The Role of the Setting in Controlling Anxiety and Pain During Outpatient Operative Hysteroscopy: The Experience of a Hysteroscopy Unit in North Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Age over 18 years

- Clinical indication for operative hysteroscopy (e.g., endometrial polyps, submucosal fibroids, intrauterine adhesions, uterine septa)Exclusion criteria

- Contraindications for outpatient hysteroscopy

- Need for general anesthesia due to clinical reasons

- Soft lighting

- Background relaxing music

- Reduced environmental noise

- Presence of a healthcare assistant dedicated to emotional support

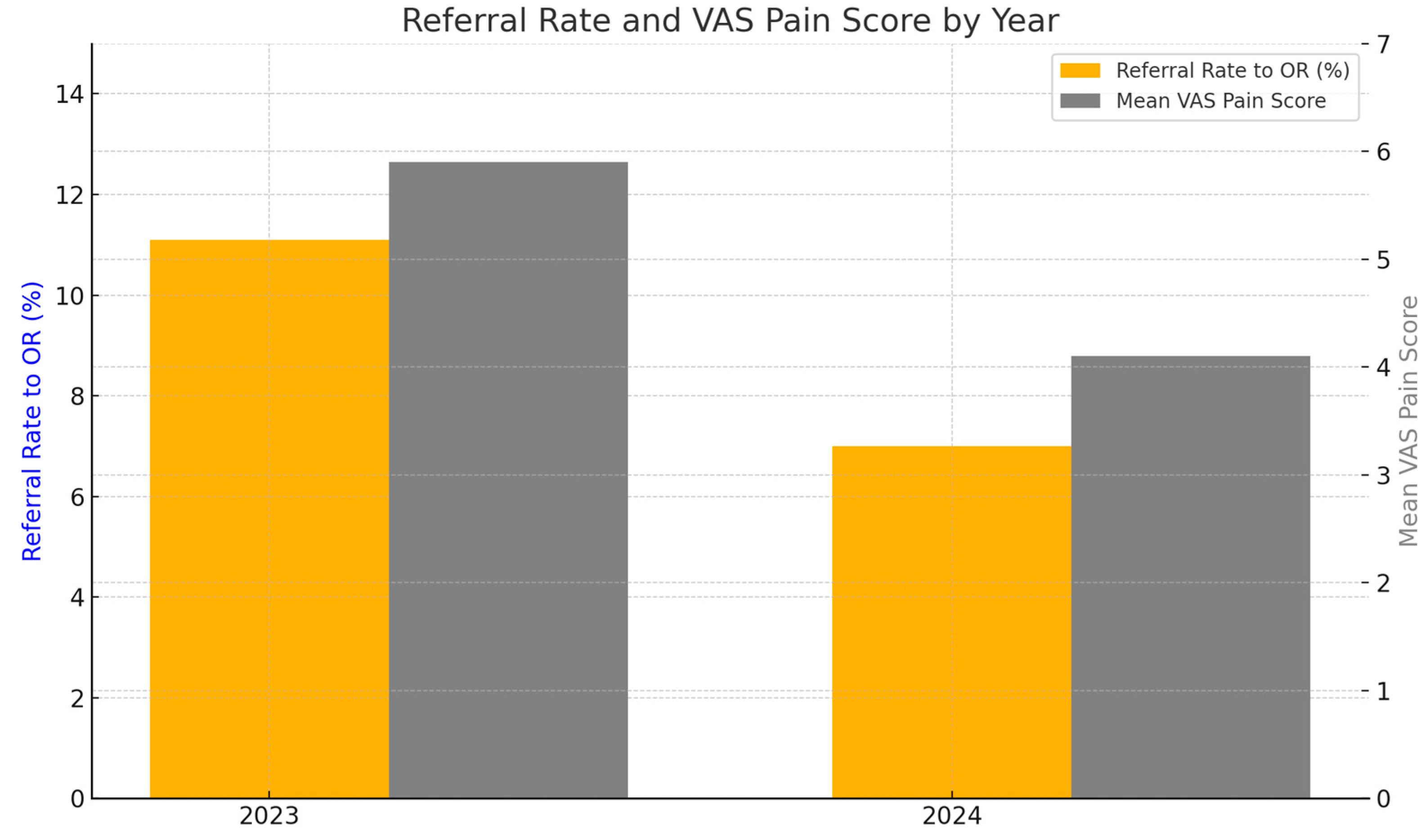

- Referral rate to the operating room (OR) to complete the procedure, considered as an indicator of outpatient hysteroscopy failureSecondary outcome

- Perceived pain assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) in a representative subgroup of 200 patients per year. Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores were recorded for consecutive patients during each study year; the VAS subsample therefore represents an unselected, consecutive series of routine clinical cases.Statistical AnalysisThe collected data were analyzed using appropriate statistical software.Analysis of categorical variablesTo compare the referral rate to the operating room between 2023 and 2024:

- A Chi-square (χ2) test was used when cell counts met the assumptions for the test

- Fisher’s exact test was applied in case of expected frequencies below 5 (though, with 52/470 vs. 35/500, the chi-square test was appropriate)Analysis of continuous variablesTo compare mean VAS pain scores (continuous variables) between groups:

- Normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test or graphical methods (histograms, Q-Q plots)

- If data were normally distributed: Student’s t-test for independent samples was used

- If not normally distributed: Mann–Whitney U test was applied

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Primary Outcome: Referral to Operating Room

3.3. Secondary Outcome: Perceived Pain

3.4. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campo, R.; Santangelo, F.; Gordts, S.; Di Cesare, C.; Van Kerrebroeck, H.; De Angelis, M.C.; Sardo, A.D.S. Outpatient hysteroscopy. Facts Views Vis. ObGyn 2018, 10, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Centini, G.; Troia, L.; Lazzeri, L.; Petraglia, F.; Luisi, S. Modern operative hysteroscopy. Minerva Ginecol. 2016, 68, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.; Readman, E.; Hicks, L.; Porter, J.; Cameron, M.; Ellett, L.; Mcilwaine, K.; Manwaring, J.; Maher, P. Is outpatient hysteroscopy the new gold standard? Results from an 11 year prospective observational study. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 57, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.; Lepage, C.; Thavorn, K.; Fergusson, D.; Murnaghan, O.; Coyle, D.; Singh, S.S. Effectiveness of Outpatient Versus Operating Room Hysteroscopy for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Uterine Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Obs. Gynaecol Can. 2019, 41, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, A.; Nichols, A. The Value of Hysteroscopy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1994, 34, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, P.M.; Smith, P.P.; Cooper, N.A.M.; Clark, T.J. Outpatient Hysteroscopy: (Green-top Guideline no. 59). Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 131, e86–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemma, G.; Schiattarella, A.; Colacurci, N.; Vitale, S.G.; Cianci, S.; Cianci, A.; De Franciscis, P. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain relief for office hysteroscopy: An up-to-date review. Climacteric 2020, 23, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soysal, C.; Ince, O.; Taşçı, Y. The effect of cervical length on procedure time and VAS pain score in office hysteroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambadauro, P.; Navaratnarajah, R.; Carli, V. Anxiety at outpatient hysteroscopy. Gynecol. Surg. 2015, 12, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo, R.; Molinas, C.R.; Rombauts, L.; Mestdagh, G.; Lauwers, M.; Braekmans, P.; Brosens, I.; Van Belle, Y.; Gordts, S. Prospective multicentre randomized controlled trial to evaluate factors influencing the success rate of office diagnostic hysteroscopy. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, G.; Palermo, P.; Marinangeli, F.; Piroli, A.; Necozione, S.; De Lellis, V.; Patacchiola, F. Waiting Time and Pain During Office Hysteroscopy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2012, 19, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, F.; Petito, A.; Angioni, S.; D’Antonio, F.; Severo, M.; Solazzo, M.C.; Tinelli, R.; Nappi, L. Impact of anxiety levels on the perception of pain in patients undergoing office hysteroscopy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingiloglu, P.; Mooney, S.; McNamara, H.; Wong, A.; Hicks, L.; Ellett, L.; Readman, E. Pain experience with outpatient hysteroscopy: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 300, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokanali, M.K.; Cavkaytar, S.; Guzel, A.I.; Topçu, H.O.; Eroğlu, E.; Aksakal, O.; Doğanay, M. Impact of preprocedural anxiety levels on pain perception in patients undergoing office hysteroscopy. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2014, 77, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Caruso, S.; Ciebiera, M.; Török, P.; Tesarik, J.; Vilos, G.A.; Cholkeri-Singh, A.; Gulino, F.A.; Kamath, M.S.; Cianci, A. Management of anxiety and pain perception in women undergoing office hysteroscopy: A systematic review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, J.K.; Clark, T.J.; More, S.; Pattison, H. Patient anxiety and experiences associated with an outpatient “one-stop” “see and treat” hysteroscopy clinic. Surg. Endosc. Other Interv. Tech. 2004, 18, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer-Cuenca, J.J.; Marín-Buck, A.; Vitale, S.G.; La Rosa, V.L.; Caruso, S.; Cianci, A.; Lisón, J.F. Non-pharmacological pain control in outpatient hysteroscopies. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2020, 29, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, G.; Saluja, S.; O’Flynn, H.; Sorrentino, A.; Leach, D.; Watson, A. Pain relief for outpatient hysteroscopy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 10, CD007710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzaccarini, G.; Alonso Pacheco, L.; Vitagliano, A.; Haimovich, S.; Chiantera, V.; Török, P.; Vitale, S.G.; Laganà, A.S.; Carugno, J. Pain Management during Office Hysteroscopy: An Evidence-Based Approach. Medicina 2022, 58, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, P.M.; Mahmud, A.; Smith, P.P.; Clark, T.J. Analgesia for Office Hysteroscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipari, G.; Messina, A.; Teston, C.; Alessi, P.; Mariani, A.; Bruno, T.; Florio, F.; Vegro, S.; Leo, L.; Masturzo, B. Combined Treatment of Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation Using a 16 Fr Miniresectoscope in an Office Setting Without Anesthesia: A Case Report. Case Rep. Obs. Gynecol. 2024, 2024, 9216109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Alonso Pacheco, L.; Haimovich, S.; Riemma, G.; De Angelis, M.C.; Carugno, J.; Lasmar, R.B.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A. Pain management for in-office hysteroscopy. A practical decalogue for the operator. J. Gynecol. Obs. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 101976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyendo, T.O.; Uwajeh, P.C.; Ikenna, E.S. The therapeutic impacts of environmental design interventions on wellness in clinical settings: A narrative review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pr. 2016, 24, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, L.D.; Allen, R.H. Pain management for gynecologic procedures in the office. Obs. Gynecol. Surv. 2016, 71, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruben, M.A.; Meterko, M.; Bokhour, B.G. Do patient perceptions of provider communication relate to experiences of physical pain? Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistiaen, P.; Van Osch, M.; Van Vliet, L.; Howick, J.; Bishop, F.L.; Di Blasi, Z.; Bensing, J.; van Dulmen, S. The effect of patient-practitioner communication on pain: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pain 2016, 20, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.; Purdy, M.; Stewart, E.A.; Cutshall, S.M.; Hathcock, M.A.; Mahapatra, S.; Bauer, B.A.; Ainsworth, A.J. Lavender Aromatherapy to Reduce Anxiety During Intrauterine Insemination: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2021, 10, 21649561211059070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-ElGawad, M.; Abdelsattar, N.K.; Kamel, M.A.; Sabri, Y.A.; Fathy, E.M.; El-Moez, N.A.; Abdellatif, Y.S.; Metwally, A.A. The effect of music intervention in decreasing pain and anxiety during outpatient hysteroscopy procedure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.; Nasra, L.A.; Paz, M.; Kaufman, Y.; Lavie, O.; Zilberlicht, A. Pain and anxiety management with virtual reality for office hysteroscopy: Systemic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baradwan, S.; Alshahrani, M.S.; AlSghan, R.; Alyafi, M.; Elsayed, R.E.; Abdel-Hakam, F.A.; Moustafa, A.A.; Hussien, A.E.; Yahia, O.S.; Shama, A.A.; et al. The effect of virtual reality on pain and anxiety management during outpatient hysteroscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioli, R.; De Cicco Nardone, C.; Plotti, F.; Cafà, E.V.; Dugo, N.; Damiani, P.; Moustafa, A.A.; Hussien, A.E.; Yahia, O.S.; Shama, A.A.; et al. Use of Music to Reduce Anxiety during Office Hysteroscopy: Prospective Randomized Trial. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014, 21, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, S.; Fatima, R.; Jena, S.; Kar, A.K.; Durga, P.; Neeradi, V.K. Effect of stress on contextual pain sensitivity in the preoperative period—A proof of concept study. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 39, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannibal, K.E.; Bishop, M.D. Chronic Stress, Cortisol Dysfunction, and Pain: A Psychoneuroendocrine Rationale for Stress Management in Pain Rehabilitation. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampalona, J.R.; Vega Moreno, D.; Degollada Bastos, M.; Guerra Garcia, À.; Mateu Pruñonosa, J.C.; Bresco Torras, P. Influence of Emotional Status on the Pain During The Outpatient Hysteroscopy. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, T.; Fung, Y.; Al-Kufaishi, A.; Clifford, K.; Quinn, S. Does virtual reality technology reduce pain and anxiety during outpatient hysteroscopy? A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 130, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, H.Y.; Ng, D.Y.T.; Chung, C.D. Use of music in reducing pain during outpatient hysteroscopy: Prospective randomized trial. J. Obs. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, U. The Anxiety-and Pain-Reducing Effects of Music Interventions: A Systematic Review. AORN J. 2008, 87, 780–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leardi, S.; Pietroletti, R.; Angeloni, G.; Necozione, S.; Ranalletta, G.; Del Gusto, B. Randomized clinical trial examining the effect of music therapy in stress response to day surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2007, 94, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Moscrop, A.; Mebius, A.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lewith, G.; Bishop, F.L.; Mistiaen, P.; Roberts, N.W.; Dieninytė, E.; Hu, X.Y.; et al. Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. R. Soc. Med. 2018, 111, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libretti, A.; Vitale, S.G.; Saponara, S.; Corsini, C.; Aquino, C.I.; Savasta, F.; Tizzoni, E.; Troìa, L.; Surico, D.; Angioni, S.; et al. Hysteroscopy in the new media: Quality and reliability analysis of hysteroscopy procedures on YouTube™. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moawad, N.S.; Santamaria, E.; Johnson, M.; Shuster, J. Cost-effectiveness of office hysteroscopy for abnormal uterine bleeding. J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2014, 18, e2014.00393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Messina, A.; Massaro, A.; Dalmasso, E.; Giovannini, I.; Lipari, G.; Alessi, P.; Bruno, T.; Vegro, S.; Caronia, D.; Savasta, F.; et al. The Role of the Setting in Controlling Anxiety and Pain During Outpatient Operative Hysteroscopy: The Experience of a Hysteroscopy Unit in North Italy. Reprod. Med. 2025, 6, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6030025

Messina A, Massaro A, Dalmasso E, Giovannini I, Lipari G, Alessi P, Bruno T, Vegro S, Caronia D, Savasta F, et al. The Role of the Setting in Controlling Anxiety and Pain During Outpatient Operative Hysteroscopy: The Experience of a Hysteroscopy Unit in North Italy. Reproductive Medicine. 2025; 6(3):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6030025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMessina, Alessandro, Alessio Massaro, Eleonora Dalmasso, Ilaria Giovannini, Giovanni Lipari, Paolo Alessi, Tiziana Bruno, Sofia Vegro, Daniela Caronia, Federica Savasta, and et al. 2025. "The Role of the Setting in Controlling Anxiety and Pain During Outpatient Operative Hysteroscopy: The Experience of a Hysteroscopy Unit in North Italy" Reproductive Medicine 6, no. 3: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6030025

APA StyleMessina, A., Massaro, A., Dalmasso, E., Giovannini, I., Lipari, G., Alessi, P., Bruno, T., Vegro, S., Caronia, D., Savasta, F., Remorgida, V., Libretti, A., & Masturzo, B. (2025). The Role of the Setting in Controlling Anxiety and Pain During Outpatient Operative Hysteroscopy: The Experience of a Hysteroscopy Unit in North Italy. Reproductive Medicine, 6(3), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6030025