1. Introduction

Corrosion, a surface-driven process, poses significant challenges across industries, from infrastructure to biomedical applications. Generally, corrosion initiates at the metal–electrolyte interface, making surface tracking and real-time monitoring critical for understanding its mechanisms. While attempts to perform in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) are growing fast (despite the challenges), traditional ex situ techniques—optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), TEM, and spectroscopy—provide post-exposure snapshots but lack the ability to capture dynamic corrosion processes in aqueous environments. Additionally, transferring samples during ex situ characterization introduces artifacts that hinder accurate identification of corrosion initiation sites and may alter the composition of corrosion products, potentially misleading the interpretation of corrosion mechanisms. In situ visualization of active corrosion remains a key research goal, as it enables direct observation of surface reactions and electrochemical heterogeneity. Atomic force microscopy (AFM), a subset of scanning probe microscopy (SPM), addresses these challenges with its nanoscale resolution and ability to operate in liquid environments. AFM tracks topographical changes and electrochemical activity at the metal–electrolyte interface, offering insights unattainable by ex situ methods. This becomes even more powerful when AFM is combined with complementary characterization techniques.

This review, building on over a decade of corrosion and AFM expertise at KTH with collaborators Christofer Leygraf and Jinshan Pan, synthesizes key findings from in situ AFM studies and advanced data analysis. It highlights mechanistic insights into corrosion initiation and propagation, showcases applications across diverse materials, and proposes future directions for integrating AFM with emerging technologies to advance corrosion research. AFM’s high-resolution topographical imaging has proven invaluable in tracking the early morphological changes that accompany corrosion processes. Line profile analyses of surfaces revealed characteristic trenching patterns and pit nucleation around reactive intermetallic particles (IMPs), offering direct visual and quantitative evidence of localized material loss in aluminum alloys.

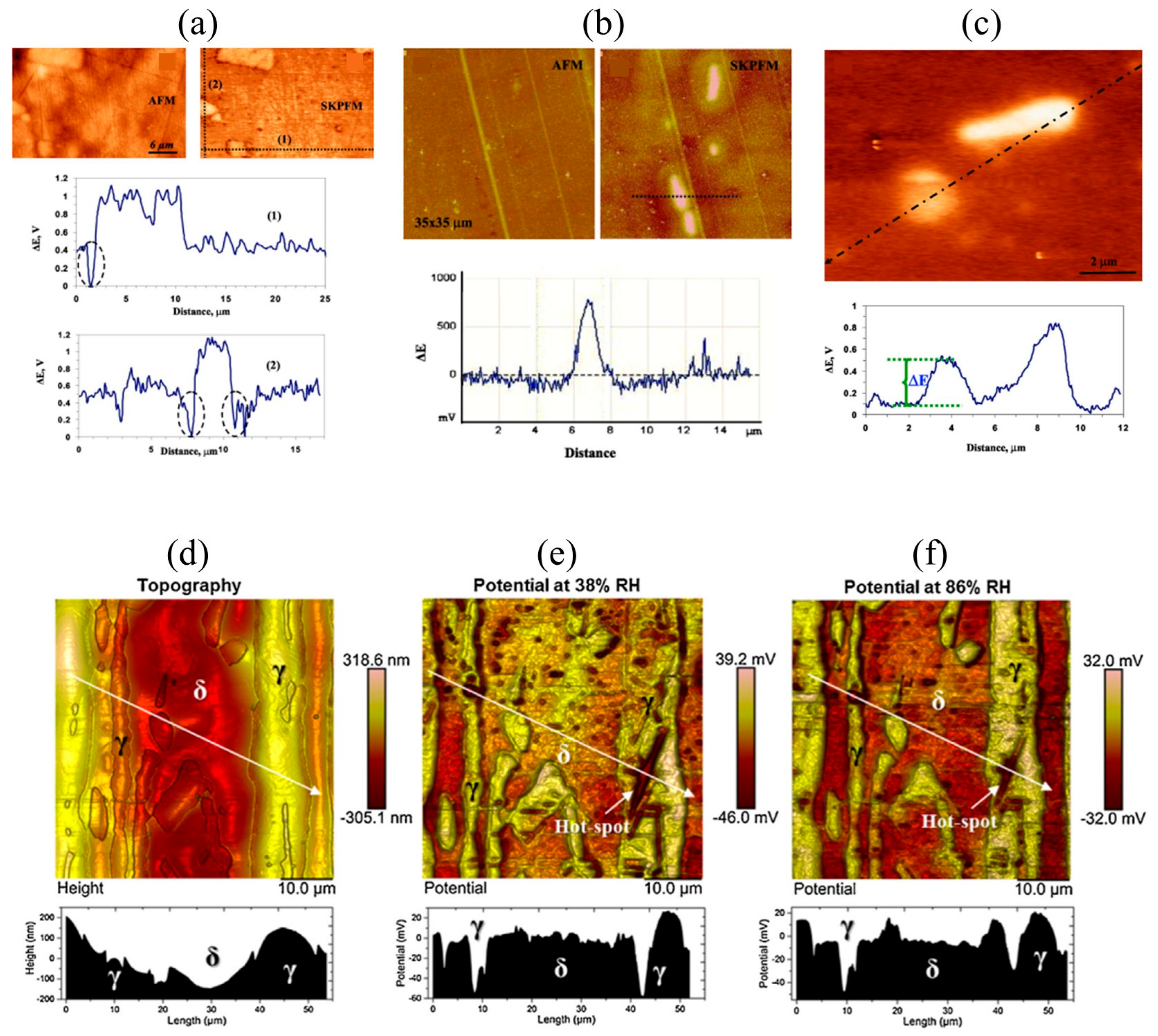

The application of AFM in corrosion science has significantly enhanced the mechanistic understanding of localized corrosion, particularly in aluminum alloys such as EN AW-3003. J. Pan and C. Leygraf at KTH studied the effect of intermetallic particles on localized corrosion of aluminum alloys using ex situ SKPFM and in situ AFM [

1,

2]. The dual approach allowed direct correlation of Volta potential distributions with IMP corrosion activity, especially in chloride environments. As illustrated in

Figure 1a–c SKPFM analyses revealed that larger constituent IMPs—typically Fe- and Si-rich phases such as Al(Mn,Fe)Si (identified by SEM-EDS analysis)—exhibited significantly higher Volta potentials than the aluminum matrix, acting as cathodic sites. In contrast, nanoscale dispersoids (<0.5 µm), such as Al

12Mn

3Si, showed negligible Volta potential differences and minimal electrochemical reactivity. It should be emphasized that the Volta potentials measured by SKPFM are relative values, referenced to the probe work function, and should be interpreted in terms of potential differences rather than absolute corrosion potentials. In situ AFM observations confirmed that corrosion initiated at the boundaries of micrometer-sized IMPs through micro-galvanic interactions, leading to localized anodic dissolution and trench formation. The boundary regions, where Volta potential minima were observed, were identified as critical weak points for corrosion initiation [

2].

In another study, Örnek et al. [

3] conducted several investigations on grade 2205 DSS to understand its corrosion behavior. In 2015, they explored how Volta potential differences between ferrite and austenite phases—measured by SKPFM—correlated with strain localization, revealing potential differences of 70–90 mV that drove selective ferrite dissolution in annealed DSS, while cold-rolled DSS showed localized pitting in austenite linked to strain-induced potential hotspots (

Figure 1d–f). The following year, they combined EBSD and SKPFM to characterize microstructural features in aged DSS, identifying Cr

2N, r-phase, and v-phase as cathodic sites that promoted ferrite corrosion [

4]. In 2019, further investigations by Rahimi et al. [

5] using SKPFM and STEM-EDS confirmed the higher nobility of ferrite, with a Volta potential difference of approximately

due to enrichment in Mo, W, and Cr. Mott-Schottky analysis also revealed the presence of p- and n-type layers within the passive film on the different phases.

A recent study examined how grain boundary chemistry and precipitate structure affect intergranular corrosion in Cu- and Zn-doped Al-Mg-Si alloys, with STEM-EDS showing Zn segregation at grain boundaries that enhanced corrosion susceptibility [

6]. Statistical AFM analysis was also suggested to quantify precipitate-driven corrosion more precisely, providing deeper mechanistic insights into the impact of impurities in recycled alloys.

Research on martensitic stainless steels processed by quenching and partitioning employed SKPFM and SECM to detect pit initiation at MnS and TiN inclusions [

7]. The researchers observed a Volta potential difference of approximately 40 mV between inclusions and the matrix, which drove selective dissolution at their interfaces, emphasizing the critical role of inclusions in localized corrosion.

Despite these advances, a complete mechanistic picture requires further integration of AFM with complementary techniques. Overall, AFM—especially when integrated with SKPFM—serves not only as a topographical imaging tool but also as a powerful platform for electrochemical corrosion analysis. Its ability to resolve sub-micrometer activity makes it indispensable for dissecting microstructural influences on corrosion initiation. However, the results remain largely qualitative and highlight the need to refine quantitative descriptors and expand temporal resolution. In other words, conventional AFM analysis—reliant on one-dimensional line profiles—is insufficient for capturing the spatial extent, lateral heterogeneity, or mechanistic details of corrosion. Advanced data analysis techniques—such as power spectral density (PSD), SKPFM, multimodal Gaussian histograms, and statistical roughness quantification—offer a multidimensional perspective, enabling quantitative correlations between microstructure, surface properties, and corrosion behavior. The following section briefly reviews PSD, multimodal Gaussian histograms, and statistical roughness quantification.

3. Applications of Advanced AFM and SKPFM in Corrosion Science

Advanced AFM and SKPFM have emerged as cornerstone techniques in corrosion science, offering unparalleled insights into the nanoscale electrochemical and topographical characteristics of material surfaces. By employing methods such as PSD, multimodal Gaussian histograms, and statistical roughness quantification, these techniques surpass the limitations of traditional line profile analysis, which provides only one-dimensional data and fails to capture the complex heterogeneity and dynamic electrochemical behavior of corroding surfaces. Advanced AFM and SKPFM enable researchers to map surface potential variations, identify corrosion initiation sites, and correlate microstructural features with corrosion susceptibility across diverse material systems. These methods are often integrated with complementary techniques, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM), to provide a comprehensive understanding of corrosion mechanisms. The following sections categorize these applications into distinct material systems and phenomena, detailing key studies, their methodologies, findings, and the specific advantages of advanced AFM techniques over conventional line profiles. Each section emphasizes the transformative impact of these methods in advancing corrosion science and material design.

3.1. Dissimilar Metal Welds and Joints

Dissimilar metal welds and joints, such as those combining aluminum, copper, titanium, and steel, are critical in industries like aerospace, automotive, and marine engineering, where they enable the integration of complementary material properties, such as lightweight strength and corrosion resistance. However, the welding process—whether through friction stir welding (FSW), solid-state welding, or other methods—introduces microstructural heterogeneity, including intermetallic compounds (IMCs) and phase boundaries, which often act as galvanic corrosion hotspots. Advanced AFM and SKPFM techniques have been pivotal in characterizing these interfaces, mapping electrochemical activity with nanoscale precision, and providing quantitative data to guide the development of corrosion-resistant welds. By resolving Volta potential differences and roughness variations, these methods reveal the mechanisms driving localized corrosion and inform strategies to mitigate degradation in harsh environments.

Figure 2a presents the AFM and SKPFM results from a multimodal study by Sarvghad-Moghaddam et al. [

8] on friction stir welded aluminum–copper joints, which are prone to galvanic corrosion due to the electrochemical potential difference between the two metals. The interfacial regions were comprehensively characterized using SEM-EDS, AFM, SKPFM, and optical microscopy. SKPFM revealed that CuAl

2 IMCs exhibited Volta potentials 200–300 mV higher than the Al-rich matrix, identifying them as micro-galvanic sites. Multimodal Gaussian histograms quantified the Volta potential distributions, showing that corrosion preferentially initiated at IMC boundaries where potential differences (ΔV) exceeded 250 mV. Post-immersion in 3.5% NaCl, dynamic electrochemical shifts were observed, with copper becoming anodic due to the formation of a passive oxide layer on titanium, a phenomenon captured by SKPFM’s real-time mapping capabilities. The study highlighted the role of microstructural heterogeneity, driven by tool pin and shoulder effects during FSW, in promoting localized corrosion in Al-rich zones adjacent to dispersed Cu particles. This work demonstrated SKPFM’s ability to provide spatially resolved electrochemical data, critical for understanding corrosion initiation in complex weld interfaces.

In 2016, Davoodi et al. [

9] conducted a comprehensive investigation into the microstructure and corrosion behavior of the interfacial region in dissimilar friction stir welded AA5083 and AA7023 aluminum alloys. This study employed a suite of techniques, including SEM-EDS, optical microscopy, potentiodynamic polarization, EIS, AFM, and SKPFM, to investigate the corrosion behavior of the weld interface. An inhomogeneous borderline rich in Al-Mg-Zn precipitates was identified as a galvanic cell, with SKPFM detecting Volta potential differences of 700–800 mV between AA5083 and AA7023 (

Figure 2b). These Volta potential mappings were performed in air at room temperature under a controlled relative humidity of 35 ± 2%. The potentials represent relative values referenced to the probe work function, and the observed differences (≈700–800 mV) correlate directly with the micro-galvanic interactions driving corrosion initiation at the weld interface. Corrosion initiated at Cu/Si-rich IMPs on the AA7023 side and Al-Mn-Fe particles on the AA5083 side, driven by these significant potential gradients. A follow-up study in 2018 applied PSD and histogram analysis of AFM and SKPFM images to quantitatively assess roughness and electrochemical variations at the AA7023/AA5083 interface [

10]. AA5083 exhibited uniform roughness and lower Volta potentials at high spatial frequencies, while AA7023 showed higher roughness and Volta potentials at low frequencies, correlating with corrosion susceptibility at the FSW interface. Gaussian and fast fourier transform (FFT) analyses provided quantitative insights into the corrosion extent at Al-Mn-Fe particles, highlighting the limitations of line profiles in capturing such complex surface dynamics.

In 2018, Rahimi et al. [

11,

12] conducted a detailed analysis of galvanic behavior in a solid-state welded Ti-Cu bimetal, focusing on how local intermetallic phases influence corrosion initiation. Using SKPFM, the researchers mapped Ti

2Cu, TiCu, and TiCu

4 IMCs as anodic sites, revealing Volta potential differences of approximately 400 mV compared to the surrounding matrix. Before immersion in 3.5% NaCl, the Cu side displayed higher nobility, indicating a greater corrosion susceptibility for titanium (

Figure 3a). However, after immersion, the development of a passive titanium oxide layer reversed this behavior, rendering copper anodic. Gaussian distribution and FFT analyses were applied to quantify the electrochemical activity in local melted and vortex zones, demonstrating SKPFM’s capability to monitor dynamic galvanic interactions. This work emphasized the need to account for both microstructural and electrochemical variables when designing dissimilar metal joints for harsh environments such as marine applications.

Okonkwo et al. [

13] conducted a microscale investigation on the galvanic corrosion behavior of low-alloy steel A508 joined with stainless steel 309L/308L weld overlays. Using a combination of optical microscopy, SEM, scanning vibrating electrode technique (SVET), and AFM, they identified MnS inclusions within the heat-affected zone (HAZ) as primary sites for pitting initiation. Microstructural transformation in the HAZ—from tempered bainite to a bainite–martensite mixture—was linked to increased corrosion susceptibility. Quantitative analysis through Gaussian distribution and fast Fourier transform (FFT) applied to AFM data allowed for precise assessment of localized corrosion (

Figure 3b). In a subsequent study, the same group introduced a novel approach to evaluate how variations in anode/cathode area ratios and microstructural differences influence galvanic corrosion [

14]. AFM-PSD results revealed that grain-refined areas and MnS inclusions exhibited the highest electrochemical activity. They further observed that reducing the anode-to-cathode area ratio significantly intensified local corrosion current density, highlighting the critical role of microstructural features in the corrosion behavior of dissimilar welds.

Compared to traditional line profiles, SKPFM offers several significant advantages for analyzing weld interfaces. First, it enables high-resolution electrochemical mapping by providing spatially resolved Volta potential data. This capability allows for the identification of micro-galvanic sites, such as IMCs and IMPs, and the detection of dynamic electrochemical shifts like nobility inversions—phenomena that line profiles, limited by their one-dimensional and non-electrochemical nature, cannot capture. Second, PSD analysis complements this by offering a comprehensive evaluation of surface roughness in relation to corrosion susceptibility across a range of spatial frequencies. This multi-scale, quantitative insight reveals weld interface heterogeneity far more effectively than the limited topographic information available from line profiles. Finally, in situ SKPFM facilitates real-time monitoring of electrochemical activity, making it possible to observe transient behaviors such as galvanic polarity shifts and the early stages of corrosion at weld interfaces. These capabilities are critical for improving weld design and enhancing corrosion resistance.

3.2. Biomedical Alloys and Implants

Biomedical alloys, such as titanium (Ti-6Al-4V), cobalt–chromium–molybdenum (CoCrMo), and magnesium (Mg) alloys, are essential for implants and medical devices due to their mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and corrosion resistance. However, their performance in physiological environments is influenced by complex interactions with proteins, electrolytes, and oxidative species, which can accelerate corrosion and biodegradation. Advanced AFM and SKPFM techniques have been critical in studying these interactions at the nanoscale, providing detailed insights into protein adsorption, passive film stability, and electrochemical dynamics. These methods enable researchers to correlate surface potential changes and topographic features with corrosion behavior, informing the design of durable and biocompatible implants.

In 2015, Nakhaie et al. [

15] conducted a comprehensive investigation into how cold plastic deformation affects the passive behavior of Ti-6Al-4V alloy, utilizing both electrochemical methods and localized surface probing techniques. Using potentiodynamic polarization, Mott-Schottky analysis, AFM, and SKPFM, the study found that cold working increased passive current density and introduced defects into the passive film, correlating with increased bulk crystal defects. SKPFM revealed that the α-phase had a Volta potential 38.6 mV lower than the β-phase, making it more vulnerable to corrosion in aggressive environments (

Figure 4). Mott-Schottky analysis confirmed the n-type semiconducting behavior of the passive layer and showed that higher film formation potentials reduced donor density, mitigating some effects of cold work. In 2021, Rahimi et al. [

16] explored how exposure to hydrogen peroxide influences the adsorption behavior of bovine serum albumin on Ti-6Al-4V alloy surfaces, using scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy to assess the electrochemical implications. SKPFM showed that hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) disrupted bovine serum albumin (BSA) adsorption, leading to a thinner, discontinuous protein layer and a reduced surface potential, which increased corrosion rates. Another 2021 study explored TiO

2 nanotube growth on Ti-6Al-4V, revealing faster oxide formation on β-phases due to higher Al/V content [

17]. AFM quantified morphological differences through statistical roughness analysis, highlighting the role of phase composition in oxide growth kinetics.

In 2022, Rahimi et al. [

18] examined the effect of albumin protein adsorption on the localized corrosion behavior of CoCrMo implant alloy, utilizing advanced surface characterization techniques to reveal electrochemical changes at the microscale. SKPFM revealed that BSA adsorption formed clusters with lower surface potentials, accelerating corrosion at protein/substrate interfaces. Increasing BSA concentrations from 0.5 to 2 g/L and applying overpotentials of +300 mV (vs. Ag/AgCl) enhanced protein coverage and corrosion rates, as confirmed by field emission SEM. Mott–Schottky analysis indicated increased space charge capacitance in the presence of BSA, facilitating metal ion release. This study highlighted SKPFM’s ability to map nanoscale electrochemical interactions at protein-metal interfaces, critical for understanding corrosion in biomedical implants exposed to physiological media.

In 2024, Imani et al. [

19] explored the early-stage in vitro biodegradation behavior of WE43 magnesium alloy in simulated body fluids, using AFM and SKPFM to assess the impact of albumin protein on surface degradation and electrochemical response. This study highlighted SKPFM’s ability to map nanoscale electrochemical interactions at protein-metal interfaces, critical for understanding corrosion in biomedical implants exposed to physiological media. It is important to distinguish between the short-term effects of albumin adsorption—occurring within minutes to hours—which primarily alter surface potential and passive layer uniformity, and the longer-term protein–ion complexation processes that progressively modify surface chemistry and the apparent electrostatic surface potential (ESP). These time-dependent interactions collectively influence the corrosion behavior of implant materials in physiological environments. SKPFM detected a 10–20 nm BSA nanolayer with aggregated and fibrillar morphology in Hanks’ solution, reducing surface potential by 52 mV and increasing biodegradation rates. In contrast, BSA in NaCl solution inhibited corrosion, increasing impedance from 49 to 97 Ω·cm

2 and reducing electrochemical current noise (ECN). Statistical roughness analysis quantified film morphology, revealing a dual-mode biodegradation behavior influenced by electrolyte composition. This study underscored the role of protein-electrolyte interactions in modulating Mg alloy degradation, critical for orthopedic and cardiovascular applications.

The use of SKPFM in conjunction with AFM topography, Mott-Schottky analysis, and SEM offers a robust approach for understanding surface interactions in physiological environments. SKPFM enables high-resolution mapping of potential changes induced by protein adsorption, revealing electrochemical dynamics at the nanoscale that traditional line profiles cannot capture. The integration of multiple characterization techniques provides a multidimensional view of the surface, linking morphological features with corrosion and biodegradation mechanisms. Furthermore, roughness metrics and power spectral density analysis deliver quantitative assessments of topographic variations, allowing for detailed evaluation of protein film formation and passive layer integrity.

3.3. Protective Coatings and Superhydrophobic Surfaces

Protective coatings, including superhydrophobic surfaces and thin dense chromium (TDC) coatings, are designed to enhance corrosion resistance by modifying surface morphology and electrochemical properties. These coatings are critical in applications ranging from marine engineering to industrial machinery, where exposure to aggressive environments like chloride solutions is common. Advanced AFM and SKPFM techniques have been instrumental in optimizing coating design by quantifying nanoscale roughness, identifying defect-driven galvanic cells, and correlating surface properties with corrosion performance. These methods provide detailed insights into the interplay between microstructure, surface potential, and corrosion resistance, guiding the development of durable coatings.

Figure 4.

(

a) Volta potential maps and corresponding deconvoluted histograms of Ti-6Al-4V alloy under different deformation states (solution treated, 2% cold worked, and 5% cold worked), showing phase-dependent potential distributions (Solver Next AFM; PtIr (25 nm)-coated Sb-doped Si tip; dual-scan mode; lift 40–60 nm; 25 ± 1 °C; RH 35 ± 2%; 256 × 256 px, 0.3 Hz) (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [

15]. 2015, NACE). (

b) Surface topography, potential histograms, and 1D PSD analysis of Ti-6Al-4V alloy under different surface conditions (Digital Instruments Nanoscope IIIa; PtIr-coated Si tip; dual-scan mode; lift ≈ 100 nm; 27 °C; RH ≈ 28%; 512 × 512 px, 0.2 Hz; in situ AFM in PBS + BSA at +200 mV vs. Ag/AgCl for 1 h at 37 °C) (Reprinted from Ref. [

16] under a CC BY 4.0 license). (

c) AFM and SKPFM images of an as-polished Mg-based alloy with the associated surface potential distribution histogram, highlighting variations linked to microstructural features (Nanoscope IIIa AFM; PtIr-coated Si tip; dual-scan mode; lift ≈ 100 nm; 27 °C; RH ≈ 28%; 512 × 512 px, 0.2 Hz) (Reprinted from Ref. [

20] under a CC BY 4.0 license).

Figure 4.

(

a) Volta potential maps and corresponding deconvoluted histograms of Ti-6Al-4V alloy under different deformation states (solution treated, 2% cold worked, and 5% cold worked), showing phase-dependent potential distributions (Solver Next AFM; PtIr (25 nm)-coated Sb-doped Si tip; dual-scan mode; lift 40–60 nm; 25 ± 1 °C; RH 35 ± 2%; 256 × 256 px, 0.3 Hz) (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [

15]. 2015, NACE). (

b) Surface topography, potential histograms, and 1D PSD analysis of Ti-6Al-4V alloy under different surface conditions (Digital Instruments Nanoscope IIIa; PtIr-coated Si tip; dual-scan mode; lift ≈ 100 nm; 27 °C; RH ≈ 28%; 512 × 512 px, 0.2 Hz; in situ AFM in PBS + BSA at +200 mV vs. Ag/AgCl for 1 h at 37 °C) (Reprinted from Ref. [

16] under a CC BY 4.0 license). (

c) AFM and SKPFM images of an as-polished Mg-based alloy with the associated surface potential distribution histogram, highlighting variations linked to microstructural features (Nanoscope IIIa AFM; PtIr-coated Si tip; dual-scan mode; lift ≈ 100 nm; 27 °C; RH ≈ 28%; 512 × 512 px, 0.2 Hz) (Reprinted from Ref. [

20] under a CC BY 4.0 license).

![Cmd 06 00058 g004 Cmd 06 00058 g004]()

Rahimi et al. [

21,

22] investigated how modifying the surface morphology of electrodeposited superhydrophobic nickel coatings can enhance corrosion resistance (

Figure 5). Using a combination of AFM, SEM-EDS, and electrochemical measurements, the study explored the relationship between surface structure and protective performance, providing valuable insights into the design of corrosion-resistant coatings. AFM revealed that boric acid promoted the formation of micro-nano cone structures, achieving contact angles > 150° and reducing corrosion current by a factor of 10. PSD and histogram analysis confirmed screw dislocation-driven growth, with a contact angle of 156° correlating with enhanced hydrophobicity. A related study examined the behavior of water and saline droplets during icing and melting cycles on superhydrophobic surfaces [

23]. The findings demonstrated that superhydrophobic nickel films significantly delayed freezing—up to 110 min—compared to just 34 min for bright nickel surfaces. This enhanced performance was attributed to the broader roughness distribution of the superhydrophobic films across all spatial frequencies. SEM-EDS complemented AFM by visualizing structural changes and organic contaminants contributing to hydrophobicity.

The influence of an inorganic corrosion inhibitor on the electrochemical behavior of superhydrophobic micro/nano-structured Ni films in 3.5% NaCl solution was investigated by Noorbakhsh-Nezhad et al. [

24]. AFM quantified a root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of 14.4 nm and skewness of 0.21, correlating with 80% corrosion inhibition efficiency when 0.1 M sodium molybdate was used as an inhibitor. EIS confirmed that the films acted as non-ideal capacitors, enhancing durability in aggressive NaCl solutions. The study highlighted the role of surface morphology in improving corrosion resistance, with AFM providing detailed topographic data.

In a study on the microstructural, nanomechanical, and tribological properties of thin dense chromium coatings, AFM revealed a dense, nodular microstructure with 3.6 μm nodules and 227 nm grains [

25]. SKPFM showed high surface potentials at nodule boundaries, which decreased post-NaCl exposure due to the formation of a stable Cr

3+ oxide layer, as confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The study on advanced nodular thin dense chromium coating with superior corrosion resistance reported a non-conductive bilayer oxide with a charge transfer resistance of 1.01 MΩ, significantly impeding Cl

− diffusion [

26]. Statistical AFM quantified the microstructural contributions to corrosion resistance, demonstrating the coating’s suitability for rolling bearing applications.

The study on the effect of phosphorous content on the microstructure and localized corrosion of electroless nickel-coated copper investigated NiP coatings with varying phosphorous (P) content (8.3–13.2 wt%) [

27]. AFM revealed that high-P coatings (13.2 wt%) exhibited superior corrosion resistance due to their amorphous structure, while low-P coatings (8.3 wt%) showed localized corrosion at nodule boundaries. PSD and roughness analysis quantified microstructural effects, correlating crystallinity variations with electrochemical performance in 3.5% NaCl solution (

Figure 6).

PSD and statistical roughness analysis offer detailed quantification of coating morphology across multiple spatial scales, enabling optimization of surface features for improved corrosion resistance, which goes well beyond the qualitative information provided by traditional line profiles. SKPFM plays a crucial role in detecting defect-driven galvanic cells, such as those at nodule boundaries, with nanoscale precision, facilitating targeted enhancements in coating durability under aggressive environmental conditions. Additionally, combining SKPFM with techniques like EIS, XPS, and SEM allows for a comprehensive correlation between electrochemical behavior, chemical composition, and surface potential variations, thereby improving the understanding of corrosion performance and inhibitor effectiveness.

3.4. Atmospheric and Localized Corrosion

Atmospheric and localized corrosion, driven by chloride-laden electrolytes or droplet-based exposure, are significant challenges in marine, aerospace, and industrial applications. These processes often involve dynamic electrochemical changes and pit initiation, which require real-time monitoring and nanoscale resolution to understand fully. In situ SKPFM and statistical AFM techniques have enabled researchers to track transient corrosion phenomena, quantify environmental effects on corrosion kinetics, and identify regions susceptible to pit initiation, providing critical insights for corrosion prevention.

A time-lapse SKPFM investigation on sensitized AA5083 aluminum alloy demonstrated that Mg

2Si particles undergo nobility inversion from cathodic to anodic behavior during chloride exposure in thin-film electrolytes at 20–85% relative humidity [

29]. Aluminides, both with and without silicon, functioned as dominant cathodic sites, while the surrounding alloy matrix in close proximity exhibited a shift in Volta potential toward that of the aluminides—a phenomenon referred to as “nobility adoption” (

Figure 7). This reduced localized corrosion by altering anode/cathode ratios dynamically, as quantified by SKPFM’s real-time potential mapping.

In a study about monitoring atmospheric corrosion under multi-droplet conditions, AFM combined with custom-designed electrical resistance (ER) sensors was used to quantify corrosion kinetics, enabling precise tracking of localized degradation [

30]. Power-law droplet size distributions showed decreasing height and expanding width with progressive drying, with NaCl and surface roughness increasing corrosion rates. A strong correlation between corrosion rate and relative humidity was established using Savitzky–Golay filtering, highlighting the influence of droplet-based electrolyte conditions on corrosion kinetics.

In another study about atmospheric corrosion of iron under single droplets, AFM and a micro-sized three-electrode cell were employed to investigate the effects of droplet volume (1.5–5 μL) and NaCl concentration (0.01–0.2 M) on localized corrosion behavior [

31]. Smaller droplets (1.5 μL) with higher NaCl concentrations exhibited lower noise resistance (R

n) and polarization resistance (R

p), enhancing localized corrosion due to chloride dominance over oxygen diffusion. Statistical AFM analysis provided topographic insights into droplet-induced corrosion, complementing electrochemical measurements.

In situ SKPFM enables real-time electrochemical monitoring by capturing dynamic potential changes—such as nobility inversions—during corrosion processes, offering insights that static line profiles cannot provide. Additionally, statistical roughness analysis and power spectral density methods allow for quantitative assessment of corrosion kinetics, linking topographic evolution with environmental variables like relative humidity and chloride concentration. This integrated approach delivers a more comprehensive understanding of corrosion dynamics. Moreover, atomic force microscopy aids in indicating pit initiation susceptibility by mapping variations in surface roughness and local electrochemical activity, thereby enabling probabilistic modeling of localized corrosion initiation beyond the limitations of traditional, one-dimensional data.

3.5. Nanoparticles and Biointerfaces

Nanoparticles and biointerfaces—particularly in biomedical applications—are susceptible to corrosion and biodegradation, which are influenced by protein interactions and physiological environments. These interactions can affect nanoparticle stability, toxicity, and functionality, making their characterization critical for safe biomedical applications. AFM and SKPFM have been essential in quantifying electrochemical and morphological changes at the nanoscale, providing insights into protein–nanoparticle interactions and biodegradation mechanisms.

Rahimi et al. [

32] investigated the biodegradation behavior of oxide nanoparticles in apoferritin protein media using a systematic electrochemical approach. SKPFM showed that a 5 nm bismuth ferrite (BFO) shell on cobalt ferrite (CFO) nanoparticles increased surface potential, reducing anodic current density and biodegradation rates. Potentiodynamic polarization measurements confirmed lower electrochemical activity in CFO-BFO due to higher flat band potential and lower donor density, highlighting the protective role of the BFO shell in protein-containing media.

In a study examining the physicochemical changes in apoferritin protein during the biodegradation of magnetic metal oxide nanoparticles, AFM and SKPFM were used to observe significant alterations during the degradation of CoFe

2O

4 nanoparticles [

33]. Apoferritin’s characteristic hole (1.35 nm) vanished after 48 h, with protein height increasing from 3.5 to 7.5 nm due to hole filling by heterogeneous oxides (γ-Fe

2O

3, Fe

3O

4, CoO, etc.) (

Figure 8). This led to a significant increase in surface potential, accelerating biodegradation through enhanced electrostatic interactions. Statistical analysis quantified these morphological and electrochemical changes, providing insights into nanoparticle toxicity and protein deformation.

Using AFM, researchers investigated the mechano-bactericidal properties of Psalmocharias cicada wings by quantifying nanopillar skewness and kurtosis on the wings of Psalmocharias querula (PQ) and P.akesensis (PA) [

34]. PQ’s nanopillars exhibited higher bactericidal efficiency due to effective bacterial membrane penetration, as confirmed by colony-forming unit (CFU) counts and AFM force measurements. PSD and histogram analysis correlated topographic features with antibacterial performance, offering insights into bioinspired surface design.

SKPFM offers nanoscale electrochemical mapping by quantifying interactions at nanoparticle–biointerface boundaries with high resolution, capturing protein-induced potential changes essential to understanding biodegradation—details that line profiles cannot reveal. AFM topography complements this by tracking nanoscale morphological evolution, such as protein hole filling or changes in nanopillar geometry, providing comprehensive insights into biointerface dynamics and nanoparticle stability. Additionally, statistical tools like power spectral density and histogram analysis enable quantitative assessment of both electrochemical and topographic variations, allowing precise correlation with biodegradation rates and toxicity, far exceeding the limited information available from traditional line profiles.

3.6. Other Material Systems

Advanced AFM and SKPFM techniques have been applied to a diverse array of material systems, including nickel–aluminum bronze, aluminum alloys, martensitic stainless steels, and shape memory alloys. These studies highlight the versatility of these methods in addressing phase-specific corrosion, intergranular corrosion, and microstructural effects, providing a universal framework for corrosion analysis across industries like marine, aerospace, and biomedical engineering.

Nakhaie et al. [

35] investigated the corrosion initiation behavior of NiAl bronze in acidic media, focusing on the role of its constituent phases using SEM–EDS, AFM, and SKPFM techniques. SKPFM mapped anodic iron-rich β phases and cathodic copper-rich α phases, correlating Volta potentials with theoretical work functions to confirm β phases as primary corrosion initiation sites. SEM and AFM imaging provided complementary topographic data, highlighting the influence of microstructural phase distribution on localized corrosion susceptibility.

Investigations into additively manufactured superelastic NiTi alloy revealed, through SKPFM analysis, that martensitic regions acted as anodic sites in laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) samples, highlighting the influence of crystallographic texture on corrosion resistance [

36]. Optimizing LPBF parameters produced [001]-textured NiTi, eliminating martensite and reducing corrosion current by nearly two orders of magnitude, enhancing both corrosion resistance and superelastic performance (

Figure 9).

4. Emerging Techniques and Advantages in Nanoscale Corrosion Analysis Using Advanced AFM

As discussed in

Section 3, over the past decade, the evolution of advanced Atomic Force Microscopy techniques—such as Power Spectral Density analysis, Scanning Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy, multimodal Gaussian histogram evaluation, and statistical roughness quantification—has revolutionized the field of corrosion science. These methods have addressed the inherent limitations of traditional line profile analysis by providing spatially resolved, quantitative, and mechanistic insights at the nanoscale. Unlike conventional tools, these approaches can uncover early-stage corrosion phenomena by mapping surface heterogeneity, detecting micro-galvanic interactions, and capturing dynamic electrochemical behavior. Their effectiveness has been demonstrated across a wide array of materials, including aluminum–copper joints [

8], NiAl bronze [

35], dissimilar aluminum alloy welds (AA5083/AA7023) [

9,

10], Ti-6Al-4V [

15,

16,

17], duplex stainless steels [

3,

4], and superhydrophobic coatings [

21,

22,

23,

24]. A major advancement in recent research has been the integration of in situ AFM and SKPFM monitoring. This enables real-time imaging of corrosion events such as passive film breakdown, metastable pitting, and pit coalescence, particularly in chloride-rich environments. When combined with techniques like STEM-EDS, Mott-Schottky analysis, and SECM, these multimodal approaches yield comprehensive information that links microstructural, chemical, and electrochemical factors. For example, phase-specific corrosion activity in duplex stainless steels and intermetallic particle-driven degradation in aluminum alloys have been precisely characterized, offering a deeper understanding of material performance under corrosive conditions.

Recent advances in correlative microscopy have enabled nanoscale insights into corrosion processes by integrating AFM with complementary techniques such as Raman spectroscopy and TEM. In situ AFM–Raman systems allow simultaneous mapping of surface topography and chemical composition, which is critical for understanding passive film breakdown and localized corrosion initiation. For example, Casanova et al. demonstrated the activation of titanium in sulfuric acid using a combined AFM–Raman setup, revealing oxide dissolution and precipitation dynamics under electrochemical control [

37]. Similarly, Kreta et al. correlated AFM imaging with Raman spectroscopy to study corrosion of AA2024-T3 aluminum alloy, linking morphological changes to oxyhydroxide formation [

38]. AFM–TEM workflows have also been applied to stainless steels; for instance, Liu et al. integrated electrochemical AFM (EC-AFM) with TEM to quantify pit-growth kinetics and elucidate the transition between vertical and lateral dissolution under varying potentials [

39]. These multimodal strategies represent a significant step toward real-time, nanoscale characterization of corrosion phenomena, bridging the gap between structural and chemical analysis.

Additionally, the incorporation of machine learning and AI into AFM data analysis is facilitating high-throughput corrosion assessment. These tools can process complex datasets from PSD and SKPFM measurements to identify patterns, classify corrosion-prone features, and develop data-driven probabilistic models that indicate initiation susceptibility and guide alloy design and surface treatments strategies [

40,

41,

42]. Such automation enhances the accuracy and efficiency of corrosion diagnostics while promoting data-driven optimization strategies [

43]. Crucially, these methods provide phase-specific electrochemical mapping at nanometer resolution, identifying localized Volta potential differences around inclusions, precipitates, and secondary phases [

44]. This enables identification of corrosion hot spots that were previously undetectable. Statistical roughness metrics and PSD analysis offer quantifiable data that correlate microstructural features with corrosion susceptibility, thereby informing strategies for alloy development, protective coating design, and welding interface optimization [

45]. The broader applicability of these techniques extends across industries and materials, including aerospace-grade aluminum alloys, marine steels, biomedical implants, and responsive smart coatings [

46]. They inform strategies such as minimizing intermetallic particle size, engineering passive layer chemistry, or designing bioinspired superhydrophobic surfaces [

47]. Collectively, this advanced AFM-based framework offers not only a mechanistic understanding of corrosion but also actionable insights for enhancing material durability in increasingly demanding environments.

For accurate and reproducible AM-KPFM corrosion measurements, several experimental parameters must be controlled and verified:

Environment control: Maintain stable relative humidity (typically 20–50%) and room temperature to minimize potential drift.

Lift height: Use 50–100 nm separation to balance spatial resolution and electrostatic decoupling.

Tip bias calibration: Apply bias of ±1–2 V and verify tip work function using a reference material.

Drift and artifact checks: Correct for lateral drift, flatten background topography, and validate tip condition before and after scanning.

Noise minimization: Employ low scan rates and shielded cabling to reduce electrostatic interference.

Data referencing: Interpret Volta potential values as relative potentials; reference to the probe work function.

Documentation: Record humidity, tip type, bias voltage, and lift height for reproducibility.

This checklist provides a concise guide to minimize measurement artifacts and ensure quantitative reliability in nanoscale electrochemical mapping.

6. Conclusions

This review has outlined recent advances in nanoscale corrosion characterization using AFM-based techniques and their integration with complementary methods, highlighting both the scientific insights gained and the challenges that remain.

This review has critically evaluated the transformative role of advanced AFM and SKPFM techniques in unraveling nanoscale corrosion phenomena. By moving beyond conventional line profile analysis, we highlighted how power spectral density (PSD), multimodal Gaussian fitting, statistical roughness quantification, and deconvolution approaches offer quantitative and spatially resolved insights into corrosion initiation, propagation, and microstructural influences. These methods have proven effective across diverse material systems, including dissimilar welds, biomedical implants, protective coatings, and nanoparticle–biointerfaces. Their integration with complementary techniques such as SEM-EDS, SECM, Mott–Schottky analysis, and in situ electrochemical methods enables a comprehensive, multi-modal understanding of localized corrosion mechanisms.

Advantages of results evaluation beyond line profiles in AFM & SKPFM for corrosion studies as summarized as below:

Comprehensive mapping: Full 2D and 3D evaluation of AFM and SKPFM images provides complete coverage of surface roughness and potential variations that cannot be captured by single line profiles.

Scale-resolved insights: Spectral analysis enables the separation of fine-scale and coarse-scale corrosion features, offering a clearer understanding of different degradation mechanisms.

Quantitative statistics: Population-based statistical analysis allows distinct identification and quantification of phases, oxides, and corrosion products within the scanned area.

Improved accuracy: Deconvolution techniques correct tip-induced artifacts, yielding truer representations of both morphology and local potential distributions.

Dynamic tracking: Time-lapse AFM and SKPFM imaging captures the evolution of transient corrosion processes, providing kinetic information at the nanoscale.

Mechanistic depth: Integration with complementary methods links structural, chemical, and electrochemical information, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of corrosion mechanisms.

Importantly, this review underscores that advanced AFM-based analysis serves as a diagnostic and probabilistic assessment platform for corrosion science—capable of identifying electrochemical hot spots, evaluating passive film stability, and providing indicators of initiation susceptibility that can guide the design of corrosion-resistant materials. While static AFM/SKPFM maps offer valuable spatial insights, quantitative corrosion rate evaluation requires complementary time-lapse or kinetic methods such as in situ SKPFM or ER-based multi-droplet monitoring. As the field evolves, the convergence of in situ AFM imaging, machine learning, and high-throughput data analysis will drive the next generation of corrosion diagnostics and materials development. The continued refinement and standardization of these approaches will be essential for ensuring reproducibility, cross-platform compatibility, and broader industrial application. While AFM and SKPFM provide valuable nanoscale insights, their results are influenced by factors such as tip–sample work function offset, environmental sensitivity, and surface-specific interactions. Careful calibration, humidity control, and drift correction are therefore essential to ensure data reliability and comparability across studies.