On the Effective Medium Theory for Silica Nanoparticles with Size Dispersion

Abstract

1. Introduction

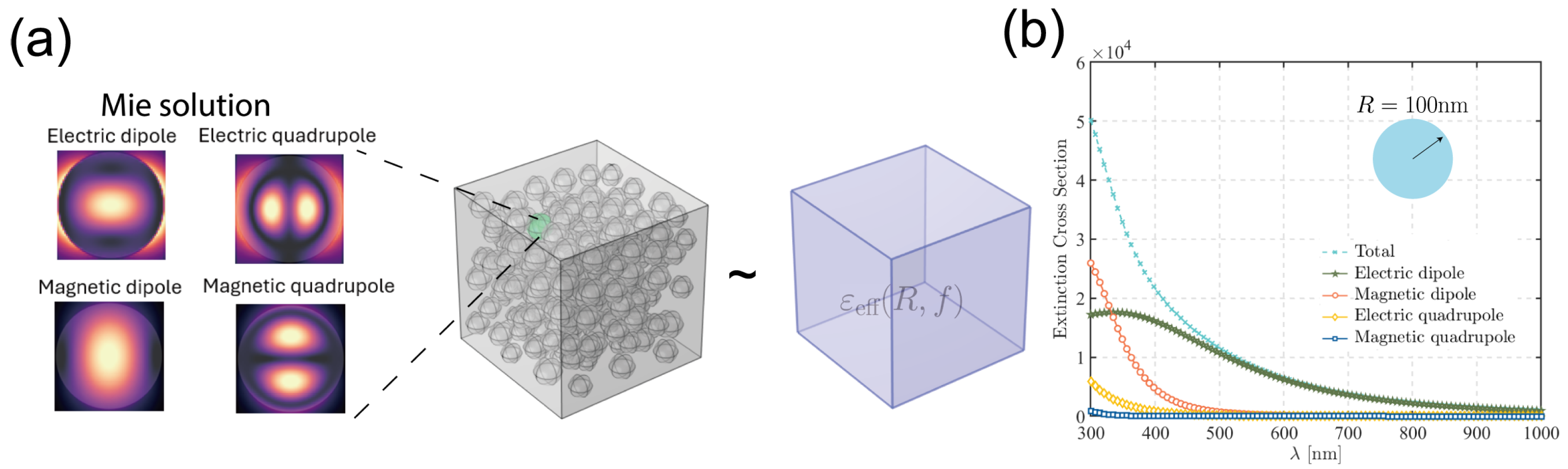

2. CM Relation and Mie Solutions

2.1. Foundation: The CM Relation and Its Limitations

- Higher-order Multipoles: Quadrupole, octupole, and higher-order modes contribute substantially to the scattering.

- Dynamic Depolarization: The incident field can no longer be considered uniform across the particle.

- Magnetic Response: Time-varying magnetic fields induce circulating currents, leading to a magnetic dipole response even in dielectric particles.

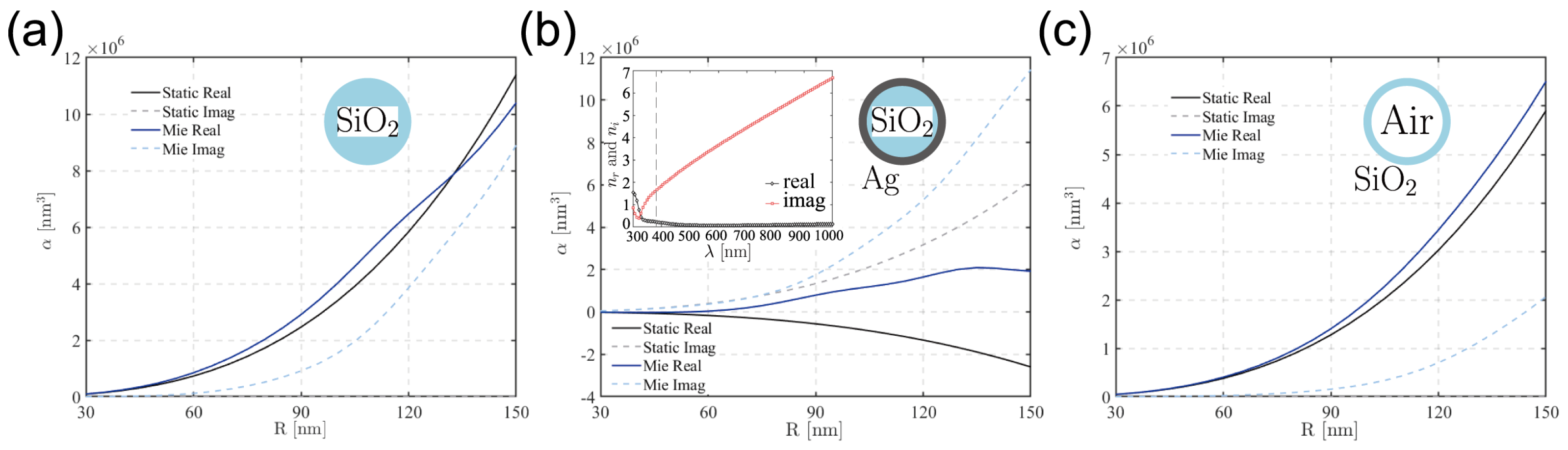

2.2. Mie Theory and the Effective Polarizability

2.3. Mie Coefficients for Different SNP Structures

- For a solid, homogeneous sphere (unshelled SNP) with refractive index , the coefficients are given by [19]Here, , , and and are the Riccati–Bessel functions, and , are the corresponding derivatives.

- For a core–shell sphere, the expressions for the Mie coefficients and are more complex, accounting for the boundary conditions at both the core–shell and shell–medium interfaces. They are functions of the core radius and dielectric constant , the shell radius and dielectric constant , and the host dielectric constant , which are given aswhere with and the refractive index and the radius of the shell, is the Bessel function of the second kind, and , are defined as

2.4. Incorporating Polydispersity and the Final EMT Formula

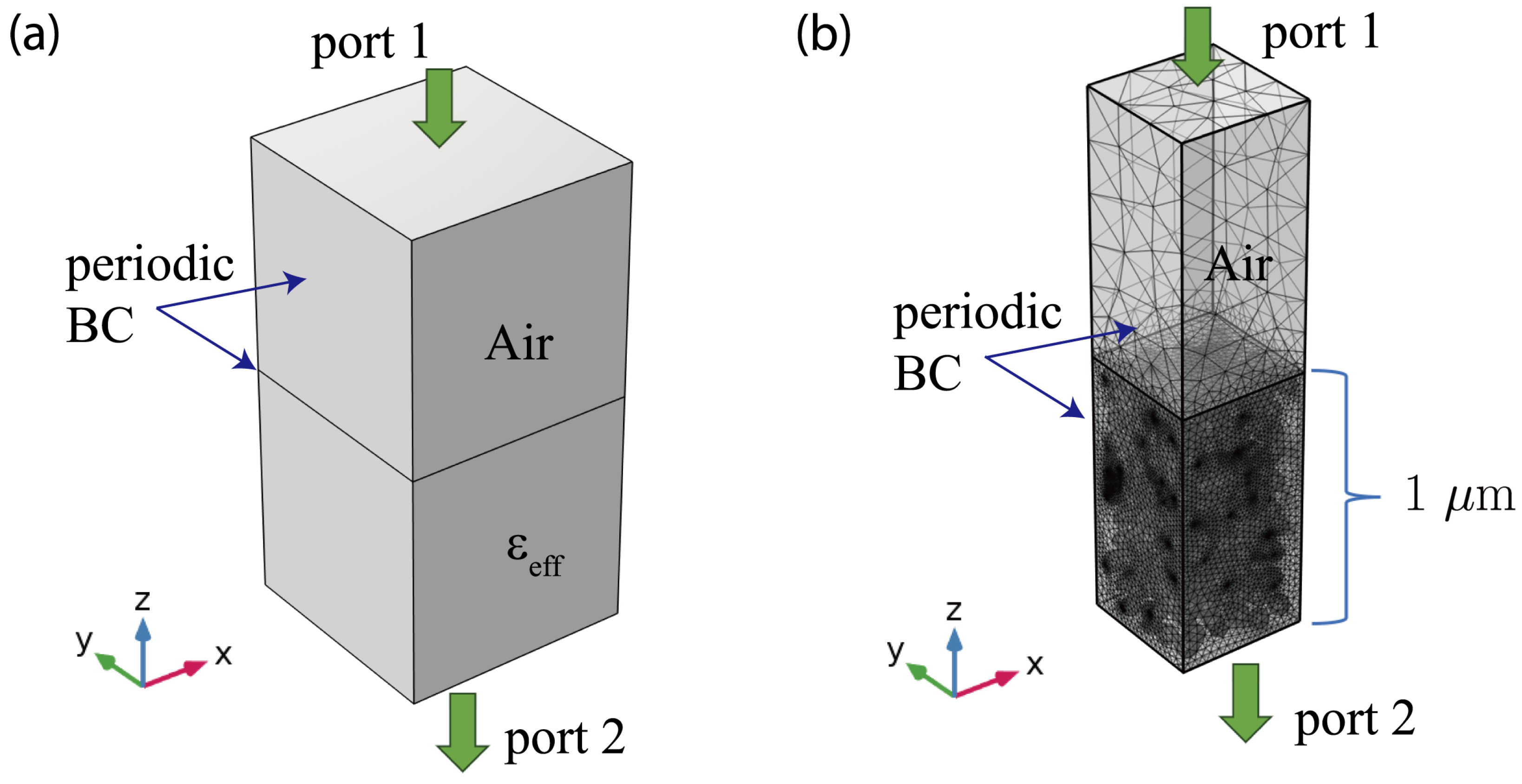

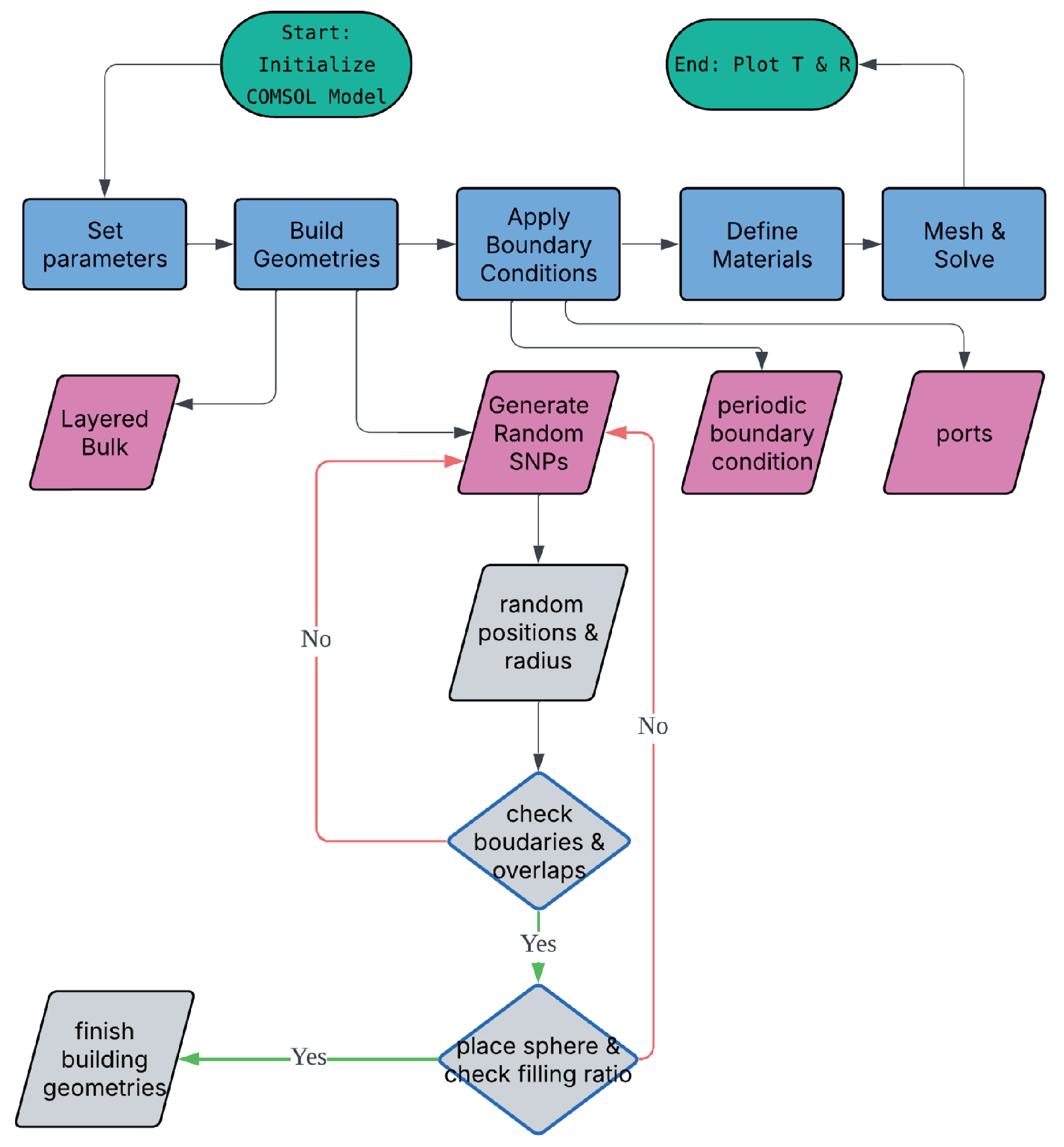

3. Validation of EMT Against Full-Wave Simulation

3.1. FEM Simulation Setup

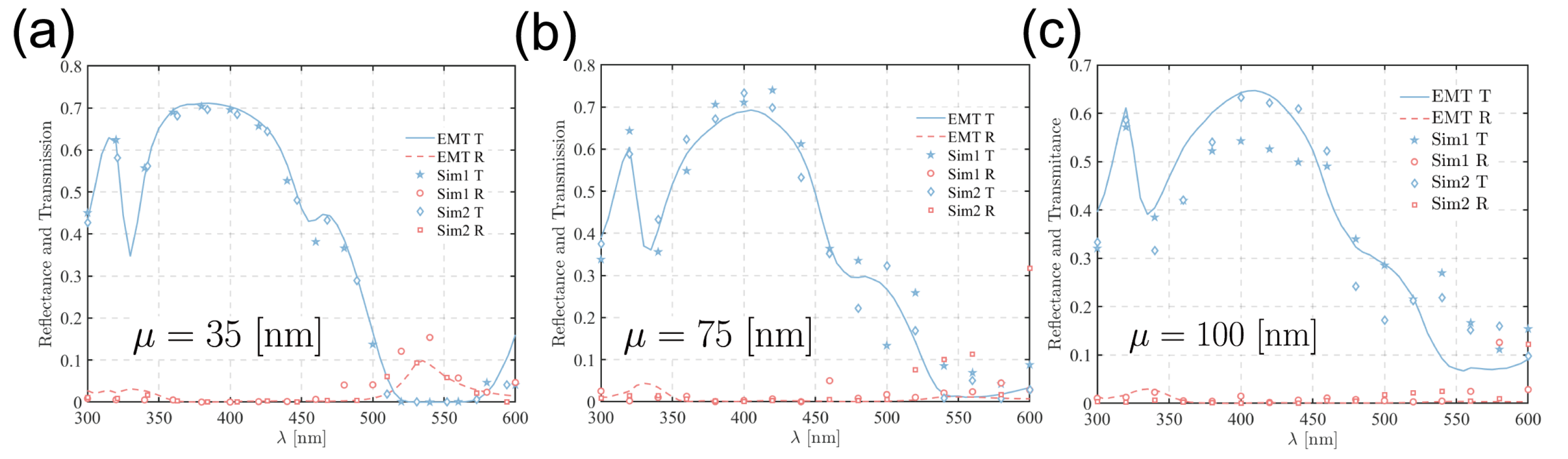

3.2. Comparison Between the EMT and FEM Methods

4. Summary and Future Research Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, J.; Polizos, G. Hollow Silica Particles: Recent Progress and Future Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slowing, I.I.; Vivero-Escoto, J.L.; Wu, C.W.; Lin, V.S.Y. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as controlled release drug delivery and gene transfection carriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemzadeh, P.; Sayadi, K.; Toolabi, A.; Sayadi, J.; Zeraati, M.; Chauhan, N.P.S.; Sargazi, G. Structure-Property Relationship for Different Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles and its Drug Delivery Applications: A Review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 823785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, B.; Wu, X.; Tian, Y.; Chen, P. Nanosilica/carbon composite spheres as anodes in Li-ion batteries with excellent cycle stability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 1476–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjua, T.I.; Cao, Y.; Kleitz, F.; Linden, M.; Yu, C.; Popat, A. Silica nanoparticles: A review of their safety and current strategies to overcome biological barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 203, 115115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Tao, J.; Shan, Z. Silicon nanoparticles encapsulated in multifunctional crosslinked nano-silica/carbon hybrid matrix as a high-performance anode for Li-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 418, 129468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, X.; He, J. Self-Cleaning Antireflective Coatings Assembled from Peculiar Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2010, 26, 13528–13534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Fleming, R.; Zou, M. Transparent self-cleaning and antifogging silica nanoparticle films. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 115, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Lei, J. Mechanically robust and self-cleaning antireflection coatings from nanoscale binding of hydrophobic silica nanoparticles. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 200, 109939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Cui, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Ding, R.; Xu, Y. A broadband antireflective coating based on a double-layer system containing mesoporous silica and nanoporous silica. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 7187–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Zou, X.; Du, K.; Zhang, L.; Yan, H.; Yuan, X. Ultralow-refractive-index optical thin films built from shape-tunable hollow silica nanomaterials. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 1802–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, J.; Mendelsohn, J.D.; Rubner, M.F. Reversibly erasable nanoporous anti-reflection coatings from polyelectrolyte multilayers. Nat. Mater. 2002, 1, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, H.A. Thin-Film Optical Filters, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Southwell, W.H. Gradient-index antireflection coatings. Opt. Lett. 1989, 8, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raut, H.K.; Ganesh, V.A.; Nair, A.S.; Ramakrishna, S. Anti-reflective coatings: A critical, in-depth review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3779–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, J.C.M., XII. Colours in metal glasses and in metallic films. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1904, 203, 385–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, D.A.G. Berechnung verschiedener physikalischer Konstanten von heterogenen Substanzen. I. Dielektrizitätskonstanten und Leitfähigkeiten der Mischkörper aus isotropen Substanzen. Ann. Phys. 1935, 416, 636–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvola, A. Electromagnetic Mixing Formulas and Applications; The Institution of Engineering and Technology: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bohren, C.F.; Huffman, D.R. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles; Wiley-VCH: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Félidj, N.; Aubard, J.; Lévi, G. Discrete dipole approximation for ultraviolet–visible extinction spectra simulation of silver and gold colloids. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malasi, A.; Kalyanaraman, R.; Garcia, H. From Mie to Fresnel through effective medium approximation with multipole contributions. J. Opt. 2014, 16, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, R.; Devilez, A.; Enoch, S.; Stout, B.; Bonod, N. Polarizability expressions for predicting resonances in plasmonic and Mie scatterers. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 063833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodan, E.; Radloff, C.; Halas, N.J.; Nordlander, P. A hybridization model for the plasmon response of complex nanostructures. Science 2003, 302, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.A. Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khlebtsov, N.G. T-matrix method in plasmonics: An overview. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2013, 123, 184–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A.; Boriskina, S.V.; Reinhard, B.M.; Negro, L.D. Deterministic aperiodic arrays of metal nanoparticles for surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). Opt. Express 2009, 17, 3741–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, T.C. Effective Medium Theory: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed.; International Series of Monographs on Physics; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mie, G. Beiträge zur Optik trüber Medien, speziell kolloidaler Metallösungen. Ann. Phys. 1908, 330, 377–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldy, L.L. The multiple scattering of waves. I. General theory of isotropic scattering by randomly distributed scatterers. Phys. Rev. 1945, 67, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, T.G.; Weiglhofer, W.S. Homogenization of biaxial composite materials: Dissipative anisotropic properties. J. Opt. A Pure Appl. Opt. 2000, 2, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Peng, M.; Estevez, D.; Brosseau, C. Electromagnetic composites: From effective medium theories to metamaterials. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, J.; Lee, S.C.; Kienle, A. Calculation of the near fields for the scattering of electromagnetic waves by multiple infinite cylinders at perpendicular incidence. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2012, 113, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, A.; Skowronski, L.; Trzcinski, M.; Szoplik, T. Controlling the optical parameters of self-assembled silver films with wetting layers and annealing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 421, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, F.; Xu, Y.; Li, X. On the Effective Medium Theory for Silica Nanoparticles with Size Dispersion. Surfaces 2026, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010011

Liu F, Xu Y, Li X. On the Effective Medium Theory for Silica Nanoparticles with Size Dispersion. Surfaces. 2026; 9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Feng, Yao Xu, and Xiaowei Li. 2026. "On the Effective Medium Theory for Silica Nanoparticles with Size Dispersion" Surfaces 9, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010011

APA StyleLiu, F., Xu, Y., & Li, X. (2026). On the Effective Medium Theory for Silica Nanoparticles with Size Dispersion. Surfaces, 9(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces9010011