Pre-Corroded ER Sensors as Realistic Mock-Ups for Evaluating Conservation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design of Customised ER Sensors

2.1. Design Rationale: Geometry, Materials, and Fabrication Methods

2.2. Challenges Related to Pre-Patination, Thickness and Sensor Lifespan

2.3. Goal: Realistic Yet Functional and Adaptable Sensors

3. Materials and Methods

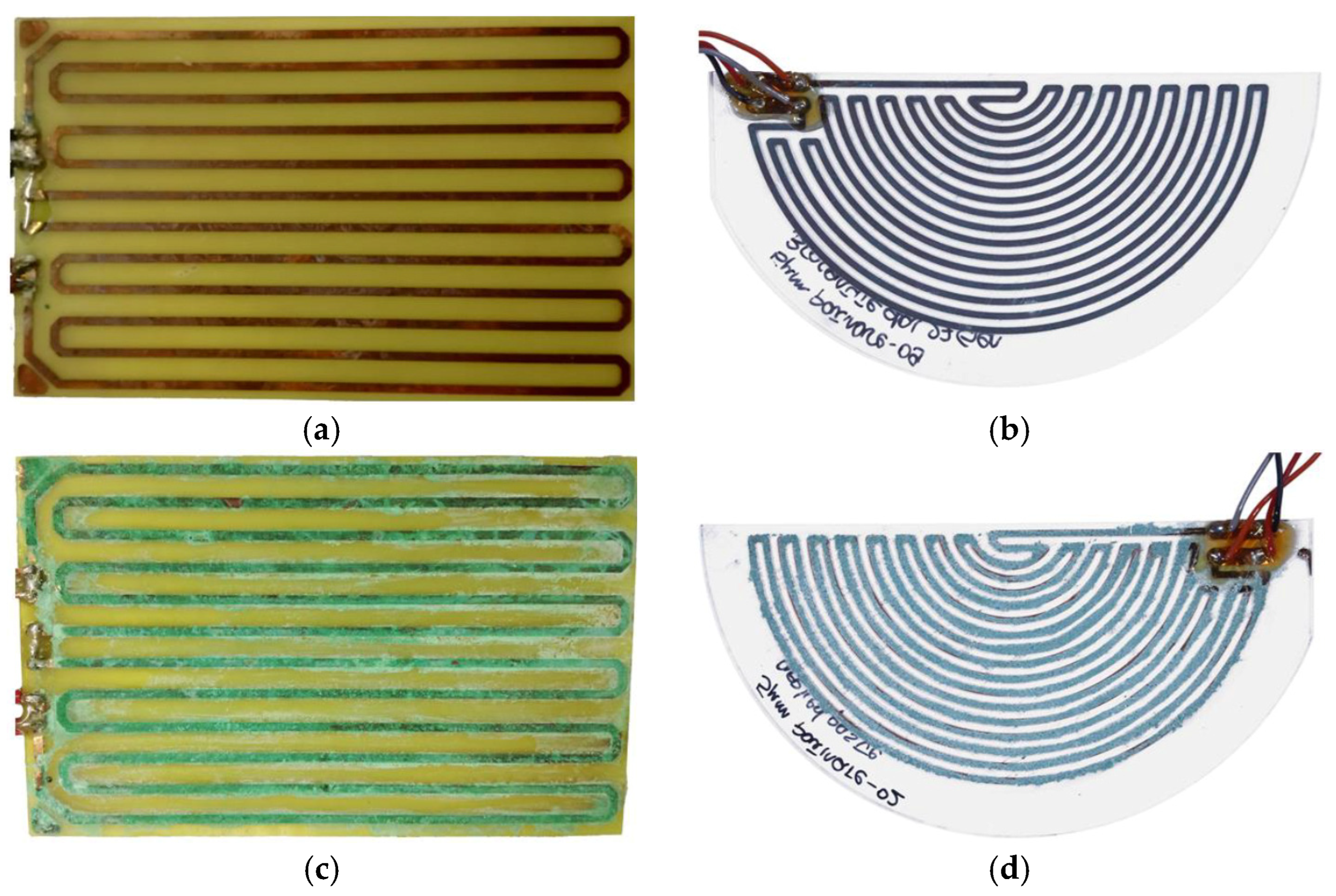

3.1. Sensor Fabrication Processes (PCB and LO Technologies)

3.2. Artificial Patination Procedures

- Cuprite (boiling solution): Immersion in a boiling solution of CuSO4·5H2O (6.25 g/L), Cu(CH3COO)2·H2O (1.25 g/L), NaCl (2 g/L), and KNO3 (1.25 g/L) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), followed by rinsing and drying and applied on PCB and LO (5 μm) sensors [90]. This procedure was selected for its capability to produce a homogeneous and adherent reddish cuprite layer, representative of the initial stages of atmospheric corrosion [89].

- “Applied paste” with chlorides and sulphates: Mixture of CuCl, CuCl2·2H2O, and CuSO4·5H2O (3:1:4) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), ground and mixed with water (1:2), applied by brush, and applied on PCB and LO (5 μm) sensors. This procedure was adapted from [90,91]. This patina was designed to simulate highly aggressive and unstable corrosion layers, typical of polluted and chloride-rich environments, and to represent a worst-case scenario for conservation testing [89].

- Brochantite patina: Immersion in a 5.4 g/L boiling solution of CuSO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h, followed by 10 wet/dry cycles in 8 g/L CuSO4 solution (2 days immersion, 2 days drying) and applied on LO (5 μm) sensors. This procedure was adapted from [92]. This method was chosen to reproduce a very common and stable sulphate-based corrosion product typically found on outdoor bronze surfaces in urban environments [89]. Surfaces were degreased with ethanol, and, during patination, masking was used to prevent conductive bridges between adjacent tracks. Monitoring was suspended during patina formation. This patina was not applied to PCB sensors due to the limited number of available monitoring channels. Given the higher sensitivity of LO sensor tracks compared to PCB sensors while considering the literature data indicating that brochantite is a relatively stable corrosion product, it was assumed reasonable to apply this patina only to the LO sensors.

3.3. Experimental Setup

3.4. ER Measurement Protocol and Temperature Compensation Strategy

4. Results

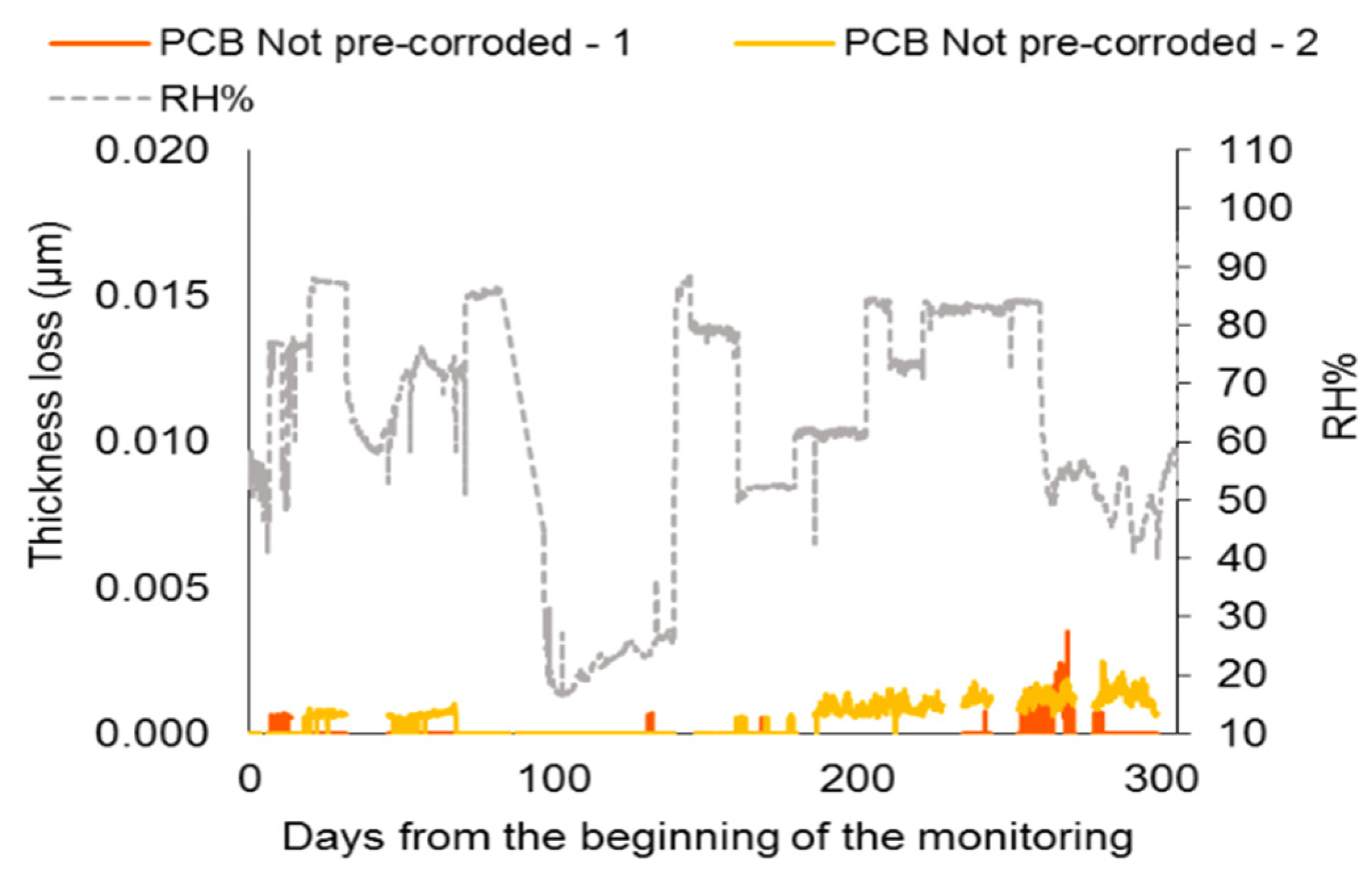

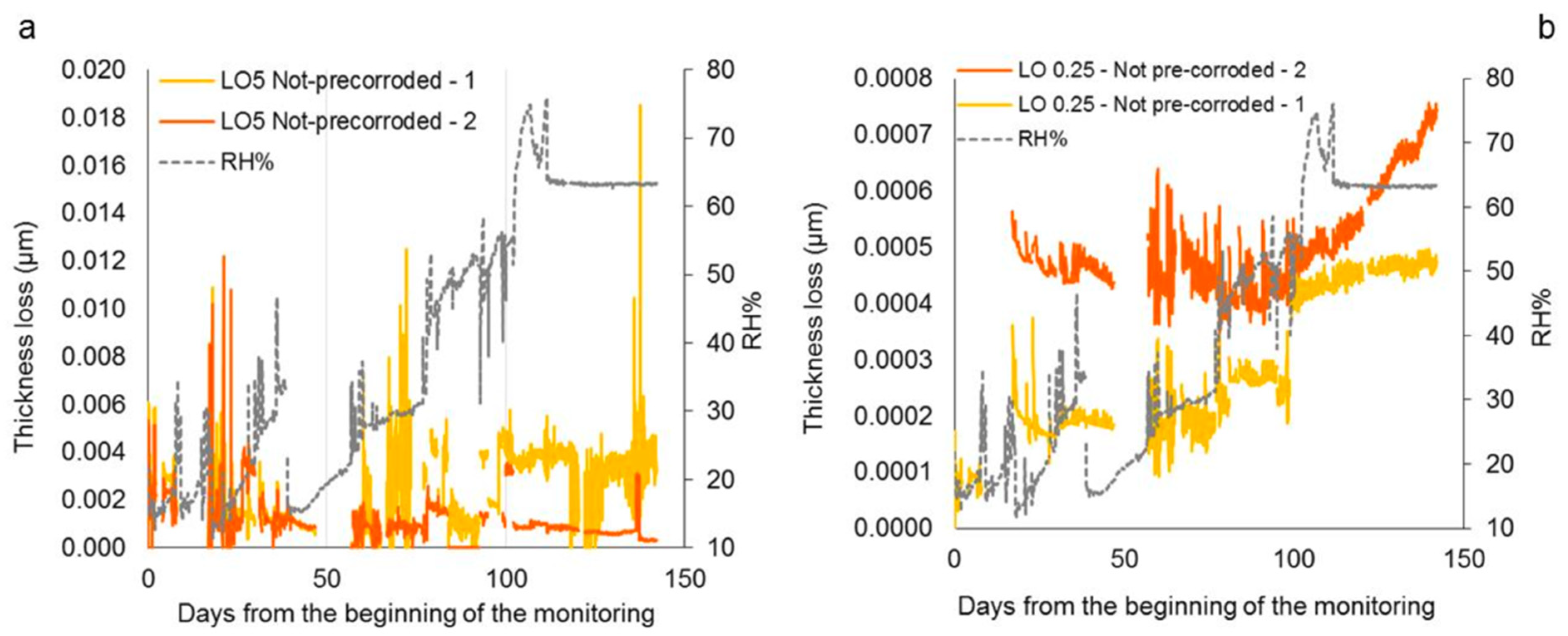

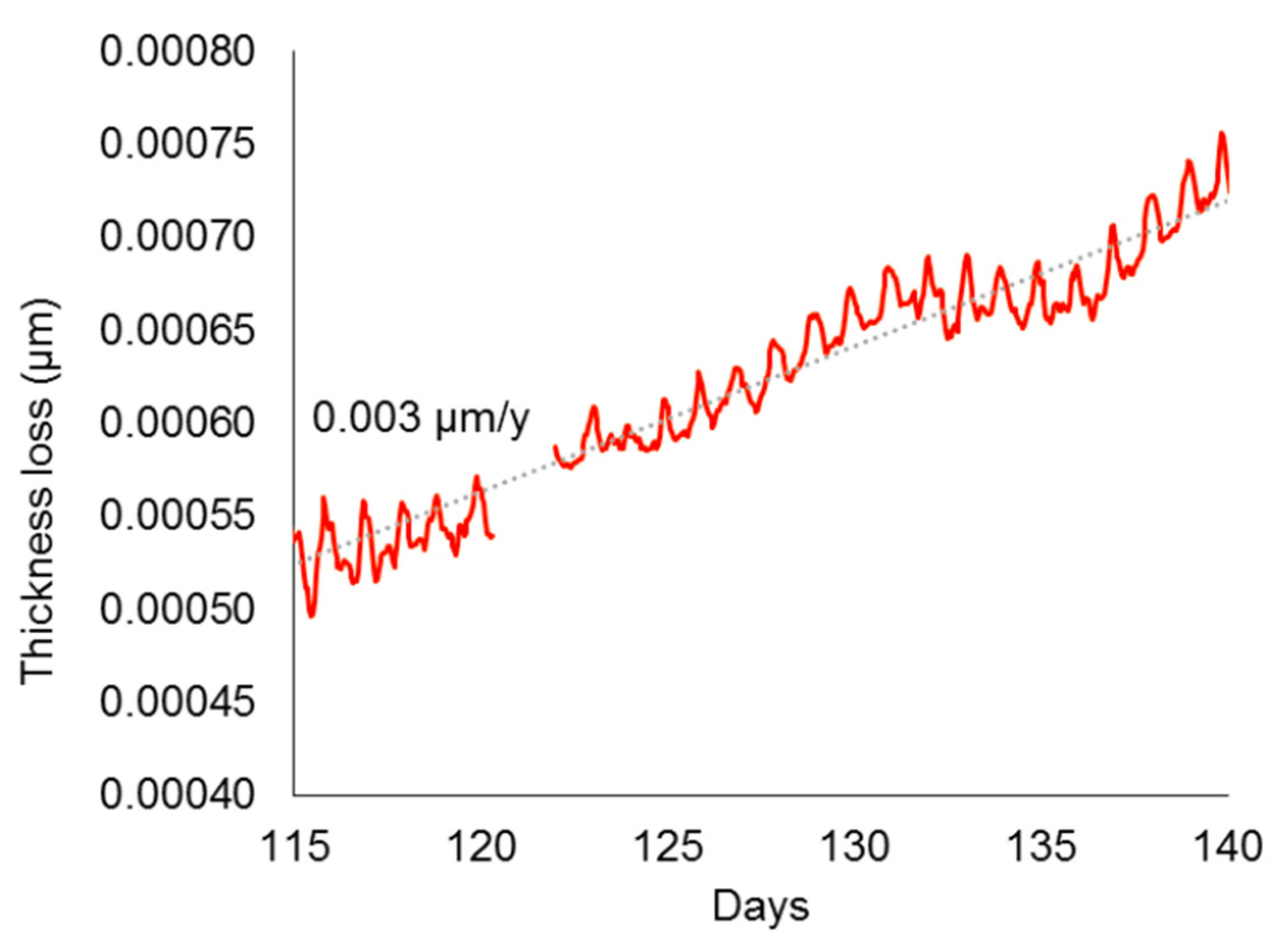

4.1. Sensor Not Subject to Pre-Corrosion

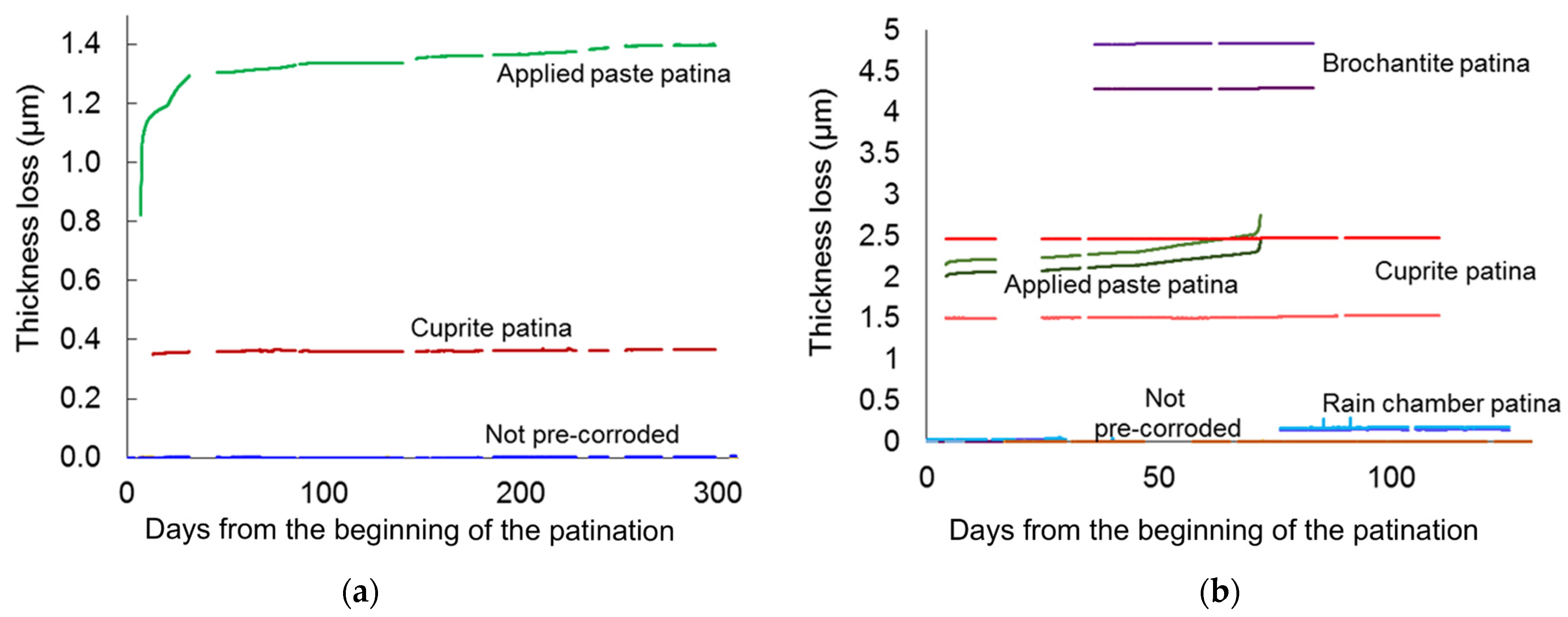

4.2. Thickness Loss Induced by Artificial Patination

4.3. Pre-Corroded Sensors with Cuprite Patina Produced by “Boiling Solution”

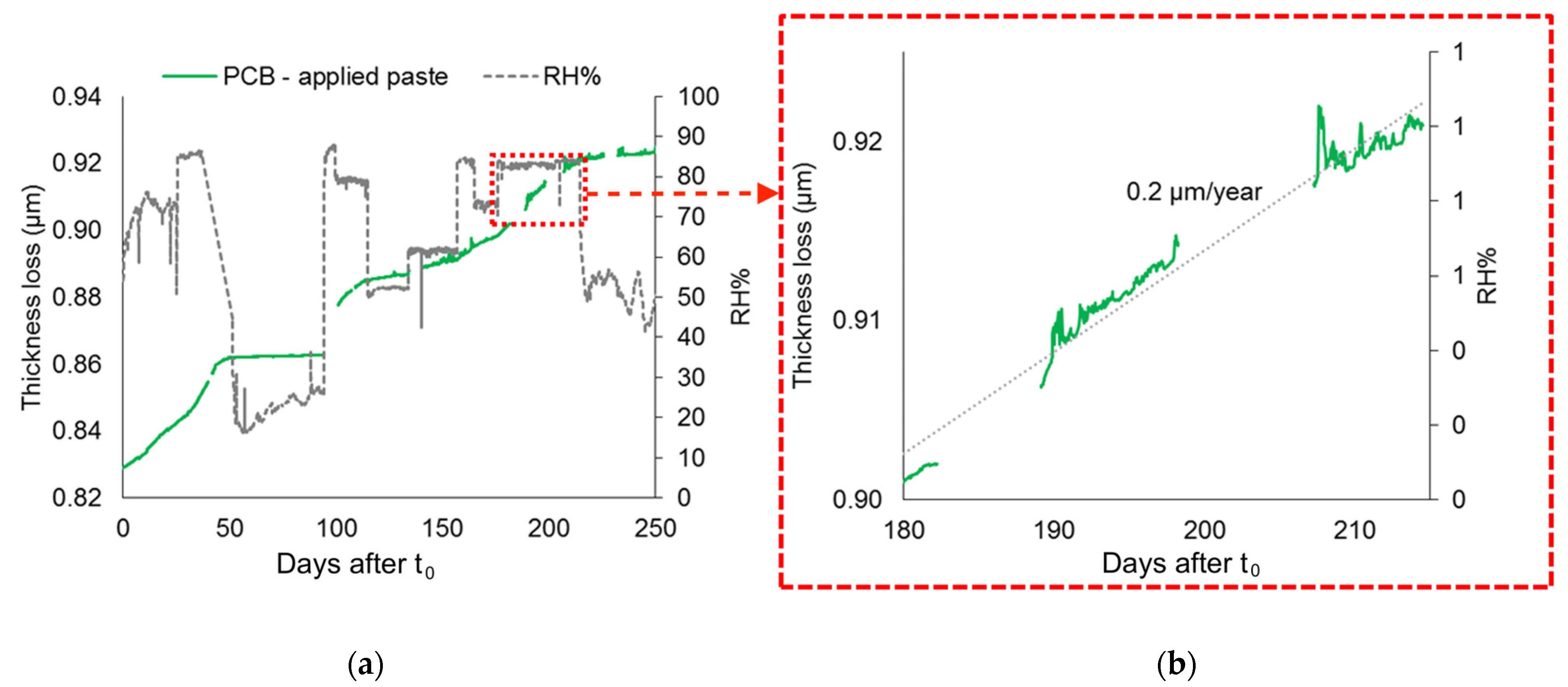

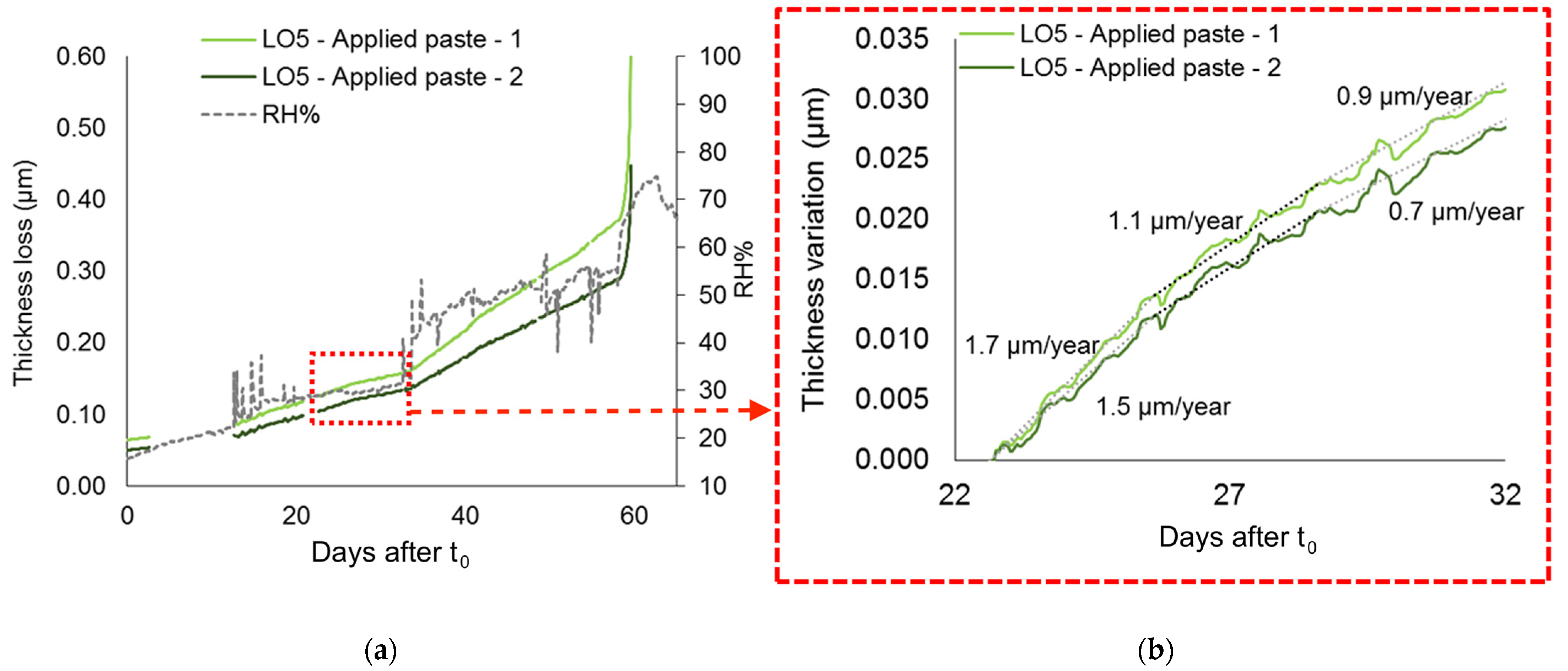

4.4. Pre-Corroded Sensors with Chloride- and Sulphate-Rich Patinas by “Applied Paste” Method

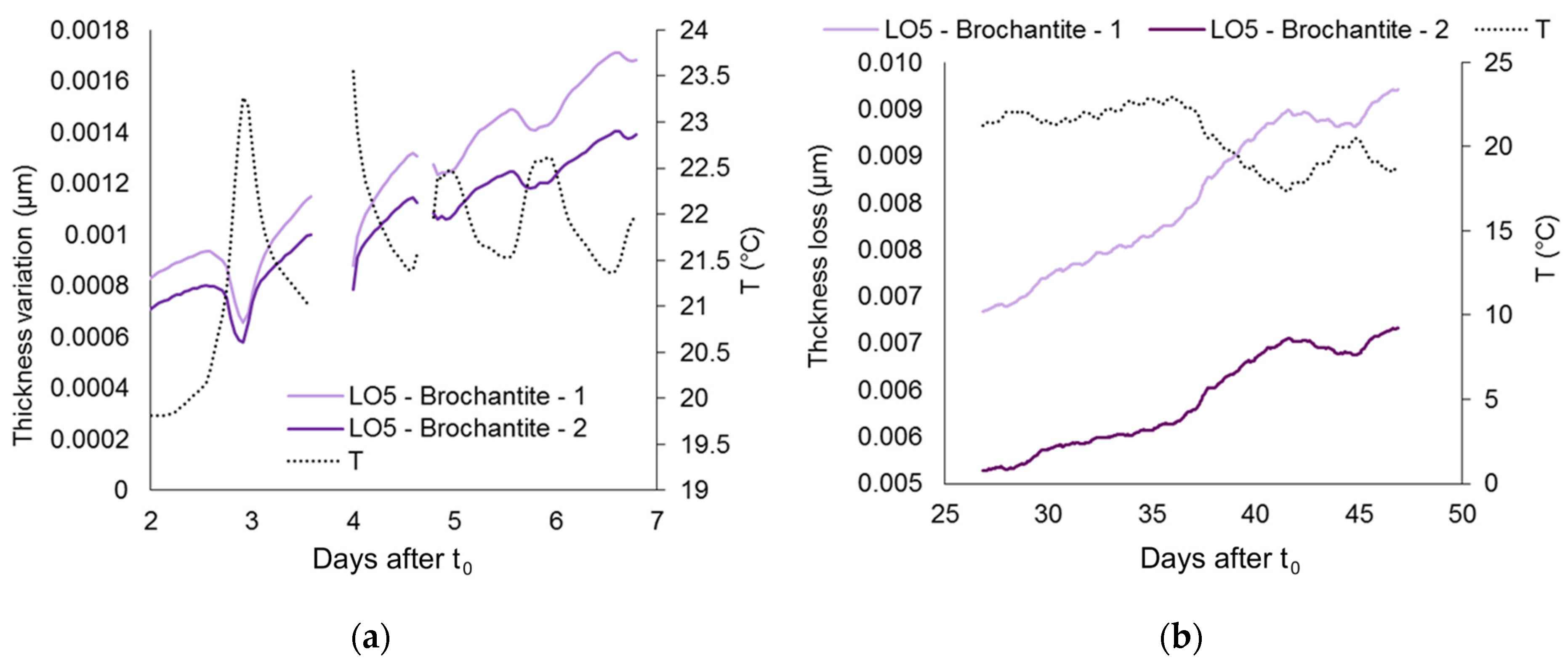

4.5. Pre-Corroded Sensors with Brochantite Patina

Temperature Compensation and Signal Artefacts

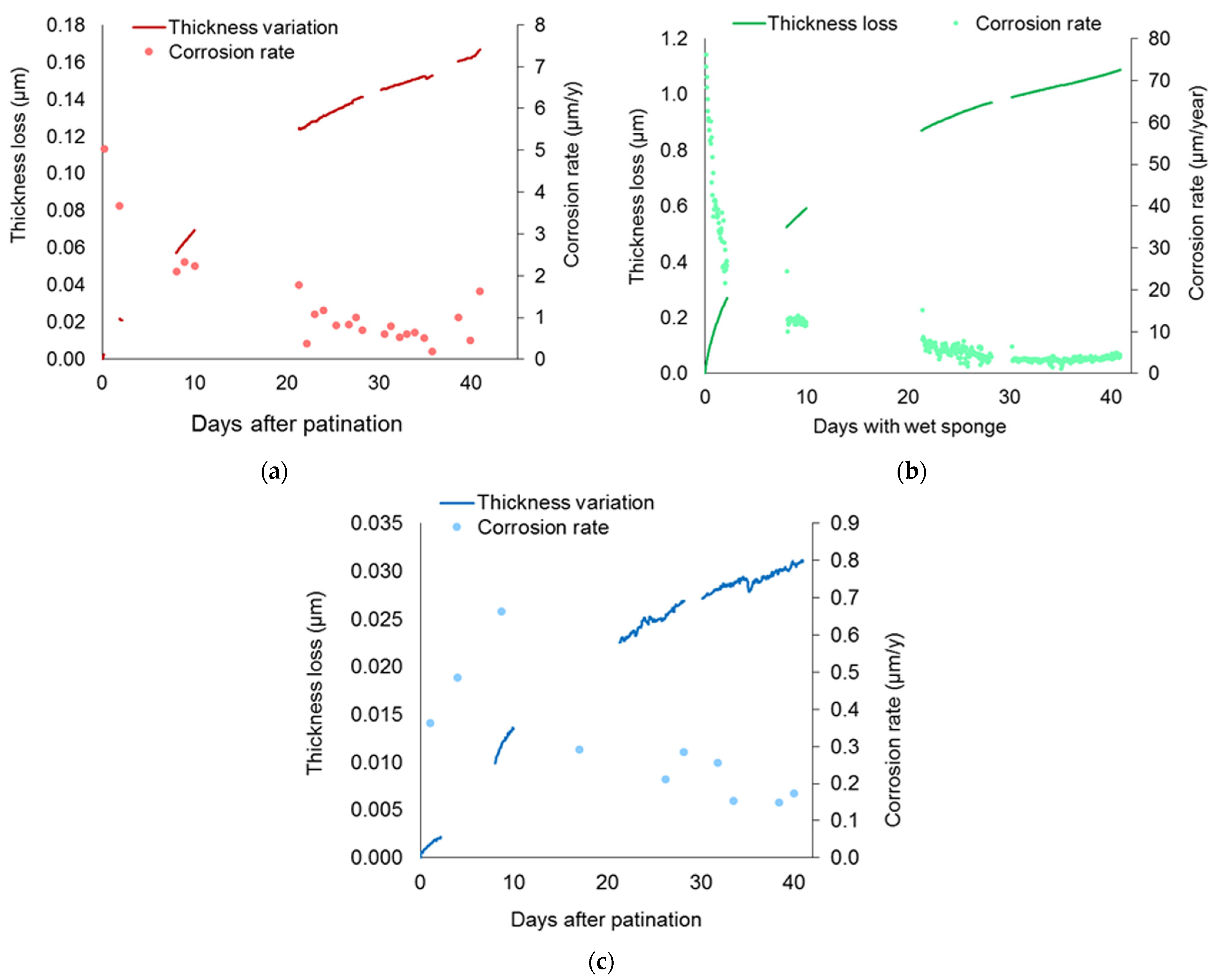

4.6. Corrosion Behaviour of Wet Surfaces: Simulation of Operating Conditions of In Situ LPR and EIS

4.7. Critical Analysis of Sensor Behaviour and Patina Effects

4.7.1. Relevance of Pre-Corroded Sensors for Conservation Applications

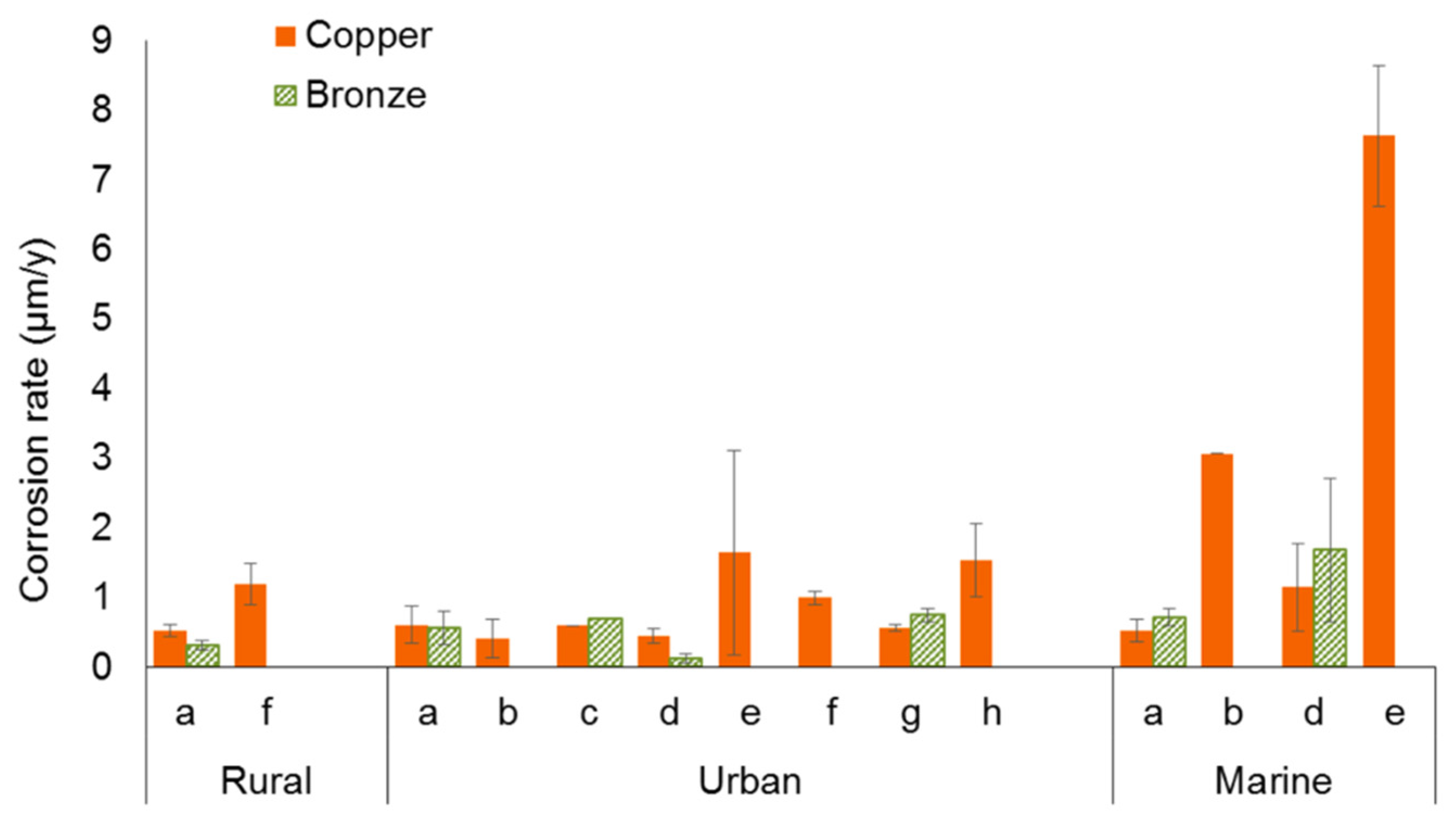

4.7.2. Sensor Response to Patinas in Light of Published Corrosion Rates

5. Discussion

5.1. Sensor Geometry and Microstructural Effects

5.2. Sensitivity and Detection Limits

5.3. Effect of Wetting and Electrolyte Application

5.4. Design Recommendations and Future Improvements

- Always locate reference and corroded tracks on the same substrate to improve temperature compensation. This is also well-aligned with the literature.

- Prioritising patina composition and morphology over alloy replication when designing mock-ups for conservation testing or ER sensors for environmental corrosivity monitoring.

- Consider the pre-corrosion of reference tracks to match thermal and electrochemical behaviour. Further research is required for this aspect.

- Refine patination procedures to reduce initial thickness loss and improve layer stability.

6. Conclusions

- Corrosion layers exert a decisive influence on corrosion rates, often outweighing the role of alloy composition.

- Pre-corroded ER sensors allow realistic and sensitive monitoring, revealing that corrosion can already be active at RH levels of 20–50% when corrosion layers contain hygroscopic and highly reactive compounds such as CuCl, as in the patina produced by the “applied paste” method. The presence of CuCl explains the persistence of corrosion even under nominally dry conditions and reflects the highly critical conservation scenarios that such stratigraphies can generate.

- Sensor design must be adapted to the intended application: PCB sensors provide robustness and longer service life, while LO sensors offer higher sensitivity but reduced stability.

- The fabrication methodology of the copper tracks plays a crucial role: LO sensors, produced by e-beam evaporation and lift-off, systematically exhibited higher corrosion rates due to their porous, defect-rich microstructure, whereas PCB sensors benefited from denser and more stable electrodeposited copper. Such microstructural effects must be considered when interpreting data from LO sensors; at the same time, a more porous structure may enhance sensitivity, even if this comes at the cost of reduced stability and increased uncertainty in corrosion rate calculations.

- Surface wetting, as applied in LPR/EIS protocols, causes an immediate and significant acceleration of corrosion, which must be taken into account when interpreting results.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ER | Electrochemical Resistance |

| ACM | Atmospheric Corrosion Monitoring |

| LPR | Linear Polarisation Resistance |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| PCB | Printed Circuit Board |

| LO | Lift-Off |

| Rc | Electrical resistance of the corroded track |

| RFID | Radio Frequency Identification |

| Rr | Electrical resistance of the reference track |

References

- Komary, M.; Komarizadehasl, S.; Tošić, N.; Segura, I.; Lozano-Galant, J.A.; Turmo, J. Low-Cost Technologies Used in Corrosion Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Barat, B.; Cano, E. In Situ Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Measurements and Their Interpretation for the Diagnostic of Metallic Cultural Heritage: A Review. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 2698–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petiti, C.; Gulotta, D.; Mariani, B.; Toniolo, L.; Goidanich, S. Optimisation of the Setup of LPR and EIS Measurements for the Onsite, Non-Invasive Study of Metallic Artefacts. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 3257–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petiti, C.; Salvadori, B.; Vettori, S.; Welter, J.; Guzmán García Lascurain, P.; Toniolo, L.; Goidanich, S. The Effect of Exposure Condition on the Composition of the Corrosion Layers of the San Carlone of Arona. Heritage 2023, 6, 7531–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petiti, C.; Martini, C.; Chiavari, C.; Vettori, S.; Welter, J.M.; Guzmán García Lascurain, P.; Goidanich, S. The San Carlo Colossus: An Insight into the Mild Galvanic Coupling between Wrought Iron and Copper. Materials 2023, 16, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S.; Corbellini, S.; Parvis, M.; Angelini, E.; Zucchi, F. A Simple Arduino-Based EIS System for in Situ Corrosion Monitoring of Metallic Works of Art. Measurement 2018, 114, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsener, B.; Alter, M.; Lombardo, T.; Ledergerber, M.; Wörle, M.; Cocco, F.; Fantauzzi, M.; Palomba, S.; Rossi, A. A Non-Destructive in-Situ Approach to Monitor Corrosion inside Historical Brass Wind Instruments. Microchem. J. 2015, 124, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letardi, P.; Salvadori, B.; Galeotti, M.; Cagnini, A.; Porcinai, S.; Santagostino Barbone, A.; Sansonetti, A. An in Situ Multi-Analytical Approach in the Restoration of Bronze Artefacts. Microchem. J. 2016, 125, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, W.; Odnevall, I.; Pan, J.; Leygraf, C. Determination of Instantaneous Corrosion Rates of Copper from Naturally Patinated Copper during Continuous Rain Events. Corros. Sci. 2002, 44, 2131–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Barat, B.; Cano, E. Agar versus Agarose Gelled Electrolyte for In Situ Corrosion Studies on Metallic Cultural Heritage. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 2553–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartuli, C.; Cigna, R.; Fumei, O. Prediction of Durability for Outdoor Exposed Bronzes: Estimation of the Corrosivity of the Atmospheric Environment of the Capitoline Hill in Rome. Stud. Conserv. 1999, 44, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petiti, C.; Toniolo, L.; Gulotta, D.; Mariani, B.; Goidanich, S. Effects of Cleaning Procedures on the Long-Term Corrosion Behavior of Bronze Artifacts of the Cultural Heritage in Outdoor Environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 13081–13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.T.; Cano, E.; Ramírez-Barat, B. Protective Coatings for Metallic Heritage Conservation: A Review. J. Cult. Herit. 2023, 62, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicileo, G.P.; Crespo, M.A.; Rosales, B.M. Comparative Study of Patinas Formed on Statuary Alloys by Means of Electrochemical and Surface Analysis Techniques. Corros. Sci. 2004, 46, 929–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Bastidas, D.; Argyropoulos, V.; Fajardo, S.; Siatou, A.; Bastidas, J.; Degrigny, C. Electrochemical Characterization of Organic Coatings for Protection of Historic Steel Artefacts. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2009, 14, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulotta, D.; Mariani, B.; Guerrini, E.; Trasatti, S.; Letardi, P.; Rosetti, L.; Toniolo, L.; Goidanich, S. “Mi Fuma Il Cervello” Self-Portrait Series of Alighiero Boetti: Evaluation of a Conservation and Maintenance Strategy Based on Sacrificial Coatings. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letardi, P. Outdoor Bronze Protective Coatings: Characterisation by a New Contact-Probe Electrochemical Impedance Measurements Technique. In Proceedings of the Paper Presented at the the Science of Art, Bressanone, Italy, 26 February–1 March 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, E.; Lafuente, D.; Bastidas, D.M. Use of EIS for the Evaluation of the Protective Properties of Coatings for Metallic Cultural Heritage: A Review. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2010, 14, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, E.; Letardi, P.; Mazzeo, R.; Prati, S.; Vandini, M. Innovative Treatments for the Protection of Outdoor Bronze Monuments. In Proceedings of the Metal 07, Interim meeting of the ICOM-CC Metal WG, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 17–21 September 2007; ICOM: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Letardi, P.; Spiniello, R. Characterisation of Bronze Corrosion and Protection by Contact-Probe Electrochemical Impedance Measurements. In Proceedings of the Metal 01—Proceedings of the International conference on Metals Conservation, Santiago, Chile, 2–6 April 2001; Western Australian Museum: Santiago, Chile, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino, J.; Gassa, L. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Study of Cuprous Oxide Films Formed on Copper: Effect of PH and Sulfate and Carbonate Ions. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2003, 7, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Pyun, S.-I. Assessment of Corrosion Resistance of Surface-Coated Galvanized Steel by Analysis of the AC Impedance Spectra Measured on the Salt-Spray-Tested Specimen. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2007, 11, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, B.; Cagnini, A.; Galeotti, M.; Porcinai, S.; Goidanich, S.; Vicenzo, A.; Celi, C.; Frediani, P.; Rosi, L.; Frediani, M.; et al. Traditional and Innovative Protective Coatings for Outdoor Bronze: Application and Performance Comparison. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavari, C.; Bernardi, E.; Martini, C.; Passarini, F.; Ospitali, F.; Robbiola, L. The Atmospheric Corrosion of Quaternary Bronzes: The Action of Stagnant Rain Water. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 3002–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosec, T.; Škrlep, L.; Švara Fabjan, E.; Sever Škapin, A.; Masi, G.; Bernardi, E.; Chiavari, C.; Josse, C.; Esvan, J.; Robbiola, L. Development of Multi-Component Fluoropolymer Based Coating on Simulated Outdoor Patina on Quaternary Bronze. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 131, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wallinder, I.O.; Leygraf, C. A comparison between corrosion rates and runoff rates from new and aged copper and zinc as roofing material. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2001, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albini, M.; Chiavari, C.; Bernardi, E.; Martini, C.; Mathys, L.; Joseph, E. Evaluation of the Performances of a Biological Treatment on Tin-Enriched Bronze. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, L.; Bernardi, E.; Chiavari, C.; Brunoro, G. Corrosion of 85-5-5-5 Bronze in Natural and Synthetic Acid Rain. Appl. Phys. A 2004, 79, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, G.; Esvan, J.; Josse, C.; Chiavari, C.; Bernardi, E.; Martini, C.; Bignozzi, M.C.; Gartner, N.; Kosec, T.; Robbiola, L. Characterization of Typical Patinas Simulating Bronze Corrosion in Outdoor Conditions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 200, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Pászti, Z.; de Melo, H.; Aoki, I. Chemical Characterization and Anticorrosion Properties of Corrosion Products Formed on Pure Copper in Synthetic Rainwater of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Aoki, I.; Tribollet, B.; de Melo, H. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Investigation of the Electrochemical Behaviour of Copper Coated with Artificial Patina Layers and Submitted to Wet and Dry Cycles. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 2801–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Gennusa, M.; Rizzo, G.; Scaccianoce, G.; Nicoletti, F. Control of Indoor Environments in Heritage Buildings: Experimental Measurements in an Old Italian Museum and Proposal of a Methodology. J. Cult. Herit. 2005, 6, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryhl-Svendsen, M. Corrosivity Measurements of Indoor Museum Environments Using Lead Coupons as Dosimeters. J. Cult. Herit. 2008, 9, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, D.; Vega, J.; Viejo, F.; Díaz, I.; Morcillo, M. Mapping Air Pollution Effects on Atmospheric Degradation of Cultural Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thickett, D.; Chisholm, R.; Lankester, P. Reactivity Monitoring of Atmospheres. In Proceedings of the Metal 2013—Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metal Working Group, Edinburgh, Scotland, 16–20 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ingo, G.M.; Angelini, E.; Riccucci, C.; De caro, T.; Mezzi, A.; Faraldi, F.; Caschera, D.; Giuliani, C.; Di Carlo, G. Indoor Environmental Corrosion of Ag-Based Alloys in the Egyptian Museum (Cairo, Egypt). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 326, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, M.; Vassie, P.R. Use of Weight Loss Coupons and Electrical Resistance Probes in Atmospheric Corrosion Tests. Br. Corros. J. 1985, 20, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, K.; Prošek, T. Corrosion Monitoring in Atmospheric Conditions: A Review. Metals 2022, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dracott, J. Piezoelectric Printing and Pre-Corrosion: Electrical Resistance Corrosion Monitors for the Conservation of Heritage Iron. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Purwasih, N.; Kasai, N.; Okazaki, S.; Kihira, H.; Kuriyama, Y. Atmospheric Corrosion Sensor Based on Strain Measurement with an Active Dummy Circuit Method in Experiment with Corrosion Products. Metals 2019, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouril, M.; Scheffel, B.; Degres, Y. Corrosion Monitoring in Archives by the Electrical Resistance Technique. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouril, M.; Scheffel, B.; Dubois, F. High-Sensitivity Electrical Resistance Sensors for Indoor Corrosion Monitoring. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosek, M.; Kouril, M.; Hilbert, L.; Degres, Y.; Blazek, V.; Thierry, D.; Østergaard Hansen, M. Real Time Corrosion Monitoring in Atmosphere Using Automated Battery Driven Corrosion Loggers. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, L.; Lebozec, N. On-Line Corrosion Monitoring of Indoor Atmospheres. In Corrosion of Metallic Heritage Artefacts: Investigation, Conservation and Prediction of Long Term Behaviour; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2007; pp. 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubus, M.; Kouril, M.; Nguyen, T.-P.; Saheb, M.; Tate, J. Monitoring Copper and Silver Corrosion in Different Museum Environments by Electrical Resistance Measurement. Stud. Conserv. 2010, 55, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbota, H.; Mitchell, J.E.; Odlyha, M.; Strlič, M. Remote Assessment of Cultural Heritage Environments with Wireless Sensor Array Networks. Sensors 2014, 14, 8779–8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikata, A.; Zhu, Q.; Tada, E. Long-Term Monitoring of Atmospheric Corrosion at Weathering Steel Bridges by an Electrochemical Impedance Method. Corros. Sci. 2014, 87, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitanda, I.; Okumura, A.; Itagaki, M.; Watanabe, K.; Asano, Y. Screen-Printed Atmospheric Corrosion Monitoring Sensor Based on Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 139, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, D.; Suzuki, S.; Fujita, S.; Hara, N. Corrosion Monitoring and Materials Selection for Automotive Environments by Using Atmospheric Corrosion Monitor (ACM) Sensor. Corros. Sci. 2014, 83, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kim, Y.-G.; Jung, S.; Song, H.-S. Application of Steel Thin Film Electrical Resistance Sensor for in Situ Corrosion Monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 120, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, R.; Giuliani, L.; Gusmano, G. Continuous Corrosion Monitoring in Desalination Plants. Desalination 1985, 55, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, J.; Darowicki, K.; Mikołajski, S. Multi-Sensor Monitoring of the Corrosion Rate and the Assessment of the Efficiency of a Corrosion Inhibitor in Utility Water Installations. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 181, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Sun, G.; Hong, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Ou, J. Remote Corrosion Monitoring of the RC Structures Using the Electrochemical Wireless Energy-Harvesting Sensors and Networks. NDT E Int. 2011, 44, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Qin, D.; Zou, Y.; Liu, Z. Research and Development of Corrosion Monitoring Sensor for Bridge Cable Using Electrical Resistance Probes Technique. Measurement 2024, 237, 115178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hren, M.; Kosec, T.; Lindgren, M.; Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Legat, A. Sensor Development for Corrosion Monitoring of Stainless Steels in H2SO4 Solutions. Sensors 2021, 21, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosec, T.; Kranjc, A.; Rosborg, B.; Legat, A. Post Examination of Copper ER Sensors Exposed to Bentonite. J. Nucl. Mater. 2015, 459, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.Z.; Meng, L.D.; Cao, X.K.; Zhang, X.X.; Dong, Z.H. Investigation on the Initial Atmospheric Corrosion of Mild Steel in a Simulated Environment of Industrial Coastland by Thin Electrical Resistance and Electrochemical Sensors. Corros. Sci. 2022, 204, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosek, M.; Kouril, M.; Dubus, M.; Taube, M.; Hubert, V.; Scheffel, B.; Degres, Y.; Jouannic, M.; Thierry, D. Real-Time Monitoring of Indoor Air Corrosivity in Cultural Heritage Institutions with Metallic Electrical Resistance Sensors. Stud. Conserv. 2013, 58, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeyama, M. High-Temporal-Resolution Corrosion Monitoring in Fluctuating-Temperature Environments with an Improved Electrical Resistance Sensor. Sensors 2025, 25, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WAN, S.; LIAO, B.; DONG, Z.; GUO, X. Comparative Investigation on Copper Atmospheric Corrosion by Electrochemical Impedance and Electrical Resistance Sensors. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 3024–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Rahimi, E.; Van den Steen, N.; Terryn, H.; Mol, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, Y. Monitoring Atmospheric Corrosion under Multi-Droplet Conditions by Electrical Resistance Sensor Measurement. Corros. Sci. 2024, 236, 112271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, K.; Montemor, M.F.; Prošek, T. Application of Resistometric Sensors for Real-Time Corrosion Monitoring of Coated Materials. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2024, 5, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, K.; Prošek, T.; Šefl, V.; Šedivý, M.; Kouřil, M.; Reiser, M. Application of Flexible Resistometric Sensors for Real-time Corrosion Monitoring under Insulation. Mater. Corros. 2024, 75, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goidanich, S.; Gulotta, D.; Brambilla, L.; Beltrami, R.; Fermo, P.; Toniolo, L. Setup of Galvanic Sensors for the Monitoring of Gilded Bronzes. Sensors 2014, 14, 7066–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandrini, G. On the Conservation of the Baptistery Doors in Florence. Stud. Conserv. 1979, 24, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, B.; Pedeferri, P.; Re, G. Effectiveness of Some Inhibitors on the Atmospheric Corrosion of Gold Plated Bronzes. In Proceedings of the 4th European Symposium on Corrosion Inhibitors, Ferrara, Italy, 15–19 September 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, B. Behaviour of a Galvanic Cell Simulating the Atmospheric Corrosion Conditions of Gold Plated Bronzes. Corros. Sci. 1977, 17, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-S.; Kim, J.-G.; Yang, S.J. A Galvanic Sensor for Monitoring the Corrosion Damage of Buried Pipelines: Part 2—Correlation of Sensor Output to Actual Corrosion Damage of Pipeline in Soil and Tap Water Environments. Corrosion 2006, 62, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y. Experimental Study on Rebar Corrosion Using the Galvanic Sensor Combined with the Electronic Resistance Technique. Sensors 2016, 16, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Mei, H.; Wang, L. Corrosion Measurement of the Atmospheric Environment Using Galvanic Cell Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Xia, C.; Zhang, D.; Li, X. Understanding Environmental Impacts on Initial Atmospheric Corrosion Based on Corrosion Monitoring Sensors. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 64, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhi, Y.; Yang, T.; Jin, L.; Fu, D.; Cheng, X.; Terryn, H.A.; Mol, J.M.C.; Li, X. Towards Understanding and Prediction of Atmospheric Corrosion of an Fe/Cu Corrosion Sensor via Machine Learning. Corros. Sci. 2020, 170, 108697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Fu, D.; Zhou, X.; Yang, T.; Zhi, Y.; Pei, Z.; Zhang, D.; Shao, L. Data Mining to Online Galvanic Current of Zinc/Copper Internet Atmospheric Corrosion Monitor. Corros. Sci. 2018, 133, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, R. Electrochemical Sensors for Monitoring the Corrosion Conditions of Reinforced Concrete Structures: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Z.-T.; Choi, Y.-S.; Kim, J.-G.; Chung, L. Development of a Galvanic Sensor System for Detecting the Corrosion Damage of the Steel Embedded in Concrete Structure. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1814–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-H.; Park, Z.-T.; Kim, J.-G.; Chung, L. Development of a Galvanic Sensor System for Detecting the Corrosion Damage of the Steel Embedded in Concrete Structures: Part 1. Laboratory Tests to Correlate Galvanic Current with Actual Damage. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 2057–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsten, C.; Odlyha, M.; Jakiela, S.; Slater, J.; Cavicchioli, A.; de Faria, D.; Niklasson, A.; Svensson, J.-E.; Bratasz, Ł.; Camuffo, D.; et al. Sensor System for Detection of Harmful Environments for Pipe Organs (SENSORGAN). E-Preserv. Sci. 2010, 7, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- El Masri, I.; Lescop, B.; Talbot, P.; Nguyen Vien, G.; Becker, J.; Thierry, D.; Rioual, S. Development of a RFID sensitive tag dedicated to the monitoring of the environmental corrosiveness for indoor applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 322, 128602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioual, S.; Lescop, B.; Pellé, J.; Radicchi, G.D.A.; Chaumat, G.; Bruni, M.D.; Becker, J.; Thierry, D. Monitoring of the Environmental Corrosivity in Museums by RFID Sensors: Application to Pollution Emitted by Archeological Woods. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soodmand, S.; Zhao, A.; Tian, G.Y. UHF RFID system for wirelessly detection of corrosion based on resonance frequency shift in forward interrogation power. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 2018, 12, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Wireless Corrosion Monitoring Sensors Based on Electromagnetic Interference Shielding of RFID Transponders. Corrosion 2020, 76, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN ISO 11844-1:2020; Corrosion of metals and alloys–Classification of low corrosivity of indoor atmospheres–Determination and estimation of indoor corrosivity 2020. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2020.

- Yang, L. Techniques for Corrosion Monitoring; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, England, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dubus, M. Standardized Assessment of Cultural Heritage Environment by Electrical Resistance Measurement. E-Preserv. Sci. 2012, 9, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lebozec, N.; Thierry, D. Application of Automated Corrosion Sensors for Monitoring the Rate of Corrosion during Accelerated Corrosion Tests. Mater. Corros. 2014, 65, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leygraf, C.; Odnevall, I.W.; Tidblad, J.; Graedel, T. Atmospheric Corrosion, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald, K.; Nairn, J.; Skennerton, G.; Atrens, A. Atmospheric Corrosion of Copper and the Colour, Structure and Composition of Natural Patinas on Copper. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 2480–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckle, B. Report No. 23 UN/ECE—Corrosion Attack on Copper and Cast Bronze; Evaluation after 8 Years of Exposure, in International Co-Operative Programme on Effects on Materials, Including Historic and Cultural Monuments; Bavarian State Conservation Office: München, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Petiti, C.; Toniolo, L.; Berti, L.; Goidanich, S. Artistic and Laboratory Patinas on Copper and Bronze Surfaces. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Rowe, M. The Colouring, Bronzing and Patination of Metals: A Manual for the Fine Metal-Worker and Sculptor: Cast Bronze, Cast Brass, Copper and Copper Plate, Gilding Metal, Sheet Yellow Brass, Silver and Silver-Plate; Thames and Hudson Ltd.: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, L. Multianalytical Approach for the Study of Bronze and Gilded Bronze Artefacts. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Milan, Milan, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo, G.; Giuliani, C.; Riccucci, C.; Pascucci, M.; Messina, E.; Fierro, G.; Lavorgna, M.; Ingo, G.M. Artificial Patina Formation onto Copper-Based Alloys: Chloride and Sulphate Induced Corrosion Processes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 421, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli-Orlando, F.; Angst, U. Monitoring corrosion rates with ER-probes—A critical assessment based on experiments and numerical modelling. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faifer, M.; Goidanich, S.; Laurano, C.; Petiti, C.; Toscani, S.; Zanoni, M. Laboratory Measurement System for Pre-Corroded Sensors Devoted to Metallic Artwork Monitoring. Acta Imeko 2021, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J.A. Influence of Apparatus Geometry and Deposition Conditions on the Structure and Topography of Thick Sputtered Coatings. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 1974, 11, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadias, G.; Simonot, L.; Colin, J.J.; Michel, A.; Camelio, S.; Babonneau, D. Volmer-Weber Growth Stages of Polycrystalline Metal Films Probed by in Situ and Real-Time Optical Diagnostics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 183105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.; Yoon, S.; Yoo, B. The Self-Annealing Phenomenon of Electrodeposited Nano-Twin Copper with High Defect Density. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1056596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Shan, C.-H.; Huang, C.; Wu, Y.-P.; Lia, Y.-K.; Chen, W.-J. Study of Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Electrodeposited Cu on Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cells. Metals 2023, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Song, N.; Chen, M.; Tang, Y.; Fan, X. Electrodeposition, Microstructure and Characterization of High-Strength, Low-Roughness Copper Foils with Polyethylene Glycol Additives. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 38268–38278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoury, M.; Mille, B.; Severin-Fabiani, T.; Robbiola, L.; Refregiers, M.; Jarrige, J.F.; Bertrand, L. High spatial dynamics-photoluminescence imaging reveals the metallurgy of the earliest lost-wax cast object. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guériau, P.; Bellato, M.; King, A.; Robbiola, L.; Thoury, M.; Baillon, M.; Fossé, C.; Cohen, S.X.; Moulhérat, C.; et al. Synchrotron-Based Phase Mapping in Corroded Metals: Insights from Early Copper-Base Artifacts. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goidanich, S.; Toniolo, L.; Matera, D.; Salvadori, B.; Porcinai, S.; Cagnini, A.; Giusti, A.M.; Boddi, R.; Mencaglia, A.A.; Siano, S. Corrosion Evaluation of Ghiberti’s “Porta Del Paradiso” in Three Display Environments. In Proceedings of the Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metal Working Group, Metal 2010, Charleston, SC, USA, 11–15 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- BS EN ISO 9223:2012; Corrosion of Metals and Alloys–Corrosivity of Atmospheres–Classification, Determination and Estimation 2012. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2012.

- Odnevall Wallinder, I.; Leygraf, C. A Study of Copper Runoff in an Urban Atmosphere. Corros. Sci. 1997, 39, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana Rodríguez, J.; Hernández, F.J.; González, J. The Effect of Environmental and Meteorological Variables on Atmospheric Corrosion of Carbon Steel, Copper, Zinc and Aluminium in a Limited Geographic Zone with Different Types of Environment. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Herting, G.; Goidanich, S.; Sánchez Amaya, J.M.; Arenas, M.A.; Le Bozec, N.; Jin, Y.; Leygraf, C.; Odnevall Wallinder, I. The Role of Sn on the Long-Term Atmospheric Corrosion of Binary Cu-Sn Bronze Alloys in Architecture. Corros. Sci. 2019, 149, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosetti, L. In-Situ Non-Destructive Monitoring Techniques And Protective Coatings For Copper Alloys Artefacts Of Cultural Heritage. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tidblad, J.; Graedel, T.E. Gildes Model Studies of Aqueous Chemistry. III. Initial SO2-Induced Atmospheric Corrosion of Copper. Corros. Sci. 1996, 38, 2201–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odnevall, I.; Leygraf, C. Seasonal Variations in Corrosion Rate and Runoff Rate of Copper Roofs in an Urban and a Rural Atmospheric Environment. Corros. Sci. 2001, 43, 2379–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| LPR | Accurate corrosion rate; direct measurement | Requires electrolyte; discontinuous; sensitive to setup |

| EIS | Detailed coating evaluation; non-destructive | Complex data interpretation; electrolyte needed |

| Galvanic Sensors | Robust; suitable for outdoor use | May accelerate corrosion; limited sensor lifespan; data interpretation issues |

| Coupons | Standardised; easy to analyse | No real-time data; long exposure times required |

| Electrochemical Noise (EN) | Detects localised corrosion; in situ | Complex interpretation; sensitive to noise |

| Passive RFID | Low-cost, contactless, flexibility | Sensitive to temperature and reading position |

| ER Sensors | Real-time; non-invasive; sensitive; low-cost; easy to interpret | Temperature-dependent; less effective for non-uniform corrosion |

| Patina | Sensor Type | Patination Details | t0—Start of Post-Stabilisation Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cuprite (boiling) | PCB | Day 0–1 (single immersion in boiling solution) | Day 14 |

| Cuprite (boiling) | LO | Day 0–1 | Day 5 |

| Applied paste | PCB | First layer: Day 0; Second layer: Day 20 | Day 45 |

| Applied paste | LO | First layer: Day 0; Second layer: Day 20 | Day 5 |

| Brochantite | LO | Day 0 (immersion in boiling solution + wet/dry cycles) | Day 35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petiti, C.; Faifer, M.; Todua, I.; Toscani, S.; Henriquez, J.J.H.; Goidanich, S. Pre-Corroded ER Sensors as Realistic Mock-Ups for Evaluating Conservation Strategies. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040066

Petiti C, Faifer M, Todua I, Toscani S, Henriquez JJH, Goidanich S. Pre-Corroded ER Sensors as Realistic Mock-Ups for Evaluating Conservation Strategies. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2025; 6(4):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040066

Chicago/Turabian StylePetiti, Chiara, Marco Faifer, Irena Todua, Sergio Toscani, Jaime J. H. Henriquez, and Sara Goidanich. 2025. "Pre-Corroded ER Sensors as Realistic Mock-Ups for Evaluating Conservation Strategies" Corrosion and Materials Degradation 6, no. 4: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040066

APA StylePetiti, C., Faifer, M., Todua, I., Toscani, S., Henriquez, J. J. H., & Goidanich, S. (2025). Pre-Corroded ER Sensors as Realistic Mock-Ups for Evaluating Conservation Strategies. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 6(4), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040066