Aging Investigation of Polyethylene-Coated Underground Steel Pipelines

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Excavation and assessment using laboratory testing methods of polymer coating properties, such as adhesion strength of the coating to the steel pipe, mechanical properties, specific electrical resistance, cathodic disbondment, etc. [28,29,30,31]. This approach has limited practical applicability because it neglects coating damage (discontinuities) and their impact on the coating’s average specific electrical resistance. Consequently, the selected approach should be based on above-ground indirect inspection methods that evaluate the degree of polymer coating damage, including the number of defects, their specific defect ratio, and their distribution along the pipeline. The galvanic relationship between the examined pipeline section and the overall network should not affect the selected inspection methods.

- Determination of coating aging by current demand based on coating breakdown factors, defined as the current density ratio required to polarize a coated steel surface compared to a bare steel surface, aimed to determine the pipeline’s cathodic protection current consumption over various service times. Numerous studies and several leading international standards have been proposed, with defined threshold values [32,33,34,35]. Therefore, this direction is of less interest from an innovative research perspective.

- Determination of coating aging by coating average specific electrical resistance, which, according to two international standards [36,37], provides a methodology and criteria concerning the average specific electrical resistance (conductance) of newly buried polymer-coated steel pipelines and for predicting their durability over time. The above international standards specify threshold values (criteria) only for the specific electrical resistance (conductance) of newly polymer-coated pipelines [36,37], with no definite criteria or prediction methodology for assessing aging behavior over time. The latter standard [37] includes a single requirement: the insulation resistance for all types of coatings shall not decrease by more than three times after 10 years and by more than eight times after 20 years of operation.

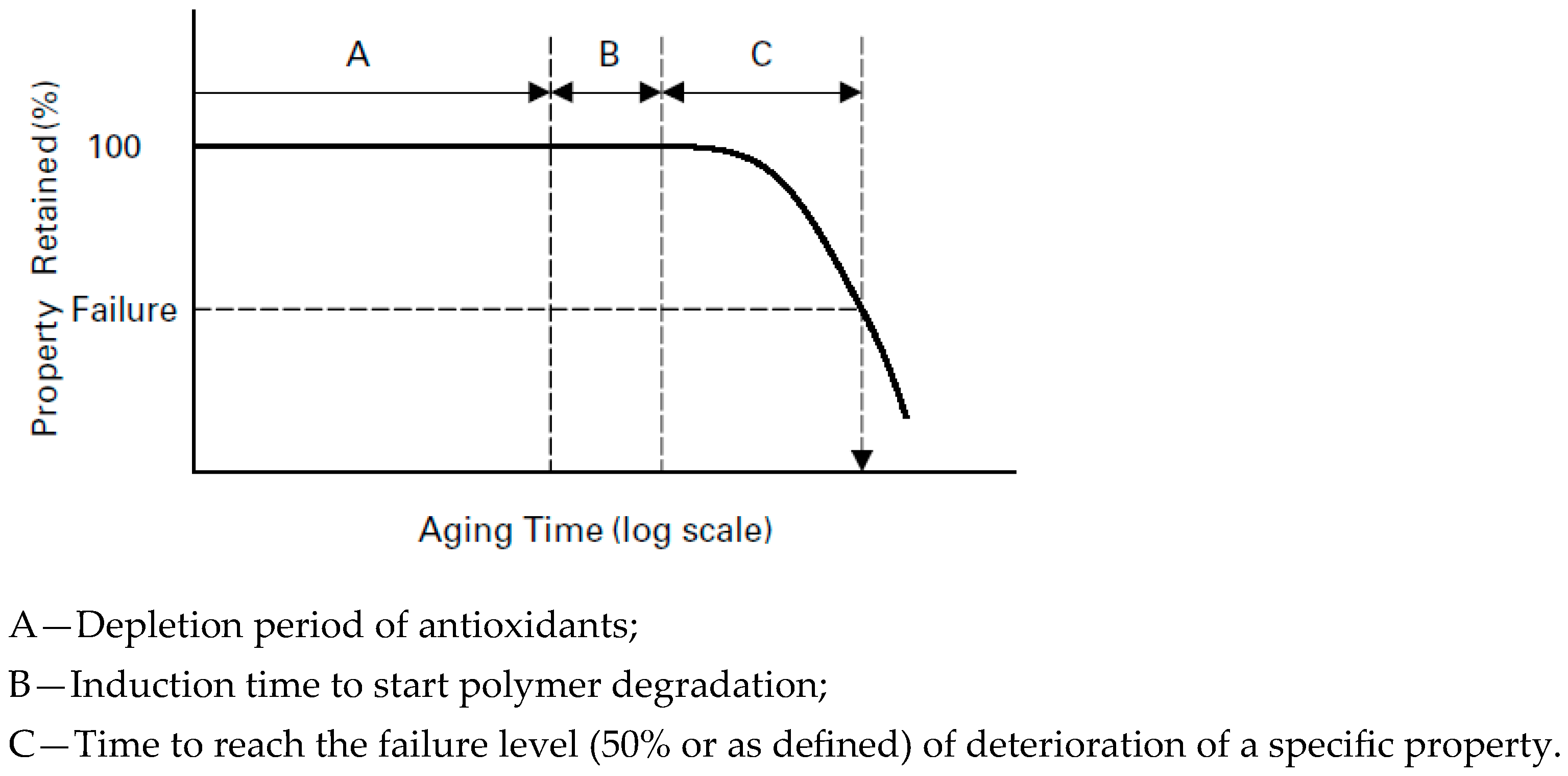

2. Degradation Mechanisms of Polyethylene

3. Experimental Procedure

3.1. General

- Polyethylene-coated pipeline sections with high initial average specific electrical resistance exceeding 106 Ohm·m2.

- Pipeline segments preferably electrically separated from the pipeline network by insulating joints or pipeline ends with no continuation (or connection to other pipelines). In both cases, the electrical current is zero. Such a method makes it possible to isolate inspection zones from interference of cathodic protection currents present in the pipeline network, incorporating autonomous inspection capabilities, comparison of different inspection methods, and precise validation.

- Selected pipeline sections with diverse technical characteristics (age, length, diameter, type and soil resistance, vicinity with high-voltage AC power lines (161/400 kV), etc.)

- Selected pipeline sections monitored over three or more consecutive years (the research duration). This has allowed us to determine the aging rates of the polymer coating, compare the methods, and conclude on a suitable and reliable inspection method.

- The oldest oil/gas and water pipelines with Drainage Test results of average specific electrical coating resistances that were tested in this study were 11 years old (from 2014).

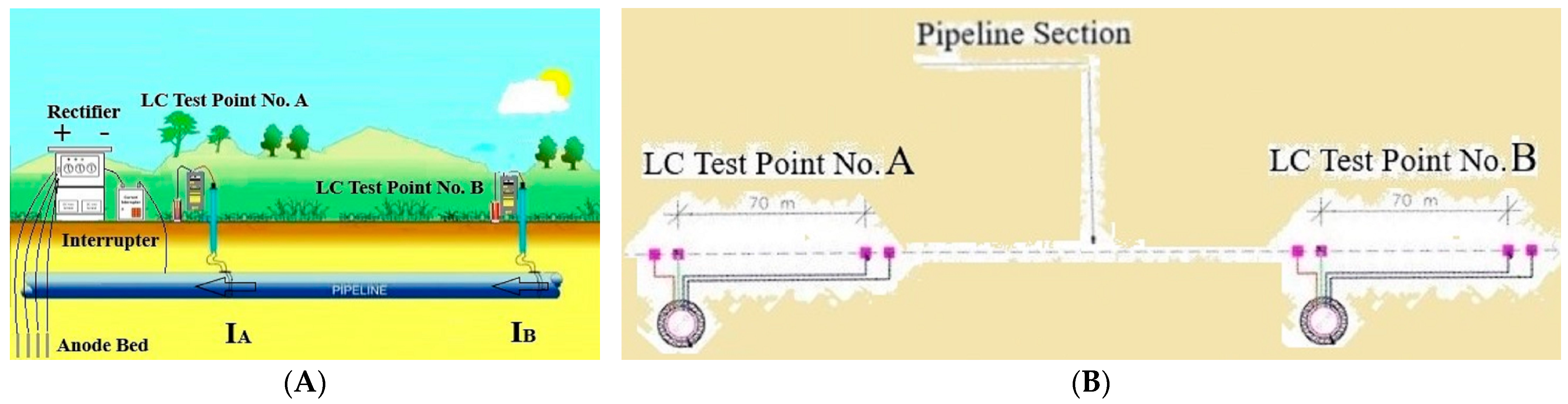

3.2. Assessment Methods of Underground Polymer-Coated Steel Pipelines

- a.

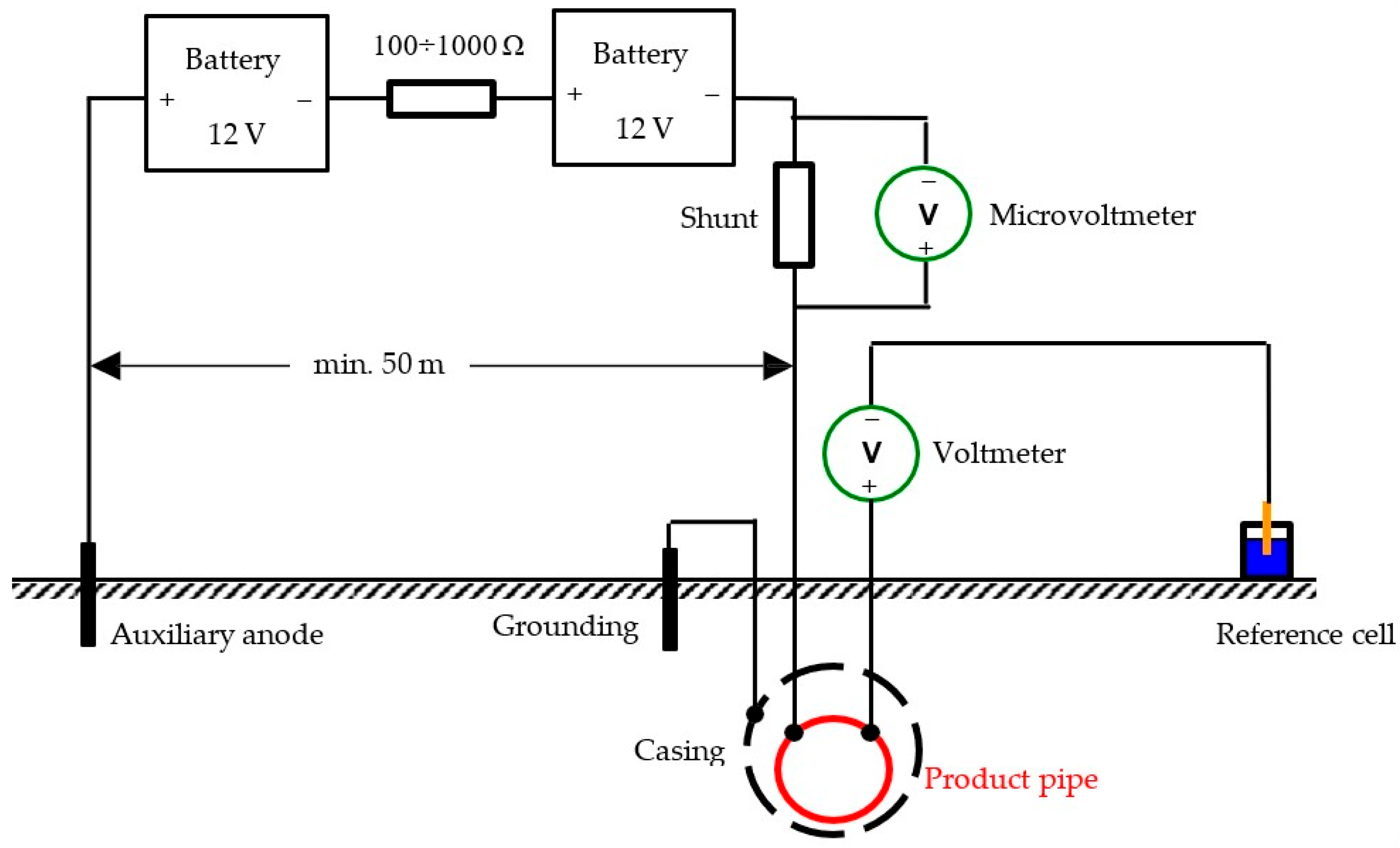

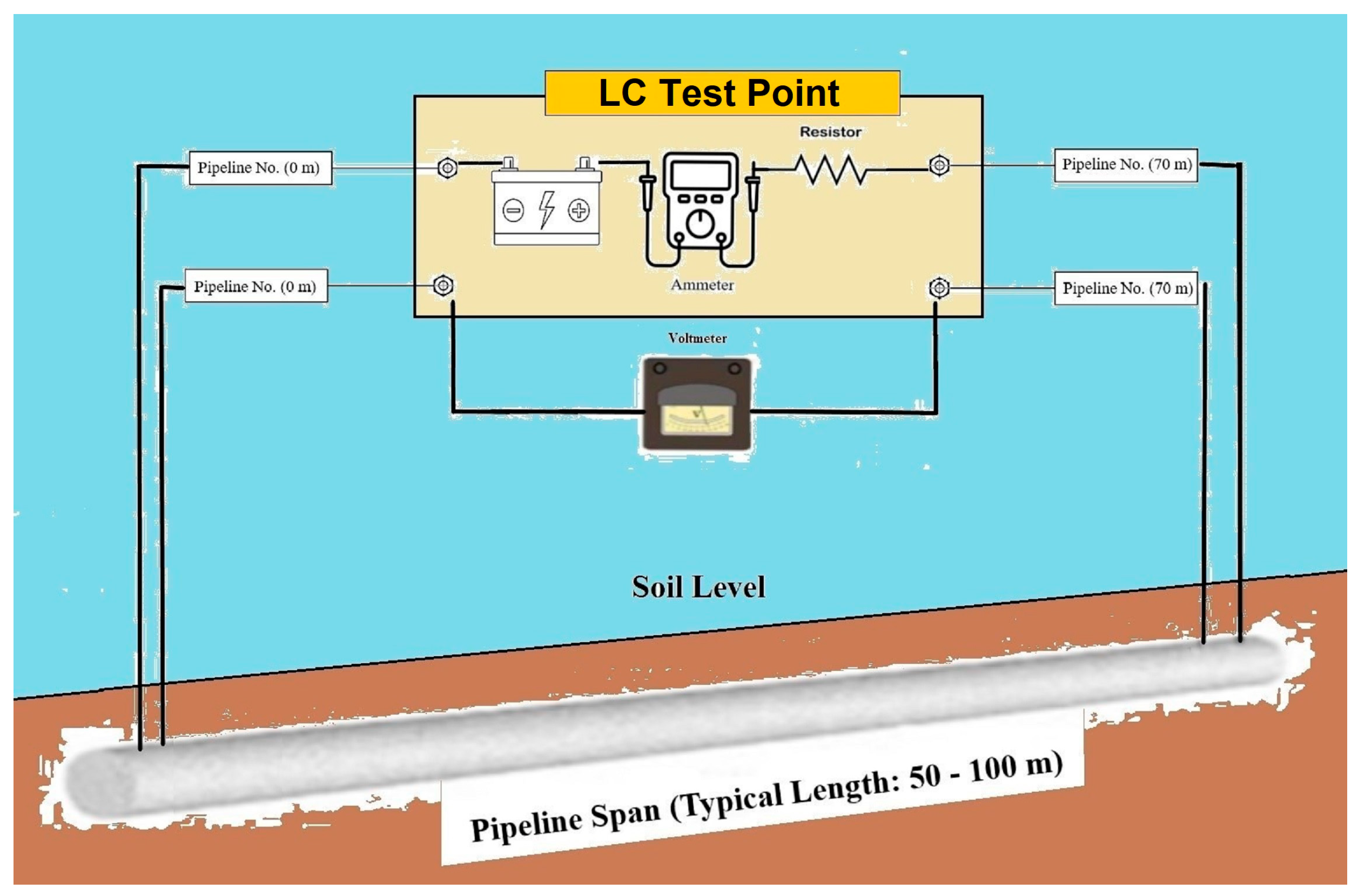

- First stage—Calibration of the line current (four-wire) test points for determining the electrical resistance of the tested pipeline sections with a defined LC length. The general arrangement for pipeline current measurement calibration is shown in Figure 4. An additional option for calculating the electrical resistance of the tested section is provided by the formula in Appendix B of the standard [36] (Standard Pipe Data Tables), but it is a less precise method compared with calibration. The main steps of the section’s calibration are as follows:

- 1.

- Measuring and recording the initial voltage (U0cal, mV) between inward terminals, as shown in Figure 4, and noting the voltage polarity.

- 2.

- Applying a test current Ical (mA) between outward test leads.

- 3.

- Measuring and recording the voltage (mV) change between inward terminals while interruption is applied with the chosen regime, like On/Off = 8:2 s, and noting the voltage polarity.

- 4.

- Measuring and recording the difference in current (mA) between the outward terminals.Calculating resistance in span (µΩ) as follows:

- 5.

- Steps 3, 4, and 5 are repeated with different electrical currents to verify results, obtain additional statistical data, and ensure repeatability.

- b.

- Second stage—The surveyed pipe section is connected to either a temporary or permanent cathodic station with a connected current interrupter at a specific time regime, like On/Off = 8:2 s. Measuring, recording, and calculating the potential change (ΔU) at each LC test location (µV or mV) between ON- and OFF- potentials are as follows:

- c.

- Third stage—Calculating the pipe current at each LC test location from the first and second stages.

- d.

- Fourth stage—The surveyed pipe section is still connected to a temporary or permanent cathodic station with a current interrupter, like On/ Off = 8:2 s. The measurement of the “ON” (φon [mV]) and “Off” (φoff [mV]) structure-to-electrolyte potentials at each LC test location should be conducted, as in the standard [81]. Calculating the difference between ON- and OFF-potentials.

- e.

- Fifth stage—Measuring the soil resistivity near each LC test location according to the Wenner four-pin or soil-box method [82]. Calculating the average soil resistivity of the surveyed pipeline section.

- f.

- Sixth stage—Calculating the surface area (A) of the surveyed pipe section between LC test locations (m2):where D—pipe outside diameter and L—length of the pipe section.A = π·D·L

- g.

- Seventh stage—Calculate the average change in pipe-to-electrolyte potential (Δφ avg) for each pipeline section (between LC test points A and B).where ΔφA = ΔφON-A − ΔφOff-A, the change in structure-to-electrolyte potential at point A, mV, and ΔφB = ΔφON-B − ΔφOff-B, the change in structure-to-electrolyte potential at point B, mV.

- h.

- Eighth stage—Calculating the current pick-up (ΔI) for each pipeline section (between LC test points A and B):∆I = ∆IA − ∆IB

- i.

- Ninth stage — Finally, calculating the coating average specific electrical resistance (Rcoat) for the pipeline section (between LC test points A and B) in Ω·m2.

- j.

- The obtained results have been normalized for a specific soil resistivity of 10 Ω·m, according to the requirements of the standard [36].

4. Aging Modeling

5. Results and Discussion

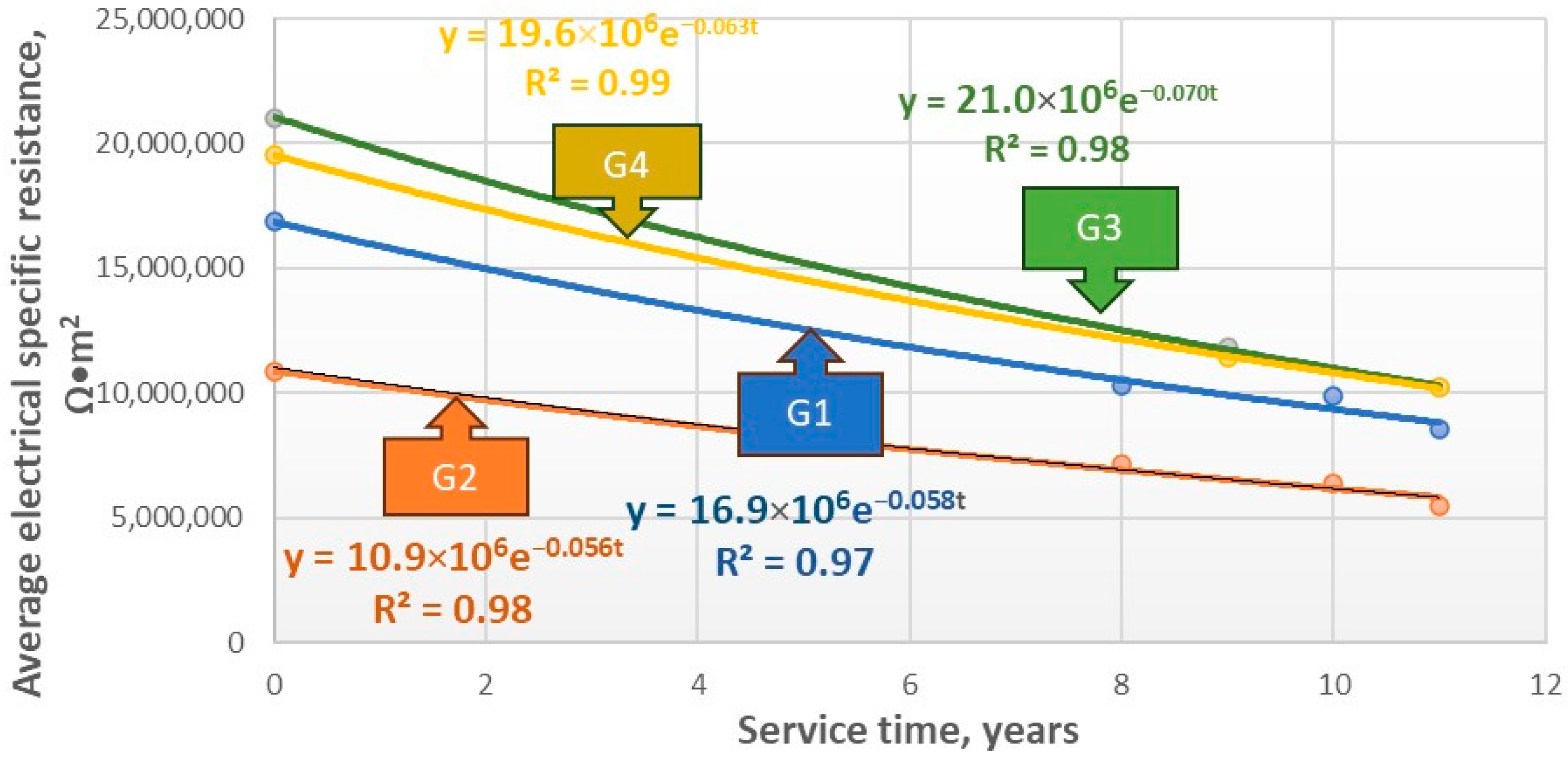

5.1. Oil/Gas Pipelines

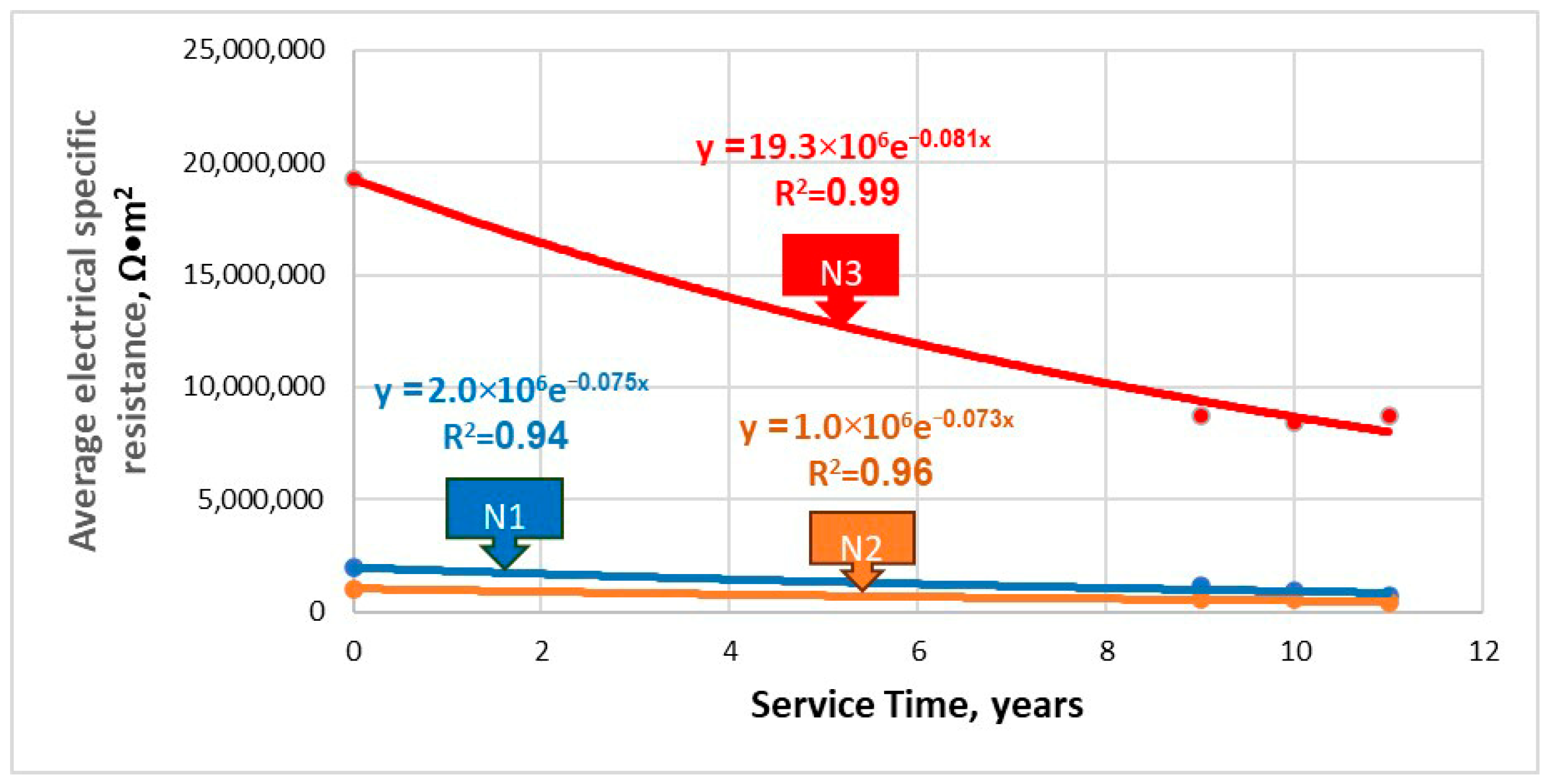

5.2. Water Pipelines

- a.

- The exponential model demonstrated a high determination fitting coefficient (R2) for predicting the aging of 3LPE-coated steel pipelines.

- b.

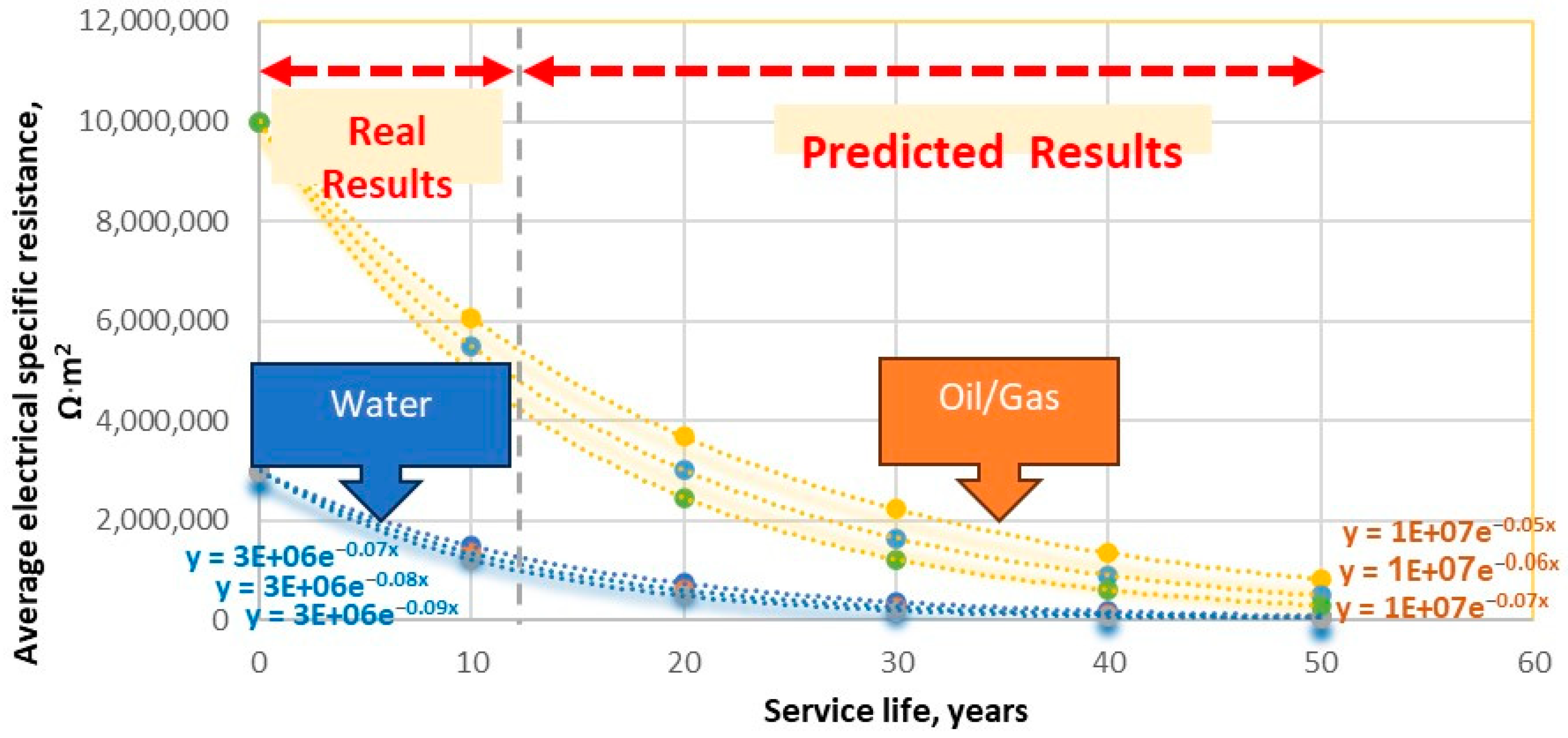

- Aging coefficients were determined and defined in the range from 0.05 to 0.07. Thus, the data suggests that 3LPE-coated pipelines exhibit minimal aging and are expected to have a long service life.

- c.

- The initial average specific electrical resistance of the coating system is a key factor affecting the aging coefficient. The higher it is, the faster the degradation.

- d.

- The predictive model based on the exponential model was shown to estimate the aging of 3LPE-coated steel pipelines, with high determination fitting coefficients.

- e.

- The aging coefficients fall within the range of 0.07 to 0.09, which exceeds the aging coefficient determined in oil/gas pipelines, suggesting a higher aging rate. However, the aging coefficient range is also low, proposing a relatively long service life.

- f.

- Coating systems with high initial electrical resistance tend to exhibit higher aging rates.

- g.

- An LCA-based inspection was conducted on one of the water pipelines intersecting a 400 kV AC high-voltage power line (HVAC). Unreliable results were obtained, making it inapt for such method. This conclusion is also relevant to oil/gas pipelines.

- Rc(t)—the average coating electrical resistance after service time t in underground exposure [Ω·m2];

- Rc(0)—the initial average coating electrical resistance after installation and backfilling (t = 0) [Ω·m2];

- α—the aging rate coefficient [1/year];

- t—service time [years].

- a.

- 3LPE-coated buried pipelines used for water and oil/gas exhibit low aging rates.

- b.

- Coatings that initially have higher average specific electrical resistance are more prone to faster aging than those with lower initial electrical resistance.

- c.

- For oil/gas pipelines, the aging coefficient α [1/year] changes in the range of 0.05–0.07; for water pipelines, in the range of 0.07–0.09. This indicates that 3LPE external coatings in oil/gas pipelines age more slowly than in water pipelines. The higher aging rates of polymer-coated water pipelines are primarily due to differences in coating technical characteristics compared to oil/gas pipelines, which contain numerous irregular geometrical connections (T-joints, elbows, consumer connections, air and drainage points). Most of the connections are coated with epoxy coatings applied in field conditions, which have significantly higher aging rates (coating breakdown factors) than the factory-applied 3LPE coating [35,49]. For oil/gas pipelines, the polymer-coated pipeline sections are usually constructed without epoxy-coated irregular geometrical shapes and adhere to strict quality control methods and pipeline installation procedures.

- a.

- The aging coefficient spans across a broader range (0.05 to 0.07 year−1) for oil and gas pipelines, indicating a potentially higher aging rate than the above-cited sources.

- b.

- Water pipelines exhibit a higher aging rate coefficient range (0.07–0.09 year−1) than oil/gas pipelines. This is primarily attributed to the frequent presence of field irregular geometry joints, such as T-connections and elbows, where two-part epoxy coatings are often applied in the field.

- c.

- Epoxy coatings have significantly higher aging rates, based on coating breakdown factors, than the factory-applied 3LPE coating [33].

- For the water pipeline, section N1 (L = 4920 m; Ø = 16″, initial average specific electrical resistance is 2.0 × 106 Ω·m2, minimum threshold of average electrical resistance for repair or replacement is 3 × 104 Ω·m2), the selected calculated aging coefficient α is 0.08 year −1. Since the operational time of this pipeline section is 10 years, the residual lifetime is 42.3 years.

- For the oil/gas pipeline, section G2 (L= 7757 m; Ø = 18′, the initial average specific electrical resistance is 10.9 × 106 Ω·m2, minimum threshold of average specific electrical resistance for repair or replacement is 3 × 104 Ω·m2), the selected aging coefficient α = 0.06 year −1. Since the operational time of the pipeline section is 10 years, the residual lifetime is 88.2 years.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Examples of the Residual Isolation Lifetime Calculations for Oil/Gas and Water Pipelines

- The calculation for water pipeline section N1.

- The calculation for oil/gas pipeline section G2.

References

- United States Department of Transportation. By Decade Installed; Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Fact Sheet—Corrosion; U.S. Department of Transportation, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://primis.phmsa.dot.gov/comm/FactSheets/FSCorrosion.htm (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Gas Pipeline Incidents. 12th Report of the European Gas Pipeline Incident Data Group (Period 1970–2022). European Gas Pipeline Incident Data Group (EGIG). Available online: https://www.EGIG.eu (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Romer, A.E.; Bell, G.E.C. Causes of External Corrosion on Buried Water Mains. In Proceedings of the Pipelines 2001, San Diego, CA, USA, 15–18 July 2001; American Society of Civil Engineers: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASME B31.8-2022; Gas Transmission and Distribution Piping Systems, ASME Code for Pressure Piping, B31. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- American Water Works Association. Prestressed Concrete Pressure Pipe, Steel-Cylinder Type; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWWA. M11-Steel Water Pipe: A Guide for Design and Installation, 5th ed.; AWWA Manual; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kishawy, H.A.; Gabbar, H.A. Review of pipeline integrity management practices. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 2010, 87, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWWA C213-22; Fusion-Bonded Epoxy Coatings and Linings for Steel Water Pipe and Fittings. American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA, 2022.

- API. Inspection Practices for Pressure Vessels, API Recommended Practice 572, 4th ed.; The American Petroleum Institute (API): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- API. Inspection Practices for Piping System Components, API Recommended Practice 574, 4th ed.; The American Petroleum Institute (API): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ASME B31.8S 2022; Managing System Integrity of Gas Pipelines, January 2023, ASME Code for Pressure Piping, B31 Supplement to ASME B31.8. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Zargarnezhad, H.; Asselin, E.; Wong, D.; Lam, C.N.C. A Critical Review of the Time-Dependent Performance of Polymeric Pipeline Coatings: Focus on Hydration of Epoxy-Based Coatings. Polymers 2021, 13, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, S.B.; Bingham, R.; Mills, D.J. Advances in corrosion protection by organic coatings: What we know and what we would like to know. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 102, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, M.; Shoaib, S.; Mubarak, N.M.; Inamuddin; Asiri, A.M. Factors influencing corrosion of metal pipes in soils. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, C.; Norman, D. Three Layer Polyolefin Coatings: Fulfilling Their Potential? In Proceedings of the NACE 61st Annual Conference & Exposition, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 9–11 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.; Nicholas, D. Fusion Bonded Polyethylene Coatings—40 Years On; Paper 094, Corrosion & Prevention; Steel Mains Pty Ltd.: Somerton, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, B.T.A.; Sue, H.-J.; Jiang, H.; Browning, B.; Wong, D.; Pham, H.; Guo, S.; Kehr, A.; Mallozzi, M.; Snider, W.; et al. Integrity of 3LPE Pipeline Coatings: Residual Stresses and Adhesion Degradation. In Proceedings of the 2008 7th International Pipeline Conference, Volume 2, Calgary, AB, Canada, 29 September–3 October 2008; ASMEDC: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2008; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, H.M.H.; Ben Seghier, M.E.A.; Zayed, T. A comprehensive review of corrosion protection and control techniques for metallic pipelines. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 143, 106885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermazi, N.; Elleuch, K.; Ayedi, H.F.; Kapsa, P. Aging effect on thermal, mechanical and tribological behaviour of polymeric coatings used for pipeline application. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 203, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melot, D.; Paugam, G.; Roche, M. Disbondments of Pipeline Coatings and their effects on corrosion risks. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pipeline Protection, Edinburgh, UK, 17–19 October 2007; BHR Group: Edinburgh, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, M.; Melot, D.; Paugam, G. Recent Experience with Pipeline Coating Failures. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Pipeline Protection, Paphos, Cyprus, 2–4 November 2005; BHR Group: Paphos, Cyprus, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ranade, S.; Tan, M.Y.; Forsyth, M. The Effects of Mechanical Stress, Environment and Cathodic Protection on the Degradation and Failure of Coatings: An Overview; Corrosion & Prevention 2014 Paper 50; Australasian Corrosion Association (ACA): Perth, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- NACE SP0169-2013; Control of External Corrosion on Underground or Submerged Metallic Piping Systems, 2013. NACE International: Houston, TX, USA; AMPP: Houston, TX, USA, 2024.

- ANSI/NACE SP0502-2010; Pipeline External Corrosion Direct Assessment Methodology. NACE International: Houston, TX, USA; AMPP: Houston, TX, USA, 2010; ISBN 1-57590-156-0.

- AWWA. M28 Rehabilitation of Water Mains, Manual of Water Supply Practices—M28, 3rd ed.; Rehabilitation of Water Mains; American Water Works Association (AWWA): Denver, CO, USA, 2014; Available online: https://store.awwa.org/M28-Rehabilitation-of-Water-Mains-Third-Edition (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Morrison, R.; Sangster, T.; Downey, D.; Matthews, J.; Condit, W.; Sinha, S.; Maniar, S.; Sterling, R. State of Technology for Rehabilitation of Water Distribution Systems; National Risk Management Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2013. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/gateway/science (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- De Freitas, D.S.; Brasil, S.L.D.C.; Leoni, G.; Motta, G.X.D.; Leite, E.G.B.; Coelho, J.F.P. Long-term cathodic disbondment tests in three-layer polyethylene coatings. Mater. Corros. 2023, 74, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbi, J.M. Coating Evaluation by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), Research and Development Office Science and Technology Program Final Report ST-2016-7673-1; Research and Development Office U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation: Denver, CO, USA, 2015.

- Merten, B.J.E. Electrochemical Impedance Methods to Assess Coatings for Corrosion Protection; Technical Publication No. 8540-2019-03; U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center Materials and Corrosion Laboratory: Denver, CC, USA, 2019.

- Mills, D.J.; Jamali, S.S. The best tests for anti-corrosive paints. And why: A personal viewpoint. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 102, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12954-2019; General Principles of Cathodic Protection of Buried or Immersed Onshore Metallic Structures. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- ISO_15589-1; Petroleum, Petrochemical and Natural Gas Industries—Cathodic Protection of Pipeline Systems Part 1: On-Land Pipelines. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- DNV RP B401-2021; Cathodic Protection Design. DNV AS: Oslo, Norway, 2021.

- DNVGL-RP-F103-2016; Cathodic Protection of Submarine Pipelines. DNV GL AS: Oslo, Norway, 2016.

- AMPP (NACE) TM0102-23; Measurement of Protective Coating Electrical Conductance on Underground Pipelines. AMPP: Houston, TX, USA, 2003. Available online: https://content.ampp.org/standards/book/972/Measurement-of-Protective-Coating-Electrical (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- GOST R 51164-1998; General Requirements for Protection Against Corrosion. Gosstandard of Russia: Moscow, Russia, 1998.

- Handbook of Cathodic Corrosion Protection: Theory and Practice of Electrochemical Protection Processes, 3rd ed.; Baeckmann, W., von Schwenk, W., Prinz, W., Eds.; Gulf Pub. Co.: Houston, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Glazov, N.P.; Shamshetdinov, K.L. Protection of Steel Pipelines against Underground Corrosion. Prot. Met. 2002, 38, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazov, N.P. Peculiarities of the Corrosion Protection of Steel Underground Pipelines. Prot. Met. 2004, 40, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazov, N.P.; Shamshetdinov, K.L.; Glazov, N.N. Comparative analysis of requirements to insulating coatings of pipelines. Prot. Met. 2006, 42, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21809-1:2018; Petroleum and Natural Gas Industries—External Coatings for Buried or Submerged Pipelines Used in Pipeline Transportation Systems Part 1: Polyolefin Coatings (3-Layer PE and 3-Layer PP). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- DIN 30670-2012; Polyethylene Coatings on Steel Pipes and Fittings Requirements and Testing. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- American Water Works Association. ANSI/AWWA C215-10, Extruded Polyolefin Coatings for the Exterior of Steel Water Pipelines; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SI 30670-2021; Polyethylene Coatings on Steel Pipes and Fittings—Requirements and Testing (Updates in Hebrew). SII: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2021.

- ISO 21809-3: 2016; Petroleum and Natural Gas Industries—External Coatings for Buried or Submerged Pipelines Used in Pipeline Transportation Systems Part 3: Field Joint Coatings. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- DIN 30672-2000; Tape and Shrinkable Materials for the Corrosion Protection of Buried or Underwater Pipelines Without Cathodic Protection for Use at Operating Temperatures Up to 50 °C. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung and DVGW Deutscher Verein des Gas-und Wasserfaches e.V. (German Associaton of Gas and Water Engineers): Berlin, Germany, 2000.

- BS EN 12068:1999; Cathodic Protection. External Organic Coatings for the Corrosion Protection of Buried or Immersed Steel Pipelines Used in Conjunction with Cathodic Protection. Tapes and Shrinkable Materials. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 0580302296.

- Recommended Practice DNV-RP-F102; Pipeline Field Joint Coating and Field Repair of Linepipe Coating. Det Norske Veritas: Oslo, Norway, 2011.

- Lampman, S. Characterization and Failure Analysis of Plastics; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2003; pp. 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeen, L. The effect of heat aging on the properties of polyolefins, polyvinyls, and acrylics. In The Effect of Long Term Thermal Exposure on Plastics and Elastomers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsman, P. Review on the thermo-oxidative degradation of polymers during processing and in service. E-Polymer 2008, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D. Polymer Weathering: Photo-Oxidation. J. Polym. Environ. 2002, 10, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.R.; Turnbull, A. Weathering of polymers: Mechanisms of degradation and stabilization, testing strategies and modelling. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 584–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsuan, Y.G.; Koerner, R.M. Antioxidant depletion lifetime in high density polyethylene geomembranes. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. ASCE 1998, 124, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.K.; Sangam, H.P. Durability of HDPE geomembranes. Geotext. Geomembr. 2002, 20, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, W.L. Polymer Degradation and Stabilization; Polymers Properties and Applications; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plota, A.; Masek, A. Lifetime Prediction Methods for Degradable Polymeric Materials—A Short Review. Materials 2020, 13, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangam, H.P.; Rowe, R.K. Effects of exposure conditions on the depletion of antioxidants from high-density polyethylene (HDPE) geomembranes. Can. Geotech. J. 2002, 39, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.K.; Islam, M.Z.; Brachman, R.W.I.; Arnepalli, D.N.; Ewais, A.R. Antioxidant Depletion from a High Density Polyethylene Geomembrane under Simulated Landfill Conditions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2010, 136, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.; Gerald, S. Polymer Degradation and Stabilisation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gugumus, F. Critical antioxidant concentrations in polymer oxidation—I. Fundamental aspects. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1998, 60, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsuan, Y.G.; Schroeder, H.F.; Rowe, K.; Müller, W.; Greenwood, J.; Cazzuffi, D.; Koerner, R.M. Long-term Performance and Lifetime Prediction of Geosynthetics. In Proceedings of the EuroGeo 4-4th European Geosynthetics Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 7–10 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gerald, S. Antioxidants. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1988, 61, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweifel, H. Stabilization of Polymeric Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, G. (Ed.) Plastics Additives: An A-Z Reference; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 73–79. ISBN 978-94-010-6477-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hsuan, Y.; Koerner, R.; Lord, A. A Review of the Degradation of Geosynthetic Reinforcing Materials and Various Polymer Stabilization Methods. In Geosynthetic Soil Reinforcement Testing Procedures; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemchuk, P.P.; Horng, P.-L. Transformation products of hindered phenolic antioxidants and colour development in polyolefins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1991, 34, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habicher, W.D.; Bauer, I.; Pospíšil, J. Organic Phosphites as Polymer Stabilizers. Macromol. Symp. 2005, 225, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphris, K.J.; Scott, G. Mechanisms of antioxidant action: Reactions of phosphites with hydroperoxides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1973, 2, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krushelnitzky, R.P.; Brachman, R.W.I. Antioxidant depletion in high-density polyethylene pipes exposed to synthetic leachate and air. Geosynth. Int. 2011, 18, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsuan, Y.G.; Li, M.; Koerner, R.M. Stage “‘C’” Lifetime Prediction of HDPE Geomembrane Using Acceleration Tests with Elevated Temperature. In Geosynthetics Research and Development in Progress; American Society of Civil Engineers: Austin, TX, USA, 2008; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, W.W.; Jakob, I.; Tatzky-Gerth, R.; Wöhlecke, A. A study on antioxidant depletion and degradation in polyolefin-based geosynthetics: Sacrificial versus regenerative stabilization. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2016, 56, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DVWG GW 12 (A); Technische Regel—Arbeitsblatt, Planung und Einrichtung des kathodischen Korrosionsschutzes (KKS) für erdverlegte Lagerbehälter und Stahlrohrleitung (Planning and Installing of Cathodic Corrosion Protection (CP) for Buried Storage Tanks and Steel Pipes-p. 7.2). DVGW Deutscher Verein des Gas- und Wasserfaches e. V.: Bonn, Germany, 2010.

- AfK-Empfehlung Nr. 10-2000; Verfahren zum Nachweis der Wirksamkeit des des kathodischen Korrosionsschutzes an erdverlegten Rohrleitungen. DVGW Deutscher Verein des Gas- und Wasserfaches e. V.: Bonn, Germany, 2000.

- NACE TM0109-09; Aboveground Survey Techniques for the Evaluation of Underground Coating Condition. NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 2009; ISBN 1-57590-226-5.

- NACE SP0207-2007; Performing Close-Interval Potential Surveys and DC Surface Potential Gradient Surveys on Buried or Submerged Metallic Pipelines. NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 2007.

- Holtsbaum, W.B. Cathodic Protection Survey Procedures; NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Auckland, D.W.; Cooper, R. Factors affecting water absorption by polyethylene. In Proceedings of the Conference on Electrical Insulation & Dielectric Phenomena—Annual Report, Downingtown, PA, USA, 21–23 October 1974; IEEE: Downingtown, PA, USA, 1974; pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NACE SP0286-2007; Standard Recommended Practice: Electrical Isolation of Cathodically Protected Pipelines. NACE International: Houston, TX, USA, 2007.

- NACE Standard TM0497-2012; Standard Test Method, Measurement Techniques Related to Criteria for Cathodic Protection on Underground or Submerged Metallic Piping Systems. NACE International: Houston, TX, USA; AMPP: Houston, TX, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- ASTM G57; Standard Test Method for Field Measurement of Soil Resistivity Using the Wenner Four-Electrode Method. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ANSI/API 5L, ISO 3183:2007 (Modified); Petroleum and Natural Gas Industries—Steel Pipe for Pipeline Transportation Systems, 44th ed. American Petroleum Institute, (API): Washington, DC, USA; The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Kriston, I.; Földes, E.; Staniek, P.; Pukánszky, B. Dominating reactions in the degradation of HDPE during long term ageing in water. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroka, S.M.; Smiley, T.D.; Tanko, J.M.; Dietrich, A.M. Reaction mechanism for oxidation and degradation of high density polyethylene in chlorinated water. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangaj, N.S.; Malshe, V.C. Permeability of polymers in protective organic coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2004, 50, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyrkova, L.I.; Osadchuk, S.O.; Goncharenko, L.V.; Rybakov, A.O.; Kharchenko, Y.O. Influence of long-term operation on the properties of main gas pipeline steels. A review. Phys. Chem. Solid State 2024, 25, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipilov, S.A.; Le May, I. Structural integrity of aging buried pipelines having cathodic protection. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2006, 13, 1159–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.Y.; Atrens, A.; Wang, J.Q.; Han, E.H.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Ke, W. Review of stress corrosion cracking of pipeline steels in “low” and “high” pH solutions. J. Mater. Sci. 2003, 38, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.; Iqbal, J.; Ahmed, F. Stress corrosion failure of high-pressure gas pipeline. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2007, 14, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.Y.; Varela, F.; Huo, Y.; Gupta, R.; Abreu, D.; Mahdavi, F.; Hinton, B.; Forsyth, M. An Overview of New Progresses in Understanding Pipeline Corrosion. Corros. Sci. Technol. 2016, 15, 271–280, Correction in Corros. Sci. Technol. 2017, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peabody, A.W. Peabody’s Control of Pipeline Corrosion, 3rd ed.; NACE International, The Worldwide Corrosion Authority: Houston, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pipeline Designation | Diameter (Inch) | Length (m) | Wall Thickness (mm) | Pipeline’s Age (Year) | The Initial Average Specific Electrical Resistance of the Pipeline Section, (Ω·m2) (*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 (N1) South | 16 | 4920 | 4.0 | 11 | 1.9 × 106 |

| N2 (N2) South | 20 | 4990 | 4.0 | 11 | 1.0 × 106 |

| N3 (N3) South | 24 | 4940 | 4.8 | 11 | 1.9 × 106 |

| N4 (N11) Center | 100 | 1200 | 15.9 | 11 | 4.3 × 106 |

| G1 (G51) Center | 18 | 9420 | 12.35 | 11 | 17 × 106 |

| G2 (G52) Center | 18 | 7760 | 12.35 | 11 | 11 × 106 |

| G3 (G53) North | 10 | 14,730 | 10.30 | 11 | 21 × 106 |

| G4 (G54) North | 18 | 12,540 | 12.35 | 11 | 19 × 106 |

| Pipeline Designation (*) | Initial Coating Electrical Resistance, Ω·m2 (**) | Type of Test | Coating Electrical Resistance, Ω·m2, vs. Service Time, Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Years | 9 Years | 10 Years | 11 Years | |||

| N1 | 2.0 × 106 | LCA Test | - | 1.2 × 106 | 0.9 × 106 | 0.7 × 106 |

| N2 | 1.0 × 106 | LCA Test | - | 0.6 × 106 | 0.5 × 106 | 0.4 × 106 |

| N3 | 19.2 × 106 | LCA Test | - | 8.7 × 106 | 8.4 × 106 | 8.7 × 106 |

| N4 | 4.3 × 106 | LCA Test | - | - | (***) | - |

| G1 | 16.9 × 106 | LCA Test | 10.0 × 106 | - | 9.6 × 106 | 9.4 × 106 |

| 16.9 × 106 | Drainage Test | - | - | 1.4 × 106 | - | |

| G2 | 10.9 × 106 | LCA Test | 7.1 × 106 | - | 6.4 × 106 | 5.4 × 106 |

| 10.9 × 106 | Drainage Test | - | - | 1.4 × 106 | - | |

| G3 | 21.0 × 106 | LCA Test | - | 11.8 × 106 | - | 9.1 × 106 |

| 21.0 × 106 | Drainage Test | - | - | 0.7 × 106 | - | |

| G4 | 19.5 × 106 | LCA Test | - | 11.6 × 106 | - | 9.2 × 106 |

| 19.5 × 106 | Drainage Test | - | - | 0.7 × 106 | - | |

| Pipeline Designation | Prediction Model | Calculated Average Aging Coefficient, α, 1/Year |

|---|---|---|

| G51 | RC(t) = 16.9 × 106e−0.058t | 0.058 |

| G52 | RC(t) = 10.9 × 106e−0.056t | 0.056 |

| G53 | RC(t) = 21.0 × 106e−0.070t | 0.070 |

| G54 | RC(t) = 19.6 × 106e−0.063t | 0.063 |

| Pipeline Designation | Prediction Model | Calculated Average Aging Coefficient, α, 1/Year |

|---|---|---|

| N1 | RC(t) = 2.0 × 106e−0.075t | 0.075 |

| N2 | RC(t) = 1.0 × 106e−0.073t | 0.073 |

| N3 | RC(t) = 19.3 × 106e−0.081t | 0.081 |

| The Aging Coefficient, 1/Year | Oil/Gas Pipelines | Water Pipelines |

|---|---|---|

| Calculated Range | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| Average | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Minimum | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Maximum | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| The General Prediction Model |

| Service Time, Years | Oil/Gas Pipelines | Water Pipelines | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α = 0.05 | α = 0.06 | α = 0.07 | α = 0.07 | α = 0.08 | α = 0.09 | |

| 0 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 3.0 × 106 | 3.0 × 106 | 3.0 × 106 |

| 10 | 6.1 × 106 | 5.5 × 106 | 5.0 × 106 | 1.5 × 106 | 1.3 × 106 | 1.2 × 106 |

| 20 | 3.7 × 106 | 3.0 × 106 | 2.5 × 106 | 0.7 × 106 | 0.6 × 106 | 0.5 × 106 |

| 30 | 2.2 × 106 | 1.7 × 106 | 1.2 × 106 | 0.4 × 106 | 0.3 × 106 | 0.2 × 106 |

| 40 | 1.4 × 106 | 0.9 × 106 | 0.6 × 106 | 0.2 × 106 | 0.1 × 106 | 0.8 × 105 |

| 50 | 0.8 × 106 | 0.5 × 106 | 0.3 × 106 | 0.9 × 105 | 0.5 × 105 | 0.3 × 105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neizvestny, G.R.; Kenig, S.; Kovler, K. Aging Investigation of Polyethylene-Coated Underground Steel Pipelines. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040062

Neizvestny GR, Kenig S, Kovler K. Aging Investigation of Polyethylene-Coated Underground Steel Pipelines. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2025; 6(4):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040062

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeizvestny, Gregory R., Samuel Kenig, and Konstantin Kovler. 2025. "Aging Investigation of Polyethylene-Coated Underground Steel Pipelines" Corrosion and Materials Degradation 6, no. 4: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040062

APA StyleNeizvestny, G. R., Kenig, S., & Kovler, K. (2025). Aging Investigation of Polyethylene-Coated Underground Steel Pipelines. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 6(4), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040062