1. Introduction

A significant number of high dams have been constructed in China over the past few decades, which are characterized by substantial water heads, large flow capacities, deep and narrow valleys, and considerable flood discharge capabilities. This evolution has sparked considerable interest in various critical issues, including energy dissipation, scour protection, vibration control of hydraulic structures, vapor atomization protection, aeration for cavitation prevention, and security warning systems for high dam flood discharge. These challenges have consequently led to noteworthy technological advancements in the field [

1,

2,

3,

4].

However, recent investigations have highlighted environmental concerns associated with flood discharge noise around certain hydropower stations, particularly during flood discharge events. A pertinent example is the Xiangjiaba Hydropower Station, located at the border of Sichuan and Yunnan Provinces in China. On 10 October 2012, residents of Shui Fu County reported continuous flood discharge noise from the dam’s spillway, which disrupted their daily activities and rest. Additionally, the rolling shutters of commercial establishments and doors and windows of residential buildings experienced persistent vibrations. These complaints are consistent with the wide-ranging individual impacts of low-frequency noise (LFN) documented by Erdélyi et al. [

5], who reported prevalent issues, such as sleep disturbances, fatigue, and annoyance, among populations exposed to LFN. This underscores the complex interplay between hydropower operations and their environmental impacts, warranting further research and the development of mitigation strategies.

The noise generated during high dam flood discharge is predominantly low-frequency, lasting for extended periods and propagating over wide areas. Numerous studies indicate a clear correlation between noise pollution and a decline in the quality of life of affected individuals [

6,

7]. Critically, the environmental impact of LFN is often underestimated by conventional A-weighted noise metrics. As demonstrated by Leaffer et al. [

8] through long-term urban measurements, LFN exhibits distinct spatiotemporal trends and can be a significant, yet frequently overlooked, environmental stressor. Therefore, the flood discharge noise from high dams constitutes a significant environmental challenge to human health and well-being. Due to the commission of high-head and large-flow hydraulic projects, the environmental impact of flood discharge noise has become increasingly pronounced.

Japanese researchers have extensively studied the noise impacts of flood discharge, which is driven by the country’s dense population and the proximity of hydropower stations to residential areas. Early recognition of flood discharge noise hazards is notable. Takebayashi et al. [

9,

10,

11,

12] conducted systematic field observations and investigated vibration mechanisms and control measures, including the self-excited vibration mechanism of water curtain cavities. Izumi [

13,

14] studied the noise characteristics of various hydraulic energy dissipators using model tests. Ochiai et al. [

15] focused on sound pressure levels that cause structural rattling. Saitoh et al. [

16] examined noise sources from hydraulic jumps and jet nozzles, linking noise to bubble resonance. Murakawa et al. [

17] researched noise control for automated gates, and Goto et al. [

18] proposed sloped flows for noise reduction. Complementing these efforts, Pepper [

19] addressed noise reduction at a low-head vertical-drop spillway through model testing and field implementation, demonstrating practical engineering solutions for mitigating nappe-induced noise. These studies collectively indicate that flood discharge noise poses environmental hazards and is closely linked to flow conditions, suggesting that flow modification can mitigate its impacts.

Research has also advanced understanding of the mechanisms of hydrodynamic noise generation. Li [

20] proposed a reverberation tank method for the assessment of underwater sound power. Hu Zhihua [

21,

22] investigated the mechanisms of noise in low-velocity flows. Gu Jinde [

23] developed a generalized noise model for jet flow discharge. Zhang Wenjiao [

24] and Wang Peng [

25] focused on low-frequency waves and prototype observations, respectively. Lian Jijian [

26] developed a mathematical model based on vortex sound theory. Building on this foundation, Lian [

27] further proposed multi-source generation mechanisms for ski-jump spillways, identifying both plunge-pool energy dissipation and nappe-cavity-coupled vibration as key sources with distinct spectral characteristics. In a significant methodological advancement, Lian [

28] developed an improved blind source separation algorithm to accurately identify and locate multiple low-frequency noise sources during flood discharge, addressing the critical challenge of source identification in complex prototype environments. Parallel to these mechanistic studies, Wang Xiaoqun [

29] conducted numerical simulations to predict LFN downstream of a tunnel spillway based on vortex sound theory, providing a viable approach for pre-construction environmental impact assessment.

Despite these valuable contributions, current research on the propagation patterns, mechanisms, prediction models, and analysis of noise sources from high dam discharge remains limited, particularly in comprehensive sound field modeling that integrates multiple source types and their interactions. A systematic framework for classifying acoustic sources and quantitatively predicting the sound field under various operational scenarios remains to be developed. This gap is particularly urgent for hydraulic projects near residential areas, where discharge noise significantly affects residents’ quality of life. Further research is essential to optimize scheduling and mitigate the impacts of noise on the surrounding environment.

The primary contributions of this study, relative to the existing body of literature, are as follows:

1. Development of a multi-source sound field propagation model: In this study, we establish a comprehensive flood discharge sound field model that systematically integrates and quantifies noise contributors using different geometric classifications of acoustic sources (point, line, and surface sources). This model achieves prediction accuracy within 1.5 dB when validated against prototype data, offering a significant advancement in predictive capability over previous models.

2. Three-dimensional acoustic source classification and quantification: In this study, we propose and implement a novel three-dimensional framework for classifying flood discharge noise sources based on their acoustic source morphology (point, line, and surface). Crucially, this framework is quantified using a regression algorithm that disentangles and quantifies the individual contributions of these source types (point, line, and surface) using holistic sound field measurements. This approach provides a more precise, physically meaningful representation of the complex sound-generating processes during flood discharge, moving beyond simpler, less descriptive source representations.

3. Integrated prototype and model-based analysis for operational response: By synergistically combining detailed prototype observations with controlled hydraulic model tests, we quantitatively analyzed the correlation between specific spillway operations (e.g., surface vs. bottom spillway usage) and the resulting noise levels. This integrated approach provides a robust basis for formulating noise-aware operational strategies, a critical need for dam operators near populated areas.

This study investigates the propagation patterns, mechanisms, prediction models, and acoustic source analysis of noise generated by high dam spillway discharge, using the Xiangjiaba Hydropower Station as the research subject. Xiangjiaba Hydropower Station is located in Yunnan Province, China, with a dense residential area situated 1 km downstream. Consequently, its flood discharge noise has received widespread attention from various sectors of society. The dam is 162 m high, with energy dissipation structures located in the middle of the riverbed on the right bank. It features 10 bottom spillways (numbered #1 to #10, from left to right) and 12 surface spillways (numbered #1 to #12, from left to right), arranged alternately. The design employs a submerged hydraulic jump for energy dissipation, with the stilling basin divided into two symmetrical flood discharge areas by a partition wall. The maximum discharge capacity is 2399 m3/s for a single surface spillway and 1987 m3/s for a single bottom spillway. The surface spillways utilize open-channel overflow weirs, with the control section at the weir crest measuring 8 m × 26 m (width × height).

2. Methodology

This study begins with prototype observations to identify the distribution patterns of flood discharge noise. Subsequently, an overall model test is conducted, calibrating the model’s noise measurements with the prototype data to establish a correlation. Multiple experiments are conducted under varying conditions, and regression analysis of the measured noise data is used to develop a flood discharge sound field model, which is subsequently validated against prototype observations. Finally, the model is used to analyze noise sources, leading to the proposal of principles and strategies to reduce spillway noise.

2.1. Prototype Observation

Flood discharge noise was measured using the Hangzhou Aihua AWA6292 multi-function sound level meter (Hangzhou Aihua Instruments Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). To ensure measurement accuracy, the instrument was calibrated within one week prior to each use with a Hangzhou Aihua acoustic calibrator (Model: 6223), ensuring that the deviation between two consecutive calibrations did not exceed 0.5 dB. The main performance indicators of the AWA6292 multi-functional sound level meter are summarized in

Table 1.

A total of 51 measurement points were established at the prototype observation site, including 12 on the dam crest, 5 in the power station plant, 6 on the left bank, 3 on the downstream bridge, and 25 in the downstream residential area. The measurement points in the downstream residential area included the right-bank viewing platform, residential communities, schools, and hospitals, as shown in

Figure 1.

Two sets of prototype observations were conducted; the conditions are as follows:

Prototype observation condition 1: #1~#5 bottom spillway gates opened to 1 m and #1~#6 surface spillway gates opened to 2 m, with a total flow rate of 8880 m3/s.

Prototype observation condition 2: #1~#5 bottom spillway gates opened to 3 m and #1~#6 surface spillway gates opened to 4 m; #8 to #11 surface spillway gates open to 2 m, with a total flow rate of 12,680 m3/s.

To reduce the influence of ambient noise on flood discharge noise monitoring, observations were conducted during late night and early morning hours.

2.2. Hydraulic Model Test

Due to limited opportunities for prototype observation, which resulted in a constrained number of measurable conditions and difficulty in conducting close-range measurements of flood discharge noise from various energy dissipation structures, this study conducted a comprehensive investigation under different operating conditions using a 1:75 scale model of the Xiangjiaba project. The 1:75 scale model is shown in

Figure 2. The model was positioned more than 20 m from the walls and 8 m from the ceiling of the test hall. Additionally, the terrain on both sides of the model’s stilling basin was simulated using materials with sound-absorbing properties. This site arrangement significantly mitigated the effects of environmental reverberation during testing. In the experiment, a total of 7 flood discharge noise measurement points were set: 3 on the dam crest, 3 on the partition wall of the stilling basin, and 1 at the viewing platform on the right bank, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Model tests replicated field observation conditions, revealing that flood discharge noise measurements from both methods exhibit similar patterns. Noise characteristics measured in the model under various conditions align with prototype observations. The prototype spillway’s noise intensity is about 150 times that of the model tests. Thus, model test observations can reflect relative patterns of flood discharge noise and serve as a basis for constructing a flood discharge sound field model.

Model tests were conducted to replicate field observation conditions. However, acoustic similarity between the prototype and the 1:75-scale model requires careful consideration of frequency scaling and air attenuation. To address this, the acoustic scaling in this study was guided by the Strouhal number (

), a key dimensionless parameter in fluid dynamics that characterizes the periodicity of flow-induced phenomena, such as vortex shedding and the resulting sound generation [

30,

31]. The Strouhal number is defined as

, where

is the frequency,

is a characteristic length (e.g., spillway opening), and

is the characteristic flow velocity. For dynamic similarity, the Strouhal number must be conserved between the model and the prototype.

Consequently, the frequencies measured in the model () were converted to their prototype equivalents () using the scaling factor , where is the length scale ratio. This results in a frequency scaling factor of approximately 8.7, meaning model frequencies are scaled down by this factor to represent the prototype condition.

The sound intensity also requires scaling. The prototype spillway noise’s sound intensity was approximately 150 times greater than that in the model tests, consistent with the theoretical scaling of sound power with the square of the length scale for geometrically and dynamically similar sources.

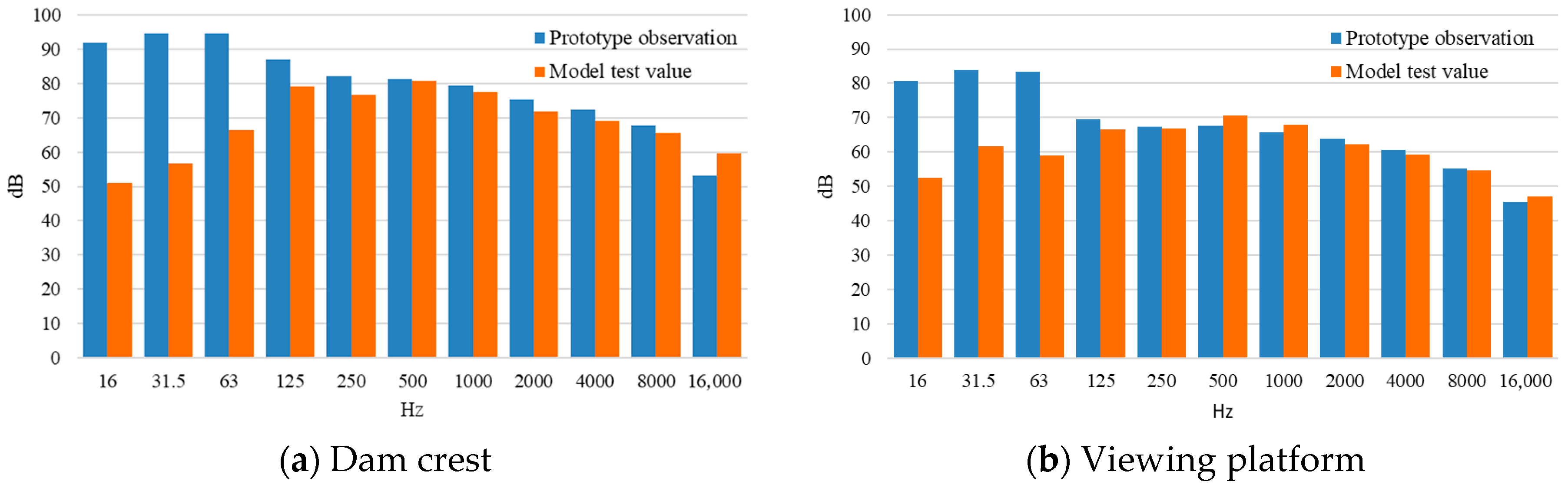

The validity of this acoustic scaling approach is confirmed by the spectral comparison between prototype observations and scaled model data under Condition 1, as shown in

Figure 3. The dominant frequency of the prototype noise is in the 30–60 Hz range, while the raw model data peaks in the mid-frequency range (~500 Hz). After applying the frequency scaling factor of 8.7, the scaled model spectrum aligns well with the prototype observations in the low-frequency band. This confirms that model test observations, after proper acoustic scaling, can accurately reflect the relative patterns of flood discharge noise and provide a reliable basis for constructing the flood discharge sound field model.

2.3. Development of the Multi-Source Sound Field Model

2.3.1. Acoustic Theory Fundamentals

The conventional method for characterizing noise, the weighted sound pressure level (decibel), reflects the human ear’s perception but does not accurately represent the sound energy distribution within the sound field. Sound pressure (Pa) is required for a precise representation of sound energy.

The human ear detects sound pressure fluctuations from 2 × 10−5 Pa to 20 Pa, corresponding to 0–120 dB. The vast range of sound pressure makes direct expression impractical. To simplify, and considering the ear’s logarithmic response to sound intensity, sound pressure is converted into sound pressure levels () in decibels, enabling a more convenient characterization.

The sound pressure level is defined as the common logarithm of the ratio of the sound pressure to the reference sound pressure, multiplied by 20, with the unit dB (decibels). The mathematical expression for the sound pressure level is presented in Equation (1):

where

represents the sound pressure (Pa);

P0 = 2 × 10

−5 (Pa) is the reference sound pressure, which is the threshold of human hearing—the faintest sound one can detect.

Noise propagation originates from the vibration of the sound source, representing the transfer of sound energy. The acoustic power at a point is quantified by sound intensity

I (unit: W/m

2), which decreases with distance from the source. The relationship between sound intensity

I and sound pressure

P in the propagation direction is given by Equation (2):

where

represents the air density, and

denotes the speed of sound in air.

The total acoustic energy emitted by a sound source per unit of time is defined as its sound power, measured in watts (W). Sound power, a key characteristic of a sound source, equals the integral of sound intensities over a closed surface enclosing the source, as defined in Equation (3):

where the integral represents the summation over the closed surface

S, the normal component of sound intensity over the area element ds. To more accurately establish the sound field model, the sound sources were classified into point, line, and surface sources based on their geometric shapes.

2.3.2. Acoustic Source Classification and Modeling

In a free sound field, where sound waves propagate without reflection, a point source emits spherical sound waves uniformly in all directions. The sound power of this point source can be expressed as Equation (4):

where

is the sound power, measured in watts (W);

IP is the sound intensity at a distance

from the point source, measured in watts per square meter (W/m

2); and

rP is the distance from the point source, measured in meters.

The sound intensity at a certain point

in space can be expressed as Equation (5):

The coefficient terms in Equation (5) are combined into sound intensity conversion coefficients

, as shown in Equation (6):

Therefore, for a point sound source with sound power of

, sound waves propagate, and the sound intensity generated by the sound waves at a certain measuring point in space is expressed by Equation (7):

A line sound source with limited length can be regarded as a collection of a finite number of discrete point sound sources. The sound intensity produced by the line sound source at measurement point A in space is shown in

Figure 4b, and the sound intensity IL of the line sound source is represented as Equation (8):

where

is the total radiated power of the line sound source;

is the length of the linear sound source;

is the distance between point A and the linear sound source;

is the projection point on the online sound source A; and

is the conversion coefficient of sound intensity.

The sound intensity conversion coefficient for the line sound source is defined in Equation (9):

That is, for a linear sound source with acoustic power

, sound waves propagate, and the sound intensity generated by the sound waves at a certain measurement point in space is indicated by Equation (10):

The sound intensity at a spatial measurement point A, generated by the surface sound source, is illustrated in

Figure 4c. To derive the governing equation for a finite-area surface source, the following key assumptions are made:

The sound power is uniformly distributed over the defined surface area. This implies a constant sound power density (in W/m2), which is a valid approximation for the well-mixed, highly turbulent conditions in the stilling basin under steady discharge.

Consider a rectangular surface source with dimensions

and

and total sound power

. The sound power per unit area is

. The sound intensity at a measurement point A is the integral of the contributions from all infinitesimal point sources

over the surface, using the point source model from Equation (5):

Substituting

yields Equation (12):

where

is the total radiated power of the surface sound source; a and b are the plane dimensions of the surface sound source;

is the distance between measuring point A and the surface sound source. (

,

) is the projection point of measuring point A on the surface sound source;

is the conversion coefficient of sound intensity.

The sound intensity conversion coefficient

is calculated using Equation (13):

Then, for a surface sound source with sound power

, sound waves propagate, and the sound intensity at a certain measuring point in space is indicated by Equation (14):

2.3.3. Overall Sound Field Model

Through experimental observation and analysis, spillway sound sources were classified into point sources, line sources, and surface sources:

Point sources: The flood discharge noise caused by localized turbulence at the outlets of 12 surface spillway flows and 10 bottom spillway flows as they impact the stilling basin can be approximated as point sources because the entry points are small relative to the overall noise field. A total of 22 point sources are identified for these flows entering the basin, as shown in

Figure 5.

Line sources: The flood discharge noise generated by turbulence, aeration, and rolling motion along the open channel chutes of 12 surface spillway flows and 10 bottom spillway flows can be approximated as line sources. In total, 22 line sources are identified within the open-channel chute for these flows.

Surface sources: The noise resulting from the interaction of discharge flow with the stilling basin sidewalls as it flows and diffuses is considered a surface source. During spillway operations, there are two surface sources for each of the left and right zones of the stilling basin.

The combined noise at each measurement point, contributed by point, line, and surface sources, is governed by the principle of linear superposition. Thus, the total sound intensity at a measurement point is the sum of contributions from these individual source types, as shown in Equation (15). This approach is physically justified by the principle of incoherent energy summation for broadband aerodynamic and hydrodynamic noise sources [

32]. Specifically, for sound pressure levels typical of flood discharge noise and within a linear acoustic regime, the total acoustic energy is the sum of the individual source energies. This holds true when the sound sources are incoherent, meaning their phases are random and uncorrelated. The turbulent flow phenomena responsible for noise generation in spillways (e.g., jet turbulence, vortex shedding, and bubble oscillations) are inherently random and broadband. Consequently, the sound fields generated by these mechanisms at different locations are statistically independent. The cross terms in the pressure-squared thus average to zero over the measurement time, leaving a simple arithmetic sum of the mean-square pressures from each source, which is equivalent to a sum of intensities.

Since the noise intensity at each measurement point can be considered as the superposition of the intensities from point sources, line sources, and surface sources, the sum of the intensities at a specific location in space after being influenced by various types of sources can be derived by expanding Equation (15), resulting in the flood discharge sound field model given by Equation (16):

Equation (16) presents the flood discharge sound field model, where and are the sound power of single surface spillway and bottom spillway water flowing into the water point sound source under a given unit flow rate, respectively; and are the sound intensity conversion parameters of surface spillway and bottom spillway water flowing into the water point sound source, respectively; and refer to the sound power of a single surface spillway and a bottom spillway open channel under the unit flow rate, respectively; and are the sound intensity conversion parameters of the surface spillway and the bottom spillway open channel drain line, respectively; and are the sound power of the surface sources generated by the surface spillway and the bottom spillway in the stilling basin, respectively; and and are the sound intensity conversion parameters for the left and right zone surface sources, respectively.

2.3.4. Model Parameter Calibration

The sound intensity conversion parameter α is independent of the sound power of the sources and is solely determined by the relative position between the measurement points and the acoustic sources. The sound intensity conversion parameter

α of different types of sound sources at each measuring point is calculated by integrating. The calculated sound intensity conversion parameters

,

, and

for the point, line, and surface sources, respectively, at the seven measurement points are summarized in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

To determine the sound power

of various types of sound sources per unit flow, eight sets of model tests were conducted. The conditions included various scheduling methods, such as fully open bottom spillway gates, partially open surface spillway gates, and combined partial opening of bottom and surface spillway gates. The regression algorithm was then used to disentangle the individual acoustic sources (point, line, and area) from the holistic sound field model and to quantify their respective sound power

values. The sound power of bottom and surface spillway point sound sources and line sound sources, as well as the surface sound sources of the stilling basin, are thus determined using a unit flow rate, as listed in

Table 5.

Substituting the sound power values from

Table 5 into Equation (16), we can obtain the specific flood discharge sound field model, as shown in Equation (17):

In order to more intuitively reflect the noise intensity of the engineering prototype, the calculated sound intensity I was converted to the sound pressure level

LA (unit: dB) using Equation (18):

2.3.5. Computational Algorithm for Sound Field Prediction

To facilitate the practical application and replication of the flood discharge sound field model, the computational procedure for predicting the sound pressure level at any point of interest is summarized in the following algorithm.

Step 1—Input Operational Scenario: Specify the spillway gate operations (gate openings for each surface and bottom spillway) to define the flow rates and .

Step 2—Compute Sound Intensity Conversion Coefficients (): Calculate the geometric coefficients

,

, and

for all source–measurement point pairs using Equations (6), (9) and (13). These are purely a function of the fixed project geometry and can be precomputed (as shown in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4).

Step 3—Calculate Sound Intensity Contributions: For each measurement point, compute the total sound intensity using the calibrated sound field model (Equation (17)), which sums the contributions from all point, line, and surface sources.

Step 4—Convert Sound Intensity to the Sound Pressure Level: Convert the total sound intensity at each measurement point to the A-weighted sound pressure level using Equation (18) for direct comparison with prototype observations and noise standards.

4. Discussion

4.1. Operational Response of Flood Discharge Noise

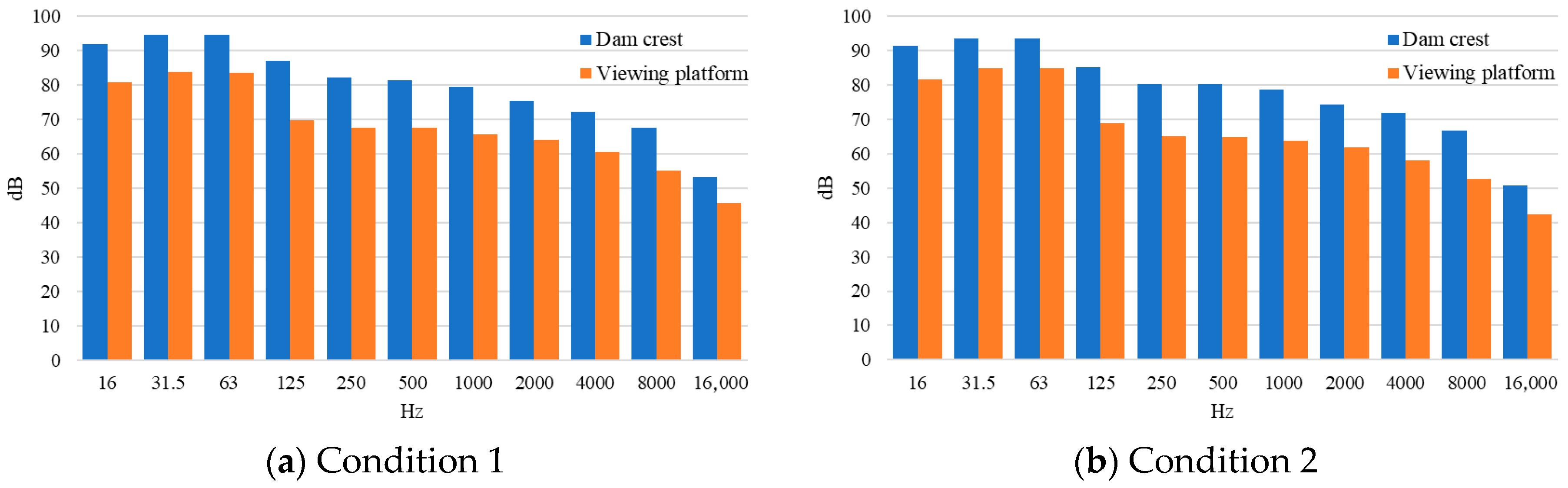

Having established the validity of the sound field model, we next employ it to investigate the noise contributions from different acoustic sources under various operational scenarios. This analysis aims to inform noise-aware operational strategies. We defined four representative operating conditions (

Table 7) to systematically isolate the effects of using surface spillways alone, bottom spillways alone, and their combinations at different total discharge rates.

For these four conditions, the relative contribution of each source type (point, line, and surface) to the total noise level was calculated at two critical locations: the dam crest and the downstream viewing platform. The results are visualized in the pie charts shown in

Figure 8.

As shown in

Figure 8, under all conditions, surface sound sources from the stilling basin are the primary contributors to flood discharge noise. This highlights that rolling water surface caused by water jets from the bottom and surface spillways entering the stilling basin is the main noise source.

Condition 3 (Bottom Spillways Only):

When only the bottom gates are used, noise from the bottom spillway entry point sources accounts for 21–26%, exceeding that from bottom spillway channel line sources (<10%), making it the secondary noise source. The swirling turbulence at the entry points generates noise, while the turbulence in the open spillway channels remains mild, resulting in lower noise levels.

Condition 4 (Surface Spillways Only):

At the dam crest, proximity to longer surface spillway channels results in noise from channel line sources (36%) surpassing that from entry point sources (20%), making it the secondary noise source. At the viewing platform, equidistant from the surface spillway components, noise from entry point sources (19%) also ranks as the secondary source.

Conditions 5 and 6 (Surface Spillways and Bottom Spillways Combined):

At the dam crest, surface and bottom spillway channel line and entry point sources account for nearly half of the noise observed. At the viewing platform, the stilling basin surface sources dominate, producing significantly more noise than the combined contributions from the spillway channels and entry points.

The results indicate that, under the same water head and discharged volume conditions, the discharge noise intensity generated by surface spillways is significantly greater than that produced by bottom spillways. In the combined discharge scenario of bottom and surface spillways, the proportion of flow from the bottom spillways (83%) is much greater than that from the surface spillways (27%). However, the spillway noise generated by both types of spillways is approximately equivalent, further demonstrating that the noise from the surface outlet is substantially greater than that from the middle outlet.

This study provides novel quantitative insights into spillway noise. For a submerged hydraulic jump stilling basin, it is demonstrated that the rolling water surface is the dominant acoustic source, thereby refining the multi-source theory [

27]. Crucially, it is shown that surface spillways generate acoustic power that is three times that of bottom outlets, offering a definitive solution to the practical challenge of predicting dispatch noise. The mechanistic explanation for this acoustic disparity is established by bridging prior flow studies [

33,

34] with the obtained data: intense, noise-efficient bubble dynamics are produced by surface jets [

16], whereas energy is dissipated by submerged jets behind the effective barrier of the water–air interface.

4.2. Mechanism of Noise Generation

The significantly lower noise levels generated by the bottom spillways, as quantified in

Section 4.1, are fundamentally attributed to their distinct flow regimes and energy dissipation mechanisms. These differences are a direct consequence of the specific structural design employed at the Xiangjiaba Hydropower Station, which features a high–low dual-layer outlet design. As illustrated in

Figure 9, this configuration, with the surface spillway sill approximately 8 m higher than the bottom outlets, dictates profoundly different flow paths and acoustic source characteristics.

Zhang [

33] investigated the flow characteristics of a similar high–low dual-layer outlet energy dissipation structure using large-scale model tests, as illustrated in

Figure 10.

For surface spillways (high-level outlets), the flow constitutes a surface jet that impinges directly onto the rolling water surface of the stilling basin. This creates a symmetric, stable surface-vortex flow pattern (

Figure 10a), characterized by intense, large-scale turbulence at the air–water interface. This flow regime is highly conductive to noise generation through two primary mechanisms: (1) direct impulsive impact and water surface fragmentation, which produces broad-spectrum noise, and (2) intense air entrainment, where the formation and collapse of numerous bubbles act as potent mid-to-high-frequency sound sources, consistent with findings on bubble noise [

16]. The rolling water surfaces act as efficient radiators, directly exciting the overlying air and leading to high acoustic emissions.

In contrast, the bottom spillways (low-level outlets) discharge as submerged jets deep into the stilling basin (

Figure 10b). Numerical investigations by Hu et al. [

34] on analogous multi-jet stilling basins, using vortex identification criteria, confirm that while submerged jets generate vortices, the primary energy dissipation occurs via shearing against boundaries and vortex dynamics confined underwater. The flow pattern is characterized by an inward, counterclockwise swirling motion near the basin bottom (

Figure 10b). This containment has critical acoustic implications: the energy is primarily converted into water vibrations and internal energy, with intense vortices dissipating below the surface. Consequently, the direct excitation of the free surface is drastically reduced. Furthermore, the significantly lower air entrainment minimizes bubble-related noise. Finally, the water–air interface itself acts as a significant impedance barrier, strongly attenuating the transmission of any remaining underwater acoustic energy to the air, particularly at higher frequencies.

The noise contrast between surface and bottom spillways is explained by integrating acoustic data with hydrodynamic studies. Surface spillways exhibit a direct jet impinging on the stilling basin (

Figure 7a), consistent with Zhang’s surface vortex [

33]. This flow promotes intense air entrainment and bubble dynamics—a key noise mechanism [

16]. In contrast, bottom outlets form submerged jets (

Figure 7b) that generate energy-dissipating vortices underwater [

33,

34]. Acoustic measurements confirm that the water–air interface acts as an effective barrier, reducing sound transmission. Thus, this study establishes the missing empirical link between flow structures and acoustic effects, explaining why submerged dissipation is quieter.

4.3. Implications for Mitigation and Dispatch Strategies

The quantitative findings of this study provide a scientific basis for formulating noise-informed dispatch strategies at the Xiangjiaba Hydropower Station and similar projects. The key to mitigation lies in the significant acoustic advantage of bottom outlets over surface spillways. Based on the model’s results, the following operational recommendations are proposed to minimize community noise impact while meeting discharge requirements:

1. Preferential use of bottom outlets: Under identical discharge head and flow rate conditions, bottom spillways should be prioritized over surface spillways. Our results demonstrate that this simple operational shift can reduce the radiated sound power by approximately a factor of three for the same discharged volume.

2. Optimized gate operation in combined use: When the combined use of bottom and surface spillways is necessary for large flood events, the flow distribution should be optimized. Maximizing the flow proportion through the bottom outlets, even if not exclusively used, can lead to a substantial net reduction in the overall sound field intensity downstream.

3. Strategic selection of surface spillways: If surface spillways must be operated, the specific gates activated can be selected based on sound field model predictions to minimize noise impact on the most sensitive downstream receptors (e.g., the residential area on the right bank). The model enables planners to simulate different gate-opening scenarios and identify the acoustically optimal configuration.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to develop a comprehensive predictive model for the sound field generated by high dam flood discharge, a significant environmental concern for downstream communities. To achieve this, we proposed a novel three-dimensional framework for classifying acoustic sources into point, line, and surface types. By integrating prototype observations from the Xiangjiaba Hydropower Station with hydraulic model tests, a multi-source sound field model was developed and validated.

The primary findings and contributions of this work are as follows. First, a multi-source sound field model was established, achieving high predictive accuracy with errors below 1.5 dB when validated against prototype data. Second, the model quantified that the rolling water surface of the stilling basin (surface source) is the dominant contributor to noise, a finding that refines the multi-source generation mechanisms suggested in prior research [

27] by providing a quantitative hierarchy for an underflow energy dissipation hydraulic hub. Third, a key quantitative finding is that surface spillways generate approximately 3 times the acoustic power as bottom spillways under identical discharge conditions. This finding offers a concrete, actionable metric that significantly extends the general principle from earlier studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] that flow modification can mitigate noise.

The practical implications of these results are direct and significant for dam operation and design. The model provides a critical tool for formulating noise-informed dispatch strategies, enabling operators to prioritize bottom outlets to mitigate community noise impact during flood events. Furthermore, the quantified acoustic advantage of bottom outlets offers valuable insight for the design of new hydropower projects, suggesting that incorporating low-level outlets is beneficial for environmental noise control.

A primary limitation of this study is that the model and its conclusions are derived specifically for energy dissipation structures employing a submerged hydraulic jump in a stilling basin. The findings may not be directly applicable to other forms of energy dissipation, such as ski-jump trajectory flow, where the noise generation mechanisms and propagation paths could differ substantially.

Future research will focus on extending the applicability of this modeling approach. Immediate directions include adapting the multi-source framework to ski-jump spillways and other energy dissipation models. We also plan to incorporate meteorological effects on sound propagation and seek additional prototype validation opportunities when they arise, with the ultimate goal of developing a generalized predictive tool for a broader range of hydraulic structures.