Path Optimization for Aircraft Based on Geographic Information Systems and Deep Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The application of deep learning (DNN) methodology to analyze and optimize aircraft or UAV trajectory deviations that are tailored for low-altitude operations;

- Simulation of real experimental flight data for practical and high-impact evaluation to validate the robustness of the proposed navigation framework;

- The targeting of sustainable aviation through fuel-efficient route planning for agricultural purposes;

- Establishment of a transferable navigation framework that can be adapted and scaled for future use in agricultural UAVs operating in complex field environments.

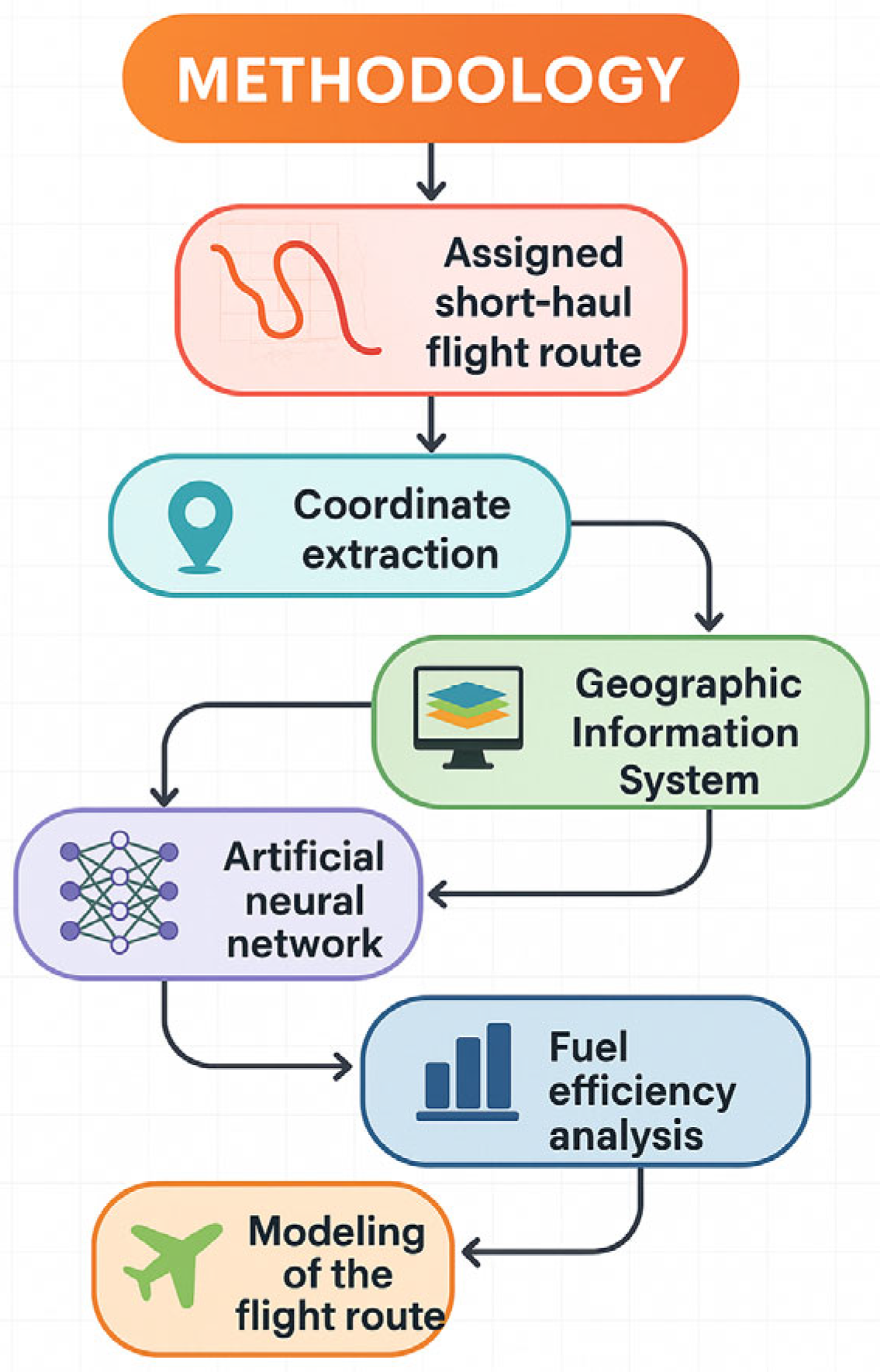

2. Methodology

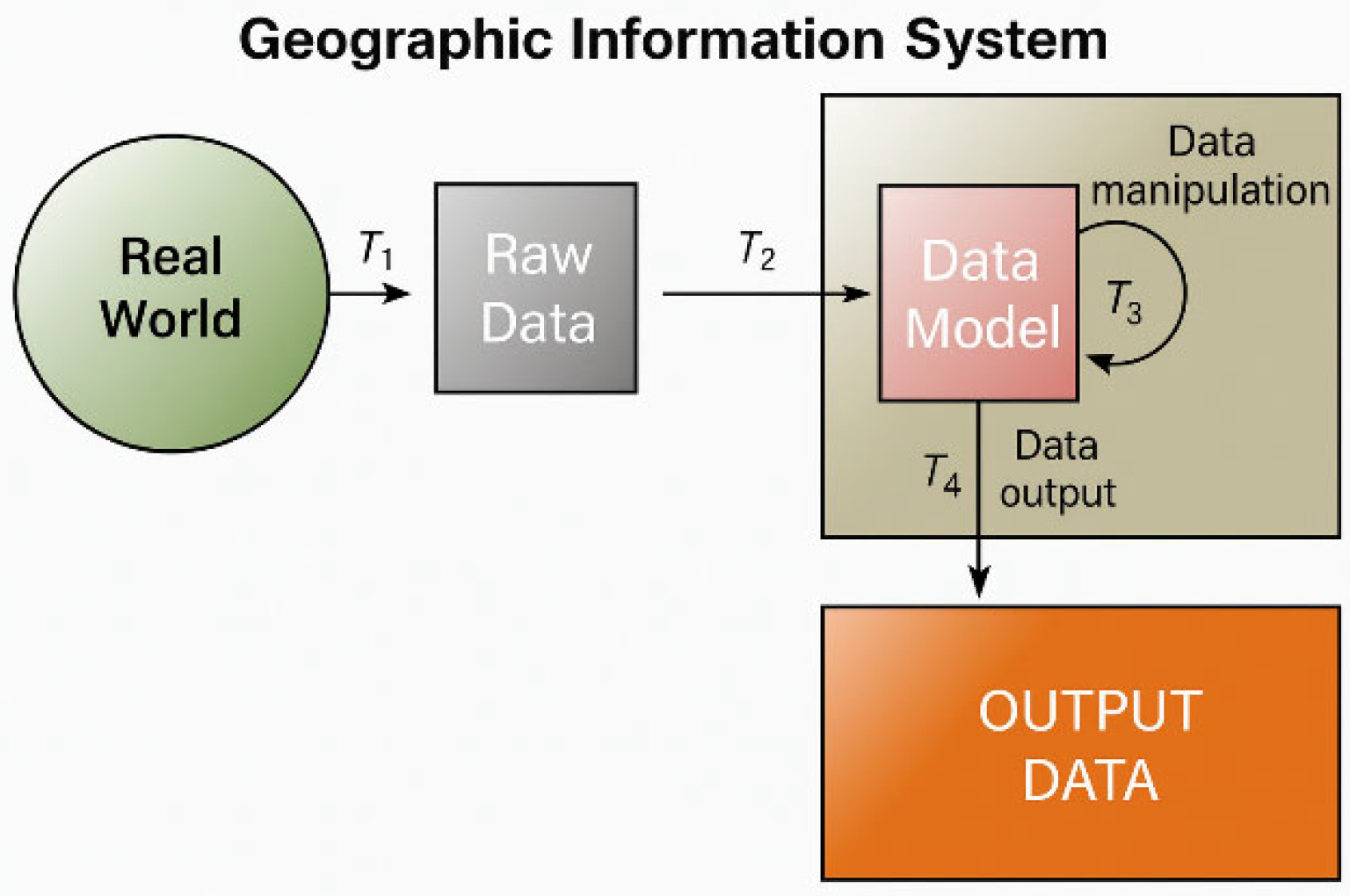

2.1. Geographic Information System (GIS)

2.2. GIS Software

2.3. Mathematical Modeling

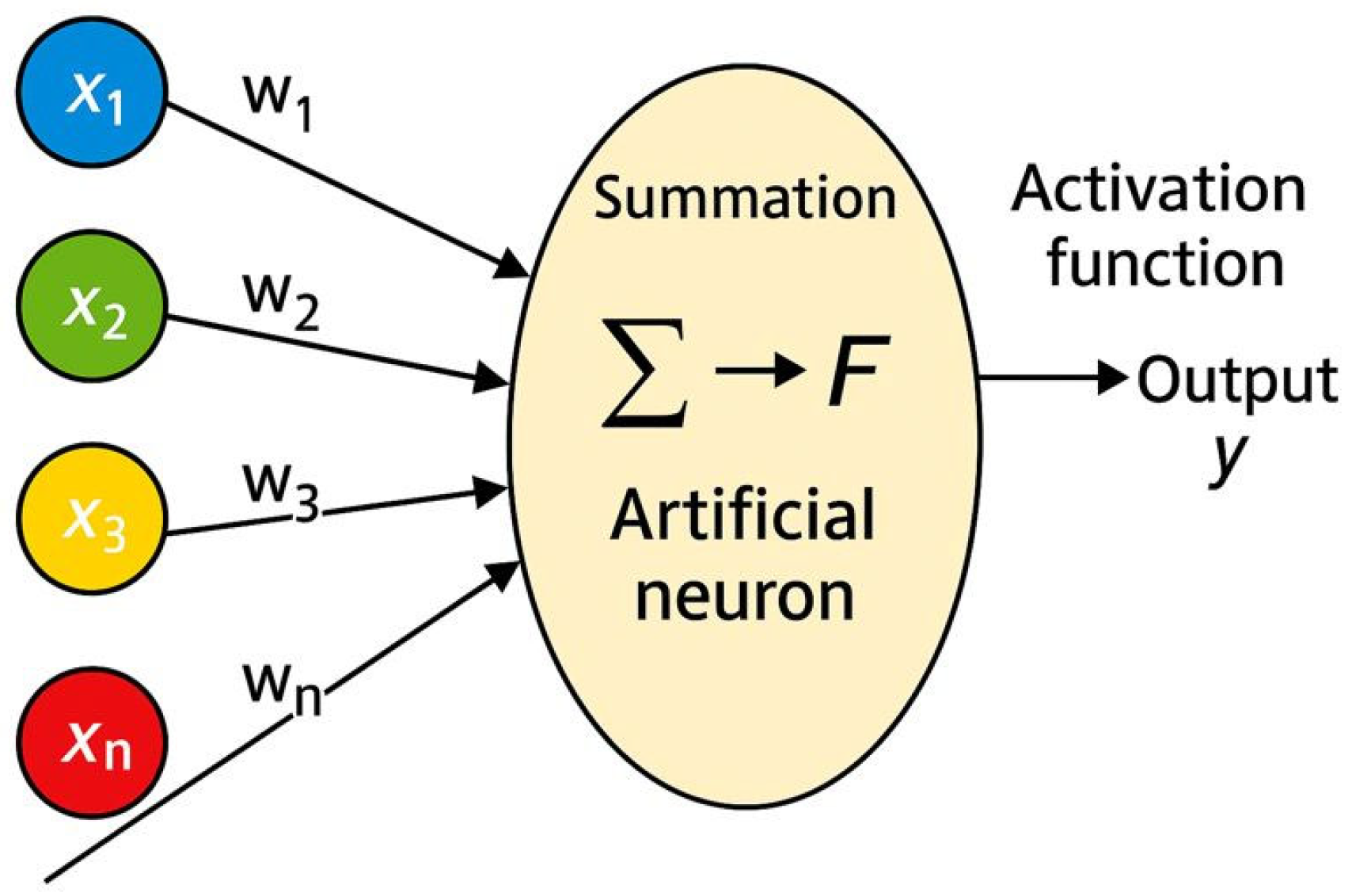

2.4. Deep Neural Network (DNN)

- y—the value of the output signal;

- F—the activation function;

- n—the number of input features;

- b—the bias term;

- —the value of the input signal number i;

- —the weight value of the connection number i.

3. Experimental Case Study

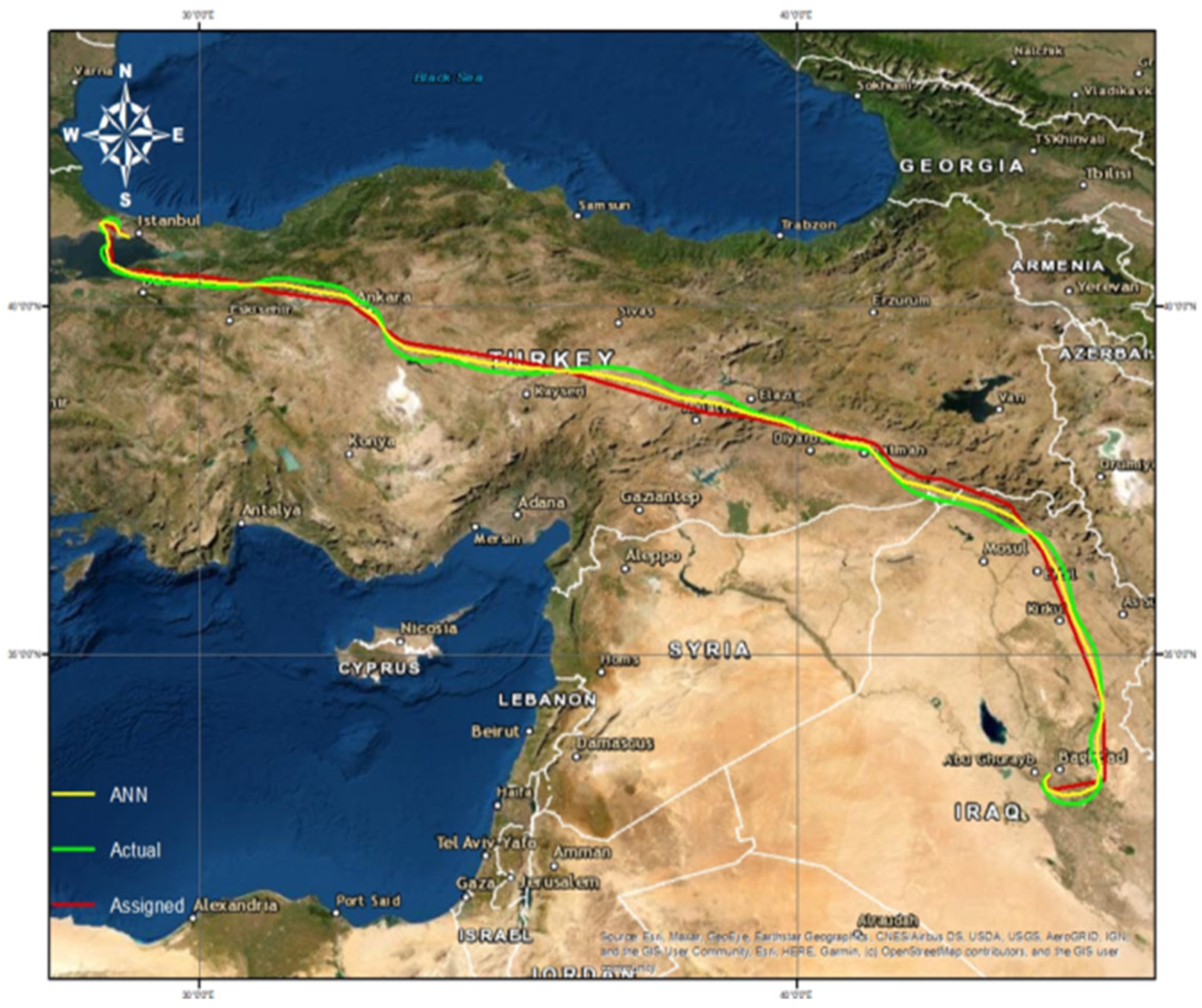

- Itinerary assigned: The flight path has been determined. It is a virtual line for the aircraft, and it is in the form of a straight line. Using the GIS system, the coordinates of the virtual flight path can be found;

- Itinerary actual: This is the actual flight line taken by the plane, and the coordinates can be found using the GIS system;

- Itinerary-based DNN: This is a DNN-based flight path. This line and its coordinates are obtained as a result of programming and simulating the assigned line and the actual line coordinates after modeling and simulating the data by ANN. In this research, short-haul flights will be discussed and a real round-trip flight between Baghdad and Istanbul and its international line (assigned line) analyzed.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Methodology Results

4.2. Agricultural UAV Applicability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jaber, A.A.; Al-Haddad, L.A. Integration of Discrete Wavelet and Fast Fourier Transforms for Quadcopter Fault Diagnosis. Exp. Tech. 2024, 48, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A. Applications of Machine Learning Techniques for Fault Diagnosis of UAVs. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Brunek, Italy, 23 July 2022; Volume 3360, pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Giernacki, W.; Khan, Z.H.; Ali, K.M.; Tawafik, M.A.; Humaidi, A.J. Quadcopter Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Structural Design Using an Integrated Approach of Topology Optimization and Additive Manufacturing. Designs 2024, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quamar, M.M.; Al-Ramadan, B.; Khan, K.; Shafiullah, M.; El Ferik, S. Advancements and Applications of Drone-Integrated Geographic Information System Technology—A Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Graziano, A.; Ragusa, E.; Guarrera, G. Integration of Building Information Modeling and Geographic Information Systems for Efficient Airport Construction Management. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryaprağı Gülalan, S.; Ernst, F.B.; Karabulut, A.İ. Future Modeling of Urban Growth Using Geographical Information Systems and SLEUTH Method: The Case of Sanliurfa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, N.M.; Jassim, A.H.; Abulqasim, S.A.; Basem, A.; Ogaili, A.A.F.; Al-Haddad, L.A. Leak Detection and Localization in Water Distribution Systems Using Advanced Feature Analysis and an Artificial Neural Network. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Majdi, H.S.; Holovatyy, A.; Jaber, A.A.; Al-Karkhi, M.I.; Giernacki, W. Energy Consumption and Efficiency Degradation Predictive Analysis in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Batteries Using Deep Neural Networks. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoob, A.; Gokool, S.; Clulow, A.; Mahomed, M.; Mabhaudhi, T. Leveraging Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Technologies to Facilitate Precision Water Management in Smallholder Farms: A Scoping Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Drones 2024, 8, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masemola, R.; Sibanda, M.; Mutanga, O.; Kunz, R.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Mabhaudhi, T. Assessing the Potential of Drone Remotely Sensed Data in Detecting the Soil Moisture Content and Taro Leaf Chlorophyll Content Across Different Phenological Stages. Water 2025, 17, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yan, S.; Janicke, H.; Mahboubi, A.; Bui, H.T.; Aboutorab, H.; Bewong, M.; Islam, R. A Survey on Unauthorized UAV Threats to Smart Farming. Drones 2025, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Sharma, S.K. Evolving Base for the Fuel Consumption Optimization in Indian Air Transport: Application of Structural Equation Modeling. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2014, 6, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Sharma, S.K. Fuel Consumption Optimization in Air Transport: A Review, Classification, Critique, Simple Meta-Analysis, and Future Research Implications. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2015, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; He, P.; Ma, C.; Niu, C.; Gao, H.; Wang, H.; Muyeen, S.M.; Zhou, D. A Novel Path Planning Approach for Plant Protection UAV Based on DDPG and ILA Optimization Algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 111006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullayeva, F.; Valikhanli, O. Multimodal Deep Neural Network for UAV GPS Jamming Attack Detection. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Deng, C.; Guerrieri, A. Low-AoI Data Collection in Integrated UAV-UGV-Assisted IoT Systems Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Comput. Netw. 2025, 259, 111044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodu, O.A.; Althumali, H.; Mohd Hanapi, Z.; Jarray, C.; Raja Mahmood, R.A.; Adam, M.S.; Bukar, U.A.; Abdullah, N.F.; Luong, N.C. A Comprehensive Survey of Deep Reinforcement Learning in UAV-Assisted IoT Data Collection. Veh. Commun. 2025, 55, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Bian, L.; Zhou, L.; Tian, Q.; Ge, Y. AI-Powered UAV Remote Sensing for Drought Stress Phenotyping: Automated Chlorophyll Estimation in Individual Plants Using Deep Learning and Instance Segmentation. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2026, 299, 130141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Nagesh, D.S. A Review of Deep Learning Applications in Weed Detection: UAV and Robotic Approaches for Precision Agriculture. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzargyros, G.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Kotoula, V.; Stimoniaris, D.; Tsiamitros, D. UAV Inspections of Power Transmission Networks with AI Technology: A Case Study of Lesvos Island in Greece. Energies 2024, 17, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Kim, H.-M.; Kim, Y.; Bak, S.; Kim, T.-Y.; Jang, S.W. A Framework for Detecting and Managing Non-Point-Source Pollution in Agricultural Areas Using GeoAI and UAVs. Drones 2024, 8, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V.; Maesano, C.; Genovese, E. Optimization of Crop Yield in Precision Agriculture Using WSNs, Remote Sensing, and Atmospheric Simulation Models for Real-Time Environmental Monitoring. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Song, X.; Xiao, W.; Kuang, D.; Xia, S.; Chang, H.; Wongsuk, S.; He, X.; Liu, Y. Low-Altitude Remote Sensing and Deep Learning-Based Canopy Detection Method for the Navigation of Orchard Unmanned Ground Vehicles. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 111077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapiou, A.; Vionis, A.; Papantoniou, G. Detection of Archaeological Surface Ceramics Using Deep Learning Image-Based Methods and Very High-Resolution UAV Imageries. Land 2021, 10, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikis, A.; Engdaw, M.; Pandey, D.; Pandey, B.K. The Impact of Urbanization on Land Use Land Cover Change Using Geographic Information System and Remote Sensing: A Case of Mizan Aman City Southwest Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhaneswaran, B.; Chamanee, G.; Kumara, B.T.G.S. A Comprehensive Review on the Integration of Geographic Information Systems and Artificial Intelligence for Landfill Site Selection: A Systematic Mapping Perspective. Waste Manag. Res. 2025, 43, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, B.; Prakash, V.; Garg, L.; Galdies, C.; Buttigieg, S.; Calleja, N. A Review of Satellite Image Analysis Tools. In Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Recent Trends in Machine Learning, IoT, Smart Cities and Applications; Gunjan, V.K., Zurada, J.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, S.; Shao, B.; Monteith, F.; Zhai, L. A Review of ArcGIS Spatial Analysis in Chinese Archaeobotany: Methods, Applications, and Challenges. Quaternary 2025, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathenge, M.; Sonneveld, B.G.J.S.; Broerse, J.E.W. Application of GIS in Agriculture in Promoting Evidence-Informed Decision Making for Improving Agriculture Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill, R.; Nash, E.; Grenzdörffer, G. GIS in Agriculture. In Springer Handbook of Geographic Information; Kresse, W., Danko, D.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 461–476. ISBN 978-3-540-72680-7. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Karkhi, M.I.; Rzadkowski, G.; Ibraheem, L.; Aqib, M. Anomaly Detection in Electrical Systems Using Machine Learning and Statistical Analysis. Terra Joule J. 2024, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Mohialden, Y.M.; Hussien, N.M. Hybrid Feature Selection and Ensemble Classification for Climate Change Indicators: A Machine Learning Approach. Terra Joule J. 2025, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarow, S.A.; Flayyih, H.A.; Bazerkan, M.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Ogaili, A.A.F. Advancing Sustainable Renewable Energy: XGBoost Algorithm for the Prediction of Water Yield in Hemispherical Solar Stills. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejbel, B.G.; Sarow, S.A.; Al-Sharify, M.T.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Ogaili, A.A.F.; Al-Sharify, Z.T. A Data Fusion Analysis and Random Forest Learning for Enhanced Control and Failure Diagnosis in Rotating Machinery. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2024, 24, 2979–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Mahdi, N.M.; Al-Haddad, S.A.; Al-Karkhi, M.I.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Farhan Ogaili, A.A. Protocol for UAV Fault Diagnosis Using Signal Processing and Machine Learning. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, M.; Yeneneh, K.; Sufe, G. Investigation of Spark Ignition Engine Performance in Ethanol–Petrol Blended Fuels Using Artificial Neural Network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Al-Nussairi, A.K.J.; Chevinli, Z.S.; Singh Sawaran Singh, N.; Chyad, M.H.; Yu, J.; Maesoumi, M. Integrating Digital Twins with Neural Networks for Adaptive Control of Automotive Suspension Systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wu, X.; Grosu, R.; Hou, J.; Ilolov, M.; Xiang, S. Applying Neural Network to Health Estimation and Lifetime Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 4224–4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Khan, P.; Kumar, S.; Das, S.K. $\log$-Sigmoid Activation-Based Long Short-Term Memory for Time-Series Data Classification. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, W.K.; Al-Haddad, L.A. Stacked Temporal Deep Learning for Early-Stage Degradation Forecasting in Lithium-Metal Batteries. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025, 5, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamandi, S.J.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Shaaban, S.M.; Flah, A. Child Behavior Recognition in Social Robot Interaction Using Stacked Deep Neural Networks and Biomechanical Signals. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Alawee, W.H.; Basem, A. Advancing Task Recognition towards Artificial Limbs Control with ReliefF-Based Deep Neural Network Extreme Learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 169, 107894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Giernacki, W.; Basem, A.; Khan, Z.H.; Jaber, A.A.; Al-Haddad, S.A. UAV Propeller Fault Diagnosis Using Deep Learning of Non-Traditional Χ2-Selected Taguchi Method-Tested Lempel–Ziv Complexity and Teager–Kaiser Energy Features. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A. An Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Approach for Multirotor UAVs Based on Deep Neural Network of Multi-Resolution Transform Features. Drones 2023, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Jaber, A.A. An Intelligent Quadcopter Unbalance Classification Method Based on Stochastic Gradient Descent Logistic Regression. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd Information Technology To Enhance e-learning and Other Application (IT-ELA), Baghdad, Iraq, 27–28 December 2022; pp. 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Alawee, W.H.; Dhahad, H.A.; Jaber, A.A.; Al-Haddad, S.A. Forecasting the Productivity of a Solar Distiller Enhanced with an Inclined Absorber Plate Using Stochastic Gradient Descent in Artificial Neural Networks. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2023, 7, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haddad, L.A.; Al-Muslim, Y.M.; Hammood, A.S.; Al-Zubaidi, A.A.; Khalil, A.M.; Ibraheem, Y.; Imran, H.J.; Fattah, M.Y.; Alawami, M.F.; Abdul-Ghani, A.M. Enhancing Building Sustainability through Aerodynamic Shading Devices: An Integrated Design Methodology Using Finite Element Analysis and Optimized Neural Networks. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 25, 4281–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flightradar24 Flight History for Iraqi Airways Flight IA223. Available online: https://www.flightradar24.com/data/flights/ia223 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Hakani, R.; Rawat, A. Edge Computing-Driven Real-Time Drone Detection Using YOLOv9 and NVIDIA Jetson Nano. Drones 2024, 8, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinney, C.J.; Woods, J.C. Low-Cost Raspberry-Pi-Based UAS Detection and Classification System Using Machine Learning. Aerospace 2022, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmirek, S.; Socha, V.; Malich, T.; Socha, L.; Hylmar, K.; Hanakova, L. Dynamic Flight Tracking: Designing System for Multirotor UAVs With Pixhawk Autopilot Data Verification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 109806–109821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Yang, G.Y.; Huang Fu, S.I. Research of Control System for Plant Protection UAV Based on Pixhawk. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 166, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Giles, D.K.; Andaloro, J.T.; Long, R.; Lang, E.B.; Watson, L.J.; Qandah, I. Comparison of UAV and Fixed-wing Aerial Application for Alfalfa Insect Pest Control: Evaluating Efficacy, Residues, and Spray Quality. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4980–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, R.C.; Lorencena, M.C.; Loureiro, J.F.; Favarim, F.; Todt, E. A Comparative Approach on the Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Kind of Fixed-Wing and Rotative Wing Applied to the Precision Agriculture Scenario. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 43rd Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 15–19 July 2019; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 522–526. [Google Scholar]

- Unde, S.S.; Kurkute, V.K.; Chavan, S.S.; Mohite, D.D.; Harale, A.A.; Chougle, A. The Expanding Role of Multirotor UAVs in Precision Agriculture with Applications AI Integration and Future Prospects. Discov. Mech. Eng. 2025, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, P.; Park, S.G.; Wei, P. Trajectory Optimization of Multirotor Agricultural UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 3–10 March 2018; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, J.; Sato, K. Wind Speed Measurement by an Inexpensive and Lightweight Thermal Anemometer on a Small UAV. Drones 2022, 6, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chang, Y.; Yang, L.; He, Y. Small Multi-Rotor UAV Oriented Direct Thrust Sensor Based on Lightweight Barometers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; IEEE: New York City, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 8175–8182. [Google Scholar]

- Tunca, E.; Köksal, E.S.; Taner, S.C. Calibrating UAV Thermal Sensors Using Machine Learning Methods for Improved Accuracy in Agricultural Applications. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2023, 133, 104804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Methodology/Application | AI Approach | Key Result/Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| [14] | Plant protection UAV path planning using real-world obstacle simulation | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) combined with an Improved Learning Algorithm (ILA) optimization strategy | Achieved shorter paths and fewer turns compared to traditional metaheuristic methods such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and the Zebra Optimization Algorithm (ZOA); however, the system lacks validation in actual field deployment. |

| [15] | UAV GPS jamming attack detection | Multimodal Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) fused with a multilayer perceptron (MLP) | Reached high classification accuracy (99%), but the scope is limited to cybersecurity concerns and does not address UAV path planning. |

| [16] | UAV-UGV collaborative Internet of Things (IoT) data collection and trajectory planning | Multi-agent Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) combined with a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) for energy-aware coordination | Ensures the UAV avoids power depletion by smartly coordinating with ground robots; however, the inter-agent coordination complexity increases significantly. |

| [17] | Review of reinforcement learning in UAV-IoT applications | Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), including value-based and actor-critic algorithms | Provides a comprehensive survey of methods but lacks experimental validation or deployment scenarios. |

| [18] | Chlorophyll estimation under drought stress using UAV multispectral imaging | You Only Look Once version 10s (YOLOv10s) combined with a Self-Attention Mechanism (SAM) and a deep neural network (DNN) | Achieved R2 = 0.75; demonstrated effective segmentation for phenotyping but does not generalize beyond agricultural sensing. |

| [19] | Weed detection in precision agriculture using UAVs and mobile robots | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Transfer Learning, and Self-supervised deep learning techniques | Achieved high classification performance; however, scalability to large-scale farming operations remains a challenge. |

| [20] | Power transmission line inspection using UAVs | Custom deep learning (DL) model integrated with a GIS interface | Enabled effective visual fault detection; nonetheless, application is limited to infrastructure inspection, not navigation. |

| [21] | Detection of non-point-source pollution in agriculture via UAV imagery | You Only Look Once version 8 (YOLOv8) integrated with Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) methods | Improved pollution area localization accuracy; lacks implementation for UAV motion planning or trajectory generation. |

| [22] | Crop yield optimization using drones, wireless sensor networks (WSNs), and GIS tools | Geospatial path optimization based on GIS layers and sensor feedback | Demonstrated enhanced field planning efficiency but did not include learning-based control strategies for autonomous UAVs. |

| [23] | Canopy detection and path planning for unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) supported by UAV sensing | Improved Lightweight YOLO (LS-YOLO) combined with Sliding Window Fusion algorithm | Showed a mean average precision (mAP) improvement of ~2%; however, the method is domain-specific to orchard environments. |

| [24] | Archaeological site mapping using UAV and image-based analysis | Random Forest classifier combined with a Single Shot Detector (SSD) Neural Network | Effective at detecting ceramic artifacts in excavation zones but lacks cross-domain utility, especially in agricultural contexts. |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Architecture | Input Layer—4 Hidden Layers—Output Layer |

| Number of Hidden Layers | 4 |

| Neurons per Layer | 128, 64, 32, 16 |

| Activation Function | Sigmoid |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 |

| Loss Function | Mean Squared Error (MSE) |

| Batch Size | 32 |

| Epochs | 100 |

| Training/Validation Split | 80%/20% |

| Weight Initialization | Xavier Initialization |

| No. | Assigned Line | Actual Line | DNN-Predicted Line | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (x) | East (y) | North (x) | East (y) | North (x) | East (y) | |||||||||||||

| Latitudes | Longitudes | Latitudes | Longitudes | Latitudes | Longitudes | |||||||||||||

| Dx1 | Mx1 | Sx1 | Dy1 | My1 | Sy1 | Dx2 | Mx2 | Sx2 | Dy2 | My2 | Sy2 | Dx3 | Mx3 | Sx3 | Dy3 | My3 | Sy3 | |

| 1 | 40 | 59 | 23.785 | 28 | 48 | 29.377 | 41 | 08 | 23.785 | 28 | 48 | 29.377 | 40 | 55 | 22.886 | 28 | 39 | 28.244 |

| 2 | 41 | 03 | 10.240 | 28 | 39 | 34.512 | 41 | 04 | 10.240 | 28 | 39 | 34.512 | 41 | 06 | 10.340 | 28 | 40 | 37.200 |

| 3 | 41 | 13 | 13.291 | 28 | 37 | 44.867 | 41 | 07 | 2.435 | 28 | 33 | 24.108 | 41 | 11 | 13.288 | 28 | 30 | 45.876 |

| 4 | 41 | 13 | 44.400 | 28 | 26 | 6.000 | 41 | 10 | 44.400 | 28 | 26 | 6.000 | 41 | 16 | 43.3990 | 28 | 24 | 6.333 |

| 5 | 41 | 9.0 | 0.000 | 28 | 19 | 55.200 | 41 | 13 | 40.800 | 28 | 19 | 48.000 | 41 | 10 | 10.022 | 28 | 20 | 56.540 |

| 6 | 41 | 01 | 20.595 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 41 | 03 | 14.057 | 28 | 27 | 31.258 | 41 | 05 | 19.999 | 28 | 23 | 47.662 |

| 7 | 40 | 52 | 12.367 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 40 | 52 | 23.077 | 28 | 30 | 42.422 | 40 | 52 | 14.360 | 28 | 29 | 45.987 |

| 8 | 40 | 49 | 27.898 | 28 | 21 | 18.057 | 40 | 47 | 34.450 | 28 | 31 | 9.964 | 40 | 47 | 25.664 | 28 | 20 | 16.040 |

| 9 | 40 | 36 | 40.379 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 40 | 36 | 17.755 | 28 | 32 | 14.540 | 40 | 36 | 42.000 | 28 | 22 | 40.201 |

| 10 | 40 | 25 | 43.462 | 28 | 52 | 51.647 | 40 | 30 | 49.999 | 28 | 51 | 55.713 | 40 | 24 | 41.375 | 28 | 51 | 55.400 |

| 11 | 40 | 20 | 6.397 | 29 | 24 | 43.405 | 40 | 26 | 27.600 | 29 | 25 | 22.800 | 40 | 22 | 5.000 | 29 | 22 | 41.321 |

| 12 | 40 | 18 | 1.712 | 29 | 55 | 6.284 | 40 | 26 | 14.036 | 29 | 55 | 36.195 | 40 | 19 | 3719 | 29 | 57 | 9.775 |

| 13 | 40 | 15 | 53.536 | 30 | 24 | 56.980 | 40 | 23 | 4.563 | 30 | 23 | 30.372 | 40 | 18 | 50.400 | 30 | 22 | 49.886 |

| 14 | 40 | 18 | 23.924 | 30 | 22 | 33.996 | 40 | 25 | 12.600 | 30 | 22 | 18.454 | 40 | 21 | 49.387 | 30 | 22 | 48.692 |

| 15 | 40 | 23 | 59.465 | 31 | 29 | 20.779 | 40 | 12 | 1139 | 31 | 18 | 22.856 | 40 | 25 | 58.200 | 31 | 31 | 24.770 |

| 16 | 40 | 21 | 8.392 | 31 | 51 | 27.296 | 40 | 07 | 58.960 | 34 | 45 | 49.738 | 40 | 20 | 10.150 | 31 | 33 | 28.284 |

| 17 | 40 | 14 | 10.152 | 32 | 25 | 57.337 | 40 | 02 | 50.900 | 35 | 26 | 33.338 | 40 | 16 | 12.400 | 32 | 29 | 51.000 |

| 18 | 40 | 6 | 16.402 | 32 | 36 | 32.129 | 39 | 58 | 38.688 | 35 | 35 | 26.415 | 40 | 08 | 18.202 | 32 | 36 | 33.280 |

| 19 | 39 | 54 | 6.648 | 32 | 58 | 3.530 | 39 | 47 | 18.580 | 35 | 53 | 48.615 | 39 | 48 | 7.809 | 32 | 55 | 9.400 |

| 20 | 39 | 30 | 46.040 | 33 | 07 | 40.247 | 39 | 34 | 18.776 | 36 | 14 | 52.386 | 39 | 33 | 45.049 | 33 | 08 | 46.802 |

| 21 | 39 | 18 | 5.620 | 33 | 22 | 49.574 | 39 | 27 | 57.600 | 36 | 31 | 55.200 | 39 | 14 | 7.020 | 33 | 19 | 50.331 |

| 22 | 39 | 13 | 31.506 | 34 | 4 | 51.422 | 39 | 22 | 47.741 | 37 | 08 | 8.347 | 39 | 19 | 33.596 | 34 | 09 | 53.200 |

| 23 | 39 | 05 | 34.055 | 34 | 40 | 44.198 | 39 | 17 | 46.437 | 37 | 43 | 21.492 | 39 | 08 | 36.000 | 34 | 32 | 43.300 |

| 24 | 39 | 02 | 16.888 | 35 | 22 | 36.976 | 39 | 11 | 54.305 | 38 | 22 | 9.142 | 39 | 10 | 18.550 | 35 | 25 | 35.221 |

| 25 | 39 | 04 | 40.723 | 36 | 04 | 6.102 | 39 | 04 | 40.723 | 39 | 04 | 6.102 | 39 | 11 | 42.600 | 36 | 07 | 8.995 |

| 26 | 39 | 07 | 11.977 | 36 | 36 | 25.399 | 38 | 57 | 8.624 | 39 | 34 | 9.446 | 39 | 07 | 13.450 | 36 | 38 | 29.000 |

| 27 | 39 | 01 | 23.981 | 37 | 28 | 31.915 | 38 | 44 | 7.582 | 39 | 25 | 39.337 | 39 | 04 | 23.981 | 37 | 26 | 38.412 |

| 28 | 38 | 47 | 1.646 | 38 | 04 | 14.991 | 41 | 08 | 23.785 | 40 | 48 | 29.377 | 38 | 42 | 2.770 | 38 | 11 | 12.602 |

| 29 | 38 | 26 | 45.796 | 38 | 43 | 12.494 | 41 | 08 | 23.785 | 40 | 48 | 29.377 | 40 | 55 | 22.886 | 37 | 39 | 28.244 |

| 30 | 38 | 24 | 24.626 | 39 | 11 | 49.902 | 41 | 04 | 10.240 | 40 | 39 | 34.512 | 41 | 06 | 10.340 | 37 | 40 | 37.200 |

| 31 | 38 | 16 | 48.874 | 39 | 47 | 34.300 | 41 | 07 | 2.435 | 40 | 33 | 24.108 | 41 | 11 | 13.288 | 36 | 30 | 45.876 |

| 32 | 38 | 11 | 17.151 | 40 | 15 | 51.688 | 41 | 10 | 44.400 | 40 | 26 | 6.000 | 41 | 16 | 43.3990 | 36 | 24 | 6.333 |

| 33 | 38 | 7 | 29.343 | 40 | 41 | 5.290 | 41 | 13 | 40.800 | 40 | 19 | 48.000 | 41 | 10 | 10.022 | 36 | 20 | 56.540 |

| 34 | 38 | 3 | 35.743 | 41 | 09 | 48.801 | 41 | 03 | 14.057 | 40 | 27 | 31.258 | 41 | 05 | 19.999 | 35 | 23 | 47.662 |

| 35 | 37 | 40 | 21.542 | 41 | 28 | 18.933 | 40 | 52 | 23.077 | 40 | 30 | 42.422 | 40 | 52 | 14.360 | 35 | 29 | 45.987 |

| 36 | 37 | 32 | 30.345 | 41 | 47 | 26.828 | 40 | 47 | 34.450 | 40 | 31 | 9.964 | 40 | 47 | 25.664 | 35 | 20 | 16.040 |

| 37 | 37 | 31 | 29.812 | 42 | 15 | 48.555 | 40 | 36 | 17.755 | 40 | 32 | 14.540 | 40 | 36 | 42.000 | 35 | 22 | 40.201 |

| 38 | 37 | 22 | 33.108 | 42 | 39 | 7.226 | 40 | 30 | 49.999 | 40 | 51 | 55.713 | 40 | 24 | 41.375 | 36 | 51 | 55.400 |

| 39 | 37 | 15 | 27.952 | 43 | 12 | 16.998 | 40 | 26 | 27.600 | 40 | 25 | 22.800 | 40 | 22 | 5.000 | 36 | 22 | 41.321 |

| 40 | 37 | 08 | 38.400 | 43 | 33 | 39.600 | 40 | 26 | 14.036 | 41 | 55 | 36.195 | 40 | 19 | 3719 | 36 | 57 | 9.775 |

| 41 | 36 | 33 | 32.178 | 44 | 01 | 1.896 | 40 | 23 | 4.563 | 41 | 23 | 30.372 | 40 | 18 | 50.400 | 37 | 22 | 49.886 |

| 42 | 36 | 08 | 8.203 | 44 | 14 | 40.994 | 40 | 18 | 23.924 | 41 | 52 | 58.638 | 40 | 16 | 26.335 | 37 | 51 | 51.100 |

| 43 | 35 | 35 | 35.373 | 44 | 29 | 51.954 | 40 | 12 | 1139 | 41 | 18 | 22.856 | 40 | 25 | 58.200 | 37 | 31 | 24.770 |

| 44 | 34 | 55 | 45.458 | 44 | 48 | 26.805 | 40 | 07 | 58.960 | 42 | 45 | 49.738 | 40 | 20 | 10.150 | 38 | 33 | 28.284 |

| 45 | 34 | 18 | 0.000 | 45 | 06 | 3.600 | 40 | 02 | 50.900 | 42 | 26 | 33.338 | 40 | 16 | 12.400 | 39 | 29 | 51.000 |

| 46 | 33 | 56 | 39.197 | 45 | 06 | 53.379 | 39 | 58 | 38.688 | 43 | 35 | 26.415 | 40 | 08 | 18.202 | 39 | 36 | 33.280 |

| 47 | 33 | 48 | 25.109 | 45 | 07 | 12.582 | 39 | 47 | 18.580 | 43 | 53 | 48.615 | 39 | 48 | 7.809 | 39 | 55 | 9.400 |

| 48 | 33 | 36 | 58.198 | 45 | 07 | 39.279 | 39 | 34 | 18.776 | 43 | 14 | 52.386 | 39 | 33 | 45.049 | 40 | 08 | 46.802 |

| 49 | 33 | 31 | 33.179 | 45 | 07 | 51.911 | 39 | 27 | 57.600 | 42 | 31 | 55.200 | 39 | 14 | 7.020 | 40 | 19 | 50.331 |

| 50 | 33 | 23 | 47.985 | 45 | 08 | 9.991 | 39 | 22 | 47.741 | 41 | 08 | 8.347 | 39 | 19 | 33.596 | 41 | 09 | 53.200 |

| 51 | 33 | 09 | 13.987 | 44 | 58 | 20.574 | 39 | 17 | 46.437 | 41 | 43 | 21.492 | 39 | 08 | 36.000 | 41 | 32 | 43.300 |

| 52 | 33 | 06 | 55.480 | 44 | 42 | 38.521 | 39 | 11 | 54.305 | 40 | 22 | 9.142 | 39 | 10 | 18.550 | 42 | 25 | 35.221 |

| 53 | 33 | 04 | 26.023 | 44 | 25 | 20.000 | 39 | 04 | 40.723 | 40 | 04 | 6.102 | 39 | 11 | 42.600 | 41 | 07 | 35,444 |

| 54 | 33 | 02 | 38.400 | 44 | 13 | 30.000 | 38 | 57 | 8.624 | 40 | 34 | 9.446 | 39 | 07 | 13.450 | 40 | 38 | 28.432 |

| 55 | 33 | 09 | 28.800 | 44 | 08 | 27.600 | 38 | 44 | 7.582 | 40 | 25 | 39.337 | 39 | 04 | 23.981 | 38 | 26 | 28,225 |

| 56 | 33 | 13 | 45.865 | 44 | 13 | 26.900 | 38 | 42 | 6.772 | 40 | 22 | 40.4342 | 39 | 10 | 24.221 | 38 | 20 | 28.900 |

| No. | Assigned Line | Actual Line | DNN-Predicted Line | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (x) | East (y) | North (x) | East (y) | North (x) | East (y) | |||||||||||||

| Latitudes | Longitudes | Latitudes | Longitudes | Latitudes | Longitudes | |||||||||||||

| Dx1 | Mx1 | Sx1 | Dy1 | My1 | Sy1 | Dx2 | Mx2 | Sx2 | Dy2 | My2 | Sy2 | Dx3 | Mx3 | Sx3 | Dy3 | My3 | Sy3 | |

| 1 | 33 | 12 | 45.865 | 44 | 19 | 23.936 | 33 | 12 | 45.865 | 44 | 19 | 23.936 | 33 | 40 | 9.878 | 44 | 04 | 17.081 |

| 2 | 33 | 16 | 14.445 | 44 | 09 | 47.111 | 33 | 16 | 14.445 | 44 | 09 | 47.111 | 33 | 12 | 50.925 | 44 | 28 | 15.167 |

| 3 | 33 | 08 | 43.665 | 44 | 08 | 52.849 | 33 | 08 | 43.665 | 44 | 08 | 52.849 | 33 | 09 | 54.308 | 44 | 36 | 48.818 |

| 4 | 32 | 50 | 32.675 | 44 | 14 | 23.936 | 32 | 50 | 32.675 | 44 | 14 | 23.936 | 32 | 06 | 44.825 | 44 | 04 | 51.838 |

| 5 | 32 | 49 | 56.281 | 44 | 40 | 51.166 | 32 | 49 | 56.281 | 44 | 40 | 51.166 | 32 | 00 | 56.720 | 44 | 22 | 49.272 |

| 6 | 33 | 06 | 28.280 | 45 | 07 | 43.825 | 33 | 06 | 28.280 | 45 | 07 | 43.825 | 33 | 09 | 54.334 | 45 | 40 | 21.881 |

| 7 | 33 | 28 | 39.894 | 45 | 09 | 23.895 | 33 | 28 | 39.894 | 45 | 09 | 23.895 | 33 | 14 | 55.110 | 45 | 4 | 37.173 |

| 8 | 33 | 30 | 47.786 | 44 | 52 | 25.243 | 33 | 30 | 47.786 | 44 | 52 | 25.243 | 33 | 17 | 35.734 | 44 | 22 | 24.839 |

| 9 | 33 | 46 | 42.783 | 44 | 57 | 3.967 | 33 | 46 | 42.783 | 44 | 57 | 3.967 | 33 | 35 | 51.570 | 44 | 58 | 38.839 |

| 10 | 33 | 53 | 4.242 | 44 | 50 | 30.420 | 34 | 53 | 4.242 | 44 | 50 | 30.420 | 33 | 56 | 58.054 | 44 | 36 | 1.586 |

| 11 | 34 | 08 | 55.799 | 45 | 08 | 43.682 | 34 | 08 | 55.799 | 45 | 08 | 43.682 | 34 | 08 | 17.151 | 45 | 25 | 51.688 |

| 12 | 34 | 17 | 0.000 | 45 | 07 | 3.600 | 34 | 17 | 0.000 | 45 | 07 | 3.600 | 34 | 14 | 23.364 | 45 | 51 | 11.882 |

| 13 | 35 | 04 | 15.241 | 44 | 56 | 4.534 | 35 | 04 | 15.241 | 44 | 56 | 4.534 | 35 | 23 | 46.664 | 44 | 29 | 17.754 |

| 14 | 35 | 38 | 3.684 | 44 | 34 | 58.433 | 35 | 38 | 3.684 | 44 | 34 | 58.433 | 35 | 23 | 17.177 | 44 | 52 | 17.081 |

| 15 | 36 | 17 | 9.878 | 44 | 27 | 17.081 | 36 | 17 | 9.878 | 44 | 27 | 17.081 | 36 | 29 | 9.878 | 44 | 24 | 15.167 |

| 16 | 36 | 40 | 50.925 | 44 | 06 | 15.167 | 36 | 40 | 50.925 | 44 | 06 | 15.167 | 36 | 29 | 50.925 | 44 | 17 | 45.865 |

| 17 | 36 | 42 | 54.308 | 43 | 34 | 48.818 | 36 | 42 | 54.308 | 43 | 34 | 48.818 | 36 | 28 | 54.308 | 44 | 40 | 14.445 |

| 18 | 37 | 08 | 44.825 | 43 | 08 | 51.838 | 37 | 08 | 44.825 | 43 | 08 | 51.838 | 36 | 28 | 44.825 | 43 | 42 | 43.665 |

| 19 | 37 | 10 | 56.720 | 42 | 31 | 49.272 | 37 | 10 | 56.720 | 42 | 31 | 49.272 | 37 | 28 | 56.720 | 43 | 08 | 32.675 |

| 20 | 37 | 12 | 54.334 | 42 | 14 | 21.881 | 37 | 12 | 54.334 | 42 | 14 | 21.881 | 37 | 28 | 54.334 | 42 | 10 | 56.281 |

| 21 | 37 | 21 | 55.110 | 41 | 46 | 37.173 | 37 | 21 | 55.110 | 41 | 46 | 37.173 | 37 | 28 | 55.110 | 42 | 12 | 28.280 |

| 22 | 37 | 48 | 35.734 | 41 | 24 | 24.839 | 37 | 48 | 35.734 | 41 | 24 | 24.839 | 37 | 28 | 35.734 | 41 | 21 | 39.894 |

| 23 | 37 | 53 | 51.570 | 41 | 18 | 38.839 | 37 | 53 | 51.570 | 41 | 18 | 38.839 | 37 | 28 | 51.570 | 41 | 48 | 47.786 |

| 24 | 38 | 08 | 58.054 | 40 | 49 | 1.586 | 38 | 08 | 58.054 | 40 | 49 | 1.586 | 37 | 28 | 58.054 | 41 | 53 | 42.783 |

| 25 | 38 | 15 | 17.151 | 40 | 13 | 51.688 | 38 | 15 | 17.151 | 40 | 13 | 51.688 | 38 | 28 | 17.151 | 40 | 08 | 4.242 |

| 26 | 38 | 26 | 23.364 | 39 | 40 | 11.882 | 38 | 26 | 23.364 | 39 | 40 | 11.882 | 38 | 28 | 23.364 | 40 | 15 | 55.799 |

| 27 | 38 | 22 | 46.664 | 39 | 19 | 17.754 | 38 | 22 | 46.664 | 39 | 19 | 17.754 | 38 | 29 | 46.664 | 39 | 26 | 0.000 |

| 28 | 38 | 46 | 17.177 | 38 | 22 | 37.548 | 38 | 46 | 17.177 | 38 | 22 | 37.548 | 38 | 29 | 17.177 | 39 | 22 | 15.241 |

| 29 | 38 | 40 | 1.646 | 38 | 04 | 14.991 | 38 | 40 | 1.646 | 38 | 04 | 14.991 | 33 | 44 | 58.433 | 43 | 12 | 23.936 |

| 30 | 39 | 12 | 23.981 | 37 | 28 | 31.915 | 39 | 12 | 23.981 | 37 | 28 | 31.915 | 33 | 44 | 17.081 | 43 | 16 | 47.111 |

| 31 | 39 | 09 | 11.977 | 36 | 36 | 25.399 | 39 | 09 | 11.977 | 36 | 36 | 25.399 | 33 | 43 | 15.167 | 43 | 08 | 52.849 |

| 32 | 39 | 06 | 40.723 | 36 | 04 | 6.102 | 39 | 06 | 40.723 | 36 | 04 | 6.102 | 32 | 43 | 48.818 | 42 | 50 | 23.936 |

| 33 | 39 | 00 | 16.888 | 35 | 22 | 36.976 | 39 | 00 | 16.888 | 35 | 22 | 36.976 | 32 | 42 | 51.838 | 42 | 49 | 51.166 |

| 34 | 39 | 09 | 34.055 | 34 | 40 | 44.198 | 39 | 09 | 34.055 | 34 | 40 | 44.198 | 33 | 42 | 49.272 | 40 | 06 | 43.825 |

| 35 | 39 | 14 | 31.506 | 34 | 09 | 51.422 | 39 | 14 | 31.506 | 34 | 4 | 51.422 | 33 | 41 | 21.881 | 39 | 28 | 23.895 |

| 36 | 39 | 17 | 5.620 | 33 | 22 | 49.574 | 39 | 17 | 5.620 | 33 | 22 | 49.574 | 33 | 41 | 37.173 | 38 | 30 | 25.243 |

| 37 | 39 | 35 | 46.040 | 32 | 58 | 3.530 | 39 | 35 | 46.040 | 32 | 58 | 3.530 | 33 | 41 | 24.839 | 38 | 46 | 3.967 |

| 38 | 39 | 56 | 6.648 | 32 | 36 | 32.129 | 39 | 56 | 6.648 | 32 | 36 | 32.129 | 33 | 40 | 38.839 | 37 | 53 | 30.420 |

| 39 | 40 | 08 | 16.402 | 32 | 25 | 57.337 | 39 | 08 | 16.402 | 32 | 25 | 57.337 | 34 | 40 | 1.586 | 36 | 08 | 43.682 |

| 40 | 40 | 14 | 10.152 | 31 | 51 | 27.296 | 40 | 14 | 10.152 | 31 | 51 | 27.296 | 34 | 39 | 51.688 | 35 | 04 | 3.600 |

| 41 | 40 | 23 | 8.392 | 31 | 29 | 20.779 | 40 | 23 | 8.392 | 31 | 29 | 20.779 | 35 | 39 | 11.882 | 34 | 28 | 4.534 |

| 42 | 40 | 23 | 59.465 | 30 | 52 | 58.638 | 40 | 23 | 59.465 | 30 | 52 | 58.638 | 35 | 38 | 17.754 | 33 | 36 | 23.936 |

| 43 | 40 | 17 | 23.924 | 30 | 24 | 56.980 | 40 | 17 | 23.924 | 30 | 24 | 56.980 | 35 | 44 | 37.548 | 32 | 04 | 47.111 |

| 44 | 40 | 19 | 53.536 | 29 | 55 | 6.284 | 40 | 19 | 53.536 | 29 | 55 | 6.284 | 36 | 12 | 17.081 | 31 | 22 | 23.936 |

| 45 | 40 | 18 | 1.712 | 29 | 24 | 43.405 | 40 | 18 | 1.712 | 29 | 24 | 43.405 | 36 | 16 | 15.167 | 31 | 40 | 47.111 |

| 46 | 40 | 13 | 6.397 | 28 | 52 | 51.647 | 40 | 13 | 6.397 | 28 | 52 | 51.647 | 36 | 08 | 48.818 | 30 | 4 | 52.849 |

| 47 | 40 | 20 | 43.462 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 40 | 20 | 43.462 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 37 | 50 | 51.838 | 30 | 22 | 23.936 |

| 48 | 40 | 30 | 40.379 | 28 | 21 | 18.057 | 40 | 30 | 40.379 | 28 | 21 | 18.057 | 37 | 49 | 49.272 | 30 | 58 | 51.166 |

| 49 | 40 | 41 | 27.898 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 40 | 41 | 27.898 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 37 | 06 | 21.881 | 30 | 36 | 43.825 |

| 50 | 40 | 49 | 12.367 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 40 | 49 | 12.367 | 28 | 26 | 46.993 | 37 | 28 | 37.173 | 30 | 25 | 23.895 |

| 51 | 41 | 08 | 20.595 | 28 | 19 | 55.200 | 41 | 08 | 20.595 | 28 | 19 | 55.200 | 37 | 30 | 24.839 | 30 | 51 | 25.243 |

| 52 | 41 | 07 | 0.000 | 28 | 26 | 6.000 | 41 | 01 | 0.000 | 28 | 26 | 6.000 | 37 | 46 | 38.839 | 30 | 29 | 3.967 |

| 53 | 41 | 17 | 44.400 | 28 | 37 | 44.867 | 41 | 17 | 44.400 | 28 | 37 | 44.867 | 38 | 53 | 1.586 | 31 | 52 | 30.420 |

| 54 | 41 | 11 | 13.291 | 28 | 37 | 44.867 | 41 | 11 | 13.291 | 28 | 37 | 44.867 | 38 | 08 | 51.688 | 30 | 24 | 43.682 |

| 55 | 41 | 10 | 10.240 | 28 | 48 | 29.377 | 41 | 10 | 10.240 | 28 | 48 | 29.377 | 38 | 17 | 11.882 | 31 | 09 | 3.600 |

| 56 | 40 | 55 | 22.666 | 32 | 22 | 36.976 | 40 | 55 | 22.666 | 32 | 22 | 36.976 | 38 | 04 | 17.754 | 33 | 00 | 4.534 |

| Comparison | Fuel Consumption (kg) | Time (h) | Distance (km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assigned | 4643 | 03.12 | 1685 |

| Actual | 4938 | 03.33 | 1750 |

| DNN | 4302 | 02.58 | 1628 |

| Difference (Actual − DNN) | 636 | 35 min | 122 |

| Comparison | Fuel Consumption (kg) | Time (h) | Distance (km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assigned | 4250 | 03.05 | 1702 |

| Actual | 4872 | 03.45 | 1788 |

| DNN | 4245 | 03.10 | 1660 |

| Difference (Actual − DNN) | 627 | 35 min | 128 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kurdi, S.T.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Ogaili, A.A.F. Path Optimization for Aircraft Based on Geographic Information Systems and Deep Learning. Automation 2026, 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010012

Kurdi ST, Al-Haddad LA, Ogaili AAF. Path Optimization for Aircraft Based on Geographic Information Systems and Deep Learning. Automation. 2026; 7(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurdi, Saadi Turied, Luttfi A. Al-Haddad, and Ahmed Ali Farhan Ogaili. 2026. "Path Optimization for Aircraft Based on Geographic Information Systems and Deep Learning" Automation 7, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010012

APA StyleKurdi, S. T., Al-Haddad, L. A., & Ogaili, A. A. F. (2026). Path Optimization for Aircraft Based on Geographic Information Systems and Deep Learning. Automation, 7(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010012