Abstract

Background: Technological progress in the field of prosthetic dentistry has changed the workflow, optimizing times and increasing the possible choices of prosthetic rehabilitation. Methods: The adaptability of three resin plates to the plaster model was evaluated by visual evaluation and by filling out a questionnaire in which two areas present in three silicone impressions obtained with three different construction methods were selected, including the traditional method, CAD/CAM method for milling, and CAD/CAM method for addition. Results: The results showed that although silicone 3 obtained with the additive method had better performances in the selected areas, the p-value of 0.735 was >0.05, and therefore there are no statistically significant differences between the different silicone impressions. Furthermore, a poor agreement between the evaluators was found (k 0.184). Conclusions: This work conducted in vitro highlights an important aspect of the choice of material used for impressions in cases of prosthetic relining. More in-depth studies with larger samples and objective measurement methods will be needed to compare fit data across different prosthetic construction modalities.

1. Introduction

Dentistry is constantly evolving, and increasingly innovative technologies allow for a modern, digital, computer-assisted approach. In the era of digitalization, CAD/CAM software represents a milestone in the design and production of increasingly precise objects that replace the manual and painstaking work of the dental technician. In dentistry, Dr. Francois Duret was the first to develop a dental CAD/CAM device, creating crowns based on an optical impression of the abutment tooth, describing the advantages and disadvantages of using the new technology [1]. Today, digital technology is present in almost all dental offices and laboratories; consequently, the use of computers in dental offices has increased exponentially, allowing operators to improve many aspects, including esthetics that would otherwise be obtained with different design strategies [2,3]. These new technologies have pushed researchers to study not only the correct use of innovative technologies but also their application and limits in different branches of dentistry [4]. Many works relating to CAD/CAM present in the literature concern studies conducted for the creation of fixed prostheses, inlays, partial prostheses, or implant prostheses; there are much fewer studies focused on total prostheses. Today, complete dental prostheses built with the CAD/CAM technique are slowly replacing conventional methodologies that require multiple sessions and long laboratory procedures, as well as significant modifications by professionals. In one work, Arslan M et al. found higher values of flexural strength and hydrophobicity of polymers based on PMMA CAD/CAM compared to conventional hot-cured PMMA, while polymers based on PMMA CAD/CAM had roughness values similar to conventional PMMA [5]. Abualsaud R. et al., in a systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies, in their conclusions reported that the subtractive CAD/CAM technique of prosthesis fabrication showed satisfactory flexural strength values, while the additive CAD/CAM method was comparable to the conventional heat-cured technique with a lower value [6]. Prpić V et al. report in another work that 3D-printed materials had the lowest flexural strength values, and in their conclusions, they highlight how the type of polymerization of a material is not a guarantee of its optimal mechanical properties [7]. Mert D. et al. examined the shear resistance in relines in relined, milled, and traditional 3D-printed samples and reported that the shear resistance was significantly lower than the conventional and milled groups. There were no differences in the shear resistance between the milled and conventional groups; in fact, they recommend the use of 3D printing for the fabrication of complete dentures in clinical situations where a frequent need for relining of the dentures is not expected [8]. The use of one or the other 3D printing method, the milling method or conventional method, for the creation of a total prosthesis depends on certain factors, including the speed of production, the reduction in clinical steps, and the precision of the product. Factors such as a 3D printer, resin, design geometry, printing parameters, support parameters, sectioning procedures, and postprocessing procedures can influence the surface roughness, printing accuracy, and mechanical properties of the additive dental device. Furthermore, the different statistical calculations or algorithm models developed in engineering to determine the optimal printing parameters of vat polymerization procedures to produce the minimum error in building the part in dentistry are normally provided by the material and printer manufacturer guidelines as a standard manufacturing protocol, and these can influence the printing for some dental polymers processed in different vat polymerization printers due to the wavelength compatibility between the material and the 3D printer [9].

In a clinical study conducted to compare the retention values of heat-cured conventional denture bases to those of digitally milled maxillary denture bases by pulling the denture base with a vertical pull force using an advanced digital force gauge three times at 10 min intervals, AlHelal A. et al. found that the retention afforded by denture bases milled from pre-polymerized polymethyl methacrylate resin were significantly higher than those afforded by denture bases that were conventionally heat-cured [10]. The evolution of digital technology has allowed software program manufacturers to obtain increasingly high-performance products for the creation of prosthetic products, and therefore the choice of software has been oriented towards the precision of production and the accuracy of the program. A systematic review performed by Wang C et al. evaluated the accuracy of digital CDs by summarizing the factors that influence it; in their conclusions, they report clinically acceptable values for the occlusal veracity and fit of digital CDs, a mismatch of the notch surface in the posterior palatal seal area and in the edge seal area, and doubts about the superiority of CAD/CAM milling and 3D printing regarding the accuracy of the prosthesis [11]. In recent years, technologies have provided a notable boost in the prosthetic field by trying to improve all those aspects that with the conventional technique take longer and are more difficult to create, especially in the precision of manufacturing the base of a prosthesis with the three techniques by evaluating the plaster models and scanned models [12]. The objective of this in vitro study was to evaluate the adaptability and accuracy of the prosthetic plates to the plaster model of an edentulous upper arch made with three different construction methods: traditional method (TM—traditional method) with hot acrylic resin, CAD/CAM by addition (3D printer) (AM—additional method), and CAD/CAM by subtraction (milling) (MM—milling method) made on a single plaster model.

2. Materials and Methods

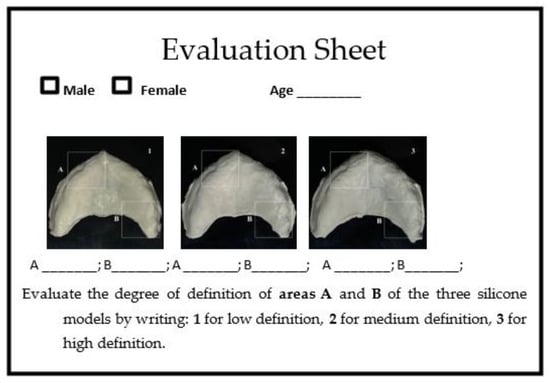

The materials used for our testing include extra-hard plaster (Suprastone ultra-hard plasterTM), Promolux® acrylic resin (Merz Dental GmbH, Lütjenburg, Germany), SmileCam® micro-refilled PMMA (pressing-dental, San Marino Republic), Raydent® composite resin (Ray America Inc., Fort Lee, NJ, USA), Fit Checker Advanced® vinyl-polyether (deformation-resistant material with good adaptability and sliding capacity). The equipment used includes Exocad® CAD software DentalCAD 3.1 Rijeka, the HyperDent® milling machine, the Chitubox® 3D printer, a digital scale, 3 weights for a total of 1400 kg, and a circular base weighing 49 g. All prosthetic bases were made by the same operator. For the analysis and comparison of the definition of the silicone models, two areas were limited and examined: the first area (A) includes the mesial portion of the I quadrant, and the second area (B) includes the distal portion of the II quadrant. To carry out the comparison between the two areas in the three silicone models, the degree of definition and macroscopic details of the circumscribed areas were evaluated through a visual examination. To make the evaluation criterion as objective as possible, a sample of 15 dentists with at least 10 years’ experience in the prosthetic field were asked, via an anonymous digital evaluation form, to classify the macroscopic definition of the three silicones obtained from the three bases constructed with different methods, without declaring the correspondence of the numbers to the construction method, defining a ranking ranging from 1 to 3, where “1” is the value with the lowest definition, “2” corresponds to the normal definition, and “3” is the value with the highest definition. We conducted a statistical analysis of the collected data.

2.1. Creation of the Model

The plaster model used for the experimental evaluation was obtained following the traditional steps [13,14,15]:

- First impression: The impression of the upper arch is taken using alginate (irreversible hydrocolloid) and a commercial impression tray.

- First plaster model: From the alginate impression, a hard plaster model is obtained (the plaster we use is HydrocalKerrTM) on which to build the individual resin impression tray (impression tray resin LC—Henry Schein®).

- Second impression: The second impression is taken using Permlastic™ condensation polysulfide and the individual impression tray built on the previously obtained plaster model.

- Second plaster model: From the second impression, the definitive model is obtained using Class IV extra-hard plaster in order to have high resistance characteristics and smooth surfaces (Suprastone ultra-hard chalkTM) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Extra-hard plaster model used for experimentation.

Figure 1. Extra-hard plaster model used for experimentation.

2.2. Construction of the Plates with the Three Methods

2.2.1. Traditional Method

- Waxing of the model: The plate is created on the plaster model with a sheet of wax (the teeth have been mounted in our model).

- Putting into the muffle: The plaster model with the waxing is inserted into the muffle (mold and counter-mold), and everything is placed in a kettle to melt the wax. Once the muffle has been opened and the mold and counter-mold have been washed with hot water to eliminate wax residues, we proceed to carry out the retentions in the teeth.

- Resin packing: The resin we have chosen is Promolux, a hot polymerizing resin with color stability based on methyl methacrylate. Once the powder is mixed with the liquid and the initial plasticity consistency is obtained, it is inserted into the muffle.

- Polymerization: The closed muffle is inserted into the kettle at a programmed temperature of 70 degrees for 30–60 min, and then the kettle brings the temperature to 100 degrees for 30 min.

- Finishing: After polymerization, the flask is opened, the resin prosthesis is removed, and it is finished with suitable cutters and rubbers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Total upper mobile prosthesis made with the traditional method.

Figure 2. Total upper mobile prosthesis made with the traditional method.

The traditional construction method can be influenced by some parameters reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters that can influence the construction traditional method.

2.2.2. CAD/CAM Method for Milling

- Model scanning: The plaster model inserted into the scanner is scanned to obtain a three-dimensional digital model using software.

- Design: The digital model obtained from the scan is imported into CAD software (Exocad®), where the digital model of the prosthetic plate is created

- Milling: Once the design of the prosthesis in the CAD software is completed, a CAM file is generated which is sent to a software that manages the milling machine (HyperDent®) that contains the information necessary for milling. A micro-filled disk in PMMA (Smile Cam®) is milled until the previously designed plate is obtained

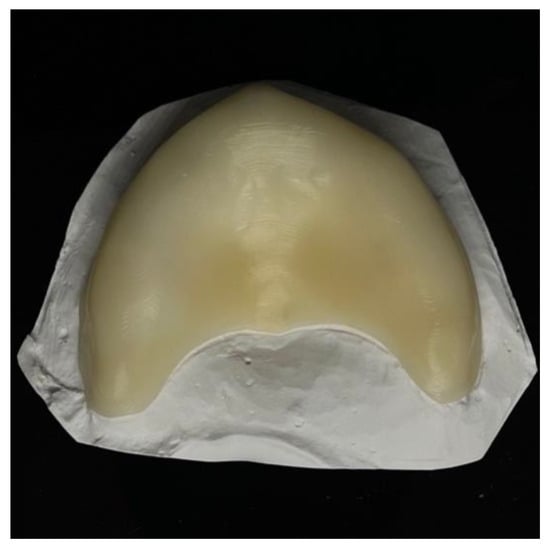

- Verification and adaptation: The prosthetic plate is then tried on the model to verify the adaptation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Upper prosthetic plate obtained with a CAD/CAM milling system.

Figure 3. Upper prosthetic plate obtained with a CAD/CAM milling system.

Several parameters, reported in Table 2, can influence the milling-based construction method during the CAD design and CAM manufacturing stages.

Table 2.

Parameters that can influence the milling-based construction method during the CAD design and CAM manufacturing phases.

2.2.3. CAD/CAM Method for Addition

- Model scanning: The plaster model inserted into the scanner is scanned to obtain a three-dimensional digital model using software.

- Design: The digital model obtained from the scan is imported into Exocad® CAD software, where the digital model of the prosthetic plate is created.

- Printing of the plate: The digital model is prepared for printing, correctly positioning the prosthesis on the virtual support plate. The CAD file is sent to the Phrozen® 3D printer, where the printing parameters are set via a software that manages the 3D printer (Chitubox®), and the plaque is formed layer-by-layer. A Raydent® composite resin was used.

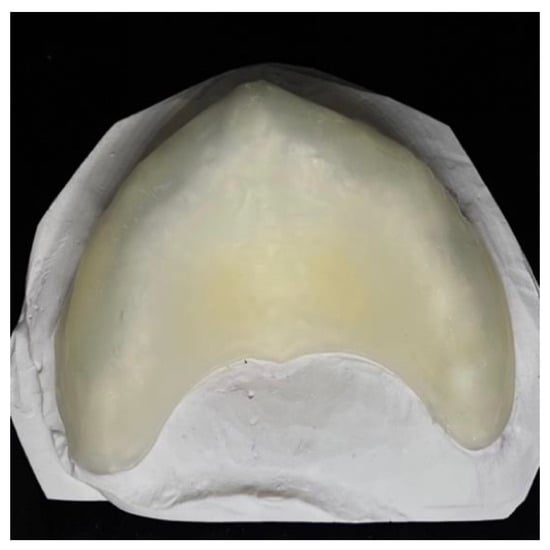

- Finishing: After printing, the plate is removed from the support plate and subjected to finishing and testing on the model to check the fit (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Upper prosthetic plate obtained with the addition of the CAD/CAM system.

Figure 4. Upper prosthetic plate obtained with the addition of the CAD/CAM system.

Several parameters, reported in Table 3, can influence the addition manufacturing method in the CAD design and CAM manufacturing phases.

Table 3.

Parameters that can influence the addition method during the CAD design and CAM manufacturing phases.

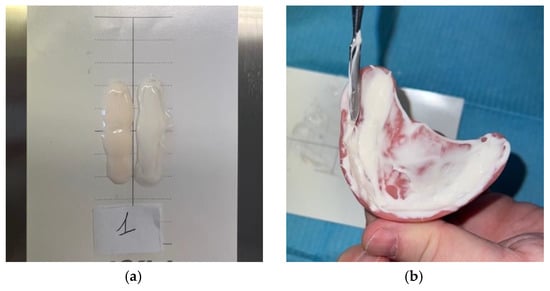

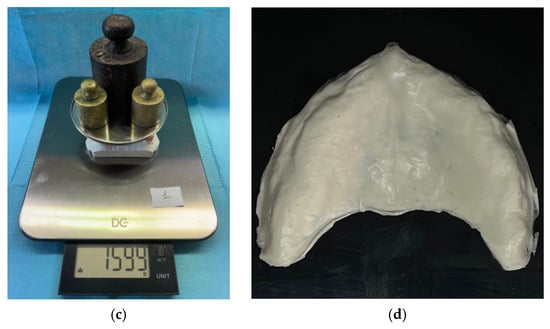

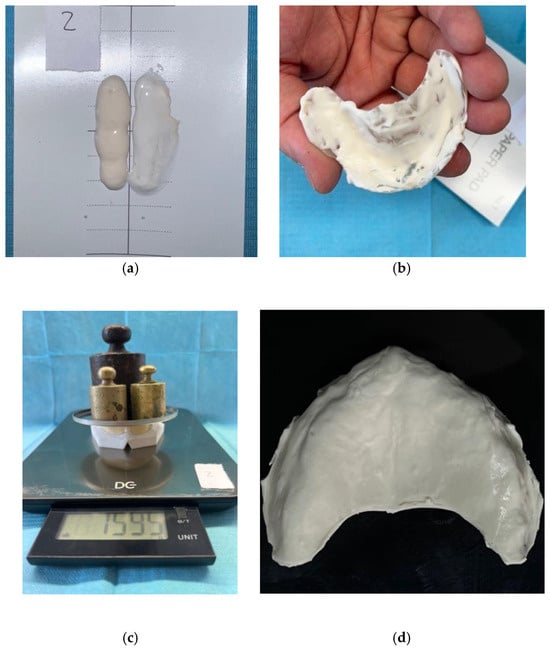

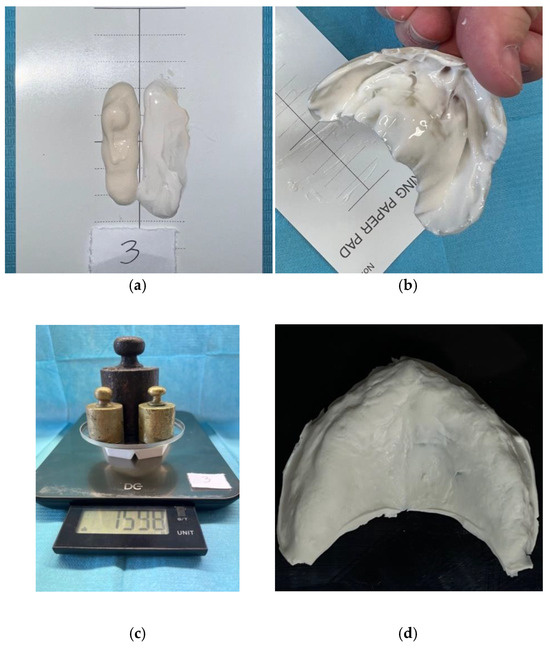

2.3. Creation of the Silicone Models to Be Examined

The evaluation of the adaptability of the three different prosthetic plates to the plaster model was performed through the use of a vinyl polyether material composed of a base paste and a catalyst commonly used in clinical practice (Fit Checker Advanced®) (Figure 5) for controlling pressure points on the mucosa. A digitally numbered precision scale was used to read the pressure exerted into the different prosthetic plates on the plaster model with 3 weights (1000 gr. + 200 gr. + 200 gr.) and a 49 gr. plate. In terms of where to insert the weights to equalize the pressure load, the Fit Checkermaterial was mixed on a mixing paper pad where notches are depicted which allow for the material to be quantified in equal measure for all three tests. The plates were numbered as n° 1—the plate made with the traditional method, n° 2—the plate made with the milling method, and n° 3—the plate made with the printing method. The silicone models were all made by mixing the vinyl polyether material, applied in the different plates, all inserted into the master model and subjected to pressure with a set weight of 1.449 kg (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). Before the experimentation, the plaster model was placed in a bowl with warm water for about 10 min in order to uniform the temperature and saturate the plaster to facilitate the sliding and removal of the vinyl polyether. Thus, the resin plates were also immersed in water at room temperature for 5 min to equalize the temperature. The silicone from the plates was carefully removed, obtaining a faithful representation of the texture of the palatal side of the prosthetic plate. All silicone models were made by the same operator.

Figure 5.

Fit Checker Advanced.

- a—Creation of the silicone with the prosthetic plate n° 1:

Figure 6. (a) Base paste and catalyst mixture; (b) Fit Checker applied to the plate; (c) plate inserted into the model and application of controlled pressure; (d) silicone obtained from plate n°1.

Figure 6. (a) Base paste and catalyst mixture; (b) Fit Checker applied to the plate; (c) plate inserted into the model and application of controlled pressure; (d) silicone obtained from plate n°1. - b—Creation of the silicone with the prosthetic plate n. 2:

Figure 7. (a) Base paste and catalyst paste; (b) mixture applied in the base obtained by milling; (c) Fit Checker applied to the plate; (d) silicone obtained from plate n° 2.

Figure 7. (a) Base paste and catalyst paste; (b) mixture applied in the base obtained by milling; (c) Fit Checker applied to the plate; (d) silicone obtained from plate n° 2. - c—Creation of the silicone with the prosthetic plate n° 3:

Figure 8. (a) Base paste and catalyst paste; (b) mixture applied in the base obtained by milling; (c) load applied on the model; (d) silicone obtained from plate n° 3.

Figure 8. (a) Base paste and catalyst paste; (b) mixture applied in the base obtained by milling; (c) load applied on the model; (d) silicone obtained from plate n° 3.

2.4. Statistics of the Data Collected

For the statistical analysis of the collected data, we used the variance and standard deviation to measure the dispersion of the data and the consistency of the evaluations between the different observers, the ANOVA test to compare the means of the adaptability and precision scores between the three construction methods and determine if there were statistically significant differences, and finally Fleiss’s Kappa to evaluate the inter-rater reliability, that is, the degree of agreement between the evaluations of the 15 dentists.

3. Results

The cards sent to the 15 dentists presented photographs of the three silicones that had to be evaluated for the definition by comparing them with the model obtained (Figure 9). No dentist had information about the experimentation or how the individual silicones were obtained; we asked only to express a vote based solely on viewing the images. All dentists responded and performed the visual evaluation of the three silicones. The results are reported in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 and Chart 1.

K = (0.470 − 0.350)/(1 − 0.350) = 0.184

Figure 9.

Digital evaluation sheet.

Table 4.

Values expressed by individual dentists.

Table 5.

Difference between the value of each observation and the mean (deviation from the mean) and data dispersion index (sum of squares) sample of 15 observers (dentists).

Table 6.

Data analysis with ANOVA.

Table 7.

Table to calculate Fleiss’s Kappa.

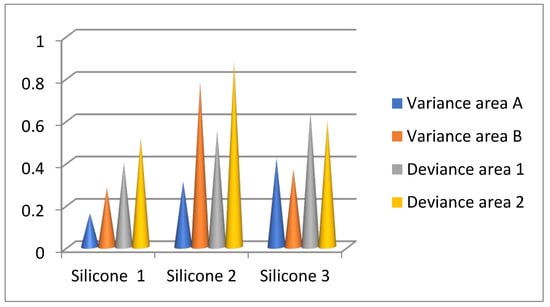

Chart 1.

Graphical representation of the differences in the different areas of variance and deviance.

The value of 0.186 falls into the category of “poor agreement”. This means that there is a low agreement between the dentists’ ratings on the silicone samples. The ratings are mostly similar to those that would be expected to be obtained by chance.

4. Discussion

Dentistry today has new tools that allow us to easily obtain all the information necessary to diagnose, study, plan, and carry out even more complex therapies in the simplest and least invasive way possible. The continuous progress made with the introduction of digital CAD/CAM technologies has represented a significant turning point in the profession in terms of precision, time, and waste reduction, all to the benefit of the result and comfort of the patient. A careful examination of the literature shows the effectiveness of CAD/CAM technology in the creation of total removable prostheses compared to conventional ones, especially in terms of time and resources. Willians A. et al. in a recent review of the literature highlighted that the introduction of a digital workflow reduces the visits required until the delivery of the complete prosthesis by at least one appointment compared to the conventional workflow and in any case depends on the experience of the doctor. Furthermore, it could provide rapid and reliable treatments for frail elderly patients who may suffer from motor dysfunction and cognitive deterioration, especially when duplicate prostheses are produced [16].

A recent systematic review of clinical trials analyzed the included studies and collected evidence demonstrating that 3D-printed CAD/CAM complete dentures appear to be comparable to conventional complete dentures in terms of overall patient satisfaction; however, 3D-printed complete dentures have raised some concerns regarding esthetics and speech [17].

However, all new technologies require continuous modifications aimed at improving processing. Tian Y et al., in a 2021 review, provided a practical and scientific overview of 3D printing technologies and also introduced some factors that can influence 3D printing, such as process parameters, material composition, postprocessing, and aging [18,19]. Also, Jeong M. et al. in a review highlighted the main categories of 3D printing materials such as polymers, metals, and ceramics, highlighting that although there are some limitations in terms of the precision and quality of printing, 3D printing technology is able to offer a wide variety of potential applications in different fields of dentistry, including dental prosthetics, implantology, oral and maxillofacial dentistry, orthodontics, endodontics, and periodontology [20]. Zahel A. et al. in a recent 2024 study compared the manufacturing accuracy, fracture resistance, and repairability of complete dentures constructed with conventional and digital methods, reporting that digitally produced complete dentures differ significantly from conventionally produced complete dentures in terms of greater accuracy in terms of digital production, fracture resistance, and greater repairability in conventional dentures, although they highlight that the data depend more on the shape of the dentition [21]. The retention and complete fit of the denture are strongly influenced by many factors such as the method of fabrication, the extension of the denture, the shape and compressibility of the supporting tissues, the thickness of the denture base, and the material from which the denture is constructed. Digital superimposition of the scanned denture fitting surface with scanned oral tissues or a cast is a recently introduced approach to evaluate and compare the fit of constructed dentures; therefore, the method of fabrication of the denture is important because it directly affects its retention and clinical performance [22,23]. A recent systematic review examined the mechanical properties and accuracy of removable partial denture frameworks fabricated using digital and conventional techniques, reporting that in vitro studies demonstrated that the digital technique provided similar accuracy to the conventional technique within a clinically acceptable range. The manufacturing technique influenced the mechanical properties of the removable partial denture components [24]. Our work did not evaluate the mechanical aspect of fracture resistance but rather the accuracy of the details imprinted in the silicone. Our results highlighted that there are no statistically significant differences in the adaptability of the prosthetic plates made with the three methods, in contrast to what has been reported by other works [25,26]. However, we observed greater variability in scores assigned by dentists for the traditional method, suggesting greater difficulty in assessing adaptation with this method. The results obtained with the ANOVA highlight that the p-value 0.735 is >0.05; therefore, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected. This demonstrates that there are no statistically significant differences in the observed groups and that the means of the different areas are similar to each other. The high variance (SSW 32.48) makes us understand that the variability in the data is due to differences within the individual groups rather than between the groups, i.e., due to the individual assessment of the dentist. This could also depend on several variants such as the software used for viewing the images, eye strain [27], subjective evaluation of the image, image lighting, and image quality.

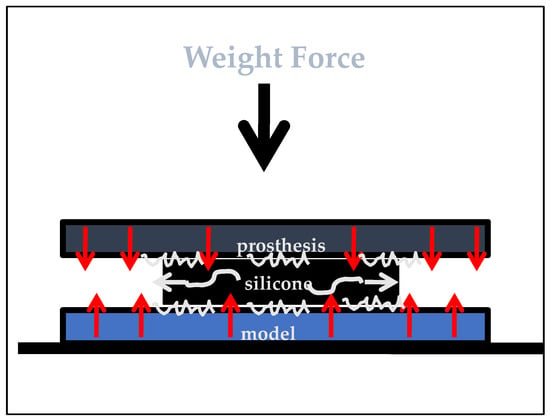

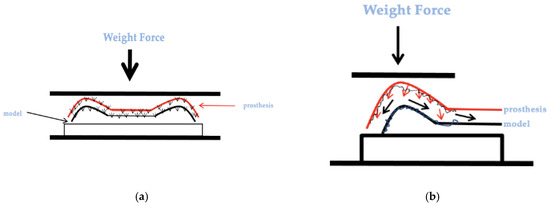

Fleiss’s Kappa value of 0.186 indicates poor agreement between dentists’ assessments. This value could be due to several factors, including unclear or uniformly understood assessment criteria; the subjectivity of the assessment; some dentists may have less experience in assessing this type of specimen, leading to less accurate assessments; the conditions under which the assessments were performed could influence the results, such as fatigue and distraction; and computer performance. It is clear that the sample size and the small differences between group means significantly influenced the power of the study. Even today, despite new software such as Photoshop, the belief is widely held that the photographic image constitutes a faithful and objective document certifying the actual existence of the reality it reproduces, validating that it is a faithful optical cast of a physical object; in our case, these are the photos of the silicones and the plaster model sent to dentists. Certainly, the digital workflow is not as long than the conventional method, although from a clinical and adjustment point of view, there are no differences between conventional and digital chairside workflows [28,29,30,31]. There are few works in the literature that describe the accuracy of different plates constructed with methods other than the model, and many of those evaluated the workflow and fracture resistance. Goodacre BJ et al. in a narrative review highlighted that the printing orientation influences the precision, strength, surface roughness, and adhesion of C. albicans, which is not found with conventional or milled denture materials [32]. Our work highlights a particular aspect of adaptability and accuracy: even if it is of a perceptive and visual nature, it expresses a judgment that does not differ from reality. The data obtained, however, as reported in the graph, highlight that although the three silicones report different variance and deviance values in the areas observed, the silicone obtained from the plate made with the additive method presents better performance in the two areas tested. This could be due to the greater precision of the printing in reproducing complex surfaces such as those of the plaster model. The three silicone impressions obtained could also have been influenced by the type of sliding of the vinyl polyether on the surface of the different resin material and on the plaster model; this also gives us important data for a possible rebasing on which silicone viscosity to use with different resins. In our in vitro experimentation, to minimize the forces opposing the sliding and standardize the tests, the weight for all three resins was applied in a constant and static way for 5 min without applying any additional force. Furthermore, to reduce the thermal effect on the silicone and standardize any friction on the plaster model, the temperature of the resins and the model was uniformed by immersion in water at room temperature and subsequent total drying for the resins, while the plaster model was dried by dabbing with absorbent paper so that it was saturated. The small weight variation of 0.3/0.4 g between the different tests is due to the arrangement of the weights. Some limiting mathematical aspects of our work mainly concern the calculation of the forces acting on the different materials and the numerical evaluation of the friction force; in fact, if the surfaces of the two bodies were flat, the forces acting on the silicone between the two bodies would have known directions, excluding any friction forces (Figure 10). In our case, the surfaces present different inclinations and curvatures; therefore, a function study would be needed where we could ideally identify the union of forces acting in inclined planes in addition to the different friction due to the set of directions defined in the different surfaces (Figure 11), and the calculation would be very complex [33,34].

Figure 10.

Graphic representation of the forces acting on an adhesive medium placed between two rigid bodies, in this case equally distributed.

Figure 11.

(a) Graphic representation of the model and the prosthesis in which a force persists; (b) possible acting forces and sliding of the silicone.

Other limitations of our work that are important to consider in order to correctly interpret the results to improve future prospects are reported in Table 8.

Table 8.

Limitations of this study.

5. Conclusions

The introduction of new technologies in clinical practice has radically revolutionized the field of prosthetic dentistry, bringing about improvements in the production of prosthetic products in terms of both precision and workflow. The continuous search for accuracy in prosthetic products has led researchers to study different CAD/CAM methods compared with the traditional method to improve the mechanical and clinical performance of different materials used in removable prostheses. The study we proposed, although simple and repeatable, despite the small sample and the limitations, highlights an important aspect of the contact between different materials, such as the viscous flow of silicone on the three different plates constructed with three different methods, effectively giving an indication of the choice of silicone material for a possible prosthetic relining. The results of our study suggest that there are no significant differences in the adaptability of prosthetic plates made with the traditional method, CAD/CAM by subtraction, and CAD/CAM by addition, and a poor agreement in the sample. However, the additive method may show a tendency towards greater precision in the definition of details. Further studies with a larger sample will be needed to evaluate fit and accuracy across the three construction methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, validation, S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S.; writing—review and editing, A.B. and G.C.; supervision, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study are available upon reasonable request by writing to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Davidowitz, G.; Kotick, P.G. The use of CAD/CAM in dentistry. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 55, 559–570, ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Maihemaiti, M.; Ren, L.; Maimaiti, M.; Yang, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z. A comparative study of the use of digital technology in the anterior smile experience. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ceraulo, S. Aesthetics in Removable Partial Dentures: Modification of the Proximal Plate and Retentive Lamellae in Kennedy Class II Scenarios. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazzawi, T.F. Advancements in CAD/CAM technology: Options for practical implementation. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2016, 60, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, M.; Murat, S.; Alp, G.; Zaimoglu, A. Evaluation of flexural strength and surface properties of prepolymerized CAD/CAM PMMA-based polymers used for digital 3D complete dentures. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2018, 21, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abualsaud, R.; Gad, M.M. Flexural Strength of CAD/CAM Denture Base Materials: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of In-vitro Studies. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2022, 12, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prpić, V.; Schauperl, Z.; Ćatić, A.; Dulčić, N.; Čimić, S. Comparison of Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed, CAD/CAM, and Conventional Denture Base Materials. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mert, D.; Kamnoedboon, P.; Al-Haj Husain, N.; Özcan, M.; Srinivasan, M. CAD-CAM complete denture resins: Effect of relining on the shear bond strength. J. Dent. 2023, 131, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-León, M.; Jordan, D.; Methani, M.M.; Piedra-Cascón, W.; Özcan, M.; Zandinejad, A. Influence of printing angulation on the surface roughness of additive manufactured clear silicone indices: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlHelal, A.; AlRumaih, H.S.; Kattadiyil, M.T.; Baba, N.Z.; Goodacre, C.J. Comparison of retention between maxillary milled and conventional denture bases: A clinical study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 117, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Shi, Y.F.; Xie, P.J.; Wu, J.H. Accuracy of digital complete dentures: A systematic review of in vitro studies. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, G.; Mortada, R.; Ounsi, H.; Alharbi, N.; Boulos, P.; Salameh, Z. Adaptation of Complete Denture Base Fabricated by Conventional, Milling, and 3-D Printing Techniques: An In Vitro Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fiorillo, L.; D’Amico, C.; Ronsivalle, V.; Cicciù, M.; Cervino, G. Restauro di un singolo impianto dentale: Cementato o avvitato? Una revisione sistematica di studi clinici randomizzati multifattoriali. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Brizuela, M. Dental Impression Materials. 2023 Mar 19. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marino, G.; Canton, A.; Marino, A. Moderno Trattato di Protesi Mobile Completa; Edizioni Martina, s.r.l.: Bologna, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-88-7572-118-3. [Google Scholar]

- Villias, A.; Karkazis, H.; Yannikakis, S.; Artopoulou, I.I.; Polyzois, G. Il numero di appuntamenti per la fabbricazione di protesi dentarie complete è ridotto con CAD-CAM? Una revisione della letteratura. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, H.N. Patient Satisfaction with CAD/CAM 3D-Printed Complete Dentures: A Systematic Analysis of the Clinical Studies. Healthcare 2025, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Hou, X.; Li, K.; Lu, X.; Shi, H.; Lee, E.S.; Jiang, H.B. A Review of 3D Printing in Dentistry: Technologies, Affecting Factors, and Applications. Scanning 2021, 2021, 9950131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zadrożny, Ł.; Czajkowska, M.; Tallarico, M.; Wagner, L.; Markowski, J.; Mijiritsky, E.; Cicciù, M. Modelli chirurgici protesici e preparazione del sito dell’impianto dentale: Uno studio in vitro. Protesi 2022, 4, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Radomski, K.; Lopez, D.; Liu, J.T.; Lee, J.D.; Lee, S.J. Materials and Applications of 3D Printing Technology in Dentistry: An Overview. Dent. J. 2023, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zahel, A.; Roehler, A.; Kaucher-Fernandez, P.; Spintzyk, S.; Rupp, F.; Engel, E. Conventionally and digitally fabricated removable complete dentures: Manufacturing accuracy, fracture resistance and repairability. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, M.N.M. Comparison between relining of ill-fitted maxillary complete denture versus CAD/CAM milling of new one regarding patient satisfaction, denture retention and adaptation. BMC Oral. Health 2025, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- García, E.; Jaramillo, S. Miglioramento della ritenzione delle protesi dentarie complete digitali mandibolari mediante scanner intraorale: Un caso clinico. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Curinga, M.R.; Claudino Ribeiro, A.K.; de Moraes, S.L.D.; do Egito Vasconcelos, B.C.; da Fonte Porto Carreiro, A.; Pellizzer, E.P. Mechanical properties and accuracy of removable partial denture frameworks fabricated by digital and conventional techniques: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodacre, B.J.; Goodacre, C.J.; Baba, N.Z.; Kattadiyil, M.T. Comparison of denture base adaptation between CAD-CAM and conventional fabrication techniques. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 116, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.N.; Oh, K.C.; Lee, S.J.; Han, J.S.; Yoon, H.I. Tissue surface adaptation of CAD-CAM maxillary and mandibular complete denture bases manufactured by digital light processing: A clinical study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Asper, L.; Long, J.; Lee, A.; Harrison, K.; Golebiowski, B. Ocular and visual discomfort associated with smartphones, tablets and computers: What we do and do not know. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2019, 102, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandinejad, A.; Floriani, F.; Lin, W.S.; Naimi-Akbar, A. Clinical outcomes of milled, 3D-printed, and conventional complete dentures in edentulous patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 33, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Zhou, M.L.; Min, M.; Zhang, X.F.; Qian, W.H. Evaluation of the trueness and tissue surface adaptation of digital and traditional complete denture bases. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 2024, 33, 471–475. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bessadet, M.; Drancourt, N.; El Osta, N. Time efficiency and cost analysis between digital and conventional workflows for the fabrication of fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2025, 133, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avelino, M.E.L.; Costa, R.T.F.; Vila-Nova, T.E.L.; Vasconcelos, B.C.D.E.; Pellizzer, E.P.; Moraes, S.L.D. Clinical performance and patient-related outcome measures of digitally fabricated complete dentures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 132, e1–e748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodacre, B.J.; Goodacre, C.J. Additive Manufacturing for Complete Denture Fabrication: A Narrative Review. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yin, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhong, Z. Curvature-based interaction potential between a micro/nano curved surface body and a particle on the surface of the body. J. Biol. Phys. 2016, 42, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Allegra, G.; Raos, G. Sliding friction between polymer surfaces: A molecular interpretation. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 144713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).