1. Introduction

High-Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes refer to reserved lanes for vehicles with a particular number of occupants depending on the regulating policies of a respective facility [

1]. These lanes have traditionally been implemented as part of transportation demand management strategies aimed at reducing congestion, promoting ridesharing, and improving person throughput during peak travel periods. High-Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes, on the other hand, are an evolution of the HOV concept that allows both high-occupancy and low-occupancy vehicles to utilize the lanes, typically through dynamic pricing or predetermined tolls [

2]. In many cases, vehicles such as HOVs, motorcycles, hybrid vehicles, transit, and emergency services are exempted from toll payments, preserving the original intent of incentivizing shared mobility while enhancing lane utilization [

2]. The conversion of HOV lanes to HOT lanes has gained widespread traction across the United States, with agencies seeking innovative ways to manage congestion more effectively, optimize facility performance, and improve cost-efficiency and political feasibility [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. States including Washington, Florida, California, Minnesota, Texas, Virginia, and Georgia have already adopted HOT lanes, many of which are retrofitted from previously underutilized HOV lanes. In Tennessee, HOV lanes were introduced in 1993 as part of a broader effort to encourage ridesharing and alleviate recurring congestion issues along major freeway corridors. These lanes, which operate during peak morning (7–9 a.m.) and evening (4–6 p.m.) periods, are delineated from general-purpose (GP) lanes by solid double white lines intended to psychologically deter unauthorized access. While initially supported under the Smart Pass program, enforcement mechanisms weakened after the federal policy underpinning the initiative lapsed [

7]. A 2016 study revealed that approximately 80% of vehicles in Tennessee’s HOV lanes were single-occupant drivers in violation of the policy, undermining the system’s efficacy [

8].

As a response to these enforcement and utilization issues, converting HOV lanes to HOT lanes is increasingly considered a potential solution. However, such a conversion cannot be guided by anecdotal evidence alone; instead, it necessitates a rigorous understanding of how traffic performance characteristics—particularly speed, flow, and density—change under different managed lane configurations. The purpose of this study was to evaluate how the foundational traffic flow relationships in HOV and HOT lane operations compare to those of standard freeway segments and theoretical models such as those described in the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) and Greenshields’ model. The HCM [

9] defines several parameters fundamental to the analysis of uninterrupted-flow facilities: volume, flow rate, speed, and density. Flow rate, typically expressed in vehicles per hour, reflects the equivalent hourly volume passing a specific roadway point under prevailing conditions. Speed, often measured in miles per hour, captures the quality of service experienced by motorists. Free-flow speed (FFS) represents the average speed under low traffic volumes when drivers are not constrained by other vehicles or roadway elements. Density, expressed in vehicles per mile, quantifies the number of vehicles occupying a given stretch of road at a specific moment. In uninterrupted-flow contexts like freeways, these parameters are interrelated through the fundamental traffic flow equations. The equations form the basis for analyzing facility capacity and service levels across a range of operational conditions.

One of the earliest and most influential models of this relationship was developed by Greenshields in 1934. His model assumes a linear relationship between speed and density, which leads to parabolic relationships between speed and flow and between flow and density [

10,

11]. According to this theory, when roadway density is zero (i.e., no vehicles present), flow is also zero. As density increases, flow rises until it reaches a peak—referred to as capacity—beyond which flow begins to decline due to increased congestion and reduced speeds. Eventually, at jam density, flow returns to zero as vehicles are effectively stationary (gridlock conditions). The simplicity and theoretical appeal of Greenshields’ model have made it a cornerstone of traffic engineering analysis, despite limitations in reflecting real-world complexities. While Greenshields’ model and HCM guidelines provide critical benchmarks for understanding traffic behavior on general freeway segments, managed lanes like HOV and HOT lanes often exhibit unique characteristics that may not align with these conventional models. Differences in vehicle mix, driver behavior, enforcement presence, entry/exit control, and pricing mechanisms all contribute to potentially distinct flow-speed-density dynamics. For instance, HOV lanes with poor enforcement may see higher densities and lower speeds due to unauthorized SOVs, whereas dynamically priced HOT lanes might maintain higher speeds and lower densities at similar flow levels by regulating demand. Furthermore, HOT lanes with limited access points tend to perform differently from those with intermediate ingress/egress options due to disruptions caused by merging and weaving maneuvers. To better understand these dynamics, this research employed a microsimulation approach using PTV VISSIM to model and analyze four distinct scenarios that reflect realistic HOV/HOT operational configurations. Microsimulation offers a robust platform to study vehicle interactions and performance metrics under controlled but realistic traffic conditions. Data extracted from these simulations were used to derive the fundamental diagrams of flow-speed-density relationships for each scenario. The study then compared these results with theoretical models, particularly Greenshields, to assess the extent to which HOV/HOT operations deviate from standard expectations. Additionally, machine learning techniques were used to identify capacity thresholds, performance tipping points, and other key metrics that inform the operational viability and design of managed lanes.

In addition to the microsimulation-based analysis, this study also employed machine learning techniques to evaluate the fundamental traffic flow relationships under HOT lane operations. Specifically, a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network architecture was implemented to model the nonlinear interactions between traffic flow, speed, and density. The MLP is a class of feedforward artificial neural networks that consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, with each neuron applying a nonlinear activation function. This structure allows the MLP to capture complex, high-dimensional relationships that are often difficult to model using traditional analytical approaches. In the context of this study, the MLP was trained on traffic data derived from the HOT lane simulations to learn and predict the flow-speed-density relationships across varying demand levels and access configurations. Once trained, the model was used to generate a fundamental data-driven diagram of HOT lane performance. These machine learning-based flow diagrams were then compared with those generated through VISSIM microsimulation and the theoretical benchmarks established by HCM. The comparison offered insights into the predictive fidelity and generalizability of each method, highlighting the potential of machine learning to complement traditional tools in capturing the nuanced behavior of managed lanes. The use of MLP models provided an additional layer of validation and robustness to the study’s findings and emphasized the growing role of artificial intelligence in transportation system modeling and evaluation. The overall goal of this paper is to derive and validate traffic flow models that are specific to HOV and HOT lane operations and to quantify the extent to which these models differ from traditional freeway segments. This work is particularly timely for jurisdictions such as the state of Tennessee, where HOV lane performance is suboptimal and conversion to HOT lanes is under consideration.

2. Literature Review

Conversion of HOV to HOT lanes has several documented impacts, including changes in safety performance, congestion redistribution on general-purpose (GP) lanes [

12], emissions levels [

13,

14], equity concerns [

15], and alterations in vehicle following characteristics and vehicle mix composition [

16]. A notable study conducted in Minnesota using the Empirical Bayes method observed a 5.3% reduction in crash frequency following the conversion of HOV lanes on I-394 to HOT lanes, demonstrating that managed lane modifications can enhance safety performance [

17]. These modifications often introduce new ingress/egress zones that alter lane-changing behavior and influence vehicle interactions, thereby modifying the facility’s flow dynamics. According to HCM, the fundamental relationship between flow rate, density, and speed remains central to capacity and performance analysis in transportation engineering [

18]. These interrelated parameters provide the foundation for determining the number of lanes needed, signal timing, intersection delay, level of service (LOS), and general operational efficiency. Over time, several theoretical and empirical models have been proposed to quantify this relationship, including Greenshields, Pipes, Van Aerde, Underwood, and Greenberg’s models [

19,

20]. Among them, the Greenshields model remains the most widely applied due to its simplicity and ease of interpretation, despite criticism regarding the assumption of a linear speed-density relationship [

20,

21]. The fundamental diagrams derived from these models are instrumental in estimating roadway segment capacity, free-flow speed, and jam density—all of which can vary significantly under HOT and HOV operational environments [

22].

The traffic flow characteristics in managed lanes can be extremely sensitive to numerous external factors such as weather conditions, lighting, construction zones, incident presence, and even traffic calming measures [

1,

23,

24,

25,

26]. For example, an Atlanta-based study showed that HOV lanes not separated by physical barriers from GP lanes suffered from speed and capacity degradation, as HOV drivers slowed down near merge areas and searched for gaps to exit downstream [

27]. In contrast, buffer- or barrier-separated managed lanes were found to be less influenced by adjacent lane friction, resulting in more stable flow characteristics. A nationwide study on managed lanes indicated that despite the deployment of access control strategies and signage, only one out of eight observed managed lanes facilities reached operational capacity [

28]. Many facilities experienced reduced speeds and capacities due to lane-changing turbulence and slower vehicles within the managed lanes. Similarly, in South Florida, research on I-95 revealed that restricting trucks from using HOV or left-most lanes led to improved travel time reliability for eligible vehicles [

29]. In addition to field-based studies, simulation-based and theoretical modeling have become key tools in understanding managed lane operations. Greenshields’ model, introduced in 1934, presents a parabolic flow-density curve with flow peaking at an intermediate density and declining as density continues to increase—a behavior consistent with real-world congestion patterns. However, Greenshields’ model does not account for non-linear driver behavior or dynamic operational controls (e.g., dynamic tolling, varying access points) typically associated with HOT lanes. To better capture the complexities of HOV and HOT lanes, recent research efforts have focused on combining simulation modeling with machine learning techniques. From this context, several critical gaps emerge in the literature. While past studies focus largely on safety outcomes, vehicle utilization patterns, and general performance trends in HOT and HOV lanes, relatively few directly address how the conversion from HOV to HOT lanes alters the fundamental traffic flow relationships. Particularly lacking are studies that assess these changes under multiple enforcement and access configurations using both classical models and advanced analytics.

This study contributes to closing that gap by analyzing the changes in flow-speed-density relationships before and after the conversion of HOV to HOT lanes under different operational scenarios. In addition to simulation via VISSIM, this research employs machine learning, particularly a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network, to model and predict traffic flow behavior under HOT lane operations. The use of MLP provides a nonlinear, data-driven alternative to traditional models, capable of learning from simulated traffic data to produce predictive flow diagrams. This hybrid approach enables a comprehensive comparison between simulation-based outcomes, machine learning-predicted traffic behavior, and the thresholds defined in HCM [

18], offering a richer understanding of managed lane performance. Furthermore, the inclusion of enforcement variability (e.g., with and without occupancy monitoring) and access control differences (e.g., intermediate vs. terminal access) in the modeled scenarios ensures the study is grounded in practical operational contexts. It builds on emerging research that suggests vehicle interactions, capacity, and throughput differ considerably between HOV and HOT applications depending on configuration and control strategies [

28]. These findings underscore the need for differentiated design and evaluation criteria for managed lanes, especially as more jurisdictions consider converting existing HOV facilities to HOT lanes to optimize infrastructure utilization. While existing literature offers valuable insights into the operational and safety impacts of managed lanes, this study distinguishes itself by systematically quantifying changes in traffic flow parameters associated with HOV to HOT lane conversions. Through the dual application of microscopic simulation and neural network-based modeling, this research provides a multidimensional perspective on how managed lanes function under varied conditions—an area that remains underexplored in the current body of knowledge. Recent advancements in traffic flow theory further contextualize the behavior of managed lanes [

30,

31]. The Congestion Boundary Approach introduces phase-transition principles that explain discontinuities between free-flow, synchronized, and congested phases—an important consideration for HOT lanes where pricing and access control modulate demand [

26,

31,

32]. Similarly, the theory of traffic flow as a simple fluid provides scaling relationships linking macroscopic density patterns to capacity breakdowns in urban corridors [

30]. In parallel, modern prediction frameworks such as Attention-based Dynamic Graph Convolutional Networks (ADGCN), XGBoost models integrated with SHAP for interpretability, and deep spatiotemporal neural architectures (e.g., LSTM, GRU, CNN-LSTM hybrids) have demonstrated improved performance for real-time traffic prediction [

32,

33]. While these approaches offer advanced capabilities, the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is well suited for modeling fundamental diagrams due to its smooth nonlinear mapping and lower data requirements, especially when forecasting equilibrium relationships rather than time-dependent traffic states [

31,

34].

3. Data and Methodology

The main objective of this paper is to determine the changes in traffic flow characteristics in an urban freeway after converting its HOV to HOT lanes. Due to its higher accuracy [

35], VISSIM 2022 software was used to run simulations and obtain traffic flow rate, speed, and density data on the I-24 Westbound, a 25-mile HOV lane segment located in Nashville, Tennessee. The VISSIM microsimulation employed the transportation demand model data that was obtained from Greater Nashville Regional Council (GNRC). The demand model data contained 24-h origin destination trips to and from zones in all Greater Nashville area. This data was filtered to obtain morning (AM) peak hour (5:30 a.m.–9 a.m.) on the I-24 WB through VISUM 2022 software. The model obtained from VISUM was transferred to VISSIM for simulation. Roadway geometry, signal timings and coordination, road signs and speed distribution were set according to visual imagery on google earth and field visit. The Geoffrey E. Harves (GEH) statistical value was used to represent the goodness of fit of a model by employing the difference between the observed and modeled field traffic flows and was utilized for model calibration [

33]. For model calibration, three validation points—Waldron, Haywood, and Old Hickory interchanges—were selected to represent upstream, mid-corridor, and downstream operating conditions along the study segment, ensuring coverage of diverse geometric and traffic environments. The VISSIM model was calibrated using Wiedemann 99 car-following parameters, realistic headway and speed distributions, and lane-changing behavior consistent with observed field conditions. The resulting GEH values at all locations were below 5, meeting widely accepted calibration standards, and confirming that the simulated volumes and speeds provide a reliable basis for subsequent analysis.

Table 1 represents the summary of the GEH values that were determined for the three specific locations where site traffic count was conducted. As shown in

Table 1, all of the GEH values obtained were less than 5, which is the maximum value required for a good freeway model.

In addition, a floating vehicle experiment along the I-24 WB was carried out to determine the average travel time and speed of vehicles during the morning peak hour (6 a.m.–9 a.m.) for the 25 miles segment. Average values of 41 min and 38 mph were obtained as travel time and speed, respectively. As well, 40 min and 38 mph were obtained as average values from the VISSIM model which were used along with the volume counts and GEH statistic to validate the model. Assumptions on vehicle composition were made based on previous research findings [

8]. About 10% of the vehicles were considered Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGV), while HOVs and SOVs were assumed to occupy 18% and 72% of the vehicles, respectively. Trucks/HGVs are restricted from utilizing the HOV lane. Speed distribution curves were set according to changes in speed limits along this freeway segment. The speed limits were set as 85th percentile while the maximum and minimum speed values were obtained as +/−15 mph to the speed limit, respectively. A duration of 60 min was used as simulation seed time, and 10,800 s (3 h) were used for simulation. A total of ten (10) simulation runs per scenario were carried out to obtain the data. This data excluded values obtained from the 60 min seeding duration. The data collected included speed, density, and volume (flow). These data were collected by utilizing the Link Segment Evaluation results in VISSIM microsimulation categorized by lanes making it possible to obtain data for the HOV, HOT and GP lanes separately.

Greenshields Model

Introduced in 1934, the Greenshields single regime model has gained popularity among all other traffic stream models due to its simplicity and average accuracy [

21]. Using aerial data, Greenshield concluded a linear relationship between speed and density and thus a parabolic relationship between speed and flow, and between flow and density.

Figure 1 shows theoretical representation of the Greenshields models.

4. Simulation Scenarios Evaluated

A total of four scenarios were evaluated in VISSIM to capture the changes in traffic flow patterns in terms of traffic flow, density, and space mean speed. The scenarios include (1) operating HOV lanes without enforcement (2) operating HOV lanes with enforcement (3) HOV converted to HOT with no intermediate access to the HOT lane and (4) HOT lanes with one intermediate access to the HOT lane. The objective is to observe the change in pattern of the traffic stream parameters and identify the impact of HOV/HOT conversion on urban freeways.

4.1. Existing HOV Lane Without Enforcement

This is the base scenario as currently the HOV segment on I-24 operates with HOV lanes on the most left lane. It can be compared to having all lanes operate as General Purpose (GP) lanes. However, there is no known effective enforcement, and thus it is faced by high levels of violation (almost 80% violation rate [

8]. However, the presence of thick white strips separating these lanes from the GP lanes creates a mental barrier to some of the SOV drivers. Under this scenario, both HOV and SOV drivers have continuous access to the HOV lane. Flow-density and speed-flow relationship graphs were plotted using Greenshields models as presented in

Figure 2. The fitted model indicates a free flow speed of 72 mph and a jam density of 195 vehicles per mile per lane (vpmpl) and a maximum flow of 1901 vehicles per hour per lane (vphpl). In addition, the speed and density at maximum flow were found to be 36 mph and 97 vpmpl, respectively.

4.2. Existing HOV Lane with Enforcement

Under this scenario, the model was set to implicate effective/absolute compliance as SOVs were restricted from utilizing the HOV lane. Only HOVs could access the HOV lane. Trucks were also restricted from using the HOV lane. However, not all HOVs would use the lane depending on their origin and destination. The HOV lane was continuous access, meaning the HOVs would access or exit at any point of their trips. The plotted graphs using Greenshields fitted model are presented in

Figure 3. The two sets of graphs present traffic stream parameter relationships for separate HOV lane and for all lanes combined. The first graphs indicate a free flow speed of 75 mph and using data for all the lanes combined indicate a free flow speed of 72 mph, a jam density of 203 vpmpl and a maximum flow of 1800 vphpl. Moreover, the speed and density at maximum flow are observed to be 36 mph and 101 vpmpl. This indicates a higher free flow speed and lower jam density on the HOV lanes if they operate under effective compliance/enforcement.

4.3. HOV Lanes Converted to HOT Lanes with Limited Access Points

Under this scenario, the existing HOV lane was converted to HOT lane and the entry and exit to and from the HOT lane are at the beginning and end of the HOT lane, respectively. The entrance and exit points were located 18 miles apart along the I-24 WB freeway from the metro Nashville area and hence characterized by higher traffic volume. The HOT segment consisted of a total of 18 miles and the toll rate was 10 cents per mile making the total toll price to be

$1.8 for SOVs deciding to use the facility while HOVs could use the HOT lane for free. The lane was continuous meaning it was neither buffered nor barrier separated from the GP lanes. Thick solid white lines separate the HOT lane from the GP lanes. However, in VISSIM, this separation acted as a barrier separation since no vehicle would exit the HOT lane at any point, except at the designated exit point. Traffic flow characteristics for the separate HOT lane show significant difference from the characteristics of all lanes combined. From the graphical presentations in

Figure 4, the free flow speed and jam density are observed to be 78 mph and 147 vpmpl respectively for HOT lane flow characteristics. In addition, the maximum flow is observed to be 1521 vphpl according to the speed-flow relationship. Meanwhile, the density and speed at maximum flow are observed to be 74 vpmpl and 39 mph. Analyzing all the lanes together, a free flow speed of 71 mph and a jam density of 190 vpmpl are observed. This indicates a lower free flow speed and higher jam density compared to the HOT lane’s operation. The maximum flow was determined to be 1652 vphpl, an 8.6% difference from the HOT lane alone. The speed and density at maximum flow were observed to be 36 mph and 95 vpmpl, respectively.

4.4. HOV Lanes Converted to HOT Lanes with Intermediate HOT Lane Access Points

Two HOT Lane access points were created for this scenario along a 22 miles segment of I-24 WB towards the Nashville metro area. The first access point was located at the beginning of HOT lane at Old Fort Parkway in Murfreesboro while the second entrance/exit at Sam Ridley Pkwy interchange (approximately 10 miles from Nashville metro). This created two merging and diverging locations along the freeway and hence having an impact on the traffic flow patterns. Like in the other scenarios, the data was filtered to obtain data for the HOT lane separate from that of the GP lanes.

Figure 5 presents the simulation and fitted Greenshield models for Speed-flow and flow-density relationships for separate HOT lane and for all lanes combined. From the HOT lane traffic stream parameter relationships, a free flow speed of 80 mph and a jam density of 214 vpmpl can be observed. The maximum flow from the speed flow relationship is observed to be 1380 vphpl with a 40-mph corresponding speed. The density at maximum flow from the flow density relationship is found to be 107 vpmpl. Analyzing all lanes in general (both HOT and GP lanes) shows a free flow speed of 73 mph and a jam density of 200 vpmpl. Moreover, the approximate maximum flow observed from both relationships shows a maximum flow of 1650 vphpl with corresponding density and speed as 100 vpmpl and 37 mph.

4.5. Simulation Results Discussion

The increase in jam density observed in the intermediate-access HOT scenario can be attributed to well-documented traffic mechanisms. Intermediate access points introduce additional merging and weaving activity, which creates localized turbulence, driver hesitation, and speed variability that propagate upstream. These disturbances effectively raise the density at which breakdown occurs. The resulting values remain consistent with ranges reported in the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) for managed lanes, indicating that the observed differences reflect expected operational behavior rather than anomalies in the simulation.

5. Machine Learning Modeling Using Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)

In addition to simulation-based modeling, this study utilized machine learning—specifically a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network—to predict traffic flow characteristics under various HOV/HOT lane configurations. The MLP model was selected due to its strong ability to model non-linear and complex relationships, handle high-dimensional datasets, and manage random noise present in real-world traffic data. Unlike traditional parametric approaches which assume a fixed functional form (e.g., linear speed-density relationship), the MLP offers a data-driven alternative that adapts to underlying patterns through iterative learning and optimization. The MLP used in this study was structured as a supervised learning algorithm consisting of an input layer, multiple hidden layers, and an output layer. The input layer received three primary traffic variables: flow, speed, and density. Each hidden layer within the MLP network contained several neurons that applied nonlinear activation functions—typically the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU)—to transform the input features and enable the model to capture complex interactions. The output layer produced predicted values for traffic flow. The training process involved feeding historical and simulated traffic data—retrieved from an Excel database—into the model. This dataset included a wide range of observations across all four modeled scenarios, representing enforcement and access configurations for both HOV and HOT lanes.

In this study, the VISSIM-generated traffic outputs (speed, density, and flow) served as the primary dataset for training the MLP model. After running the microsimulation under all four operational scenarios, the resulting link-level speed–density–flow pairs were extracted, organized, and normalized to form the input–output structure required for the neural network. This process establishes a direct integration framework in which VISSIM provides the empirical traffic states, and the MLP learns the nonlinear functional relationships embedded in those states. The model was optimized using backpropagation and gradient descent, minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) between the predicted and actual flow values. During training, the model adjusted its weights through multiple epochs to achieve convergence, ensuring that the learned relationships generalized well to new, unseen data. To enhance reproducibility, the MLP training process was fully specified. The dataset was randomly split into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing subsets. Model training used the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 64, and a maximum of 300 epochs. Early stopping with a patience of 20 epochs prevented overfitting. Hyperparameters were tuned using a grid-search procedure, testing 1–4 hidden layers, 8–128 neurons per layer, ReLU/tanh activations, and dropout rates between 0 and 0.2. Model performance was evaluated using MSE, RMSE, and R2. These refinements ensure that the machine-learning framework is transparent and fully replicable.

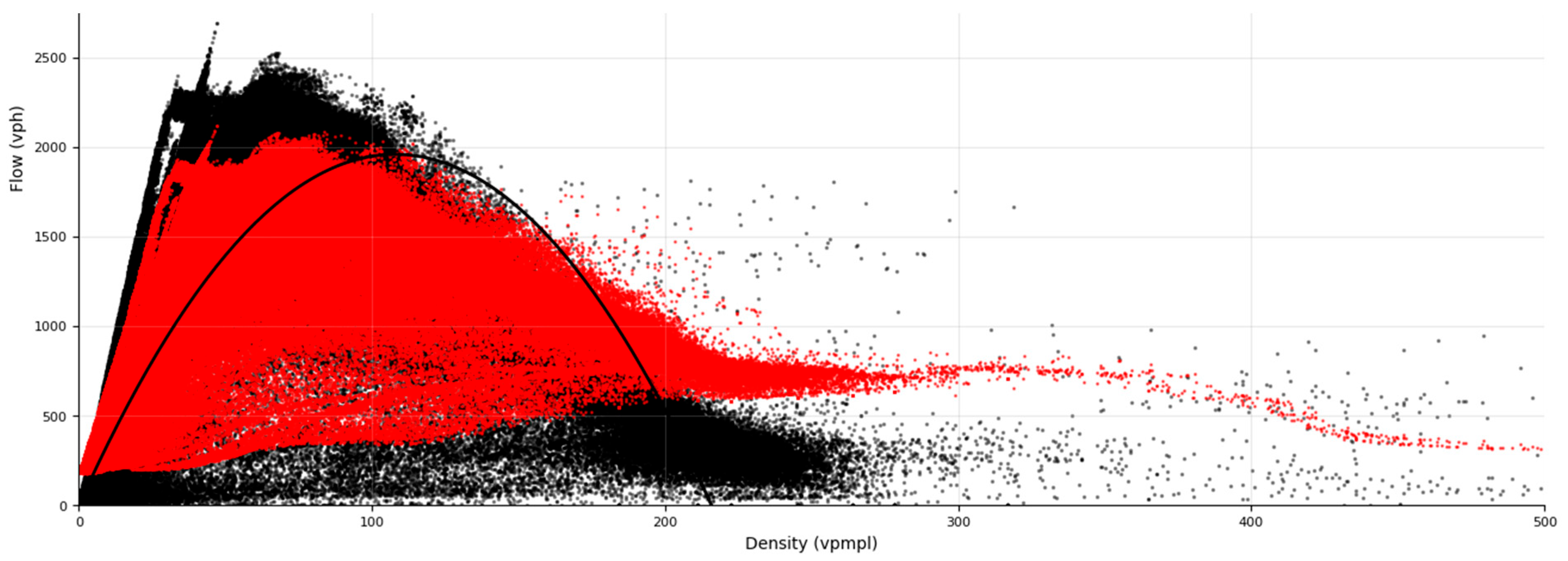

The resulting flow diagrams produced by the MLP closely resembled the theoretical form of the fundamental diagram but included subtle variations that reflect real-world traffic behavior,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The plots displayed a parabolic flow-density relationship consistent with Greenshields’ theory, with the flow increasing with density up to a critical threshold, then decreasing as congestion sets in. However, unlike the classical model, the MLP diagrams captured irregularities and variations due to lane access types, merging behaviors, and violation rates in HOV operations. Using one intermediate for HOT lane for illustration, key outputs from the MLP-based diagrams include:

Maximum flow of approximately 2000 vph

Jam density of approximately 200 vpmpl (vehicle per mile)

Density of approximately 100 vpmpl at capacity

Speed of approximately 37 mph at capacity

Figure 8 shows surface illustration on how the MLP model has learned to map the interaction between speed and density to generate flow values. It visualizes the nonlinear relationship captured by the neural network, highlighting the ridge or peak where flow is maximized—typically corresponding to the critical density. The surface shape in

Figure 8 helps validate whether the learned model aligns with established traffic flow theory (e.g., Greenshields) while accounting for complexities in managed lanes. The accompanying uncertainty surface, or model confidence plot, shows the regions in the speed-density space where the model is confident in its predictions. Lower uncertainty (i.e., high confidence) regions often align with densely populated data areas in the training set, while higher uncertainty regions suggest sparse or outlier conditions. This surface is essential for understanding where the model’s flow predictions are most reliable and where caution should be exercised in interpretation, particularly useful when extrapolating to unusual traffic scenarios like extreme congestion or very low demand in HOV/HOT lanes.

Table 2 shows all the 5 parameters analyzed: free flow speed, jam density, maximum flow, and speed and density at maximum flow. Results indicate no significant difference in performance of the HOV lanes from all lanes when the facility operates under no enforcement. This might be so since there is no effective enforcement, and thus all vehicles distribute uniformly on all available lanes. The results also indicate slight change in free flow speed among all the 4 scenarios. In addition, for all the scenarios, it can be observed from

Table 2 that the free flow speed of HOV/HOT lane is higher compared to that of all lanes combined. Jam density is observed to be 195 vpmpl on the base scenario where the HOV lane operates without enforcement. When the facility operates under effective enforcement, with only 18% being HOV, the jam density increases to 203 vpmpl, a 4% increase.

When the HOV is converted to HOT lane without intermediate entrance/exit, results indicate a slight decrease in density from 203 to 190 vpmpl. Similar to the HOV under effective enforcement scenario, the HOT lane experiences lower density compared to all lanes analyzed together under this scenario. When the facility operates with one extra intermediate HOT lane access point, the jam density increases to 200 vpmpl, a 5% increase in jam density from the former scenario. The HOT lane under this scenario has a higher jam density compared to flow when all lanes are combined. This might be a result of more vehicles accessing the HOT lane due to multiple access points and a good number of SOVs utilizing the HOT lane. The maximum flow under the base scenario is observed to be 1901 vphpl, a value observed to be the same for both HOV lane and for the whole facility. When the facility operates under effective enforcement, the maximum flow decreases to 1800 vphpl, a 5% decrease. However, the maximum flow on the HOV lane is observed to be 1065 vphpl, a much lower value compared to the whole facility. This indicates lower capacity of the HOV lane compared to the whole facility in general. When the HOV is converted to HOT lane, the maximum flow of the facility decreases from 1800 to 1652 vphpl. This implies a decrease in the number of vehicles utilizing the facility per unit hour after HOV-HOT conversion. The maximum flow of the separate HOT lane is slightly lower compared to that of the whole facility with a value of 1521 vphpl. When an intermediate HOT lane access point is added to the facility, there is no significant difference in the capacity of the facility. However, under this scenario, the maximum flow of the separate HOT lane is much lower compared to the maximum flow of the whole facility by a difference of more than 18%. The reduction in capacity might be a result of increased merging and diverging activities as vehicles enter and exit the two ingress and egress points along the freeway. The MLP-based model results in

Table 2 aligned closely with simulation outputs and theoretical expectations, effectively capturing the nonlinear relationships among traffic flow parameters. As shown in

Table 2, the MLP predicted a maximum flow of 2000 vph for all lanes and 1750 vph for the HOT lane with intermediate access—higher than corresponding VISSIM estimates. It also produced slightly higher free-flow speeds (82 mph for HOT lane) and jam densities (215 vpmpl), reinforcing the model’s sensitivity to complex lane dynamics.

To verify whether observed differences between scenarios were statistically meaningful, we performed one-way ANOVA tests on free-flow speed, jam density, and maximum flow across all four scenarios. Results indicated statistically significant differences for jam density (p < 0.001) and maximum flow (p < 0.05), while free-flow speed differences were marginal (p = 0.07). Subsequent Tukey HSD post-hoc tests showed that the HOT-with-intermediate-access scenario differed significantly from the other three in terms of congestion thresholds due to merging turbulence. We also computed 95% confidence intervals and standard deviations across the 10 simulation seeds, confirming that the directional trends were robust and not attributable to simulation noise. To improve interpretability, SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) values were computed to quantify the relative influence of speed and density on predicted flow. Results showed that density contributed more strongly to reductions in flow near congestion thresholds, while speed had a dominant effect in the uncongested regime. A global sensitivity analysis using one-at-a-time perturbations confirmed these findings, revealing nonlinear diminishing returns as density approached jam conditions. These analyses provide mechanistic insight into how the MLP replicates and extends beyond classical traffic flow theory by capturing asymmetric sensitivities that emerge in managed lanes with dynamic access behavior.

6. Conclusions

This study comprehensively evaluated traffic flow characteristics under various HOV and HOT lane operational scenarios using both microscopic simulation and machine learning techniques. A 25-mile segment of I-24 Westbound in Nashville, Tennessee was selected as the testbed corridor due to its longstanding HOV configuration and existing operational challenges, including high violation rates and underutilization. The objective was to assess how converting HOV lanes to HOT lanes under different enforcement and access configurations influences key traffic flow parameters—free-flow speed, jam density, and maximum capacity compared to standard freeway operations and Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) guidelines. Using VISSIM microsimulation, four distinct scenarios were analyzed: (1) HOV lanes without enforcement, (2) HOV lanes with effective enforcement, (3) HOT lanes with restricted access at the beginning and end, and (4) HOT lanes with one intermediate access point. The simulation outputs were fitted using Greenshields’ traffic flow model to derive speed-flow and flow-density relationships for each scenario. In parallel, a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network was trained using simulation data to model the same relationships and generate data-driven flow prediction surfaces and confidence intervals. The findings indicate that free-flow speeds remained relatively stable across scenarios, ranging between 71 and 80 mph, with HOT lanes consistently exhibiting higher free-flow speeds than both HOV and general-purpose lanes. Jam density was found to vary more significantly, with HOT lanes configured with intermediate access showing the highest jam density (214–215 vpmpl), likely due to increased merging and diverging. Conversely, HOV lanes under strict enforcement exhibited the lowest jam density (61 vpmpl), reflecting reduced vehicle volumes and uninterrupted flow. This finding can be interpreted that while free-flow speeds remain relatively consistent across operational configurations, jam density and maximum flow vary substantially depending on enforcement levels and access design. HOT lanes with intermediate access points exhibited the highest jam density due to increased merging turbulence, whereas HOV lanes with strict enforcement maintained lower densities but also lower maximum flow because of reduced eligible vehicle volumes.

In terms of capacity, the maximum flow was highest under the baseline scenario (HOV with no enforcement), reaching approximately 1901 vphpl. This likely reflects uniform lane utilization due to the lack of restrictions. However, converting HOV lanes to HOT reduced the overall maximum flow to approximately 1650 vphpl, particularly when intermediate access points were introduced, highlighting the impact of additional merging areas. The most restrictive HOT scenario (with no intermediate access) had slightly better capacity (1652 vphpl), indicating reduced turbulence but also reduced lane flexibility. The MLP neural network model demonstrated strong capability in learning and reproducing the parabolic flow-density relationships observed in theory and simulation. Key values derived from the MLP diagrams—such as a maximum flow of 2000 vph, jam density of 200–215 vpmpl, and a capacity speed of 37–42 mph—were highly consistent with simulation results and showed excellent alignment with HCM thresholds for basic freeway segments. However, these thresholds were found to be slightly higher for HOV/HOT lanes, suggesting enhanced performance potential under well-managed conditions. The MLP also provided surface visualizations of flow prediction and model confidence, helping to pinpoint areas of high reliability and uncertainty in the modeled domain. These tools underscore the value of machine learning as a complementary approach to traditional traffic modeling. In conclusion, the study finds that converting HOV lanes to HOT lanes can improve overall facility capacity, particularly in configurations with intermediate access points, though free-flow speed may improve due to pricing control and lane discipline. Simulation and machine learning results both support the premise that HOV/HOT lane performance can exceed standard GP lane assumptions, but only when managed effectively through access control and enforcement. Importantly, the alignment between MLP, VISSIM, and HCM-derived thresholds validates the use of hybrid analytical approaches in assessing managed lane systems. The findings offer transportation agencies empirical evidence to inform future conversion decisions and operational policies. Further research is encouraged by using real-world HOT lane data post-conversion to enhance validation and applicability.

While recent traffic research has increasingly relied on advanced deep learning architectures and explainable AI for short-term prediction, the approach used in this study differs by focusing on the structural characteristics of traffic flow under managed-lane operations rather than real-time forecasting. By integrating microsimulation with an analytically grounded MLP model, the method offers a practical way to uncover how operational policies—such as enforcement levels and access-point design—shape fundamental traffic relationships. This perspective provides direct implications for agencies evaluating HOV–HOT conversions, helping inform decisions on tolling strategy, lane-access configuration, and operational enforcement, while also pointing to future opportunities for expanding the framework to dynamic pricing or connected-vehicle environments.

From a policy standpoint, the findings carry important implications for agencies evaluating HOV-to-HOT conversions. First, pricing strategies should account for the sensitivity of congestion to density changes, especially near critical thresholds where HOT lane performance can degrade sharply. Second, access-point placement plays a key role in operational stability, and excessive intermediate access may introduce turbulence that reduces effective capacity. Third, maintaining robust enforcement—including automated occupancy verification—remains essential to preserving the operational benefits of managed lanes. Finally, dynamic tolling strategies informed by real-time density and speed profiles can help maintain HOT lanes within stable operating conditions, maximizing person throughput and travel-time reliability. Overall, the integration of microsimulation and machine learning provides a powerful framework for assessing managed lane performance and can assist transportation agencies in making informed design, enforcement, and pricing decisions when transitioning from HOV to HOT operations.