The Use of Composite 3D Printing in the Design of Optomechanical Components

Abstract

1. Introduction

- FFF or resin print using blends—fiberless materials.

- FFF using crushed fiber-filled filaments (discontinuous fiber reinforcement).

- FFF with continuous fiber reinforcement systems.

2. Methodology

2.1. Three-Dimensional Printing Materials and Parameters

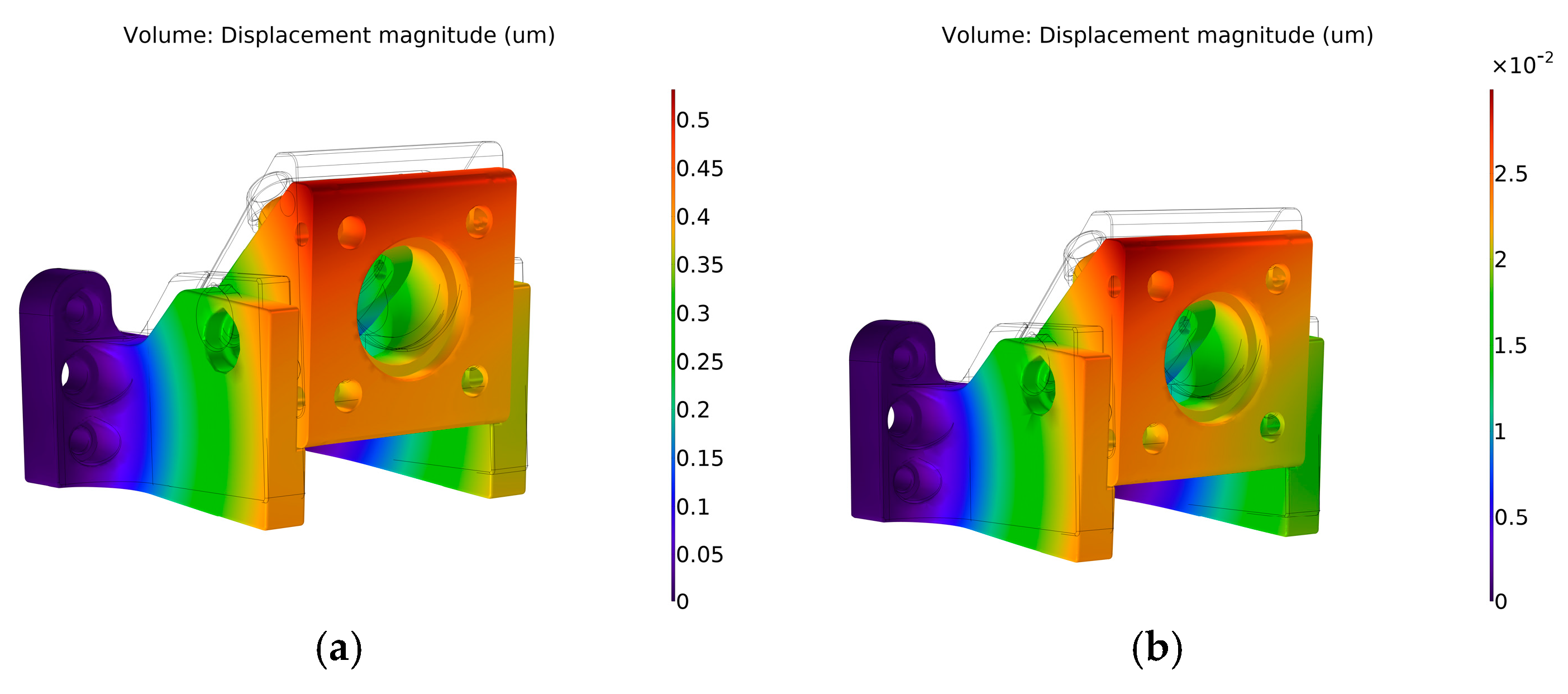

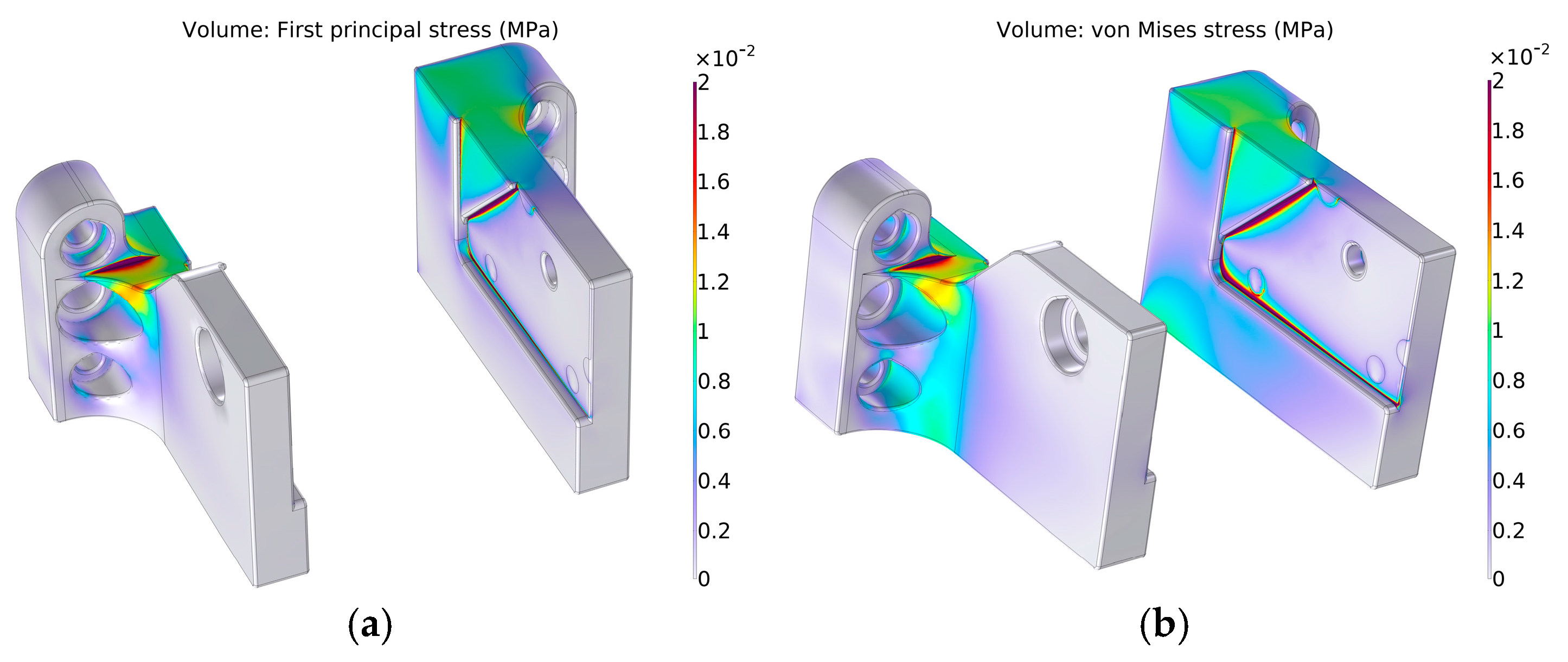

2.2. Computational Methodology

2.3. Tensile Testing Methodology

3. Results

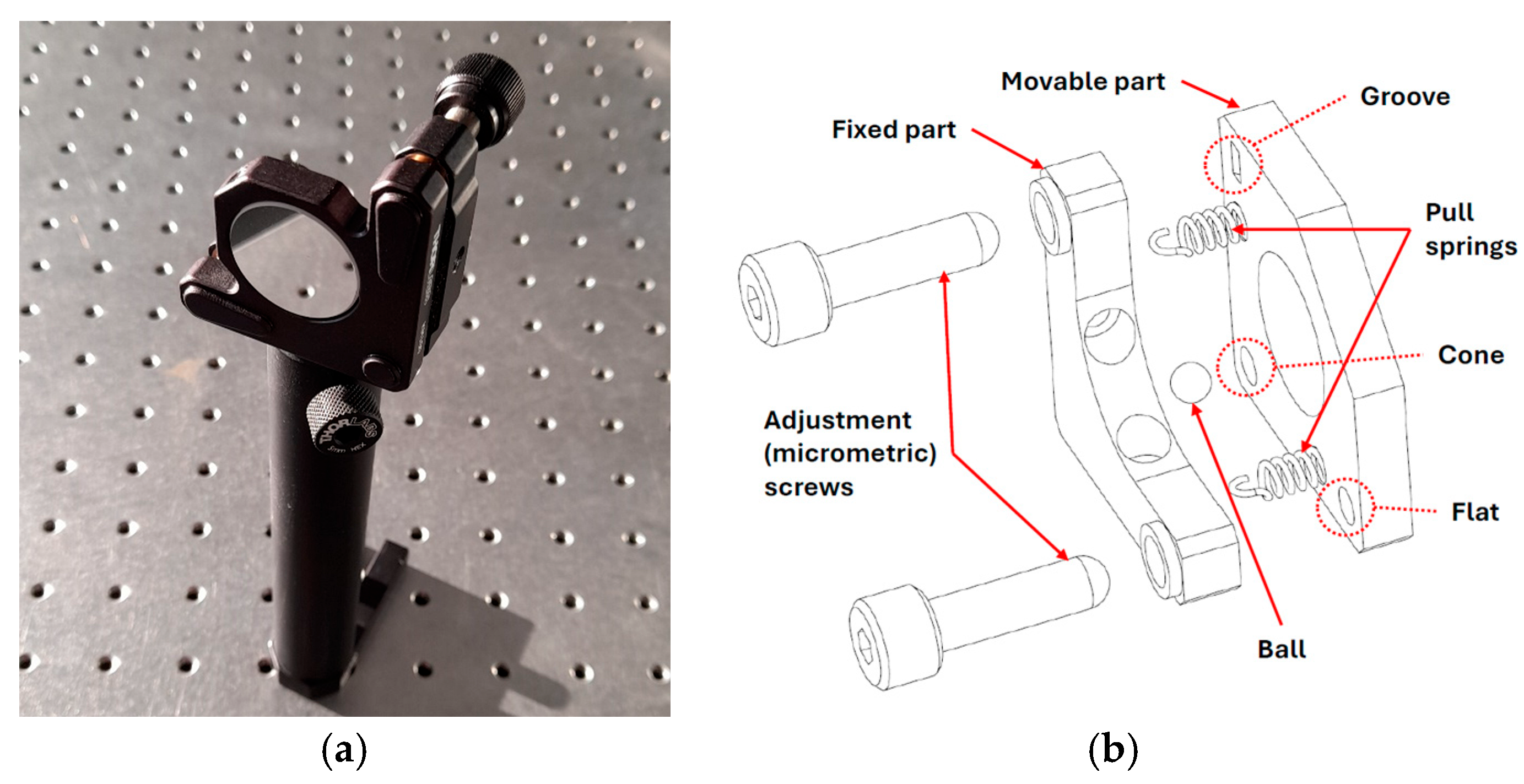

3.1. Optomechanical Components—Classical vs. Printed

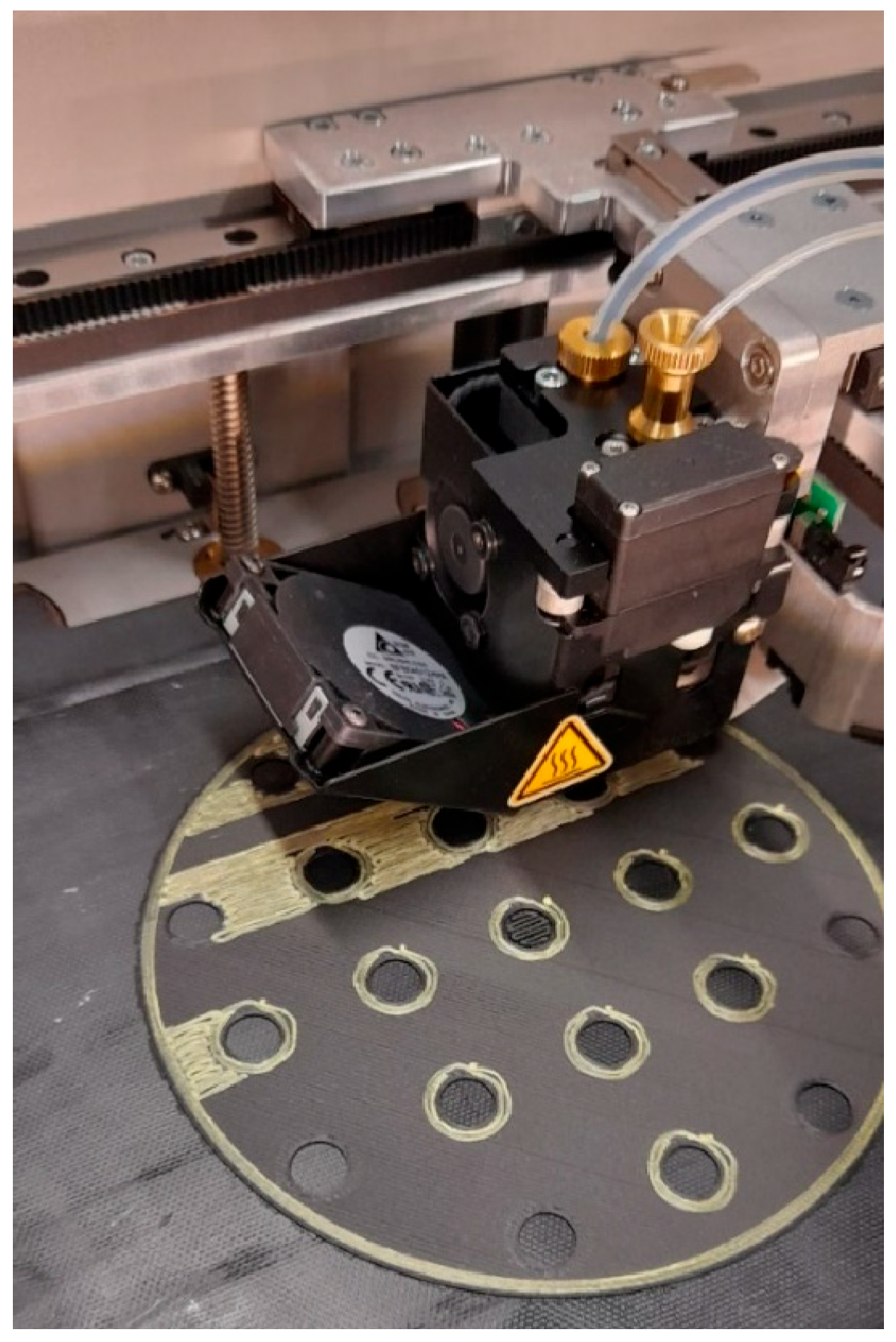

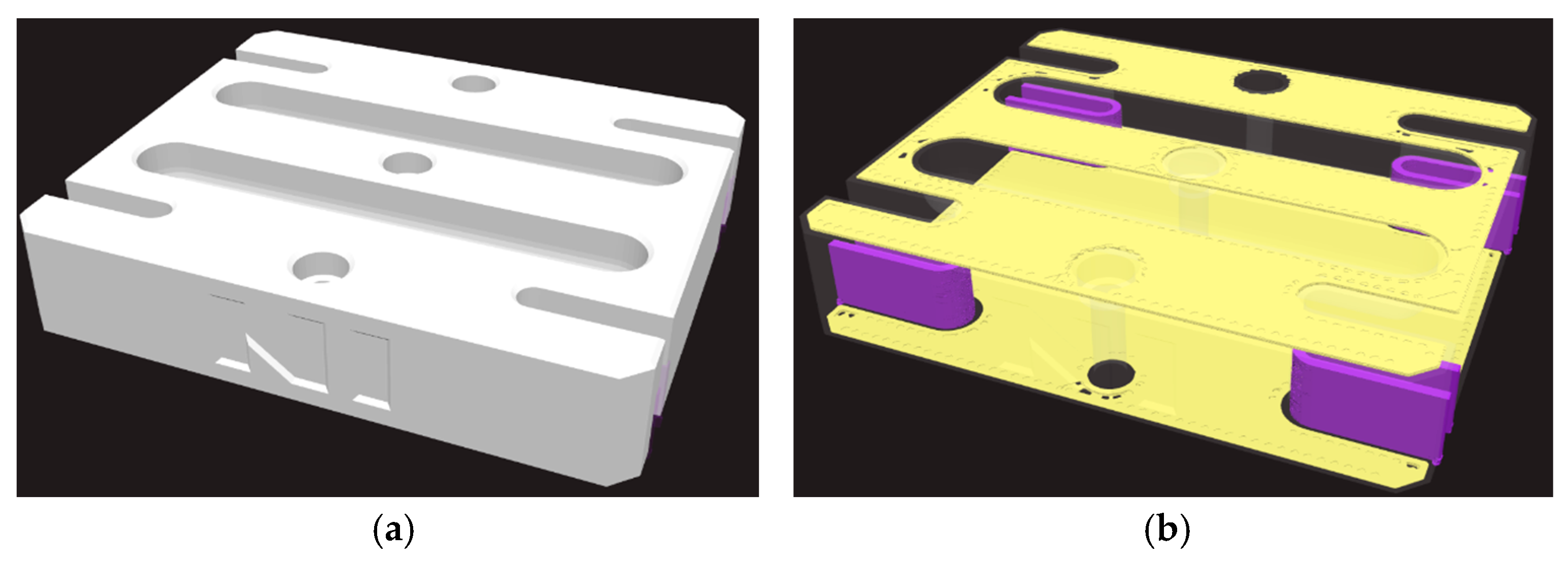

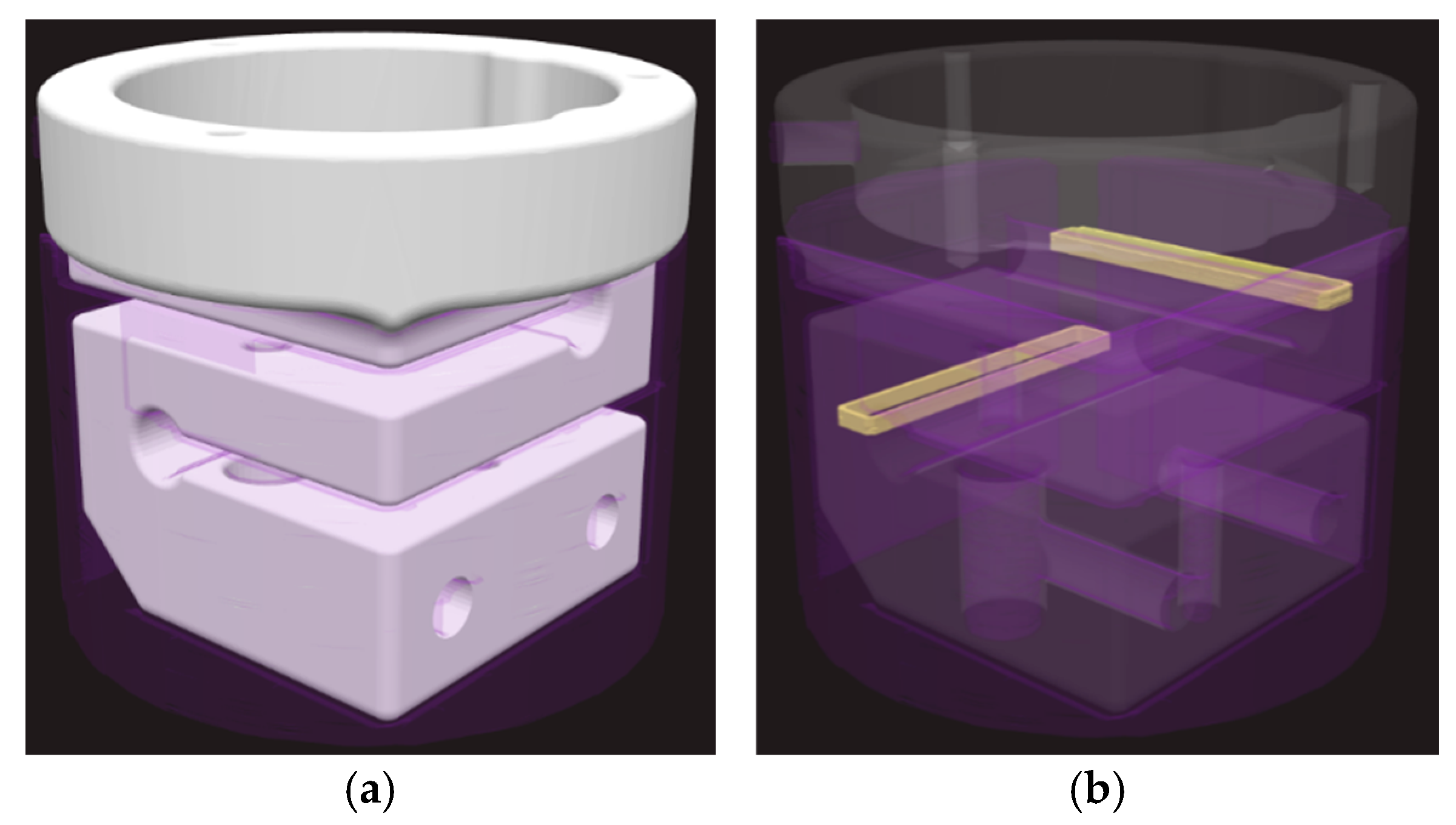

3.2. Printing with Continuous Reinforcement

3.3. Practical Use of 3D Printing for Laser System’s Optomechanics

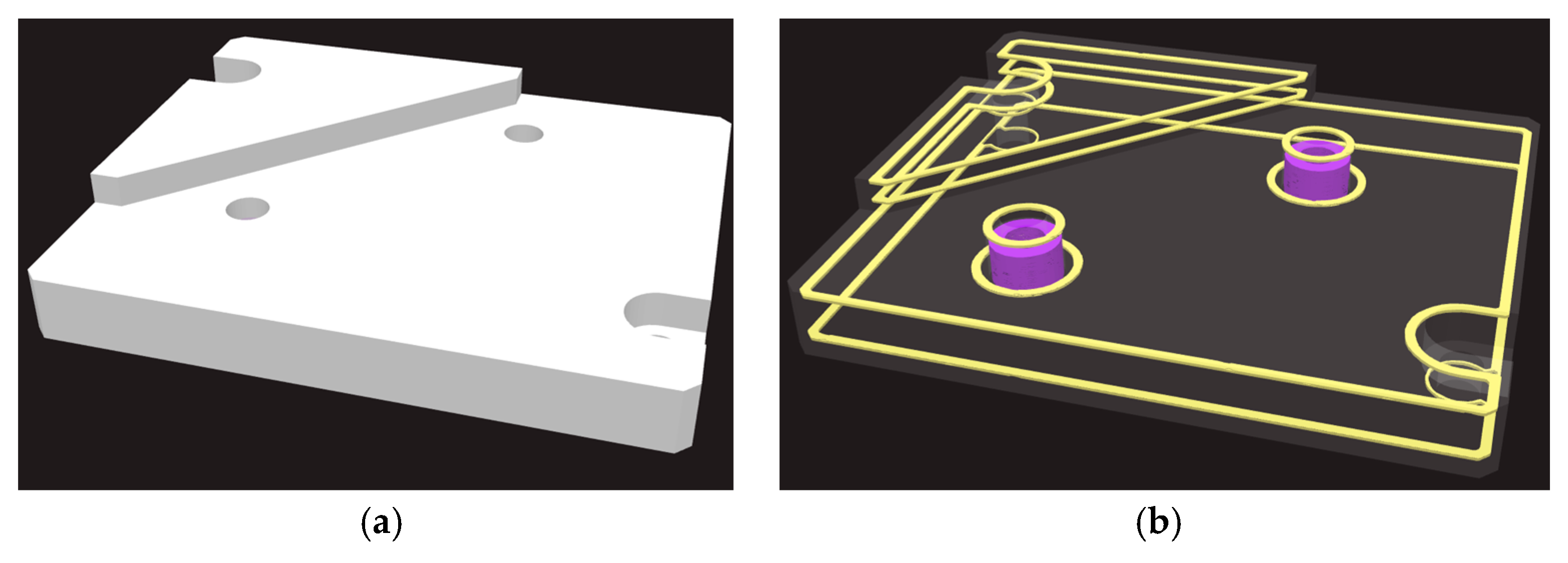

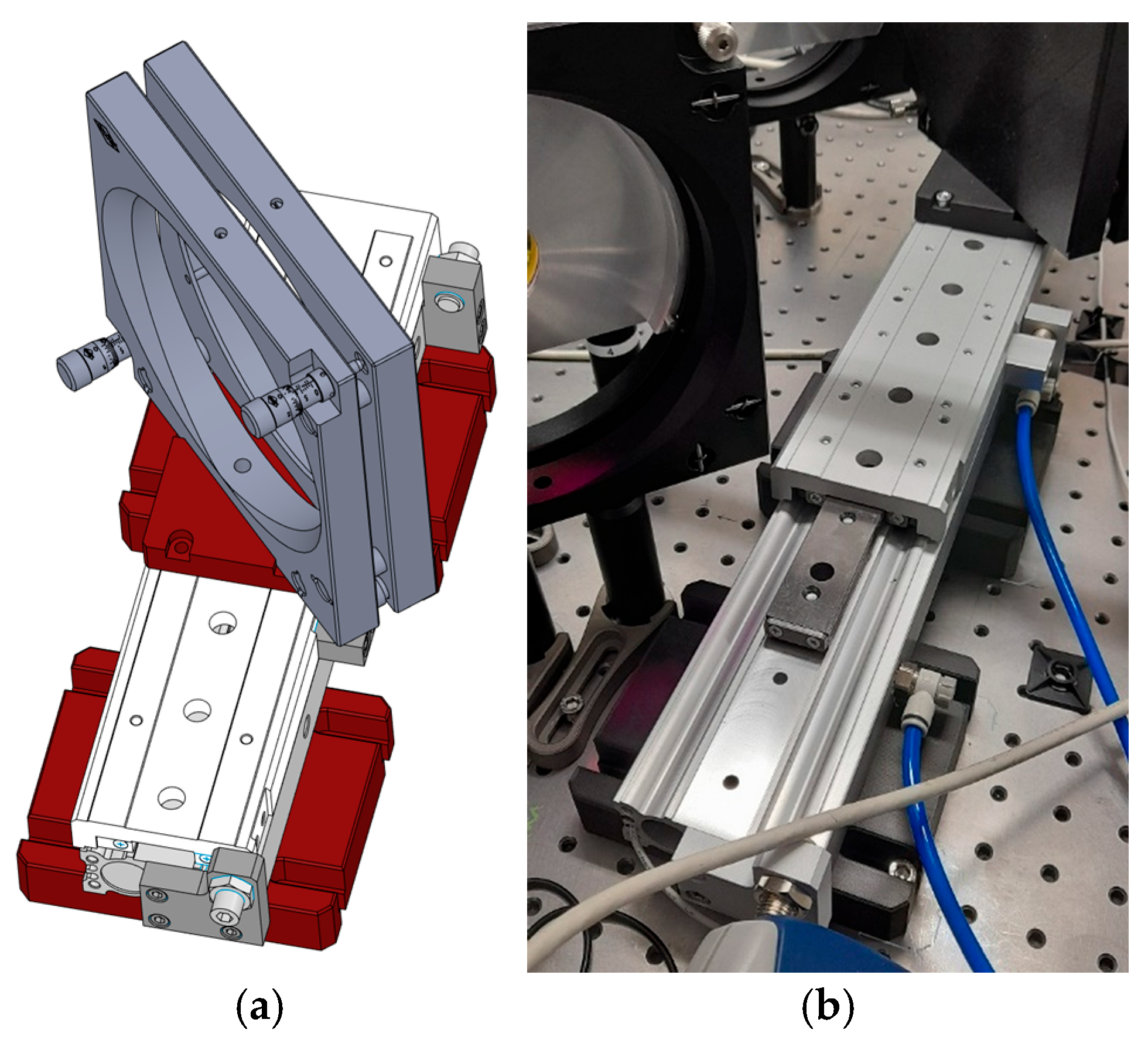

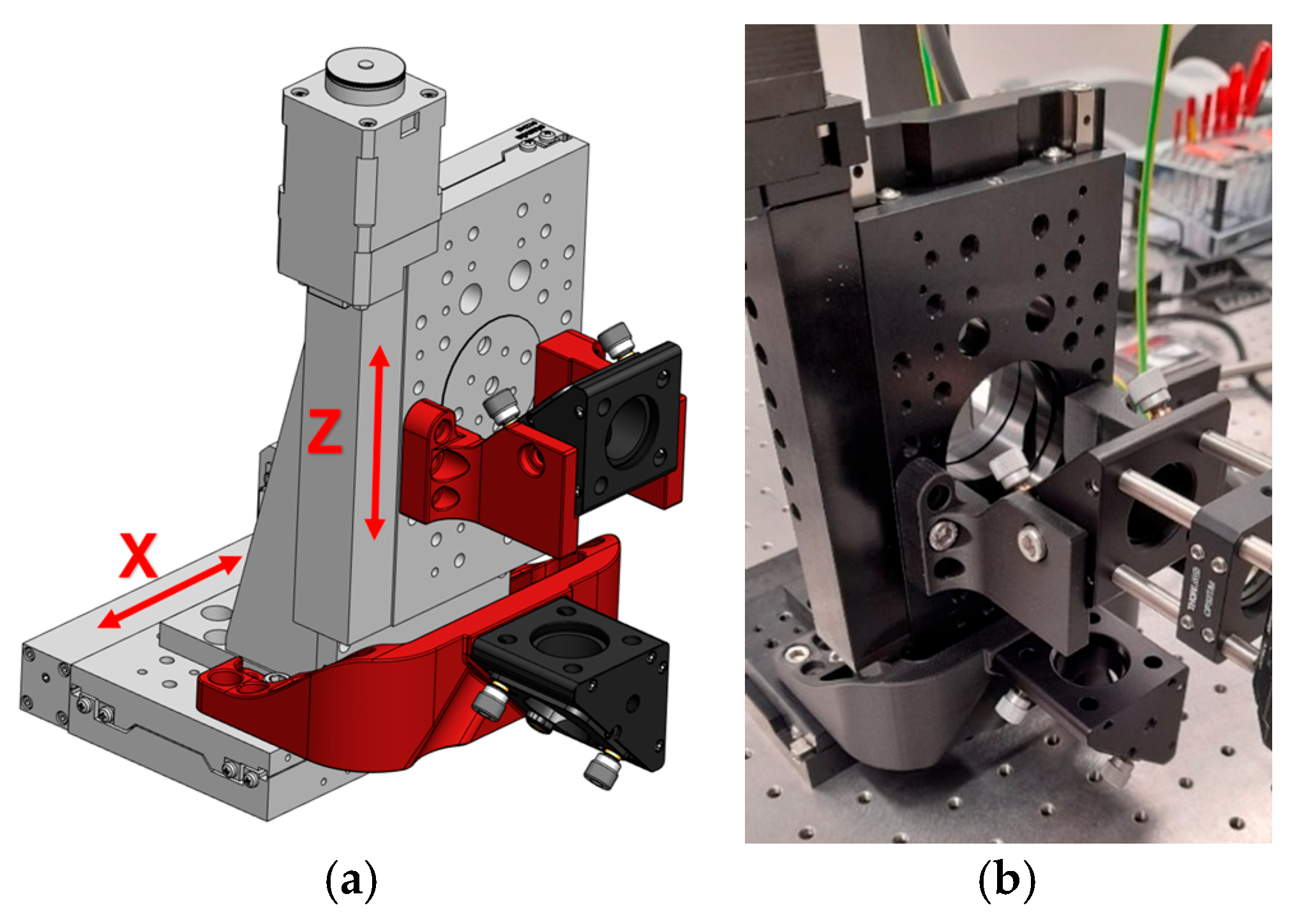

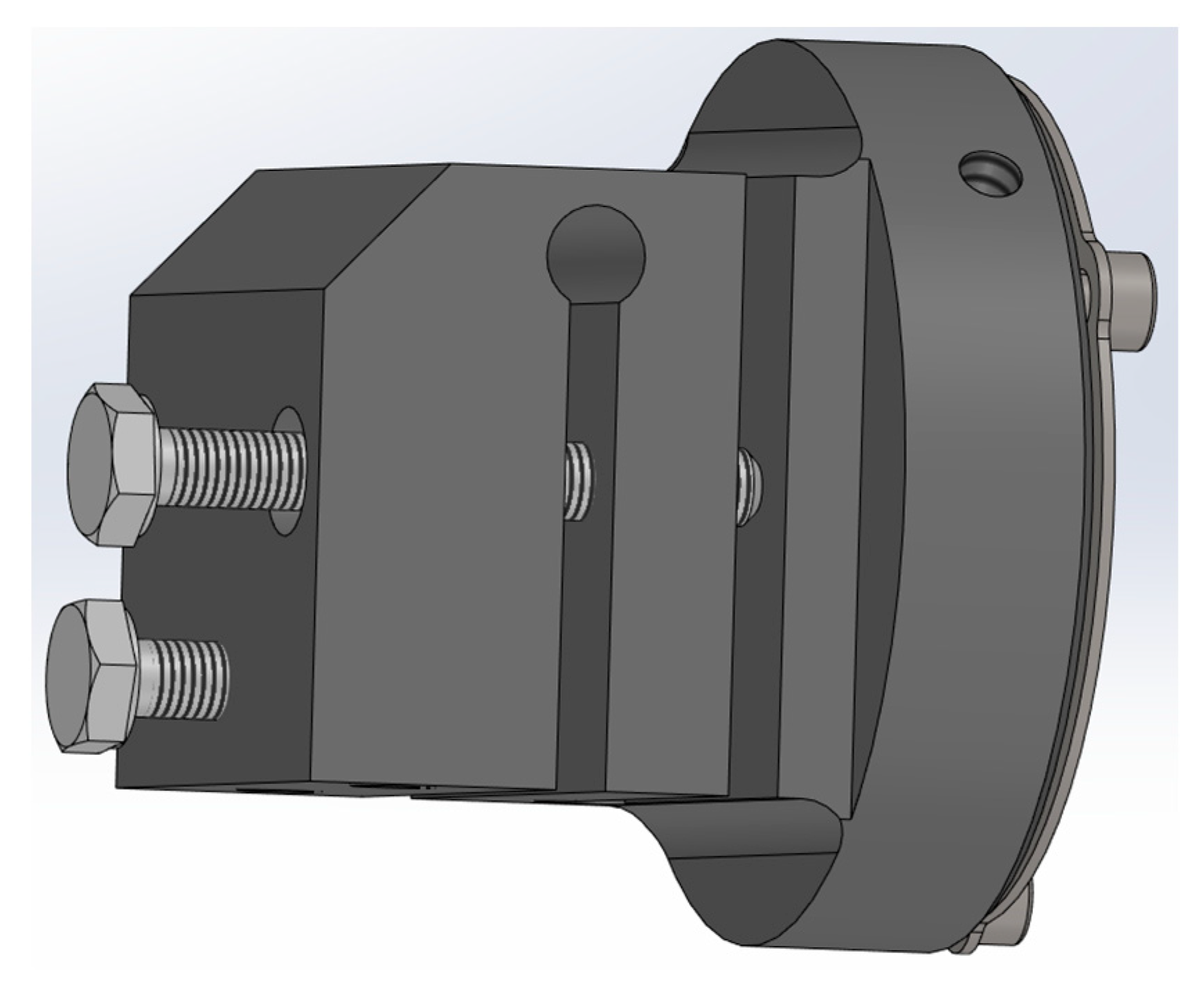

3.3.1. Design of Lightweight and Rigid Parts

3.3.2. Design of Elements for Shielding Stray Light

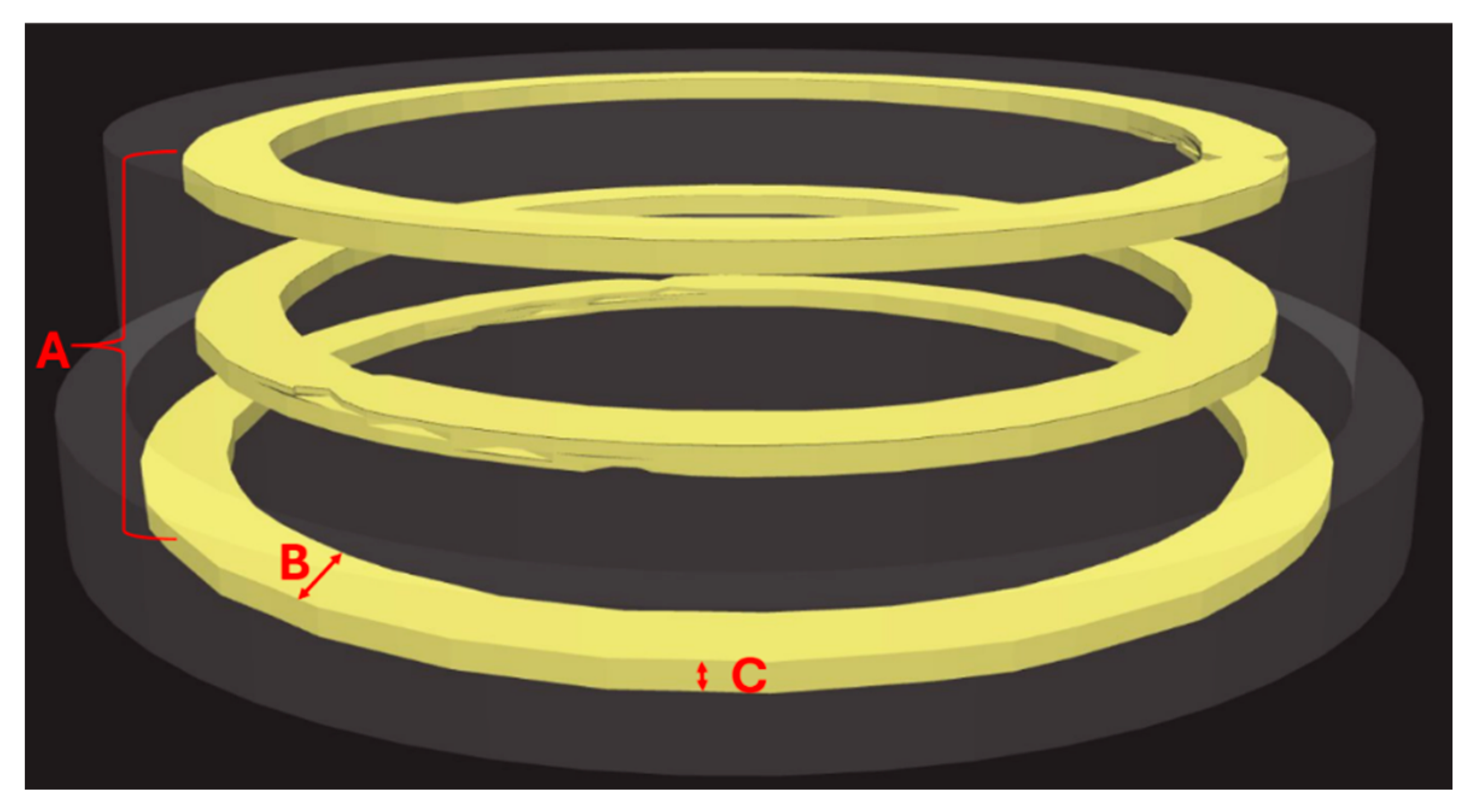

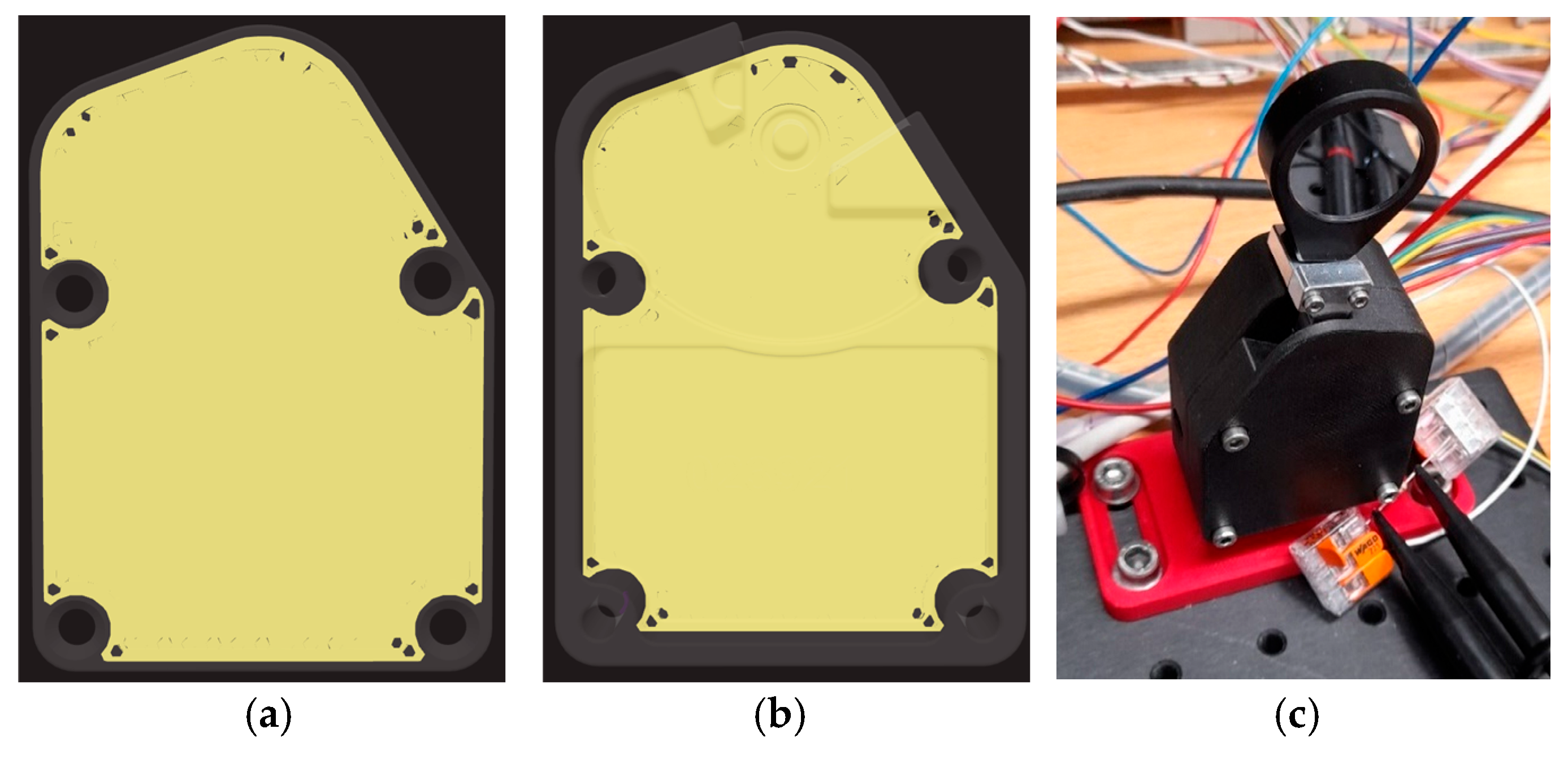

3.3.3. Design of Flexible Elements

3.3.4. Design of Parts for Compact Replacement of Common Optomechanics

4. Discussion

4.1. Benefits of Composite 3D Printing

4.2. Limitations of Composite 3D Printing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAS | Czech Academy of Sciences |

| CFRP | continuous fiber-reinforced polymer |

| FFF | fused filament fabrication |

| CFR | continuous filament reinforcement |

| CFF | continuous filament fabrication |

| CFC | composite fiber coextrusion |

| PMC | polymer matrix composite |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| PP | polypropylene |

| ABS | acrylonitrile butadiene styrene |

| PET-G | polyethylene terephthalate glycol |

| ASA | acrylonitrile styrene acrylate |

| PCTG | polycyclohexylenedimethylene terephthalate glycol |

| UV | ultraviolet |

| CTE | coefficient of thermal expansion |

| PEKK | polytherketoneketone |

| CAM | camera |

References

- DragonPlate. A Brief History of Carbon Fiber. Dragonplate.com. 2019. Available online: https://dragonplate.com/a-brief-history-of-carbon-fiber (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Chapman, A. The Complete History of 3D Printing. UltiMaker. 29 July 2022. Available online: https://ultimaker.com/learn/the-complete-history-of-3d-printing/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Blanco, I. The Use of Composite Materials in 3D Printing. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Gou, J.; Hui, D. 3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 110, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai Saran, O.; Prudhvidhar Reddy, A.; Chaturya, L.; Pavan Kumar, M. 3D printing of composite materials: A short review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 64 Pt 1, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, K.; Guo, H.; He, M.; Shi, X.; Guo, Y.; Kong, J.; Gu, J. Advances in 3D printing for polymer composites: A review. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, K.; Neto, V.; Peng, Y.; Valente, R.; Ahzi, S. Interfacial behaviors of continuous carbon fiber reinforced polymers manufactured by fused filament fabrication: A review and prospect. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2022, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, L.G.; Longana, M.L.; Yu, H.; Woods, B.K.S. An investigation into 3D printing of fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 22, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainless Steel PLA|Metal-Filled PLA Filament. Protoplant, Makers of Protopasta. 2024. Available online: https://proto-pasta.com/products/stainless-steel-pla (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Prusament PETG Magnetite 40% Grey 1 kg. Prusa3D by Josef Prusa. 2025. Available online: https://www.prusa3d.com/product/prusament-petg-magnetite-40-grey-1kg/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Terrafilum. 3D Printing Composite Materials. Terrafilum. 7 June 2023. Available online: https://www.terrafilum.com/products/composite/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- PLA Special Fill Filaments—Metal & Wood Enhanced PLA|colorFabb. Colorfabb.com. 2025. Available online: https://colorfabb.com/filaments/materials/pla-filaments/pla-special-fill (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Quality BIOFIL Filaments from the Czech Manufacturer Print with Smile. 2024. Available online: https://printwithsmile.cz/gb/biofil/348-biofil-175-mm-wood-500-g-8594196455192.html (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Print with Smile 3D Filament PETG Made of Premium Materials. 2024. Print with Smile. Available online: https://printwithsmile.cz/gb/pet-g/397-pet-g-v0-175-mm-white-1-kg-8594196452306.html (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Daher, R.; Ardu, S.; di Bella, E.; Krejci, I.; Duc, O. Efficiency of 3D printed composite resin restorations compared with subtractive materials: Evaluation of fatigue behavior, cost, and time of production. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liqcreate Composite-X | Strong Engineering Resin for 3D-Printing. Liqcreate.com. 2025. Available online: https://www.liqcreate.com/product/composite-x/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Print With Smile 3D Filament PETG CARBON FIBRE Made of Premium Materials. 2022. Available online: https://printwithsmile.cz/gb/composite-filaments/211-pet-g-carbon-fiber-black-500-g-175-m-8594196452511.html (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- PA12—CF15 is an Innovative 3D Printing Filament from Print with Smile. 2022. Available online: https://printwithsmile.cz/gb/3d-filamenty/392-pa12-cf15-500g-8594196459039.html (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- ASA Kevlar. Spectrum Filaments—Spectrum Filaments—Polski Producent Filamentu 3D. 3 November 2022. Available online: https://spectrumfilaments.com/en/filament/asa-kevlar/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- PCTG+GF. Fiberlogy. 20 January 2025. Available online: https://fiberlogy.com/en/fiberlogy-filaments/pctg-gf-filament/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- PLA UVHT-C15—500 g. Print with Smile. 2024. Available online: https://printwithsmile.cz/gb/3d-filamenty/393-pla-uvht-c15-500-g-8594196459107.html (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Prusament PETG Carbon Fiber Black 1 kg. Prusa3D by Josef Prusa. 2025. Available online: https://www.prusa3d.com/product/prusament-petg-carbon-fiber-black-1kg/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Markforged. (n.d.). Onyx—Composite 3D Printing Material. Markforged. Available online: https://markforged.com/materials/plastics/onyx (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Print with Smile 3D filament ASA KEVLAR Made of High Quality Materials. 2024. Available online: https://printwithsmile.cz/gb/3d-filamenty/398-asa-kevlar-175-mm-850-g-black-8594196454300.html (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Different Nozzle Types|Prusa Knowledge Base. Prusa3d.com. 2024. Available online: https://help.prusa3d.com/article/different-nozzle-types_2193 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Structural Mechanics Module User’s Guide; COMSOL Multiphysics® v. 6.3; COMSOL AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024; pp. 65, 248, 274–288.

- ČSN EN ISO 527-2 (640604); Plasty–Stanovení Tahových Vlastností–Část 2: Zkušební Podmínky Pro Tvářené Plasty. TECHNOR print, s.r.o.: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2012.

- Vega—Ultra High-Performance Carbon Fiber Filled PEKK for 3D Printing Aerospace Parts. 2024. Markforged. Available online: https://markforged.com/materials/plastics/vega (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Threading the Needle with Ease: Minimum Fiber Feature Sizes. 2024. Markforged. Available online: https://markforged.com/resources/blog/threading-the-needle-with-ease (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Gonçalves, C.M.B.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Marrucho, I.M. Optical properties. In Poly(Lactic Acid): Synthesis, Structures, Properties, Processing and Applications, 1st ed.; Grossman, R.F., Nwabunma, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Thorlabs—CF175 Clamping Fork for Ø1.25. Thorlabs.com. 2023. Available online: https://www.thorlabs.com/thorproduct.cfm?partnumber=CF175#ad-image-0 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Thorlabs—RS1.5P/M Ø25.0 mm Pedestal Pillar Post, M6 Taps, L = 38 mm. Thorlabs.com. 2023. Available online: https://www.thorlabs.com/thorproduct.cfm?partnumber=RS1.5P/M (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Clamping Fork. Edmundoptics.com. 2015. Available online: https://www.edmundoptics.com/p/clamping-fork/44149/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Pedestal Post, Metric, 38.1 mm. Edmundoptics.com. 2015. Available online: https://www.edmundoptics.com/p/pedestal-post-metric-381mm/44131/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- 1.5 in. Pedestal Base Clamping Fork. Newport.com. 2025. Available online: https://www.newport.com/f/1.5-in-clamping-fork (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- 9953-M Optical Pedestal. Newport.com. 2025. Available online: https://www.newport.com/p/9953-M (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Datasheets. (n.d.). Markforged.com. Available online: https://markforged.com/datasheets (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Prusament PETG Jet Black 1 kg. Prusa3D by Josef Prusa. 2015. Available online: https://www.prusa3d.com/product/prusament-petg-jet-black-1kg/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

| Aluminium 6063-T83 | Printed Nylon with Kevlar Fiber | |

|---|---|---|

| Density [kg·m−3] | 2700 | 1150 |

| Young’s modulus [GPa] | 69 | 0.46–2.60 |

| Poisson’s ratio [-] | 0.33 | 0.4 |

| Nominal Load [kN] | 100 |

| Max. Test Speed [mm/min] | 600 |

| Speed Control Accuracy [%] | ±0.5 |

| Crosshead Resolution [μm] | 1 |

| Frame Stiffness [mm/N] | 1.6 × 10−6 |

| Force Range [kN] | 500–600 |

| Force Measurement Accuracy [%] | ±0.3 of value within range |

| Nominal Load [kN] | 100 |

| Max. Test Speed [mm/min] | 600 |

| Weight | Machined Al Alloy | Composite 3D Print |

|---|---|---|

| Attachment block | 841 g | 204 g |

| Reduction | 187 g | 51 g |

| Iteration | Supports in Gaps Required | Same Preloading of Flexible Elements | Angle Between Moving Forces and Reinforcement |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | YES | YES | 90° |

| #2 | NO | NO | 45° |

| #3 | NO | fundamentally YES | 45° |

| Solution | Clamping Fork | Pedestal Post | Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D print | - | - | USD 7.33 |

| Wound CFRP | - | - | USD 120–190 |

| ThorLabs | USD 12.58 (CF175) | USD 30.90 (RS1.5P/M) | USD 43.48 |

| Newport | USD 25.86 (SR-F) | USD 42.31 (9953-M) | USD 68.17 |

| Edmund Optics | USD 10.76 (#15-859) | USD 27.56 (#15-841) | USD 38.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Němcová, Š.; Heřmánek, J.; Crha, P.; Macúchová, K.; Němec, V.; Pobořil, R.; Tichý, T.; Uher, O.; Smrž, M.; Mocek, T. The Use of Composite 3D Printing in the Design of Optomechanical Components. Appl. Mech. 2025, 6, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040081

Němcová Š, Heřmánek J, Crha P, Macúchová K, Němec V, Pobořil R, Tichý T, Uher O, Smrž M, Mocek T. The Use of Composite 3D Printing in the Design of Optomechanical Components. Applied Mechanics. 2025; 6(4):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040081

Chicago/Turabian StyleNěmcová, Šárka, Jan Heřmánek, Pavel Crha, Karolina Macúchová, Václav Němec, Radek Pobořil, Tomáš Tichý, Ondřej Uher, Martin Smrž, and Tomáš Mocek. 2025. "The Use of Composite 3D Printing in the Design of Optomechanical Components" Applied Mechanics 6, no. 4: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040081

APA StyleNěmcová, Š., Heřmánek, J., Crha, P., Macúchová, K., Němec, V., Pobořil, R., Tichý, T., Uher, O., Smrž, M., & Mocek, T. (2025). The Use of Composite 3D Printing in the Design of Optomechanical Components. Applied Mechanics, 6(4), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech6040081