Numerical Simulation of Liquefaction Behaviour in Coastal Reclaimed Sediments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil and Testing Procedure

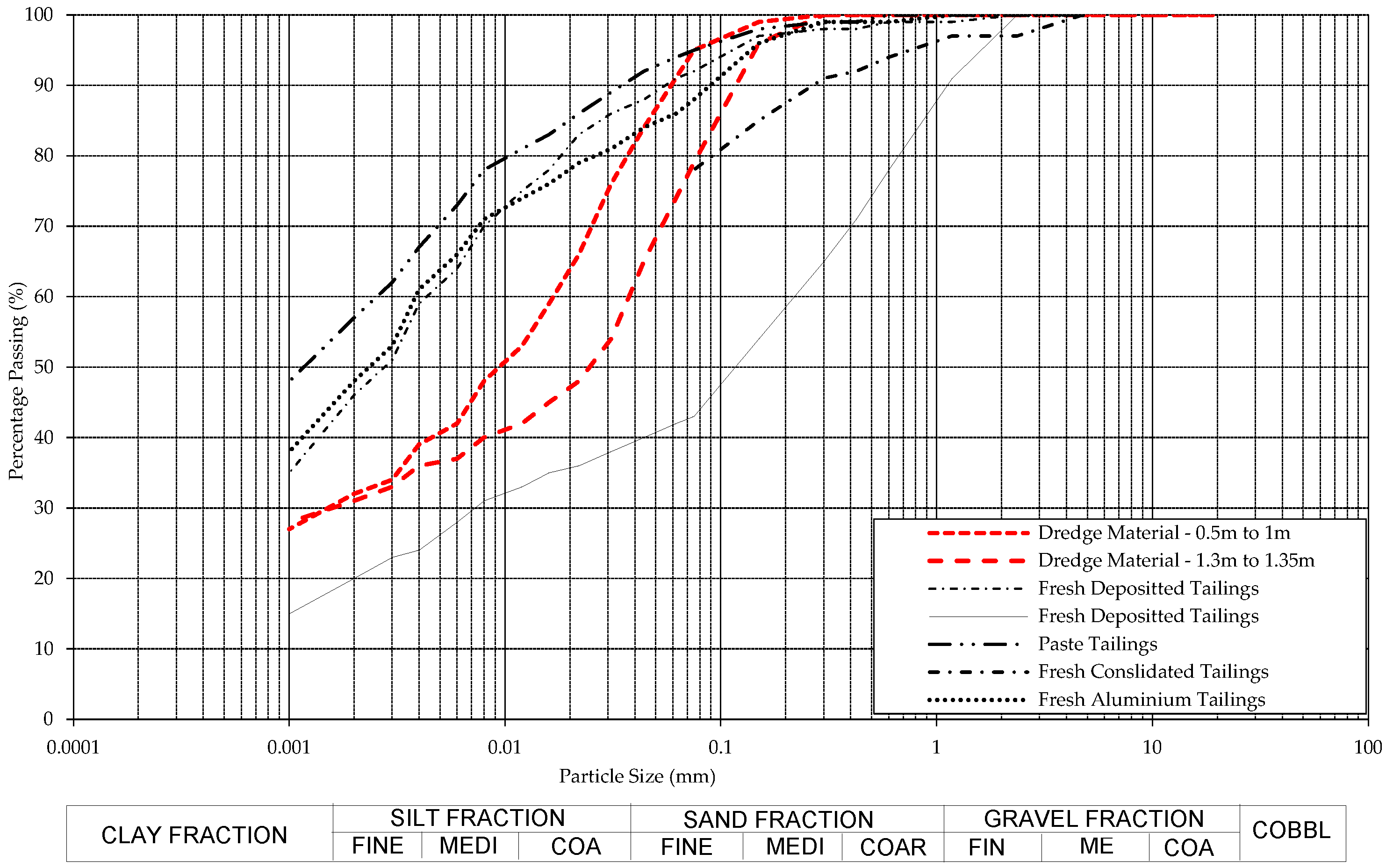

2.1.1. Reclaimed Material Description

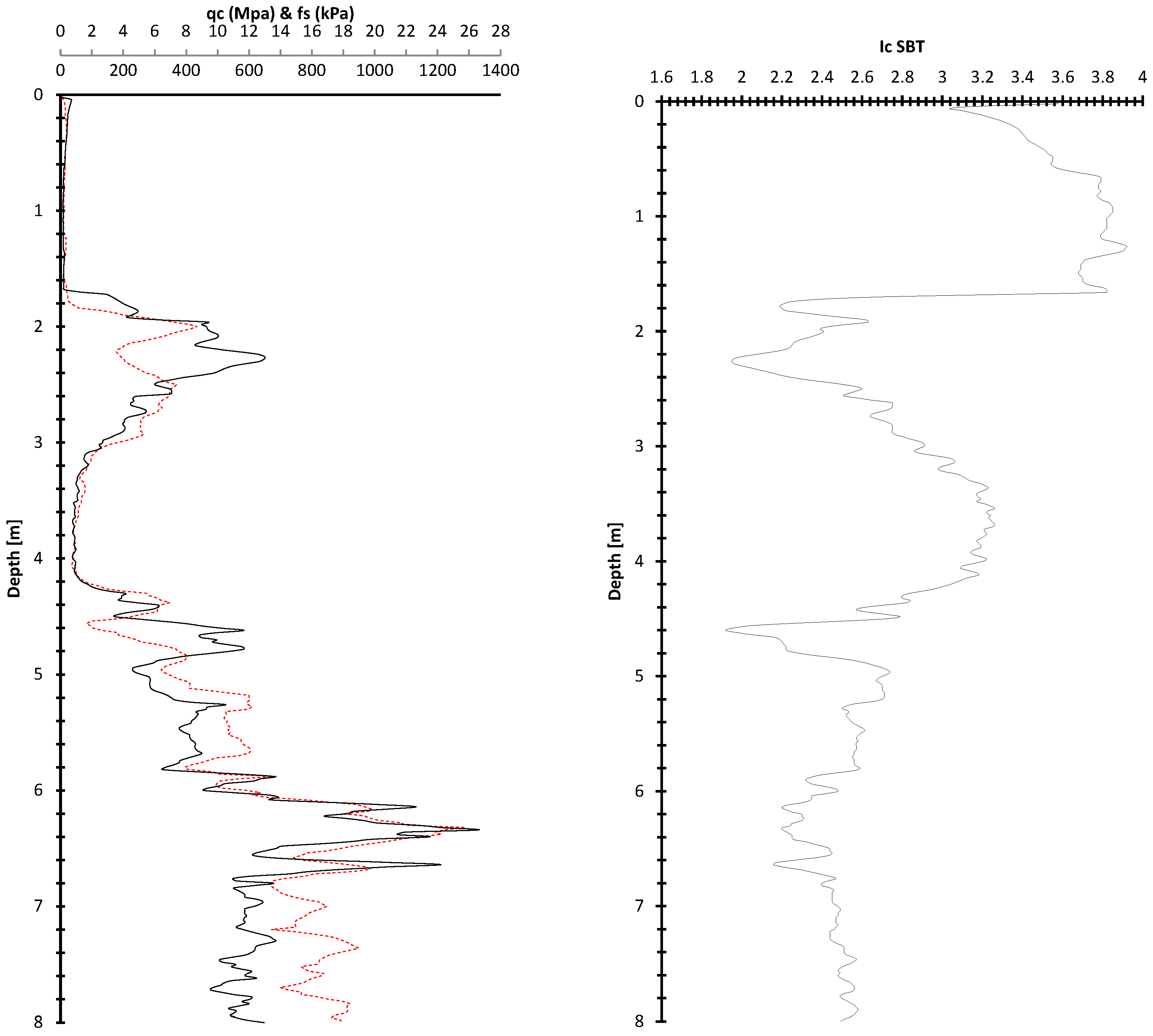

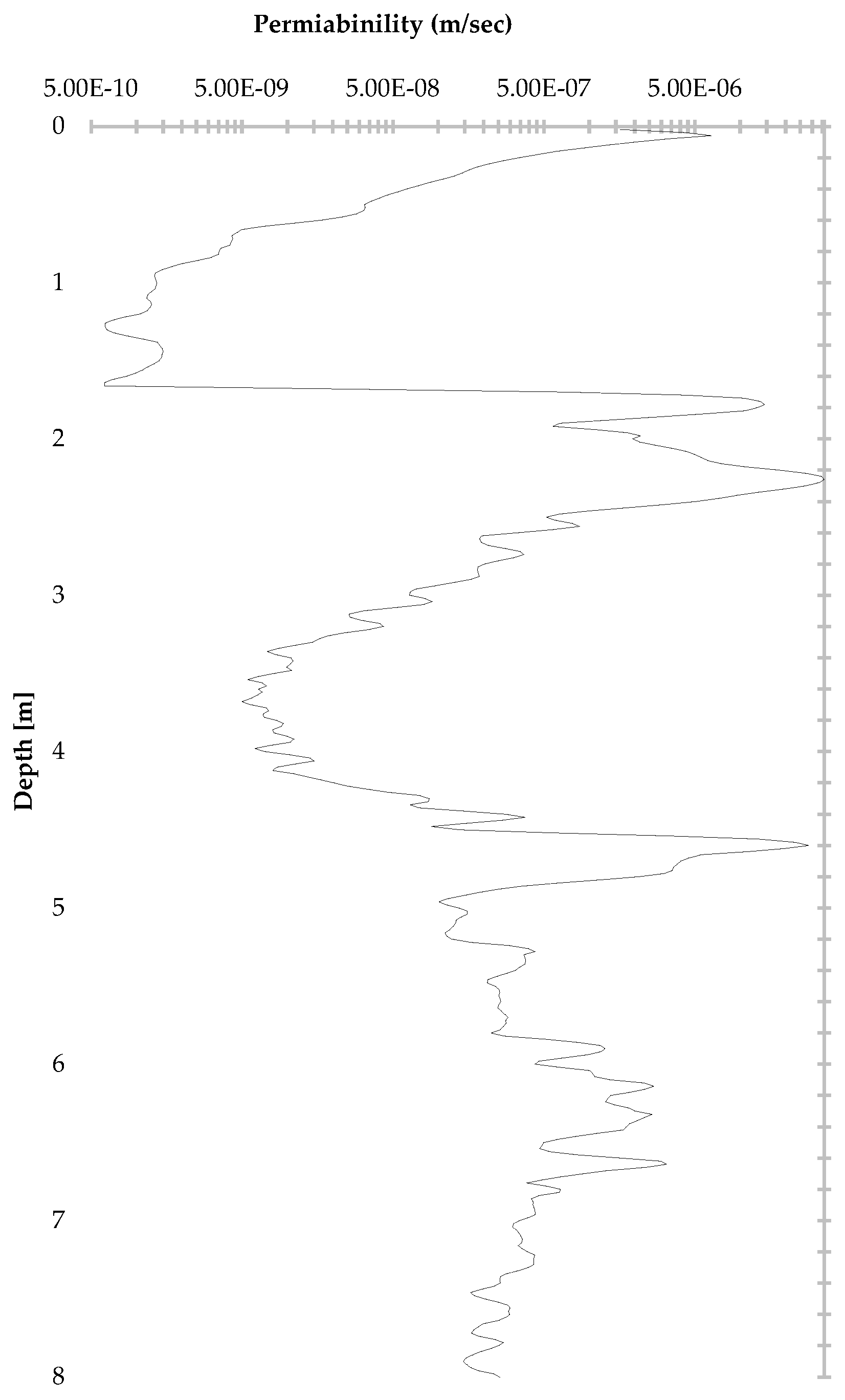

2.1.2. CPTu Interpretation and Permeability Estimation

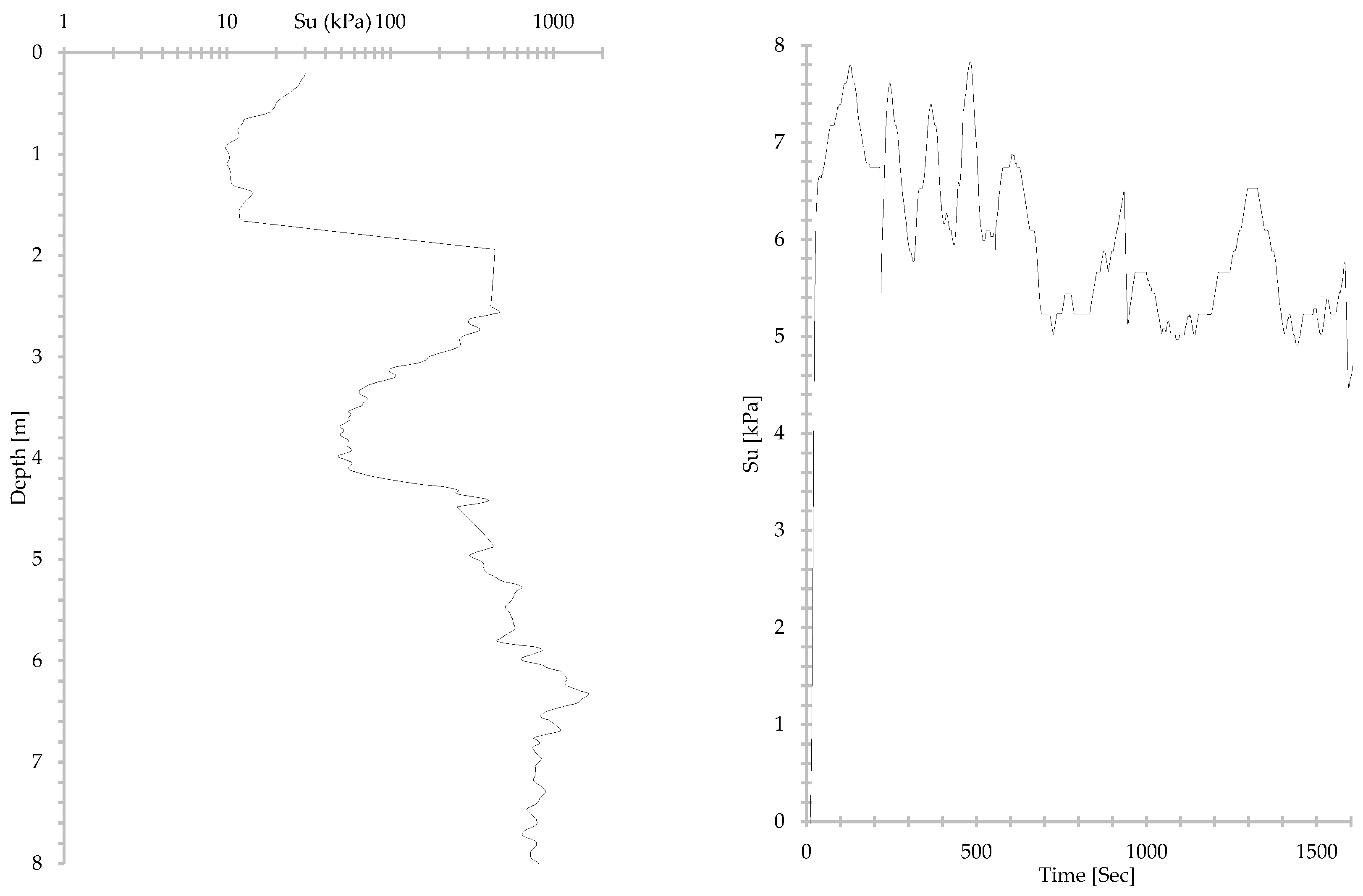

2.1.3. Undrained Shear Strength from CPT and Vane Shear Test

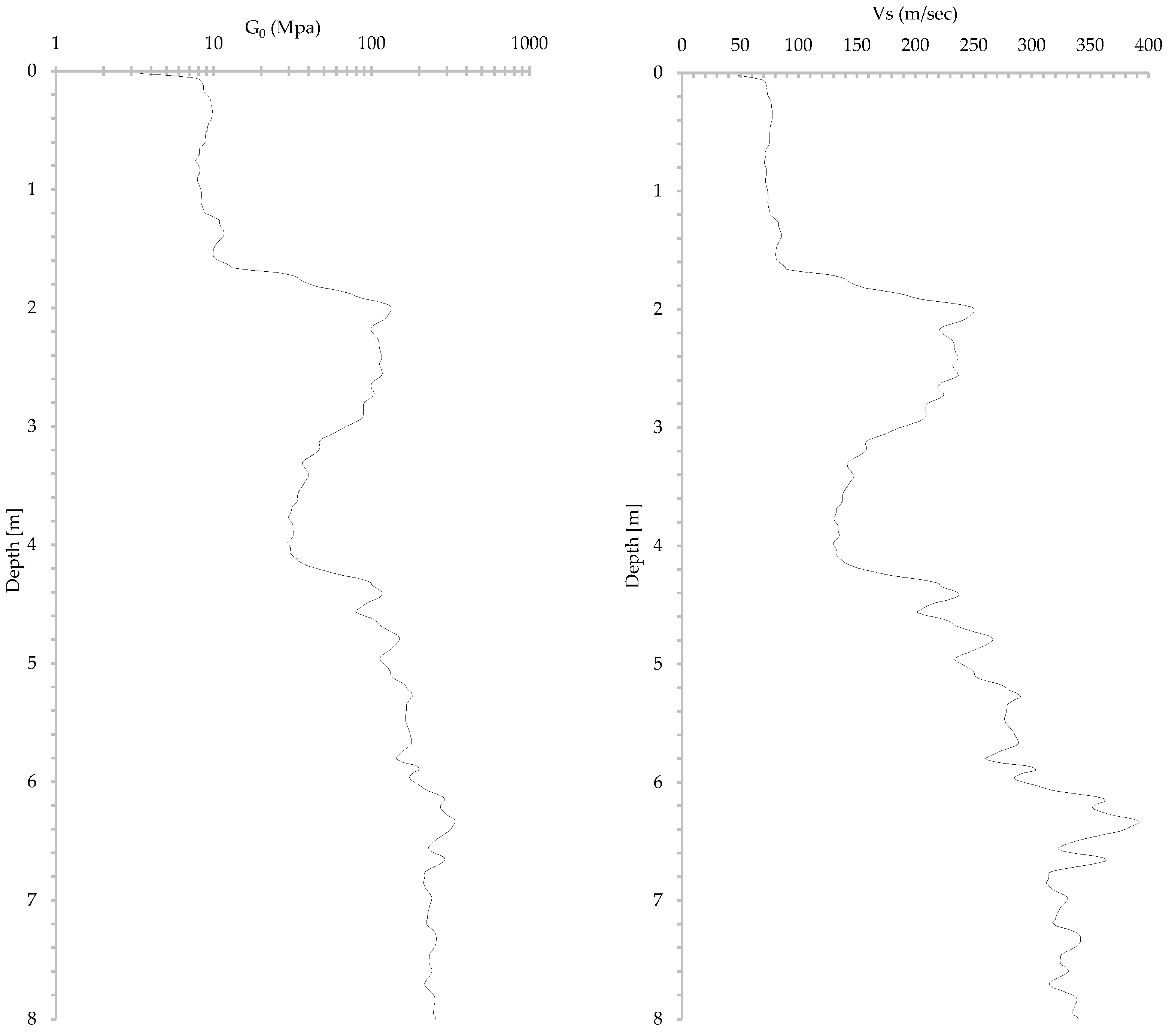

2.1.4. Shear Wave Velocity and G0 Calibration

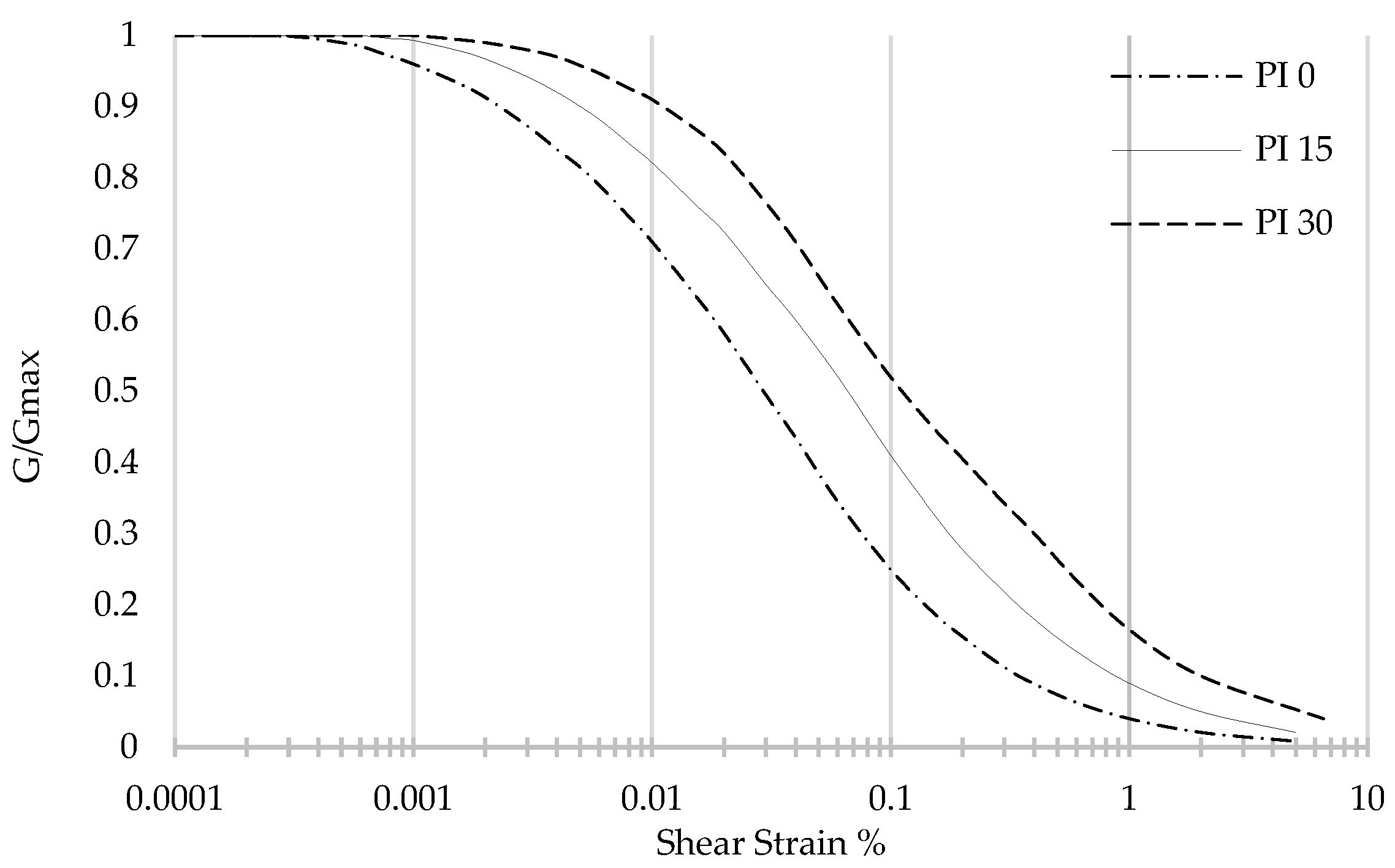

2.1.5. Strength Reduction and Cyclic Degradation Modeling

2.2. Numerical Model Setup

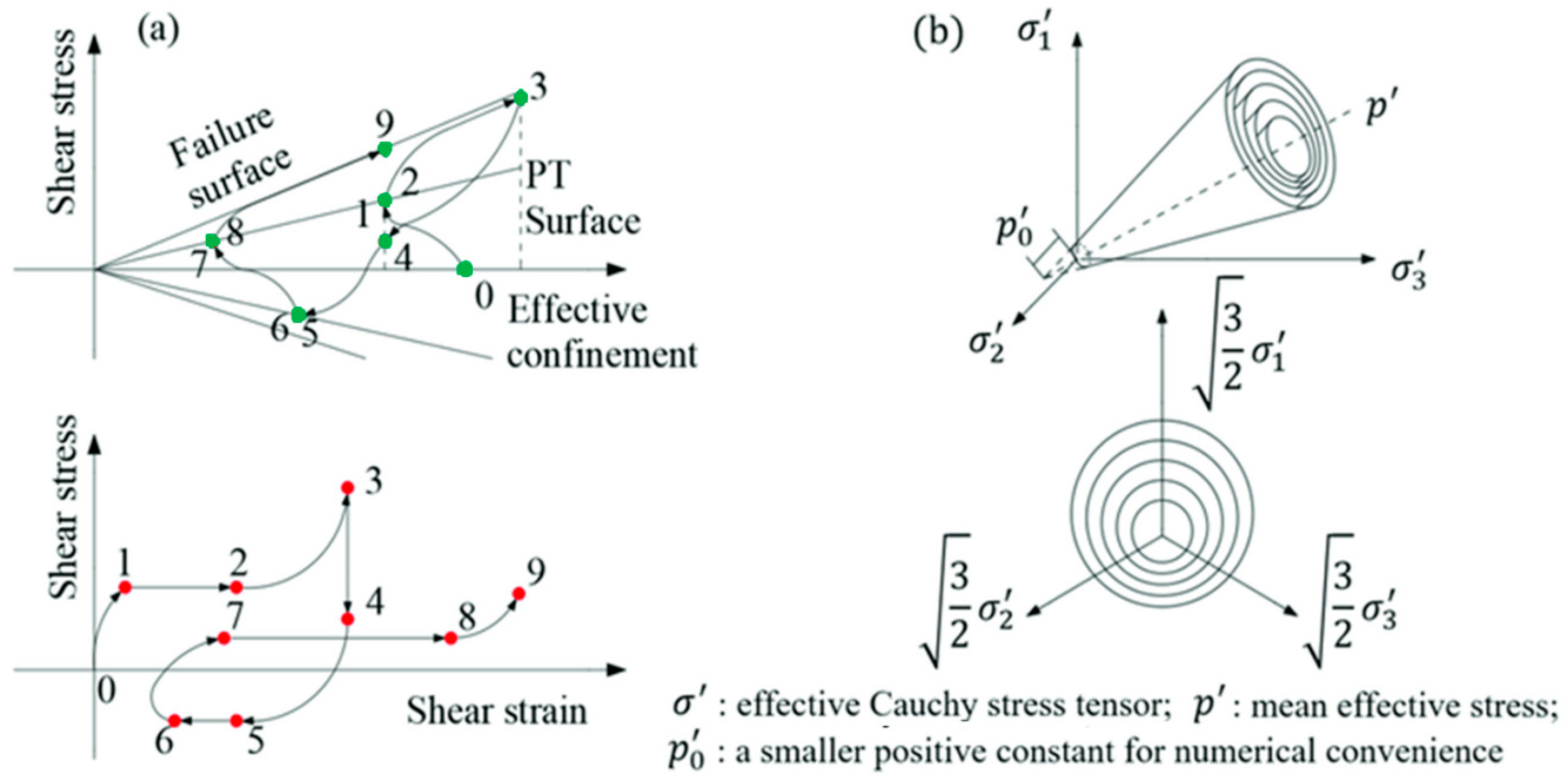

2.2.1. Constitutive Model

2.2.2. Numerical Analysis

2.2.3. Analysis Options and Numerical Configuration

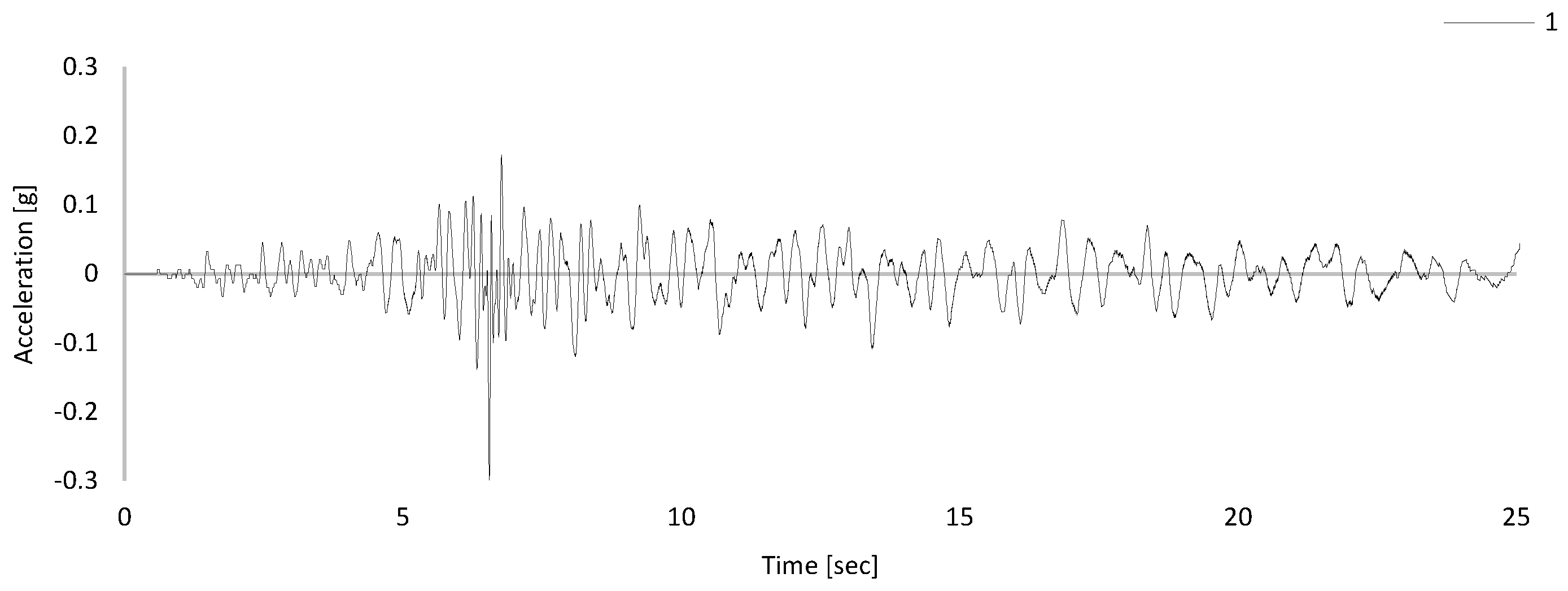

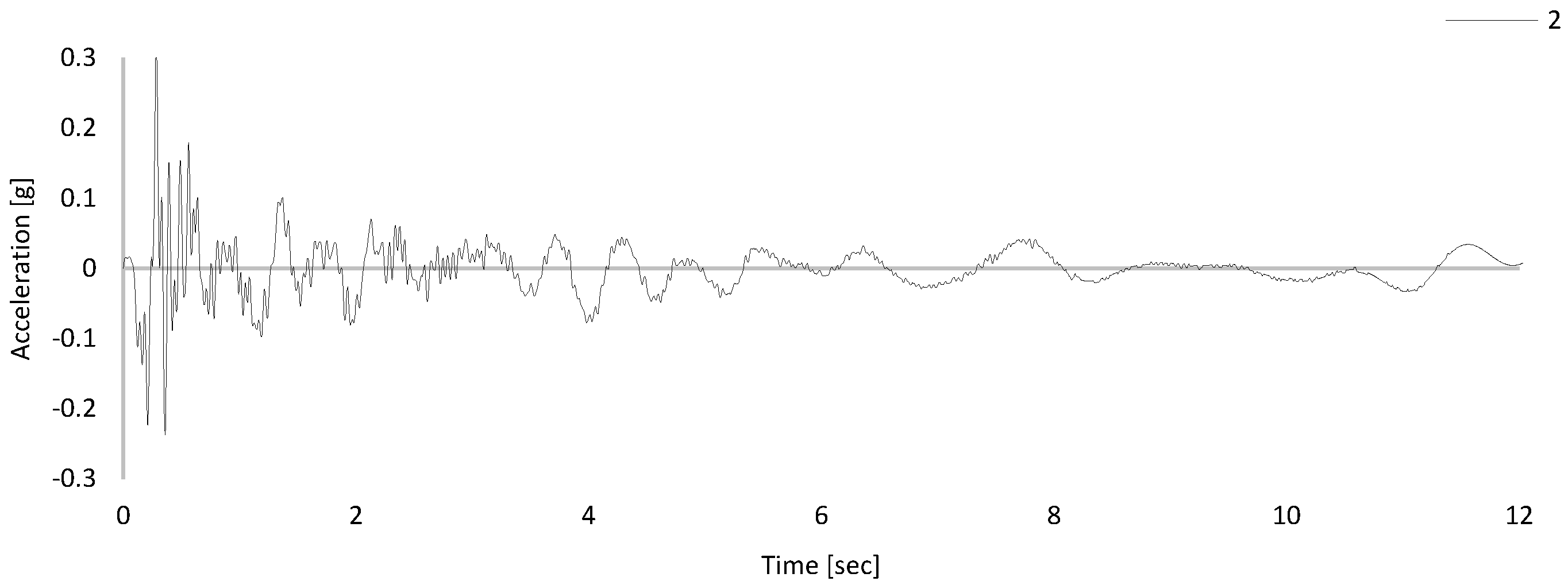

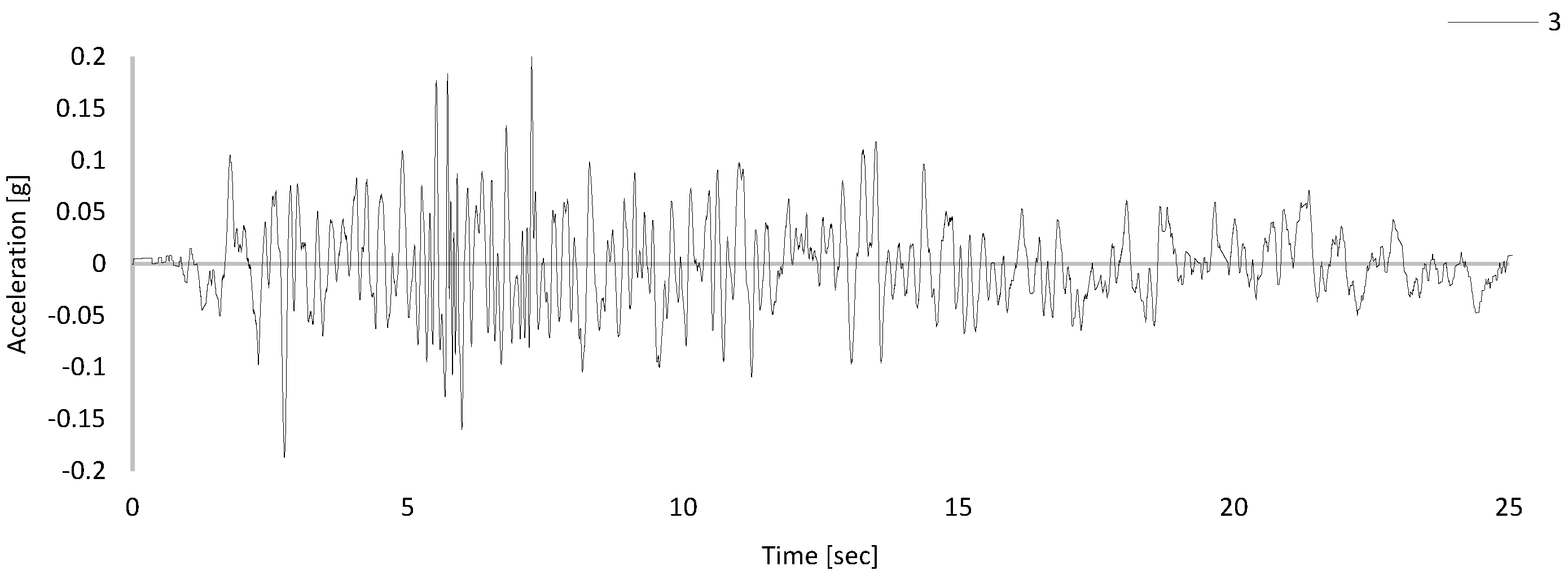

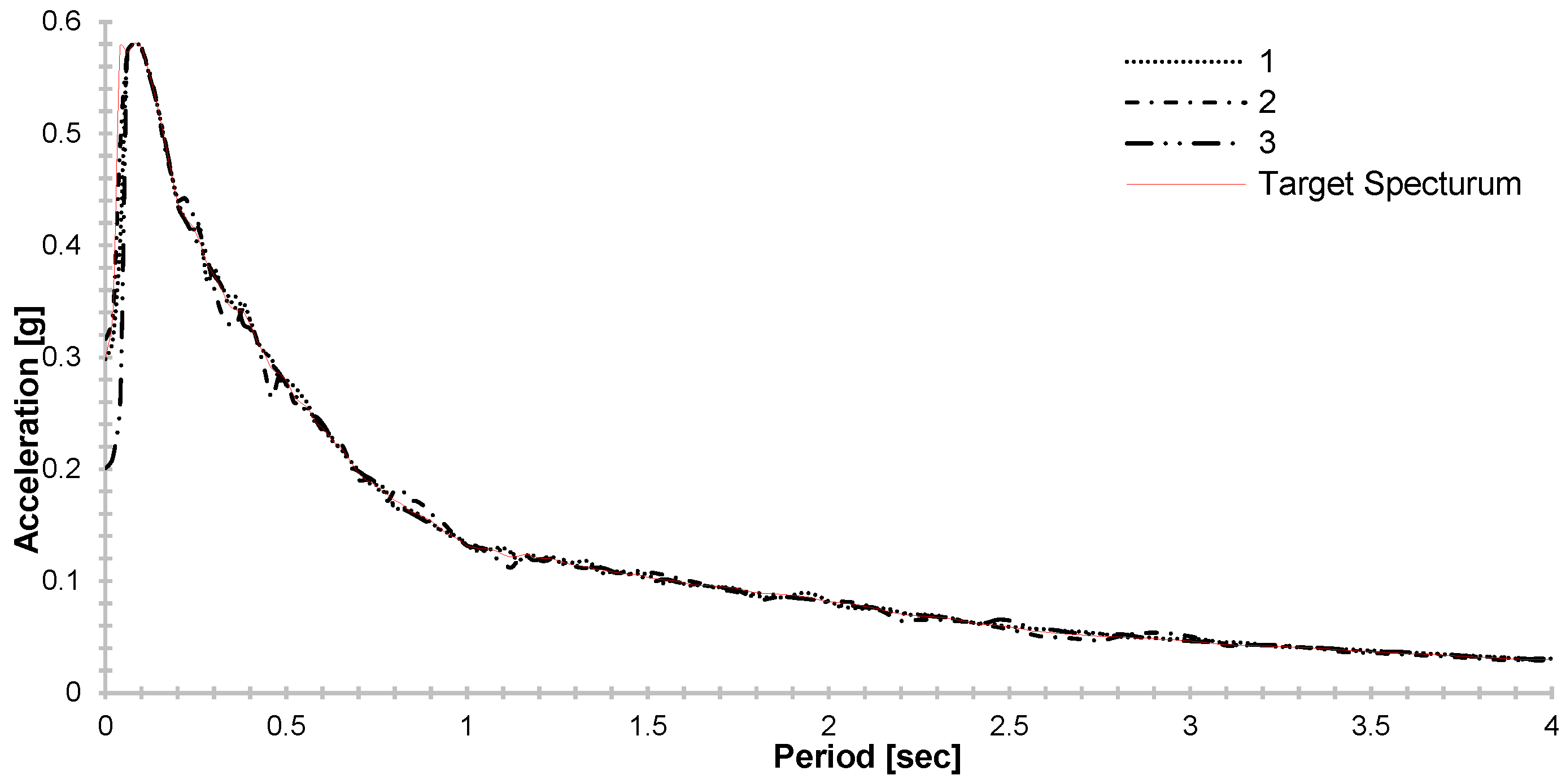

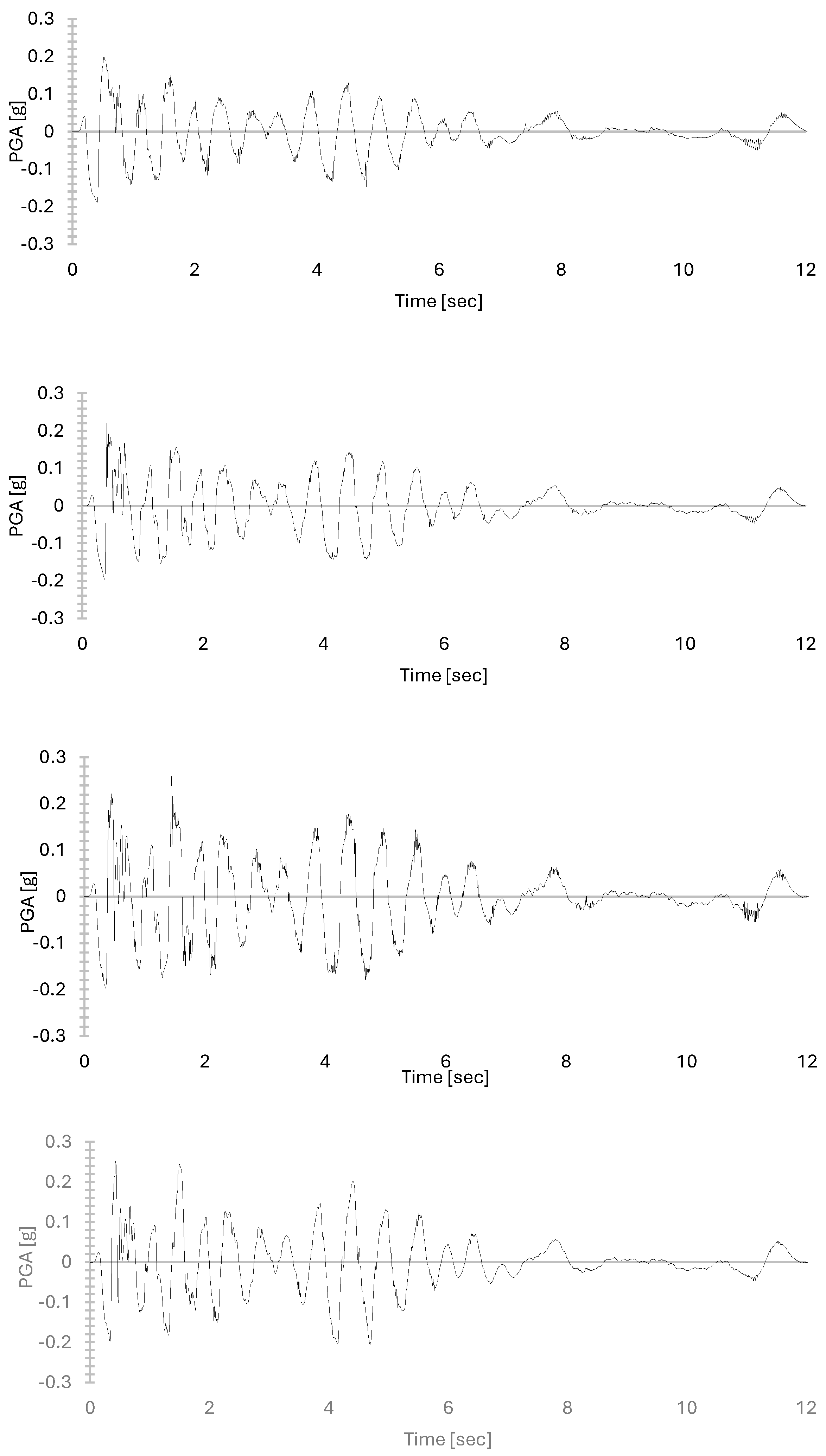

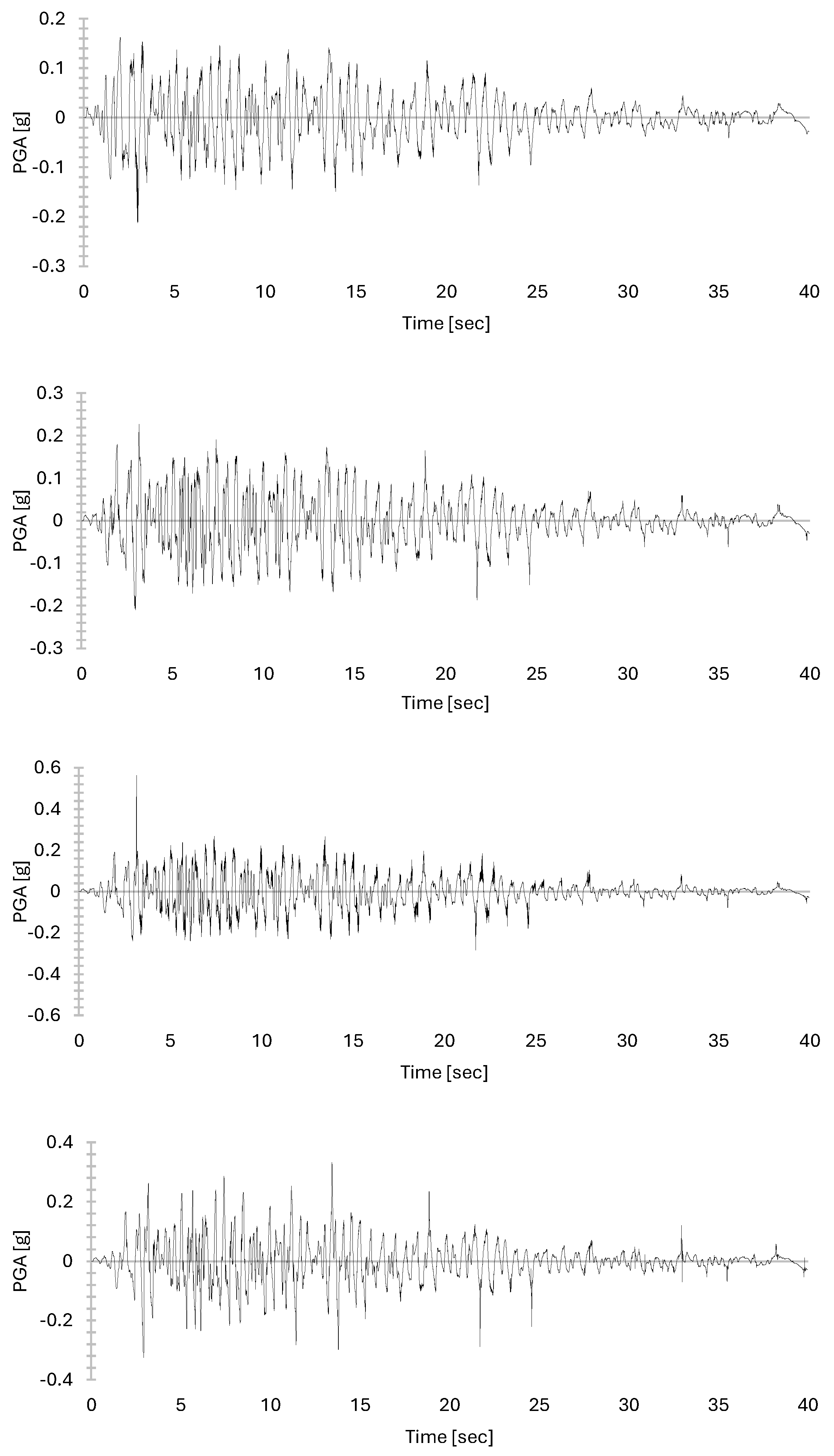

2.2.4. Ground Motion Selection and Spectral Matching

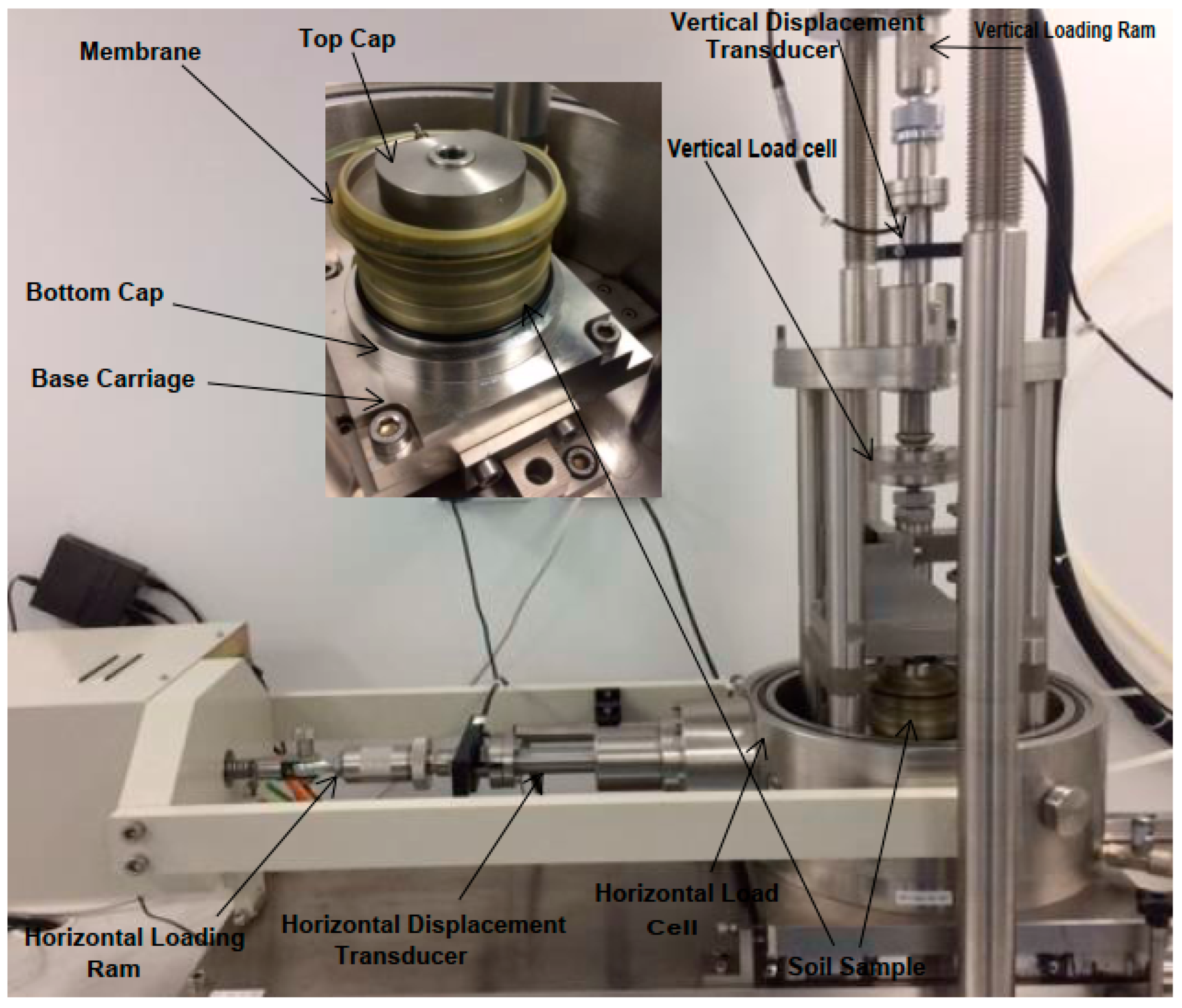

2.3. Laboratory Tests Setup

2.4. Numerical Model Verification

3. Results and Discussion

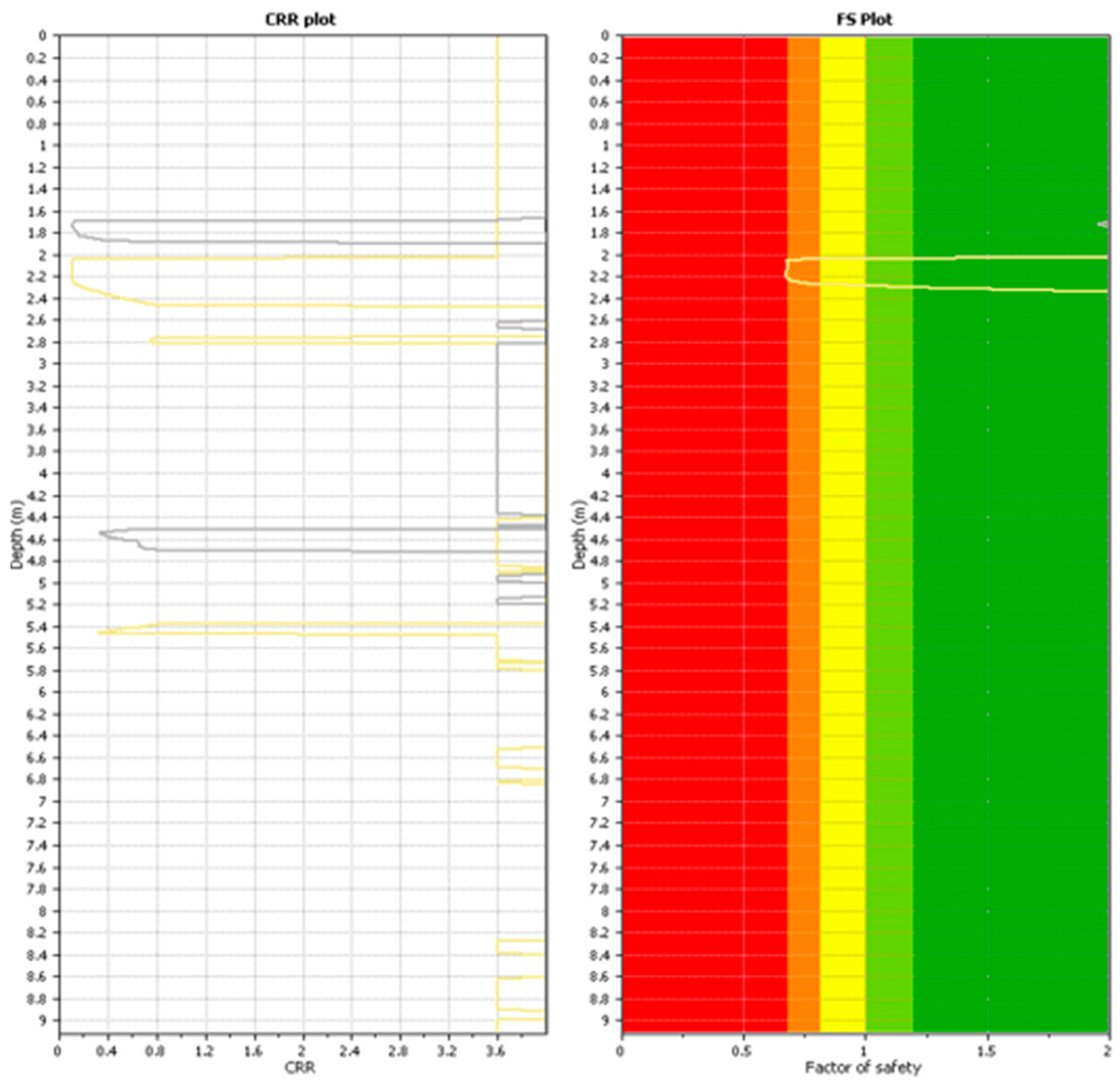

3.1. CPT-Based Cyclic Resistance and Liquefaction Assessment

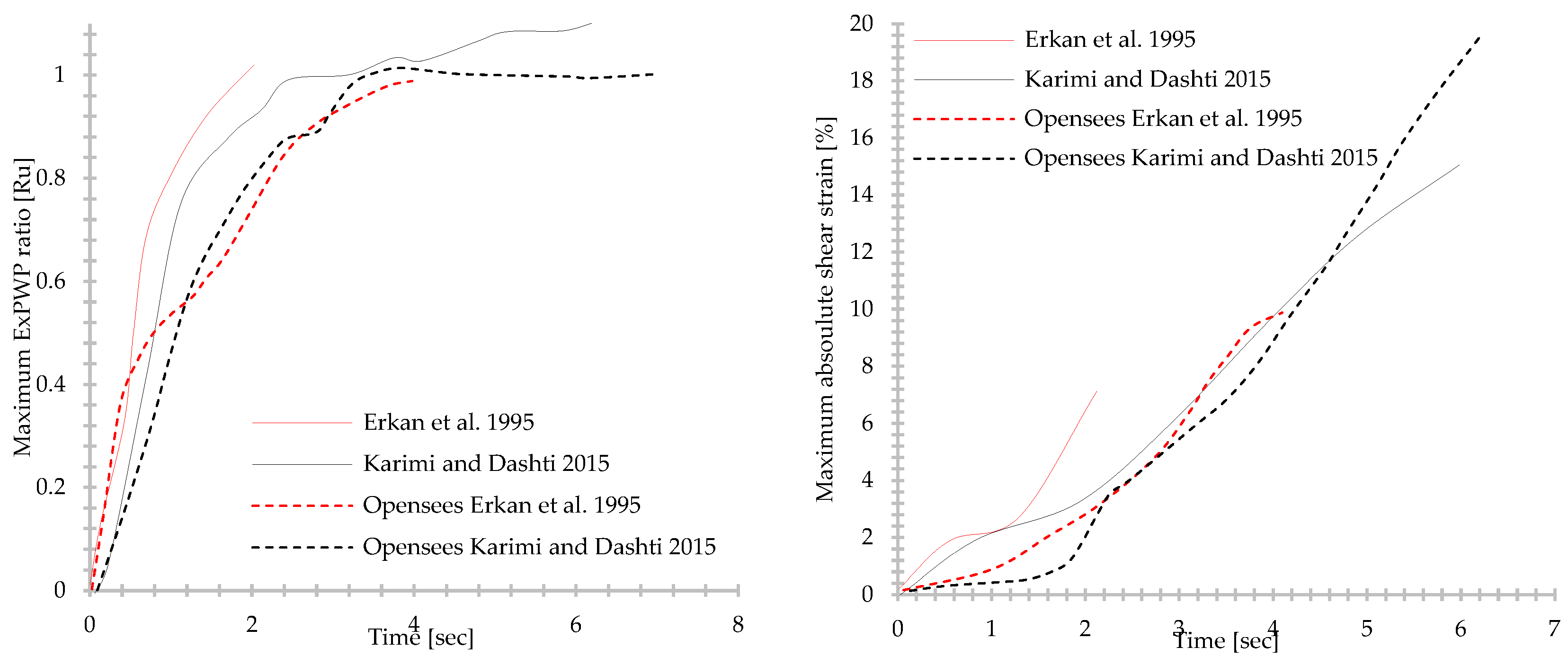

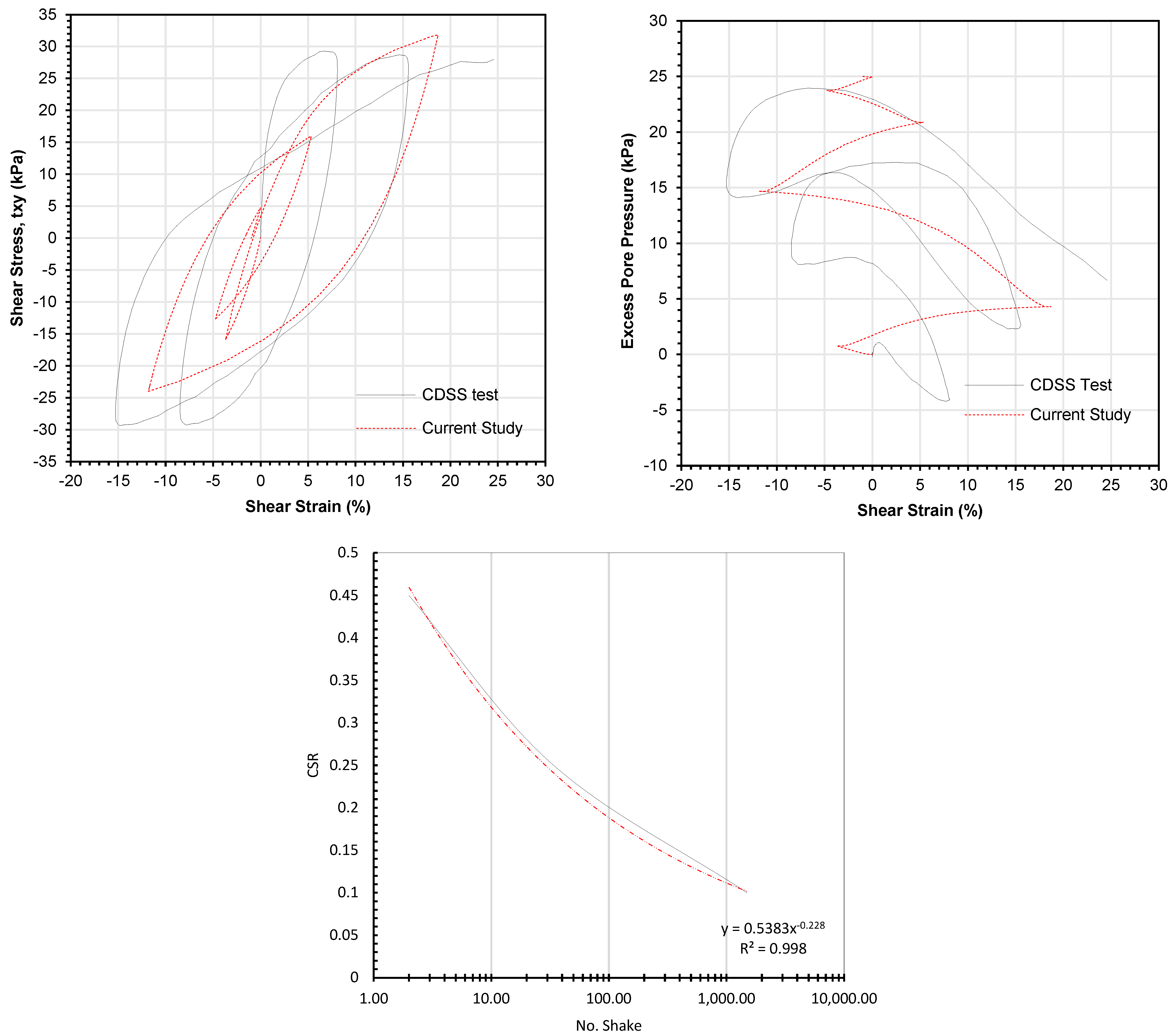

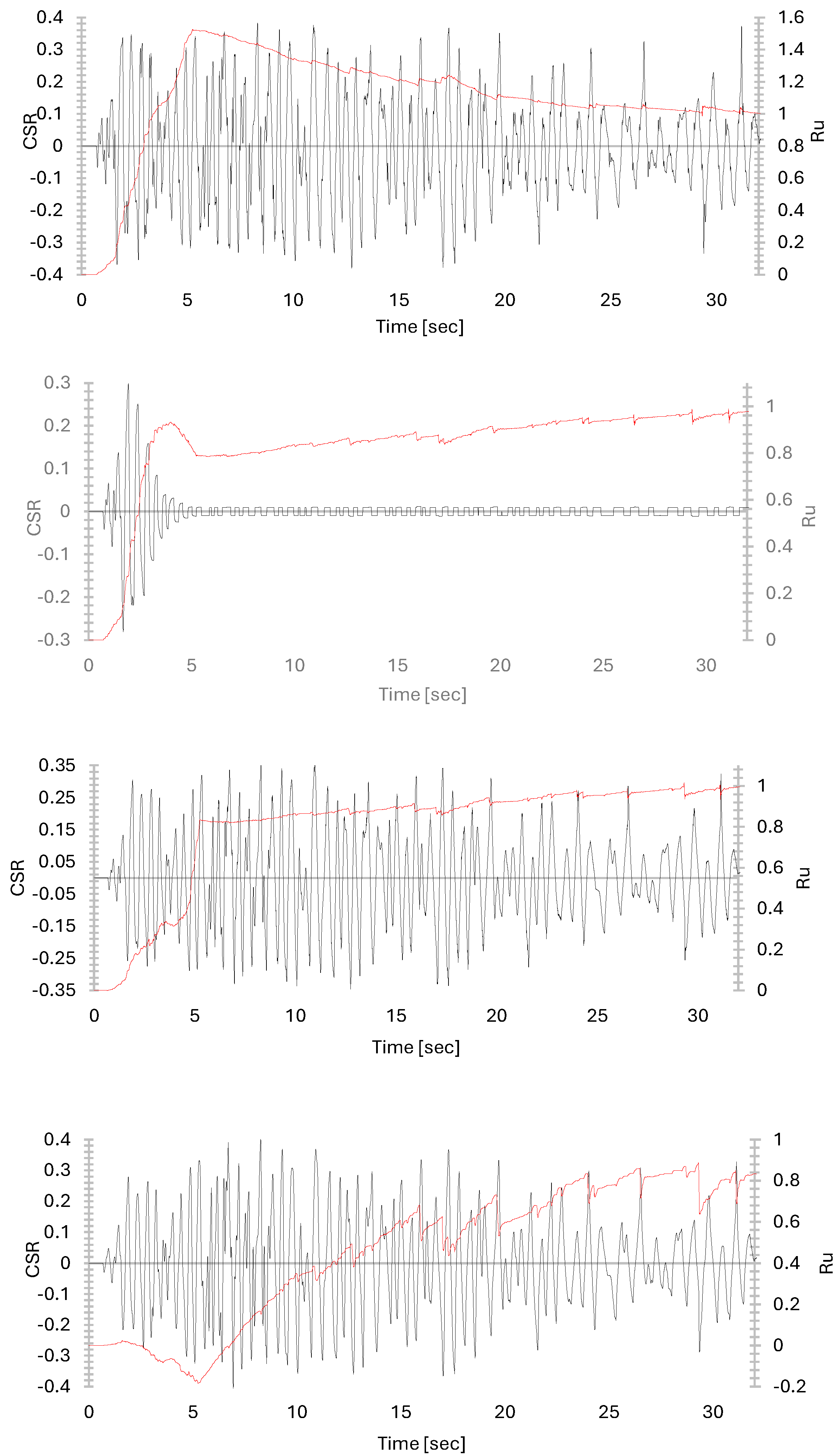

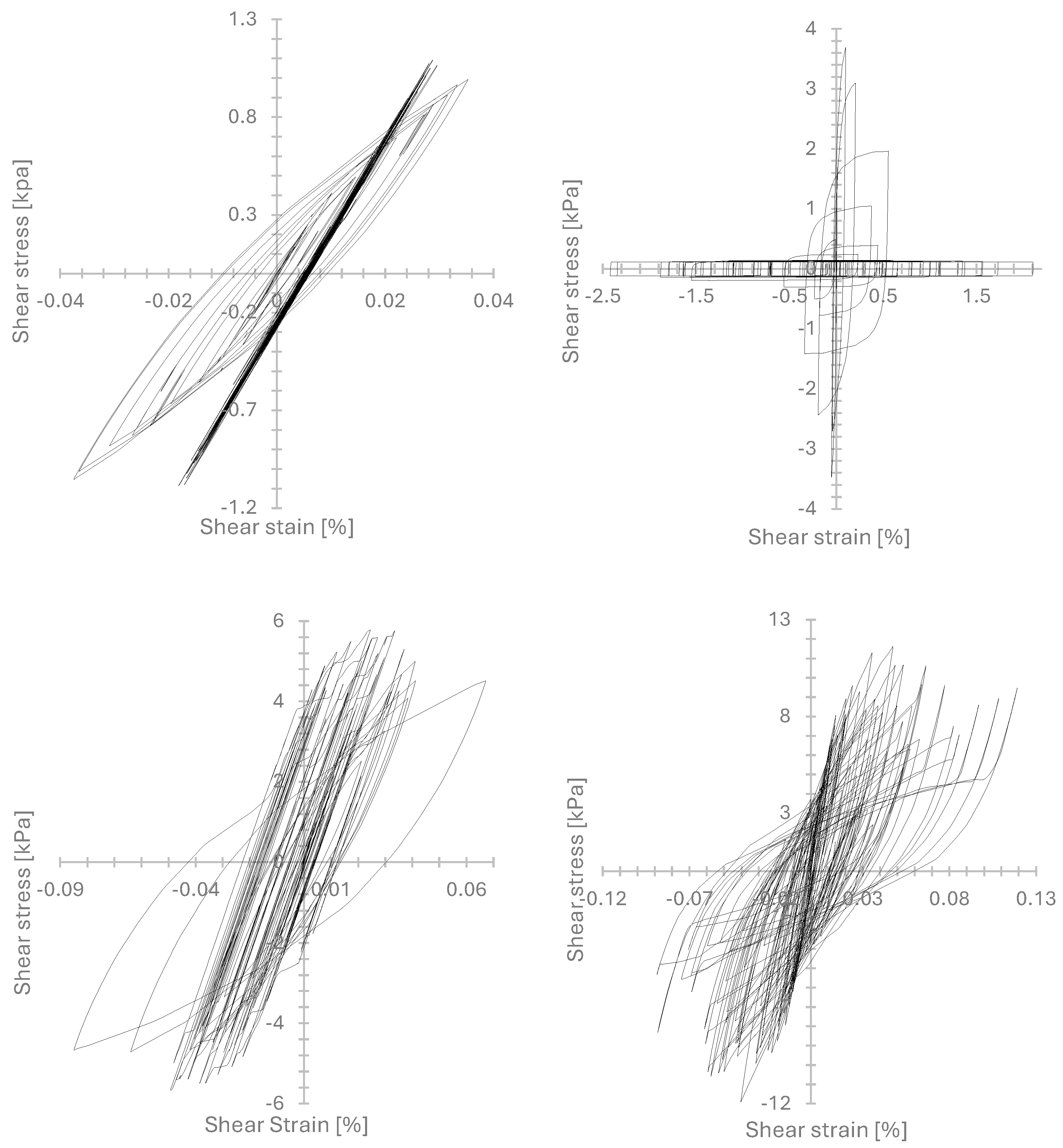

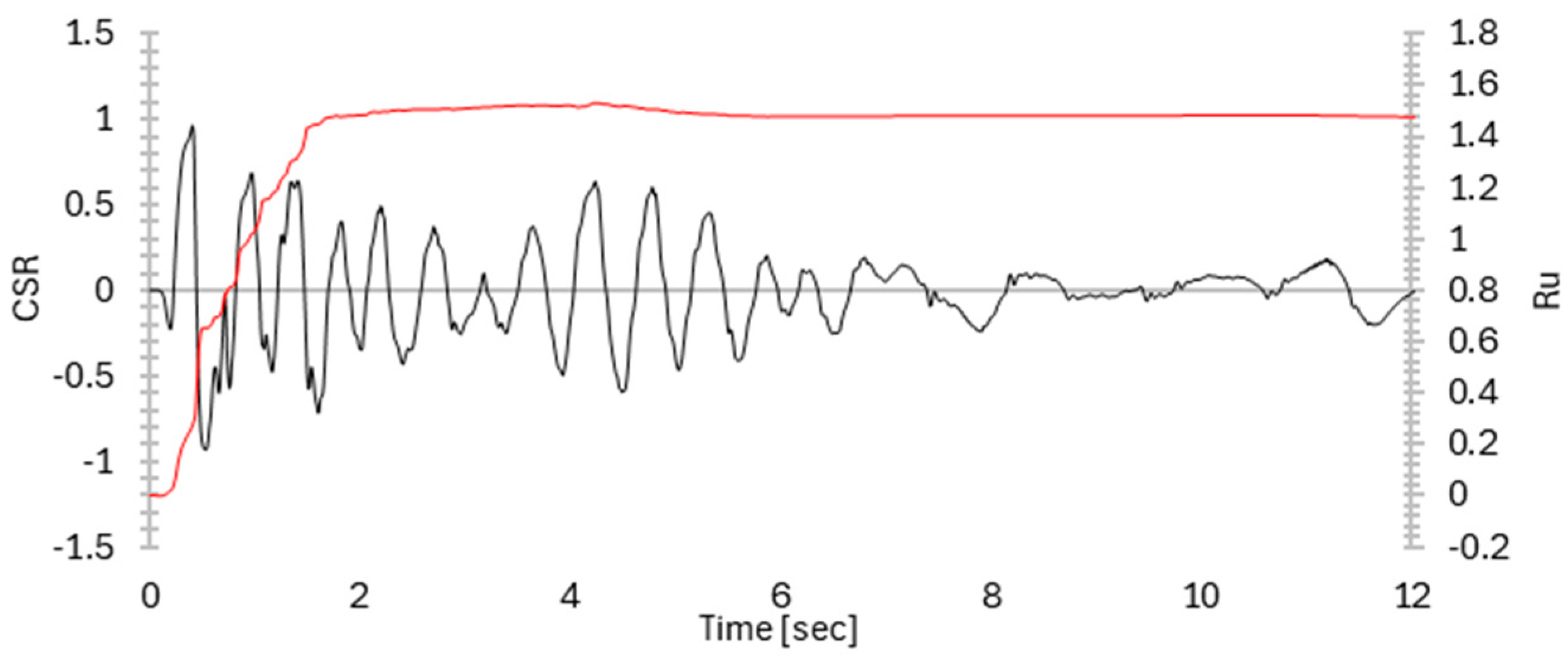

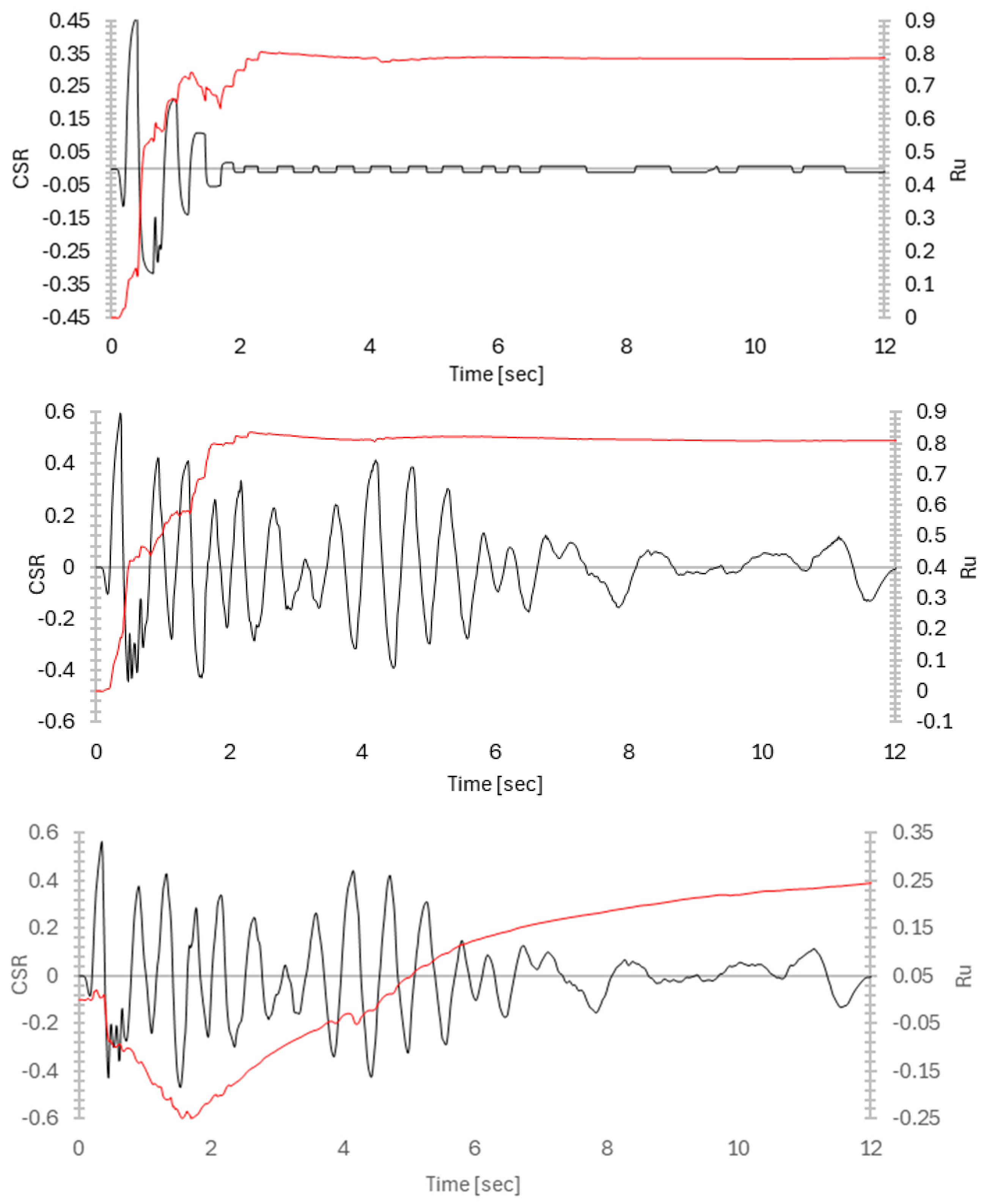

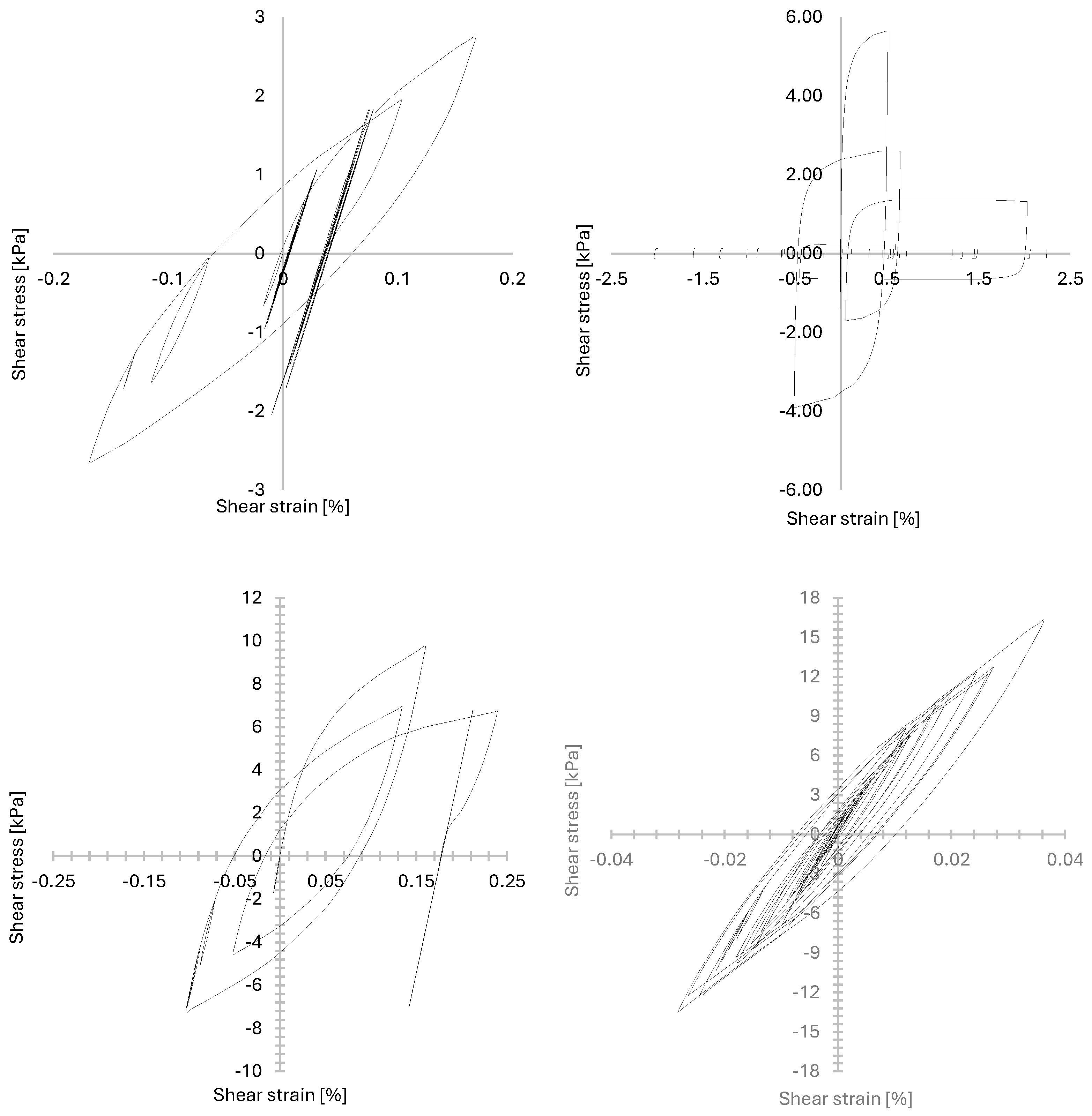

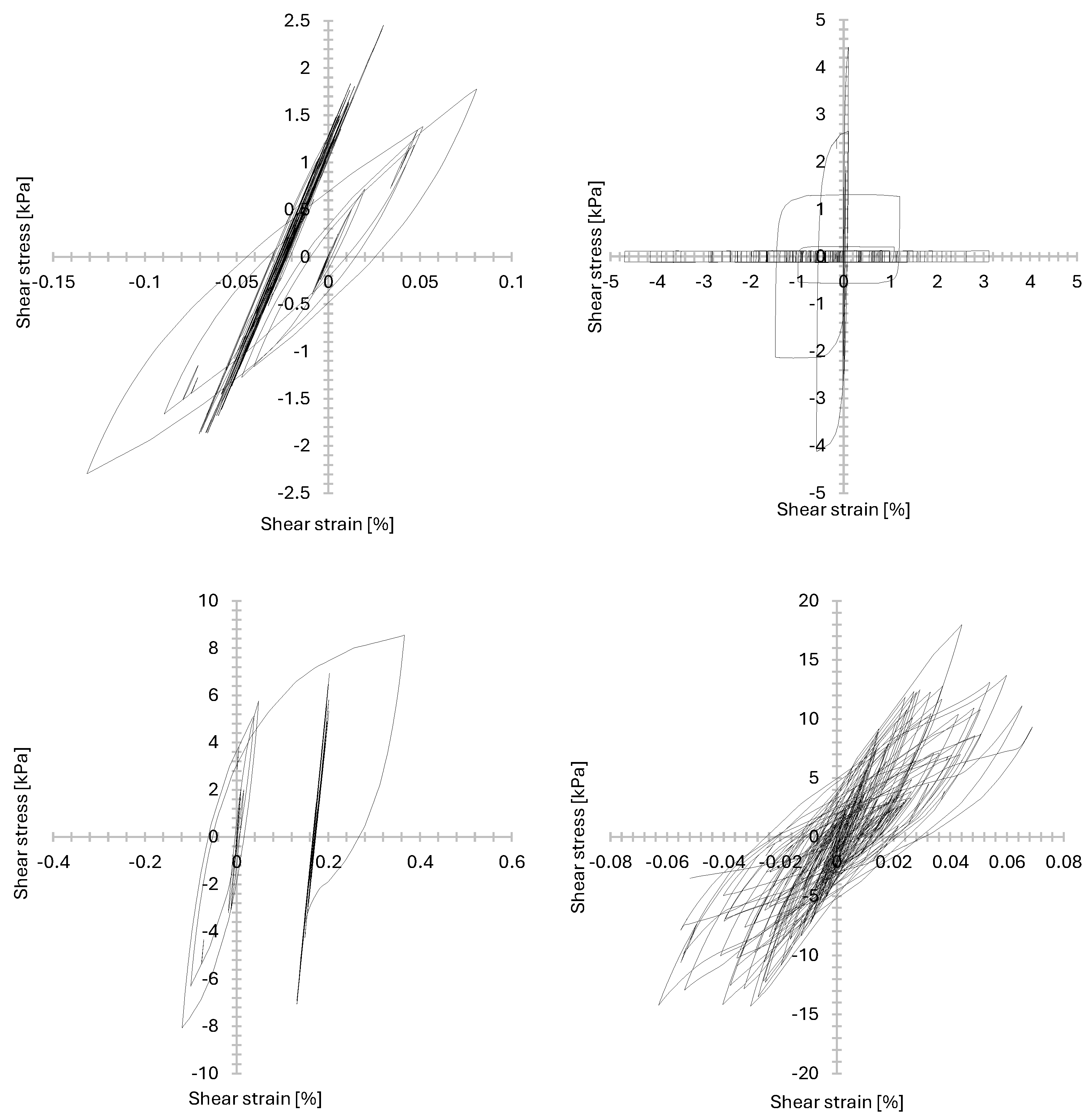

3.2. Numerical Model Verification with CDSS Laboratory Tests

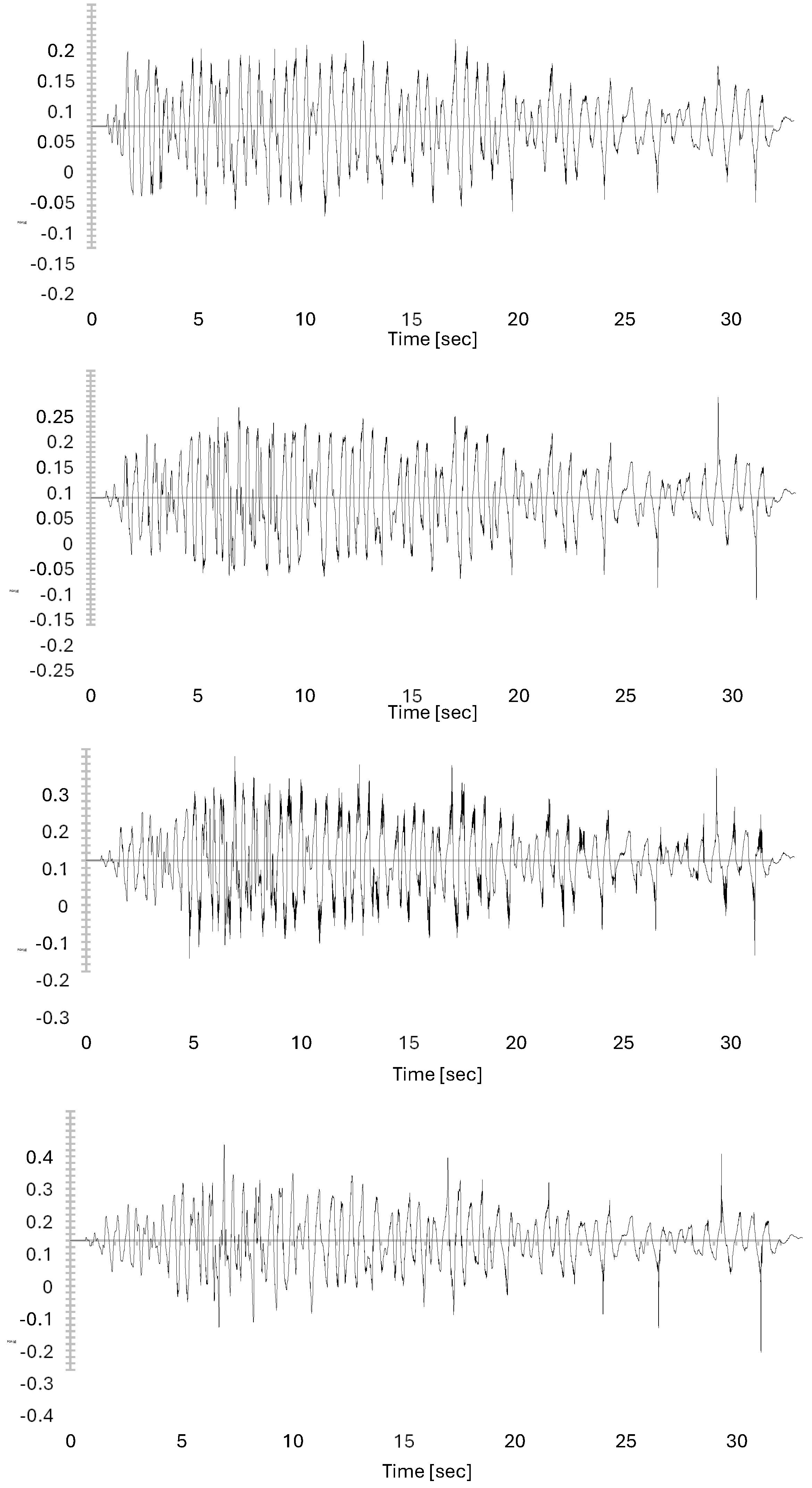

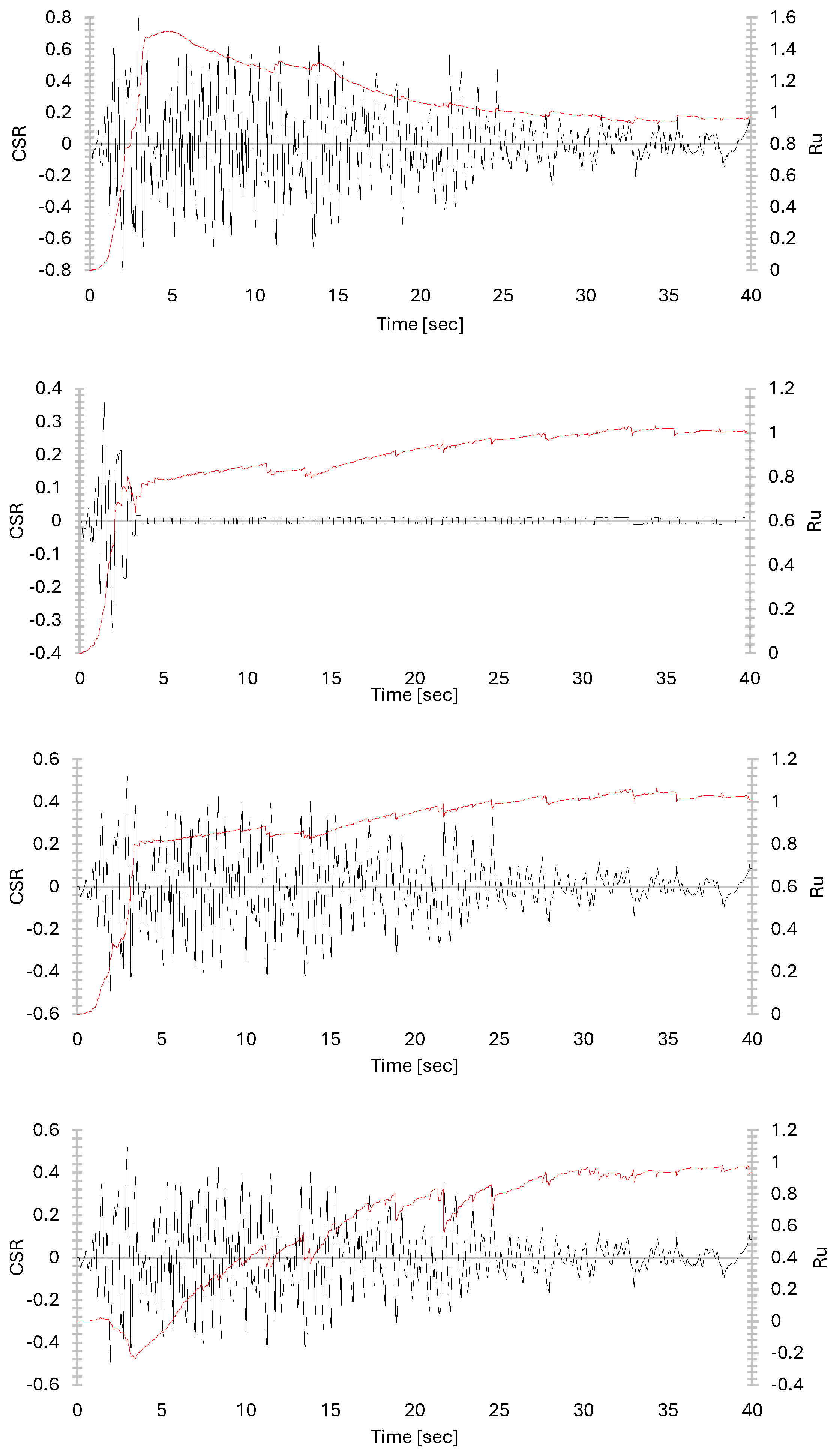

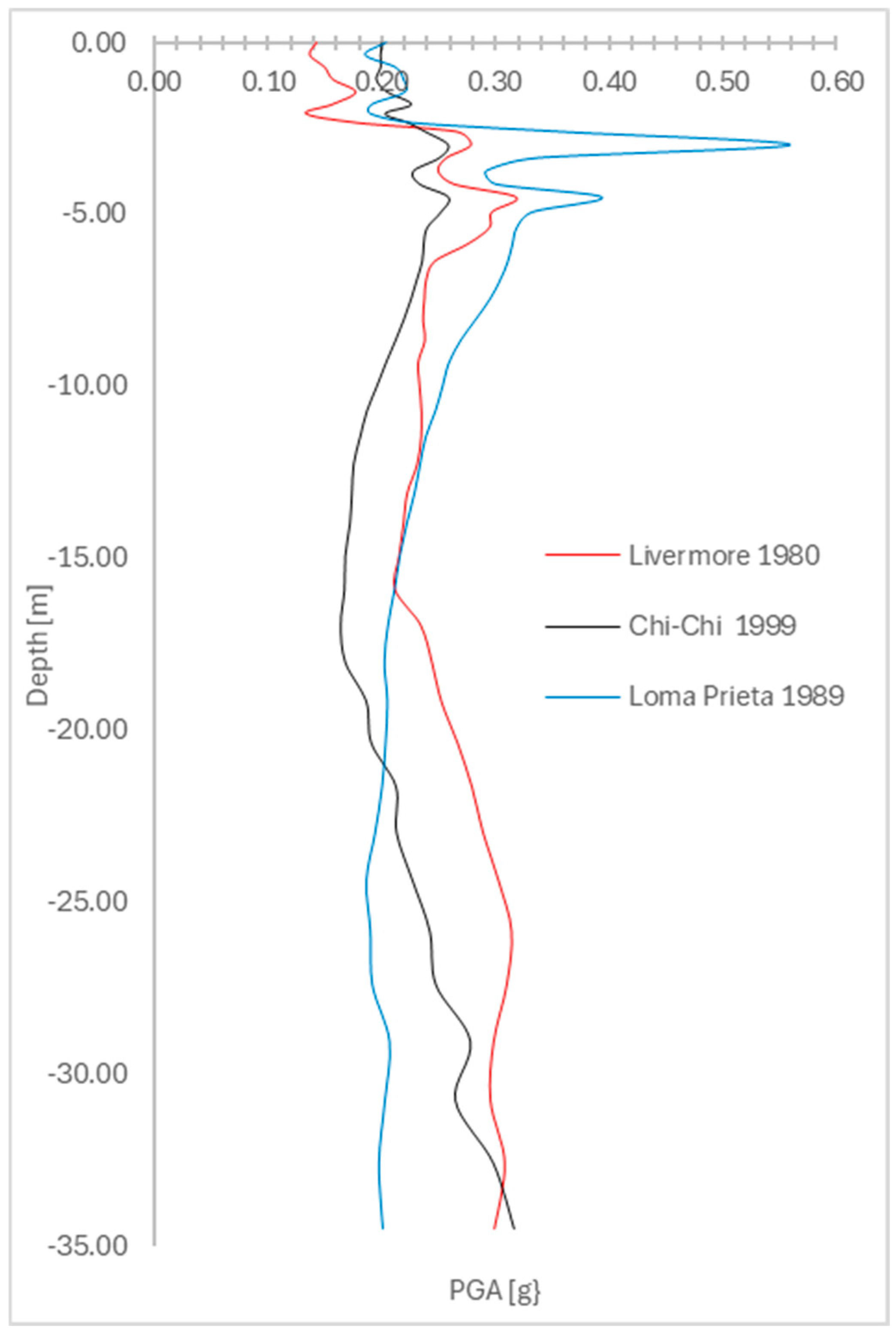

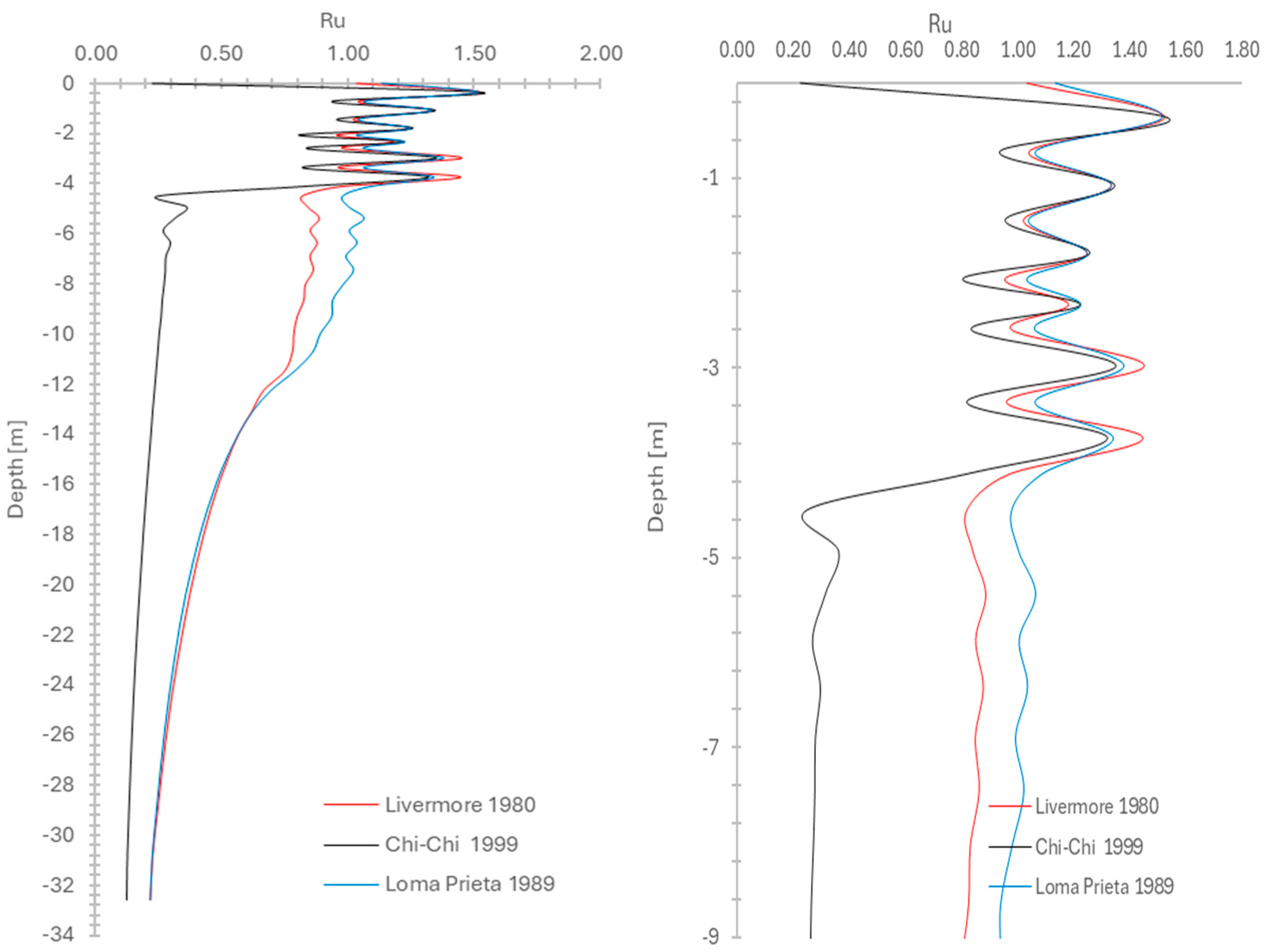

3.3. Time Histories Analysis

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

- The FEM approach provides a physics-based alternative to empirical CPT-based assessments, offering improved accuracy in evaluating cyclic stress degradation, excess pore pressure evolution, and strain softening effects.

- The verification against CDSS laboratory data confirms the reliability of the numerical model in predicting liquefaction and post-failure behavior, highlighting its ability to assess sediments often overlooked in traditional assessments.

- The numerical model demonstrated an average error of less than 10% compared to laboratory excess pore pressure and CSR response, validating its suitability for performance-based liquefaction assessment.

- The study identifies high susceptibility in near-surface sediments, particularly under low confining pressure, where significant amplification effects influence seismic ground stability.

- CPT-based CSR and CRR methods fail to account for drainage effects and soil permeability variations, making them less effective in predicting liquefaction potential compared to FEM simulations.

- The findings emphasize the limitations of empirical assessment methods for and highlight the importance of incorporating advanced numerical simulations for improved seismic hazard evaluations. Using both liquefaction approaches would provide more safe and reliable design in complex projects.

- Performance-based design approaches should include near-surface instrumentation for pore pressure and shear strain monitoring, particularly in the upper 2–3 m of newly placed fill where triggering is most likely.

- Empirical methods may underpredict liquefaction, especially in deeper layers where excess pore pressure redistribution and dynamic interaction effects are significant. Site-specific numerical modeling is recommended where possible.

- Permeability and consolidation characteristics must be explicitly assessed in both horizontal and vertical directions to predict drainage behavior under seismic loading.

- Dynamic analysis using calibrated constitutive models should be integrated into seismic risk assessments to complement or refine empirical predictions.

- This study is subject to limitations associated with the use of deterministic modeling, constant layer-wise permeability, and fully saturated conditions, which simplify field behavior. In addition, the identified Ru threshold and depth-dependent response are specific to the investigated reclaimed sediments and seismic inputs. Future work should extend the framework to include strain-dependent permeability, partial saturation effects, and broader parametric assessment under a wider range of ground motions and material conditions.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elgamal, A.; Yang, Z.; Parra, E. Computational modeling of cyclic mobility and post-liquefaction site response. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2002, 22, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, K.O.; Soylemez, B.; Guzel, H.; Cakir, E. Soil Liquefaction Sites Following the February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaraş–Türkiye Earthquake Sequence. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 23, 921–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziotopoulou, K.; Boulanger, R.W. Calibration and implementation of a sand plasticity plane-strain model for earthquake engineering applications. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2013, 53, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, H.B.; Idriss, I.M. Simplified procedures for evaluating soil liquefaction potential. J. Geotech. Eng. 1971, 97, 1249–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, K. Liquefaction and flow failure during earthquakes. Géotechnique 1993, 43, 351–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, S.L. Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, R.W.; Idriss, I.M. CPT and SPT Based Liquefaction Triggering Procedures; Center for Geotechnical Modeling, University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Shi, Y.; Sun, Z. Experimental study on strength and liquefaction characteristics of sand under dynamic loading. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, S.Y.; Tang, L.; Ling, X.Z.; Gen, L.; Lu, J.C. Numerical analysis of liquefaction-induced differential settlement of shallow foundations on an island slope. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 140, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgamal, A.; Parra, E.; Yang, Z.; Dobry, R.; Zeghal, M. Liquefaction constitutive model. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Physics and Mechanics of Soil Liquefaction, Baltimore, MD, USA, 10–11 September 1998; Lade, P.V., Ed.; A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, R.W.; Ziotopoulou, K. PM4Sand (Version 3.1): A Sand Plasticity Model for Earthquake Engineering Applications; University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abbar, B.; Isch, A.; Michel, K.; Abbas, M.; Vincent, H.; Abbasimaedeh, P.; Azaroual, M. Fiber optic technology for environmental monitoring: State of the art and application in the observatory of transfers in the vadose zone (O-ZNS). In Instrumentation and Measurement Technologies for Water Cycle Management; Springer Water; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 189–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.S.; Hossain, A.S.; Hasan, M.F.; Rahman, M.A.; Biswas, P.; Zaman, M.N. Unravelling the risk of dredging on river bars for mineral sand mining: An engineering geological approach. Discov. Geosci. 2025, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetan, O.; Nie, J.; Viteritto, M.; Feng, H. Evaluation of sediment dredging in remediating toxic metal contamination—A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 69837–69856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Stringer, M.; Cubrinovski, M. Liquefaction vulnerability of reclamations at CentrePort, Wellington. In Proceedings of the 17th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Sendai, Japan, 13–18 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Martin, J.R.; Ku, C.-S.; Lu, Y.-C. A case study of the effect of dynamic compaction on liquefaction of reclaimed ground. Eng. Geol. 2018, 240, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, T.D.; Robertson, P.K.; Sego, D.C. Influence of fines on the collapse of loose sands. Can. Geotech. J. 1994, 31, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, N.; Tolooiyan, A. Effect of Sand Content on the Liquefaction Potential and Post-Earthquake Behaviour of Coode Island Silt. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2021, 39, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.D.; Sancio, R.B. Assessment of the liquefaction susceptibility of fine-grained soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2006, 132, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, K.O.; Seed, R.B.; Der Kiureghian, A.; Tokimatsu, K.; Harder, L.F.; Kayen, R.E.; Moss, R.E.S. Standard penetration test-based probabilistic and deterministic assessment of seismic soil liquefaction potential. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2004, 130, 1314–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielak, J.; Ghattas, O.; Kim, E.J. Parallel octree-based finite element method for large-scale earthquake ground motion simulation. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2005, 10, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ghahari, F.; Arduino, P.; Taciroglu, E. A deep learning approach for rapid detection of soil liquefaction using time–frequency images. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 166, 107788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimai, K.; Liu, W.; Maruyama, Y. Prediction and factor analysis of liquefaction ground subsidence based on machine-learning techniques. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasimaedeh, P. Soil liquefaction in seismic events: Pioneering predictive models using machine learning and advanced regression techniques. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, S.; Bray, J.D.; Pestana, J.M.; Riemer, M.; Wilson, D. Centrifuge Testing to Evaluate and Mitigate Liquefaction-Induced Building Settlement Mechanisms. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2010, 136, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahir, H.; Pak, A.; Taiebat, M.; Jeremić, B. Evaluation of variation of permeability in liquefiable soil under earthquake loading. Comput. Geotech. 2012, 40, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najma, A.; Latifi, M. Collapse surface approach as a criterion of flow liquefaction occurrence in 3D FEM models. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 107, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najma, A.; Latifi, M. Predicting flow liquefaction: A constitutive model approach. Acta Geotech. 2017, 12, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Vo, T.L.; Russell, A. Modelling unsaturated silty tailings and the conditions required for static liquefaction. Géotechnique 2023, 74, 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafalias, Y.F.; Manzari, M.T. Simple plasticity sand model accounting for fabric change effects. J. Eng. Mech. 2004, 130, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adampira, M.; Derakhshandi, M. Influence of a layered liquefiable soil on seismic site response using physical modelling and numerical simulation. Eng. Geol. 2020, 266, 105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biot, M.A. Mechanics of deformation and acoustic propagation in porous media. J. Appl. Phys. 1962, 33, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AS 1289.3.6.1-2009; Methods of Testing Soils for Engineering Purposes—Soil Classification Tests—Determination of the Particle Size Distribution of a Soil—Standard Method of Analysis by Sieving. Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2009.

- Robertson, P.K. Evaluation of flow liquefaction and liquefied strength using the cone penetration test. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2010, 136, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamiolkowski, M.; Lo Presti, D.C.F.; Pallara, O. Role of in-situ testing in geotechnical earthquake engineering. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics, St. Louis, MO, USA, 2–7 April 1995; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kulhawy, F.H.; Mayne, P.W. Manual on Estimating Soil Properties for Foundation Design; Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI): Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, P.K.; Cabal, K. Guide to Cone Penetration Testing, 7th ed.; Gregg Drilling LLC: Signal Hill, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vucetic, M.; Dobry, R. Effect of Soil Plasticity on Cyclic Response. J. Geotech. Eng. 1991, 117, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, L.; Yin, K.; Song, C.; Bian, X.; Li, S. Methods for Solving Finite Element Mesh-Dependency Problems in Geotechnical Engineering—A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Elgamal, A.; Parra, E. Computational model for cyclic mobility and associated shear deformation. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2003, 129, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Arduino, P.; Kramer, S.L. Performance-based evaluation of bridges on liquefiable soils. In Proceedings of the Structures Congress 2007: Structural Engineering Research Frontiers, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–19 May 2007; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawy, M.A.; Zhou, Y.-G.; Liu, K. A Modified Pressure-Dependent Multi-Yield Surface Model for Simulation of LEAP-Asia-2019 Centrifuge Experiments. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 152, 107135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A.K. Dynamics of Structures: Theory and Applications to Earthquake Engineering, 4th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Newmark, N.M. A method of computation for structural dynamics. J. Eng. Mech. 1959, 85, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER). PEER Ground Motion Database (NGA-West2); University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://ngawest2.berkeley.edu (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Boore, D.M.; Atkinson, G.M. Spectral Scaling of the 1985 to 1988 Nahanni, Northwest Territories, Earthquakes. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1989, 79, 1736–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.Y.; Shan, B.H.; Lu, D.G. Selection of Optimal Seismic Intensity Measures for Evaluating Liquefaction Triggering: Accounting for the Influence of Liquefiable Sites. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 22121–22149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erken, A.; Ansal, A.M. Liquefaction of Silt and Sand Layers in Ekşisu–Erzincan Earthquake. In Geotechnical Engineering; Ishihara, K., Ed.; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; ISBN 905410578X. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, Z.; Dashti, S. Numerical and centrifuge modelling of seismic soil–foundation–structure interaction on liquefiable ground. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, P.K. Interpretation of cone penetration tests: A unified approach. Can. Geotech. J. 2009, 46, 1337–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idriss, I.M.; Boulanger, R.W. Soil Liquefaction during Earthquakes; Monograph MNO-12; Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI): Oakland, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, P.K. Evaluating Cyclic Liquefaction Potential Using the Cone Penetration Test. Can. Geotech. J. 1998, 35, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenSees Berkeley, The Open System for Earthquake Engineering Simulation; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://opensees.berkeley.edu (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Zhai, W.; Wang, F.; Faramarzi, A.; Metje, N. Model-free data-driven computational analysis for soil consolidation problems. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer | Material Type | [kN/m3] | [kPa] | [o] | [kPa] | Permeability [m/s] | Depth [m] | [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reclaimed Sediment Mud | 16 | 5 | 26 | 0.22 | 10 | 1.00 × 10−9 | 0–1.8 | 30% |

| 2 | Interface Material | 18 | 1 | 32 | 0.3 | 50 | 1.00 × 10−6 | 1.8–2.6 | 50% |

| 3 | Consolidated Reclaimed Sediment Mud | 17 | 7 | 28 | 0.25 | 50 | 1.00 × 10−8 | 2.6–4.5 | 40% |

| 4 | Foundation (Bottom Layer) | 19 | 5 | 30 | 0.33 | 50 | 1.00 × 10−7 | 4.5–30 | 60% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abbasimaedeh, P. Numerical Simulation of Liquefaction Behaviour in Coastal Reclaimed Sediments. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010008

Abbasimaedeh P. Numerical Simulation of Liquefaction Behaviour in Coastal Reclaimed Sediments. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbasimaedeh, Pouyan. 2026. "Numerical Simulation of Liquefaction Behaviour in Coastal Reclaimed Sediments" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010008

APA StyleAbbasimaedeh, P. (2026). Numerical Simulation of Liquefaction Behaviour in Coastal Reclaimed Sediments. GeoHazards, 7(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010008