Unveiling Challenges to Management Control Systems in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

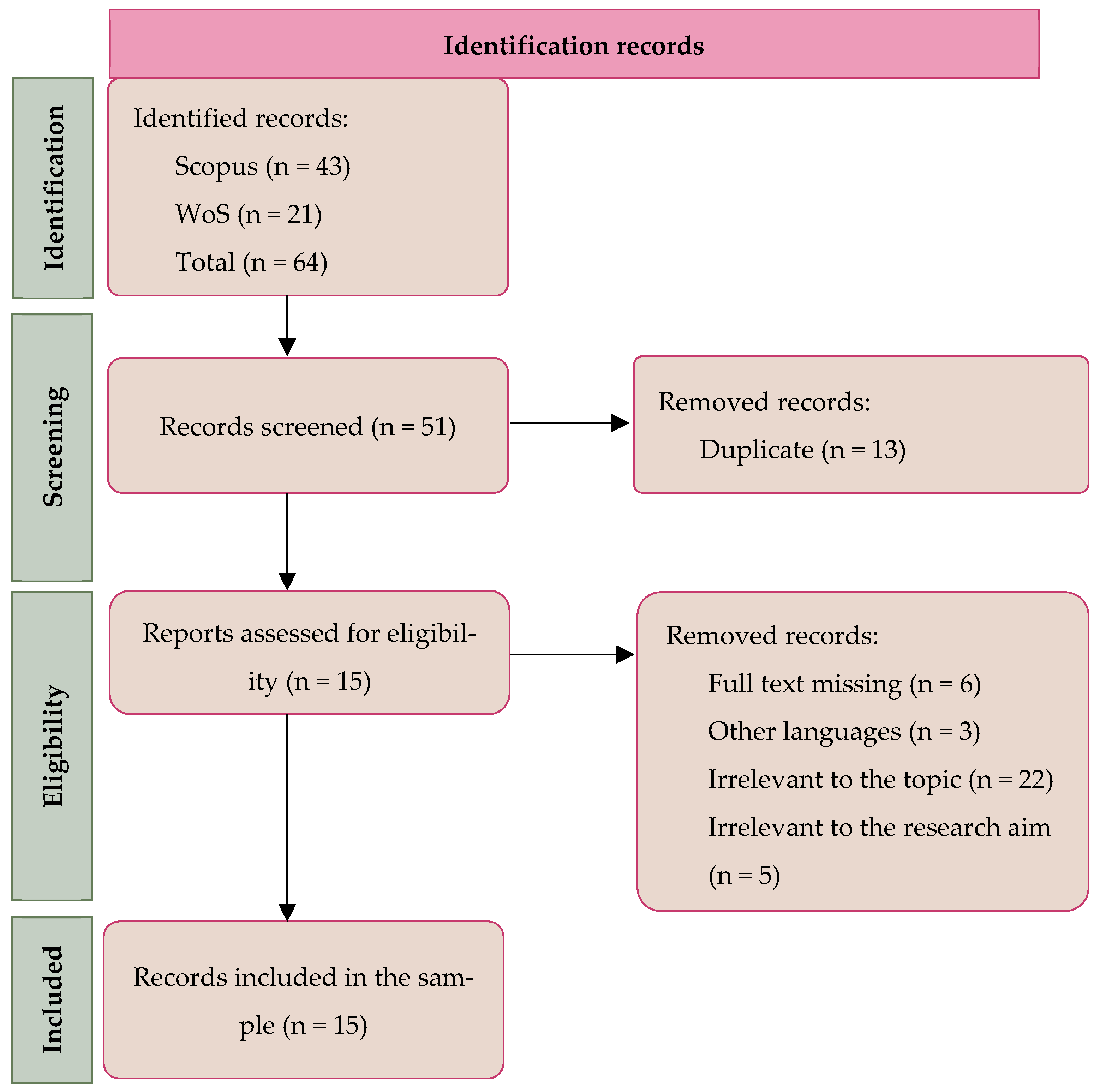

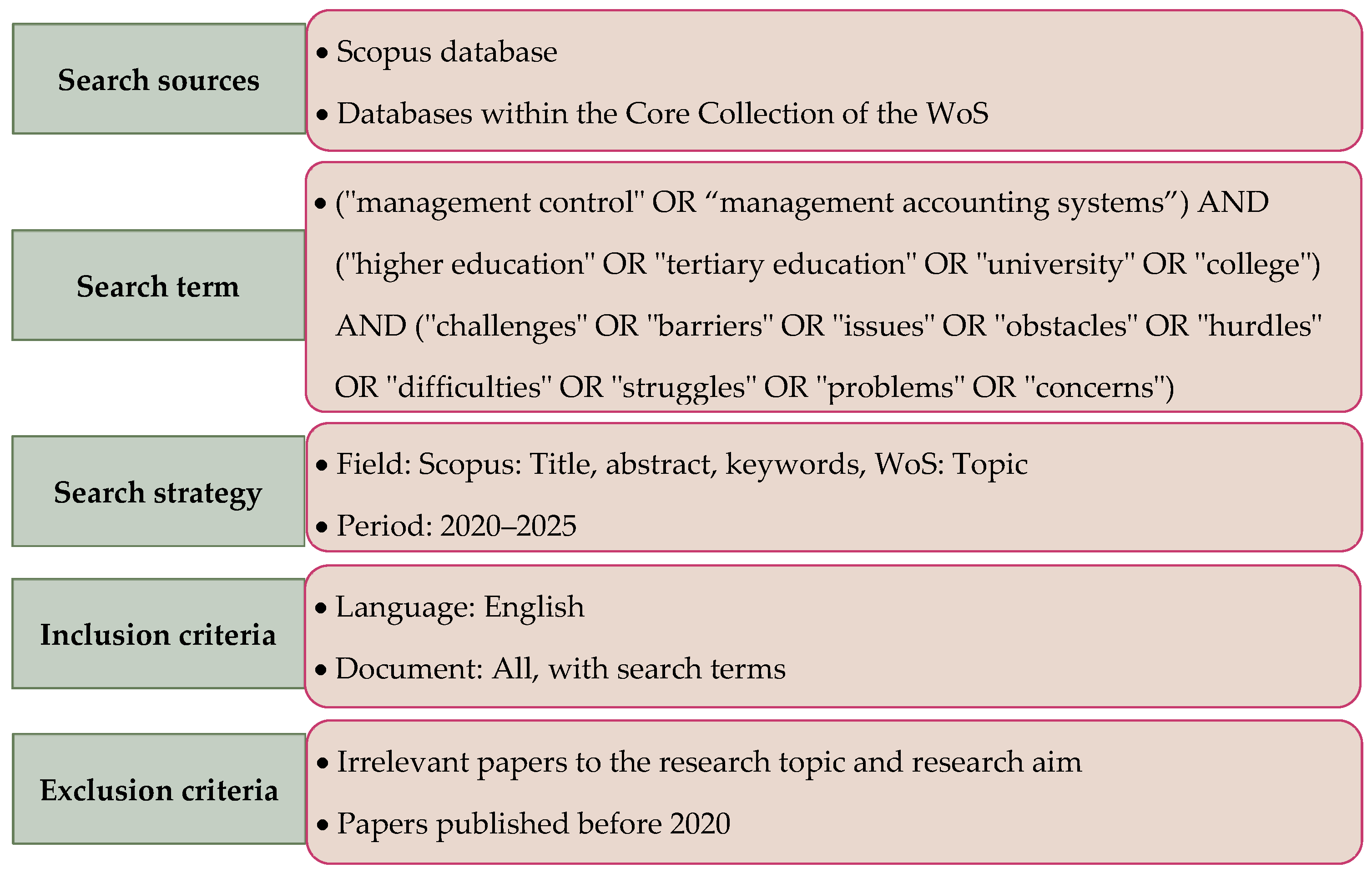

2. Methods and Data

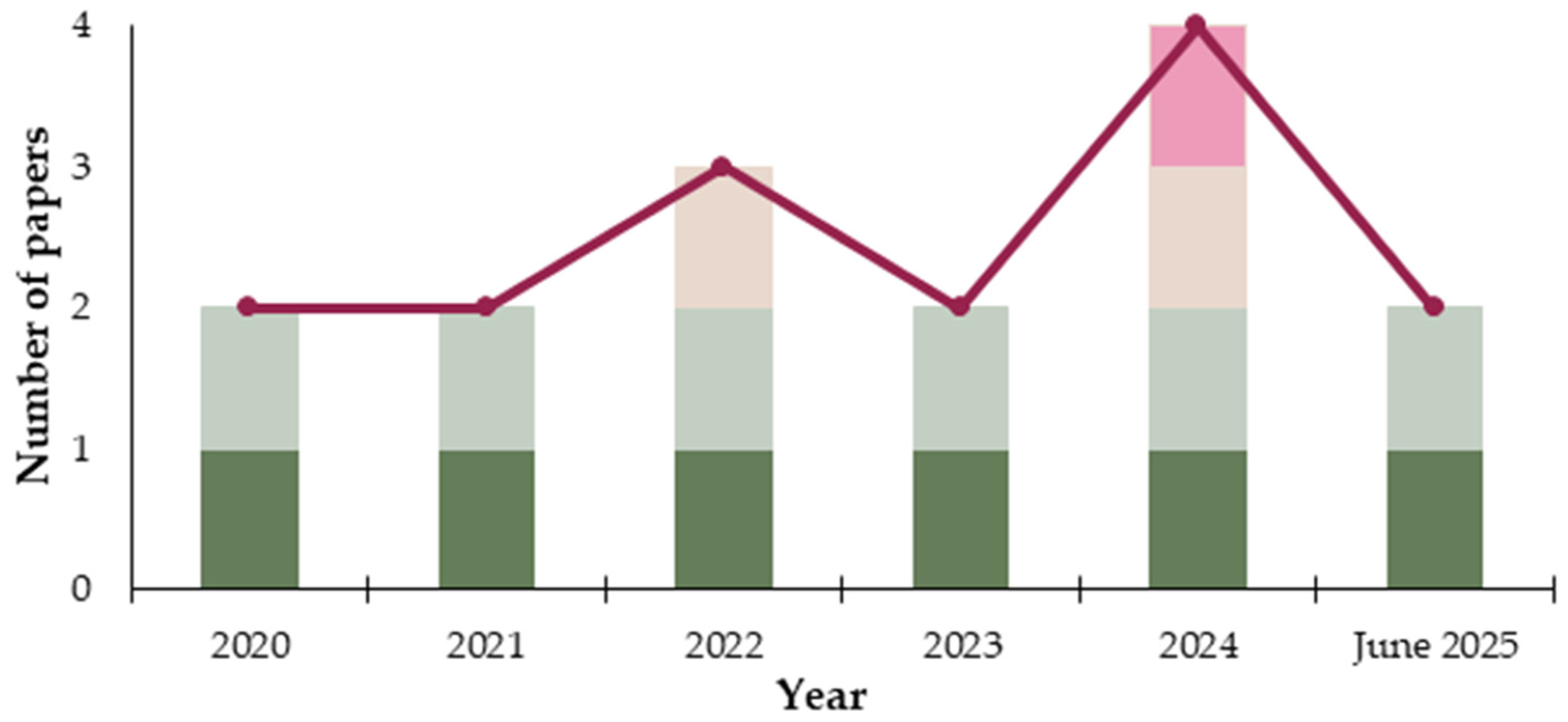

3. Results

| Source | Authors | Year | Country Under Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| [53] | Anyim, Dr. W.O. | 2020 | Nigeria |

| [54] | Aryawati, N.P.A.; Triyuwono, I.; Roekhudin, R.; Mardiati, E. | 2024 | Undefined |

| [55] | Chalmeta, R.; Estevez, M.F. | 2023 | Spain |

| [56] | De Villiers, C.; Dimes, R.; Molinari, M. | 2024 | UK |

| [57] | Dudycz, H.; Hernes, M.; Kes, Z.; Mercier-Laurent, E.; Nita, B.; Nowosielski, K.; Oleksyk, P.; Owoc, M.L.; Palak, R.; Pondel, M.; Wojtkiewicz, K. | 2021 | Poland |

| [58] | Frei, J.; Greiling, D.; Schmidthuber, J. | 2023 | Austria |

| [59] | Khalaf, M.H.R.; Azim, Z.M.A.; Elkhateeb, W.H.A.H.; Shahin, O.R.; Taloba, A.I. | 2022 | Undefined |

| [60] | Khudhair, A.H.; Daud, Z.M.; Mustafa, H.A.R.; Al-Zubaidi, A.N.J. | 2025 | Iraq |

| [61] | Liying, H.; Mengying, Z. | 2024 | China |

| [62] | Ma, Y.; Dai, B.; Ding, B. | 2022 | China |

| [63] | Rigby, J.; Kobussen, G.; Kalagnanam, S.; Cannon, R. | 2021 | Canada |

| [64] | Rosalina, K.; Jusoh, R. | 2024 | Indonesia |

| [65] | Rosalina, K.; Jusoh, R. | 2025 | Indonesia |

| [66] | Susilawati, W.; Alamanda, D.T.; Ramdani, R.M.; Adi Prabowo, F.S.; Ramdhani, A. | 2020 | Indonesia |

| [67] | Vale, J.; Amaral, J.; Abrantes, L.; Leal, C.; Silva, R. | 2022 | Undefined |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCSs | Management control systems |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| HEIs | Higher education institutions |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ST | Subgroup total |

| ICS | Information and communication system |

| ERP | Enterprise resource planning |

References

- Xiao, J.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, A.; Wang, X.; Skare, M. Overcoming barriers and seizing opportunities in the innovative adoption of next-generation digital technologies. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dub, A.; Aleksandrova, M.; Mykhaylyova, K.; Niemtsev, A. The impact of innovations and technological development on modern society and global dynamics. Econ. Aff. 2023, 68, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimcheva, G.; Stoyanov, I. Challenges to the Application and Decision-Making Using Artificial Intelligence (AI): Analysis of the Attitudes of Managers in Bulgarian Service Companies. In Proceedings of the CIEES 2023—IEEE International Conference on Communications Information, Electronic and Energy Systems, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 23–25 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Sánchez, J.M.; Molina-Gómez, J.; Mercadé-Melé, P.; Almadana-Abón, S. Boosting competitiveness through the alignment of corporate social responsibility, strategic management and compensation systems in technology companies: A case study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.F.; Rodgers, W. Competition, competitiveness, and competitive advantage in higher education institutions: A systematic literature review. Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 49, 2153–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarenko, E.N.; Chernysheva, Y.G.; Polyakova, I.A.; Kislaya, I.A.; Makarenko, T.V. Capabilities of business analysis in developing data-driven decision solutions. In Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhelev, Z.; Kostova, S. Investigating the application of digital tools for information management in financial control: Evidence from Bulgaria. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, K.; Hmioui, A. Big Data and Management Control in Tourist Destinations. In Digital Technologies and Applications; ICDTA 2024, Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Motahhir, S., Bossoufi, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.X.; Hou, Z.S. Notes on data-driven system approaches. Zidonghua Xuebao/Acta Autom. Sin. 2009, 35, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerer, I. Universities act differently: Identification of organizational effectiveness criteria for faculties. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2019, 25, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyadjieva, P. Diversity matters: A lesson from a post-communist country. In Towards a Multiversity? Universities Between Global Trends and National Traditions; Krücken, G., Kosmützky, A., Torka, M., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2006; pp. 108–131. ISBN 9783899424683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsieli, M.; Mutula, S. COVID-19 and Digital transformation in higher education institutions: Towards inclusive and equitable access to quality education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Mohd Noor, A.S.; Alwan, A.A.; Gulzar, Y.; Khan, W.Z.; Reegu, F.A. ELearning Acceptance and Adoption Challenges in Higher Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, I.; Verbytska, A.; Novomlynets, O.; Stepenko, S.; Dyvnych, H. Analysis of online learning issues within the higher education quality assurance frame: ‘Pandemic lessons’ to address the hard time challenges. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadé, R.G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Guan, H. Challenges and opportunities in the internet of intelligence of things in higher education—Towards bridging theory and practice. IOT 2023, 4, 430–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkanjanapiban, P.; Silwattananusarn, T. A performance-driven exploration of combining topic modeling and machine learning for online learning data analysis. TEM J. 2025, 14, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalova-Karakasheva, M.; Zgureva-Filipova, D.; Filipov, K.; Venkov, G. Ensuring sustainability: Leadership approach model for tackling procurement challenges in Bulgarian higher education institutions. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, A.; Daniel, B.K. A decade of research into the application of big data and analytics in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 5807–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, G.; Yankova, T.; Klisarova-Belcheva, S.; Ivanova, S. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ learning. Information 2021, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, A.; Liu, Q.; Kong, S.; Wang, H. A survey on big data-enabled innovative online education systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Paek, S.; Park, S.; Park, J. A news big data analysis of issues in higher education in Korea amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, F.; Ma, J.; Zhou, L.; Cao, J. Countermeasures for the impact of higher education management in the context of big data. RISTI—Rev. Iber. Sist. E Tecnol. Inf. 2024, 2024, 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, X.; Shujiang, Y.; Nan, P.; Chenxu, D.; Dan, L. Review on a big data-based innovative knowledge teaching evaluation system in universities. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Sharma, U. Commodification of education and academic labour—Using the balanced scorecard in a university setting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2002, 13, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonova, E.; Raitskaya, L. An overview of trends and challenges in higher education on the worldwide research agenda. J. Lang. Educ. 2018, 4, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.I.; Sarrico, C.S.; Radnor, Z. The influence of performance management systems on key actors in universities, The Case of an English university. Public Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedmo, T.; Sahlin-Andersson, K.; Wedlin, L. Is a global organizational field of higher education emerging? Management education as an early example. In Towards a Multiversity? Universities Between Global Trends and National Traditions; Krücken, G., Kosmützky, A., Torka, M., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2006; pp. 154–175. ISBN 9783899424683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakkuri, J.; Johanson, J.E. Failed promises—Performance measurement ambiguities in hybrid universities. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2020, 17, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Frankenberger, F.; Akib, N.A.M.; Sen, S.K.; Sivapalan, S.; Novo-Corti, I.; Venkatesan, M.; Emblen-Perry, K. Governance and Sustainable Development at Higher Education Institutions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 6002–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R. Being a University; Routledge Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781136906015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisens, H.C.; Enders, J. State models, policy networks, and higher education policy. Policy change and stability in Dutch and English higher education. In Towards a Multiversity? Universities Between Global Trends and National Traditions; Krücken, G., Kosmützky, A., Torka, M., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2006; pp. 87–107. ISBN 9783899424683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehm, B.M. Doctoral education in Europe: New structures and models. In Towards a Multiversity? Universities Between Global Trends and National Traditions; Krücken, G., Kosmützky, A., Torka, M., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2006; pp. 132–153. ISBN 9783899424683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, P.; Mohammad, R.F.; Siddiqui, S.; Noor, S.; Hussain, A. sustainability in higher education institutions in Pakistan: A systematic review of progress and challenges. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaftandzhieva, S.; Hussain, S.; Hilčenko, S.; Doneva, R.; Boykova, K. Data-driven decision making in higher education institutions: State-of-Play. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raitskaya, L.K.; Lambovska, M.R. Prospects for ChatGPT application in higher education: A scoping review of international research. Integr. Educ. 2024, 28, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q. Data-driven research on higher education management and decision-making techniques and their applications. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Bangalore, India, 20–21 October 2023; Volume 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombashov, R. Criteria for Management Control of Forest Sector Enterprises. In Proceedings of the WoodEMA 2024—Green Deal Initiatives, Sustainable Management, Market Demands, and New Production Perspectives in the Forestry-Based Sector, Sofia, Bulgaria, 15–17 May 2024; pp. 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Abernethy, M.A.; Chua, W.F. A field study of control system “Redesign”: The impact of institutional processes on strategic choice. Contemp. Account. Res. 1996, 13, 569–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedyalkova, P. Concepts of the nature and development of control. In Recent Developments in Financial Management and Economics; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R.H. Management control systems design within its organizational context: Findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Account. Organ. Soc. 2003, 28, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, R.H.; Noreen, E.W.; Brewer, P.C. Managerial Accounting; McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, K.A.; Otley, D.T. A Review of the literature on control and accountability. In Handbook of Management Accounting Research; Chapman, C.S., Hopwood, A.G., Shields, M.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 2, pp. 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, K.; Van der Stede, W. Management Control Systems: Performance Measurement, Evaluation and Incentives; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, T.W.; Schmidt, U. Adoption and use of management controls in higher education institutions. In Incentives and Performance: Governance of Research Organizations; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alastal, A.Y.M.; Jamil, C.Z.M.; Abd-Mutalib, H. Management control system: A literature review. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 470, pp. 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica/Pan Am. J. Public Health 2022, 46, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambovska, M.R.; Raitskaya, L.K. High-quality publications in Russia: A literature review on how to influence university researchers. Integr. Educ. 2022, 26, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, Ü.; Salahuddin, T. Technological and innovative structure and capabilities of Türkiye’s automotive industrial sector: An exploratory study. Int. J. Automot. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, E.; Zsido, K.E.; Fenyves, V. Cluster analysis with K-mean versus K-medoid in financial performance evaluation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.; Sharma, M. A review of K-Mean algorithm. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2013, 4, 2972–2976. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, P. Image segmentation method based on K-mean algorithm. Eurasip J. Image Video Process 2018, 2018, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjundan, S.; Sankaran, S.; Arjun, C.R.; Anand, G.P. Identifying the number of clusters for K-means: A hypersphere density based approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.00643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyim, D.W.O. A literature review of management control system in university libraries. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2020, 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Aryawati, N.P.A.; Triyuwono, I.; Roekhudin, R.; Mardiati, E. Bibliometric analysis on Scopus database related internal control in university: A Mapping Landscape. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2422566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmeta, R.; Ferrer Estevez, M. Developing a business intelligence tool for sustainability management. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; Dimes, R.; Molinari, M. Determinants, mechanisms and consequences of UN SDGs reporting by universities: Conceptual framework and avenues for future research. J. Public Budgeting Account. Financ. Manag. 2024, 37, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudycz, H.; Hernes, M.; Kes, Z.; Mercier-Laurent, E.; Nita, B.; Nowosielski, K.; Oleksyk, P.; Owoc, M.L.; Palak, R.; Pondel, M.; et al. A Conceptual Framework of Intelligent Management Control System for Higher Education. In Proceedings of the IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, Online, 12–13 May 2021; Mercier-Laurent, E., Owoc, M.L., Özgür Kayalica, M., Eds.; Springer: Wrocław, Poland, 2021; Volume 614, pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, J.; Greiling, D.; Schmidthuber, J. Reconciling field-level logics and management control practices in research management at Austrian public universities. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2023, 20, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, M.H.R.; Azim, Z.M.A.; Elkhateeb, W.H.A.H.; Shahin, O.R.; Taloba, A.I. Explore the e-learning management system lower usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2022, 11, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudhair, A.H.; Daud, Z.M.; Mustafa, H.A.R.; Al-Zubaidi, A.N.J. Facilitators and leadership styles: Theoretical drivers for performance budgeting adoption in Iraq’s higher education sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2437140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liying, H.; Mengying, Z. How political influence and financial pressure contribute to performance-based budgeting and university performance: Evidence from SEM and NCA. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, B.; Ding, B. University archives autonomous management control system under the internet of things and deep learning professional certification. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4854213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigby, J.; Kobussen, G.; Kalagnanam, S.; Cannon, R. Implementing responsibility centre management in a higher educational institution. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2021, 70, 2374–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, K.; Jusoh, R. Levers of control, counterproductive work behavior, and work performance: Evidence from Indonesian higher education institutions. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, K.; Jusoh, R. The enabling control systems and work performance in higher education: The role of intrinsic motivation in overcoming task difficulty. Cogent Educ. 2025, 12, 2487597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilawati, W.; Alamanda, D.T.; Ramdani, R.M.; Prabowo, F.S.A.; Ramdhani, A. Develop human integrity and quality through lecturing management control systems. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 2459–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, J.; Amaral, J.; Abrantes, L.; Leal, C.; Silva, R. Management accounting and control in higher education institutions: A systematic literature review. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S. National education policy 2020: A synergy and a sociology. In New Education Policy, Sustainable Development and Nation Building: Perspectives, Issues and Challenges; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2025; pp. 43–56. ISBN 9781040365960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, C.; Kuttner, M.; Duller, C.; Sommerauer, P. Does national culture impact management control systems? A systematic literature review. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 209–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, A.A.; de Boer, F.A. Project management control within a multicultural setting. J. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 10, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.R. Leading and integrating national cultures into an organizational culture. In Public Leadership; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 99–104. ISBN 9781617616242. [Google Scholar]

- Hardman, F.; Sandi, A.M. School improvement in rural settings: A review of international research and practice. In Springer Briefs in Education; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume F3393, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Screwvala, R.; Kompalli, P. Ed-Tech revolution post COVID-19. In The Routledge Handbook of Global and Digital Governance Crossroads: Stakeholder Engagement and Democratization; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2024; pp. 204–219. ISBN 9781032160870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sources * | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Challenges | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | ST ** |

| GROWTH THREATS | ||||||||||||||||

| Global Threats | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Strategy uncertainty | • | |||||||||||||||

| Lack of Technology Training | 7 | |||||||||||||||

| Absence of implementation methodologies | • | |||||||||||||||

| Inadequate staff training | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Lack of an ICS *** culture | • | |||||||||||||||

| Need for a training team | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Threats Regarding Control Criteria | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Need for standardisation | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Technological Integration | 7 | |||||||||||||||

| Automated system errors | • | |||||||||||||||

| Inadequate infrastructure | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Inappropriate timing for implementation | • | |||||||||||||||

| Lack of necessary equipment | • | |||||||||||||||

| Shortage of experienced IT personnel | • | |||||||||||||||

| GROUP TOTAL | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| LIMITATIONS (regarding) | ||||||||||||||||

| Data Gathering | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Data collection problems | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Need for data availability | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Funding | 5 | |||||||||||||||

| Financial pressure on the budget | • | |||||||||||||||

| High costs | • | |||||||||||||||

| Inadequate funding | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| HR Problems | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| Counterproductive work behaviour | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Dissatisfaction with psychological needs | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Human errors | • | |||||||||||||||

| Increased work stress/scepticism | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Lack of human ingenuity | • | |||||||||||||||

| Potential/unintended human errors | • | |||||||||||||||

| Staff incompetence | • | |||||||||||||||

| Work overload | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Organisational Constraints | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Alteration in the ERP **** | • | |||||||||||||||

| Competing priorities | • | |||||||||||||||

| Ineffective communication system | • | |||||||||||||||

| Lack of capacity | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Poor remuneration system | • | |||||||||||||||

| Poor working conditions | • | |||||||||||||||

| Short analysis periods | • | |||||||||||||||

| Staff competencies | • | |||||||||||||||

| GROUP TOTAL | 8 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |||

| MALPRACTICES | ||||||||||||||||

| HR Resistance | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Eroding performance quality | • | |||||||||||||||

| Resistance to reforms | • | |||||||||||||||

| Staff collusion | • | |||||||||||||||

| Undesirable employee behaviours | • | |||||||||||||||

| Management Engagement | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Abuse of authority | • | |||||||||||||||

| Abuse of responsibilities | • | |||||||||||||||

| Diminishing employees’ autonomy | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Fraud | • | |||||||||||||||

| Lack of coordination | • | |||||||||||||||

| Lack of management support | • | |||||||||||||||

| Need to introduce a MCS evaluation team | • | |||||||||||||||

| Overriding established controls | • | |||||||||||||||

| GROUP TOTAL | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| STAKEHOLDER ISSUES | ||||||||||||||||

| Stakeholder Issues Behaviour | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Issues with implementing controls due to stakeholders’ perceptions | • | |||||||||||||||

| Other Stakeholder Issues | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Challenges in balancing multiple stakeholders’ information | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Need for a system to identify stakeholders’ interests | • | |||||||||||||||

| Political influence | • | |||||||||||||||

| GROUP TOTAL | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| TOTAL FOR ALL GROUPS | 18 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lambovska, M.; Angelova-Stanimirova, A. Unveiling Challenges to Management Control Systems in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. World 2025, 6, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030100

Lambovska M, Angelova-Stanimirova A. Unveiling Challenges to Management Control Systems in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. World. 2025; 6(3):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030100

Chicago/Turabian StyleLambovska, Maya, and Antoaneta Angelova-Stanimirova. 2025. "Unveiling Challenges to Management Control Systems in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review" World 6, no. 3: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030100

APA StyleLambovska, M., & Angelova-Stanimirova, A. (2025). Unveiling Challenges to Management Control Systems in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. World, 6(3), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030100