1. Introduction

The banking industry is considered one of the most important and rapidly growing sectors which manages financial stability globally. In the last few decades, the banking sector experienced massive changes due to technological transformation [

1]. In New Zealand, the banking sector provides crucial financial guidance to domestic and international customers who require secure, prompt, and convenient banking services [

2]. Digital banking provides financial services to customers through online platforms [

1]. With the development of the Internet, traditional banking services were shifted to digital platforms, and this process was accelerated with the advent of smartphones. Therefore, globally, banks started to adopt digital banking to improve the service and to minimise the operational cost [

3].

New Zealand banking customers mirror this universal pattern and start adopting digital banking services [

4]. New Zealand or Aotearoa is a nation with two main islands and several small islands which has diverse ethnic groups [

5]. Individuals in these different ethnic groups became avid adopters of digital banking, making it a competitive necessity for their daily financial requirements [

3]. Banks always attempt to develop and maintain long-term customer relationships. It is a complex process which requires banks to focus on several areas [

2]. Previous empirical studies found that the adoption of digital banking services is based on trust [

6]. High-quality service on digital platforms enhances customer trust and fosters commitment to using digital banking platforms [

3]. Offering a positive user experience to customers further enhances the trust and commitment towards digital platforms [

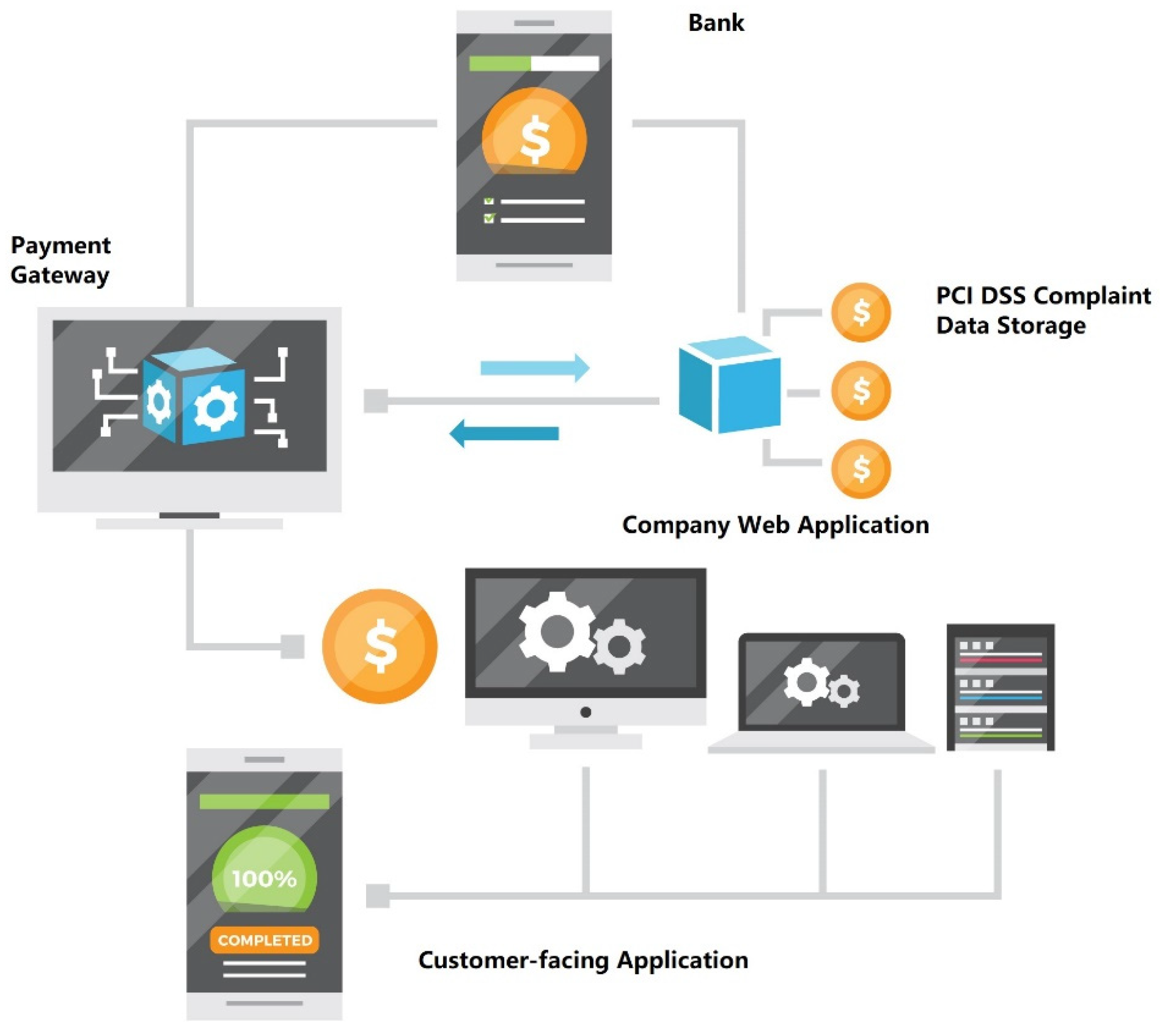

7]. When customers feel that financial data is safe and secure through a reliable workflow (see

Figure 1, where the arrows represent requests such as authorisation/charge sent from the company web app, and responses when approval/decline/token return). As customers’ emotional attachment to the platform is boosted, and as a result, their trust and commitment towards the platform increase [

8]. However, the perceived risk of using digital banking platforms negatively affects customer trust and commitment [

9].

The economic benefits of banking are multifaceted. It not only supports the financial stability of a country but also generates employment, attracts foreign investments, and encourages individuals to save and invest. All in all, digital banking offers an array of benefits to New Zealanders. It provides easy access to international financial services and greater financial inclusion to drive the country’s economy [

4,

5]. Therefore, this study’s primary objective is to explore the effect of service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk on customers’ trust and commitment to using digital banking platforms in New Zealand.

Digital banking platforms in New Zealand have undergone a significant transformation. The rapid development of technology worldwide and in New Zealand has led to a shift in consumer consumption habits and lifestyles from traditional physical banking services to digital banking services [

10]. This is because digital banking platforms are considered convenient, efficient, and inexpensive techniques for financial transactions due to features like high service quality, security, and a unique user experience [

11]. Nevertheless, research around service quality, security and perceived risk on customer commitment to using digital banking platforms in New Zealand is scarce [

10].

International studies and related services work link service quality, security and privacy, usability/experience, and trust to downstream relationship outcomes [

1,

6,

7,

11], with New Zealand studies showing service quality–satisfaction and trust–loyalty relationships in internet banking [

3,

8] and intention models for NZ digital banking [

4]. Three gaps remain. First, most work emphasises intention, satisfaction, or loyalty rather than customer commitment as the focal outcome [

6,

11]. Second, many studies test one or two predictors rather than a single model that compares their relative influence via trust [

1,

3,

8,

11]. Third, results for perceived risk are mixed, with some models showing limited or non-significant effects [

1], and few papers discuss how market history and older-user segments may shape digital-banking responses [

2,

10]. Our study addresses these gaps by explaining commitment, estimating a trust-mediated model that compares four antecedents, and testing whether perceived risk still matters in a sample with high user experience.

Understanding the customer’s perception of the features of digital platforms assists banks in identifying the available opportunities and threats [

12]. This strategy allows the banks to invest in emerging digital technologies while addressing the associated perceived risk to promote the usage of digital services among customers. Due to the risk of technology failures and security concerns, some customers perceive digital banking as risky [

9,

13,

14]. Banks could improve user experience by providing high service quality, responding to security concerns swiftly and minimising perceived risk. In return, customers build long-term commitment towards the platform. Therefore, examining these factors helps banks to better understand the valuable insights into customer expectations and concerns. This insight may assist the banking sector in New Zealand in developing digital services to build customer trust and commitment.

Previous studies have identified trust as a key factor in fostering customer commitment to digital platforms [

15,

16]. It will be interesting to explore whether trust would enhance customer commitment in the banking sector. Hence, the importance of this study is explained.

Prior work in New Zealand has examined factors influencing digital banking [

4,

17], and banks must select features suited to the local context [

4]. We test whether service quality, security and privacy, emotional attachment, user experience, and perceived risk relate to trust and customer commitment in New Zealand digital banking.

This study aims to examine the effect of service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk of digital banking platforms on customer commitment. It further posits that customer trust acts as the mediating variable that links the predicting variables and the outcome. The motivation of this study is twofold. First, this study examines the commitment and the mediating role of trust in the context of the New Zealand banking industry. Banks could use the findings of this study to align services according to customer expectations and to effectively design digital strategies according to the New Zealand context.

Secondly, the banking industry plays an important role in the New Zealand economy by maintaining financial stability and promoting investment. Moreover, the banking sector drives economic growth and builds customer confidence in the financial system. The total equity of New Zealand banks in 2023 was

$59.96 billion. The banking industry supported the economy by contributing

$357.5 billion in loans to households and

$124.5 billion in loans to businesses [

18]. Therefore, these findings provide more insights for banking professionals, financial analysts, investors and financial sector policymakers to understand the economic growth and stability of New Zealand.

This study contributes in three ways. First, it treats trust as a path to customer commitment, which moves beyond models that stop at intention. Second, it provides a single model that compares the size of indirect effects from service quality, security and privacy, user experience, and emotional attachment. Third, it identifies a boundary condition in a mature user group where perceived risk does not explain commitment through trust.

2. Theoretical Background

Digital banking enables customers to conduct financial transactions on virtual channels (for example, mobile, online, and video) beyond branch interactions [

4,

19]. Adoption and continued use reflect both technology beliefs and relationship factors. This study draws on four theories to explain links between the antecedents (service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment, perceived risk), the mediator (trust), and the outcome (customer commitment). The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) posits that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use shape behaviour [

20]. Perceived usefulness refers to expected performance benefits (for example, productivity and efficiency), while perceived ease of use refers to reduced effort through a user-friendly interface and easy-to-learn features; together these beliefs support adoption of digital banking [

21]. Commitment–Trust Theory argues that trust underpins enduring customer commitment and long-term relationships [

22]. Trust helps reduce uncertainty in the absence of complete rules or information [

23]; trusted relationships are associated with satisfaction and loyalty, and customers who trust their online banking provider are less likely to switch [

24]. In digital communities, observed behaviour can also inform decisions to continue or terminate relationships [

21].

Service quality (SERVQUAL) provides a framework for evaluating service performance across tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [

25]. In digital banking, tangibles map to interface design and performance; reliability and responsiveness capture accuracy and timeliness; assurance reflects competence and credibility (including security signalling); and empathy relates to personalisation. These dimensions can strengthen trust and, via trust, support commitment. Perceived Risk Theory explains how uncertainty and potential loss influence consumer decisions [

26]. Perceived risk comprises uncertainty and consequence [

27] and can deter adoption when expected losses loom larger than benefits [

28]. In digital banking, concerns about security and privacy can slow uptake; identifying and addressing these risks is therefore important for building trust in digital channels [

27].

By integrating the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Commitment–Trust Theory and Service Quality (SERVQUAL) and perceived risk model, the study posits that trust serves as a mediator between understudied independent variables (emotional attachment, user experience, security and privacy, risk) and commitment. Theoretically, the user experience that can be derived from TAM influences trust by shaping expectations of efficiency and ease in digital banking interactions [

20,

29]. Service quality dimensions enhance trust by demonstrating competence, security, and customer-centricity [

25]. Perceived risk, encompassing uncertainty and potential loss, reduces trust when security or privacy concerns are salient [

27,

28]. Emotional attachment and user experience also act through trust to foster commitment. Trust is modelled as the mediator because prior research indicates that in digital banking contexts, trust consistently channels the effects of cognitive, emotional, and service-related factors into enduring commitment, while direct effects of antecedents on commitment are minimal or theoretically less justified [

22,

23,

24].

2.1. Hypothesis Development

2.1.1. Trust and Commitment to Use

Ref. [

30] defines trust as the confidence to rely on another partner. Trust is also described as the individual’s opinion of a particular service/product which satisfies their expectations [

31]. It minimises the complexity of situations by reducing the need for strict rules and regulations [

30]. Other argues that trust comprises three components: effectiveness, integrity and empathy, and this level of trust varies according to individuals’ perceptions [

30,

31]. Therefore, organisations need to evaluate trust at the individual consumer level.

In digital banking services, trust refers to the customer’s confidence in the integrity of the digital banking platform [

32]. Trust is a vital element in the success of electronic transactions. It is based on confidentiality, authentication and overall acceptance of the transaction [

30,

33]. Given that new self-service financial technologies lack personal interaction, trust is considered an essential construct [

31]. During the introductory stage of technology adoption, features like user-friendliness promote trust among users [

33]. Trust reduces customer scepticism regarding the ease of use and security features of the digital platform. It plays a vital role as a mediator between service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment, and perceived risk in customers’ commitment to digital banking [

31,

34]. It enhances the relationship between these independent variables, and commitment and is considered the basis for a long-term relationship. These long-term relationships build functional and emotional benefits between digital service providers and customers; as a result, customers perceive the relationship as important and try to maintain it [

35]. [

36] further highlights that in online platforms, trust acts as a bridge to foster positive expectations and commitment. Therefore, in digital banking, this trust is considered the foundation to build customers’ confidence regarding the platform, as those services involve limited personal interactions [

35,

36].

Commitment is an expressed or unexpressed promise among two parties involved in an exchange [

36]. Ref. [

37] defines commitment as a long-term desire to continue an important bond. Commitment is considered a vital factor in continuing long-term relationships [

22,

32]. It is heavily based on the customer’s prior positive experience towards the service. Commitment is a multi-dimensional creation of affective, calculative and normative components [

38]. Affective commitment discusses the emotional bond and identification a customer maintains with a product/service. It is a desire-based attachment. In calculative commitment, consumers evaluate the costs and benefits of continuing or terminating the bond when a person has no better options or the high switching cost prevents consumers from making calculated commitments. Normative commitment is an obligation to maintain relationships with a product/service. Social norms drive it [

38]. As proposed by [

39], commitment has two dimensions: normative and instrumental. However, [

32] highlights that normative commitment is less important in the digital context. Customer commitment is considered a vital factor in banking, and banks always attempt to maintain their warrants [

40]. In the context of digital banking, commitment is the psychological bond customer feel for their banking service provider despite the availability of other options. It is based on customers’ positive experiences with the bank [

40]. Customers who have high feelings of attachment, such as affection, happiness, and pleasure, towards digital platforms are more loyal to digital banking and involved in high affective commitment.

2.1.2. Service Quality, Commitment to Use and Trust

Service quality is conceptualised as the discrepancy between consumers’ perception of services offered by a particular firm and their expectations about the actual offering [

4,

25]. It indicates how customers’ service expectations are compared with the actual service they experienced. Others like [

41] describe service quality as the perception of a satisfied outcome, while [

42] suggests service quality as the support that a system user experiences by using the system. Nevertheless, the SERVQUAL model has become a widely used technique in measuring service quality [

25].

Recognition of service quality in the banking sector has become a widely examined factor [

43]. The traditional banks operated in a non-competitive, highly regulated environment; therefore, traditional banks were not concerned much with service quality issues. Security of cash was the primary concern of traditional banks. However, the revolution of traditional banking into digital platforms identified the requirement of maintaining reliable online service while protecting customer information. High service quality offers customised services and a new range of products to build a strong relationship with customers [

44]. Indeed, [

45] have demonstrated that service quality is crucial in enhancing commitment to use in mobile banking. Equally, [

11] observed that service quality is an important determinant for customers to commit to digital banking. All in all, service quality has become a vital factor in the success of many digital businesses.

In addition to the trust-commitment theory by Morgan and Hunt (1994), which suggests the link between commitment and trust, previous empirical studies have also observed a similar theme [

35,

36]. The service quality of an online banking platform explains the degree of customer interaction in obtaining data [

46]. Several studies consider trust as the measure of customer confidence in using a quality and reliable service. High service quality minimises uncertainties and builds customer confidence [

47]. As a result, customers use digital platforms for their financial transactions. This has also been confirmed by [

36] that the customer’s trust in adapting digital platforms depends on excellent service quality. Concluding the discussion thus far, it is fair to hypothesise the following:

H1. Service quality positively affects commitment to use, and this relationship is mediated by trust.

2.1.3. Security and Privacy, Commitment to Use and Trust

Security and privacy are fundamental pillars of the banking industry as they store confidential customer data [

48]. The banking system handles sensitive customer data; hence, it needs a high level of security and control. Since the advent of computers, the banking security system has been breached frequently [

49]. Fortunately, the industry had experienced less intrusion than today during the early development stages of computers [

48]. Examples of online vulnerabilities and threats include data breaches, data stolen and virus attacks. Due to poor security systems, unauthorised parties will view and steal data from the banking [

49]. Consequently, these threats create digital banking nervousness among customers [

48].

According to the Perceived Risk theory, the consumer’s decision-making process is influenced by the level of risk they perceive. Numerous studies have examined how security and privacy issues positively impact consumer commitment, with trust acting as a mediator [

50,

51]. A study by [

50] investigated the impact of security issues on citizens’ adoption of e-government services during the pandemic period. The analysis revealed that perceived security enhances trust, positively influencing customer commitment to e-government services. To maintain a long-term trustworthy relationship with customers, banks would need to handle customer transactions securely without any mistakes. Moreover, when the customer receives a high level of security and privacy in a digital platform, their trust increases and their commitment to using the platform increases as they feel more secure, confident, and reliable in their connections [

52]. Hence, this study hypothesises the following:

H2. Security and privacy positively affect commitment to use, and this relationship is mediated by trust.

2.1.4. User Experience, Commitment to Use and Trust

User experience is conceptualised as a customer’s cognitive judgement on the company’s direct and indirect points associated with their purchasing activities [

53,

54]. It is all features of a consumer’s experience with a particular system and combines three factors: the consumer, the interactive system and the technology. User experience is a discrete construct from service quality, and it begins before the service starts and continues after the service is over, which is mainly affected by customer expectation, customer satisfaction during the service, word-of-mouth, and brand reputation [

7,

53]. User experience in digital banking relies heavily on the latest technology. To ensure the efficiency of technology, businesses need to provide user-friendly technology for their customers. The literature has documented that positive user experience in digital banking, which ultimately relies on the banking technology capability, has enhanced the commitment to use the technology [

55]. This phenomenon can be explained using the Technology Acceptance Model, TAM [

20], which argues that ease of use and perceived usefulness enhance attitudes and behavioural intention to use the technology.

The positive user experience in digital banking platforms also builds trust among users. As highlighted by [

56], the customisation of available digital banking platforms according to customer requirements using personalised financial management tools enhances this customer experience. As a result, customers with a better experience with digital banking products always trust the same product in the future, leading to commitment to use the platform in future [

57]. Managing user interference effectively in digital banking platforms enhances customer experience, which influences customers’ trust and the commitment to engage in digital platforms in future [

4]. Therefore, the study posits the following:

H3. User experience positively affects commitment to use, and this relationship is mediated by trust.

2.1.5. Emotional Attachment, Commitment to Use and Trust

Emotional attachment reflects consumers’ feelings about a particular brand [

58,

59]. In marketing, emotional attachment is conceptualised as the ‘bond that connects a consumer with a specific brand and involves feeling towards the brand and the feelings include affection, passion and connection’ [

58]. Others, such as [

60], explain emotional attachment as a trust-based relationship with the product or service. This attachment is built gradually over a long period. The user’s emotional attachment towards technology is based on the aesthetic design of the product [

61]. Colour, shape and animations are considered as aesthetic design of the product [

61]. Visual designs stimulate the human visual senses, creating an emotional attachment between the user and the product [

61], while [

62] highlights that appealing designs enhance perceived enjoyment, thereby building an emotional attachment. New technology users give more consideration to emotional values. It is anticipated that emotional attachment will enhance the user’s attitudes towards technology [

61]. Research by [

63] considers emotional attachment and the interface to be the most important aspects of digital platforms. Banks always strive to strengthen their relationship bonds with their customers. All in all, this study conceptualises emotional attachment as the bond that connects a consumer with a specific brand, which is built over time based on both emotional and functional features of online banking. Therefore, banks need to balance both emotional and functional features to satisfy customer preferences.

An empirical study conducted by [

64] highlights that consumers encounter many products daily, but they develop strong emotional attachments only with limited products or services. Therefore, when they establish an emotional attachment, they tend to trust that the provider will fulfil their desires, which in turn leads to higher commitment, like brand loyalty. Furthermore, a study conducted by [

59] investigated that emotional attachment directs consumers to purchase the brand and motivates them to continuously purchase the brand. A study by [

59] considers emotional attachment and the interface to be the most important aspects of digital platforms. Banks are always trying to build relationship bonds with their customers. Therefore, banks transform customers’ cognitive interaction into emotional attachments relating to banking products, which ensures that customers build trust [

65]. Strong emotional bonds between customers and their banks are considered when digital platforms offered by the respective bank are reliable and trustworthy. As [

59] highlights, it is important to build an emotional attachment towards the service/product as it directly and indirectly affects customer commitment. Customers with higher emotional attachment to digital platforms experience a high level of commitment to use the platform due to the positive emotions and psychological benefits which the platform provides [

66]. Positive emotional experiences on digital platforms build consumer trust and commitment [

67]. The banks that offer emotionally involved digital experiences could enhance customer trust and commitment. Therefore, it is fair to hypothesise the following:

H4. Emotional attachment positively affects commitment to use, and this relationship is mediated by trust.

2.1.6. Perceived Risk, Commitment to Use and Trust

Perceived risk is the degree to which a consumer suffers losses by being involved in an action [

68]. According to [

69], the perceived risk is a major obstacle to the acceptance of any technology, notably in the service sector. At the early stages of technology adoption, consumers are reluctant to adopt the technology due to high perceived risk. Higher perceived risk is mainly due to a lack of knowledge and a lack of available information to users [

9]. Therefore, consumers adopt the technology after they gather sufficient knowledge about it [

69]. Perceived risk in digital banking may arise due to theft, lack of a device and knowledge to access, poor network connections, etc [

34]. Customers consider virtual transactions in digital banking to be difficult to understand on their own. Then customers feel uncertain about banking products, creating a high perceived risk. Therefore, banking customers require financial knowledge as financial services are risky and complex [

9]. Banking consumers are concerned about the security and confidentiality of their personal information on the digital banking platform [

69].

Previous studies have found that perceived risk forms a crucial element in the resistance to using digital banking [

34]. For example, in Wisker’s (2023) study, she observed how the senior citizens’ customers believe that the perceived risk associated with online banking platforms is higher than traditional physical banking [

34]. The relationship between the perceived risk of digital banking platforms and customers’ trust and commitment to using digital platforms can be explained by the Perceived Risk theory [

26] and Trust Commitment theory [

22]. According to Perceived Risk Theory [

26], consumers are not only concerned about the potential benefits they gain from the product/service, but they are also trying to avoid perceived risk. Perceived risk is a personal evaluation of the negative consequences and uncertainties of a particular action [

70]. These risks can be in the form of financial, physical, social and psychological risks. This theory highlights that higher perceived risk makes consumers hesitant in decision-making, as individuals always try to be involved in risk-reducing strategies [

26]. However, according to the Trust Commitment theory [

22], trust serves as a mediator between perceived risk and commitment. Trust minimises risk and leads to higher customer commitment [

70]. This concept has been proven in different fields. As analysed by [

70], the influence of green perceived risk on green purchase intention. The analysis found that if consumers perceive high risk or uncertainty, they would be hesitant to trust the product, which in turn negatively impacts their commitment to using the product. Similarly, [

71] used perceived risk theory to show that security concerns reduce users’ trust in mobile commerce, making first-time consumers reluctant to adopt mobile banking. Given the discussion thus far, it is fair to posit the following:

H5. Perceived risk negatively affects commitment to use, and this relationship is mediated by trust.

2.2. Mediator

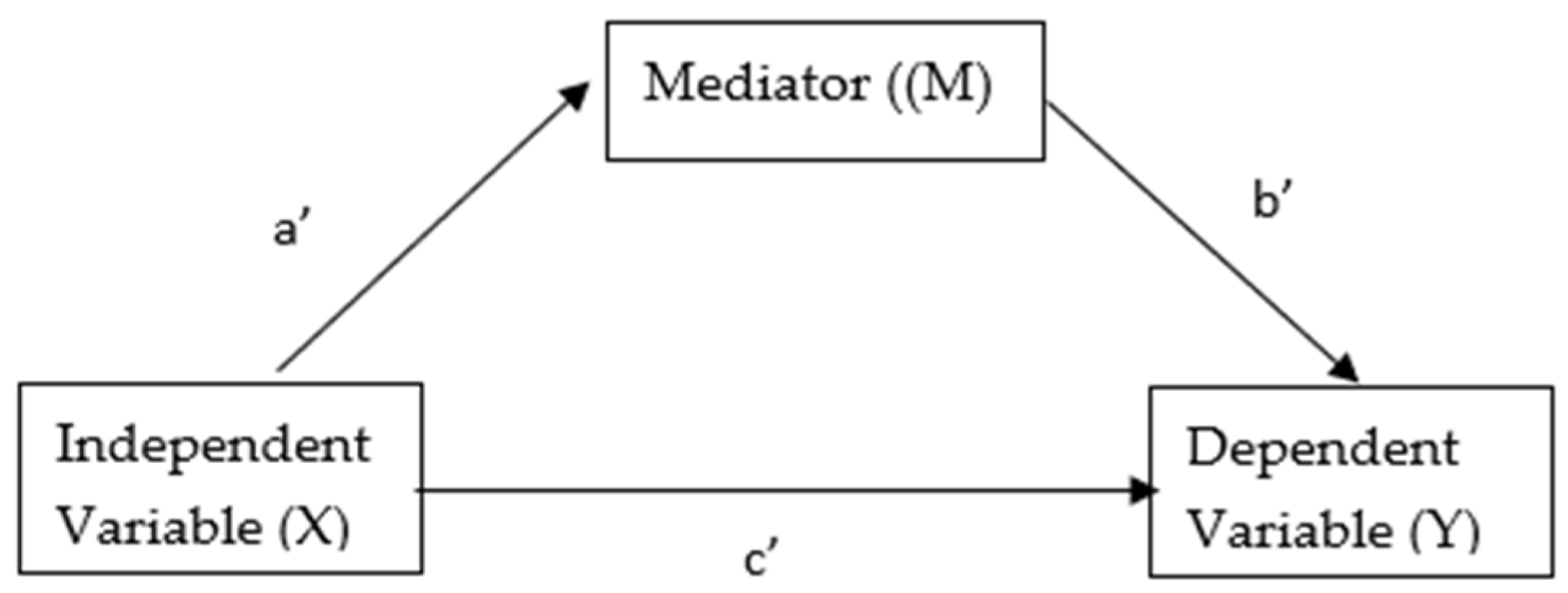

The concept of mediator was introduced by Baron and Kenny in 1986. Baron and Kenny (1986) describe the mediator as an intermediary variable that influences the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. Since then, the concept of mediation has evolved over the years. Nevertheless, the meditation process is a three-variable system where two pathways influence the outcome variable [

72]. One pathway follows from the independent to the dependent variable without passing through the mediator, which is known as the direct effect, and the second pathway follows through the mediator, which is known as the indirect effect. This process is known as the causal chain. The mediator explains how or why such effects are incurred. A variable need to meet three conditions to be considered as an appropriate mediator: (1) changes in the independent variable make changes in the mediator, (2) the changes in the mediator make changes in the dependent variable, (3) when the mediator is reported, the direct relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable becomes weaker and reduce to zero. When the mediator drops to zero, it is considered that the mediator is fully controlling the effect. If the mediator is more than zero, it means that the mediator is affected by the other factors. This concept is summarised below in

Figure 2.

In linear mediation, the total effect of X on Y (denoted as c) decomposes into a direct and an indirect component (see [

72]), where a is the effect of the independent variable (X) on the mediator (M), and b represents the path or effect of the mediator on the dependent variable. Let X be the focal antecedent (service quality, security and privacy, user experience, or emotional attachment), M be trust, and Y be customer commitment using the following formulas.

A mediating variable determines the relationship between independent and dependent variables in a study. It is also known as the intervening variable. Using a mediator variable in the research provides a better understanding of relationships between variables [

71]. Linking a simple mediation model in the context of this study examines the influence of independent variables (service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk) on the dependent variable (commitment) through the mediating effect of trust in digital banking platforms. Using this model, this study examines the direct effect of independent variables on the dependent variables and the indirect effect mediated by trust.

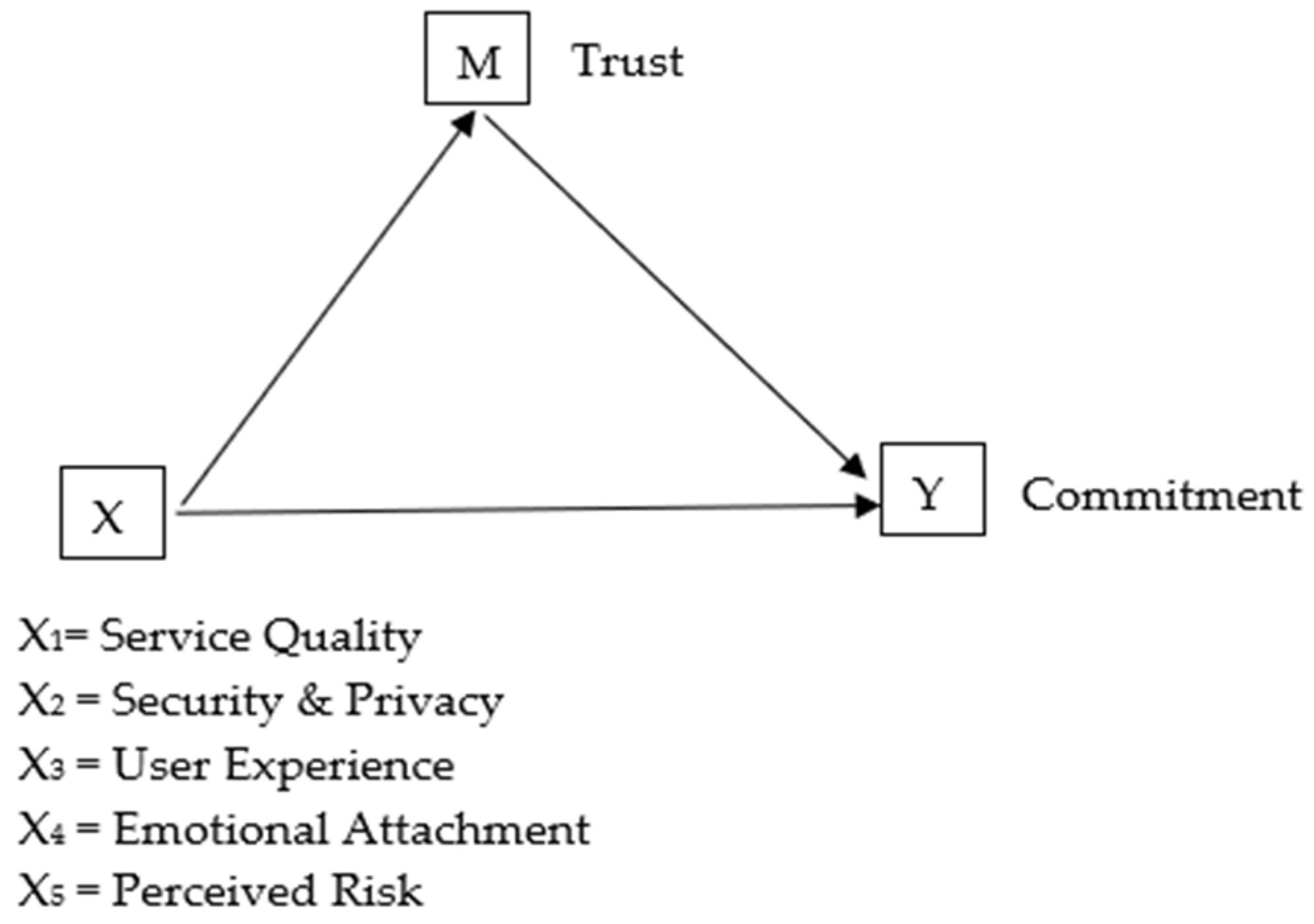

2.3. Research Model

The summary of the research model is shown in

Figure 3. Five independent variables, such as service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk in digital banking, are investigated in this study. Commitment is considered the dependent variable, while trust acts as the mediating role among understudied independent and dependent variables. Using the concept of mediator introduced by [

72], the study examines the direct and indirect effects of service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk on the commitment to use digital banking platforms. Both the direct and indirect effects may influence the total effects.

We used the Macro PROCESS Model 4 [

72] to estimate four separate simple mediation models, one per antecedent, with trust as the mediator and customer commitment as the outcome. Our aim is to quantify and compare indirect effects with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals, which directly addresses the study’s hypotheses. Given the sample size (

n ≈ 111) and mixed convergent validity (AVE < 0.50 for some constructs), a full latent SEM would require additional item refinement to avoid over-parameterisation. PROCESS provides consistent indirect-effect inference under these conditions without imposing a large latent variable structure.

3. Materials and Methods

This study examines the effect of service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk on customers’ commitment to digital banking platforms. Moreover, the study investigates the role of customer trust as a mediating factor in the relationship between independent variables and the dependent variable. To accomplish this, the researcher used a quantitative approach. Specifically, this study collected primary data through an online survey. This technique allows the researchers to conduct a numerical analysis of the study’s posited hypothesis [

74]. We estimated a simple mediation model with trust as the mediator and customer commitment as the outcome. The predictors were service quality, security and privacy, user experience, and emotional attachment. We used bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals with five thousand resamples and an alpha of 0.05. This approach allows a direct comparison of the indirect effects from each predictor through trust.

Examining the strength of relationships between variables using quantitative survey research provides a numerical explanation of the opinions and trends of a selected population. Then the researcher can comprehend the wider picture related to a larger population [

75]. This study selected a cross-sectional design to gather data from participants at one point in time using an online survey technique. This method assists the researcher in collecting data effectively across a wider geographical area while ensuring the anonymity of the respondent [

76].

3.1. Research Setting and Sampling Frame

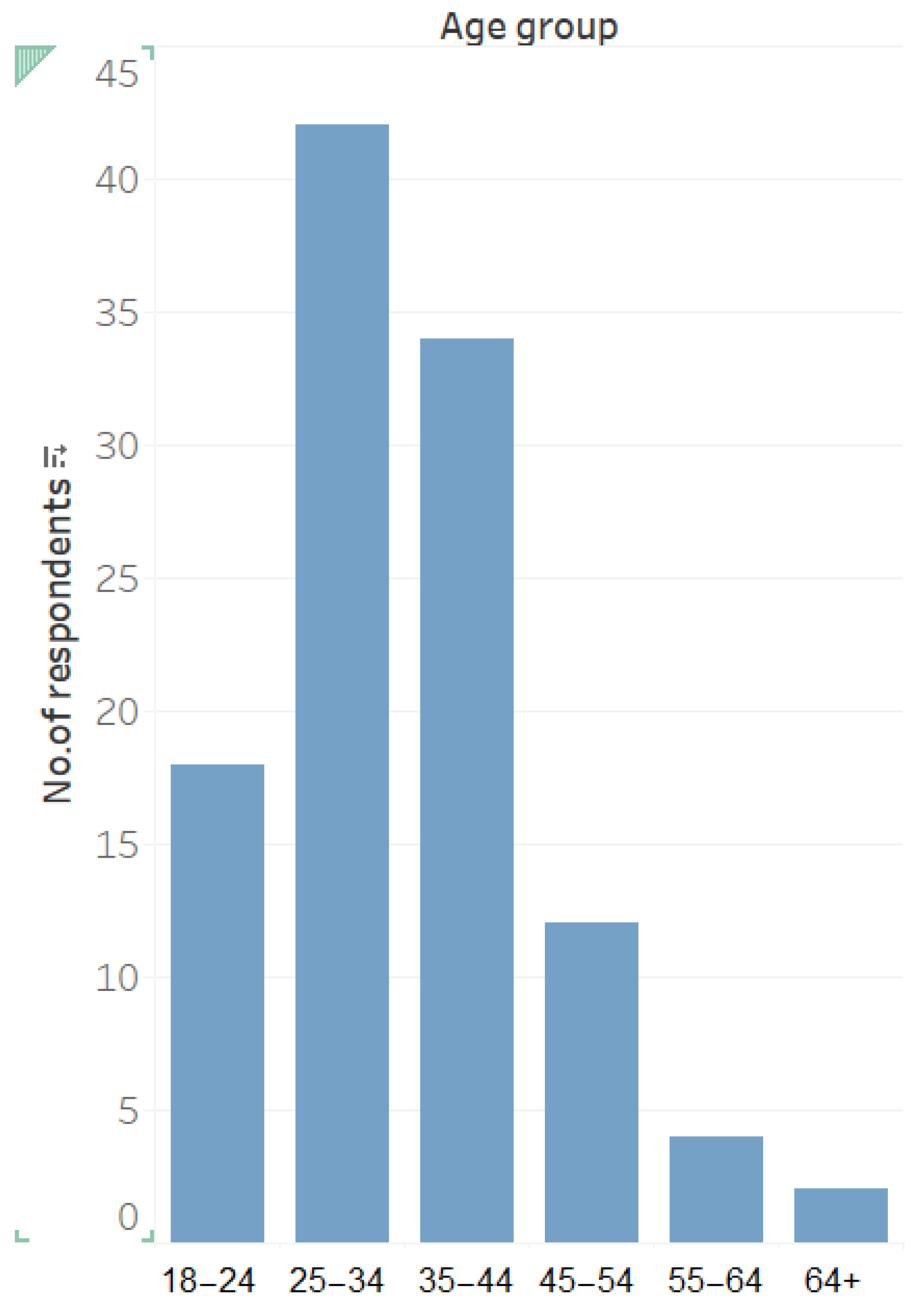

This study focused on individuals residing in New Zealand who have a bank account and experience using digital banking platforms. This study involves participants aged 18 and above. The type of banking experience can be either personal or business. Before gathering data, the study obtained ethics approval from the WelTec/Whitireia Ethics Committee in July 2024 to guarantee that the research followed ethical standards and to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

Data collection commenced on 13 August 2024 and continued for three weeks through convenience sampling. This study used the SurveyMonkey Platform to create the survey template and shared the link on public social media, personal social media, and other social media groups belonging to friends and family members (Facebook, LinkedIn, and WhatsApp). The link was also shared among participants via email.

3.2. Sample Size

When conducting a study, identifying the sample size is important as it affects the reliability and accuracy of the results. A well-calculated sample size ensures the appropriate statistical power to accurately represent the population of the study [

73]. Statistical power analysis is directly related to the formulated hypothesis. Statistical interpretation allows the researcher to identify the acceptable level of sampling errors [

77]. While testing the hypothesis, the researcher performed two types of errors such as Type I (false positives) and Type II (false negatives).

Type I errors are also known as alpha (α) errors; it is the possibility of rejecting a null hypothesis when it is true. It is also known as a false positive. The threshold for an acceptable alpha value is 0.05, which means there is less than a 5% chance that the data being tested would fall under the Type I error category [

77]. Moreover, the power of this study is 1-β and set as 80%, which shows the probability of identifying the true effect of this study while avoiding Type II errors [

78]. This study used the sample size calculator to identify the proper sample size. We obtained 112 responses; one with missing data was excluded, leaving 111 complete responses for analysis. Type 1 error (α) = 0.05 (two-tailed) and at an 80% confidence level, the maximum margin of error is ±6.07%; at the conventional 95% level, it is ±9.3%. Minimum detectable standardised indirect effect (MDIE): ≈0.12 (indirect = 0.1225). This corresponded to a = b ≈ 0.35 in the equal-paths assumption.

3.3. Study Measures

The study adopted widely established scales to investigate the understudied variables and assess the formulated hypothesis. The understudied variables are service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk. There are 28 structured questions in total, including four demographic questions of age, gender, annual income and usage tenure. The study used demographic attributes to identify and compare the characteristics of respondents. All scales were measured using a 5-point Likert scale; 1-being the Strongly Disagree, 2-Disagree, 3-Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4-Agree, 5-Strongly Agree.

Service quality was measured using the scale provided by [

79]. The scale has four items, including ‘I can log on to my bank website quickly and easily’. The study used scale to measure the variable Security and privacy [

49]. The scale has four items, including ‘I trust my bank’s digital services’. Items for user experience were adopted from scale provided in [

80]. Similarly, the measure has four items: ‘Learning to use an online banking platform is easy for me’. Emotional attachment has a three-item scale, adopted from measurement scale [

60], including ‘I am proud to be a customer of my bank’. Perceived risk was measured using the scale proposed in [

69]. Similarly, the scale has three items: ‘In my opinion, there is a risk of fraud while using Internet banking services’. Moving to the mediating variable, the study used the scale to measure customer trust [

31]. Sample items include ‘I believe that online banking is trustworthy’. Finally, moving to the dependent variable, customer commitment was measured using a three-item scale by [

81]. Sample items include ‘I will recommend digital banking platforms to other people’. The summary of the scale is depicted in

Table A1.

3.4. Reliability Test

Reliability measures the extent to which the understudied variables are accurate in value and free from error [

77]. More reliable measures reveal greater consistency than less reliable measures. One method of checking reliability is the test–retest, which will ensure the consistency of responses at two points in time [

77]. Therefore, the reliability of this study was measured using two methods: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Cronbach’s Alpha (α).

Before computing any inferential statistics, the researcher conducted an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to determine whether the data met the basic assumptions for statistics [

74]. This study used the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) extraction method to determine the factor loadings for each item. Statisticians suggest that any item which has a lower factor loading value than 0.4 is weak and insignificant; therefore, it needs to be removed from further analysis to maintain the validity and reliability of the measures. [

81,

82]. Following that suggestion, one, item UE1 was removed due to low loading from further analysis.

We assessed internal consistency and convergent/discriminant validity using Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (formula provided) and Cronbach’s α [

77]. As guidance, AVE ≥ 0.50 supports convergent validity; α ≥ 0.70 supports internal consistency [

83].

When calculating the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for understudied variables, Emotional Attachment (EA), Perceived Risk (PR), and Customer Commitment (CC) have AVE values above the threshold of 0.5, indicating acceptable levels. At the same time, variables like Service Quality (SQ), Security and Privacy (SP), adjusted User Experience (UE), and Customer Trust (CT) fall below the threshold of 0.5, which cannot be accepted and needs further investigation to strengthen the validity. Given AVE < 0.50 for some scales, we interpret structural paths conservatively and base inference on bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. We emphasise indirect effects (via trust) rather than relying on point estimates alone. We further assess potential method bias (CMB) by conducting Harman’s single-factor test. An unrotated exploratory factor analysis of all measurement items revealed that the first factor accounted for 35.96% of the variance, which is well below the 50% threshold. This suggests that common method bias is unlikely to be a major concern in this study.

Finally, the study tested the reliability of the scale by assessing the F Cronbach’s Alpha (α) reliability test to examine the consistency level and measurement dimensions between the used variables [

84]. The Cronbach’s Alpha (α) value of 0.7 or above shows strong internal data consistency. Any item with Cronbach’s α less than 0.7 shows that the used scale items are unreliable [

85,

86]. Finally, the results of the study show that all Cronbach’s Alphas range from 0.7 to 0.8, indicating acceptable internal reliability. The Cronbach’s Alpha of user experience was above the accepted limit at 0.730, indicating the consistency of the data. The summary of Cronbach’s Alpha EFA results is shown in

Table 1.

5. Discussion

The following is the summary of outcomes as summarised in

Table 8.

5.1. General Discussion

With the emergence of digital banking, the banking industry has become highly competitive. This study analyses the effect of service quality, security and privacy, user experience, emotional attachment and perceived risk on customers’ commitment to digital banking platforms. Interestingly, bootstrapped indirect effects are significant, confirming that customers’ trust mediates the impact of the independent variables on commitment (indirect β = [value], 95% CI [lower, upper]). The results of the study reveal that the customer’s trust drives the customer’s commitment towards digital banking platforms. It confirms that when customers trust the digital banking platform, they become more committed to it. Therefore, this finding aligns well with the past studies. Security and privacy, as well as emotional attachment, significantly affect both trust and commitment. This means that when customers feel secure in their financial transactions, they trust the platform and remain committed to it. Similarly, when customers feel emotionally connected with digital banking platforms, they are inclined to trust the platform and remain committed.

5.2. Theoretical Implication

This study used trust as a mediator between independent variables and customer commitment. The result of this study appears to affirm the Trust Commitment Theory [

22]. Trust and commitment theory posits that trust and commitment play a vital role in the relationship between the business and customers. According to the theory, trust allows customers to feel secure and lower uncertainty and perceived risk, and building confidence leads to greater customer commitment. This trend is observed in this study: customers who trust digital banking platforms appear to remain committed. Banks build trust in customers by guiding them with clear and concise information to perform transparent and honest financial deals. When customers trust that banks fulfil their requirements, they remain committed to the relationship. This result also aligns with several previous empirical studies that have demonstrated the positive relationship between trust and commitment [

36,

82,

87].

According to the results of this study, the direct impact of service quality and user experience on trust is weak, although both variables significantly impact commitment through customer trust. This finding has challenged previous theoretical studies that discussed the direct relationship between service quality and trust. While the SERVQUAL model [

25] focuses on key dimensions of service quality (reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy and tangible), it minimises uncertainty and builds trust. This connection has already been discussed in previous studies [

4]. This study highlights that good service quality does not directly build trust, yet it improves customer satisfaction for a long-term commitment. Trust acts as a mediator to bridge the gap between high customer satisfaction and commitment [

87,

88].

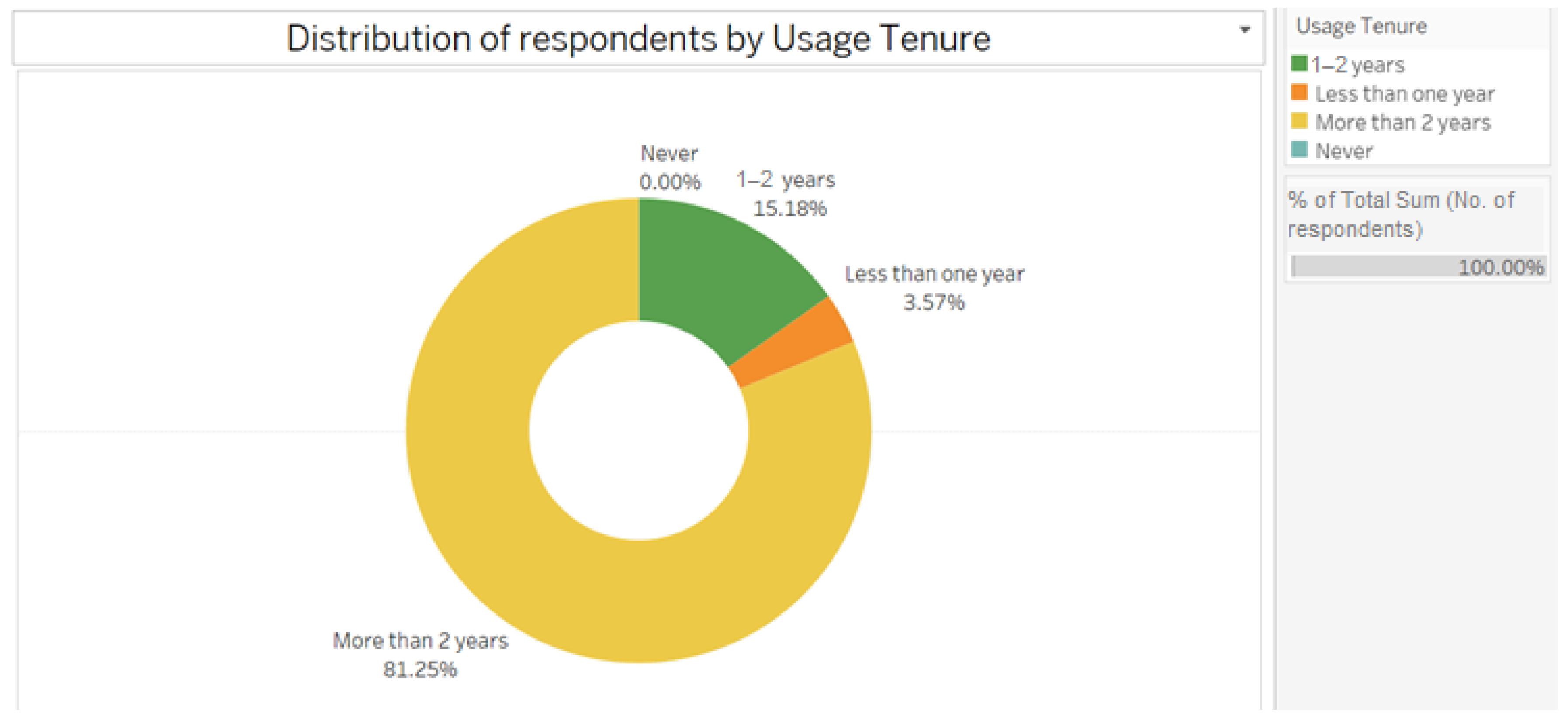

The study has demonstrated that security and privacy affect customer commitment positively, and the customer’s trust mediates this relationship. Focusing on commitment changes the pattern of results. Security, privacy, and emotional attachment show the largest overall effects on commitment. Service quality and user experience act mainly through trust. This suggests that retention depends on assurance and affect as well as on interface quality. Perceived risk does not show an indirect effect through trust in this sample. A likely reason is the high level of user experience and a normalisation of basic security practices. This points to a boundary condition. In mature settings with experienced users, reducing perceived risk further may not increase commitment.

Strong security and privacy measures of digital banking platforms stimulate customers’ trust, which leads to enhanced long-term commitment. This relationship has been explained in previous empirical studies [

48,

50]. This study has also observed that emotional attachment significantly affects customer commitment, and this relationship is mediated by trust. Both direct and indirect effects are significant. This result supports the Trust Commitment Theory [

22], which explains that customers who are emotionally attached to digital banking platforms build trust and are more likely to remain committed. The results highlight that digital banking platforms need to consider the technical features and build emotional attachments with banking customers. Moreover, these results also align with several other previous empirical studies that have discussed the relationship between emotional attachment, trust and commitment [

71].

Interestingly, contrary to the prediction, this study found that perceived risk does not significantly affect trust and commitment. This result contradicts past empirical studies, which consider perceived risk as a major obstacle to adopting and trusting digital banking platforms [

36,

69]. The results of this study reveal an insignificant effect of perceived risk, likely because all individuals had experience in using digital banking platforms. Since they have experienced digital banking for a long time, customers consider that the security protocols used by banking platforms are sufficient. When linking these findings to Perceived Risk theory [

26], customers’ willingness to adopt the new technology lies with financial, privacy and security risks; therefore, minimising these perceived risks encourages customers to trust and commit towards technology.

Lastly, our recommendations align with international evidence indicating that ease-of-use, privacy, and security features build trust and support continued use (see

Table A2; [

89,

90,

91]). Moderator patterns reported in multi-country work also suggest tailoring by user experience level and demographics [

92].

5.3. Managerial Implications

This study provides valuable insights to banking managers, decision-makers in the banking industry, academic researchers and policymakers who are interested in understanding the effect of service quality, security and privacy, emotional attachment, user experience and perceived risk on customer trust and commitment in the digital banking sector. Retail banks need to build and maintain a strong customer base to generate profits and remain competitive.

First and foremost, managers need to understand the importance of trust and commitment in digital banking. Trust is considered the basis for a long-term relationship between customers and the business. Especially in digital banking, which involves sensitive personal data related to customers. Therefore, bank managers need to ensure that appropriate measures are taken to protect customer data across all touchpoints. This leads to enhancing a trustworthy digital environment for customers. When a customer trusts the platform, they are more likely to commit to it. This relationship is a vital concern in managerial decision-making in digital banking platforms. Banking managers and decision-makers need to understand that trust and commitment are built over time through effective management. Managers need to recognise the importance of robust service quality on digital banking platforms. Ease of use, transaction speed, security, and user-friendliness are features of high service quality that increase customer trust and commitment. It is necessary to enhance the service quality in the digital banking sector as it directly impacts the loyalty and long-term profitability of the company. Managers should improve service quality in a way that will meet or exceed customer expectations to attract and retain more customers towards the business [

93]. Furthermore, managers may need to invest in advanced technology to ensure streamlined, high-quality service delivery to customers. As a result, customer satisfaction and business efficiency increase. Maintaining superior service quality is a salient factor which allows bank managers and other decision-makers to strengthen the brand image, leading to enhanced customer commitment [

50]. Therefore, enhancing service quality would retain customers in the digital banking platform, which leads managers to improve both profitability and market share.

Banks can promote digital banking platforms among customers by developing a secure and privacy-centric system for financial services. Consumers consistently perceive credible and trustworthy platforms. Therefore, bank managers need to design their digital platforms to ensure security strategically. A properly secured banking system detects suspicious transactions using machine-learning techniques and discards them to protect the sensitive data of customers. Moreover, maintaining financial transaction security involves regular auditing and communicating privacy policies transparently with customers. Having a deep understanding of customers’ sensitive data is essential for managers to tailor financial services according to customers’ security expectations [

50]. By safeguarding customer data, banks build trust, leading to long-term commitment towards the platform.

Advanced technology in the banking sector has introduced new approaches to addressing user requirements. User experience has become the key feature of human–computer interaction [

54]. Enhancing user experience has become an essential factor for bank managers. Therefore, bank managers and other decision-making professionals always try to customise the available digital banking platforms according to customer requirements using personalised financial management tools to enhance the user experience. Digital banking offers both functional and emotional values to its users. Technical benefits like speed, efficiency and convenience provide functional values, while users enjoy the emotional value of a pleasant and satisfying user experience. Customers always prefer to use fast, easily navigated, user-friendly omni-channels to perform their banking activities [

7]. Therefore, managers need to offer a better experience to their customers in digital banking, which fosters trust and commitment to use the same product in the future.

The study results highlight that fostering an emotional bond between the digital platform and the customer is a vital factor for long-term success. Bank managers and other decision-makers in the banking sector must offer user-friendly, reliable, consistent and personalised digital banking experiences to build emotional attachments with their customers. Bank managers can offer tailored products according to customer preferences, reply to customer concerns swiftly and organise reward programmes to make customers feel that they are valued and appreciated by the banks. As a result, customers will develop a strong emotional attachment to digital banking platforms. This positive emotional attachment would lead to a positive impact on customer trust, which would affect the adoption and engagement of the service. When customers trust an emotionally attached digital banking platform, they will commit to using the platform for a long time. Therefore, managers’ responsibility is not only to focus on providing a secure, high-quality, user-friendly digital banking platform to their customers but also to engage with their customers emotionally by offering a positive, personalised experience for them. These emotionally driven relationships will also deepen long-term commitment.

Finally, this study found that perceived risk does not have any significant impact on customer trust and commitment to digital banking platforms. Although the perceived risk is considered a barrier in a digital environment [

34], this study does not prevent customers from trusting and committing towards digital banking services. However, managers should not ignore this factor, as customers are constantly concerned about the security of financial transactions and the privacy of financial data before engaging with digital services. Therefore, bank managers need to focus on addressing or minimising the perceived risk to safeguard their customers. Managers can offer a user-friendly platform and educate their customers constantly to avoid these risks. When customers feel that they are secure while using the platform, they build trust and commitment.

5.4. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Four main limitations could hinder the process of achieving the research goal. First, this study assesses the personal opinions of respondents using self-reported data. The social desirability bias may cloud the result. Nevertheless, the study has employed cautious processes by using established scales and testing their reliability. Moreover, this study focuses only on the New Zealand digital banking context; therefore, examining the research in different countries may (or may not) provide different results because of various cultural domains and regulatory environments towards digital banking. Subsequently, testing the model in other countries is also essential.

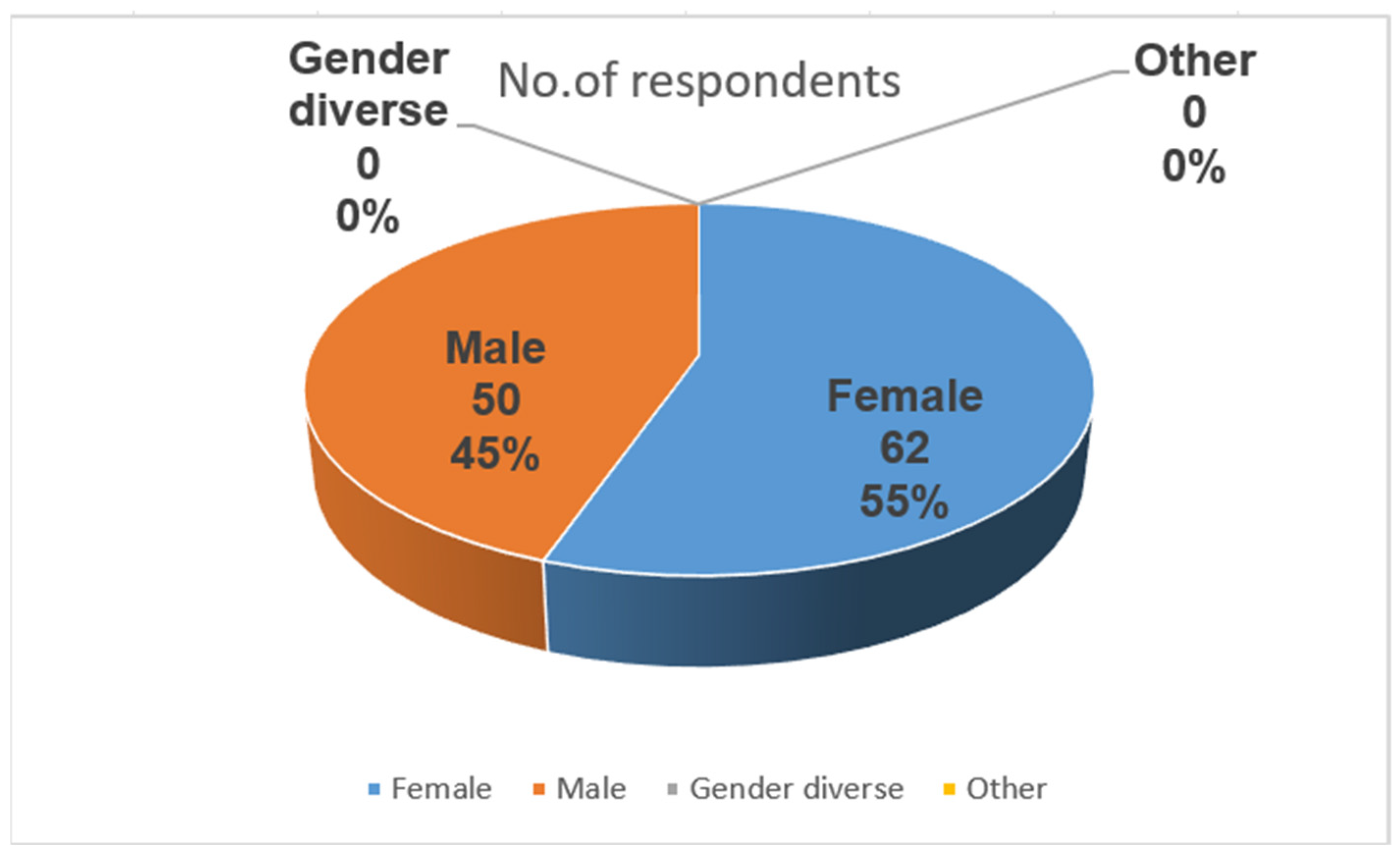

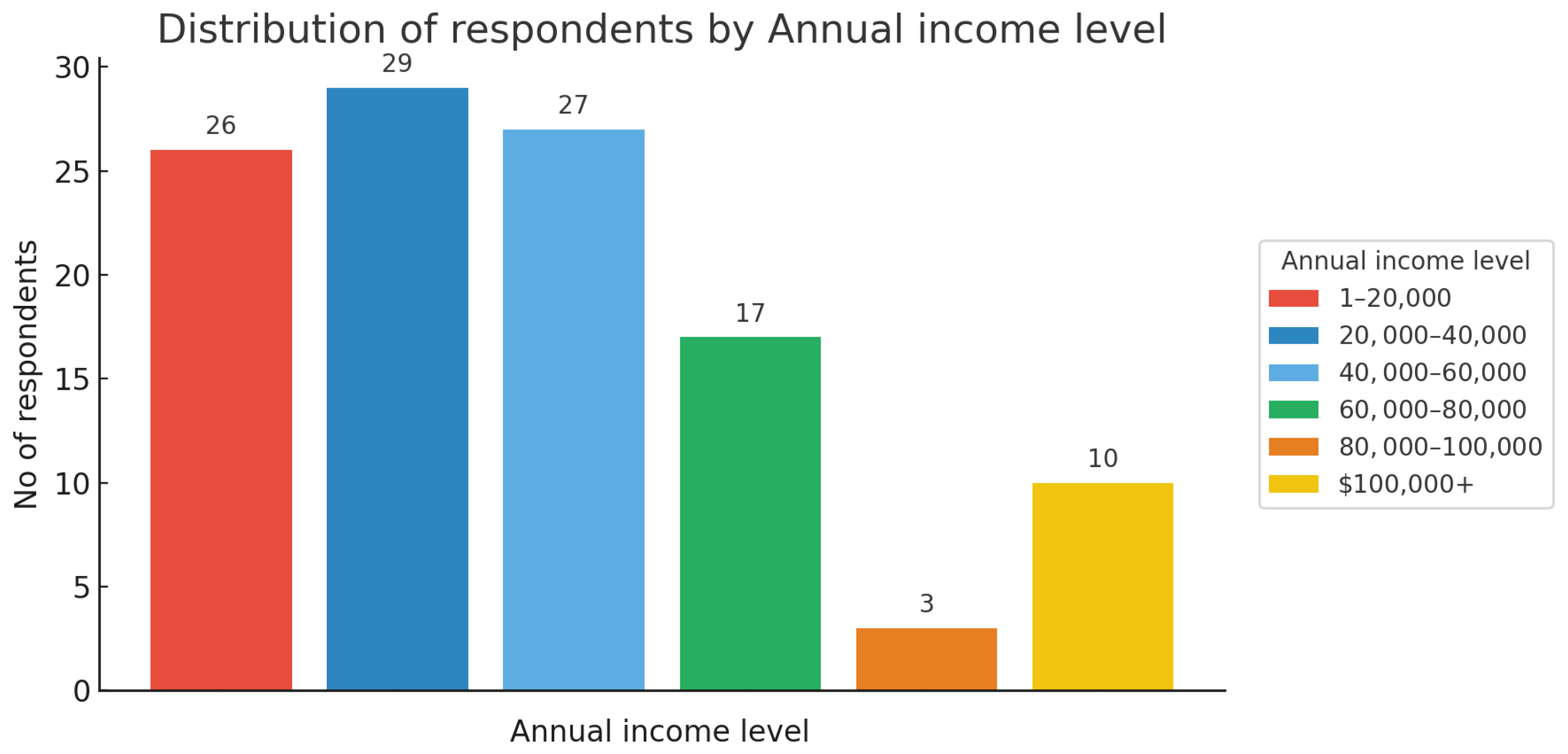

Moreover, the study used a relatively small sample size of 111 respondents with a confidence level of 80% and a margin of error of greater than 0.05. Future studies could aim for a larger sample size to reduce the margin of error and to increase the confidence level of the result. Data was also collected through convenience sampling and this may prone to selection bias and overrepresent by certain group. We minimised this bias by ensuring that participants were balanced across age groups and fairly represented by both genders. Third, from the methodological perspective, the variables in the study have been used on a first-order scale, including service quality, security and privacy. Previous empirical studies have used service quality as a second-order factor, encompassing subdomains such as responsiveness, assurance, and reliability [

94]. Similarly, previous empirical studies have discussed security and privacy as a second-factor order measure, encompassing subdomains such as digital security and data privacy [

95,

96]. Therefore, future studies could bridge this gap by including several other subdomains in their research.

Building on our findings, we suggest a pragmatic focus on trust-by-design. First, implement risk-based authentication that asks for extra verification only when risk is elevated, which preserves day-to-day usability while maintaining appropriate security controls. Second, run trust-centred usability evaluations with demographically representative users in Aotearoa New Zealand, including those for whom English is a second language (Te Reo Māori or other ethnicities), and report pre–post changes in task success, abandonment, and validated trust measures to show what actually improves. Third, provide a transparent, user-controllable data-use dashboard that states what data are stored, where, and for how long, and that enables granular consent, revocation, and export. We anticipate that this combination will reduce perceived risk, strengthen trust, and, in turn, support ongoing commitment to digital banking.