1. Introduction

This review paper is an expansion of my lecture

Whistler Wave Interaction Experiments at Arecibo Observatory since 1989 (Past, Ongoing, and Proposed Research). I delivered the lecture at the Arecibo Observatory’s 50th Anniversary Symposium in Puerto Rico, 27–28 October 2013 (

https://phl.upr.edu/library/labnotes/50th-anniversary-of-the-arecibo-observatory, accessed on 20 November 2025) [

1]. To honor Professor Lennard Stenflo on his 85th birthday, this review includes relevant Arecibo experiments that align with the specified technical areas, such as whistler wave injection experiments, observations of acoustic gravity waves resulting from the 9.2 Mw earthquake, and the high-power ionospheric HF heating experiments to simulate Solar Energy Harvesting via Solar Power Satellite (SPS) (also known as Space Based Solar Power (SBSP)). Among these research topics, the whistler wave experiments are directly related to Professor Stenflo’s theoretical work [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], as discussed in the author’s previous publications.

2. Background Information

The author’s research group had conducted ground-based whistler wave propagation and interactions experiments at Arecibo Observatory since 1989 until the collapse of the NSF-funded Arecibo 430 MHz radar on 1 December 2020. These experiments supported many of the author’s students from BU and MIT as they worked on thesis research and participated in the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP), in collaboration with colleagues at several universities and national laboratories.

Some background information on motivating BU–MIT controlled study of whistler wave injection experiments at Arecibo is given in Refs. [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

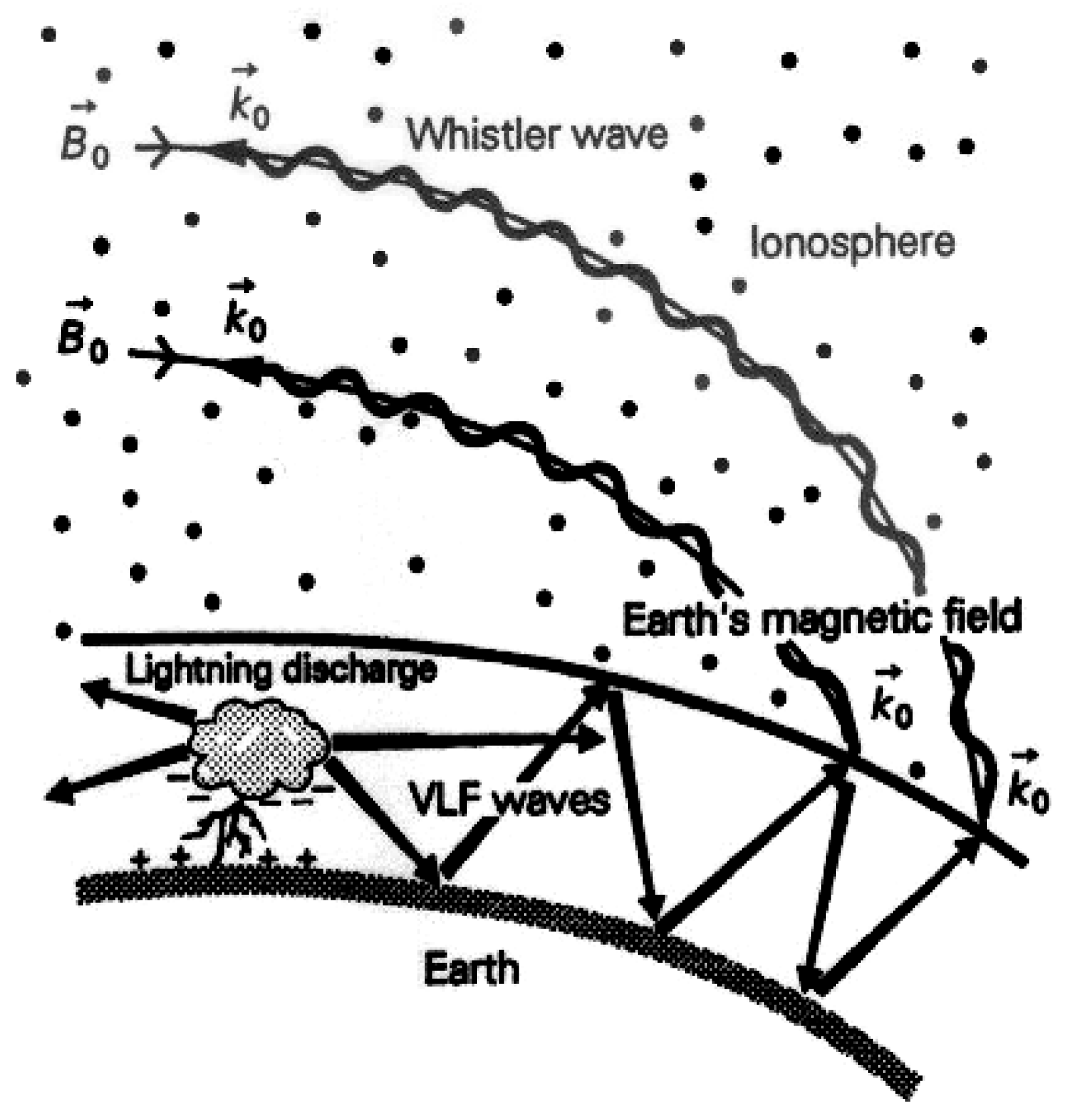

23]. As illustrated in

Figure 1 [

24], naturally occurring whistler waves can be generated by lightning with energy primarily in the frequency range of 1–10 kHz [

25]. These lightning-produced low-frequency electromagnetic waves are linearly polarized waves propagating mainly in the waveguide formed by the Earth crust and the bottomside of the ionosphere. However, they can leak into the ionosphere with a small portion (approximately 5%) [

25] of the wave energy, because the transmission coefficient is rather small. Furthermore, only one circularly polarized component of these linearly polarized waves can propagate along the Earth’s magnetic field in the form of whistler waves. These lightning generated whistler waves can propagate from one hemisphere to the other several times before they die out. The scenario of the conjugate whistler wave propagation experiments between Arecibo, Puerto Rico and Trelew, Argentina is delineated in

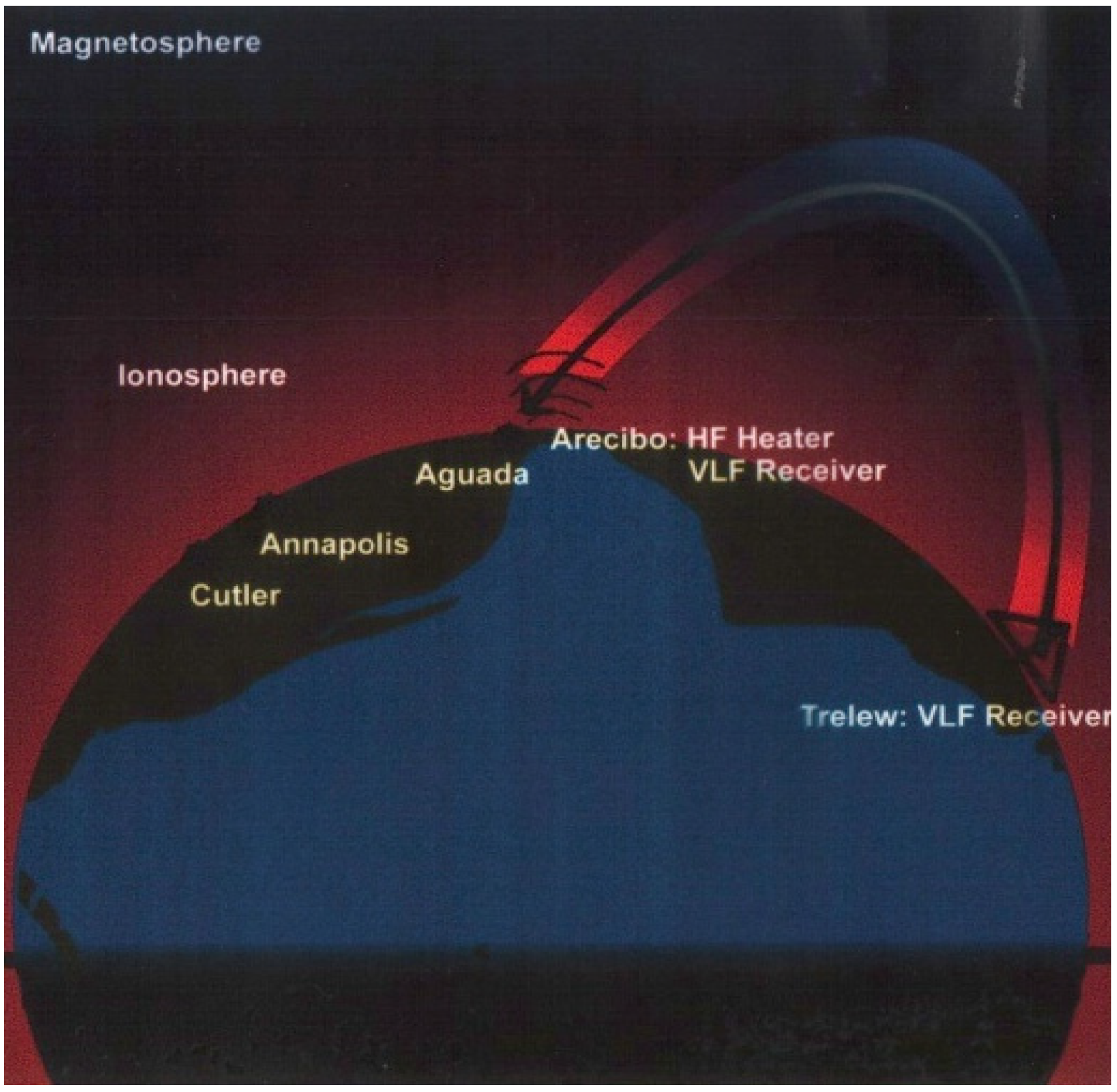

Figure 2 [

26].

It was pointed out by the author and Spencer (Si-Ping) Kuo [

27] that lightning produced VLF whistler waves are intense enough to interact with ionospheric plasmas, although the whistler wave frequencies (kHz) are three orders of magnitude lower than the ionospheric electron plasma frequency (MHz). VLF whistler waves can excite lower hybrid waves and zero-frequency (purely growing) field-aligned ionospheric modes via a four-wave interactions process/instability. These lower hybrid waves, having the same whistler wave frequency, can effectively accelerate ionospheric electrons and ions along and across the Earth’s magnetic field, respectively. These accelerated/energized electrons and ions give rise to prominent ionospheric effects over Arecibo, such as airglow and enhanced plasma/ion lines, to be elaborated on in what follows in this review.

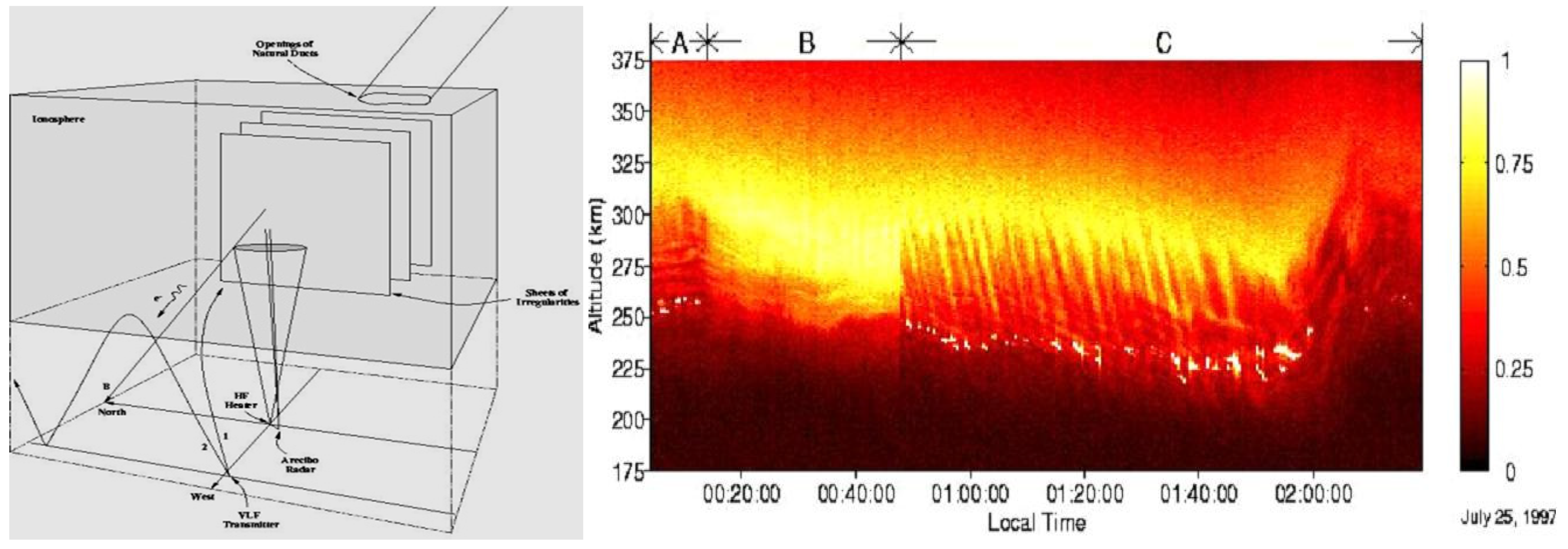

Based on the author and Kuo’s mechanism, the puzzling phenomenon reported by Ronald Woodman and Cesar LaHoz [

28] as “explosive spread F” in their experiments, using Jicamarca 50 MHz radar in Peru, can be understood as follows [

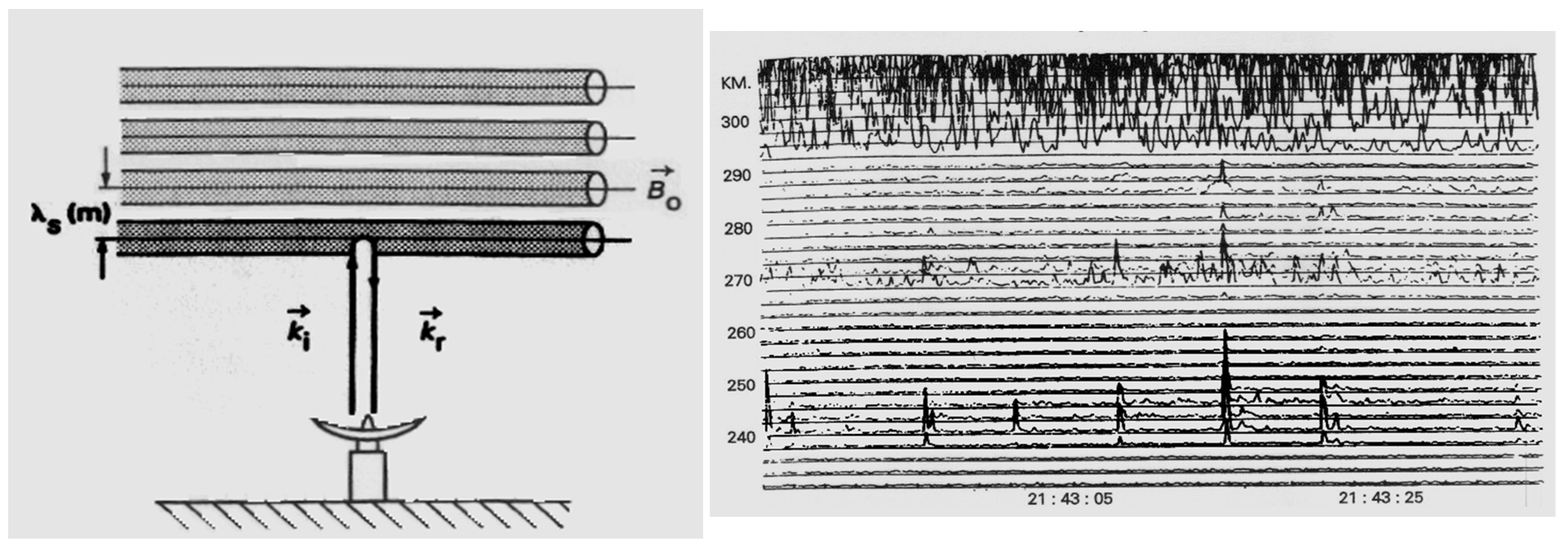

24]. The experiment setup and the radar measurements are displayed in

Figure 3. Radar signals transmitted vertically were bounced back by horizontally elongated ionospheric plasma structures, as delineated in

Figure 3(left). The corresponding radar data given in

Figure 3(right) shows two striking features: (i) a train of short-lived radar pulses separated by approximately 6 s, and (ii) radar echoes occurring at two altitudes, 240 and 270 km. These two features can be explained by the schematic diagram in

Figure 1, following the author and Kuo’s theory. That is, the lightning-induced VLF waves at the equator entered the ionosphere over Jicamarca Observatory at a comparably large angle with respect to the horizon. Thus, these waves propagated along the Earth’s magnetic field in the form of whistler waves with a large wave normal angle. This was why it took a longer time (approximately 6 s) for a round trip between two hemispheres at the equator, in comparison to a much shorter transit time for whistler propagation at higher altitudes.

Figure 1 schematically shows the entry of VLF whistler waves into the ionosphere. Because of the relatively large entering angles of whistler waves as aforementioned, one can understand why the detected radar echoes at the higher altitude (viz., 270 km) were much weaker than those at lower altitude (viz., 240 km).

In what follows in this paper, the controlled study of whistler wave propagation and interaction experiments at Arecibo Observatory are described. The presentations are organized as follows. Presented in

Section 3.1 is the whistler wave interaction experiment, performed in 1989 over Arecibo, using a satellite-borne VLF transmitter. Since then, the ground-based naval transmitter (code-named NAU) had been used at Aguadilla, Puerto Rico to conduct 28.5 kHz/40.75 kHz whistler wave injection experiments, as discussed in

Section 3.2. Addressed in

Section 4 are effects of whistler waves on space plasmas, including impacts of NAU-launched whistler waves on HF-induced Langmuir waves in

Section 4.1, energization of ionospheric plasmas in

Section 4.2 conjugate NAU-launched whistler wave propagation between Puerto Rico and Argentina in

Section 4.3 and NAU whistler wave interaction with inner radiation belts, to cause charged particle precipitation of about 390 keV in

Section 4.4.

Section 5 discusses the observations of acoustic gravity waves (also known as Traveling Ionospheric Disturbances (TIDs)) at the Arecibo Observatory, resulting from the 9.2 Mw earthquake off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, on 26 December 2004. Finally presented in

Section 6 is BU–MIT current research on solar powered microwave transmitting systems motivated by the under-dense HF heating experiments at Arecibo Observatory, to simulate Solar Energy Harvesting via SPS/SBSP.

3. Arecibo Experiments

3.1. US–USSR Active Space Plasma Experiment in 1989 at Arecibo

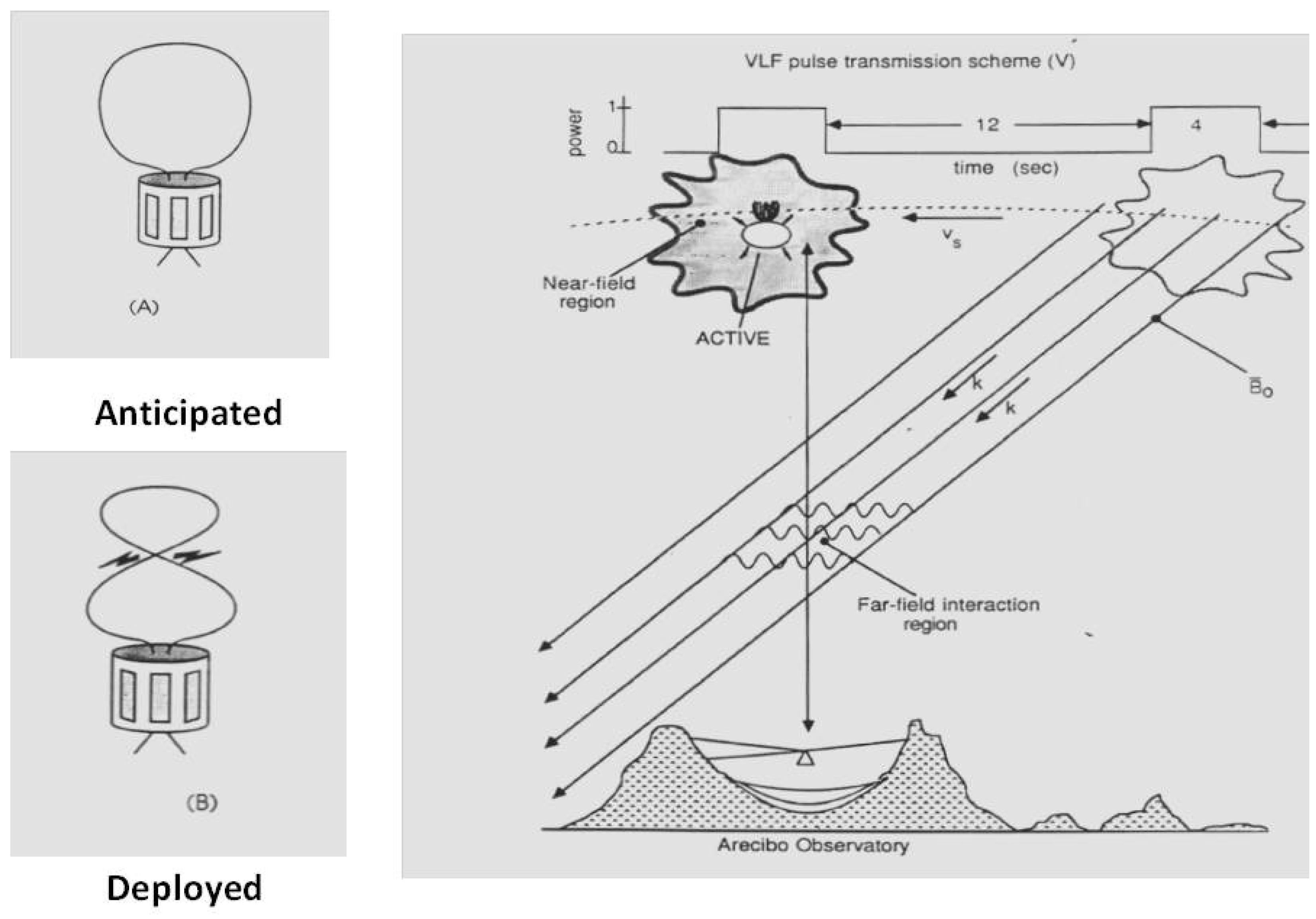

Under the US–USSR Active Space Plasma Program, the author’s group conducted VLF wave interaction experiments at Arecibo on 24 December 1989 around 6:00 PM, using the USSR Active Satellite-borne transmitter operating at the frequency and power of 10 kHz and 10 kW. The scenario delineated in

Figure 4 shows that 10 kHz whistler waves were launched from the loop antenna carried by the USSR Active Satellite [

29]. It was expected that these whistler waves propagating along the geomagnetic field interacts with ionospheric plasmas above Arecibo. The 430 MHz radio signal was subsequently transmitted from the Arecibo radar to diagnose the nonlinear effects as predicted by the author and Kuo [

27].

However, the experiment did not produce non-linear effects as expected, because the loop antenna was not deployed correctly as illustrated in

Figure 4(left): the anticipated configuration of the antenna is given in

Figure 4(left, A) for comparison with the deployed one in

Figure 4(left, B). The deployed antenna twisted into a “Figure 8”, drastically increasing the antenna impedance and reducing the radiating power. Hence, the Arecibo radar only detected the Active Satellite passing over and mapping out the antenna pattern. While there were no satellite-borne VLF transmitters for experiments after 1989, the ground-based NAU at Aguadilla, Puerto Rico has provided a reliable source for our ground-based whistler wave propagation and interaction experiments at Arecibo Observatory.

3.2. Ground-Based VLF Whistler Injection Experiments with Arecibo HF Heater

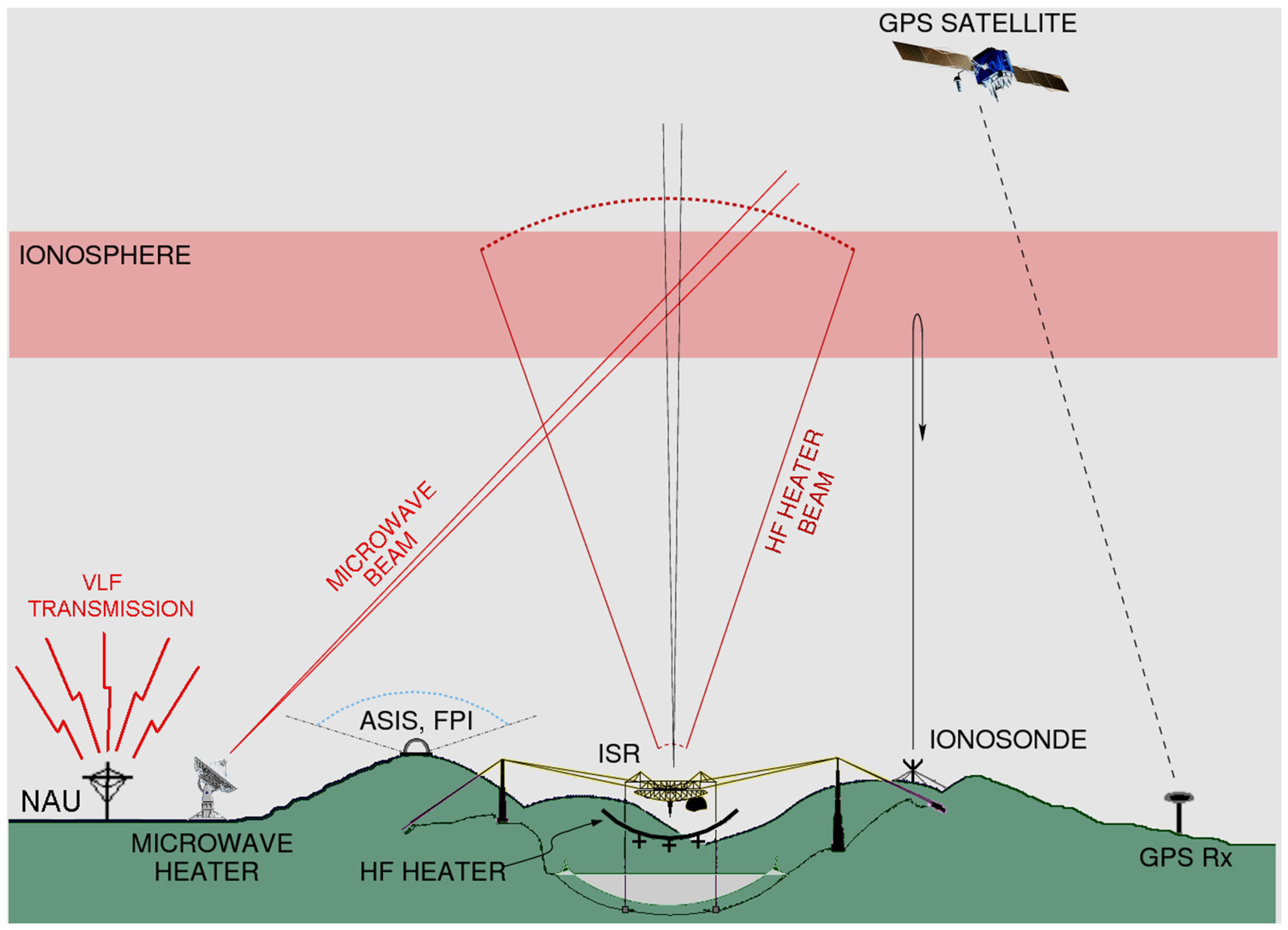

The aforementioned Naval transmitter in Puerto Rico radiated at the frequency of 28.5 kHz/40.75 kHz (earlier/later) and power of 100 kW. The coupling of the NAU launched whistler waves with the ionosphere can be explained in terms of

Figure 5, wherein several key radio and optical diagnostic instruments used in the experiments are shown, viz., Arecibo radar, an ionosonde known as CADI, a Fabry-Perot interferometer, and BU-MIT All-Sky Imaging System (ASIS). The NAU transmitted VLF waves propagate primarily within the waveguide formed by the Earth crust and the bottom side of the ionosphere. These waves may enter the ionosphere with a small transmission coefficient. Furthermore, only one circularly polarized component of the linearly polarized VLF waves can propagate in the ionosphere as whistler waves. It is estimated that about 7.5% of the transmitted wave energy can be coupled into the ionosphere, being able to interact effectively with ionospheric plasmas [

30] and inner radiation belts [

22,

23,

31].

During 1990–1998 BU–MIT Arecibo experiments were conducted under the combined operation of the VLF transmitter (at 28.5 kHz) and the HF heater (at 8.175 MHz, 7.4 MHz, 5.1 MHz, and 3.175 MHz). The experiment results of relevance to whistler wave propagation and interactions with space plasmas are examined in four categories, separately, as described in

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3 and

Section 4.4.

As reported in Ref. [

32], HF heater waves can generate parallel-plate waveguides in the ionosphere. Under the ExB plasma drift, these waveguides, detected by the Arecibo radar, were seen as slanted stripes in the RTI (range-time-intensity) plots displayed in

Figure 6. These parallel–plate waveguides can enhance the coupling of NAU-launched VLF waves with the ionosphere, and guide them to propagate along the geomagnetic field as ducted whistler waves.

4. Effects of NAU-Launched VLF Whistler Waves on Space Plasmas

4.1. Effects of NAU-Launched Whistler Waves on HF-Induced Langmuir Waves

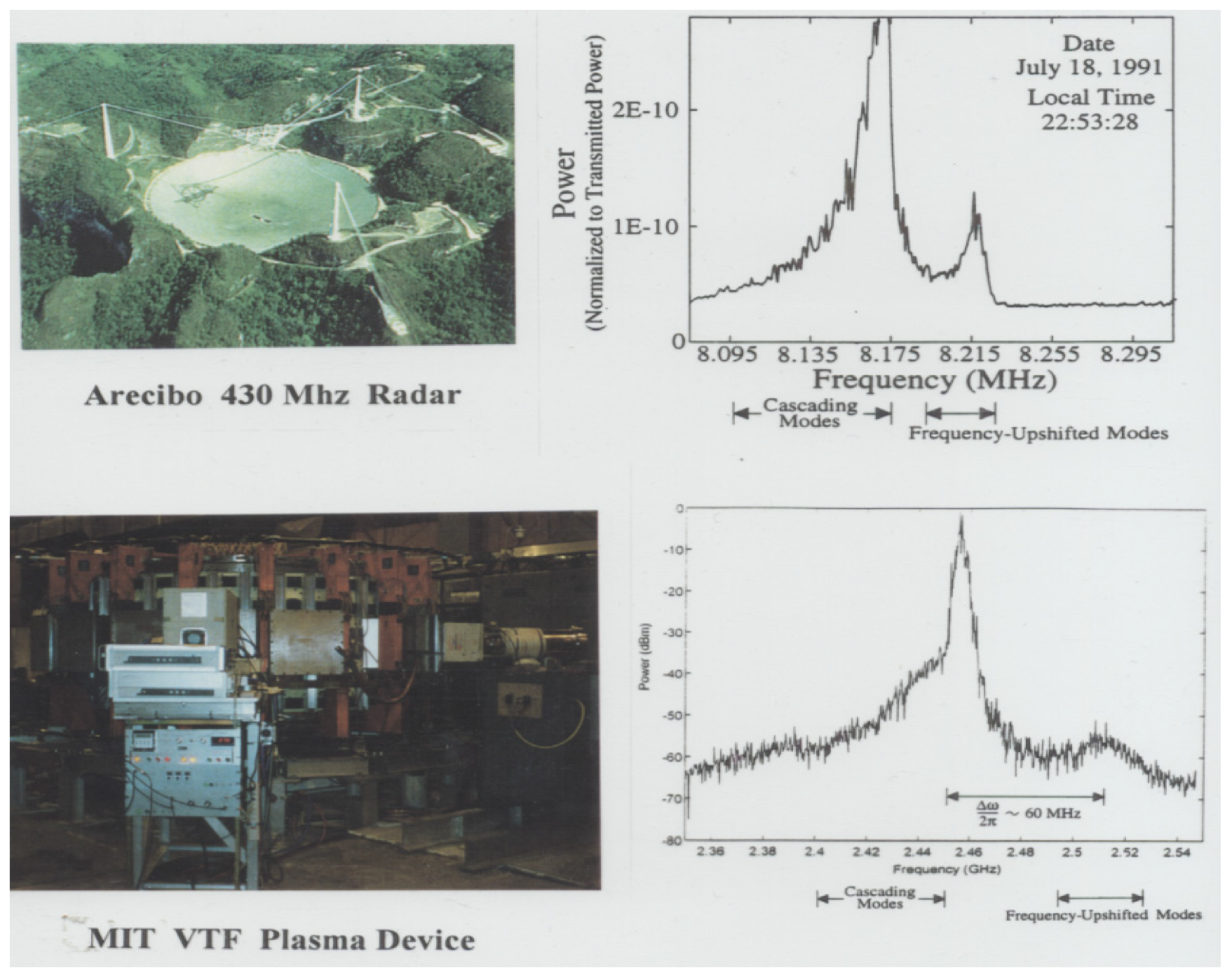

One prominent effect caused by whistler waves on the HF wave-modified ionosphere is the whistler wave interaction with HF heater wave-induced Langmuir waves, yielding frequency-upshifted plasma lines. Displayed in

Figure 7 (upper) is a sample of data recorded by Arecibo radar in BU–MIT 1991 experiments; the bottom panel of

Figure 7 (lower) presents the reproduced result in BU–MIT laboratory simulation experiments at MIT using the VTF (Versatile Toroidal Facility) plasma device [

33]. In brief, Langmuir waves are excited by O-mode HF heater waves along the geomagnetic field via the parametric decay instability. These Langmuir waves generated originally along the geomagnetic field may be nonlinearly scattered by whistler wave-induced lower hybrid waves, to propagate across the geomagnetic field. These obliquely propagating Langmuir waves are subsequently detected by Arecibo radar as frequency-upshifted plasma lines. The upshifted frequency as a function of HF wave frequency is in quite a good agreement with our theoretical prediction [

34]. It should be pointed out that the whistler waves responsible for this process in our Arecibo experiments are believed to be of lightning origin; this belief was supported by the findings that lightning occurred throughout our summer 1991 experiments and that we did not see this phenomenon often in our other summer experiments in the absence of lightning activities. As shown in Ref. [

34] and the sample data given

Figure 7 (upper), it requires rather high background plasma density, for the NAU-launched 40.75 kHz whistler waves to render the frequency-upshift of the Langmuir waves excited by the 8.175 MHz heater waves.

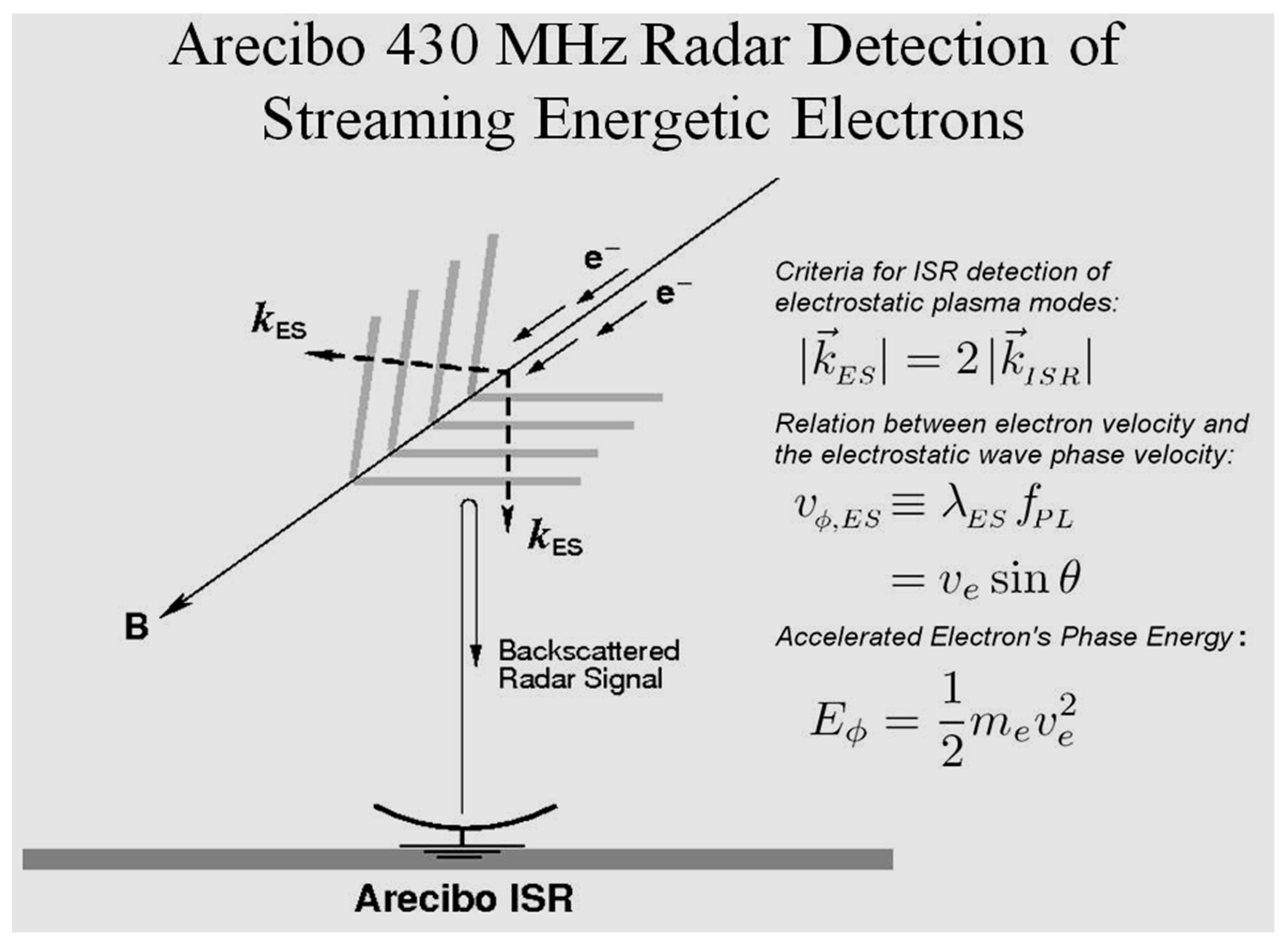

4.2. Energization of Ionospheric Plasmas by NAU-Launched Whistler Waves

As elaborated in Ref. [

30], the NAU whistler wave at 40.75 kHz can excite meter-scale lower hybrid waves together with field-aligned ionospheric irregularities in the ionospheric F-region. These short-scale lower hybrid waves can effectively accelerate ionospheric electrons along the geomagnetic field to cause airglows as well as F-region plasma line enhancement with a broad frequency range, along the wake of the whistler waves. These plasma lines have both frequency-upshifted and downshifted spectra, corresponding to downward and upward electron acceleration along the geomagnetic field, respectively. However, our subsequent study shows that a different mechanism accelerating ionospheric electrons can be caused by whistler wave-excited “tens of meter-scale” lower hybrid waves [

35]. This mechanism leads to forward acceleration of ionospheric electrons, detected by Arecibo radar as frequency-downshifted plasma lines only.

Figure 8 represents a diagram showing the detection of downward accelerated electrons by Arecibo radar. The phase energies (above 10 eV) of accelerated electrons can be inferred from the measured plasma lines [

36].

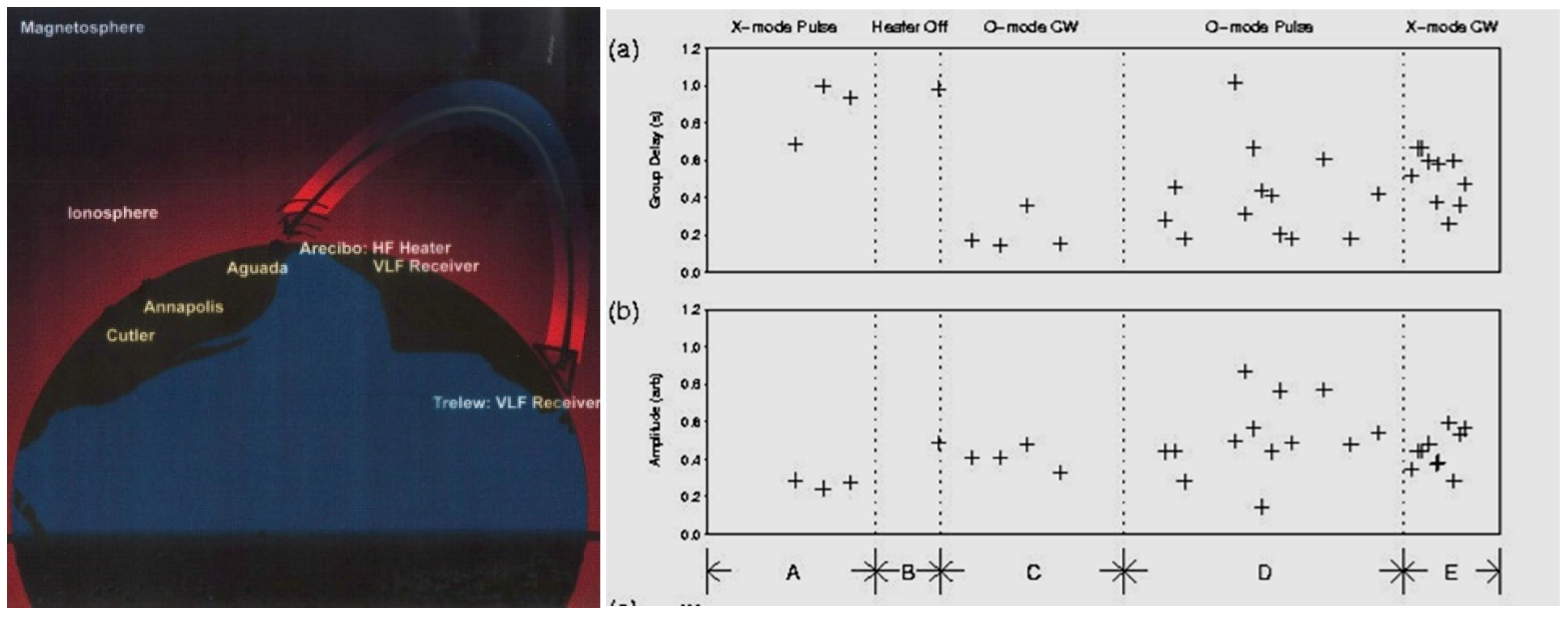

4.3. Conjugate NAU-Launched Whistler Wave Propagation Experiments

Our experiments on conjugate whistler wave propagation between Arecibo, Puerto Rico and Trelew, Argentina were conducted in the summer of 1997, using the Arecibo HF heater and the NAU transmitter at 28.5 kHz as illustrated

Figure 2 [

26]. The HF heater was operated in O-mode and X-mode alternately to demonstrate the generation of ionospheric ducts within the meridian plane (in the form of parallel-plate waveguides) for ducted whistler wave propagation. One VLF receiver was deployed at Arecibo Observatory and the other one near the geomagnetic conjugate point at Trelew in Argentina. The successful recording of ducted 28.5 kHz whistler waves in Argentina is seen in the data given in

Figure 9 [

37].

In

Figure 9a shows the transit times (group delays) of detected 28.5 kHz signals, propagating from Puerto Rico to Argentina. The corresponding intensities of recorded signals at Trelew, Argentina are given in

Figure 9b. It should be pointed out that no multiple hops expect occurring in the conjugate NAU-launched whistler wave propagation between Puerto Rico and Argentina.

The HF heater in O- and X-modes were run alternately. The data presented in

Figure 9 shows that, under the O-mode operation of the HF heater, the 28.5 kHz whistler wave had shorter transit times and higher intensities recorded at the magnetic point in Argentina. These results have clearly shown that parallel-plate waveguides (ionospheric ducts), generated by O-mode HF heater waves, have a better configuration than that by X-mode wave, for the ducted whistler wave propagation, to be recorded with higher intensities at the magnetic point in Argentina.

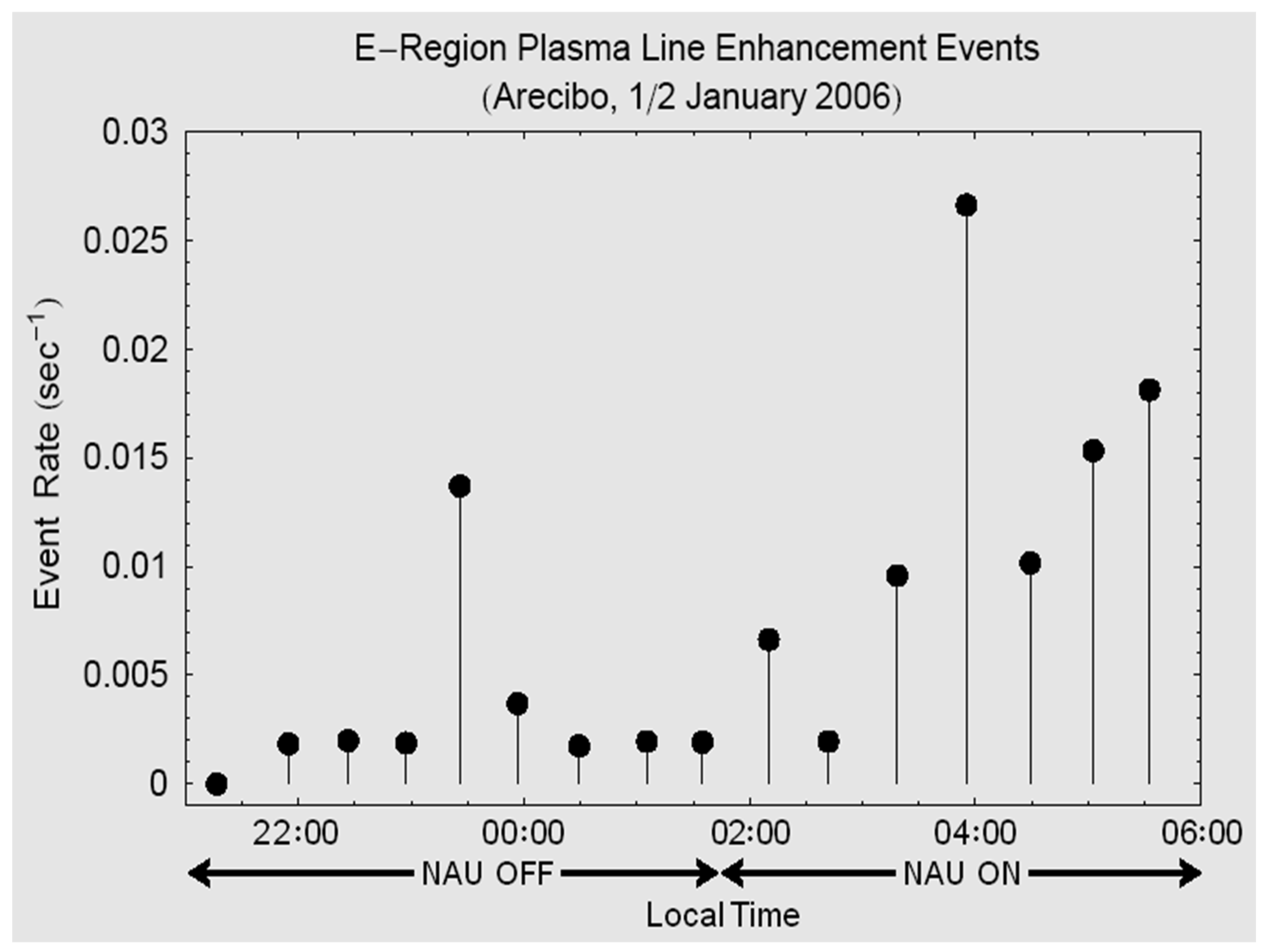

4.4. NAU-Launched Whistler Wave–Particle Interactions in Inner Radiation Belts

The NAU is not a scientific facility; however, it provided an opportunity to conduct experiments with the NAU transmitter in on-off mode, incidentally, from 10 PM on 1 January to 6 PM on 2 January 2006. After propagating from the ionosphere into the inner radiation belts, the NAU launched whistler waves can interact with trapped energetic electrons, and scatter some of them into the loss cone, resulting in 390 keV electron precipitation into the ionospheric E-region above Arecibo [

22,

23,

31]. These were detected by the Arecibo radar as enhanced E-region plasma lines with short periods (less than 10 s) of time. This is one of the distinctly different features compared with F-region plasma-line enhancement, which can last for much longer periods of time (about minutes or longer).

Figure 8 can also be used to show the radar detection of streaming electrons precipitated from the inner radiation belts into the ionospheric E-region. The 2006 experimental results are presented in

Figure 10 using a bar chart, to show the occurrence rates of plasma line enhancements in the absence of NAU signals (from about 10 PM on 1 January to 2 AM on 2 January) and in the presence of NAU signals (from about 2 AM to 6 AM on 2 January). A factor of 2.8 increase in plasma line enhancement rates between NAU on/off periods strongly suggests a causative relationship between them. It is expected that more electron precipitation events to be seen in the magnetic conjugate point in Argentina for future experiments to verify. Although these NAU on-off experiments could not be performed on a regular basis, the 2006 experiments have demonstrated the causative relationship between the plasma line enhancement and the NAU transmission-triggered electron precipitation above Arecibo.

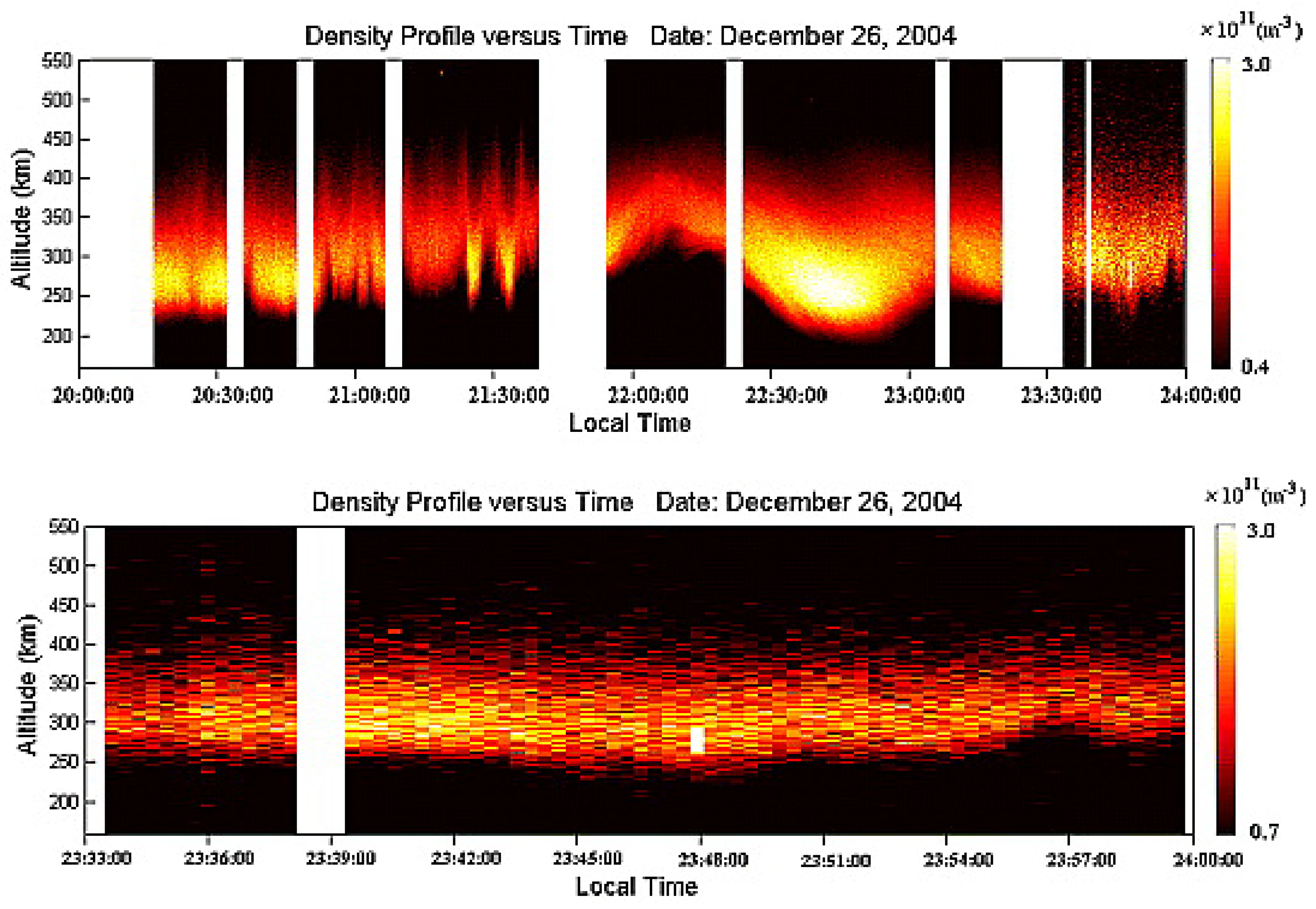

5. Observations of Acoustic Gravity Waves Due to Mw = 9.2 Earthquake

In Arecibo experiments on 26 December 2004, we observed a series of unusual acoustic gravity waves (AGWs), (also known as Traveling Ionospheric Disturbances (TIDs)]. After studying some earlier publications about earthquake and tsunami events [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71], and examining the 430 MHz radar and GPS data, it was found that these AGWs/TIDs resulted from the 9.2 Mw earthquake off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. It took about a day for the earthquake-launched tsunami waves to travel across the Indian Ocean, then into remote parts of the Atlantic Ocean [

72]. Illustrated in

Figure 11 are two routes (scenarios) to show how the Sumatra earthquake-launched tsunami on December 25 generated AGWs (TIDs), which then reached Puerto Rico on December 26, nearly one day later. These two routes are schematically denoted as Scenario 1 and Scenario 2, respectively in

Figure 11.

In Scenario 1, tsunami-induced AGVs due to sea-air interactions (i.e., forced gravity waves) or interactions with coasts would be launched close to the seismic epicenter and propagate along the great circle path between Sumatra and Puerto Rico. In Scenario 2, AGVs were considered to be generated relatively close to Puerto Rico, as tsunami waves propagated northward toward the coast of Brazil.

These two hypothesized scenarios were supported by BU–MIT data recorded by the 430 MHz radar and the digital ionosonde at Arecibo Observatory as well as by GPS satellites (see these instruments in

Figure 5). In brief, a relatively large solitary type of disturbances was associated with the rising/falling ionosphere over Arecibo, Puerto Rico, subsequently followed by a train of wavelike perturbations with persistent spread F features, as seen in

Figure 12. Scenario 2 in which causative AGVs (TIDs) were generated by nearby tsunami waves is consistent with the wavelike up/down sequence of F layer density observed after 23:33 LT, in the enlarged plots of

Figure 12.

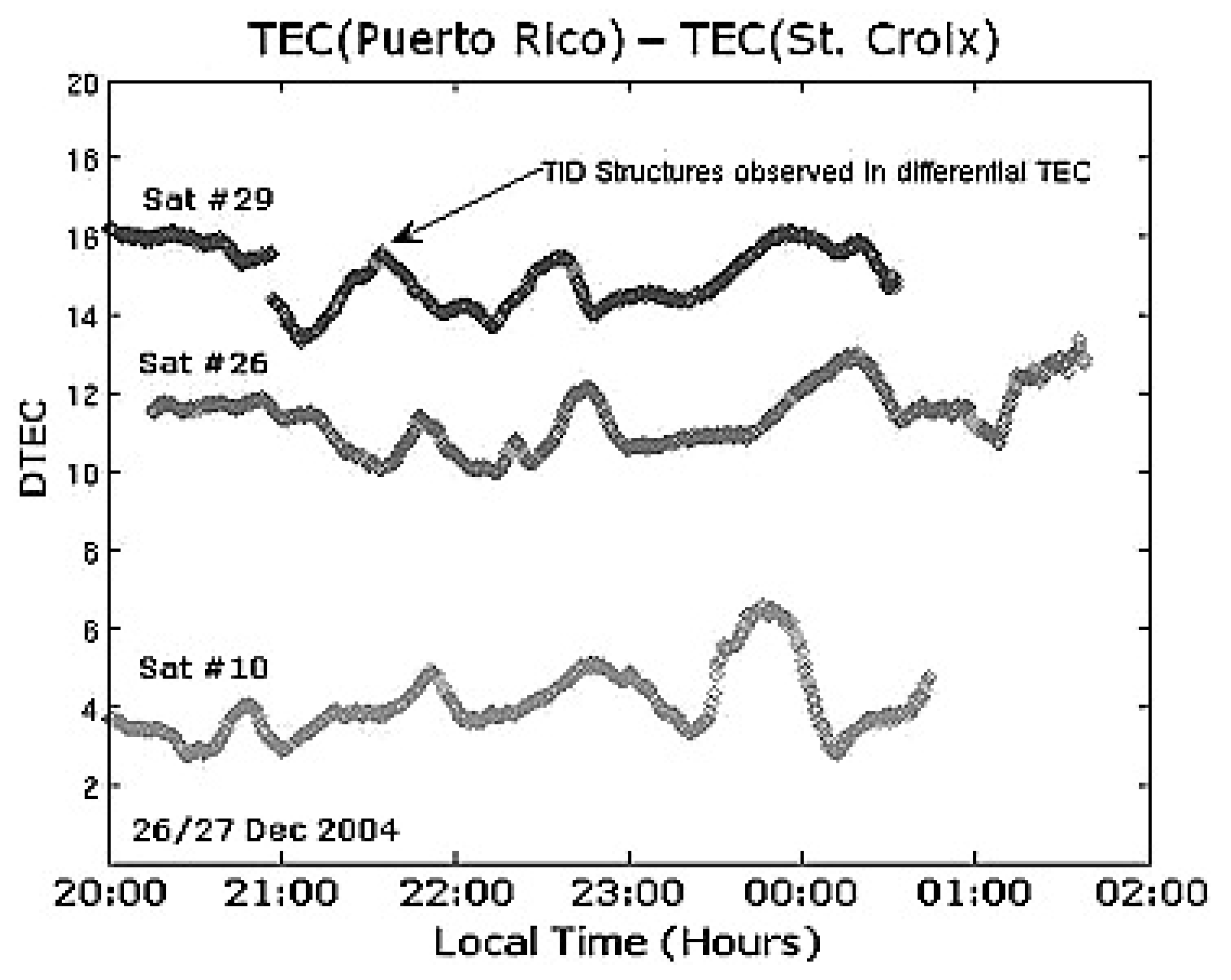

BU–MIT GPS measurements indicated that AGWs (TIDs) were active in the vicinity of Arecibo and supported both scenarios used to explain the radar data acquired on 26 December 2004. GPS/TID data were divided into three periods characterizing the ionosphere: (i) post-earthquake but prior to the detections of AGWs (TIDs) activity; (ii) initial widespread and sustained tsunami-induced AGWs (TIDs), and (iii) a late AGWs (TIDs) signature observed off the Atlantic coast of Spain. These snapshots provide evidence in support of Scenario 1 for tsunami-generated AGWs causing the ionospheric disturbance detected by the Arecibo 430 MHz radar. In other words, these results show that the same ionospheric disturbances were detected by the Arecibo radar and GPS sensors, albeit at different locations and times. The snapshots are consistent with Scenario 1 of ionospheric turbulence, triggered by tsunami-launched AGWs (TIDs) after traveling long distances from Sumatra to Puerto Rico.

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present GPS-based evidence for the AGWs (TIDs) activity in the Caribbean sector near the time of the Arecibo radar (see

Figure 12).

In summary, our GPS data recorded in Asia, Europe, and the Caribbean indicated that global AGWs (TIDs) were induced in the wake of tsunami-launched AGWs (TIDs), resulting in the large-scale “solitary type” of AGWs (TIDs) and then, subsequently, a train of AGWs (TIDs), observed at Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Our Arecibo experiments showed the possibility that seismic events can affect space weather halfway around the world on the following day.

6. Solar Energy Harvesting via Solar Powered Satellite

In this past June, I accepted the IEEE Boston Section’s invitation to organize and chair the 2026 IEEE International Fusion and Solar Energy Harvesting (FASEH) Symposium, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 12–14 May 2026 [

73]. The theme of the FASEH Symposium included (i) the natural fusion [i.e., the Large–Scale Solar Energy Harvesting, via the SPS/SBSP; and (ii) the controlled fusion using machines. However, because of the uncertainties in the global economy, politics, and visa issues for international attendees, it was proposed that this IEEE symposium be changed to a virtual one.

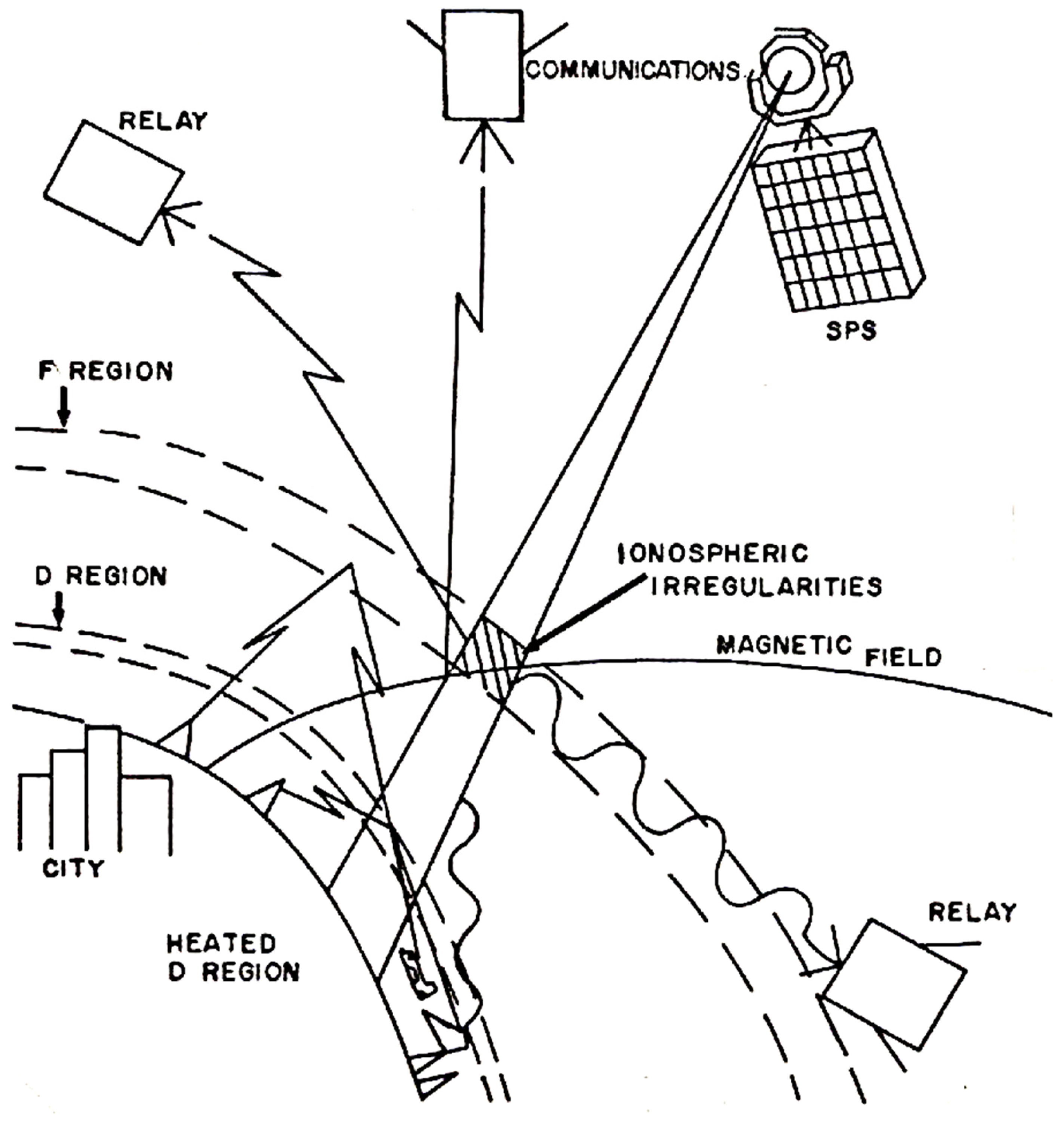

In the 1980s, this Large-Scale Solar Energy Harvesting Project was initially discussed in the scientific communities regarding launching satellites or setting up a space station, to collect solar energy and then, converting it to microwave beams aimed toward the Earth. A schematic to show the SPS/SBSP concept is given in

Figure 15 [

74]. The SPS/SBSP project was abandoned by the US for technical and economic reasons, though it was one of the topics discussed at the 1992 International Beacon Satellite Symposium, held at MIT Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA [

74]. An overview of current and future developments in beacon satellites was presented by the author at this Symposium, as the Symposium organizer and chair.

However, the rapid advancement in Microchips, Microelectronics, Energy Aware Computing, Power Electronics, and AI Applications has not only reinvigorated interest in SBSP/SPS but also sped up the development of Fusion and Solar Energy Harvesting across the USA, the Europe, and Asia. Furthermore, growing energy-efficiency computing technologies and advanced innovations in AI tools accelerate the deployment of green energy systems.

Thus, finally presented are our current research efforts in SPS/SBSP [Please let me keep this sentence!], which were inspired by our Arecibo experiments and laboratory study of plasma heating for Space and Fusion Energy applications. In fact, the SPS/SBSP process can be partially simulated in our Arecibo experiments under the under-dense ionospheric plasma heating by the HF heater, as well as in our laboratory experiments. The under-dense plasma heating refers to the situation where the injected HF wave frequency is greater than the local plasma frequency.

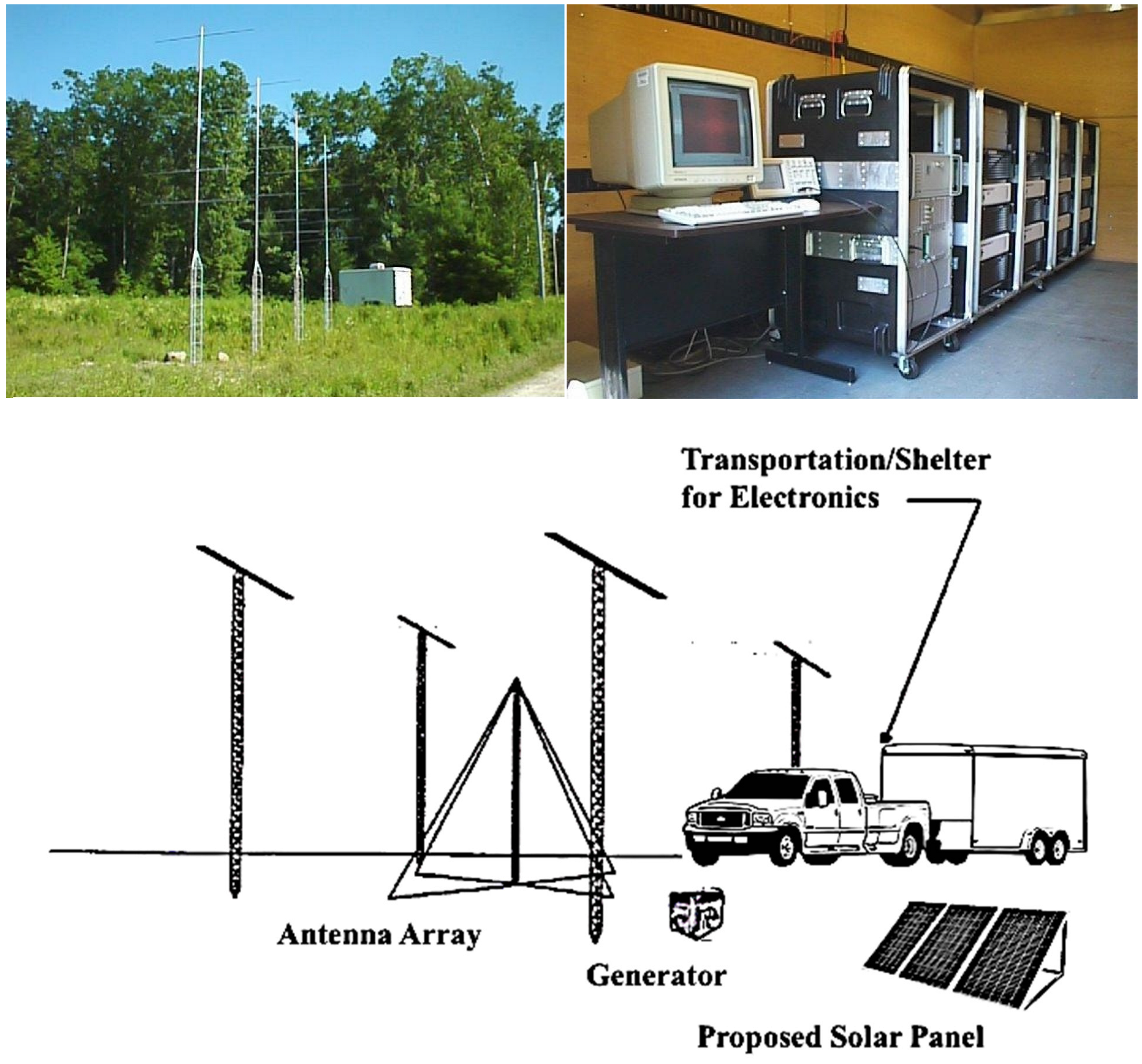

BU–MIT recent research on the Solar Energy Harvesting focuses on the ground-based Solar Powered Microwave Transmitting Systems (SPMTS), which can be used to simulate SPS/SBSP, especially, the microwave transmissions and interactions with the upper atmosphere. This planned SPMTS can be developed from our existing BU–MIT portable high-frequency (HF-VHF) transmitting system powered by diesel generators, as shown in

Figure 16.

7. Conclusions

This paper reviews BU–MIT experiments, conducted at Arecibo Observatory, Puerto Rico from 1989, until the 430 MHz radar collapsed on 1 December 2020. The reported Arecibo experiments in this paper have involved a large number of my BU and MIT students for their thesis research in collaboration with colleagues from several institutions (for example, Arecibo Observatory, AFRL, New York University, MIT Lincoln Lab). This research had been sponsored by AFOSR, AFRL, ONR, NASA, NSF, RADC, and MIT Lincoln Laboratory at different stages.

The large toroidal plasma machine called the “Versatile Toroidal Facility (VTF)” was constructed by five of my graduate students and twenty-five UROP (Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program) students during 1989–1991 at the MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center. This student-built device was used for BU–MIT laboratory experiments on RF heating of magnetized plasmas by injected microwaves and electron beams. The laboratory experiments successfully cross-checked and reproduced some of BU–MIT field experimental results obtained at Arecibo, for space and fusion energy applications. The optical and radio diagnostic instruments for BU–MIT laboratory and field experiments, such as all-sky imaging systems, portable HF-VHF radars, magnetometers, and a digital ionosonde were acquired by the equipment grants provided to BU and MIT from the US federal government. Some of these instruments will be used to develop the BU–MIT Solar Powered Microwave Transmitting System for solar energy harvesting research.

Funding

AFOSR, AFRL, ONR, NASA, NSF, RADC, and MIT Lincoln Laboratory at different stages.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

I had the privilege to conduct research with several professors at UCSD in the late 1970s on “high-power EM-wave interactions with plasmas for RF plasma heating”, with applications to laser and magnetic fusion and active experiments in space. They were Henry G. Booker, Jules A. Fejer, George J. Lewak, Ralph H. Loveberg, and William B. Thompson for my Ph.D. research, and Keith A. Brueckner, Tihiro Ohkawa, John H. Mamlberg, and William B. Thompson for my study of several plasma physics and controlled fusion courses. They had research connections with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Los Alamos National Laboratory, or General Atomics; Ohkawa was the founder of DIII-D National Fusion Facility at General Atomics, San Diego, CA, USA. Inspired by my research experience, I accepted the IEEE Boston Section’s invitation to organize the 2026 International Fusion and Solar Energy Harvesting (FASEH) Symposium. Last but not least, my students and I had numerous interactions with the founder of the Arecibo Observatory, William E. Gordon, both at conferences and workshops and during our visits to the Observatory for experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGW | acoustic gravity wave |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AFOSR | Air Force Office of Scientific Research |

| AFRL | Air Force Research Laboratory |

| ASIS | All-Sky Imaging System |

| BU | Boston University |

| CADI | Canadian Advanced Digital Ionosonde |

| DTEC | differential TEC |

| D region | the lowest part of the Earth’s ionosphere |

| E-region | a layer of the Earth’s ionosphere between about 90 and 150 km altitude |

| FASEH | International Fusion and Solar Energy Harvesting |

| ES | electrostatic |

| F-region | highest region of the Earth’s ionosphere |

| F layer | highest significant region of the Earth’s ionosphere |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HF | high-frequency |

| ISR | Ionospheric Sounding Radar |

| LT | Local Time |

| MIT | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| NAU | Naval Transmitter (code-named, Aguadilla, Puerto Rico) |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NSF | National Science Foundation |

| O-mode | ordinary mode |

| ONR | Office of Naval Research |

| PM | Post Meridiem |

| RADC | Rome Air Development Center |

| RF | radio frequency |

| RTI | range–time–intensity |

| Rx | receiver |

| SBSP | Space-Based Solar Power |

| SPS | Solar Power Satellite |

| spread F | irregularities in the ionosphere’s F-region |

| SPMTS | Solar-Powered Microwave Transmitting System |

| STEC | slant TEC |

| TEC | total electron content |

| TID | Traveling Ionospheric Disturbances |

| UCSD | University of California, San Diego |

| UROP | Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program |

| VHF | very high frequency |

| VLF | very low frequency |

| VTF | Versatile Toroidal Facility |

| X-mode | extraordinary mode |

References

- Lee, M.C. Whistler Wave Interaction Experiments at Arecibo Observatory Since 1989 (Past, Ongoing, and Proposed Research). In Proceedings of the Arecibo Observatory 50th Anniversary Symposium, Arecibo, PR, USA, 27–28 October 2013; Available online: https://phl.upr.edu/library/labnotes/50th-anniversary-of-the-arecibo-observatory (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Stenflo, L. Parametric excitation of collisional modes in the high-latitude ionosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1985, 90, 5355–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenflo, L.; Shukla, P.K.; Yu, M.Y. The theories for excitation of electrostatic fluctuations by thermal modulation of whistlers. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1986, 91, 11369–11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenflo, L.; Yu, M.Y.; Shukla, P.K. Electromagnetic modulations of electron whistlers in plasmas. J. Plasma Phys. 1986, 36, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenflo, L.; Shukla, P.K. Filamentation instability of electron and ion cyclotron waves in the ionosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1988, 31, 4115–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.K.; Stenflo, L.; Birgham, R.; Dendy, R.D. Ponderomotive force acceleration of ions in the auroral region. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1996, 101, 27449–27451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenflo, L.; Brodin, G. The three-wave coupling coefficients for a cold magnetized plasma. J. Plasma Phys. 2006, 2, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin, G.; Stenflo, L. On the parametric decay of waves in magnetized plasmas. J. Plasma Phys. 2009, 1, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerisier, J.C. Ducted and partly ducted propagation of VLF waves through the magnetosphere. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1974, 36, 1443–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, W.L.; Reagan, J.B.; Voss, H.D.; Gaines, E.E.; Datlowe, D.W.; Mobilia, J.; Helliwell, R.A.; Inan, U.S.; Katsufrakis, J. Direct observations of radiation belt electrons precipitated by controlled injection of VLF signals from a ground-based antenna. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1983, 10, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, W.L.; Voss, H.D.; Mobilia, J.; Walt, M.; Inan, U.S.; Carpenter, D.L. Characteristics of short duration electron precipitation bursts and their relationship to VLF wave activity. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1989, 94, 10079–10093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, U.S.; Walt, M.; Voss, H.D.; Imhof, W.L. Energy spectra and pitch angle distributions of lightning-induced precipitation: Analysis of an event observed on the S-81 (SEEP) satellite. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1989, 94, 1379–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennel, C.F.; Petschek, H.E. Limit on stably trapped particle flux. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1966, 71, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I. Effects of ions on whistler mode ray tracing. Radio Sci. 1966, 1, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, J.G.; Vampola, A.V. Effects of localized sources on quiet time plasmasphere electron precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1997, 82, 2671–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, R.F.; Kudeki, E. A causal relationship between lightning and explosive spread F. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1984, 11, 1165–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggin, D.; Kelley, M.C. The possible production of lower hybrid parametric instabilities by VLF ground transmitters and by natural emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1982, 87, 2545–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.C.; Farley, D.T.; Kudeki, E.; Siefring, C.L. A model for equatorial explosive spread F. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1984, 11, 1168–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, H.D.; Walt, M.; Imhof, W.L.; Mobilia, J.; Inan, U.S. Satellite observations of lightning-induced electron precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1998, 103, 11725–11744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.C.; Siefring, C.L.; Pfaff, R.F.; Kintner, P.M.; Larsen, M.; Green, R.; Holzworth, R.H.; Hale, L.C.; Mitchell, J.D.; Le Vine, D. Electrical measurements in the atmosphere and the ionosphere over an active thunderstorm: 1. Campaign overview and initial ionospheric results. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1985, 90, 9815–9823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishin, E.V.; Starks, M.J.; Ginet, G.P.; Quinn, R.A. Nonlinear VLF effects in the topside ionosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L04101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, L.; Nie, L. The VLF-induced ionospheric perturbations detected by DEMETER during solar minimum. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2023, 34, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Kuo, S.P. Excitation of magnetostatic fluctuations by filamentation of whistlers. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1984, 89, 2289–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.P.; Freidberg, J.P.; Lee, M.C. Ionospheric plasma modifications caused by the lightning induced electromagnetic effects. A Special issue in memory of Professor Henry G. Booker. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1989, 51, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, R.A. Whistlers and Related Ionospheric Phenomena; Dover Publications, Inc.: Mineola, NY, USA, 2006; Available online: https://archive.org/details/whistlersrelated0000hell (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Starks, M.J. Measurements of the Conjugate Propagation of VLF Waves by Matched Filter and Application to Ionospheric Diagnosis. Ph.D. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/80126 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Lee, M.C.; Kuo, S.P. Production of lower hybrid waves and field-aligned plasma density striations by whistlers. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1984, 89, 10873–10880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, R.F.; LaHoz, C. Radar observations of F region equatorial irregularities. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1976, 81, 5447–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K.M. Nonlinear Ionospheric Propagation Effects on UHF and VLF Radio Signals. Ph.D. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Labno, A.; Pradipta, R.; Lee, M.C.; Sulzer, M.P.; Burton, L.M.; Cohen, J.A.; Kuo, S.P.; Rokusek, D.L. Whistler-mode wave interactions with ionospheric plasmas over Arecibo. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2007, 112, A03306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradipta, R.; Labno, A.; Lee, M.C.; Burke, W.J.; Sulzer, M.P.; Cohen, J.A.; Burton, L.M.; Kuo, S.P.; Rokusek, D.L. Electron precipitation from the inner radiation belt above Arecibo. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L08101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Riddolls, R.J.; Burke, W.J.; Sulzer, M.P.; Kuo, S.P.; Klien, E.M.C. Generation of large sheet-like ionospheric plasma irregularities at Arecibo. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 3067–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Riddolls, R.J.; Vilece, K.D.; Dalrymple, N.E.; Rowlands, M.J.; Moriarty, D.T.; Groves, K.M.; Sulzer, M.P.; Kuo, S.P. Laboratory reproduction of Arecibo experimental results: HF wave-enhanced Langmuir waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1997, 24, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.P.; Lee, M.C. A source mechanism producing HF-induced plasma lines (HFPLs) with upshifted frequencies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1992, 19, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooker, L.A.; Lee, M.C.; Pradipta, R.; Ross, L.M.; See, B.; Sulzer, M.P.; Tepley, C.; Gonzales, S.A.; Aponte, N. Forward acceleration of ionospheric electrons by NAU 40.75-kHz whistler waves over Arecibo. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2013, 41, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, H.C.; Vickwar, V.B.; Mantas, G.P. Observations of fluxes of superthermal electrons accelerated by HF excited instabilities. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1982, 44, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, M.J.; Lee, M.C.; Jastrzebski, P. Interhemispheric propagation of VLF transmissions in the presence of ionospheric HF heating. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2001, 106, 5579–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artru, J.; Lognonné, P.; Blanc, E. Normal modes modeling of post-seismic ionospheric oscillations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artru, J.; Farges, T.; Lognonné, P. Acoustic waves generated from seismic surface waves: Propagation properties determined from Doppler sounding observation and normal-modes modeling. Geophys. J. Int. 2004, 158, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artru, J.; Ducic, V.; Kanamori, H.; Lognonné, P.; Murakami, M. Ionospheric detection of gravity waves induced by tsunamis. Geophys. J. Int. 2005, 160, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artru, J.; Lognonné, P.; Occhipinti, G.; Crespon, F.; Garcia, R.; Jeansou, E.; Murakami, M. Tsunami detection in the ionosphere. Space Res. Today 2005, 163, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Basu, S.; Ganguly, S.; Klobuchar, J.A. Generation of kilometer scale irregularities during the midnight collapse at Arecibo. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1981, 86, 7607–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, R.A. F layer height bands in the nocturnal ionosphere over Arecibo. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1979, 84, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, F.; Testud, J.; Kersley, L. Medium scale gravity waves in the ionospheric F-region and their possible origin in weather disturbances. Planet. Space Sci. 1975, 23, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.L.; Aponte, N.; Earle, G.D.; Sulzer, M.; Larsen, M.F.; Peng, G.S. Arecibo observations of ionospheric perturbations associated with the passage of Tropical Storm Odette. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2006, 111, A11320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasGupta, A.; Das, A.; Hui, D.; Bandyopadhyay, K.K.; Sivaraman, M.R. Ionospheric perturbation observed by the GPS following the December 26th, 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake. Earth Planets Space 2006, 35, 929–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuth, F.T.; Sulzer, M.P.; Elder, J.H.; Wickwar, V.P. High-resolution studies of atmosphere-ionosphere coupling at Arecibo Observatory, Puerto Rico. Radio Sci. 1997, 32, 2321–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuth, F.T.; Sulzer, M.P.; Gonzales, S.A.; Mathews, J.D.; Elder, J.H.; Walterscheid, R.L. A continuum of gravity waves in the Arecibo thermosphere? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L16801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducic, V.; Artru, J.; Lognonné, P. Ionospheric remote sensing of the Denali Earthquake Rayleigh surface waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, S.H. Acoustic-gravity modes and large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbances of a realistic, dissipative atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1973, 78, 2278–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Crespon, F.; Lognonné, P. Observations of post-seismic ionospheric disturbances following the great Sumatra earthquake from GPS networks. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2005, 7, 03186. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.-Q.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, D.-H. Responses of the Ionosphere to the Great Sumatra Earthquake and Volcanic Eruption of Pinatubo. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2006, 23, 1955–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, C.O. Internal atmospheric gravity waves at ionospheric heights. Canad. J. Phys. 1960, 38, 1441–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, C.O. Motions of the neutral atmosphere. In Physics of the Earth’s Upper Atmosphere; Hines, C.O., Paghis, I., Hartz, T.R., Fejer, J.A., Eds.; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1965; pp. 134–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, M.C.; Larsen, M.F. Gravity wave initiation of equatorial spread F: A case study. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1981, 86, 9087–9100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Riddolls, R.J.; Burke, W.J.; Sulzer, M.P.; Klien, E.M.C.; Rowlands, M.J.; Kuo, S.P. Ionospheric plasma bubble generated by Arecibo heater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Klien, E.M.C.; Burke, W.J.; Zhang, A.X.; Riddolls, R.J.; Kuo, S.P.; Sulzer, M.P.; Isham, B. Augmentation of natural ionospheric plasma turbulence by HF heater waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1999, 26, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-B.; Ma, K.-F.; Chen, Y.-I.; Tsai, H.-F.; Lin, C.-H.; Kamogawa, M.; Lee, C.-P. Ionospheric GPS total electron content (TEC) disturbances triggered by the 26 December 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2006, 111, A05303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lognonné, P.; Clvd, C.; Kanamori, H. Normal mode summation of seismograms and barograms in an spherical Earth with realistic atmosphere. Geophys. J. Int. 1998, 135, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lognonné, P.; Jeansou, E.; Garcia, R.; Artru, J.; Occhipinti, G.; Crespon, F.; Achache, J.; Helbert, J.; Moreaux, G. Detection of the Ionospheric perturbation associated to the tsunami of December 26th, 2004 with Topex and Jason-1 TEC data. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2005, 7, 09028. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297161598_Detection_of_the_Ionospheric_perturbation_associated_to_the_tsunami_of_December_26th_2004_with_Topex_and_Jason-1_TEC_data (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Lognonné, P.; Artru, J.; Garcia, R.; Crespon, F.; Ducic, V.; Jeansou, E.; Occhipinti, G.; Helbert, J.; Moreaux, G.; Godet, P.-E. Ground based GPS tomography of ionospheric post-seismic signal. Planet. Space Sci. 2006, 54, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, J.P.; Singh, S.; Bamgboye, D.K.; Johnson, F.S.; Kil, H. Occurrence of equatorial F region irregularities: Evidence for tropospheric seeding. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1998, 103, 29119–29136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolls, M.J.; Kelley, M.C.; Coster, A.J.; Gonzalez, S.A.; Makela, J.J. Imaging the structure of a large-scale TID using ISR and TEC data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L09812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolls, M.J.; Kelley, M.C. Strong evidence for gravity wave seeding of an ionospheric plasma instability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L05108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti, G.; Lognonné, P.; Kherani, E.; Hbert, H. Three-dimensional Waveform modeling of ionospheric signature induced by the 2004 Sumatra tsunami. Geophys Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L20104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti, G. Multi-parametric Observations and Modeling of Ionospheric Signature of Great Sumatra Earthquake. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Paris, France, December 2006. (In French). Available online: https://theses.fr/2006GLOB0012 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ossakow, S.L. Spread-F theories: A review. J. Atmos. Terr. Phys. 1981, 43, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, W.; Coster, A.J. Automated GPS processing for global total electron content data. GPS Solut. 2006, 10, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D. Tsunami and earthquakes: What physics is interesting? Phys. Today 2005, 58, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titov, V.; Rabinovich, A.B.; Mofjeld, H.O.; Thomson, R.E.; Gonzalez, R.J. The global reach of the 26 December 2004 Sumatra tsunami. Science 2005, 309, 2045–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. Modeling the Sumatra–Andaman earthquake reveals a complex, nonuniform rupture. Phys. Today 2005, 58, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Pradipta, R.; Burke, W.J.; Labno, A.; Burton, L.M.; Cohen, J.A.; Dorfman, S.E.; Coster, A.J.; Sulzer, M.P.; Kuo, S.P. Did Tsunami-Launched Gravity Waves Trigger Ionospheric Turbulence over Arecibo? J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2008, 113, A01302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The IEEE International Fusion and Solar Energy Harvesting (FASEH) Symposium, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 12–14 May 2026. Available online: https://ieee-faseh.org (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Burke, W.R. In Proceedings of the International Beacon Satellite Symposium, organized by M.C. Lee and held at MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center, Call Number: QC881.2.I6I471992, Cambridge, MA, USA, 6–10 July 1992. Available online: https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1992ESASP1154.....B (accessed on 20 November 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).