1. Introduction

There are more than 4000 varieties of potatoes in the world, but few are currently used. For example, in the United States, about 100 varieties of potatoes are regularly in use. According to data for 2020, 36 varieties of potatoes are included in the Register of Breeding Achievements of Kazakhstan. In the country’s agricultural enterprises, about 25 thousand hectares of irrigated land are allocated for potatoes, and the average potato yield is 35–37 tons/hectare. According to official data, the total gross harvest is about 4 million tons. Since the early 2000s, Kazakhstan’s potato growers have relied on modern, highly productive varieties of European selection. The share of imported varieties in farms exceeds 90%, and seed material is imported in significant quantities annually from Germany and the Netherlands. This is a serious problem for increasing domestic potato production.

One of the key strategic tasks is to achieve a significant increase in the volume of seed potatoes produced in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan has a number of advantages for the development of potato seed production, including a large territory and appropriate climate conditions.

In the last three years, the potato yield has grown significantly in Kazakhstan. The main condition for this is the usage of high-quality seeds of highly productive varieties. Currently, about 1200–1300 thousand hectares are under irrigation in the country. By 2027, the aim is to double these areas, which will provide conditions to increase the amount of land for the growth of potatoes.

Currently, in the Republic of Kazakhstan, all tasks and activities related to improving the conditions for selecting potatoes for sowing are relevant. The main areas of research are the following: selection for productivity, heat and drought resistance, resistance to diseases common in the republic, and the creation of varieties suitable for industrial processing [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The selection step requires describing the distinctive morphological features of a potato tuber, including its weight, size, and shape; this process is usually carried out manually, resulting in a labor productivity of about 600 tubers per hour. The requirements for seed potatoes are given in “GOST 33996-2016 Seed potatoes. Technical conditions and methods for determining quality” adopted by the Interstate Council for Standardization, Metrology and Certification [

5].

To improve the efficiency of potato and vegetable growing in Kazakhstan, one possible way to increase the accuracy and productivity of determining the parameters of potato tubers is the application of computer image processing, machine learning, and neural networks. Therefore, the development of a digital method to determine the morphological indicators of potato tubers using a machine vision system and proper algorithms and tools is relevant and timely.

To determine whether a batch of seed potatoes corresponds to a certain variety, it is necessary to determine the weight, size, shape, and color of each tuber in the selected sample. The potato variety is indicated in the accompanying documents. Therefore, breeders, seed farm specialists, and farmers face the problem of determining compliance, comparing the accompanying documents with the real indicators of potato tuber quality. Modern advances in computer image processing and artificial intelligence make it possible to solve this problem [

6,

7].

Objective quantitative methods for assessing the quality of vegetables and fruits, especially optical measurement methods together with deep learning approaches, provide high measurement accuracy and meet the requirements for various crop quality evaluations [

8,

9,

10]. The available networks using deep learning are accurate and robust. Pretrained networks differ from each other in their parameters and training settings, such as the size, algorithm, network weights, and biases, as well as the accuracy, performance, and speed, which influence the choice of a proper network for each specific task. From a review of the literature, the most popular pretrained models are SqueezeNet [

11], VGG [

9], ResNet, GoogLeNet [

12], YOLO Net [

6,

13], Inception, AlexNet, MobileNet [

7], DarkNet [

14], and EfficientNet [

15]. The development of these algorithms is limited by the scarcity of large, well-annotated datasets, especially when dealing with very specialized varieties.

In most studies dealing with the quality of vegetables, including potatoes, the use of computer vision techniques is the leading method. In recent years, authors have used RGB color images [

16], NIR images [

17], multispectral [

18], hyperspectral imaging, deep learning [

19,

20,

21,

22], multi-camera machine vision and morphological analysis [

23], texture [

24], and thermal and hyperspectral imaging [

25]; there are also systems to determine the presence of defects [

26], maturity assessments [

27], estimation of density and mass using ultrasound technology [

28], and acoustic evaluation [

12]. However, research on varietal identification using deep learning approaches is limited [

9].

Przybylak et al. (2020) [

13] applied neural image analysis for the automatic quality assessment of potato tubers. The developed system uses real-time potato images and classifies tubers with the presence of defects such as mechanical damage, spotting, sprouting, and putrefaction. The results of the experiments showed a classification accuracy of over 90%, as well as high stability to changes in shooting conditions and lighting. The proposed methodology has good perspectives for fast identification, but needs accuracy improvement.

Zhao et al. (2023) [

29] developed a non-destructive method for the detection of external defects of potato tubers based on hyperspectral imaging (HSI) combined with machine learning algorithms. The study used a hyperspectral imaging system in the 400–1000 nm range, which provides high-resolution spectral data. Based on the collected array of potato images with various types of defects, training samples were constructed, feature selection methods were used, and models based on SVM, RF, and other algorithms were trained. The classification accuracy of damaged tubers in their work reached 93.5%. Although these approaches show considerable potential, our aim is to develop the simplest and most economical method for potato identification, which constrains the feasibility of adopting this technique.

Azizi et al. (2021) [

30] applied machine learning methods, in particular artificial neural networks, to classify potato varieties based on morphological features. The authors used a custom-designed digital platform that extracts tuber characteristics, including shape, size, texture, and color, and generates a feature vector based on them. A multilayer neural network trained on a labeled dataset of images of different potato varieties was used to build the classification model. The system demonstrated recognition accuracy above 97% for most varieties, with the best results achieved using an architecture with two hidden layers.

Another study by Azizi (2016) [

31] dealt with the identification of ten Iranian potato varieties. It used data obtained from image processing together with principal component analysis, selecting 16 principal features, including color, shape, and texture parameters. The study concluded that the textural features had a key role in determining potato varieties from the tuber surface. The classification was performed using linear discriminant analysis and a non-linear artificial neural network method. Acceptable classification accuracy was obtained using a non-linear MLP neural network with a 16-20-10-10 structure in the study.

Compared to traditional machine learning approaches applied to images—such as SVM, RF, and related algorithms—deep learning offers several crucial advantages that guided the efforts in this research. Deep learning models extract features automatically, learn richer spatial information, scale with data, and typically achieve higher accuracy and robustness.

A review of ML models in potato plant phenotyping was conducted by Ciarán Miceal Johnson (2025) [

32]. The advantages of deep learning (DL) approaches and the rising trend of convolutional neural network (CNN)-based architectures were discussed. The author highlighted some key conclusions based on the large number of scientific papers reviewed, including the significant impact of pretraining dataset on the model’s performance; the fact that pretraining does not always lead to improved performance; when fine-tuning, it is not necessary to update the weights of the entire network; a common approach which works well is to adjust only the top layers using the target dataset, thus reducing the time needed for fine-tuning.

Su et al. (2018) [

33] presented an approach to automatic potato sorting based on machine vision and 3D shape analysis of tubers. The work implements a system that combines two-camera shooting and algorithms for reconstructing a 3D tuber model. The proposed system estimates length, width, volume, projection area, sphericity, and axis ratio. Using the extracted features, models for assessing the quality and sorting of potatoes based on classification rules defined by agricultural industry standards were proposed. The article pays special attention to the development of a method for the preliminary cleaning of noise from images, normalization of illumination, and correction of geometric distortions. The experiments conducted showed that the accuracy of sorting exceeded 94% using the standard calibration classes.

Wei et al. (2023) [

14] developed and implemented a cross-modal approach for non-destructive quality control of potatoes in a real production flow. Their work combines data from two modalities: visual images and spectral information. A key feature of the study is the use of data fusion technology, in which potato images from an RGB camera and reflectance spectra obtained using a spectrometer are fed into a common neural network architecture. Deep learning methods were used for the analysis, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transformer-based models, which allow the extraction of complex features of both visual and spectral nature. The results showed that the cross-modal approach outperforms traditional sorting methods in accuracy; an accuracy of over 95% was achieved in detecting defects of various natures, including mechanical damage, dents, and skin diseases. As authors [

14,

33] reported satisfactory accuracy using the described methods, accuracy levels could serve as a reference for comparison with the results from the present article

Although deep learning techniques have been successfully applied for potato disease detection, grading, and defect analysis, the varietal classification problem remains underexplored—especially for Kazakhstan-origin cultivars. The lack of open datasets and limited access to digital sorting technologies in Central Asia hinder the transition toward fully automated seed quality control. Therefore, the motivation of this study is to develop and experimentally validate a digital recognition approach tailored to the morphological and color features of local Kazakh potato varieties.

The present study aims to fill this gap by developing a method for the automatic recognition of different varieties of Kazakhstani potato tubers using an imaging system for acquiring color images and convolutional neural networks. The objects for the present study are mini and regular tubers of seed potatoes of promising varieties of Kazakhstan selection: Astana, Nerli, Zhanaisan, Edem, and Alians, as well as a machine learning algorithm and a program to determine the parameters of a tuber for a certain variety.

Varietal identification and digital classification are important for maintaining the purity of planting material, improving seed production, and reducing the share of imported potato varieties. Separating “mini” and standard tubers is also important for quality control in the early stages of cultivation and for selecting elite potato tubers.

The subject of this research is the implementation of a machine learning algorithm, the study of neural network options for determining potato varieties, and the testing of the program. The obtained research results will be used in the development of a digital automated system for determining quality indicators and sorting varietal seed potato tubers.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- 1.

Construction of a structured image dataset containing five key Kazakh potato varieties (regular and mini categories, 1500 images total).

- 2.

Implementation and comparison of two efficient CNN architectures—SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet—fine-tuned via transfer learning under MATLAB R2023b.

- 3.

Comprehensive evaluation of accuracy, precision, recall, and confusion matrices to assess model robustness and varietal separability.

- 4.

Quantitative analysis of model performance, computational complexity, and inference time, highlighting trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency.

- 5.

Provision of practical recommendations for integrating lightweight CNNs into real-world sorting lines and breeding laboratories.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Potato Dataset Description

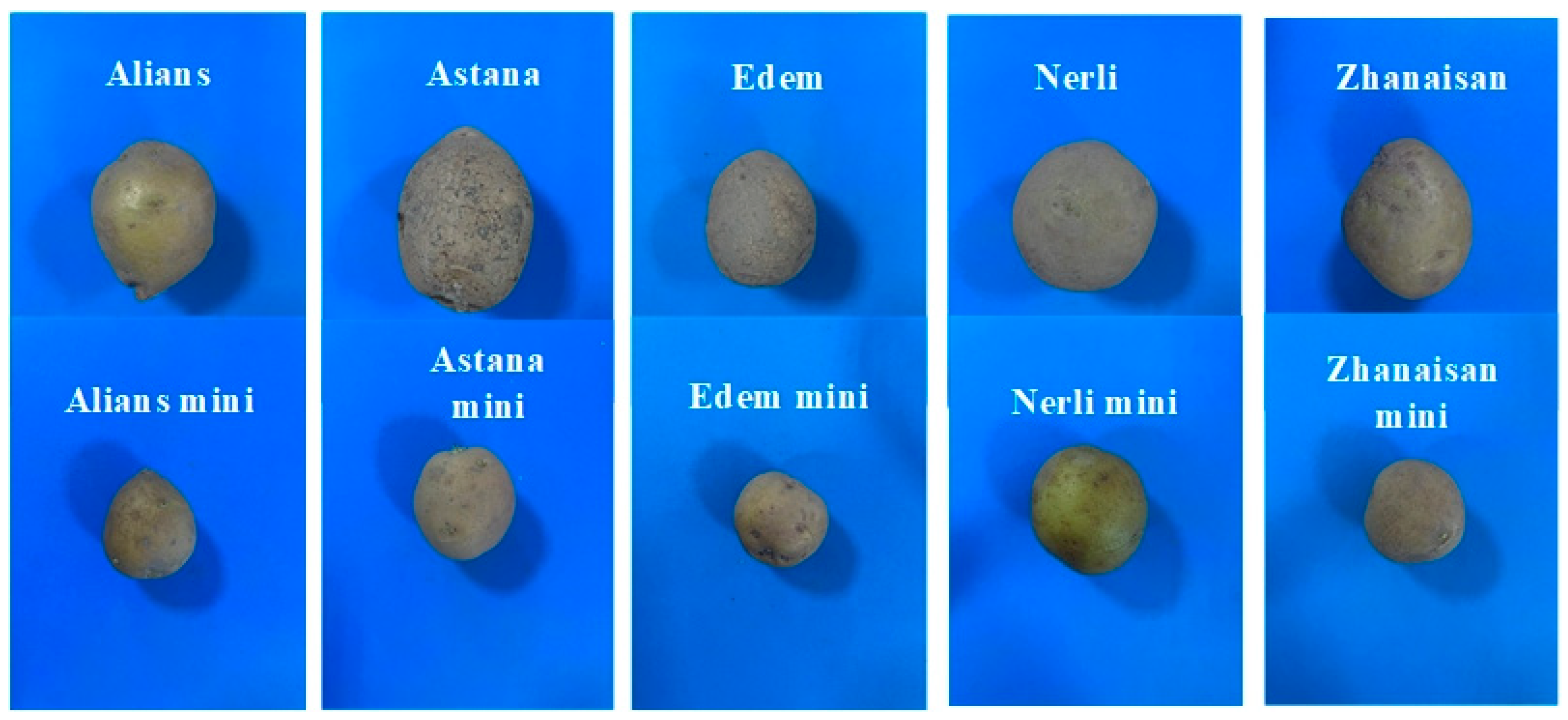

This study deals with five main varieties of Kazakh regular and mini tubers of seed potatoes: Astana, Nerli, Zhanaisan, Edem, and Alians. Sample images of potato tubers from the ten varieties are shown in

Figure 1.

These varieties were chosen as they represent the foundation of Kazakhstan’s seed potato breeding: Astana, Nerli, Zhanaisan, Edem, and Alians. They differ in morphological traits, climate adaptation, and yield.

- -

Astana is a high-yielding variety adapted to the climatic conditions of southeastern Kazakhstan and is heat- and drought-resistant.

- -

Zhanaisan is an early-ripening variety with high marketability. It is resistant to diseases and the climatic conditions of Kazakhstan.

- -

Edem is an early, high-yielding, and heat- and drought-resistant variety, with field resistance to diseases common in Kazakhstan.

- -

Alians is an early-ripening, promising, and universal variety for mechanical harvesting. It is resistant to diseases and the climatic conditions of Kazakhstan.

- -

Nerli is a selected variety with excellent taste qualities, a mid-season table potato variety.

These potato varieties were selected based on their significance and promise in recent years, as well as their recommendations from breeders and farmers.

The potato tubers were selected using stratified sampling to ensure representativeness and to capture all intravarietal variability. The selected varieties included typical tubers selected based on their skin color, size, weight, and shape. A total of five key Kazakh potato varieties—Astana, Nerli, Zhanaisan, Edem, and Alians—were selected for the study. For each variety, 100 tubers were analyzed, including 50 mini-tubers and 50 standard seed tubers, resulting in 500 total samples. Each tuber was photographed from three sides, yielding 1500 RGB images (960 × 1280 px).

Mini-tubers are the source material for propagating elite seed potatoes. They are grown in greenhouses from microclones and are characterized by a small tuber size (the largest transverse diameter is from 9 to 60 mm), even shape, and uniform skin. Standard tubers are subsequent generations (SSE/SE/E), intended for field propagation and subsequent planting. They are larger, with the largest transverse diameter measuring 28–60 mm, and have more pronounced eyes and natural surface defects. This separation is important when training neural networks, since the visual characteristics of mini-tubers differ significantly from standard seed tubers and require special adaptation of the model to the subtle morphological differences. The sizes of the largest transverse diameter of mini-tubers and standard seed tubers meet the requirements of the standard [

5].

Color images of each tuber were obtained in three projections, for a total of 1500 images. This number corresponds to the minimum sample size required to ensure statistical significance at a significance level of α = 0.95.

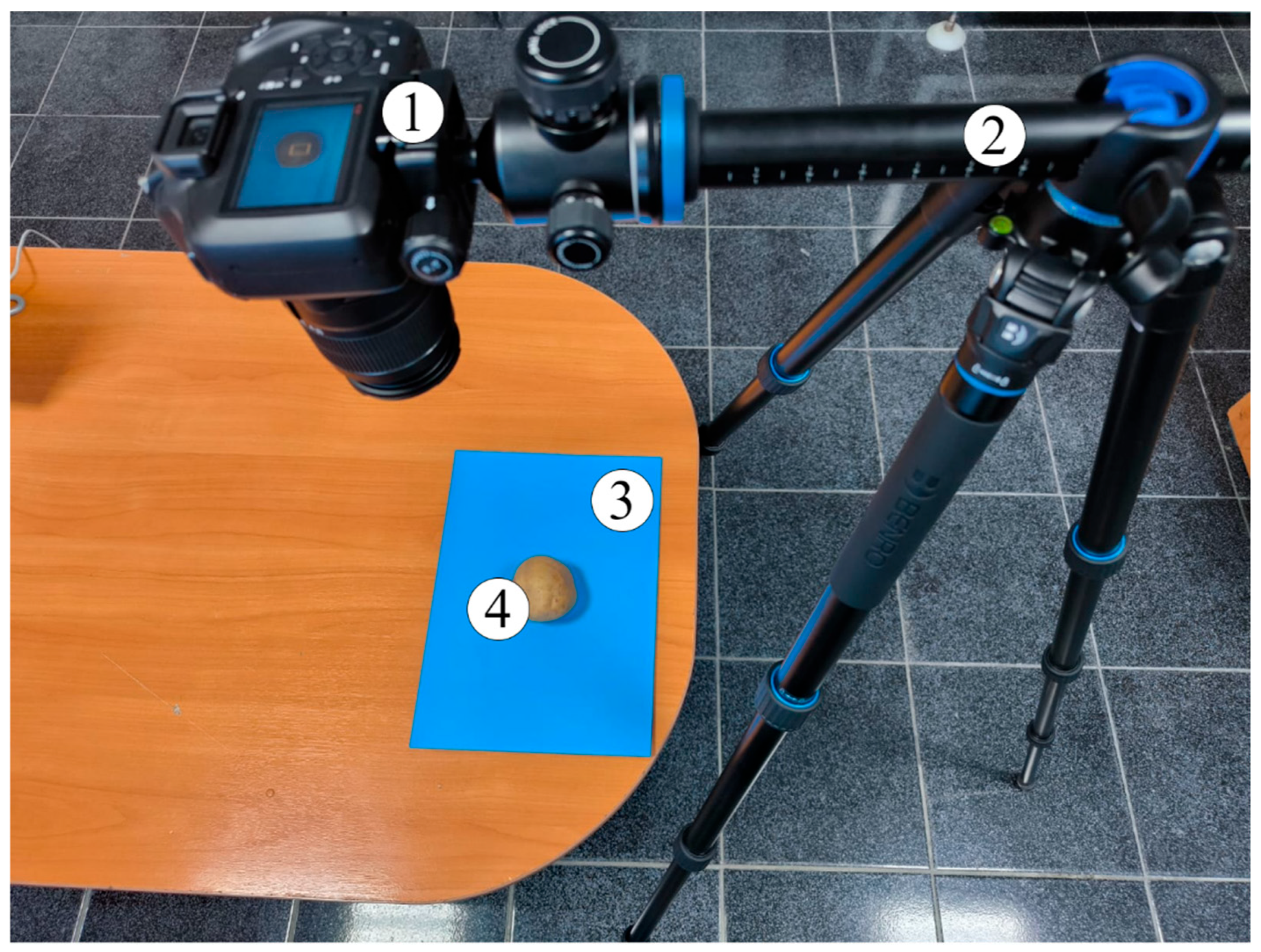

To obtain color images of the tubers with high quality, a stationary vertical imaging setup was used, as shown in

Figure 2.

The setup included a Canon EOS 4000D DSLR camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (1), a Benro SystemGo Plus horizontal arm tripod (Benro Image Technology Industrial Co., Ltd., Tanzhou Town, Zhongshan City, China) (2), and a flat blue matte background (3). This type of configuration is commonly used in machine vision systems for sorting various agricultural produce and the preparation of training samples for image analysis. The Canon EOS 4000D DSLR, equipped with an EF-S 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6 III lens, captured 18 megapixels of image quality using its APS-C CMOS sensor (22.3 × 14.9 mm). The camera was set to a focal length of 55 mm to reduce distortion and enhance detail.

The camera was fixed vertically above the subject using a horizontal tripod arm. Manual focus (MF) on the central area of the subject was set for shooting images. The exposure parameters were adjusted experimentally: shutter speed 1/60–1/125 s, and aperture f/8 for uniform depth of field.

White balance was set manually using a gray card or the daylight (5500 K) setting. All photos were saved in RAW format and duplicated as JPEGs for quick viewing. The Benro SystemGo Plus tripod allowed the camera to be securely fixed above the subject, ensuring the stability and repeatability of shooting conditions. The flexible and rotating tripod allowed for the accurate adjustment of the distance between the camera and the subject (approximately 50 cm). A built-in bubble level was used for leveling the horizon.

A plain blue A4 sheet of matte paper with an anti-glare finish served as the background. Blue was chosen as it is well-distinguishable from the color of the tubers, and there is no absence of overlap in the color spectrum, which facilitated the image segmentation step. A potato tuber was precisely centered within the shooting area. Each tuber was positioned in the same orientation, ensuring standardization of the images.

The stage was illuminated with diffused daylight, and two LED light sources with a color temperature of 5500 K and a color rendering index (CRI) above 90. The fixtures were situated symmetrically at a 45° angle to the subject, providing uniform illumination without shadows. This approach contributed to improved visual clarity of contours and increased accuracy of extracted features during digital processing.

Each tuber was captured sequentially, with a two-second shutter release delay to prevent blurring. All shot images were tagged with the date and sample number. Images were stored in a PC in separate folders corresponding to different varieties for subsequent analysis. Each potato tuber was captured three times from different viewing sides—two opposite sides and from above. Images (960 × 1280 pixels, RGB) were stored and processed in JPEG format. Sample images for the Alians variety are shown in

Figure 3.

To ensure independence between training and validation data, all images of a single tuber were grouped together and assigned exclusively to either the training or validation subset. The dataset was split in a 7:3 ratio (1050 training/450 validation images) using stratified sampling to preserve class balance. All images from a single tuber are assigned to the training or validation set as a whole (per tuber). During resizing to match CNN input dimensions (224 × 224 for GoogLeNet, 227 × 227 for SqueezeNet), the aspect ratio was preserved using MATLAB’s augmentedImageDatastore function to prevent geometric distortion.

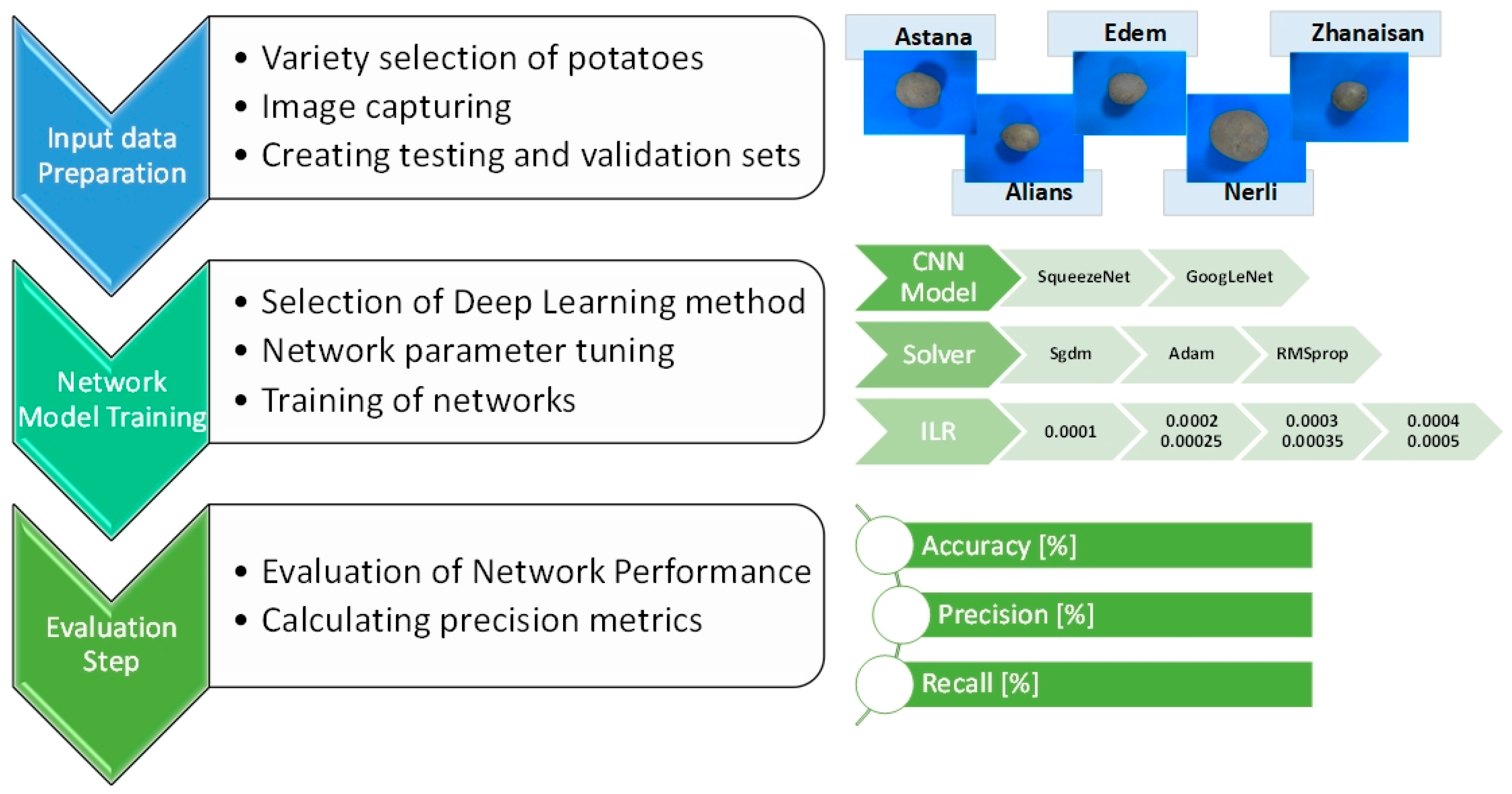

2.2. Algorithm for Varietal Identification via Digital Image Analysis and Explanation of the Methodology

The process of building a digital identification model involves three interrelated stages: creating an input database, training the model using deep learning approaches, and evaluating the model using new unseen test samples. This approach allows for a more objective assessment of potato varietal affiliation and the automation of the visual sorting process of planting material. The developed data processing algorithm is shown in

Figure 4.

The first stage involves collecting and pre-sorting potato tubers, capturing images by variety and type (mini-tubers and standard seed tubers), and creating training and validation sets. Each image was acquired under standard lighting and shooting conditions, with a resolution of 960 × 1280 pixels, and an RGB color model. Particular attention was paid to uniform shooting conditions and precise object centering in the frame, which significantly impacts the accuracy of subsequent classification. Images undergo initial manual tagging, during which each file is assigned a category corresponding to the potato variety. In this way, the initial training sample is formed, ensuring representativeness and complete coverage of intra- and inter-varietal variability.

The validation sets consisted of 30% (450 images) of the total image volume (1500 images).

The second stage involves choosing and training the deep learning models. Two pretrained convolutional neural networks, SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet, implemented in the MATLAB R2023b environment using the Deep Learning Toolbox package, were used to identify potato tuber varieties in our research.

SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet were chosen due to their proven effectiveness in solving problems of visual classification of agricultural objects, as well as high training speed and adaptability to transfer learning conditions.

The SqueezeNet network is a lightweight CNN. It is designed with substantially fewer parameters than other CNN architectures, but it attains similar performance accuracy. The required input image size for SqueezeNet is 227 × 227. SqueezeNet is designed for applications that require computational capability [

34]. In SqueezeNet, the model size is reduced through the following design alterations: 1 × 1 convolutions for parameter reduction, Fire modules (a combination of squeeze and expand layers) for efficient feature extraction, and a delayed down-sampling strategy to retain spatial information [

11]. Given that agricultural product classification must be both fast and accurate, SqueezeNet’s compact architecture ensures robust feature representations, low-latency inference, minimal computational overhead, and strong performance, making it suitable for real-time detection.

GoogLeNet is a deep convolutional neural network. It consists of 22 trainable layers and uses an innovative “Inception modules” architecture, which enables efficient feature extraction at different scale levels. This structure makes the model robust to variations in potato tuber shape, color, and texture [

18], boasting high-quality feature extraction and the ability to effectively classify visual objects even with a limited training sample size. GoogLeNet uses 1 input layer, 9 convolutional layers, 4 pooling layers, 2 normalization layers, 2 fully connected layers, and 1 softmax output layer responsible for the distribution of class membership probabilities. To adapt the model to the potato variety identification task, the final layers were fine-tuned. The fully connected layers were replaced with new ones with several outputs corresponding to the number of varieties being studied. The final softmax head and classification, necessary for training on the new dataset, were also recreated.

A computer system with an NVIDIA RTX 3070 graphics card (8 GB of VRAM), an Intel Core i7 processor, and 64 GB of RAM was used for training. The average model training time was approximately 15–20 min for the entire training cycle, including augmentation and validation.

Firstly, images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels for the GoogLeNet and 227 × 227 pixels for the SqueezeNet network. Next, the input data were normalized, the color channels were converted to the standard of the pretrained model, and structured training and validation subsamples were generated. A mandatory step is the implementation of dynamic image augmentation, including random rotations, horizontal reflections, scaling, and shifts aimed at expanding the volume of data without increasing the number of actual images. These measures allow us to increase the generalization ability of the model and its robustness to minor distortions of input images that occur in real production conditions. Scaling was performed while preserving object proportions and minimizing distortion using the augmentedImageDatastore function. This function not only automatically adjusted the image size but also applied dynamic augmentation, ensuring a high degree of model generalization.

To increase the variability of the training data and improve the model’s robustness to external factors (illumination, orientation, and background), the following augmentation scheme was used:

Random horizontal reflections;

Random image rotations from −10° to +10°;

Random scaling in the range from 95% to 105%;

Offsets along the X and Y axes up to 10 pixels;

Changes in image brightness, contrast, and saturation up to ±10%;

Addition of minimal Gaussian noise during the training phase.

This augmentation was performed directly during the training process without saving intermediate files, which avoided unnecessary load on the file system and accelerated model training.

2.3. Deep Learning Model Parameters and Training Settings for Identification

The selection of SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet was motivated by their proven efficiency and availability in the MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox, allowing baseline evaluation on mid-range GPUs. Both models achieve strong accuracy-to-complexity ratios—SqueezeNet (1.24 M parameters) and GoogLeNet (6.8 M parameters)—which makes them suitable for lightweight embedded applications.

| Model | Year | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (M) | Avg. Training Time/Epoch (s) | Inference Time/Image (ms, RTX 3070) |

| SqueezeNet | 2016 | 1.24 | 833 | 22 | 6.1 |

| GoogLeNet | 2014 | 6.8 | 1550 | 45 | 8.9 |

Nevertheless, we acknowledge that more recent architectures such as MobileNetV3 and EfficientNet-Lite outperform earlier CNNs in real-time contexts. These will be incorporated into future experiments to benchmark against the presented baseline results.

The model was trained using three different optimization algorithms: stochastic gradient descent with momentum (SGDM), the Adam algorithm, and Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSprop).

SGDM has proven to be robust and stable when working with small volumes of labeled agricultural data. It maintains a single learning rate (termed alpha) for all weight updates, and the learning rate does not change during training. A learning rate is maintained for each network weight (parameter) and separately adapted as learning unfolds.

Adam combines the advantages of two extensions of stochastic gradient descent. Specifically, the Adaptive Gradient Algorithm (AdaGrad) maintains a per-parameter learning rate that improves performance on problems with sparse gradients (computer vision problems). Adam adapts the parameter learning rates based on the average of the second moments of the gradients (the uncentered variance).

Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSProp) also maintains per-parameter learning rates that are adapted based on the average of recent magnitudes of the gradients for the weight. RMSProp adapts the parameter learning rates based on the average first moment.

Other hyperparameters for training the convolutional neural networks (CNNs), used in this study, are the initial learning rate and the learning rate drop factor.

The initial learning rate (ILR) hyperparameter controls how much a neural network’s weights improve during training. In the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimization algorithm, the learning rate determines the step size used to update the weights based on the loss gradient. A larger learning rate causes bigger weight adjustments, which can accelerate training but also increase the risk of skipping over the optimal solution. Conversely, a smaller learning rate results in smaller, more careful updates, improving stability but requiring more training steps to reach convergence. Overall, this parameter defines the trade-off between training speed and model reliability. Choosing an appropriate learning rate is critical. Developers often use grid or random search techniques to experimentally study the proper learning rates. Values such as 0.001 for Adam or 0.01 for SGD are often used in practice as default points. An imbalanced learning rate can lead to underfitting or unstable training with convolutional networks in image classification tasks. Adam, as a prepresentative adaptive optimizer, dynamically modifies the effective learning rates per parameter, relieving manual tuning but not completely excluding the need for initial rate selection.

The learning rate drop factor is a hyperparameter used in deep learning to gradually reduce the learning rate during model training, typically by multiplying the current learning rate by this factor at specified intervals (after a certain number of epochs). This approach helps the model to make large updates early on and then finer, more accurate adjustments as it approaches the optimal solution, preventing overshooting and improving convergence.

This study includes initial learning rates (ILRs) of 0.0001, 0.0002, 0.00025, 0.0003, 0.00035, 0.0004, and 0.0005. The learning rate drop factor was set to 0.1. Training of models included thirty epochs; the preferred number was set experimentally.

The training process was monitored using the built-in Experiment Manager tool, which displays the following in real time: loss and accuracy curves; overfitting dynamics; model convergence rate; and classification error distribution.

Finally, at the evaluation step, model validation was performed on a holdout subsample comprising 30% of the total image database. The proportion of data used for validation was chosen to ensure a balance between training and quality control of the classification. All training and validation subsamples were randomly generated, maintaining class proportions (stratified sampling).

The Matlab Experiment Manager tool does not have cross-validation built in by default; therefore, in this study, the recommended standard methodology, which splits the data into training and validation sets without k-fold cross-validation, was used.

After training was completed, a confusion matrix was constructed, allowing us to analyze which potato varieties were most susceptible to misclassification and at what stages the discrepancy between predicted and true labels occurred. Precision and recall metrics were also calculated for each class.

The results showed that the proposed model is adequate for successfully identifying potato tubers by variety, providing a high level of accuracy, resistance to augmented distorted images, and applicability to automated digital sorting tasks.

2.4. Model Evaluation Metrics

The quality of the trained digital identification model for potato tubers was evaluated using basic classification metrics based on confusion matrices. These evaluation metrics allow the comprehensive characterization of the model’s classification ability. Accuracy, recall, precision, and F1 score were estimated by the subsequent formulas:

where TP is the number of true positive predictions, FP is the number of false positive predictions, FN is the number of false negative predictions, and TN is the number of true negative predictions.

This methodology for sorting potato tubers based on their visual characteristics and machine vision introduces opportunities for integrating this technology into agricultural digitalization systems.

3. Results

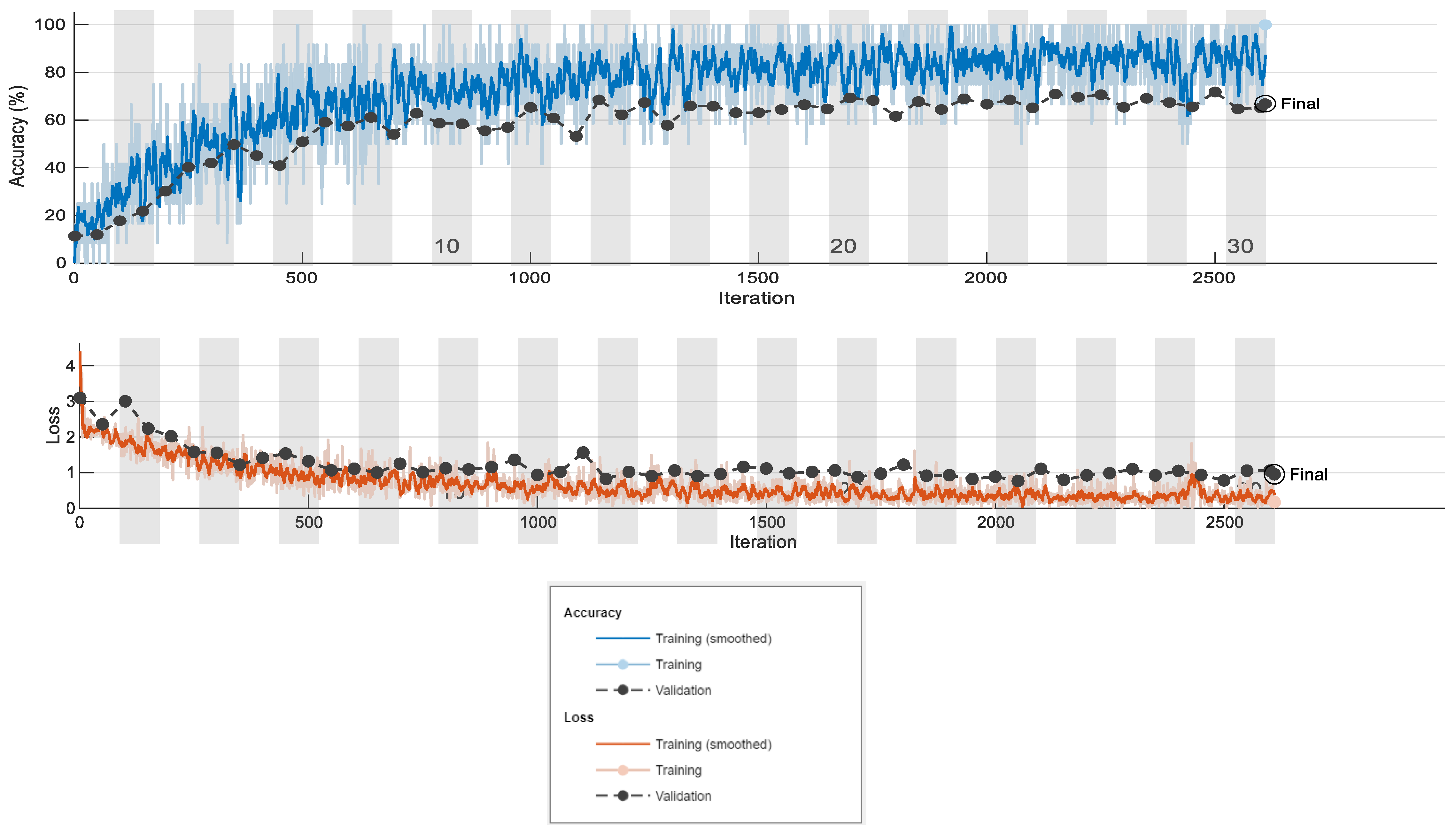

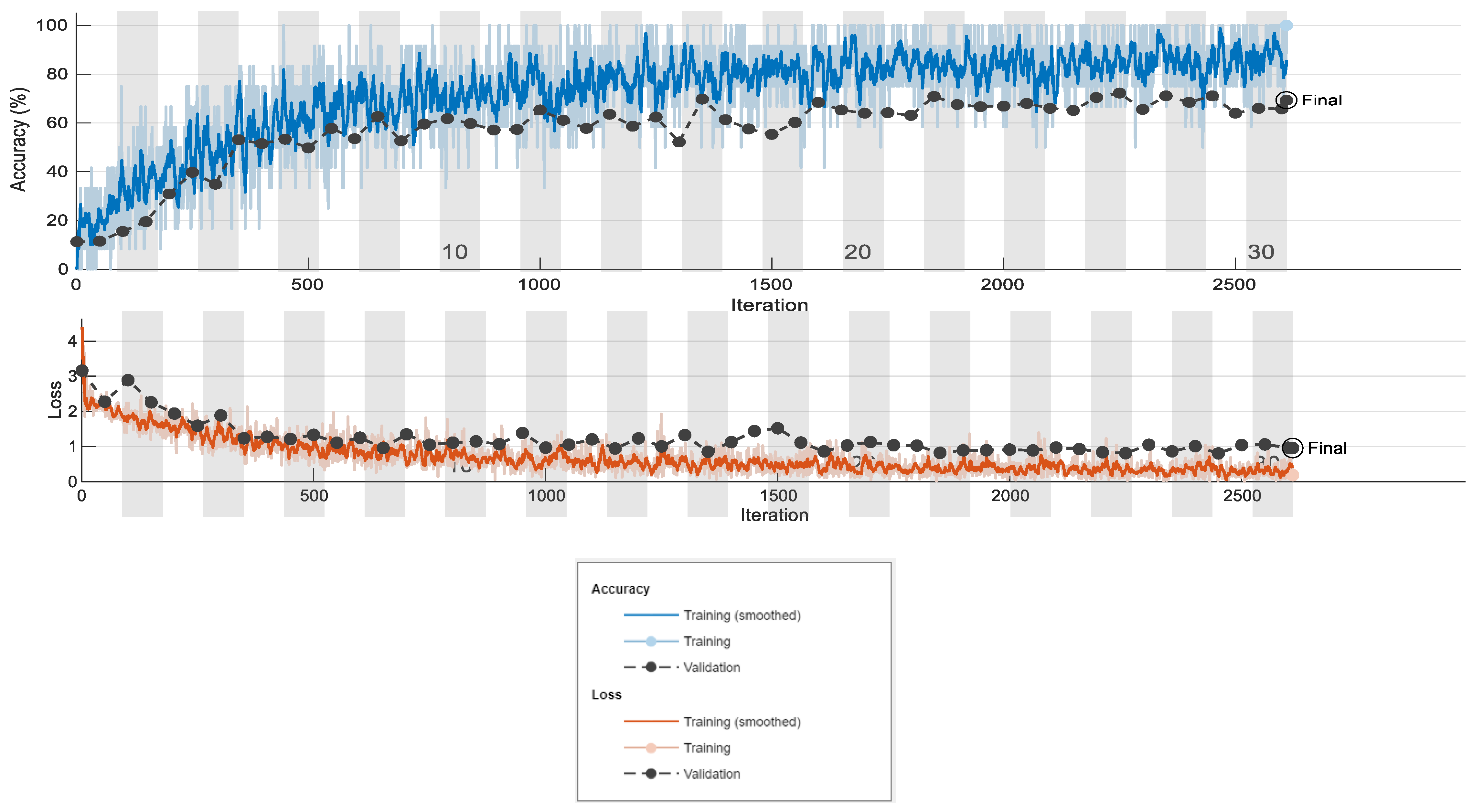

The two pretrained CNN networks, SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet, were precisely tuned. Models with different values of the initial learning rate (ILR) parameter were examined. The ILR was set with the following values: 0.0001, 0.0002, 0.00025, 0.0003, 0.00035, 0.0004, and 0.0005. The training of the networks was performed for 2500 iterations and 30 epochs for each network model. The training plots, including the training accuracy and training loss graphs for SqueezeNet with solver Sgdm, are shown in

Figure 5. The model refers to an initial learning rate of 0.0001.

The training graphs, including the training accuracy and training loss graphs for GoogLeNet at an initial learning rate of 0.0001 with the Sgdm solver, are shown in

Figure 6. It is obvious that after the 1400th iteration, the training accuracy for both networks maintains values around 60–70%, and the graphs have steady similarity. From the obtained outcomes, it can be said that after the 15th epoch, the accuracy and loss have similar values. The numbers of 30 training epochs and 2500 iterations are satisfactory to train the networks to identify the ten potato varieties.

The model’s performance was assessed by computing the values of the training accuracy (TA, %), training loss (TL, dimensionless), validation accuracy (VA, %), and validation loss (VL).

First, the values for the training accuracy, training loss, validation accuracy, and validation loss when training and validating the SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet networks using the three solver algorithms: Sgdm, Adam, and RMSprop are reported. The statistical values of the parameters, including average values, minimum, and maximum, were calculated and are shown in

Table 1.

The values of the TA vary widely between 50% and 100%, with those for the TL between 0.176 and 0.9584. The values for the VA are between 58% and 70.22%, and for the VL, they are between 0.7999 and 1.2417. In general, the values of the training quality indicators are not completely satisfactory, but several main conclusions can be drawn. The results show that SqueezeNet is lightly sensitive to solver type, while for GoogLeNet, the choice of solver is not significant.

For SqueezeNet, the TA and TL parameters have very close values for all three solvers, while the validation accuracy varies between 58% and 70.22%, with validation losses of 0.7999–1.2417. The best in terms of validation accuracy is the SqueezeNet network with RMSprop at 70.22%, but the TA value is 50–83.3%.

For GoogLeNet all of the evaluation metrics, TA, TL, VA, and VL, have the same values using Sgdm, Adam, and RMSprop. The training accuracy reaches 100%, but the validation accuracy does not exceed 69.33%, with VL losses up to 1.1974; therefore, it ranks second in validation accuracy after SqueezeNet with RMSprop.

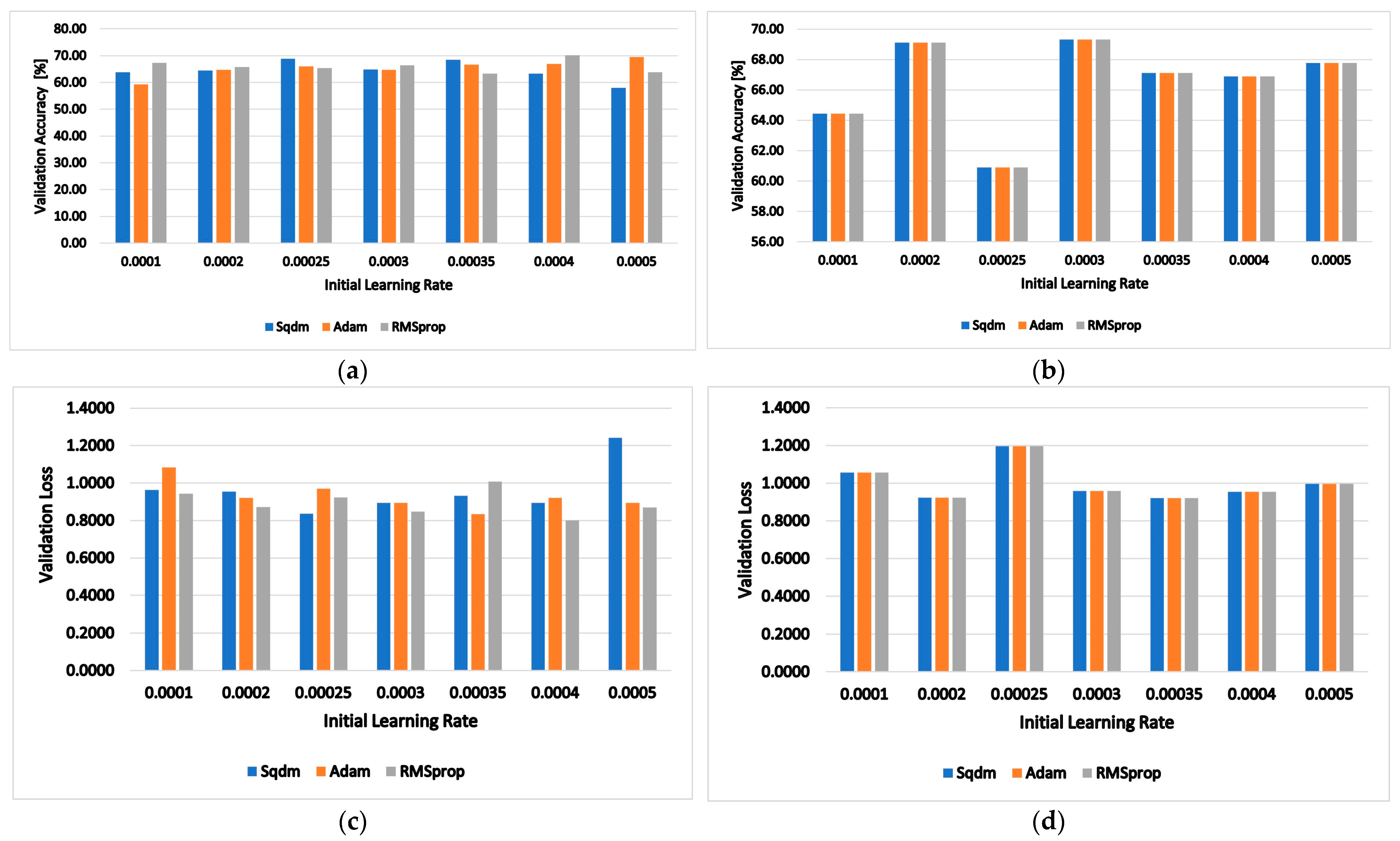

Next, the influence of the ILR value on the validation accuracy in % and the validation loss was examined.

Figure 7 shows the validation accuracy (a) and validation loss (c) values for SqueezeNet and the validation accuracy (b) and validation loss (d) values for GoogLeNet at different initial learning rates. The results show that the initial learning rate does not significantly influence the validation accuracy for SqueezeNet. It only affects the validation loss at an ILR of 0.005.

For the GoogLeNet network, the choice of the ILR parameter is important; the value 0.00025 is not suitable, since the validation accuracy drops to 61%, and the losses increase to 1.2. The best results are obtained for an ILR of 0.0003, with the highest validation accuracy and the lowest validation loss. From the graphical results, it can be concluded that, on average, the best network is SqueezeNet with the RMSprop solver and ILR = 0.0004.

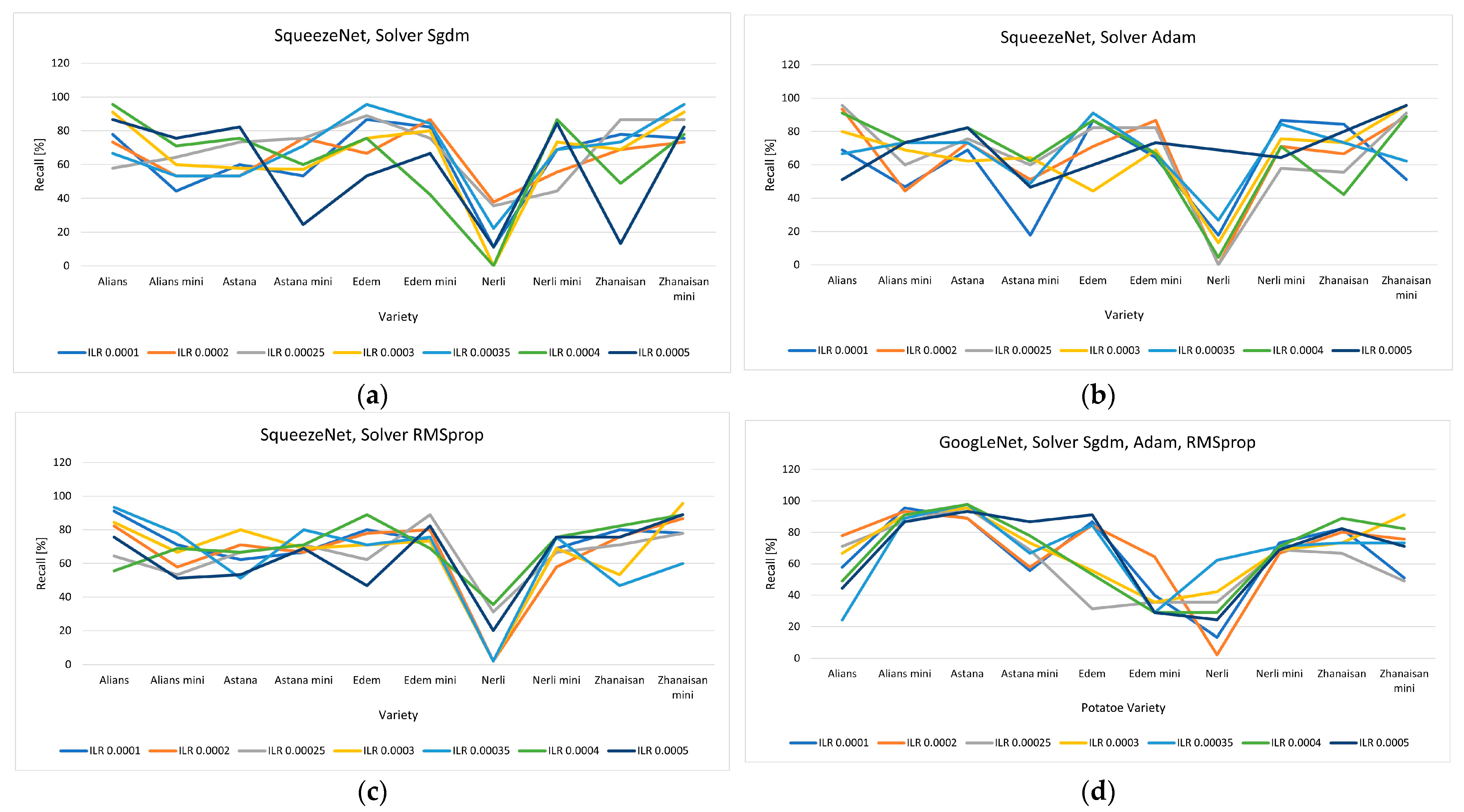

The influence of the recognition model on the recall was also examined with respect to the varietal identity.

Figure 8 shows the dependencies between the recall indicator and the network type, solver algorithm, and ILR for all varieties. The overall results show the Nerli regular variety as the least recognized. The recall values for Nerli do not exceed 42.2% for most models. For the Nerli variety, only the GoogLeNet network (

Figure 8d) with ILR 0.00035 showed better recognition, with a recall of about 68.9%.

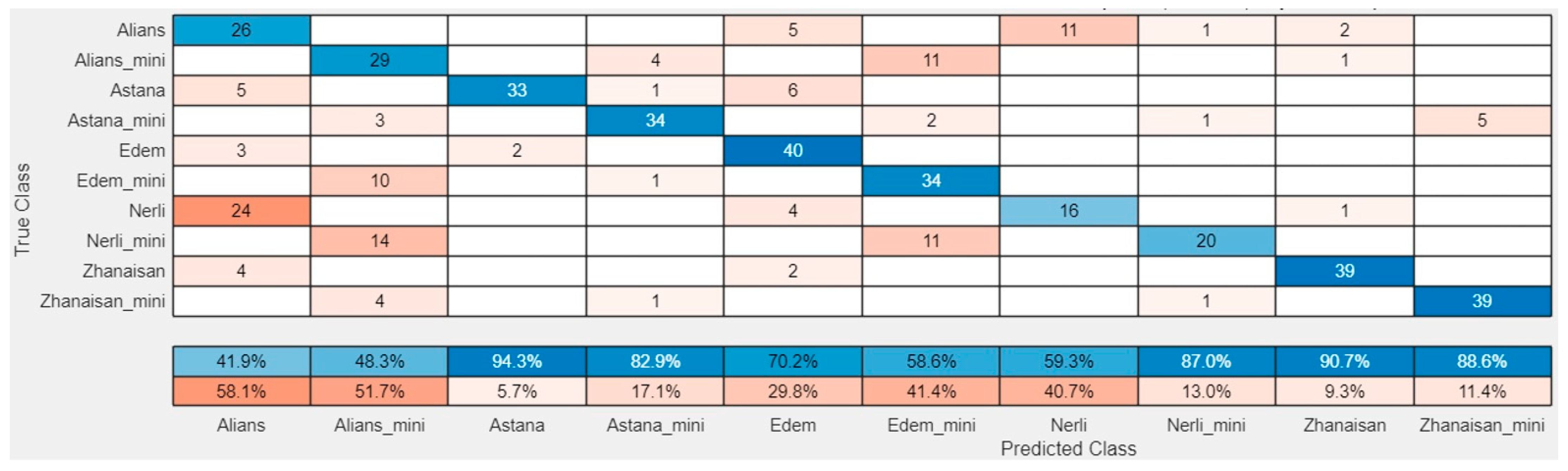

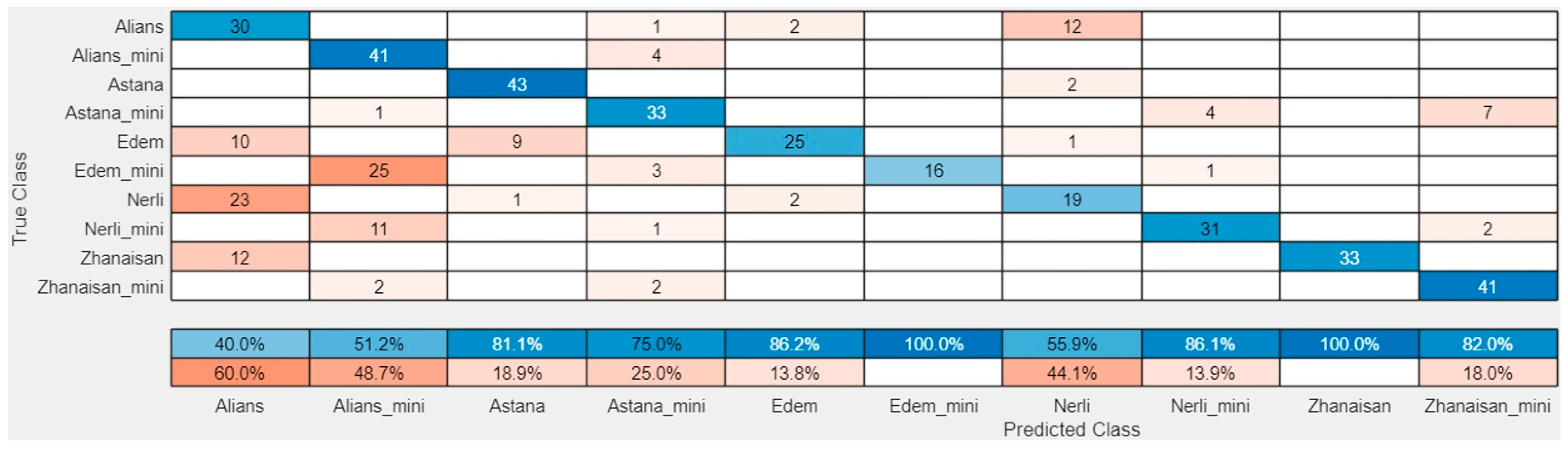

Confusion matrices were constructed for the validation sample (30% of the total image volume). These allow for a visual assessment of the distribution of correct and incorrect classifications across classes. The diagonal of the matrix displays the number of correctly identified varieties, while cases of misidentification are recorded off-diagonally.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the confusion matrices for two of the networks that achieved good accuracy indicators. As follows,

Figure 9 shows the SqueezeNet network using solver Sgdm and ILR = 0.00025 (

Figure 9), and

Figure 10 shows the GoogLeNet network with the Sgdm optimization algorithm and ILR = 0.0003 (

Figure 10).

An analysis of the confusion matrix revealed that the majority of errors occurred between varieties with similar tuber shape or color. Such cases require further sample expansion and refinement of the augmentation steps. The analysis of the given confusion matrices shows that, when using the SqueezeNet, the Nerli variety is the most difficult to identify, and the most incorrectly predicted samples are those attributed to the Alians variety. When using GoogLeNet, in addition to the Nerli variety, which maintains the same trend as the SqueezeNet, a second variety with a high degree of unrecognizability emerges—Edem mini. Edem mini is most often identified as Alians mini. The two varieties, Alians and Alians mini, are the ones that contain common characteristics for many of the varieties. Depending on the type of network and its settings, the samples are misidentified as belonging to these two varieties with small differences. When using the GoogLeNet network, 60% and 48.7% of the misidentified samples (actually belonging to one of the other eight varieties) are recognized as the Alians variety and the Alians mini variety, respectively, and when using the SqueezeNet, the values are 58.1% and 51.7%.

For varieties Edem mini and Zhanaisan, there are no false positive samples using GoogleNet.

There is no tendency to confuse regular potatoes of one variety with mini potatoes of the same variety. Most often, the potato is identified as belonging to a completely different variety.

The high metric values for accuracy, precision, and recall for varieties Astana and Zhanaisan confirm the model’s robustness and its ability to correctly process images of new, previously unseen potato tubers, but the other varieties did not achieve such high values. This means that for the varieties Alliance, Eden, and Nerli, further experimental tests with other networks are needed to achieve satisfactory identification accuracy.

An analysis of

Table 2 and the confusion matrix (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) revealed that SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet exhibited different sensitivities to visual varietal characteristics.

The most consistent results were obtained for the Astana and Zhanaisan varieties, where the recognition accuracy exceeded 97%. This is explained by their distinct morphological features—a smooth oval shape and uniform skin color.

Meanwhile, the Nerli variety and partially the Alians variety demonstrated the lowest accuracy (up to 85–90%) due to similar color shades and the uneven surface of the tubers.

The confusion matrix plots show that the majority of classification errors occur between the Alians–Edem and Nerli–Nerli mini varieties, confirming the need to increase the training set and use additional features (e.g., skin texture and microrelief).

4. Discussion

The results for the best given models as regards the accuracy of identifying the variety of potatoes with validation samples are summarized in

Table 3.

The comparative results confirm that both networks can successfully classify visually distinct potato varieties but exhibit different sensitivities to morphological variation. Astana and Zhanaisan achieved the highest metrics (>97% accuracy), attributed to their uniform oval shapes and smooth surface texture. In contrast, Nerli and Alians varieties demonstrated significant intra-class color variation and irregular contours, which led to misclassifications between standard and mini categories.

These results underline that network confusion arises primarily from texture and illumination variations rather than from structural shape alone. Data augmentation reduced, but did not fully eliminate, this issue.

Furthermore, SqueezeNet proved advantageous for computational efficiency, while GoogLeNet offered more stable convergence under limited data. The paired t-test comparing validation accuracies (p > 0.05) confirmed that performance differences between the two models were statistically insignificant at the 95% confidence level.

In summary, our results show strong potential for using only RGB images and classical deep learning models for identifying Kazakh potato varieties. As follows, two references are compared in terms of validation accuracy. The method presented in [

33] for automatic potato sorting uses machine vision and 3D shape analysis to estimate six tuber parameters. It includes several preprocessing steps—such as noise removal, illumination normalization, and geometric distortion correction—and achieves a sorting accuracy of about 94%. In contrast, our goal was to develop a methodology for varietal identification that requires minimal image preprocessing, thereby reducing the time needed for future online inspection without affecting identification accuracy.

The authors in [

14] previously reported a satisfactory 95% accuracy for potato sorting using a cross-modal approach that combined RGB images with spectral reflectance data to train and test convolutional neural networks. This performance is comparable to our results, as we obtained accuracy above 95.78% for six varieties (Astana, Astana mini, Edem, Nerli mini, and Zhanaisan) using only information from RGB images.

Despite promising results, the study has several limitations:

- -

The dataset was captured under controlled laboratory conditions with uniform lighting and background, which may not generalize to real sorting environments.

- -

The number of samples (50 per class) is relatively small, leading to potential overfitting.

- -

Only two classical CNN architectures were analyzed; inclusion of more recent lightweight models (MobileNetV3, EfficientNet-Lite) is planned.

- -

Real-time performance on embedded devices was not yet experimentally validated and will be addressed in future work.

5. Conclusions

The study demonstrates that both SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet architectures are capable of identifying Kazakh potato varieties with high accuracy under controlled conditions. The combination of SqueezeNet (RMSprop, ILR = 0.0004) and GoogLeNet (Sgdm, ILR = 0.0003) provides an optimal balance between recognition accuracy and computational efficiency.

The best results were achieved for Astana and Zhanaisan varieties (>97% accuracy), confirming the feasibility of lightweight CNNs for automated varietal identification. However, further dataset expansion, stronger augmentation, and integration of modern SOTA models are required for real-time industrial deployment.

Overall, this work provides a validated methodological baseline for the digital classification and quality assessment of seed potatoes in Kazakhstan and Central Asia.

SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet have proven to be well-suited models for agricultural classification tasks; therefore, these two networks were included in this study. They were retrained, and different network settings were tested.

When analyzing the results for the ten studied varieties, several varieties were identified for which high recognition accuracy was obtained (Astana, Zhanaisan, and Zhanaisan mini); those that are not identified very well (Alians, Alians mini, Astana mini, and Edem); and one variety that is poorly recognizable (Nerli).

Thus, the proposed digital identification algorithm and deep learning models, SqueezeNet and GoogLeNet, demonstrated potential efficiency in classifying potato tubers by variety. The possibility of practical application of this methodology in systems with sorting tasks, automated quality control, and digital monitoring of seed material is good.

The analysis concludes that the combination of SqueezeNet (RMSprop, ILR = 0.0004) and GoogLeNet (Sgdm, ILR = 0.0003) provides an optimal balance of accuracy and robustness in recognizing Kazakhstani potato varieties.

For the Astana and Zhanaisan varieties, accuracy rates exceeding 97% were achieved, making the models suitable for use in digital potato tuber sorting systems.

For the Nerli and Alians varieties, further network training on a larger sample, including a wider range of color variations, is recommended.

Overall, the proposed approach demonstrates the applicability of deep neural networks for creating digital characteristics for Kazakhstani varietal seed potato tubers and minitubers and for automating sorting processes.