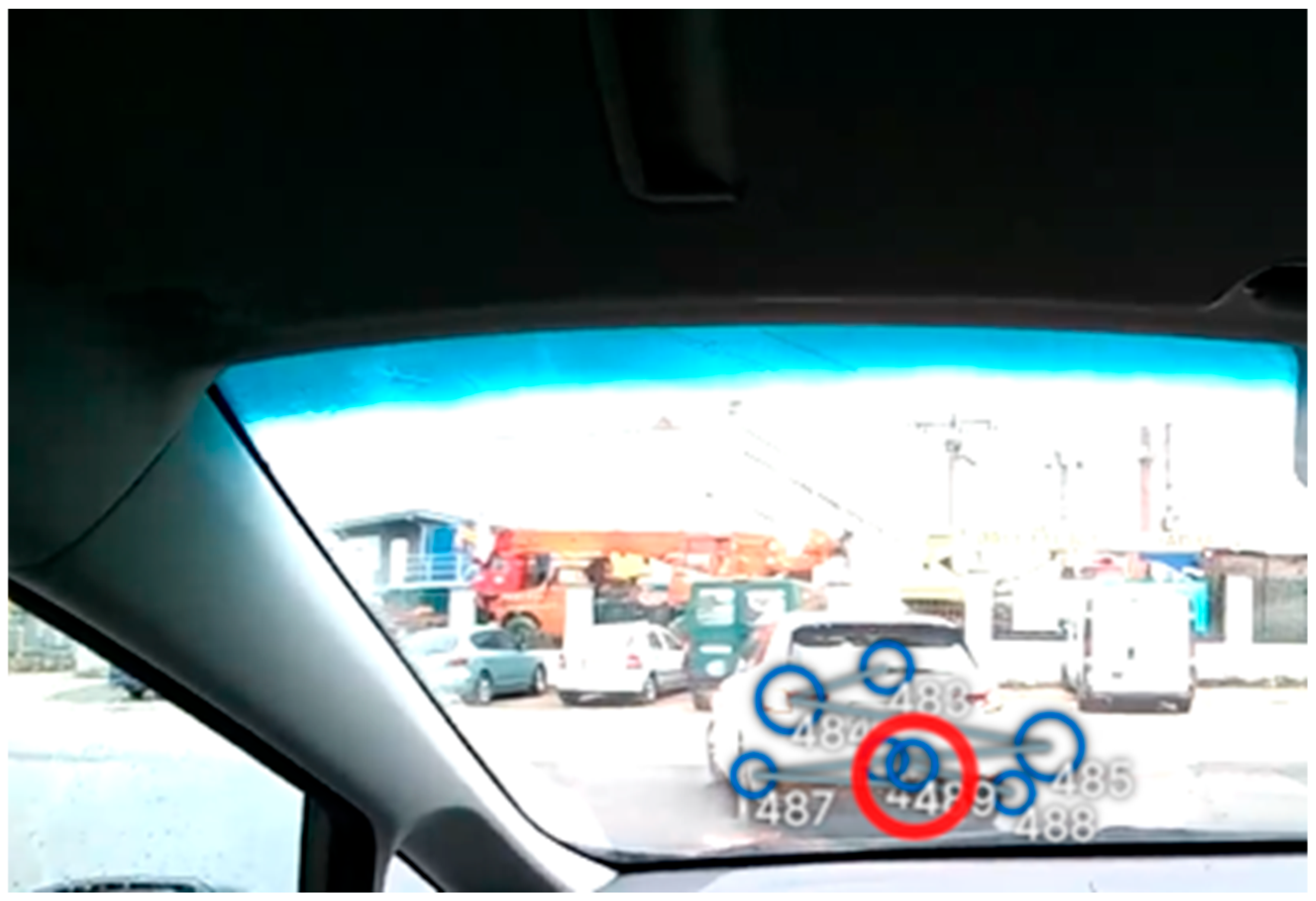

We analysed the data received from the participants and the classification of the areas to which the driver’s attention was drawn into different categories, such as road signs, road, vehicle, dashboard, pedestrian, cyclists, persons in the vehicle and checking surroundings, focusing mainly on the fixations. First, we analysed the overall distribution of attention to reveal the most and least observed elements on the road. The data were cleaned of fixations of sections at the beginning and end of the test runs.

4.1. Comparison of Driver’s Fixations

Across drivers, fixation durations exhibit considerable variability, as shown in

Table 1. Mean fixation times range from approximately 323 ms (Driver 9) to 398 ms (Driver 6), reflecting moderate inter-individual differences in gaze allocation strategies. The median fixation durations fall within a narrower interval (270–295 ms for most drivers), suggesting that typical fixation behaviour is relatively consistent, with divergence mainly driven by longer, less frequent fixations. This interpretation is supported by the asymmetry between means and medians, indicating right-skewed distributions with occasional long-duration fixations that elevate the mean.

Short fixations show remarkable uniformity across all drivers, with the minimum duration consistently around 69–70 ms, representing the lower perceptual threshold of recorded fixations. The interquartile ranges (IQRs) are also stable, with q1 values between 165 and 210 ms and q3 values between 360 and 456 ms, demonstrating comparable dispersion in the central portion of the distribution across participants.

In contrast, the maximum fixation durations differ substantially between drivers, ranging from 2467 ms (Driver 2) to 10,433 ms (Driver 1). These extended fixations likely reflect situational perceptual demands, momentary lapses in scanning behaviour, or specific environmental stimuli that require prolonged visual attention. Drivers 1, 4, 6, 7, and 8 exhibit particularly high upper extremes (>4000 ms), indicating episodes of markedly sustained gaze.

The standard deviations further highlight inter-individual variability, spanning from 234 ms (Driver 9) to 413 ms (Driver 6). Drivers with larger standard deviations also tend to have higher maximum fixation durations, consistent with distributions characterised by extreme upper-tail values.

Overall, the fixation statistics demonstrate both common underlying gaze patterns (reflected in similar medians and quartiles across drivers) and individual differences in the frequency of exceptionally long fixations. This combination suggests that while drivers share fundamental visual scanning mechanisms, personal driving style, cognitive processing, and responsiveness to environmental stimuli influence the upper range of fixation durations.

Across the dataset, each driver contributed between 2560 and 2728 fixation samples, indicating a relatively balanced distribution of observations. Mean fixation durations ranged from 323.6 ms to 398.3 ms, with substantial variation between drivers. Several drivers (e.g., Driver 1, Driver 4, Driver 6, Driver 7) exhibited extremely high maximum fixation values (3500–10,400 ms), resulting in markedly inflated standard deviations (up to 412.7 ms). These findings clearly suggest the presence of long, atypical fixations—likely artefacts arising from periods of waiting, blinks misclassified as fixations, or rare prolonged glances toward non-driving-relevant stimuli.

Drivers also differed markedly in their spread of fixation durations (

Figure 3). For example, Driver 1 exhibited the widest distribution (std = 398 ms), driven by exceptionally long fixations, while Driver 9 demonstrated the smallest spread (std = 234 ms), indicating more stable visual sampling behaviour. The consistently low minimum fixation values (≈70 ms for all drivers) reflect the lower physiological threshold of saccadic fixation. These results indicate that the raw data contain considerable inter-driver variability arising largely from extreme fixation events.

To address this issue, outliers were removed using the IQR criterion separately for each driver. The results after filtering (

Figure 4) reveal a substantially more homogeneous distribution of fixation durations. The number of retained fixations per driver remained high (2381–2511 samples), indicating that outlier removal did not compromise dataset reliability. The mean fixation durations decreased across all drivers, now falling within a narrower range of 259.4–318.6 ms, with corresponding decreases in standard deviation to approximately 107–165 ms. Importantly, the maximum fixation durations after cleaning were reduced to values between 591 and 836 ms, which are consistent with fixation behaviour reported in prior eye-tracking literature for dynamic driving environments. This confirms that the long fixation durations observed in the raw data were statistical anomalies rather than meaningful behavioural events.

The number of outliers detected per driver ranged between 163 and 224, corresponding to 6–9% of the observations. Higher counts of eliminated fixations (e.g., Drivers 1, 7, and 8) likely reflect individual differences in prolonged gaze patterns or short periods of inactivity during the test. This aligns with typical variability among novice or developing drivers, where differences in scanning strategies, attention allocation, and episodic fixation lapses can occur.

Overall, the comparison of fixation statistics with and without outliers demonstrates that the applied cleaning procedure effectively corrected for extreme values while preserving the internal structure and between-driver variability of the dataset. The resulting cleaned dataset provides a more reliable basis for subsequent inferential analyses—such as Kruskal–Wallis testing, Dunn’s post hoc comparisons, or mixed-effects modelling—without the distortion caused by rare, excessively prolonged fixations.

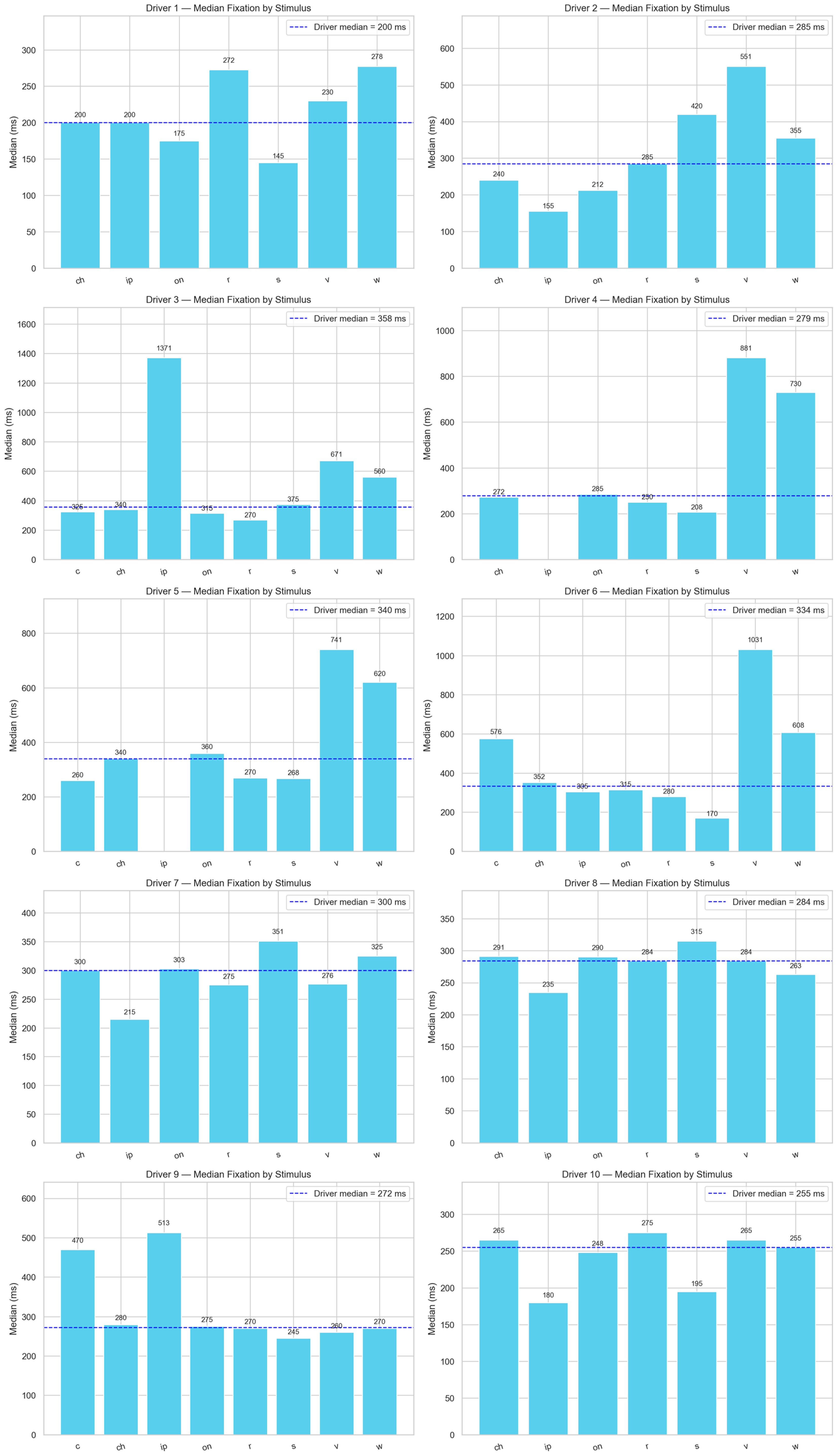

The analysis of median fixation durations across 10 drivers and multiple visual stimulus categories revealed substantial inter-individual variability and clear stimulus-dependent patterns.

Figure 5 presents the median fixation durations (in ms) for each driver–stimulus pair. Across all drivers, road-centred fixations (R) exhibited relatively stable medians (typically between 250 and 285 ms), indicating consistent attention allocation to the roadway itself. This stability aligns with the expected task demand, as road monitoring is a primary visual requirement for safe driving. In contrast, vehicle-related stimuli (V) produced markedly higher fixation medians for several drivers. Drivers 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 exhibited particularly elevated values (551 ms, 671 ms, 881 ms, 741 ms, and 1031 ms, respectively), indicating that dynamic or potentially threatening vehicle interactions demanded prolonged visual engagement.

This pattern suggests heightened cognitive load or hazard anticipation when observing moving or approaching vehicles. Fixations directed at pedestrians (W) followed a similar but less pronounced trend. Drivers 3, 4, 5, and 6 again demonstrated elevated medians (560 ms, 730.5 ms, 620.5 ms, and 608 ms), further indicating that vulnerable road users were processed with extended visual scrutiny. This is consistent with prior findings showing that objects associated with high collision risk elicit prolonged gaze durations.

Stimulus categories linked to brief situational checks—such as checking surroundings (CH) and inside-vehicle persons (IP)—showed substantial variability. Most drivers demonstrated mid-range fixation medians between 200 and 350 ms for CH stimuli; however, notable exceptions emerged. Driver 3’s median fixation for IP was exceptionally high (1371 ms), and driver 9 also showed prolonged fixations for IP (513 ms). These isolated long durations suggest sporadic complex social or cognitive processing within the cabin environment. Fixations on traffic signs (S) displayed moderate medians for most drivers (typically 170–375 ms), with one exception: Driver 2 demonstrated a much higher median fixation of 420 ms, which may indicate slower symbol recognition or increased reliance on sign information.

The C category (where present) also showed strong inter-individual differences. For example, Drivers 6 and 9 exhibited extremely high medians (576 ms and 470 ms), while Driver 5 showed much shorter fixations (260 ms), suggesting differing strategies or perceptual demands for this stimulus type. We can see that drivers 3, 4, 5, and 6 consistently produced higher fixation medians on visually demanding stimuli such as V and W. Drivers 7, 8, 9, and 10 exhibited relatively lower fixation medians across stimuli, suggesting more uniform or efficient scanning patterns. The largest individual deviations occurred in the IP and V categories, pointing to stimulus types where cognitive and perceptual processing diverge most strongly between drivers.

Taken together, these results highlight pronounced differences in visual strategies among drivers and emphasise that certain stimulus categories—particularly vehicles, pedestrians, and interior persons—provoke significantly prolonged fixation behaviour. These patterns imply that task complexity, hazard relevance, and individual driver characteristics jointly shape visual attention allocation during real-world driving. The median fixation by stimulus is depicted in

Figure 5.

4.2. Non-Parametric Analysis of Fixation Behaviour

In this study, we employed a combined analytical strategy to compare fixation behaviour across drivers for each stimulus category. The Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to account for deviations from normality and heteroscedasticity.

The dataset was overwhelmingly dominated by road fixations (R, n = 20,918), which demonstrated a stable central tendency with a median of 275 ms, confirming that road-centred visual processing is the core component of driver attention.

Categories associated with high behavioural relevance—particularly vehicles (V) and pedestrians (W)—elicited notably longer fixations. Vehicles produced a median of 300 ms, with a broad upper tail reaching 6616 ms, indicating heightened visual engagement with dynamic traffic actors. Pedestrian-related fixations showed similar behaviour (median 345 ms, max 2313 ms).

Stimuli such as checking surroundings (CH) and interior persons (IP) showed much greater variability. IP fixations ranged up to 1371 ms, suggesting occasional deep cognitive or social processing. The CH category again demonstrated the most significant extreme value in the entire dataset (10,433 ms), consistent with extended scanning episodes. Traffic signs (S) produced moderately long fixations (median = 272.5 ms, max = 1975 ms), suggesting intermittent periods of prolonged symbol recognition.

Traffic density also influenced fixation patterns. Under the lowest traffic load (Level 1), fixations had a median of 265 ms but were more variable, reaching the dataset’s maximum of 10,433 ms. Under high to moderate traffic (Levels 2 and 3), the medians remained consistent (281–265 ms), but distributions were narrower.

Interestingly, fixation durations did not increase monotonically with traffic complexity. The highest traffic levels (Levels 4 and 5) showed medians of 260–265 ms, indicating that in more demanding environments, drivers may rely on shorter but more frequent glances, consistent with rapid information sampling.

A highly significant effect of driver identity was observed (Kruskal–Wallis: H(9) = 286.06, p = 2.35 × 10−56), indicating substantial inter-individual variability in fixation duration. This confirms that drivers differ markedly in their natural visual exploration strategies, with some exhibiting consistently shorter, more frequent fixations, while others display longer, more sustained gaze patterns. Such differences reinforce the need for personalised modelling approaches, as global detection thresholds are unlikely to accommodate the diversity in baseline fixation behaviour.

The stimulus category also exerted a strong, statistically significant influence on fixation patterns (Kruskal–Wallis: H(7) = 182.64, p = 5.40 × 10−36). Fixations directed toward vehicles, pedestrians, and scanning-related visual elements were considerably longer than those associated with static or road infrastructure stimuli. These findings reflect the functional relevance and perceptual priority of dynamic or safety-critical objects within the driving scene. In contrast, static categories such as signs, surface markings, or background structures elicited shorter, more uniform fixations, consistent with their reduced cognitive and situational demands.

Finally, traffic density significantly modulated fixation durations (Kruskal–Wallis: H(4) = 76.49, p = 9.64 × 10−16). The relationship between traffic levels and gaze behaviour suggests that increasing environmental complexity requires drivers to adjust their scanning patterns, either by prolonging fixations to process critical information or by increasing scanning frequency to monitor more relevant objects. The observed differences across traffic levels confirm the sensitivity of fixation behaviour to external driving demands and highlight the need for context-aware interpretation in attention-monitoring systems.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that fixation behaviour in driving is jointly shaped by who is driving, what the driver looks at, and the level of environmental contextual complexity. This multidimensional variability underscores the importance of adaptive, personalised approaches such as Driver-Specific Gaze Profiling (DSGP), which can better account for these influences than traditional fixed-rule methods. The updated analysis confirms that a combination of driver-specific factors, stimulus category, and traffic complexity shapes fixation duration during naturalistic driving. Road-centred fixations were short and consistent, whereas safety-critical stimuli, such as vehicles and pedestrians, elicited prolonged glances. Significant inter-driver differences and skewed distributions further highlight the need to consider individual visual strategies in driver behaviour research.

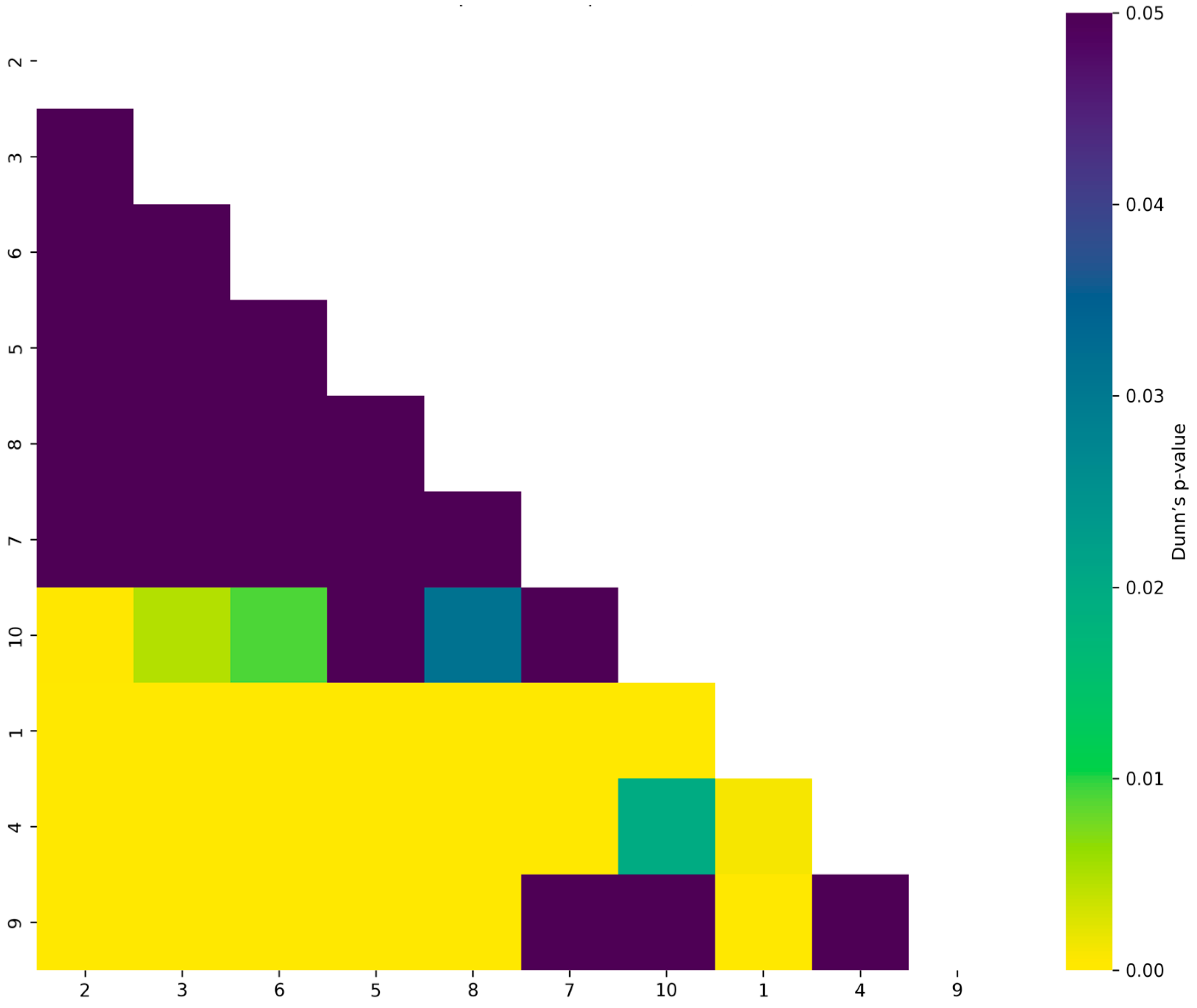

A substantial effect of driver identity on fixation duration was observed, as confirmed by the Kruskal–Wallis test (H(9) = 286.06, p = 2.35 × 10−56). This indicates that fixation length distributions varied significantly across the ten participants, demonstrating that gaze behaviour is not homogeneous even under comparable visual and driving conditions. Such substantial inter-individual variability underscores the presence of distinct visual scanning strategies and attentional tendencies among drivers.

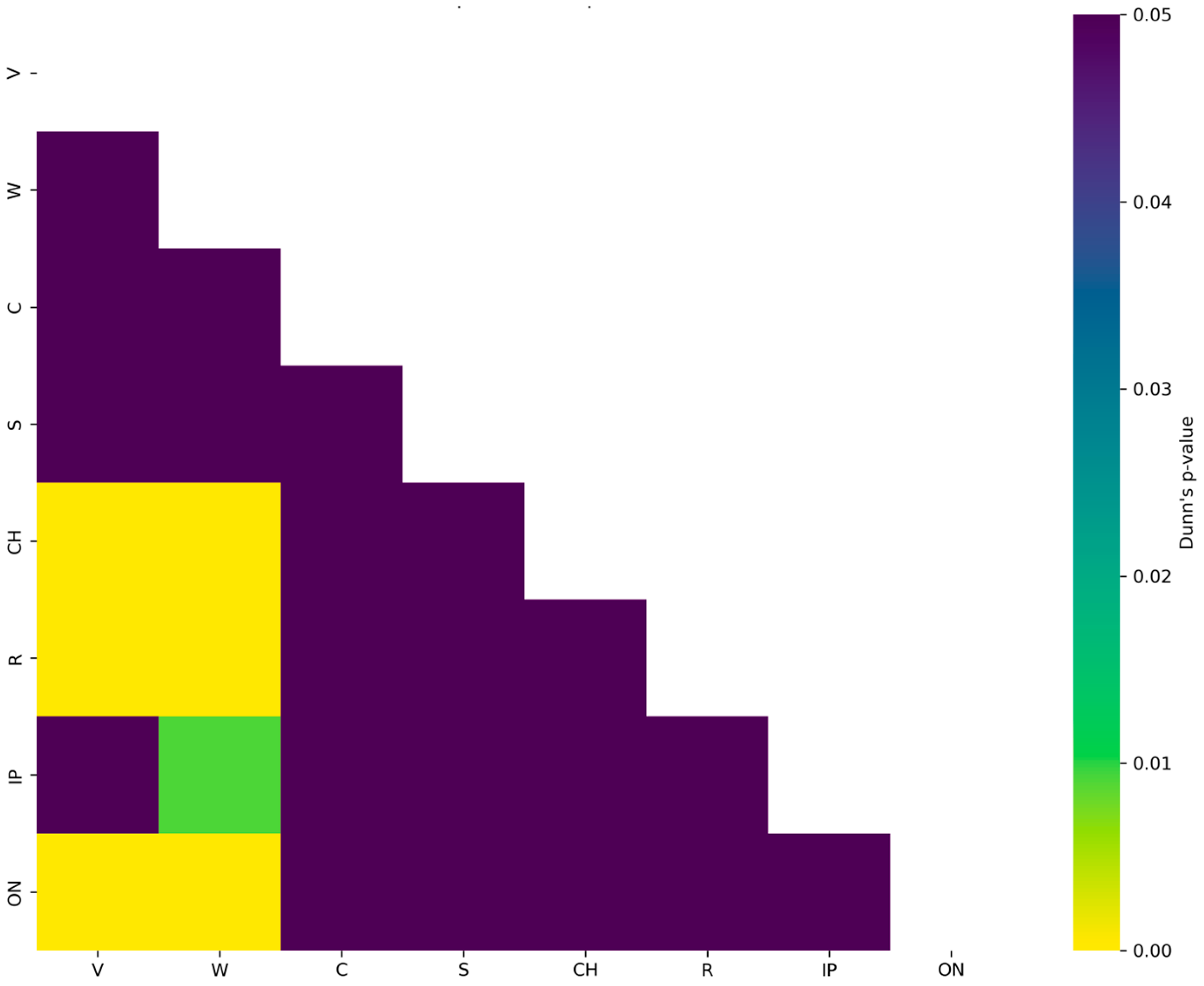

Dunn’s post hoc pairwise comparisons further revealed a structured pattern of differences. Several drivers showed statistically pronounced deviations relative to Driver 1, with extremely low adjusted

p-values (e.g., Driver 2 vs. Driver 1:

p = 6.2 × 10

−33; Driver 3 vs. Driver 1:

p = 3.06 × 10

−30; Driver 6 vs. Driver 1:

p = 3.11 × 10

−29), indicating substantially longer or shorter fixation durations. These results identify Driver 1 as a distinct behavioural reference point within the sample, with multiple participants demonstrating markedly different visual engagement patterns. Beyond contrasts with Driver 1, significant differences were also observed across other driver pairs—for instance, between Drivers 4 and 6 or Drivers 4 and 7—suggesting considerable heterogeneity even among mid-range performers. At the same time, several comparisons (e.g., Drivers 2–3, 2–5, 3–5) yielded non-significant results, indicating clusters of individuals with fixation profiles that were statistically similar. The clustered driver heatmap of Dunn’s

p-values is shown in

Figure 6.

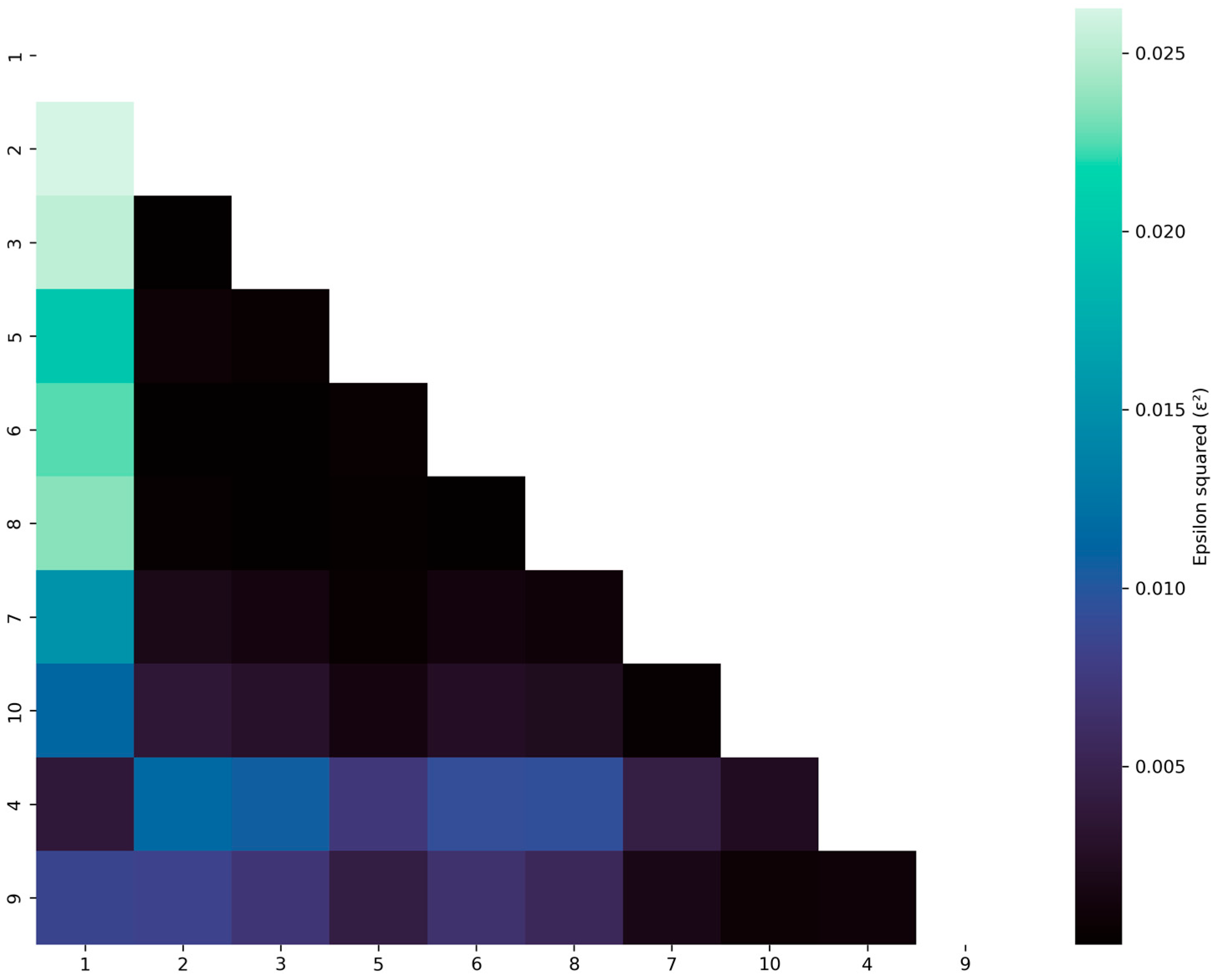

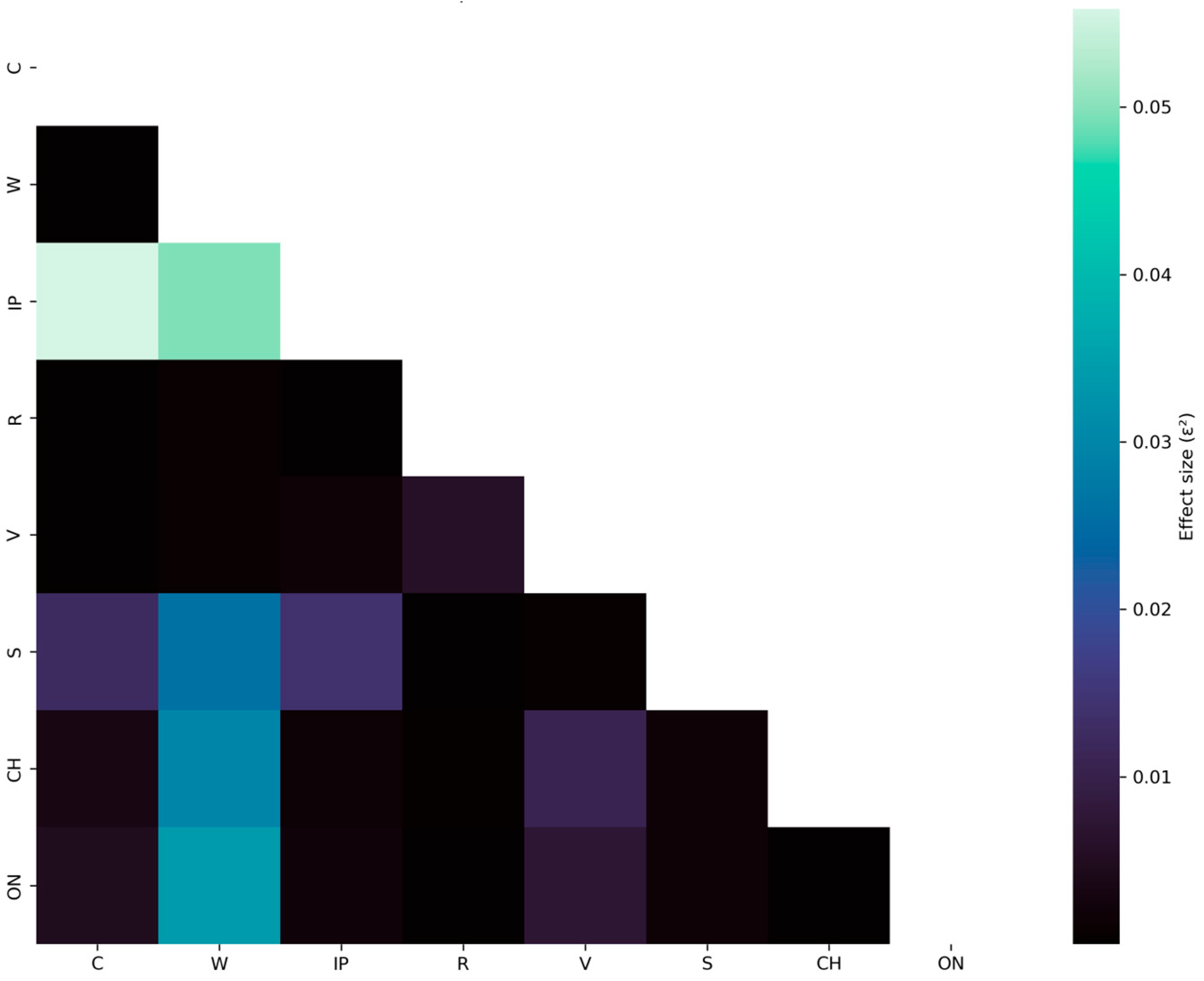

While Dunn’s test assesses whether differences are statistically significant, pairwise effect sizes (ε2) quantify their magnitude. Across all driver pairs, ε2 values ranged from 0.00 to approximately 0.026, reflecting small-to-moderate effects, which is typical for behavioural measures with large datasets.

The largest effect (

Figure 7) sizes (ε

2 ≈ 0.02–0.026) occurred between Driver 1 vs. Drivers 2, 3, 6, and 8, indicating meaningful behavioural divergence. Drivers 2, 3, 5, and 6 showed very small or near-zero effect sizes relative to one another, consistent with their non-significant

p-values. Driver 9 consistently displayed small ε

2 values (≤0.008), suggesting that although some comparisons reached significance due to the large sample size, the actual magnitude of the differences was limited. Taken together, the effect size matrix clarifies that while many differences are statistically significant, their practical magnitude varies considerably, with some contrasts representing meaningful behavioural distinctions and others reflecting minimal real-world differences.

Conducted analyses demonstrate that driver identity has a substantial and statistically significant impact on fixation duration. Post hoc comparisons reveal numerous significant differences among individual drivers. Effect size estimates indicate that the magnitude of these differences ranges from negligible to modest, with a subset of driver pairs exhibiting consistently larger divergences. Overall, the findings highlight substantial individual variability in visual attention patterns during driving. Such differences may reflect variations in experience, cognitive strategies, risk perception, or attentional control, and underscore the importance of considering driver-specific behaviour in the analysis of eye-tracking data.

To complement the omnibus statistical tests and heatmap visualisations, we extracted explicit driver clusters based on the Dunn’s post hoc comparisons and the corresponding pairwise effect-size matrix (ε

2). This analysis aimed to identify groups of drivers with fixation-duration distributions that were statistically similar and to highlight individuals whose gaze behaviour deviated markedly from the rest of the sample; see

Table 2.

Cluster identification was performed by examining (1) non-significant adjusted p-values (p_adj > 0.05), (2) small pairwise effect sizes (ε2 ≤ 0.01), and (3) structural similarity patterns observed in the clustered heatmaps. Together, these criteria revealed three distinct groups of drivers with consistent internal coherence and clear between-cluster separation.

Cluster A—Moderate, homogeneous fixation strategy (Drivers 2, 3, 5, 6).

These drivers exhibited highly similar fixation-duration profiles, characterised by stable median values and narrow dispersion. Dunn’s post hoc results indicated no significant pairwise differences among the drivers in this group, and effect sizes were uniformly low. This cluster likely reflects drivers with balanced scanning behaviour and consistent gaze allocation across different driving contexts.

Cluster B—Short, efficient fixations with low variability (Drivers 7, 8, 9, 10).

The second group was defined by notably shorter and more uniform fixation durations. Their proximity in the heatmap dendrogram and their small effect sizes indicate a shared pattern of efficient visual sampling, possibly reflecting strong procedural familiarity or rapid scene-processing strategies. These drivers showed distinct separation from Cluster A but highly consistent behaviour within the cluster.

Cluster C—Distinctive fixation profile (Driver 1).

Driver 1 formed a single-member cluster due to consistently significant contrasts with nearly all other participants, as indicated by extremely low p-values (e.g., p < 10−30) and comparatively larger effect sizes. This driver demonstrated longer, more variable fixation durations, suggesting a unique gaze strategy or higher sensitivity to environmental context. The isolation of this driver in the clustering structure highlights substantial divergence from both Clusters A and B.

Together, these clusters underscore the strong inter-individual heterogeneity captured by the DSGP framework. The presence of well-defined driver groups further supports the need for personalised attention-monitoring systems, as aggregating across drivers would mask meaningful differences in visual behaviour.

The analysis of fixation behaviour across stimulus categories revealed clear and meaningful differences in how drivers visually engage with distinct elements of the driving environment. The omnibus Kruskal–Wallis test demonstrated a robust effect of stimulus type on fixation duration, H(7) = 182.64, p = 5.40 × 10−36, highlighting that not all visual stimuli elicit the same level of attentional allocation. This finding aligns with theoretical predictions from visual attention and hazard perception literature, which posit that the salience and behavioural relevance of environmental objects modulate fixation duration.

Post hoc analyses using Dunn’s test revealed transparent, interpretable patterns in how different stimulus categories influenced fixation duration. Although several categories showed broadly comparable distributions—suggesting similar perceptual salience or cognitive processing demands—multiple stimulus comparisons exhibited statistically robust differences, highlighting the differentiated attentional priorities that drivers maintain in dynamic traffic environments.

Across all stimulus types, vehicle-related stimuli (“V”) consistently elicited the longest fixation durations. This was supported by extremely low adjusted p-values across multiple pairwise comparisons:

CH vs. V: p = 2.46 × 10−12;

ON vs. V: p = 3.84 × 10−8;

R vs. V: p = 3.11 × 10−31.

These findings indicate that drivers allocate disproportionately high levels of visual attention to other vehicles in the environment. From a behavioural standpoint, this is highly consistent with the demands of driving: surrounding vehicles are dynamic and potentially hazardous entities that require continuous monitoring for speed changes, lateral movement, braking behaviour, and collision risk. Longer fixations on vehicles, therefore, align with established models of situational awareness, in which dynamic, high-risk objects dominate attentional allocation.

Pedestrian-related stimuli (“W”) similarly elicited significantly longer fixations than many other stimulus types, including CH, IP, and ON. These results reflect the high perceptual and cognitive priority of pedestrians in road environments. Pedestrians are inherently unpredictable—capable of sudden movement, erratic behaviour, or entering the roadway—and thus require frequent or sustained visual monitoring to maintain safe control of the vehicle. The elevated fixation durations observed for pedestrians, therefore, mirror the risk-sensitive nature of driver attention.

In contrast to the pronounced differences involving vehicles and pedestrians, several stimulus categories exhibited broadly comparable fixation behaviours. Categories such as road elements (“R”), checking-surroundings (“CH”), and onboard information (“ON”) showed no statistically significant contrasts in many of their mutual comparisons:

C vs. CH: non-significant;

C vs. R: non-significant;

CH vs. ON: non-significant.

These results indicate that these lower-salience stimuli share similar levels of perceptual relevance. Their moderate and relatively uniform fixation durations suggest that drivers treat them as part of a stable baseline for general guidance and monitoring, rather than high-risk or dynamically evolving elements requiring extended visual inspection.

The analysis of fixation behaviour across stimulus categories reveals a structured and functionally meaningful hierarchy of attentional priorities during driving. Both the omnibus Kruskal–Wallis test and subsequent Dunn’s post hoc comparisons demonstrate that fixation durations are not uniformly distributed across visual stimuli; instead, they systematically vary according to the behavioural relevance, risk level, and dynamic properties of the elements being observed in the traffic environment.

Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction revealed that most stimulus pairs did not significantly differ in fixation duration. This suggests that, for many categories (e.g., C, CH, IP, ON, R, S), fixation demands were relatively similar (

Figure 8).

To complement the significance tests, we computed pairwise effect sizes (ε

2) that quantify the strength of differences in fixation durations between stimuli. Effect sizes ranged between 0.00003 and 0.0558, indicating small to moderate effects, typical for complex cognitive–perceptual tasks; see

Figure 9.

Contrasts within road-related or sign-related categories (e.g., C–R, R–S, ON–CH) produced ε2 values near zero, confirming that many stimulus types share similar visual load characteristics. Drivers consistently devoted longer fixations to vehicles than to any other stimulus, indicating a strong attentional bias toward moving or potentially hazardous road users.

Although less frequent, pedestrian stimuli elicited substantial increases in fixation, reflecting their high safety relevance. Stimulus types such as CH, IP, ON, R, and S showed no meaningful differences in fixation behaviour, suggesting comparable cognitive processing requirements. While most pairwise effects are minor, the most significant ε2 values correspond to comparisons involving vehicles and pedestrians, reinforcing their central role in attentional allocation during driving.

The most substantial effects were observed for vehicle-related (“V”) and pedestrian-related (“W”) stimuli, which elicited markedly longer fixation durations than most other categories. These categories also produced the most extreme post hoc contrasts, marked by exceptionally low adjusted p-values (e.g., CH–V: 2.46 × 10−12; ON–V: 3.84 × 10−8; R–V: 3.11 × 10−31), reflecting their high perceptual salience and safety relevance. Vehicles represent dynamic, unpredictable, and potentially hazardous traffic entities whose movement must be continuously tracked for speed changes, lateral drift, and braking events. Similarly, pedestrians introduce substantial uncertainty due to their variable motion and vulnerability, necessitating sustained visual monitoring. The consistently elongated fixations observed for these categories, therefore, reflect an adaptive allocation of cognitive resources, allowing drivers to maintain up-to-date situational awareness of high-risk elements.

Stimulus categories associated with moderate relevance—such as road features (“R”) and traffic signs (“S”)—elicited fixation durations that were shorter than those for vehicles and pedestrians, yet still indicative of meaningful processing demands. Traffic signs, in particular, require rapid interpretation and decision-making, which likely explains their slightly elevated fixation durations relative to other mid-level stimuli. These categories appear to support ongoing navigation and regulatory monitoring, tasks that engage visual attention but do not generally require sustained tracking.

In contrast, lower-attentional-demand categories—checking surroundings (“CH”), onboard displays (“ON”), internal persons (“IP”), and the rare “C” category—showed relatively homogeneous and shorter fixation durations. These stimuli are either static, low-risk, or infrequently encountered, and drivers appear to allocate only glances to them, consistent with routine scanning or incidental visual contact. Dunn’s post hoc comparisons further supported this interpretation, showing numerous non-significant contrasts among these lower-salience categories (e.g., C–CH, C–R, CH–ON), suggesting similar attentional profiles.

Collectively, the results underscore a systematic and context-sensitive structure in how drivers allocate gaze during naturalistic driving. Fixation durations increase proportionally with the behavioural importance and volatility of the stimulus, illustrating an adaptive strategy in which visual attention is preferentially directed toward elements with potential safety implications. These findings provide robust empirical support for theoretical models of gaze behaviour that emphasise risk-oriented attentional modulation, and they offer essential validation for stimulus-weighted approaches in driver-monitoring algorithms such as the Driver-Specific Gaze Profiling (DSGP) framework.

Analysis of fixation behaviour across varying traffic density levels revealed clear and statistically robust differences in drivers’ visual attention patterns. The Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a strong overall effect of traffic level on fixation duration, H(4) = 76.49, p = 9.64 × 10−16, demonstrating that fixation distributions were not homogeneous across the five traffic categories. This confirms that environmental complexity and traffic dynamics significantly modulate how drivers allocate visual attention.

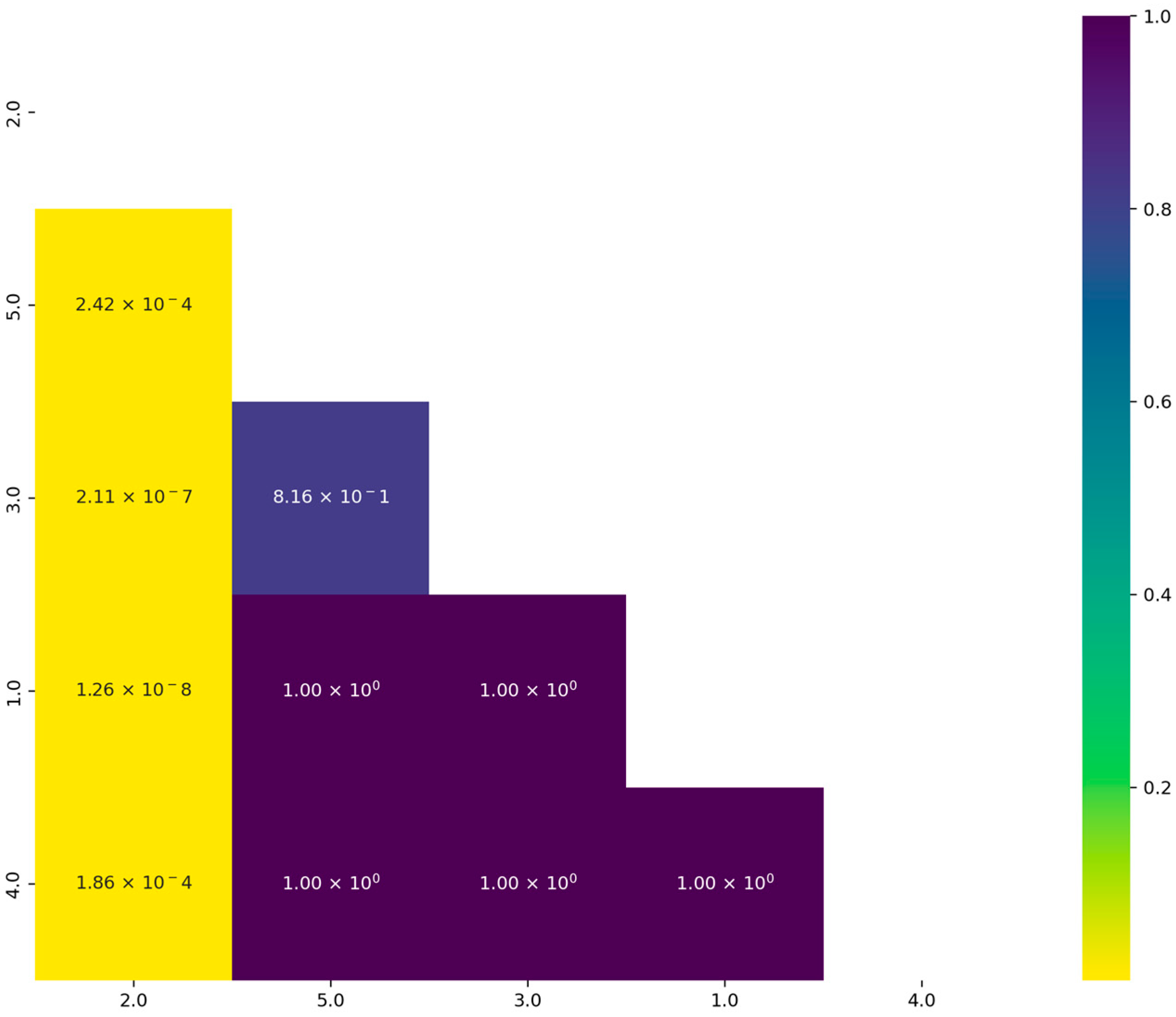

Subsequent Dunn’s post hoc comparisons pointed to the fact that the most pronounced differences consistently involved Traffic Level 2; see

Figure 10. Fixation durations at this level differed significantly from all other conditions, with extremely low adjusted

p-values observed for Level 1 vs. 2 (

p = 1.26 × 10

−8), Level 2 vs. 3 (

p = 2.11 × 10

−7), Level 2 vs. 4 (

p = 1.86 × 10

−4), and Level 2 vs. 5 (

p = 2.42 × 10

−4). By contrast, fixation durations across Levels 1, 3, 4, and 5 did not differ significantly, suggesting that these traffic conditions share a similar cognitive and perceptual demand profile.

Effect size estimates (ε2) further characterise the magnitude of these differences. Although ε2 values are generally small—consistent with the high sensitivity of large-sample nonparametric tests—they confirm the asymmetry centred on Level 2.

Positive and negative signs reflect the direction of group rank differences rather than their practical meaning; thus, the magnitudes of the absolute values are more informative. These effect sizes reinforce that Level 2 exhibited fixation patterns meaningfully different from those at other traffic densities; see

Figure 11.

The distinctiveness of Traffic Level 2 suggests that this condition induces a unique behavioural response in drivers. A plausible interpretation is that moderate traffic density introduces a level of dynamic complexity that necessitates more active scanning, anticipatory monitoring, and continuous evaluation of potential hazards. Unlike very low traffic (Level 1), where situational demands are minimal, or highly congested conditions (Levels 4–5), where movement is more predictable and constrained, moderate traffic may represent a transitional state characterised by an increased number of interacting road users, variable speeds, and more frequent decision-making moments. These factors collectively elevate visual workload and likely lead to longer or more frequent fixations.

These findings demonstrate that drivers adjust their gaze behaviour systematically in response to traffic density, with moderate traffic levels eliciting the most pronounced deviations in fixation duration. It underscores the sensitivity of gaze-based metrics to environmental complexity and highlights the importance of incorporating contextual information when interpreting driver attention patterns in naturalistic settings. We can conclude that these findings collectively suggest that prolonged fixations serve as markers of cognitive salience, typically preceded by gaze sequences directed at dynamic traffic objects, primarily other vehicles. This pattern supports the assumption that long fixations represent critical moments of situational evaluation and decision-making, when the driver processes relevant information and prepares an appropriate behavioural response in complex driving scenarios.

4.3. Testing the Driver-Specific Gaze Profiling (DSGP) Algorithm

After developing the DSGP algorithm, we first examined the resulting Attention Index (AI), defined as the standardised deviation of each fixation from the driver-specific baseline and normalised for traffic context. The AI represents the standardised deviation of each fixation from the driver-specific baseline, normalised for traffic context.

Figure 12 presents kernel density distributions of the Attention Index (AI) for all participants.

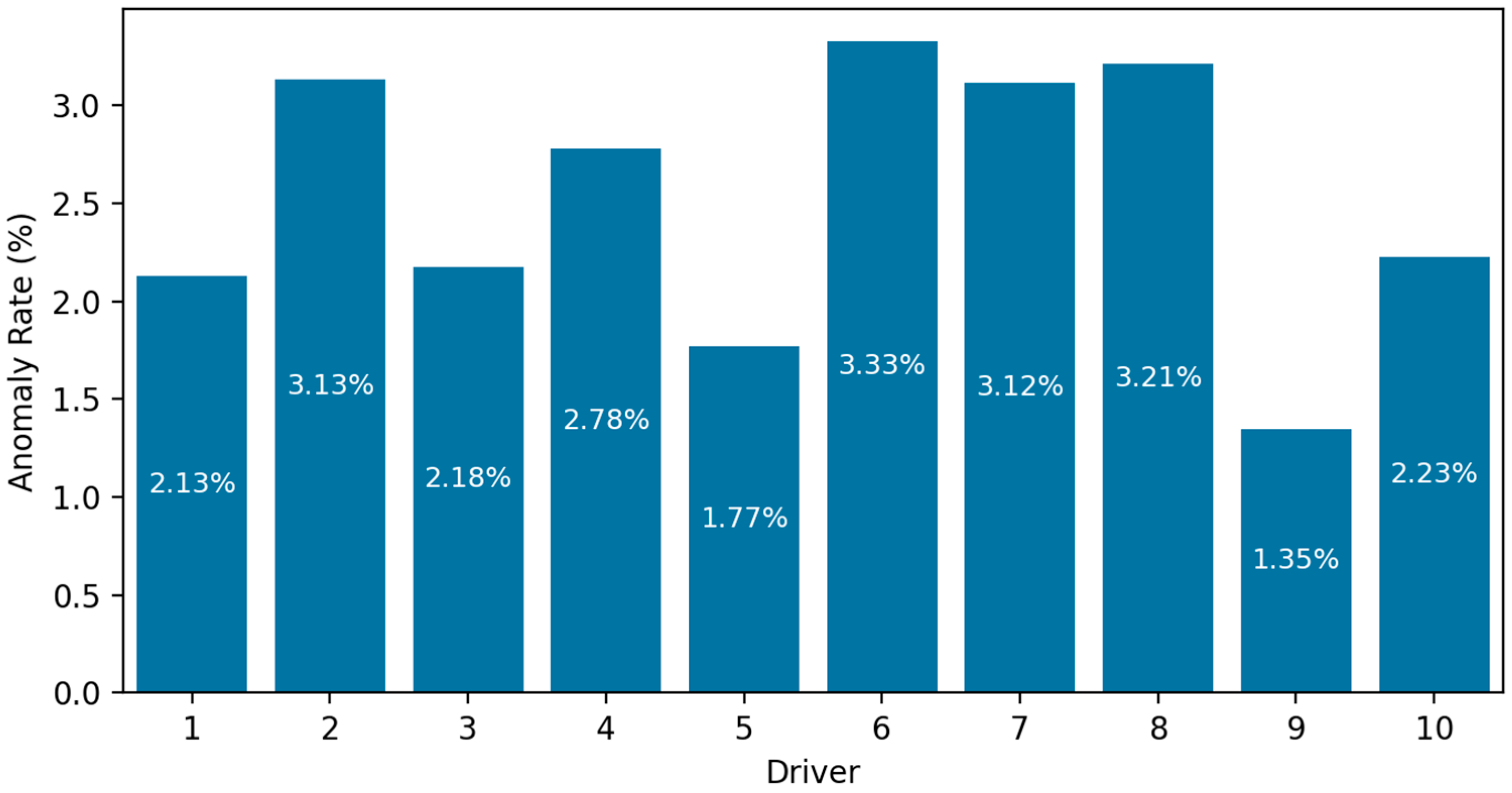

Figure 13 presents the anomaly detection analysis, based on standardised fixation duration (AI; anomaly threshold |AI| > 2.5), revealed meaningful inter-individual variability in irregular attentional behaviour across drivers. The results demonstrate a consistent yet heterogeneous distribution of anomalies across drivers, with anomaly rates ranging from 1.35% to 3.33%.

This variation indicates that although all drivers were exposed to the same set of stimuli and driving conditions, they responded differently in terms of fixation stability and attentional regulation.

Two groups can be clearly distinguished:

Higher-anomaly drivers with value ≥3%; namely, drivers 6 (3.33%), 8 (3.21%), 2 (3.13%), and 7 (3.12%). This subgroup exhibited the highest frequency of extreme fixation durations. These elevated anomaly rates may reflect:

greater visual tension or risk sensitivity;

difficulty regulating gaze behaviour under complex driving demands;

or individual differences in perceptual strategies and cognitive workload thresholds.

Lower-anomaly drivers with value ≤2% represented by drivers 9 (1.35%), 5 (1.77%), and 1/3/10 (~2.1–2.2%).

These drivers showed relatively stable fixation patterns, suggesting more consistent visual scanning strategies and fewer deviations into extreme attentional states.

The presence of anomalies reflects unusual or atypical fixation behaviour—fixations that are significantly longer or shorter than expected given the global distribution. Drivers with higher anomaly rates may have been more sensitive to dynamic hazards, more cautious, or more overloaded during the tasks. Drivers with fewer anomalies demonstrate more stable gaze regulation, potentially indicating efficient processing of the visual scene or more uniform scanning behaviour. The spread of values suggests that driver-specific traits—such as experience, risk perception, visual strategy, or cognitive load tolerance—play an important role in determining attentional irregularity during driving stimulus exposure.

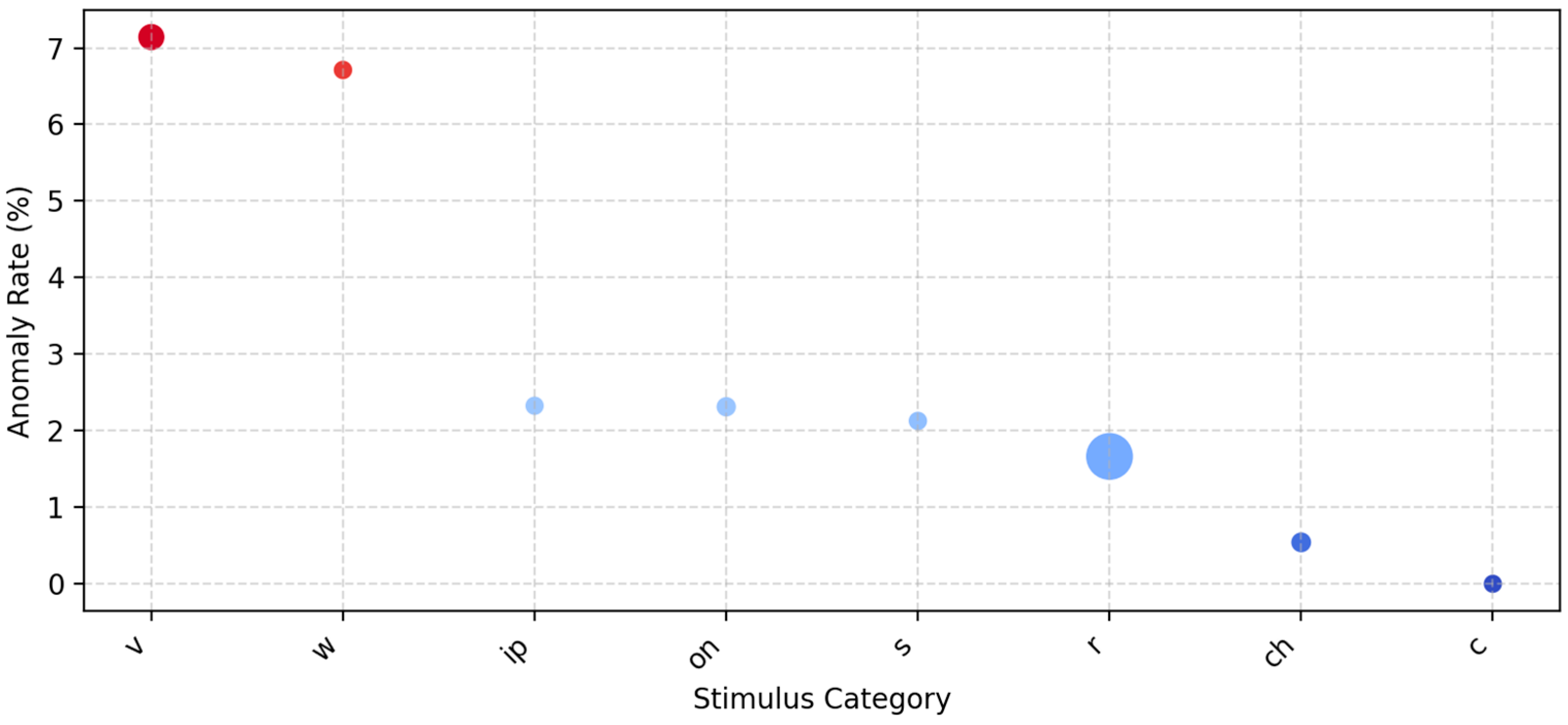

The anomaly analysis across stimulus categories (

Figure 14) revealed clear differences in how various visual elements influenced fixation irregularities during driving. The “v” (vehicles) category displayed the highest anomaly rate at 7.14%, closely followed by “w” (pedestrians) at 6.71%. These elevated rates suggest that visual stimuli involving dynamic or potentially hazardous entities—such as cars and pedestrians—are more likely to provoke atypical fixation behaviour. This pattern aligns with established models of situational awareness, where drivers allocate increased cognitive resources to moving or unpredictable road users.

Stimulus categories related to information processing, such as ip (2.33%), on (2.31%), and s (2.13%), showed moderate anomaly rates. Although these stimuli are visually important, they tend to be static and predictable, allowing drivers to process them with less abrupt shifts in attention.

Despite representing the largest share of fixations, the “r” category (road) showed only a 1.66% anomaly rate, indicating that most fixations on general driving scenery fall within normal attentional patterns. Even more notably, the “ch” (checking) category exhibited a very low anomaly rate of 0.54%, suggesting highly consistent, deliberate fixations.

These differences confirm that fixation variability and adaptive scanning patterns are highly individual, supporting the use of driver-specific thresholds rather than fixed global criteria.

Figure 15 summarises the anomalies among the drivers. A modest but meaningful inter-individual variability in fixation behaviour is depicted. Across all ten drivers, anomaly rates ranged from 1.35% to 3.33%, indicating generally stable gaze patterns during real-world driving. Driver 9 is characterised by the lowest anomaly rate (1.35%), reflecting highly consistent fixation behaviour, while Driver 6 showed the highest rate (3.33%), suggesting greater fluctuation in attentional engagement. Drivers 1, 5, and 3 demonstrated similarly low anomaly levels, whereas Drivers 2, 7, 8, and 10 formed a higher-variability group (≈3%). Overall, the results confirm discernible individual differences in gaze stability, supporting the use of driver-specific modelling approaches such as DSGP.

Conversely, static or peripheral stimuli such as the dashboard or signage exhibit lower anomaly frequencies. This pattern supports the hypothesis that fixation irregularities are influenced by both environmental salience and task relevance.

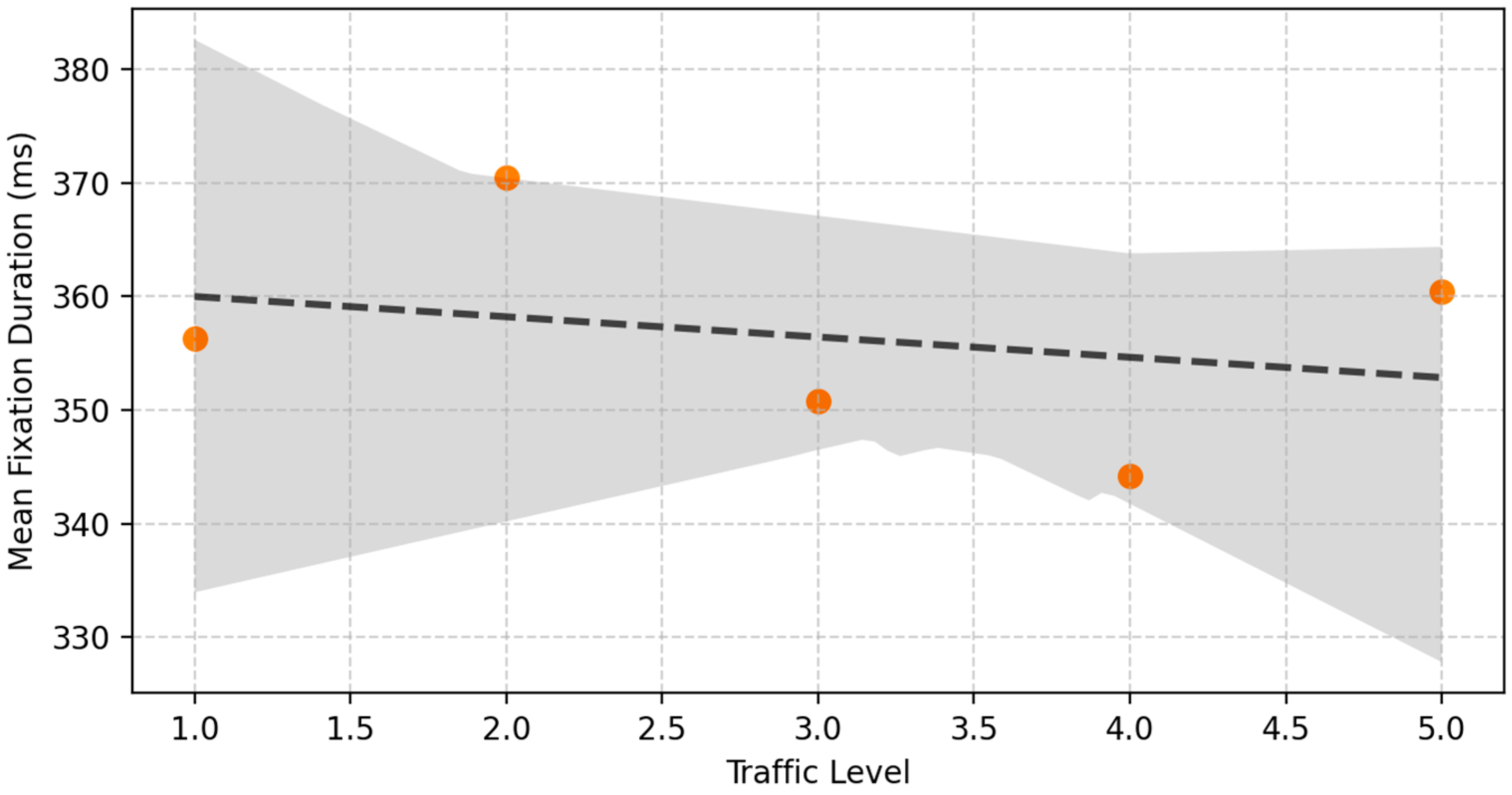

This line plot illustrates how mean fixation duration changes with traffic congestion, rated on a 1–5 scale (from smooth to congested); see

Figure 16. The dashed represents the fitted linear regression describing the relationship between traffic density and mean fixation duration. The surrounding shaded region denotes the 95% confidence interval of this estimate, reflecting the uncertainty of the regression fit and the precision with which the trend can be inferred from the data.

The fixation duration pattern across traffic levels suggests that the relationship between traffic density and attentional demand is not strictly linear. Low–Moderate Traffic (Levels 1–2): More time is spent fixating on specific objects due to structured but engaging visual scenes. The Medium Traffic (Levels 3–4) increased environmental complexity requires shorter, distributed fixations. High Congestion (Level 5) causes fixation durations to increase again as dynamic elements decrease, and attention becomes narrowly focused. This dynamic fluctuation implies that different traffic densities impose distinct cognitive demands, altering how drivers visually sample the environment.

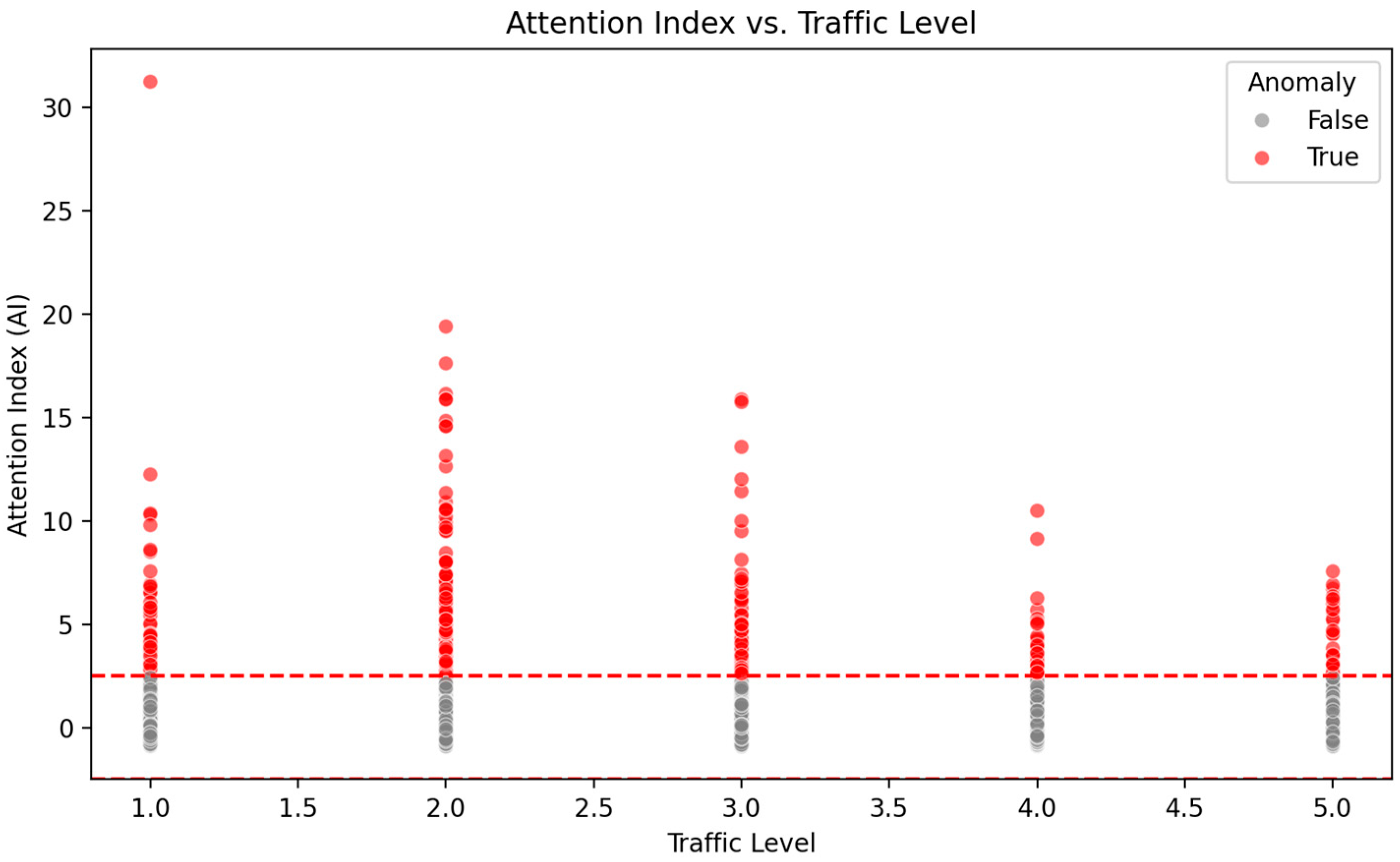

The scatter plot in

Figure 17 shows the relationship between traffic level and Attention Index values for all fixations, with anomalies highlighted in red. The red dashed lines indicate the anomaly thresholds of the Attention Index (AI) at ±2.5 standard deviations, which correspond to the bounds used by the DSGP model to classify fixations as atypical or attentionally deviant.

The analysis of the Attention Index (AI), computed as the standardised z-score of fixation duration, provides insight into how drivers’ moment-to-moment visual attention varies with traffic conditions. The dataset segment examined here contains fixation samples exclusively from Traffic Level 1, representing smooth, low-density driving. Across these observations, AI values predominantly fall within the range of −0.86 to +0.35, indicating that fixation durations remain well within the expected variability of the overall population. Significantly, none of the fixation samples exceeded the anomaly threshold of |AI| > 2.5, and therefore, no anomalies were detected.

The distribution of AI values within Traffic Level 1 demonstrates that most fixations are slightly shorter than the global mean, as evidenced by consistently negative AI values (e.g., –0.83, –0.80, –0.72). A smaller number of fixations approach the mean or slightly exceed it (e.g., AI ≈ +0.35), suggesting episodic increases in attention allocation even under low traffic load. This pattern is typical of driving environments characterised by predictable, low-complexity scenes where drivers can maintain brief, more uniform fixations without requiring abrupt shifts in attention.

The absence of detected anomalies at Traffic Level 1 suggests that smooth traffic conditions produce highly stable attentional behaviour. Drivers exhibit consistent fixation patterns with low cognitive pressure, minimal visual overload, and predictable stimulus flow. In contrast to higher traffic levels—where increased environmental complexity often leads to heightened attentional demands—Traffic Level 1 appears to facilitate homogeneous and low-variance attentional engagement, reflected in the narrow dispersion of AI values.

Collectively, these findings indicate that Traffic Level 1 imposes minimal cognitive or perceptual load, allowing drivers to maintain steady fixation durations with no evidence of excessive or insufficient visual attention. This baseline provides an important reference point for comparing attentional fluctuations at higher traffic densities, where anomalies and extreme fixation behaviours are expected to emerge more frequently due to increased task demands.

We also focused on testing the Driver-Specific Gaze Profiling (DSGP) algorithm compared with the conventional fixed-rule approach; see

Table 3.

To quantify the difference between the Driver-Specific Gaze Profiling (DSGP) algorithm and a conventional fixed-rule anomaly detection approach, we computed anomaly rates for each driver and stimulus category. Unlike the earlier theoretical scenario where both methods yielded similar average rates, the empirical results demonstrate substantial divergence between the two approaches.

Across all ten drivers, DSGP produced consistently low anomaly rates, ranging from 1.62% to 3.33%, with a mean of 2.48 ± 0.53%. In contrast, the fixed-rule method yielded markedly inflated anomaly rates between 7.23% and 14.84%, with a mean of 12.06 ± 2.71%. The average difference between methods was therefore Δ = 9.58 ± 2.36 percentage points, indicating that the fixed-rule approach over-classifies anomalies by a factor of approximately 4–6×; see

Table 4.

Driver-specific patterns further highlight this discrepancy. For example, Driver 1 exhibited a DSGP anomaly rate of 1.69%, compared with 10.67% under the fixed-rule classifier, while Driver 6 showed 2.37% versus 14.84%, respectively. Even drivers with the lowest fixed-rule anomaly burdens (e.g., Driver 9 at 7.23%) still exhibited more than three times the anomaly rate compared with DSGP. These findings suggest that much of what the fixed-rule method labels as anomalous behaviour is actually normal inter-individual variability in gaze patterns or context-driven fixation adaptation.

A similar inflation effect was observed across stimulus categories. DSGP anomaly rates remained low and stable (0–3.47%), whereas fixed-rule anomaly rates were substantially higher (9–27%). For instance, stimuli associated with dynamic roadway elements—vehicles (“v”) and pedestrians (“w”)—showed DSGP rates of 2.17% and 2.68%, respectively. However, the fixed-rule method classified 24.13% and 26.85% of these fixations as anomalous. This discrepancy reflects the fixed-rule method’s inability to accommodate the naturally longer fixations elicited by mobile hazards. DSGP, by modelling driver-specific baselines and accounting for contextual influences, avoids this misclassification bias.

The difference was especially pronounced for categories with intrinsically variable fixation demands. For example, “ip” stimuli had a DSGP anomaly rate of 2.33%, but the fixed-rule method flagged 20.93% of fixations as anomalous. Such patterns indicate that fixed thresholds are poorly suited to heterogeneous visual contexts, whereas DSGP adaptively normalises behaviour across stimulus types.