Computational Investigation of Mechanism and Selectivity in (3+2) Cycloaddition Reactions Involving Azaoxyallyl Cations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

3. Results and Discussion

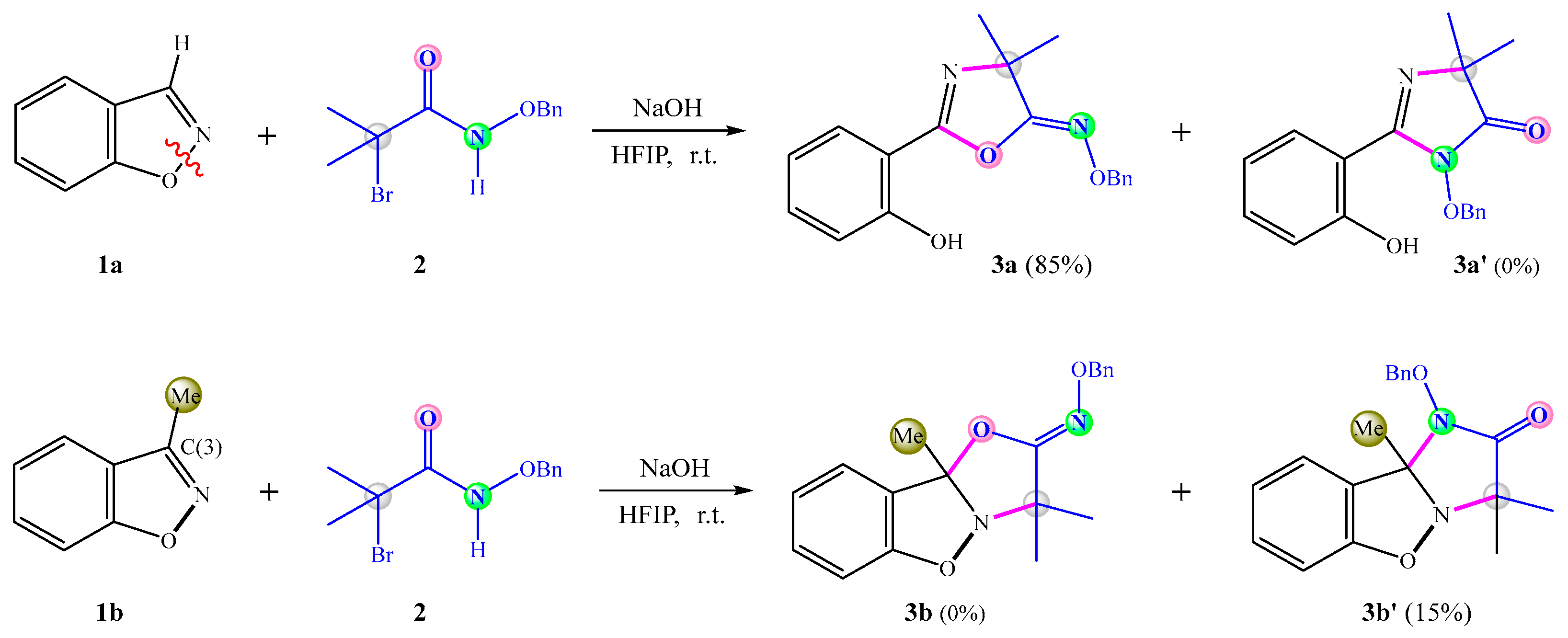

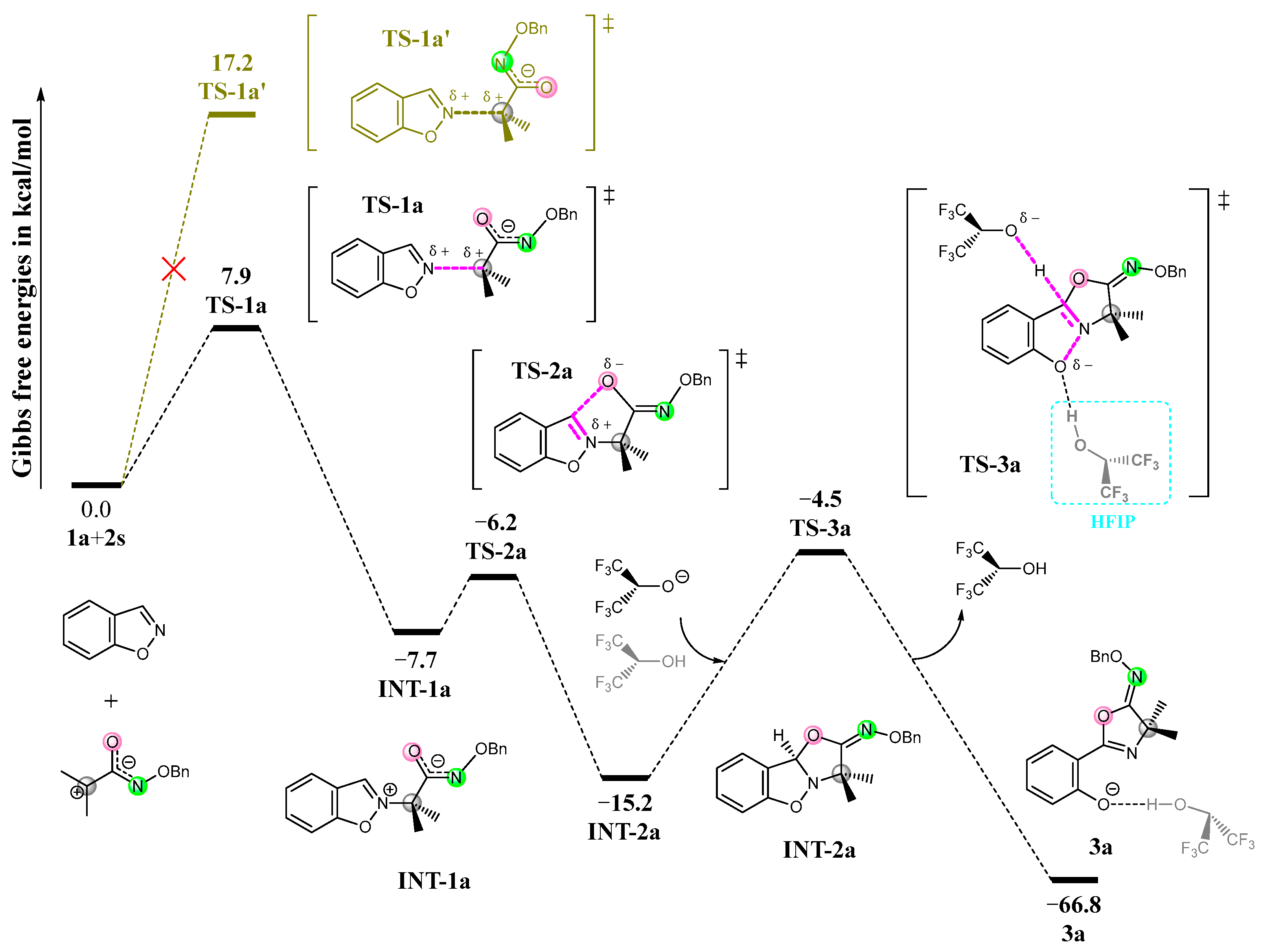

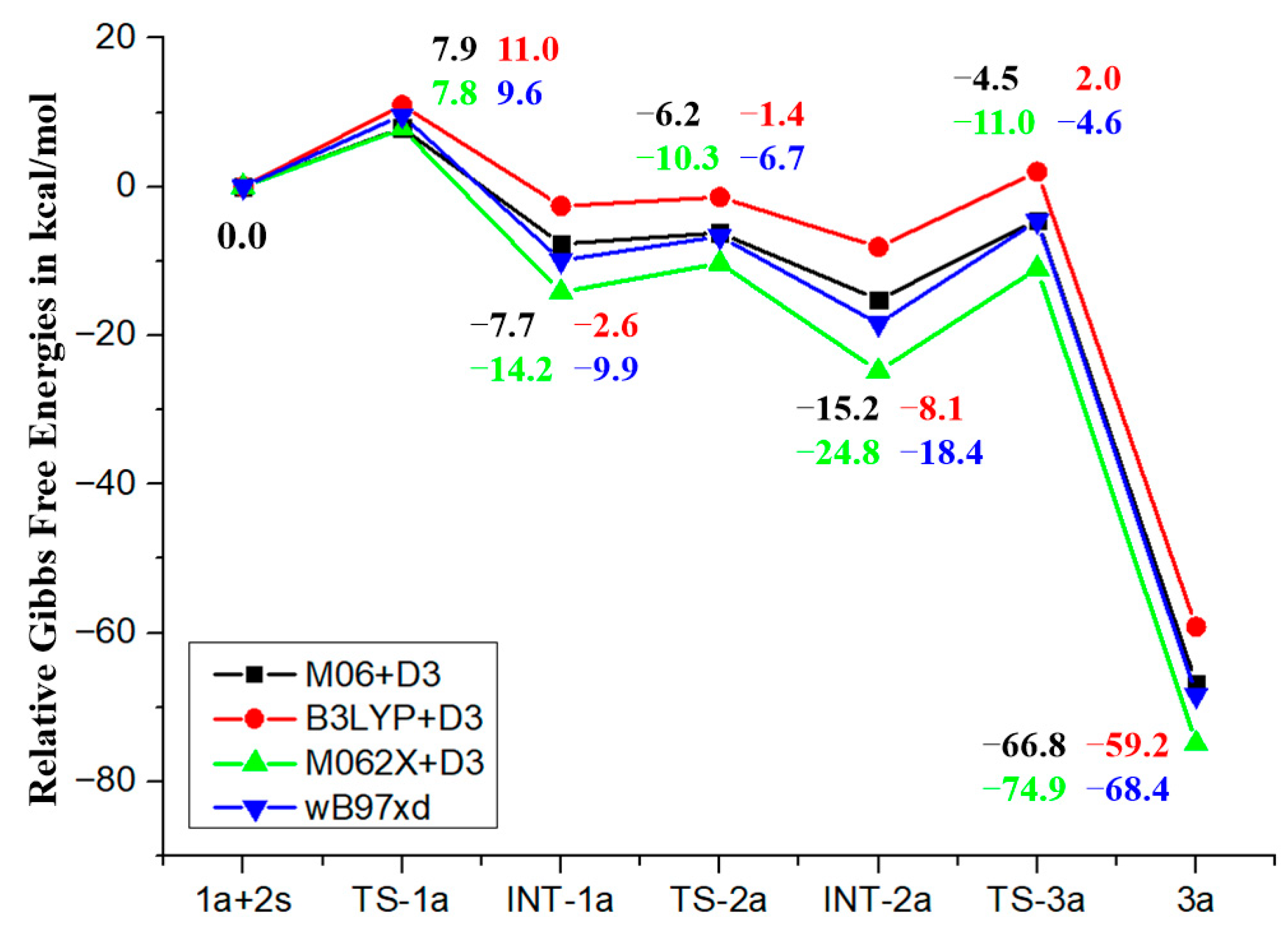

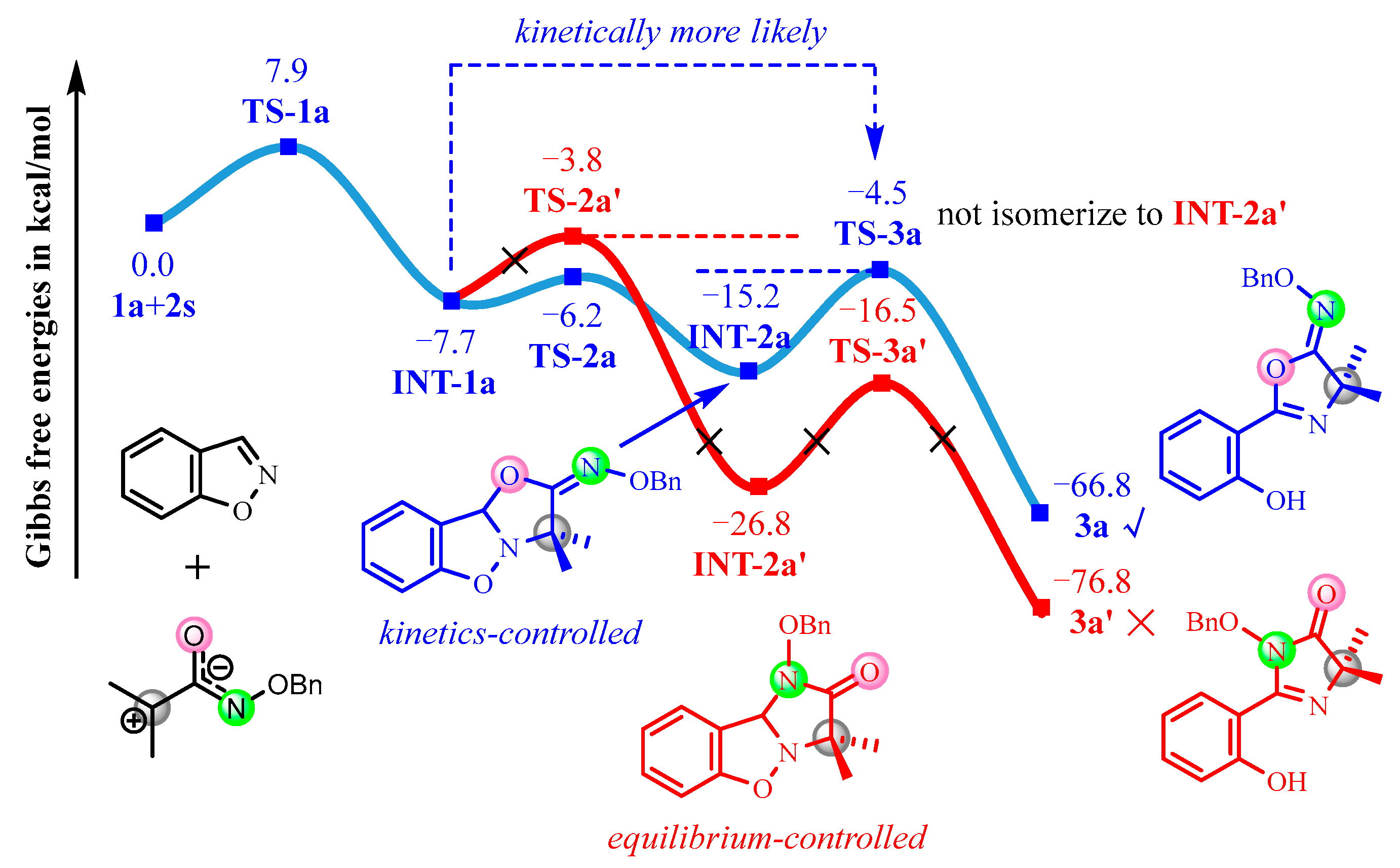

3.1. Mechanism and N/O Selectivity for the 1a+2 Reaction

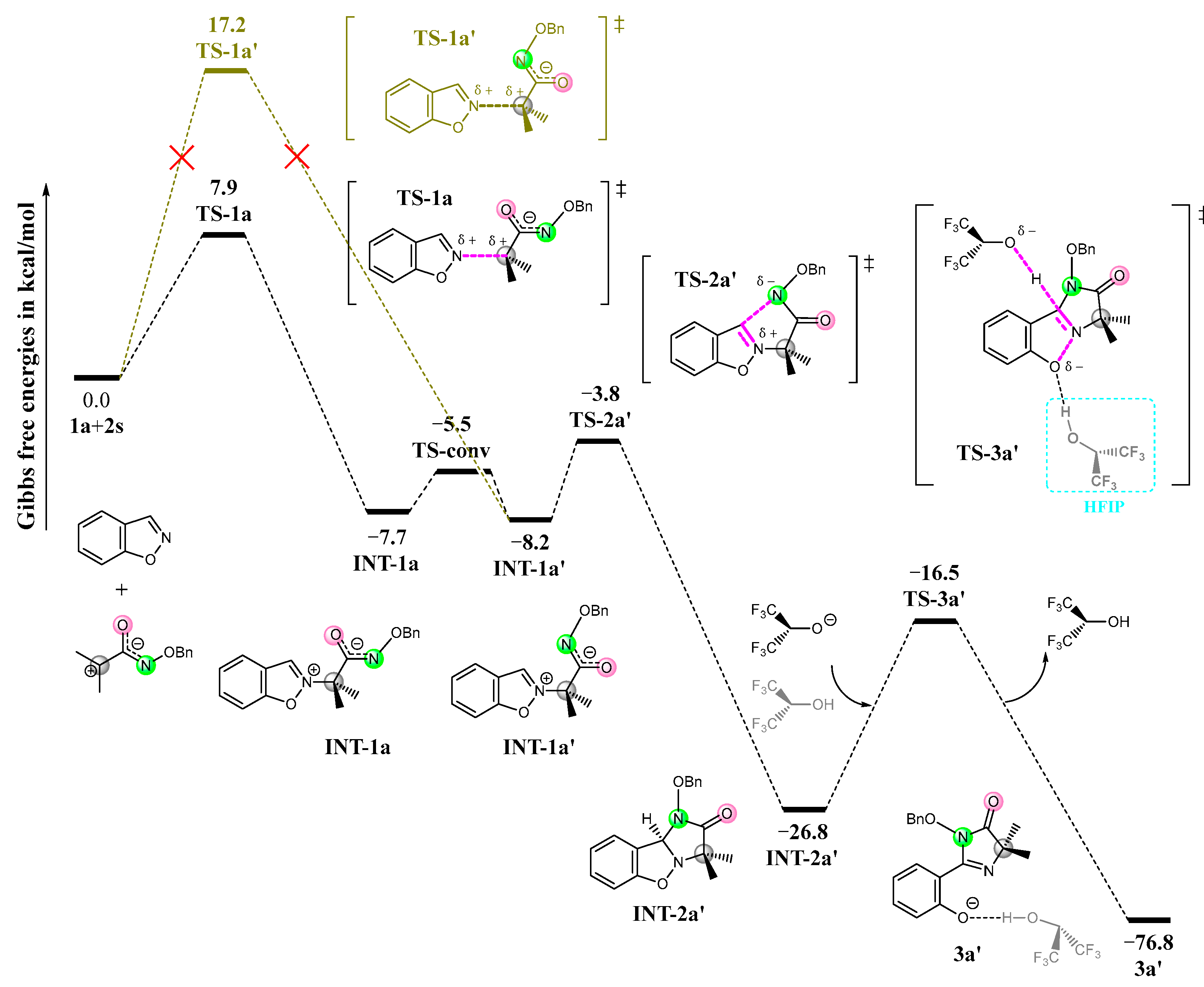

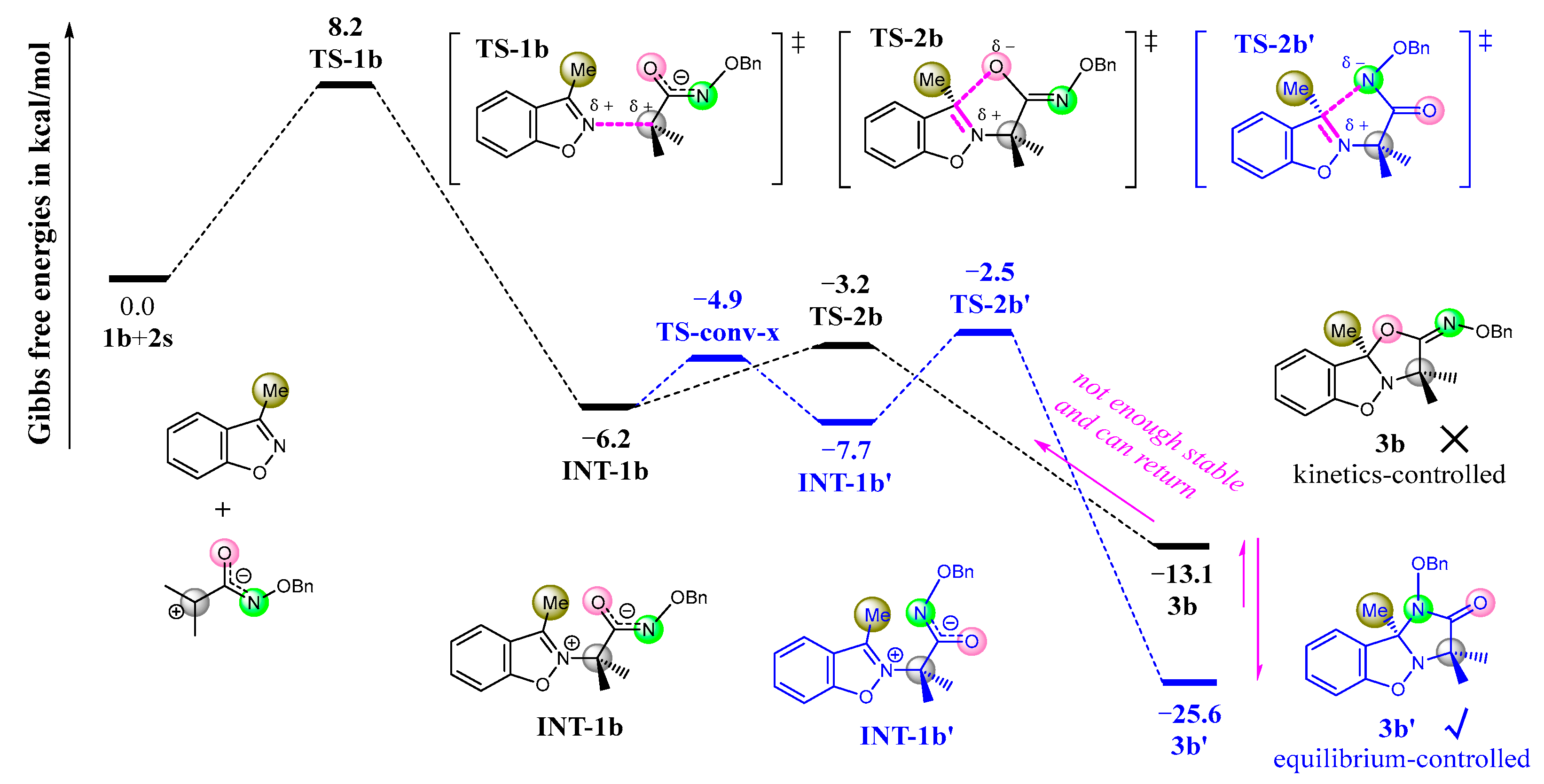

3.2. Mechanism and N/O Selectivity for the 1b+2 Reaction

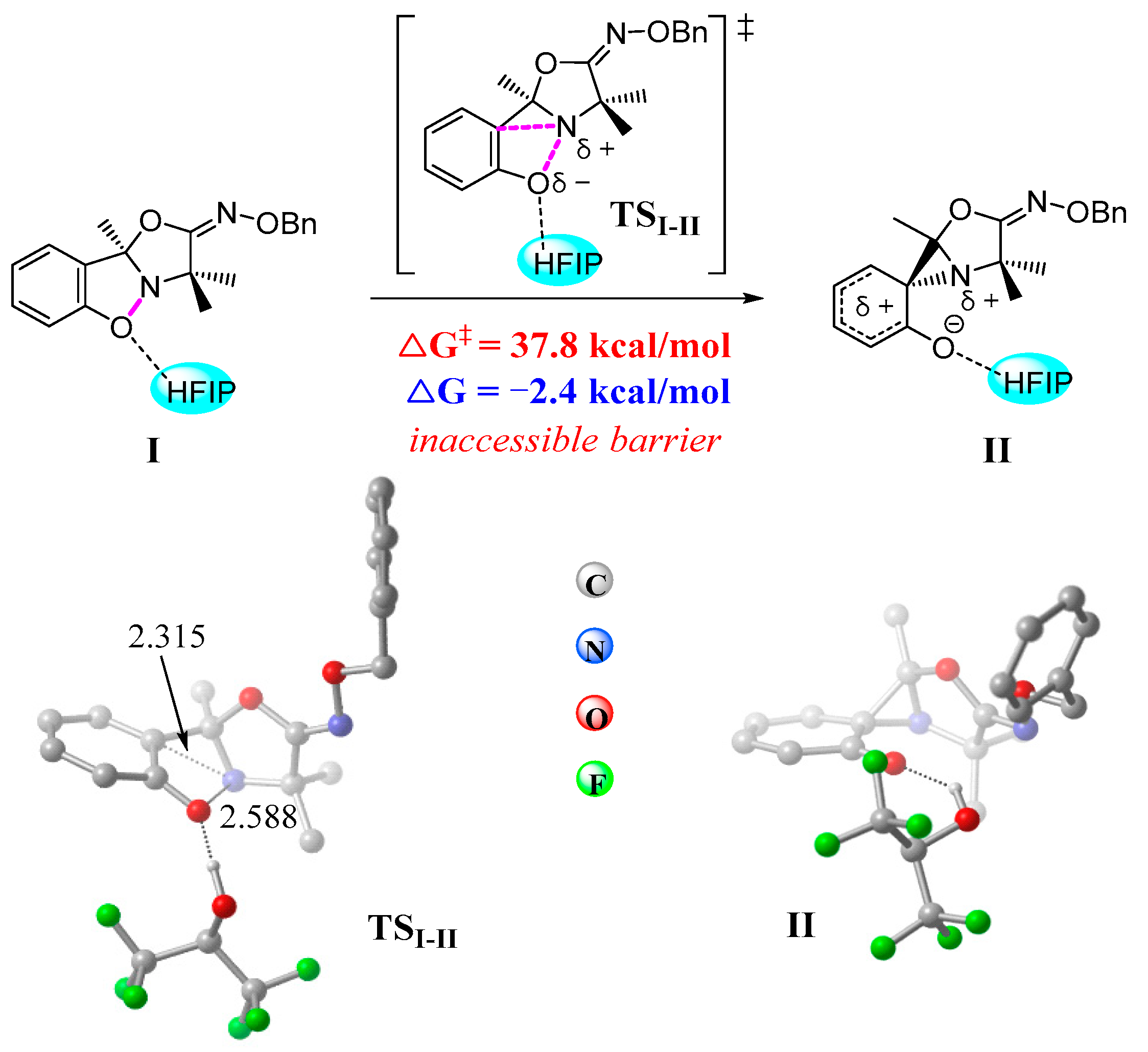

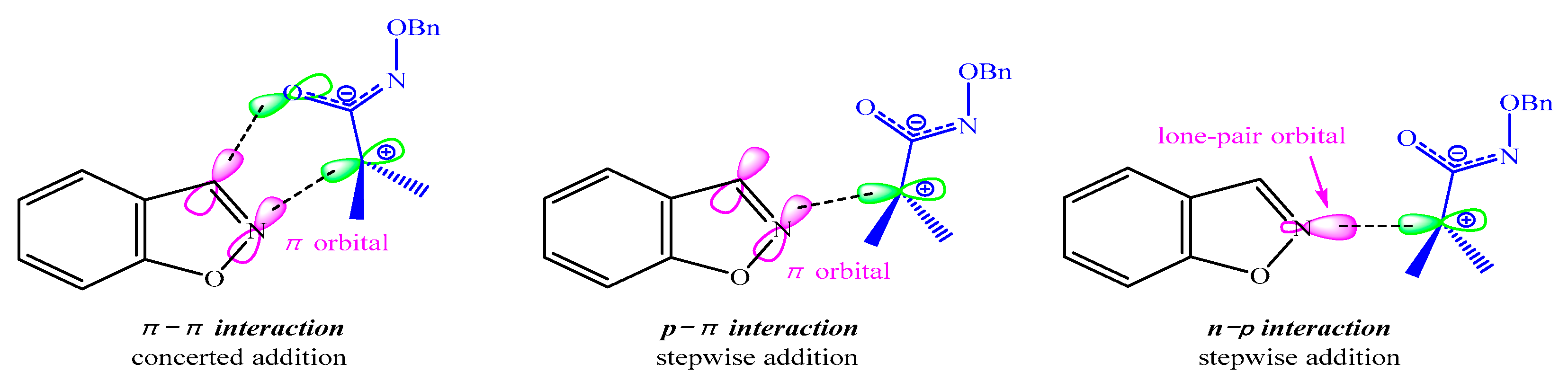

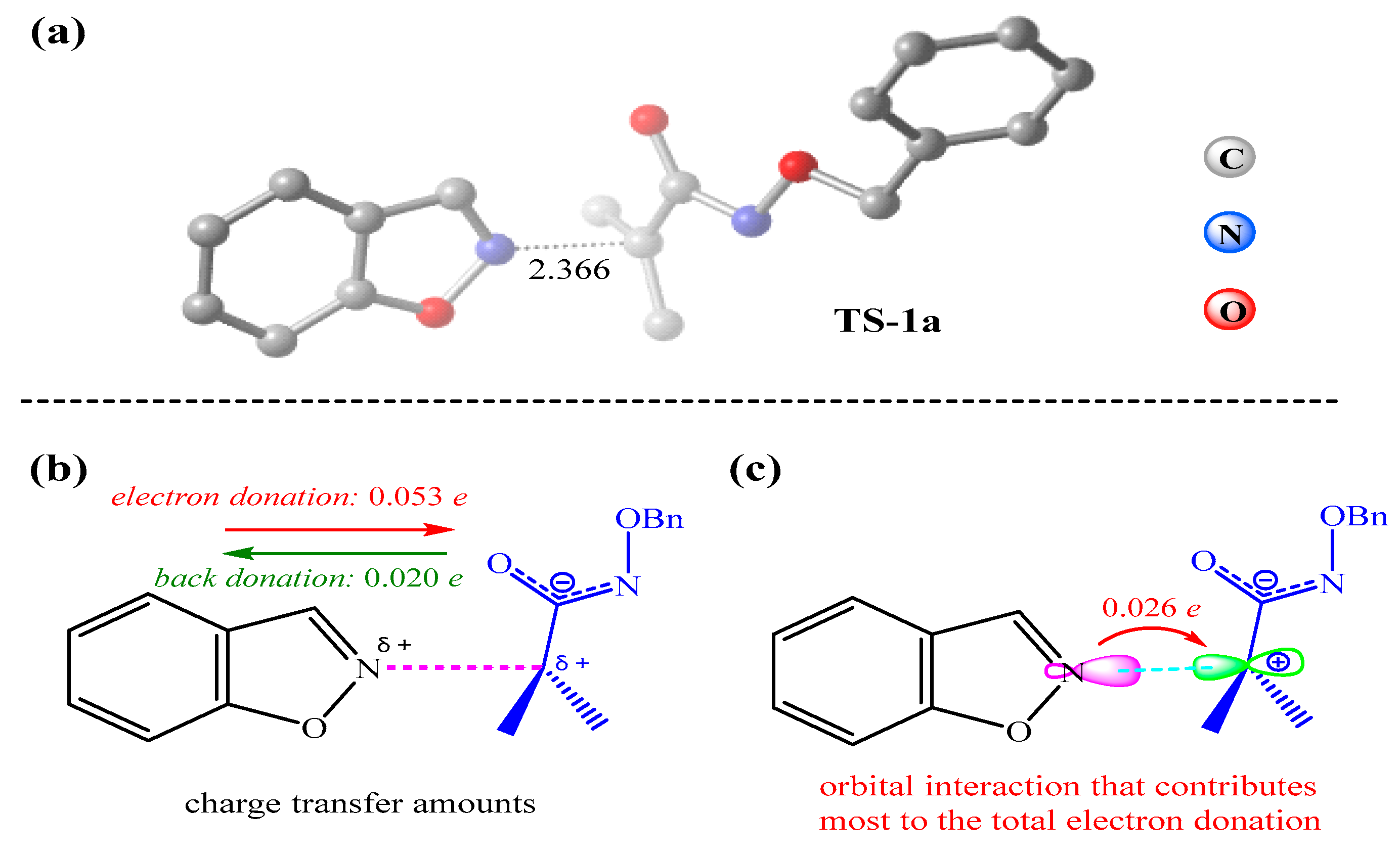

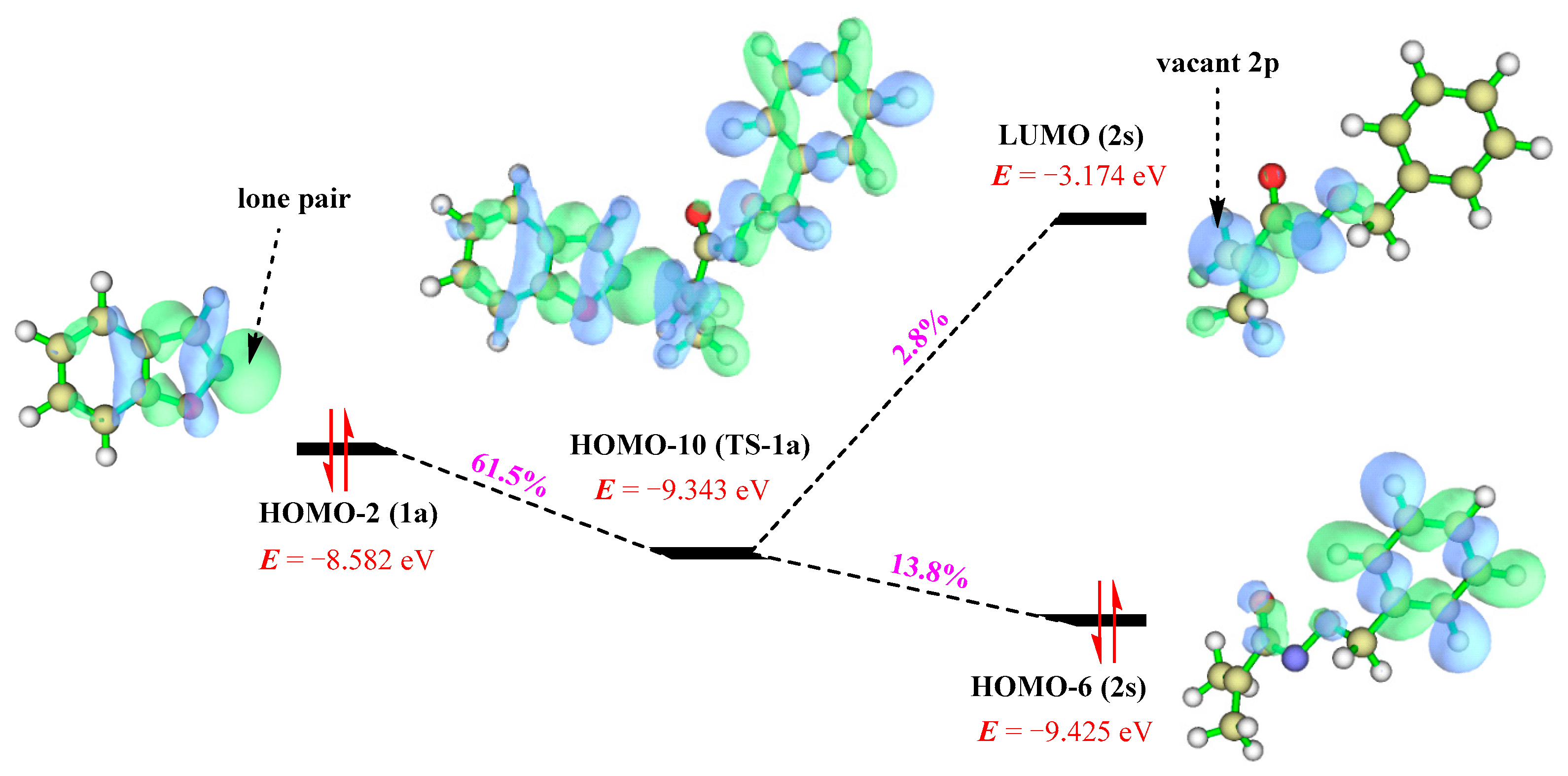

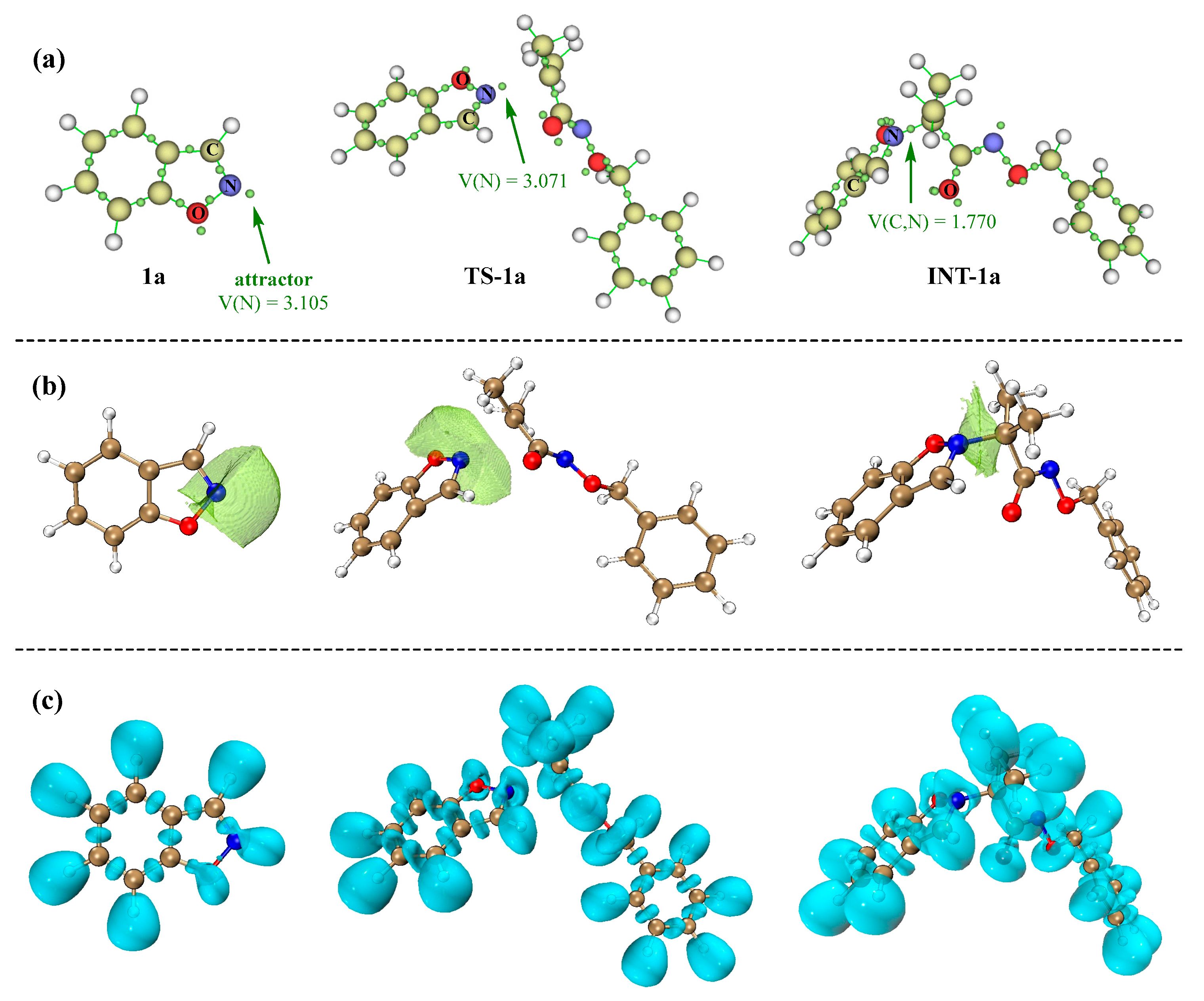

3.3. Electronic and Structural Analyses on (3+2) Cycloaddition of Azaoxyallyl Cations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xuan, J.; Cao, X.; Cheng, X. Advances in heterocycle synthesis via [3+m]-cycloaddition reactions involving an azaoxyallyl cation as the key intermediate. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 5154–5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, G.; Liu, B. Research progress on [3 + n] (n ≥ 3) cycloaddition of 1,3-diploes. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 40, 3132–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, S.G. HFIP-mediated decarboxylative [4 + 3]-annulation of azaoxyallyl cations with isatoic anhydride. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 3594–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.-G. Stereoselective [4+3]-cycloaddition of 2-amino-β-nitrostyrenes with azaoxyallyl cations to access functionalized 1,4-benzodiazepin-3-ones. Molecules 2024, 29, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.-J.; Li, Q.-Z.; Xiang, P.; Qi, T.; Dai, Q.-S.; Jia, Z.-Q.; Gou, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.-L. Diastereoselective [3 + 1] cyclization reaction of oxindolyl azaoxyallyl cations with sulfur ylides: Assembly of 3,3’-Spiro[β-lactam]-oxindoles. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zou, J.; He, Z.-L. Diastereoselective synthesis of pyrazolo [1,2-a] [1,2,4] triazine derivatives via cross-1,3-dipolar cyclizations of azaoxyallyl cations with N,N’-cyclic azomethine imines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Patel, M.; Biswas, A.; Hazra, S.; Saha, J. 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoroisopropanol-promoted synthesis of structurally diverse alkylidene-4-thiazolidinones/selenazolidinones involving an azaoxyallyl cation. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 2715–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.; Singh, B.; Bera, T.; Singh, V.P.; Priyasha, P.; Das, D. Construction of spiropyrroloindolines by dearomative [3+2]-cycloaddition of indoles with oxindole-embedded azaoxyallyl-cations. Synlett 2023, 34, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Duari, S.; Maity, S.; Roy, A.; Elsharif, A.M.; Biswas, S. (3 + 2) Cycloaddition of 2-alkoxynaphthalenes with azaoxyallyl cations: Access to benzo[e]indolones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 8400–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.-Q.; Sun, J.-T. [3 + 2]-Cycloaddition of azaoxyallyl cations with hexahydro-1,3,5-triazines: Access to 4-imidazolidinones. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 2745–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bouakher, A.; Martel, A.; Comesse, S. α-Halogenoacetamides: Versatile and efficient tools for the synthesis of complex aza-heterocycles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 8467–8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Pi, C.; Wu, Y.; Cui, X. Ring opening [3+2] cyclization of azaoxyallyl cations with benzo[d]isoxazoles: Efficient access to 2-hydroxyaryl-oxazolines. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhao, M.; Lin, X. [3 + 2]-Cycloaddition of azaoxyallyl cations with 1,2-benzisoxazoles: A rapid entry to oxazolines. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 9548–9560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Ansari, A.J.; Rajagopala Reddy, S.; Kanti Das, G.; Singh, R. Mechanistic investigations for the formation of active hexafluoroisopropyl benzoates involving aza-oxyallyl cation and anthranils. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2020, 9, 2136–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, P.; Guillade, L.; González-Pérez, A.B.; de Lera, A.R. Computational studies on the formation of aza-oxypentadienyl intermediates from alkylidene oxaziridines and keteneimine oxides and their conversion to 1, 5-dihydropyrrolones. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2019, 119, e25796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balde, B.; Force, G.; Marin, L.; Guillot, R.; Schulz, E.; Gandon, V.; Leboeuf, D. Synthesis of cyclopenta[b]piperazinones via an azaoxyallyl cation. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7405–7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPoto, M.C.; Hughes, R.P.; Wu, J. Dearomative indole (3 + 2) reactions with azaoxyallyl cations–new method for the synthesis of pyrroloindolines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 14861–14864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. A computational study on cycloaddition reactions between isatin azomethine imine and in situ generated azaoxyallyl cation. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision, C.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Scalmani, G.; Frisch, M.J. Continuous surface charge polarizable continuum models of solvation. I. General formalism. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 114110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, K. The path of chemical reactions-the IRC approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 1981, 14, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hratchian, H.P.; Schlegel, H.B. Using Hessian updating to increase the efficiency of a Hessian based predictor-corrector reaction path following method. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005, 1, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comp. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Supramolecular binding thermodynamics by dispersion-corrected density functional theory. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 9955–9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.-Y.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Kang, J. Comparison of phosphonium and sulfoxonium ylides in Ru(II)-catalyzed dehydrogenative annulations: A density functional theory study. Molecules 2025, 30, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Lu, T. Generalized charge decomposition analysis (GCDA) method. J. Adv. Phys. Chem. 2015, 4, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D.; Edgecombe, K.E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legault, C.Y. CYLView, 1.0b; Universite de Sherbrooke: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics, Version 1.9.4a55; University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign: Champaign, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, G.; Ma, X.; Meng, X. Computational Investigation of Mechanism and Selectivity in (3+2) Cycloaddition Reactions Involving Azaoxyallyl Cations. Reactions 2025, 6, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040070

Zhou W, Zhang L, Liu G, Ma X, Meng X. Computational Investigation of Mechanism and Selectivity in (3+2) Cycloaddition Reactions Involving Azaoxyallyl Cations. Reactions. 2025; 6(4):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040070

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Wei, Lei Zhang, Guixian Liu, Xiaosi Ma, and Xiangtai Meng. 2025. "Computational Investigation of Mechanism and Selectivity in (3+2) Cycloaddition Reactions Involving Azaoxyallyl Cations" Reactions 6, no. 4: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040070

APA StyleZhou, W., Zhang, L., Liu, G., Ma, X., & Meng, X. (2025). Computational Investigation of Mechanism and Selectivity in (3+2) Cycloaddition Reactions Involving Azaoxyallyl Cations. Reactions, 6(4), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040070