1. Introduction

The shadow economy (SE), often referred to as the “hidden” or “underground” economy, represents a substantial and dynamic segment of global economic activity. It encompasses all economic actions that, while not inherently illegal, remain unregulated or untaxed, falling outside the formal economic framework [

1]. Understanding the drivers and consequences of the SE is vital, as it significantly impacts government revenues, policy implementation, and overall economic development. While the SE poses challenges such as revenue loss and informality, it also provides a safety net for individuals excluded from the formal sector, especially in economically unstable regions [

2].

Understanding and addressing the challenges posed by the SE is especially crucial for policymakers to ensure inclusive and sustainable economic development. It is important to note that while the SE presents certain challenges, it also offers opportunities for innovation and resilience within the broader economy.

Addressing the SE is a complex issue that requires comprehensive and nuanced economic policies. These might include efforts to reduce regulatory burdens, improve the business environment, and enhance law enforcement, among others. At the same time, it is important to recognize the resilience and entrepreneurial spirit within the SE and to consider how these qualities can be harnessed for the benefit of the formal economy.

The shadow economy (SE)—comprising legal but unregulated, untaxed, or unreported economic activities—presents a dual challenge for policymakers. While it can serve as a coping mechanism for individuals excluded from the formal labor market, it simultaneously undermines public finances, distorts competition, and erodes institutional trust. These tensions make the SE a particularly pressing issue in recent transitional economies, or ones that have a specific lag effect of transition processes, where institutional frameworks are often underdeveloped and enforcement is inconsistent.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) exemplifies this challenge, as it is one of the largest shadow economies in the Western Balkans. Although this is not unique in the region, BiH’s situation is exacerbated by its fragmented post-conflict governance structure, which has led to uneven regulatory enforcement and weak institutional oversight. While this context is important, the focus of this study is on how these governance weaknesses—alongside high tax burdens, labor market rigidities, and corruption—contribute to the persistence of informality.

Sectors such as construction, retail, and agriculture are particularly prone to shadow economic activity in BiH. These sectors are also central to employment and GDP, making their vulnerability to informality especially problematic. The shadow economy in these areas not only reduces tax revenues but also weakens the formal economy’s structural integrity. Moreover, external shocks—including the 2008 global financial crisis, the 2014 floods, and the COVID-19 pandemic—have had a reflection on informal activity, pushing more individuals and businesses outside the formal system.

Compared to neighboring countries like Serbia and Croatia, which have implemented targeted tax and regulatory reforms to reduce informality, BiH has lagged behind. This regional contrast underscores the need for updated country-specific empirical research to inform effective policy responses.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) stands out with one of the highest shares of SE in the region, estimated at 30% to 40% of its GDP [

2,

3]. This high prevalence highlights BiH’s unique economic and governance dynamics, which perpetuate informal activities and limit economic formalization. Addressing these issues is a prerequisite for sustainable economic development.

BiH’s shadow economy is rooted in its post-conflict context, shaped by the Dayton Peace Agreement of 1995. This agreement established a complex and fragmented governance system comprising two entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republic of Srpska and Brčko District, each with distinct fiscal and administrative frameworks. While this structure aimed to ensure political stability, it inadvertently created inefficiencies and loopholes in economic governance, facilitating the growth of informal economic activities.

BiH, a post-conflict transitional economy with a complex institutional structure and a historically large shadow economy, presents a unique case for analysis, particularly as the post-COVID-19 period saw widespread declaration of previously unreported income due to subsidy eligibility—creating a temporary formalization effect—while data prior to 1996 are unavailable due to the country’s establishment following the Dayton Peace Agreement.

Moreover, corruption and institutional weaknesses exacerbate the problem. Surveys consistently reveal low levels of trust in public institutions in BiH, driving both businesses and individuals to operate informally [

4]. Informal employment is especially prevalent in key sectors such as construction, retail trade, and agriculture, which are characterized by high levels of cash transactions and minimal oversight. For many low-income households, informal work provides a crucial safety net in the absence of effective social protection mechanisms, but this reliance on informality undermines long-term economic stability [

5].

Another significant driver of the SE in BiH is its inefficient tax system. High tax burdens, coupled with complex regulations and inconsistent enforcement, discourage compliance among small and medium-sized enterprises [

3]. The absence of streamlined procedures and effective inspection mechanisms allows many businesses to avoid registration and taxation, contributing to the persistence of informality. Comparatively, regional neighbors such as Serbia and Croatia have implemented tax reforms and regulatory adjustments to address similar issues, achieving better results in reducing their SEs [

6].

Global factors also influence BiH’s shadow economy. For instance, the 2008 global financial crisis disrupted formal economic activities, pushing many into informality. While other countries in the region have used the post-crisis period to implement structural reforms, political deadlock and institutional inertia have delayed similar measures in BiH [

2]. Consequently, the informal sector remains a dominant feature of the country’s economic landscape.

Measuring the SE is inherently challenging due to its hidden nature. The MIMIC (Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes) model is a widely adopted methodological framework for estimating the size of the SE. This approach integrates causal factors, such as unemployment and tax burdens, with observable indicators like cash demand and labor market discrepancies to estimate the SE as a latent variable [

7]. While the MIMIC model has been extensively used in regional and global studies, its application to BiH provides an opportunity to uncover specific dynamics and address criticisms related to its assumptions and sensitivity to variable selection [

8].

Despite the scale and implications of the SE in BiH, empirical studies remain limited—largely due to data constraints and the methodological challenges of measuring informal activity. This study addresses that gap by applying the Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes (MIMIC) model, a well-established extension of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), to estimate the size and evolution of the shadow economy in BiH from 1996 to 2022. The MIMIC model is particularly well-suited for this context because it treats the shadow economy as a latent variable—unobservable directly but inferable through observable causes (e.g., tax burden, unemployment) and indicators (e.g., institutional quality, corruption). This approach allows for a more nuanced and statistically robust analysis, especially when direct measurement is not feasible.

Furthermore, this approach tries to avoid common pitfalls such as arbitrary benchmarking and addresses concerns about variable stationarity and model specification. By doing so, it provides a more reliable foundation for understanding the drivers and dynamics of informality in BiH.

This paper contributes in three key ways:

It offers updated, methodologically rigorous estimates of the shadow economy in BiH.

It integrates both institutional and macroeconomic drivers using a latent variable framework.

It provides evidence-based insights to inform policy reforms aimed at reducing informality and strengthening governance.

This study is guided by the central research question: What are the main drivers, how have the dynamics of the shadow economy in Bosnia and Herzegovina evolved over time and how can this understanding inform more effective, context-specific policy responses in transitional economies like BiH?

The MIMIC method in this study extends Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and consists of two parts: the causal part and the measurement part. The first part describes causality within the model. It is more straightforward to understand from a conventional econometric perspective, which also makes it more susceptible to criticism in mainstream literature. The second part aims to measure SE as a latent variable. This latent variable is defined based on directly measurable indicators. The effectiveness of these indicators in the measurement process is determined by their loadings and the overall performance of the model. However, this part is often treated as a “black box” in the mainstream MIMIC approach.

This study applies the MIMIC model to examine the drivers and dynamics of the SE in BiH. By addressing both its structural causes and measurement challenges, the research aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the informal sector in transitional economies. Developing effective policies to reduce the SE is crucial for improving fiscal stability, promoting inclusive economic growth, and enhancing governance in BiH. Furthermore, insights from this study can inform policy debates in other transition economies facing similar challenges.

The remainder of this paper is structured in the following manner. The subsequent section provides a review of pertinent literature.

Section 2 delves into the theoretical underpinnings of the methodologies employed in the analysis and the data.

Section 3 unveils the findings of the empirical investigation.

Section 4 engages in a discussion of the research outcomes, and

Section 5 furnishes concluding observations.

Literature Review

The shadow economy (SE) consists of activities not formally registered or regulated by authorities and is often conducted visibly but outside the official economic framework. A significant number of countries in the Western Balkans grapple with the shadow economy, making up a substantial double-digit percentage of their GDP. Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is a case in point, with SE accounting for approximately one-third of its official GDP [

9].

The informal sector, comprising legal but unregulated and untaxed economic activities, remains a persistent challenge in economies that struggled and have been struggling with transition for decades. This struggle is imminent for Western Balkan (WB) countries, and BiH is one of them.

In BiH, it is estimated to account for approximately one-third of GDP, yet empirical research on its scope and drivers remains limited. This study aims to address that gap by applying the MIMIC model to estimate the size and evolution of the SE in BiH from 1996 to 2022 [

3].

Several methods have been developed to estimate the SE, including direct approaches (e.g., surveys, audits) and indirect methods (e.g., currency demand, electricity consumption, labor market discrepancies). While these methods offer valuable insights, they often suffer from data limitations, respondent bias, or narrow applicability [

10,

11]. In contrast, the MIMIC model—an extension of SEM—treats the SE as a latent variable inferred from observable causes (e.g., tax burden, unemployment) and indicators (e.g., institutional quality, corruption). This makes it particularly suitable for contexts like BiH, where informal activity is widespread and direct measurement is difficult [

1,

12].

The MIMIC model has been widely applied in developed and developing countries, including France [

13], Jordan [

14,

15], Egypt [

13], and Serbia [

5]. More recent studies have extended its use to transitional and developing economies, emphasizing its adaptability to complex institutional environments. For instance, Wang et al. [

16] examined the role of governance indicators in shaping the SE across developing countries, while Hassan [

17] explored how regulatory quality affects informal financial activity in Southern Africa. Similarly, Abou Ltaif et al. [

18] investigated the SE in Lebanon amid financial crisis, highlighting the interplay between global shocks and local institutional weaknesses.

Despite its strengths, the MIMIC model has faced methodological critiques. Scholars have questioned its reliance on arbitrary benchmarking to produce point estimates, its sensitivity to variable selection, and its vulnerability to non-stationary time series data [

19,

20]. Smrčková and Brůna [

21] further caution against implausible estimates when theoretical definitions and calibration benchmarks are misaligned. This study addresses these concerns by avoiding benchmarking, incorporating structural breaks, and rigorously testing for stationarity. These refinements enhance the model’s robustness and credibility, particularly in a transitional setting like BiH.

The theoretical foundation of this study draws on institutional theory and tax compliance theory. Institutional theory posits that weak governance—characterized by low rule of law and high corruption—creates incentives for informal activity [

22,

23,

24]. Tax compliance theory suggests that high tax burdens, complex regulations, and inconsistent enforcement discourage formalization and push economic actors into the informal sector [

25,

26]. These frameworks are especially relevant in BiH, where fragmented governance and regulatory inefficiencies have historically contributed to informality.

Earlier studies on BiH’s shadow economy provided foundational insights but were limited by outdated data and did not account for recent structural shocks such as the 2008 global financial crisis, the 2014 floods, or the COVID-19 pandemic [

3]. This study fills that gap by using updated data from 1996 to 2022 and explicitly modeling structural breaks to capture the impact of these events.

Based on the reviewed literature and theoretical considerations, this study explores two central propositions. First, higher tax burdens are expected to correlate with increased informal economic activity, as individuals and firms seek to avoid excessive fiscal pressure. Second, the quality of institutional governance—particularly in areas such as rule of law and corruption control—is anticipated to significantly influence the extent of informality. These propositions guide the empirical investigation into how macro-institutional conditions shape the dynamics of the shadow economy in BiH.

This research contributes to the literature in several key ways. It provides updated empirical estimates of the SE in BiH over a long-time horizon, capturing the effects of major structural events. Further, it refines the MIMIC methodology by addressing known limitations, including variable stationarity and benchmarking. It also contributes to theory-building by linking empirical findings to institutional and tax compliance theories. Finally, it offers policy-relevant insights for BiH and other similar economies seeking to reduce informality and strengthen governance.

To estimate SE, various methodologies have been developed. Among these, the MIMIC (Multiple Indicators, Multiple Causes) method is widely used. This method, derived from Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), treats SE as a latent variable influenced by observable causes and effects [

2]. Despite its widespread use, MIMIC has faced criticism for its oversimplification of causal components and reliance on arbitrary benchmarking [

19].

The MIMIC methodology, despite its evolutionary path and susceptibility to critique, is commonly employed for SE estimation [

2]. This technique consists of two components: the first delineates causality, and the second quantifies the shadow economy as a hidden variable. The causal part is more readily understood from a traditional econometric standpoint, making it more prone to critique in mainstream literature [

19]. The second component, where the hidden variable is defined by directly measurable indicators, is often treated as a “black box.” This paper seeks to unpack this “black box,” highlighting critical procedural steps vital for overall robustness and addressing certain criticisms related to the model’s causal component.

Earlier applications of MIMIC to BiH (1998–2016) revealed a declining SE trend, from 43% to 30% of GDP, influenced by key events such as tax reforms in 2006 and the global financial crisis [

3]. This paper extends previous studies by incorporating new data, addressing critiques of the MIMIC method, and refining its interpretation in light of structural economic changes (in the context of the financial crisis, catastrophic events, and the subsequent economic situation’s impact on SE).

The MIMIC model has gained traction across disciplines, particularly in social sciences [

27,

28,

29,

30], and psychology [

31]. Its popularity stems from its ability to handle multivariate data and its accessibility through advanced statistical software. Harlow et al. [

32] demonstrated that SEM was the second most popular multivariate analysis in European journals in 2008, likely due to the availability of specialized software [

33].

Recent empirical studies on the evaluation and growth of SE have yielded numerous findings in the field of economics, yet there remains a lack of agreement on several facets related to this subject. Firstly, there is not a single, universally accepted term that encapsulates this concept. Rather, it is referred to by various terms such as non-observed, irregular, unofficial, shadow, black, gray, hidden, and unobserved economy [

34].

Quantifying SE is a challenging endeavor due to its intricate and concealed characteristics, which is mirrored in the diverse methodological strategies employed for its measurement. An initial broad classification distinguishes between direct and indirect methods, with each category encompassing a range of methodological approaches that have been extensively discussed in the literature [

1,

7,

12,

35].

Direct methods presuppose the execution of statistical activities, carried out either by a national statistical organization or a non-governmental entity. Each alternative involves the application of a complex survey structure, particularly in the case of BiH, which has a multifaceted state framework that poses a significant obstacle to routine statistical activities. This methodology entails the gathering and examination of microdata. However, data collection confronts the issue of respondents reporting their involvement in some form of unofficial activity.

The indirect method presumes a macroeconomic viewpoint, from which six specific methods can be delineated. The first three methods are predicated on the volume of currency in circulation [

10,

11,

36]. The fourth method adopts a labor economics standpoint and concentrates on the disparity between actual and formal employment [

37,

38]. The subsequent approach uses electricity consumption as a gauge for economic activity [

39]. While this group of methods appears to offer a straightforward resolution to the issue, it is not without its shortcomings [

24,

40].

In conclusion, the MIMIC model is widely recognized in conventional literature and positions SE as a latent variable influenced by multiple causes and effects [

22,

41]. A latent variable, while not directly measurable, can be indirectly defined or identified through indicators. These indicators are quantifiable variables that share a correlation with the latent variable. By observing the pattern of their joint movements, researchers can indirectly determine the relative intensity of variations in the latent variable.

However, critics of the macroeconomic perspective on measuring SE argue that it should be grounded in consumer theory [

42]. Moreover, the econometric implementation of the procedure has faced criticism, with several authors responding to these critiques [

20,

43]. Other criticisms address issues of data transformation and measurement units. Nonetheless, this paper also focuses on disputes related to variables in the causal part of the model and arbitrary benchmarking in the process of index construction [

19].

In conclusion, a substantial amount of research has been conducted on the SE in both developed and less developed countries [

44]. Interestingly, less developed countries, despite having a larger SE relative to their official economic activity, also have less developed statistical systems. This paradox creates challenges in effectively measuring the SE, whether using direct or indirect approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

The MIMIC model is grounded in the concept of latent variable modeling and is primarily a confirmatory approach rather than an explanatory one. Both Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) are integral components of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and were originally developed as standard procedures in psychometrics. EFA, first introduced by Spearman in 1904, has become a widely utilized tool for theory evaluation in psychology.

The outcomes of EFA are influenced by various factors inherent in the dataset, and these results can be leveraged for further psychometric analysis. In the field of economics, these factor scores or factor score estimates have diverse applications. Economic researchers have recognized this and integrated it with covariance structural modeling. However, they often overlook the process of constructing factor scores, neglecting the specificities of applying the original methodological approach to datasets generated within the context of psychological research.

In comparison to other models, such as the traditional regression models, the MIMIC model offers a more nuanced approach by accounting for latent variables that are not directly observable but are inferred from other variables. Unlike simple regression models that assume a direct relationship between observed variables, the MIMIC model allows for the inclusion of multiple indicators and causes, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying constructs.

Another model often compared with MIMIC is the path analysis model, which also falls under the SEM umbrella. While path analysis focuses on the direct and indirect relationships between observed variables, the MIMIC model extends this by incorporating latent variables, thus offering a richer framework for understanding complex relationships.

In this paper, we employ the MIMIC model for Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), taking into account the constraints of its use within reasonable boundaries, in accordance with the existing relevant literature.

SEM can be written as follows:

where

is a

and each

is a possible cause of the unmeasurable (latent) variable

and

are a

vector of coefficients representing the relation between the latent variable and its predictors, which are exogenous.

The relation (1) stands for the structural part of SEM representing the underlying relationship between the SE and its observable causes. In this framework, the shadow economy is treated as a latent variable—something that cannot be directly measured but can be inferred through its associations with other measurable factors. These factors, known as exogenous causes, typically include variables such as tax burden, unemployment rates, and the quality of institutional governance. The model assumes that these causes influence the size and dynamics of the shadow economy in a linear fashion. The strength and direction of each cause’s influence are captured by a set of coefficients, which quantify how changes in the observable variables are expected to affect the latent variable. Additionally, the model includes an error term to account for other unobserved influences that might affect the shadow economy but are not explicitly included in the model. This error term is assumed to be normally distributed and uncorrelated with the causes, ensuring that the model remains statistically valid and interpretable.

The MIMIC model has other measurement parts that can be expressed as follows:

where

y =

y1,

y2, etc., and

yp is a (

p × 1) of measurable variables that are indicators for (indirect) measuring of latent variables. λ is a vector of coefficients describing the relationship between a latent variable and its indicators, and ε is an error term vector.

Finally, MIMIC presents a combination of relations (2) and (3). In such a multivariate model, endogenous variables

yj,

j = 1, and

p are indicator variables of the SE variable

η, and exogenous variables

xi,

i = 1, and

q are regressors of SE

η. First, it is obvious from relation (2) that the SE variable can be expressed in the following matrix form:

Hence, from Equations (2) and (3), we have

Relation (2) stands for the measurement part of the proposed model and establishes the connection between the latent variable, such as the shadow economy, and a set of observable indicators that serve as indirect measures of this hidden construct. These indicators might include variables like cash usage or discrepancies in labor market data, which are assumed to reflect the presence and intensity of informal economic activity. Each indicator is associated with a factor loading, which quantifies how strongly it is influenced by the latent variable. These loadings help determine the reliability and relevance of each indicator in capturing the underlying concept. Additionally, the model accounts for measurement errors, which represent random noise or inaccuracies in the observed data. The assumptions underlying this part of the model include a linear relationship between the latent variable and its indicators, the independence of measurement errors from both the latent variable and each other, and the idea that the latent variable is the sole common source of variation among the indicators. This structure ensures that the model can validly infer the unobservable phenomenon from the observed data. Further, relation (3) represents an algebraic rearrangement of the measurement model, aiming to isolate the latent variable from the observed indicators. The key assumption here is that the matrix of factor loadings is invertible, which allows for this transformation to be mathematically valid. Also, the measurement errors are either small enough to be negligible or can be reasonably estimated. Finally, relation (4) combines the structural and measurement parts into a reduced-form equation that expresses the indicators (y) directly as a function of the causes (X).

A latent variable is one that cannot be directly measured but can be indirectly identified through indicators [

29]. These indicators are measurable variables that correlate with the latent variable. By observing the pattern of these indicators’ co-movements, researchers can indirectly determine the relative intensity of variations in the latent variable.

Researchers often aim to define the extracted factor as an index or factor scores. This process typically begins with the production of relative weights, followed by a normalization procedure, as it is not feasible to determine the scale of all parameters. However, directly interpreting such an index could potentially lead to incorrect conclusions. Therefore, it is crucial to interpret this index correctly, which involves respecting all theoretical assumptions used in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). SEM was initially developed for measuring “general performance” in psychological studies, aiming to quantify something that is not directly observable.

Interpreting latent variables and their indicators correctly has significant implications for research validity. Ensuring that the indicators accurately reflect the latent variable is crucial for construct validity. Latent variables help account for measurement error by using multiple indicators, enhancing the reliability of the results. Misinterpreting theoretical assumptions can lead to incorrect conclusions, compromising the validity of the research. Clear and accurate interpretation ensures that findings are robust and reliable.

Theory plays a crucial role in SEM by guiding model specification, hypothesis testing, and ensuring construct validity. It helps researchers understand the meaning of relationships between variables and assess model fit. Theory also supports the generalizability of findings and fosters the development of new models. Without a strong theoretical foundation, SEM analyses may lack coherence and relevance.

The MIMIC model was chosen over path analysis and traditional regression models because it allows for the simultaneous estimation of both the causes and indicators of a latent variable, such as the shadow economy. Unlike path analysis, which deals only with observed variables, and regression models, which cannot capture unobservable constructs, the MIMIC approach integrates causal and measurement components in a single framework, making it ideal for latent phenomena [

1].

Normalization can be executed in different ways, but the usual procedure is the one proposed by Giles and Tedds, adopting the convention of setting the first element of λ to be unity, as

λ1 = 1. The data are a time series of observations

t = 1, …,

N [

45]. This use of standardized variables makes the overall process sensitive to the units of measurement and results in justified criticism [

46].

Finally, this paper uses the lavaan package that is developed to provide researchers with a free, open-source, but commercial-quality package for latent variable modeling in R programming surrounding [

47].

The methodological choice is further validated by its extensive use in prior studies, including Buehn and Schneider [

13], who applied the MIMIC model with cointegration and error correction techniques to the French shadow economy and demonstrated that even a limited set of institutional indicators—such as corruption and legal system quality—can yield robust results. Similarly, Breusch [

19] critically examined the assumptions and transformations in MIMIC applications, reinforcing the importance of methodological rigor. More recent applications, such as those by Alfoul et al. [

14] for Jordan and Mai and Schneider [

48] for Egypt, confirm the model’s adaptability across diverse economic contexts. These studies collectively support the continued relevance of the MIMIC framework in contemporary research on informal economies, particularly when data constraints or structural complexities necessitate parsimonious yet theoretically grounded modeling strategies.

2.1. Model Specification

This analysis employs a relatively straightforward MIMIC procedure for BiH. The simplicity is most evident in the causal part of the model, which includes only three regressors. This section of the model has faced substantial criticism. However, by limiting the number of predictors, we simplify relation (1), thereby reducing the likelihood of complications arising from interactions between independent variables. This approach aligns with the extensive literature on the subject [

19]. Additionally, we emphasize the measurement part of the model and refer to literature related to psychometric quantitative analysis, where SEM is highly regarded [

49].

We employed various model specifications, some of which had a hierarchical structure. In these models, the institution’s quality was established as a latent variable, determined by three indicator variables. However, none of these models yielded satisfactory fit indices.

Several limitations of the MIMIC approach are particularly relevant to BiH. The significant size of the informal economy in BiH, estimated to be around one-third based on previous studies, complicates the accurate measurement of economic activities. This large informal sector can introduce biases and inaccuracies in the model’s estimates. Additionally, the quality and availability of data in BiH can be inconsistent, affecting the reliability of the MIMIC model. Incomplete or inaccurate data can lead to erroneous conclusions and reduce the model’s validity. BiH’s complex political structure, with its two autonomous entities and the Brčko District, can lead to variations in data collection and reporting standards. This heterogeneity can pose challenges for the MIMIC model, which relies on consistent and comparable data. Furthermore, the economic instability in BiH, influenced by factors such as high unemployment rates and fluctuating GDP growth, can affect the stability and robustness of the MIMIC model. Economic volatility can introduce additional noise into the model, making it harder to draw reliable conclusions.

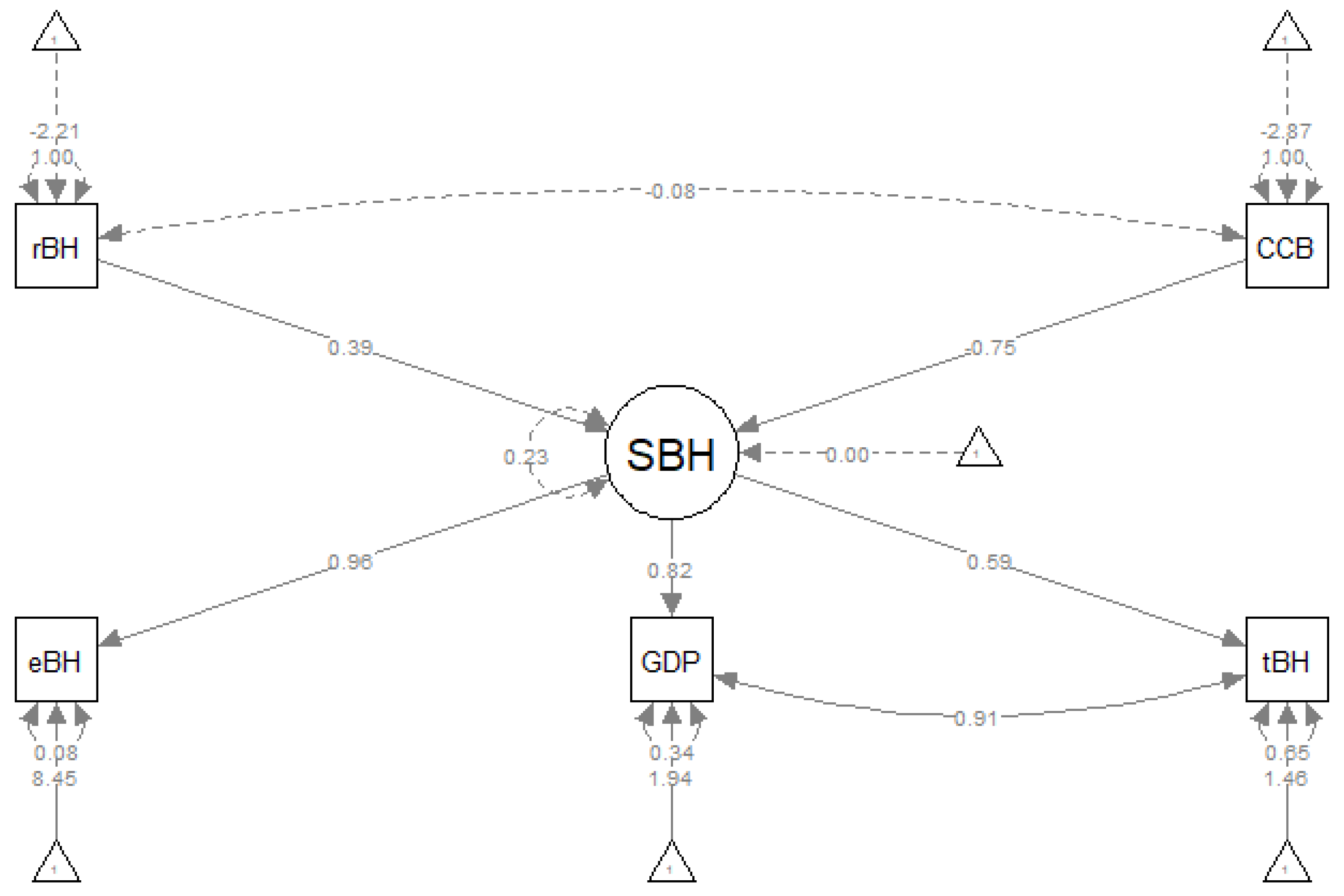

Figure 1 presents a MIMIC model for the estimation of the SE of BiH (SBH). The upper part of the figure represents the causal part of the model, and the lower part represents the measurement part of the model as follows:

Employment rate (emplBH), GDP per capita (GDP_BH), and tax revenues (taxesBH) are widely recognized macroeconomic indicators in shadow economy research, theoretically linked to informality through labor market dynamics, income levels, and tax compliance behavior, as supported by studies such as Schneider and Enste [

1] and Krstić et al. [

5].

Rule of law (ruleBH) and control of corruption (CCB) serve as proxies for institutional quality and are widely recognized in the literature as key determinants of informality since weak institutions often correlate with higher shadow economy activity, as emphasized by Williams and Schneider [

35]. The “rule of government” corresponds to the WGI’s “Rule of Law” index, which captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, including the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts. The “control of corruption” indicator reflects perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption. Both indices are measured on a scale ranging from approximately −2.5 (weak governance performance) to +2.5 (strong governance performance) and are reported annually.

Numerous studies justify the use of a limited number of indicators in MIMIC models, and some—such as Buehn and Schneider [

13]—demonstrate that even just two institutional indicators, like corruption and legal system quality, can effectively capture the dynamics of the shadow economy.

The formal economy is positively linked to the number of salaried workers, with the shadow economy (SE) decreasing as this number grows. However, this relationship does not hold for self-employed individuals, who, especially those running small businesses or family firms, are more likely to evade taxes [

25]. A study involving respondents from 27 EU countries found that formally employed individuals benefit more from the SE and are less inclined to participate in SE activities [

50].

Incorporating the output of the national economy into most macro-econometric models is a common practice. This step is hard to dispute, particularly when the variable of interest is often expressed as a percentage of GDP. In essence, a larger SE is associated with increased activity in the formal economy, assuming all other factors remain constant [

2].

The causes of SE related to taxation can be traced back to the amount and type of tax burden, the effectiveness of tax collection, penalty policies, the complexity of the tax system, and the overall fairness of the system [

26]. The tax system interacts with many factors, but a control variable reflecting the activity and efficiency of tax administration is generally accepted as a standard component in MIMIC model construction, mainly through the channel where the total tax burden may stimulate labor supply in the shadow economy.

The model’s measurement component is based on two elements: the quality of institutions (government rule index) and corruption. These three elements are part of the standard procedure in mainstream literature [

23,

51,

52].

Mainstream literature suggests that money growth should be included in the model as an indicator. Therefore, the larger the SE, the more cash will be used, all other things being equal [

8,

35]. However, in the case of BiH, this does not seem to be a highly important indicator given that the loading is less than 0.3. This is likely related to the fact that BiH has an orthodox currency board. Hanke and Schuler have provided some insights into the mechanism of the currency board regime, and there are some remarks considering the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina as an extreme case in terms of its orthodoxy [

53].

We allowed residual variances of GDP and taxes to be correlated as it is presented in

Figure 1. By doing so, we improved our model (increase in CFI and decrease in RMSEA).

2.2. Data

All data are downloaded from the World Bank database for the period from 1996 to 2022. According to the model specification, data are organized in two parts. Also, imputation of missing data is performed with the mice R package (3.15.0) [

54].

The casual part of the model for B&H assumes the following regressors:

eBH (rate of employment);

GDP (GDP per capita constant USD 2010 in thousands);

txBH (taxes in USD millions).

The measurement part of the model for B&H includes the following indicators:

Descriptive statistics for these variables are presented in

Table 1.

The variables are of second-order integration. The initial time series, even after applying the first difference, confirmed the presence of a unit root according to the Augmented Dickey–Fuller, KPSS, and Box–Ljung tests. However, the unit root test conducted by Pantula, Gonzales-Farias, and Fuller suggested that the variables became stationary after the first difference. The time series variables used in the model were found to be integrated of order two I (2), meaning they required second differencing to achieve stationarity. They applied unit root tests such as the Augmented Dickey–Fuller, KPSS, and Box–Ljung tests and also referenced the Pantula, Gonzales-Farias, and Fuller tests to confirm stationarity after transformation. This transformation was achieved to ensure robustness of the model against critiques related to non-stationary data, which is a common issue in MIMIC model applications. Therefore, we chose to prioritize robustness, which led to the loss of data for the years 1996 and 1997 due to the data transformation process.

3. Results

The results of the causal model estimation are presented in

Table 2.

RMSEA (Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation), a statistic used to assess the goodness-of-fit of the model, is 0.05. The obtained RMSEA value suggests a good fit of the model, and it is extremely better compared to the previous MIMIC studies for BiH [

3]. This problem is consistent in the literature, in which there is a relatively small number of observations [

13]. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is 0.986, and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) is 0.972, which is significantly higher compared to most MIMIC studies. CFI and TLI are important fit indices in SEM literature. In general, the rule of thumb for minimum CFI varies from 0.7 up to 0.95. Recently, there is a consensus in mainstream literature that 0.9 is acceptable [

55,

56]. In this part, many results in the literature based on MIMIC are not performing well.

Every variable incorporated into the measurement part of the model holds substantial statistical significance, as indicated by their near-zero p-values. The interpretation of the employment coefficient’s sign would be simplified if we disregarded the count of self-employed individuals. Consequently, we adjusted the model to include unemployment instead of employment. However, in this configuration, the unemployment variable did not yield a statistically significant coefficient.

4. Discussion

This study contributes to the literature on the shadow economy by applying the MIMIC model to the BiH economic context. BiH is a country marked by a complex post-conflict institutional structure and widespread informality. The findings of this analysis are reflecting its aim to be consistent with institutional theory and tax compliance theory, both of which emphasize the influence of weak governance and high tax burdens on informal economic activity. The results reinforce these theoretical perspectives to a certain extent, demonstrating that institutional quality and corruption control are significant determinants of the size and behavior of the shadow economy in BiH.

The model captures how the informal sector responds to both internal institutional weaknesses and external shocks. On the other hand, results do not offer conventional precision of models that have traditional regression frameworks, although in the context of BiH’s statistics, such precision has huge potential for being significantly misleading.

Structural break analysis conducted using the Bai and Perron methodology [

57,

58], identifies key disruptions in BiH’s economic trajectory, including the post-war recovery period, the delayed impact of the global financial crisis, and the 2014 floods. These events are not some sort of technical statistical anomalies but represent real-world shocks that altered the incentives for informal economic activity. We should mention that similar patterns have been observed in related studies [

3,

13,

59], underscoring the importance of institutional resilience in mitigating the expansion of informality during crises.

The informal sector of an economy is best conceptualized as a responsive subsystem within the broader economic framework. It tends to expand when formal institutions are weak or disrupted and contracts when governance improves and economic stability is restored. This dynamic interplay highlights the need for integrated and adaptive policy responses.

In this study, we utilized time series that required transformation to achieve stationarity. The variables were found to be integrated of order two, I(2), necessitating second differencing to ensure statistical validity. This step, emphasized by Breusch [

19], is critical for maintaining the integrity of MIMIC model estimates. Nevertheless, it is not unusual that some authors avoid this step.

Unlike many studies, this analysis deliberately avoids benchmarking the shadow economy as a percentage of GDP—a practice often criticized for introducing interpretive ambiguity and potential confusion [

45]. Instead, the focus is placed on relative trends, which provide a clearer picture of the shadow economy’s evolution over time.

The latent variable derived from the model does not exhibit a deterministic trend, which aligns with the expectations of Structural Equation Modeling and supports the internal coherence of the results. This further strengthens the robustness of the findings, particularly given the challenges associated with modeling informal economic activity.

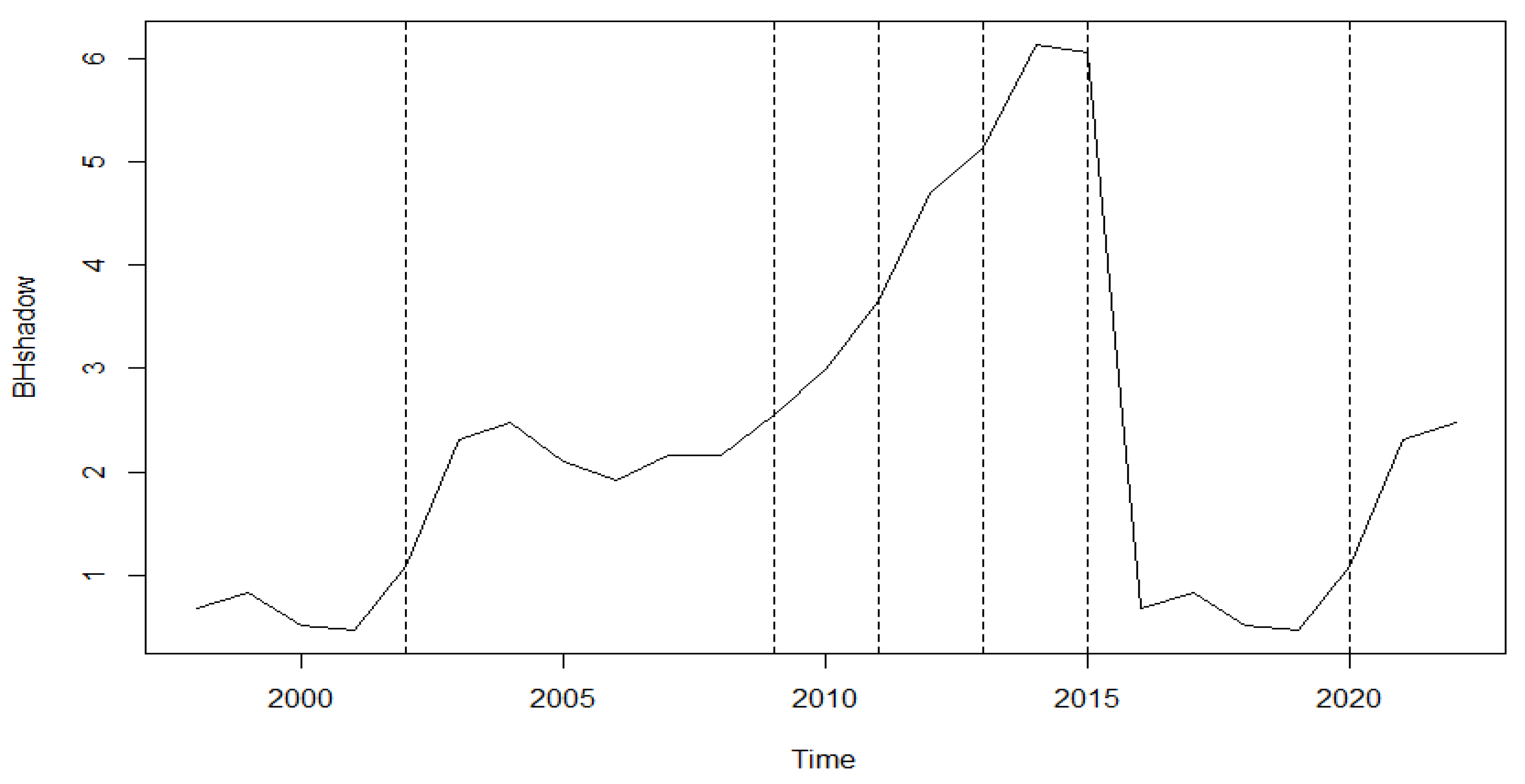

The findings in this paper rely on initial time series that are of integrated order two. This transformation process bolsters the analysis against critiques targeting the causal aspect of the MIMIC model [

46]. Unit root tests revealed that the first differentiation was inadequate for attaining stationarity. The final indicators and regressors incorporated into the model are random walk variables, and these yield the estimated SE as depicted in

Figure 2. Breusch [

19] replicated multiple MIMIC models and highlighted the unit root step as a pivotal stage. This author also scrutinizes the reported transformations and acceptable unit root test outcomes. Therefore, the replication of reported exercises demonstrated in some instances that, despite reported stationarity, this crucial condition does not necessarily hold. We do not have the intention to open discussion in this direction, but it is indicative that the estimation of SE as presented below, which is based on variables I (2), appears to follow a random walk process and does not appear to have some sort of long-term trend. Yet, there are examples when authors report a trend in the SE estimation [

3,

14].

The scores depicted in

Figure 2 are not further transformed by benchmarking, as is common in most MIMIC models. The literature does not provide definitive conclusions about the optimal benchmark variables. The most prevalent approach is to use a multiplication method, expressing a real value as a percentage of GDP [

48]. However, creating point estimates of SE in GDP proportions could lead to misinterpretation, and we chose not to subject our results to potential controversy in this regard.

Some researchers center their discussion on estimated SE around structural changes in the observed national economy [

14]. Other analyses concentrate on a specific structural shock and its impact on SE [

60]. Similar studies have been conducted for BiH [

3]. In our analysis, we refrain from making point estimates of SE in GDP percentages, but we find the result adequate to draw conclusions about the behavior of SE around accurately defined structural breaks. We identify breakpoints according to the method for estimating breaks in time series regression models proposed by Bai, which was later expanded to include multiple breaks [

57,

58].

Estimation of structural brakes is presented with vertical dotted lines on

Figure 2.

Part of the model that tries to identify structural brakes in the BiH’s economy performs solidly. The initial measurement problem in the post-war years is obvious. Then comes the global financial crisis and its postponed effect, considering the position of the BiH system of global financial flows. Further, the model identifies the reaction to catastrophic floods in 2014.

When a catastrophe happens to the network economy, if the official macroeconomy functions as one big network, that unofficial part that is connected to the official, directly and indirectly, is a subnetwork of that network. If we assume that society is a living organism, made of interrelated parts that generate societally endogenous reactions to take care of local failures, then the underground economy is a living organism in cohabitation with the world above the ground, has its inputs, and has its outputs [

59].

5. Conclusions

From a policy perspective, the implications are simple and straightforward, although the nature of SE constrains precisions that could be assumed in the context of conventional macroeconomic aggregates. First, improving institutional quality—particularly in areas related to the rule of law and anti-corruption—can reduce the incentives for informality. Second, simplifying tax regulations and reducing the overall tax burden, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises, may encourage formalization. Third, labor market reforms that promote formal employment opportunities can help absorb workers currently operating outside the legal framework. Additionally, enhancing crisis preparedness and ensuring timely institutional responses during economic shocks are essential to prevent surges in informal activity.

Despite its strengths, the study has several limitations. It relies on secondary data produced in challenging statistical surroundings, which may be subject to measurement errors or inconsistencies, particularly in a fragmented administrative context such as BiH. The country’s statistical infrastructure is complex, with two statistical institutes operating at the entity level and one at the state level. Further, the use of latent variables, while methodologically sound, introduces a degree of abstraction that may obscure some nuances of informal behavior. Furthermore, the model does not account for all external influences, such as remittances, cross-border trade, or regional spillovers. Future research could expand the model to include these factors and explore cross-entity comparisons within BiH, although this could assume a complex econometric toolset (e.g., a Dynamic Stochastic Growth Equilibrium model) and a fully developed national account statistical framework at the state level. The fact that there are no input–output tables for BiH speaks for itself.

Nevertheless, this study aims to offer a relatively robust and accessible framework for understanding the drivers and dynamics of the shadow economy in BiH. Attempting to link empirical findings to theoretical insights and highlighting actionable policy recommendations is a challenging task, but in summary, this analysis provides a solid foundation for informed decision-making aimed at managing informality and strengthening economic governance.

To have a latent variable (SE estimated by the MIMIC model is a latent variable) that shows a long-term trend in estimated behavior, with the variables that are directly measured and included in the model without a trend, could be strange knowing SEM mechanics. A latent variable reflects what is inherent in the movements of those variables that are directly measured and have their relations imposed by the model. As we know, the most common cause of violation of stationarity is a trend in the mean, and it is strange that latent variables that are indirectly measured according to directly measured stationary variables appear to have deterministic trends. Breusch reveals that in some studies, results are wrongly reported in this context, or reported transformations are simply not performed correctly [

19]. Therefore, this characteristic of our result is meaningful, and our result is robust against criticism in this rather technical context.

In the context of MIMIC models used for measuring the shadow economy, benchmarking is a common practice. Although this technique can provide useful insights, it is crucial to interpret the results carefully to avoid potential disputes. There is widespread skepticism in the literature regarding this topic. Therefore, the decision to avoid such estimates adds another pillar to the overall robustness of our results.

What happens with the underground economy is conditioned by several factors, with one being the intensity of the disaster. If there is a long-run disruptive activity, it could be expected to register a rise in the shadow economy, and we did catch a spike in 2014, but afterwards there was a huge downturn. This appears to be a puzzle that is most probably a result of measurement errors in national statistics.

Finally, we are aware of certain limitations of this study. However, this model is used in different scientific fields where some problems that are immanent to the economic problems (e.g., measurement problem) could be managed more efficiently. Nevertheless, in those fields we also have a situation where the mainstream literature often does not give a lot of attention to all the steps proposed by the SEM procedure that is inside the MIMIC mode [

61].