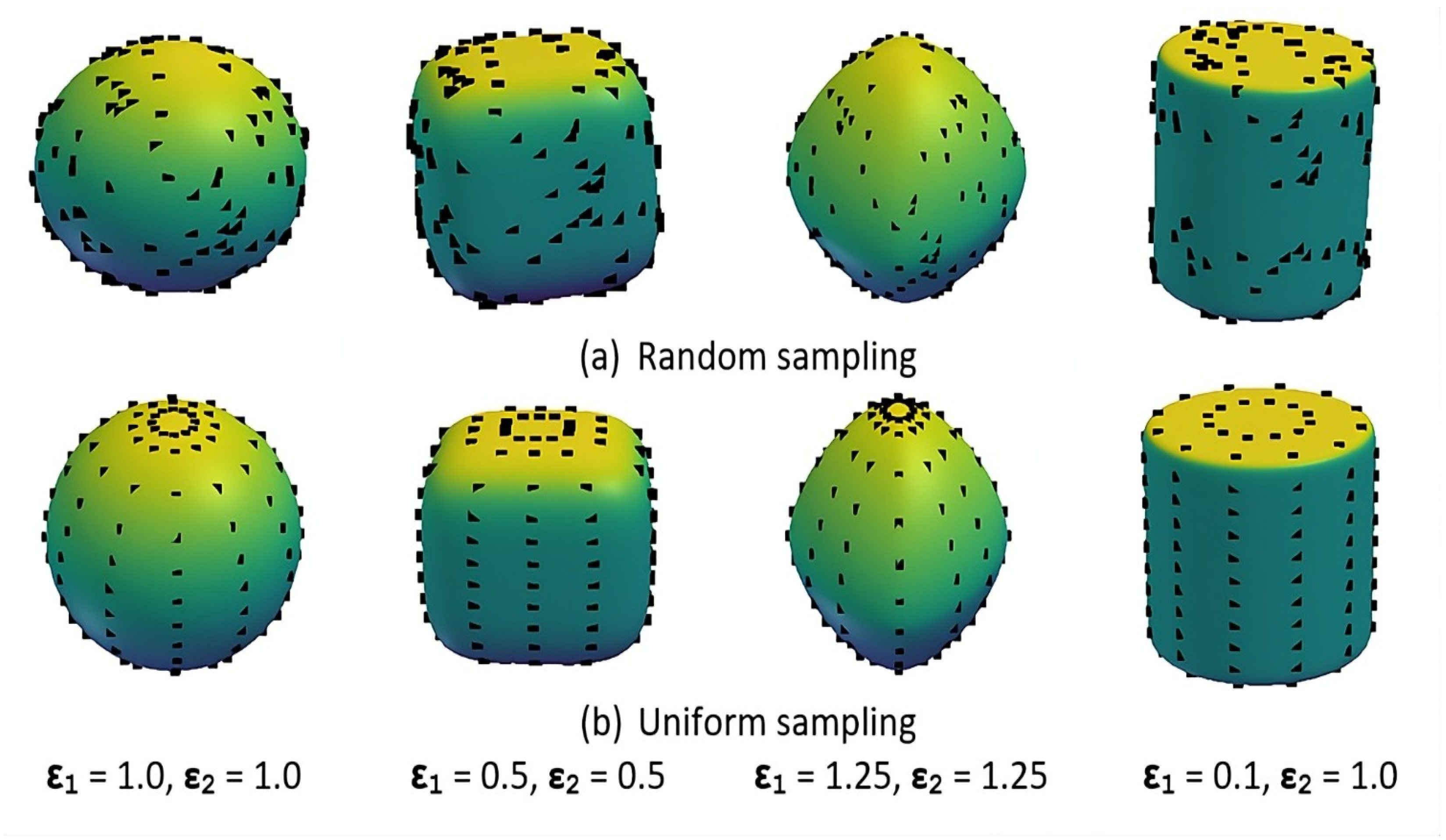

For both strategies, we uniformly generate 200 surface points per primitive and compare them against a ground truth point cloud of 1000 points per object. The evaluation focuses on the effect of sampling uniformity on shape approximation accuracy, measured using our Structural Accuracy and Primitive Accuracy metrics, as well as the stability of training convergence.

7.1. Evaluation Metrics

Traditional reconstruction measures such as the Chamfer Distance (CD) and Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) quantify point-level similarity between reconstructed and ground-truth shapes. However, these global distance metrics overlook structural and semantic relationships among primitives, offering limited insight into how well a model captures part-level geometry or inter-primitive consistency. Consequently, relying solely on these measures provides an incomplete understanding of primitive-based reconstruction performance.

To address this limitation, we introduce a novel evaluation framework that extends beyond surface-based metrics toward structure-aware assessment. Building upon our prior work [

6], this framework incorporates three new complementary metrics—

Primitive Accuracy (PA),

Structural Accuracy (SA), and

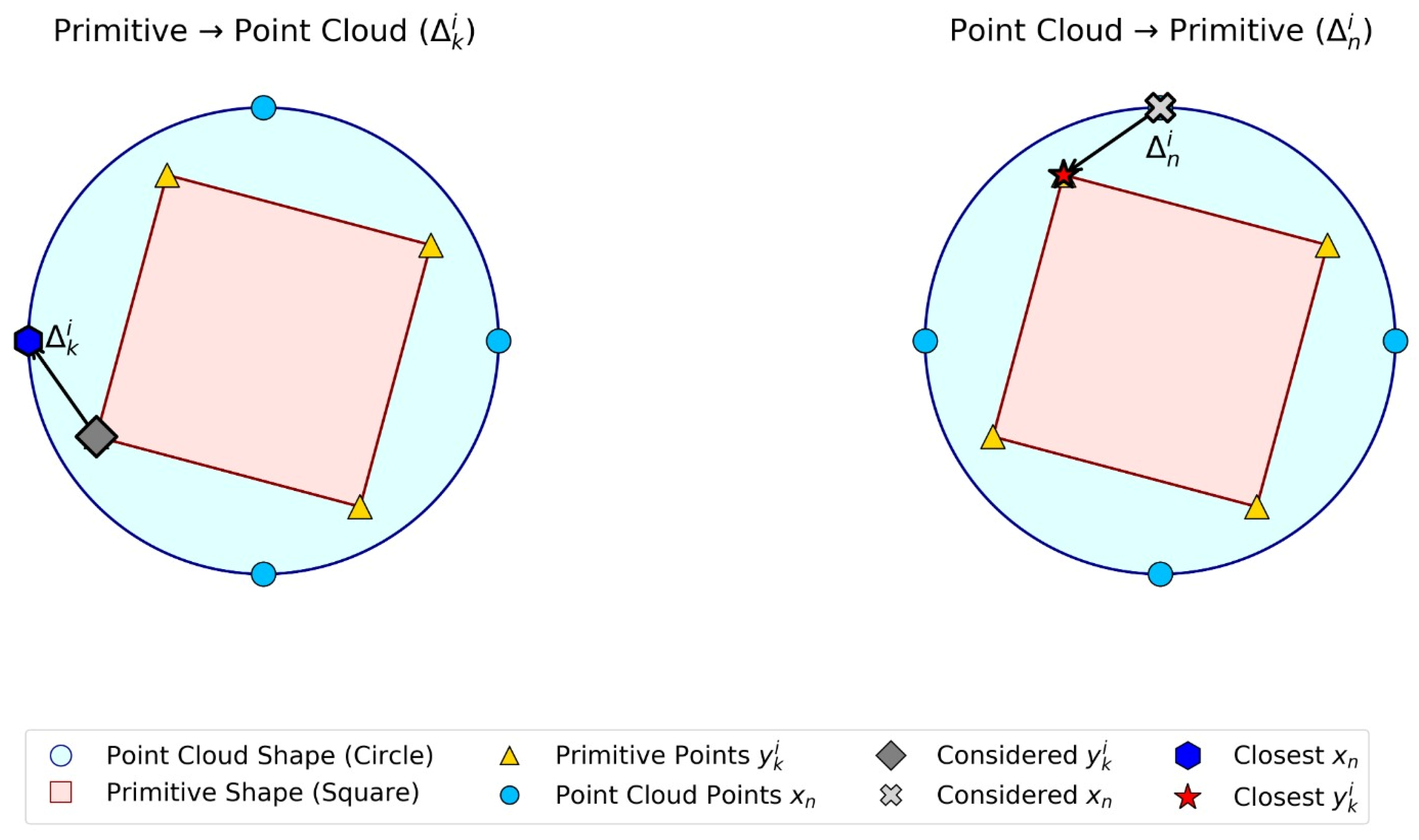

Overlapping Percentage (OP)—that collectively measure reconstruction quality from multiple perspectives. Primitive Accuracy directly quantifies the correspondence between predicted and ground-truth primitives, enabling the first objective evaluation of part-level geometric correctness. Structural Accuracy evaluates the global alignment and fidelity of the composed shape, while Overlapping Percentage measures redundancy and spatial coherence between adjacent primitives.

This design represents a conceptual advancement in evaluating interpretable 3D reconstruction. By shifting from point-based distances to primitive- and structure-aware metrics, our approach enables fairer, more interpretable, and reproducible comparisons between primitive-based models. It provides an essential foundation for future benchmarking efforts, promoting transparency and consistency in assessing primitive-based shape decomposition.

As discussed above, unlike Chamfer Distance or Earth Mover’s Distance, which measure global surface proximity, the proposed PA, SA, and OP metrics operate at the primitive level, enabling structural interpretability. They explicitly quantify how individual primitives contribute to both local geometric fidelity and global segmentation consistency, offering insight unavailable from point-based reconstruction errors.

7.1.1. Structural Accuracy

Structural Accuracy quantifies how well the output primitives capture the structure of the input point cloud. Specifically, it measures the number of input points that are effectively represented by the predicted primitives, with higher values indicating better shape coverage.

Let

N denote the total number of input points, and let

represent the subset of points from the input that are covered by the generated primitives. Structural Accuracy (SA) is then defined as:

A higher Structural Accuracy value reflects a better correspondence between the predicted primitives and the true structure of the object, indicating the model’s effectiveness in representing the overall input geometry.

7.1.2. Primitive Accuracy

This metric evaluates how well each primitive aligns with the input point cloud while maintaining geometric consistency and meaningful segmentation. It measures the degree to which a primitive conforms to the shape and spatial distribution of its corresponding region in the input data.

In addition to alignment, the metric accounts for over spanning, which occurs when a primitive extends beyond its intended region and covers areas that do not belong to the target structure. A higher Primitive Accuracy score reflects both tighter geometric alignment and reduced over spanning, indicating that the predicted primitives effectively capture distinct and meaningful shape components.

The computation of Primitive Accuracy proceeds in five steps, as detailed below.

Step 1: Compute Radial Distances for Input Points To quantify geometric alignment, we compute the radial distance of each input point within the -plane. This projection-based measure simplifies the analysis by capturing the lateral spread of the shape while reducing sensitivity to vertical variations along the z-axis.

This formulation assumes a consistent orientation of the input object, where the -plane aligns with the object’s primary structural plane. Under this assumption, measuring radial distance from the origin is reasonable, as the origin serves as a reference point representing the object’s center. In more general cases, the metric can be adapted to each primitive’s local coordinate frame or center to accommodate arbitrary orientations.

Step 2: Filter Radial Distances Using Inside Mask The inside mask is defined as a binary indicator function that specifies whether each input point lies within the volume of a given primitive. This mask is used to filter the computed radial distances, ensuring that only points enclosed by the primitive contribute to the subsequent calculations.

Step 3: Estimate Mean Radial Distance (MRD) The mean radial distance (MRD) for each primitive is defined as the average two-dimensional radial distance of the input points enclosed by that primitive. The MRD serves as an indicator of the spatial extent of the region of the input point cloud represented by the primitive.

A significantly high MRD value may indicate a mismatch between the geometry of the input region and the superquadric form used to approximate it. For example, when the input resembles a toroidal shape (i.e., a structure with a central void), the model may assign a large MRD value to a primitive attempting to fit the outer ring. Because superquadrics cannot represent hollow structures like a torus, this leads to inaccurate modeling. Therefore, the MRD can serve as a diagnostic indicator for detecting such geometric mismatches and potential failure cases.

Step 4: Identify Geometric Mismatches Using Mean Radial Distance (MRD) Because our model is constrained to predict superquadrics—solid, closed surfaces—it cannot represent complex topologies such as toroidal shapes or objects containing substantial internal voids. To address this limitation without altering the model architecture, we introduce a diagnostic method that identifies when a predicted primitive is likely mismatched with the underlying input geometry. Specifically, the MRD computed from input points assigned to each primitive serves as a heuristic indicator of geometric mismatch. A high MRD value indicates that the primitive attempts to span an extended or disconnected region—behavior that is atypical for valid superquadric fitting. A mismatch detection function is defined to compare the MRD value against a predefined threshold. The proportion of primitives exceeding this threshold is then computed across the batch. This diagnostic is not used during training; instead, it serves as a post hoc evaluation tool to reveal limitations in the model’s representational capacity and to identify cases where the predicted output fails to accurately capture the input geometry.

In practice, an MRD threshold of 0.05 (normalized by object scale) is used, which empirically separates valid from mismatched primitives across object categories.

Threshold justification. The MRD threshold of 0.05 was determined empirically through validation across multiple ShapeNet categories. Intuitively, this value distinguishes between standard superquadrics and shapes containing internal voids or holes, such as toroidal geometries. In such cases, the MRD measures the mean radial distance between the primitive center and its surface points. For solid shapes, this distance remains close to zero, whereas for toroidal or hollow structures, it becomes significantly higher. Hence, primitives with MRD values above 0.05 reliably indicate topological mismatches.

Step 5: Calculate Primitive Accuracy The objective of this step is to compute a metric that quantifies how accurately each predicted primitive represents the input point cloud, capturing both geometric alignment and structural reliability.

Primitive Accuracy is defined as a weighted combination of two complementary components:

Fit quality—the average geometric fit score of each primitive relative to its associated region in the input point cloud. Higher values indicate closer alignment, whereas overspanning leads to lower scores.

Corrected Precision—the proportion of predicted primitives that are valid fits, i.e., not identified as mismatched shapes (such as those attempting to model toroidal or hollow structures). This value is computed using the mismatch detection method described in Step 4, where primitives with excessively high mean radial distance (MRD) values are flagged as invalid.

A weighting factor is applied to balance geometric accuracy and structural correctness between the two terms.

The final Primitive Accuracy score is computed as a weighted sum of the fit quality and corrected precision terms, jointly reflecting geometric alignment and topological validity. By integrating these two components, Primitive Accuracy provides a comprehensive measure of each primitive’s performance in both surface fitting and structural interpretation. The computation procedure for Primitive Accuracy is summarized in Algorithm 1.

The computation procedure for Primitive Accuracy is summarized in Algorithm 1. The Primitive Accuracy metric jointly captures geometric alignment () and structural validity (), penalizing primitives that overspan or fail to represent distinct parts.

7.1.3. Overlapping Percentage

In this paper, we introduce the Overlapping Percentage as a new metric to quantify the degree of spatial overlap between primitives during segmentation. Overlap occurs when points are simultaneously assigned to multiple primitives, indicating regions where segmentation boundaries are ambiguous or poorly defined. This metric is particularly useful for evaluating segmentation quality, since a high overlap value typically indicates low boundary precision and poor part separation.

The sensitivity of this metric may also depend on the primitive representation—such as pixel-wise masks, bounding boxes, or higher-level feature encodings—which affects how overlap is detected and interpreted. For instance, fine-grained representations such as masks can highlight subtle overlaps, whereas coarser representations such as bounding boxes may obscure them.

| Algorithm 1 Computation of Primitive Accuracy (PA) |

Require: Input point cloud ; predicted primitives ; MRD threshold Ensure: Primitive Accuracy score

- 1:

Step 1: Compute radial distances for all input points: for each - 2:

Initialize valid primitive count - 3:

for each primitive , where do - 4:

Step 2: Apply inside mask to select enclosed points: - 5:

Step 3: Compute mean radial distance (MRD): - 6:

Step 4: Identify mismatched primitives: - 7:

if then - 8:

- 9:

end if - 10:

end for - 11:

Compute corrected precision: - 12:

Combine geometric fit quality with corrected precision: - 13:

return PA

|

To compute the

Overlapping Percentage, we first determine the number of points that are shared across different primitives. This count is then normalized by the total number of sampled surface points across all primitives, and the result is expressed as a percentage. Formally, the metric is defined as:

To compute the set of overlapping points, each surface point sampled from one primitive is tested against all other primitives using their implicit superquadric equations. The overlap condition for each sampled point is defined as:

The total number of overlapping points is obtained by summing over all sampled points and counting those that lie within at least one other primitive:

The indicator and evaluation functions used for geometric and segmentation analysis are summarized in

Table 2.

7.2. Experiments

We now present our experimental results obtained using the ShapeNet dataset [

48]. For consistency, we employ the official implementation of the

baseline method described in [

5].

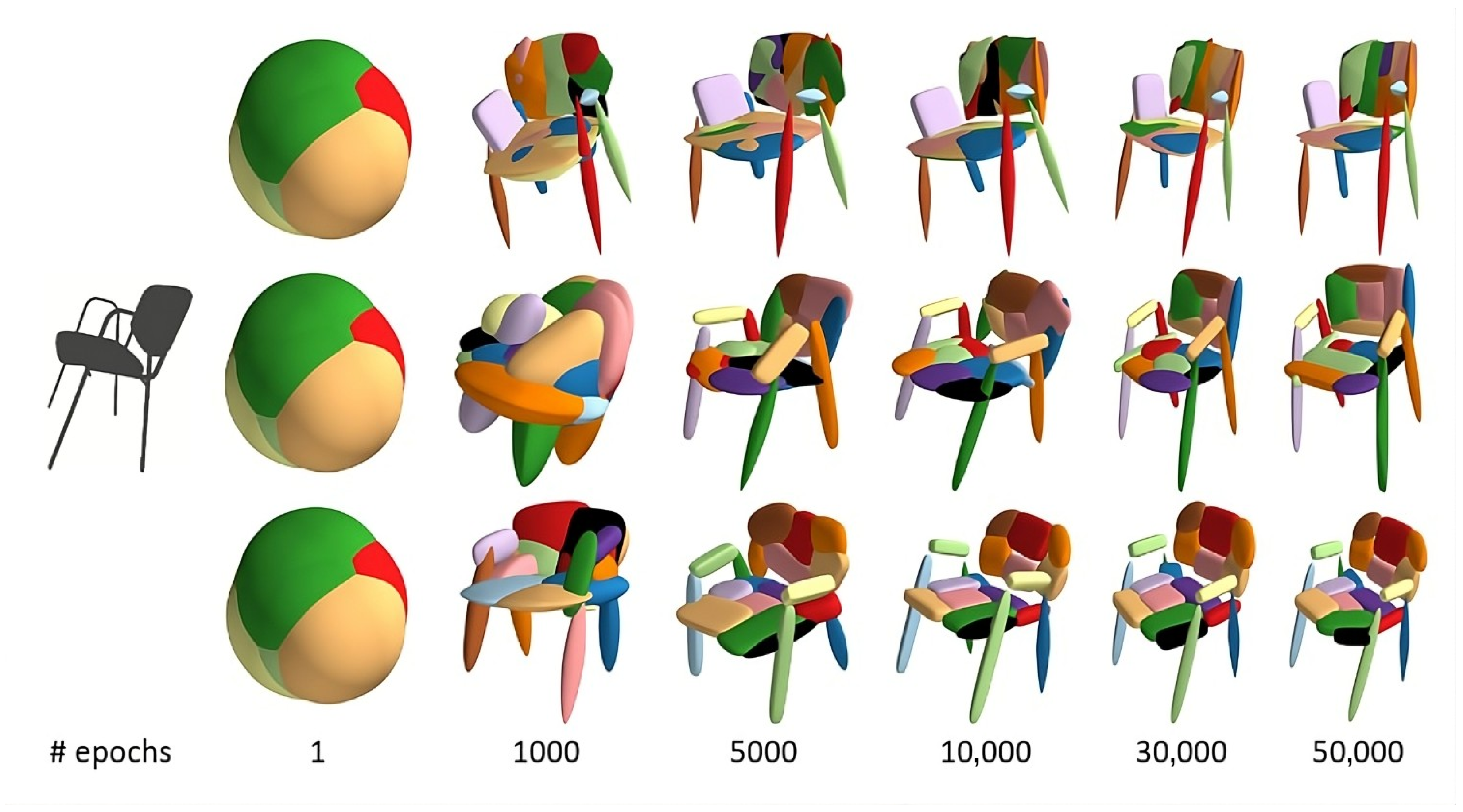

Experiments are conducted on three representative object categories: chairs, airplanes, and tables. For each category, we select 20 samples, following the common practice in prior unsupervised shape decomposition studies [

5,

22]. Although the sample size may appear limited, this choice reflects the high computational cost associated with training and evaluation. Each object is represented using a fixed number of 20 superquadrics, ensuring consistency across all categories. This configuration offers a balanced trade-off between representational expressiveness and computational efficiency. In the experiments and tables, we refer to our previous model [

6] as

Eltaher for brevity.

All experiments are performed on a single NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with each training session requiring approximately six hours to complete. We focus on the superquadric-based family of models [

5,

6], as they share a common implicit parametric structure and unsupervised optimization framework, ensuring methodological consistency and fair comparison.

Regarding evaluation metrics, conventional surface-based distances such as Chamfer Distance (CD) or Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) are not used, as they primarily measure geometric proximity rather than structural fidelity. In the context of primitive-based shape abstraction, such metrics fail to capture essential factors like inter-primitive overlap, mismatched part assignments, or structural validity. Instead, we employ the proposed metrics—Structural Accuracy and Primitive Accuracy—which offer a more interpretable and task-relevant assessment of how well each predicted primitive represents the input geometry while preserving structural coherence.

7.2.1. Experiment 1: Comparison of Sampling Strategies

This experiment analyzes the effect of the traditional and proposed sampling strategies on the performance of two superquadric-based methods: the

baseline method [

5] and the

Eltaher method [

6]. The results in

Table 3 indicate that the proposed uniform sampling strategy improves both Primitive Accuracy and Corrected Precision, particularly for the

Eltaher method, while maintaining comparable performance in Overlapping Percentage and Structural Accuracy.

For the baseline method, switching from the traditional to the proposed sampling strategy yields a slight improvement in Primitive Accuracy (from an average of 0.036 to 0.058), accompanied by a minor decline in Structural Accuracy (from 0.90 to 0.88). This trade-off can be attributed to the following factors:

Primitive Accuracy Improvement: The proposed sampling strategy enables a more uniform and representative distribution of surface points, reducing segmentation errors and improving the reconstruction accuracy of individual superquadrics.

Structural Accuracy Decline: The moderate decrease in Structural Accuracy indicates that, although the new sampling promotes more coherent segmentation, it may marginally reduce the tightness of fit between reconstructed primitives and the input point cloud.

Overlapping Percentage Consistency: The overlapping percentage remains constant at 0.99, indicating that the baseline method continues to exhibit excessive primitive intersections, reflecting an absence of explicit constraints to enforce non-overlapping segmentation.

In

Table 3, the Corrected Precision value of

0.00 observed for the baseline method may appear anomalous. This outcome occurs when the baseline model attempts to decompose objects containing topological holes (e.g., mugs with handles). Because superquadrics represent closed surfaces by definition, the decomposition cannot accurately capture such open or hollow structures. Consequently, nearly all predicted primitives fail to correspond to the target shape components, resulting in a Corrected Precision value of zero. This observation underscores the limitation of relying solely on Structural Accuracy or distance-based metrics, as these can be misleading when evaluating complex or topologically nontrivial shapes. The Corrected Precision metric was thus introduced to provide a more reliable assessment of primitive correctness in such challenging scenarios.

For the Eltaher method, the uniform sampling strategy yields a distinct improvement in Primitive Accuracy, increasing from an average of 0.59 to 0.65. In contrast, Structural Accuracy shows a modest decrease from 0.90 to 0.84. These variations are primarily explained by the following factors:

Improved Primitive Accuracy: The Eltaher method demonstrates greater improvement under the uniform sampling strategy owing to its refined primitive fitting mechanism. The refined point selection enables the model to align predicted superquadrics more accurately with the geometric structure of the object.

Moderate Structural Accuracy Reduction: Although individual primitives more accurately represent local shape components, the overall reconstruction can exhibit minor gaps or misalignments between adjacent parts, slightly reducing overall structural coherence.

Stable Overlapping Performance: The Eltaher method consistently maintains low overlapping percentages (ranging from 0.15 to 0.28) due to its integrated spatial separation constraints. The slight increase observed with uniform sampling (maximum value rising from 0.20 to 0.28) likely indicates improved geometric coverage rather than deviation from strict non-overlap.

Summary

Baseline Method: The uniform sampling strategy yields a moderate increase in primitive accuracy (from 0.036 to 0.058 on average). However, the overlapping percentage remains substantially high (unchanged at 0.99), and structural accuracy shows a minor decrease (from 0.90 to 0.88), as reported in

Table 3.

Eltaher Method: The uniform sampling strategy produces a notable improvement in primitive accuracy (from 0.59 to 0.65 on average), accompanied by a slight reduction in structural accuracy (from 0.90 to 0.84). Nevertheless, the method maintains a substantially lower overlapping percentage (ranging from 0.20 to 0.28) compared with the baseline approach.

Structural vs. Primitive Accuracy Trade-off: The results indicate that improvements in primitive accuracy are often accompanied by a slight reductions in structural accuracy. This observation suggests that improved part-level fitting and segmentation may occur at the expense of global shape coherence.

7.2.2. Experiment 2: Effect of the Number of Sampled Points per Primitive

This experiment investigates how varying the number of sampled points per primitive (200 and 100) affects the performance of the baseline method [

5] and the Eltaher method [

6], evaluated under both the old and uniform sampling strategies. The results for all configurations are summarized in

Table 4, based on evaluations conducted on the mug category from the ShapeNet dataset. The evaluation metrics considered are: Overlapping Percentage, Structural Accuracy, Primitive Accuracy, and Corrected Precision.

For the

baseline method, the Overlapping Percentage is constant at 0.99 across all configurations. This consistency indicates that the baseline method exhibits persistent excessive intersection among primitives, independent of the sampling strategy or point count. This observation supports the conclusion drawn from

Table 4 that the method lacks explicit mechanisms to penalize overlap during reconstruction.

Structural Accuracy is stable at 0.90 across all conditions, suggesting that the baseline method’s shape-fitting performance is largely unaffected by changes in sampling density. However, Primitive Accuracy increases appreciably with the uniform sampling strategy:

With 200 points per primitive, Primitive Accuracy increases from 0.036 (old sampling) to 0.077 (uniform sampling).

With 100 sampled points per primitive, Primitive Accuracy further increases to 0.083.

This improvement suggests that the uniform sampling strategy yields more informative point distributions, facilitating more accurate segmentation of individual primitives. However, Corrected Precision shows a slight decrease from 0.10 (with 200 points) to 0.050 (with 100 points), indicating that reduced point density can impair geometric precision in certain cases.

For the Eltaher method, the Overlapping Percentage is considerably lower than that of the baseline approach. The Overlapping Percentage increases slightly when fewer points are used:

Under the previous sampling strategy, overlapping increases from 0.20 (with 200 points) to 0.28 (with 100 points).

Under the uniform sampling strategy, the overlapping value increases slightly from 0.20 to 0.24.

These small increases suggest that although the Eltaher method effectively constrains overlaps through its architectural design, lower sampling densities can introduce minor geometric instability. Structural Accuracy shows a slight decrease from 0.90 (under the previous sampling strategy) to 0.84 (under the uniform sampling strategy), consistent with the trends observed in Experiment 1. This trade-off likely reflects a shift in optimization focus toward enhanced segmentation quality at the expense of precise global alignment.

Primitive Accuracy improves under the uniform sampling strategy:

These results indicate that the uniform sampling strategy enhances segmentation quality even with reduced point density and aligns effectively with the Eltaher method’s primitive-fitting design. Corrected Precision remains constant at 1.00 across all configurations, underscoring the robustness of the Eltaher method’s segmentation performance.

The key findings from this experiment can be summarized as follows:

Baseline Method: The uniform sampling strategy improves Primitive Accuracy, but the Overlapping Percentage remains high, and Structural Accuracy is largely unaffected by the number of sampled points (see

Table 4).

Eltaher Method: The uniform sampling strategy improves Primitive Accuracy while maintaining relatively low Overlapping Percentages, demonstrating superior segmentation quality across varying sampling densities.

Effect of Points per Primitive: Using 100 points per primitive often yields slightly higher Primitive Accuracy, whereas 200 points produce lower Overlapping Percentages, making the latter configuration preferable when aiming to reduce segmentation redundancy.

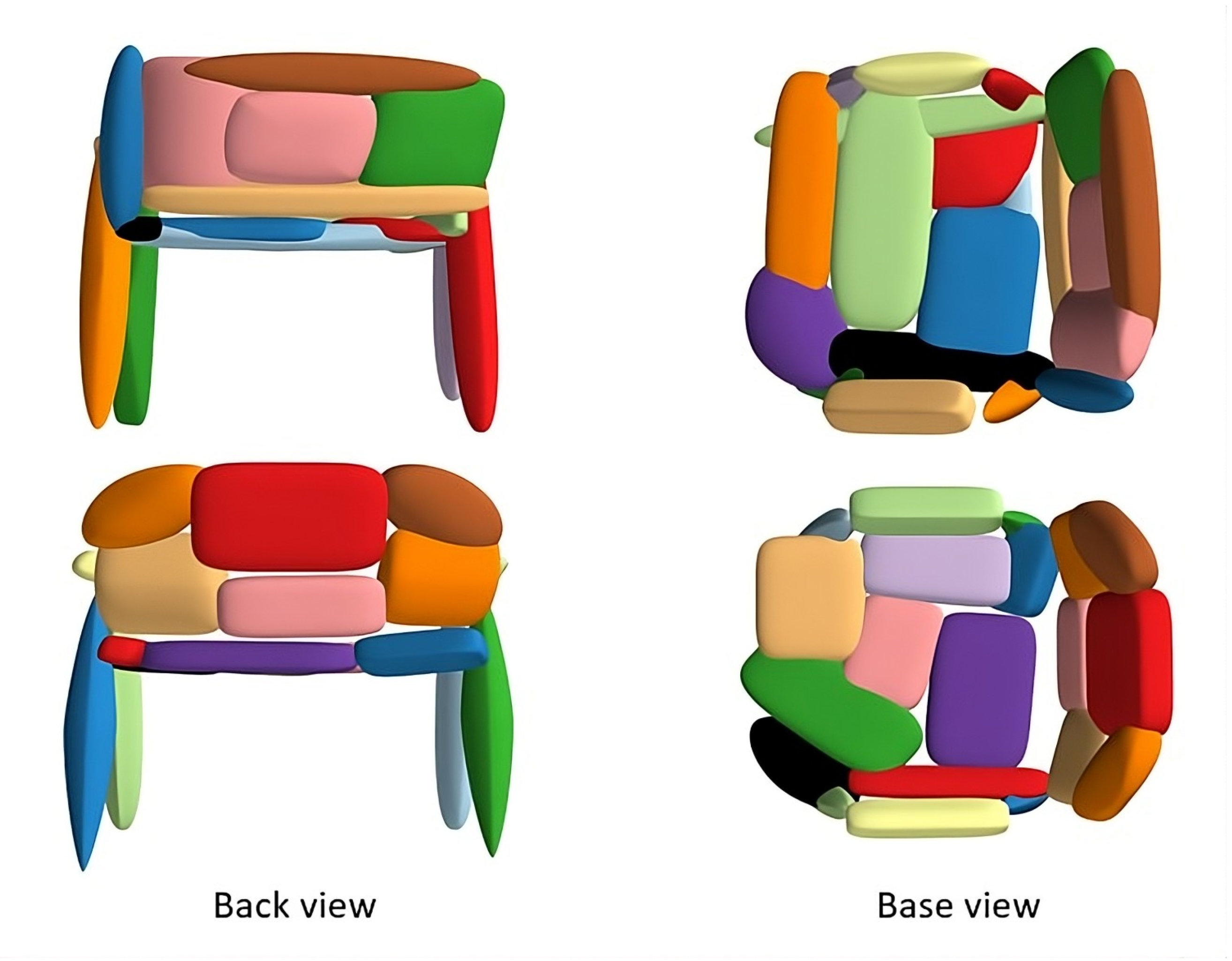

Figure 7 provides qualitative support for these findings, illustrating segmentation coherence across sampling configurations. Segmentations generated using the uniform sampling strategy with 200 points appear more coherent and better aligned with object parts, particularly in challenging regions such as the mug handle. The Eltaher method exhibits the most visually consistent performance, characterized by minimal fragmentation and high part-level fidelity.

Overall, the findings support the conclusion that combining the uniform sampling strategy with a higher point density achieves an optimal balance between precise primitive segmentation and minimal inter-primitive overlap, particularly in the Eltaher method.

7.2.3. Experiment 3: Effect of Overlapping Loss on Baseline and Eltaher Methods

This experiment examines the effect of introducing an overlapping loss to both the baseline method [

5] and the Eltaher method [

6]. The evaluation results, summarized in

Table 5, are reported in terms of Overlapping Percentage, Structural Accuracy, Primitive Accuracy, and Corrected Precision. All values represent averages computed over ten independent runs on the mug category of the ShapeNet dataset.

For the baseline method, incorporating the overlapping loss does not reduce the Overlapping Percentage, which remains constant at 0.99. This finding indicates a persistent tendency toward excessive primitive overlap, suggesting that overlapping loss alone is insufficient to mitigate this limitation. Nonetheless, small improvements are observed in both Structural and Primitive Accuracy. Structural Accuracy increases from 0.88 to 0.89, while Primitive Accuracy rises from 0.0365 to 0.0636. However, Corrected Precision remains unchanged at 0.10, indicating that segmentation precision does not improve under this configuration.

In contrast, the Eltaher method exhibits greater performance improvements. The Overlapping Percentage decreases from 0.24 to 0.20, while Primitive Accuracy rises from 0.60 to 0.64. These results suggest that the overlapping loss effectively mitigates over-segmentation and promotes improved geometric alignment. A slight decrease in Structural Accuracy is noted (from 0.93 to 0.91), which may reflect a limited trade-off in fitting flexibility. However, Corrected Precision remains constant at 1.00 in both cases, indicating high consistency and reliability in the segmentation output.

The key findings from this experiment can be summarized as follows:

For the baseline method, the overlapping loss yields minor improvements in accuracy metrics but does not reduce overlap. Corrected Precision remains low, indicating limited practical benefit.

For the Eltaher method, the overlapping loss leads to enhanced primitive separation and accuracy, with only a minimal reduction in Structural Accuracy. Corrected Precision remains constant at 1.00, demonstrating stable segmentation performance.

Overall, the overlapping loss demonstrates higher effectiveness in enhancing segmentation quality when applied to more expressive architectures such as the Eltaher method, while offering limited improvement for the baseline approach.

7.2.4. Experiment 4: Comparison Across Object Categories

This experiment evaluates the performance of the proposed model against the baseline method [

5] and the Eltaher method [

6] on three object categories from the ShapeNet dataset: chairs, airplanes, and tables.

Table 6 presents the results for each method in terms of Overlapping Percentage, Structural Accuracy, Primitive Accuracy, and Corrected Precision, averaged over twenty input shapes per category.

Chair category. Chairs exhibit thin structures and complex geometries that pose significant challenges for segmentation models. The baseline method shows limited performance, exhibiting a high overlapping percentage (0.89) and the lowest structural accuracy (0.81), indicating substantial primitive intersection and weak overall shape representation. The Eltaher method reduces overlap to 0.30, leading to a marked improvement in structural accuracy (0.94), although primitive accuracy remains limited at 0.52. The proposed model achieves further gains, with reduced overlap (0.22), higher primitive accuracy (0.61), and perfect corrected precision (1.00), suggesting improved segmentation fidelity and more precise primitive placement.

Airplane category. The streamlined shapes and symmetrical components of airplanes pose significant challenges for accurate geometric decomposition. The baseline method exhibits an overlapping percentage of 0.64 and a lower primitive accuracy (0.47), reflecting imprecise segmentation of major structural components. The Eltaher method improves primitive accuracy to 0.63 while reducing the overlapping percentage to 0.40. The proposed model further increases primitive accuracy to 0.69, exhibiting a slightly higher overlap (0.45) than the Eltaher method, along with a modest reduction in structural accuracy (from 0.95 to 0.90). Both methods maintain a corrected precision of 1.00, indicating accurate and consistent boundary delineation.

Table category. Tables generally feature flat surfaces and thin supports, which pose challenges for achieving accurate and clean segmentation. The baseline method shows the weakest performance, with an overlapping percentage of 0.97 and the lowest primitive accuracy (0.44). The Eltaher method lowers overlap to 0.33 and attains a structural accuracy of 0.96, although primitive accuracy remains low at 0.43. The proposed model further reduces overlap to 0.24 and substantially improves primitive accuracy to 0.69. Corrected Precision attains a value of 1.00, and despite a slight decrease in Structural Accuracy (from 0.96 to 0.90), the results indicate an overall improvement in decomposition quality.

Qualitative validation. Figure 8 and

Figure 9 provide qualitative validation and visual support for these observations. Compared with the baseline and the

Eltaher method, the proposed model produces cleaner and more compact segmentations. Primitive boundaries align more consistently with the underlying object geometry, avoiding the oversized and redundant primitives observed in the baseline and improving upon the moderate overlap present in the

Eltaher method.

The key findings from this qualitative analysis can be summarized as follows:

The proposed model consistently reduces the overlapping percentage across all categories, particularly for complex shapes such as chairs and tables.

Primitive accuracy is higher in all cases, indicating improved geometric correspondence and more accurate primitive assignment.

Corrected Precision remains constant at 1.00 across all categories, demonstrating high consistency and reliability in primitive placement.

Structural Accuracy exhibits minor variation, reflecting trade-offs between precise surface fitting and enhanced segmentation compactness.

7.2.5. Experiment 5: Visual Comparison of Segmentation Quality

This experiment presents a qualitative analysis of segmentation quality across multiple object categories, as illustrated in

Figure 10. The comparison highlights the differences among the proposed method, the baseline approach [

5], and the

Eltaher method [

6], with a particular focus on challenging categories such as chairs, tables, mugs, and bags.

Chair category. Chairs are structurally complex objects, characterized by thin components and intricate interconnections. The baseline method exhibits excessive overlap, resulting in primitive extensions that obscure the boundaries between arms, seats, and backrests. The Eltaher method improves segmentation by reducing overlap and enhancing part-level separation. However, primitive misalignments persist, particularly around the base and backrest regions. The proposed method produces clearer boundaries and more accurately aligned primitives, particularly in the arm and leg regions. This leads to a more coherent and perceptually natural decomposition.

Table category. Tables present segmentation challenges due to their flat top surfaces and thin supporting structures. The baseline method exhibits limited differentiation between components, resulting in redundant and oversized primitives. The Eltaher method reduces overlap and enhances component separation, although certain structural inconsistencies persist. The proposed method yields the cleanest segmentation, effectively separating the tabletop from the supporting legs with minimal overlap. The resulting primitive layout produces a more accurate and compact representation of the overall structure.

Mug and bag categories. These categories are characterized by curved geometries and fine structural details. The baseline method exhibits significant primitive overlap, resulting in misalignment and poor coverage of distinct components, such as the handle of a mug or the folds of a bag. The Eltaher method enhances structural coherence but still exhibits occasional primitive misplacement. In contrast, the proposed method achieves precise segmentation, accurately capturing the mug’s handle and following the natural contours of the bag with minimal redundancy.

Visual evidence. Figure 10 illustrates that the proposed method consistently yields the most compact and clean primitive representations. The

baseline method exhibits severe over-segmentation, while the previous approach achieves moderate improvements. In contrast, the proposed model demonstrates the highest visual quality, with superior primitive alignment and structural consistency.

The key findings from this visual comparison can be summarized as follows:

The proposed model outperforms both the baseline and the Eltaher method in visual segmentation quality, particularly for geometrically complex shapes.

Primitive alignment and boundary clarity are substantially improved, especially in detailed regions such as handles and structural joints.

The visual results reinforce the quantitative improvements, confirming the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed method across diverse object categories.

7.4. Quantitative Comparison with Prior Work

A detailed quantitative comparison with our previous framework [

6] is presented in

Table 6. For the

chair category, the overlapping percentage decreases by about 8%, while Primitive Accuracy improves by 9% and Corrected Precision increases from 0.85 to 1.00. Structural Accuracy shows a marginal decrease from 0.94 to 0.92, reflecting a small trade-off between global coverage and tighter primitive alignment.

In the airplane category, Primitive Accuracy rises from 0.63 to 0.69 (a 6% gain), accompanied by a slight increase in overlap (+5%) and a moderate drop in Structural Accuracy from 0.95 to 0.90. This again highlights the inverse relationship between Primitive and Structural Accuracy: as primitives fit more tightly to local geometry, global coverage becomes marginally reduced.

For the table category, the improvements are more pronounced. The overlap decreases by 9%, Primitive Accuracy increases by 26%, and Corrected Precision rises from 0.70 to 1.00, while Structural Accuracy slightly decreases from 0.96 to 0.90. This pattern confirms that stronger local fitting and reduced redundancy may come at the expense of minor reductions in overall surface coverage.

On average across categories, the proposed model achieves a reduction in overlap of approximately 4–6%, an improvement in Primitive Accuracy of about 13%, and maintains Structural Accuracy within a narrow range (−2% to −6%), indicating stable global structure preservation.

Visual comparisons in Experiment 5 further confirm these trends, showing that the proposed method produces cleaner, more compact primitive layouts with improved boundary alignment and fewer redundant components. These improvements stem from the integration of the overlapping loss and uniform surface sampling strategy, which collectively enhance geometric regularity and segmentation stability without altering the network architecture.

Empirical trends across both the ShapeNet category results (

Table 6) and the sampling analysis (

Table 3) further confirm the complementary behavior of the proposed evaluation metrics. A reduction in Overlapping Percentage (OP) consistently corresponds to higher Primitive Accuracy (PA), reflecting improved local geometric fidelity. Conversely, Structural Accuracy (SA) exhibits a mild inverse relationship with PA: as primitives become more tightly aligned with individual components, global coverage decreases slightly. This trade-off reflects the inherent balance between compact, non-redundant part fitting (high PA) and broad structural coverage (high SA), which naturally compete during reconstruction. Together, these findings demonstrate that OP, SA, and PA capture distinct yet interrelated aspects of reconstruction quality—redundancy, global coverage, and local alignment—thereby validating the interpretability and complementarity of the proposed evaluation framework.