Abstract

Background: During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Flemish colorectal cancer (CRC) screening program (by fecal immunochemical test, FIT) was suspended and non-urgent medical procedures were discommended. This study estimates how this impacted diagnostic colonoscopy (DC) scheduling after a positive FIT and the interval between both in 2020. Methods: An online survey was sent to participants in the Flemish CRC screening program with a positive FIT but without a DC to explore the possible impact of COVID-19 on the scheduling of a DC. Self-reported survey results were complemented with objective data on DC compliance and the interval between FIT and DC. Results: In 2020, DC compliance was 4–5% lower than expected (for 3780 positive FITs no DC was performed). In February–March 2020, the median time between a positive FIT and DC significantly increased. Survey participants reported fear of COVID-19 contamination, perception to create hospital overload, delay in non-urgent medical procedures (on government advice) and not being sure a DC could be performed as contributing reasons. Conclusions: On top of a 3% lower participation, the COVID-19 pandemic further increased existing DC non-compliance and the positive FIT–DC interval. The survey confirmed the crucial role of COVID-19 in the decision not to plan a DC.

Keywords:

colorectal cancer screening; FIT; colonoscopy; mixed-methods; follow-up; compliance; COVID-19; timeliness; Flanders 1. Introduction

The Flemish colorectal cancer (CRC) screening program uses a centralized invitation procedure: invitations (with leaflet and fecal immunochemical test, FIT) are sent by the Centre for Cancer Detection, by post. Participation is free of charge. The target population receives a new invitation 24 months after their last screening (or after their last invitation for non-participants) [1]. The cost of a diagnostic colonoscopy (DC) following a positive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) screening is reimbursed by the Belgian healthcare system with a certain percentage out-of-pocket. In 2020, the uptake was 48.5% [2] (i.e., 3% below the 51.5% uptake in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic) [2], with a FIT positivity proportion of 5.7%, resulting in 20,414 participants who were advised to undergo a diagnostic colonoscopy (DC). DC compliance after a positive FIT is crucial to achieve an overall reduction in CRC incidence and mortality. In 2019, 15.5% (3868) had no DC after their positive FIT in Flanders, and 10.4% (2606) even had no follow-up whatsoever [2].

The COVID-19 pandemic affected health services worldwide. On 17 March 2020, the Belgian government implemented strict measures to counter COVID-19, including the suspension of the CRC screening program and of elective medical procedures in Flanders. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic presented in two waves: the first wave was observed between 10 March and 21 June. After an interwave period, the second wave started on 31 August, and was still ongoing by the end of 2020. The shutdown periods of the Flemish CRC screening program were from 22 March (week 12) to 23 May 2020 (week 20) and again shortly from 15 to 28 November 2020 (week 46 and 47) (week numbers based on ISO-8301 standard). The short-term impact on the screening interval and uptake of screening are reported elsewhere [3]. The largest screening intervals measured in 2020 were in the week of 7 June (28.5 months) and that of 19 December (30.3 months). Throughout the entire year 2020, the difference in mean screening interval between 2020 and 2019 was only 0.5 months. The willingness to screen (screened within 40 days after invitation) was minimally influenced by COVID-19, in total –2.6% [3]. Although the screening interval and uptake rate seem to be minimally affected in Flanders, the willingness of a participant with a positive FIT to undergo a DC might be influenced, and the time interval between a positive FIT and DC might have increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A delayed DC after a positive FIT may lead to more advanced-stage CRC at the time of diagnosis and increases CRC mortality [4,5]. Flemish data (2013–2017) also indicate that CRCs detected in FIT-positive patients without a DC within 12 months are significantly more frequently diagnosed in stage III (19.7%) and stage IV (12.2%) compared to CRCs detected in FIT-positive patients with a DC within 12 months (9.4% and 2.0%, respectively) [6]. In Flanders, the five-year relative survival rate for CRC (2014–2018) is 74.9% [7] and for stage I even 97.6%, compared to only 18.7% in stage IV [6]. These results highlight the clinical importance of a (timely) DC after a positive FIT. This study therefore estimated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the decision to plan a DC after a positive FIT and on the interval between a positive FIT and the DC during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design—Online Survey

An online survey was sent by e-mail to participants in the Flemish CRC screening program with a positive FIT between 1 November 2019 and 31 March 2020 (wave 1, a ‘pre-pandemic’ period) and between 1 April 2020 until 30 September 2020 (wave 2, a ‘pandemic’ period), for whom in the health insurance data that were available at the Belgian Cancer Registry (BCR) no follow-up DC was registered at the time of mailing (12 February 2021 and 19 October 2021, respectively). Four weeks after the first mailing, a reminder mailing was sent to the entire study population (due to the anonymous approach). The survey was based on previous research and literature and was piloted before being performed in the eligible population. All candidates were selected based on the administrative databases of the Centre for Cancer Detection (CCD). Only participants of the eligible population who had provided a valid e-mail address on their participation form (with the stool sample) received a link to the online survey. The aim of the online survey was to evaluate their perception about DC, including the possible impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on DC after a positive FIT. Response to the online survey served as informed consent. No ethical approval was needed. The online survey respondents’ anonymity was ensured throughout the study. No incentive was given. The online survey data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics software (version 27.0 for Windows). The Chi-square test was used to explore possible statistically significant associations (p-values < 0.05). The open questions in the survey were analyzed using open coding and recategorized afterwards.

2.2. Overview of the Survey Questions

The survey questions concerning COVID-19 pandemic and the impact on DC planning are given below:

| DC group and DC appointment (n = 1157 and n = 82) |

| Q1: Was the DC appointment rescheduled due to COVID-19? |

| Q2: Did the COVID-19 pandemic make you hesitate to make a DC appointment? |

| Q3: If yes in Q2: How did the COVID-19 pandemic make you hesitate to make a DC appointment? (open question) |

| DC group only (n = 1157) |

| S1: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was worried about going to the hospital for a DC. |

| S2: The extra measures taken by the hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic before and after the DC reassured me. |

| No DC group only (n = 358) |

| S3: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I was worried about going to the hospital for a DC. |

| S4: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I did not want to consult my GP to schedule a DC. |

| Q4: Did the COVID-19 pandemic prevented you to make a DC appointment? |

| Q5: If yes in Q4: How did the COVID-19 pandemic prevent you from having a DC performed? (open question) |

| Q6: Fill in—what would persuade you to do a DC? (open question) |

| Q = question, S = statement. |

2.3. CRC Screening and DC Compliance

Even if the anonymous nature of the survey prohibited direct linkage of survey results, the collaboration with the Belgian Cancer Registry (BCR) allowed to complement the self-reported survey results with objective data on the compliance to DC and the interval between positive FIT and DC. The BCR collects all anatomopathological test results as part of the early detection programs for certain cancers (cervical cancer, breast and colorectal cancer). These data allow BCR to set up a central cyto-histopathological database (CHP), an essential tool for effectively organizing and evaluating the quality of cancer screening programs. This database is regularly supplemented with relevant data on medical consumption (reimbursement only) from health insurance (IMA-AIM). The use of the national social security number as the unique identifier, to which BCR is entitled by law [8,9], allows for individual coupling of these data. Mandatory reporting of all relevant samples and their test results by pathology laboratories [10,11], in combination with compulsory health insurance for all residents, virtually eliminates selection bias in the data collected by the BCR. The participation data and screening results for the population screening in 2018, 2019 and 2020 were provided by the Centre for Cancer Detection. Those individuals with a positive FIT were identified and linked to the latest available IMA data (last update March 2022 which includes data through Q3 2021). The proportion of individuals with a positive FIT who underwent a DC as follow-up was calculated, irrespective of the time interval since the FIT date. For those in whom a DC was performed, the interval between the dates of positive FIT and of DC was calculated. In the case that a person underwent multiple DCs, the one closest after the positive FIT was taken into account.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results: Study Population and Response Rate

In total, 1597 of the 5134 invitees (31.1%) responded to the survey, of whom 875 (17.5%) responded after the reminder e-mail. The response rate was significantly higher in the first wave (33.2% vs. 27.7%, p < 0.001). Participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. The fraction of the eligible population with an e-mail address (who received the online survey) was significantly higher among younger participants (85.6% of the 50–54 years age group compared to only 63.6% in the 70+ years age group, p < 0.001) and among men 78.7% as compared to 70.7% in women (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (in absolute numbers and percentages).

Three groups can be divided according to current self-reported DC status: a group who already had a DC (72.4%), a group who reported having made an appointment (5.1%) and a group who had no DC performed or planned at the moment of the survey (22.4%). Of the group without a DC, 29% indicated in the survey they would still make a DC appointment (n = 104) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-reported DC status at the time of the survey (according to survey waves), in absolute numbers and percentages.

3.2. Survey Questions Results

Table 3 shows the results of the survey questions concerning rescheduling and hesitating to plan a DC. In the DC performed and DC appointment groups the proportion who indicated that the positive FIT (and the DC afterwards) was prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was larger in wave 1 compared to wave 2 (31.7% and 19.6%, respectively). As expected, the proportion of rescheduled DC (by decision of the hospital or the respondent) was larger in the group with a DC appointment compared to those who already had a DC. In total, about 15% reported hesitations to schedule a DC, of which most of them had only ‘a little’ hesitation. Both the proportion (25–30%) and the severity of the reported hesitations were higher in the group with a DC appointment (compared to DC already performed).

Table 3.

Survey question results of groups DC performed and DC appointment at the time of the survey (according to survey waves), in absolute numbers and percentages.

Table 4 shows results on survey statements. Among those who already had a DC the majority were not worried at all about going to the hospital for a DC (46.4% in wave 1, 51.9% in wave 2). The majority of the respondents was reassured by the measures taken in the hospital during COVID-19 (59% in wave 1 and 67% in wave 2). Respondents of wave 2 were less frequently worried to go to the hospital (S1) and more frequently reassured by the hospital measures taken during COVID-19 compared to those in wave 1 (S2) (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Survey statements results of group DC performed only at the time of the survey (according to survey waves), in absolute numbers and percentages.

For the no DC group more than 40% (43.7% in wave 1 and 41.6% in wave 2, respectively) indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic prevented them at least a little to make a DC appointment. About half of these respondents (55.3% in wave 1 and 42.7% in wave 2) were worried (agreed a little or totally with the statement) to go to the hospital due to COVID-19, and 31.7% in wave 1 and 18.8% in wave 2 did not want to consult their GP for a DC appointment (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Survey questions and statement results of the no DC group only at the time of the survey (according to survey waves), in absolute numbers and percentages.

When the no DC group was asked ‘What will motivate you to plan a DC?’ (Q6), only 8.7% (31/358) selected an answer directly linked to COVID-19: 7.8% (n = 28) reported they would perform a DC after the COVID-19 pandemic, and 0.8% (n = 3) responded they would plan a DC after being vaccinated for COVID-19. Other motivations to possibly plan a DC in the future were not linked to COVID-19.

From the entire study population (DC or not), over half of the respondents mentioned fear of a COVID-19 contamination as the reason for their hesitation to make a DC appointment. The other most important reasons that were reported were: not willing to create hospital overload and/or delays in non-urgent medical procedures based on government advice (about 15%), hospital that cancelled/prevented the DC appointment (about 8%) and not being sure a DC could be performed during the COVID-19 pandemic (about 3.5%) (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Self-reported reasons for hesitancy (group with DC or DC appointment) or non-compliance (no DC group) to plan a DC.

3.3. DC Compliance and Median Delay between Positive FIT and DC

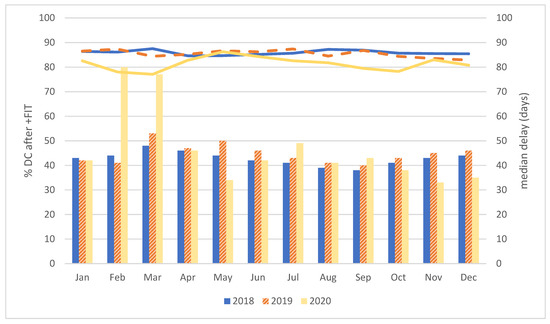

In 2020, an overall decrease by 4–5% in the DC compliance of individuals with a positive FIT was observed, as compared to the previous years 2018 and 2019. As a consequence, a positive FIT was not followed up by DC in 3780 persons (18.9% of 20,002), an estimated 900 more as compared to the previous years. Stratification by gender revealed a consistently slightly higher compliance in women, but a similar decrease in 2020. Stratification by 5-year age groups showed the highest decrease in those 55–59 years of age, followed by the oldest age group (70–74 years of age), with the latter group consistently showing the lowest compliance (data not shown). The largest difference in compliance proportions is observed in February and March 2020, and again in September and October 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of DC compliance and the median delay after a positive FIT, by year and month of the FIT. In Figure 1: lines represent the DC compliance (in %); bars represent the monthly median delay (in days).

Overall, the median time between positive FIT and DC was similar over the 3 years (43–45 days). Median delay was consistently shorter in females (2–4 days). No major differences between 5-year age groups were observed, except for a shorter median delay in the 55–59 years age group (data not shown). Figure 1 shows substantial variations in monthly median delays. For individuals with a positive FIT in February and March 2020, the median delay increased to almost 80 days. For most other months in 2020, the median delay was in line with that of previous years. However, markedly shorter median intervals were observed after positive FITs in May 2020, and again in November and December 2020.

Table 7 shows the distribution of the interval between positive FIT and DC, by calendar year, detailed per month for 2020. Overall, the DC compliance within 1 month for 2020 was in line with that of the previous years. However, the DC compliance at 1–3 months was markedly lower in 2020. Most of this additional delay shifted towards the 3–6 months range, even if the DC compliance at 6–12 months also was about 1% higher than in previous years. In the breakdown by months, it is noteworthy to mention that the lower numbers of positive FIT tests in April–May and in November–December 2020 resulted in substantially higher proportions of short intervals (within the first month and 1–3 months). Contrarily, the FITs of February–March 2020—and to a lesser extent also January 2020—had substantially larger proportions of DC after 3–6 and 6–12 months and even after >1 year.

Table 7.

Median time between positive FIT and DC: % delay.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to estimate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on scheduling a DC after a positive FIT and on the delay between a positive FIT and the DC during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 in Flanders.

In total, 78% of the survey respondents had a DC performed (73%) or had a DC appointment (5%) at the time of the survey, and 22% had not. For the DC performed and DC appointment group, 32% had to reschedule the DC (6.9% on their own decision and 25.1% on the hospital’s/physician’s decision). In addition, about 15% reported that the COVID-19 pandemic made them hesitate to schedule a DC. Of the group who had a DC performed, 29.4% were worried about going to the hospital; however, the majority (71.6%) was reassured by the measures taken in the hospital during COVID-19. In the no DC group, the COVID-19 pandemic prevented 42.7% of making a DC appointment, half (49.7%) were worried to go to the hospital and 25.9% did not even want to consult their GP to schedule a DC due to COVID-19. A part of the no DC group indicated they would still plan a DC after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, objective data are still lacking for 18.9% of FIT positives in 2020, so this answer might be linked to socially desirable answering. As the online survey indicated, the decrease in DC compliance is mostly linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. Half of the total study population (DC or not) mentioned fear of a COVID-19 contamination as the main reason for their hesitation to make a DC appointment. Other self-reported reasons were not wanting to increase the already stressed healthcare facilities, delays in non-urgent medical procedures based on government advice, hospital that cancelled/prevented the DC appointment and not being sure a DC could be performed during the COVID-19 pandemic. For some people, the need to postpone planning the DC may have led to (involuntary) failing to reschedule.

The fear of a COVID-19 contamination was mentioned by others as well. Cheng et al. (2021) indicated that the rescheduling or cancellation rate of DC in Taiwan was about 10% higher in COVID-19 times compared to the three years before, with also half of those individuals indicating fear of a COVID-19 contamination as the main reason to cancel or reschedule the DC [12]. Interviews among specialists in the UK revealed fear of a COVID-19 contamination as the most important reason not to plan a DC, and sometimes individuals were concerned about spreading COVID-19 to their family and friends or there was pressure by the family not to plan a DC [13]. A study by Rees (2020) also pointed out fear of getting COVID-19, family pressure and reluctance of traveling to the hospital while adhering to social distancing as barriers to schedule a DC [14].

A timely DC after a positive FIT is a critical step in the CRC screening continuum [4,5,6,7,15]. Flemish data previously supported the importance of a timely DC after a positive FIT [6,7]. This study indicates the DC compliance in Flanders decreased by 4–5% in COVID-19 year 2020 compared to previous years. In addition, this decrease in DC compliance was accompanied with an increase in the delay between a positive FIT and a DC to almost 80 days (versus the overall median delay of 43–45 days) in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–April 2020). Moreover, in 2020 the uptake of the Flemish CRC screening program decreased by 3% (51.5% in 2019 versus 48.5% in 2020) [2,3], which means about 22,000 less participants in the CRC screening program and about 1200 non-detected FIT positives. On top of the participants and FIT positives missed, about 900 individuals—who did participate in 2020—had a positive FIT but no DC afterwards. In the oldest age group (70–74 years), a normal median interval to DC was observed, but also a 4–5% drop in DC compliance. As this may have been the last screening round for some of these individuals, this could be clinically relevant.

A decrease in DC compliance was also observed in other CRC screening programs [16,17,18]. Corely et al. (2017) demonstrated that a DC after 10 months was associated with a higher CRC risk and more advanced-stage CRC compared to a DC at 8–30 days [4]. Modeling studies suggest that longer time to DC after a positive FIT might lead to clinically relevant increases in the risks of CRC, advanced-stage CRC and CRC mortality [15]. Zorzi et al. (2021) even indicated that the risk of dying of CRC among non-DC compliers was 103% higher than among DC compliers [5]. A number of studies indicated that an increased median interval between positive FIT and DC of more than 6–12 months could increase the risk of CRC-related mortality [19,20,21]. Based on this Flemish data, however, it is not yet possible to determine the potential clinical implications.

In Flanders, since March 2019, a fail-safe mechanism was developed. A reminder letter—shortly after the positive FIT result—is not possible due to administrative delay of registered colonoscopies (due to the lack of a central colonoscopy register). Instead, if a positive FIT is not followed by a DC (or virtual colonoscopy) the participant and GP receive—24 months after the positive FIT—a reminder recommendation to undergo a DC (instead of a new FIT invitation). Additional targeted actions to remind participants with a positive FIT, especially those during the COVID-19 pandemic, are needed. The CCD could send reminder advice with the advice to still plan a DC after the positive FIT, in which the target population needs to be reassured that a DC in hospitals can be performed safely and is still required. Research into quantifying and communicating risk and understanding how patients might be reassured regarding the safety of DC in relation to COVID-19 is needed to mitigate the collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic [22]. The UK calculated the risk of contracting COVID-19 during a colonoscopy (less than 0.5%), and although this is not zero, this low risk might help to reassure participants in a screening program to plan a DC [22].

In this study, we combined self-reported survey results from the participants to the CRC screening program with objective data on the DC compliance and time intervals between the positive FIT and the DC. This combination is an asset, because the anonymous nature of the survey prevented a direct linkage to confirm self-reported answers (e.g., on having planned a DC appointment). The study also has some limitations. Firstly, in the online survey only people for whom the CCD had a valid e-mail address could be included. Theoretically, the results of this group could differ from a group for which no valid e-mail address was provided. The online survey therefore has an under-representation of the older age categories (less e-mails provided). Men seem to be over-represented in the survey. FIT positivity rate is significantly higher and DC compliance significantly lower among men in Flanders [1,2], resulting in a larger proportion of men eligible for this study. Secondly, selection bias could also occur in the willingness to participate in the survey. People who completed the survey might be more motivated to express their motivation (not) to plan a DC. Thirdly, a potential weakness of this analysis is the availability of health insurance data. Since reimbursement of medical procedures is possible for up to two years, the health insurance data used may still be somewhat incomplete. Even if a formal analysis showed that for colonoscopies these data were >95% complete after one year (BCR, personal communication), this may slightly affect our results of both compliance and median delay, especially for the last months of 2020 and the longest intervals (>6 months after a positive FIT).

5. Conclusions

In the online survey, more than 75% of respondents reported having a DC performed or having a DC appointment after a positive FIT. Survey results confirmed the important impact of COVID-19—both by containment measures and participants’ perceptions and fears—on the willingness to plan a follow-up DC after a positive FIT. Suboptimal DC compliance after a positive FIT is an important bottleneck in the Flemish CRC screening program. This study clearly shows that the measures to counter COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic negatively affected the interval between a positive FIT and DC. COVID-19 also caused an additional 4–5% to be (un)voluntary non-compliant to follow-up DC after a positive FIT. These effects came on top of a 3% drop in uptake to the CRC screening program in Flanders. As a consequence, the CRC screening program in Flanders cannot reach its full potential impact. The combination of the decrease in uptake and DC non-compliance could contribute to a worse clinical outcome in these individuals targeted for CRC screening. Even if we cannot currently estimate these clinical consequences, these findings warrant continued monitoring of the CRC screening program and initiating additional targeted actions to increase DC compliance, in participants with a positive FIT, especially those during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. Writing—original draft preparation, S.H. and K.V.H.; writing and editing, S.H., S.J., G.V.H. and K.V.H.; statistical analysis, S.H. and S.J.; visualization, S.H. and S.J.; supervision, S.H. and K.V.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Flemish CRC screening program is funded exclusively by the Agency for Care and Health, part of the Flemish Ministry of Welfare, Public Health and Family (https://www.vlaanderen.be/en, accessed on 29 April 2022). The Flemish Ministry was not involved in any phase of this study (design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing the manuscript).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

When participating in the screening program, all participants filled out a written informed consent explaining that personal information can be used for scientific research and evaluation to improve the CRC screening programme.

Data Availability Statement

Data on screening uptake, gender and age-specific proportions of the target screening population can be requested by contacting the Centre for Cancer Detection in Flanders at https://www.bevolkingsonderzoek.be, accessed on 29 April 2022. Data on DC compliance, gender and age-specific proportions of DC compliance can be requested by contacting the Belgian Cancer Registry (BCR) at https://kankerregister.org/ [accessed both links at 29 April 2022].

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Task Force for functioning as a sounding board.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hoeck, S.; van de Veerdonk, W.; De Brabander, I. Do socioeconomic factors play a role in nonadherence to follow-up colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test in the Flemish colorectal cancer screening programme? Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 29, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Cancer Detection & Belgian Cancer Registry. Monitoring Report of the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Programme 2021. Available online: https://dikkedarmkanker.bevolkingsonderzoek.be/sites/default/files/2022-03/Jaarrapport%202021%20BVO%20naar%20kanker_0.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Jidkova, S.; Hoeck, S.; Kellen, E.; le Cessie, S.; Goossens, M.C. Flemish population-based cancer screening programs: Impact of COVID-19 related shutdown on short-term key performance indicators. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corley, D.A.; Jensen, C.D.; Quinn, V.P.; Doubeni, C.A.; Zauber, A.G.; Lee, J.K.; Schottinger, J.E.; Marks, A.R.; Zhao, W.K.; Ghai, N.R.; et al. Association Between Time to Colonoscopy After a Positive Fecal Test Result and Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. JAMA 2017, 317, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzi, M.; Battagello, J.; Selby, K.; Capodaglio, G.; Baracco, S.; Rizzato, S.; Chinellato, E.; Guzzinati, S.; Rugge, M. Non-compliance with colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Gut 2022, 71, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeck, S.; De Schutter, H.; Van Hal, G. Why do participants in the Flemish colorectal cancer screening program not undergo a diagnostic colonoscopy after a positive fecal immunochemical test? Acta Clin. Belg. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgian Cancer Register (BCR). Cancer Fact Sheet, Colorectal Cancer; ICD10: C18-20; BCR: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://kankerregister.org/media/docs/CancerFactSheets/2018/Cancer_Fact_Sheet_ColorectalCancer_2018.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Coordinated Law of 10 May 2015 Regarding the Performance of Healthcare Professions (Article 138, §2, 1°). Available online: http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=N&cn=2015051006&table_name=wet (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Law of 8 August 1983 on the Organization of a National Register; Authorization RR n° 31/2009 of 18 May 2009. Available online: https://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=N&cn=1983080836&table_name=wet (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Coordinated Law of 10 May 2015 Regarding the Performance of Healthcare Professions (Article 138, §2, 3°). Available online: http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=N&cn=2015051006&table_name=wet (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Protocol Agreement of 20 November 2017 between the Federal Government and Governments Referred to in Articles 128, 130 and 135 of the Constitution Regarding the Activities and Financing of the Cancer Registry (B. Off. J. 8 February 2018). Available online: https://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi/article_body.pl?language=nl&caller=summary&pub_date=18-02-08&numac=2017032156 (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Cheng, S.Y.; Chen, C.F.; He, H.C.; Chang, L.C.; Hsu, W.F.; Wu, M.S.; Chiu, H.M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on fecal immunochemical test screening uptake and compliance to diagnostic colonoscopy. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerrison, R.S.; Travis, E.; Dobson, C.; Whitaker, K.L.; Rees, C.J.; Duffy, S.W.; von Wagner, C. Barriers and facilitators to colonoscopy following fecal immunochemical test screening for colorectal cancer: A key informant interview study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, C.J.; Rutter, M.D.; Sharp, L.; Hayee, B.; East, J.E.; Bhandari, P.; Penman, I. COVID-19 as a barrier to attending for the U gastrointestinal endoscopy: Weighing up the risks. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 960–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, R.G.; Zauber, A.G.; Doubeni, C.A.; Jensen, C.D.; Quinn, V.P.; Helfand, M.; Dominitz, J.A.; Levin, T.R.; Corley, D.A.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I. Consequences of increasing time to colonoscopy examination after positive result from fecal colorectal cancer screening test. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vives, N.; Binefa, G.; Vidal, C.; Milà, N.; Muñoz, R.; Guardiola, V.; Rial, O.; Garcia, M. Short-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a population-based screening program for colorectal cancer in Catalonia (Spain). Prev. Med. 2022, 155, 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, E.J.A.; Goldacre, R.; Spata, E.; Mafham, M.; Finan, P.J.; Shelton, J.; Richards, M.; Spencer, K.; Emberson, J.; Hollings, S.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the detection and management of colorectal cancer in England: A population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 6, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortlever, T.L.; de Jonge, L.; Wisse, P.H.; Seriese, I.; Otto-Terlouw, P.; van Leerdam, M.E.; Spaander, M.C.; Dekker, E.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I. The national FIT-based colorectal cancer screening program in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2021, 151, 106643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, N.; Hilsden, R.J.; Martel, M.; Ruan, Y.; Dube, C.; Rostom, A.; Shorr, R.; Menard, C.; Brenner, D.R.; Barkun, A.N.; et al. Association Between Time to Colonoscopy After Posi-tive Fecal Testing and Colorectal Cancer Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzi, M.; Hassan, C.; Capodaglio, G.; Baracco, M.; Antonelli, G.; Bovo, E.; Rugge, M. Colonoscopy later than 270 days in a fecal immuno-chemical test-based population screening program is associated with higher prevalence of colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 2020, 52, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardiello, L.; Ferrari, C.; Cameletti, M.; Gaianill, F.; Buttitta, F.; Bazzoli, F.; De’Angelis, G.L.; Malesci, A.; Laghi, L. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic on Colorectal Cancer Screening Delay: Effect on Stage Shift and Increased Mortality. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayee, B.H.; East, J.; Rees, C.J.; Penman, I.J.G. Multicentre prospective study of COVID-19 transmission following outpatient GI endoscopy in the UK. Gut 2021, 70, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).