Engineering Auditory Cues for Gait Modulation: Effects of Continuous and Discrete Sound Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Discrete Rhythmic vs. Continuous Cues

1.2. Tempi

- Identify whether sound continuity enhances or disrupts natural gait synchronization.

- Examine whether walking pace naturally aligns with faster auditory rhythms and whether slower rhythms induce measurable gait slowing.

- Explore whether combining discrete and continuous cues produces any effects on gait.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Auditory Cue Design

2.4. Gait Data Acquisition

2.5. Procedure

- Silent baseline (self-paced);

- Auditory-cue trials (DAF, CAF, and DAF + CAF) at 60 BPM and 120 BPM, presented in random order.

- Which individual sounds had the most impact on your general movement during the experiment?

- Which tempo of the sounds played had the greatest influence on your general movement and speed?

- Which sound type, discrete (bell tone) or continuous (sawtooth tone), had a more substantial effect on your general movement?

2.6. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

2.7. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.8. Normalization

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Auditory Cues on Gait

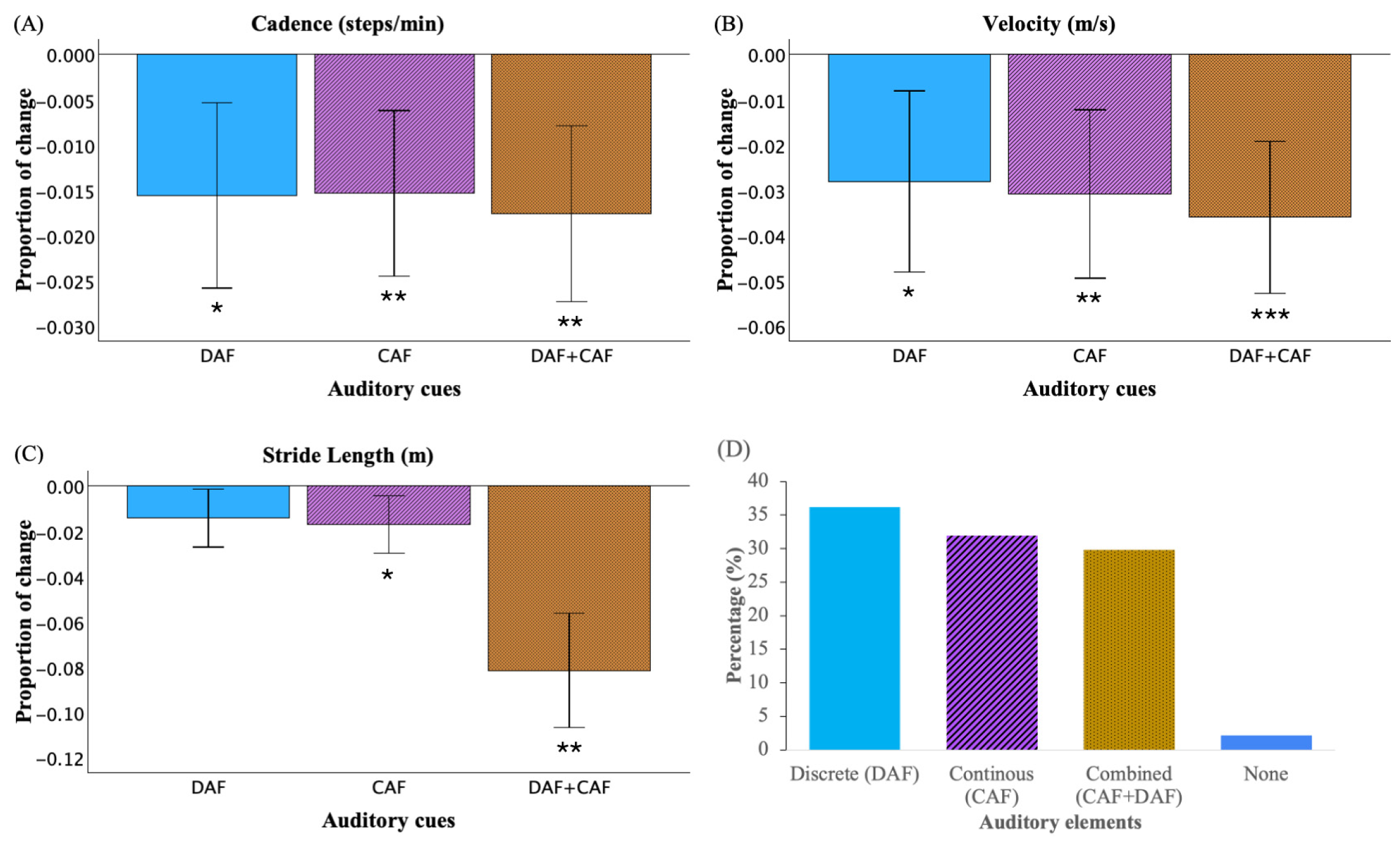

3.2. Auditory Feature Comparisons

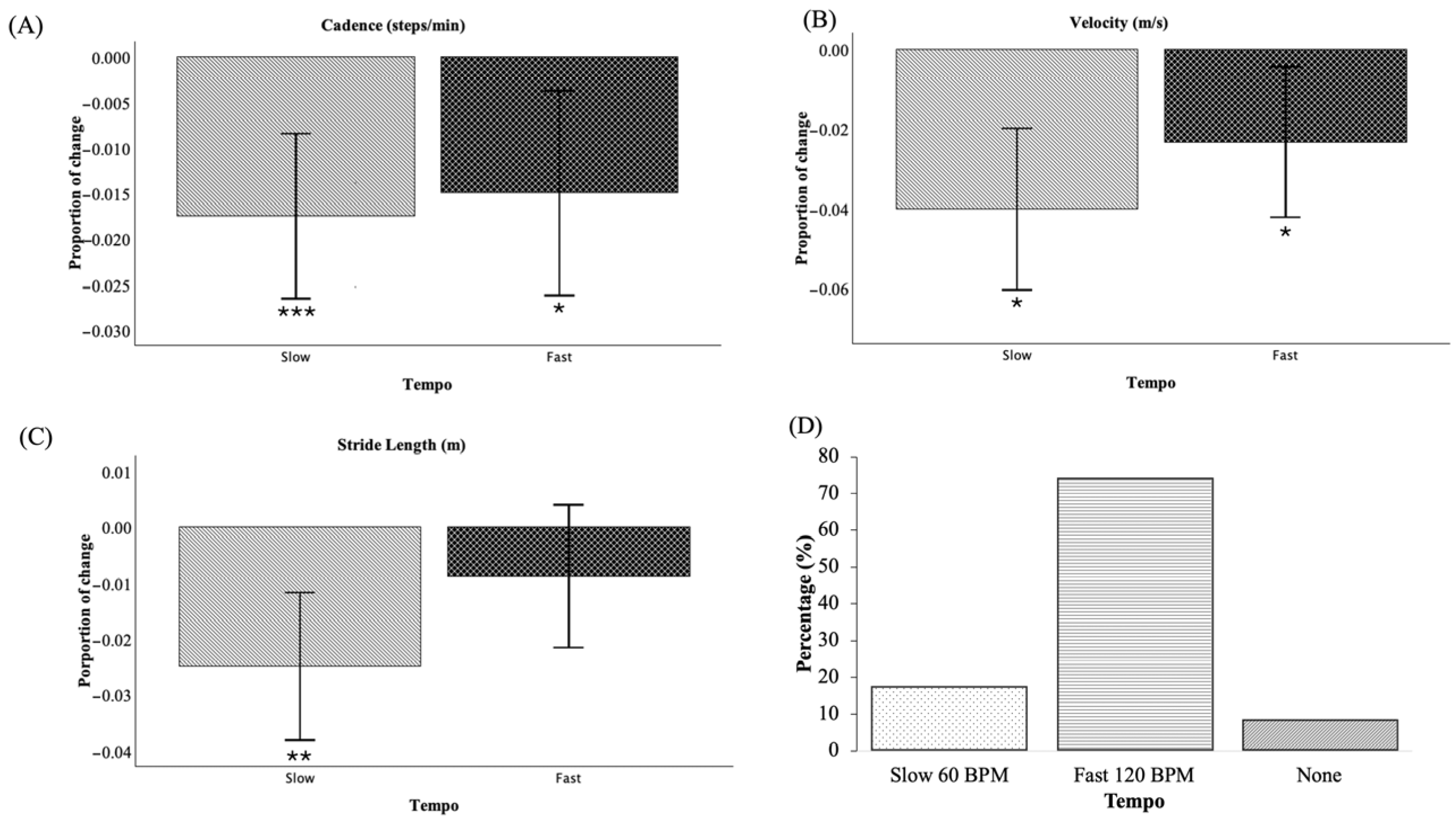

3.3. Influence of Sound Tempo

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Rhythmic and Continuity Features

4.2. Influence of Tempo

4.3. Interaction Between Discrete and Continuous Cues

4.4. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baram, Y.; Aharon-Peretz, J.; Badarny, S.; Susel, Z.; Schlesinger, I. Closed-loop auditory feedback for the improvement of gait in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 363, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, Y.; Lenger, R. Gait Improvement in Patients with Cerebral Palsy by Visual and Auditory Feedback. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 2012, 15, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, Y.-J.; Kim, J.-D.; Choi, Y.-R.; Kim, N.-H.; Son, S.-M. Effects of gait training with auditory feedback on walking and balancing ability in adults after hemiplegic stroke: A preliminary, randomized, controlled study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2018, 41, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwell, T.; Woodward, J.; Wu, M.M.; Jackson, B.; Souza, P.; Siegel, J.; Dhar, S.; Gordon, K.E. Walking With Ears: Altered Auditory Feedback Impacts Gait Step Length in Older Adults. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, N.; Takeda, K.; Sakuma, M.; Mani, H.; Maejima, H.; Asaka, T. Learning effects of dynamic postural control by auditory biofeedback versus visual biofeedback training. Gait Posture 2017, 58, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, K.-I.; Kim, M.-S.; Moon, Y.; Choi, J.-D. Effects of auditory feedback during gait training on hemiplegic patients’ weight bearing and dynamic balance ability. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1267–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashael Abd El-Salam Mohamed, N.; Amira Mohamed, E.; Nanees Essam Mohamed, S. Influence of rhythmic auditory feedback on gait in hemiparetic children. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulucci, R.A.; Eckhouse, R.H. A real-time auditory feedback system for retraining gait. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Boston, MA, USA, 30 August–3 September 2011; pp. 5199–5202. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, T.Y.; Feltham, F. Effect of continuous auditory feedback (CAF) on human movements and motion awareness. Med. Eng. Phys. 2022, 109, 103902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.L.Y.; Murphy, A.; Chen, C.; Kulić, D. Adaptive cueing strategy for gait modification: A case study using auditory cues. Front. Neurorobotics 2023, 17, 1127033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, É.O.; Bevilacqua, F.; Susini, P.; Hanneton, S. Investigating three types of continuous auditory feedback in visuo-manual tracking. Exp. Brain Res. 2017, 235, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, G.; Oscari, F.; Spagnol, S.; Avanzini, F.; Masiero, S. Effect of task-related continuous auditory feedback during learning of tracking motion exercises. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffert, N.; Janzen, T.B.; Mattes, K.; Thaut, M.H. A Review on the Relationship Between Sound and Movement in Sports and Rehabilitation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, J.E.; Webster, K.E.; Hill, K. Music and metronome cues produce different effects on gait spatiotemporal measures but not gait variability in healthy older adults. Gait Posture 2013, 37, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathy, C.; Marta, M.N.B. Sound, Music and Movement in Parkinson’s Disease; Frontiers Media SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moumdjian, L.; Moens, B.; Maes, P.-J.; Van Geel, F.; Ilsbroukx, S.; Borgers, S.; Leman, M.; Feys, P. Continuous 12 min walking to music, metronomes and in silence: Auditory-motor coupling and its effects on perceived fatigue, motivation and gait in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 35, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.-B.; Ryu, H.J. Effects of gait training with rhythmic auditory stimulation on gait ability in stroke patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 1403–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzeh, J.; Baradhi, M.C.; Al Neyadi, S.; Ballout, M.; Ayoubi, F. The effect of rhythmic auditory stimulation variation on gait parameters in chronic stroke patients: A pilot study. Gait Posture 2021, 90, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tueth, L.E.; Haussler, A.M.; Lohse, K.R.; Rawson, K.S.; Earhart, G.M.; Harrison, E.C. Effect of musical cues on gait in individuals with Parkinson disease with comorbid dementia. Gait Posture 2024, 107, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgia, M.; Pili, R.; Corona, F.; Sors, F.; Agostini, T.A.; Bernardis, P.; Casula, C.; Cossu, G.; Guicciardi, M.; Pau, M. The use of footstep sounds as rhythmic auditory stimulation for gait rehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lheureux, A.; Warlop, T.; Cambier, C.; Chemin, B.; Stoquart, G.; Detrembleur, C.; Lejeune, T. Influence of Autocorrelated Rhythmic Auditory Stimulations on Parkinson’s Disease Gait Variability: Comparison With Other Auditory Rhythm Variabilities and Perspectives. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 601721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun Janzen, T.; Schaffert, N.; Schlüter, S.; Ploigt, R.; Thaut, M.H. The effect of perceptual-motor continuity compatibility on the temporal control of continuous and discontinuous self-paced rhythmic movements. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2021, 76, 102761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, N.; Svensson, U.P. Dynamic Systems Approach in Sensorimotor Synchronization: Adaptation to Tempo Step-Change. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 667859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlet, M.; Marin, L.; Issartel, J.; Schmidt, R.C.; Bardy, B.G. Continuity of Visual and Auditory Rhythms Influences Sensorimotor Coordination. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delval, A.; Moreau, C.; Bleuse, S.; Tard, C.; Ryckewaert, G.; Devos, D.; Defebvre, L. Auditory cueing of gait initiation in Parkinson’s disease patients with freezing of gait. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 1675–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun Janzen, T.; Koshimori, Y.; Richard, N.M.; Thaut, M.H. Rhythm and Music-Based Interventions in Motor Rehabilitation: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 789467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebb, C.; Raynor, G.; Perez, D.L.; Nappi-Kaehler, J.; Polich, G. The use of rhythmic auditory stimulation for functional gait disorder: A case report. NeuroRehabilitation 2022, 50, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Fu, J. Integrating rhythmic auditory stimulation in intelligent rehabilitation technologies for enhanced post-stroke recovery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1649011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scataglini, S.; Van Dyck, Z.; Declercq, V.; Van Cleemput, G.; Struyf, N.; Truijen, S. Effect of Music Based Therapy Rhythmic Auditory Stimulation (RAS) Using Wearable Device in Rehabilitation of Neurological Patients: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvonen, A.J.; Särkämö, T.; Leo, V.; Tervaniemi, M.; Altenmüller, E.; Soinila, S. Music-based interventions in neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, P.-J.; Buhmann, J.; Leman, M. 3Mo: A Model for Music-Based Biofeedback. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, E.A.; Holmes, J.D.; Grahn, J.A. Gait in younger and older adults during rhythmic auditory stimulation is influenced by groove, familiarity, beat perception, and synchronization demands. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2022, 84, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Hass, C.J.; Janelle, C.M. Familiarity with music influences stride amplitude and variability during rhythmically-cued walking in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 2021, 87, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.S.; Ready, E.A.; Grahn, J.A. Musical enjoyment does not enhance walking speed in healthy adults during music-based auditory cueing. Gait Posture 2021, 89, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashoori, A.; Eagleman, D.M.; Jankovic, J. Effects of auditory rhythm and music on gait disturbances in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodger, M.W.M.; Craig, C.M. Beyond the Metronome: Auditory Events and Music May Afford More than Just Interval Durations as Gait Cues in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, R.; Studenka, B.E.; Rheaume, N.L.; Zelaznik, H.N.; Jirsa, V.K. Distinct timing mechanisms produce discrete and continuous movements. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, R.S. Auditory rhythmic cueing in movement rehabilitation: Findings and possible mechanisms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun Janzen, T.; Thompson, W.F.; Ammirante, P.; Ranvaud, R. Timing skills and expertise: Discrete and continuous timed movements among musicians and athletes. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, M.W.M.; Craig, C.M. Moving with Beats and Loops: The Structure of Auditory Events and Sensorimotor Timing. In Sound, Music, and Motion, Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium, CMMR 2013, Marseille, France, 15–18 October 2013; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Feltham, F.; Connelly, T.; Cheng, C.-T.; Pang, T.Y. A Wearable Sonification System to Improve Movement Awareness: A Feasibility Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I.; Effenberg, A.O. Effect of Rhythmic Auditory Cueing on Aging Gait: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 901–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, E.O.; Portron, A.; Bevilacqua, F.; Lorenceau, J. Continuous auditory feedback of eye movements: An exploratory study toward improving oculomotor control. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delignières, D.; Torre, K. Event-Based and Emergent Timing: Dichotomy or Continuum? A Reply to Repp and Steinman (2010). J. Mot. Behav. 2011, 43, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, B.H.; Steinman, S.R. Simultaneous Event-Based and Emergent Timing: Synchronization, Continuation, and Phase Correction. J. Mot. Behav. 2010, 42, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Su, Q.; Xie, J.; Su, H.; Huang, T.; Han, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, K.; Xu, G. Music tempo modulates emotional states as revealed through EEG insights. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreepetch, S.; Ramyarangsi, P.; Mukda, S.; Siripornpanich, V.; Ajjimaporn, A. Recovery effects of slow-tempo preferred music on brain activity, physiological and psychological responses following high-intensity interval exercise in healthy male adults. Acta Psychol. 2025, 259, 105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Nam, S.M.; Seo, H. Impact of sensory modality and tempo in motor timing. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1419135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Tello, S.; Romo-Vázquez, R.; González-Garrido, A.A.; Ramos-Loyo, J. Musical tempo affects EEG spectral dynamics during subsequent time estimation. Biol. Psychol. 2023, 178, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbinaga, F.; Romero-Pérez, N.; Torres-Rosado, L.; Fernández-Ozcorta, E.J.; Mendoza-Sierra, M.I. Influence of Music on Closed Motor Skills: A Controlled Study with Novice Female Dart-Throwers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, E.A.; McGarry, L.M.; Rinchon, C.; Holmes, J.D.; Grahn, J.A. Beat perception ability and instructions to synchronize influence gait when walking to music-based auditory cues. Gait Posture 2019, 68, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, K.; Wang, W.; Tuo, H.; Long, Y.; Tan, X.; Sun, W. Personalized auditory cues improve gait in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1561880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochen De Cock, V.; Dotov, D.; Damm, L.; Lacombe, S.; Ihalainen, P.; Picot, M.C.; Galtier, F.; Lebrun, C.; Giordano, A.; Driss, V.; et al. BeatWalk: Personalized Music-Based Gait Rehabilitation in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagala, A.; Foster, N.E.V.; van Vugt, F.T.; Dal Maso, F.; Dalla Bella, S. The Ramp protocol: Uncovering individual differences in walking to an auditory beat using TeensyStep. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.L.Y.; Murphy, A.; Chen, C.; Kulić, D. Adaptive auditory assistance for stride length cadence modification in older adults and people with Parkinson’s. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1284236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franěk, M.; van Noorden, L.; Režný, L. Tempo and walking speed with music in the urban context. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.R.; Boening, A.; Rocha, R.J.S.; do Carmo, W.A.; Ada, L. Walking training with auditory cueing improves walking speed more than walking training alone in ambulatory people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2024, 70, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasseel-Ponche, S.; Delafontaine, A.; Godefroy, O.; Yelnik, A.P.; Doutrellot, P.-L.; Duchossoy, C.; Hyra, M.; Sader, T.; Diouf, M. Walking speed at the acute and subacute stroke stage: A descriptive meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 989622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.; McManigal, M.; Post, A.; Werner, D.; Wichman, C.; Tao, M.; Wellsandt, E. Reliability of an Instrumented Pressure Walkway for Measuring Walking and Running Characteristics in Young, Athletic Individuals. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2024, 19, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.J.; Chun, M.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.Y. Effects of robot (SUBAR)-assisted gait training in patients with chronic stroke: Randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2021, 100, e27974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winiarski, S.; Pietraszewska, J.; Pietraszewski, B. Three-Dimensional Human Gait Pattern: Reference Data for Young, Active Women Walking with Low, Preferred, and High Speeds. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9232430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Auditory Conditions | Reported Experience Theme | Example of Participant Excerpts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow | DAF | Confusing | It is too slow and it makes it harder to walk to the speed of it. |

| CAF | Confusing | The saw felt odd, as it had little to no rhythm; your footsteps could not align with the sound. | |

| DAF + CAF | Disorientating | […] the sound felt disoriented and impeded my walking rhythm. | |

| Fast | DAF | Appealing rhythm | Matches best with walking speed and building consistent stride. |

| CAF | Appealing rhythm | It was the easiest sound to match my walking to, felt the most natural to walk with. | |

| DAF + CAF | Disorientating | Disliked the bell and saw combined sounds—found them distracting and unnatural. | |

| Variables | Baseline | Slow | Fast | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAF | CAF | DAF + CAF | DAF | CAF | DAF + CAF | ||

| Cadence (steps/min) | 114.2 ± 6.3 | 112.0 ± 7.7 | 112.3 ± 7.2 | 112.5 ± 7.4 | 112.9 ± 8.1 | 112.7 ± 7.4 | 112.0 ± 7.4 |

| Velocity (m/s) | 1.37 ± 0.15 | 1.31 ± 0.17 | 1.31 ± 0.16 | 1.31 ± 0.16 | 1.35 ± 0.16 | 1.34 ± 0.16 | 1.32 ± 0.16 |

| Stride length (m) | 1.43 ± 0.15 | 1.40 ± 0.14 | 1.40 ± 0.14 | 1.40 ± 0.14 | 1.43 ± 0.13 | 1.42 ± 0.14 | 1.41 ± 0.14 |

| Gait Variables | Paired Samples | Mean Difference (SD) | 95% CI of the Difference | t | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Cadence (steps/min) | Baseline-DAF | 1.76 (3.36) | 0.60 | 2.91 | 3.09 | 0.52 | 0.004 |

| Baseline-CAF | 1.74 (3.00) | 0.71 | 2.78 | 3.43 | 0.58 | 0.002 | |

| Baseline-DAF + CAF | 1.99 (3.20) | 0.89 | 3.09 | 3.69 | 0.62 | <0.001 | |

| Velocity (m/s) | Baseline-DAF | 0.040 (0.081) | 0.012 | 0.068 | 2.93 | 0.50 | 0.006 |

| Baseline-CAF | 0.044 (0.076) | 0.018 | 0.070 | 3.43 | 0.58 | 0.002 | |

| Baseline-DAF + CAF | 0.050 (0.068) | 0.026 | 0.073 | 4.33 | 0.73 | <0.001 | |

| Stride length (m) | Baseline-DAF | 0.022 (0.056) | 0.003 | 0.041 | 2.37 | 0.40 | 0.023 |

| Baseline-CAF | 0.026 (0.055) | 0.007 | 0.045 | 2.84 | 0.48 | 0.008 | |

| Baseline-DAF + CAF | 0.029 (0.048) | 0.012 | 0.045 | 3.57 | 0.60 | 0.001 | |

| Gait Variables | Paired Samples | Mean Difference (SD) | 95% CI of the Difference | t | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Cadence (steps/min) | Baseline-Slow | 1.96 (2.95) | 0.95 | 2.98 | 3.93 | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Baseline-Fast | 1.70 (3.70) | 0.43 | 2.97 | 2.72 | 0.46 | 0.01 | |

| Velocity (m/s) | Baseline-Slow | 0.056 (0.082) | 0.028 | 0.084 | 4.02 | 0.68 | <0.001 |

| Baseline-Fast | 0.034 (0.076) | 0.007 | 0.060 | 2.61 | 0.44 | 0.013 | |

| Stride length (m) | Baseline-Slow | 0.037 (0.058) | 0.017 | 0.057 | 3.79 | 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Baseline-Fast | 0.014 (0.054) | −0.004 | 0.033 | 1.57 | 0.26 | 0.126 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, T.Y.; Feltham, F.; Cheng, C.-T. Engineering Auditory Cues for Gait Modulation: Effects of Continuous and Discrete Sound Features. Eng 2025, 6, 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120349

Pang TY, Feltham F, Cheng C-T. Engineering Auditory Cues for Gait Modulation: Effects of Continuous and Discrete Sound Features. Eng. 2025; 6(12):349. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120349

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Toh Yen, Frank Feltham, and Chi-Tsun Cheng. 2025. "Engineering Auditory Cues for Gait Modulation: Effects of Continuous and Discrete Sound Features" Eng 6, no. 12: 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120349

APA StylePang, T. Y., Feltham, F., & Cheng, C.-T. (2025). Engineering Auditory Cues for Gait Modulation: Effects of Continuous and Discrete Sound Features. Eng, 6(12), 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120349