Initial Stage Flocculation of Positively Charged Colloidal Particles in the Presence of Ultrafine Bubbles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Materials

2.2. Electrophoretic Mobility Measurement

2.3. Rate of Flocculation Measurement

2.4. Hydrodynamic Layer Thickness Measurement

3. Results and Discussion

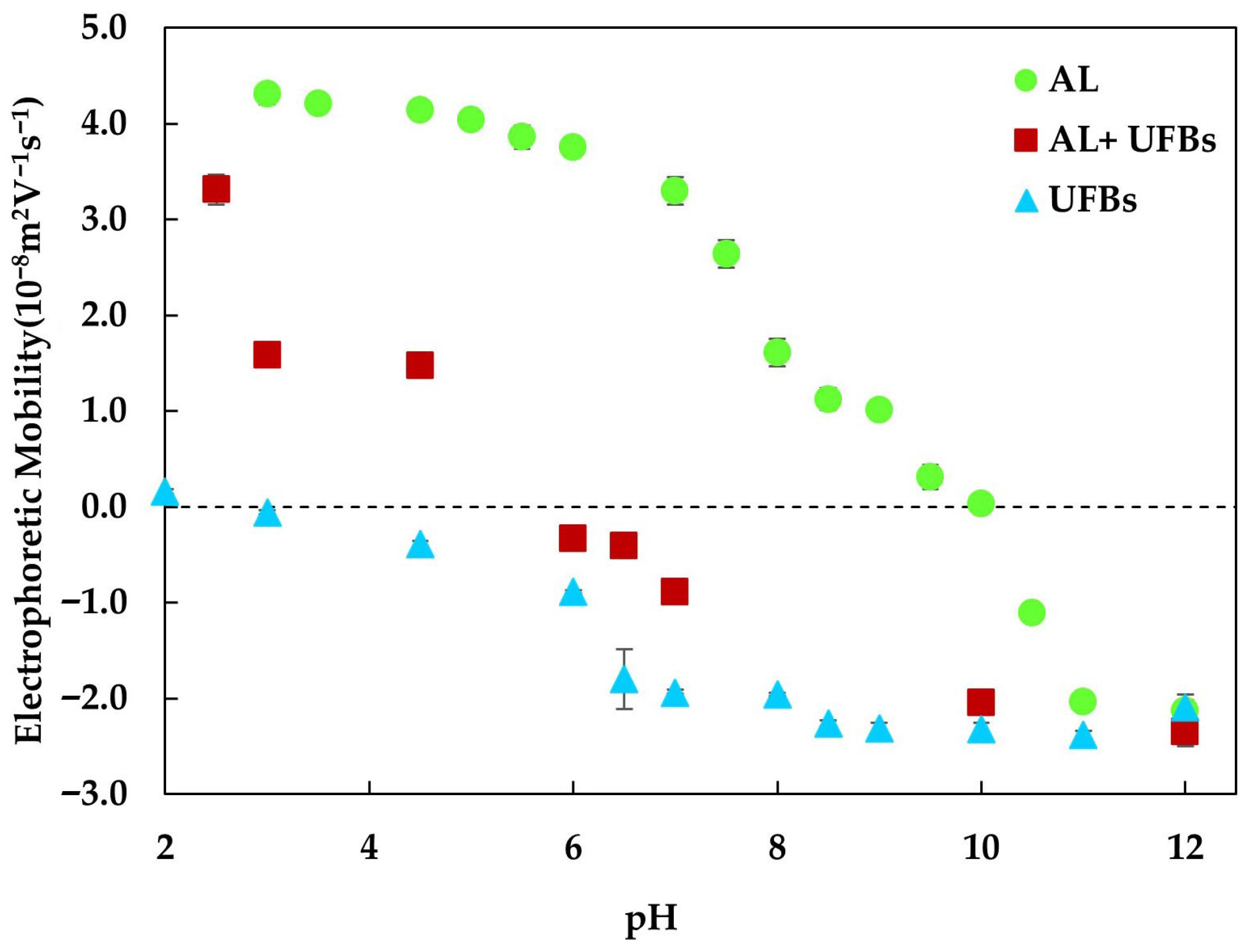

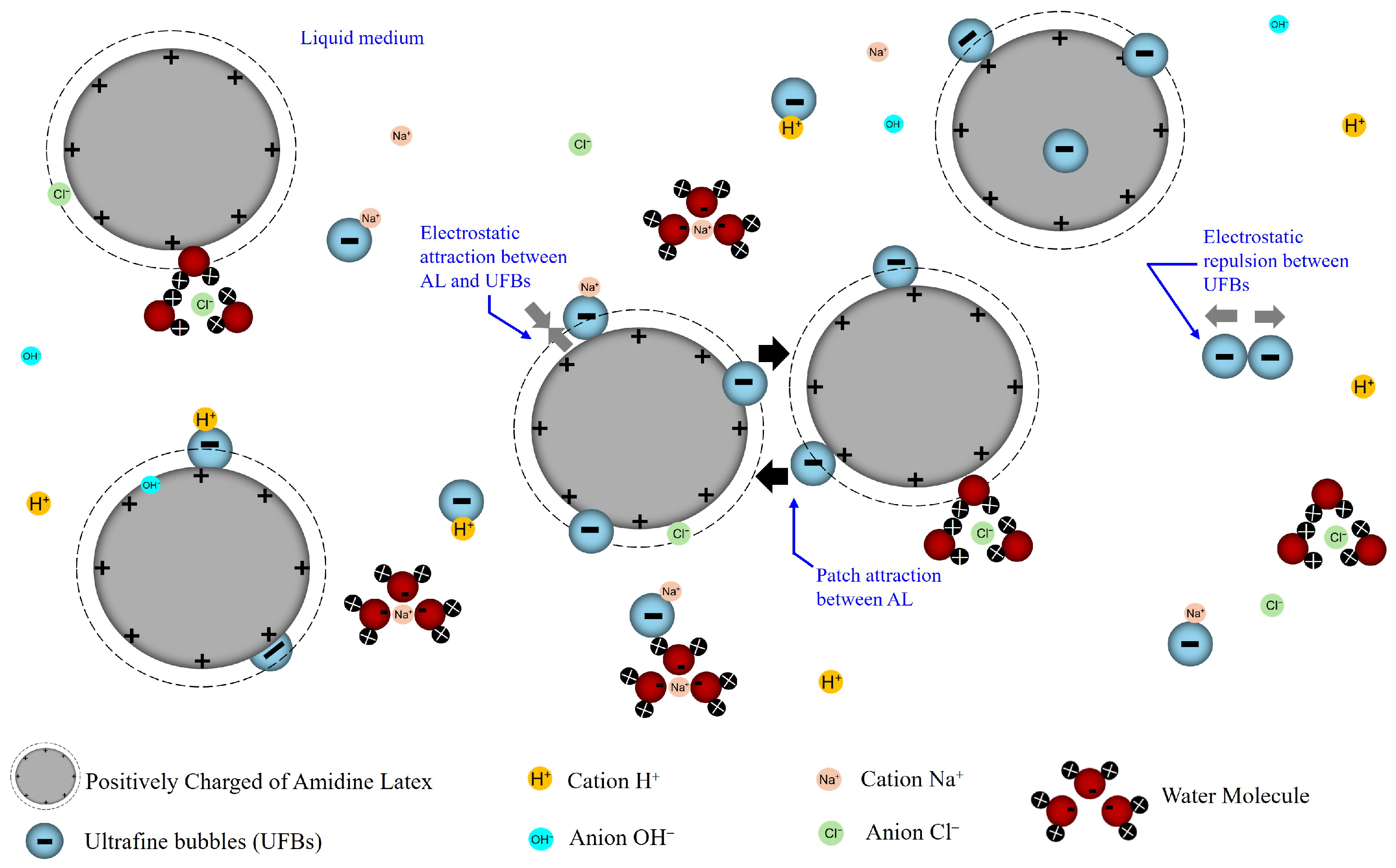

3.1. Electrophoretic Mobility

3.2. Hydrodynamic Layer Thickness

3.3. Rate of Flocculation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AL | Amidine latex |

| CNP | Charge neutralization point |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DLVO | Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek theory |

| EPM | Electrophoretic mobility |

| EDL | Eelctric double layer |

| IEP | Isoelectric point |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| NBs | Nanobubbles |

| NTA | Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| UFBs | Ultrafine bubbles |

Appendix A. Charging Behavior of Ultrafine Bubbles (UFBs)

Appendix A.1. Ionic Strength Dependency

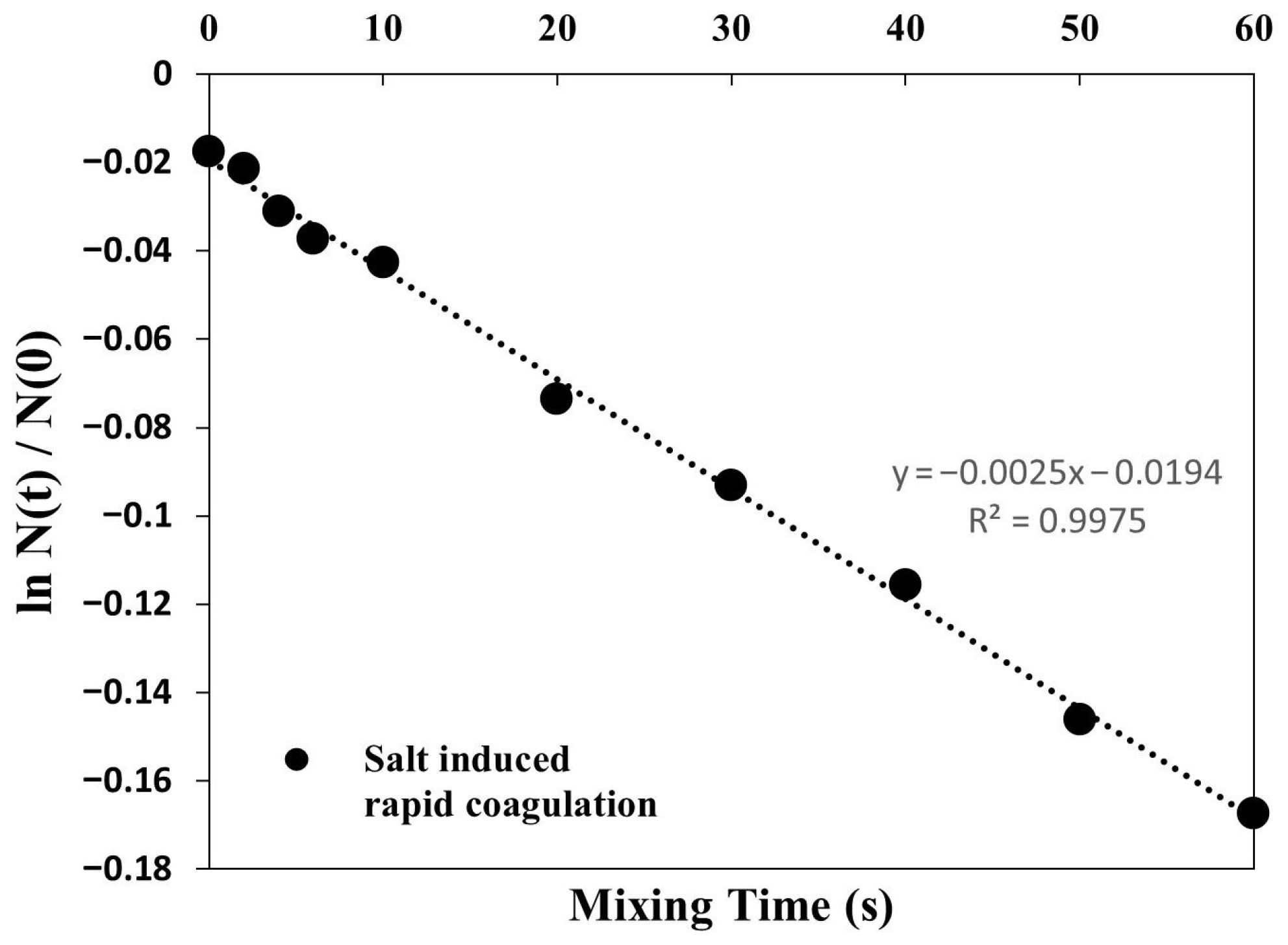

Appendix A.2. Salt-Induced Rapid Coagulation

Appendix A.3. pH Dependency

Appendix A.4. Comparison with Previous Studies

| System Studied | Mechanism/Key Findings | Relation to the Present Study |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles and Bulk Nanobubbles [30] |

| Consistent with our observation that UFBs adsorb to particles, forming complexes that alter colloidal stability and size. |

| Amidine Latex Nanoparticles and Bulk Nanobubbles [32] |

| Directly consistent with our electrokinetic results, confirming UFB adsorption leads to charge compensation and inversion. |

| Kaolin with Cationic Polyacrylamide (CPAM) and Bulk Nanobubbles (NBs) [16] |

| Supports the role of NBs in enhancing aggregation and modifying electrokinetic properties, similar to our observed UFB-assisted mechanisms. |

| Amidine Latex and Ultrafine Bubbles (UFBs) |

| This study provides a cohesive, quantitative framework of the initial-stage flocculation process, linking electrokinetics, interfacial layer properties, and aggregation kinetics. |

References

- ISO 20480-1:2017; Fine Bubble Technology—General Principles for Usage and Measurement of Fine Bubbles—Part 1: Terminology. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:20480:-1:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Tan, B.H.; An, H.; Ohl, C.D. Stability of surface and bulk nanobubbles. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 53, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegoda, J.N.; Aluthgun Hewage, S.; Batagoda, J.H. Stability of Nanobubbles. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2018, 35, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, G.S. On the Thermodynamic Stability of Bubbles, Immiscible Droplets, and Cavities. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 17523–17531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, S.; Hirakawa, T.; Noguchi, Y.; Urushiyama, D.; Miyata, K.; Baba, T.; Yotsumoto, F.; Yasunaga, S.; Nakabayashi, K.; Hata, K. Physical Properties of Ultrafine Bubbles Generated Using a Generator System. In Vivo 2023, 37, 2555–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebina, K.; Shi, K.; Hirao, M.; Hashimoto, J.; Kawato, Y.; Kaneshiro, S.; Morimoto, T.; Koizumi, K.; Yoshikawa, H. Oxygen and air nanobubble water solution promote the growth of plants, fishes, and mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, L.; Lu, W.; Li, P. Enhanced degradation of atrazine by microbubble ozonation. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, T.; Cooper, M.; Pan, G. Reducing arsenic toxicity using the interfacial oxygen nanobubble technology for sediment remediation. Water Res. 2021, 205, 117657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, L.; Gao, Y. Can bulk nanobubbles be stabilized by electrostatic interaction? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 16501–16505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Ng, W.J.; Liu, Y. Principle and Applications of Microbubble and Nanobubble Technology for Water Treatment. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, L.; Song, D.; Lin, F. Characteristics of Micro-Nano Bubbles and Potential Application in Groundwater Bioremediation. Water Environ. Res. 2015, 86, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, J.R. Microbubbles in Medical Imaging: Current Applications and Future Directions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuki, N.; Ichiba, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Nagano, O.; Takeda, M.; Ujike, Y.; Yamaguchi, T. Blood Oxygenation Using Microbubble Suspensions. Eur. Biophys. J. 2012, 41, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Xie, G.; Peng, Y.; Xia, W.; Sha, J. Stability Theories of Nanobubbles at Solid-Liquid Interface: A Review. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 495, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, X.; Bu, X.; Wang, M.; An, B.; Shao, H.; Ni, C.; Peng, Y.; Xie, G. A novel flotation technique combining carrier flotation and cavitation bubbles to enhance separation efficiency of ultra-fine particles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 64, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, G.; Bilal, M.; Sha, J.; Bu, X. Effect of Bulk Nanobubbles on the Flocculation and Filtration Characteristics of Kaolin Using Cationic Polyacrylamide. Minerals 2024, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Exploration of Particle Technology in Fine Bubble Characterization. Particuology 2019, 46, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, T.; Bui, T.T.; Han, M.; Kim, T.I.; Park, H. Micro and Nanobubble Technologies as a New Horizon for Water-Treatment Techniques: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 246, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M. ζ Potential of Microbubbles in Aqueous Solutions: Electrical Properties of the Gas–Water Interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 21858–21864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Somasundaran, P. Reversal of bubble charge in multivalent inorganic salt solutions—Effect of magnesium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1991, 146, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Lee, J.; Moon, Y.; Pradhan, D.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, J. An Experimental Investigation of Cavitation Bulk Nanobubbles Characteristics: Effects of pH and Surface-active Agents. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsall, G.H.; Tang, S.; Yurdakul, S.; Smith, A.L. Electrophoretic behaviour of bubbles in aqueous electrolytes. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1996, 92, 3887–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, M.; Pfeiffer, P.; Eisener, J.; Ohl, C.D.; Sun, C. Ion adsorption stabilizes bulk nanobubbles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 606, 1380–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-González, C.A.; Martínez, J.; Calva-Yáñez, J.C.; Oropeza-Guzmán, M.T. Physicochemical wastewater treatment improvement by hydrodynamic cavitation nanobubbles. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, H. Nanobubbles, hydrophobic effect, heterocoagulation and hydrodynamics in flotation. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2005, 78, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hu, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, K.; Weng, L.; Zhou, W. Aggregates characterizations of the ultra-fine coal particles induced by nanobubbles. Fuel 2021, 297, 120765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M.A.; Nguyen, A.V. Nanobubbles and the nanobubble bridging capillary force. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 154, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, M.A.; Nguyen, A.V. Systematically altering the hydrophobic nanobubble bridging capillary force from attractive to repulsive. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 333, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Yuan, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Alheshibri, M.; Bu, X. Effect of bulk nanobubbles on flocculation of kaolin in the presence of cationic polyacrylamide. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2024, 60, 186729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Seddon, J.R.T. Nanobubble–Nanoparticle Interactions in Bulk Solutions. Langmuir 2016, 32, 11280–11286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, R.; Majumder, S.K. Microbubble generation and microbubble-aided transport process intensification—A state-of-the-art report. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2013, 64, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Seddon, J.R.T.; Lemay, S.G. Nanoparticle–nanobubble interactions: Charge inversion and re-entrant condensation of amidine latex nanoparticles driven by bulk nanobubbles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 538, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, N.; Sakamoto, M.; Miyahara, M.; Higashitani, K. Attraction between Hydrophobic Surfaces with and without Gas Phase. Langmuir 2000, 16, 5681–5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, N.; Inoue, T.; Miyahara, M.; Higashitani, K. Nano Bubbles on a Hydrophobic Surface in Water Observed by Tapping-Mode Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir 2000, 16, 6377–6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, Y.; Stuart, M.A.C.; Fokkink, R. Kinetics of Turbulent Coagulation Studied by Means of End-over-End Rotation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1994, 165, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Adachi, Y. Kinetics of coagulation of model colloidal particles in a turbulent flow. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Irrig. Drain. Reclam. Eng. 1997, 1997, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, Y.; Wada, T. Initial stage dynamics of bridging flocculation of polystyrene latex spheres with polyethylene oxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 229, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, Y.; Kusaka, Y.; Kobayashi, A. Transient behavior of adsorbing/adsorbed polyelectrolytes on the surface of colloidal particles studied by means of trajectory analysis of Brownian motion. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 376, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Stuart, M.C.; Adachi, Y. Dynamics of polyelectrolyte adsorption and colloidal flocculation upon mixing studied using mono-dispersed polystyrene latex particles. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 226, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.; Wulandari, M.; Adachi, Y. Remarkable potential of Na-montmorillonite as a sustainable and eco-friendly material for flocculant studied in the standardized mixing flow. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 23, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyasov, L.O.; Ogawa, K.; Panova, I.G.; Yaroslavov, A.A.; Adachi, Y. Initial-stage dynamics of flocculation of cationic colloidal particles induced by negatively charged polyelectrolytes, polyelectrolyte complexes, and microgels studied using standardized colloid mixing. Langmuir 2020, 36, 8375–8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, M.; Saha, S.; Sugimoto, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Adachi, Y. Initial stage aggregation of colloidal particles induced by the deposition of oppositely charged particles using standardized colloid mixing. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 425, 127271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creux, P.; Lachaise, J.; Graciaa, A.; Beattie, J.K.; Djerdjev, A.M. Strong Specific Hydroxide Ion Binding at the Pristine Oil/Water and Air/Water Interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 14146–14150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, P.; Jougnot, D.; Revil, A.; Lassin, A.; Azaroual, M. A double layer model of the gas bubble/water interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 388, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaucha, M.; Adamczyk, Z.; Barbasz, J. Zeta potential of particle bilayers on mica: A streaming potential study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 360, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montes Ruiz-Cabello, F.J.; Trefalt, G.; Oncsik, T.; Szilagyi, I.; Maroni, P.; Borkovec, M. Interaction Forces and Aggregation Rates of Colloidal Latex Particles in the Presence of Monovalent Counterions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 8184–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Tian, C.; Lei, Z.; Kobayashi, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Adachi, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Zhang, Z. Characteristics of ultra-fine bubble water and its trials on enhanced methane production from waste activated sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 273, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, V.; Hawe, A.; Jiskoot, W. Critical Evaluation of Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) by NanoSight for the Measurement of Nanoparticles and Protein Aggregates. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmalkar, N.; Pacek, A.W.; Barigou, M. On the Existence and Stability of Bulk Nanobubbles. Langmuir 2018, 34, 10964–10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millare, J.C.; Basilia, B.A. Nanobubbles from Ethanol-Water Mixtures: Generation and Solute Effects via Solvent Replacement Method. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 9268–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushikubo, F.Y.; Furukawa, T.; Nakagawa, R.; Enari, M.; Makino, Y.; Kawagoe, Y.; Shiina, T.; Oshita, S. Evidence of the existence and the stability of nano-bubbles in water. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2010, 361, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusaka, Y.; Adachi, Y. Determination of hydrodynamic diameter of small flocs by means of direct movie analysis of Brownian motion. Colloids Surfaces Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 306, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, S.M.; Kalogerakis, N.; Kolliopoulos, G. Effect of chemical species and temperature on the stability of air nanobubbles. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Tao, D. An experimental study on size distribution and zeta potential of bulk cavitation nanobubbles. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2020, 27, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, K.; Tuziuti, T.; Kanematsu, W. Mysteries of bulk nanobubbles (ultrafine bubbles); stability and radical formation. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2018, 48, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.P.; Lohse, D. Dynamic Equilibrium Mechanism for Surface Nanobubble Stabilization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 214505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, S.; Hassanzadeh, A.; He, Y.; Khoshdast, H.; Kowalczuk, P.B. Recent Developments in Generation, Detection and Application of Nanobubbles in Flotation. Minerals 2022, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J. Rates of flocculation of latex particles by cationic polymers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1973, 42, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, N.B.; Murath, S.; Katana, B.; Szilagyi, I. Composite materials based on heteroaggregated particles: Fundamentals and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 294, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.H.; Brata, M.V.; Adachi, Y. Effects of Polymer Branching Structure on the Hydrodynamic Adsorbed Layer Thickness Formed on Colloidal Particles. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2022, 55, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pH Sample | 0.1 mM | 10 mM |

|---|---|---|

| 6.0 ± 0.3 | 0.81 | 2.15 |

| 9.0 ± 0.3 | 0.44 | 1.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wulandari, M.; Saha, S.; Adachi, Y. Initial Stage Flocculation of Positively Charged Colloidal Particles in the Presence of Ultrafine Bubbles. Appl. Nano 2025, 6, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040027

Wulandari M, Saha S, Adachi Y. Initial Stage Flocculation of Positively Charged Colloidal Particles in the Presence of Ultrafine Bubbles. Applied Nano. 2025; 6(4):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040027

Chicago/Turabian StyleWulandari, Marita, Santanu Saha, and Yasuhisa Adachi. 2025. "Initial Stage Flocculation of Positively Charged Colloidal Particles in the Presence of Ultrafine Bubbles" Applied Nano 6, no. 4: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040027

APA StyleWulandari, M., Saha, S., & Adachi, Y. (2025). Initial Stage Flocculation of Positively Charged Colloidal Particles in the Presence of Ultrafine Bubbles. Applied Nano, 6(4), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040027