3.1. FTIR Analysis

Figure 1 presents the FTIR spectra obtained from citrus extracts at concentrations of 0.05%, 0.08%, and 0.12%

v/

v, revealed a series of characteristic absorption bands that qualitatively identify functional groups present in essential oils derived from orange peel. Across all concentrations, the spectral profiles were consistent, with the primary differences observed in band intensities, reflecting variation in the relative abundance of active compounds.

Prominent absorption bands were detected at 2918 and 2853 cm

−1, indicative of aliphatic C–H stretching, along with peaks at 1460 and 1378 cm

−1 related to aromatic C–H bending and methyl group vibrations. These spectral features are well documented as characteristic of terpenic compounds, especially limonene, the dominant constituent of citrus essential oils, as reported by Hachlafi et al. and Bhattacharyya et al. [

21,

22].

Further analysis identified lower intensity bands at 1304 and 1154 cm

−1, associated with C–O and C–O–C stretching vibrations, potentially attributable to alcohols, ethers, or esters present in minor quantities. Additionally, signals at 886 and 722 cm

−1 were observed, corresponding to out of plane =C–H bending vibrations, suggesting the presence of alkene type double bonds consistent with the unsaturated nature of limonene and other monoterpenes. These bands fall within the spectral range reported in standard FTIR libraries and are reinforced by computational and experimental analyses such as those in İşcan (2024) [

23], confirming the spectral assignments. Furthermore, comparison with FTIR spectral libraries revealed high concordance, confirming the limonene-rich composition of the extracts.

Beyond qualitative characterization, the relative band intensity was notably influenced by extract concentration, with more concentrated samples displaying greater absorption and correspondingly lower transmittance, as expected from an elevated presence of absorbent functional compounds. This trend was especially evident in the 1200–900 cm

−1 region, where spectra exhibited a more complex absorption pattern likely due to overlapping C–O, C–C and =C–H vibrations resulting in reduced resolution yet simultaneously highlighting the extract’s structural complexity. Notably, this spectral domain has been identified as highly predictive in multivariate analyses for citrus oil authentication via partial least squares regression (PLSR), for citrus oil authentication. This was confirmed by studies such as Yu et al. [

24], where PLSR was employed to analyze orange quality, indicating the utility of spectral regions rich in C–O and unsaturated bonds. These insights emphasize the analytical relevance of this spectral domain beyond basic inspection.

FTIR findings confirm that orange peel extracts contain not only limonene as a principal component but also a diverse mixture of alcohols, ethers, and carbonyl-containing compounds. This chemical complexity has important implications for their performance as natural degreasing agents and their corrosion inhibition efficacy on metallic surfaces such as 316LVM stainless steel. The spectral similarity to commercial citrus oils and reference materials reported in the literature further supports the idea that such extracts possess a consistent and identifiable chemical signature, suitable for authentication and quality control protocols. As demonstrated in recent studies (Kamil et al.; Septianissa and Chandrasari) [

25,

26], FTIR proves to be a rapid, reproducible, and non destructive technique ideally suited for evaluating such complex bio-based inhibitors.

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization

3.2.1. Polarization Curves

The polarization curve of 316LVM stainless steel exposed to the West Oxyclean

® product exhibited an electrochemical profile characteristic of materials that form stable passive layers, a behavior typically observed in physiological or clinical environments (

Figure 2). Under the naturally aerated conditions used in the experiment, dissolved oxygen acted as the main depolarizer of the corrosion process, governing the cathodic reaction through oxygen reduction and contributing to the observed passive behavior. The passive region, extending from the corrosion potential (

Ecorr) to the pitting potential (

Ep), indicates an overall passive response towards the test solution. However, the morphology of the observed hysteresis loop suggests signs of localized corrosion, particularly around an Ep value of −0.040 V vs. SCE, which may indicate a breakdown of the passive film. Similar electrochemical responses have been reported in the literature, where 316L stainless steel exhibited degradation of passivity and initiation of pitting under biofilm or aggressive ion influence, as shown by Pratikno & Titah. and Zhao et al., highlighting the critical role of surface chemistry and alloying elements in corrosion resistance [

27,

28].

Upon scanning towards more positive potentials, a pitting region is encountered, characterized by a significant increase in current while the potential remains relatively stable. This phenomenon is critical for evaluating the susceptibility of the material to localized corrosion. The moderate difference between Ecorr and Ep indicates a limited capacity of the steel to resist the onset of pitting, especially in the presence of oxidizing species such as the peroxides found in West Oxyclean®.

Subsequently, the applied potential sweep during the polarization test likely exacerbated these effects by generating potential gradients that promoted the propagation of incipient pits. Moreover, the use of a slow scan rate enabled a more accurate resolution of localized dissolution events. Overall, the combined effect of prolonged exposure to a chemically aggressive medium and the controlled polarization process created favorable conditions for the localized breakdown of the passive film and the initiation of pitting corrosion in 316LVM stainless steel [

29].

Figure 2 displays the potentiodynamic polarization curves obtained for 316LVM stainless steel exposed to varying concentrations of a citrus-based degreaser (0.05%, 0.08%, and 0.12%

v/

v). All measurements were performed within the same potential range as previous tests conducted on AISI 316 stainless steel, allowing for direct comparison of electrochemical behavior. The observed curves show characteristics of a passive region, but variations in pitting potential and current density reflect the influence of the extract’s organic compounds on corrosion resistance. These findings are in line with similar studies that analyzed the electrochemical behavior of stainless steels in the presence of natural plant-derived inhibitors, such as Deyab & Mohsen [

31], where avocado extract significantly altered the corrosion parameters. Likewise, coatings and passive layers formed under complex organic media, as explored by Cheng et al. [

32], demonstrated notable shifts in electrochemical profiles, reinforcing the applicability of biogenic solutions in metal surface protection.

It was observed that increasing the inhibitor concentration shifts the corrosion potential (Ecorr) toward more positive values and significantly reduces the corrosion current density (Icorr, inh). This shift indicates an enhancement in the system’s protective capability against general corrosion. Notably, the 0.12% formulation exhibited the lowest Icorr, inh, suggesting greater surface coverage by the inhibitor and superior protection efficiency.

In contrast, the 0.05% formulation resulted in a shift in Ecorr toward more negative values, accompanied by higher anodic current density. This behavior reflects lower inhibitory effectiveness, even exceeding the response observed in the uninhibited condition (Icorr), implying limited interaction between the inhibitor molecules and the metallic surface at this concentration.

The analysis also shows that none of the polarization curves exhibited an abrupt increase in current at more positive potentials, indicating the absence of a well-defined pitting region. All formulations produced a clearly established passive zone, with relatively stable current densities throughout the passive interval. This behavior is characteristic of efficiently inhibited systems and contrasts with commercial formulations such as West Oxyclean®, for which pitting initiation has been reported under similar conditions.

Collectively, the results demonstrate that the citrus-based formulations tested act as effective corrosion inhibitors for the stainless steel alloy under evaluation. The optimal concentration was 0.12%, as it provided the highest degree of protection, maintaining the alloy in a continuously passive state and significantly reducing the corrosion rate.

From a mechanistic perspective, the observed protective effect may be attributed to the formation of a thin organic film adhering to the metal surface, possibly enriched with terpenic compounds such as limonene. This layer likely functions as a physical barrier, hindering electron transfer and the ingress of chloride ions. Such behavior is supported by studies such as Alontseva et al. [

33], which document the influence of organic coatings and surface modifications on the electrochemical response of 316L stainless steel. Their findings reinforce the idea that adsorbed organic molecules—even at low concentrations—can alter passivity, influence the pitting potential, and affect the overall corrosion resistance of the alloy in complex environments.

It is important to note that the 0.05% concentration exhibited a negative inhibition efficiency (Ef%), which indicates a phenomenon of corrosion activation rather than protection. This behavior is attributed to the fact that such a low concentration does not provide a sufficient amount of organic compounds to form a continuous adsorbed film on the 316LVM stainless steel surface. The incomplete surface coverage generates exposed active sites and heterogeneous adsorption, promoting local destabilization of the passive layer and an increase in the anodic current density. This behavior is consistent with reports for citrus-based extracts at low concentrations, where insufficient and non-uniform surface coverage can induce activation instead of inhibition.

3.2.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

To complement the polarization results and strengthen the electrochemical validation of the inhibitor, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) was performed on 316L stainless steel exposed to different concentrations of the citrus extract, as well as to the commercial cleaner West Oxyclean

®. The Nyquist plots obtained are shown in

Figure 3.

All systems exhibited a single capacitive loop, indicating that corrosion is governed predominantly by charge-transfer processes rather than diffusion-controlled behavior. A progressive increase in the diameter of the semicircle was observed as inhibitor concentration increased, signifying higher charge-transfer resistance and thus enhanced corrosion protection. The formulation at 0.12% v/v displayed the largest semicircle, demonstrating the highest resistance to corrosion and the most effective surface protection.

Conversely, the solution containing 0.05%

v/

v produced the smallest semicircle, confirming it to be the least effective inhibiting concentration under the experimental conditions. This observation is fully consistent with the polarization data (

Table 1), where 0.05% exhibited the highest

Icorr value and the lowest protection efficiency (Ef%). Such behavior suggests limited surface coverage and reduced adsorption of the active organic species from the extract at this concentration.

The commercial cleaner West Oxyclean® also exhibited lower impedance values when compared to the 0.08% and 0.12% extract solutions, highlighting that the natural extract, at adequate concentration, provides superior protective performance.

The absence of Warburg-type diffusion features confirms an interfacial reaction mechanism, supporting the hypothesis that terpenes and flavonoids from the orange peel extract adsorb onto the metal surface forming a barrier layer that hinders electron transfer and restricts the ingress of aggressive ions.

In the Bode plot of

Figure 4 corresponding to the impedance modulus (|Z|), it can be observed that at low frequencies particularly below 10

−1 Hz the magnitude of |Z| increases markedly as the inhibitor concentration rises. This behavior is a direct indication of greater overall resistance of the system to the corrosion process, since low frequencies reflect long range phenomena associated with charge transfer processes and with the integrity of the protective film adsorbed on the metal surface. The solution containing 0.12% extract exhibited the highest impedance values, demonstrating the formation of a dense, stable and strongly adherent film capable of significantly reducing the corrosion rate. The 0.08% concentration showed an intermediate response, whereas the 0.05% extract displayed the most pronounced decline in |Z|, indicating that the film generated at this concentration is thinner, less homogeneous and less capable of hindering the migration of aggressive species. The commercial cleaner West Oxyclean

® showed moderate performance, with impedance values lower than those obtained for 0.12% and 0.08%, confirming that the natural extract is able to generate a more efficient protective barrier when used at appropriate concentrations.

The analysis of the phase angle in the Bode plot provides even more revealing information regarding the nature and quality of the protective layers formed. The systems containing 0.12% and 0.08% extract exhibit higher phase angles and, notably, an extended phase region spanning a wide frequency range. This response is typically associated with strongly capacitive behavior, characteristic of compact, homogeneous films with a low defect density. The breadth of the phase plateau indicates that the capacity of the film to store electrical charge remains stable over several decades of frequency, suggesting that the inhibitive layer displays structural continuity and chemical uniformity both indicative of efficient adsorption of the organic compounds present in the extract. Conversely, the system with 0.05% inhibitor shows a narrower, less intense phase curve shifted towards higher frequencies, which indicates the formation of a more reactive film with greater surface heterogeneity and lower electrochemical stability. This loss of capacitive character explains the poorer protection recorded in the polarization tests and corresponds to its lower charge transfer resistance.

Another key aspect identified in the Bode diagrams is the shift in the phase-angle maximum towards lower frequencies as the inhibitor concentration increases. This phenomenon is interpreted as an increase in the system’s time constant (τ = Rct·Cdl), implying that the film formed at higher concentrations acts as a more effective medium for slowing the charge discharge processes associated with corrosion. A larger time constant correlates with slower electrochemical processes, producing a scenario in which electron transport and the diffusion of aggressive species are significantly hindered by the adsorbed layer. In the case of the 0.12% extract, this shift is particularly pronounced, reinforcing the interpretation that this concentration is the most effective in promoting a strongly adherent and degradation-resistant film.

The behavior of the West Oxyclean® cleaner in the Bode plots reinforces the preceding conclusions: although it exhibits a noticeable phase angle and a response suggestive of some protective capacity, both the phase intensity and the |Z| values are consistently lower than those obtained for the more effective plant-based formulations. This indicates that the commercial product generates a less robust or less stable protective film compared with the organic layer formed by the active compounds of the citrus extract. The relative inferiority of West Oxyclean® with respect to the 0.12% and 0.08% systems aligns fully with the trend observed in the polarization tests and in the Nyquist diagrams.

The impedance spectra presented in

Figure 5 were modeled using a two time constant equivalent circuit that accounts for both the porous inhibitive film and the underlying corrosion processes. The model consists of the solution resistance (Rsoln) in series with two parallel R CPE elements. The first branch (Rpo in parallel with Cc,m) represents the porous inhibitor film, where Rpo describes the pore resistance and Cc is a constant phase element that captures the non ideal dielectric behavior of the coating. The second branch (Rcor in parallel with Ccor,n) corresponds to the corrosion interface, with Rcor representing the charge-transfer resistance and Ccor modeling the non-ideal capacitive contribution of the electrochemical double layer. This circuit was selected because the Bode plots exhibited two distinct relaxation processes, indicating that both the surface film and the corrosion reaction significantly influence the overall impedance response. A single-time-constant Randles circuit was therefore insufficient to accurately describe the system. The dual R–CPE structure enables separation of film-related processes (Rpo, Cc) from those associated with corrosion kinetics (Rcor, Ccor), providing a more physically meaningful interpretation of the protective performance of the inhibitor. The fitted electrochemical parameters obtained from this equivalent circuit are summarized in

Table 2.

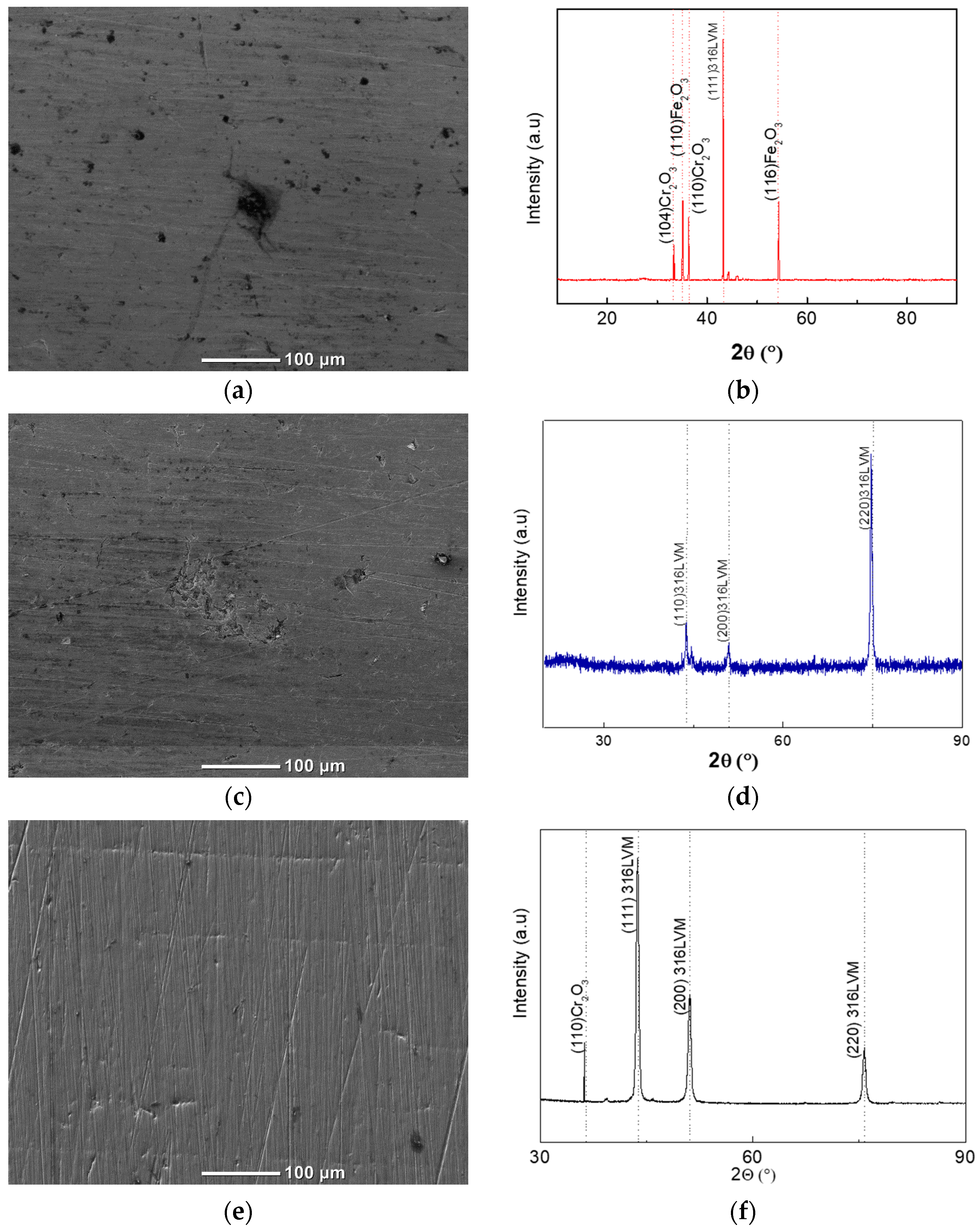

3.3. SEM and XRD

Figure 6a corresponds to a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of the polished surface of a 316LVM stainless steel specimen extracted from an unused component of a surgical device. A uniform and continuous topography is observed, characterized by parallel machining or finishing lines typical of cold-worked austenitic stainless steel. Several dark, scattered inclusions are visible, presumably nonmetallic, but none of them indicate active corrosion processes. No pitting, cracking, or accumulation of corrosion products is detected. This morphology is characteristic of an austenitic alloy in a stable passive condition, not previously exposed to aggressive environments such as physiological fluids or chemical agents. Similar results were reported by Rokosz et al. [

34], who examined long-term preserved 316LVM stent tubes and found no signs of corrosion under SEM and XPS following magneto electropolishing. The

X-Ray diffraction (XRD) pattern shown in

Figure 6b confirms the exclusive presence of the austenitic (γ) phase, a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure, consistent with JCPDS card number 33-0397 (Austenite Fe–Ni–Cr). The most intense crystallographic planes are clearly identified at (111) ≈ 43.5°, (200) ≈ 50.7°, (220) ≈ 74.2°, and (311) ≈ 90.1°. The (111) reflection exhibits the highest relative intensity, suggesting a preferred crystallographic orientation commonly observed in cold-rolled or machined steels, consistent with Shiau et al. [

35]. No secondary phases or corrosion-related oxides are detected, in agreement with previous studies on passivated 316LVM stainless steel subjected to protective surface treatments (Bukovec et al. [

36]).

Overall, the XRD findings corroborate the SEM observations, indicating that the material in its initial condition retains a well defined austenitic crystalline structure without evidence of passive film degradation or formation of secondary corrosion products.

Figure 7a presents a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of the surface of a 316LVM stainless steel specimen extracted from a previously used surgical instrument and subsequently cleaned with the commercial degreasing agent West Oxyclean

®. In contrast to the unused specimen shown in

Figure 6a, multiple dark, irregularly distributed regions are observed, which are associated with localized corrosion processes particularly pitting and the accumulation of corrosion products. These features indicate degradation of the protective passive layer, likely exacerbated by prior exposure to physiological environments and by the action of the cleaning agent. The surface topography displays a loss of homogeneity and the presence of discontinuities, suggesting the initiation of localized attack.

The

X-Ray diffraction (XRD) pattern shown in

Figure 7b reveals the coexistence of the original austenitic (γ) phase with distinct diffraction peaks corresponding to corrosion products. The γ-phase reflections remain visible, such as the (200) peak at ≈50.7°, although with noticeably reduced relative intensity compared to the unused specimen (

Figure 6b), suggesting partial loss of crystallographic integrity. Additional peaks appear at (104) ≈ 33.6°, (110) ≈ 36.2°, and (113) ≈ 52.1°, characteristic of chromium oxide (Cr

2O

3), indicating alteration of the passive film through dissolution or rearrangement of chromium-enriched regions. A low-intensity peak at (002) ≈ 60.8°, corresponding to lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH), is also identified, confirming the initiation of active oxidation processes commonly associated with pitting in physiological environments. The presence of Cr

2O

3 and γ-FeOOH is consistent with recent studies describing passive film breakdown in 316L stainless steel under microbial and high-temperature alkaline conditions (Che et al.; Wang et al.) [

37,

38].

Taken together, the SEM and XRD analyses of the specimen treated with West Oxyclean® reveal a markedly altered surface condition, characterized by clear signatures of localized pitting corrosion and passive film degradation. The diffraction pattern not only shows attenuation of the austenitic γ-phase but also the emergence of corrosion products such as Cr2O3 and γ-FeOOH, indicating a tangible disruption of the steel’s protective barrier. These combined findings demonstrate that, although West Oxyclean® typically exhibits passive electrochemical behavior, its application under certain service or exposure conditions may facilitate localized breakdown of the passive layer, thereby posing a potential risk to the long-term structural integrity of reusable surgical instruments.

Figure 8 presents the SEM microstructural evolution of 316LVM stainless steel as a function of the concentration of orange peel extract used as a natural degreasing and inhibiting agent. At the lowest concentration (0.05%), the surface exhibits a markedly heterogeneous appearance, characterized by irregularly distributed dark regions and a central zone containing a concentrated accumulation of corrosion products. These features indicate partial deterioration of the passive layer, most likely triggered by local variations in chemical composition or microstructural heterogeneities such as MnS inclusions, carbides, or mechanically induced surface discontinuities. Such heterogeneities constitute preferential adsorption and activation sites where incomplete inhibitor coverage leads to intensified local dissolution. Despite this degradation, the morphology does not exhibit deep or well defined pitting cavities, suggesting that although the extract at 0.05% is insufficient to prevent the initial breakdown of the passive film, it still provides minimal retardation of severe localized attack.

Upon increasing the extract concentration to 0.08%, the surface morphology undergoes a notable improvement. The SEM micrograph reveals a clear reduction in the density, depth, and spatial distribution of corrosion related features, accompanied by an enhanced surface uniformity and diminished accumulation of degradation products. This transition indicates that higher concentrations promote more extensive adsorption of the organic constituents of the extract including limonene, alcohols, and ether containing molecules which contribute to partial stabilization of the passive layer. The reduced presence of active anodic sites suggests that the inhibitor begins to form a more cohesive film, albeit not fully continuous, resulting in a measurable decrease in local dissolution rates. Nevertheless, fine irregularities and isolated dark zones remain visible, reflecting that protection is improved but still incomplete.

At the highest concentration (0.12%), the SEM analysis reveals a striking transformation in surface condition. The micrograph displays a nearly pristine and homogeneous morphology, with clearly preserved machining lines and an absence of corrosion products or localized surface defects. This level of morphological integrity is characteristic of a stainless steel surface that maintains a fully stable passive state. The absence of dark corroded areas or surface irregularities strongly suggests that, at this concentration, the extract components achieve complete or near complete surface coverage, forming an adsorbed hydrophobic barrier that effectively prevents chloride penetration and suppresses both uniform and localized corrosion processes. The SEM results therefore demonstrate a clear concentration-dependent trend in protection efficacy, with the 0.12% solution providing the most robust and comprehensive inhibition.

The corresponding XRD patterns (

Figure 8b,d,f) complement the SEM observations. At 0.05%, the diffraction profile shows several low to moderate-intensity peaks associated with corrosion products such as chromium oxide (Cr

2O

3) and iron oxyhydroxides (γ-FeOOH), together with a noticeable reduction in the intensity of the austenitic γ-phase reflections. This indicates passive film disruption and decreased crystallinity. At 0.08%, peaks corresponding to corrosion compounds are markedly diminished or absent, and the characteristic γ-phase reflections (111), (200), and (220) appear with enhanced intensity, suggesting partial restoration of passivity and reduced surface degradation. Finally, the specimen treated with 0.12% extract shows a diffraction pattern almost identical to that of the unused material: only the γ-phase reflections are present, with no detectable secondary oxides. This confirms full preservation of the crystalline structure and complete suppression of corrosion products at the highest inhibitor concentration.

3.4. Proposed Inhibition Mechanism

The synergistic interpretation of the electrochemical tests (Tafel polarization and EIS), the chemical characterization (FTIR), and the surface analyses (SEM and XRD) provides a coherent understanding of the inhibition mechanism exerted by the Citrus sinensis extract on 316LVM stainless steel. FTIR spectra confirmed that the extract is rich in terpenic compounds, predominantly limonene, along with alcohols, ethers and unsaturated functional groups, all of which possess adsorption-capable sites. These organic molecules exhibit both hydrophobic domains (C–H and C=C groups) and oxygenated moieties (C–O and C–O–C), enabling weak donor acceptor interactions and van der Waals forces with the metallic surface [

39].

Electrochemical polarization curves demonstrated a significant reduction in corrosion current density (

Icorr) and a shift in

Ecorr towards more noble potentials at increasing inhibitor concentrations, indicating the progressive establishment of a protective surface layer. The absence of a defined pitting region in the inhibited systems further suggests improved passivity stability [

40]. Complementary EIS measurements revealed enlarged capacitive semicircles, particularly for the 0.12%

v/

v formulation, consistent with an increase in charge transfer resistance (Rct) and thus with hindered electron transfer processes across the interface. These findings imply that the extract molecules adsorb onto the metal surface, reducing the availability of electrochemically active sites.

The SEM micrographs support this conclusion: while the 0.05% formulation exhibits dispersed areas of localized degradation and partial passive film disruption, the 0.12% concentration results in an almost pristine surface, with machining lines intact and no evidence of pitting or oxide accumulation [

18]. This morphological preservation indicates that the adsorbed organic film successfully shields the substrate from chloride penetration and inhibits the nucleation of localized corrosion sites.

XRD analysis further corroborates the proposed mechanism. Samples treated with the 0.12% extract showed exclusively the γ-austenitic phase, without the characteristic peaks of Cr2O3 or γ-FeOOH observed in both the 0.05% formulation and the commercial cleaner. The absence of crystalline corrosion products confirms that the passive layer remained intact and chemically stable under the influence of the inhibitor.