Development of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Films Functionalized with Ag/TiO2 Catalysts for Antimicrobial and Packaging Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Mixed Oxides

2.3. Preparation of Films

2.4. Characterization of Films

2.4.1. Visual and Tactile Aspects

2.4.2. Structure Properties

2.4.3. Morphological Properties

2.4.4. Physical Properties

2.4.5. Optical Properties

2.4.6. Mechanical Properties

2.4.7. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

2.4.8. Antimicrobial Activity of the Films

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Films Characteristics

3.1.1. Visual and Tactile Aspects

3.1.2. Structural Properties

3.1.3. Morphological Properties

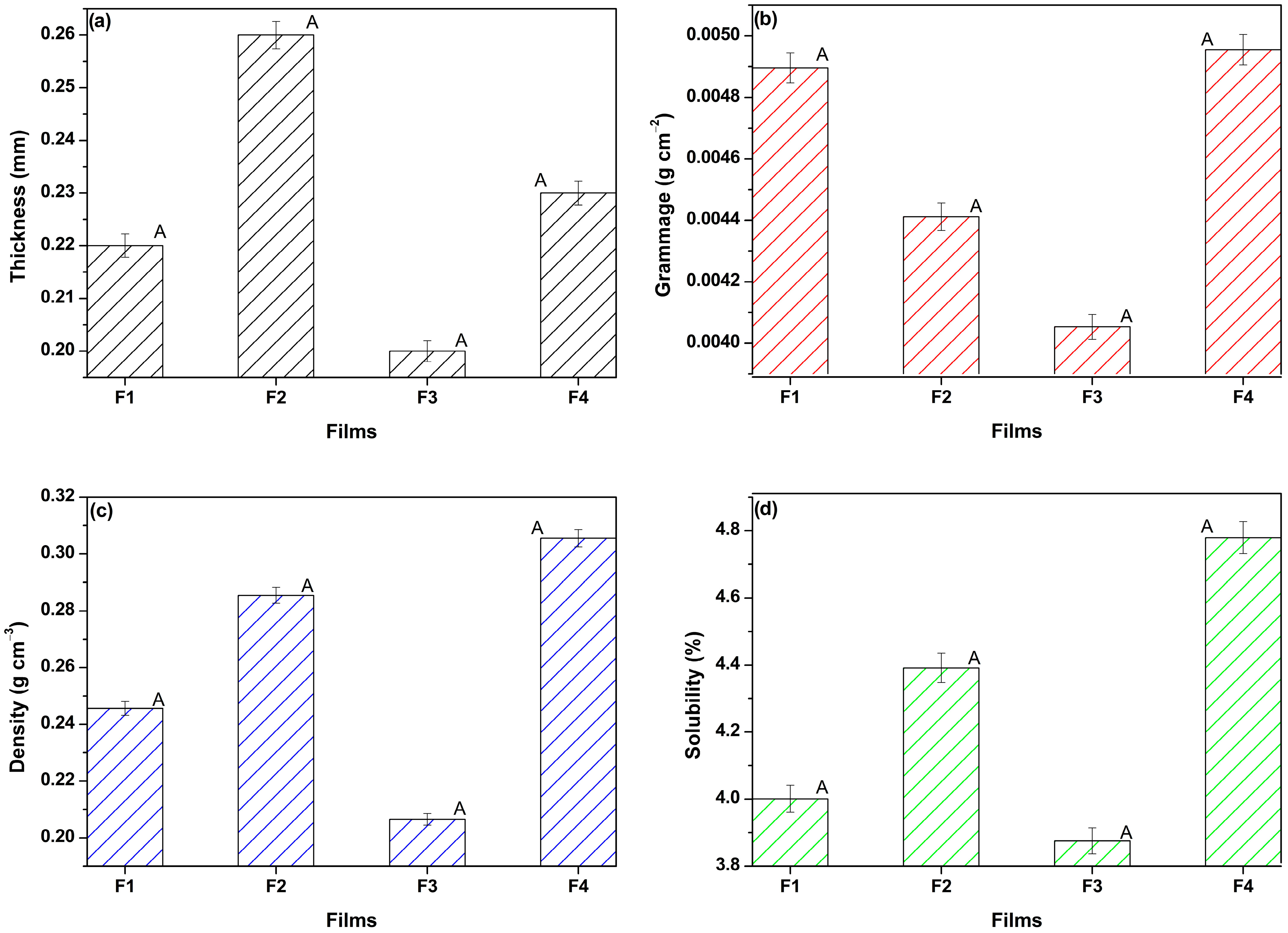

3.1.4. Physical Properties

3.1.5. Optical Properties

3.1.6. Mechanical Properties

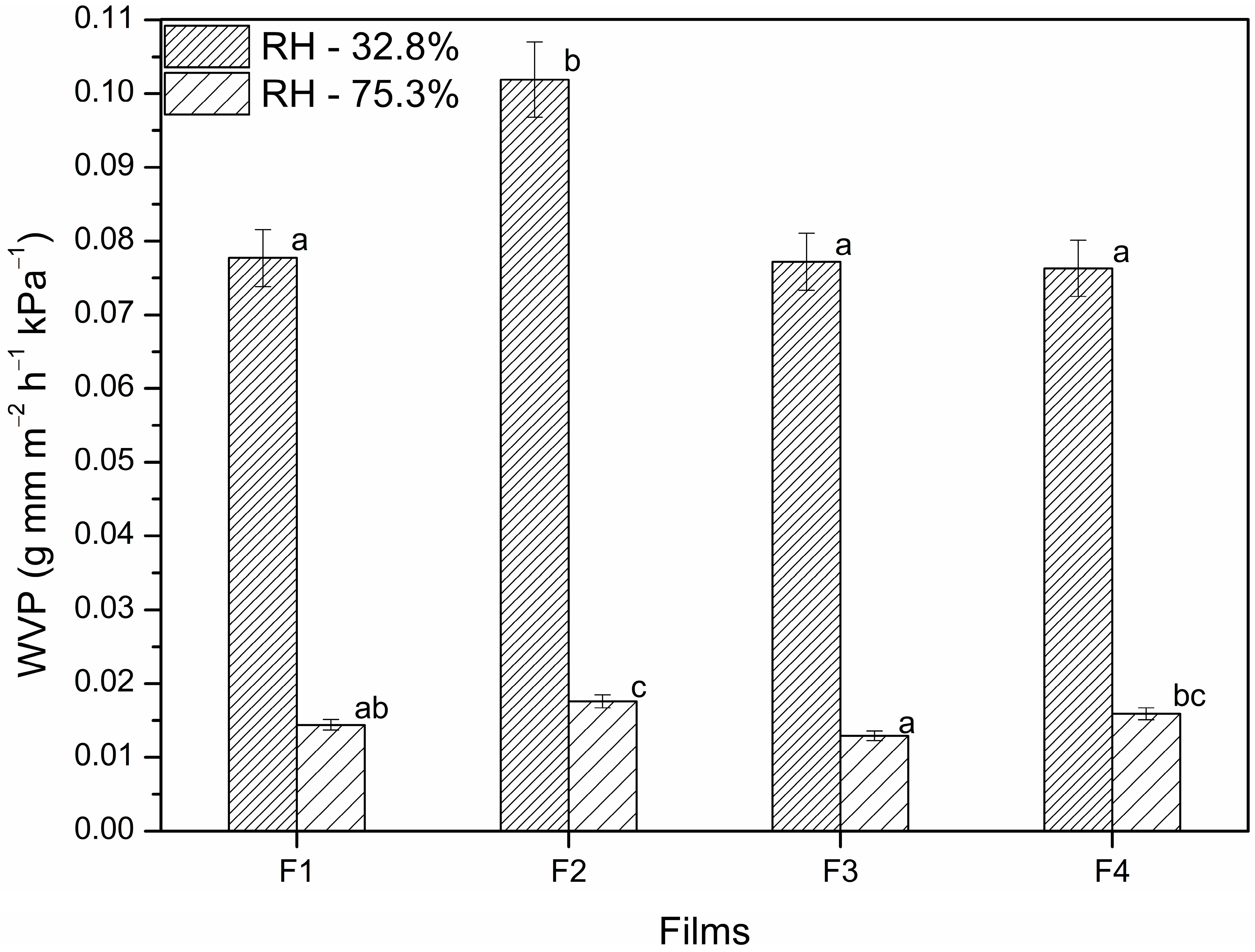

3.1.7. Water Vapor Permeability of the Films

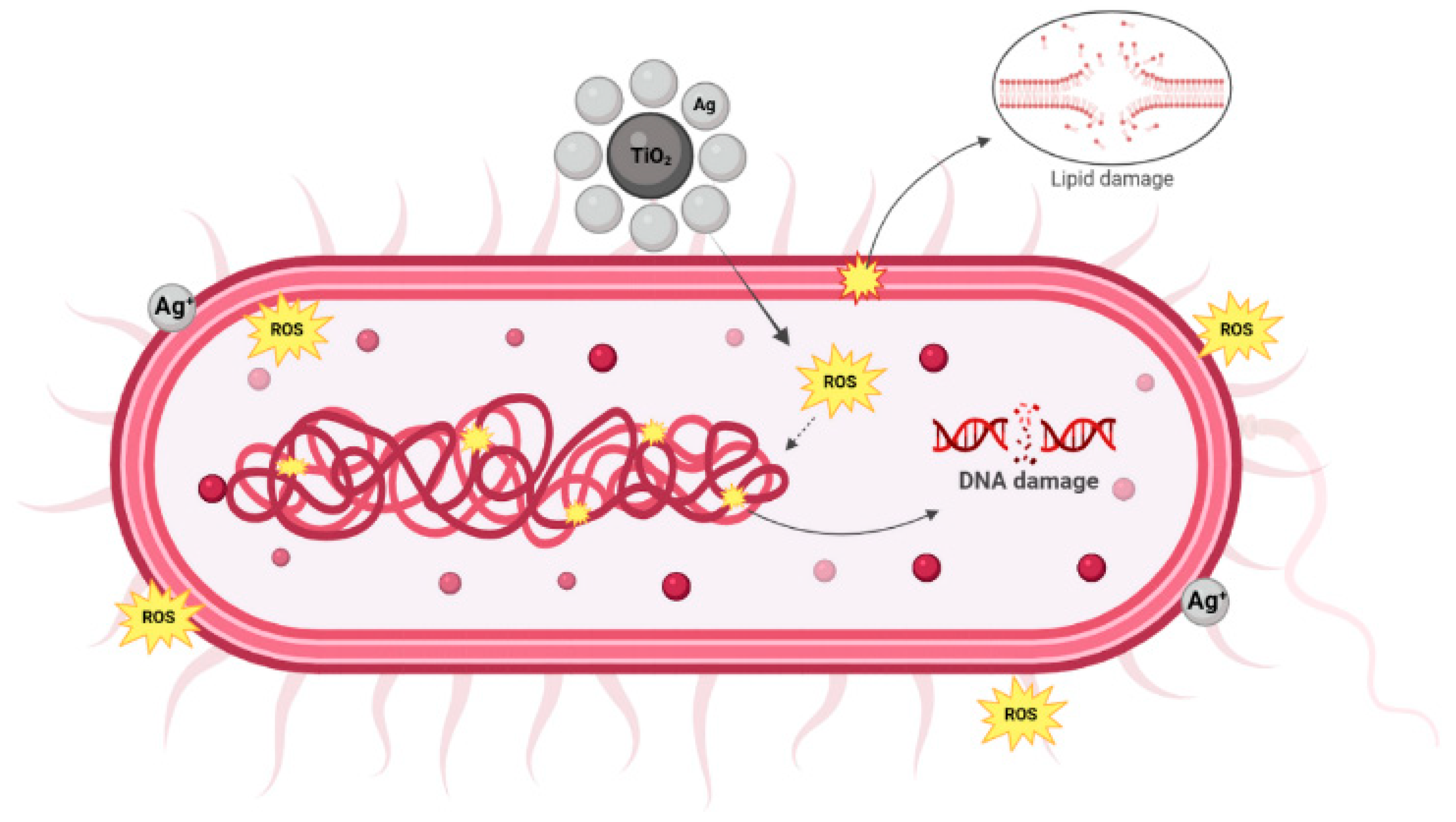

3.1.8. Antimicrobial Activity of the Films

3.2. Limitations, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Euring, M.; Ostendorf, K.; Zhang, K. Biobased Materials for Food Packaging. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2022, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Poon, K.; Masonsong, G.S.P.; Ramaswamy, Y.; Singh, G. Sustainable Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versino, F.; Ortega, F.; Monroy, Y.; Rivero, S.; López, O.V.; García, M.A. Sustainable and Bio-Based Food Packaging: A Review on Past and Current Design Innovations. Foods 2023, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Cui, L.; Xu, C.; Wu, S. Next-Generation Bioplastics for Food Packaging: Sustainable Materials and Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, N.M.; Matuana, L.M. Trends in Sustainable Biobased Packaging Materials: A Mini Review. Mater. Today Sustain. 2021, 15, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubiev, O.M.; Egorov, A.R.; Kirichuk, A.A.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; Kritchenkov, A.S. Chitosan-Based Antibacterial Films for Biomedical and Food Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Z.; Rhim, J.-W.; Bagheri, R.; Pircheraghi, G.; Lotfali, E. Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Based Functional Film Integrated with Chitosan-Based Carbon Quantum Dots for Active Food Packaging Applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 166, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chonanant, C.; Chancharoen, P.; Kiatkulanusorn, S.; Luangpon, N.; Klarod, K.; Surakul, P.; Thamwiriyasati, N.; Singsanan, S.; Ngernyuang, N. Biocomposite Scaffolds Based on Chitosan Extraction from Shrimp Shell Waste for Cartilage Tissue Engineering Application. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 39419–39429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.E.N.; Barroso, T.L.C.T.; Ferreira, V.C.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Burgon, V.H.; Queiroz, M.; Ribeiro, L.F.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Application of Functional Compounds from Agro-Industrial Residues of Brazilian’s Tropical Fruits Extracted by Sustainable Methods in Alginate-Chitosan Microparticles. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2024, 32, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jbeli, A.; Hamden, Z.; Bouattour, S.; Ferraria, A.M.; Conceição, D.S.; Ferreira, L.F.V.; Chehimi, M.M.; do Rego, A.M.B.; Rei Vilar, M.; Boufi, S. Chitosan-Ag-TiO2 Films: An Effective Photocatalyst under Visible Light. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Ponciano, C.; Gonzaga, F.C.; de Oliveira, C.P. Smart Packaging Based on Chitosan Acting as Indicators of Changes in Food: A Technological Prospecting Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagloul, H.; Dhahri, M.; Bashal, A.H.; Khaleil, M.M.; Habeeb, T.H.; Khalil, K.D. Multifunctional Ag2O/Chitosan Nanocomposites Synthesized via Sol-Gel with Enhanced Antimicrobial, and Antioxidant Properties: A Novel Food Packaging Material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 129990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, R.; Tu, H.; Jiang, L. A New Strategy to Construct Cellulose-Chitosan Films Supporting Ag/Ag2O/ZnO Heterostructures for High Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 609, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, G.; Muthuswamy, S.; Kolanthai, E.; Megha, M.; Thomas, J.; Haris, M.; Gopinath, G.; Varghese, R.; Ayyasamy, S. Synthesis and Analysis of Multifunctional Graphene Oxide/Ag2O-PVA/Chitosan Hybrid Polymeric Composite for Wound Healing Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Ma, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhang, R.; Tu, H.; Jiang, L. In Situ Synthesis of Ag/Ag2O–Cellulose/Chitosan Nanocomposites via Adjusting KOH Concentration for Improved Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, G.; Xu, X.; Jiao, B.; et al. Chitosan/Kudzu-Based Packaging Films Synergistically Reinforced by Paeonol@ZIF-8 and Ag2CO3/Ag2O Nano-Heterojunctions for Raspberry Preservation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 51, 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, H.M.; Diab, N.S.; AlElaimi, M.; Alghamdi, A.M.; Farea, M.O.; Farea, A. Fabrication and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticle-Doped Chitosan/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Nanocomposites for Optoelectronic and Biological Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 22112–22122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alven, S.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Chitosan-Based Scaffolds Incorporated with Silver Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Infected Wounds. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Tang, H.; Zhu, H. Advances in Extraction, Utilization, and Development of Chitin/Chitosan and Its Derivatives from Shrimp Shell Waste. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamsomphong, K.; Xu, H.; Yang, P.; Yotpanya, N.; Yokoi, T.; Takahashi, F. Transforming Waste into Wealth in Sustainable Shrimp Aquaculture: Effective Phosphate Removal and Recovery Using Shrimp Shell-Derived Adsorbents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 357, 129982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Liu, X.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, G.; Ai, L. Research Progress on Detection of Foodborne Pathogens: The More Rapid and Accurate Answer to Food Safety. Food Res. Int. 2024, 193, 114767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sganzerla, W.G.; Castro, L.E.N.; da Rosa, C.G.; Almeida, A.d.R.; Maciel-Silva, F.W.; Kempe, P.R.G.; de Oliveira, A.L.R.; Forster-Carneiro, T.; Bertoldi, F.C.; Barreto, P.L.M.; et al. Production of Nanocomposite Films Functionalized with Silver Nanoparticles Bioreduced with Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Essential Oil. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 11, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Guo, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Gong, W. Biodegradable Antimicrobial Films Prepared in a Continuous Way by Melt Extrusion Using Plant Extracts as Effective Components. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, A.P.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Nochi Castro, L.E.; Cruz Tabosa Barroso, T.L.; da Silva, A.P.G.; da Rosa, C.G.; Nunes, M.R.; Forster-Carneiro, T.; Rostagno, M.A. Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Grape Peel and Application in PH-Sensing Carboxymethyl Cellulose Films: A Promising Material to Monitor the Freshness of Pork and Milk. Food Res. Int. 2024, 179, 114017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.E.N.; Matheus, L.R.; Lenzi, G.G.; Arantes, M.K.; Almeida, L.N.B.; Brackmann, R.; Colpini, L.M.S. Assessment of the Effect of Zn Co-Doping on Fe/TiO2 Supports in the Preparation of Catalysts by Wet Impregnation for Photodegradation Reactions of Food Coloring Effluents. Colorants 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, S.; Agyei, D.; Ali, A. Smart Chitosan Films as Intelligent Food Packaging: An Approach to Monitoring Food Freshness and Biomarkers. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 46, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, L.O.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Rosa, G.B.; da Rosa, C.G.; Agostinetto, L.; Veeck, A.P.d.L.; Bretanha, L.C.; Micke, G.A.; Dalla Costa, M.; Bertoldi, F.C.; et al. Chitosan Packaging Functionalized with Cinnamodendron Dinisii Essential Oil Loaded Zein: A Proposal for Meat Conservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Ke, K.; Pang, J.; Wu, C.; Yan, Z. High Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan Films with Covalent Organic Frameworks Immobilized Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin, M.; Lupei, M.; Bucatariu, S.-M.; Pelin, I.M.; Doroftei, F.; Ichim, D.L.; Daraba, O.M.; Fundueanu, G. PVA/Chitosan Thin Films Containing Silver Nanoparticles and Ibuprofen for the Treatment of Periodontal Disease. Polymer 2022, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Fan, B.; He, Y.-C.; Ma, C. Antibacterial, Antioxidant and Fruit Packaging Ability of Biochar-Based Silver Nanoparticles-Polyvinyl Alcohol-Chitosan Composite Film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Xie, Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, S.; Ge, S.; Li, H.; Chang, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Shan, Y.; et al. Visible Light-Responsive TiO2-Based Hybrid Nanofiller Reinforced Multifunctional Chitosan Film for Effective Fruit Preservation. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachtanapun, P.; Klunklin, W.; Jantrawut, P.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Leksawasdi, N.; Chaiyaso, T.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Phongthai, S.; et al. Characterization of Chitosan Film Incorporated with Curcumin Extract. Polymer 2021, 13, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, M.; BhagyaRaj, G.V.S.; Dash, K.K.; Shams, R. A Thorough Evaluation of Chitosan-Based Packaging Film and Coating for Food Product Shelf-Life Extension. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sganzerla, W.G.; Rosa, G.B.; Ferreira, A.L.A.; da Rosa, C.G.; Beling, P.C.; Xavier, L.O.; Hansen, C.M.; Ferrareze, J.P.; Nunes, M.R.; Barreto, P.L.M.; et al. Bioactive Food Packaging Based on Starch, Citric Pectin and Functionalized with Acca Sellowiana Waste by-Product: Characterization and Application in the Postharvest Conservation of Apple. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D882-95; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1995.

- ASTM G32-10; Standard Test Method for Cavitation Erosion Using Vibratory Apparatus. Annual Book of ASTM Standards. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM); FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2025.

- Ribeiro Júnior, J.C.; Rodrigues, E.M.; Dias, B.P.; da Silva, E.P.R.; Alexandrino, B.; Lobo, C.M.O.; Tamanini, R.; Alfieri, A.A. Toxigenic Characterization, Spoilage Potential, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococcus Species Isolated from Minas Frescal Cheese. J. Dairy. Sci. 2024, 107, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margalho, L.P.; Graça, J.S.; Kamimura, B.A.; Lee, S.H.I.; Canales, H.D.S.; Chincha, A.I.A.; Caturla, M.Y.R.; Brexó, R.P.; Crucello, A.; Alvarenga, V.O.; et al. Enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus Aureus in Brazilian Artisanal Cheeses: Occurrence, Counts, Phenotypic and Genotypic Profiles. Food Microbiol. 2024, 121, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, J.N.N.; Corradini, E.; de Souza, P.R.; Marques, V.d.S.; Radovanovic, E.; Muniz, E.C. Films Based on Mixtures of Zein, Chitosan, and PVA: Development with Perspectives for Food Packaging Application. Polym. Test. 2021, 101, 107279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessaro, L.; Lourenço, R.V.; Martelli-Tosi, M.; do Amaral Sobral, P.J. Gelatin/Chitosan Based Films Loaded with Nanocellulose from Soybean Straw and Activated with “Pitanga” (Eugenia Uniflora L.) Leaf Hydroethanolic Extract in W/O/W Emulsion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 186, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, V.A.d.S.; Rodrigues, G.d.M.; Monteiro, V.M.; Carvalho, R.A.d.; da Silva, C.; Yoshida, C.M.P.; Martelli, S.M.; Velasco, J.I.; Matta Fakhouri, F. A Gelatin-Based Film with Acerola Pulp: Production, Characterization, and Application in the Stability of Meat Products. Polymers 2025, 17, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qiao, D.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, B.; Xie, F. Advanced Functional Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Materials for Performance-Demanding Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2024, 157, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Gupta, M.; Mukherjee, S.K. Effect of Ag Layer Thickness on Optical and Electrical Properties of Ion-Beam-Sputtered TiO2/Ag/TiO2 Multilayer Thin Film. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 6942–6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Ben Haj Amara, A.; Bechelany, M. Halloysite-TiO2 Nanocomposites for Water Treatment: A Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahy, J.G.; Lejeune, L.; Haynes, T.; Lambert, S.D.; Marcilli, R.H.M.; Fustin, C.-A.; Hermans, S. Eco-Friendly Colloidal Aqueous Sol-Gel Process for TiO2 Synthesis: The Peptization Method to Obtain Crystalline and Photoactive Materials at Low Temperature. Catalysts 2021, 11, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzzeka, C.; Goldoni, J.; de Paula de Oliveira, J.d.R.; Lenzi, G.G.; Bagatini, M.D.; Colpini, L.M.S. Photocatalytic Action of Ag/TiO2 Nanoparticles to Emerging Pollutants Degradation: A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 8, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saisruthi, V.; Kumar, J.A.; Rosana, N.T.M.; Joseph, K.L.V.; Rubavathy, S.J. Bio-Fabricated TiO2 Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Insight Into Its Antimicrobial, Anticancer, and Environmental Applications. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2024, 34, e22359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, Y.; Qian, L.; Qi, P.; Xie, M.; Long, H. Flue Gas DeNOxing Spent V2O5-WO3/TiO2 Catalyst: A Review of Deactivation Mechanisms and Current Disposal Status. Fuel 2023, 338, 127268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydanju, N.; Pirsa, S.; Farzi, J. Biodegradable Film Based on Lemon Peel Powder Containing Xanthan Gum and TiO2–Ag Nanoparticles: Investigation of Physicochemical and Antibacterial Properties. Polym. Test. 2022, 106, 107445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, J.; Hou, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Lu, L.; Gao, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, F.; et al. Review: Application of Chitosan and Its Derivatives in Medical Materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 240, 124398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriyati; Dara, F.; Primadona, I.; Srikandace, Y.; Karina, M. Development of Bacterial Cellulose/Chitosan Films: Structural, Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties. J. Polym. Res. 2021, 28, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, D. Towards Heterogeneous Catalysis: A Review on Recent Advances of Depositing Nanocatalysts in Continuous–Flow Microreactors. Molecules 2022, 27, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, R.; Han, J.; Ren, L.; Jiang, L. Protein-Based Packaging Films in Food: Developments, Applications, and Challenges. Gels 2024, 10, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Herrera, A.; Pérez-Cervera, C.; Andrade-Pizarro, R. Recent Advances of Films and Coatings Based on Cassava, Yam, and Sweet Potato Starches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Zhong, S.; Cui, X. Chitosan-Gelatin Composite Hydrogel Antibacterial Film for Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 285, 138330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Matú, D.I.; Toledo-López, V.M.; Vargas, M. de L.V. y; Rincón-Arriaga, S.; Rodríguez-Félix, A.; Madera-Santana, T.J. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan-Based Bioactive Films Incorporating Moringa Oleifera Leaves Extract. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 4813–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Ji, C.; Xiao, Z.; Luo, Y. Ultrasonication-Based Preparation of Raw Chitin Nanofiber and Evaluation of Its Reinforcement Effect on Chitosan Film for Functionalization with Curcumin. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 155, 110193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaza, Y.B.; Hamdi, M.; Charmette, C.; Jridi, M.; Li, S.; Nasri, M.; Nasri, R. Development and Characterization of Active Packaging Films Based on Chitosan and Sardinella Protein Isolate: Effects on the Quality and the Shelf Life of Shrimps. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 31, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Li, J.; Qin, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhong, J. Improved Moisture Barrier and Mechanical Properties of Rice Protein/Sodium Alginate Films for Banana and Oil Preservation: Effect of the Type and Addition Form of Fatty Acid. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Yang, Q.; Yuan, C.; Guo, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Nishinari, K.; Zhao, M.; Cui, B. Characterizations of Corn Starch Edible Films Reinforced with Whey Protein Isolate Fibrils. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; McClements, D.J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Jin, Z.; Chen, L. Development, Characterization, and Biological Activity of Composite Films: Eugenol-Zein Nanoparticles in Pea Starch/Soy Protein Isolate Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 293, 139342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.; Song, Y.-Z.; Thakur, K.; Zhang, J.-G.; Khan, M.R.; Ma, Y.-L.; Wei, Z.-J. Blueberry Anthocyanin Based Active Intelligent Wheat Gluten Protein Films: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications for Shrimp Freshness Monitoring. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, L.; Ji, X.; Shen, M.; Chen, X.; Qi, X.; Li, Y.; Xie, J. Characterization of Gallic Acid-Chinese Yam Starch Biodegradable Film Incorporated with Chitosan for Potential Use in Pork Preservation. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallos-Núñez, J.; Cardero, Y.; Cabrera-Barjas, G.; García-Herrera, C.M.; Inostroza, M.; Estevez, M.; España-Sánchez, B.L.; Valenzuela, L.M. Eco-Friendly Design of Chitosan-Based Films with Biodegradable Properties as an Alternative to Low-Density Polyethylene Packaging. Polymers 2024, 16, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvek, M.; Paul, U.C.; Zia, J.; Mancini, G.; Sedlarik, V.; Athanassiou, A. Biodegradable Films of PLA/PPC and Curcumin as Packaging Materials and Smart Indicators of Food Spoilage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 14654–14667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.d.R.; Brisola Maciel, M.V.d.O.; Machado, M.H.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Teixeira, G.L.; da Rosa, C.G.; Block, J.M.; Nunes, M.R.; Barreto, P.L.M. Production of Chitosan and Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Films Functionalized with Hop Extract (Humulus lupulu L. var. Cascade) for Food Packaging Application. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 32, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-A. Water Repellency/Proof/Vapor Permeability Characteristics of Coated and Laminated Breathable Fabrics for Outdoor Clothing. Coatings 2021, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMC Klebetechnik. GmbH Water Vapor Permeability of Various Plastic Films; CMC Klebetechnik: Frankenthal, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Omodara, M.A.; Montross, M.D.; McNeill, S.G. Water Vapor Permeability of Bag Materials Used during Bagged Corn Storage. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2021, 23, 329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Siracusa, V. Food Packaging Permeability Behaviour: A Report. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2012, 2012, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, P.; Kouzes, R. Water Vapor Permeation in Plastics; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory: Richland, WA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy, C.; Dixion, D.; Archer, E.; Dooher, T.; Edwards, I. A Comparison of the Sealing, Forming and Moisture Vapour Transmission Properties of Polylactic Acid (PLA), Polyethene (PE) and Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Coated Boards for Packaging Applications. J. Packag. Technol. Res. 2022, 6, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Morales-Sanchez, E.; Velazquez, G.; Vázquez, M. Measurement of the Water Vapor Permeability of Chitosan Films: A Laboratory Experiment on Food Packaging Materials. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 2403–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.; Janaswamy, S. Biodegradable Films from the Lignocellulosic Residue of Switchgrass. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 201, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Riahi, Z.; Kim, J.T.; Rhim, J.-W. Chitosan-Based Active Packaging Film Incorporated with TiO2/N Co-Doped Carbon Dots to Extend the Shelf Life of Bread. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 727, 138179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieu, L.P.; Pham, T.T.; Pham, T.G.A.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Le, T.T.T. Photocatalytic Chitosan Films Loaded with Ag-Modified C-TiO2 Nanohybrids for Ethylene Scavenging and Prolonging the Shelf Life of Bananas under Visible Light. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 330, 148031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyaseelan, A.; Lu, Y.; Ryu, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.-H. Synthesis of Cytocompatible Gum Arabic–Encapsulated Silver Nitroprusside Nanocomposites for Inhibition of Bacterial Pathogens and Food Safety Applications. Environ. Res. 2024, 263, 120246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chicea, D.; Nicolae-Maranciuc, A.; Chicea, L.-M. Silver Nanoparticles-Chitosan Nanocomposites: A Comparative Study Regarding Different Chemical Syntheses Procedures and Their Antibacterial Effect. Materials 2024, 17, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, G.; Alharbi, N.S.; Chackaravarthy, G.; Kanisha Chelliah, C.; Rajivgandhi, G.; Maruthupandy, M.; Quero, F.; Natesan, M.; Li, W.-J. Chitosan/Silver Nanocomposites Enhanced the Biofilm Eradication in Biofilm Forming Gram Positive S. Aureus. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanda, S.A.; Shaibu, R.O.; Agunbiade, F.O. Eco-Friendly Synthesis and Antibacterial Potential of Chitosan Crosslinked-EDTA Silver Nanocomposite (CCESN). J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2024, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, Z.; Shariati, A.; Alikhani, M.Y.; Safaiee, M.; Rajaeih, S.; Arabestani, M.; Azizi, M. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Stabilized with C-Phycocyanin against Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Staphylococcus Aureus. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1455385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.; Deshmukh, P.; Dhodamani, G.; More, V.; Delekar, D. Different Strategies for Modification of Titanium Dioxide as Heterogeneous Cata Lyst in Chemical Transformations. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzzeka, C.; Goldoni, J.; Marafon, F.; da Silva, G.B.; Manica, D.; Bittencourt, P.R.S.; Bagatini, M.D.; Colpini, L.M.S. Ag/TiO2 Photocatalysts: A Promising Tool in Combating Bacterial Resistance. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 69, 103751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silano, V.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Crebelli, R.; Gott, D.M.; Grob, K.; Lambré, C.; Lampi, E.; et al. Review and Priority Setting for Substances That Are Listed without a Specific Migration Limit in Table 1 of Annex 1 of Regulation 10/2011 on Plastic Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food. EFSA J. 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiaga, G.; Ramos, K.; Ramos, L.; Cámara, C.; Gómez-Gómez, M. Migration and Characterisation of Nanosilver from Food Containers by AF4-ICP-MS. Food Chem. 2015, 166, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crema, N.M.; Castro, L.E.N.d.; Alves, H.J.; Ribeiro, L.F. Impact of Incorporating Chitosan into Starch Films: Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Degradability in Soil. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 8, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Film 1 | Parameters 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuity | Homogeneity | Handling | |

| F1 | ●●● | ●●● | ●●● |

| F2 | ●●● | ●● | ●●● |

| F3 | ●●● | ● | ●●● |

| F4 | ●●● | ●● | ●●● |

| Ag (Weight %) | Catalyst |

|---|---|

| 1.40 ± 0.11 | Ag2%/TiO2 |

| 9.80 ± 0.18 | Ag10%/TiO2 |

| Parameters 1 | L* | a* | b* | C* | H° | ΔEab | T250nm (%) | T600nm (%) | Opacity (Abs mm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 96.14 ± 0.60 A | −0.55 ± 0.04 A | 6.01 ± 0.16 A | 6.03 ± 0.16 A | 1.48 ± 0.01 C | - | 0.24 ± 0.01 B | 76.70 ± 0.03 B | 5.93 ± 0.31 A |

| F2 | 96.85 ± 0.10 A | −0.57 ± 0.01 A | 11.51 ± 0.22 B | 11.52 ± 0.22 B | 1.52 ± 0.01 D | 5.65 ± 0.05 A | 0.16 ± 0.02A | 30.50 ± 0.07 A | 14.25 ± 2.28 B |

| F3 | 83.50 ± 0.14 B | 4.54 ± 0.04 C | 23.38 ± 0.24 D | 23.82 ± 0.25 D | 1.38 ± 0.01 A | 22.08 ± 1.58 C | 0.15 ± 0.01 A | 21.40 ± 0.01 A | 18.00 ± 3.13 B |

| F4 | 89.58 ± 0.38 C | 1.96 ± 0.19 B | 13.88 ± 0.57C | 14.01 ± 0.60C | 1.43 ± 0.07 B | 10.55 ± 0.99 B | 0.18 ± 0.03 A | 17.80 ± 0.05 A | 28.14 ± 4.00 C |

| Films 1 | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 17.83 ± 3.55 A | 34.21 ± 0.45 A | 90.23 ± 2.06 A |

| F2 | 12.73 ± 2.48 B | 30.82 ± 1.89 B | 93.56 ± 3.14 A |

| F3 | 10.51 ± 2.72 B | 27.18 ± 2.36 B | 94.07 ± 1.18 A |

| F4 | 13.59 ± 1.64 B | 31.26 ± 1.65 B | 56.29 ± 3.94 B |

| Films 1 | E. coli (log10 UFC cm−2) | S. aureus (log10 UFC cm−2) |

|---|---|---|

| Inoculum | 6.25 ± 0.15 A | 5.06 ± 0.08 B |

| F1 | 6.58 ± 0.06 A | 5.65 ± 0.04 A |

| F2 | 6.70 ± 0.04 B | 5.85 ± 0.03 A |

| F3 | 4.29 ± 0.19 B | 5.33 ± 0.08 B |

| F4 | 3.73 ± 0.10 C | 4.64 ± 0.12 C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro, L.E.N.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Müller, C.M.; Gasparrini, L.J.; Alves, H.J.; Kieling, D.D.; Takabayashi, C.R.; Colpini, L.M.S. Development of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Films Functionalized with Ag/TiO2 Catalysts for Antimicrobial and Packaging Applications. Appl. Nano 2025, 6, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040028

Castro LEN, Sganzerla WG, Müller CM, Gasparrini LJ, Alves HJ, Kieling DD, Takabayashi CR, Colpini LMS. Development of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Films Functionalized with Ag/TiO2 Catalysts for Antimicrobial and Packaging Applications. Applied Nano. 2025; 6(4):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040028

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro, Luiz Eduardo Nochi, William Gustavo Sganzerla, Carina Mendonça Müller, Lázaro José Gasparrini, Helton José Alves, Dirlei Diedrich Kieling, Cassia Reika Takabayashi, and Leda Maria Saragiotto Colpini. 2025. "Development of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Films Functionalized with Ag/TiO2 Catalysts for Antimicrobial and Packaging Applications" Applied Nano 6, no. 4: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040028

APA StyleCastro, L. E. N., Sganzerla, W. G., Müller, C. M., Gasparrini, L. J., Alves, H. J., Kieling, D. D., Takabayashi, C. R., & Colpini, L. M. S. (2025). Development of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Films Functionalized with Ag/TiO2 Catalysts for Antimicrobial and Packaging Applications. Applied Nano, 6(4), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040028