HDR-IRSTD: Detection-Driven HDR Infrared Image Enhancement and Small Target Detection Based on HDR Infrared Image Enhancement

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A small target detection framework based on HDR infrared image enhancement (HDR-IRSTD-Net) is designed, achieving detection-oriented HDR infrared image enhancement and detection based on HDR infrared images.

- (2)

- A cooperative training scheme is proposed, using cooperative optimization to combine HDR infrared image enhancement and small target detection, allowing both the enhancement and detection networks to reach optimal parameters, resulting in better image enhancement visual effects and higher detection accuracy.

- (3)

- By analyzing the dynamic range of raw images from various imaging backgrounds and target types across long-wave, mid-wave, and short-wave infrared sensors, we generated 16-bit images with multiple dynamic ranges based on the NUDT-SIRST and SIRST datasets and created the NUDT-SIRST-16bit dataset, solving the current issue of lacking HDR infrared small target datasets. By analyzing the dynamic range of raw images from infrared sensors with different wavelengths for various imaging backgrounds and target types, we generated 16-bit images with multiple dynamic ranges based on the NUDT-SIRST and SIRST datasets. This led to the creation of the NUDT-SIRST-16bit and SIRST-16bit datasets, effectively addressing the current lack of HDR infrared weak target datasets.

- (4)

- Comparative experiments with other algorithms on the NUDT-SIRST-16bit and SIRST-16bit datasets show that the proposed framework outperforms other algorithms in metrics such as Pd, Fa, and mIoU, demonstrating strong application potential.

2. Related Work

2.1. Infrared Image Enhancement and Dynamic Range Compression

2.2. Single-Frame Infrared Small Target Detection

2.3. State Space Models and Their Advantages in the Field of Target Segmentation

3. Proposed Method

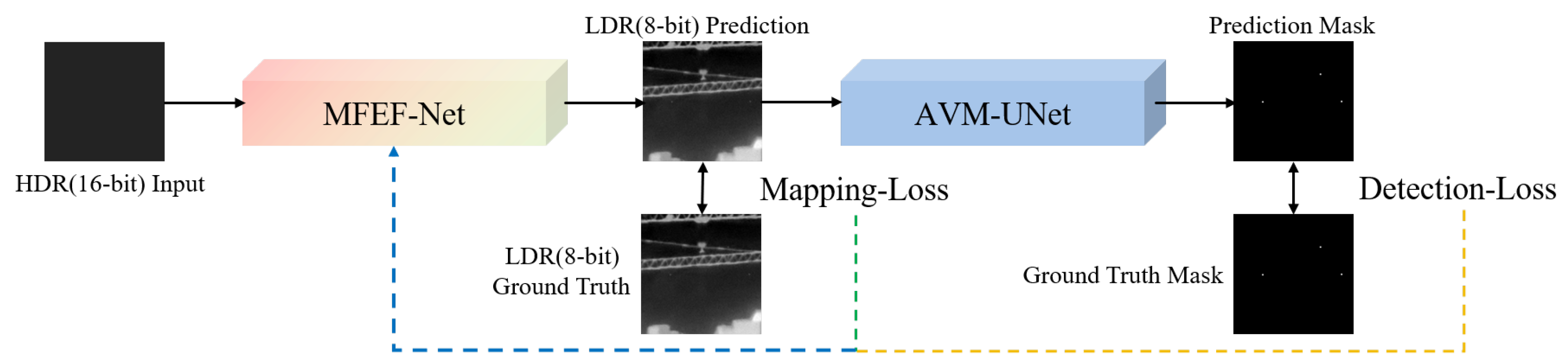

3.1. Overview of the Detection Framework Based on HDR Infrared Image Enhancement

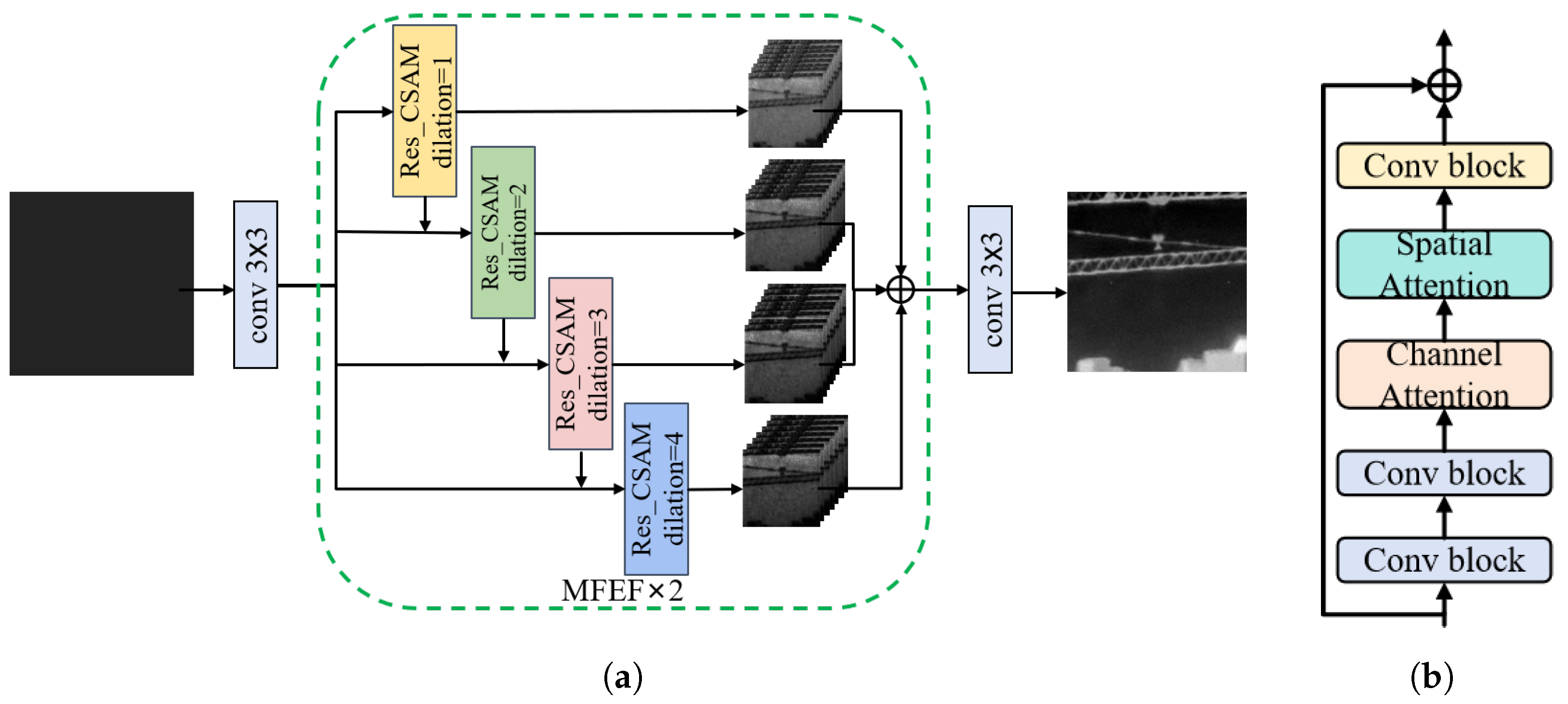

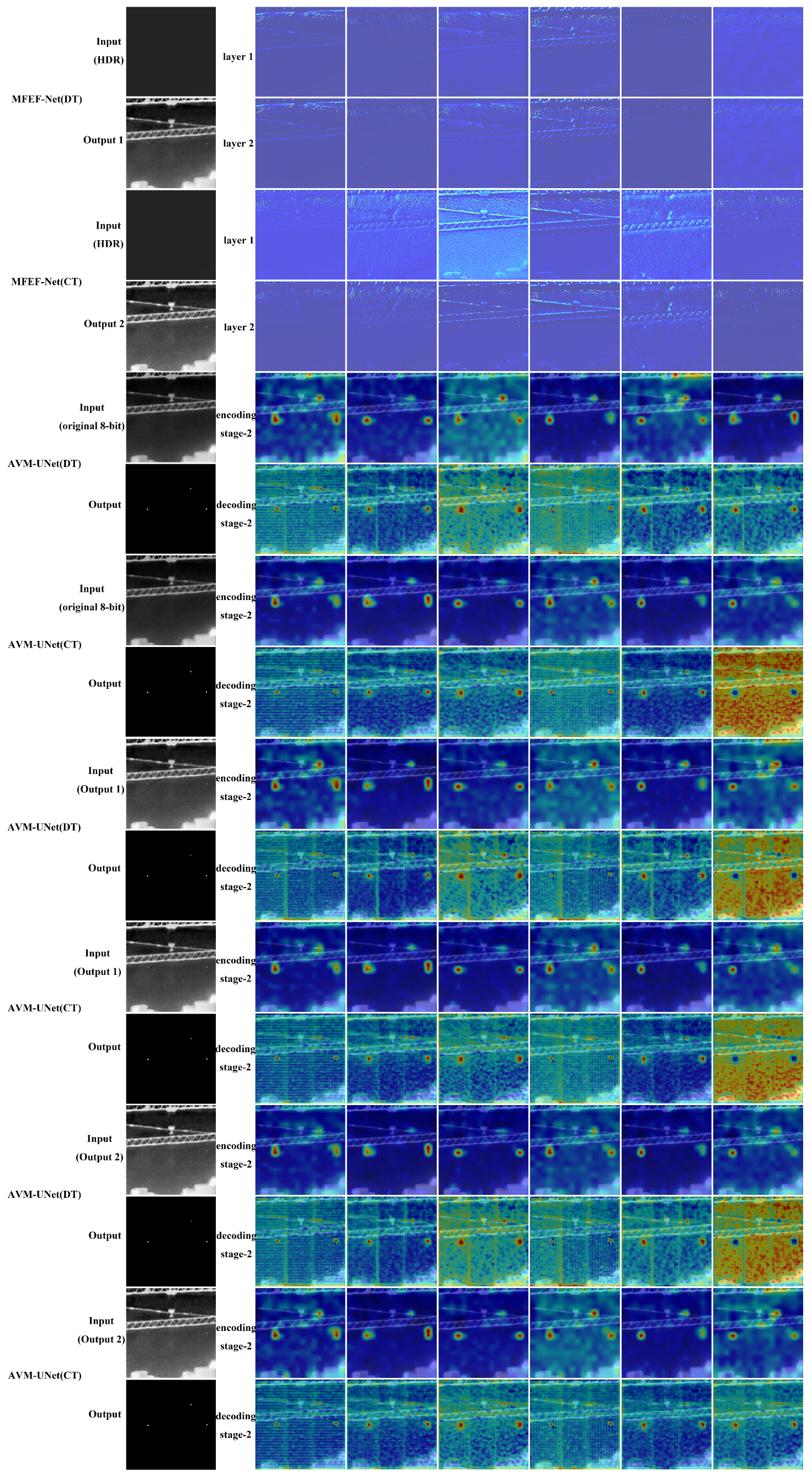

3.2. MFEF-Net

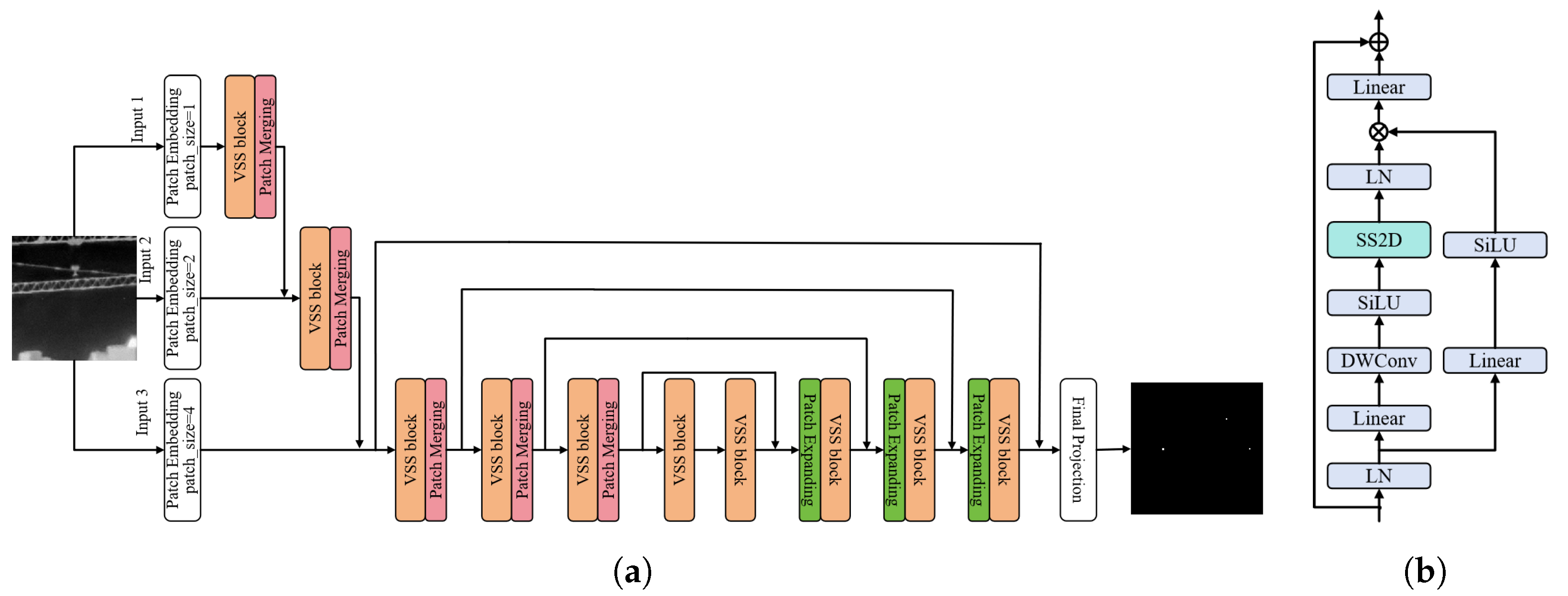

3.3. AVM-UNet

| Algorithm 1 SS2D |

|

| Algorithm 2 SelectiveScan in SS2D |

|

3.4. Loss Functions and Cooperative Training Strategy

3.4.1. Loss Function

3.4.2. Cooperative Training Strategy

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.1.3. Implementation Details

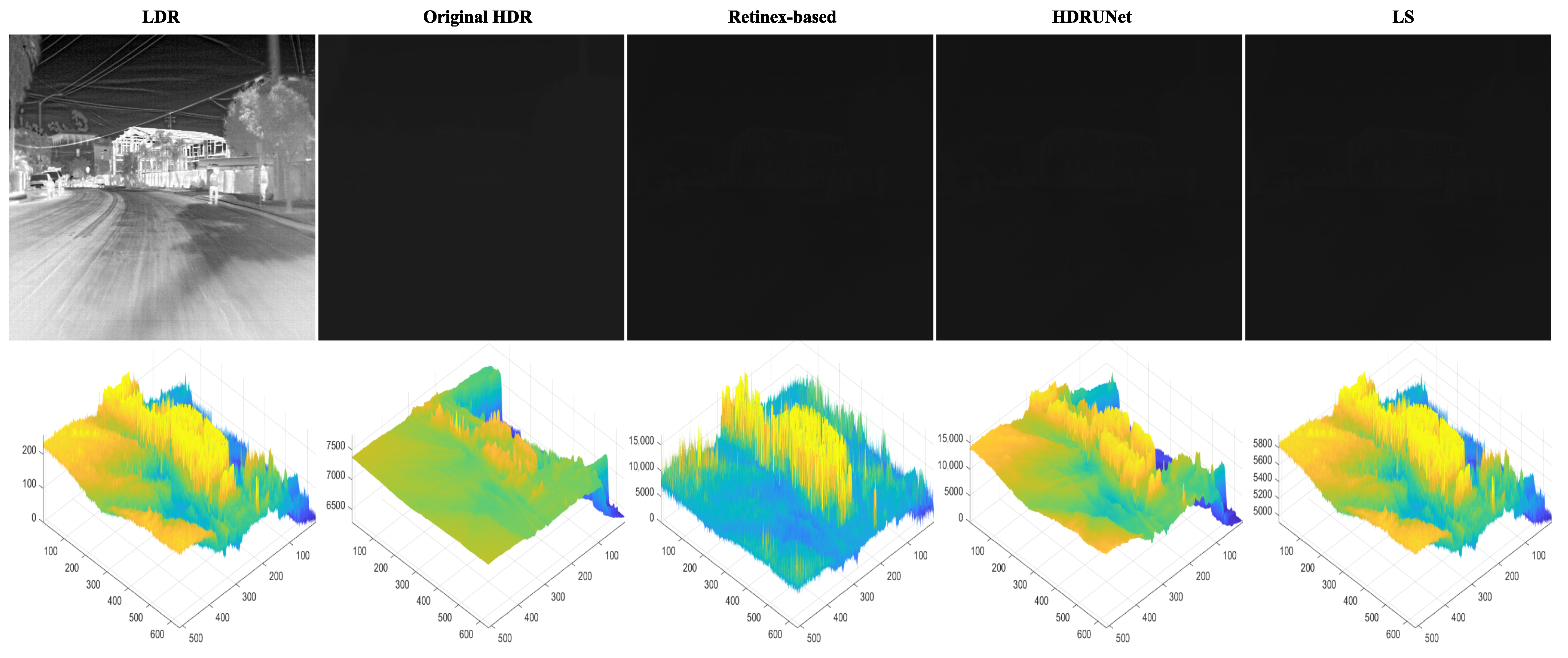

4.2. HDR Infrared Image Enhancement Results

4.3. Analysis of Infrared Small Target Detection Results

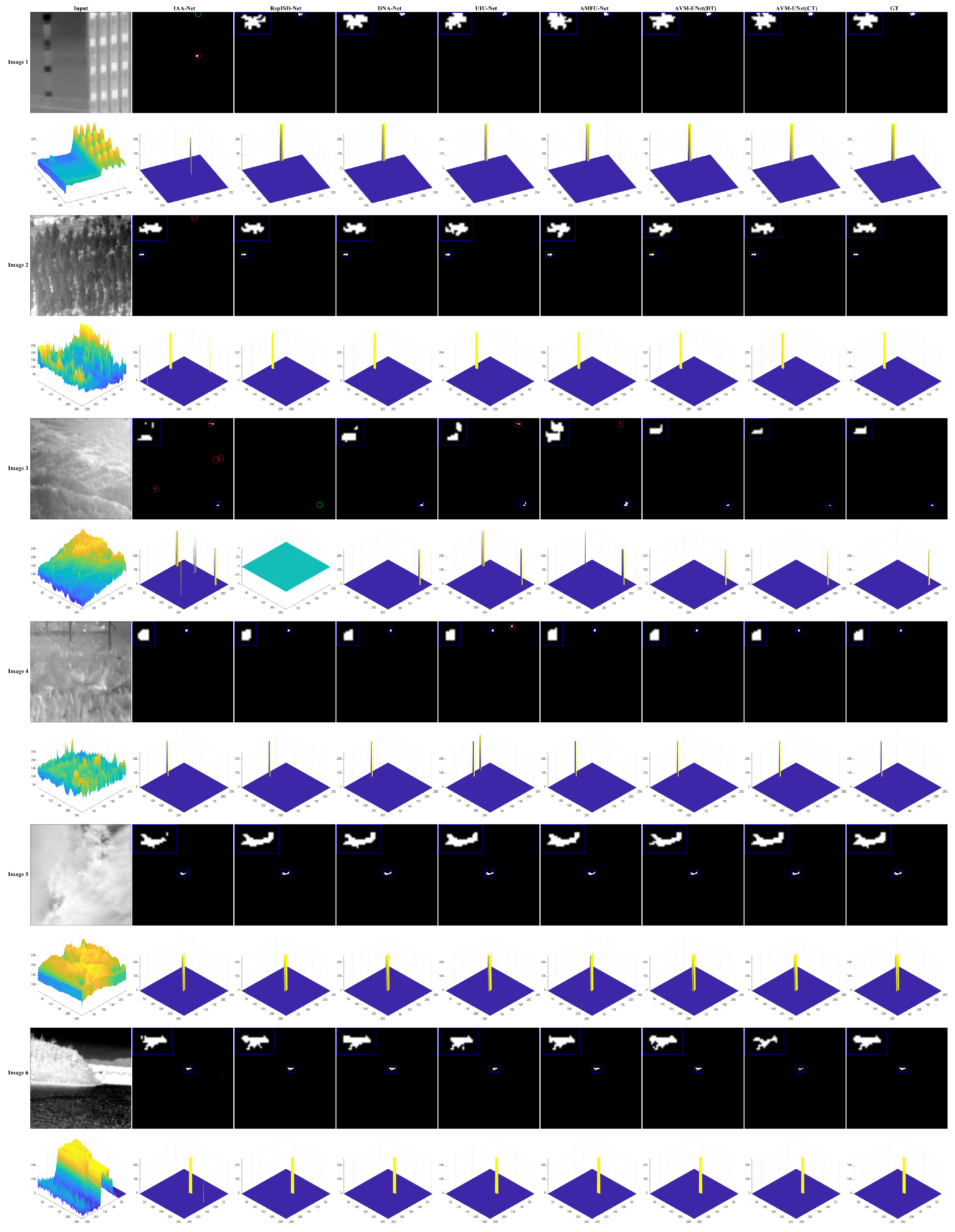

4.3.1. AVM-UNet Detection Performance Analysis

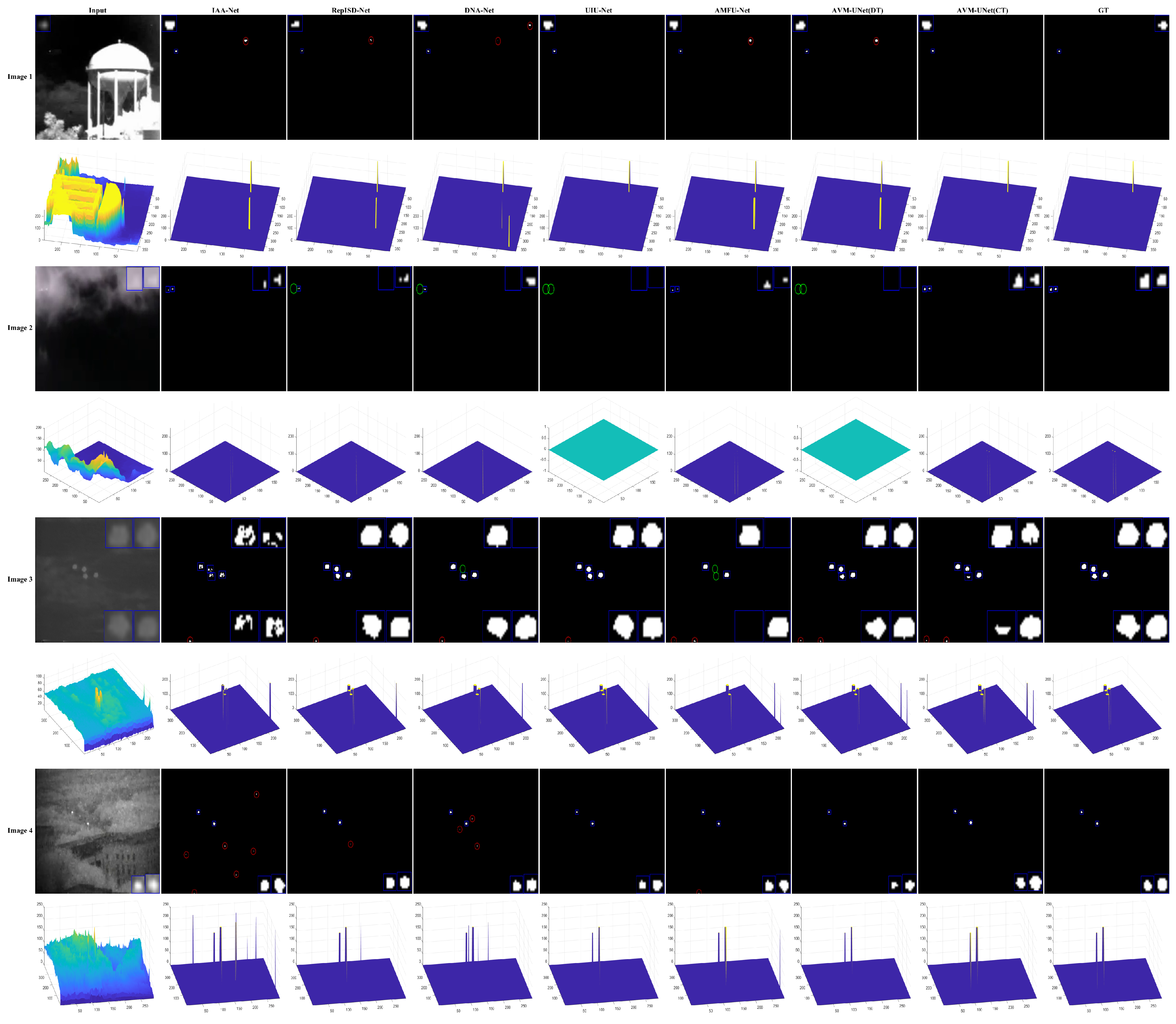

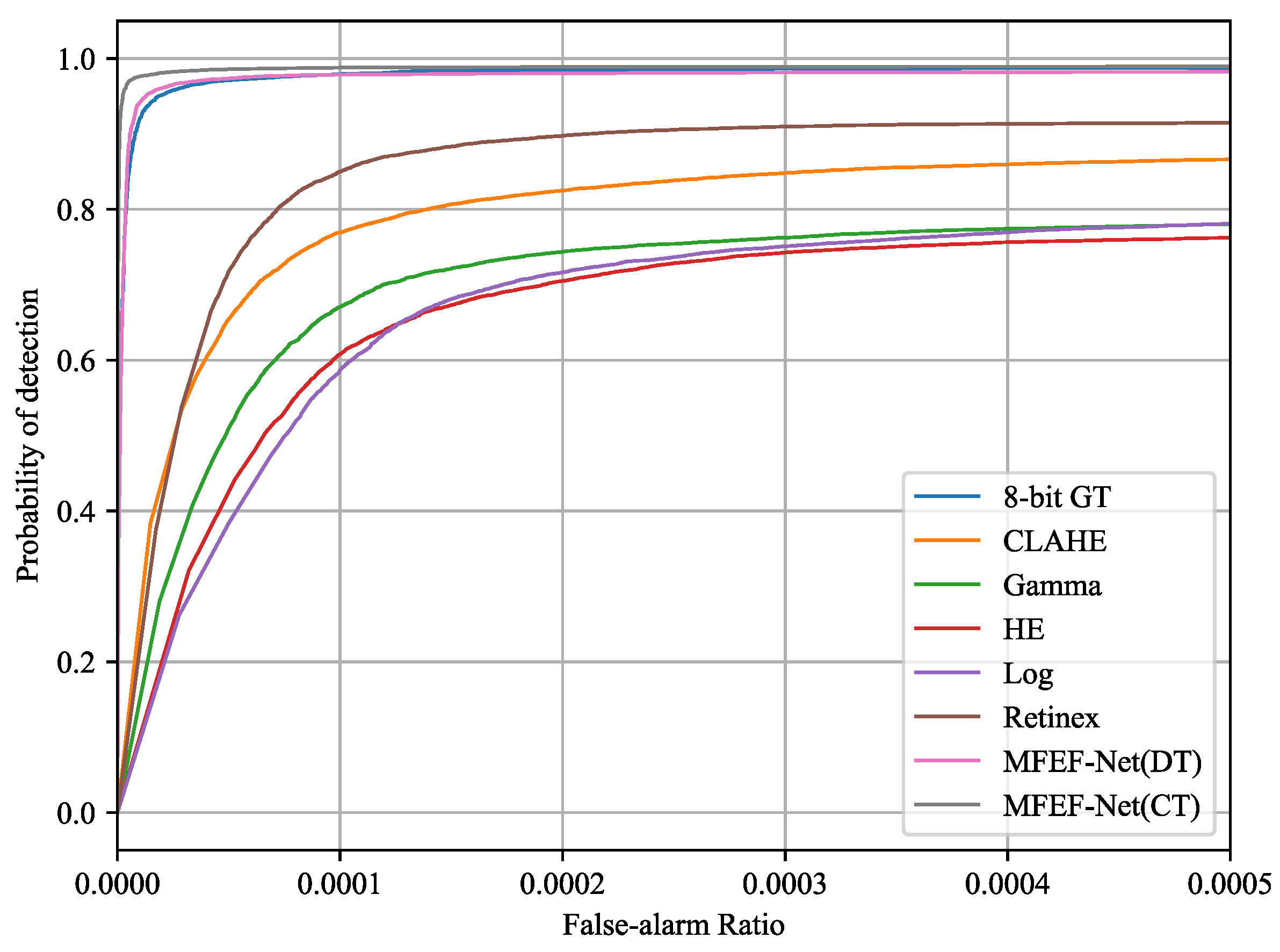

4.3.2. Impact of HDR Infrared Image Enhancement on Detection Tasks

4.4. Ablation Study

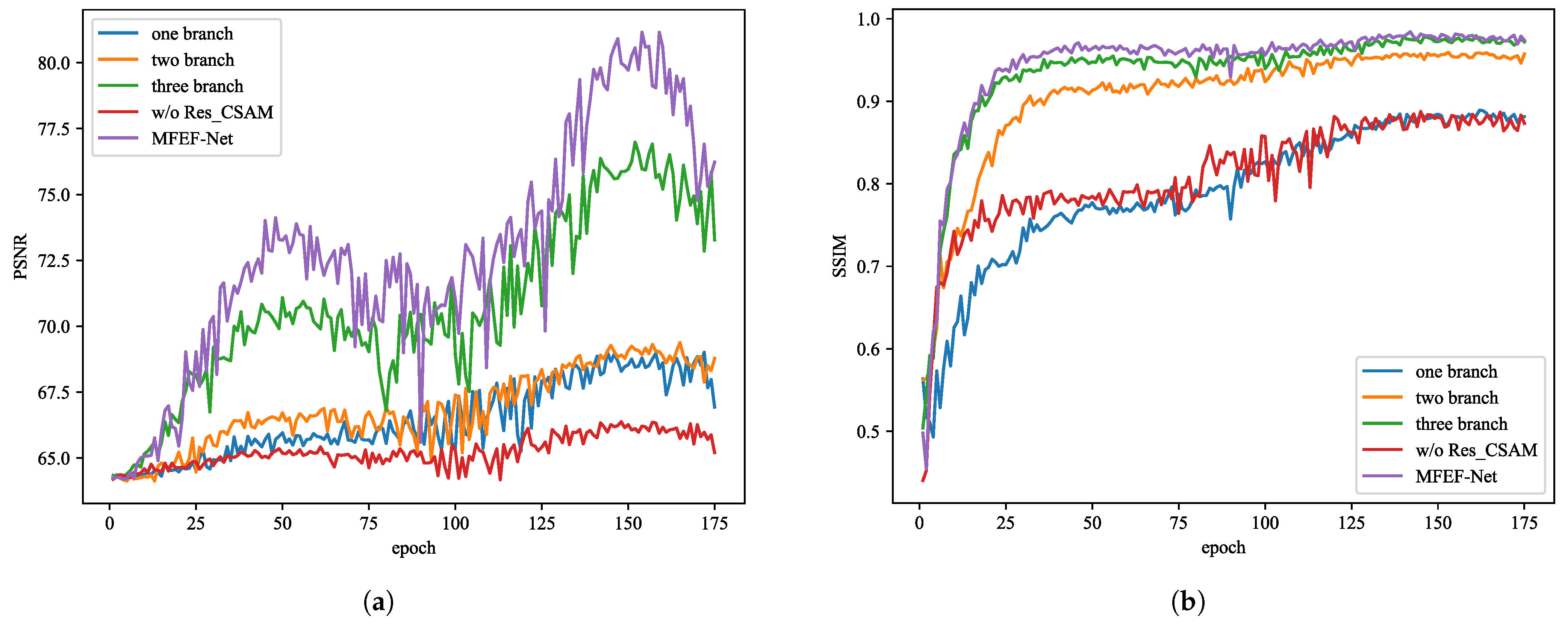

4.4.1. MFEF-Net Network Architecture Study

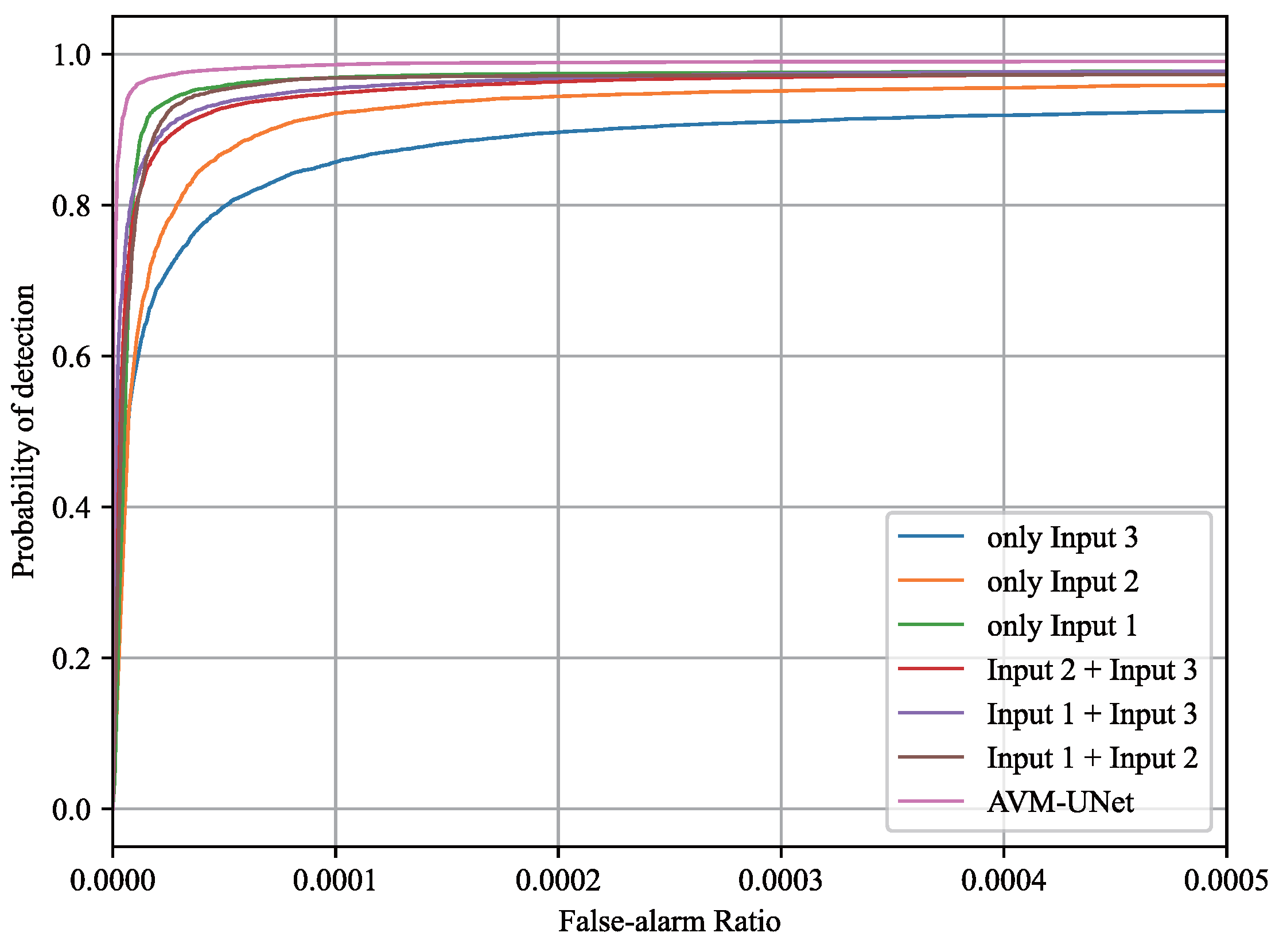

4.4.2. AVM-UNet Network Architecture Study

4.4.3. Effectiveness of Collaborative Optimization

4.5. Edge Device Verification and Compatibility Testing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GT | Ground Truth |

| HDR | High Dynamic Range |

| LDR | Low Dynamic Range |

| AGC | Automatic Gain Control |

| HE | Histogram Equalization |

| CLAHE | Adaptive Limitation Histogram Equalization |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index |

References

- Wang, K.; Wu, X.; Zhou, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Yang, L.; Li, Y. AFE-Net: Attention-Guided Feature Enhancement Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4208–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, K.J. Dynamic Range Compression for Visual Display of Thermal Infrared Imagery. In Imaging Systems and Applications; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Luo, H.B.; Li, F.Z. New technique for dynamic-range compression and contrast enhancement in infrared imaging systems. Hongwai yu Jiguang Gongcheng/Infrared Laser Eng. 2018, 47, 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y. High dynamic range infrared image compression and denoising. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Information Technology and Computer Application (ITCA), Guangzhou, China, 20–22 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, F. Real-time visualization of low contrast targets from high-dynamic range infrared images based on temporal digital detail enhancement filter. J. Electron. Imaging 2015, 24, 061103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peli, E. Contrast in complex images. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. 1990, 7, 2032–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers, V.E. Plateau equalization algorithm for real-time display of high-quality infrared imagery. Opt. Eng. 1996, 35, 1921–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, A.M. Realization of the contrast limited adaptive Download from Inspec Ondisc histogram equalization (CLAHE) for real-time image enhancement. J. VLSI Signal Process. Syst. Signal Image Video Technol. 2004, 38, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, H. Blind inverse gamma correction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2001, 10, 1428–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Myszkowski, K.; Annen, T.; Chiba, N. Adaptive Logarithmic Mapping For Displaying High Contrast Scenes. Comput. Graph. Forum 2003, 22, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, E.H.; McCann, J.J. Lightness and retinex theory. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1971, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.W.; Du, S.Y.; Liu, C.X.; Cao, Z.G. Interior Attention-Aware Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Y.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.G.; Wang, Y.Q.; Lin, Z.P.; Li, M.; An, W.; Guo, Y.L. Dense Nested Attention Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Hong, D.F.; Chanussot, J. UIU-Net: U-Net in U-Net for Infrared Small Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. FFDNet: Toward a Fast and Flexible Solution for CNN - Based Image Denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 4608–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, S.; Barnes, N. Real Image Denoising with Feature Attention. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3155–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Hwang, S.; Lee, S. Brightness-based convolutional neural network for thermal image enhancement. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 2169–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Chen, Q.; Liu, N. Display and detail enhancement for high-dynamic-range infrared images. Opt. Eng. 2011, 50, 127401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhao, D. Detail enhancement for high-dynamic-range infrared image based on guided image filter. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2014, 67, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ro, Y.M. Dual-Branch Structured De-Striping Convolution Network Using Parametric Noise Model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 155519–155528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Li, J.; Xiang, S. VM-UNet: Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.02491. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.02491 (accessed on 13 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021), Vienna, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jobson, D.J.; Rahman, Z.; Woodell, G.A. Properties and performance of a center/surround Retinex. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1997, 6, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobson, D.J.; Rahman, Z.; Woodell, G.A. A multi-scale Retinex for bridging the gap between color images and the human observation of scenes. Trans. Image Process. 1997, 6, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.Q.; Cao, J.Z.; Li, C. Infrared Image Enhancement Based on Adaptive Guided Filter and Global–Local Mapping. Photonics 2024, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.L.; Liao, X. Infrared Image Enhancement Algorithm Based on Detail Enhancement Guided Image Filtering. Vis. Comput. 2023, 39, 6491–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.F.; Dai, Y.M.; Chen, Y.H. Display Method for High Dynamic Range Infrared Image Based on Gradient Domain Guided Image Filter. Opt. Eng. 2024, 63, 013105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.Y.; Yu, X. Infrared and Visible Image Fusion Based on Saliency and Fast Guided Filtering. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 123, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.D.; Er, M.H.; Ronda, V.; Chan, P. Max-Mean and Max-Median filters for detection of small-targets. In Proceedings of the Conference on Signal and Data Processing of Small Targets 1999, Denver, CO, USA, 20–22 July 1999; pp. 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tom, V.T.; Peli, T.; Leung, M.; Bondaryk, J.E. Morphology-based algorithm for point target detection in infrared backgrounds. In Proceedings of the 5th Conf on Signal and Data Processing of Small Targets, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–14 April 1993; pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rivest, J.F.; Fortin, R. Detection of dim targets in digital infrared imagery by morphological image processing. Opt. Eng. 1996, 35, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J. Statistical analysis of median subtraction filtering with application to point target detection in infrared backgrounds. In Proceedings of the Infrared Systems and Components III, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 16–17 January 1989; Volume 1050, pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, M.; Ye, C.; Zhou, X. Small Infrared Target Detection Based on Weighted Local Difference Measure. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4204–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Liu, S.B.; Qin, G.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.H.; Li, N.N. A Local Contrast Method Combined With Adaptive Background Estimation for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1442–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Moradi, S.; Faramarzi, I.; Zhang, H.H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X.J.; Li, N. Infrared Small Target Detection Based on the Weighted Strengthened Local Contrast Measure. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.P.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.T.; Xia, T.; Tang, Y.Y. A Local Contrast Method for Small Infrared Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.T.; Lu, R.T.; Bi, H.X.; Li, Y.H. An Infrared Small Target Detection Method Based on Attention Mechanism. Sensors 2023, 23, 8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.F.; Wei, Y.T.; Yao, H.; Pan, D.H.; Xiao, G.R. High-Boost-Based Multiscale Local Contrast Measure for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, S.M.; Deng, L.Z.; Li, Y.S.; Xiao, F. Infrared Small Target Detection via Low-Rank Tensor Completion With Top-Hat Regularization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.J.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.L.; Yao, J.P. Infrared Target Tracking Based on Robust Low-Rank Sparse Learning. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.D.; Peng, L.B.; Zhang, T.F.; Cao, S.Y.; Peng, Z.M. Infrared Small Target Detection via Non-Convex Rank Approximation Minimization Joint l2.1 Norm. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.M.; Wu, Y.Q. Reweighted Infrared Patch-Tensor Model With Both Nonlocal and Local Priors for Single-Frame Small Target Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 3752–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.H.; Peng, L.B.; Yang, C.P.; Peng, Z.M. Infrared Small Target Detection Based on Non-Convex Optimization with Lp-Norm Constraint. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Peng, Z.M.; Wu, H.; He, Y.M.; Li, C.H.; Yang, C.P. Infrared small target detection via self-regularized weighted sparse model. Neurocomputing 2021, 420, 124–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.M.; Wu, Y.Q.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Attentional Local Contrast Networks for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 9813–9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.M.; Yu, C.; Shi, Z.L.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.D. Gradient-Guided Learning Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Li, L.; Cao, S.Y.; Pu, T.; Peng, Z.M. Attention-Guided Pyramid Context Networks for Detecting Infrared Small Target Under Complex Background. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 4250–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.Y.; Lee, I.H.; Park, C.G. Lightweight Infrared Small Target Detection Network Using Full-Scale Skip Connection U-Net. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.M.; Lin, L.F.; Tong, R.F.; Hu, H.J.; Zhang, Q.W.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.H.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, J. UNET 3+: A full-scale connected unet for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 1055–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.L.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.G.; Wang, Y.Q.; Yang, J.A.; An, W. RepISD-Net: Learning Efficient Infrared Small-Target Detection Network via Structural Re-Parameterization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zang, T.; Fu, Z.L.; Yang, H.; Du, W.L. RLPGB-Net: Reinforcement Learning of Feature Fusion and Global Context Boundary Attention for Infrared Dim Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, X. MambaOut: Do We Really Need Mamba for Vision? In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025.

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. VMamba: Visual State Space Model. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.00752. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2312.00752 (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00396. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2111.00396 (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Gu, A.; Johnson, I.; Goel, K.; Saab, K.; Dao, T.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. Combining recurrent, convolutional, and continuous-time models with linear state space layers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 572–585. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, T.; Gu, A. Transformers Are SSMs: Generalized Models and Efficient Algorithms Through Structured State Space Duality. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2024), Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; pp. 10041–10071. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2014, 106, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.; Meng, D.; Lin, Z. Investigating Bi-Level Optimization for Learning and Vision From a Unified Perspective: A Survey and Beyond. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 10045–10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ma, L.; Yuan, X.; Zeng, S.; Zhang, J. Task-Oriented Convex Bilevel Optimization with Latent Feasibility. IEEE Trans. Image Process. A Publ. IEEE Signal Process. Soc. 2022, 31, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, P.; Ranftl, R.; Brox, T.; Pock, T. Bilevel optimization with nonsmooth lower level problems. In Scale Space and Variational Methods in Computer Vision; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9087, pp. 654–665. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, W.; Cheng, S.; Arcucci, R.; Xiong, Z. Generative Text-Guided 3D Vision-Language Pretraining for Unified Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.04811. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.04811 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Asymmetric Contextual Modulation for Infrared Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV 2021), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.F.; Liu, M.Y.; Han, Z.X. Generation Method of High Dynamic Range Image from a Single Low Dynamic Range Image Based on Retinex Enhancement. J. Comput.-Aided Des. Comput. Graph. 2018, 30, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.W.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. HDRUNet: Single Image HDR Reconstruction with Denoising and Dequantization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 354–363. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Shao, H. Fast 3D Reconstruction of UAV Images Based on Neural Radiance Field. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.Y.; Wang, K.W.; Cao, Z.G. BPR-Net: Balancing Precision and Recall for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1711.05101. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05101 (accessed on 13 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic Gradient Descent with Warm Restarts. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2017), Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A. PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 8026–8037. [Google Scholar]

| Image1 | Image2 | Image3 | Image4 | Image5 | Image6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | |

| HE | 31.546 | 0.816 | 32.417 | 0.727 | 32.093 | 0.757 | 31.571 | 0.540 | 32.487 | 0.552 | 33.309 | 0.818 |

| CLAHE | 32.002 | 0.490 | 32.098 | 0.775 | 32.136 | 0.487 | 31.784 | 0.565 | 32.138 | 0.494 | 32.764 | 0.636 |

| Retinex | 32.679 | 0.919 | 32.032 | 0.851 | 32.891 | 0.768 | 32.165 | 0.750 | 32.150 | 0.882 | 32.469 | 0.805 |

| Gamma | 31.934 | 0.842 | 32.036 | 0.441 | 31.391 | 0.790 | 31.622 | 0.720 | 33.343 | 0.894 | 32.668 | 0.328 |

| Log | 32.684 | 0.926 | 31.694 | 0.507 | 31.676 | 0.930 | 31.819 | 0.760 | 31.912 | 0.909 | 31.881 | 0.272 |

| MFEF-Net(DT) | 31.282 | 0.986 | 31.604 | 0.973 | 31.687 | 0.940 | 31.087 | 0.935 | 31.671 | 0.957 | 35.411 | 0.918 |

| MFEF-Net(CT) | 31.291 | 0.978 | 32.078 | 0.970 | 31.616 | 0.939 | 31.544 | 0.945 | 31.657 | 0.954 | 33.470 | 0.952 |

| IAA-Net | RepISD-Net | DNA-Net(Res18) | UIU-Net | AMFU-Net | AVM-UNet(DT) | AVM-UNet(CT) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NUDT-SIRST Dataset | mIoU | 0.8821 | 0.8795 | 0.8428 | 0.8972 | 0.8346 | 0.9102 | 0.9326 |

| Pd | 0.9591 | 0.9438 | 0.9178 | 0.9223 | 0.8979 | 0.9579 | 0.9766 | |

| Fa | 8.4898 | 8.8168 | 11.7882 | 7.7097 | 12.6716 | 6.4878 | 4.7784 | |

| SIRST Dataset | mIoU | 0.6989 | 0.6869 | 0.7424 | 0.7175 | 0.7661 | 0.7867 | 0.8225 |

| Pd | 0.8312 | 0.8998 | 0.8240 | 0.9090 | 0.8502 | 0.8922 | 0.9026 | |

| Fa | 12.8292 | 13.8958 | 17.5253 | 11.1255 | 15.4810 | 11.0663 | 7.9553 | |

| Image size 256 × 256 | FLOPs | 438.35 | 7.09 | 14.28 | 54.50 | 5.95 | 1.65 | 43.19 |

| Params | 18.250 | 0.310 | 4.697 | 50.545 | 0.473 | 6.353 | 6.988 | |

| FPS | 48.87 | 332.98 | 127.38 | 91.01 | 200.24 | 191.75 | 109.96 |

| Method | mIoU | Pd | Fa () |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8-bit GT | 0.9102 | 0.9579 | 6.4878 |

| HE | 0.2632 | 0.6967 | 57.7137 |

| CLAHE | 0.2739 | 0.7428 | 55.6372 |

| Retinex | 0.4446 | 0.8109 | 42.9712 |

| Gamma | 0.3978 | 0.7511 | 48.1053 |

| Log | 0.3695 | 0.7254 | 50.8358 |

| MFEF-Net(DT) | 0.9271 | 0.9716 | 5.1914 |

| MFEF-Net(CT) | 0.9326 | 0.9766 | 4.7784 |

| MFEF-Net Model (DT) | Params(M) | mIoU | Pd | Fa () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| one branch | 0.188 | 0.4533 | 0.8233 | 42.0075 |

| two branch | 0.337 | 0.8488 | 0.9249 | 11.2605 |

| three branch | 0.486 | 0.9047 | 0.9621 | 6.8550 |

| w/o Res_CSAM | 0.335 | 0.8781 | 0.9431 | 8.9258 |

| MFEF-Net | 0.635 | 0.9271 | 0.9716 | 5.1914 |

| AVM-UNet Model (DT) | Params(M) | mIoU | Pd | Fa () | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| only Input 3 | 5.628 | 0.7239 | 0.8219 | 22.3814 | 217.27 |

| only Input 2 | 1.420 | 0.7542 | 0.8584 | 19.1915 | 219.02 |

| only Input 1 | 0.3616 | 0.8156 | 0.8921 | 14.1861 | 222.43 |

| Input 2 + Input 3 | 6.349 | 0.8679 | 0.9381 | 9.7174 | 207.73 |

| Input 1 + Input 3 | 6.339 | 0.8780 | 0.9457 | 8.9086 | 213.64 |

| Input 1 + Input 2 | 1.597 | 0.8973 | 0.9483 | 7.4860 | 212.18 |

| AVM-UNet | 6.353 | 0.9102 | 0.9579 | 6.4878 | 191.75 |

| Model | Params(M) | FLOPs(G) | Inference Latency (ms) | FPS | Power (W) | Memory (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RepISD-Net | 0.310 | 7.09 | 7.4 | 135.14 | 10 | 371 |

| AMFU-Net | 0.473 | 5.95 | 15.6 | 64.10 | 7 | 374 |

| AVM-UNet | 6.353 | 1.65 | 7.9 | 126.58 | 8 | 398 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, F.; Chen, P.; Zhao, W.; Wang, W. HDR-IRSTD: Detection-Driven HDR Infrared Image Enhancement and Small Target Detection Based on HDR Infrared Image Enhancement. Automation 2025, 6, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040086

Guo F, Chen P, Zhao W, Wang W. HDR-IRSTD: Detection-Driven HDR Infrared Image Enhancement and Small Target Detection Based on HDR Infrared Image Enhancement. Automation. 2025; 6(4):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040086

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Fugui, Pan Chen, Weiwei Zhao, and Weichao Wang. 2025. "HDR-IRSTD: Detection-Driven HDR Infrared Image Enhancement and Small Target Detection Based on HDR Infrared Image Enhancement" Automation 6, no. 4: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040086

APA StyleGuo, F., Chen, P., Zhao, W., & Wang, W. (2025). HDR-IRSTD: Detection-Driven HDR Infrared Image Enhancement and Small Target Detection Based on HDR Infrared Image Enhancement. Automation, 6(4), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040086