Decidual Vasculopathy and Spiral Artery Remodeling Revisited III: Hypoxia and Re-oxygenation Sequence with Vascular Regeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

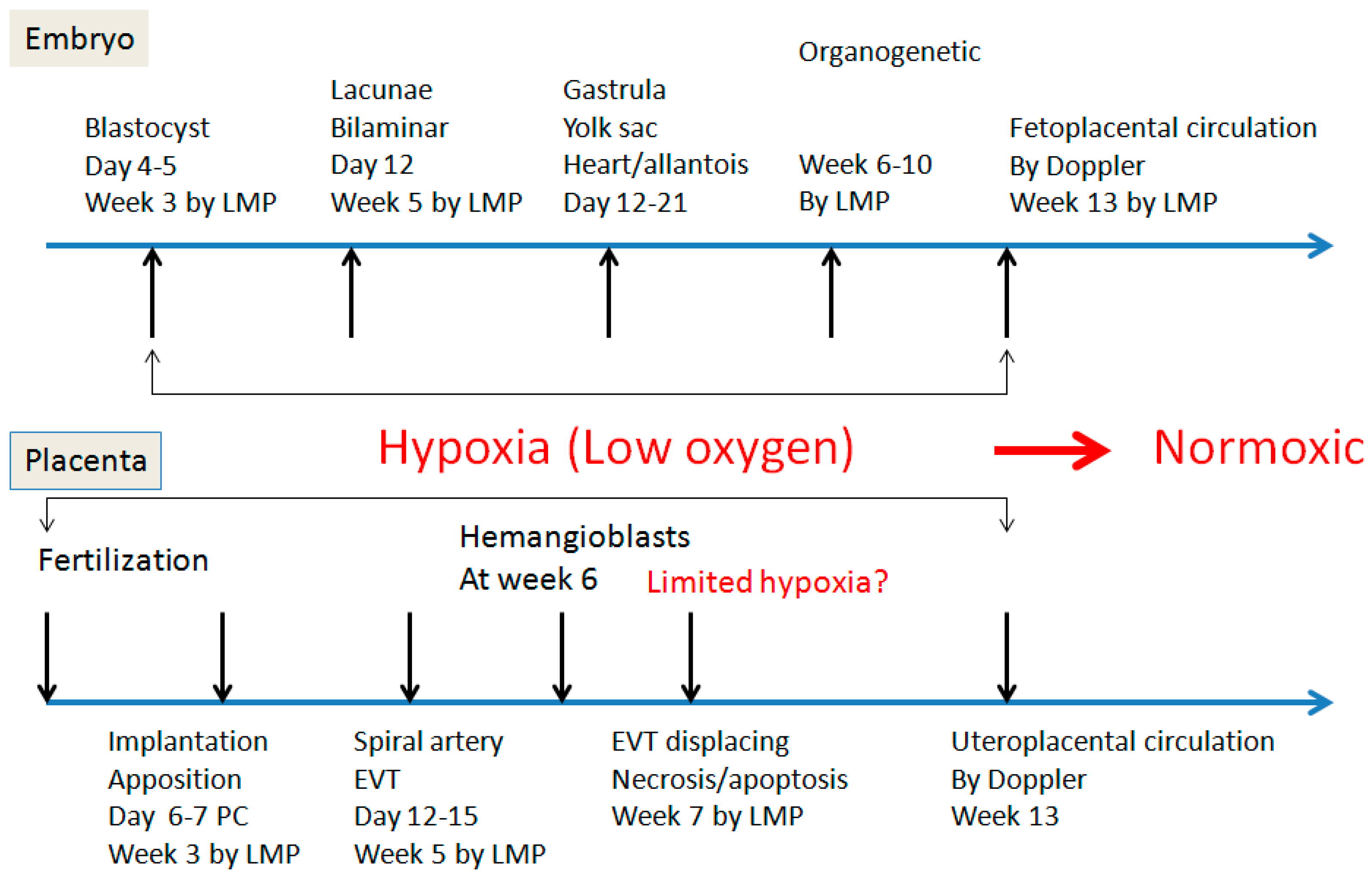

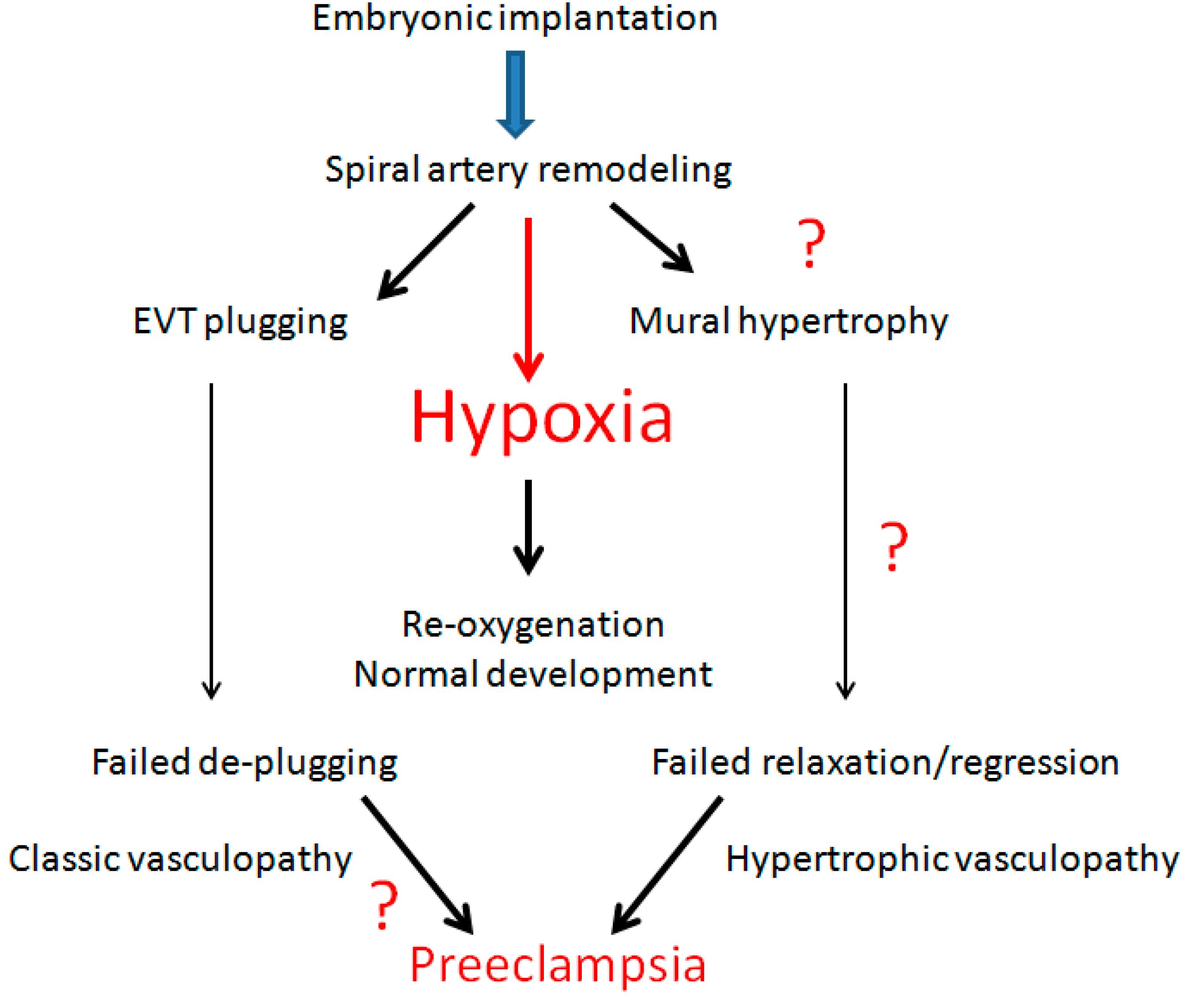

2. Spiral Artery Remodeling and Hypoxia

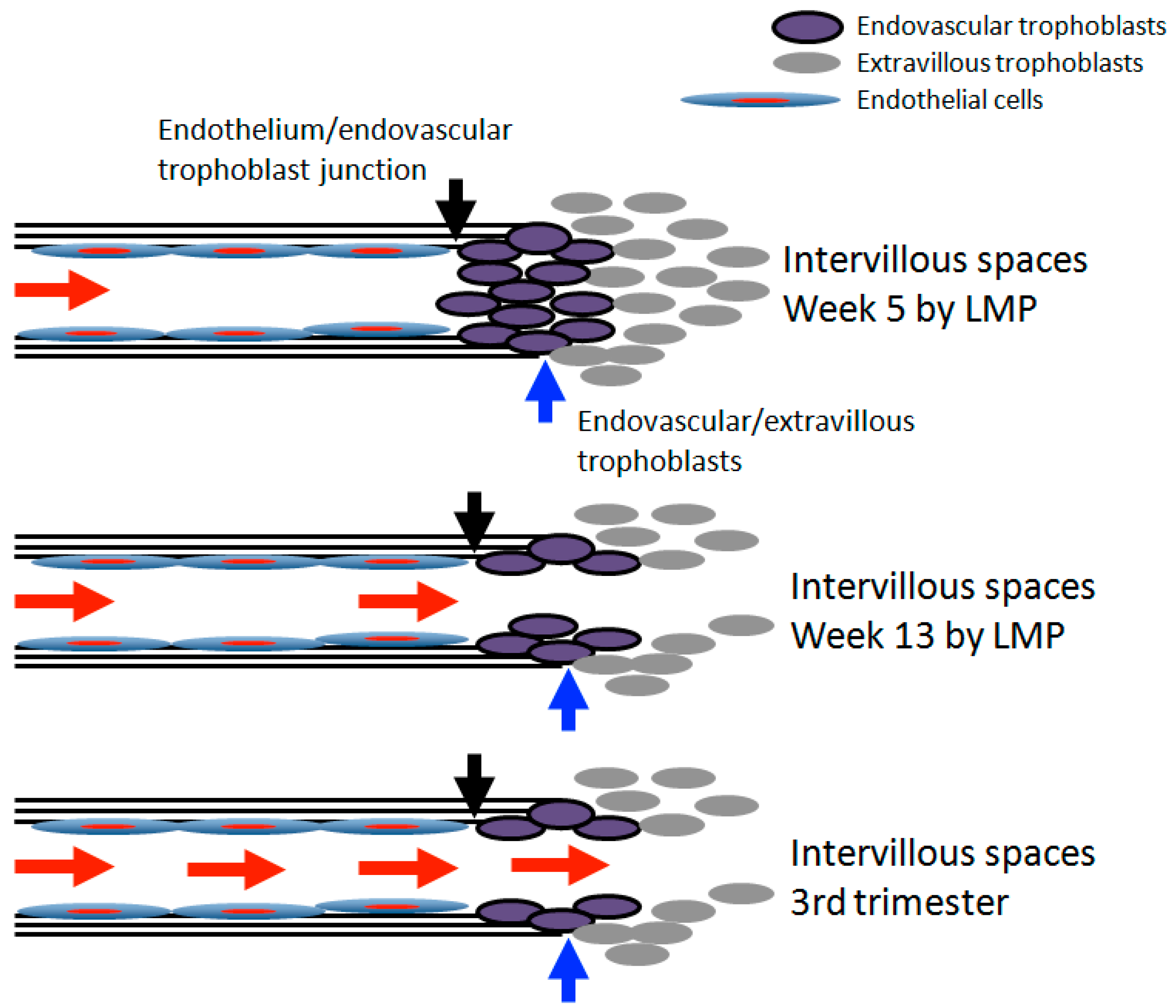

3. Transition of Extravillous Trophoblasts to Endovascular Trophoblasts

4. Hypoxia and Placental/Fetal Development in First Trimester

5. Re-Oxygenation (2nd Trimester and 3rd Trimester)

6. Decidual Vasculopathy and Failure of Trophoblastic Invasion

7. Spiral Artery Remodeling and Placental Lateral Growth

8. Hormonal Actions and WT1 Gene Expression

9. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benirschke, K.; Burton, G.J.; Baergen, R.N. Pathology of the Human Placenta, 6th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khong, T.Y.; Mooney, E.E.; Ariel, I.; Balmus, N.C.M.; Boyd, T.K.; Brundelr, M.-A.; Derricott, H.; Evans, M.J.; Faye-Petersen, O.M.; Gillan, J.E.; et al. Sampling and definitions of placental lesions: Amsterdam placental workshop group consensus statement. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P. Decidual vasculopathy in preeclampsia and spiral artery remodeling revisited: Shallow invasion versus failure of involution. AJP Rep. 2018, 8, e241–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P. Phenotypic switch of endovascular trophoblasts in decidual vasculopathy with implication for preeclampsia and other pregnancy complications. Fetal. Pediatr. Pathol. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertig, A. Vascular pathology in the hypertensive albuminuric toxemias of pregnancy. Clinics 1945, 4, 602–614. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. Decidual vasculopathy and spiral artery remodeling revisited II: Relations to trophoblastic dependent and independent vascular transformation. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craven, C.M.; Morgan, T.; Ward, K. Decidual spiral artery remodelling begins before cellular interaction with cytotrophoblasts. Placenta 1998, 19, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.L.; Zsengeller, Z.K.; Spiel, M.; Karumachi, S.A.; Rosen, S. Revisiting decidual vasculopathy. Placenta 2016, 42, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.S.; Heller, D.S.; Baergen, R.N. Decidual vasculopathy: Placental location and association with ischemic lesions. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2017, 20, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pröll, J.; Blaschitz, A.; Hartmann, M.; Thalhamer, J.; Dohr, G. Human first-trimester placenta intra-arterial trophoblast cells express the neural cell adhesion molecule. Early Pregnancy 1996, 2, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Kam, E.P.; Gardner, L.; Loke, Y.W.; King, A. The role of trophoblast in the physiological change in decidual spiral arteries. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosens, I.; Robertson, W.B.; Dixon, H.G. The physiological response of the vessels of the placental bed to normal pregnancy. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1967, 93, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, W.B.; Brosens, I.; Dixon, H.G. The pathological response of the vessels of the placental bed to hypertensive pregnancy. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1967, 93, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, R.; Kracke, R. The probable role of the hypercholesteremia of pregnancy in producing vascular changes in the placenta, predisposing to placental infarction and eclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1936, 31, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, F.G. Williams Obstetrics, 25th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg, R.; Vercruysse, L.; Hanssens, M. The uterine spiral arteries in human pregnancy: Facts and controversies. Placenta 2006, 27, 939–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damsky, C.H.; Librach, C.; Lim, K.H.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; McMaster, M.T.; Janatpour, M.; Zhou, Y.; Logan, S.K.; Fisher, S.J. Integrin switching regulates normal trophoblast invasion. Development 1994, 120, 3657–3666. [Google Scholar]

- Damsky, C.; Librach, C.; Lim, K.H.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; McMaster, M.T.; Janatpour, M.; Zhou, Y.; Logan, S.K.; Fisher, S.J. Adhesive interactions in peri-implantation morphogenesis and placentation. Reprod. Toxicol. 1997, 11, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Damsky, C.H.; Fisher, S.J. Preeclampsia is associated with failure of human cytotrophoblasts to mimic a vascular adhesion phenotype. One cause of defective endovascular invasion in this syndrome? J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2152–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M.; Sato, Y.; Horie, A.; Tani, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Okunomiya, A.; Matsumoto, H.; Hamanishi, J.; Kondoh, E.; Mandai, M. Endovascular trophoblast expresses CD59 to evade complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2019, 490, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. CD42b Immunostaining as a marker for placental fibrinoid in normal pregnancy and complications. Fetal. Pediatr. Pathol. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genbacev, O.; Joslin, R.; Damsky, C.H.; Polliotti, B.M.; Fisher, S.J. Hypoxia alters early gestation human cytotrophoblast differentiation/invasion in vitro and models the placental defects that occur in preeclampsia. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 97, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Driesche, S.; Myers, M.; Gay, E.; Thong, K.J.; Duncan, W.C. HCG up-regulates hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha in luteinized granulosa cells: Implications for the hormonal regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor A in the human corpus luteum. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 14, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiden, U.; Eyth, C.P.; Majali-Martinez, A.; Desoye, G.; Tam-Amersdorfer, C.; Huppertz, B.; Ghaffari Tabrizi-Wizsy, N. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase 12 is highly specific for non-proliferating invasive trophoblasts in the first trimester and temporally regulated by oxygen-dependent mechanisms including HIF-1A. Histochem. Cell. Biol. 2018, 149, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, J.; Goldman-Wohl, D.; Hamani, Y.; Avraham, I.; Greenfield, C.; Natanson-Yaron, S.; Prus, D.; Cohen-Daniel, L.; Arnon, T.I.; Manaster, I. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, R.H.; Dunk, C.E.; Lye, S.J.; Aplin, J.D.; Harris, L.K.; Jones, R.L. Extravillous trophoblast and endothelial cell crosstalk mediates leukocyte infiltration to the early remodeling decidual spiral arteriole wall. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 4115–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, A.; Harris, L.K.; Innes, B.A.; Lash, G.E.; Aljunaidy, M.M.; Aplin, J.D.; Baker, P.N.; Robson, S.C.; Bulmer, J.N. Uterine natural killer cells initiate spiral artery remodeling in human pregnancy. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 4876–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, L.K.; Clancy, O.H.; Myers, J.E.; Baker, P.N. Plasma from women with preeclampsia inhibits trophoblast invasion. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 16, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P. Expression of Wilm’s Tumor Gene in Endometrium with Potential Link to Gestational Vascular Transformation. Reprod. Med. 2020, 1, 17–31. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-3897/1/1/3 (accessed on 30 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.K.; Keogh, R.J.; Wareing, M.; Baker, P.N.; Cartwright, J.E.; Aplin, J.D.; Whitley, G.S. Invasive trophoblasts stimulate vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis by a fas ligand-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.D.; Dunk, C.E.; Aplin, J.D.; Harris, L.K.; Jones, R.L. Evidence for immune cell involvement in decidual spiral arteriole remodeling in early human pregnancy. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1959–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.K. Review: Trophoblast-vascular cell interactions in early pregnancy: How to remodel a vessel. Placenta 2010, 31, S93–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.K.; Smith, S.D.; Keogh, R.J.; Jones, R.L.; Baker, P.N.; Knöfler, M.; Cartwright, J.E.; Whitley, G.S.; Aplin, J.D. Trophoblast-and vascular smooth muscle cell-derived MMP-12 mediates elastolysis during uterine spiral artery remodeling. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 2103–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafii, S.; Butler, J.M.; Ding, B.S. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature 2016, 529, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.S.; Cao, Z.; Lis, R.; Nolan, D.J.; Guo, P.; Simons, M.; Penfold, M.E.; Shido, K.; Rabbany, S.Y.; Rafii, S. Divergent angiocrine signals from vascular niche balance liver regeneration and fibrosis. Nature 2014, 505, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, D.J.; Ginsberg, M.; Israely, E.; Palikuqi, B.; Poulos, M.G.; James, D.; Ding, B.S.; Schachterle, W.; Liu, Y.; Rosenwaks, Z.; et al. Molecular signatures of tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell heterogeneity in organ maintenance and regeneration. Dev. Cell 2013, 26, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knöfler, M.; Haider, S.; Saleh, L.; Pollheimer, J.; Gamage, T.K.J.B.; James, J. Human placenta and trophoblast development: Key molecular mechanisms and model systems. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3479–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, S.; Smith, J.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N.; Ledwozyw, A.; Kishore, M.; Haas, R.; Mauro, C.; Williams, D.J.; Farsky, S.H.P.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; et al. Neutrophils induce proangiogenic T cells with a regulatory phenotype in pregnancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E8415–E8424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, G.; Smith, J.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N.; Ledwozyw, A.; Kishore, M.; Haas, R.; Mauro, C.; Williams, D.J.; Farsky, S.H.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; et al. Enhanced myogenesis in NCAM-transfected mouse myoblasts. Nature 1990, 344, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackie, P.M.; Zuber, C.; Roth, J. Expression of polysialylated N-CAM during rat heart development. Differentiation 1991, 47, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weledji, E.P.; Assob, J.C. The ubiquitous neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM). Ann. Med. Surg. (Lond.) 2014, 3, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galuska, C.E.; Lütteke, T.; Galuska, S.P. Is Polysialylated NCAM Not only a regulator during brain development but also during the formation of other organs? Biology (Basel) 2017, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromatka, B.S.; Drake, P.M.; Kapidzic, M.; Stolp, H.; Goldfien, G.A.; Shih, I.-M.; Fisher, S.J. Polysialic acid enhances the migration and invasion of human cytotrophoblasts. Glycobiology 2013, 23, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinhold, B.; Seidenfaden, R.; Rockle, I.; Muhlenhoff, M.; Schertzinger, F.; Conzelmann, S.; March, J.D.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; Hildebrandt, H. Genetic ablation of polysialic acid causes severe neurodevelopmental defects rescued by deletion of the neural cell adhesion molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 42971–42977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francavilla, C.; Cattaneo, P.; Berezin, V.; Bock, E.; Ami, D.; de Marco, A.; Christofori, G.; Cavallaro, U. The binding of NCAM to FGFR1 induces a specific cellular response mediated by receptor trafficking. J. Cell. Biol. 2009, 187, 1101–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, J.E.; Rutishauser, U.; Magnuson, T. Targeted mutation of Ncam to produce a secreted molecule results in a dominant embryonic lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 6421–6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J. Oxygen, the Janus gas; its effects on human placental development and function. J. Anat. 2009, 215, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, V.H.J.; Morgan, T.K.; Bednarek, P.; Morita, M.; Burton, G.J.; Lo, J.O.; Frias, A.E. Early first trimester uteroplacental flow and the progressive disintegration of spiral artery plugs: New insights from contrast-enhanced ultrasound and tissue histopathology. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 2382–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindrova-Davies, T.; van Patot, M.T.; Gardner, L.; Jauniaux, E.; Burton, G.J.; Charnock-Jones, D.S. Energy status and HIF signalling in chorionic villi show no evidence of hypoxic stress during human early placental development. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 21, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tache, V.; Ciric, A.; Moretto-Zita, M.; Li, Y.; Peng, J.; Maltepe, E.; Milstone, D.S.; Parast, M. Hypoxia and trophoblast differentiation: A key role for PPARγ. Stem. Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 2815–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeland, A.K.; Soncin, F.; Moretto-ZIta, M.; Chang, C.-W.; Horii, M.; Pizzo, D.; Nelson, K.K.; Laurent, L.C.; Parast, M.M. Hypoxia directs human extravillous trophoblast differentiation in a hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent manner. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Wakeland, A.K.; Parast, M.M. Trophoblast lineage specification, differentiation and their regulation by oxygen tension. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, R43–R56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.J.; Boyd, J.D. Development of the human placenta in the first three months of gestation. J. Anat. 1960, 94, 297–328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dixon, H.G.; Robertson, W.B. Vascular changes in the placental bed. Pathol. Microbiol. (Basel) 1961, 24, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, W.J.; Boyd, J.D. Trophoblast in human utero-placental arteries. Nature 1966, 212, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P. Comparison of Decidual Vasculopathy in Central and Peripheral Regions of Placenta with Implication of Lateral Growth and Spiral Artery Remodeling. 2020. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.16.154484v1 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Pugh, C.W.; Chang, G.W.; Cockman, M.; Epstein, A.C.; Gleadle, J.M.; Maxwell, P.H.; Nicholls, L.G.; O’Rourke, J.F.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Raybould, E.C.; et al. Regulation of gene expression by oxygen levels in mammalian cells. Adv. Nephrol. Necker. Hosp. 1999, 29, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, P.J.; O’Rourke, J.F.; Maxwell, P.H.; Pugh, C.W. Oxygen sensing, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and the regulation of mammalian gene expression. J. Exp. Biol. 1998, 201, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Khong, T.Y.; De Wolf, F.; Robertson, W.B.; Brosens, I. Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and by small-for-gestational age infants. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1986, 93, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijnenborg, R.; Dixon, G.; Robertson, W.B.; Brosens, I. Trophoblastic invasion of human decidua from 8 to 18 weeks of pregnancy. Placenta 1980, 1, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosens, I.A.; Dixon, H.G.; Robertson, W.B. Fetal growth retardation and the arteries of the placental bed. BJOG 1977, 84, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosens, I.A.; Robertson, W.B.; Dixon, H.G. The role of the spiral arteries in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. Annu. 1972, 1, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijnenborg, R.; Bland, J.; Robertson, W.; Dixon, G.; Brosens, I. The pattern of interstitial trophoblastic invasion of the myometrium in early human pregnancy. Placenta 1981, 2, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosens, I.; Puttemans, P.; Benagiano, G. Placental bed research: I. The placental bed: From spiral arteries remodeling to the great obstetrical syndromes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeek, P.M.; Assali, N.S. Vascular changes in the decidua associated with eclamptogenic toxemia of pregnancy. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1950, 20, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, W.B.; Khong, T.Y.; Brosens, I.; De Wolf, F.; Sheppard, B.L.; Bonnar, J. The placental bed biopsy: Review from three European centers. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1986, 155, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafii, S.; Carmeliet, P. VEGF-B improves metabolic health through vascular pruning of fat. Cell. Metab. 2016, 23, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dixon, H.G.; Robertson, W.B. A study of the vessels of the placental bed in normotensive and hypertensive women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Emp. 1958, 65, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raff, M.C. Size control: The regulation of cell numbers in animal development. Cell 1996, 86, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, M.C.; Durand, B.; Gao, F.B. Cell number control and timing in animal development: The oligodendrocyte cell lineage. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1998, 42, 263–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, P.; Black, S.; Huppertz, B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: Implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, T.Y.; Chambers, H.M. Alternative method of sampling placentas for the assessment of uteroplacental vasculature. J. Clin. Pathol. 1992, 45, 925–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, N.D. Wilms’ tumour 1 (WT1) in development, homeostasis and disease. Development 2017, 144, 2862–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, D.A.; Housman, D.E. The genetics of Wilms’ tumor. Adv. Cancer Res. 1992, 59, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M. Wilms Tumor; Codon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gurates, B.; Amsterdam, A.; Tamura, M.; Yang, S.; Zhou, J.; Fang, Z.; Amin, S.; Sebastian, S.; Bulun, S.E. WT1 and DAX-1 regulate SF-1-mediated human P450arom gene expression in gonadal cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003, 208, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, D.; Englert, C. The Wilms tumor suppressor WT1 regulates early gonad development by activation of Sf1. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Estrada, O.M.; Lettice, L.A.; Essafi, A.; Guadix, A.J.; Slight, J.; Velecela, V.; Hall, E.; Reichmann, J.; Devenney, P.; Hohenstein, P.; et al. Wt1 is required for cardiovascular progenitor cell formation through transcriptional control of Snail and E-cadherin. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, Y.-Y.; Brownstein, D.; Mjoseng, H.; Lee, W.-C.; Buza-Viads, N.; Nerlov, C.; Eirik, S.; Jacobsen, E.; Perry, P.; Berry, R.; et al. Acute multiple organ failure in adult mice deleted for the developmental regulator Wt1. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, Y.-Y.; Bandiera, R.; Serrels, A.; Martinez-Estrada, O.M.; Qing, W.; Lee, M.; Slight, J.; Thornburn, A.; Berry, R.; McHaffie, S.; et al. Visceral and subcutaneous fat have different origins and evidence supports a mesothelial source. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2014, 16, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P. Decidual Vasculopathy and Spiral Artery Remodeling Revisited III: Hypoxia and Re-oxygenation Sequence with Vascular Regeneration. Reprod. Med. 2020, 1, 77-90. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed1020006

Zhang P. Decidual Vasculopathy and Spiral Artery Remodeling Revisited III: Hypoxia and Re-oxygenation Sequence with Vascular Regeneration. Reproductive Medicine. 2020; 1(2):77-90. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed1020006

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Peilin. 2020. "Decidual Vasculopathy and Spiral Artery Remodeling Revisited III: Hypoxia and Re-oxygenation Sequence with Vascular Regeneration" Reproductive Medicine 1, no. 2: 77-90. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed1020006

APA StyleZhang, P. (2020). Decidual Vasculopathy and Spiral Artery Remodeling Revisited III: Hypoxia and Re-oxygenation Sequence with Vascular Regeneration. Reproductive Medicine, 1(2), 77-90. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed1020006