Abstract

To investigate the impact of subsurface karst cavities on the stability of pipe jacking construction, this study utilizes the Yunnan Central Water Diversion Project as a real-world case. Employing ABAQUS finite element software to establish a numerical model, it systematically analyzes construction stability under the specific condition of “karst cavities present ahead of the excavation direction” in karst formations. The research focuses on examining the effects of four key scenarios on the displacement and stress response of surrounding rock and pipe segments. These conditions specifically include the following: tunnel burial depth (10 m, 15 m, 20 m, 25 m), cavity diameter beneath the tunnel (1–4 m), cavity filling status, and distance between the cavity and the tunnel (1–4 m). The study reveals that in composite stratum tunnel construction, when cavities exist in the strata ahead, multi-area displacements increase progressively with cavity size. Displacement changes accelerate and magnify when the cutting face of the jacking machine approaches within approximately 2.5 m of the cavity. However, no significant difference is observed between soft plastic clay reinforcement and slurry reinforcement effects. When composite stratum tunnels traverse beneath karst caves, the maximum upward bulge at tunnel bases occurs at 1-meter diameter caves, reaching approximately 2.5 mm. When the diameter of the cave increases to 4 m, the arching settles to a maximum. As tunnel burial depth increases, the arch base rises while the crown sinks, with settlement magnitude exceeding bulge amount. The displacement and stress fields from the initial excavation phase become disturbed, intensify, and then stabilize. When the jacking machine reaches directly above the cavern, stress at the crown base increases while stress at the crown top decreases. The pipe bottom exhibits uplift, and the pipe top shows reduced settlement directly above the cavern. Cavern filling has a minor effect on pipe-segment displacement, with segments deforming into an approximate elliptical shape. At the completion stage of excavation, the maximum Mises stress occurs at the top of the launch-end pipe segment. While cavern-related factors have a limited influence on the pipe-segment Mises stress, this stress gradually increases as excavation progresses.

1. Introduction

Driven by socioeconomic development, the number of tunnel projects in China has surged significantly, with construction increasingly focused on geologically complex regions. The mountainous terrain and widespread karst formations in central and western China make tunnel engineering critical for highway and railway development. Sterling et al. [1] reviewed the development of pipe jacking and microtunneling, focusing their research on jacking load assessment. They highlighted progress in studying the effects of friction loads and noted that effective lubrication can reduce friction resistance during pipe jacking. Sha et al. [2] investigated the primary factors affecting shield tunnel stability, demonstrating that karst geology has been shown to significantly increase the risks associated with shield tunnel construction. When tunnels traverse karst zones, engineering hazards such as sudden water surges, low bearing capacity of karst foundations, seepage, surface subsidence, and jacking machine descent may occur. These hazards pose significant threats to tunnel safety. Furthermore, during pipe jacking construction in karst formations, common engineering issues include cutterhead instability and collapse, abnormal attitude deviation, soil collapse at the excavation face, and excessive ground settlement. The presence of karst cavities ahead of the tunnel axis can alter the mechanical force transmission patterns during pipe jacking. Research on these influence mechanisms holds significant theoretical guidance and practical engineering value. Numerous scholars have conducted multifaceted studies on the impacts of tunnel construction in karst cavities.

Numerous scholars have conducted research based on actual engineering projects: Zhao et al. [3,4,5,6], using the Chaodongyan Tunnel as a case study, investigated the effects of karst cavities of varying sizes, spacings, and orientations on the stress–strain behavior of the surrounding rock in pipe jacking tunnels. They employed experimental systems and finite element software for modeling and analysis, with consistent results between model tests and numerical simulations. Zheng et al. [7] analyzed the challenges posed by the Yujingshan Tunnel on the Chengdu–Guiyang High-Speed Railway in Yunnan Province. They further examined in situ monitoring results of layer-like subsidence beneath giant karst caverns, tunnel crown settlement, and horizontal convergence. Cheng et al. [8] proposed a method for predicting the grouting volume required to treat karst cavities in shield tunnels based on the karst cavities along the tunnel section of Guangzhou Metro Line 9. Zhang et al. [9] presented measurements and predictions of surface responses induced by tunnels in karst formations in Guangzhou. They proposed a ground subsidence prediction method termed the Extended Deep Learning Approach. This method achieves precise prediction of tunnel-induced ground subsidence by extending the Conv1d model. Tang et al. [10] quantitatively analyzed the construction response of pipe jacking tunnels with karst cavities at different orientations to identify the most unfavorable positions. Li et al. [11] presented a case study of the Hechi-Baise Expressway Tunnel, adhering to the optimized management plan for karst cavities in the Hechi-Baise Tunnel. They propose a comprehensive pre-treatment method tailored to this tunnel, with the optimized treatment plan primarily encompassing calculating the safe thickness of the tunnel face, reinforcing the initial support, increasing the thickness of the secondary lining, and incorporating additional allowance for deformation and grouting. Based on the actual collapse pattern of shallow tunnels, Yang and Huang [12] established a curved failure mechanism for such tunnels. Li et al. [13] independently developed a three-dimensional fluid–solid coupling model test analysis system to investigate the effects of karst cavity orientation on surrounding rock stability and variations in surrounding rock stress and seepage pressure. Cheng et al. [14] addressed the issues of insufficient geological understanding and high disaster risks along tunnel routes due to limited boreholes. They proposed a method using five factors, including cutter torque, to determine foundation composition. The results align with soil testing data, aiding in refining tunnel parameters and reducing geological hazards. Su et al. [15], based on the Liangwangshan Tunnel, presented a case of tunnel failure by karst fissure, and the failure mechanism and treatment were analyzed. Liu et al. [16] employed a series of specialized methods—including engineering geological surveys, SATEM, and SLAM-based LiDAR—at various stages of tunnel construction using the No. 1 Tunnel Project in Linlan Village, Guangxi, as a case study. Through an in-depth analysis of underground karst cavities, they provided a high-level technical foundation to ensure tunnel construction safety. Coli and Castellucci [17] studied a special case: a tunnel designed with consideration for karst system protection and environmental factors such as sulfates, incorporating corresponding measures. However, due to incomplete safeguards in the relevant regulations for sulfate-resistant concrete at the time, combined with external pressure and cavitation effects, the lining experienced unexpected degradation, resulting in unforeseen impacts on the karst system and a series of subsequent problems. This negative experience provides valuable lessons for the planning and design of future tunnel projects in karst regions.

Studies addressing the impact of cavities in various orientations on rock mass stability include the following: Peng et al. [18] investigated the use of grouting waste material for backfilling giant karst cavities as a tunnel crossing strategy. They established numerical models of cross-sectional characteristics for different karst cavities and tunnel distributions, separately studying the deformation of surrounding rock with and without grouting, as well as the mechanical response of tunnel linings. Tan et al. [19] used FLAC3D, a commercial software package, to investigate the effect of lateral cavities in karst areas on jacking construction for expressways, comparing numerical analysis with field measurements. Wang et al. [20] used a field-constructed tunnel as a case study, employing model tests and theoretical analysis to examine the effects of karst cavity size and other conditions on surrounding rock deformation and initial support loading. Liu et al. [21] based their analysis on a subway shield tunnel project, modeling and analyzing the impact of karst cavities beneath shield tunnels at different burial depths on surrounding rock stability using geophysical survey results. To predict the collapse of the rock mass at the tunnel excavation site above a karst cave, Fu et al. [22] obtained an analytical formula for the collapse surface via variational calculations within the framework of the upper bound theorem. This analytical solution was subsequently used to examine how rock parameters affect the collapse surface of the rock mass with a karst cave beneath the tunnel. Zhao et al. [23] investigated the stability of a rock pillar located above a concealed karst cave ahead of a roadway. By leveraging the fluid–solid coupling method and the strength reduction method, they established a fluid–solid coupling model. This model was used to determine the safety thickness of the rock pillar, which aims to avoid water inrush from the concealed karst cave. Wang [24], Li [25], and others used finite element software to investigate the influence patterns of karst cavities at different orientations on the stress–strain behavior of tunnel linings. Hou [26] and others conducted comprehensive assessments during the construction of the Shenzhen–Huizhou Double-Track Shield Tunnel, delving into the damage development mechanisms and extent of damage in karst-bearing strata. Bhasin et al. [27] employed the 3DEC discrete element method to simulate the formation process of large cavities within underground cavern complexes of hydropower stations in the Himalayan region. The study analyzed the effects of structural features such as joints and shear zones on stress redistribution and deformation within the surrounding rock mass, proposing corresponding support and backfill schemes. Guo et al. [28] examined the influence of karst cavity filling conditions on tunnel rock mass based on survey data. Huang et al. [29] derived an analytical expression for the collapse surface between karst cavities and tunnels based on the upper bound theorem of limit analysis. Chen et al. [30] analyzed the evolution of water inflow, rock mass displacement, and lining mechanical performance during tunnel construction and operation through field testing and numerical modeling. Dong et al. [31] used finite element software to establish a three-dimensional numerical model of the shield machine, investigating the impact of karst-cavity-related parameters on maximum ground settlement under treated and untreated conditions. Yang et al. [32] employed Abaqus software modeling to analyze deformation characteristics of blasted excavation rock mass at varying relative angles between cavities and the tunnel. Eric et al. [33] presented a dimensionless stability chart to evaluate the stability of the residual soil near existing cavities based on numerical analyses. Gao et al. [34] established a tunnel portal calculation model with cavern-induced lateral pressure at different locations based on the Leye–Wangmo Expressway Tunnel, analyzing rock mass deformation patterns under cavern influence. For assessing the stability of ground with underground cavities, Augarde et al. [35] computed the rigorous bounds of true collapse loads through the use of the finite-element limit analysis technique. Li et al. [36] analyzed real-time data to study the stress patterns and underlying mechanisms on tunnel sidewalls during shield advancement, thereby elucidating stress formation mechanisms in large-diameter shield tunnels traversing karst-rich zones. Mu [37,38] and colleagues established finite-element numerical models based on field construction monitoring data and ground-penetrating radar results, focusing on how factors such as karst cavity size, clearance distance from the lining structure, and changes in position and shape affect the stress and deformation of tunnel lining structures.

This study leverages the actual operating conditions of the Kunming Main Urban Area Southeast District Water Transmission and Distribution Integration Project—a supporting initiative of the Central Yunnan Water Diversion Project—to focus on the specific scenario of cavities beneath pipe jacking operations. The model parameters and construction process in this study are derived from actual engineering practice. Using finite element analysis, it expands the investigation to examine the varying effects of different cavity dimensions, burial depths, distances, and soil parameters, revealing the correlation mechanism between these operational variables and the stability of pipe jacking construction. The expanded analysis yields targeted findings, providing foundational data, analytical methods, and a research framework for broader, comprehensive studies on karst cavern–pipe jacking interactions across diverse regions and project types. Consequently, this study represents a preliminary exploratory effort in the field, offering design reference guidelines for mitigating risks in pipe jacking operations within karst terrain.

This study provides a foundational dataset, standardized analytical methods (finite-element modeling workflow), and a universal research framework for subsequent investigations into the interaction between sinkholes and pipe jacking in different regions (e.g., the karst areas of Southwest China, the red-bed karst areas of South China) and for various engineering types (e.g., utility tunnel pipe jacking, municipal sewage pipe jacking).

However, it should be noted that the study still has certain limitations. Although the finite-element model parameters in this research are based on field drilling data, since the project is still under construction, long-term (over 1 year) monitoring data after pipe jacking have not been obtained. Therefore, the conclusions cannot yet verify the impact of soil creep during long-term service on pipeline stability. The model did not account for dynamic groundwater changes during construction (such as fluctuations in the water table caused by rainfall), simulating only static water level conditions. This limitation may slightly reduce its applicability as a reference for similar projects in regions with high rainfall.

2. Project Overview

The Central Yunnan Water Diversion Supporting Project—Kunming Main Urban Area Southeast District Integrated Water Transmission and Distribution Project—serves as a pivotal “hub” for realizing the comprehensive benefits of the Central Yunnan Water Diversion Project. This project primarily focuses on infrastructure development in Kunming’s southeast district, with two core tasks: first, expanding and renovating Kunming’s Eighth Water Plant; second, constructing the supporting water supply pipeline network system.

This study focuses on the critical pipeline segment of the project: the raw water transmission mainline stretching from the newly constructed Eighth Water Plant to the Shiniu Mountain Elevated Reservoir. This mainline spans 15.43 km and utilizes steel pipes with a diameter of 1800 mm (DN1800).

In the study of pipe-jacking construction techniques, this paper selected the section between Well 16 and Well 17 as the primary research focus, with a pipe jacking operation length of 50 m. Based on geological survey results, the geological conditions in this pipe jacking area are relatively complex, characterized by a composite geological structure of “hard rock below and soft soil above.” Moreover, borehole investigations revealed the presence of karst cavities, primarily developed with diameters below 4 m and predominantly distributed within a burial depth range of 10 to 25 m. During tunnel construction, the presence of karst formations may easily cause ground subsidence, posing a threat to the safety of municipal roads and existing structures.

Engineering geological data for this section indicates the presence of fill soil, red clay, strongly weathered limestone, and moderately weathered limestone. The fill soil primarily consists of brownish–gray, gray, and dark gray materials, ranging from moderately dense to locally loose and slightly moist, with concrete and asphalt pavement at the top and graded aggregate below. Backfilled approximately four years ago, it is classified as subconsolidated soil. The physical properties and structural parameters of the construction strata are shown in Table 1. The exposed layer ranges from 0.6 m to 9.5 m in thickness, with the top elevation between 1966.35 m and 2045.32 m. Red clay appears reddish–brown or brownish–red, ranging from hard plastic to locally plastic and slightly moist, containing angular gravel. The exposed layer thickness is 0.5 m to 23.1 m, with the top elevation ranging from 1962.26 m to 2037.63 m. Heavily weathered limestone, gray to grayish–white with reddish streaks, exhibiting pronounced differential weathering. The rock is fragmented with well-developed dissolution joints; the core appears blocky. The rock mass quality is grade V. Exposed layer thickness: 0.6 m to 45.7 m. Top elevation: 1954.77 m to 2038.90 m. There is moderately weathered limestone, gray to grayish–white in color, with a cryptocrystalline dense texture and medium-thick layered structure. The rock cores are predominantly columnar, featuring well-developed calcite veins and localized dissolution. Rock hardness ranges from soft to hard, with integrity varying from moderately fragmented to moderately intact. Basic quality grade: Grade III. Exposed layer thickness: 0.4–32.1 m, with the top elevation ranging from 1945.54 m to 2043.95 m.

Table 1.

Physical properties and structural parameters of construction strata.

The rock-breaking mud–water–air pressure-balanced composite pipe-jacking machine employed in this project has a length of 5000 mm and an excavation diameter of 1880 mm.

3. Numerical Simulation Studies

3.1. Model Development and Material Parameters

This study, based on a specific pipe jacking project, constructs a three-dimensional elastoplastic numerical analysis model to investigate the impact characteristics of cavities at the tunnel face on surrounding rock stability and surface deformation under various operating parameters. The aim is to provide scientific design references for risk prevention and control of pipe-jacking construction within karst geological conditions.

Using the ABAQUS numerical simulation platform, a three-dimensional model with dimensions of 50 m (length) × 35 m (width) × 25 m (height) was constructed. The pipe jacking machine was set with a diameter of 1880 mm and a length of 5000 mm, with an overburden thickness of 5.54 m above it. The outer diameter of the pipe section is 1820 mm, with an inner diameter of 1760 mm. The mud sleeve thickness is determined to be 30 mm based on the radial difference between the pipe section and the jacking machine, with the specific arrangement shown in the figure. The simulated strata exhibit varying physical properties from top to bottom, and the specific parameter values of the jacking structure are detailed in the table.

During simulation, soil was modeled using the Mohr–Coulomb (MC) constitutive model, while the pipe section and cavern material employed an ideal elastic constitutive model. In the finite-element numerical solution process, the type of mesh element plays a decisive role in the convergence and accuracy of computational results. ABAQUS software provides an extensive element library. In geotechnical modeling scenarios, solid elements (e.g., C3D8 series), shell elements (e.g., S4R), and beam elements (e.g., B31) are three commonly used categories, typically employed to simulate soil media, support structures, and load-bearing components, respectively. Among these, three-dimensional solid elements see the widest application in engineering. Core types include C3D8, C3D8R, C3D20, and C3D20R. These categories achieve a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy through different integration rules and node distributions. When contact deformation is present, reduced-integration elements (e.g., C3D8R) can be selected to enhance computational convergence. The characteristics of each solid element type are detailed in Table 2. In this simulation, the pipe jacking, equivalent layers, and soil mass were all discretized using the C3D8R solid element. The precision of C3D8R is demonstrated through its adaptability to pipe jacking, isopleth layers, and soil bodies: When simulating pipe jacking, its linear reduction integration resists shear self-locking, accommodates large deformations in pipe jacking, and accurately transmits pipe–soil contact forces, balancing both accuracy and efficiency. When simulating isostatic layers, locally refined meshes ensure computational accuracy for simplified geometries, transmit interlayer interface forces, and prevent spurious deformation by monitoring energy ratios. For soil simulation, it supports Mohr–Coulomb and other constitutive models to reproduce plastic zones, resists mesh distortion, and captures stress concentrations through critical region refinement—fully meeting the simulation demands of pipe jacking projects.

Table 2.

Comparison of entity unit characteristics.

When defining material uncertainty boundaries, Phoon et al. [39] systematically elaborated a quantitative framework for geotechnical parameter uncertainty, including Bayesian updating, random field modeling, and reliability design methodologies. The book provides statistical tables of the coefficient of variation for parameters of materials like clean fill and weathered rock, which can be directly used to determine the fluctuation range of elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio. Yang et al. [40] revealed the decay pattern of elastic modulus in clean fill under wet–dry cycles through triaxial tests and numerical simulations, suggesting that when the compaction degree fluctuates by ±5%, the uncertainty boundary of E is ±20%. Gao et al. [41] statistically analyzed 275 red clay samples, finding that elastic modulus E has a 25% coefficient of variation. Poisson’s ratio ν correlates significantly with crack development degree, and they recommend μ ± 2σ for defining parameter boundaries. Atkinson and Li [42] pioneered the degradation mechanism of chemical dissolution on limestone elastic modulus. Experiments indicate that acidic solutions can reduce E by 30–50% and increase Poisson’s ratio ν by 10–20%. Saber et al. [43] analyzed elastic modulus degradation in concrete pipe segments under corrosive environments, suggesting an 8–15% reduction in E and a 5–10% increase in Poisson’s ratio ν due to chloride ion permeation.

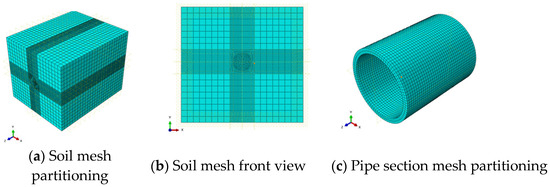

The mesh partitioning employs a sweeping neutral axis method, with uniform mesh sizes of 150 mm set for both the pipe sections and the slurry layer (equivalent layer). For the soil-layer meshing, a cross-shaped cut was applied to the soil at the tunnel’s central location. Soil regions farther from the tunnel were meshed more sparsely. Along the pipe-jacking tunnel path, the mesh size was set to 150 mm to match the contact with the slurry and pipe sections. As the mesh transitions toward the surrounding soil layers, the mesh size progressively grows to 3000 mm. The entire model comprises 71,670 elements and 116,765 nodes. The node count of 116,765 corresponding to 71,670 elements aligns with typical engineering model scales [44]. Further refinement to 100,000 elements could increase computation time by 3–5 times (e.g., 1172 min for 150,000 E2 elements [44]) while yielding a less-than-2% accuracy improvement. Reducing the number of cells to 50,000 may result in a maximum deviation of 8–12% in the calculated cave ceiling settlement values. Increasing to 100,000 cells narrows the deviation to 2–4%. Considering the project’s permissible error margin (±5%), the error range of 71,000 cells (3–6%) falls within the acceptable tolerance. Therefore, this configuration is selected as the optimal cost-performance solution. And Abaqus officially recommends limiting the number of elements in 3D models involving nonlinear contact analysis to under 100,000 to prevent solution divergence. The 71,000 elements used in this study, combined with the reduced integration element (C3D8R), comply with this recommendation while ensuring convergence and reducing computational resource consumption. For pipe–soil contact simulation, the surface-to-surface contact method within the contact pair approach was selected. For the pipe–soil contact region, the lower half of the pipe segment was assumed to contact the mud, while the upper half contacted the soil. The mesh division results for each component of the numerical analysis model are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mesh division status for various components.

The cave-filling material adopts an elastic structural constitutive model. The mechanical parameters of the cave-filling material are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties of karst-cave-filling materials.

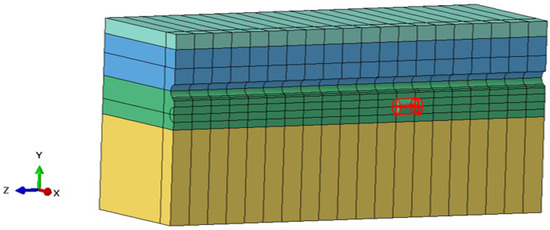

Based on the distribution and size of karst cavities identified in geological surveys, cavity sizes are defined as follows: no cavities, 1 m diameter, 2 m diameter, and 4 m diameter (approximately 0.5×, 1×, and 2× the pipe section diameter). Cavities are located 30 m from the launch portal. Three scenarios were simulated within the cavities: unfilled, filled with clay, and filled with slurry. To facilitate quantitative analysis, cavities were modeled as cylindrical structures positioned in the lower half of the tunnel. Figure 2 illustrates the location of cavities ahead of the jacking tunnel in composite ground within the finite element model.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional finite element model of a pipe jacking tunnel in a karst area.

3.2. Boundary Conditions

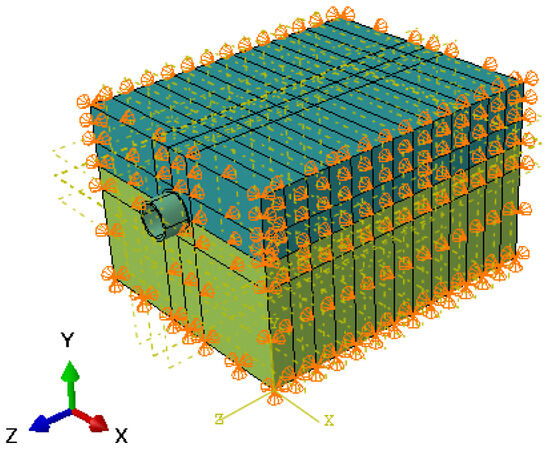

For the boundary conditions of the model, full-degree-of-freedom constraints are applied at the bottom, meaning displacements in the X, Y, and Z directions are fixed. Lateral boundaries (including both sides and front/rear) employ normal displacement constraints, under which the soil can only displace tangentially along the boundary. The ground surface is set as a free boundary condition with no constraints applied. Specific details are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Stratigraphic boundary conditions.

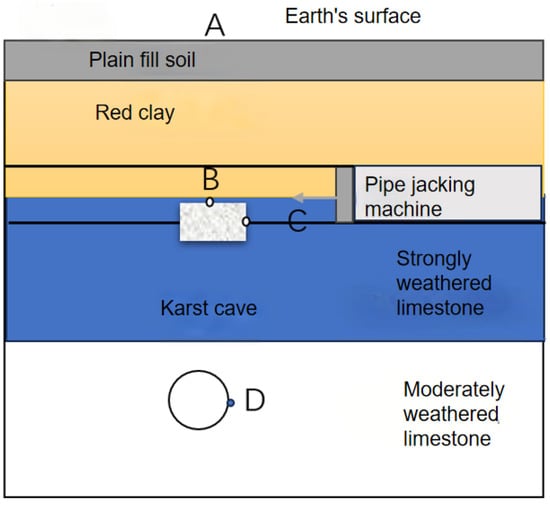

Monitoring point layout: The Figure 4 illustrates the displacement monitoring points for this study. In the analysis of the karst cavities ahead of the tunnel, the primary focus is on points A, B, C, and D, corresponding to the ground surface, the top of the cavity, the area ahead of the cavity, and the mid-cavity position, respectively.

Figure 4.

Monitoring point layout diagram.

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Surrounding Rock Displacement Response

4.1.1. Influence of Tunnel Burial Depth on Surrounding Rock Displacement

To investigate the effect of a 2-meter-diameter karst cavity located 1 m below the tunnel bottom on surrounding rock displacement in pipe jacking tunnels at different burial depths, tunnels with burial depths of 10 m, 15 m, 20 m, and 25 m were constructed.

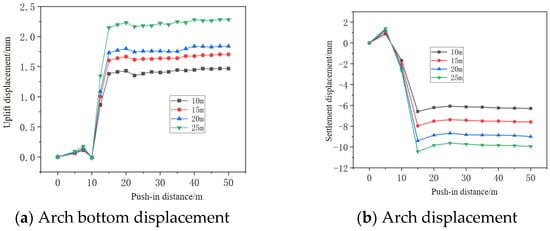

Figure 5 shows the variation curves of displacement at the arch bottom and arch top of the surrounding rock for pipe jacking tunnels at different burial depths as a function of jacking distance. The figure indicates that for jacking tunnels buried at 10 m, 15 m, 20 m, and 25 m depths, the greatest displacement changes—specifically uplift at the arch base and settlement at the arch crown—occur during initial jacking. Subsequent displacement rises are minimal, stabilizing over time. This behavior stems from the long-term evolution of the strata, where displacement and stress fields have reached equilibrium. Tunnel excavation disturbs the strata, disrupting the original equilibrium. This causes sudden and concentrated stress release in the surrounding rock, leading to a sharp increase in displacement. Simultaneously, as the tunnel burial depth increases, the initial stress in the surrounding rock grows. After excavation disturbance, the released stress becomes greater, resulting in larger displacements at both the arch crown and base.

Figure 5.

Displacement curves of surrounding rock for pipe jacking tunnels at different burial depths as a function of jacking distance.

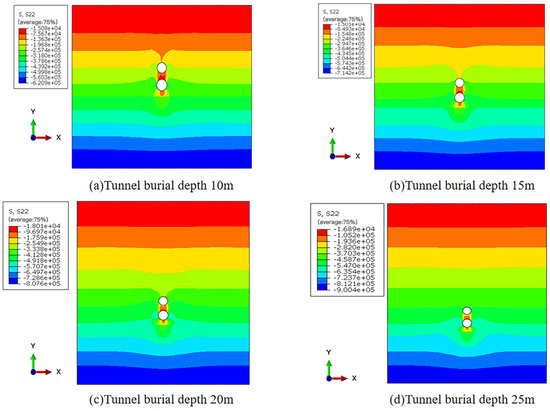

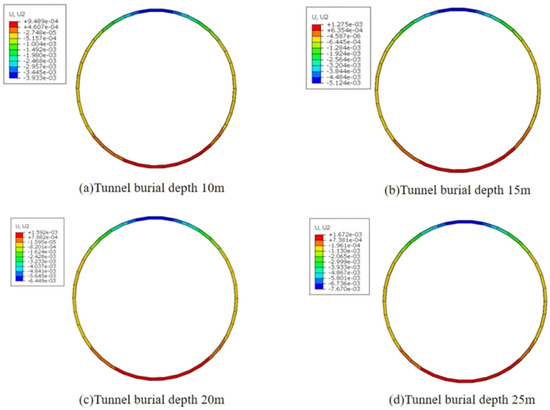

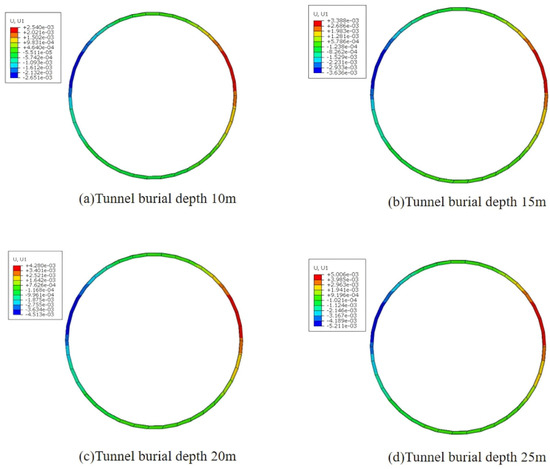

Figure 6 shows the vertical displacement contour maps around the tunnel rock mass and cavities after completing the pipe jacking excavation at burial depths of 10 m, 15 m, 20 m, and 25 m.

Figure 6.

Vertical displacement contour map of the tunnel surrounding rock and karst cavities after pipe jacking excavation.

As shown in Figure 6, with increasing burial depths of the pipe jacking tunnel, the displacement at the crown and base of the tunnel continues to increase due to excavation disturbance. Furthermore, settlement occurs at the crown of the tunnel, while uplift occurs at the base. Greater burial depth in pipe jacking tunnels boosts vertical and lateral earth pressures—key to displacement changes. Excavation upsets stress balance: the crown, losing support under stronger vertical pressure, settles more as the depth swells; the crown base, freed from overlying pressure, rebounds, and its uplift also rises with depth due to lateral pressure compression. Moreover, a deeper burial amplifies pre- vs. post-excavation stress differences. Thus, both crown and crown base displacements increase with burial depth.

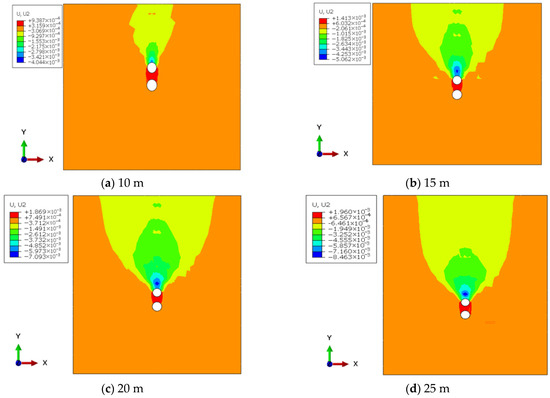

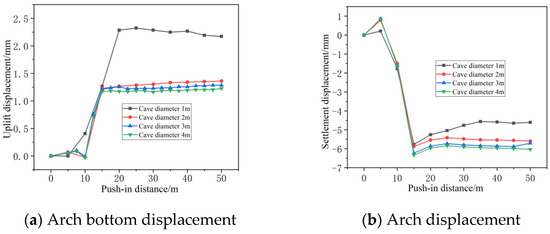

4.1.2. Effect of Karst Cavity Size on Tunnel-Surrounding Rock Displacement

When constructing the simulation model, the dimensions of the caverns were set to 1 m, 2 m, 3 m, and 4 m, respectively. These dimensions maintain specific proportional relationships with the tunnel diameter, corresponding to 0.55 times, 1.1 times, 1.65 times, and 2.2 times the tunnel diameter. Additionally, the caverns were positioned 1 m above the bottom of the pipe jacking tunnel.

From Figure 7 provided by the model, the displacement trends of monitoring points at the crown and base of the pipe jacking tunnel are clearly visible. Careful analysis yields the following conclusions: When the cavern diameter is 2 m, 3 m, or 4 m, the displacement values at the crown and base show minimal difference. As the diameter of the cavern increases, the upward bulging of the tunnel floor decreases, while the downward settlement of the crown increases. Specifically, when the cavern diameter is 1 m, the upward bulging of the tunnel floor reaches its maximum value of approximately 2.5 mm; when the cavern diameter expands to 4 m, the maximum downward settlement of the crown can reach 5.9 mm.

Figure 7.

Tunnel displacement variation curves for caves of different sizes.

This occurs because karst cavities change the support conditions and stress transfer of the tunnel’s surrounding soil. Smaller cavities increase arch-bottom rebound, while larger ones weaken arch-crown soil support and worsen settlement. At 1 m cavities, intact arch-base soil has strong rebound (max uplift ~2.5 mm), and undamaged arch-crown support causes minimal settlement. Cavities of 2–4 m are transitional: soil support is not severely impaired, so the gap between arch-crown settlement and arch-base uplift is smaller. For cavities > 4 m, large ones weaken arch-top soil support (settlement reaches 5.9 mm at 4 m), while also impairing arch-bottom soil integrity, reducing rebound capacity and thus uplift.

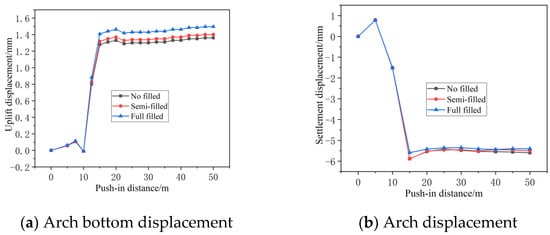

4.1.3. Influence of Backfill Condition on Tunnel Surrounding Rock Displacement

Figure 8 presents displacement variation curves for the tunnel under different karst-cavity-filling conditions. The figure reveals that when karst cavities exist beneath the pipe jacking tunnel, the filling status of these cavities has a negligible effect on displacement changes at monitoring points on the crown and base of the tunnel arch. The greater the amount of cavern filling material, the larger the upward bulging of the tunnel crown, while the downward settlement of the tunnel crown decreases. Furthermore, the filling condition of the cavern material has almost no effect on the maximum settlement value of the tunnel crown. This is due to more cavern fill providing stronger support under the tunnel: post-arch excavation and a greater rebound force cause more uplift, while the surrounding soil compacts more—stabilizing arch-crown loads and reducing settlement. Meanwhile, the max arch-crown settlement stays nearly unchanged, as it mainly depends on the total weight of the overlying soil layer. The fill does not change this weight, only distributing pressure more evenly, so the max settlement value remains unaltered.

Figure 8.

Tunnel displacement variation curves under different karst-cavity-filling conditions.

4.1.4. Influence of Spacing Between Karst Cavities and Tunnels on Surrounding Rock Displacement

To investigate how the relative distance between a pipe jacking tunnel and a karst cavity in composite strata affects rock mass stability, a numerical calculation model was established. The model assumes a cavity diameter of 2 m, with distances between the cavity and the tunnel bottom set at 1 m, 2 m, 3 m, and 4 m.

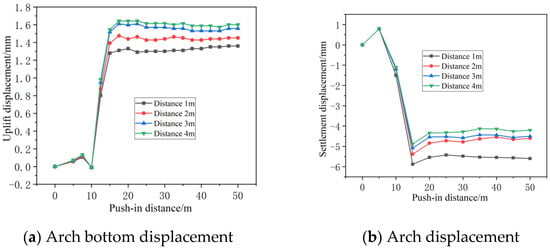

Figure 9 illustrates how the deformation of the tunnel-crown and crown-base rock mass changes as the pipe jacking advances. Research findings indicate that the greater the relative distance between the tunnel and the cavern, the larger the displacement at the crown base and the smaller the settlement at the crown. When the relative distance is 2 m, 3 m, or 4 m, the displacement difference between the crown and the base is smaller than when the relative distance is 1 m.

Figure 9.

Influence curve of spacing between karst cavities and tunnels on tunnel displacement.

At the start of the jacking operation, both the crown and base displacements increased rapidly. Displacement reached its maximum value when the excavation length reaches 15 m. Specifically, at a relative distance of 1 m, the maximum upward bulge at the arch bottom: 1.36 mm; the maximum downward settlement at arch crown: 5.6 mm. At a relative distance of 2 m, the maximum bulge at the arch bottom: 1.45 mm; the maximum settlement at the arch crown: 4.6 mm. At a relative distance of 3 m, the maximum arch bottom uplift was 1.56 mm, and the maximum arch crown subsidence was 4.5 mm; when the relative distance reached 4 m, the maximum arch bottom uplift was 1.60 mm, and the maximum arch crown subsidence was 4.2 mm.

This is because the greater the relative distance between the tunnel and the karst cavities, the less interference the cavities exert on the surrounding soil: the soil beneath the arch bottom provides more complete support, allowing for more substantial rebound after excavation, resulting in greater displacement (uplift) of the arch bottom; meanwhile, the soil above the arch crown experiences minimal stress influence from the cavities, leading to more stable deformation and consequently smaller settlement of the arch crown.

4.2. Analysis of Surrounding Rock Stress Response

4.2.1. Effect of Tunnel Burial Depth on Surrounding Rock Stress

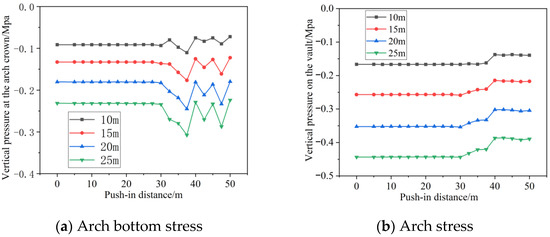

Figure 10 shows that tunnel crown pressure increases with greater burial depth. When the pipe jacking machine excavates directly above a karst cavity, crown pressure begins to decrease due to the redistribution of pressure released by excavation. Vertical pressure at the arch base rises when the pipe jacking machine reaches the cavity’s location, then decreases and fluctuates after excavation. This occurs because the heavier machine above the cavity increases earth pressure, which subsequently decreases as lighter pipe sections are advanced.

Figure 10.

Effect of burial depth on vertical stresses in tunnels.

Figure 11 shows the vertical stress field contour map of the surrounding rock after excavation for tunnels at different burial depths. Near the crown of the pipe-jacked tunnel, vertical stresses exhibit a “downward arching” phenomenon. This occurs because excavation disturbs the surrounding rock, reducing stress release at the crown. Stress values above and below cavities are low, attributed to the formation of a soil arch effect in the overlying soil during excavation, which redistributes vertical stresses horizontally.

Figure 11.

Stress field contour map of tunnel surrounding rock after excavation at different burial depths.

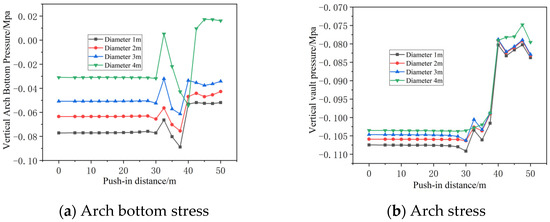

4.2.2. Influence of Cave Size on Tunnel Rock Mass Stress

Three-dimensional finite-element modeling was used to analyze caverns with diameters of 1 m, 2 m, 3 m, and 4 m, positioned 1 m above the bottom of the pipe jacking tunnel. Figure 12 shows the vertical earth pressure at the tunnel crown and base, along with its variation curve during pipe jacking advancement.

Figure 12.

Effect of karst cavity diameter on vertical stress in tunnels.

As shown in Figure 12, when only the diameter of the cavern is altered, a larger diameter results in reduced vertical pressure at the tunnel bottom. Prior to the jacking machine reaching 2 m directly above the cavern, vertical pressure begins to decrease due to excavation unloading; as the jacking machine passes through, pressure increases again. During subsequent excavation, the vertical pressure gradually decreases and stabilizes. The vertical pressure at the crown is less affected by changes in cavern diameter. Before the pipe jacking machine is 2 m directly above the cavern, the pressure also begins to decrease due to excavation unloading, then stabilizes within a 10 m range.

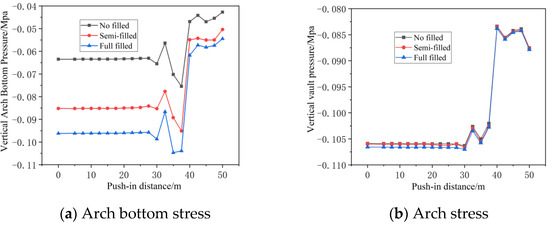

4.2.3. Influence of Backfill Condition on Tunnel-Surrounding Rock Stress

Figure 13 shows the curve illustrating the effect of cavern-filling conditions on vertical stresses in the tunnel. It can be observed that prior to the jacking machine reaching 2.5 m from the cavern, vertical stresses at the arch bottom and arch top monitoring points above the cavern remain largely unaffected. Under different filling conditions, the trend of stress variation at the arch bottom and arch top remains consistent. The greater the cavern filling, the higher the vertical stress at the arch bottom, while the impact of filling status on arch-top stress is negligible.

Figure 13.

Effect of karst-cavity-filling conditions on vertical stress in tunnels.

This is because the stress trends at the arch base and arch crown remain consistent under different filling conditions. The amount of filling only alters the strength of support, not the underlying stress logic. The more cavities are filled, the more solid the support at the arch base becomes, enabling it to bear greater pressure and thus generating higher vertical stress. Conversely, the stress at the arch crown primarily depends on the weight of the overlying soil layer; the filling beneath does not affect this weight, making its influence negligible.

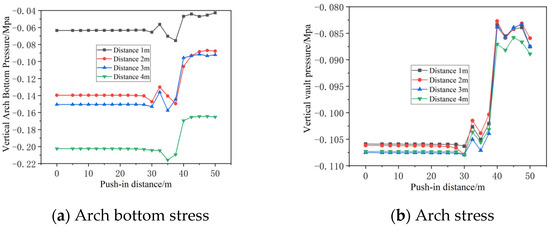

4.2.4. Effect of Spacing Between Karst Cavities and Tunnels on Surrounding Rock Stress

Finite element models were established at distances of 1 m, 2 m, 3 m, and 4 m from the tunnel bottom, with the karst cavity diameter fixed at 2 m. Figure 14 illustrates the variation in vertical pressure at the tunnel crown and crown base with advancing distance when the cavity is positioned 1 m, 2 m, 3 m, and 4 m from the tunnel top. Vertical pressure at the arch bottom rises as the relative distance between the cavern and tunnel grows. At short distances, within 2.5 m before the midpoint directly above the cavern, vertical stress at the arch bottom slightly decreases due to excavation unloading. Beyond this point, stress first increases then decreases before stabilizing. The vertical pressure at the arch crown shows little change with increasing distance from the cavern. It begins to decrease at 2.5 m ahead of the cavern and stabilizes approximately 10 m before the receiving end portal.

Figure 14.

Effect of distance between karst cavities and tunnels on vertical stresses in tunnels.

4.3. Pipe Section Displacement Response Analysis

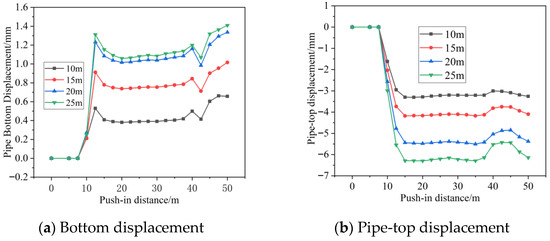

4.3.1. Effect of Tunnel Burial Depth on Segment Displacement

Figure 15 shows the vertical displacement contour map of pipe sections at different burial depths. To avoid stress concentration, the third pipe section was selected.

Figure 15.

Vertical displacement contour map of pipe sections at different burial depths.

Figure 16 shows the vertical displacement curves of pipe sections at different burial depths. Figure 15 presents the contour map of overall vertical displacement of the jacking pipe after excavation completion at various burial depths.

Figure 16.

Vertical displacement curves of pipe sections at different burial depths.

As shown in Figure 16, the vertical settlement values of the left and right arch ribs are essentially equal. At different burial depths, the vertical displacement of each characteristic point on the pipe section increases with increasing tunnel burial depths, with the maximum displacement occurring at the tunnel crown. The displacement of the pipe section increases sharply upon entering the soil before stabilizing. The uplift displacement at the pipe bottom increases 3 m before reaching directly above the karst cavity due to the jacking machine squeezing the cavity, then decreases upon reaching the cavity’s apex. The settlement displacement pattern at the pipe top is similar: displacement values decrease 3 m before reaching the cavity, increase again upon reaching the apex, and approach the stable values observed at greater distances. As burial depth increased from 10 m to 25 m, the final pipe-bottom displacements were 0.66 mm, 1.01 mm, 1.33 mm, and 1.41 mm, respectively. The pipe-top settlement values were 3.26 mm, 4.1 mm, 5.38 mm, and 6.14 mm, respectively. At 25 m burial depth, the settlement at the top of the pipe was approximately 4.35 times the uplift value, and the displacement values at 20 m and 25 m burial depths were relatively close.

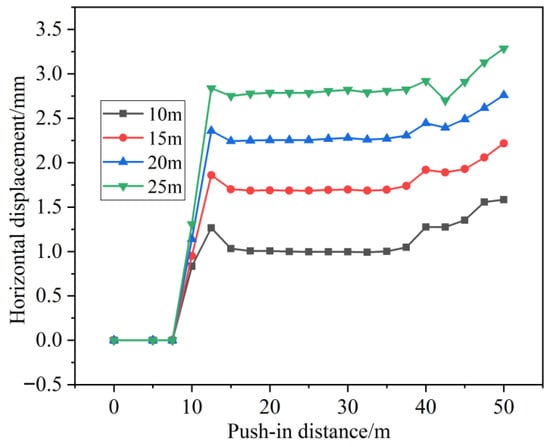

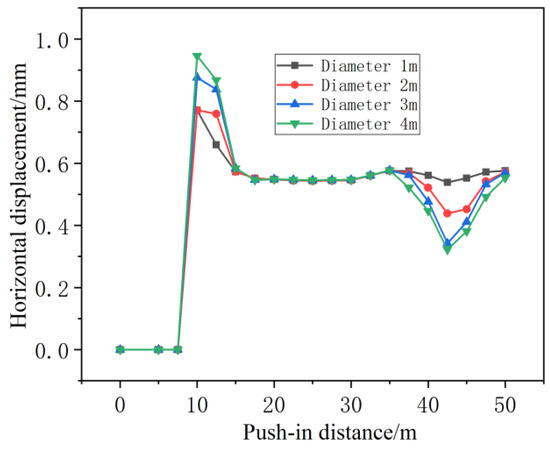

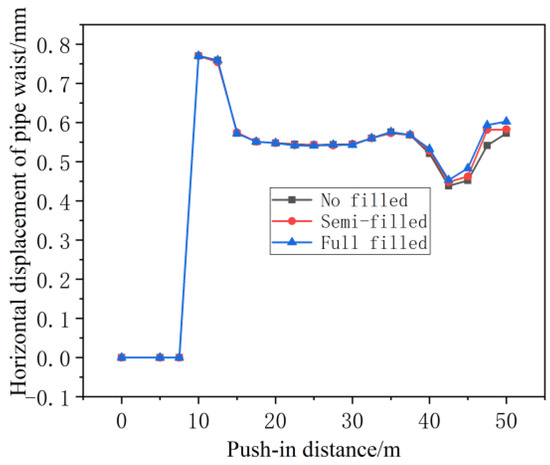

The horizontal displacement of the pipe jacking at different burial depths is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Contour map of horizontal displacement of pipe sections at different burial depths.

Figure 17 shows the horizontal displacement curves of the pipe waist at different burial depths.

As shown in Figure 18, the horizontal displacement of the pipe section increases with burial depth. At a burial depth of 25 m, the displacement was approximately 2.1 times that at 10 m. The lateral arching displacements at the mid-section of the pipe segment ultimately reached 1.58 mm, 2.22 mm, 2.76 mm, and 3.29 mm, respectively. The horizontal displacement was greater in the middle and upper sections due to the stable lower composite strata and significant deformation in the upper part. The horizontal displacement at the left and right arch crowns was nearly identical. The pipe section’s horizontal displacement increased sharply upon initial penetration into the soil before stabilizing, then began to increase again upon reaching the area above the karst cavities.

Figure 18.

Horizontal displacement curves of pipe waist at different burial depths.

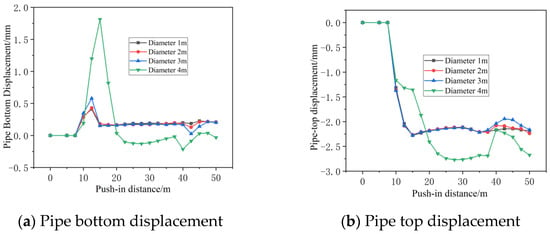

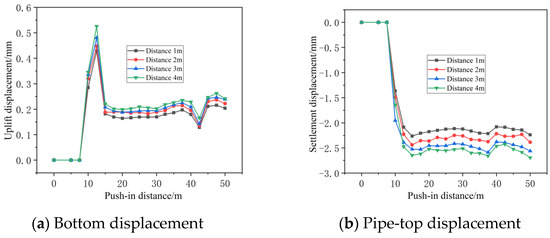

4.3.2. Effect of Cave Size on Segment Displacement

Figure 19: vertical displacement curves of pipe segments under different cavern sizes. Figure 20: horizontal displacement curves of pipe mid-sections under different cavern sizes.

Figure 19.

Vertical displacement curves of pipe sections at different cave dimensions.

Figure 20.

Horizontal displacement curves of pipe waist at different cave dimensions.

Figure 19 and Figure 20 show that the vertical displacement of pipe segments is similar for caverns with diameters between 1 and 3 m, but increases significantly at 4 m, with the maximum uplift at the pipe bottom being approximately 3.5 times greater than for other diameters. When the pipe section advances over the karst cavity, displacements at the pipe bottom, top, and waist decrease. The pipe-top displacement increases sharply as the section enters the tunnel before stabilizing; larger cavities cause greater displacement, which is significantly larger than the pipe bottom displacement. The horizontal displacement pattern of the pipe arch waist is similar to that of the pipe bottom: larger cavities result in smaller horizontal displacement.

This occurs because when the pipe section passes over a karst cavity, support exists beneath it, reducing displacement at the pipe bottom, top, and arch. When the pipe top first enters the tunnel without support, displacement suddenly increases before stabilizing. Furthermore, larger cavities cause greater displacement at the pipe top, which is significantly larger than the displacement at the pipe bottom. Horizontal displacement at the arch waist is similar to that at the pipe bottom: larger cavities result in looser surrounding soil and weaker confinement, leading to smaller displacement.

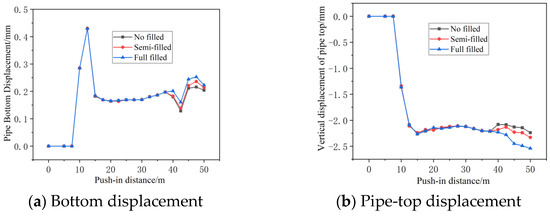

4.3.3. Effect of Grout Filling Condition on Segment Displacement

The vertical displacement curves for pipe segments under different backfill conditions are shown in Figure 21, while the horizontal displacement curves for pipe mid-sections under different backfill conditions are presented in Figure 22. The figures indicate that when the pipe segment approaches the karst cavity within 5 m, deformation trends and magnitudes are similar regardless of backfill presence. Increased filling volume ultimately leads to slightly greater displacement in all directions for the pipe section. This occurs because the intact formation and enhanced bearing capacity after filling cause stress release in the excavated soil, resulting in increased upward uplift forces on the pipe section. Increasing grout volume ensures sufficient soil support strength, reduces the risk of jacking machine nose failure, and guarantees safe pipe jacking excavation.

Figure 21.

Vertical displacement curves of pipe sections with different filling conditions.

Figure 22.

Horizontal displacement curves of pipe waist at different filling conditions.

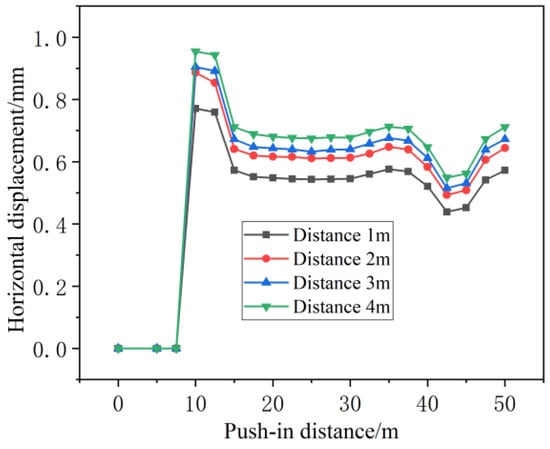

4.3.4. Effect of Spacing Between Karst Cavities and Tunnels on Segment Displacement

As shown in the Figure 23, significant displacement changes occur during the initial stage of the pipe section entering the tunnel. As the distance between the cavern and the tunnel steadily rises, both the vertical and horizontal displacements of the pipe section exhibit a progressive upward trend. When the pipe section advances to the area directly above the karst cavity, the relatively weaker support provided by the overlying soil above the cavity leads to a reduction in soil heave. This indicates an increased likelihood of the jacking machine to experience a nose-down phenomenon, potentially causing the pipe section to sink. Concurrently, the soil pressure on the pipe top decreases accordingly, resulting in a slight rebound of the settlement. Additionally, the horizontal displacement at the mid-section of the pipe also exhibited a decreasing trend.

Figure 23.

Vertical displacement curves of pipe sections at different spacings between karst cavities and tunnels.

The horizontal displacement at the pipe waist position is shown in Figure 24 below.

Figure 24.

Horizontal displacement curve of the pipe waist at different spacings between caves and tunnels.

4.4. Stress Response Analysis of Pipe Sections

4.4.1. Effect of Tunnel Burial Depth on Segment Stress

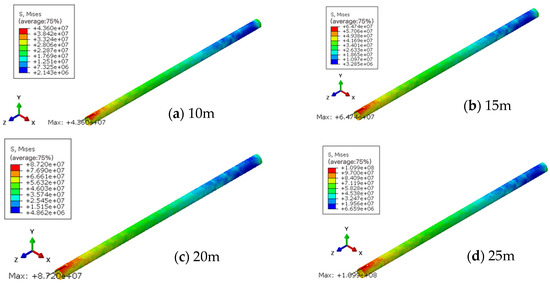

Figure 25 displays the Mises stress distribution contour map of the pipe section after completion of the pipe jacking excavation operation. This image clearly reveals that the maximum Mises stress occurs at the upper center of the final pipe section. At a burial depth of 10 m, the maximum Mises stress is 43.6 MPa. When the burial depth increases to 25 m, the maximum Mises stress rises to 109.9 MPa—a 2.52-fold increase compared to the stress value at 10 m.

Figure 25.

Mises stress distribution contour map of the pipe section after excavation operations.

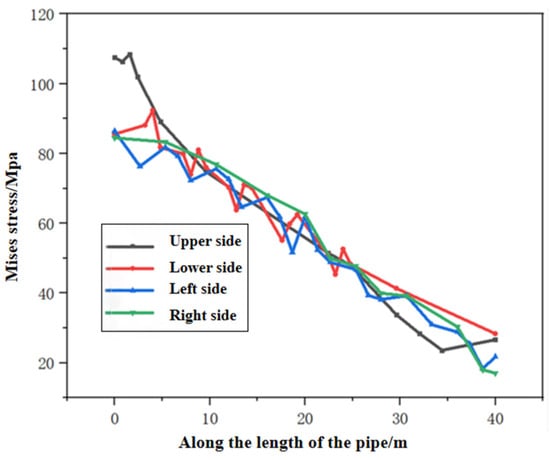

The Mises stress gauges are arranged at the top, bottom, left, and right of the pipe section. Based on these gauges, the Mises stress distribution across all gauges in the pipe body during the final jacking stage was measured, with the specific results shown in Figure 26. As observed in Figure 26, the Mises stress values in all directions are nearly consistent throughout the entire pipe jacking structure.

Figure 26.

Mises curves for different pipe jacking paths.

Since the Mises stress values are nearly uniform across all directions, the Mises stress values at the midpoint of the bottom of the third section of the pipe at different burial depths were selected to analyze their changes during the jacking process.

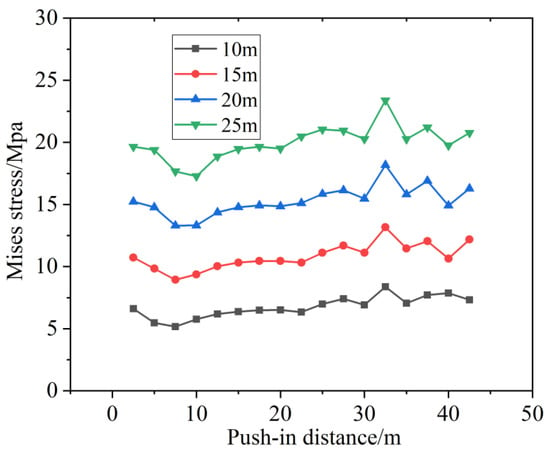

As shown in Figure 27, the Mises stress at each monitoring point rises with increasing burial depths, exhibiting a similar deformation trend. This is because the greater the burial depth, the greater the overburden pressure (vertical + lateral) borne by the measurement point. Since Mises stress reflects equivalent stress intensity, an increase in total pressure directly leads to a rise in its value.

Figure 27.

Mises stress curves for pipe segments at different buried depths in pipe jacking tunnels.

4.4.2. Effect of Cave Size on Segment Stress

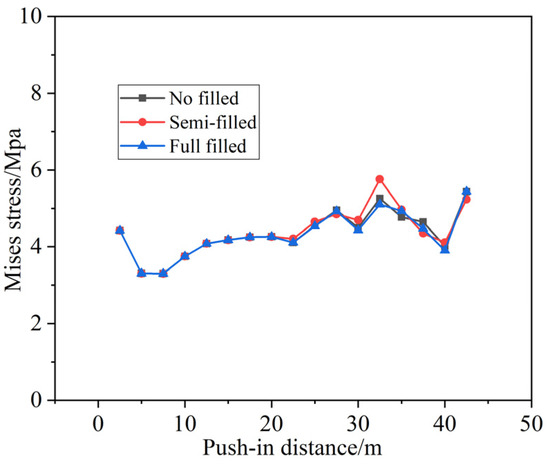

This figure illustrates how the Mises stress experienced by the pipe segments varies with different cavern sizes. As clearly shown in Figure 28, the fluctuations in Mises stress on the segments remain relatively small when cavern dimensions change. However, overall, stress incrementally increases as the jacking excavation progresses forward. The maximum stress value is approximately 5.5 MPa, while the minimum value is around 3 MPa.

Figure 28.

Mises stress curves for pipe sections at different cave dimensions.

When the size of a cavern changes, the Mises stress in the tunnel segments fluctuates minimally because the segments are rigid structures primarily bearing pressure transmitted from the surrounding soil. As long as the cavern does not completely undermine the supporting soil, the pressure transmitted to the segments remains relatively stable, resulting in small stress fluctuations.

Conversely, stress incrementally increases during the jacking and excavation advance. This occurs because as excavation progresses forward, the length of the segment exposed to soil pressure grows longer, leading to an accumulation of soil pressure. Consequently, the stress gradually increases.

4.4.3. Effect of Filling Conditions on Segment Stress

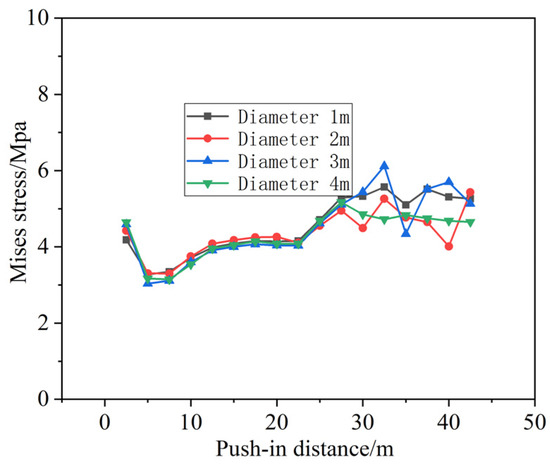

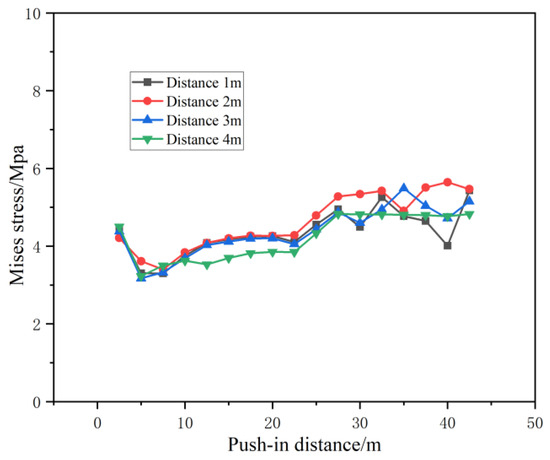

Figure 29 illustrates how the Mises stress of the third pipe section varies with the advancement of the jacking process under different filling conditions of the cavern (e.g., completely unfilled, partially filled, or fully filled). This figure clearly shows that the filling status of the cavern has minimal impact on the pipe section’s Mises stress. Moreover, throughout the entire jacking process, the Mises stress of the pipe section generally increases progressively.

Figure 29.

Mises stress curves for pipe sections under different filling conditions.

4.4.4. Effect of Spacing Between Karst Cavities and Tunnels on Segment Stress

Figure 30 illustrates the variation in Mises stress of the third pipe section during jacking construction, under conditions where the distance between the cavern and the tunnel differs. The figure clearly shows that the separation distance between the cavern and the tunnel exerts a negligible influence on the pipe section’s Mises stress. Furthermore, throughout the entire jacking process, the Mises stress of the pipe section generally increases gradually.

Figure 30.

Mises stress curves for pipe sections at different distances between caverns and tunnels.

5. Conclusions

(1) In composite geological tunnel construction scenarios, when karst cavities exist within the rock mass ahead of the tunnel, displacement values at the cavity’s mid-section (mid-cavity), roof area, surface above the roof, and surrounding rock ahead of the cavity all exhibit an increasing trend as the cavity’s scale expands. When the pipe jacking machine’s excavation face is relatively distant from the karst cavity, displacement changes at monitoring points remain minimal, limiting their impact on tunnel construction. However, as the excavation face progressively gets closer to the cavity—specifically within approximately 2.5 m—the rate of displacement change at monitoring points begins to accelerate significantly, with displacement values increasing sharply. Furthermore, both soft plastic clay and slurry demonstrate effective consolidation capabilities when addressing karst cavities, with no discernible performance difference observed between the two materials in terms of consolidation effectiveness.

Larger karst cave scale causes greater displacement of the cave wall, roof, overlying surface, and surrounding rock ahead of the excavation—this compresses pipe sections (causing cracks/misalignment), weakens roof rock bearing capacity (triggering collapse), induces ground subsidence (threatening nearby structures), and reduces working face stability. Pipe jacking machines have limited displacement impacts when far from the cave, but approaching the ~2.5 m critical distance leads to a sharp acceleration in displacement rate and magnitude. This elevates risk from manageable to high-hazard, making conventional controls ineffective and endangering equipment safety. Soft plastic clay and slurry show no significant differences in reinforcement effectiveness; flexible selection by site conditions can limit cavity-surrounding displacement, reduce construction complexity, and prevent reinforcement failure.

(2) When cavities exist beneath tunnels in composite strata, variations in cavity diameter significantly affect tunnel segment displacement. At a cavity diameter of 4 m, the reduced support capacity of overlying soil leads to increased settlement displacement at the tunnel segment crown. As the tunnel segments progressively advance in composite-formation tunnel construction scenarios, the displacement and stress states at the tunnel crown and base exhibit specific patterns when parameters such as burial depth, karst cavity diameter, internal filling material volume, and horizontal distance between the cavity and tunnel vary. Specifically, the arch-bottom region exhibits uplift, while the arch-top region experiences subsidence, with the subsidence at the arch top exceeding the uplift at the arch bottom. During the initial excavation phase, the displacement and stress fields—originally in a relatively stable state—become disturbed. This leads to a noticeable increase in displacement at monitoring points along both the arch bottom and arch top. As subsequent excavation progresses, displacement values will steadily level off.

The stress conditions experienced by the tunnel crown remain largely unchanged. Before the pipe jacking machine reaches the area directly above the karst cavity, stress states at both the crown and base of the tunnel section above the cavity remain relatively stable, showing no significant fluctuations. Once the pipe jacking machine reaches directly above the karst cavity, stress at the arch-bottom position above the cavity will increase, while stress at the arch-crown position will correspondingly decrease.

As can be seen, when the diameter of a karst cavity reaches 4 m, the weak soil support above causes a sharp increase in crown settlement, potentially damaging the pipe section. Changes in parameters such as tunnel burial depth and cavity diameter can result in crown settlement exceeding crown uplift, causing unbalanced forces on the pipe section and increasing the risk of misalignment and fracture. Displacement at the crown and base of the arch suddenly increases due to disturbance from prior excavation, posing a risk of surrounding rock collapse. When the pipe jacking machine reaches directly above a cavern, stress at the base of the arch increases (risking pipe-section crushing), while stress at the crown decreases (weakening support), further heightening the collapse risk. These changes can directly cause pipe section damage and surrounding rock instability, requiring focused management.

(3) When directly above the karst cavity, both the pipe-bottom uplift and pipe-top settlement will decrease. Additionally, the filling volume of the karst cavity has a relatively minor impact on pipe segment displacement. Under loading, the pipe section undergoes vertical compression deformation while simultaneously extending laterally on both sides, exhibiting an overall elliptical deformation profile.

During the excavation completion phase of the pipe jacking operation, the maximum Mises stress value was observed in the top region of the launch-end pipe section. Overall, the distribution of Mises stress along the pipe length is nearly uniform across different orientations. Research indicates that the diameter of cavities, the quantity of internal filling material, and variations in the spacing between cavities and the tunnel exert a relatively limited influence on the Mises stress experienced by the pipe sections. However, as excavation progresses, the Mises stress experienced by the pipe sections exhibits a gradual upward trend.

The upward bulging of the pipe bottom and reduced settlement at the pipe top directly above the cavern are beneficial for construction safety; however, the pipe section will exhibit elliptical deformation (vertical compression and lateral extension), potentially leading to joint leakage or structural cracking. Regarding stress distribution, the Mises stress at the launch-end crown reaches its maximum (representing a weak point), while stress along the pipe body remains uniform. Cave parameters (diameter, fill volume, and spacing) exert limited influence. However, continuous excavation progressively increases stress within the pipe section; exceeding the load-bearing limit will cause structural failure. Therefore, key control measures must focus on managing oval pipe section deformation, stress accumulation, and the crown weak point at the launch end to ensure construction safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W., J.X. and H.Z. (Haonan Zhang); Methodology, K.L., H.Z. (He Zhan) and H.Z. (Haonan Zhang); Software, D.W., J.X., Z.X. and H.Z. (Haonan Zhang); Validation, Z.X. and H.Z. (He Zhan); Data curation, Z.X.; Writing—original draft, D.W. and H.Z. (Haonan Zhang); Writing—review & editing, J.X., K.L. and H.Z. (He Zhan); Project administration, K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12462033) and this research was funded by Practical Innovation Project for Professional Degree Postgraduates of Yunnan University (Grant No. ZC-252512658).

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data will be made available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ke-wen Liu and Zan Xu were employed by the companies Yunnan Green Intelligent Construction Research Institute Co., Ltd. and China Railway Development Investment Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Sterling, R.L. Developments and research directions in pipe jacking and microtunneling. Undergr. Space 2020, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, F.; Zhang, M.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ni, L. A review on the key factors influencing the stability of shield tunneling. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Hao, J.; Wang, B. Numerical analysis of influence of karst caves beside the tunnel on stability of its surrounding rock mass. J. Chongqing Jianzhu Univ. 2003, 25, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, X.; Hao, J.; Wang, B. Numerical analysis of influence of karst caves in top of tunnel on stability of surrounding rock masses. Rock Soil Mech. 2003, 24, 445–449. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Hao, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, B. Model testing research on influence of karst cave size on stability of surrounding rock masses during tunnel construction. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2004, 23, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Xu, R.; Xu, X. Deformation modeling of surrounding-rock during full-face excavation of tunnel in karst regions. J. Tongji Univ. 2004, 32, 710–715. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; He, S.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, T. Characteristics, challenges and countermeasures of giant karst cave: A case study of Yujingshan tunnel in high-speed railway. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 114, 103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.C.; Cui, Q.L.; Shen, J.S.L.; Arulrajah, A.; Yuan, D.-J. Fractal prediction of grouting volume for treating karst caverns along a shield tunneling alignment. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhou, A.; Pan, Y.; Shen, S.L. Measurement and prediction of tunnelling-induced ground settlement in karst region by using expanding deep learning method. Measurement 2021, 183, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.Z.; Fan, H.J.; Yi, X.; Zou, L. Numerical analysis of influence of cavity distribution sites on the stability of the tunnel. Highw. Eng. 2013, 38, 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Huang, X.; Zou, G.; Deng, J. Pretreatment for Tunnel Karst Cave during Excavation: A Case Study of Guangxi, China. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9013815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.L.; Huang, F. Collapse mechanism of shallow tunnel based on nonlinear Hoek-Brown failure criterion. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2011, 26, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Nie, L.; Xue, Y.; Li, W.; Fan, K. Model testing on the processe, characteristics, and mechanism of water inrush induced by karst caves ahead and alongside a tunnel. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 5363–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.C.; Ni, C.; Huang, H.W.; Shen, J.S. The use of tunnelling parameters and spoil characteristics to assess soil types: A case study from alluvial deposits at a pipejacking project site. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 2933–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Lai, J.; Ma, E.; Xu, J.; Qiu, J.; Wang, W. Failure mechanism analysis and treatment of tunnels built in karst fissure strata: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 167, 109048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, M.; Sun, H.; Liu, R.; Lu, X. Detection and comprehensive treatment for giant karst caves under the tunnel floor: A case study in Guangxi, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coli, M.; Castellucci, P. Karst and tunnelling: A reverse impact case history. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 861, 062050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Peng, F.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, D. Grouting for tunnel stability control and inadequate grouting section recognition: A case study of countermeasure of giant karst cave. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.M.; Qi, T.Y.; Mo, Y.C. Numerical analysis and research on surrounding rock stability of lateral karst cave tunnels. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2009, 28, 3497–3503. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, L.; Jiang, X.Z.; Hou, W.M.; Xu, H.Y.; Ji, X.F. Model test on stability of large cross-section highway tunnel adjacent to caverns. Tunn. Constr. 2019, 39, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.Y.; Xie, B.; Li, Z.; Sun, X.H. Numerical analysis on influence of concealed karst caverns upon stability of metro shield tunnel. Tunn. Constr. 2020, 40, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Zhao, L.; Ling, T.; Yang, X. Rock mass collapse mechanism of concealed karst cave beneath deep tunnel. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 91, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Peng, Q.; Wan, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, B. Fluid-solid coupling analysis of rock pillar stability for concealed karst cave ahead of a roadway based on catastrophic theory. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2014, 24, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Liu, M.; Yu, Y.T.; Xu, S.; Xu, C.J.; Zheng, F.Q.; Huang, W.H.; Wu, Z.L.; Wan, J.X. Analysis of influence of tunnel through karst cave on deformationand internal force of lining structure. Hydropower Water Resour. 2024, 55, 435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Duan, Z.; Guo, D.P.; Zeng, B.; Wang, Q. Study on influence of different azimuth angles of concealed karst caveon the stress characteristics of tunnel lining tructure. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2023, 60, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Luo, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Z. Damage mechanisms of cave stratum in water-rich karst areas induced by tunneling. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2025, 68, 1620702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanimaschcool, M.; Bhasin, R. Three Dimensional Numerical Modelling of a Large Cavity Formed in an Underground Complex in a Hydropower Plant in the Himalayas. In Proceedings of the Paper presented at the 14th ISRM Congress, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 16–18 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.L.; Yan, C.H.; Yu, L.C.; Yan, C.; Li, H.; Xu, Y. Characteristics of shallow buried karst and its safety distance to tunnel in Wuxi city, Jiangsu province. J. Nanjing Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2023, 59, 890–899. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Wang, D.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, M. Prediction of the Collapse Region Induced by a Concealed Karst Cave above a Deep Highway Tunnel. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 8825262, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ren, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H. Investigation on the seepage-stress field evolution mechanism and failure process of karst tunnels in water-rich areas. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Yang, T.; Ju, B.; Qu, Z.; Yi, C. Analysis of the influence of karst cave parameters on surface settlement in TBM tunnelling. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci.-Tech. Sci. 2024, 72, e150110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.G.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y. Research on the impact of karst cave relative angle on tunnel surrounding rock deformation. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2025, 6, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Eric, A.C.D.; Özgür, A.; Haluk, T. Levent Stability charts for the collapse of residual soil in Karst. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 135, 925–931. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.C.; Cao, M.Q. Study on the influence of karst cavity location on the stability of surrounding rock at the portal of a cross-pressure tunnel. West. China Commun. Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Augarde, C.E.; Lyamin, A.V.; Sloan, S.W. Prediction of undrained sinkhole collapse. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2003, 129, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, D.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Deng, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, H. Analysis of additional stress on the surrounding rock during a Large Diameter Shield Passing Through the Areas with Karst Strongly Developed. In Application and Development of Data Simulation and Mechanical Analysis in Civil Engineering ICCE 2024; Feng, G., Zhang, B., Wang, X.Y., Zhao, J., Almerich-Chulia, A., Eds.; Sustainable Civil Infrastructures; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, X.Y.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, F. Deformation characteristics for shallow karst sections during tunnel-entering construction. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 6, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, X.Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, C.L. Investigating the factors influencing the mechanical behavior of tunnel lining Structures in karst Regions. J. Transp. Eng. 2024, 24, 56–62+81. [Google Scholar]

- Phoon, K.K.; Shuku, T.; Ching, J. (Eds.) Uncertainty, Modeling, and Decision Making in Geotechnics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.P.; Hou, S.M.; Zhang, Y.M.; Gao, Y.H.; Liu, X.R. Energy evolution and constitutive model for damage of degraded limestone undercoupling effects of hydrodynamic-stress-chemical corrosion. Chin. Ournal Geotech. Eng. 2025, 47, 759–768. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.Y.; Zhang, M. Statistical regularity of physical and mechanical indexes of secondary red clay in Chenggong district, Kunming. Coal Geol. Explor. 2021, 49, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.Q.; Atkinson, B.K. Stress corrosion cracking of quartz: A note on the influence of chemical environment. Tectonophysics 1981, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, M.; Dez Vareh, G.; Bazzaz Zadeh, R. Corrosion prediction using the weight loss model in sewer pipes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 199, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, G.; Zhao, T.T.; Zhang, W.Y.; Hu, F.; Zhou, W. FDEM simulation for granular materials based on exact scaling and coarse granulation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 46, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).