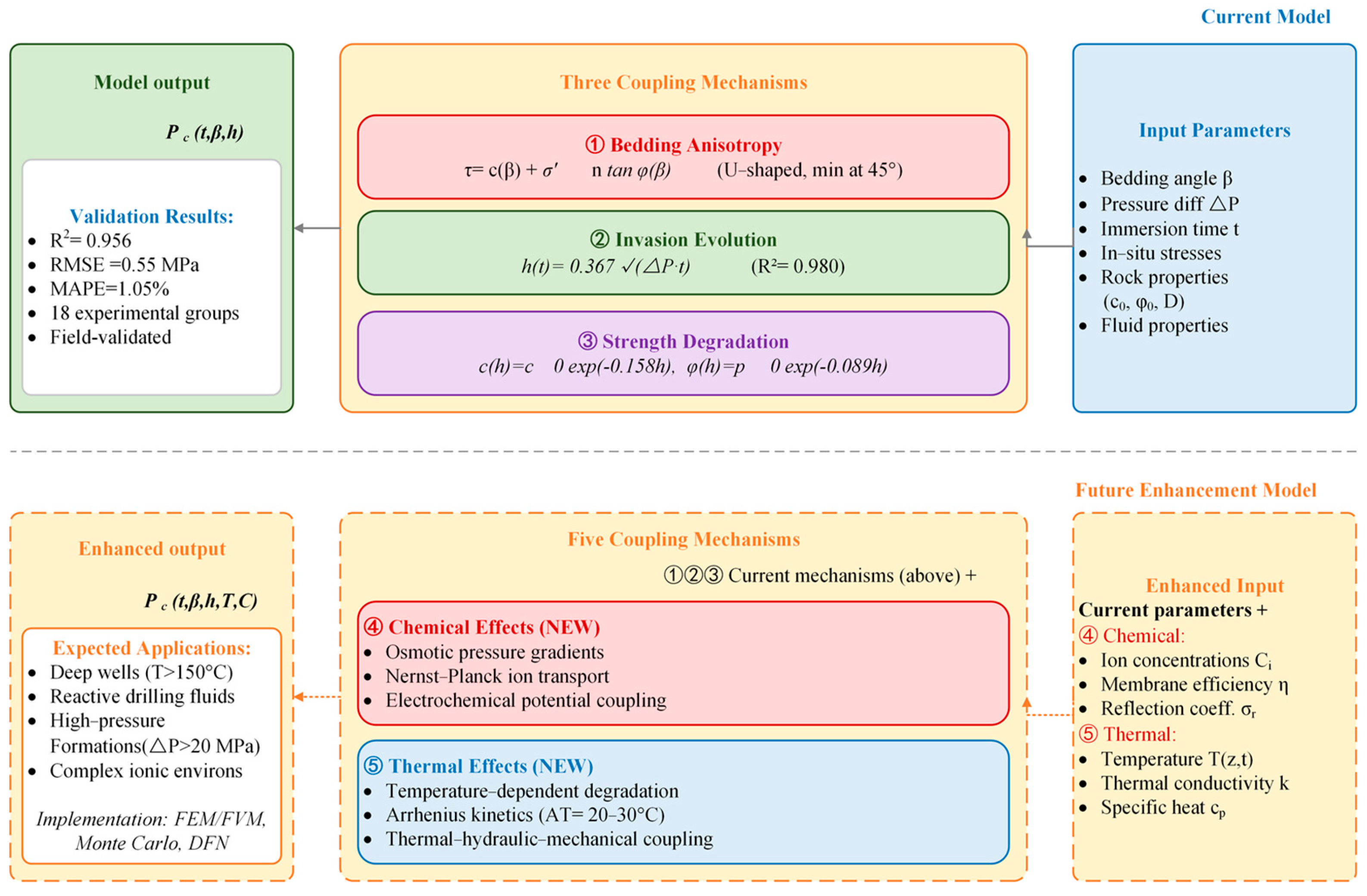

2. Theoretical Model

2.1. Model Assumptions

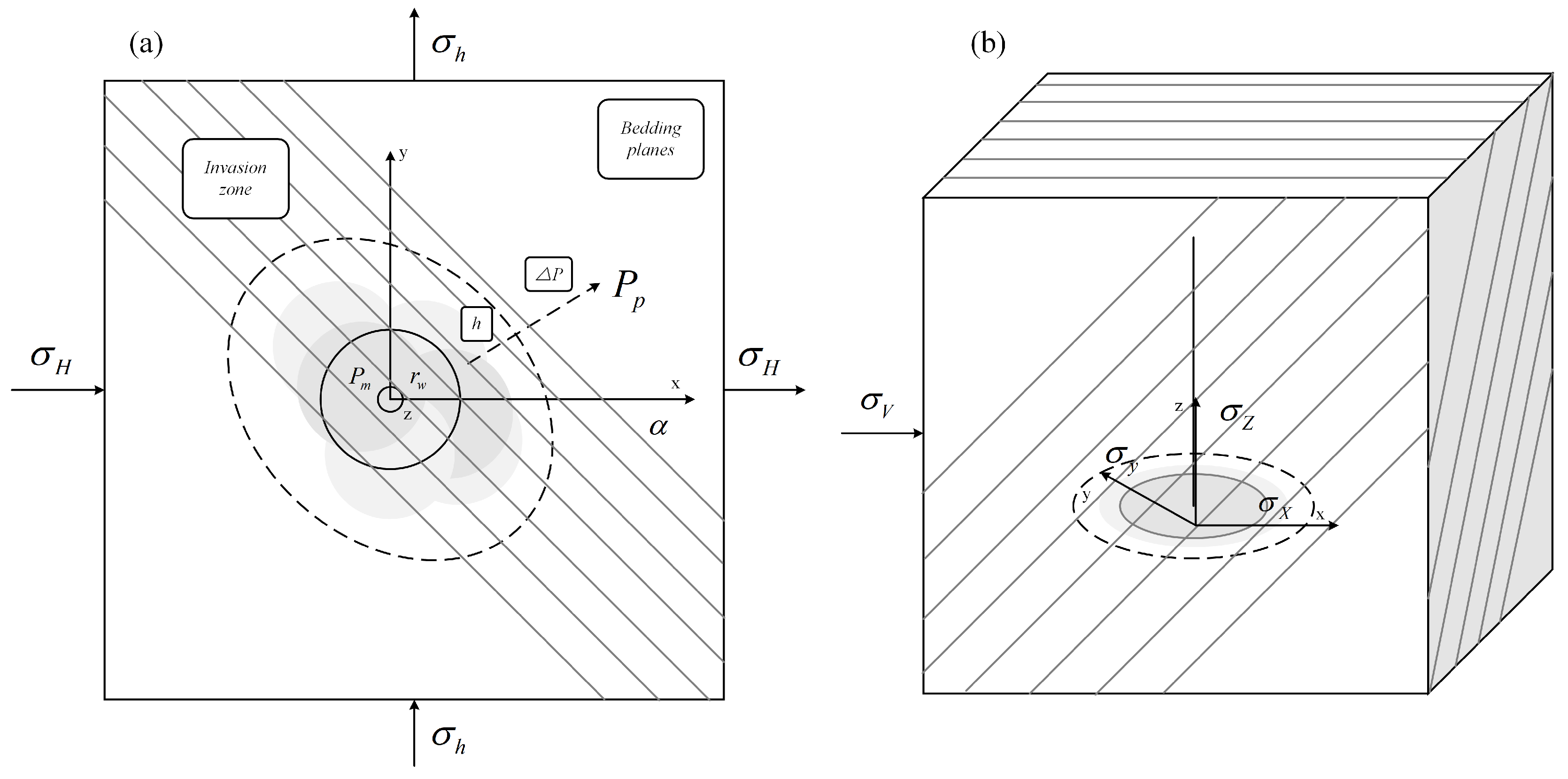

2.2. Stress Analysis

2.3. Collapse Pressure Model

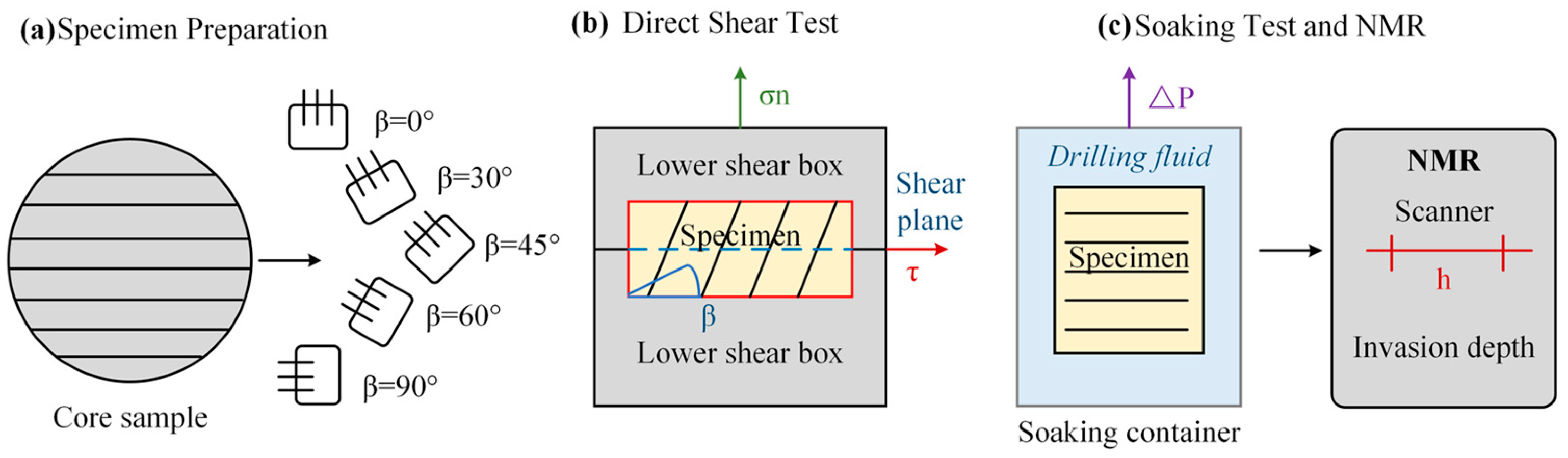

3. Experimental Study

3.1. Materials and Methods

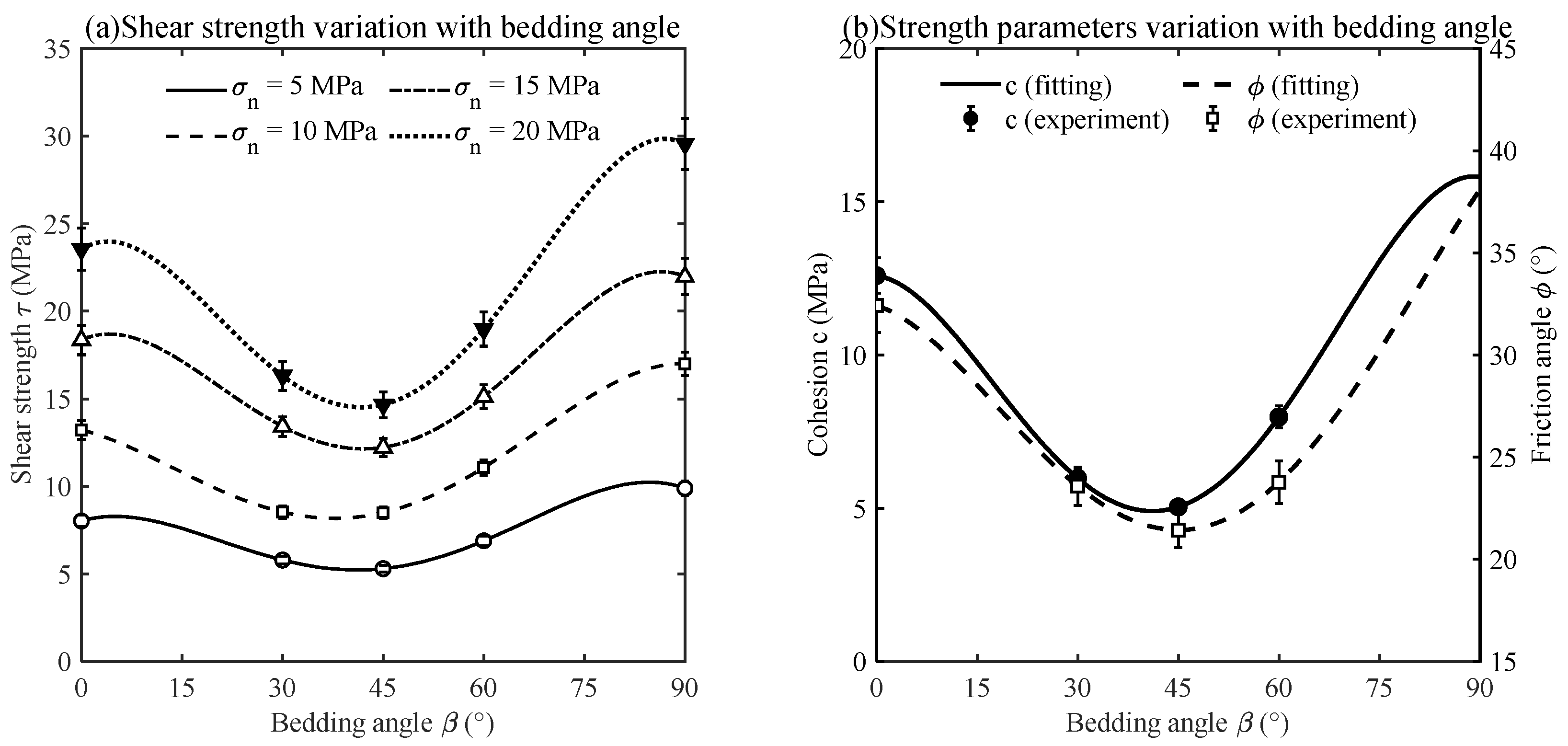

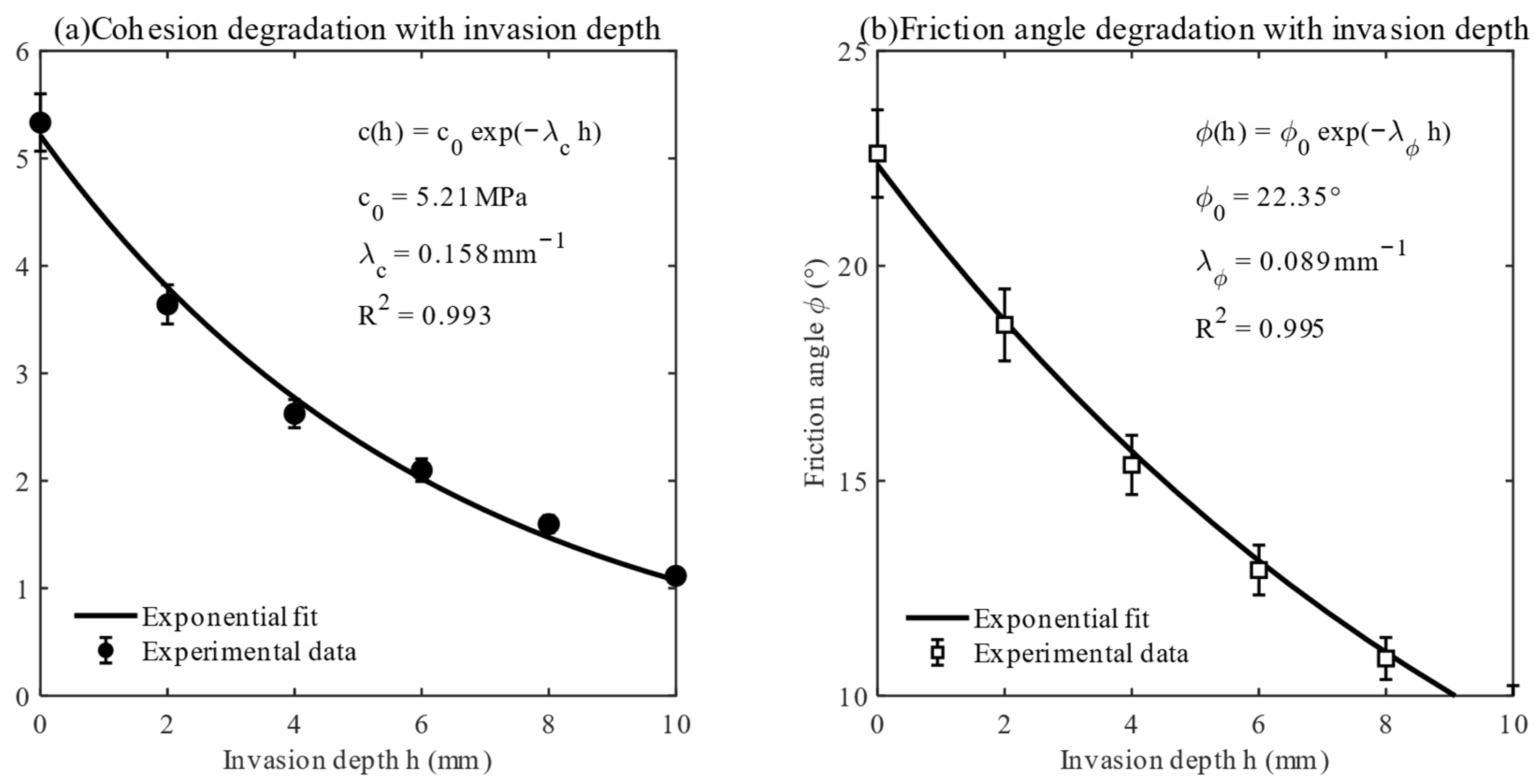

3.2. Results

4. Model Validation

4.1. Experimental Validation

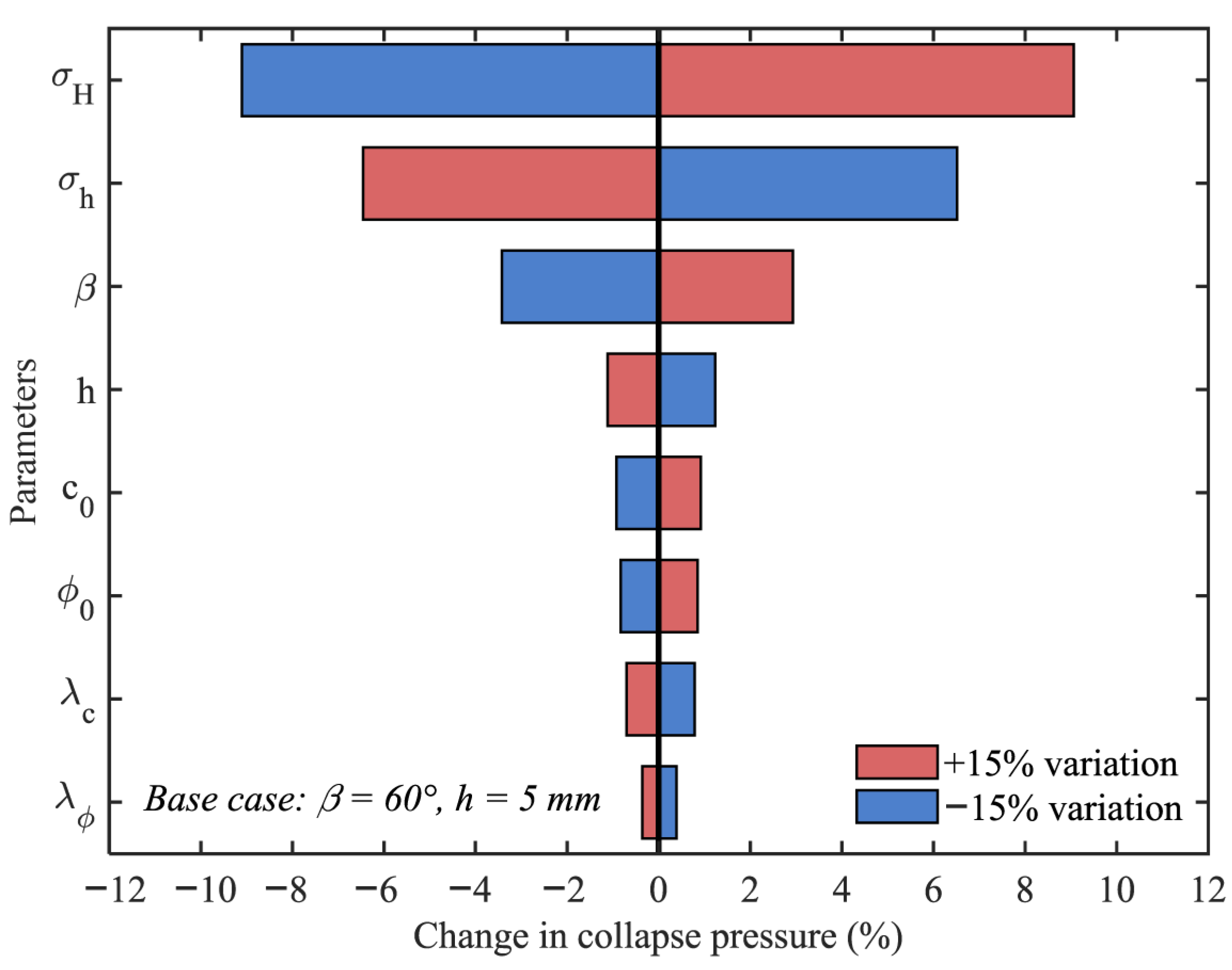

4.2. Parametric Analysis

4.3. Field Case

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Test No. | ΔP (MPa) | t (h) | T2 Peak 1 (ms) | T2 Peak 2 (ms) | T2 Peak 3 (ms) | Signal (a.u.) | Increase (a.u.) | h (mm) | √(ΔP·t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 6 | 2.5 | 34.7 | 112.4 | 970 | 122 | 2.01 | 5.48 |

| 2 | 5 | 12 | 2.5 | 34.6 | 113.4 | 1020 | 172 | 2.84 | 7.75 |

| 3 | 5 | 24 | 2.5 | 34.4 | 114.8 | 1091 | 243 | 4.02 | 10.95 |

| 4 | 5 | 48 | 2.5 | 34.1 | 116.8 | 1191 | 343 | 5.69 | 15.49 |

| 5 | 5 | 72 | 2.5 | 34 | 118.4 | 1267 | 419 | 6.96 | 18.97 |

| 6 | 10 | 6 | 2.5 | 34.6 | 113.4 | 1020 | 172 | 2.84 | 7.75 |

| 7 | 10 | 12 | 2.5 | 34.4 | 114.8 | 1091 | 243 | 4.02 | 10.95 |

| 8 | 10 | 24 | 2.5 | 34.1 | 116.8 | 1191 | 343 | 5.69 | 15.49 |

| 9 | 10 | 48 | 2.5 | 33.8 | 119.6 | 1332 | 484 | 8.04 | 21.91 |

| 10 | 10 | 72 | 2.5 | 33.5 | 121.8 | 1440 | 592 | 9.85 | 26.83 |

| 11 | 15 | 6 | 2.5 | 34.5 | 114.2 | 1058 | 210 | 3.48 | 9.49 |

| 12 | 15 | 12 | 2.5 | 34.3 | 115.9 | 1145 | 297 | 4.92 | 13.42 |

| 13 | 15 | 24 | 2.5 | 34 | 118.4 | 1267 | 419 | 6.96 | 18.97 |

| 14 | 15 | 48 | 2.5 | 33.5 | 121.8 | 1440 | 592 | 9.85 | 26.83 |

| 15 | 15 | 72 | 2.5 | 33.2 | 124.5 | 1573 | 725 | 12.06 | 32.86 |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Du, X.; Jiang, D. Evaluating water-induced wellbore instability in shale formations: A comparative analysis of transversely isotropic strength criteria. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1550266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokir, E.M.; Sallam, S.; Abdelhafiz, M.M. Comprehensive Wellbore Stability Modeling by Integrating Poroelastic, Thermal, and Chemical Effects with Advanced Numerical Techniques. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 51536–51553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, P.; Lan, B. Study of wellbore instability in shale formation considering the effect of hydration on strength weakening. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1403902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, L.; Li, G.; Jiang, Z.; Luo, C. Geomechanical method for wellbore stability prediction: A case study of the Longmaxi formation in the Yongchuan shale gas field, southwestern China. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 35241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, E.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Ma, C. Advanced Trends in Shale Mechanical Inhibitors for Enhanced Wellbore Stability in Water-Based Drilling Fluids. Minerals 2024, 14, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y. Experimental study on the mechanical properties of bedding planes in shale. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 76, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.; Guo, Y.; Yang, C.; Daemen, J.J.; Li, Z. Experimental and theoretical study of the anisotropic properties of shale. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 74, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lin, D.; Zhou, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, J. Study on anisotropic mechanics and acoustic emission response characteristics of layered shale under uniaxial compression. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, B.K.; Regmi, S.; Paudyal, K.; Dahal, D.; Kc, D. Enhancing Deep Excavation Optimization: Selection of an Appropriate Constitutive Model. CivilEng 2024, 5, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, B.; Zhao, P.; Yao, B.; He, L. Influence of multi-planes of weakness on unstable zones near wellbore wall in a fractured formation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 93, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenke, C.; Wei, L.; Hailong, L.; Hai, L. Effect of formation strength anisotropy on wellbore shear failure in bedding shale. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Crandall, D.; Bunger, A.P. Observations of breakage for transversely isotropic shale using acoustic emission and X-ray computed tomography: Effect of bedding orientation, pre-existing weaknesses, and pore water. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 139, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liang, B.; Sun, W.; Zhao, H.; Hao, J.; Hou, M. Experimental study on hydraulic fracturing of bedding shale considering anisotropy effects. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 22698–22713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, Z.; Li, X.; Hou, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, T.; Liang, S. Numerical investigation of bedding plane parameters of transversely isotropic shale. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2017, 50, 1183–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Liu, K.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, J.; Martyushev, D.A.; Ranjith, P.G. Quantitative risk assessment of wellbore collapse of inclined wells in formations with anisotropic rock strengths. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 1795–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, F.; Suo, Y.; Kong, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L. Permeability Characteristics and Strength Degradation Mechanisms of Drilling Fluid Invading Bedding-Shale Fluid. Symmetry 2025, 17, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Q.H.; Song, T.; Zhang, C.; Bin Zhuo, L.; Hao, C.; Feng, F.P.; Wang, H.Y.; et al. The invasion law of drilling fluid along bedding fractures of shale. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1112441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, F.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K. Effects of drilling fluid intrusion on the strength characteristics of layered shale. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Liang, L. Analysis of changes in shale mechanical properties and fault instability activation caused by drilling fluid invasion into formations. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 2343–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, D.-Y.; Zhuang, G.-Z.; Li, X.-L. Advanced development of chemical inhibitors in water-based drilling fluids to improve shale stability: A review. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 1977–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Bao, T.; Sun, P. An insight into shale’s time-dependent brittleness based on the dynamic mechanical characteristics induced by fracturing fluid invasion. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 96, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, P.; Yao, B.; Lv, D. Wellbore stability and failure regions analysis of shale formation accounting for weak bedding planes in ordos basin. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 77, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokhani, V.; Yu, M.; Bloys, B. A wellbore stability model for shale formations: Accounting for strength anisotropy and fluid induced instability. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 32, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Elochukwu, H.; Fakhari, N.; Sarmadivaleh, M. A review on borehole instability in active shale formations: Interactions, mechanisms and inhibitors. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 177, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, M.; Shi, X.; Dai, P.; Zhang, M. Wellbore stability research based on transversely isotropic strength criteria in shale formation. Soils Found. 2024, 64, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, H.; Zhang, T.; Du, X.; Wang, Z. The influence of temperature, seepage and stress on the area and category of wellbore instability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Song, X.; Wang, D.; Ayasrah, M.; Li, S. Poroelastic solutions of a semipermeable borehole under Nonhydrostatic in situ stresses within transversely isotropic media. Int. J. Geomech. 2025, 25, 04024342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.-P.; Tran, N.-H.; Dang, H.-L.; Hoxha, D. Closed-form solution of stress state and stability analysis of wellbore in anisotropic permeable rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2019, 113, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Ma, T.; Peng, N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Ranjith, P. Wellbore stability analysis of inclined wells in transversely isotropic formations accounting for hydraulic-mechanical coupling. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 224, 211615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togashi, Y.; Kikumoto, M.; Tani, K. Determining anisotropic elastic parameters of transversely isotropic rocks through single torsional shear test and theoretical analysis. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 169, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wen, J.; Xu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Feng, J.; Zhao, X. Study of borehole stability of volcanic rock formation with the influence of multiple factors. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 3367–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Chen, P. A wellbore stability analysis model with chemical-mechanical coupling for shale gas reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 26, 72–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ong, S.H.; Azeemuddin, M.; Goodman, H. A wellbore stability model for formations with anisotropic rock strengths. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 96, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Wei, N.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, J.; Kvamme, B.; Coffin, R.B.; Li, H.; Bai, R. Imitating the effects of drilling fluid invasion on the strength behaviors of hydrate-bearing sediments: An experimental study. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 994602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashay, M.; Zirak, M.; Sheng, J.J.; Ganat, T.; Esmaeilnezhad, E. Elevated temperature and pressure performance of water based drilling mud with green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles and biodegradable polymer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M.; Isah, A.; Hiba, M.; Hassan, A.; Al-Garadi, K.; Mahmoud, M.; El-Husseiny, A.; Radwan, A.E. A review on the applications of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in the oil and gas industry: Laboratory and field-scale measurements. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2022, 12, 2747–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Wu, G.; Fu, X.; Xu, C.; Pan, Z. Application of nuclear magnetic resonance technology in reservoir characterization and CO2 enhanced recovery for shale oil: A review. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2025, 37, 107353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Yue, J.; Liu, X.; Sheng, J.; Wang, H. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Quantifies Stress-Dependent Permeability in Shale: Heterogeneous Compressibility of Seepage and Adsorption Pores. Processes 2025, 13, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Xie, R.; Guo, J.; Jin, G. Evaluation of fluid saturation in shale using 2D nuclear magnetic resonance. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 2713–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Gan, R.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yu, P.; Zheng, W.; Song, X.; Xiao, Y. Prediction of Three Pressures and Wellbore Stability Evaluation Based on Seismic Inversion for Well Huqian-1. Processes 2025, 13, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yan, C.; Nie, Z. Chemical effect on wellbore instability of Nahr Umr shale. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 931034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ahmar, R.; Kousa, M.A.A.A.; Al-Helwani, A.; Wardeh, G. Three-Dimensional Site Response Analysis of Clay Soil Considering the Effects of Soil Behavior and Type. CivilEng 2024, 5, 866–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Definition | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| c (h) | Cohesion as a function of invasion depth | MPa |

| c0 | Initial cohesion (non-invaded) | MPa |

| φ (h) | Internal friction angle as a function of invasion depth | ° |

| φ0 | Initial friction angle (non-invaded) | ° |

| λc | Cohesion degradation coefficient | mm−1 |

| λφ | Friction angle degradation coefficient | mm−1 |

| h | Invasion depth | mm |

| α | Invasion coefficient | mm/(MPa0.5·h0.5) |

| ΔP | Pressure differential (wellbore minus formation) | MPa |

| t | Time since drilling fluid exposure | h |

| Pc | Collapse pressure | MPa |

| σ’n | Effective normal stress on bedding plane | MPa |

| τ | Shear stress on bedding plane | MPa |

| Mineral | Content (%) | Mineral | Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz | 35.2 | Clay minerals | 42.6 |

| Calcite | 15.8 | - Illite | 28.4 |

| Feldspar | 4.2 | - Chlorite | 10.2 |

| Pyrite | 2.2 | - Kaolinite | 4.0 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial cohesion (β = 45°) | c0 | 5.21 | MPa | 0.993 |

| Initial friction angle (β = 45°) | φ0 | 22.35 | ° | 0.995 |

| Cohesion degradation coefficient | λc | 0.158 | mm−1 | - |

| Friction angle degradation coefficient | λφ | 0.089 | mm−1 | - |

| Comprehensive invasion coefficient | α | 0.367 | mm/(MPa0.5·h0.5) | 0.980 |

| Maximum shear strength (β = 0°) | τmax | 24.3 | MPa | - |

| Minimum shear strength (β = 45°) | τmin | 8.2 | MPa | - |

| Anisotropy ratio | - | 2.96 | - | - |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well depth range | - | 2800–3000 | m | Field data |

| Maximum horizontal stress | 58 | MPa | Logging analysis | |

| Minimum horizontal stress | 48 | MPa | Logging analysis | |

| Pore pressure | 35 | MPa | MDT test | |

| Drilling fluid density | 1.15 | g/cm3 | Field record | |

| Pressure differential | 10 | MPa | Calculated | |

| Initial cohesion | 5.21 | MPa | Laboratory test | |

| Initial friction angle | 22.35 | ° | Laboratory test | |

| Cohesion degradation coefficient | 0.158 | mm−1 | This study | |

| Friction angle degradation coefficient | 0.089 | mm−1 | This study | |

| Invasion coefficient | 0.367 | mm/(MPa0.5·h0.5) | This study | |

| Bedding angle range | 42–46 | ° | Image logging | |

| Young’s modulus (parallel to bedding) | 28.5 | GPa | Laboratory test | |

| Young’s modulus (perpendicular to bedding) | 24.3 | GPa | Laboratory test | |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.22 | - | Laboratory test |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Geng, Y.; Yu, B.; Meng, S.; Wang, L. Collapse Pressure Prediction for Marine Shale Wellbores Considering Drilling Fluid Invasion-Induced Strength Degradation: A Bedding Plane Slip Model. Eng 2025, 6, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120353

Zhang Z, Li C, Geng Y, Yu B, Meng S, Wang L. Collapse Pressure Prediction for Marine Shale Wellbores Considering Drilling Fluid Invasion-Induced Strength Degradation: A Bedding Plane Slip Model. Eng. 2025; 6(12):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120353

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhilei, Chunping Li, Yuan Geng, Baohua Yu, Sicong Meng, and Lihui Wang. 2025. "Collapse Pressure Prediction for Marine Shale Wellbores Considering Drilling Fluid Invasion-Induced Strength Degradation: A Bedding Plane Slip Model" Eng 6, no. 12: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120353

APA StyleZhang, Z., Li, C., Geng, Y., Yu, B., Meng, S., & Wang, L. (2025). Collapse Pressure Prediction for Marine Shale Wellbores Considering Drilling Fluid Invasion-Induced Strength Degradation: A Bedding Plane Slip Model. Eng, 6(12), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120353