1. Introduction

Wisconsin’s

$52.8 billion dairy industry supports over 120,700 jobs and nearly 45% of the state’s agricultural revenue [

1]. Each year, around 6 billion gallons of manure are applied to fields, often by custom operators. However, poor manure management has led to environmental issues, such as nitrate contamination and harmful algal blooms, resulting in over a billion dollars in mitigation costs. Cover crops, typically planted after corn harvests, coincide with manure application periods, creating scheduling and field management challenges. Applying manure before planting delays cover crop growth; while applying it afterward can smother young plants. Although manure injections could improve nutrient use, current methods are too invasive for newly established cover crops. An innovative solution is needed to align manure land application with cover cropping practices for sustainable agriculture. The integration of cover crops into agricultural systems has garnered significant attention due to their role in enhancing soil health, reducing erosion, and improving nutrient management [

2,

3]. Cover crops have been proposed as a potential solution to mitigate nitrogen losses by absorbing and temporarily immobilizing nitrogen through plant uptake [

4] and mineralization [

5]. However, applying liquid manure in cover crop systems presents challenges, particularly in balancing effective nutrient incorporation with minimal soil disturbance.

Traditional manure application methods often disrupt soil structure and diminish the benefits of cover crops, prompting the use of injection techniques that place liquid manure below the soil surface to reduce odors, nitrogen emissions, and nutrient losses by runoff [

6,

7,

8]. The design of injection tools, including chisels, knives, discs, and sweeps, strongly influences manure distribution and soil disturbance. Chisel injectors cut deep slots that channel manure downward, but they demand high energy and may lack sufficient holding capacity [

9,

10]. In contrast, disc injectors mix manure with surface soil through a rolling action, which compacts the soil and reduces infiltration [

11,

12,

13]. Sweep injectors, by contrast, distribute manure in wide horizontal bands at shallow depths, lifting the soil and allowing it to settle back over the manure [

14]. However, this pattern has been linked to higher nitrate levels compared to knife injectors, due to greater soil–manure contact, which enhances nitrogen mineralization [

15]. Soil bin studies have been widely used to evaluate manure application equipment, providing controlled conditions to isolate the effects of tool geometry and operating parameters. Nyord et al. [

16] optimized the slurry injector design through soil bin experiments, demonstrating that double discs at a 40 mm depth, combined with a tine at a 100 mm depth and a 40° rake angle, minimizing draft forces and crop damage, emphasizing the importance of precise component alignment [

16]. McLaughlin et al. [

17] also employed soil bins to compare draft requirements of single-disc, sweep, and chisel-sweep injectors, finding that soil condition and tool design strongly influenced energy demand, with sweep-based systems performing more efficiently than single-disc designs [

17]. Rahman et al. [

18] introduced a manure distribution index in soil bin testing of disc, furrower, and sweep injectors, showing that discs concentrated manure vertically. At the same time, furrowers achieved a lateral spread of up to 1.4 times their tool width, demonstrating higher efficiency relative to their size. Collectively, these soil bin studies reveal how injector depth, rake angle, travel speed, and cutting width govern draft force, soil disturbance, and manure placement [

19,

20], while also highlighting the resource-intensive nature of prototype-based testing.

The Discrete Element Method (DEM) is a computational modeling technique used to simulate the mechanical behavior of systems composed of many individual particles or discrete elements. In DEM, each particle is treated as an independent entity with its mass, position, and velocity, and interactions between particles are governed by contact mechanics that account for normal and tangential forces, including friction, damping, and sometimes cohesion. This method is particularly well-suited for analyzing granular materials, such as soils, powders, seeds, or aggregates, where particle-level interactions significantly influence bulk behavior. DEM has emerged as a powerful computational tool for analyzing soil-tool interactions in agricultural engineering. It enables modeling individual soil particles and their interactions with tool surfaces, allowing for visualization and quantification of dynamic soil displacement. DEM captures soil’s discontinuous and heterogeneous nature, making it suitable for evaluating liquid manure injection tools in varying soil conditions. DEM has been effectively used to simulate draft force, soil disturbance, and flow behavior, enabling rapid screening of multiple tool geometries under various soil conditions [

21,

22,

23]. These simulations reduce the need for extensive field trials and support performance-driven design decisions. Studies such as Sedara et al. [

24] have demonstrated that combining DEM with similitude principles can enhance prediction accuracy and identify efficient tool geometries for cohesive-frictional soils. Following DEM-based screening, soil bin experiments are critical for validating tool performance under controlled conditions. These tests enable the precise measurement of key parameters, such as draft force and above- and below-ground soil disturbance, with data collection supported by load cells, imaging systems, and standardized soil preparation methods [

20,

25]. Integrating simulation and experimental data has paved the way for systematic optimization strategies, often employing multi-objective frameworks to balance energy demand and minimal soil disruption. Combining DEM simulations, soil bin validation, and iterative optimization provides a powerful approach to developing next-generation manure injector tools.

This study focuses on developing an improved liquid manure injector tool that requires minimal draft force and causes minimal soil disturbance, maintaining soil structure and preserving cover crops. DEM offers a powerful computational approach for simulating soil-tool interactions, allowing for virtual testing and evaluation of various tool geometries, thereby reducing the time and cost associated with physical prototyping. The goal is to develop a liquid manure injector that minimizes draft force and soil disturbance.

The specific objectives of the research are to:

Develop a diverse set of liquid manure injector geometries incorporating variations in rake angle, thickness, and width to capture a broad design space.

Utilize Discrete Element Method (DEM) simulations to evaluate injector geometries for optimal soil–tool interaction.

Experimentally evaluate selected injector designs in a controlled soil bin to quantify draft force, above-ground soil disturbance, and below-ground rupture characteristics.

Apply multi-objective optimization techniques to identify the injector configuration that balances minimal energy demand with minimal surface disturbance and maximum subsoil manure placement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Liquid Manure Injector CAD Design

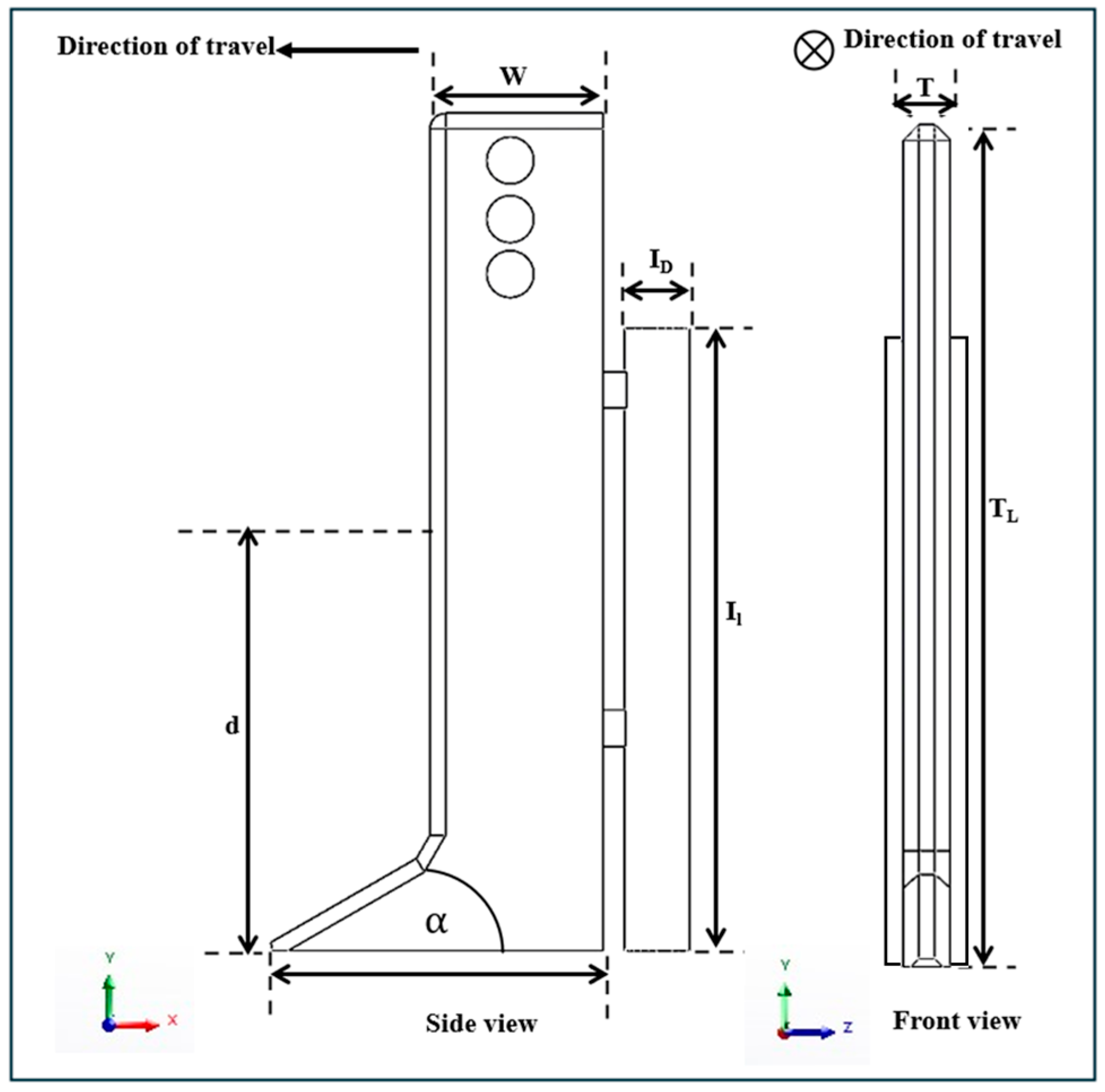

A comprehensive literature review was conducted on existing liquid manure injectors (shank-based) used in cover crop manure applications. Insights from this review informed the development of a new injector design, which focuses on minimizing draft force and soil disturbance. To systematically analyze different design configurations, 3D CAD models of eighteen liquid manure injectors were created using SolidWorks 2024. The injector designs incorporated variations in rake angle (30°, 45°, and 60°), tool thickness (25 and 30 mm), and tool width (102, 110, and 118 mm) (

Table 1). These geometric configurations were selected to assess their impact on injector performance. A schematic diagram of the modeled injectors is presented in

Figure 1. The design includes side and front views, with features like rake angle (α), tool width (W), tool thickness (T), tool total length (T_L), injection tube length (I_L), and injector tube diameter (I_D), providing a detailed understanding of the tool’s structural properties. The injector design (ID) tools were labeled ID_1–ID_18. The rake angle of a shank tool plays a critical role because it enables the soil to flow more smoothly over the tool surface, thereby decreasing resistance and making it easier to pull the tool through the soil [

26]. The tool width is related to side friction and soil compaction along the tool’s edges during soil engagement. Tool width also helps determine the size of the cross-sectional area of the soil that the tool engages. Tool thickness is related to structural strength, which affects the frontal surface area facing the direction of motion, thereby increasing soil-tool contact and friction.

2.2. DEM Screen Soil-to-Tool Simulation Setup

The DEM screening model was developed using soil mechanical parameters reported in the literature [

27,

28,

29,

30] for soils, which reliably capture soil rupture patterns and relative draft force trends in soil–tool interaction simulations in ALTAIR-EDEM (2024) software. Because many DEM input parameters, such as particle stiffness, friction, and cohesion, are material-property based and transferable across studies, their use from validated sources ensures consistency with accepted modeling practices [

31]. Thus, the DEM setup provides a reliable approach for screening injector designs, reducing experimental costs while maintaining confidence in comparative outcomes. A similar method was successfully applied by Sedara et al. [

24] for screening scaled shank designs.

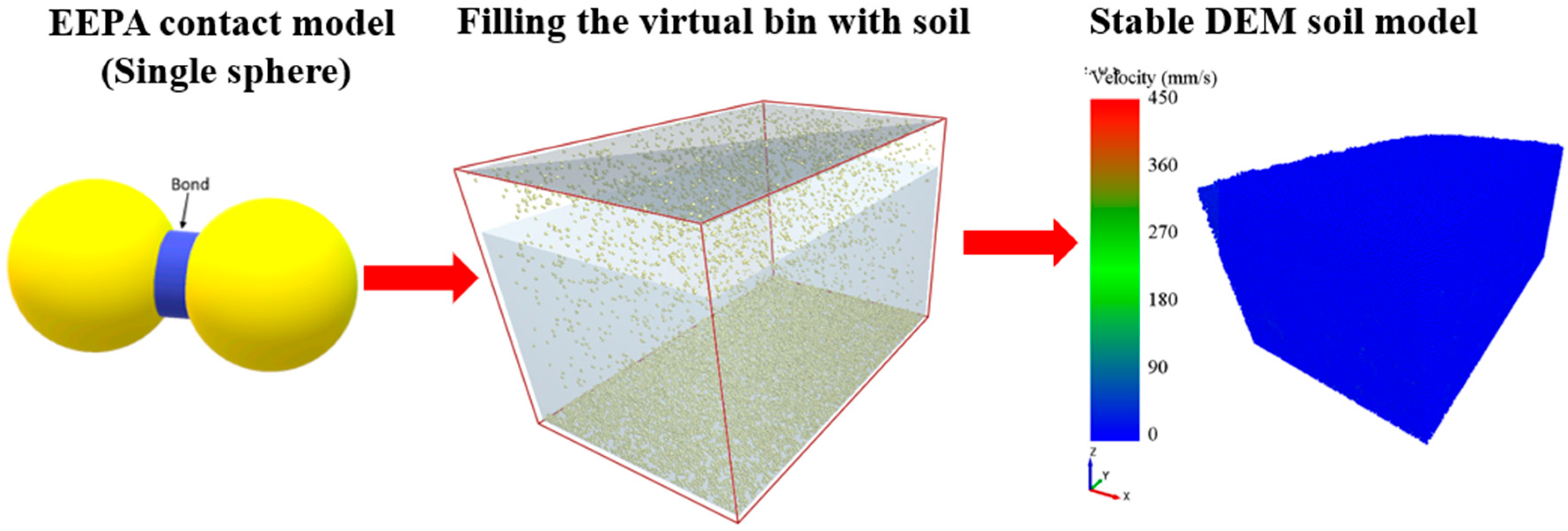

Figure 2 shows the development of a stable DEM soil model using the Edinburgh Elasto-Plastic Adhesive (EEPA) contact model. In this method, soil particles are modeled as bonded spheres that interact through elastic, plastic, and adhesive forces, capturing the cohesive behavior of real soil. A virtual soil bin (1140 × 1010 × 580 mm) is filled with spherical particles (Pd = 3 mm) using a controlled filling procedure, after which the soil settles under gravity until particle velocities stabilize. The blue region in the velocity map indicates that the particles have reached equilibrium, confirming a mechanically stable soil bed suitable for simulating soil–tool interactions and deformation behavior.

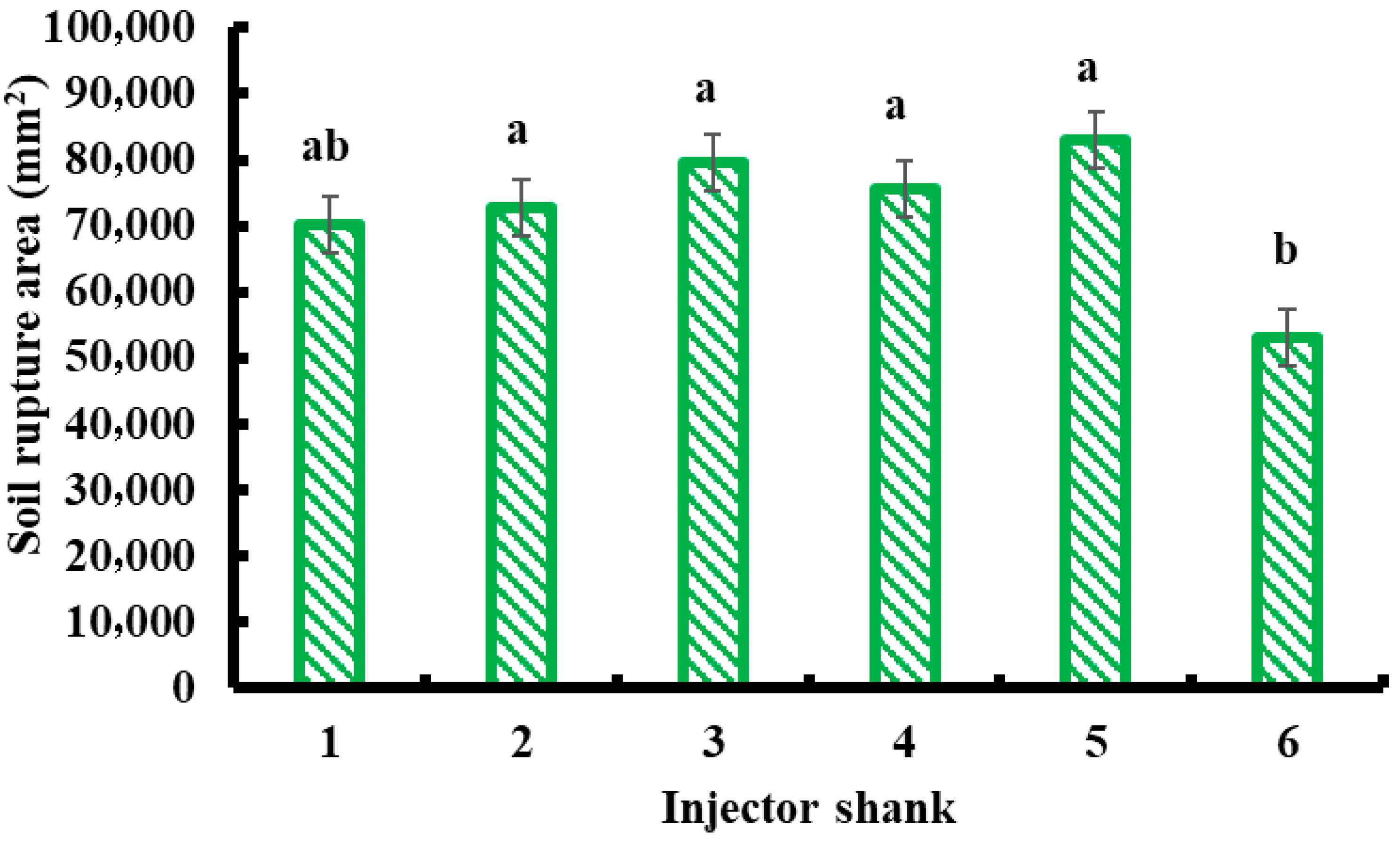

The DEM was employed to simulate soil-to-injector shank interactions, screening and evaluating the performance of eighteen initial shank designs, which ultimately yielded six design shanks for the subsequent soil bin experiment study. The screening focused on two key DEM-predicted parameters, draft force and soil rupture area, enabling comparison of design features based on performance efficiency. This DEM-based pre-screening approach aimed to significantly reduce the need for physical prototyping and experimental testing, which are often time-consuming and costly [

32]. The Edinburgh Elasto-Plastic Adhesive (EEPA) contact model in EDEM software [

33] was selected for the constitutive modeling of contact forces and displacements between particles and between soil and tool surfaces. The EEPA model captures elasto-plastic behavior during loading and unloading cycles, incorporating a stress-dependent cohesion mechanism, which makes it suitable for modeling the mechanical response of agricultural soils. For the DEM simulations, soil particles were represented as single spheres with a diameter of 3 mm. All relevant material and interaction properties (Poisson’s ratio, shear modulus, particle density, and frictional coefficients) were based on values reported in previous DEM soil-tool interaction studies [

34,

35].

Table 2 and

Table 3 summarize the parameters and simulation setup used for soil-to-soil and soil-to-geometry interactions, including coefficients of restitution, static friction, and rolling friction based on the Hertz-Mindlin contact law. The EEPA model’s parameters, such as surface energy, contact plasticity ratio, pull-off force, slope exponent, tensile exponent, and tangential stiffness multiplier, were also configured according to EDEM documentation [

33,

36].

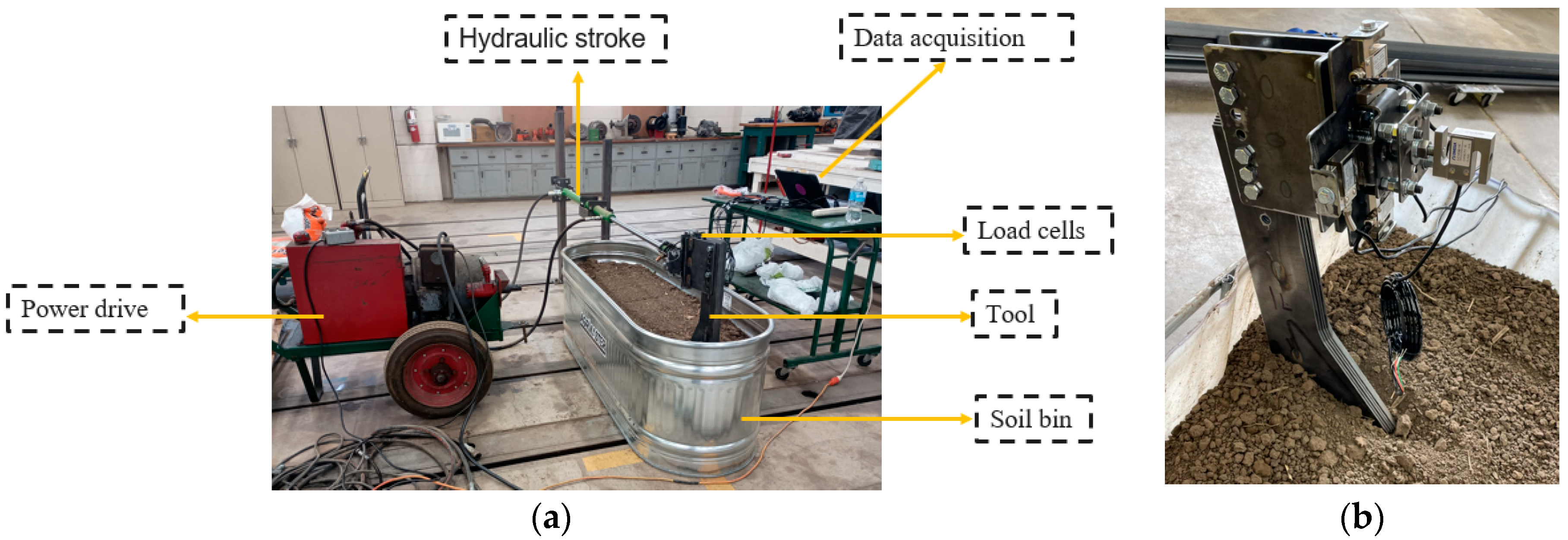

2.3. Soil Bin Design of Experiment

The soil bin used in this study measured 1140 mm in length, 1010 mm in width, and 580 mm in height (

Figure 3). The soil was filled to a consistent soil height of 460 mm, creating a controlled environment to evaluate the soil–tool interaction of different manure injector shank designs. A hydraulic actuation system drove the movement of the liquid manure tool through the soil. A 1220 mm stroke hydraulic cylinder, powered by a portable hydraulic power unit, provided the pulling force. A flow control valve regulated the hydraulic flow, allowing a consistent tool travel nominal speed of 440 mm/s. This speed was selected to simulate typical field conditions and was maintained uniformly across all trials. The operating depth of the tools was precisely maintained at 200 mm using an adjustable mounting system. The hydraulic cylinder mounts allowed vertical adjustment, and both the tools and mounting brackets were fabricated with 25.4 mm (1-inch) spaced holes, enabling fine depth control. These settings ensured consistent tool alignment and depth across all treatments.

The soil used in the experiment was sourced from the West Madison Agricultural Research Station in Verona of Wisconsin, USA (Bayer sandy loam (Coarse-loamy, mixed, semiactive, mesic Typic Hapludalfs)), consisting of 45% sand, 32% silt, and 16% clay, and allowed to air-dry for one week before use. After drying, large clumps and shafts were manually removed to ensure a uniform soil texture suitable for controlled testing. Between replications, the soil was reconditioned to ensure consistency across trials. Reconditioning involves using a pulverizer machine (Max LiIon Cultivator/Tiller, Black & Decker, New Britain, CT, USA) to loosen and break up the soil, thereby eliminating clumps. After loosening, the soil was leveled using a flat wooden plate to create a smooth and even surface. A 10 × 10-inch tamper (Yard Works, Charleston, SC, USA) was then used to achieve the desired bulk density of 1340 kg/m3 using the core sampling method, for each run (core volume = 252.88 cm3)), ensuring consistent soil compaction across the entire bin. This systematic approach helped standardize soil conditions for each trial, thereby improving the reliability and repeatability of the experimental results.

A completely randomized design (CRD) was employed, with six different shank designs evaluated across three replications. Each replication consisted of a separately prepared soil bed. The shank designs were randomly assigned to minimize bias due to potential soil variability. Therefore, the objective was to identify a shank configuration that delivers effective subsoil fracturing with minimal energy input and surface disturbance, aligning with conservation tillage and sustainable manure management practices.

2.4. Soil Draft Forces and Soil Disturbance Measurement

The soil bin experimental setup and measurement parameters used are presented in

Table 4, which outlines the instrumentation specifications, operating conditions, and data acquisition details employed to measure the draft forces acting on the liquid manure injector tools.

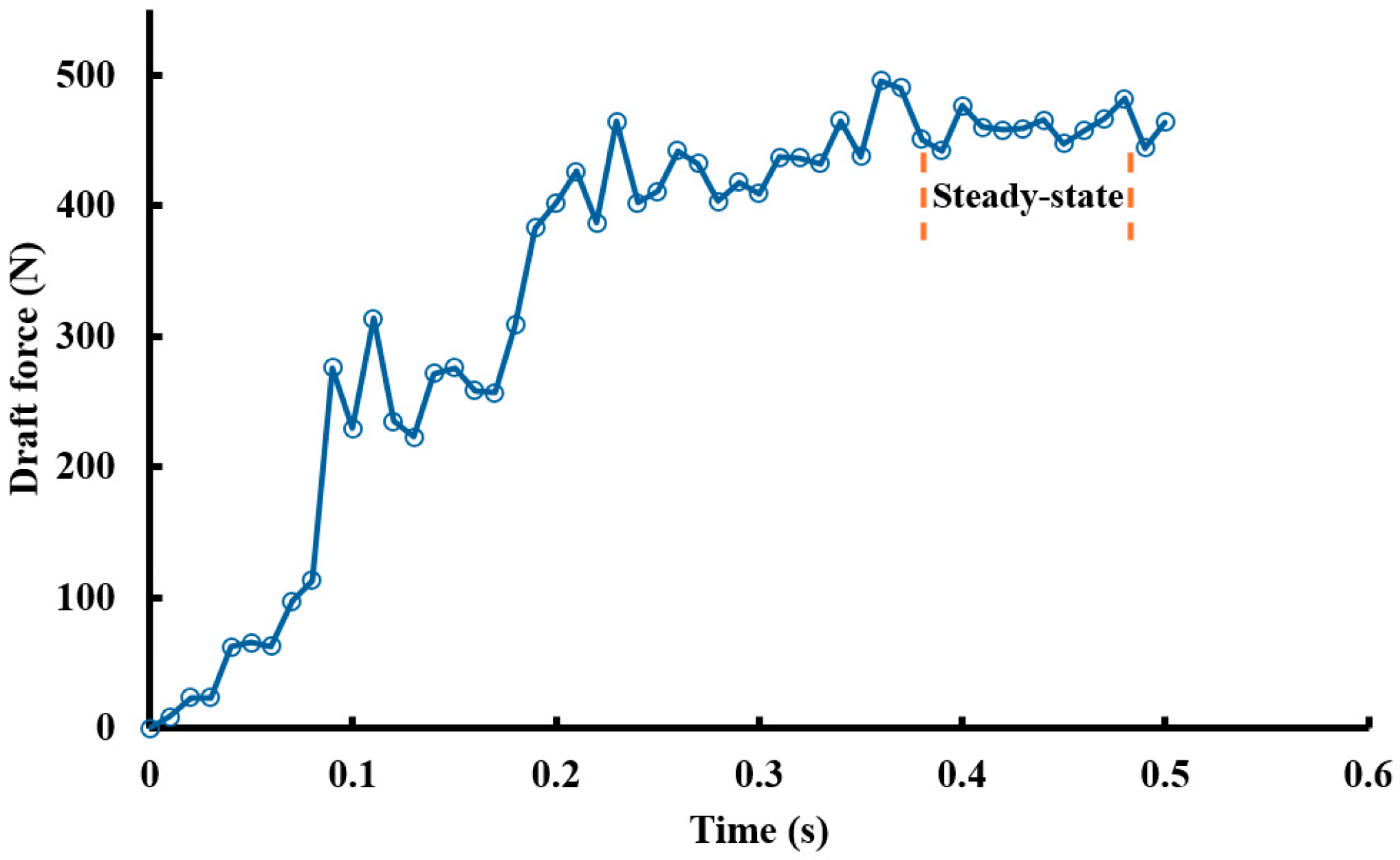

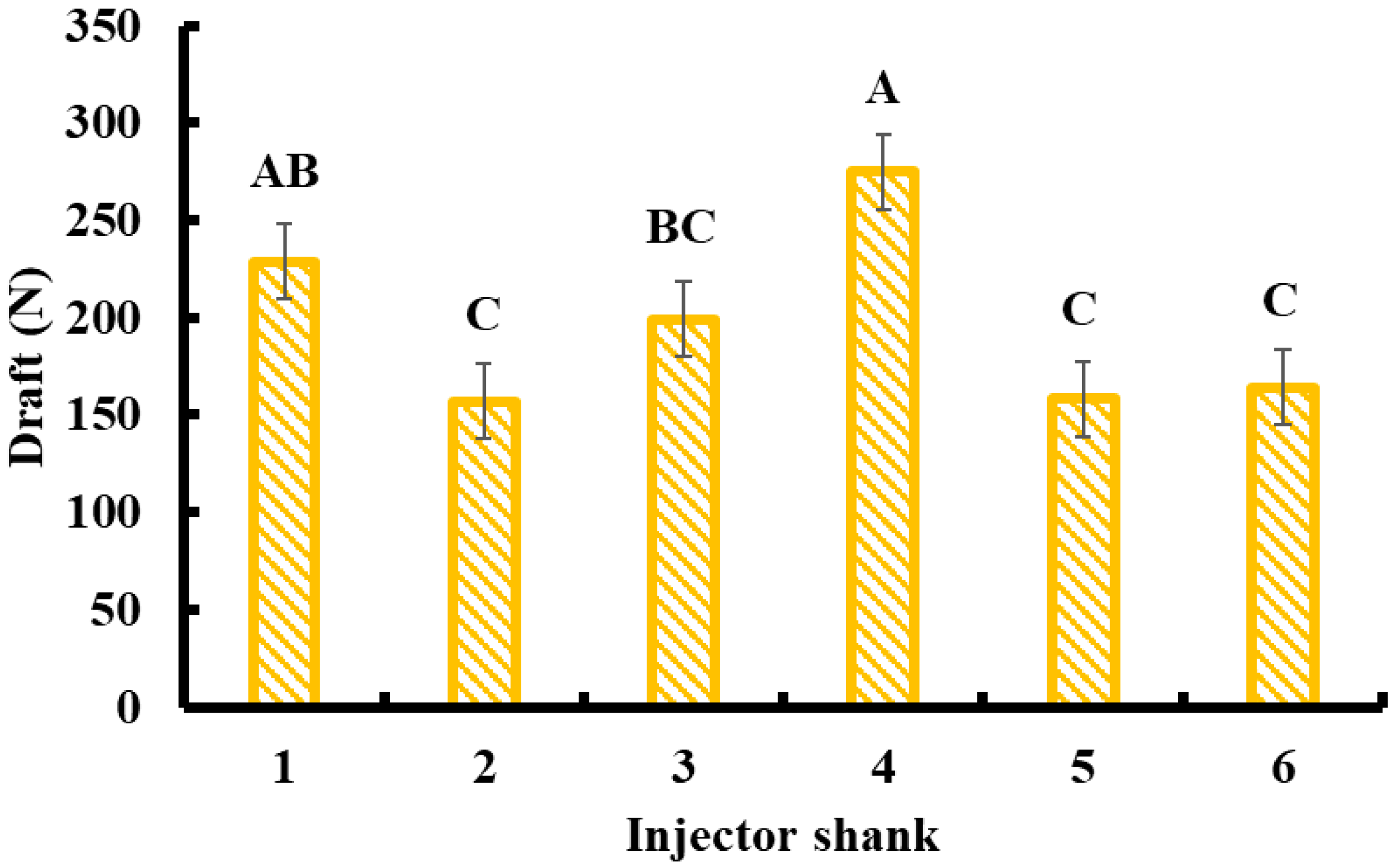

During the soil bin tests, the draft forces (horizontal forces, Fx) acting on the liquid manure tools were measured using CALT S-Type Load Cells DYLY-103l (rated capacity: 0–500 N, sensitivity: 2.0 mV/V; SHANGHAI QIYI Co., Ltd., Baoshan District, Shanghai, China). Draft force data were collected for six selected tool prototypes as they traveled along the soil bin. The data acquisition system used was the DEWSoft KRYPTON (resolution: 24-bit, bandwidth: 0.49 fs, voltage ranges: ±100 mV, ±10 mV; Dewesoft LLC, Whitehouse, OH, USA). Each tool traveled at a constant nominal speed of 440 mm/s and at a tool working depth of 200 mm. The load cells recorded force data at a sampling rate of 100 Hz.

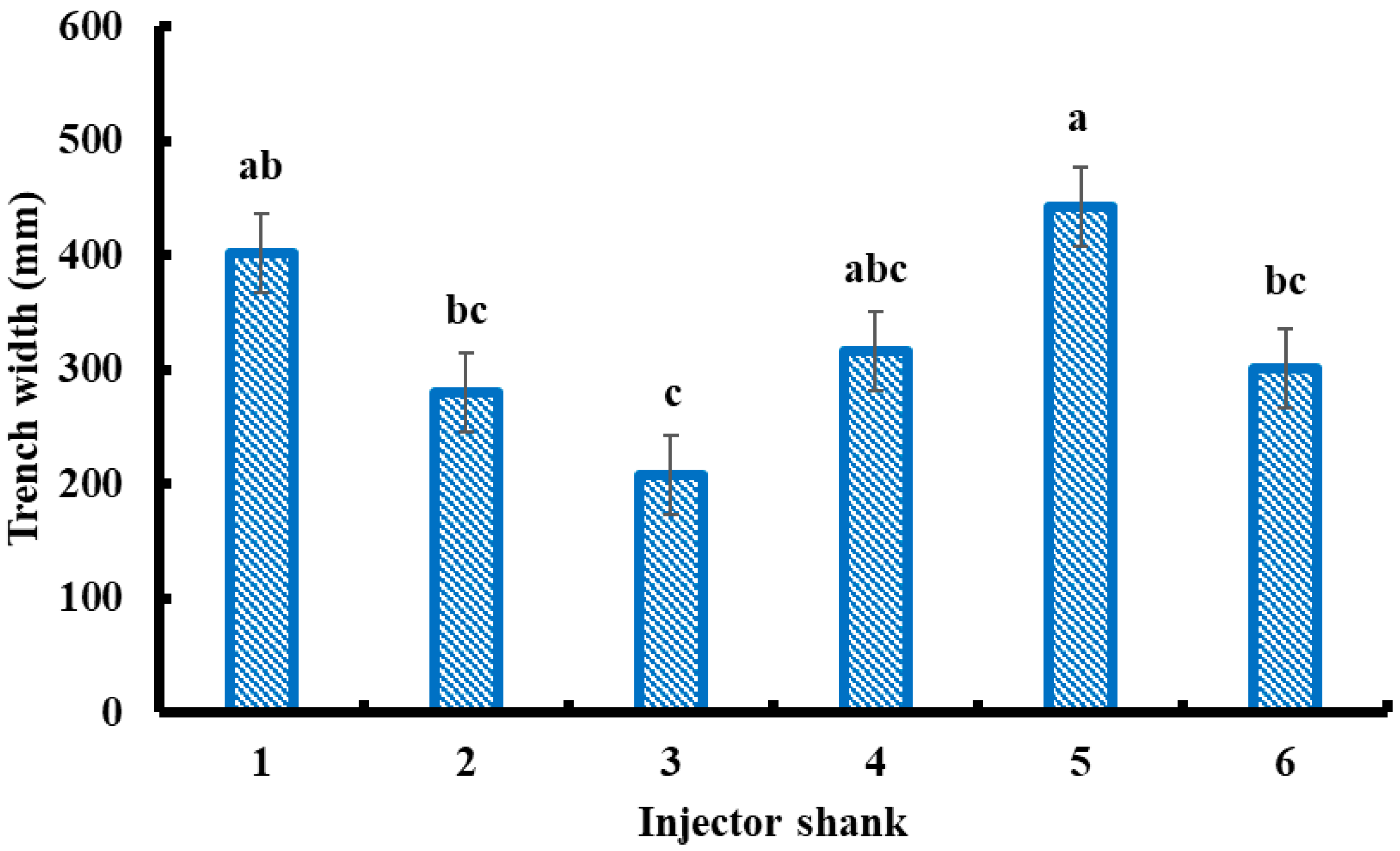

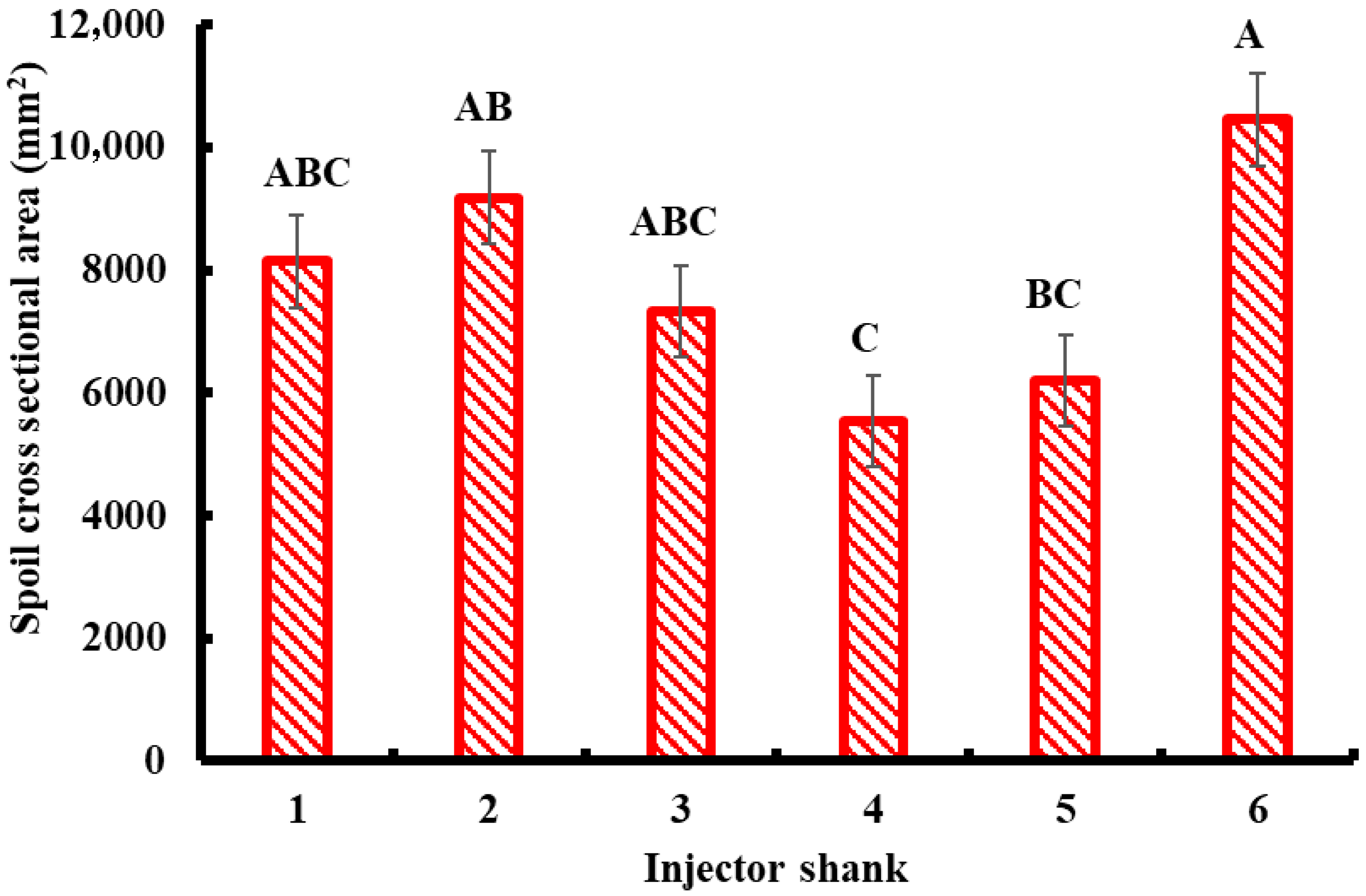

The liquid manure injector prototypes were also evaluated for their impact on both below-ground and above-ground soil disturbance. Above-ground disturbance was assessed by measuring trench width and spoil cross-sectional area (Equation (1)), while below-ground disturbance was quantified by determining the soil rupture area.

where

is Spoil cross-sectional area,

is mean ridge height, and

is trench width.

Trench width and ridge height (left and right) were measured using a Wixey Remote Planer Readout Device (Barry Wixey Development, Seattle, WA, USA; resolution: 0.1 mm) (

Figure 4b), with measurements referenced to the undisturbed soil surface after each test. The spoil cross-sectional area was calculated by multiplying the trench width by the vertical soil displacement (ridge height) (

Figure 4c). To measure below-ground soil disturbance, loosened soil in the affected regions was carefully removed by hand to expose the soil rupture area. Vertical distances (

y-axis) were measured using a Bosch GLM 50–27 CG Professional laser measurement device (Bosch, Gerlingen, Germany) (

Figure 4a). In contrast, lateral distances (

x-axis) were recorded using the Wixey Remote Planer Readout Device. Images of the exposed soil rupture areas were captured using a Canon G7X camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for image processing. The Canon G7 X, featuring a 25.4 mm sensor (13.2 × 8.8 mm) and a resolution of 5472 × 3648 pixels, has a pixel pitch of 2.41 µm. Its spatial resolution depends on the focal length and distance: at an 8.8 mm focal length, the resolution was 0.137 mm/pixel at 0.5 m, while at a 36.8 mm focal length, it improved to 0.0327 mm/pixel at the same distance. Thus, closer distances and longer focal lengths of 50 mm yield finer pixel resolution, making the setup adaptable to the resolution needs for soil rupture pictures, which were recorded at 30 frames per second (fps). Selected high-quality images were then analyzed using the open-source software ImageJ 1.54p [

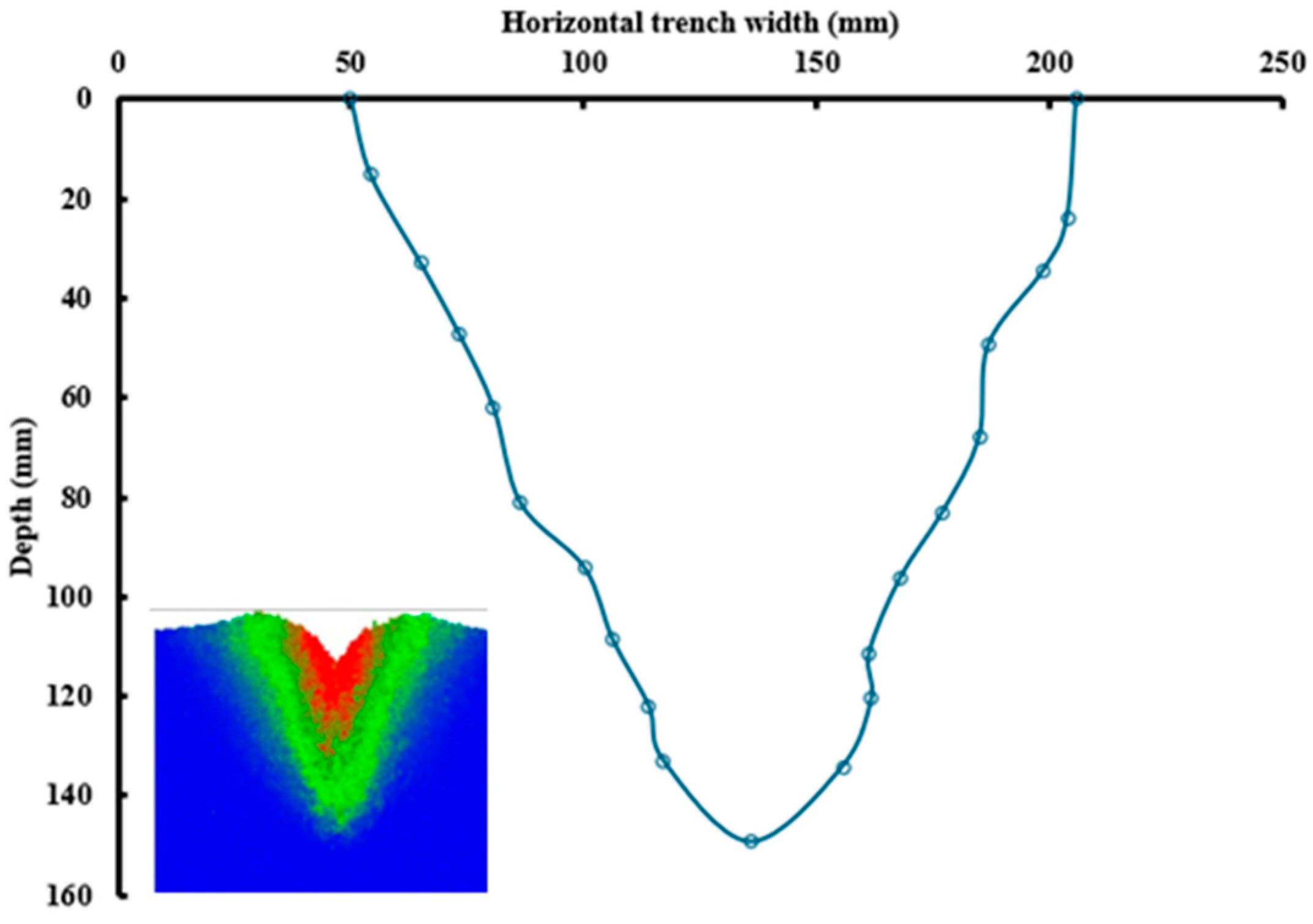

38]. In ImageJ, the disturbed and undisturbed soil sections were distinguished, and a profile line was drawn across the lateral extent of the disturbed soil to generate a graph showing horizontal distance versus depth (in pixels), which was then converted to millimeters. The soil rupture area was estimated from these profiles using the trapezoidal rule for calculating area under the curve in MATLAB (R2022b; MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and reported as a numerical estimate [

39]. These results were compared with the direct measurement approach to validate the consistency and reliability of the DEM model predictions.

2.5. Data Analysis and Optimization

All data were statistically analyzed to evaluate variability and trends across the six tool prototypes. Graphical analyses were conducted to compare minimum, maximum, and mean values for each response variable, including draft force and soil disturbance metrics. To assess whether the differences among tool designs were statistically significant, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. When significant differences were detected, post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s HSD test with a significance level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using JMP Pro 11.0.0 (JMP Statistical Software, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

A multi-response optimization was performed using the Optimization Profiler in JMP Pro to determine the optimal configuration of the liquid manure injector design. This analysis aimed to maximize overall desirability by simultaneously considering multiple performance criteria, specifically minimizing draft force and soil surface disturbance while maximizing subsurface soil rupture. The response variables included draft force, trench width, spoil cross-sectional area, and soil rupture area. The optimization was based on the desirability function methodology developed by [

40], which enables the integration of multiple, potentially conflicting objectives into a single composite desirability score. Individual desirability functions were developed for each response by transforming the measured values of draft force, trench width, spoil cross-sectional area, and soil rupture area into a unitless scale from 0 (undesirable) to 1 (ideal). The optimization framework assigned weights based on the design objectives: minimizing draft force, trench width, and spoil area, while maximizing soil rupture. Draft force received the highest weight (0.40), reflecting its central role in reducing energy demand. Trench width (0.25) and spoil cross-sectional area (0.25) were given moderate weights to balance surface disturbance considerations. The soil rupture area was positively weighted (0.10), but at a lower level than the draft force, recognizing its importance for subsurface loosening, while ensuring energy efficiency remained the dominant criterion. By integrating these objectives, the optimization profiler identified the optimal combination of key design parameters, rake angle, tool width, and tool thickness that provided the best trade-off between reduced energy requirements and effective soil disturbance. The resulting optimized tool design enhances soil–tool interactions, leading to improved manure injection performance and operational efficiency.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated a combined framework of DEM simulation, soil bin testing, and multi-objective optimization for evaluating liquid manure injector shank designs. DEM-based screening efficiently reduced eighteen initial designs to six prototypes, which were then assessed under controlled soil bin conditions. Significant differences in draft force, trench width, spoil cross-sectional area, and soil rupture area were observed, confirming that rake angle, tool width, and tool thickness strongly influence soil–tool interaction. Using a multi-objective desirability approach, Shank S_3 (45° rake, 25 mm thickness, 110 mm width) achieved the highest overall score, representing the most promising trade-off among the tested designs between energy efficiency, minimal surface disturbance, and maximal subsurface loosening. These findings demonstrate the utility of simulation–experiment–optimization workflows for implement design, reducing reliance on extensive field prototyping and enabling data-driven decision-making. From an application standpoint, the results suggest that manufacturers can adopt DEM-assisted design and optimization to refine tool geometries before fabrication, thereby shortening development cycles and improving product performance. Likewise, farmers and equipment operators may select injector shanks with moderate rake angles (around 45°) and optimized dimensions to achieve efficient manure placement with reduced soil disturbance and energy consumption. However, the results are limited to one soil type, moisture, bulk density, and test speed under controlled conditions. Future work should validate the performance of S_3 and other candidate designs under variable soil textures, moisture contents, and real-world operating environments to confirm their agronomic and environmental benefits.