Timoshenko Theories in the Analysis of Cantilever Beams Subjected to End Mass and Dynamic End Moment

Abstract

1. Introduction

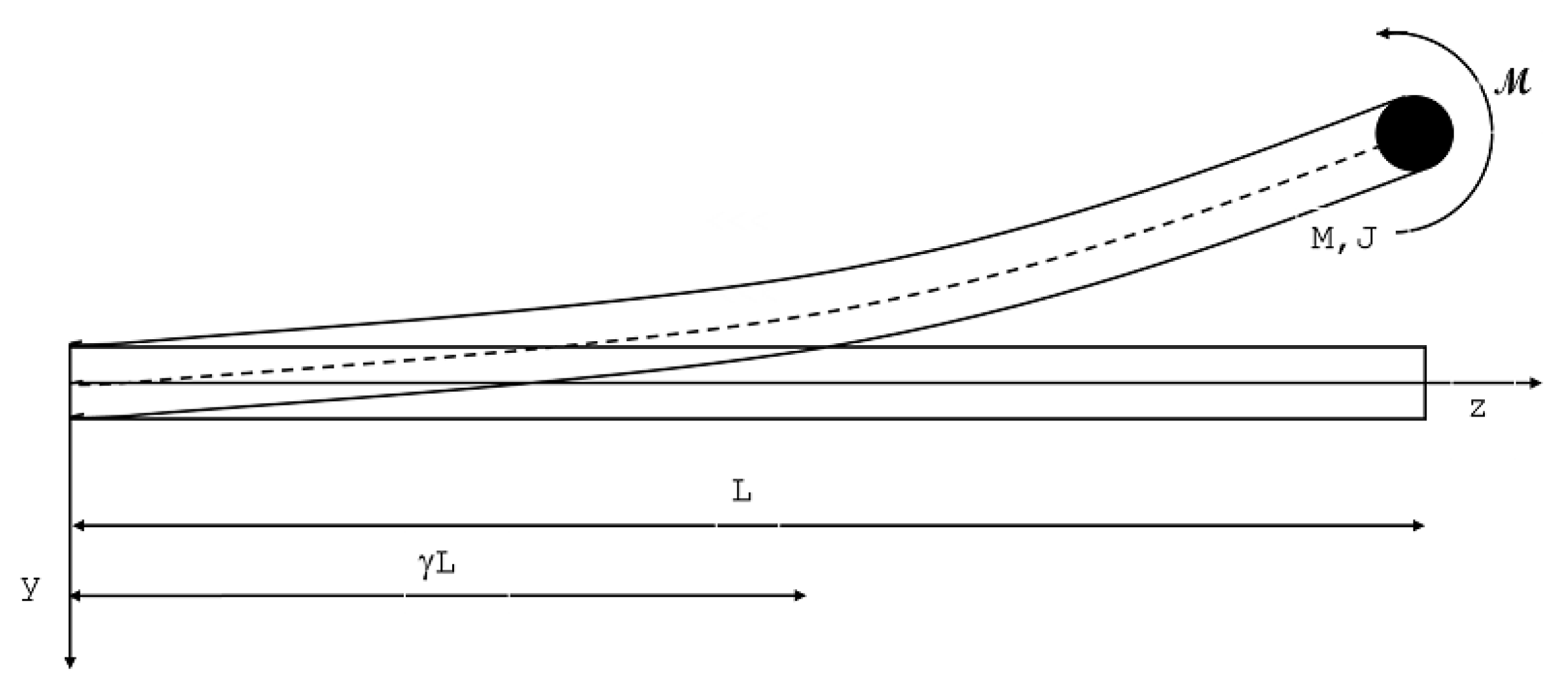

2. Theoretical Formulation of Classical Timoshenko Beam Theory

Auxiliary Functions for the Free Vibrations of a Timoshenko Beam: Classical Theory

3. Theoretical Formulation of Truncated Timoshenko Beam Theory

3.1. Theoretical Model

3.2. Auxiliary Functions for Free Vibrations of a Timoshenko Beam: Truncated Theory

4. Numerical Examples

4.1. Comparison of Solutions Obtained by Utilizing Classical and Truncated Theories

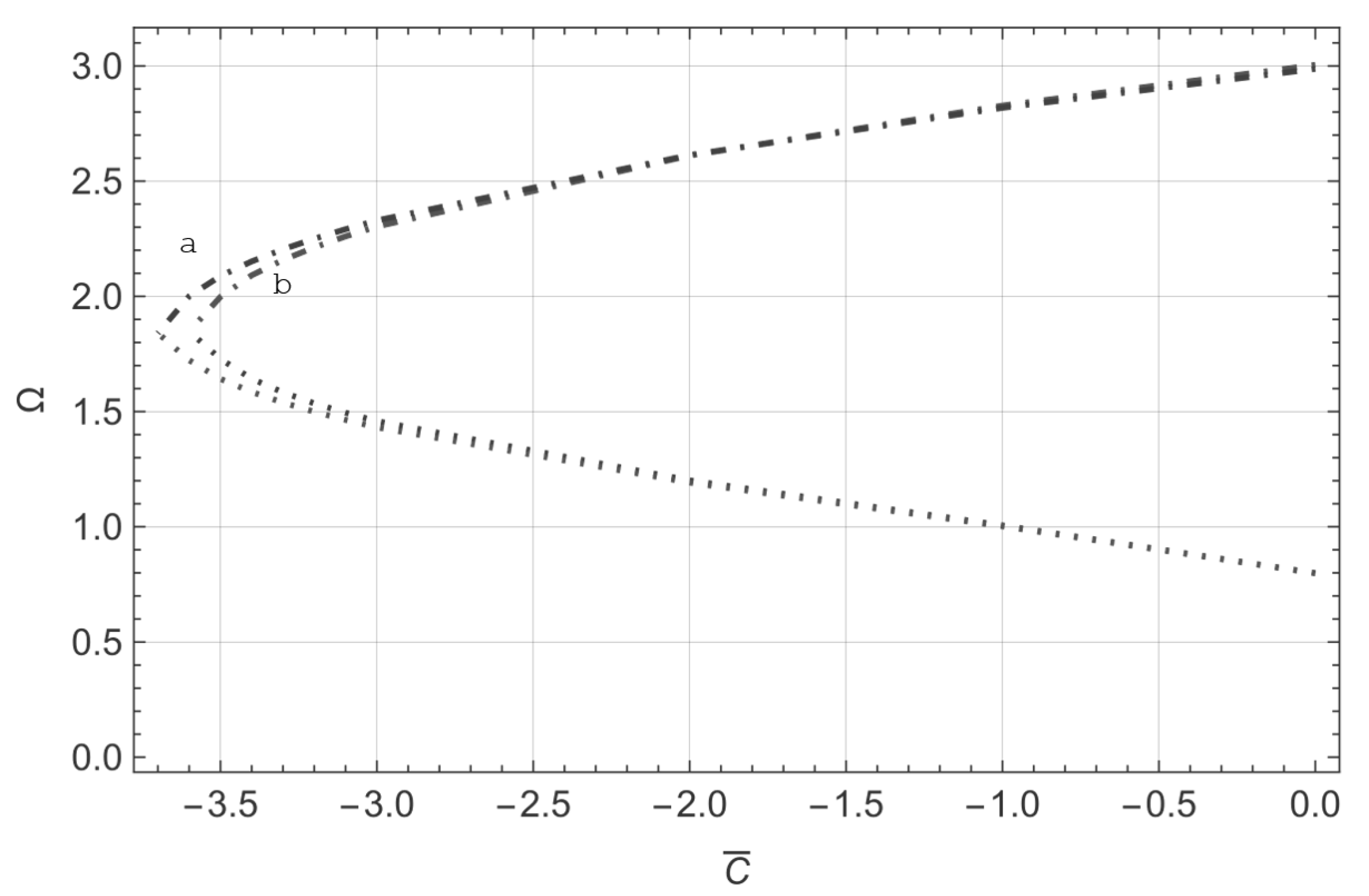

4.2. Dynamic Couple Proportional to Positive Curvature

4.3. Dynamic Couple Proportional to Negative Curvature

- (a)

- In the interval , instability in the structure occurs when the first and second eigenvalues become equal. Figure 4 illustrates this initial behavior for . Flutter instability, coinciding with the first and second dimensionless frequencies, occurs at . As shown in Figure 4, the first two frequencies converge while the third remains nearly unchanged.

- (b)

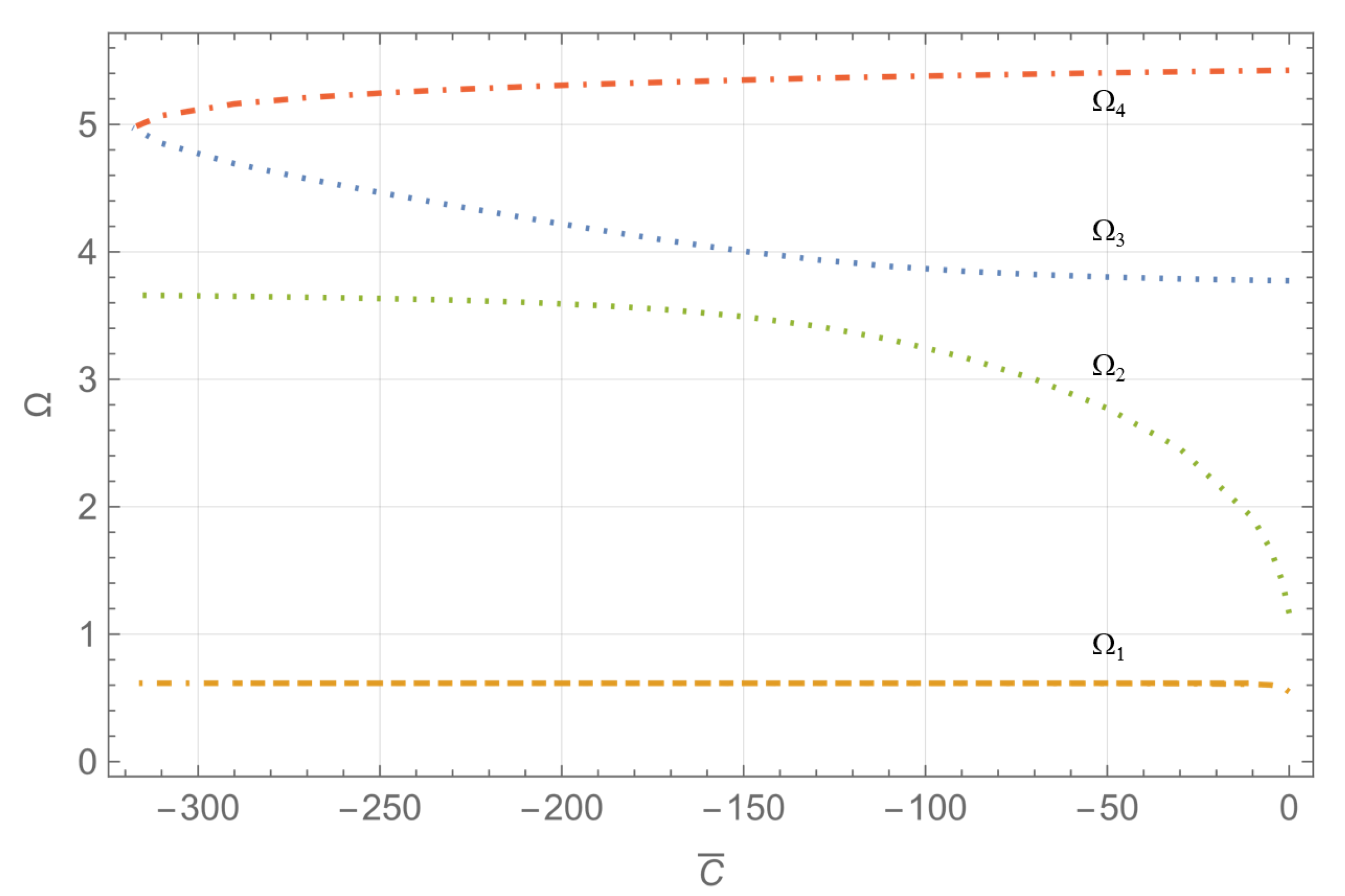

- In the interval , the structure loses stability when the second and third eigenvalues coincide. Figure 5 illustrates this second behavior for , where the second and third dimensionless frequencies align at . From Figure 5, it can be observed that, as approaches the upper bound of the first interval, the first eigenvalue tends to approach the second, but does not coincide with it, subsequently diverging. This behavior is also seen in the subsequent cases and at the transition points between intervals.

- (c)

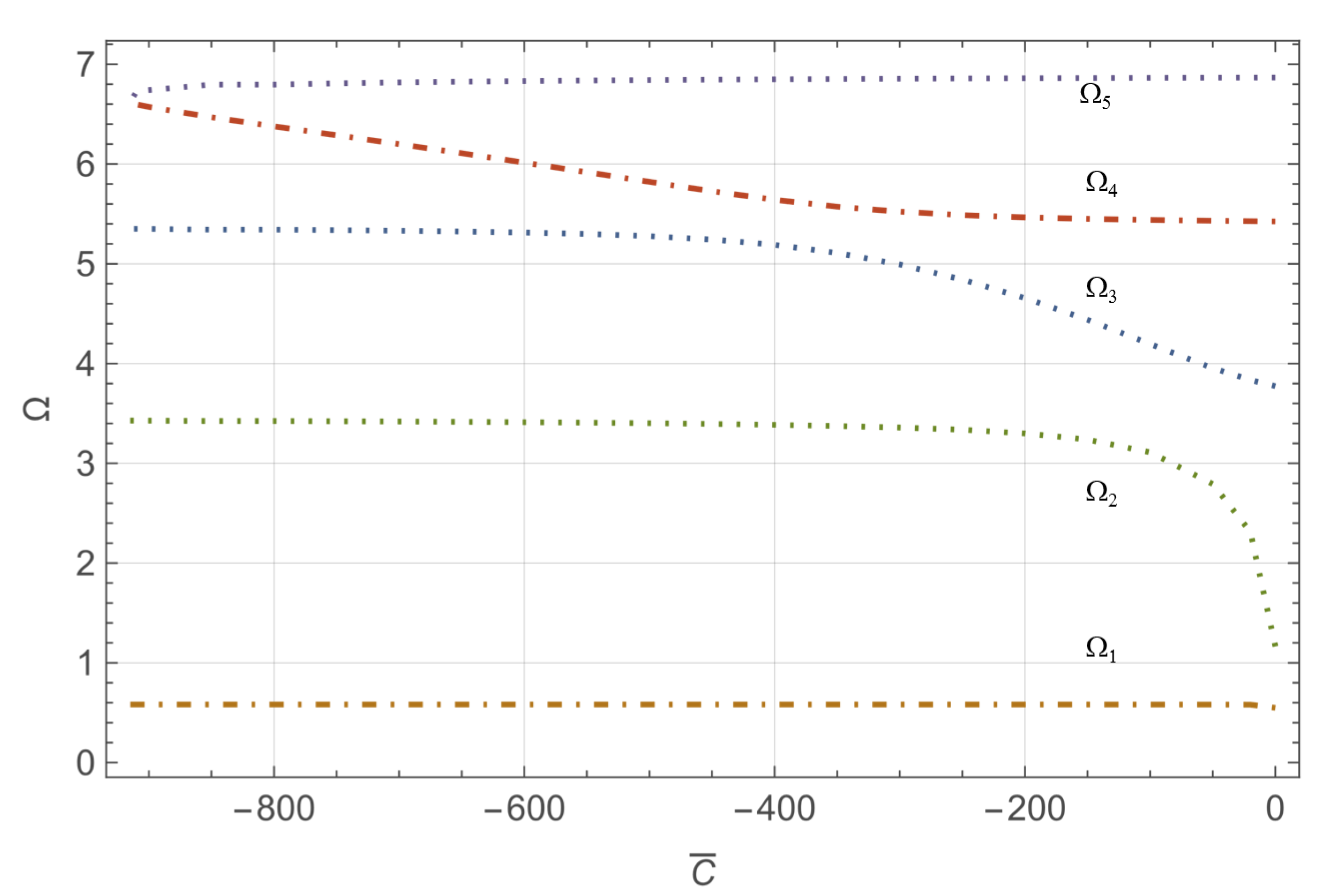

- In the interval , the structure loses stability when the third and fourth eigenvalues become equal. Figure 6 illustrates this third behavior for where the third and fourth dimensionless frequencies coincide at .

- (d)

- Finally, in the interval , the system loses stability as the fourth and fifth eigenvalues converge. Figure 7 illustrates this fourth behavior for , where the fourth and fifth dimensionless frequencies align at .

5. Conclusions

- -

- The curvature position affects the natural frequencies: as the non-dimensional curvature position increases, the first non-dimensional frequency also increases.

- -

- For a constant slenderness ratio, the initial non-dimensional frequency decreases as the curvature and its position increase.

- -

- When the dynamic couple is associated with positive curvature, the position of the measurement point has minimal influence on the critical value of the proportionality constant.

- -

- When the dynamic couple is linked to negative curvature, as the measurement point moves from the fixed end to the free end, the instability mode transitions sequentially from the first to the fourth flutter instability mode. A notable observation is that a constant change in the measurement point’s position can lead to multiple stability shifts, producing various instability modes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- von Kármán, T. On the Stability of Thin Plates. In Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers; Gilat, R., Sills-Banks, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Timoshenko, S.P. On the Stability of Columns and Beams Under the Action of Axial Forces Varying with Time. In Proceedings of the Royal Society A; Royal Society: London, UK, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.P. Divergence and Flutter of a Cantilever Rod with an Intermediate Spring Support. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1995, 32, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong Jo, R.; Kazuo, K.; Yoshihiko, S. Dynamic stability of Timoshenko columns subjected to subtangential forces. Comput. Struct. 1998, 68, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kim, J.H. Effect of Crack on the Dynamic Stability of a Free-Free Beam Subjected to a Follower Force. J. Sound Vibr. 2000, 233, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elishakoff, I. Controversy Associated With the So-Called ‘‘Follower Forces’’: Critical Overview. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2005, 58, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddemi, S.; Caliò, I.; Cannizzaro, F. Flutter and divergence instability of the multi-cracked cantilever beam-column. J. Sound Vibr. 2014, 333, 1718–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha1, P.; Singh, T. Dynamic Instability of Follower Forced Euler Bernoulli Cantilever Beam with Tip Mass. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.10264. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K. Effects of the concentrated mass and elastic support on dynamic and flutter behaviors of panel structures. Int. J. Mech. Mat. Design 2024, 20, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabian, M.; Ahmadian, H.; Fathi, R. Flutter Instability of Timoshenko Cantilever Beam Carrying Concentrated Mass on Various Locations. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2016, 13, 3005–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abdullatif, M.; Mukherjee, R. Effect of intermediate support on critical stability of a cantilever with non-conservative loading: Some new results. J. Sound Vibr. 2020, 485, 115564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, M.T.; Hashemi, S.M. Dynamic Finite Element Modelling and Vibration Analysis of Prestressed Layered Bending–Torsion Coupled Beams. Appl. Mech. 2022, 3, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, F. Dynamic analysis of axially loaded cantilever shear-beam under large deflections with small rotations. Earthq. Engng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 52, 2251–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.C.; Ma, W.L.; Li, X.F. Stability of cantilever on elastic foundation under a subtangential follower force via shear deformation beam theories. Thin-Walled Struct. 2020, 154, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Lippiello, M.; Armenio, G.; De Biase, G.; Savalli, S. Dynamic analogy between Timoshenko and Euler–Bernoulli beams. Acta Mech. 2020, 231, 4819–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Lippiello, M. Closed-form solutions for vibrations analysis of cracked Timoshenko beams on elastic medium: An analytically approach. Eng. Struct. 2021, 236, 111946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Lippiello, M.; Elishakoff, I. Variational Derivation of Truncated Timoshenko-Ehrenfest Beam Theory. J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2022, 8, 996–1004. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Lippiello, M.; Onorato, A.; Elishakoff, I. Free vibration of single-walled carbon nanotubes using nonlocal truncated Timoshenko-Ehrenfest beam theory. Appl. Mech. 2023, 4, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Elishakoff, I.; Onorato, A.; Lippiello, M. Dynamic Analysis of a Timoshenko–Ehrenfest Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube in the Presence of Surface Effects: The Truncated Theory. Appl. Mech. 2023, 4, 1100–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Elishakoff, I.; Lippiello, M. A Comparison of Three Theories for Vibration Analysis for Shell Models. Civil Eng. 2025, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Ceraldi, C.; Martin, H.D.; Onorato, A.; Piovan, M.T.; Lippiello, M. The Influence of Mass on Dynamic Response of Cracked Timoshenko Beam with Restrained End Conditions: The Truncated Theory. Appl. Mech. 2025, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.A.; Elishakoff, I.; Lippiello, M. Free-Vibration Analysis for Truncated Uflyand–Mindlin Plate Models: An Alternative Theoretical Formulation. Vibration 2024, 7, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S. The Mathematica 8; Wolfram Media Cambridge: Cambridge, UK; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullastif, M.; Mukherjce, R. Divergence and flutter instabilities of a cantilever beams subjected to a terminal dynamic moment. J. Sound Vibr. 2019, 455, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (TTT) | (TBT) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.548429 | 0.548432 |

| 0.1 | 0.533077 | 0.533079 |

| 0.2 | 0.516568 | 0.51570 |

| 0.3 | 0.498621 | 0.498623 |

| 0.4 | 0.478840 | 0.478841 |

| 0.5 | 0.456632 | 0.456633 |

| 0.6 | 0.431047 | 0.431048 |

| 0.7 | 0.400395 | 0.400396 |

| 0.8 | 0.361142 | 0.361143 |

| 0.9 | 0.303142 | 0.303142 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0.5484 | 0.5484 | 0.5484 | 0.5484 |

| 0.1 | 0.5331 | 0.5373 | 0.5417 | 0.5463 |

| 0.2 | 0.5166 | 0.5248 | 0.5339 | 0.5437 |

| 0.3 | 0.4986 | 0.5107 | 0.5245 | 0.5404 |

| 0.4 | 0.4788 | 0.4944 | 0.5131 | 0.5361 |

| 0.5 | 0.4566 | 0.4753 | 0.4989 | 0.5302 |

| 0.6 | 0.4310 | 0.4524 | 0.4816 | 0.5484 |

| 0.7 | 0.4004 | 0.4237 | 0.4562 | 0.5180 |

| 0.8 | 0.3611 | 0.3853 | 0.4210 | 0.4860 |

| 0.9 | 0.3031 | 0.3261 | 0.3620 | 0.4370 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0.6779 | 0.6779 | 0.6779 | 0.6779 |

| 0.1 | 0.6585 | 0.6645 | 0.6707 | 0.6772 |

| 0.2 | 0.6376 | 0.6494 | 0.6622 | 0.6763 |

| 0.3 | 0.6151 | 0.6322 | 0.6520 | 0.6751 |

| 0.4 | 0.5902 | 0.6124 | 0.6394 | 0.6735 |

| 0.5 | 0.5625 | 0.5892 | 0.9237 | 0.6713 |

| 0.6 | 0.5306 | 0.5612 | 0.6032 | 0.6680 |

| 0.7 | 0.4925 | 0.5260 | 0.5753 | 0.6627 |

| 0.8 | 0.4439 | 0.4789 | 0.5341 | 0.6530 |

| 0.9 | 0.3724 | 0.4057 | 0.4629 | 0.6242 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0.7550 | 0.7550 | 0.7550 | 0.7550 |

| 0.1 | 0.7332 | 0.7401 | 0.7472 | 0.7546 |

| 0.2 | 0.7099 | 0.7233 | 0.7381 | 0.7541 |

| 0.3 | 0.6846 | 0.7043 | 0.7270 | 0.7535 |

| 0.4 | 0.6569 | 0.6824 | 0.7135 | 0.7527 |

| 0.5 | 0.6259 | 0.6566 | 0.6965 | 0.7516 |

| 0.6 | 0.5903 | 0.6255 | 0.6743 | 0.7500 |

| 0.7 | 0.5479 | 0.5865 | 0.6439 | 0.7471 |

| 0.8 | 0.4141 | 0.5341 | 0.5988 | 0.7417 |

| 0.9 | 0.4937 | 0.4527 | 0.5200 | 0.7259 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0.7981 | 0.7981 | 0.7981 | 0.7981 |

| 0.1 | 0.7981 | 0.7824 | 0.7900 | 0.7978 |

| 0.2 | 0.7504 | 0.7647 | 0.7804 | 0.7974 |

| 0.3 | 0.7236 | 0.7447 | 0.7689 | 0.7971 |

| 0.4 | 0.6943 | 0.7215 | 0.7548 | 0.7965 |

| 0.5 | 0.6615 | 0.6943 | 0.7370 | 0.7958 |

| 0.6 | 0.6239 | 0.6615 | 0.7138 | 0.7946 |

| 0.7 | 0.5790 | 0.6203 | 0.6819 | 0.7927 |

| 0.8 | 0.5217 | 0.5649 | 0.6344 | 0.7889 |

| 0.9 | 0.4376 | 0.4789 | 0.5514 | 0.7778 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Rosa, M.A.; Lippiello, M. Timoshenko Theories in the Analysis of Cantilever Beams Subjected to End Mass and Dynamic End Moment. Appl. Mech. 2025, 6, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040087

De Rosa MA, Lippiello M. Timoshenko Theories in the Analysis of Cantilever Beams Subjected to End Mass and Dynamic End Moment. Applied Mechanics. 2025; 6(4):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040087

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Rosa, Maria Anna, and Maria Lippiello. 2025. "Timoshenko Theories in the Analysis of Cantilever Beams Subjected to End Mass and Dynamic End Moment" Applied Mechanics 6, no. 4: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040087

APA StyleDe Rosa, M. A., & Lippiello, M. (2025). Timoshenko Theories in the Analysis of Cantilever Beams Subjected to End Mass and Dynamic End Moment. Applied Mechanics, 6(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040087