Field Exposure of Duplex Stainless Steel in the Marine Environment: The Impact of the Exposure Zone

Abstract

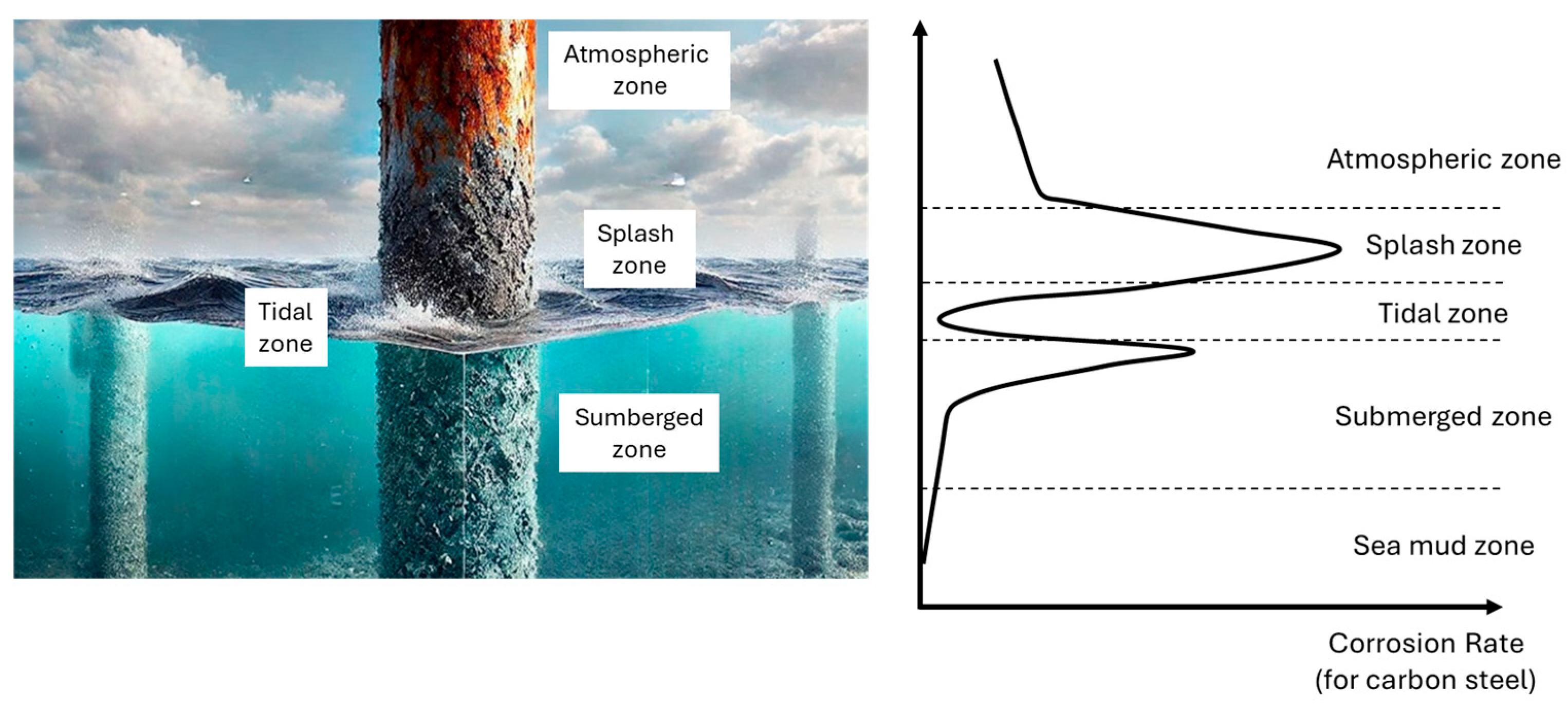

1. Introduction

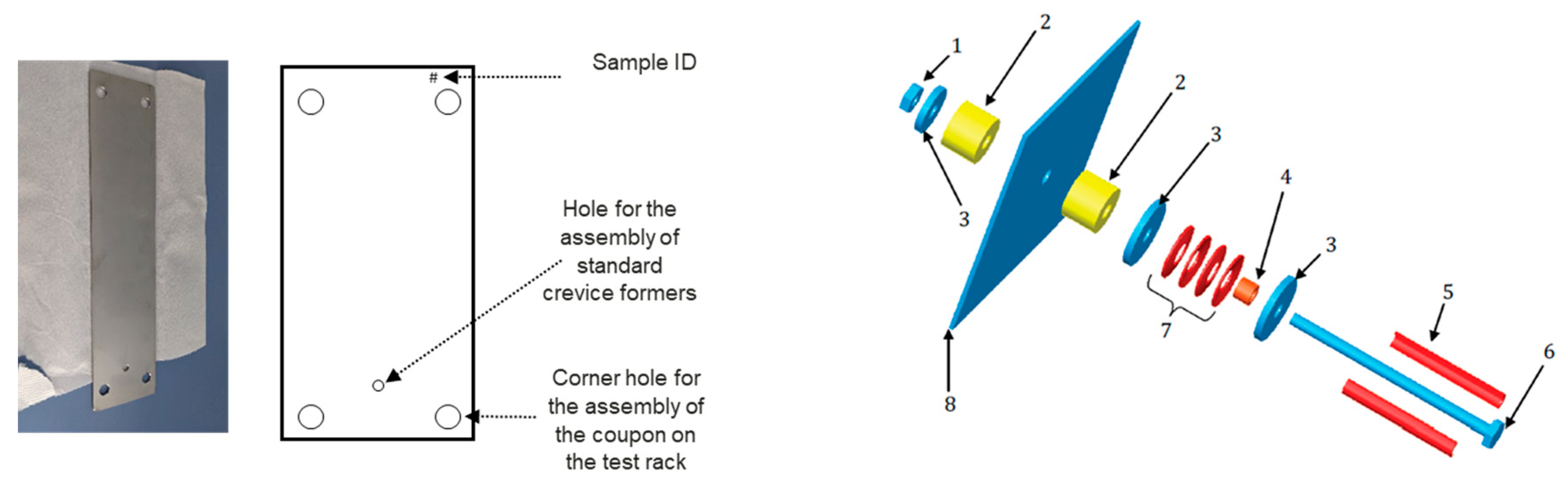

2. Materials and Methods

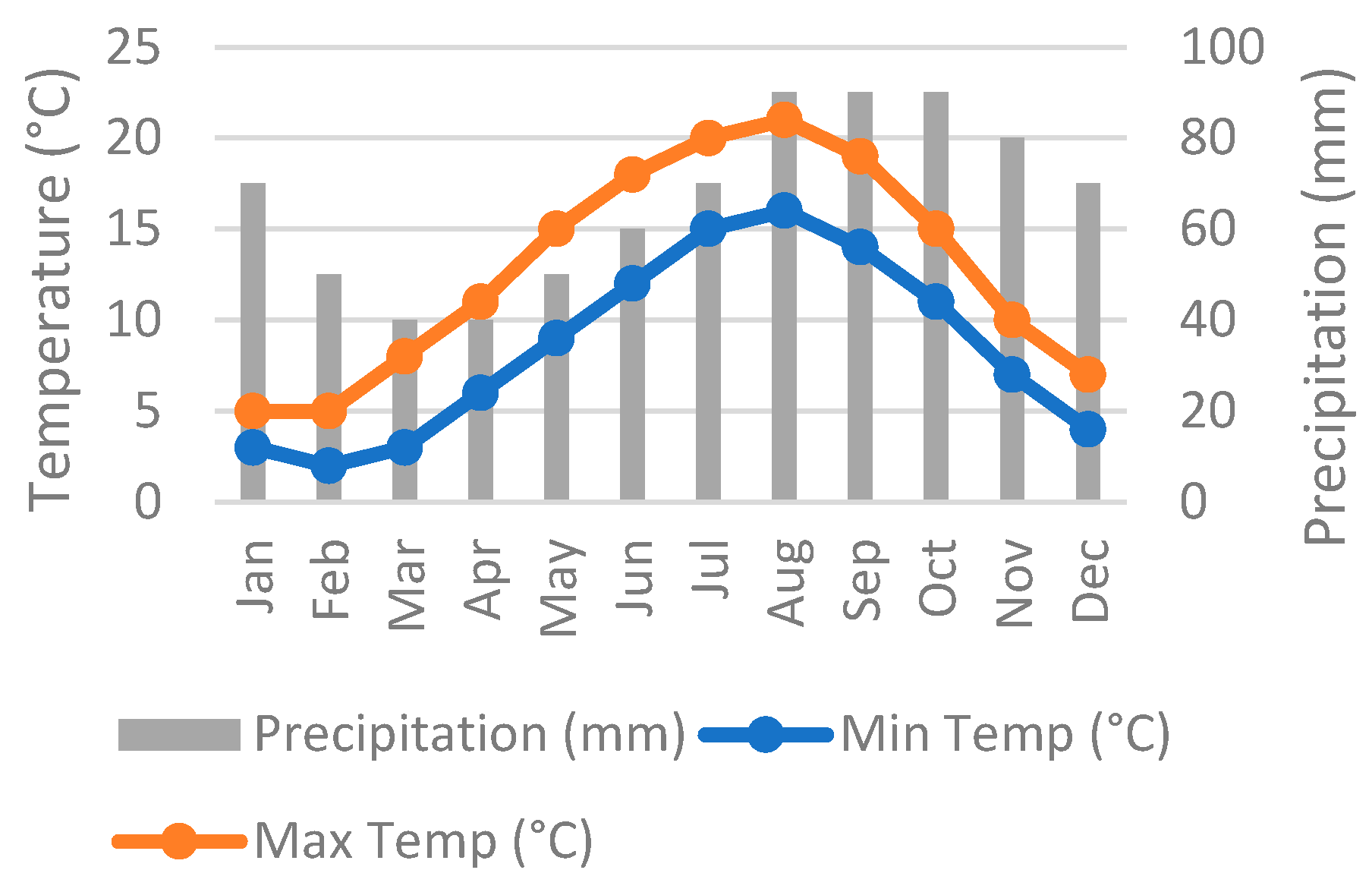

2.1. The Location of the Field Test

2.2. Inspection and Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

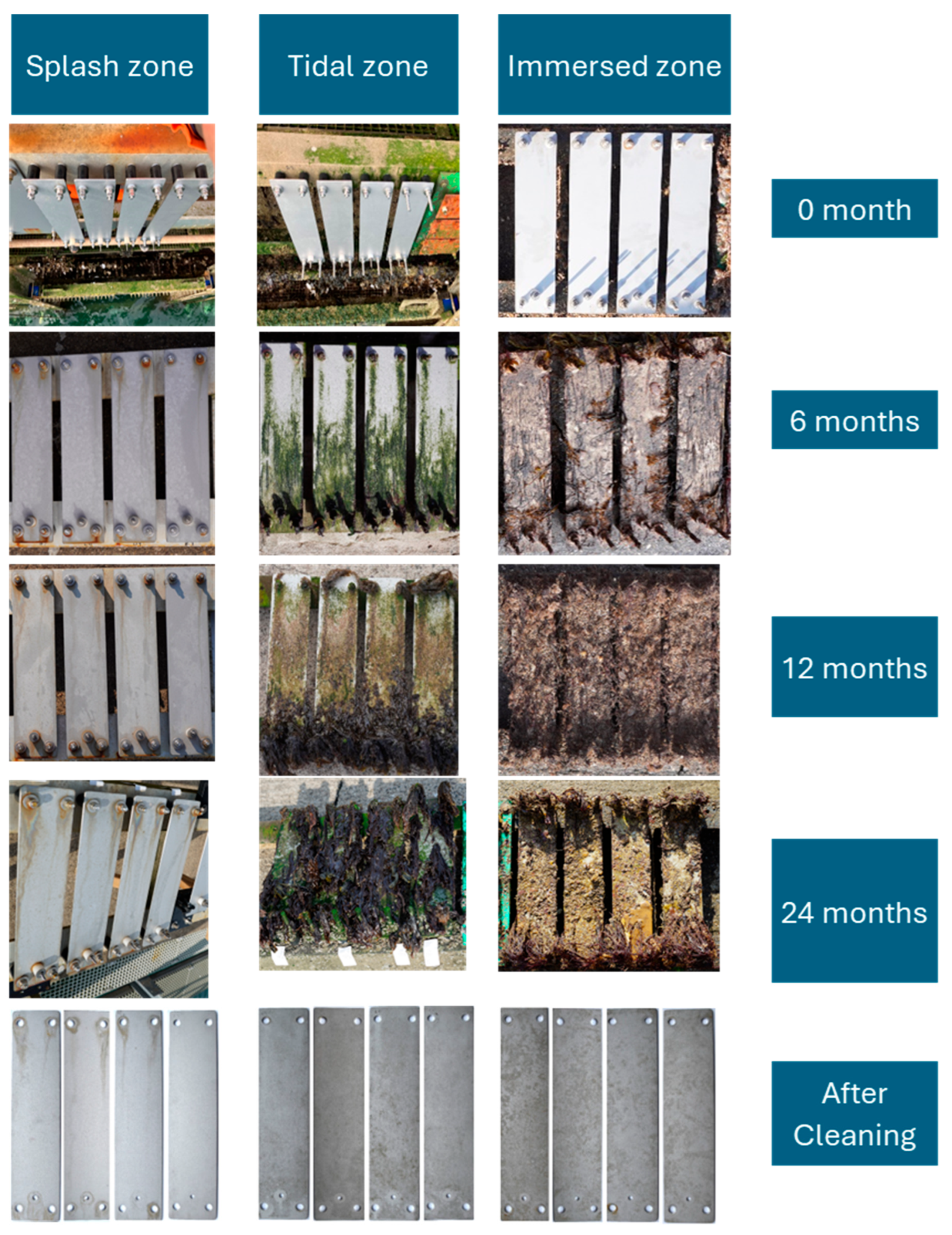

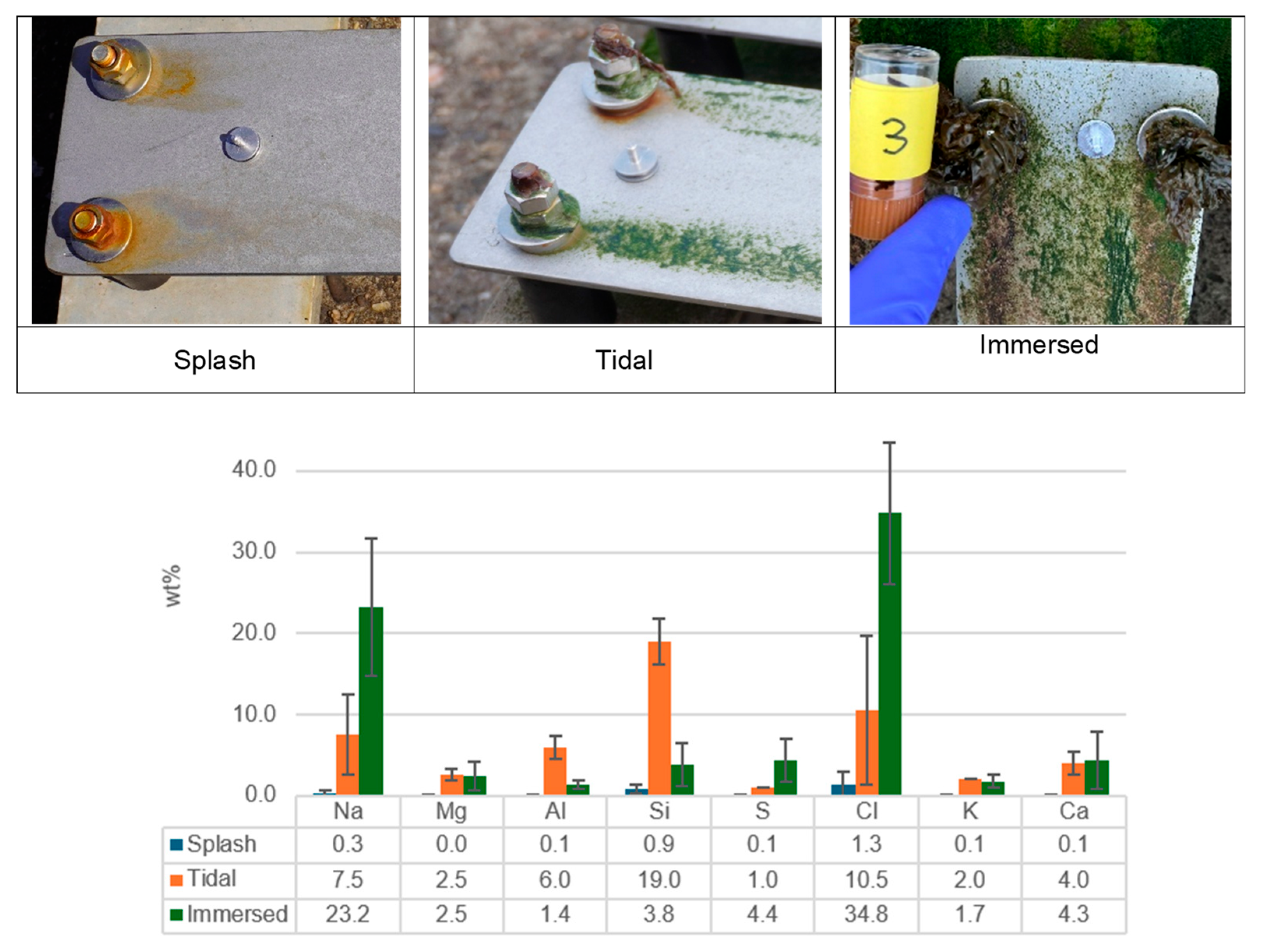

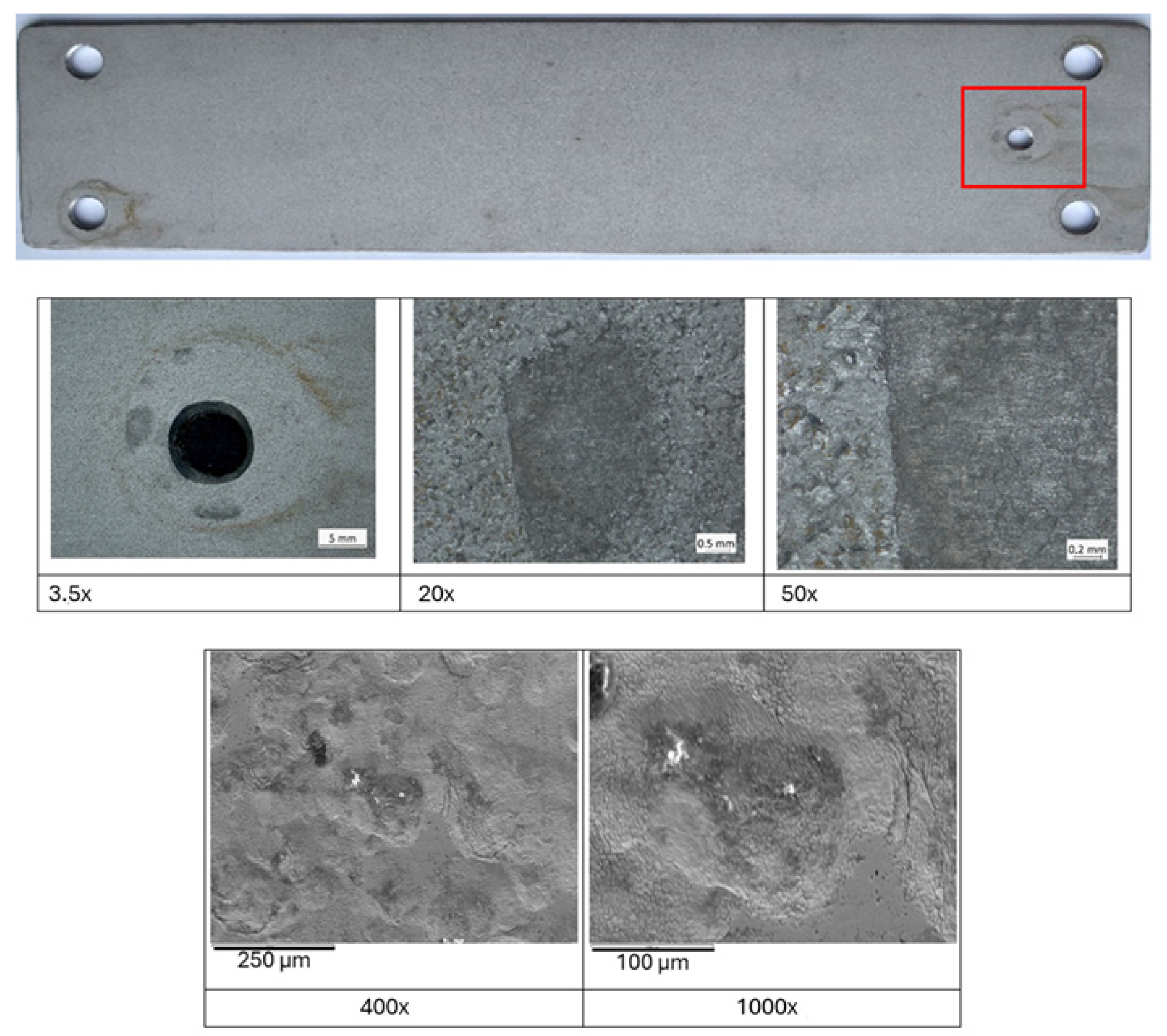

3.1. Inspection and Visual Examination After 6, 12, 24 Months

3.2. Corrosion Resistance of Duplex Stainless Steel in Various Marine-Tested Zones After a Two-Year Field Trial

4. Conclusions

- All duplex stainless steels exhibit resistance to pitting corrosion under all tested conditions. Despite the formation of thick biofilm deposits on the exposed coupons in both the tidal and immersed zones, no microbiologically induced pitting corrosion was identified.

- Crevice corrosion was shown to be the main challenge for the use of duplex stainless steel in marine environments. The crevice corrosion resistance of exposed coupons was assessed via standard Crevcorr crevice formers (with the torque of 3 Nm) as well as the installation of test coupons on the rig (with the torque presumably >3 Nm) in various corrosion zones. The results suggest that the highly alloyed duplex grade 1.4410 is the preferred choice based on specific exposure conditions. The alloying elements, particularly chromium (Cr), molybdenum (Mo), and nickel (Ni), play a crucial role in enhancing the crevice corrosion resistance of this grade.

- The austenitic EN 1.4404 as a reference exhibited both pitting and crevice corrosion after 12 months of exposure in the splash zone and atmospheric zone.

- Based on the corrosion performance of materials observed over a two-year exposure period, the ranking of corrosiveness at various exposure sites in the North Sea, arranged from highest to lowest, is as follows: Splash Zone > Tidal Zone > Immersed Zone. This ranking indicates that the Splash Zone exhibits the most aggressive corrosion conditions, while the Immersed Zone demonstrates the least severe corrosion effects. This information is crucial for selecting appropriate materials for marine applications and understanding the environmental factors contributing to corrosion in these areas.

- According to the current observations, the corrosivity of the exposure site in this study can be categorized in the border between low and medium. However, for proper material selection in the marine environment, with its diverse meteorological and oceanographic parameters, further field exposures at various exposure sites (e.g., warmer bodies of water) are required, which will be addressed in our future projects.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Market Outlook for Solar Power 2025–2029—SolarPower Europe. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/global-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2025-2029/detail (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Khan Afridi, S.; Ali Koondhar, M.; Ismail Jamali, M.; Muhammed Alaas, Z.; Alsharif, M.H.; Kim, M.-K.; Mahariq, I.; Touti, E.; Aoudia, M.; Ahmed, M.M.R. Winds of Progress: An In-Depth Exploration of Offshore, Floating, and Onshore Wind Turbines as Cornerstones for Sustainable Energy Generation and Environmental Stewardship. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 66147–66166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larché, N.; Leballeur, C.; Diler, E.; Thierry, D. Crevice Corrosion of High-Grade Stainless Steels in Seawater: A Comparison Between Temperate and Tropical Locations. Corrosion 2023, 79, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Yang, C.; Xu, D.; Sun, D.; Nan, L.; Sun, Z.; Li, Q.; Gu, T.; Yang, K. Laboratory Investigation of the Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC) Resistance of a Novel Cu-Bearing 2205 Duplex Stainless Steel in the Presence of an Aerobic Marine Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm. Biofouling 2015, 31, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeira, C.A.C.; Tiller, A.K. Microbially Corrosion: 3rd International Workshop: Papers, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-0-367-81410-6. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fozan, S.A.; Malik, A.U. Effect of Seawater Level on Corrosion Behavior of Different Alloys. Desalination 2008, 228, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larché, N.; Diler, E.; Thierry, D. Crevice and Pitting Corrosion of Stainless-Steel and Nickel Based Alloys in Deep Sea Water. In Proceedings of the Corrosion, Nashville, TN, USA, 24–28 March 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; YU, X.; Zhang, Q.; Marco, R.D. Corrosion Performance of High Strength Low Alloy Steel AISI 4135 in the Marine Splash Zone. Electrochemistry 2017, 85, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabux, W.; Causon, P.; Brennan, F. Profiling Corrosion Rates for Offshore Wind Turbines with Depth in the North Sea. Energies 2020, 13, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebell, G.; Tannert, S.; Lehmann, J.; Müller, H. Offshore Weathering Campaign on a North Sea Wind Farm Part One: Corrosivity Categories. Mater. Corros. 2025, 76, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diler, E.; Larché, N.; Thierry, D. Carbon Steel Corrosion and Cathodic Protection Data in Deep North Atlantic Ocean. Corrosion 2020, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.I.; Li, X. Corrosion of Stainless Steels in the Marine Splash Zone. AMR 2012, 610–613, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iribarren Laco, J.I.; Liesa Mestres, F.; Cadena Villota, F.; Bilurbina Alter, L. Urban and Marine Corrosion: Comparative Behaviour Between Field and Laboratory Conditions. Mater. Corros. 2004, 55, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.A.; Daille, L.; Aguirre, J.; Galarce, C.; Armijo, F.; De La Iglesia, R.; Pizarro, G.; Vargas, I.; Walczak, M. Corrosion of Stainless Steel in Simulated Tide of Fresh Natural Seawater of South East Pacific. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 6873–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larché, N.; Thierry, D.; Debout, V.; Blanc, J.; Cassagne, T.; Peultier, J.; Johansson, E.; Taravel-Condat, C. Crevice Corrosion of Duplex Stainless Steels in Natural and Chlorinated Seawater. Rev. Metall. 2011, 108, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18070:2015; Corrosion of Metals and Alloys—Crevice Corrosion Formers with Disc Springs for Flat Specimens or Tubes Made from Stainless Steel. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/61290.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Exposure Site Catalogue. Available online: https://corrosion-sites.com/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Heligoland Climate: Weather by Month, Temperature, Rain—Climates to Travel. Available online: https://www.climatestotravel.com/climate/germany/heligoland (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ISO 9223:2012; Corrosion of Metals and Alloys—Corrosivity of Atmospheres—Classification, Determination and Estimation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/53499.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- A380/A380M; Standard Practice for Cleaning, Descaling, and Passivation of Stainless Steel Parts, Equipment, and Systems. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://store.astm.org/a0380_a0380m-17.html (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Lahodny-Šarc, O.; Kulušić, B.; Krstulović, L.; Sambrailo, D.; Ivić, J. Stainless Steel Crevice Corrosion Testing in Natural and Synthetic Seawater. Mater. Corros. 2005, 56, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, F.; Xia, J.; Huang, K.; Zhang, B.; Wu, J. A Comparison Study of Crevice Corrosion on Typical Stainless Steels Under Biofouling and Artificial Configurations. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameng, S.H.; Wegrelius, L.; Tigerstrand, C.; Frigo, M. Atmospheric Corrosion Resistance of Stainless Steel: Results of a Field Exposure in Italy. In Proceedings of the AMPP Conference 2024, New Orleans, LA, USA, 3 March 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mameng, S.H.; Backhouse, A. Atmospheric Corrosion Resistance of Stainless Steel in Marine Environments: Results of a Field Exposure Pro-Gram in Sweden. In Proceedings of the Eurocorr 2019, Sevelle, Spain, 9–13 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mameng, S.H.; Pongsaksawad, W.; Tigerstrand, C.; Wangjina, P. Atmospheric Corrosion Resistance of Stainless Steel: Field Exposures of Stainless Steel in Chloride-Rich Atmospheric Conditions. In Proceedings of the CONFERENCE 2025, Nashville, TN, USA, 6–10 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Larché, N.; Thierry, D. Crevice Corrosion Evaluation of Stainless Steels for Marine Applications; IC Report 2009-1; French Corrosion Institute: Brest, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ul-Hamid, A.; Saricimen, H.; Quddus, A.; Mohammed, A.I.; Al-Hems, L.M. Corrosion Study of SS304 and SS316 Alloys in Atmospheric, Underground and Seawater Splash Zone in the Arabian Gulf. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameng, S.H.; Wegrelius, L.; Hosseinpour, S. Stainless Steel Selection Tool for Water Application: Pitting Engineering Diagrams. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1353907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrosion Handbook, 12th ed.; Outokumpu Oyj: Helsinki, Finland, 2023.

- Johnsen, R.; Bardal, E. The Effect of a Microbiological Slime Layer on Stainless Steel in Natural Sea Water. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 1986, Houston, TX, USA, 17–21 March 1986; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.; Hodgkiess, T. Comparative Study of Stainless Steel and Related Alloy Corrosion in Natural Sea Water. Br. Corros. J. 1998, 33, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallén, B. Corrosion of Duplex Stainless Steels in Seawater; Avesta Sheffield Corrosion Management and Application Engineering; 1-1998. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Corrosion-of-Duplex-Stainless-Steels-in-Seawater-Wall%C3%A9n-Ab/6bcc0540b37ff541f0990657c5ad2047c0320717 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Shone, E.B.; Idrus, A.Z. The Performance of Selected Stainless Steels in Tropical and Temperate Seawater. In Progress in the Understanding and Prevention of Corrosion 2; International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA): London, UK, 1993; pp. 989–996. [Google Scholar]

- Féron, D. Marine Corrosion of Stainless Steels: Testing, Selection, Experience, Protection and Monitoring; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-429-60580-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, P.; Malpas, R.E.; Shone, E.B. Corrosion of Stainless Steels in Natural, Transported, and Artificial Seawaters. Br. Corros. J. 1988, 23, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | Designation * | Surface Finish | PREN ** | Typical Chemical Composition, % by Mass | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Cr | Ni | Mo | N | Other | ||||

| 1.4404 | Austenitic 316L | 2B | 24 | 0.02 | 17.2 | 10.1 | 2.1 | - | - |

| 1.4362 | EDX 2304 | 2E Pro | 28 | 0.02 | 23.8 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 0.18 | Cu: 0.3 |

| 1.4662 | LDX 2204 | 2E Pro | 34 | 0.02 | 24.0 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 0.27 | Mn: 3.0, Cu: 0.40 |

| 1.4462 | DX 2205 | 2E Pro | 35 | 0.02 | 22.4 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 0.17 | - |

| 1.4410 | SDX 2507 | 2E Pro | 43 | 0.02 | 25.0 | 7.0 | 4.0 | 0.27 | - |

| Zone | Grade | Corrosion Performance, Max. Depth of Corrosion Attack (Number of Attacks) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitting Corrosion | Crevice Corrosion | |||||

| CrevCorr | Sample Holder (4 Holders) | |||||

| Front Side | Back Side | Front Side | Back Side | |||

| Atmospheric | EN 1.4404 | 110 (>20p) | 90 µm | 90 µm | 80 µm (2C) | 230 µm (2C) |

| Splash | EN 1.4404 (1 year) | 30 µm (5p) | 90 µm | 50 µm | N/A | N/A |

| EN 1.4362 | <25 µm | 40 µm | 100 µm (4C) | 70 µm (4C) | ||

| EN 1.4662 | - | <25 µm | 25 µm | 60 µm (2C) | 30 µm (2C) | |

| EN 1.4462 | - | <25 µm | 30 µm | 50 µm (1C) | 40 µm (1C) | |

| EN 1.4410 | - | - | - | - | 25 µm (1C) | |

| Tidal | EN 1.4362 | - | <25 µm | - | 50 µm (3C) | 25 µm (2C) |

| EN 1.4662 | - | - | - | <25 µm | <25 µm | |

| EN 1.4462 | - | - | - | <25 µm | 30 µm (1C) | |

| EN 1.4410 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Immersed | EN 1.4362 | - | - | 30 µm | 1200 µm (3C) | 1200 µm (3C) |

| EN 1.4662 | - | - | <25 µm | <25 µm | <25 µm | |

| EN 1.4462 | - | - | - | <25 µm | <25 µm | |

| EN 1.4410 | - | - | - | <25 µm | <25 µm | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosseinpour, S.; Mameng, S.H.; Almen, M.; Liimatainen, M. Field Exposure of Duplex Stainless Steel in the Marine Environment: The Impact of the Exposure Zone. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040063

Hosseinpour S, Mameng SH, Almen M, Liimatainen M. Field Exposure of Duplex Stainless Steel in the Marine Environment: The Impact of the Exposure Zone. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2025; 6(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosseinpour, Saman, Sukanya Hägg Mameng, Marie Almen, and Mia Liimatainen. 2025. "Field Exposure of Duplex Stainless Steel in the Marine Environment: The Impact of the Exposure Zone" Corrosion and Materials Degradation 6, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040063

APA StyleHosseinpour, S., Mameng, S. H., Almen, M., & Liimatainen, M. (2025). Field Exposure of Duplex Stainless Steel in the Marine Environment: The Impact of the Exposure Zone. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 6(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040063