1. Introduction

Dwindling oil reserves and advancing climate change make it urgently necessary to develop alternative resources and production methods. An important strategy for this is the transition to a circular economy, in which waste and residual materials become new resources. The bioeconomy plays a key role in this by using renewable raw materials and microorganisms to manufacture new products such as biofuels, chemicals, or materials [

1]. In order to avoid competition with food and feed, priority should be given to the utilization of agricultural and industrial residues and waste products rather than the requisition of new land for the cultivation of renewable raw materials [

2,

3].

Fumaric acid, an unsaturated dicarboxylic acid, has been identified as one of the most important bio-based chemicals [

4,

5]. The substance is employed as a co-monomer for polymerization and esterification reactions for the production of unsaturated polyester and alkyd resins and is also applied in the pulp industry as an acidic tackifier for rosin paper. Furthermore, fumaric acid has been employed as an acidulant and additive within the food and feed industry [

6,

7]. In recent years, fumaric acid esters have been found effective in biomedical applications such as the treatment of multiple sclerosis and psoriasis [

8,

9]. Nowadays, fumaric acid is still produced through the isomerization of maleic acid, a commodity chemical produced exclusively from petrochemicals such as butane, butene, or benzene [

7,

10,

11]. In the context of rising concerns regarding the sustainability of the prevailing fossil-based pathway for fumaric acid production, there is an imperative for the development of alternative, more sustainable production processes.

The microbial production of fumaric acid presents an alternative method of synthesizing fumaric acid. This approach has recently garnered renewed interest due to its alignment with the contemporary concepts of the bioeconomy and circular economy. A substantial number of reviews have been published on the subject of biotechnical fumaric acid production [

6,

7,

10,

11,

12,

13]. According to the literature, there are several wild-type fungal strains that have been identified as being capable of naturally overproducing fumaric acid. The most efficient of these are

Rhizopus species, such as

oryzae and

arrhizus. Furthermore, genetically modified organisms, predominantly bacteria or yeast-like strains, have been developed and described as useful fumaric acid producers [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Fumaric acid is a metabolite in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Depending on the metabolic pathway, i.e., oxidative or reductive TCA cycle, the latter requiring CO

2 fixation, a theoretical yield of 1 mol fumaric acid/mol of glucose (0.64 g

FA/g

glucose) in the oxidative TCA cycle or 2 mol of fumaric acid/mol of glucose (1.29 g

FA/g

glucose), respectively, in the reductive TCA cycle can be achieved. In the context of the fungal production of fumaric acid, the morphology of the biomass in submerged fermentation systems, which can manifest as clumps, pellets, or filaments, is a pivotal parameter. Clumps and larger pellets lead to a poor oxygen supply and the unintentional production of ethanol, whereas small pellets and especially a filamentous morphology, i.e., loose mycelium, are preferred for high fumaric acid accumulation [

6,

11,

18,

19]. Immobilized biomass in either batch [

20,

21] or continuous cultivation systems [

22,

23] reduces the influence of fungal morphology during the fumaric acid production phase to a certain extent. A plethora of factors, e.g., the cultivation system itself, inoculum size, working volume, agitation, aeration, pH, type of neutralizing agent, and temperature, have been identified as influential on fungal growth and production performance in submerged cultivations [

6,

7,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Another significant parameter is the nutrient supply for the fungus. In addition to metal ions as micronutrients and phosphorus, a nitrogen source is required in the case of coupled growth and fumaric acid production. The utilization of complex nutrients, which frequently encompasses yeast extract, in conjunction with less prevalent nitrogen sources such as corn steep liquor, soybean meal hydrolysates, and even casein [

24], along with inorganic compounds, predominantly ammonium salts [

6,

7,

10,

11,

12,

13], has been documented. It is important to note that under nitrogen-limiting conditions, biomass growth is restricted, resulting in non-growth coupled fumaric acid production, which may yield higher levels of production. Glucose is usually used as a carbon and energy source, although different nutrients, namely, other monosaccharides such as xylose [

25,

26] or fructose [

27], also allow fumaric acid accumulation during fermentation. Different types of lignocellulosic hydrolysates [

28,

29,

30,

31], liquid food waste [

32,

33], or apple pomace [

21,

34,

35] are also described as alternative carbon sources. The use of alternative carbon sources, however, still leads to unsatisfactory results in terms of fumaric acid yields and titers.

Apple pomace is a press residue that is produced in large quantities during the industrial production of apple juice. According to a recent FAO report [

36], worldwide, 97 million tons of apples were produced in 2023. Between 2010 and 2023, apples showed the fastest growth of 37% over the period among all types of fruits. The main producing countries are China, the USA, Poland, and Turkey [

12,

37,

38]. Depending on the press used, approximately 25–30% of the original apple remains as pomace. It is estimated that approximately 4 million tons of apple pomace are generated on an annual basis worldwide [

12,

39,

40]. It consists of solid components such as peel, pulp, core, seeds, and stems and contains various valuable ingredients, including pectin, carbohydrates, organic acids, fatty acids, triterpenes, and polyphenols [

12,

38,

41,

42].

Notwithstanding the valuable components present in apple pomace, the majority of it is not utilized and is instead discarded. However, it should be noted that some components of the apple pomace are already in current use. The applications of apple pomace are diverse and include the following: pectin as a thickening agent or baking ingredient, the production of neutraceuticals, the extraction of bioactive components with anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, and/or anti-oxidant properties, animal feed, fertilizer, enzyme production, or the production of biogas, pyrolysis oil, biochar, or activated carbon [

12,

37,

38,

40,

42,

43].

Another, still less common application is its use as a carbon source in biorefinery applications. In this regard, apple pomace is used for the production of enzymes, organic acids, e.g., citric acid, lactic acid, or acetic acid, butanol, ethanol, biogas, hydrogen, biopolymers, aroma compounds, or single-cell protein [

12,

44,

45]. Research on its use as a carbon source for microbial fermentation is still ongoing, as documented in more recent publications about the production of bioactive compounds [

46], butanol [

47], lactic acid [

48], single-cell protein [

49], or citric acid [

50].

Considering its utilization as a substrate for biotechnological biorefinery processes, apple pomace presents two potential carbon sources. On the one hand, there are structurally bound polysaccharides of cellulose and hemicellulose, which still need to be monomerized for microbial use. On the other hand, there are water-soluble sugars, which are not separated from the pomace during pressing, being present therein as mono- or disaccharides, and can therefore be metabolized directly. These water-soluble sugars, namely, glucose, fructose, and sucrose, have been identified in the liquid part of the apple pomace, which contains a moisture content of 70–85% [

45,

51]. The absolute concentration of non-structurally bound, water-soluble sugars depends largely on the processing strategy used during pressing. In the production of direct juice, the apple juice is usually separated by means of simple hydraulic pressing, without further treatment of the press residues. The liquid remaining in the apple pomace is therefore unpressed apple juice with a high sugar concentration. In the production of apple juice concentrate, on the other hand, after the first pressing, further water-soluble sugars are extracted by adding water and pressing again and separated from the apple pomace. Apple pomace produced during the production of apple juice concentrate thus has a lower water-soluble sugar content [

52].

In the present study, we describe a novel approach for the use of apple pomace, a currently still not well utilized agricultural residue, as substrate for a biotechnological biorefinery process to fumaric acid. We compare different pressing and extraction processes to obtain sugary liquids consisting of the water-soluble carbohydrate fraction of the apple pomace. After purification, the obtained apple pomace juice was used as substrate for the production of fumaric acid with Rhizopus arrhizus NRRL 1526 in two different cultivation strategies, i.e., the growth-coupled and growth-decoupled production of fumaric acid. This novel substrate utilization strategy, in combination with an adjusted cultivation strategy, leads to a higher process efficiency in terms of fumaric acid yields and titers, the latter being the highest reported to date using alternative, residue-based fermentation substrates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Apple Pomace

The apple pomace used was obtained from the fruit juice manufacturer riha WeserGold (Rinteln, Germany) from a pressing in May 2016. riha WeserGold generally uses various conventionally grown apple varieties for apple juice production (direct juice). Due to its short shelf life, the apple pomace provided was stored at −20 °C immediately after pressing and gently thawed at 4 °C for the experiments.

2.2. Composition of Apple Pomace

2.2.1. Dry Matter and Residual Moisture

The proportion of dry matter (DM) and residual moisture in apple pomace was determined gravimetrically. For this purpose, 20 g of thawed apple pomace was dried in a balanced porcelain crucible at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved, cooled in a desiccator, and weighed. The proportion of dry matter and residual moisture was calculated by determining the difference in weight.

2.2.2. Ash Content

To determine the ash content, 5 g of dried apple pomace was ashed in a muffle furnace (MR 260 E, Heraeus, Hanau, Germany) at 550 °C for 24 h and weighed in a desiccator after the samples had cooled down.

2.2.3. Nitrogen Content According to Kjeldahl

Apple pomace was weighed into a digestion flask. Boiling chips, a Kjeltab (5 g K2SO4 and 5 mg selenium), and 10 mL of a 96% H2SO4 solution were then added. After standing for approx. 24 h at room temperature, thermal digestion was carried out in a Kjeldatherm system (Model TZs, Gerhardt, Königswinter, Germany) according to the following temperature program: (i) 30 min at 100 °C, (ii) 60 min at 200 °C, (iii) 60 min at 300 °C, (iv) 60 min at 420 °C, and (v) 30 min at room temperature.

After thermal digestion, the ammonium sulfate was converted to ammonia with sodium hydroxide. Ammonia was introduced into a 2% boric acid solution by means of steam distillation, where it reacted to form ammonium borate. The amount of ammonia was determined by means of back titration with 0.05 M H2SO4 to the original pH value of the boric acid, and the nitrogen content (x6.25) was calculated from this. Distillation and titration were carried out in a Vapodest system (Model 200, Gerhardt, Königswinter, Germany).

2.2.4. Proportional Sugar Composition

Since apple pomace contains both water-soluble sugars and structurally bound polysaccharides, two consecutive analytical methods were used to quantify both sugar fractions. First, apple pomace was dried at a temperature of 60 °C in a drying oven (Model 400, Memmert GmbH, Schwabach, Germany) until mass consistency was achieved. The dried apple pomace was then mechanically milled at 18,000 rpm using an ultracentrifugal mill from Retsch (Model ZM 200, Haan, Germany). Using an integrated sieve (pore size 1.0 mm), the dried and mechanically comminuted apple pomace had a particle size of ≤1.0 mm.

To determine the freely available, water-soluble sugars, 0.8 g of the apple pomace powder was placed in a 50 mL reaction vessel and filled to a volume of 40 mL with ultrapure water. This resulted in a solid content of 2% (

w/

v) during the extraction of the water-soluble saccharides. The pH was 3.6. The reaction mixture was incubated at 500 rpm and room temperature for 1 h. To quantify the extracted sugars, a 1 mL sample was transferred to a 1.5 mL reaction vessel, centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min (Heraeus Pico 21, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and the supernatant was filtered using a nylon syringe filter (pore size 0.22 µm). Finally, the solid-free sample was further diluted with ultrapure water and the concentration of water-soluble sugars was determined using high-performance anion exchange chromatography coupled with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD, see

Section 2.7).

For the determination of the structurally bound polysaccharides, the aforementioned sample was further used. First, all remaining water-soluble sugars were removed from the apple pomace solids. This was achieved by centrifuging (Biofuge Stratos, Heraeus, Hanau, Germany) the reaction mixture at 8500 rpm for 5 min, discarding the supernatant, and resuspending the solids in ultrapure water. This process was repeated three times in total, so that no water-soluble sugars could be detected in the supernatant during the third washing step. The washed apple pomace powder was dried at 60 °C until mass constant. The structural sugars were quantified by means of two-stage acid hydrolysis according to the technical report of the NREL [

53]. For this purpose, 0.3 g of washed and dried apple pomace powder was weighed into a 100 mL laboratory bottle and a magnetic stirring bar was added. The sample was mixed with 3 mL of a 72% H

2SO

4 solution, mixed thoroughly, and heated to 30 °C in a water bath for 60 min. During incubation, the sample was mixed manually every 5 min. For the second hydrolysis stage, the sample was diluted with 84 mL of ultrapure water, mixed, and autoclaved for 60 min at 121 °C and 1 bar overpressure.

After cooling, 30 mL of the sample was transferred to a beaker and the pH was adjusted to approximately 6.5 by adding CaCO3. Subsequently, 1 mL of sample was transferred to a 1.5 mL reaction vessel, centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was filtered using a nylon syringe filter (pore size 0.22 µm). The final determination of the released monosaccharides was carried out using HPAEC-PAD after further dilution of the solid-free sample with ultrapure water.

2.3. Production of Sugary Liquids from Apple Pomace

In order to make the sugars contained in apple pomace usable for biotechnological conversion to fumaric acid, a total of three different process strategies for the production of a sugary liquid were investigated. The target parameters were the presence of sugars in dissolved form, as well as a total sugar concentration of 100–130 g/L.

To determine the sugar concentration of the sugary liquids, 1 mL of sample was transferred to a 1.5 mL reaction vessel at the appropriate points, centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min (Heraeus Pico 21, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and the supernatant was filtered using a nylon syringe filter (pore size 0.22 µm). After further dilution with ultrapure water, the sample was analyzed using HPAEC-PAD.

In the additional pressing process strategy, 500 g of thawed apple pomace was placed in a hydraulic pack press (HP-2 H, Fischer Maschinenfabrik, Neuss, Germany) and pressed for 20 min at a constant pressure of 20 bar. The pressed juice separated in this process was measured gravimetrically using a scale (Model EW 6200-2NM, Kern, Balingen, Germany) placed under the outlet of the press. The press cake remaining in the press was removed manually.

- (ii)

Three-stage extraction with water

For the extraction of apple pomace with water, 500 g of thawed apple pomace was placed in a measuring cup, mixed with 250 g of ultrapure water, and stirred manually for 20 min. The extraction ratio of apple pomace to water was thus 2/1 (w/w). To separate the sugary liquid, the mixture was transferred to the hydraulic pack press and pressed at 20 bar. Pressing was stopped as soon as the originally added amount of water had been pressed out. For further extraction stages, the press cake remaining in the press was weighed, loosened by hand in a measuring cup, mixed again with ultrapure water (extraction ratio 2/1), and pressed again. A total of three extraction stages were carried out.

To increase the resulting sugar concentration, the three extracts were thermally concentrated separately from each other. For this purpose, the extracts were transferred to beakers, a magnetic stirring bar was added, and they were heated to a temperature of approx. 90 °C while being constantly mixed using a magnetic stirrer. The sugar concentration was adjusted to the desired target value through gravimetric control of the weight loss during concentration and checked by means of HPAEC-PAD analysis.

- (iii)

Combination of pressing and two-stage extraction

First, 500 g of thawed apple pomace was placed in a hydraulic pack press (HP-2 H, Fischer Maschinenfabrik, Neuss, Germany) and pressed for 20 min at a constant pressure of 20 bar. The press cake remaining in the press was removed by hand, weighed, transferred to a measuring cup, loosened by hand, mixed with the appropriate amount of ultrapure water to obtain an extraction ratio of 2/1 (w/w), and then transferred to the hydraulic pack press and pressed at 20 bar. A total of two extraction stages were carried out.

2.4. Purification of the Sugary Liquid to Apple Pomace Juice

To purify the sugary liquid produced from apple pomace, two consecutive purification steps were carried out: the precipitation of turbidity by adding CaCO3 and the separation of turbidity and ammonium using a cation exchange separation column.

In the first purification step, 200 mL of sugary liquid was placed in a 500 mL laboratory bottle and mixed with 2 g CaCO3 (1% (w/v)). The suspension was mixed for 5 min at room temperature using a magnetic stirrer and then transferred to 50 mL reaction vessels and centrifuged for 10 min at 8500 rpm (Biofuge Stratos, Heraeus, Hanau, Germany). The purified sugary liquid was separated from precipitated turbid substances and residual CaCO3 by decanting the supernatant.

For the second purification step, 20 g of cation exchanger (Dowex 50WX8, 50–100 µm particle size, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was packed into a separation column and conditioned by adding 125 mM H2SO4 solution and rinsing thoroughly with ultrapure water. After conditioning, the sugar-containing liquid was added to the separation column and a volume flow of approx. 1 mL/min was set by opening the drain valve. After the first passage of the sugar-containing liquid, the cation exchanger was regenerated with approx. 50 mL of a 125 mM H2SO4 solution and rinsed with ultrapure water until a pH value of approx. 7 was reached. The sugary liquid was then passed through the separation column a second time. The liquid purified in this way is referred to as apple pomace juice.

To determine the amount of ammonium separated, samples of the sugary liquid were taken before and after purification and analyzed using IC analysis (see

Section 2.7).

2.5. Microorganism and Inoculum Preparation

Rhizopus arrhizus NRRL 1526 was obtained from the Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection (Peoria, IL, USA). For experimental usage, the strain was stored in the form of spores in 50% glycerol at −80 °C (stock culture). For inoculum preparation, a stock culture was spread on agar plates (medium A) at 32 °C, containing 4 g/L glucose, 10 mL/L glycerol, 6 g/L lactose, 0.6 g/L urea, 0.4 g/L KH2PO4, 1 mL/L corn steep liquid, 1.6 g/L tryptone/peptone, 0.3 g/L MgSO4 × 7 H2O, 0.088 g/L ZnSO4 × 7 H2O, 0.25 g/L FeSO4 × 7 H2O, 0.038 g/L MnSO4 × H2O, 0.00782 g/L CuSO4 × 5 H2O, 40 g/L NaCl, 0.4 g/L KCl, and 30 g/L agar–agar. After six days of sporulation, the spores were suspended by adding 0.9% (w/w) NaCl solution. The resulting spore solution was stored at 4 °C until inoculation. The spore concentration was determined using a counting chamber (Thoma) and a Zeiss microscope (Axioplan, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Chemicals were either purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), Carl Roth GmbH and Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany), or Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) in an appropriate purity for biochemistry.

2.5.1. Pre-Culture Conditions

For pre-culture, 500 mL shaking flasks (unbaffled) with 50 g/L CaCO3 (precipitated, ≥99%, VWR) were sterilized (20 min at 121 °C) and then 100 mL of sterile fermentation medium B was added. The composition of medium B was 130 g/L glucose, 1.2 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.3 g/L KH2PO4, 0.4 g/L MgSO4 × 7 H2O, 0.044 g/L ZnSO4 × 7 H2O, and 0.0075 g/L FeCl3 × 6 H2O. All components of medium B were prepared separately in stock solutions and heat-sterilized; the iron solution was sterile-filtered. For inoculation, spore suspension was added to ensure an initial concentration of 1 × 105 spores/mL. Pre-cultures were carried out at 34 °C and 200 rpm in a rotary shaking flask incubator for 24 h.

2.5.2. Separate Production of Biomass

In order to obtain sufficient biomass for batch fermentation (see

Section 2.6) for the formation of fumaric acid, a two-stage pre-culture was used based on the cultivation protocol described in

Section 2.5.1 with optimized medium B. In the second process stage, a reduced concentration of 40 g/L CaCO

3 was used, deviating from

Section 2.6.1. This enabled complete consumption of the CaCO

3 used within 2 days, thereby facilitating the separation of the biomass formed up to that point. To separate the biomass from the pre-culture medium, 200 mL of sterile ultrapure water was added to each shaking flask under a sterile workbench, thereby dissolving the precipitated fumaric acid and calcium fumarate. At this point, the biomass was the only solid substance in the cultivation mixture. Once the biomass had completely settled at the bottom of the shaking flask, the supernatant was carefully removed with a serological pipette and the volume reduced to approximately 100 mL. This process was repeated a second time to further dilute the proportion of pre-culture medium. The washed biomass suspension was then transferred to a 100 mL measuring cylinder for faster sedimentation and reduced to a volume of 30 mL by removing the biomass-free supernatant using a serological pipette. The resulting inoculum size was 3.15 g/L dry biomass.

2.6. Fermentation Conditions

2.6.1. Batch Fermentations Using Pure Sugars

Batch cultivations were studied in 500 mL shaking flasks (unbaffled), each containing 50 g/L CaCO3 and 90 mL medium B at 34 °C, in a rotary incubator at 200 rpm. Glucose was replaced by alternative sugars in the respective cultivations, maintaining its initial concentration of 130 g/L. Then, 10 mL of the 24 h seed culture was transferred into the fermentation medium for inoculation. Next, 2 mL well-mixed samples were taken periodically, diluted with a 5% (w/w) HCl solution and heated to 80 °C to remove excessive CaCO3 and resolve precipitated calcium fumarate. If necessary, 20 g/L CaCO3 was added under sterile conditions during fermentation to maintain a pH value of approximately 6.0. Within all shaking flask cultivations, the weight loss due to evaporation was balanced by the addition of deionized water. All cultivations were performed in duplicate unless otherwise mentioned.

2.6.2. Batch Fermentations Using Purified Real Apple Pomace Juice

Two different cultivation strategies were investigated for the fermentative production of fumaric acid based on purified apple pomace juice. This included, on the one hand, the cultivation of

R. arrhizus NRRL 1526 with a simple pre-culture, which was carried out with optimized medium B, and, on the other hand, cultivation with separate biomass production, which was produced by means of a two-stage pre-culture. The basic procedure for both cultivation strategies is described in

Section 2.5.1 and

Section 2.5.2. In contrast to this, glucose and ultrapure water (adjusting the corresponding volume) were not added to the medium of the main culture. Instead, purified apple pomace juice was used as a base and other components of the optimized medium B were added. Depending on the experimental approach, the addition of (NH

4)

2SO

4 was omitted in some cases. After inoculation of the main culture, the cultivations were carried out at 34 °C and 200 rpm. To regulate the pH value, an initial concentration of 50 g/L CaCO

3 was used in all cultivation approaches and, if necessary, additional CaCO

3 was added.

2.7. Chromatography

Glucose, fumaric acid, other organic acids (malic acid and succinic acid), and ethanol were quantified through high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an HPX-87H ion-exclusion column (300 × 7.8 mm) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), a refractive index (RI) detector (Shodex RI-101, Shōwa Denkō, Tokyo, Japan), and an ultraviolet (UV) detector (LaChrom Elite L-2400, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at 250 nm. The column was tempered at 40 °C and eluted with a 5 mM H2SO4 solution at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. If saccharides other than glucose were present in the samples, it was not possible to analytically determine the organic acids (malic acid and succinic acid) because the corresponding HPLC signals overlap. Thus, the concentration of other organic acids could only be determined after complete metabolism of the corresponding monosaccharides.

High-performance anion exchange chromatography coupled with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) was used to determine the saccharides contained in apple pomace. The Dionex ICS-5000 system from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) used for this purpose enabled the separation and quantification of the monosaccharides glucose, fructose, xylose, galactose, mannose, arabinose, and rhamnose, as well as the disaccharide sucrose.

The system consists of the following components: AS-AP autosampler, DP (dual pump), incl. degasser, precolumn: Dionex CarboPac PA20:BioLC, 3 × 30 mm (guard), separation column: Dionex CarboPac PA20:BioLC 3 × 150 mm (analytical), column oven: DC module, ED amperometric detector, incl. a pH probe, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, Au electrode gold standard, PAD, and software: Chromeleon 7.

Measurement is performed with aqueous gradients according to the following time program: From 0 min at 0.4 mL/min: 50% H2O, 50% 10 mM NaOH; from 24 min at 0.4 mL/min: 50% H2O, 45% 200 mM NaOH, 15% 1 M sodium acetate + 25 mM NaOH; from 29 min at 0.3 mL/min: 40% 200 mM NaOH, 60% 1 M sodium acetate + 25 mM NaOH, from 34 min at 0.3 mL/min: 100% 200 mM NaOH; and from 45 min at 0.4 mL/min: 50% H2O, 50% 10 mM NaOH.

To prevent the formation of sodium carbonate, the eluents were continuously purged with helium. The samples were measured at a temperature of 30 °C and an injection volume of 1 µL. External standards were measured in each measurement series to calibrate the system.

The concentration of the cation ammonium and anion phosphate was determined through ion chromatography (IC) (Dionex ICS-100 IC, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Cations were quantified with an IonPac CS16 column (cation-IC, 5 × 250 mm) and a suppressor CSRS-500 (4 mm) at 88 mA and a temperature of 40 °C and eluted with 30 mM methyl sulfonic acid at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Anions were quantified with an IonPac AG11-HC (cation-IC, 4 × 250) and a suppressor ASRS-300 (4 mm) at 68 mA and at a temperature of 40 °C and eluted with 25 mM sodium hydroxide at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. For measurement, samples were diluted with ultrapure water, filtered using a nylon syringe filter (pore size 0.22 μm), and a sample volume of 2 mL was transferred to a Dionex Polyvial with a filter cap (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). External cation and anion multi-element standards (Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany) were measured for each series of measurements to calibrate the IC system.

2.8. Yield and Productivity

The yield is calculated from the product concentration of fumaric acid relative to the concentration of substrate consumed up to that cultivation time and is described by the product yield coefficient according to

YP/S—product yield coefficient (g/g);

cFAt—fumaric acid concentration at time t (g/L);

cS0—initial concentration of the substrate (g/L);

cSt—substrate concentration at time t (g/L).

Productivity is calculated from the quotient of the concentration of fumaric acid formed and the cultivation period required for this. Here, the maximum productivity is defined as the productivity that assumes the highest value between two sampling points.

P—productivity (g/(L∙h));

cFAt—fumaric acid concentration at time t (g/L);

cFA0—initial concentration of fumaric acid (g/L);

Δt—cultivation period (h).

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Apple Pomace

The dry matter (DM) content, residual moisture, nitrogen content, and ash content were determined using the methods described in

Section 2.2.1,

Section 2.2.2 and

Section 2.2.3. The apple pomace used had a dry matter content of 26.6 ± 0.3% and therefore a residual moisture content of 73.4%. The ash content based on dry matter was 1.2 ± 0.1% DM and the nitrogen content was 1.1 ± 0.0% DM.

The determination of the dry matter showed that, at 73.4% (

w/

w), the apple pomace examined here still contains a large amount of unpressed apple juice. In general, the ratio of dry organic matter to residual moisture found can be described as a typical result of apple pressing. Several publications dealing with the further material use of apple pomace mention residual moisture levels of 70–80% [

42,

45,

54]. Comparable values were also found in publications regarding the ash and nitrogen content of apple pomace [

42,

55].

The sugar content of apple pomace is crucial for the subsequent fermentative production of fumaric acid. In principle, the sugars contained in apple pomace can be divided into two classes: free sugars and structural sugars. Free sugars are water-soluble sugars that are already present in the substrate as mono- or disaccharides. In apple pomace, these are glucose, fructose, and sucrose. Due to the high sugar concentration of apple juice (approx. 105 g/L, direct juice from riha WeserGold), a high proportion of free sugars can be assumed for the investigated apple pomace. Structural sugars, on the other hand, are not present in their monomeric form. They are linked together via glycosidic bonds and form the structure-giving polysaccharides cellulose and hemicellulose [

42].

In order to quantify both sugar classes, the free sugars were first completely extracted with water under gentle conditions in an extraction step (see

Section 2.2.4) and analyzed (see

Section 2.7). In a second analysis step, the structural sugars were then monomerized (see

Section 2.2.4) and analyzed (see

Section 2.7) from the remaining solids. The sugar contents were determined using HPAEC-PAD analysis and are shown in

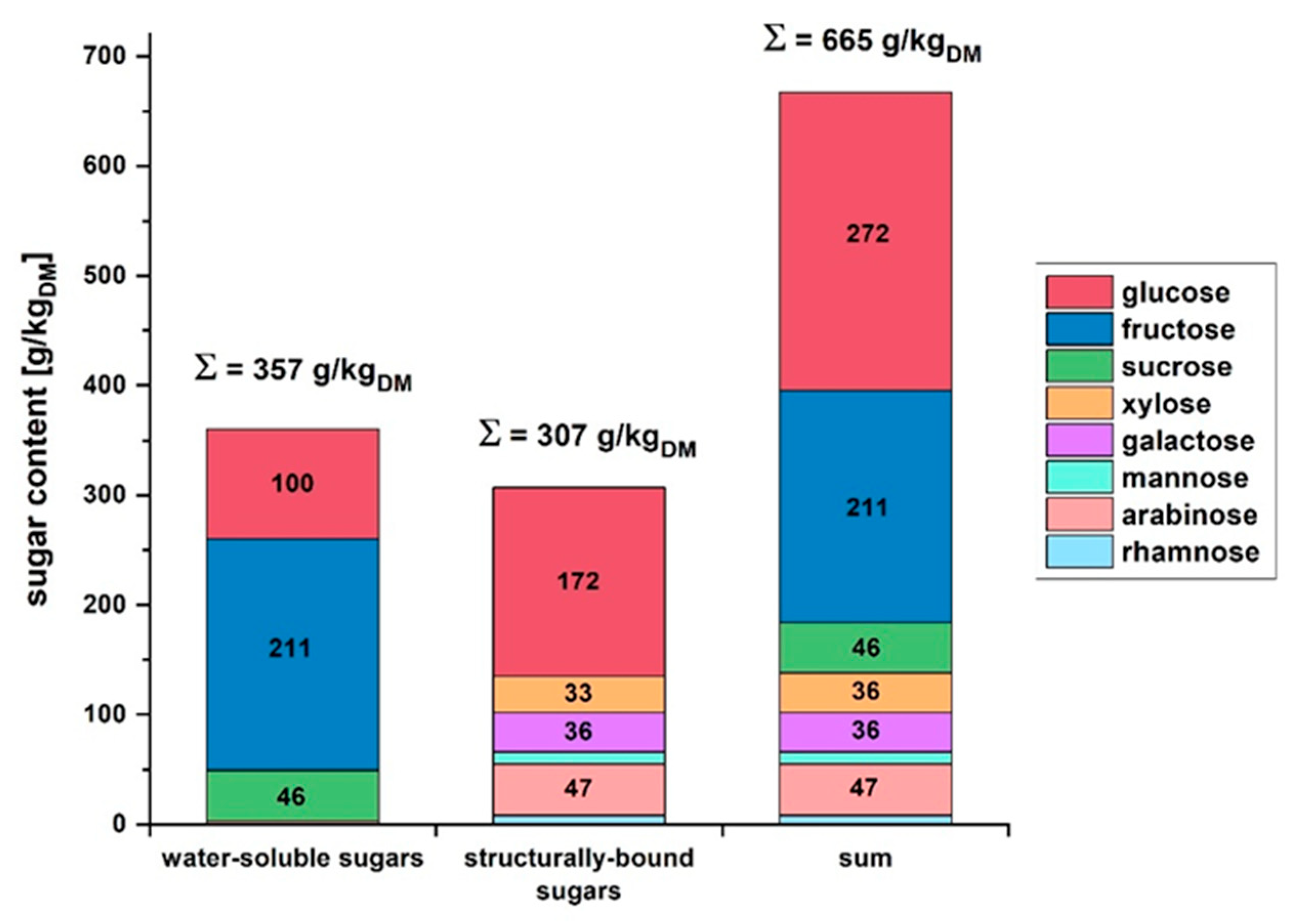

Figure 1.

The water-soluble sugars in apple pomace had a total content of 357 g/kgDM (DM = dry matter). With 211 g/kgDM, fructose formed the largest fraction, followed by glucose with 100 g/kgDM and sucrose with 46 g/kgDM. At 307 g/kgDM, the proportion of structural sugars was slightly lower than that of water-soluble sugars. Glucose, the monosaccharide of cellulose, represented the largest fraction at 172 g/kgDM. The monosaccharides of hemicellulose were detected in smaller proportions of 8–47 g/kgDM. Overall, a sugar content of 66.5% (w/w, ≙665 g/kgDM) was determined in apple pomace based on dry matter. The largest fractions of monosaccharides were glucose with 272 g/kgDM, followed by fructose with 211 g/kgDM.

Various factors, such as apple variety, growing region, and weather conditions, influence the sugar content of apples and apple pomace [

45,

51]. In addition, the process control during apple juice production has a major influence on the sugar composition of the resulting apple pomace. Pressing apples exclusively for the production of direct juice results in a high proportion of unseparated water-soluble sugars, which increases the total sugar content in the apple pomace. In contrast, apple pomace originating from the production of apple juice concentrate, has a lower proportion of water-soluble sugars due to additional extraction steps [

52]. This difference in process management limits the comparison with literature values, but comparable values for the proportion of free sugars and total sugars are found in numerous sources [

41,

42,

54].

For the use of apple pomace as a fermentation raw material for fumaric acid production, only the fraction of water-soluble sugars was used in this study. As described below, these are relatively easy to access by simple pressing and/or extraction, whereas the additional mobilization of the structural sugar fraction requires additional steps for saccharification.

3.2. Production of Sugary Liquids from Apple Pomace

Sugary liquids were produced from apple pomace that no longer contained any solid components and can serve as a carbon and energy source in fermentations with R. arrhizus NRRL 1526 to produce fumaric acid. Three different process variants were investigated for the production of a sugar-containing liquid: (i) pressing, (ii) three-stage extraction with water, and (iii) a combination of pressing followed by two-stage extraction with water.

A total concentration of 100–130 g/L sugars was set as the target value for all process variants investigated in order to achieve relevant fumaric acid titers in the subsequent batch fermentations.

The apple pomace had a residual moisture content of 73.4% (see

Section 3.1) and thus still contained a high proportion of water-soluble sugars (

Figure 1). To separate these sugars from the apple pomace solids, additional pressing was carried out at 20 bar for 20 min (see

Section 2.3). Longer pressing times of up to 30 min and the application of higher pressing pressures of 100 bar did not lead to better results. The result of the pressing shows that, based on the moist apple pomace, further separation of liquid was possible in principle.

At 20 bar, a separation of 0.29 kg/kgAP (AP = apple pomace) pressed juice was achieved after 20 min. Based on the theoretical amount of residual moisture contained, this corresponds to a pressing yield of 40%. In addition, a total concentration of 110.1 g/L sugar was detected in the pressed juice at this point. The sugar-containing liquid has the highest proportion of fructose at 65.0 g/L, followed by glucose at 36.3 g/L. In addition, 7.1 g/L of sucrose and a total of 1.7 g/L of other sugars (xylose, galactose, and arabinose) are present.

Taking into account the total concentration of sugars and the experimentally determined density of the sugary liquid of 1062.9 g/L, a total yield of 30.1 gsugar/kgAP was achieved. Based on the total amount of water-soluble sugars present in the moist apple pomace, the utilization rate was 31.7%. The process strategy of additional pressing at 20 bar is a simple variant for producing a sugar-containing liquid based on apple pomace. Compared to the process variants discussed below, the low process effort is particularly advantageous. The separated press juice already had a high sugar concentration of 110 g/L. Additional concentration of the liquid, which would have a negative impact on process costs, was therefore not necessary.

- (ii)

Three-stage extraction with water

As a second process strategy, extraction of the water-soluble sugars using water was investigated. In preliminary tests, an ideal extraction ratio of 2/1 (w/w, apple pomace/water) was determined. After mixing the mixture, it was pressed at 20 bar to separate the sugary liquid until the originally added amount of water was separated. In order to separate much more of the water-soluble sugars, this extraction process was repeated a total of three times. The sugar concentrations achieved in the respective extracts were as follows:

Extract 1: 45.8 g/L fructose, 20.4 g/L glucose, 4 g/L sucrose and other sugars (Σ = 70.2 g/L).

Extract 2: 28.2 g/L fructose, 13.6 g/L glucose, 2.1 g/L sucrose and other sugars (Σ = 43.9 g/L).

Extract 3: 18.4 g/L fructose, 8.2 g/L glucose, 1.4 g/L sucrose and other sugars (Σ = 28.0 g/L).

The addition of water reduced the concentration of water-soluble sugars in the apple pomace. This resulted in lower total sugar concentrations of 70.2 g/L in Extract 1, 43.9 g/L in Extract 2, and 28.0 g/L in Extract 3. It should be noted that despite different total concentrations, the relative ratio of the individual saccharides remained constant. All extracts contained 65% fructose and 30% glucose.

As the sugar concentration in the three extracts was below the target concentration of at least 100 g/L, the extracts were heated separately in an open system to approx. 90 °C and thus concentrated. The three concentrates were then combined and the sugar concentration was determined using HPAEC-PAD analysis. The resulting concentrate was found to have a total concentration of 123.4 g/L sugar, with 82.5 g/L fructose, 35.5 g/L glucose, and 5.4 g/L sucrose and other sugars. The proportional composition of the individual sugars yielded a result comparable to the sugar ratio before concentration.

Concentration at 90 °C is a simple way to increase the sugar content in low-concentration liquids. In terms of total yield, this process variant allowed a total of 70.4 gsugar/kgAP to be transferred to the sugary liquid. This corresponds to an efficiency of 74.2% based on the fraction of water-soluble sugars. Compared to pressing apple pomace alone, this result represents an increase of approximately 230%. However, in order to achieve this efficiency, a significantly increased process effort was required (three-stage pressing and thermal concentration of the three extracts).

- (iii)

Combination of pressing followed by two-stage extraction with water

As described above, additional pressing is a simple way to separate a sugary liquid from solid components of the apple pomace. Therefore, in this combined production strategy, the apple pomace was first hydraulically pressed at 20 bar for 20 min. This yielded an identical press yield with a sugar concentration of 109.6 g/L in the press juice, composed of 70.9 g/L fructose, 32.7 g/L glucose, and 6 g/L sucrose and other sugars. The pressed apple pomace was then used to perform two further extractions of the remaining water-soluble sugars. An extraction ratio of 2:1 (w/w, pressed apple pomace/water) was again used for this purpose. The added water was separated after a contact time of 20 min by pressing at 20 bar. This yielded the following extracts:

Extract 1: 42.7 g/L fructose, 16.7 g/L glucose, 3.5 g/L sucrose and other sugars (Σ = 62.9 g/L).

Extract 2: 24.1 g/L fructose, 11.1 g/L glucose, 2 g/L sucrose and other sugars (Σ = 37.2 g/L).

Since both extracts had a sugar concentration of <100 g/L, they were concentrated separately and then combined with the pressed juice. The resulting liquid contains a total concentration of 135.8 g/L sugar with a composition of 87.4 g/L fructose, 39.7 g/L glucose, and 8.7 g/L sucrose and other sugars.

In terms of the composition of the individual sugars, fructose accounted for the largest fraction at 64%, followed by glucose at 29%. In contrast, the proportion of sucrose and other monosaccharides was significantly lower at 5% and 2%, respectively. A comparison of this result with previous process variants shows that the same sugar ratio was achieved in all manufacturing processes. The type of separation and optional thermal concentration therefore has no influence on the proportional sugar composition. Overall, a total yield of 69.9 gsugar/kgAP was achieved, corresponding to a utilization rate of water-soluble sugars of 73.6%. This combined process achieves an almost identical utilization rate to the three-stage extraction with water process strategy but is less complex in terms of thermal concentration.

In principle, the absolute sugar concentration of the liquid can be varied as desired by means of integrated thermal concentration within the manufacturing process. With regard to fermentative bioconversion to fumaric acid, this enabled the desired concentration of total sugars to be specifically adjusted. The pressing and 2-stage extraction process variant is therefore considered to be the best one investigated here and was used for further experiments.

3.3. Purification of the Sugary Liquid from Apple Pomace

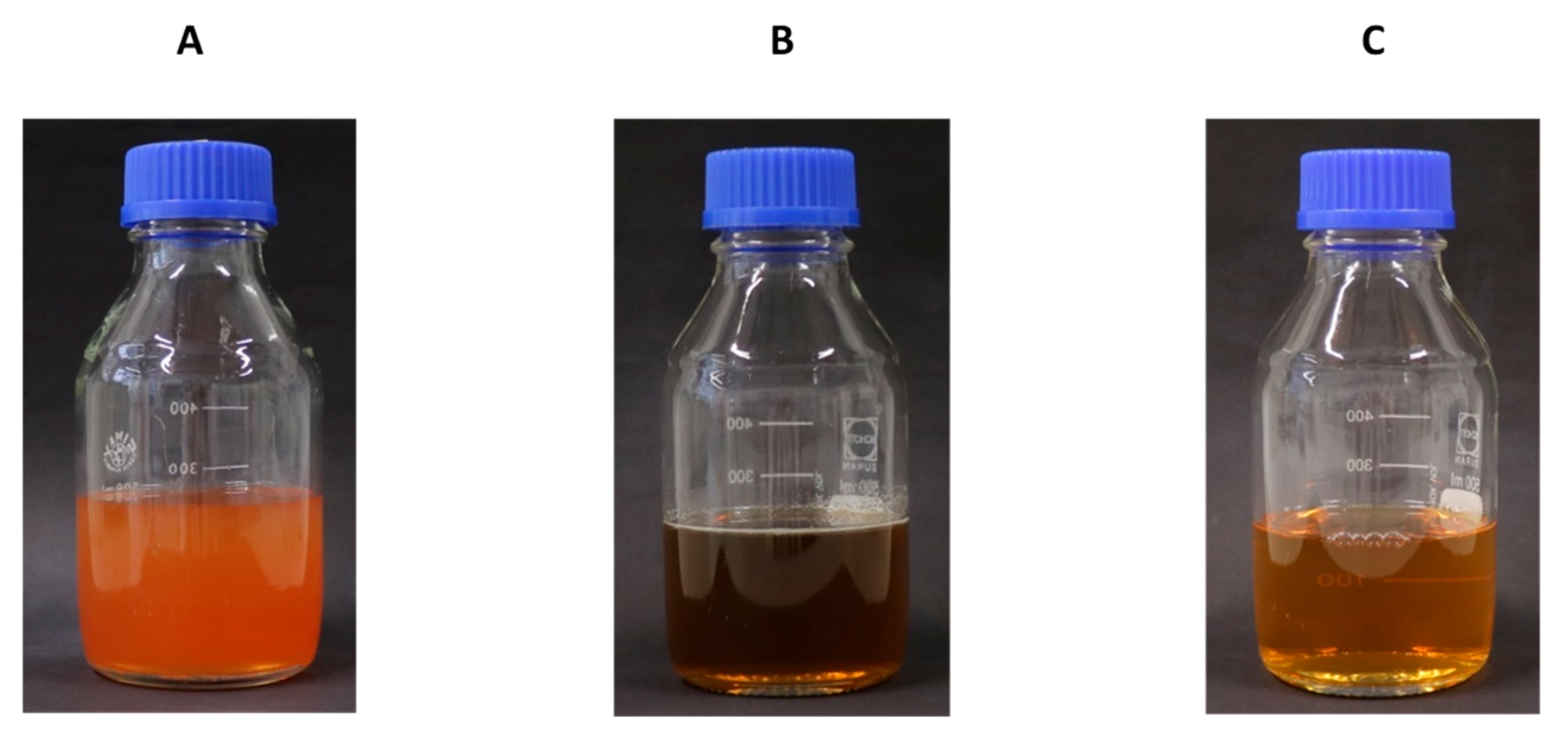

The sugar-containing liquid produced through additional pressing of apple pomace, followed by two-stage extraction with water, is shown in

Figure 2A. In addition to a clearly visible orange color, the presence of turbidity within the liquid was also qualitatively detected.

Calcium carbonate is used to regulate the pH value in the fermentative production of fumaric acid with R. arrhizus NRRL 1526. In this context, the precipitation of a solid substance was observed in preliminary tests with calcium carbonate and unpurified sugary liquid. In the corresponding cultures, this caused a sharp increase in viscosity and thus prevented sufficient oxygen supply to the biomass present. Therefore, effective production of fumaric acid was not possible.

In order to reduce the viscosity of the cultivation mixture and thus potentially promote the formation of fumaric acid, the turbidity was removed in an upstream process step. For this purpose, 1% (w/w) calcium carbonate was added to the sugary liquid and the mixture was stirred for 5 min. As the reaction progressed, discoloration of the mixture could be observed. As a side effect of this reaction, the pH value of the sugary liquid rose from an initial value of 3.6 to a value of 6.3.

To remove the precipitated turbidity and the remaining CaCO

3, the reaction mixture was centrifuged. The separated liquid is shown in

Figure 2B and, compared to the original sugar-containing liquid, exhibited a distinct brown color and lower turbidity. This process step resulted in a 1.8% decrease in the absolute sugar concentration. The specific composition of the individual saccharides was not changed. Further treatment with CaCO

3 did not result in any further precipitation of turbidity. Thus, a solid content of 1% (

w/

w) is sufficient to achieve the maximum possible separation of turbidity in this way.

In order to achieve further removal of turbidity, the sugar-containing liquid was further purified in a second process step. For this purpose, a separation column was filled with the cation exchanger Dowex 50WX8 and the liquid to be purified was passed through the column. Due to the dense packing of the separation material, turbidity was separated by means of filtration on the one hand. On the other hand, positively charged molecules were bound to the cation exchanger and thus removed from the liquid. By passing the precipitated sugary liquid through the separation column twice and regenerating the cation exchanger in between, the purified apple pomace juice shown in

Figure 2C was obtained.

In contrast to the original sugary liquid, the purified apple pomace juice was a clear, slightly orange-colored liquid. This demonstrated a further separation of turbidity substances in terms of quality. The concentration of growth-relevant ammonium was reduced from 10.3 mg/L to 2.7 mg/L. This is a significant side effect in terms of growth-decoupled fumaric acid production. The presence of nitrogen-containing compounds leads to biomass growth, whereas nitrogen limitation hinders growth and thus promotes growth-decoupled fumaric acid production [

56]. Through the twofold use of the cation exchange column, a decrease in the original sugar concentration of 4.8% was detected, which is acceptable. The proportional composition of the sugars, however, remained unchanged.

3.4. Cultivation with Sugars Contained in Apple Pomace Juice

The sugary liquids from apple pomace obtained through the processes described in

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3 contain fructose and glucose as their main components (in total >90%) as well as small amounts of sucrose, xylose, galactose, and arabinose as other sugars (in total <10%). In order to test the extent to which fumaric acid production is possible based on the main components fructose and glucose, cultivations were first carried out using only these substrates. The sole use of the other sugars sucrose, xylose, galactose, and arabinose as substrates was not pursued. Instead, for comparison purposes, cultivation was also carried out using a synthetic apple pomace medium consisting of 63.7% fructose, 30.4% glucose, 4.2% sucrose, 0.9% xylose, 0.5% galactose, and 0.3% arabinose. This synthetic medium closely resembles the compositions of the sugary liquids obtained from apple pomace described above.

Two strategies were used for the cultures. One is the cultivation with pre-culture using the optimized medium B, as already described in Kuenz et al. [

18], whereby the glucose concentration of 130 g/L in the cultivations with fructose or the synthetic apple pomace medium was replaced by the respective other saccharides (see

Section 2.5.1). Secondly, a cultivation strategy with an upstream separate two-stage biomass production (see

Section 2.5.2), which in principle can enable fumaric acid production decoupled from biomass growth.

3.4.1. Cultivation with Pre-Culture

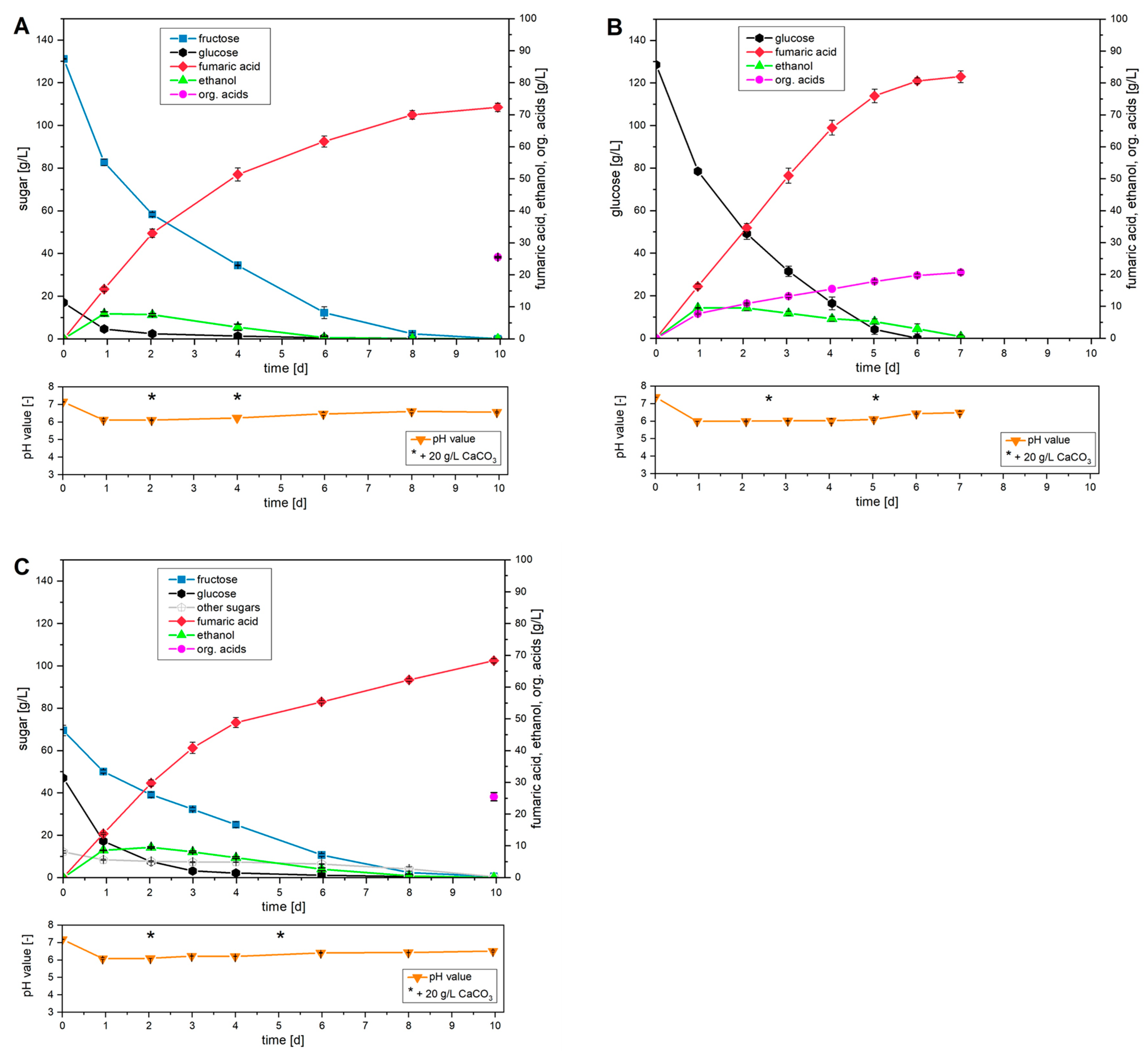

The results of the cultures based on the various saccharides with an initial saccharide concentration of 130 g/L in each case are shown comparatively in

Figure 3. For the cultures based on fructose and the synthetic apple pomace medium, glucose is present in a slightly higher concentration, as some glucose is introduced into the main culture through inoculation with the pre-culture. For these two cultures, it should be noted that no organic acid curve can be plotted over the course of the culture (see

Section 2.7). The total amount of organic acids formed as a by-product is given for the end of the culture, as no fructose was present at this point anymore and reliable quantification was therefore possible.

During cultivation with fructose (

Figure 3A), a final concentration of 72.3 g/L fumaric acid was detected after a period of 10 d and complete consumption of fructose. It is interesting to note that at the start of cultivation and during the presence of added glucose, a constant fumaric acid productivity of 0.68 g/(L∙h) was observed within the first two days. However, after complete metabolism of the glucose added via the pre-culture, a decline in productivity was documented with continued consumption of fructose. This behavior thus indicates a favored production of fumaric acid in the presence of low concentrations of glucose. Overall, a total productivity of 0.30 g/(L∙h) and a yield of 0.49 g/g were achieved in this cultivation.

Cultivation with glucose showed a different qualitative course. After one day, a concentration of 16.3 g/L fumaric acid was detected, along with the accumulation of other organic acids and a maximum ethanol concentration of 9.5 g/L. In the further course, the cultivation system showed a stable productivity of fumaric acid of 0.70 g/(L∙h) up to a cultivation period of 4 d. From this point on, a decline in productivity could be detected as glucose limitation set in. After complete metabolism of the glucose supplied, an average productivity of 0.56 g/(L∙h) was determined after 6 days. With a final concentration of 80.7 g/L fumaric acid, this corresponds to a yield of 0.63 g/g.

When using the synthetic apple pomace medium, a high decrease in glucose concentration was detected within the first day. In contrast, the consumption of fructose and other sugars showed a lower metabolism rate. Thus, the cultivation strategy used here proves that glucose was the preferred monosaccharide of R. arrhizus NRRL 1526. In terms of fumaric acid production, a productivity of 0.51 g/(L∙h) was detected within the first four days in the presence of glucose. However, as cultivation progressed and glucose was completely depleted, a decline in productivity was observed. This behavior confirms the previous assumption that the presence of glucose has a positive effect on fumaric acid production using other sugars. Overall, after a cultivation period of 10 days and complete metabolism of all sugars supplied, a final concentration of 68.3 g/L fumaric acid was achieved. Productivity over the entire course of cultivation was 0.29 g/(L∙h), and the total yield was 0.53 g/g.

The influence of different sugar mixtures on the production behavior of

Rhizopus sp. has also been described in the literature. For example, Papadaki et al. investigated the influence of a sugar mixture of 50% glucose and 50% fructose [

27]. With an initial sugar concentration of 50 g/L, a concentration of 30.8 g/L fumaric acid was achieved in this publication. Based on the cultivation process, a preference for glucose over fructose was observed, a finding that was also made by Martin-Dominguez et al. [

57]. A preference for glucose over other sugars has also been described for cultivations comprising xylose [

25,

58,

59].

The biomass in all cultivations shown in

Figure 3 exhibited a comparable loose mycelial morphology, which has proven to be advantageous for fumaric acid formation [

18]. Any differences that occurred can therefore be directly attributed to the use of different sugar types and concentration ratios.

A comparison shows that glucose achieved the best production performance with a yield of 0.63 g/g, whereas the yield was only 0.49 g/g when fructose was used, a decrease of approximately 25%. Although the use of the synthetic apple pomace medium shows a slightly improved yield of 0.53 g/g compared to fructose, it does not reach the yield achieved with glucose alone.

In addition to a lower yield, reduced overall productivity was also observed when alternative sugars were used. For example, at comparable initial sugar concentrations with glucose, complete conversion was detected after a cultivation period of 6 days. Cultivation with fructose required a period of 10 days for this. This is reflected in a productivity reduction of approximately 45%. In this context, an additional increase in glucose concentration (synthetic apple pomace medium) did not result in an increase in productivity.

Based on these results, a ranking of the various monosaccharides tested can be established. The monosaccharide glucose is best suited for the fermentative production of fumaric acid under the cultivation conditions investigated here. This is followed by fructose, which yielded lower yields and productivity in cultivation but can in principle be used for the production of fumaric acid.

3.4.2. Cultivation with Separate Biomass Production

In order to investigate the influence of growth-decoupled fumaric acid production when using alternative sugars, the cultivation strategy with separate biomass production according to

Section 2.5.2 was applied. For this purpose, biomass was first grown using a two-stage pre-culture and then freed from the pre-culture medium and washed. The biomass suspension produced in this way was used to inoculate the main culture, in which further biomass growth was prevented by nitrogen limitation. To ensure the formation of loose mycelial morphology during the two-stage pre-culture, only glucose was used in these process steps. The subsequent washing of the biomass completely removed any remaining glucose. In contrast to the cultivation strategy with pre-culture described above, this allowed the production behavior to be investigated without additional glucose input.

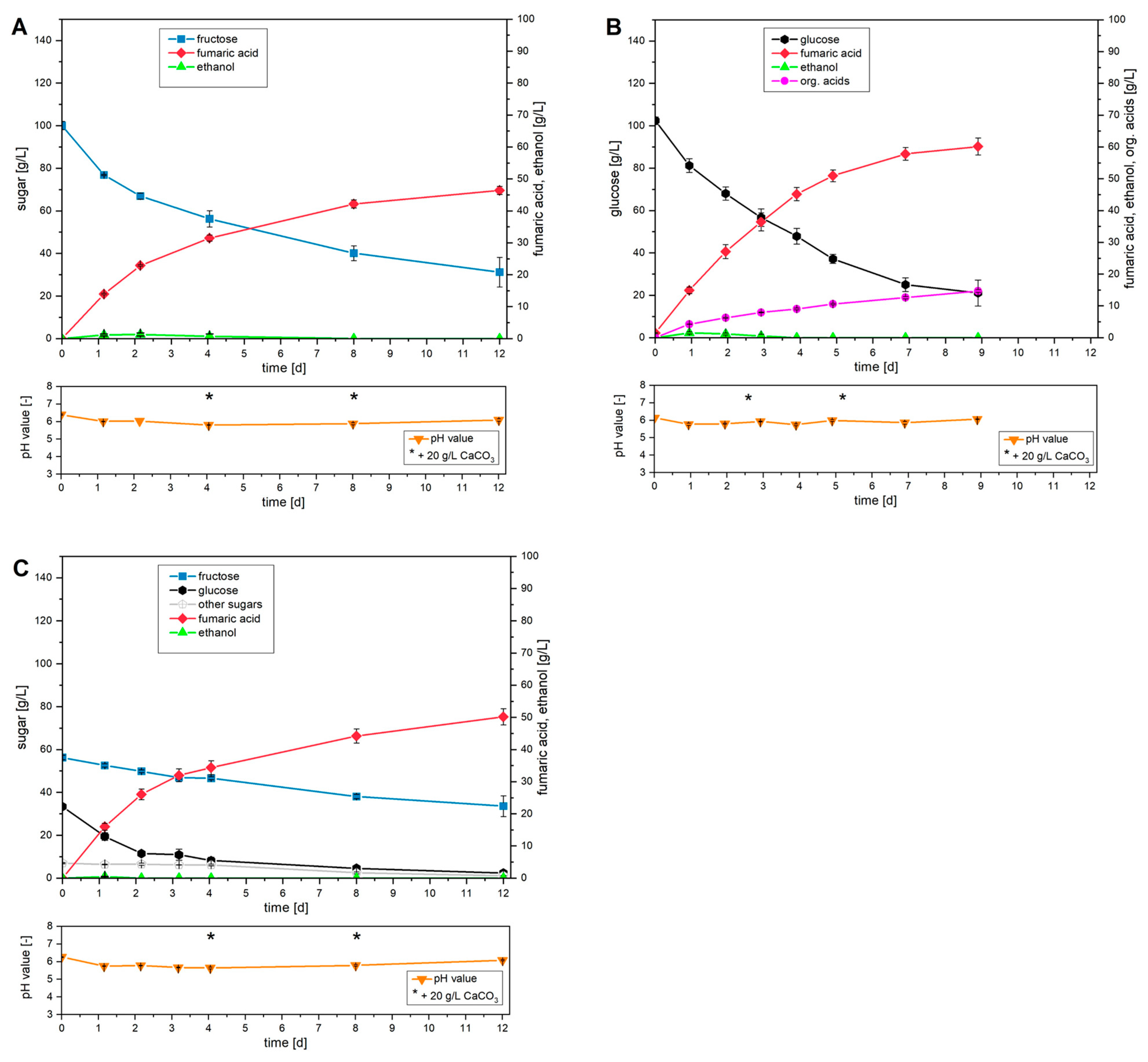

The cultivation curves obtained using the monosaccharides fructose and glucose as well as the sugar mixture of the synthetic apple pomace medium are shown comparatively in

Figure 4. An initial saccharide concentration of 100 g/L was selected in each case.

Using only fructose at the start of cultivation, a high level of metabolism of this monosaccharide was observed. However, the decrease in fructose declined as cultivation progressed. After a cultivation period of 12 days, the conversion was only 69% of the fructose initially used. In line with the metabolism of fructose, an increased concentration of fumaric acid was detected at the start of cultivation, which decreased steadily as cultivation progressed. After 12 days, a final titer of 46.4 g/L fumaric acid was achieved. The total productivity was 0.16 g/(L∙h) and the yield was 0.67 g/g.

Cultivation with glucose alone also did not allow for complete conversion of the initial glucose concentration of 100 g/L within the cultivation period studied. However, within 7 days, approximately 75% of the original amount of glucose used could be metabolized. This enabled the production of 57.8 g/L fumaric acid, with a yield of 0.73 g/g and a total productivity of 0.35 g/(L∙h).

Using synthetic apple pomace medium, comparable production behavior was documented during cultivation. Within the first three days, increased fumaric acid productivity was observed, mainly due to the metabolism of glucose. After the glucose was almost completely depleted and the fructose concentration continued to decrease linearly, a decline in productivity was detected. This resulted in a final concentration of fumaric acid of 50.2 g/L after 12 days. To produce this concentration of fumaric acid, a total of 62% of the sugars were metabolized. A comparison of the metabolism rates for the different monosaccharides used illustrates the preferred use of glucose. Thus, 93% of the glucose initially supplied was consumed during cultivation. Fructose and the sum of the other sugars showed lower metabolism rates of 40% and 84%, respectively. Overall, synthetic apple pomace medium showed an almost identical total productivity of 0.17 g/(L∙h) after 12 days compared to the use of fructose alone. However, compared to cultivation with glucose, this corresponds to a reduction in productivity of approximately 50%. The very high yield of 0.82 g/g achieved with synthetic apple pomace medium is particularly noteworthy. Compared to cultivation with glucose, this represents an improvement of 23%.

In terms of the morphology achieved, the formation of loose and individual mycelium flocs was observed in all cultivation approaches.

In principle, the cultivation strategy involving separate biomass production and subsequent, growth-decoupled fumaric acid production is suitable for fructose, glucose and the sugars found in apple pomace. In all three of these cultivations, the yields achieved using the separate biomass cultivation strategy were higher than those achieved using the pre-culture strategy. It can therefore be concluded that growth-decoupled production of fumaric acid enabled significantly increased yields. Furthermore, since the achieved yields exceed the theoretical value of 0.64 gFA/gsugar for the oxidative TCA cycle, it can be concluded that the sugars were partially metabolized through the reductive TCA cycle, in which CO2 originating from the supplied CaCO3 was fixed. However, it should be noted that this cultivation strategy permits only very slow sugar metabolism. Compared to corresponding cultivations with pre-culture, this results in low overall productivity, limiting the effectiveness of the process as a whole.

3.5. Fumaric Acid Production from Purified Apple Pomace Juice

3.5.1. Cultivation with Pre-Culture

To produce fumaric acid from purified apple pomace juice, a cultivation strategy involving a pre-culture was initially employed. This first involves cultivating the biomass of R. arrhizus NRRL 1526 in a pre-culture with an optimized medium containing glucose as the carbon source. For the subsequent main culture, 90 mL of apple pomace juice with an initial sugar concentration of 130 g/L was placed in a 500 mL shaking flask without baffles, to which the trace elements contained in optimized medium B and 0.3 g/L KH2PO4 were added. In the initial cultivation approach, 1.2 g/L (NH4)2SO4 was also added. To regulate the pH value, 50 g/L of CaCO3 was also added to the mixture.

This first cultivation approach, conducted over 7 days, resulted in low metabolic rates of the sugars. Glucose was completely metabolized after five days, whereas fructose and the other sugars could not be fully metabolized even after seven days. Only very low fumaric acid production (10.8 g/L) was detected after seven days, whereas ethanol was the main product formed (22.1 g/L after seven days). Correspondingly, the yield was low (0.10 g/g), as was the productivity (0.06 g/(L·h)). Although the biomass used for inoculation had the preferred mycelium structure, the biomass grown in the main culture formed large clumps with the inoculated biomass and thus favored ethanol production over fumaric acid production.

To reduce biomass growth, no (NH4)2SO4 was added to the main culture in a second cultivation. This means that the biomass used does not have any knowingly added ammonium available for further growth. All other cultivation conditions were the same as in the first approach. However, the biomass again formed clumps during cultivation. These were slightly smaller than in the first approach, resulting in lower ethanol production (6.2 g/L after seven days) and higher fumaric acid production (16.9 g/L after seven days). Nevertheless, only 42% of the initially present sugars had been converted after seven days. Glucose showed the highest metabolism rate within the individual sugar fractions, which decreased after a cultivation period of one day. Taking into account the sugars converted during this cultivation period, this equates to a yield of 0.33 g/g, with a total productivity of 0.10 g/(L·h). Overall, these two cultivation approaches with pre-cultures did not meet expectations and were not pursued further for use with real apple pomace juice.

3.5.2. Cultivation with Separate Biomass Production

Since the cultivation strategy with pre-culture described above did not enable effective production of fumaric acid, the cultivation strategy with separate biomass production was applied. For this purpose, biomass was first grown in optimized medium B and glucose as a carbon source using a two-stage pre-culture. The biomass, which was in the form of loose mycelium, was then removed from the pre-culture medium, washed, and concentrated. In the main culture, 100 mL of purified apple pomace juice was placed in a 500 mL shaking flask without baffles and mixed with the trace elements contained in optimized medium B and 0.3 g/L KH

2PO

4. The addition of ammonium in the form of (NH

4)

2SO

4 was omitted. To regulate the pH value, 50 g/L CaCO

3 was used. This cultivation batch was inoculated by adding 30 mL of concentrated biomass suspension. At the start of the main culture, the initial concentration of dry biomass was therefore 3.15 g/L. Based on this procedure, the production behavior of

R. arrhizus NRRL 1526 was investigated with two apple pomace juices of different concentrations with initial sugar concentrations of 90 g/L and 150 g/L, respectively (

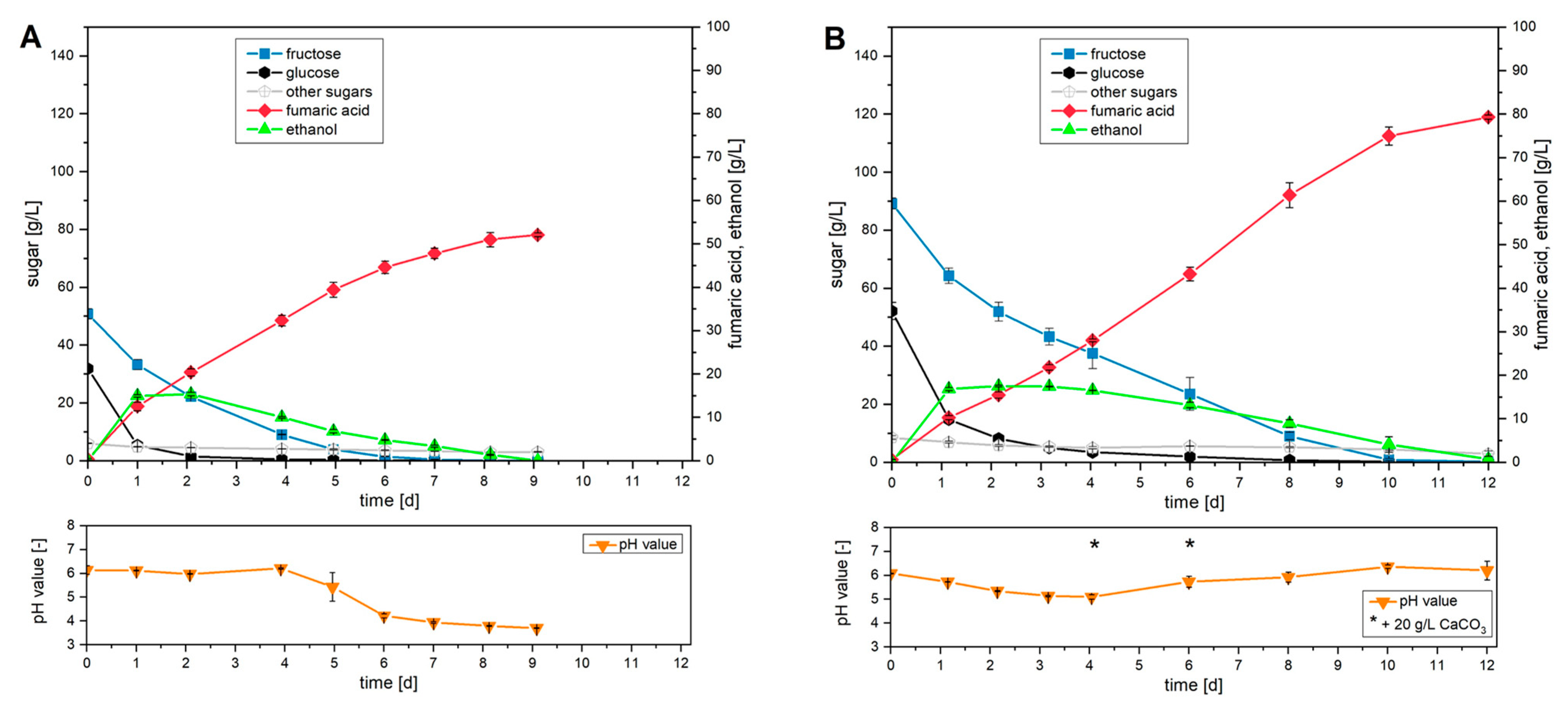

Figure 5).

In terms of the specific metabolism of the individual sugar fractions at an initial sugar concentration of 90 g/L (

Figure 5A), the strongest decrease was observed for the monosaccharide glucose after a cultivation period of 1 d. In contrast, fructose and, above all, the sum of other sugars showed a reduced metabolism rate. The preferred use of glucose was also reflected in the further course of cultivation. After a cultivation period of 2 days, 5% of the initial glucose concentration was still present in the cultivation mixture. In contrast, only 56% of the fructose and 25% of the other sugars originally supplied were metabolized during the same period. Sucrose in particular, which represented the largest proportion of the other sugars, could not be metabolized by

R. arrhizus NRRL 1526 in this cultivation approach. In contrast to glucose and fructose, no complete consumption of the other sugars was detected within the period investigated. The use of separately grown biomass thus enabled the metabolism of 97% of the initially present sugars within 9 days. With regard to the production of fumaric acid, the maximum productivity of 0.51 g/(L∙h) was detected within the first day, which decreased as cultivation progressed. The total productivity of the cultivation was 0.24 g/(L∙h). Taking into account the final titer of 52.1 g/L fumaric acid and the sugar converted for this purpose, a total yield of 0.60 g/g was achieved. Due to the increasing concentration of fumaric acid, the calcium carbonate used (50 g/L) was completely depleted after a cultivation period of 5 days. This can be demonstrated by a falling pH value from this point in the cultivation process.

This cultivation can be compared with that based on synthetic apple pomace medium (see

Section 3.4,

Figure 4), as both approaches used the same cultivation strategy with separate biomass production and a comparable concentration of the individual sugar fractions. The differences can therefore be directly attributed to the use of real apple pomace juice. In both cultivations, a comparable production behavior of fumaric acid was observed, which continued to decline after an initially high productivity. At the end of cultivation, both approaches showed a fumaric acid concentration of approximately 50 g/L. However, differences were observed in terms of overall productivity and yield. In the cultivation described herein using apple pomace juice, almost complete conversion of all sugars present was achieved within 9 days. This resulted in a productivity of 0.24 g/(L∙h) and a yield of 0.60 g/g. In contrast, cultivation with synthetic apple pomace medium resulted in significantly reduced sugar metabolism, which did not allow for complete conversion after 12 days. As a result, comparatively less sugar was used to produce the same amount of fumaric acid. This is reflected in an approximately 35% increase in yield (0.82 g/g). However, since this required a relatively longer cultivation period, cultivation with synthetic apple pomace medium resulted in an approximately 30% lower overall productivity of 0.17 g/(L∙h).

Since the initially present glucose and fructose could be completely metabolized during cultivation with 90 g/L total sugar, the influence of an increased initial sugar concentration was investigated in a second cultivation (

Figure 5B). The additional concentration required for this was carried out during the production of the sugary liquid and thus before purification to apple pomace juice. After adding the biomass suspension, an initial total concentration of 150 g/L sugar was adjusted in the cultivation batch. This provided

R. arrhizus NRRL 1526 with a concentration of 89.2 g/L fructose, 52.1 g/L glucose, and 8.5 g/L other sugars for the production of fumaric acid.

The increased initial sugar concentration successfully extended the cultivation period. Complete metabolism of glucose did not occur until after 8 days. Complete conversion of fructose was observed after 10 days. In contrast, complete utilization of sucrose could not be detected in this cultivation either. Thus, at the end of cultivation, 35% of the fraction of other sugars originally used was still present in the cultivation mixture. Overall, after a cultivation period of 12 days, 98% of all sugars initially present were metabolized. This successfully demonstrated that this cultivation approach also allows the metabolism of larger amounts of sugar. Overall, a concentration of 79.3 g/L fumaric acid was detected after 12 days in this cultivation approach. This corresponds to a total productivity of 0.27 g/(L∙h) with a yield of 0.54 g/g. Compared to cultivation with apple pomace juice and a sugar concentration of 90 g/L, total productivity was thus increased by 13%. In contrast, the use of an increased sugar concentration resulted in a 10% lower yield.

In summary, the use of real apple pomace juice thus provided an effective way of converting the sugars contained in apple pomace into fumaric acid with an acceptable decrease in yield. This means that apple pomace, an agricultural residue, can be used as a suitable raw material for fermentative conversion to fumaric acid.

A comparison with other results described in the literature on the fermentative production of fumaric acid based on alternative sugars from residues using non-genetically modified microorganisms is shown in

Table 1 so that the results presented herein can be classified comparatively.

The values shown in

Table 1 can only be compared to a limited extent, as not all studies specify the relevant parameters of final titer, yield, and productivity. In addition, not all studies aimed to optimize fermentative fumaric acid production. Often, only the general usability of the substrates used was tested, or a screening for other microorganisms capable of producing fumaric acid was carried out. Further limitations in comparability result from different cultivation forms (shake flask or bioreactor) and initial substrate concentrations used.

Nevertheless, the values presented allow for a cautious classification of the results obtained in this study. Based on these results, the final titers achieved in the fermentations are currently the highest described through the use of alternative raw material sources (compared to the widely employed raw material glucose). In terms of yield, the yields achieved in the present study are in the upper range. The productivities achieved in the present case, however, are in the middle to lower range. Further research efforts are thus required to improve these values while maintaining high yields and final titers.

Overall, it can be concluded that the results described herein clearly demonstrate the efficient use of apple pomace, an agricultural residue, for the fermentative production of fumaric acid and represent a significant improvement compared to other studies using apple pomace for this purpose. This opens up another promising avenue for adding value to the still largely unused agricultural residue apple pomace.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, apple pomace was used as the raw material to provide carbohydrates, which were then used as a substrate in the fermentative production of fumaric acid with the wild-type fungus Rhizopus arrhizus NRRL 1526. The apple pomace used originated from direct apple juice production and contained high levels of free (i.e., non-structurally bound) and water-soluble carbohydrates. Three different processes were compared to obtain these carbohydrates: pressing, extraction, and a combination of the two. The best process option in terms of low process effort and high sugar yield was found to be pressing at 20 bar for 20 min, followed by a two-stage extraction with a 2:1 ratio (w/w) of apple pomace to water. After thermal concentration and mixing, the liquids were purified through (i) precipitation with CaCO3, followed by (ii) passing twice through an anion exchanger. This process resulted in a purified real apple pomace juice consisting of approximately 65% fructose, 30% glucose, and 5% other sugars, with adjustable total sugar concentrations. Cultivations were carried out using either the sole carbohydrates fructose and glucose or synthetic and real apple pomace juice. Two cultivation strategies were applied: one using a pre-culture approach, and the other using separate upstream biomass production to enable growth-decoupled fumaric acid production. It was proven that, although glucose is the preferred substrate for Rhizopus arrhizus NRRL 1526, fructose can also be readily metabolized, albeit with slightly lower fumaric acid titers, yields, and productivities. Using the pre-culture approach, a fumaric acid titer of 68.3 g/L was achieved, with a yield of 0.53 g/g and a productivity of 0.29 g/(L·h), using synthetic apple pomace juice as the substrate. The cultivation strategy involving separate biomass production enabled growth-decoupled fumaric acid production from both synthetic and real apple pomace juice. When synthetic apple pomace juice was used, 50.2 g/L of fumaric acid was produced, with an outstanding yield of 0.82 g/g and a productivity of 0.17 g/(L·h). This proves that fumaric acid is partially produced by the reductive TCA cycle. Using real apple pomace juice as the substrate resulted in the production of 79.3 g/L of fumaric acid, with a yield of 0.54 g/g and a productivity of 0.27 g/(L·h). Thus, the fumaric acid titers reported in the present study are the highest reported to date based on substrates other than pure glucose. Overall, the results of the present study clearly demonstrate the efficient use of apple pomace for the fermentative production of fumaric acid, representing a significant improvement compared to other studies using apple pomace for this purpose. This opens up another promising avenue for adding value to the largely unused agricultural residue apple pomace.