Predicting Structural Traits and Chemical Composition of Urochloa decumbens Using Aerial Imagery and Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

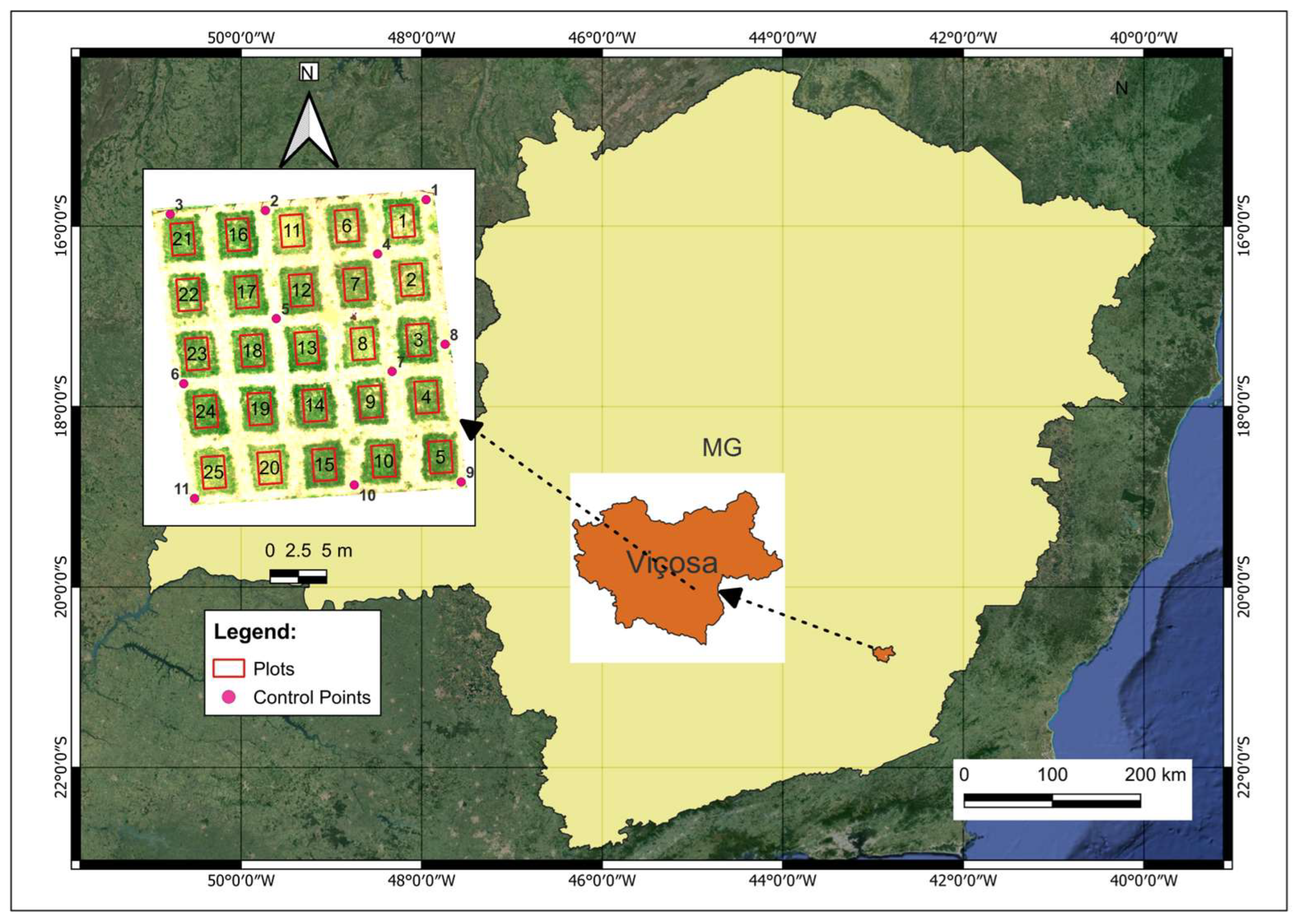

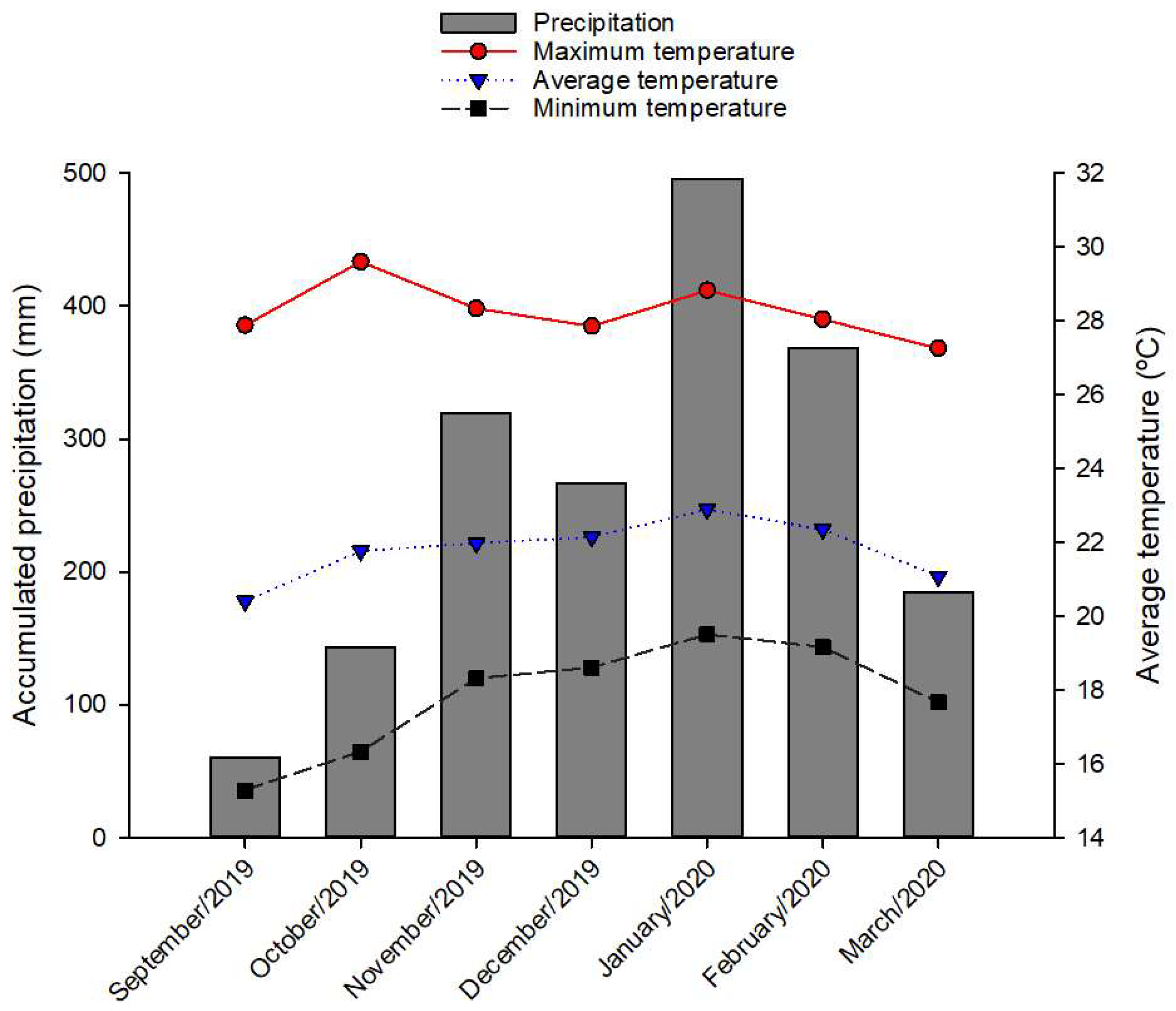

2.1. Site Description and Experimental Design

2.2. Acquisition of Multispectral Images and Forage Evaluations

2.3. Image Pre-Processing

2.4. Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Between Variables

3.2. Principal Component Analysis

3.3. Final Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| RFR | Random Forest Regression |

| UAVs | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| LOOCV | Leave-one-out cross-validation |

| LOGOCV | Leave-One-Group-Out Cross-Validation |

| CP | Crude Protein |

| VIs | Vegetation Indices |

| DM | Dry matter |

| RS | Remote sensing |

References

- IBGE. Rebanho Bovino (Touros e Vacas). Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/explica/producao-agropecuaria/bovinos/br (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Pereira, O.J.R.; Ferreira, L.G.; Pinto, F.; Baumgarten, L. Assessing pasture degradation in the Brazilian Cerrado based on the analysis of MODIS NDVI time-series. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netsianda, A.; Mhangara, P. Aboveground biomass estimation in a grassland ecosystem using Sentinel-2 satellite imagery and machine learning algorithms. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puche, N.; Senapati, N.; Flechard, C.R.; Klumpp, K.; Kirschbaum, M.U.F.; Chabbi, A. Modeling carbon and water fluxes of managed grasslands: Comparing flux variability and net carbon budgets between grazed and mowed systems. Agronomy 2019, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.F.M.; Barão, L.; Morais, T.G.; Domingos, T. “BalSim”: A carbon, nitrogen and greenhouse gas mass balance model for pastures. Sustainability 2019, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, N.; Rahimi Jahangirlou, M.; Jaberi Aghdam, M. Determining Variable Rate Fertilizer Dosage in Forage Maize Farm Using Multispectral UAV Imagery. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2024, 53, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.R.d.S.; de Lima, J.P.; Freitas, R.G.; Dos Reis, A.A.; Amaral, L.R.; Figueiredo, G.K.D.A.; Lamparelli, R.A.C.; Magalhães, P.S.G. Nitrogen variability assessment of pasture fields under an integrated crop-livestock system using UAV, PlanetScope, and Sentinel-2 data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, E.; Lieffering, M.; Guo, J.; Baisden, W.T.; Ausseil, A.-G. Climatic factors influencing New Zealand pasture resilience under scenarios of future climate change. NZGA Res. Pract. Ser. 2021, 17, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojima, D.S.; Chuluun, T.; Galvin, K.A. Social-Ecological Vulnerability of Grassland Ecosystems. Clim. Vulnerability Underst. Addressing Threat. Essent. Resour. 2013, 4, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polley, H.W.; Briske, D.D.; Morgan, J.A.; Wolter, K.; Bailey, D.W.; Brown, J.R. Climate change and North American rangelands: Trends, projections, and implications. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 66, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jank, L.; Barrios, S.C.; Do Valle, C.B.; Simeão, R.M.; Alves, G.F. The value of improved pastures to Brazilian beef production. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, C.T.R.; Bonetti, N.G.Z.; Barrios, S.C.L.; do Valle, C.B.; Torres, G.A.; Techio, V.H. GISH-based comparative genomic analysis in Urochloa P. Beauv. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, V.D.; da Fonseca, D.M.; Lima, M.A.; Martuscello, A.; Paciullo Domingos, S.C.; Chizzotti, F.H.M. Grazing management strategies for Urochloa decumbens (Stapf) R. Webster in a silvopastoral system under rotational stocking. Grass Forage Sci. 2020, 75, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, I.L.; Valente, D.S.M.; Silva, F.F.; Chizzotti, M.L.; Paulino, M.F.; D’Áurea, A.P.; Paciullo, D.S.C.; Pedreira, B.C.; Chizzotti, F.H.M. Prediction of aboveground biomass and dry-matter concentration in brachiaria pastures by combining meteorological data and satellite imagery. Grass Forage Sci. 2021, 76, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delevatti, L.M.; Cardoso, A.S.; Barbero, R.P.; Leite, R.G.; Romanzini, E.P.; Ruggieri, A.C.; Reis, R.A. Effect of nitrogen application rate on yield, forage quality, and animal performance in a tropical pasture. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Mendoza, C.I.; Guzman, D.; Casas, J.; Bastidas, M.; Polanco, J.; Valencia-Ortiz, M.; Montenegro, F.; Arango, J.; Ishitani, M.; Selvaraj, M.G. Predictive Modeling of Above-Ground Biomass in Brachiaria Pastures from Satellite and UAV Imagery Using Machine Learning Approaches. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangjan, W.; Carpenter-Boggs, L.A.; Hudson, T.D.; Sankaran, S. Pasture Productivity Assessment under Mob Grazing and Fertility Management Using Satellite and UAS Imagery. Drones 2022, 6, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistoti, J.; Marcato, J.; Ítavo, L.; Matsubara, E.; Gomes, E.; Oliveira, B.; Souza, M.; Siqueira, H.; Filho, G.S.; Akiyama, T.; et al. Estimating pasture biomass and canopy height in Brazilian Savanna using UAV photogrammetry. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morota, G.; Ventura, R.V.; Silva, F.F.; Koyama, M.; Fernando, S.C. Big data analytics and precision animal agriculture symposium: Machine learning and data mining advance predictive big data analysis in precision animal agriculture. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oliveira, P.S.; Hott, M.C.; Andrade, R.G.; Magalhães Junior, W.C.P. Aplicações da Agricultura de Precisão em Pastagens [Precision Agriculture Applications in Pastures] (Circular Técnica, n. 127); Embrapa: Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil, 2023; Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1151612/1/Aplicacoes-da-agricultura-de-precisao-em-pastagens.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Urquizo, J.; Ccopi, D.; Ortega, K.; Castañeda, I.; Patricio, S.; Passuni, J.; Figueroa, D.; Enriquez, L.; Ore, Z.; Pizarro, S. Estimation of Forage Biomass in Oat (Avena sativa) Using Agronomic Variables through UAV Multispectral Imaging. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, G.; Deng, L.; Tang, Z.; Wang, K.; Sun, W.; Shangguan, Z. Prediction of aboveground grassland biomass on the Loess Plateau, China, using a random forest algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljanen, N.; Honkavaara, E.; Näsi, R.; Hakala, T.; Niemeläinen, O.; Kaivosoja, J. A novel machine learning method for estimating biomass of grass swards using a photogrammetric canopy height model, images and vegetation indices captured by a drone. Agriculture 2018, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defalque, G.; Santos, R.; Bungenstab, D.; Echeverria, D.; Dias, A.; Defalque, C. Machine learning models for dry matter and biomass estimates on cattle grazing systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brovelli, M.A.; Crespi, M.; Fratarcangeli, F.; Giannone, F.; Realini, E. Accuracy assessment of high resolution satellite imagery orientation by leave-one-out method. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2008, 63, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.B.; Gonzaga, G.; Santos, D.F.; Reboita, M.S. Classificação climática de Köppen e de Thornthwaite para Minas Gerais: Cenário atual e projeções futuras. Rev. Bras. Climatol. 2018, 14, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, A.M. Sensoriamento Remoto na Avaliação de Pastagem de Brachiaria Decumbens [Remote Sensing in the Evaluation of Brachiaria Decumbens Pasture]. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Metereologia. Available online: https://portal.inmet.gov.br/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- IATEC. Micasense Rededge-MX Multiespectral 5-Bandas (Versão Nova). Available online: https://www.iatecps.com/product-page/micasense-rededge-mx-multiespectral-5-bandas-vers%C3%A3o-nova (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Detmann, E.; Silva, L.F.C.; Rocha, G.C.; Palma, M.N.N.; Rodrigues, J.P.P.L. Métodos para Análise de Alimentos; INCT, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Departamento de Zootecnia: Viçosa, Brazil, 2012; 214p. [Google Scholar]

- Agisoft Helpdesk Portal. Available online: https://agisoft.freshdesk.com/support/solutions/articles/31000148780-micasense-rededge-mx-processing-workflow-including-reflectance-calibration-in-agisoft-metashape-pro (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote estimation of canopy chlorophyll content in crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L08403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a two-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N.; Blaustein, J. Use of a Green Channel in Remote Sensing of Global Vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.J.; Rodriguez, D.; Christensen, L.K.; Belford, R.; Sadras, V.O.; Clarke, T.R. Spectral and thermal sensing for nitrogen and water status in rainfed and irrigated wheat environments. Precis. Agric. 2006, 7, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.; Curran, P.J. Evaluation of the MERIS terrestrial chlorophyll index (MTCI). Adv. Space Res. 2007, 39, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) 295. Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, R.H.; Latifovic, R. Mapping insect-induced tree defoliation and mortality using coarse spatial resolution satellite imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Chen, H.; Wu, B.; Nasanbat, E.; Yan, N.; Davdai, B. A practical satellite-derived vegetation drought index for arid and semi-arid grassland drought monitoring. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, M.; Sagan, V.; Sidike, P.; Daloye, A.M.; Erkbol, H.; Fritschi, F.B. Crop monitoring using satellite/UAV data fusion and machine learning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Fang, S.; Zhu, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, S.; Gong, Y.; Peng, Y. Remote estimation of rice yield with unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) data and spectral mixture analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Guerschman, J.; Shendryk, Y.; Henry, D.; Harrison, M.T. Estimating pasture biomass using sentinel-2 imagery and machine learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J.; Shine, P.; Brien, B.O.; Donovan, M.O.; Murphy, M.D. Utilising grassland management and climate data for more accurate prediction of herbage mass using the rising plate meter. Precis. Agric. 2021, 22, 1189–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Koper, N.; Guo, X. Quantifying the influences of grazing, climate and their interactions on grasslands using Landsat TM images. Grassl. Sci. 2018, 64, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théau, J.; Lauzier-Hudon, É.; Aubé, L.; Devillers, N. Estimation of forage biomass and vegetation cover in grasslands using UAV imagery. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schucknecht, A.; Seo, B.; Krämer, A.; Asam, S.; Atzberger, C.; Kiese, R. Estimating dry biomass and plant nitrogen concentration in pre-Alpine grasslands with low-cost UAS-borne multispectral data-a comparison of sensors, algorithms, and predictor sets. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 2699–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiscornia, G.; Baethgen, W.; Ruggia, A.; Do Carmo, M.; Ceccato, P. Can we monitor height of native grasslands in Uruguay with earth observation? Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, I.L.; Valente, D.S.M.; de Oliveira, T.F.; Montagner, D.B.; Euclides, V.P.B.; Chizzotti, F.H.M. Canopy height and biomass prediction in Mombaça guinea grass pastures using satellite imagery and machine learning. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1638–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obanawa, H.; Yoshitoshi, R.; Watanabe, N.; Sakanoue, S. Portable lidar-based method for improvement of grass height measurement accuracy: Comparison with SFM methods. Sensors 2020, 20, 4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Oenema, J.; Sijbrandij, F.; Jindo, K.; Noij, G.J.; Hollewand, F.; Meurs, B.; Hoving, I.; van der Vlugt, P.; Bouten, M.; et al. Dry Matter Yield and Nitrogen Content Estimation in Grassland Using Hyperspectral Sensor. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollinger, S.V. Sources of variability in canopy reflectance and the convergent properties of plants. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesingha, J.; Astor, T.; Schulze-Brüninghoff, D.; Wengert, M.; Wachendorf, M. Predicting Forage Quality of Grasslands Using UAV-Borne Imaging Spectroscopy. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Verrelst, J.; Féret, J.B.; Hank, T.; Wocher, M.; Mauser, W.; Camps-Valls, G. Retrieval of aboveground crop nitrogen content with a hybrid machine learning method. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 92, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, V.R.; Hott, M.C.; Andrade, R.G.; Goliatt, L. Hybrid machine learning methods combined with computer vision approaches to estimate biophysical parameters of pastures. Evol. Intell. 2023, 16, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | FFM (Kg ha−1) | DFM (Kg ha−1) | CH (cm) | DEN (Kg DM ha−1 cm−1) | DMC (%) | CP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 175 | 175 | 175 | 175 | 175 | 175 |

| Minimum | 165 | 58 | 11 | 4 | 12 | 7 |

| Maximum | 30,974 | 5720 | 71 | 136 | 40 | 25 |

| Mean | 7653 | 1492 | 29 | 47 | 22 | 17 |

| Median | 5339 | 1026 | 24 | 42 | 23 | 19 |

| Standard D. | 6752 | 1239 | 14 | 28 | 6 | 4 |

| CV (%) | 88 | 83 | 47 | 61 | 28 | 24 |

| Vegetation Indices | Equations | References |

|---|---|---|

| CIRE (REDEDGE Chlorophyll Index) | (NIR/REDEDGE) − 1 | [32] |

| EVI (Enhanced Vegetation Index) | [(2.5(NIR − RED))/(NIR + 6 RED − 7.5BLUE + 1)] | [33] |

| EVI2 (Enhanced Vegetation Index 2) | [2.5(NIR − RED)/(NIR + 2.4 RED + 1)] | [33] |

| GCVI (GREEN Chlorophyll Vegetation Index) | (NIR/GREEN) − 1 | [32] |

| GNDVI (GREEN Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) | [(NIR − GREEN)/(NIR + GREEN)] | [34] |

| NDRE (Normalized Difference REDEDGE) | [(NIR − REDEDGE)/(NIR + REDEDGE)] | [35] |

| NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) | [(NIR − RED)/(NIR + RED)] | [36] |

| MTCI (MERIS Terrestrial Chlorophyll Index) | [(NIR − REDEDGE)/(REDEDGE − RED)] | [37] |

| OSAVI (Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index) | [(NIR − RED)/(NIR + RED + 0.16)] | [36] |

| SAVI (Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index) | [(1.5(NIR − RED))/(NIR + RED + 0.50)] | [36] |

| SR (Simple Ratio) | NIR/RED | [38] |

| SREDEDGE (Simple Ratio REDEDGE) | NIR/REDEDGE | [39] |

| Variables | Principal Components (PCs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | |

| NDVI | −0.240 | −0.031 | −0.073 | 0.120 | −0.362 |

| NDRE | −0.249 | −0.067 | −0.002 | −0.151 | −0.022 |

| GNDVI | −0.250 | −0.061 | −0.007 | −0.061 | −0.118 |

| CIRE | −0.244 | −0.062 | 0.043 | −0.202 | 0.200 |

| MTCI | −0.238 | −0.061 | 0.058 | −0.273 | 0.227 |

| SR | −0.231 | −0.108 | 0.067 | −0.043 | 0.322 |

| SREDEDGE | −0.244 | −0.062 | 0.043 | −0.202 | 0.200 |

| EVI | −0.226 | 0.290 | 0.063 | −0.095 | −0.158 |

| EVI2 | −0.229 | 0.280 | 0.064 | −0.085 | −0.124 |

| SAVI | −0.233 | 0.246 | 0.049 | −0.058 | −0.181 |

| OSAVI | −0.244 | 0.240 | −0.240 | −0.240 | −0.240 |

| GCVI | −0.242 | −0.068 | 0.092 | −0.134 | 0.266 |

| BLUE | 0.230 | 0.196 | 0.101 | −0.206 | 0.231 |

| GREEN | 0.216 | 0.351 | 0.062 | 0.013 | 0.055 |

| RED | 0.233 | 0.133 | 0.094 | −0.161 | 0.351 |

| REDEDGE | 0.172 | 0.494 | 0.099 | 0.069 | −0.019 |

| NIR | −0.171 | 0.473 | 0.137 | −0.212 | 0.047 |

| Precipitation | −0.171 | 0.154 | −0.452 | 0.268 | 0.351 |

| Maximum temperature | −0.054 | −0.135 | 0.715 | 0.312 | 0.047 |

| Average temperature | −0.186 | 0.082 | 0.312 | 0.529 | 0.183 |

| Minimum temperature | −0.186 | 0.175 | −0.314 | 0.443 | 0.238 |

| Variation explained (%) | 74.18 | 9.94 | 7.62 | 4.42 | 2.81 |

| HYP | FFM (Kg ha−1) | DFM (Kg ha−1) | CH (cm) | DEN (Kg DM ha−1 cm−1) | DMC (%) | CP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N estimators | 500 | 500 and 175 | 550 and 205 | 50 | 50 and 5500 | 249 and 500 |

| Max depth | 20 | 10 and 7 | 11 and 17 | 20 and 18 | 3 and 17 | 3 |

| Min samples split | 4 and 9 | 2 and 6 | 5 and 4 | 4 and 2 | 10 and 2 | 2 and 9 |

| Min samples leaf | 6 | 1 and 2 | 2 and 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 and 6 |

| HYP | FFM (Kg ha−1) | DFM (Kg ha−1) | CH (cm) | DEN (Kg DM ha−1 cm−1) | DMC (%) | CP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 640.24 and 850.98 | 250.85 and 592.25 | 501.11 and 20.86 | 161.74 and 385.14 | 0.1 and 313.95 | 0.1 and 255.84 |

| epsilon | 0.24 and 0.56 | 0.32 and 0.01 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 and 0.01 | 1.0 and 0.01 |

| gamma | 0.09 and 0.06 | 0.06 and 0.02 | 0.02 and 0.0001 | 0.0001 and 0.004 | 0.77 and 0.001 | 1.0 and 0.0001 |

| Variables | Best Model | Principal Components | R2 | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFM (Kg ha−1) | RFR | PC3 | 0.82 | 2894.10 | 1850.90 |

| DFM (Kg ha−1) | SVR | PC5 | 0.68 | 719.87 | 542.75 |

| CH (cm) | SVR | PC3 | 0.44 | 10.80 | 8.06 |

| DEN (Kg DM ha−1 cm−1) | SVR | PC5 | 0.56 | 18.99 | 14.30 |

| DMC (%) | MLR | PC5 | 0.64 | 3.83 | 3.17 |

| CP (%) | SVR | PC5 | 0.22 | 3.84 | 3.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souza, I.F.R.d.; Lisboa, A.M.; Bretas, I.L.; Valente, D.S.M.; Pinto, F.d.A.d.C.; Carvalho, F.B.P.d.; Moura, L.G.S.; Valote, P.D.; Chizzotti, F.H.M. Predicting Structural Traits and Chemical Composition of Urochloa decumbens Using Aerial Imagery and Machine Learning. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120406

Souza IFRd, Lisboa AM, Bretas IL, Valente DSM, Pinto FdAdC, Carvalho FBPd, Moura LGS, Valote PD, Chizzotti FHM. Predicting Structural Traits and Chemical Composition of Urochloa decumbens Using Aerial Imagery and Machine Learning. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(12):406. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120406

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouza, Iuly Francisca Rodrigues de, Aureana Matos Lisboa, Igor Lima Bretas, Domingos Sárvio Magalhães Valente, Francisco de Assis de Carvalho Pinto, Filipe Bueno Pena de Carvalho, Lara Gabriely Silva Moura, Priscila Dornelas Valote, and Fernanda Helena Martins Chizzotti. 2025. "Predicting Structural Traits and Chemical Composition of Urochloa decumbens Using Aerial Imagery and Machine Learning" AgriEngineering 7, no. 12: 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120406

APA StyleSouza, I. F. R. d., Lisboa, A. M., Bretas, I. L., Valente, D. S. M., Pinto, F. d. A. d. C., Carvalho, F. B. P. d., Moura, L. G. S., Valote, P. D., & Chizzotti, F. H. M. (2025). Predicting Structural Traits and Chemical Composition of Urochloa decumbens Using Aerial Imagery and Machine Learning. AgriEngineering, 7(12), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120406