Comparative Study of Voltage Amplification in Cylindrical FE-FE-DE and FE-DE Heterostructures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

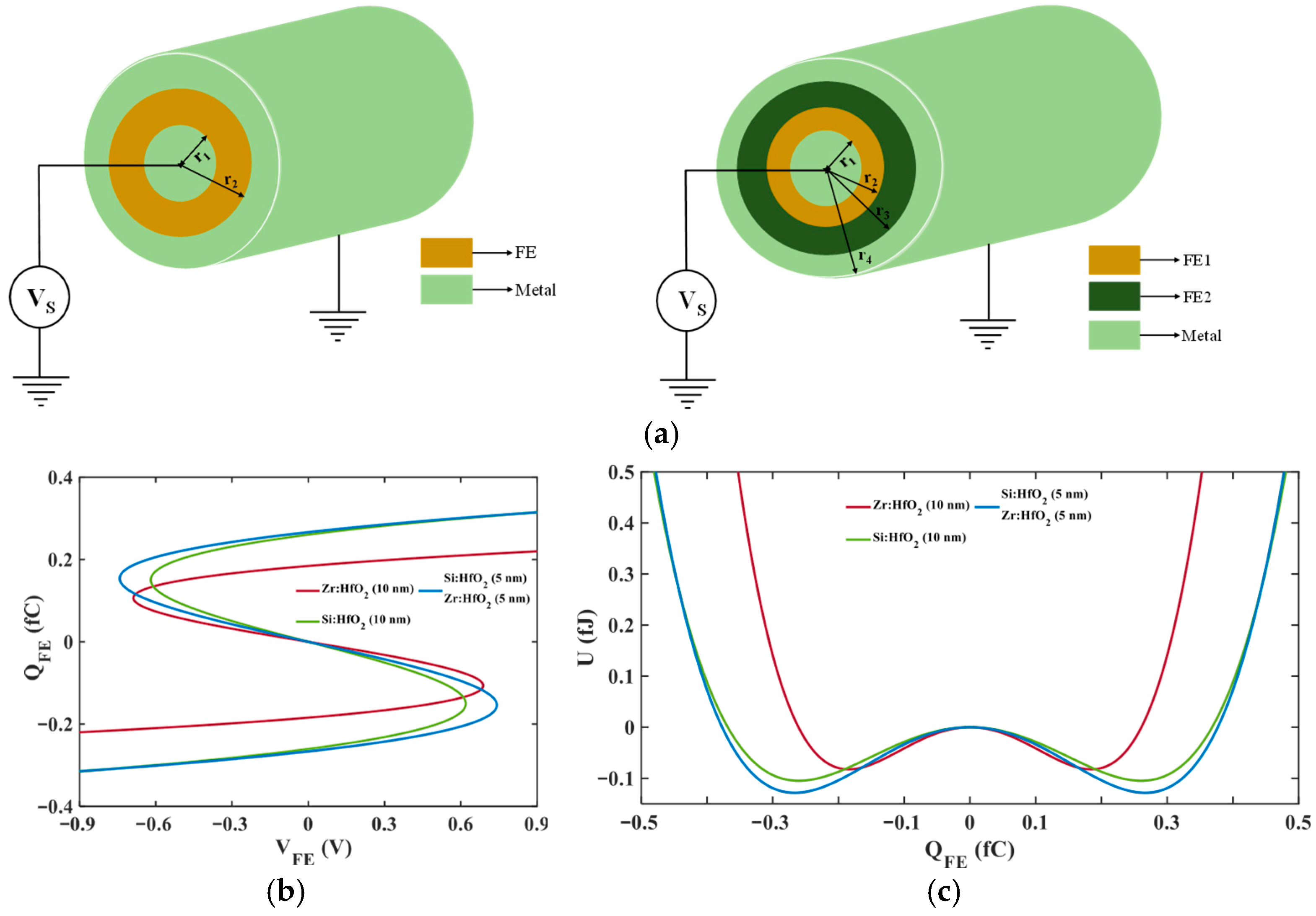

2.1. An Isolated Cylindrical FE Capacitor

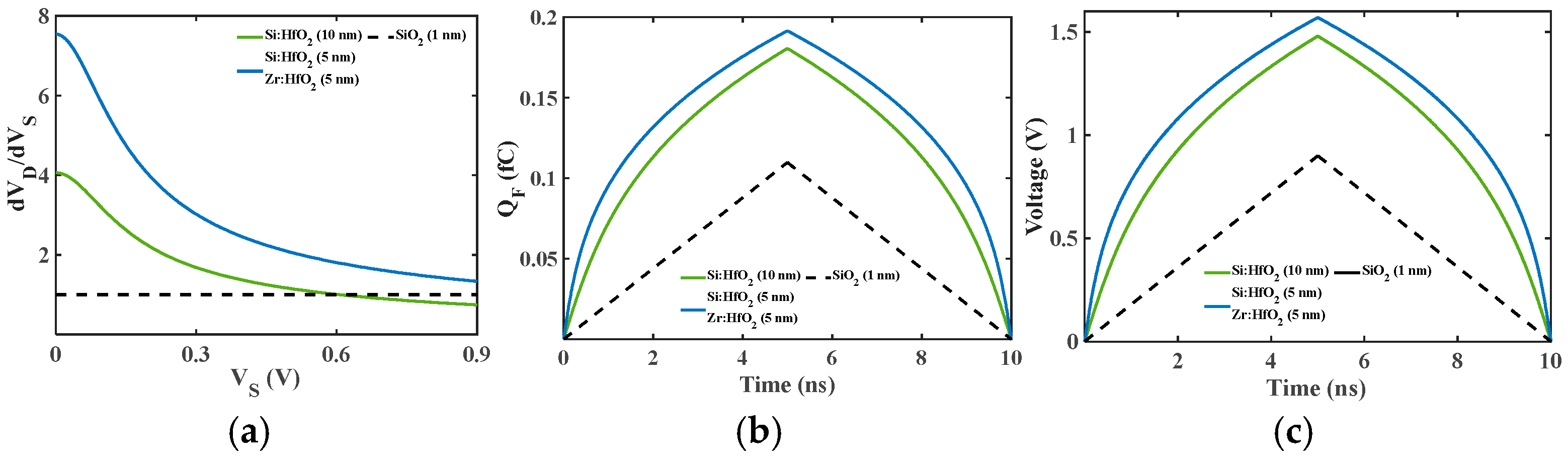

2.2. Cylindrical FE-DE and FE-FE-DE Heterostructure

2.3. Dynamic Response of Cylindrical Heterostructure

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Awadhiya, B.; Kondekar, P.N.; Meshram, A.D. Analogous behavior of FE-DE heterostructure at room temperature and ferroelectric capacitor at Curie temperature. Superlattices Microstruct. 2018, 123, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, B.; Babu, T.; Choudhary, R.N.P. Review on Different Preparation Techniques of Lead Zirconate Titanate. Int. Res. J. Adv. Sci. Hub 2020, 2, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, C.R.; Kim, H.A.; Weaver, P.M.; Dunn, S. Piezoelectric and ferroelectric materials and structures for energy harvesting applications. Energy Env. Sci. 2014, 7, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadhiya, B.; Kondekar, P.N.; Yadav, S.; Upadhyay, P.; Jaisawal, R.K.; Rathore, S. Effect of Scaling on Passive Voltage Amplification in FE-DE Hetero Structure. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Control, Automation, Power and Signal Processing (CAPS), Jabalpur, India, 10–12 December 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, A.C.M.; Nanjappa, Y. Comparative investigation of passive voltage amplification in ferroelectric-dielectric heterostructure. J. Phys. Commun. 2024, 8, 085003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Gupta, R.; Priyanka; Singh, R.; Bhalla, S.K. Design and Simulation-Based Analysis of Triple Metal Gate with Ferroelectric-SiGe Heterojunction Based Vertical TFET for Performance Enhancement. Silicon 2022, 14, 11015–11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Hiramoto, T. On device design for steep-slope negative-capacitance field-effect-transistor operating at sub-0.2V supply voltage with ferroelectric HfO2 thin film. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 025113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnesh, R.K.; Goel, A.; Kaushik, G.; Garg, H.; Chandan; Singh, M.; Prasad, B. Advancement and challenges in MOSFET scaling. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 134, 106002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S.B.; Tayal, S.; Upadhyay, A.K. A review on emerging negative capacitance field effect transistor for low power electronics. Microelectron. J. 2021, 116, 105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Gupta, D.; Mishra, H.; Nandan, D.; Qamar, S. Beyond Si-Based CMOS Devices: Needs, Opportunities, and Challenges. In Beyond Si-Based CMOS Devices: Materials to Architecture; Singh, S., Sharma, S.K., Nandan, D., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 3–25. ISBN 978-981-9746-23-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, M.T.; Young, I.A. CMOS Scaling Trends and Beyond. IEEE Micro 2017, 37, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadhiya, B.; Yadav, S. Comparative study of Negative Capacitance Field Effect Transistors with different doped hafnium oxides. Microelectron. J. 2023, 138, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Alam, M.A. Stability Constraints Define the Minimum Subthreshold Swing of a Negative Capacitance Field-Effect Transistor. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2014, 61, 2235–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, S.-W. Application of ferroelectric materials for improving output power of energy harvesters. Nano Converg. 2018, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.T.; Zhang, C.; Fu, Y.S. Ferroelectric/piezoelectric materials and their applications in advanced sciences and technologies. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2005, 19, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.I. On the Microscopic Origin of Negative Capacitance in Ferroelectric Materials: A Toy Model. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 1–5 December 2018; pp. 9.3.1–9.3.4. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, A.K.; Chand, P. Ferroelectrics: Principles and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-3-527-80540-2. [Google Scholar]

- Haertling, G.H. Ferroelectric Ceramics: History and Technology. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999, 82, 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.I.; Chatterjee, K.; Wang, B.; Drapcho, S.; You, L.; Serrao, C.; Bakaul, S.R.; Ramesh, R.; Salahuddin, S. Negative capacitance in a ferroelectric capacitor. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.I.; Radhakrishna, U.; Chatterjee, K.; Salahuddin, S.; Antoniadis, D.A. Negative Capacitance Behavior in a Leaky Ferroelectric. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2016, 63, 4416–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Yadav, S.; Rewari, S.; Nand, D. Computational modelling of cylindrical-ferroelectric-dual metal-nanowire field effect transistor (C-FE-DM-NW FET) using landau equation for gate leakage minimization. Micro Nanostructures 2024, 191, 207851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Deng, Y.; Duan, R.; Chen, J.; Zeng, Q.; Zhou, J.; Fu, Q.; You, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Van der Waals engineering of ferroelectric heterostructures for long-retention memory. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.I.; Radhakrishna, U.; Salahuddin, S.; Antoniadis, D. Work Function Engineering for Performance Improvement in Leaky Negative Capacitance FETs. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2017, 38, 1335–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairaj, S.; Singh, A. Compact Model for a Negative Capacitance-Based Top-Gated Carbon-Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor. J. Electron. Mater. 2024, 53, 2135–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, B. Comparative Study of Single and Double Gate All Around Cylindrical FET Structures for High-K Dielectric Materials. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2021, 22, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, H.M.; Smith, C.E.; Rojas, J.P.; Hussain, M.M. Silicon Nanotube Field Effect Transistor with Core–Shell Gate Stacks for Enhanced High-Performance Operation and Area Scaling Benefits. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4393–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. Analysis of drain induced barrier lowering for junctionless double gate MOSFET using ferroelectric negative capacitance effect. AIMS Electron. Electr. Eng. 2022, 7, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekleab, D. Device Performance of Silicon Nanotube Field Effect Transistor. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2014, 35, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadhiya, B.; Kondekar, P.N.; Meshram, A.D. Investigating Undoped HfO2 as Ferroelectric Oxide in Leaky and Non-Leaky FE–DE Heterostructure. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2019, 20, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajick, T.; Slesazeck, S.; Mulaosmanovic, H.; Park, M.H.; Fichtner, S.; Lomenzo, P.D.; Hoffmann, M.; Schroeder, U. Next generation ferroelectric materials for semiconductor process integration and their applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvika; Choudhuri, B.; Mummaneni, K. A new pocket-doped NCFET for low power applications: Impact of ferroelectric and oxide thickness on its performance. Micro Nanostructures 2022, 169, 207360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, L.E. Ferroelectric materials for electromechanical transducer applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 1996, 43, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.; Samajdar, D.P. Recent Advances in Negative Capacitance FinFETs for Low-Power Applications: A Review. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2021, 68, 3056–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C.; Salahuddin, S. Negative Capacitance Transistors. Proc. IEEE 2019, 107, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valasa, S.; Kotha, V.R.; Vadthiya, N. Beyond Moore’s law—A critical review of advancements in negative capacitance field effect transistors: A revolution in next-generation electronics. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 173, 108116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Moon, T.; Kim, K.D.; Müller, J.; Kersch, A.; Schroeder, U.; Mikolajick, T.; et al. Ferroelectricity and Antiferroelectricity of Doped Thin HfO2-Based Films. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 1811–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahuddin, S.; Datta, S. Use of Negative Capacitance to Provide Voltage Amplification for Low Power Nanoscale Devices. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, P.; Nanjappa, Y.; Mishra, V.; Kumar, S.; Awadhiya, B. Negative Capacitance Behavior in Cylindrical Ferroelectric-Dielectric Heterostructure. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FE Material | ||

|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suresh, P.; Awadhiya, B.; Mishra, V.; Martha, P.; Kumar, S.; Nanjappa, Y. Comparative Study of Voltage Amplification in Cylindrical FE-FE-DE and FE-DE Heterostructures. Electron. Mater. 2025, 6, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040021

Suresh P, Awadhiya B, Mishra V, Martha P, Kumar S, Nanjappa Y. Comparative Study of Voltage Amplification in Cylindrical FE-FE-DE and FE-DE Heterostructures. Electronic Materials. 2025; 6(4):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040021

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuresh, Pratheeksha, Bhaskar Awadhiya, Vikash Mishra, Pramod Martha, Sampath Kumar, and Yashwanth Nanjappa. 2025. "Comparative Study of Voltage Amplification in Cylindrical FE-FE-DE and FE-DE Heterostructures" Electronic Materials 6, no. 4: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040021

APA StyleSuresh, P., Awadhiya, B., Mishra, V., Martha, P., Kumar, S., & Nanjappa, Y. (2025). Comparative Study of Voltage Amplification in Cylindrical FE-FE-DE and FE-DE Heterostructures. Electronic Materials, 6(4), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040021