From a Comprehensive Pool to a Project-Specific List of Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring the Positive Energy Transition of Smart Cities—An Experience-Based Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Review of Smart City KPI Frameworks

2.1. Smart Cities Information System (SCIS) and CITYkeys

2.2. Other Positive Energy Transformation Projects

2.3. Scientific Publications

2.4. Other Relevant Frameworks and Initiatives

2.4.1. UN’s Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals

2.4.2. United for Smart Sustainable Cities (U4SSC) Initiative

2.4.3. ISO/FDIS 37122—Indicators for Smart Cities

2.4.4. ISO/FDIS 37120—Indicators for City Services and Quality of Life

2.4.5. ETSI Technical Specification on KPIs for “Sustainable Digital Multiservice Cities”

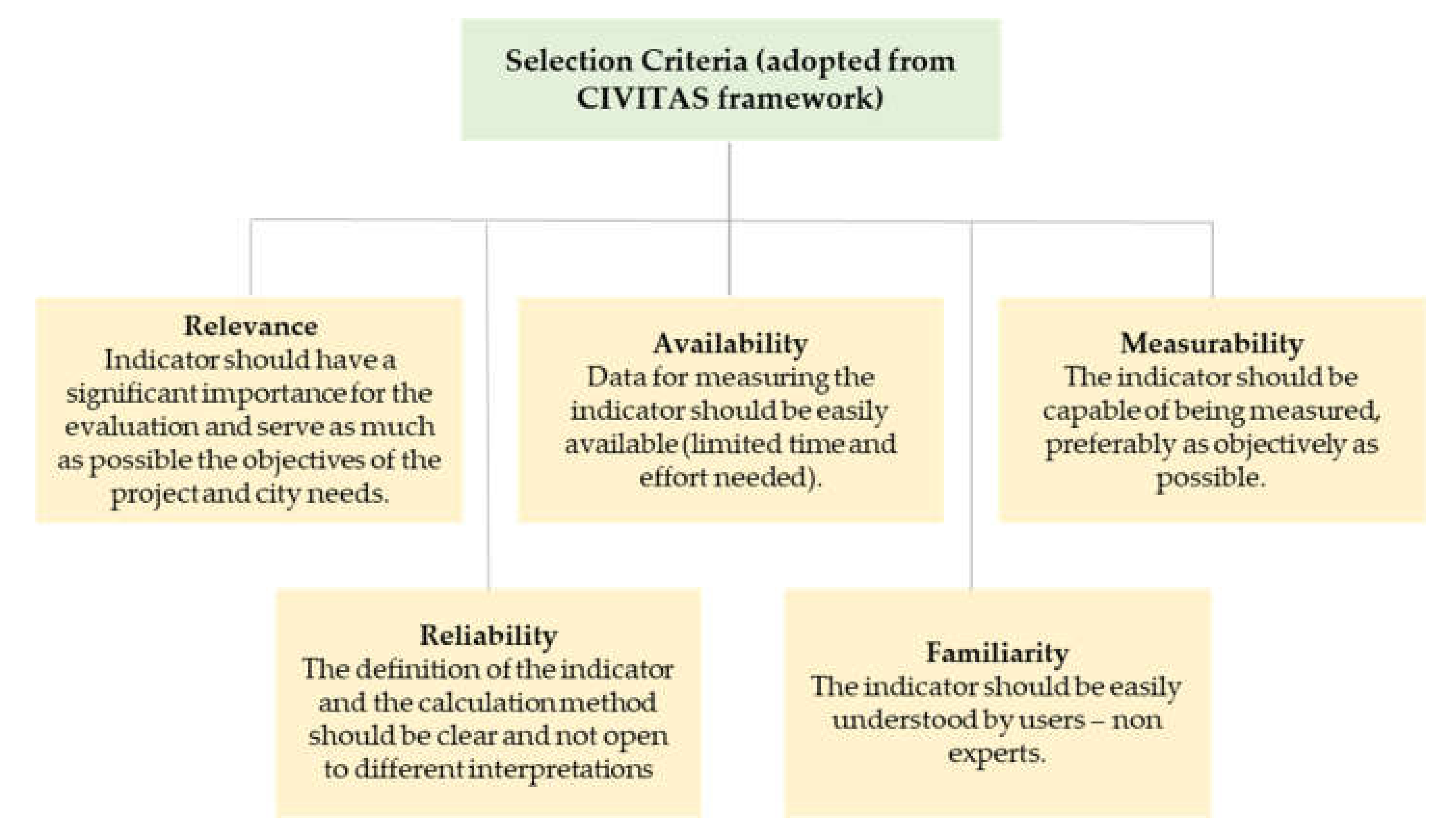

3. Proposed Evaluation Methodology for Selecting KPIs

3.1. Dimensions Definition for Indicator Analysis

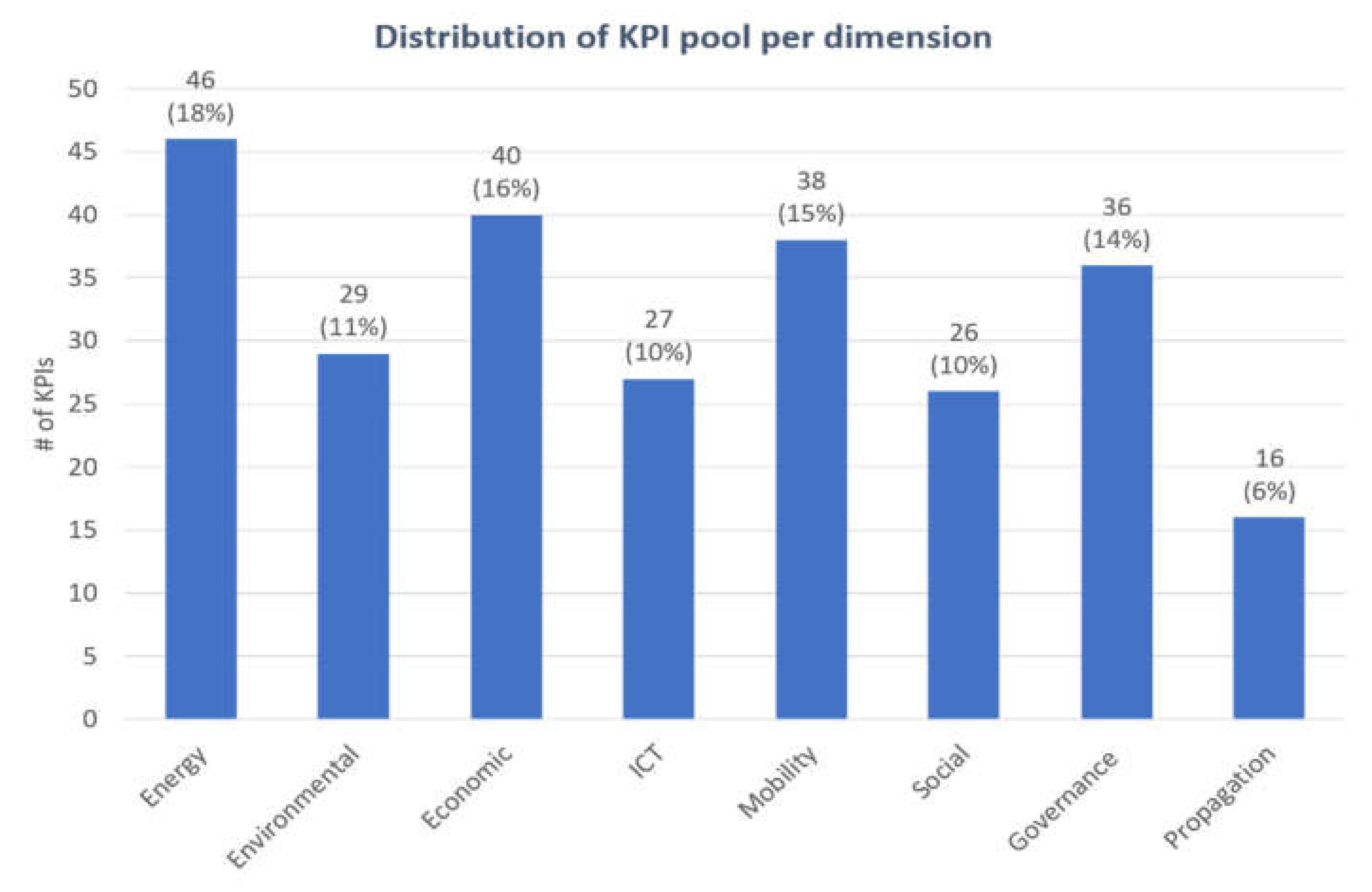

3.2. Screening Process—Development of an Indicator Pool

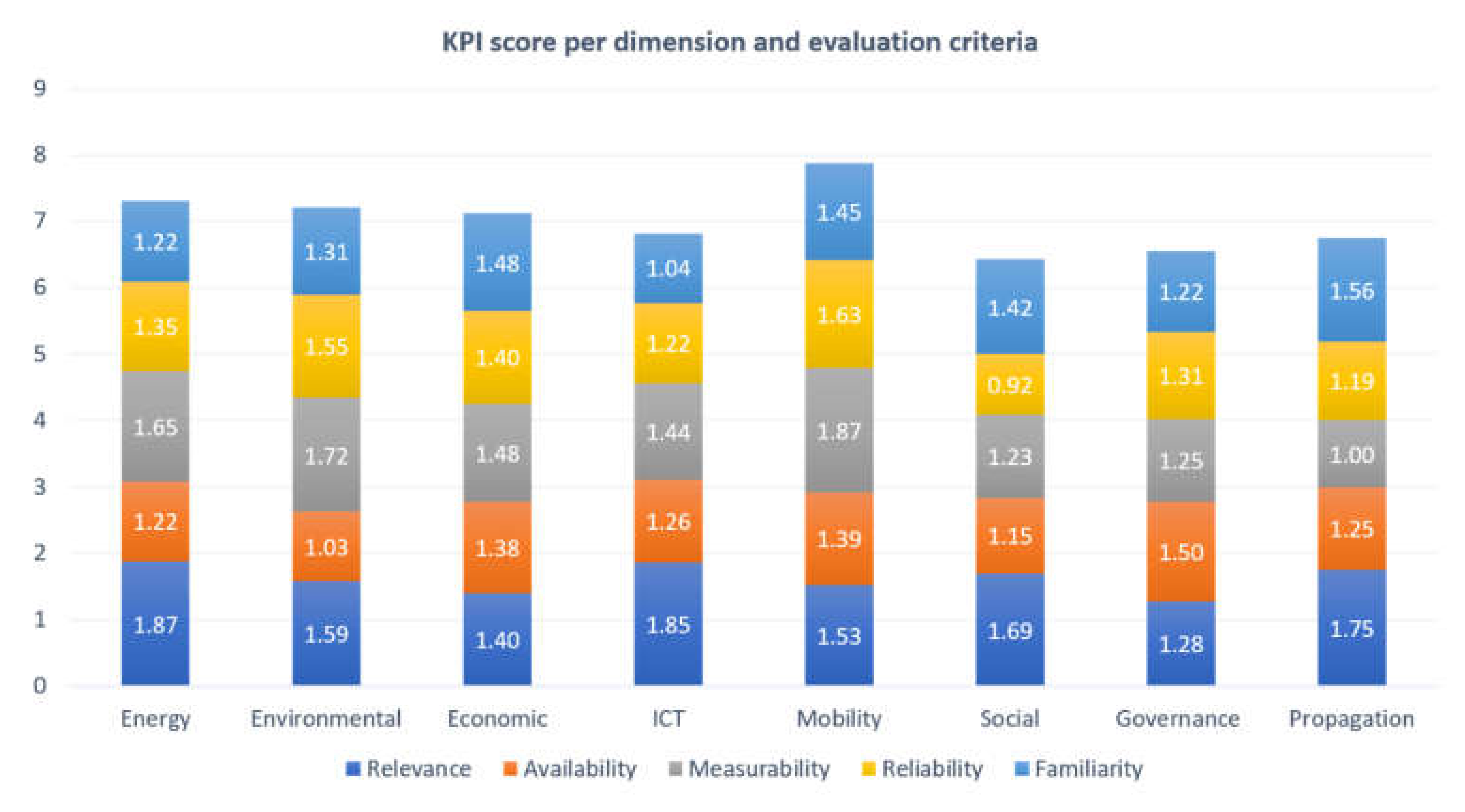

3.3. Evaluation Process—Towards a Final KPI List

- Completeness: The set of indicators should consider all aspects of the implementation of smart city projects. In that respect, indicators had to be selected to cover all defined dimensions as described in Section 3.1.

- Non-redundancy: The set of indicators should not measure the same aspect of a subtheme. Extra care was given as to not include indicators that assess the same parameter (double counting) even if the score was higher in comparison with other indicators.

- Independence: Small changes in the measurements of an indicator should not influence preferences assigned to other indicators in the evaluation.

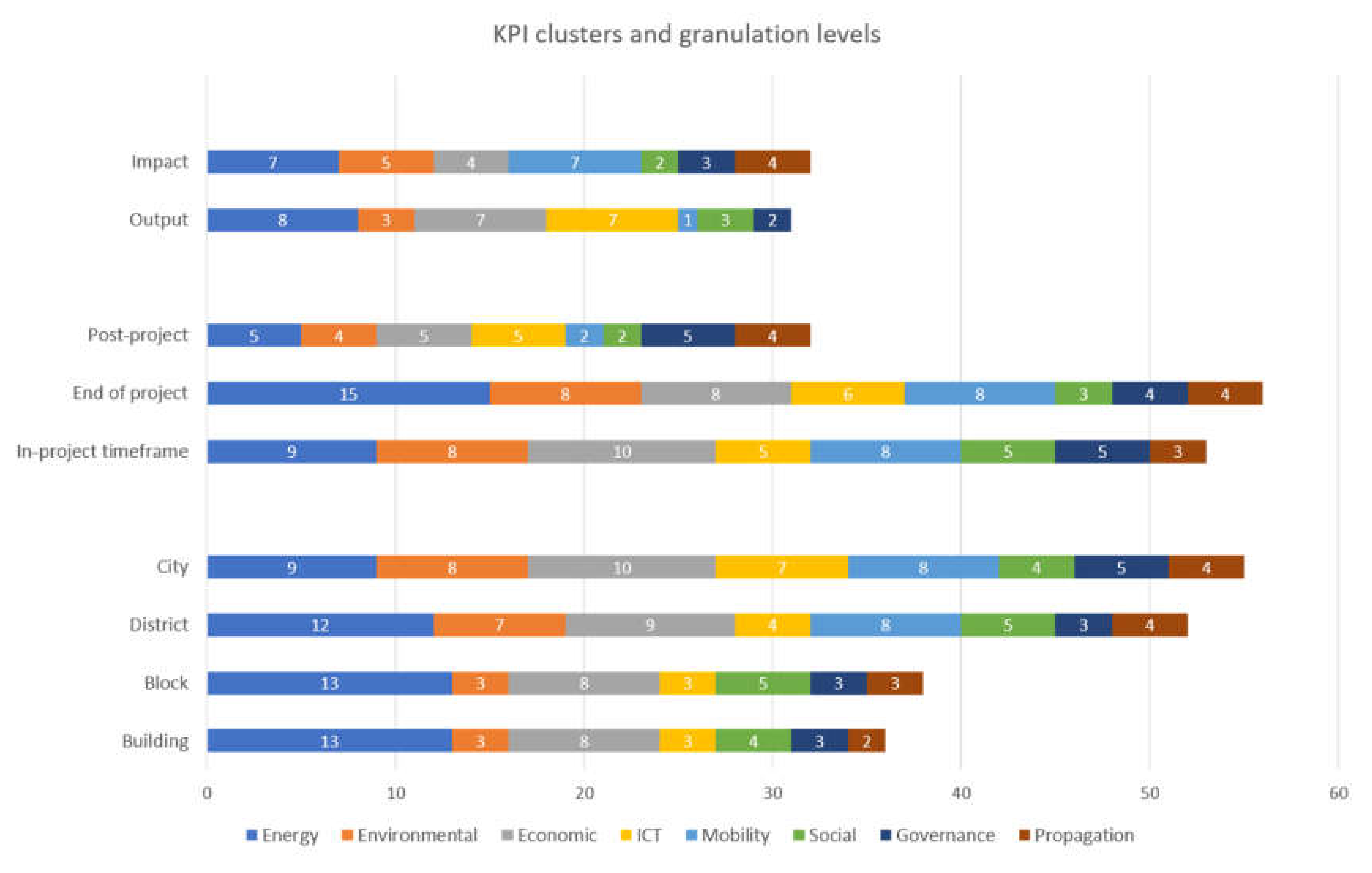

3.4. Clustering and Granularity Evaluation Levels

3.4.1. Orientation—Type of KPIs

- Output-oriented KPIs: These KPIs are simple concrete indicators for monitoring the progress and effectiveness of implementation (e.g., number of smart meters, charging points, users of apps).

- Impact (outcome) oriented KPIs: These indicators should assess the benefits of interventions as well as the higher-level goals to which energy transition projects will contribute (e.g., savings in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, improved air quality, increased replicability etc.). The KPIs assessing the impact-oriented evaluation level are extremely important as they can be considered as the end-result which positive energy transition development projects are pursuing through their implementation activities.

3.4.2. From a Building to a City Level—Spatial Scale

3.4.3. From Present to Future—Temporal Scale

- In-project (short-term): In this temporal level, indicators should be evaluated during the development project duration. This temporal level of evaluation provides important information on the progress of a solution/service during the project and its performance relative to the main objectives of the project. The energy transition of the LH cities during the project’s lifetime can be easily assessed by evaluation in such short-term intervals.

- End-of-project (mid-term): The assessment of technologies at the end of the project provides information on the project’s overall performance and impact in the local societies. Aggregation of the short-term level can be used to calculate the indicators by summation, averaging, etc. whenever this is applicable.

- Post-project (long-term): The post-project assessment falls outside of the projects’ duration. Nevertheless, cities can continue monitoring the performance of solutions and their impact on their bold city visions. The solutions to be implemented during a smart city project are not static, and their interaction with other city solutions as well as performance in the long run should be evaluated in such a temporal scale to assess their long-standing success and provide feedback for future projects.

4. Results

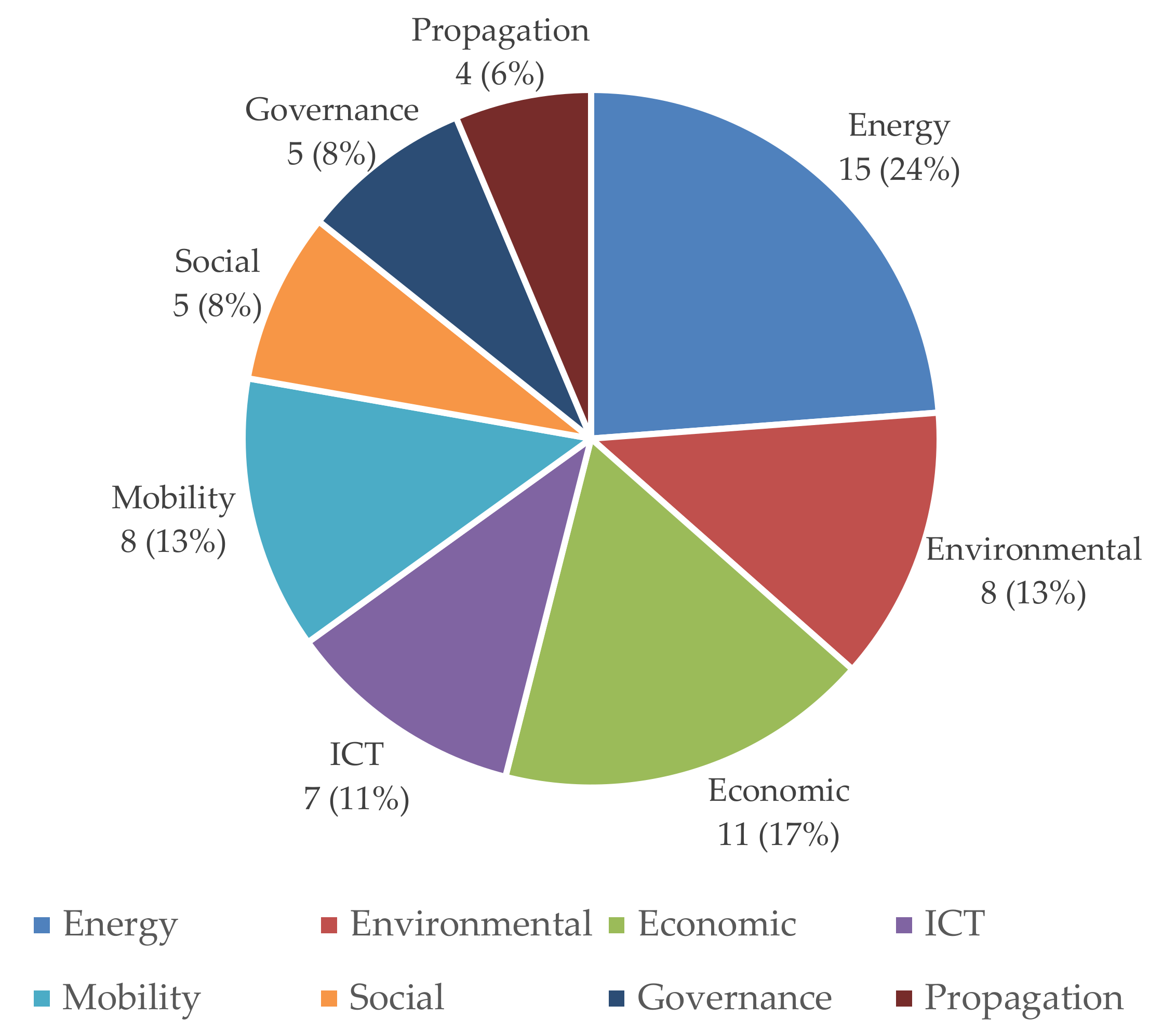

4.1. Evaluation Results—Final KPI List of POCITYF Project

4.2. Clustering and Granularity Analytics

- Is it oriented towards the positive energy transformation project impact or is it focused on the output (progress and performance) of a specific action? A binary choice has been made.

- Should it be evaluated multiple times during the project lifetime, only once at the end of the project or should evaluation be performed in the years following the project end? Multiple (more than one) choices for this temporal scale of evaluation were possible.

- Does it apply on a building, block, district or city level? Multiple (more than one) choices for this spatial scale of evaluation were possible.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- REN21. Renewables in Cities Global Status Report; Paris: REN21 Secretariat; REN21: Paris, France, 2020; ISBN 978-3-948393-00-7. [Google Scholar]

- AirVisual. World’s Most Polluted Cities in 2019—PM2.5 Ranking. Available online: https://www.iqair.com/world-most-polluted-cities (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- TomTom. Traffic Index 2019—Live Congestion Statistics and Historical Data. Available online: https://www.tomtom.com/en_gb/traffic-index/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. COM (2019) 640 Final; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 11 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bifulco, F.; Tregua, M.; Amitrano, C.C.; D’Auria, A. ICT and sustainability in smart cities management. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvestre, M.L.; Favuzza, S.; Sanseverino, E.R.; Zizzo, G. How Decarbonization, Digitalization and Decentralization are changing key power infrastructures. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemment, D.; Woods, M.; Appadoo, V.; Bui, L. Community Key Performance Indicators (Community KPIs) for the IoT and Smart Cities; FutureEverything: Manchester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R.; Lauriault, T.P.; McArdle, G. Knowing and governing cities through urban indicators, city benchmarking and real-time dashboards. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P. Smart city definition, goals and performance. In Smart City Implementation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, P.; Jongeneel, S.; Rovers, V.; Neumann, H.-M.; Airaksinen, M.; Huovila, A. CITYkeys indicators for smart city projects and smart cities. CITYkeys Rep. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. A typology of smart city assessment tools and indicator sets. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huovila, A.; Bosch, P.; Airaksinen, M. Comparative analysis of standardized indicators for Smart sustainable cities: What indicators and standards to use and when? Cities 2019, 89, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakoglou, K.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Giourka, P.; Svensson, I.-L.; Tsarchopoulos, P.; Tryferidis, A.; Tzovaras, D. A Methodological Framework for the Selection of Key Performance Indicators to Assess Smart City Solutions. Smart Cities 2019, 2, 269–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Positive Energy CITY Transformation Framework | POCITYF Project | H2020 | CORDIS | European Commission. Available online: https://pocityf.eu/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- European Commission. SET-Plan Action 3.2, Implementation Plan, Europe to Become A Global Role Model in Integrated, Innovative Solutions for the Planning, Deployment, and Replication of Positive Energy Districts; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- SCIS Essential Monitoring Guides. Smartcities Information System. Available online: https://smartcities-infosystem.eu/library/resources/scis-essential-monitoring-guides (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Smart Cities and Community Lighthouse Projects. Smartcities Information System. Available online: https://smartcities-infosystem.eu/scc-lighthouse-projects (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Tsarchopoulos, P. IRIS D1.1: Report on the List of Selected KPIs for Each Transition Track. Available online: https://irissmartcities.eu/public-deliverables (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- REPLICATE-D10.2: Report on Indicators for Monitoring at City Level. Available online: https://replicate-project.eu/newsroom/downloads/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- MatchUp-D1.1: Indicators Tools and Methods for Advanced City Modelling and Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.matchup-project.eu/technical-insights/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- SmartEnCity-D7.2: Monitoring and Evaluation: KPIs Definition. Available online: https://www.smartencity.eu/ttps://smartencity.eu/news/detail/?rx_call=114 (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- MySMARTLife: D5.1-Integrated Evaluation Procedure. Available online: https://www.mysmartlife.eu/publications-media/public-deliverables/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- SHARING CITIES-D8.1: Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework. Available online: http://www.sharingcities.eu/sharingcities/deliverables (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- TRIANGULUM-D2.1: Common Monitoring and Impact Assessment Framework. Available online: https://www.triangulum-project.eu/?page_id=119 (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- GrowSmarter: Publications-D5.1: Evaluation Plan. Available online: https://grow-smarter.eu/inform/publications/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- +CityxChange, D7.1-Approach and Methodology for Monitoring and Evaluation. Available online: https://cityxchange.eu/article-categories/deliverables/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- STARDUST-D7.3: Business Models and KPIs Analysis and Validation for Lighthouse Cities Interventions. Available online: https://stardustproject.eu/resources/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Akande, A.; Cabral, P.; Gomes, P.; Casteleyn, S. The Lisbon ranking for smart sustainable cities in Europe. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Lee, C.; Hashim, H.; Chen, B. A holistic low carbon city indicator framework for sustainable development. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, P.; Temporelli, A. Smartainability: A methodology for assessing the sustainability of the smart city. Energy Procedia 2017, 111, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’O, G.; Bruni, E.; Panza, A.; Sarto, L.; Khayatian, F. Evaluation of cities’ smartness by means of indicators for small and medium cities and communities: A methodology for Northern Italy. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 34, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; O’Donnell, J.; García-Castro, R.; Vega-Sánchez, S. Identifying stakeholders and key performance indicators for district and building energy performance analysis. Energy Build. 2017, 155, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M.; Nagao, T.; Hannoe, S.; Nakamura, J. New key performance indicators for a smart sustainable city. Sustainability 2016, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, P.; Giordano, S.; Farouh, H.; Yousef, W. Modelling the smart city performance. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 25, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Global SDG Indicators Database. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/database/ (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- ITU. Collection Methodology for Key Performance Indicators for Smart Sustainable Cities; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 37122: Sustainable Development in Communities-Indicators for Smart Cities; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 37120: Sustainable Cities and Communities-Indicators for City Services and Quality of Life; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CEN, C. SSCC-CG final report. Smart and Sustainable Cities and Communities Coordination Group; ETSI: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CEN-CENELEC. Making Standards for Europe-Smart Cities. Available online: https://www.cencenelec.eu/standards/Sectorsold/SmartLiving/smartcities/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- ETSI. TS 103 463 V1.1.1 Access, Terminals, Transmission and Multiplexing (ATTM); Key Performance Indicators for Sustainable Digital Multiservice Cities; ETSI: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ETSI. GS OEU 019 V1.1.1 Operational Energy Efficiency for Users (OEU); KPIs for Smart Cities; ETSI: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rooijen, T.; Nesterova, N. Deliverable 4.10: Applied framework for evaluation in CIVITAS PLUS II, WP4, May 31 2013; CivitasWiki Project; Grant Agreement No.: 296081; CIVITAS Secretariat, EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chordant-ABI Research. Role of Smart Cities for Economic Development. White Paper. 2018. Available online: https://www.chordant.io/white_papers/abi-research-role-of-smart-cities-for-economic-development (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Mobility. Center for Smart Cities. Available online: https://www.ict-smart-cities-center.com/en/smart-cities/mobilitaet/ (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Dameri, R.P. Using ICT in Smart City. In Smart City Implementation: Creating Economic and Public Value in Innovative Urban Systems; Dameri, R.P., Ed.; Progress in IS.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 45–65. ISBN 978-3-319-45766-6. [Google Scholar]

- Luthander, R.; Widén, J.; Nilsson, D.; Palm, J. Photovoltaic self-consumption in buildings: A review. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project Name | Assessment Framework |

|---|---|

| IRIS Integrated and Replicable Solutions for Co-Creation In Sustainable Cities Ref. [19] | The assessment framework uses an agile and holistic approach defining a set of 75 KPIs categorized in six (6) dimensions—technical, environmental, economic, social, ICT and legal—along with a targeted clustering of solutions in five (5) Transition Tracks as follows: TT#1-Smart renewables and closed-loop energy-positive districts, TT#2- Smart Energy Management and Storage for Grid Flexibility, TT#3-Smart e-Mobility Sector, TT#4-City Innovation Platforms (CIP) and TT#5-Citizen Engagement and Co-Creation. Indicative calculated thresholds for scalar quantification and monitoring performance of the solutions through the assessment criteria are also proposed. |

| REPLICATE Renaissance of Places with Innovative Citizenship and Technologies Ref. [20] | The proposed KPI framework contains a total of 56 KPIs classified under seven (7) dimensions covering as a whole city performance; City description (5 indicators), Energy and Environment (14 indicators), Mobility and Transport (14 indicators), Infrastructure (6 indicators), Governance (5 indicators), Social (5 indicators), and Economy and Finance (7 indicators). The indicators are further analyzed into three evaluation/applicability levels; a) National/ Regional, b) Local / City, c) District. |

| MATCHUP Maximizing the Upscaling and replication potential of high-level urban transformation strategies. Ref. [21] | MatchUp’s evaluation framework is based on the concept of sustainable development, including two (2) evaluation levels (city level and project level) and a total of 188 indicators. The indicators have been classified under three (3) dimensions, namely environment, economy and social, and grouped into four (4) fields of implementation activities: a) Energy Efficiency in Buildings and Districts, b) Mobility/Transport, c) ICT and Urban Platforms and d) Citizens and Society, along with some additional indicators related to Governance. |

| SMARTEnCITY Towards Smart Zero CO2 Cities across Europe Ref. [22] | The evaluation framework was developed considering the type of implemented solutions within the project; district renovation, urban mobility and citizen engagement; adopting indicators grouped into four (4) categories—technical, environmental, social and economic—and determining five (5) evaluation protocols—Energy Assessment, ICT, LCA, Mobility and Cross-Cutting. A list of KPIs for each category (technical, environmental, social, and economic) and by type of intervention (district renovation, mobility and citizen engagement) is provided, with a total of 149 indicators. |

| MySMARTLIFE Smart Transition of EU cities towards a new concept of Smart Life and Economy Ref. [23] | The presented evaluation framework defines a total of 151 KPIs classified across six (6) fields—Energy and Environment, Mobility and Transport, Urban Infrastructure, Citizens, Economy and Governance—while at the same time adopting the five (5) major themes of CITYkeys (People, Planet, Prosperity, Governance and Propagation). Expected impacts are grouped into five (5) specific categories: energy, environmental, economic, social and policy impacts. The framework adopts a twofold evaluation approach in order to measure the demonstration activities: project level (i.e., demonstration areas) and city level. City-level evaluation is strongly related to the overall smart city concept, aiming to identify the main challenges of the cities with city indicators and audits, while at the project level, the target is to assess the effects of the project actions in the demo sites with regards to project pillars. |

| SHARINGCITIES Building Smart Cities Together Ref. [24] | The proposed framework attempts to deliver the effects of the People/Place/Platform (PPP) measures in this project, setting evaluation targets categorized into six (6) domains: a) technical performance; b) attitudes and behaviors; c) wider systemic and environmental impacts; d) security, safety and sustainability; e) institutional and business consequences and f) economic and social implications. Key targets concern the “Place” demonstrations, which consist of four different fields: Building Retrofit and Local RES Generation, Sustainable Energy Management Systems, Shared e-Mobility, Smart Lampposts. In this context, the framework is structured around a final set of 127 KPIs. |

| TRIANGULUM The Three Point Project / Demonstrate. Disseminate. Replicate. Ref. [25] | The project introduces a monitoring and impact assessment framework based on a seven-stage methodology for defining expected impacts, resulting in a total of 79 indicators relevant to the following five (5) impact domains: Energy, Transport, Citizen Engagement, Socio-economic/financial and ICT deployment; aligned also well with both the preferred metrics and the respective commitments of the cities. The framework of this project provides an extensive background as to how cities gather data on energy and transport. |

| GROWSMARTER Transforming Cities for a Smart, Sustainable Europe Ref. [26] | The assessment framework of the project is grounded on three (3) main dimensions which are the categories of the project interventions—better quality of life, environmental and economic–including also various sub-domains and agreed-upon relevant goals, leading to the definition of 104 indicators to measure and evaluate project/city performance. The first category, Low Energy Districts, is divided also into two sub-categories: Building Evaluation and Local Evaluation. |

| +CityxChange Positive City ExChange Ref. [27] | The specific evaluation framework builds upon a holistic approach including KPIs from SCIS focusing on technical and economic aspects of energy-related measures, as well as KPIs specifically defined for the project to measure unique interventions and social impact of the project on citizens. The KPI framework is divided into the three (3) core themes: a) Integrated Planning and Design (IPD), including KPIs measuring the impact of larger interventions to set up tools and regulations for planning purposes; b) Common Energy Market (CEM), regarding aspects of interventions changed due to ongoing roll-out or evolution of the project and c) CommunityxChange (CxC), measuring the effect on public participation in energy efficiency initiatives. The evaluation framework process results in a sum of 33 KPIs. |

| STARDUST Enlightening European Cities Ref. [28] | The framework structure proposes a set of 17 indicators to monitor and assess the performance of the project solutions across five (5) diverse clusters; Building and Energy, e-Mobility, ICT, Common City Level and Long-Term Effects. The monitoring of the project is based on i) Immediate progress evaluated through concrete output indicators; ii) Achieved impacts assessed by impact indicators and iii) Long-term effects evaluated through scalability of the solutions implemented based in the LH cities, Fellow Cities and their replication potential in other cities in Europe. |

| Source | Assessment Framework |

|---|---|

| Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | Angelakoglou et al. introduce a smart city KPI framework after applying a six (6)-step approach for determining the KPI repository. The 75 KPIs identified are able to evaluate both business-as-usual and novel technologies and services related to smart city solutions. The repository is categorized into six (6) dimensions (technical, environmental, economic, social, ICT and legal KPIs) and provides indicative thresholds for monitoring performance. This framework was built upon the experiences gained during the implementation of the IRIS SCC project and integrates relevant stakeholder points of view concerning the deployment of smart city solutions. |

| Akande et al. (2019) [29] | Akande et al. propose a framework for assessing and ranking cities based on how smart and sustainable they are. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) are applied to select and cluster 32 KPIs into three (3) thematic areas: a) Economy (7 KPIs) b) Environment (12 KPIs) and c) Society and Culture (13 KPIs). KPIs included in this framework are mostly fitted to assess smartness aspects on a city level. |

| Huovila et al. (2019) [13] | Huovila et al. compare seven recently published indicator standards for smart and sustainable cities (ISO 37120:2018, ISO/DIS 37122:2018, ETSI TS 103463, ITU-T Y.4901, 4902, 4903, SDG 11+ monitoring framework). A taxonomy was developed to evaluate 413 indicators against five conceptual urban focuses (types of urban sustainability and smartness), ten sectoral application domains (energy, transport, ICT, economy, etc.) and five indicator types (input, process, output, outcome, impact). The results clearly discriminate between indicator standards suited for evaluating the implementation of predominantly smart city approaches versus standards more focused on sustainability assessment. As within this study most of the KPI frameworks identified by Huovila et al. are already examined, and emphasis was mostly on ITU-T KPIs and the taxonomy developed. |

| Tan et al. (2017) [30] | Tan et al. propose an indicator framework for the assessment of smart cities putting emphasis on low-carbon city aspects. A total of 20 KPIs are separated into seven (7) assessment categories: a) Energy pattern, b) Water, c) Social and living, d) Carbon and environment, e) Solid waste, f) Urban mobility and g) Economic. The framework also provides benchmarking values that allow intercomparisons among cities’ performance. |

| Girardi and Temporelli (2017) [31] | Girardi and Temporelli propose a new methodological approach, called Smartainability, that is able to estimate using quantitative and qualitative KPIs the extent to which smart cities are more sustainable (and smart) due to the deployment of innovative technologies. The assessment is performed prior to the application of the respective technologies. The methodology was built upon the Guidelines for conducting a cost–benefit analysis of Smart Grid projects, a study made by European Commission JRC, and Smart Cities—Ranking of European medium-sized cities, realized by Vienna University of Technology, University of Ljubljana and Delft University of Technology. Four (4) dimensions of analysis are applied: a) Environment, b) Economy, c) Energy and d) Living. The methodology was validated at a district level (Expo Milano 2015 site). Further recommendations are available for the implementation at a city level, including a set of 28 KPIs and a new dimension—People—which evaluates the community life improvement. |

| Dall’O et al. (2017) [32] | Dall’O et al. provide a method for assessing the smartness of a city through a set of indicators focusing on small and medium-sized cities and communities. The KPIs selected are consistent with the ISO 37120 standard and are inspired by the environmental indicators included in Sustainable Energy Action Plans under the Covenant of Mayors Initiative. A total of 70 KPIs are structured around seven (7) evaluation areas: a) smart economy (7 KPIs), b) smart energy (12 KPIs), c) smart environment (6 KPIs), d) smart governance (12 KPIs), e) smart living (17 KPIs), f) smart people (8 KPIs) and g) smart mobility (8 KPIs). |

| Li et al. (2017) [33] | Li et al. propose a systematic approach, utilizing a bi-index method, to identify stakeholders and KPIs for multi-level (from building to district) energy performance analysis. KPIs are analyzed into three (3) levels: strategic, tactical and operational. The strategic KPI is aggregated and designed for the district level. The tactical KPI can be associated with the building and system level. The operational KPIs represent the operational performance of basic energy units. Although this study does not focus directly on smart city projects, it offers 35 specific performance indicators that can serve the goals of smart city solutions focusing on energy performance. |

| Hara et al. (2016) [34] | Hara et al. propose a set of KPIs for smart cities based on the Gross Social Feel-Good Index. The KPIs are structured upon four (4) layers: a) the 1st layer includes the triple bottom line (Environment, Economy, Society) and Satisfaction generic categories; b) in the 2nd layer, the Society category is further split into safety, health and comfort; c) the 3rd layer includes a total of 16 KPIs utilized to assess the 2nd layer (environment/natural resource, energy, cost performance, accident, natural disaster, crime, information security, health management, prevention of illness, medical treatment, stress, diverse opportunities, barrier-free, simplicity, ubiquitous, and citizen’s degree of satisfaction) and d) the 4th layer includes the data needed (52 sub-KPIs) to calculate the KPIs in the 3rd layer. |

| Lombardi et al. (2012) [35] | Lombardi et al. introduce a framework for classifying smart city performance indicators building upon the quadruple helix model (Civil society, University, Government and Industry) and utilizing the Analytic Network Process. A total of 63 KPIs are proposed, organized into five (5) clusters: a) smart governance (related to participation)—7 KPIs, b) smart human capital (related to people)—12 KPIs; c) smart environment (related to natural resources)—19 KPIs; d) smart living (related to quality of life)—13 KPIs and e) smart economy (related to competitiveness)—12 KPIs. |

| Source / KPI Dimensions | Environmental | Economic | Technical | Social | Mobility | Governance | Propagation | ICT | Supporting | Legal | City Description | LCA | Urban Planning | Total KPIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCIS | * | * | * | * | * | * | 36 | |||||||

| CITYKeys | * | * | * | * | * | * | 101 | |||||||

| * | * | * | * | * | 76 | |||||||||

| UN’s SDGs | * | * | * | * | * | 61 | ||||||||

| U4SSC | * | * | 91 | |||||||||||

| ISO/FDIS 37122 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 52 | ||||||

| ISO/FDIS 37120 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 65 | ||||||

| ETSI | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 73 | ||||||

| IRIS | * | * | * | * | * | * | 75 | |||||||

| REPLICATE | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 56 | ||||||

| MATCHUP | * | * | * | 188 | ||||||||||

| SMARTenCITY | * | * | * | 149 | ||||||||||

| MYSMARTLIFE | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 151 | ||||||

| SHARING CITIES | * | * | * | * | * | 127 | ||||||||

| TRIANGULUM | * | * | * | * | * | 79 | ||||||||

| GROWSMARTER | * | * | * | * | 104 | |||||||||

| +CityxChange | * | * | * | * | * | 33 | ||||||||

| STARDUST | * | * | * | * | * | 17 | ||||||||

| Akande et al. (2019) | * | * | * | 32 | ||||||||||

| Huovila et al. (2019) ITU-T Y4901/ Y.4902 / Y.4903 | * | * | * | * | * | 130 | ||||||||

| Tan et al. (2017) | * | * | * | * | * | 20 | ||||||||

| Girardi and Temporelli (2017) | * | * | * | * | 28 | |||||||||

| Dall’O et al. (2017) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 70 | ||||||

| Li et al. (2017) | * | 35 | ||||||||||||

| Hara et al. (2016) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 16 | ||||||

| Lombardi et al. (2012) | * | * | * | * | 63 | |||||||||

| Total KPIs | 1928 | |||||||||||||

| KPI Dimension | Description | KPI Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | Energy performance is focusing mainly on the interventions facilitating energy transition. | Energy demand and consumption; RES generation ratio; Peak load reduction |

| Environmental | Environmental performance is increasingly important for smart cities striving to identify environmental risks and factors that are essential for humans and natural resources and special for smart city planning and operation. | CO2 emissions reduction; Air quality, Noise pollution |

| Economic | Economic performance refers to the business efficiency and cost of each application and usage scenario from a market perspective. | Average cost of energy consumption; Cost savings; Return on investment |

| ICT | ICT performance is regarded as a key pillar for technology advancements in the smart city concept, enabling data management, privacy and security and data monitoring for the development of new innovative services. | Cybersecurity; Data privacy; Improved interoperability |

| Mobility | Mobility performance is appropriate for smart city projects concerning the convergence of energy and transport sectors, the global EV market uptake and the increasing citizens’ needs for sustainable mobility and e-mobility services. | EVs charging points; Clean mobility utilization; E-vehicle sharing solutions |

| Social | Social performance is crucial to estimate the extent to which the project and its designed collaborative action model facilitate the involvement of citizens and social actors in the planning, decision-making and implementation activities through social citizen-driven innovation mechanisms. | Citizen participation in co-creation processes and online decision making; Degree of users’ satisfaction |

| Governance | Governance performance refers to the city governance from the side of the municipality administration, planning and evaluation mainly, but also includes aspects of the legal domain regarding the regulatory framework and its compatibility with the proposed solutions and implemented policies at project or city level. | Involvement of the city administration; Legal framework compatibility; New rules/regulations due to the project |

| Propagation | Propagation performance assesses the potential for wider scalability and replicability of the solutions and actions demonstrated. | Social compatibility of solutions; Market demand; Diffusion potential |

| KPI Name | KPI Unit | KPI Sources | KPI Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | |||

| E.1 Energy Demand and Consumption | kWh/(m2∙month kWh/(m2∙year) kWh/year | SCIS [17]; REPLICATE [20]; MATCHUP [21]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; Hara at al. (2016) [34]; Lombardi et al. (2012) [35]; ETSI [40]; U4SSC [37] | This indicator assesses the energy efficiency of a system for each sector of buildings, transport, industry, public services (e.g., lighting), ICT, etc., also broken down into energy sources (electricity, heating, natural gas, etc.) The energy demand and consumption correspond to the energy entering the system in order to keep operation parameters (e.g., comfort levels). |

| E.2 Degree of energetic self-supply by RES | % | SCIS [17]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; Li et al. (2017) [33]; Lombardi et al. (2012) [35]; mySMARTLIFE [23]; U4SSC [37]; SDG [36] | The degree of energetic self-supply by RES is defined as the ratio of locally produced energy from RES and the energy consumption over a period of time (e.g., month, year). |

| E.3 Self-Sufficiency Ratio | % | Luthander et al. (2015) [48] | The degree to which the on-site generation is sufficient to fill the final energy needs of the building/system. |

| E.4 Energy Savings | kWh/ (m2∙year); MWh/(year); % | SCIS [17]; mySMARTLIFE [23]; ITU-T [37]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; Li et al. (2017) [33] | This KPI determines the reduction of energy consumption to reach the same services (e.g., comfort levels) after the interventions. |

| E.5 Reduced energy curtailment of RES and DER | % | SCIS [17]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; +CityxChange [27] | The indicator assesses the reduction of energy curtailment due to technical and operational problems such as over-voltage, over-frequency, local congestion, etc. |

| E.6 kWp photovoltaic installed per 100 inhabitants | kWp/100 inhabitants | Dall’O et al. (2017) [32] | Installed capacity of photovoltaic interpolated to 100 inhabitants. |

| E.7 Smart Storage Capacity | %; MWh | Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; +CityxChange [27] | The KPI includes all the energy storage technologies integrated in the city smart grid containing electricity, heating and mobility, presenting the impact of the project on the use of smart energy storage systems. |

| E.8 Heat Recovery Ratio | % | GrowSmarter [26] | The KPI refers to the percentage ratio of the total thermal energy output of the system (MWh) to the thermal energy recovered through a waste heat recovery technology (MWh). |

| E.9 Integrated Building Management Systems (BMS) | %; [number] | U4SSC / ITU-T [37] | Percentage of buildings using integrated ICT systems to automate building management and create flexible, effective, comfortable and secure environment. |

| E.10 Percentage of buildings in the city with smart energy meters | % | ISO/FDIS 37122: 2019 [38] | Percentage of buildings using smart energy meters to record and display the consumption of energy in real time, thus providing energy providers data to better plan and conserve energy. |

| E.11 Specific Yield | W/kWp; W/m2 | SmartEnCity [22] | Metered output energy of a supply system related to the size (capacity) of the system. |

| E.12 Storage Energy Losses | % | Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; Li et al. (2017) [33] | This KPI illustrates the energy losses because of battery storage, including the added voltage transformations. |

| E.13 Thermal Load Reduction | W | Li et al. (2017) [33] | Reduction of heating/cooling load caused by envelope insulation in specific thermal zone. |

| E.14 Peak Load reduction | % | Li et al. (2017) [33] | The indicator compares the peak demand before the aggregator implementation (baseline) with the peak demand after; per final consumer, per feeder, per network. |

| E.15 Street lighting management | % | ISO/FDIS 37122: 2019 [38] | Percentage of street lighting managed by a light performance management system. |

| Environmental | |||

| EN.1 Greenhouse Gas Emissions | kgCO2eq/(m2*year); kgCO2eq/(kWh*year); % | SCIS [17]; Lombardi et al. (2012) [35]; Hara et al. (2016) [34]; MATCHUP [21]; U4SSC [37]; ETSI [40]; +CityxChange [27] | The KPI calculates the amount of emissions for six major GHGs: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6). |

| EN.2 Carbon Dioxide Emission Reduction | tons/year; tons/capita/year; % | SCIS [17]; CITYkeys [11]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; Li et al. (2017) [33]; Tan et al. (2017) [30]; Dall’O et al.(2017) [32]; IRIS [19]; SmartEnCity [22]; REPLICATE [20]; +CityxChange [27] | CO2 emissions can be considered a useful indicator to assess the contribution of urban development on climate change. The main sources are processes related to energy generation and transport. |

| EN.3 Air Quality Index | Index (no unit) of PM10, PM2.5, NOX, SO2 Ozone & Benzene. | CITYkeys [11]; MATCHUP [21]; U4SSC [37]; ETSI [40] | The indicator provides a relative measure of the annual average air quality in relation to the European limit values (annual air quality standards and objectives from EU directives). |

| EN.4 Primary Energy Demand and Consumption | kWh/(m2*month; kWh/(m2*year) | SCIS [17]; MATCHUP [21]; mySMARTLIFE [23] | The indicator of the primary energy demand/consumption of every metered system encompasses all the naturally available energy that is consumed in the supply chain of the used energy carriers. |

| EN.5 Climate Resilience Strategy | Likert Scale (1-7) | CITYkeys [11]; ETSI [40] | This indicator assesses to what extent the city has a resilience strategy and action plan to adapt/respond to climate change, by providing a qualitative measure. |

| EN.6 Noise Pollution | % | CITYkeys [11]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; Akande et al. (2019) [29]; IRIS [19]; REPLICATE [20]; MATCHUP [21]; ISO 37120: 2018 [39]; U4SSC [37]; ETSI [40]; | This KPI refers to the measurement of noise in level of decibels (dB) before and after the activities of the project. |

| EN.7 Municipal Solid Waste | tons/capita/month tons/capita/year | CITYkeys [11]; Tan et al. (2017) [30]; Dall’O et al. (2017) [32]; Hara et al. (2016) [34]; REPLICATE [20]; ISO 37120: 2018 [39]; ETSI [40] | This indicator provides a measure of how much waste a city is producing and the level of service a city is providing for its collection. |

| EN.8 Recycling Rate of Solid Waste | % | CITYkeys [11]; Tan et al. (2017) [30]; Dall’O et al. (2017) [32]; Lombardi et al. (2012) [35]; REPLICATE [20]; ISO 37120: 2018 [39]; ETSI [40]; U4SSC [37] | This KPI estimates the percentage of city’s solid waste that is recycled, calculated as the total amount of the city’s solid waste that is recycled in tons divided by the total amount of solid waste produced. |

| Economic | |||

| EC.1 Total Investments | €/m2, € (total) | SCIS [17]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; +CityxChange [27] | The KPI is defined as the number of cumulated payments relevant to the energy aspects of the systems (e.g., highly efficient envelope in a building), including also business-as-usual case investments. |

| EC.2 Total Annual Costs | €/year | SCIS [17]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The total annual costs are defined as the sum of capital-related annual costs (e.g., interests and repairs caused by the investment), requirement-related costs (e.g., power costs), operation-related costs (e.g., costs of using the installation) and other costs (e.g., insurance). |

| EC.3 Payback Period | Years | SCIS [17]; CITYkeys [11]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; +CityxChange [27] | The payback period is the time it takes to cover investment costs. It can be calculated from the number of years elapsed between the initial investment and the time at which cumulative savings offset the investment. |

| EC.4 Return on Investment (ROI) | % | SCIS [17]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; +CityxChange [27] | The return on investment (ROI) is defined as the ratio between the total incomes/net profit and the total investment of the project/product, etc. |

| EC.5 Average Electricity Price for Companies and Consumers | €/kWh | TRIANGULUM [25] | The indicator represents the average minimum cost at which electricity must be sold so as to balance the costs with profits. |

| EC.6 Percentage of the Total Distributed Energy Resources Capacity Traded | % | +CityxChange [27] | This KPI measures the amount of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) capacity traded as a percentage of the total DERs capacity available. |

| EC.7 Local Job Creation | # of jobs | CITYkeys [11]; MATCHUP [21]; +CityxChange [27]; mySMARTLIFE [23]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; | This indicator assesses the creation of direct jobs from the implementation and operation of smart city project solutions. |

| EC.8 Energy Poverty | % | CITYkeys [11]; REPLICATE [20]; ETSI [40]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The KPI evaluates the extent to which households are at risk of poverty or deprivation by calculating the change in percentage points of (gross) household income spent on energy bills. |

| EC.9 Carbon Dioxide Reduction Cost Efficiency | €/(ton CO2 saved/year) | CITYkeys [11]; mySMARTLIFE [23] Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; | The specific KPI estimates the costs in euros per ton of CO2 saved per year. This KPI can be estimated capitalizing on information already available in other KPIs (carbon dioxide emission reduction and total annual costs). |

| EC.10 New Business Creation | #/100.000 population; % | CITYkeys [11]; ETSI [40] | The indicator assesses the number of new businesses created (including start-ups) as one point of overall business climate in a jurisdiction and entrepreneurship. |

| EC.11 Expenditures by the municipality for a transition towards a smart city | €/capita; €; % | CITYkeys [11]; REPLICATE [20]; MATCHUP [21]; ETSI [40]; ITU-T [37] | Smart city expenditures include process-relevant expenditures and findings. Estimates should also include the percentage of municipal budget allocated to the ICT facilities. |

| ICT | |||

| ICT.1 Increased System Flexibility for Energy Players | %; W/€ | SCIS [17]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The indicator determines the increased system flexibility for the energy utilities as an effective way to exploit all resources to respond to a set of diversions (e.g., demand changes in a specific time interval) and maintain the power balance in terms of load or cost. |

| ICT.2 Increased hosting capacity for RES, electric vehicles and other new loads | % | SCIS [17]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The indicator determines the improvement of hosting capacity with regards to additional loads and installations in the network when R&I solutions are applied and also compared to the baseline scenario. |

| ICT.3 Improved Data Privacy | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; ETSI [40]; ITU-T [37] | This indicator refers to the level of improvement of data privacy and safety, analyzing the extent to which data collected by the project are protected, for instance, by following regulations on data protection and implementing proper procedures to protect personal or private data. |

| ICT.4 Quality of Open Data | % | Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | Percentage of data that use DCAT standards. |

| ICT.5 ICT Response Time | ms/byte; sec/byte; min/byte - Depends on the system | SmartEnCity [22]; mySMARTLIFE [23] | The response time of ICT infrastructure is related to the services developed and the payload (information exchanged) between them, applicable to the various ICT actions and services in the project. |

| ICT.6 Improved Cybersecurity | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11]; MATCHUP [21]; ETSI [40] | The indicator refers to the extent to which the project ensures cybersecurity of its systems. |

| ICT.7 Platform Downtime | Minutes / (h, d, w, m) | Angelakoglou et al. (2019) | The indicator quantifies the platform downtime per selected timeframe. |

| Mobility | |||

| M.1 Electric Vehicles & Low-Carbon Emission Vehicles deployed in the area | [number]; % | SCIS [17]; U4SSC [37]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; ISO/FDIS 37122: 2019 [38]; MATCHUP [21]; REPLICATE [20] | Number of electric vehicles (EV) and low-carbon vehicles (PHEV and hydrogen) registered in the area in relation to the total number of motorized vehicles (four and two wheels). |

| M.2 Number of EV charging stations and solar powered V2G charging stations deployed in the area | [number]; % | Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; SCIS [17]; Dall’O et al. (2017) [32]; REPLICATE [20] | Number of e-charging and V2G stations, public and private and fast chargers. The indicator refers to the following measurements: number of total stations deployed, along with their locations; e-charging stations deployed and V2G stations deployed. They could also be expressed as a percentage compared to total number of stations. |

| M.3 Annual Energy delivered by charging points | KWh/year | MATCHUP [21]; SmartEnCity [22]; mySMARTLIFE [23] | The KPI refers to the level of use of the EV charging infrastructure implemented in the city, calculating the total kWh recharged by all types of EVs during a year in the public charging stations. |

| M.4 Annual number of passengers using the new vehicles and/or infrastructure | #of passengers/year | mySMARTLIFE [23] | The level of utilization of the new vehicles or infrastructure should be expressed by the number of passengers or users traveling during a year with the new vehicles (e.g., EVs and e-buses) or on the new infrastructure deployed. |

| M.5 Shared Electric Vehicles Penetration Rate | [number]; % | mySMARTLIFE [23] | Number of e-vehicles that operate in the platform and in the community car-sharing concept. |

| M.6 Clean mobility utilization | Km; # of trips | SCIS [17]; +CityxChange [27] | The indicator assesses the number of km in clean vehicles and number of trips in clean vehicles as a means of sustainable mobility. |

| M.7 Modal Split (Passengers/Vehicles/Trips) | % of vkm; % of passenger.km; % of trips | SCIS [17] | The indicator determines the distribution of transport over the modalities of public and collective transport, private vehicles, biking and walking. |

| M.8 Yearly km of Shared Vehicles | Km/year | U4SSC [37]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The indicator assesses the yearly km made through the e-car sharing system instead of private conventional cars. |

| Social | |||

| S.1 People Reached | % | CITYkeys [11]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14]; mySMARTLIFE [23] | Percentage of people in the target group that have been reached and/or are activated by the project. |

| S.2 Connection to the existing cultural heritage | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11]; mySMARTLIFE [23] | The extent to which making a connection to the existing cultural heritage was considered in the design of the project. |

| S.3 Local community involvement in the implementation and planning phase | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The extent to which residents/users have been involved in the implementation process. |

| S.4 Degree of satisfaction | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | mySMARTLIFE [23]; Hara et al. (2016) [34] | The level of satisfaction and acceptance of people affected by the actions in the project, from a technical point of view; perceived adequateness, benefit (e.g., comfort), usefulness, ease of use and aesthetics; economic point of view; and cost, risk and benefit. |

| S.5 Percentage of citizens’ participation in online decision-making | % | MATCHUP [21]; | The indicator assesses the percentage of citizens that take part in online decision-making. |

| Governance | |||

| G.1 Online visits to the municipal open data portal | #/100 000 | ISO/FDIS 37122: 2019 [38] | Number of visits to the municipal open data portal in a year per 100,000 population. |

| G.2 Percentage of city services accessible and that can be requested online (e-Governance) | % | ISO/FDIS 37122: 2019 [38]; U4SSC [37]; Lombardi et al. (2012) [35]; Dall’O et al. (2017) [32] | The total number of city services offered to people and businesses through a centralized Internet interface compared to the total number of city services offered by the city. |

| G.3 Monitoring and evaluation | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11]; ETSI [40] | The extent to which the progress towards a smart city and compliance with requirements is being monitored and reported. |

| G.4 Legal Framework Compatibility | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The level of suitability of the legal framework for the integration of a) RES generation, b) symbiotic waste-heat, c) energy flexibility, d) private and public EV penetration and e-mobility and e) CIPs for energy management and citizen engagement; policies |

| G.5 Open government dataset | #/100,000 | MATCHUP [21]; mySMARTLIFE [23]; U4SSC [37]; ETSI [40] | The indicator measures the number of open government datasets per 100,000 inhabitants, showing how involved the local government is in building a smart city. |

| Propagation | |||

| P.1 Social compatibility | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11]; Angelakoglou et al. (2019) [14] | The extent to which the project’s solution fits with people’s “frame of mind” and does not negatively challenge people’s values or the ways they are used to do things. |

| P.2 Technical compatibility | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11] | The extent to which the smart city solution fits with the current existing technological standards/infrastructures. |

| P.3 Market demand | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11] | The extent to which there is a general market demand for the solution. An important characteristic is if the innovation meets the needs of its potential adopters. |

| P.4 Diffusion to other locations | 5-point Likert scale (No Unit) | CITYkeys [11] | The extent to which the project is copied in other cities and regions. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Angelakoglou, K.; Kourtzanidis, K.; Giourka, P.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Kantorovitch, J. From a Comprehensive Pool to a Project-Specific List of Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring the Positive Energy Transition of Smart Cities—An Experience-Based Approach. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 705-735. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3030036

Angelakoglou K, Kourtzanidis K, Giourka P, Apostolopoulos V, Nikolopoulos N, Kantorovitch J. From a Comprehensive Pool to a Project-Specific List of Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring the Positive Energy Transition of Smart Cities—An Experience-Based Approach. Smart Cities. 2020; 3(3):705-735. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleAngelakoglou, Komninos, Konstantinos Kourtzanidis, Paraskevi Giourka, Vasilis Apostolopoulos, Nikos Nikolopoulos, and Julia Kantorovitch. 2020. "From a Comprehensive Pool to a Project-Specific List of Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring the Positive Energy Transition of Smart Cities—An Experience-Based Approach" Smart Cities 3, no. 3: 705-735. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3030036

APA StyleAngelakoglou, K., Kourtzanidis, K., Giourka, P., Apostolopoulos, V., Nikolopoulos, N., & Kantorovitch, J. (2020). From a Comprehensive Pool to a Project-Specific List of Key Performance Indicators for Monitoring the Positive Energy Transition of Smart Cities—An Experience-Based Approach. Smart Cities, 3(3), 705-735. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities3030036