1. Introduction

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into medical practice is driving a transformative shift in healthcare, especially in oncology, where AI is increasingly instrumental in improving diagnostic accuracy, tailoring treatment regimens, and accelerating research. Cancer continues to rank among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with an estimated 18 million new cases and 10 million deaths reported annually (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) in recent years [

1]. Among the various types of cancer, breast cancer holds particular significance. It was the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in 2022, with more than 2.3 million new cases and approximately 670,000 deaths worldwide [

2]. Studies suggest that if current trends persist, new breast cancer cases will increase by 38%, whereas deaths may increase by 68% by 2050, reaching around 3.2 million new cases and 1.1 million annual deaths per year [

3]. In this context, the ability of AI to analyze large and complex datasets—including medical images, genetic information, and electronic health records—supports earlier breast cancer detection, better risk assessment, and personalized treatments guided by precision oncology, ultimately helping reduce mortality and improve patient outcomes [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Deep neural networks (DNNs) have become the dominant approach for classifying breast lesions on ultrasound (US) images, demonstrating substantial improvements in diagnostic accuracy and clinical interpretability. Early post-2021 studies mainly adopted transfer learning with pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs) such as ResNet, DenseNet, and EfficientNet, achieving high accuracy and AUC in differentiating benign from malignant lesions on standard datasets. More recent work has moved toward customized DNN architectures tailored to ultrasound characteristics [

8,

9], such as attention-based CNNs, hybrid CNN–transformer classifiers, and multi-view fusion networks that integrate multiple ultrasound planes for improved context [

10]. Efforts to enhance the generalization include the use of synthetic data generation with GANs, domain adaptation, and ensemble learning, all of which have reduced overfitting and improved robustness across ultrasound vendors and imaging protocol [

11,

12]. Overall, DNN-based classifiers since 2021 have evolved from simple binary predictors to clinically oriented, interpretable systems, achieving performance comparable to experienced radiologists in controlled studies while moving steadily towards real-world validation.

Despite the promising performance of deep neural network (DNN) models for breast ultrasound classification, data security and patient privacy during model training remain significant challenges. DNNs require large, diverse datasets to achieve generalizable performance, but medical institutions are often reluctant to share raw ultrasound images due to strict privacy regulations such as HIPAA and GDPR, as well as ethical concerns about patient-identifiable information [

13,

14]. Traditional centralized training strategies aggregate data from multiple hospitals into a single repository. This increases the risk of data breaches, unauthorized access, and the potential misuse of sensitive medical records [

15]. Moreover, anonymization alone is insufficient, as re-identification attacks can sometimes reconstruct private features from model gradients or embeddings [

16].

Federated Learning (FL) offers an alternative solution by enabling decentralized training across multiple institutions without exposing raw data [

17]. In this paradigm, only model parameters or updates are shared between clients and a central server, preserving data locality and reducing privacy risks while maintaining model performance across diverse ultrasound domains. Recent studies have shown that Federated Learning (FL) can effectively train breast cancer classification networks across datasets from multiple hospitals, achieving accuracy comparable to centralized models while maintaining compliance with privacy-preserving regulations.

In this study, we propose, compare, and evaluate a federated learning (FL) framework designed to enhance medical image diagnosis while maintaining data privacy and computational efficiency. To demonstrate its effectiveness, we apply the proposed approach to multi-class breast cancer classification (normal, benign, and malignant) using ultrasound imaging as a representative case study. The major contributions of this work include (i) the implementation and comprehensive evaluation of a federated learning framework specifically configured for multi-class ultrasound breast cancer diagnosis and (ii) a comprehensive comparative analysis of centralized, local, and federated paradigms across three publicly available datasets to assess diagnostic performance and robustness. Furthermore, to extend our experimental analysis, we introduce an ablation study examining the effect of different loss functions on the best-performing model configuration. Experimental results confirm that the proposed FL framework effectively addresses the data accessibility and privacy challenges associated with centralized training while preserving high diagnostic accuracy and enabling secure, collaborative knowledge exchange among distributed medical institutions.

2. Related Work

Recent studies have investigated the integration of federated learning (FL) with deep learning models to improve the accuracy of breast cancer detection while preserving patient privacy. AlSalman et al. [

18] proposed a federated learning framework for breast cancer detection designed to classify mammogram images into malignant or benign categories. The model applied deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) and used multiple clients, such as hospitals and clinics, to train local models on their own datasets using local gradient descent. Afterwards, a global server aggregates the locally trained models into a weighted global model. The proposed model achieved a detection accuracy of 98.9% on three large-scale datasets—VinDr-Mammo, CMMD, and INBreast. Waly et al. [

19] applied a custom U-Net within a federated learning framework on two ultrasound datasets Baheya foundation in Egypt and Bus-set Dataset B, Spain. The model reached an accuracy of 89.5%, with precision values in the range of 0.54–0.58. The approach improved generalization and safe guarded data privacy, but the study faced limitations due to the small dataset size, ineffective pre-processing, and possible overfitting.

Recent studies have explored federated learning (FL) for breast cancer detection across imaging modalities such as mammography, ultrasound, and histopathology [

20]. Using different datasets (e.g., CBIS-DDSM, INbreast, BreakHis, BUSI, and MIAS) and deep models (e.g., CNNs, U-Net, ResNet, YOLO) the study achieved up to 99% accuracy. Hence, highlighting FL’s potential but the challenges were mainly the data heterogeneity and the lack of benchmarking standards. Gupta et al. [

21] proposed an ensemble FL framework using YOLOv6 with FedAvg and homomorphic encryption, attaining 98% accuracy on BreakHis and 97% on BUSI datasets. Their method outperformed centralized models while preserving privacy and enabling real-time inference, though it was limited by non-IID data and minimal clinical validation. Another study investigated the use of synthetic data generation to enhance the performance of FL [

22] by applying FedAvg and FedProx as baseline algorithms to classify benign and malignant lesions on multiple ultrasound datasets (BUSI, BUS-BRA, and UDIAT). By applying class-specific Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks, the approach achieves an average AUC of 0.92 for FedAvg and 0.95 for FedProx, improving performance for small and non-IID datasets. However, they noted that excessive reliance on synthetic images could negatively affect performance.

A hybrid federated framework combining convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with graph neural networks (GNNs) was introduced [

23]. The model was pre-trained in federated mode for spatial and geometric learning for the classification of breast tumors from multi-center ultrasound datasets, including BUSI, BUS, and OASBUD. This model achieved AUC-ROC values of 0.911, 0.871, and 0.767 for the datasets BUSI, BUS, and OASBUD, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating spatial and geometric learning across distributed sites. The comprehensive survey on cross-hospital collaborative research reviewed federated learning (FL) approaches across diverse datasets, including medical images, electronic health records (EHRs), and clinical data [

24]. This comprehensive survey discussed federated learning for research collaboration across hospitals, covering medical images (various types), EHRs, and clinical/administrative data. It assessed horizontal, vertical, and transfer learning, plus regulatory compliance (HIPAA, GDPR), privacy, and security. Major strengths included enabling multi-institutional research and preserving patient privacy. Weaknesses center on standardization challenges, vulnerability to security attacks, communication overhead, and incomplete clinical validation.

A web application called BreastInsight was developed using a federated learning framework for real-time breast cancer classification while preserving patient data privacy [

25]. The model trained on multiple imaging modalities, including histopathology (BreakHis) and ultrasound (BUSI) images, utilized four variations of the Swin Transformer (Tiny, Small, Base, and Large) as base models, with outputs aggregated by a Random Forest meta-learner. It achieved impressive accuracies of 99.14% for BreakHis and 98.27% for BUSI. However, the model encountered challenges such as high computational demands, sensitivity to noise, coordination overhead in federated learning, and limited interpretability of ensemble predictions.

Three deep learning approaches were compared, including centralized and federated schemes [

26]. These comprised individual AI models, feature space ensembles, and a hybrid model combining global Vision Transformer and CNN features. The models were evaluated on binary, multi-class, and BI-RADS classifications. In the centralized scenario, three clients aggregated their outputs using a global AI model. The federated model, trained on 734 cases with 41 risk factors, achieved accuracies of 98.65%, 97.30%, and 95.59% for binary, multi-class, and BI-RADS tasks, respectively, with an AUC of 0.970 [0.917–1.000]. However, the small dataset and ambiguity in borderline BI-RADS cases affected interpretability, as noted in the LIME analysis.

Shukla et al. [

27] proposed a privacy-preserving machine learning model that integrates Differential Privacy (DP) and Federated Learning (FL) for decentralized breast cancer diagnosis in healthcare organizations. This FL system allows institutions to train models locally without sharing patient data, while DP protects against attacks and data leakage. The model achieved an accuracy of 96.1%, comparable to centralized models but with better privacy. However, it relies on a relatively small dataset limited to numeric features and does not fully address challenges like data heterogeneity. Bechar et al. [

28] introduced a framework combining FL and Transfer Learning (TL) for collaborative cancer detection, using large-scale datasets like BreakHis, which contains 7909 histopathological images. This model allows local training while sharing only model parameters, achieving an accuracy of 96.32%. However, it also suffers from limited data heterogeneity and lacks other modalities like MRI and mammography. A hybrid approach in [

29] utilized FL with LightGBM for cancer detection across institutions, incorporating Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) for model interpretation. This framework explored multimodal data from Kaggle, achieving an accuracy of 98.3% with high precision and recall. Despite its strengths, the dataset may not reflect real clinical diversity, necessitating wider testing in diverse federated settings. Additionally, the computational demands of SHAP may limit its application in low-resource clinics.

While federated learning has been increasingly explored in breast cancer imaging, prior studies have largely been confined to binary classification tasks (benign vs. malignant) and to imaging modalities such as histopathology and mammography.

To date, limited research has explored multi-class federated learning for breast cancer classification using ultrasound data. Existing studies have primarily focused on binary classification tasks and the only known attempt at a multi-class federated framework built for Breast Cancer Histopathological Image Classification [

30]. Building on this gap, this study systematically analyzes federated learning approaches for multi-class breast ultrasound classification across multiple institutions, providing a comparative assessment of their performance under realistic data heterogeneity.

4. Experiments and Results

This section presents the experimental design, baseline comparisons and federated learning evaluations performed in this study. All experiments aim to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of federated learning for multi-class breast cancer ultrasound classification across multiple institutions. The experimental design is structured into three phases, each validating a core aspect of applying Federated Learning (FL) to multi-class breast cancer classification.

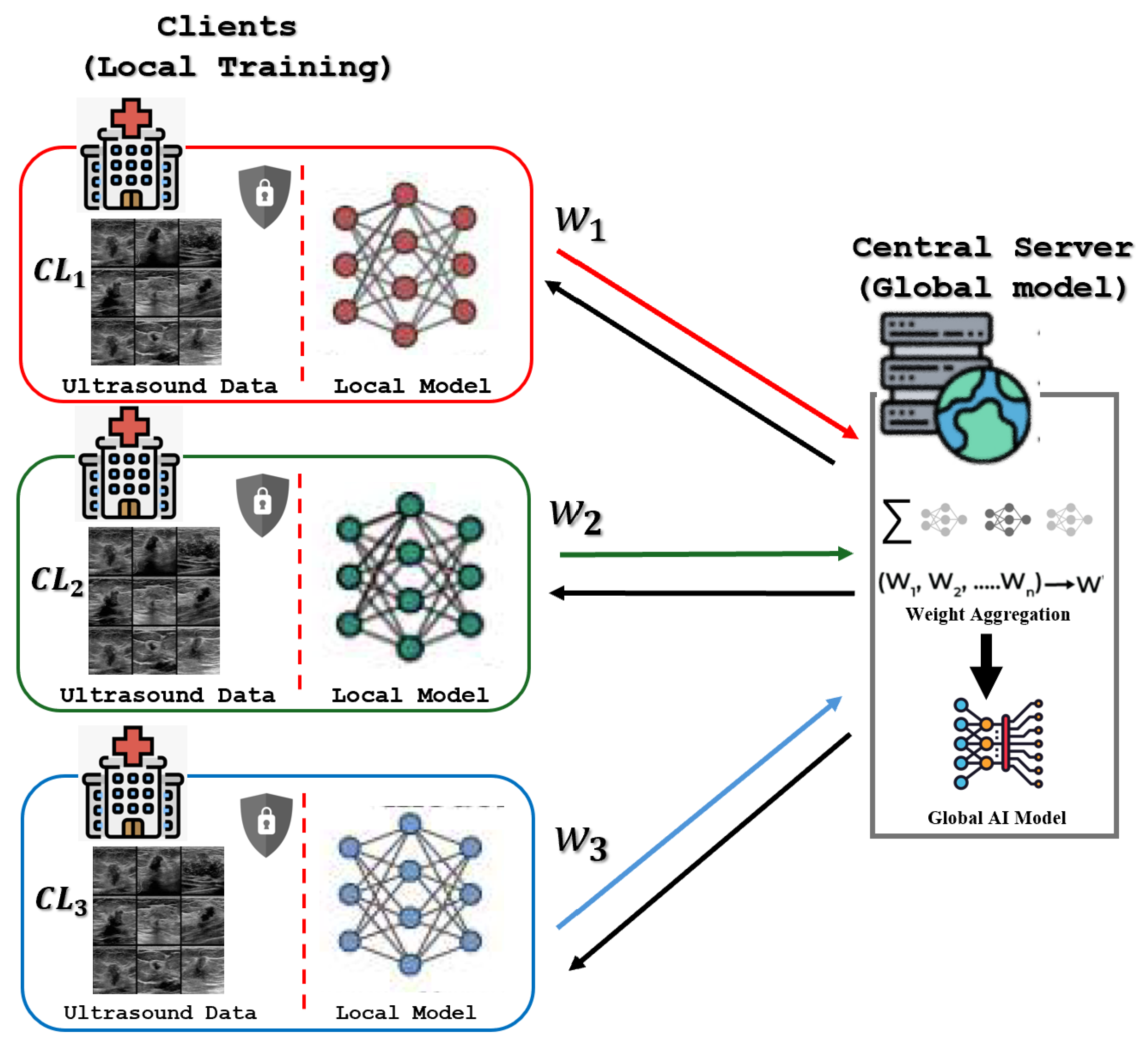

The underlying server–client architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3. This decentralized training consists of a Central Server that coordinates three distinct clients: the Breast Cancer Multimodal Imaging Dataset (BCMID), acquired from Ayadi Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt, the BUSI dataset, also sourced from medical centers in Egypt; and the BUS-UCLM dataset, originating from a university hospital in Spain. This architecture ensures that the sensitive ultrasound images remain strictly localized on each client’s secure device, preserving data privacy. In every communication round, each client performs local training on its proprietary data, generating updated model weights, which are the only parameters transmitted to the Central Server. The server then aggregates these updates through weighted averaging to produce an improved Global AI Model.

4.1. Experimental Settings

The models utilized across all experiments—centralized, local, and federated—were constructed using the Keras API with a TensorFlow backend. All core training parameters remained constant across modalities: models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a fixed learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 32, and a maximum of 20 epochs, subject to early stopping based on validation loss. These specific hyperparameters were chosen based on established values in related literature, providing a robust and widely used baseline. Maintaining a fixed set of parameters was a deliberate choice to ensure a fair and direct comparison between the training paradigms, thereby isolating the performance differences attributable to the learning framework (centralized, local, or federated) rather than to model-specific tuning.

For multi-class classification, the output layer employed the softmax activation function, optimized initially via the categorical cross entropy loss function. To guarantee complete reproducibility, all environments were initialized using a fixed random seed and deterministic behavior was enforced during the TensorFlow configuration. The federated setting was implemented and orchestrated using the open-source Flower framework [

41], which follows a clear server-client architecture: a central server coordinates the training process (handling client selection and model aggregation), while decentralized clients execute local training tasks and transmit model updates back. Centralized and local experiments were conducted using Google Colab environment with a CPU backbone, whereas federated experiments were run locally on an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-10510U CPU @ 1.80 GHz (2.30 GHz) with 16 GB RAM. This client hardware configuration was deliberately chosen to simulate real-world scenarios, particularly in contexts like hospitals, where participating entities typically lack advanced GPU or high-end computational resources.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the performance of the different approaches in classifying breast ultrasound images into normal, benign, and malignant categories, several standard evaluation metrics were employed, namely Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1-Score. These metrics provide complementary insights into model performance, particularly under class imbalance conditions common in medical imaging.

Accuracy measures the overall proportion of correctly classified samples among all predictions and is defined as:

where

C is the number of classes (three in this study), and

,

,

and

represent the true positives, false positives, false negatives and true negative for class

i, respectively. Although accuracy reflects the overall correctness of predictions, it fails to account for class imbalance and may therefore overestimate model performance.

To ensure a fair evaluation across classes, we employ macro averaging, which computes each metric independently for every class and then takes the unweighted mean. The macro precision and macro recall are defined as:

Macro averaging treats all classes equally, ensuring that minority classes (such as malignant) contribute equally to the final metric. In contrast, a weighted average would bias the result toward majority classes (e.g., benign).

The F1-Score, which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balances the trade-off between false positives and false negatives:

The macro F1-Score is then computed as:

The F1-Score is particularly important in medical image classification, where both sensitivity and precision are critical: high recall ensures that most malignant cases are correctly identified, while high precision minimizes false alarms that could lead to unnecessary diagnostic procedures.

4.3. Baseline Performance and Architectural Comparison

The centralized learning experiment, which trains the model on the pooled data of all three clients, provides the primary performance benchmark. In an ideal scenario, this pooled result represents the theoretical upper bound of the achievable accuracy. Although it is generally assumed that training on larger and more diverse datasets leads to improved model generalization, this assumption does not always hold in medical imaging contexts. Previous research has shown that simply aggregating disparate data sources can introduce variability that confuses the model and reduces its ability to distinguish true diagnostic features, leading to unexpected drops [

42,

43].

To identify the most suitable architectures for the federated experiments, we first evaluate SOTA CNN models: DenseNet201, EfficientNetV2M, InceptionNetV3, MobileNet, and ResNet50. Each model is trained and validated independently on the three ultrasound datasets: BUSI, BCMID, and BUS-UCLM. All models are fine-tuned from ImageNet pretrained weights using identical training protocols, input resolution, optimizer settings, and early stopping criteria to ensure fair comparison. The epoch column denotes the final training epoch attained prior to termination by the early stopping criterion. Based on the Macro-Averaged metrics, which provide a balanced assessment across the multi-class breast cancer datasets provided in

Table 2, Resnet50V2 demonstrated the highest accuracy of 68% while both MobileNet and InceptionNetV3 followed with 67%. Although DenseNet201 achieved the highest macro-F1 (69%), accuracy was used as the selection criterion for subsequent FL experiments. Accordingly, MobileNet, InceptionNet and ResNet were chosen for the subsequent federated learning experiments.

It is worth noting that our preliminary experiments also included several Vision Transformer (ViT) architectures [

44] and hybrid CNNs like ConvNeXt [

45]. These models were excluded from the main federated analysis due to an unfavorable trade-off between performance and computational cost as they did not generalize effectively to our ultrasound data. The ViT models, for instance, yielded centralized accuracies in the 64–71% range, offering only marginal improvement over our selected CNNs (up to 70.6% for the best ViT, compared to 68% for ResNet50V2), but required a substantially larger parameter count (up to 305.5M versus 3.8–53.81M for the CNNs). Furthermore, the ConvNeXt models showed significantly lower performance, achieving only 61.0% accuracy (ConvNeXt-Base) in the centralized setting. This large gap between computational demand and classification performance highlights that the significant computational overhead of these architectures was deemed impractical for our target of resource-constrained clinical deployment scenarios, thus justifying our focus on CNN-based deep learning networks.

4.4. Two-Client Federation: Heterogeneity and Architectural Robustness

While the Centralized result provides a performance benchmark, the independent Local Learning experiments, where models are trained exclusively on their respective institutional datasets (BUSI, BCMID, or BUS-UCLM), establish the minimum expected performance. These results reflect how each model performs when trained in complete isolation without external data exposure. The main goal of Federated Learning is to successfully bridge the performance gap between these two extremes, Centralized and Local, aiming to achieve performance metrics that significantly surpass the poor generalization of the local model while approaching or exceeding the centralized baseline across the various client test sets.

The initial centralized baseline is used to select top 3 target architectures by assessing their highest achievable accuracy, as shown in the previous section. Next, the Independent Local Baselines for the selected architectures are executed on each client’s isolated data.

This experiment compares the test performance of centralized, local, and federated learning under identical experimental conditions. The results are reported in the remaining test sets for each client to ensure fairness and reproducibility. We implement and compare two popular FL algorithms: FedAvg and FedProx. FedAvg represents the standard baseline aggregation method, while FedProx introduces a proximal regularization term to mitigate the effects of data heterogeneity. Both algorithms are evaluated using the three selected architectures, MobileNet ResNet50V2, and InceptionNetV3 in all three possible heterogeneous two-client pairings (

,

, and

). In this two-client federation setup, the global model is updated using the weighted aggregation in Equation (

1), while each client’s local objective can include the proximal term from Equation (

2) to mitigate the effects of non-IID data.

The comparative results are illustrated in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 detailing the metrics per-client on the respective test sets. The metrics presented include accuracy, macro-precision, macro-recall, and macro-F1 score. It is important to note that the reported centralized learning setup is defined per combination of clients; for each pair of institutions, a centralized model is trained on the pooled data of the two participating datasets and individually evaluated on each client’s respective test set.

The BCMID + BUS-UCLM federation represents the most heterogeneous data scenario, with substantial label and quantity skew between clients. Both architectures experienced moderate performance degradation compared to the other two-client settings. In MobileNet and ResNet architectures, FedAvg achieved marginally higher performance on the BCMID client in isolation. This can be attributed to the fact that BCMID is a bigger dataset compared to BUS-UCLM, which allows FedAvg’s direct averaging mechanism to converge more effectively when one client dominates the data distribution.

Overall, the results demonstrate that federated learning generally outperformed independent Local models across all two-client combinations, confirming the effectiveness of federated aggregation in mitigating data isolation. In most settings, FedProx achieved slightly higher stability and balanced macro-averaged metrics, particularly under stronger heterogeneity, such as the case in pairing BUSI and BCMID). For both architectures, MobileNet, ResNet50V2 and InceptionNetV3, federated models substantially matched or exceeded the performance of traditional learning while preserving decentralized data privacy.

4.5. Scalability and Generalization with Multi-Client Federation

This experiment evaluates the scalability and generalization capability of the federated learning framework. In this setting, all three clients, BUSI, BCMID, and BUS-UCLM, participate in a collaborative training process. This configuration simulates a more complex multi-institutional collaboration where data distributions, imaging protocols, and patient demographics may vary substantially across sites.

Table 6 summarizes the results for all selected architectures (MobileNet, ResNet50V2, and InceptionNetV3), reporting classification accuracy and macro-F1 scores evaluated on each client’s test set.

As shown, FedAvg exhibited a marked degradation in performance, with the average accuracy dropping to 67.6% and macro-F1 to 57.33%, even below the Local baseline (71.0%, 66%). This decline reflects the sensitivity of FedAvg to severe inter-client heterogeneity. In contrast, FedProx improved the global model’s stability, achieving 73.2% accuracy surpassing all baselines across most clients for MobileNet. BUSI and BUS-UCLM, the datasets with smaller class imbalance and more consistent imaging conditions, benefited the most from FedProx, while BCMID showed a moderate gain. For the ResNet50 architecture, a similar yet less favorable pattern was observed compared to MobileNet. Although FedProx mitigated the severe degradation seen with FedAvg, its performance remained slightly below the Local baseline, achieving an average accuracy of 69.1% and macro-F1 of (63%). For the InceptionNetV3 model, federated performance remained comparable to the centralized benchmark, with FedProx achieving 66.6% accuracy and 59.7% macro-F1, reflecting a modest imporvement ovr FedAvg.

As presented in

Table 6, the three-client federation combining BUSI, BCMID, and BUS-UCLM achieved consistent performance improvements over both local and centralized training across architectures. For the MobileNet model, FedProx reached an average accuracy of 73.31% and a macro-F1 of 67.31%, outperforming the average Local (71.00%, 66.33%) and Centralized (72.09%, 55.20%) settings. A similar pattern was observed with ResNet50V2, where FedProx achieved 69.07% average accuracy and a macro-F1 of 63.16%, achieving comparable accuracy to centralized training while surpassing it in F1-score. However, FedAvg retained a slight advantage, specifically on the BCMID client, for this architecture. These results confirm that incorporating data from all three institutions enhanced the robustness and generalization of the global model, despite increased heterogeneity across clients.

To validate the statistical reliability of the best-performing configuration, MobileNet with FedProx, we conducted the DeLong test to compare the AUC-ROC curves across training paradigms. The analysis yields two critical findings that substantiate the efficacy of the proposed FL framework. First, the comparison between Centralized and FedProx showed no statistically significant difference across any client (all

), statistically indicating that our privacy-preserving FedProx model achieves diagnostic performance comparable to that of centralized data pooling in this experimental setting. Second, while Centralized training proved statistically superior to Local training for the BCMID (

) and BUSI (

) datasets, the improvement of FedProx over Local training approached significance (

for BCMID). Although strict statistical significance (

) was marginally missed, these

p-values—combined with the consistent accuracy gains reported in

Table 6 indicate a strong positive trend in generalizability and clinical robustness.

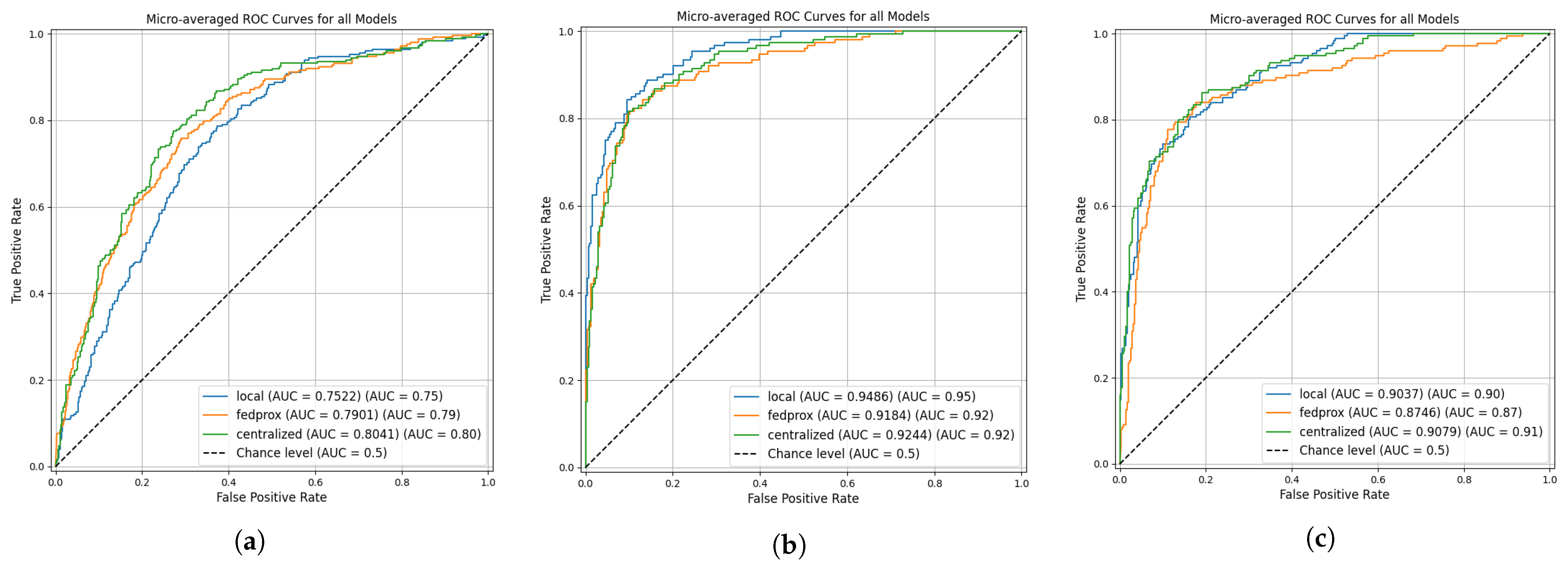

Across all datasets, the ROC analysis demonstrated in

Figure 4 shows that the comparable discrimination performance between the Federated Proximal (FedProx) and Centralized models, while the Local models showed more variability. For the BCMID dataset, the Centralized model achieved the highest AUC (0.804), followed closely by FedProx (0.790), with Local training performing notably lower (0.752). In the BUSI dataset, the Local model unexpectedly achieved the highest AUC (0.949), while Centralized and FedProx models yielded similar performance (0.924 and 0.918, respectively). For the BUS-UCLM dataset, the AUC values of Centralized (0.908) and Local (0.904) were nearly identical, with FedProx slightly lower at 0.874. These trends were supported by DeLong’s statistical tests: significant differences appeared only in the Centralized vs. Local comparison for BCMID and BUSI, whereas Local vs. FedProx and Centralized vs. FedProx showed no statistically significant differences across all datasets. Overall, FedProx consistently provided performance that was statistically indistinguishable from Centralized training while maintaining stability across heterogeneous client distributions.

4.6. Ablation Study: Adaptive Loss Function for Heterogeneity Robustness

The comparative analysis shows that inter-client heterogeneity in the three-client federation poses a significant challenge, limiting the performance gains of standard federated learning algorithms, even the FedProx approach. To address this, we propose a targeted contribution focused on client-level optimization. Instead of altering the server-side aggregation, we investigate whether adapting the client’s local training objective can better accommodate its specific data distribution. Based on its superior average performance in the three-client scenario as highlighted in

Table 6, the MobileNet architecture combined with the FedProx algorithm was selected as the base for this investigation. We investigate the Tversky loss, a function commonly used in the medical image analysis domain, particularly for segmentation tasks with highly imbalanced classes [

46]. The Tversky Index (TI) is a generalized metric of both the Dice coefficient and Jaccard index, defined as

The key parameter for the Tversky loss are the

and

parameters. These explicitly control the penalties for False Positives (FP) and False Negatives (FN), respectively. In the context of medical diagnostics, a False Negative (missing a malignant tumor) is often far more detrimental than a False Positive. To embed this clinical priority into the model’s objective, one can set

, thereby forcing the model to learn features that minimize the risk of missing positive cases. In our proposed FL setting, we applied an ablation study consisting of 3 experiments, as summarized in

Table 7. The baseline is the standard Categorical Cross-Entropy (CCE) loss function. The second experiment replaces CCE with a standard Tversky loss using commonly-cited fixed parameters (

). The third employs a combined Loss with 50% Fixed Tversky and 50% CCE to test a blended, more stable approach.

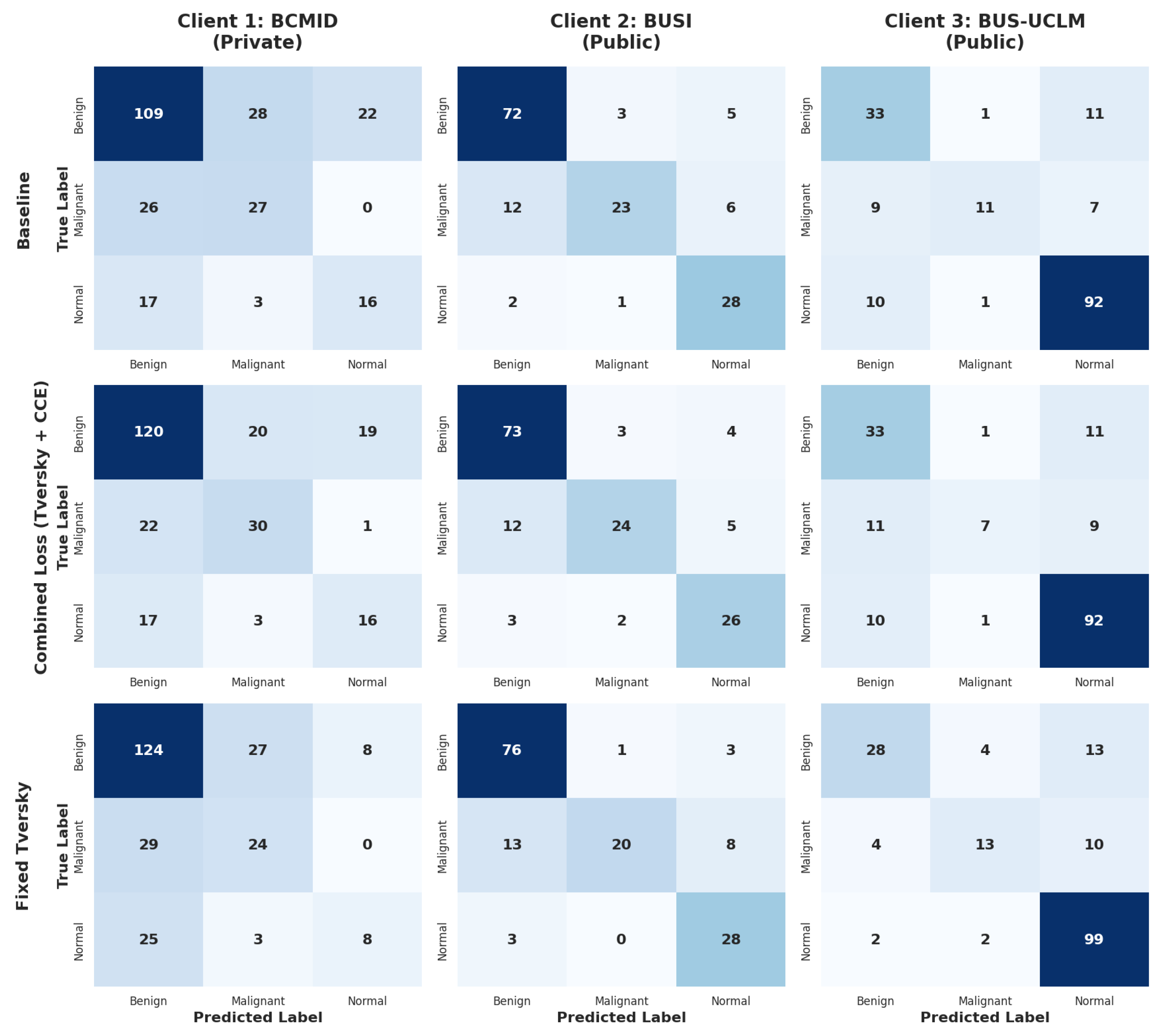

The primary benefit of introducing the adaptive loss functions is clearly demonstrated by their impact on the most challenging and imbalanced dataset, BCMID. The Fixed Tversky Loss configuration yields a dramatic improvement for BCMID, boosting its accuracy from 61.29% (Baseline) to 66.94% and its Macro F1-score from 54 to 58.84. However, this optimization comes with a trade-off. The same Loss causes a performance drop on the BUS-UCLM dataset, with Macro F1 declining from baseline. In contrast, the combined Loss finds a different balance: while it doesn’t improve BCMID as dramatically as the Tversky loss (reaching 62.90%), it successfully elevates the performance on the BUS-UCLM dataset, maintaining higher stability across the public benchmark. This suggests that while the Tversky component penalizes false negatives, the addition of Cross-Entropy provides necessary gradient stability, allowing the model to converge to a higher sensitivity for minority classes, as visualized in the confusion matrices in

Figure 5.

5. Discussion

In our experiments, the combined multi-institutional centralized learning did not consistently outperform each institution’s independent learning despite having access to aggregated data. Although centralized models occasionally achieved slightly higher average accuracy, their performance gains were inconsistent. This observation reflects a known challenge in multi-institutional aggregation of naive data pooling across heterogeneous medical sources. In medical imaging, this heterogeneity often appears as Domain Shift, arising from differences in scanner manufacturers, imaging protocols, and patient populations across hospitals [

47]. When such disparate data are simply pooled, this leads to negative transfer, where the unique, high-quality features learned from one institution’s consistent protocol are effectively treated as noise by the training process, resulting in a generalized model that performs similarly to local models. Similar observations have been reported in the previous literature, where the incorporation of data from multiple institutions sometimes even degraded the performance of the model [

42,

43,

48].

The comparative analysis confirms that the FL approach remains effective in mitigating the negative impact of data heterogeneity specifically within the domain of multi-institutional ultrasound classification. In particular, the observed performance gains of both FedAvg and FedProx over independent Local baselines highlight FL’s capacity to transfer complementary diagnostic knowledge across clients without compromising data privacy. For example, in the BUSI + BCMID federation (

Table 3), FedProx on MobileNet improved the average Macro F1-Score from 65% in the Local setting to 68%, while accuracy rose from 67.9% to 74.5%. A similar trend was observed with InceptionNetV3, where FedProx improved average accuracy from 61.0% to 67.6% and Macro F1 from 57% to 62%. Similarly, in the BUSI + BUS-UCLM combination (

Table 4), FedAvg on MobileNet achieved an average accuracy of 83.6% compared to 78.5% locally, with a corresponding increase in Macro F1-Score from 74% to 79%. Even in the most heterogeneous pairing (BCMID + BUS-UCLM,

Table 5), FedProx on MobileNet improved accuracy from 66.3% to 67.7%. InceptionNetV3 followed the same modest improvement pattern, with accuracy increasing from 60.0% to 61.2%, further confirming the limited but positive transfer effect. Consistent with prior research, FedProx exhibited greater stability under statistically heterogeneous (non-IID) conditions. In the BUSI + BCMID federation, FedProx produced more consistent macro-F1 scores across clients, indicating improved robustness to imbalance even when average performance differences were marginal. It is worth noting, however, that FedAvg outperformed FedProx in certain configurations, particularly where inter-client heterogeneity was moderate. For instance, in the BUSI + BUS-UCLM setup using the MobileNet architecture (

Table 4), FedAvg achieved a slightly higher average accuracy than FedProx. InceptionNetV3 also showed near-equivalent performance between FedAvg 73.5% and FedProx 74.1%, supporting the notion that under moderate heterogeneity, both aggregation methods yield comparable outcomes.This marginal advantage may be attributed to the simpler averaging mechanism of FedAvg being more effective when client gradients are already well-aligned due to similar data distributions. Some theoretical and empirical analysis suggest that under mild non-IID settings, FedAvg’s performance can be comparable to that of FedProx, whereas FedProx tends to be more advantageous under stronger heterogeneity [

40].

The results highlight important characteristics of each training strategy under varying data conditions. Centralized training generally delivered the strongest or near-strongest ROC curves, reflecting its advantage when all training data are pooled; however, this approach is often infeasible due to privacy and data-sharing restrictions. Local training, while effective on the BUSI dataset, exhibited substantial variability, underperforming markedly on BCMID and showing only moderate performance on BUS-UCLM. This instability likely reflects sensitivity to limited or non-representative client data, making local-only models unreliable in non-IID settings. In contrast, FedProx consistently achieved AUC values close to those of the Centralized model across all datasets, without any statistically significant performance drop. This suggests that FedProx effectively mitigates heterogeneity-induced client drift while preserving discriminative performance. Importantly, although FedProx did not significantly outperform either Local or Centralized models, its stability and robustness across datasets make it the most dependable choice when data cannot be centralized and when client data distributions differ. These findings emphasize FedProx’s suitability for real-world federated learning environments that must balance privacy constraints with model performance.

To further elaborate on the diagnostic significance of this contrast, the utility of FedProx is mainly in its ability to manage client drift, the fundamental convergence failure in non-IID FL. By introducing its proximal regularization term from Equation (

2), FedProx restrains the local model from diverging too far from the global model during client training. In practice, when a client like BCMID possesses a severe majority class imbalance (64% benign), standard FedAvg allows the local model to over-optimize heavily toward benign features, causing the model updates to conflict with the global model, resulting in the drastic performance drop seen in the three-client federation Macro F1-Score of 57.33% for MobileNet. In contrast, FedProx’s regularization counters this tendency, transferring knowledge in a more stabilized manner. This directly results in the preservation of diagnostic performance for minority, clinically critical classes, Normal and Malignant, leading to the superior Macro F1-Score of 66.42%. Furthermore, this principle is substantiated by our Ablation Study in

Section 4.6, where the introduction of the Tversky Loss, a local, client-side regularizer, achieved similar stability and boosted the global Macro F1-Score for the most imbalanced client, BCMID. This shows that model stabilization, whether through server-side aggregation (FedProx) or client-side loss function design (Tversky), is an essential solution for maintaining reliable multi-class diagnostic accuracy under high data heterogeneity.

The client-level performance gains from federated learning were not uniformly distributed across datasets, but instead reflected each datasets’ internal class balance and size. In the BUSI + BCMID federation running on MobileNet, the BCMID client—although the largest in sample size—benefited the most due to its strong benign-class dominance, with accuracy improving from 55.6% to 68.0% and macro-F1 from 50% to 57% under FedProx, while BUSI’s already robust performance remained stable (80.3% to 81.0%). Similarly, in the BCMID + BUS-UCLM federation, the BCMID client again exhibited noticeable improvement—its accuracy increasing from 55.6% (Local) to 64.9% under FedAvg and 58.9% under FedProx, with corresponding macro-F1 scores rising from 50% to (57%) and 55%, respectively. However, this came at the cost of severe degradation on the BUSI client (63.15%), indicating client drift. FedProx balanced this effectively. This benefit pattern highlights that FL disproportionately aids clients constrained by data imbalance rather than size, while well-balanced sites contribute stability to the global model. This highlights how FL can transfer complementary diagnostic representations from more balanced datasets to highly skewed ones. In the BUSI + BUS-UCLM federation, both institutions achieved consistent gains, although the relative improvement was more evident for BUS-UCLM, reflecting FL’s ability to enhance smaller and slightly imbalanced datasets. Our results also align with recent studies that emphasize that federated strategies outperform isolated local training in medical imaging domains characterized by strong domain shifts [

21]. However, the reduced gains in the BCMID + BUS-UCLM pairing suggest that extreme heterogeneity still poses convergence challenges, a limitation also identified in [

13,

15], who emphasized that non-IID distributions remain a primary obstacle to the clinical implementation of FL.

In federated learning research, it is commonly observed that increasing the number of participating clients can lead to a reduction in global model performance; mainly because the aggregation process must accommodate a wider range of data characteristics [

15,

49]. The results in

Table 6 demonstrate that expanding the federation to include BUSI, BCMID, and BUS-UCLM improves the robustness and diagnostic balance of the global model compared to both local and centralized approaches. The MobileNet configuration achieved the strongest results with average accuracy 73.31%). The observed decline in FedAvg reflects the algorithm’s sensitivity to severe statistical heterogeneity between clients, as the participating datasets (BUSI, BCMID, and BUS-UCLM) differ in both class distribution and sample quantity. In such highly non-IID conditions, FedAvg’s straightforward parameter averaging leads to conflicting gradient updates, causing the global model to oscillate between divergent local optima rather than converging to a stable state. However, increasing the number of clients also introduces notable challenges. As more institutions participate, variations in data distributions, annotation styles, and acquisition devices amplify heterogeneity. A per-dataset inspection reveals that the impact of expanding from two-client to three-client federation is not uniform across sites. For MobileNet (FedProx), BUSI’s peak two-client performance occurred in the BUSI + BUS-UCLM pairing (accuracy = 83.55%,

Table 4), but this fell to 80.92% in the three-client setup, representing a drop of 2.63%. BCMID exhibits the strongest two-client result when paired with BUSI with an accuracy of ≈68.00%, as shown in

Table 3, yet its accuracy in the three-client federation is 61.29%, representing a decline of 6.85% relative to that best two-client pairing; however, BCMID does improve relative to its performance in the BCMID + BUS-UCLM pairing (58.87% in

Table 5), gaining around 2.0% in the three-client case.

Analyzing the performance across federation scenarios reveals a consistent pattern where the in-house clinical dataset (BCMID) benefits greatly from collaboration with public benchmarks. As illustrated in

Figure 6, in the two-client settings (

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5), the pairing of BUSI and BCMID yielded the most dramatic improvement, with the private client gaining 12.51% in accuracy over local training, effectively illustrating the benefits of FL knowledge transfer. This trend persists in the three-client federation (

Table 6), where the private client achieved a 5.65% gain compared to modest improvements for the public clients. Most notably, the proposed Combined Loss framework (

Section 4.6) maximized this advantage: while the public datasets BUSI and BUS-UCLM saw limited improvements, the in-house BCMID dataset achieved a substantial

boost. This confirms and demonstrates how resource-constrained clinical institutions can leverage high-quality external representations to improve local diagnostic accuracy without sharing sensitive data. These results indicate that the proposed FL framework facilitates significant improvements for resource-constrained clinical datasets while maintaining the performance standards of established public benchmarks.

Overall, the present findings show that federated learning provides a potential alternative offering privacy preservation, by not requiring direct data sharing, and scalable multi-institutional learning. The uniform behavior observed across our selected models indicates that this performance pattern could reasonably be expected to hold for other neural networks. The comparative results highlight that federated learning best benefits the clients with more limited or skewed data, in line with previous observations [

18,

22], who reported similar cross-institutional gains for underrepresented datasets in mammography and pathology classification.

Limitations

While this study demonstrates the architectural robustness and heterogeneity mitigation capabilities of Federated Learning (FL) for multi-class breast cancer classification, it is important to acknowledge several limitations that define the scope of the current work and suggest directions for future research. A primary advantage of FL is its promise of enhanced data privacy; however, this study focuses solely on the performance and heterogeneity-handling aspects of FL protocols and does not incorporate advanced cryptographic or differential privacy mechanisms. In other words, no privacy was injected beyond the distributed nature of the training process itself. Moreover, the transition from our simulated environment to a live clinical deployment within a routine hospital environment presents practical logistical, computational, and human-centric challenges that this study did not address. A key consideration is the complexity of deploying and maintaining the federated orchestration system (such as the Flower framework). While local computation is efficient, the iterative communication rounds central to FL introduce significant overhead due to network latency. Our analysis did not evaluate mitigation strategies, such as scheduling communication during off-peak hours or optimizing the number of aggregation rounds to balance performance and time costs. Additionally, the operational robustness of a real-world system was assumed to be ideal, yet varying levels of digital infrastructure readiness across institutions could hinder deployment. Finally, the successful adoption of such models relies not only on technical metrics but also on overcoming clinical resistance arising from skepticism or lack of trust in AI-driven decision support systems. Another limitation is conducting the analysis using only three distinct public datasets (BUSI, BCMID, and BUS−UCLM), while it allowed for testing of all two-client combinations and a comprehensive three-client setup. However, to better validate the true scalability of the FL framework in a real-world setting, a significantly larger number of clients (e.g., 5 to 10 hospitals) should be involved. However, this study was constrained by the limited availability of high-quality, publicly accessible ultrasound datasets that offer multi-class annotations (Normal, Benign, Malignant). Consequently, while the current experimental design simulates heterogeneity, it does not fully confirm generalizability to entirely new patient populations or diverse imaging protocols. Future validation on a completely independent, unseen dataset from a distinct clinical site is required to verify the model’s robustness in scenarios outside the training federation.

A methodological limitation of our study is the absence of repeated experimental runs to calculate inter-run variance. This constraint was imposed by the significant computational and time resources required to execute full, end-to-end federated experiments across all centralized, local and federation scenarios. Consequently, all reported results are derived from a single, deterministically seeded execution to maximize reproducibility and ensure stable training dynamics, thereby minimizing run-to-run variability across all comparisons.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study presented a comparative analysis of federated learning (FL) approaches for multi-class breast cancer classification across three categories (benign, malignant, and normal). This study contributes to addressing the current gap in applying federated learning to multi-class breast ultrasound classification, an area where prior have been limited to binary tasks. Using three datasets (BUSI, BUS-UCLM and BCMID), two public and one in-house, we evaluated multiple CNN-based architectures under three training paradigms: centralized, independent/local, and federated learning. The results demonstrate that FL provides a promising direction for the development of collaborative and privacy-preserving models in medical imaging, effectively addressing the data-sharing restrictions that often hinder clinical AI research.

Across experiments, FL showed robust performance against both architectural and statistical heterogeneity. In particular, FedProx consistently provided greater stability and higher average performance compared to FedAvg, especially in the three-client setting where data non-IID characteristics were increased. Furthermore, FL outperformed centralized training in nearly all scenarios, proving that direct data pooling can cause domain shift and reduce generalization in multi-institutional tradiotonal learning context. Ultimately, this framework translates into actionable clinical support by enabling automated risk stratification and triage to prioritize high-risk patients and optimize diagnostic workflows while maintaining cross-institutional privacy.

Future work will focus on integrating personalization mechanisms at the client level to better adapt global models to local data distributions. Furthermore, a comprehensive hyperparameter optimization and sensitivity analysis could be conducted to maximize the absolute diagnostic performance of the models and assess the robustness of our comparative findings under different training configurations. To further strengthen privacy guarantees, future research should also incorporate and rigorously validate robust differential privacy mechanisms within the federated learning workflow. Additionally, exploring more advanced architectures, such as Vision Transformers and hybrid CNN–transformer models, may further enhance diagnostic accuracy. Investigating harmonization strategies for imaging protocols across institutions could help reduce domain shift and improve cross-site model consistency. Finally, expanding the study to include a larger number of institutions and datasets will help re-validate the scalability and generalizability of federated learning in real-world clinical environments.