Balancing Hydrophobicity and Water-Vapor Transmission in Sol–Silicate Coatings Modified with Colloidal SiO2 and Silane Additives

Abstract

1. Introduction

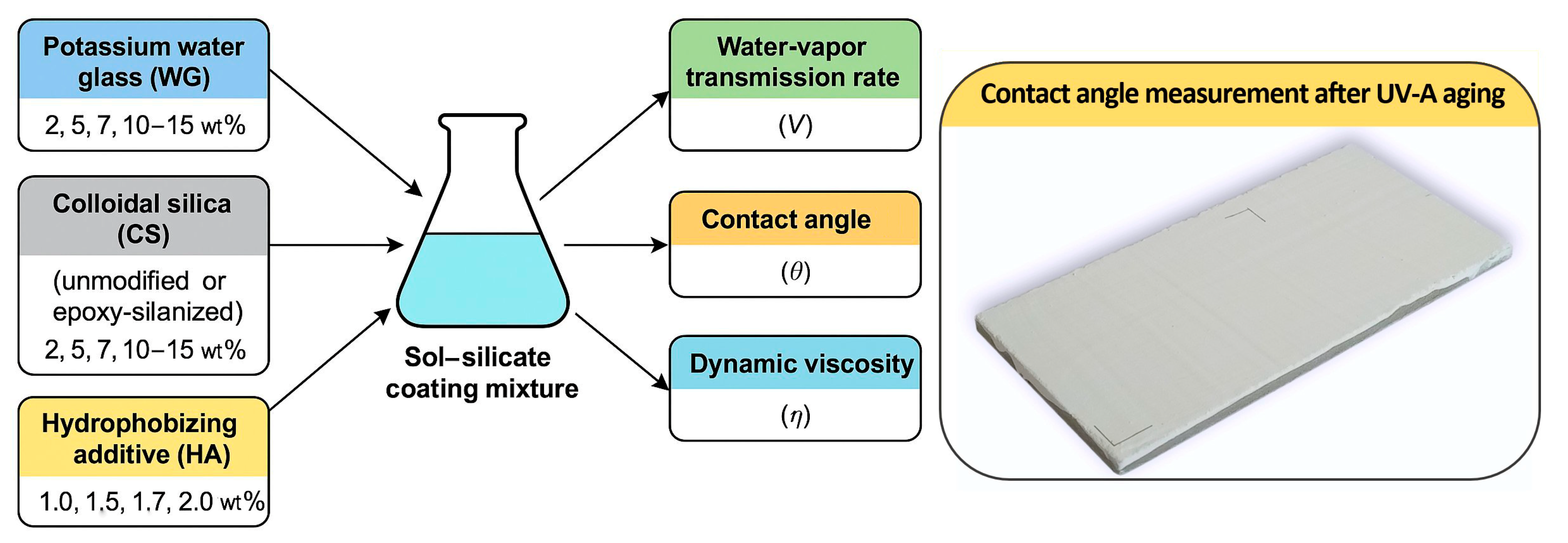

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Modified Coating Formulations

2.1.2. Verification Series

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Dynamic Viscosity

2.2.2. Water-Vapor Transmission Test and Coating Classification

2.2.3. Wettability and Contact Angle Measurement

2.2.4. Artificial Aging Tests

2.2.5. Microscopic Characterization

2.2.6. Data Processing and Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface and Cross-Sectional Morphology of the Coatings

3.2. Viscosity and Storage Stability of Coating Mixtures

3.3. Properties of Coatings with WG as the Predominant Binder

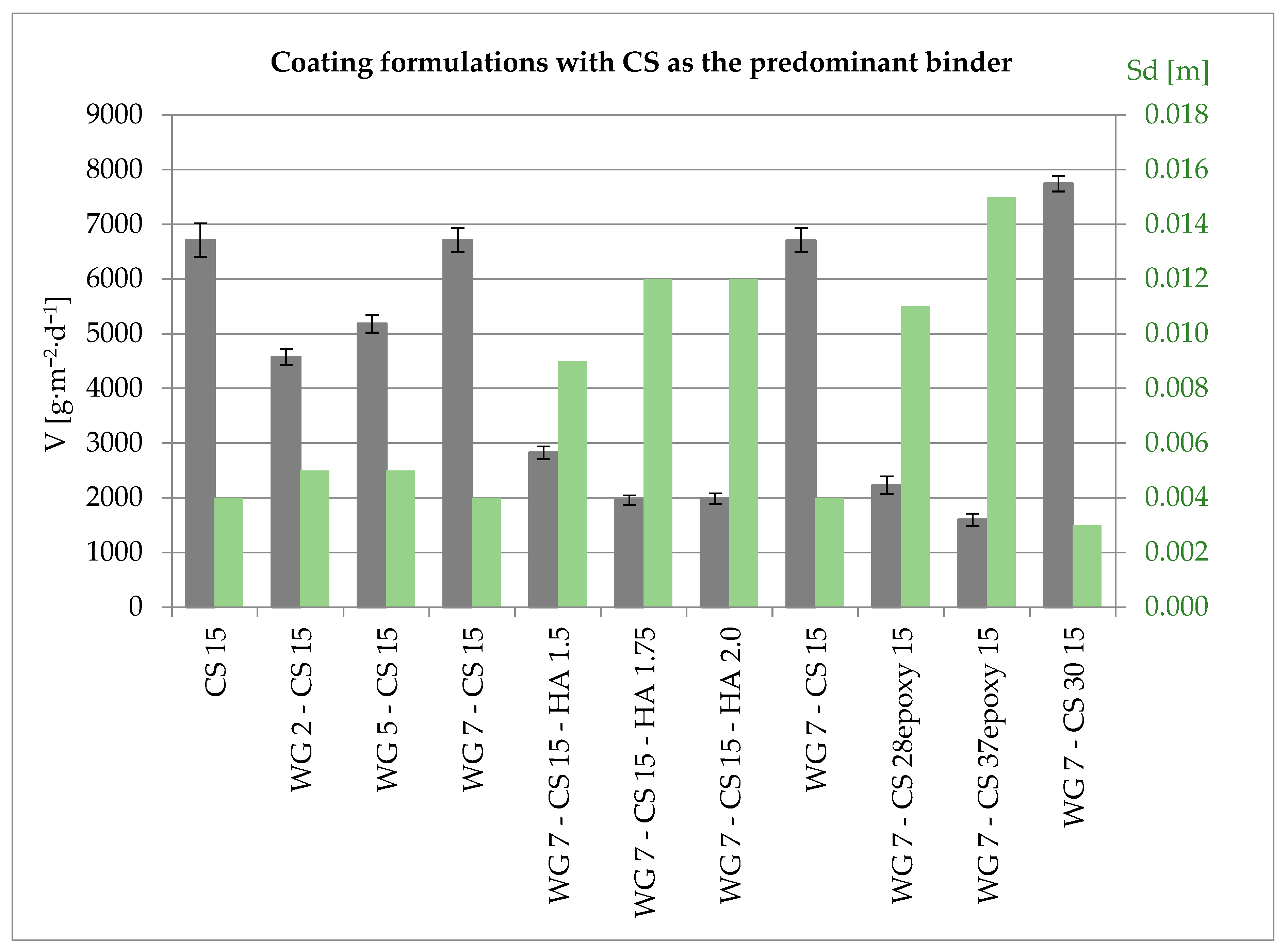

3.4. Properties of Coatings with CS as the Predominant Binder

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Figueira, R.B. Hybrid sol-gel coatings for corrosion mitigation: A critical review. Polymers 2020, 12, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, C.M.; Le, T.H. The Study’s Chemical Interaction of the Sodium Silicate Solution with Extender Pigments to Investigate High Heat Resistance Silicate Coating. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2021, 2021, 5510193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yona, A.M.C.; Žigon, J.; Kamlo, A.N.; Pavlic, M.; Dahle, S.; Petric, M. Silicate and Sol-Silicate Inorganic—Organic Hybrid Dispersion Coatings for Wood. Materials 2021, 14, 3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.S.A.; Viswanath, B.A.; Raghul, P. A Review of Preparation and Characterization of Sol-Gel coating forCorrosion Mitigation. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Sci. 2024, 8, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, K.; Ali, M.; Gingrich, K.; Porter, D.L.; Chong, S.; Riley, B.J.; Peak, C.W.; Naleway, S.E.; Zharov, I.; Carlson, K. Sol-gel derived silica: A review of polymer-tailored properties for energy and environmental applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 336, 111874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yan, H.; Yan, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, K.; Li, C.; Qian, Y. Improvement of the environmental stability of sol-gel silica anti-reflection coatings. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2022, 101, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, A.; Castro, Y.; Conde, A.; de Damborenea, J.J. Preface to the First Edition; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 9783319321011. [Google Scholar]

- Purcar, V.; Rădiţoiu, V.; Raduly, F.M.; Rădiţoiu, A.; Căprărescu, S.; Frone, A.N.; Şomoghi, R.; Anastasescu, M.; Stroescu, H.; Nicolae, C.A. Influence of Perfluorooctanoic Acid on Structural, Morphological, and Optical Properties of Hybrid Silica Coatings on Glass Substrates. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macera, L.; Pullini, D.; Boschetto, A.; Bottini, L.; Mingazzini, C.; Falleti, G.L. Sol–Gel Silica Coatings for Corrosion Protection of Aluminum Parts Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting (SLM) Technology. Coatings 2023, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, F.; Guo, J.; Feng, C.; Shen, J. UV resistance of sol-gel hydrophobic silica antireflective coatings. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2023, 106, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Olmo, R.; Tiringer, U.; Milošev, I.; Visser, P.; Arrabal, R.; Matykina, E.; Mol, J.M.C. Hybrid sol-gel coatings applied on anodized AA2024-T3 for active corrosion protection. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 419, 127251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ran, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Du, C.; Yang, F.; Bao, Q.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, W. A Novel Intumescent MCA-Modified Sodium Silicate/Acrylic Flame-Retardant Coating to Improve the Flame Retardancy of Wood. Molecules 2024, 29, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganina, V.I.; Kislitsyna, S.N.; Mazhitov, Y.B. Development of sol-silicate composition for decoration of building walls. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2018, 9, e00173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganina, V.I.; Frolov, M.V.; Mazhitov, E.B. Influence of protective and decorative coatings based on sol-silicate paints on the moisture regime of external walls of buildings. Constr. Geotech. 2021, 12, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Villar, E.M.; Rivas, T.; Pozo-Antonio, J.S. Sol-silicate versus organic paints: Durability after outdoor and ultraviolet radiation exposures. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 168, 106843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bös, M.; Gabler, L.; Leopold, W.M.; Steudel, M.; Weigel, M.; Kraushaar, K. Molecular Design and Nanoarchitectonics of Inorganic—Organic Hybrid Sol—Gel Systems for Antifouling Coatings. Gels 2024, 10, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, R.H.R.Q.; Falcão, J.R.; Bersch, J.D.; Baptista, D.T.; Masuero, A.B. Performance and Durability of Paints for the Conservation of Historic Façades. Buildings 2024, 14, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, W.; Cui, Z.; Li, W. The Effects of Various Silicate Coatings on the Durability of Concrete: Mechanisms and Implications. Buildings 2024, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P.; Gevert, B. Aqueous silane modified silica sols: Theory and preparation. Pigment Resin Technol. 2011, 40, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganina, V.I.; Mazhitov, Y.B. Estimation of porosity of coatings based on sol of silicate paint. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 962, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Contaldi, V.; Licciulli, A.; Marzo, F. Self-cleaning mineral paint for application in architectural heritage. Coatings 2016, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Kiran, U. V Degradation of Paints and Its Microbial Effect on Health and Environment. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 4879–4884. [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar, H.R.; Rao, S.S.; Karigar, C.S. Biodegradation of paints: A current status. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 5, 1977–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, T. Stabilisation of acrylic latexes containing silica nanoparticles for dirt repellent coating applications. Polymer 2023, 271, 125830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.C.; Diebold, M.; Kraiter, D.; Velez, C.; Jernakoff, P. Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Dirt Pickup Resistance. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2020, 17, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, D.J.; Deschaume, O.; Perry, C.C. An overview of the fundamentals of the chemistry of silica with relevance to biosilicification and technological advances. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danks, A.E.; Hall, S.R.; Schnepp, Z. The evolution of “sol-gel” chemistry as a technique for materials synthesis. Mater. Horiz. 2016, 3, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoš, P.; Burian, A. Vodní Sklo; Silchem: Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic, 2002; ISBN 802389515X. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, P. Modified Colloidal Silica for Enhancement of Dirt Pick-Up Modified Colloidal Silica for Enhancement of Dirt Pick-Up Resistance and Open Time in Decorative Paints. In Proceedings of the SLF Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, 27–28 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Iler, R.K. The Chemistry of Silica: Solubility, Polymerization, Colloid and Surface Properties, and Biochemistry; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-471-02404-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zárate-Reyes, J.M.; Flores-Romero, E.; Cheang-Wong, J.C. Systematic preparation of high-quality colloidal silica particles by sol–gel synthesis using reagents at low temperature. Int. J. Appl. Glas. Sci. 2022, 13, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.P.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Mishra, G.; Sharma, U.; Singh, G.; Ahalawat, S. Sol-Gel processing of silica nanoparticles and their applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 214, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, G.S.; Vienna, J.D.; Lian, J.; Scully, J.R.; Gin, S.; Ryan, J.V.; Wang, J.; Kim, S.H.; Windl, W.; Du, J. A comparative review of the aqueous corrosion of glasses, crystalline ceramics, and metals. npj Mater. Degrad. 2018, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganina, V.I.; Kislitsyna, S.N.; Mazhitov, E.B. Long-Term Strength of Coatings Based on Sol-Silicate Paint. Vestn. MGSU 2018, 13, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsharimani, N.; Durán, A.; Galusek, D.; Castro, Y. Hybrid sol–gel silica coatings containing graphene nanosheets for improving the corrosion protection of AA2024-T3. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azani, M.R.; Hassanpour, A. Nanotechnology in the Fabrication of Advanced Paints and Coatings: Dispersion and Stabilization Mechanisms for Enhanced Performance. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202400844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.; Avó, J.; Berberan-Santos, M.N.M.S.; Crucho, C.I.C. PH-Responsive Silica Coatings: A Generic Approach for Smart Protection of Colloidal Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 9460–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman-Burstein, D.; Dotan, A.; Dodiuk, H.; Kenig, S. Hybrid sol-gel superhydrophobic coatings based on alkyl silane-modified nanosilica. Polymers 2021, 13, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedeva, E.Y.; Kazmina, O.V. Nature and quantity of silicate filler influence on silicate paint properties with lowered content of volatile compounds. ChemChemTech 2018, 61, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essen, B.; Oggermueller, H. Neuburg Siliceous Earth in Silicate Emulsion Paints; Hoffmann Mineral: Neuburg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, D.G. Failure Analysis of Paints and Coatings: Revised Edition; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.; Lo, G.J.; Hamilton, A. Water vapour permeability of inorganic construction materials. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2024, 57, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 7783:2019; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Water-Vapour Transmission Properties—Cup Method. CEN: Brussels, Belgium; ISO: Geneva, Swizterland, 2019.

- ISO 3233-1:2019; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Non-Volatile-Matter Content—Part 1: General Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Swizterland, 2019.

- EN 1062-1:2005; Paints and Varnishes—Coating Materials and Coating Systems for Exterior Masonry and Concrete—Part 1: Classification. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Young, T., III. An essay on the cohesion of fluids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1805, 95, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q-Lab Corporation. Q-UV Accelerated Weathering Tester—Operating Procedure for UVA-340 Lamps; Q-Lab Corporation: Westlake, OH, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Q-Lab Corporation. Q-UV Accelerated Weathering Tester—Spray Function Procedure; Q-Lab Corporation: Westlake, OH, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Q-Lab Corporation. Q-UV Accelerated Weathering Tester—Calibration and Verification Guidelines; Q-Lab Corporation: Westlake, OH, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, J.; Pan, C.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Chen, D. Research on Salt Corrosion Resistance of Lithium-Based Protective Coating on Mortar Substrate. Materials 2023, 16, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2808:2019; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Film Thickness. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Swizterland, 2019.

- Burg, A.; Yadav, K.K.; Meyerstein, D.; Kornweitz, H.; Shamir, D.; Albo, Y. Effect of Sol–Gel Silica Matrices on the Chemical Properties of Adsorbed/Entrapped Compounds. Gels 2024, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seljelid, K.K.; Neto, O.T.; Akanno, A.N.; Ceccato, B.T.; Ravindranathan, R.P.; Azmi, N.; Cavalcanti, L.P.; Fjelde, I.; Knudsen, K.D.; Fossum, J.O. Growth kinetics and structure of a colloidal silica-based network: In situ RheoSAXS investigations. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2024, 233, 2757–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, C.J.; Scherer, G.W. Sol–Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol–Gel Processing; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-12-134970-7. [Google Scholar]

- Du, T.; Li, H.; Sant, G.; Bauchy, M. New insights into the sol-gel condensation of silica by reactive molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 234504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuravlev, L.T. The Surface Chemistry of Amorphous Silica. Zhuravlev Model. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2000, 173, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhizhchenko, A.Y.; Shabalina, A.V.; Aljulaih, A.A.; Gurbatov, S.O.; Kuchmizhak, A.A.; Iwamori, S.; Kulinich, S.A. Stability of Octadecyltrimethoxysilane-Based Coatings on Aluminum Alloy Surface. Materials 2022, 15, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Y.L.; Soutar, A.M.; Zeng, X.T. Increasing hydrophobicity of sol-gel hard coatings by chemical and morphological modifications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005, 198, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamarpoor, R.; Jamshidi, M.; Joshaghani, M. Hydrophobic silanes-modified nano-SiO2; reinforced polyurethane nanocoatings with superior scratch resistance, gloss retention, and metal adhesion. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | CAS No. * | Surface Modification | SiO2 Content [wt %] | Particle Size [nm] | Neutralization Agent | pH | Density 20 °C [g·cm−3] | Viscosity 25 °C [mPa·s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 7631-86-9 | - | 29.1 | 15 | 0.28 wt % Na2O | 8.5–10 | 1.2 | 5 |

| CS 28epoxy | 1239225-81-0 | Epoxysilane | 28.0 | 7 | 2.5 wt % ethanol | 8 | 1.2 | 5 |

| CS 37epoxy | 1239225-81-0 | Epoxysilane | 37.0 | 12 | 2.5 wt % ethanol | 8 | 1.26 | 8 |

| CS 30 | 7631-86-9 | - | 30.0 | 5 | 0.15 wt % ammonia | 9.5 | 1.2 | 5 |

| η [mPa·s] - WG as the Main Binder | Storage Period | η [mPa·s] - CS as the Main Binder | Storage Period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 d | 1 mo | 6 mo | 2 yr | 1 d | 1 mo | 6 mo | 2 yr | ||

| WG 15 | 1460 | 8600 | NA * | CS 15 | 1260 | 1233 | 1300 | NA | |

| WG 15-CS 2 | 2100 | 9630 | 26,933 | 28,100 | WG 2-CS 15 | 1030 | 10,200 | NA | |

| WG 15-CS 5 | 1280 | NM | WG 5-CS 15 | 1130 | 12,500 | NA | |||

| WG 15-CS 7 | 1933 | NM | WG 7-CS 15 | 1610 | 10,766 | 28,000 | 30,800 | ||

| WG 15-CS 10 | 1680 | NM | WG 10-CS 15 | 1400 | NA | ||||

| WG 10 | 3233 | 6500 | 19,150 | 20,320 | WG 7-CS 15-HA 1.5 | 5633 | 8666 | 21,700 | 27,900 |

| WG 10-CS 2 | 2900 | 5931 | 13,900 | 18,700 | WG 7-CS 15-HA 1.75 | 3033 | 7060 | 21,300 | 26,500 |

| WG 10-CS 5 | 2533 | 10,933 | 15,100 | 20,900 | WG 7-CS 15-HA 2.0 | 4266 | 8960 | 11,030 | 17,700 |

| WG 10-CS 7 | 2300 | 9066 | NA | WG 7-CS 15 | 1900 | 9780 | 19,833 | 19,800 | |

| WG 10-CS 10 | 1968 | 12,466 | NA | WG 7-CS 28epoxy 15 | 1910 | 1920 | 1920 | NA | |

| WG 10-CS 5-HA 1.5 | 6300 | 8060 | NA | WG 7-CS 37epoxy 15 | 1530 | 2270 | 4200 | NA | |

| WG 10-CS 5-HA 1.75 | 6200 | 7833 | 30,380 | 32,000 | WG 7-CS 30 15 | 1800 | 18,600 | 23,833 | 24,500 |

| WG 10-CS 5-HA 2.0 | 4910 | 7760 | 29,650 | 31,600 | |||||

| WG 15 | WG 15-CS 2 | WG 15-CS 5 | WG 15-CS 7 | WG 15-CS 10 | WG 10 | WG 10-CS 2 | WG 10-CS 5 | WG 10-CS 7 | WG 10-CS 10 | WG 10-CS 5-HA 1.5 | WG 10-CS 5-HA 1.75 | WG 10-CS 5-HA 2.0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application rate [kg·m−2] | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.4 |

| Dry coating mass [g] | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 0.92 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| V [g·m−2·d−1] | 4424 | 4319 | 1156 | 1731 | 4218 | 10,655 | 4771 | 3774 | 11,945 | 14,416 | 1478 | 1574 | 1972 |

| Sd [m] | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.013 |

| Calculated DFT [mm] | 0.137 | 0.133 | 0.201 | 0.208 | 0.155 | 0.122 | 0.202 | 0.183 | 0.189 | 0.210 | 0.172 | 0.205 | 0.210 |

| CS 15 | WG 2-CS 15 | WG 5-CS 15 | WG 7-CS 15 | WG 7-CS 15-HA 1.5 | WG 7-CS 15-HA 1.75 | WG 7-CS 15-HA 2.0 | WG 7-CS 15 | WG 7-CS 28epoxy 15 | WG 7-CS 37epoxy 15 | WG 7-CS 30 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application rate (wet) [kg·m−2] | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| Dry coating mass [g] | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.15 | 0.88 |

| V [g·m−2·d−1] | 6712 | 4574 | 5182 | 6712 | 2822 | 1957 | 1987 | 6712 | 2231 | 1597 | 7742 |

| Sd [m] | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.003 |

| Calculated dry film thickness [mm] | 0.089 | 0.127 | 0.175 | 0.175 | 0.170 | 0.175 | 0.185 | 0.175 | 0.191 | 0.208 | 0.205 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Němcová, D.; Kobetičová, K.; Tichá, P.; Burianová, I.; Koňáková, D.; Kejzlar, P.; Böhm, M. Balancing Hydrophobicity and Water-Vapor Transmission in Sol–Silicate Coatings Modified with Colloidal SiO2 and Silane Additives. Surfaces 2025, 8, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040088

Němcová D, Kobetičová K, Tichá P, Burianová I, Koňáková D, Kejzlar P, Böhm M. Balancing Hydrophobicity and Water-Vapor Transmission in Sol–Silicate Coatings Modified with Colloidal SiO2 and Silane Additives. Surfaces. 2025; 8(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040088

Chicago/Turabian StyleNěmcová, Dana, Klára Kobetičová, Petra Tichá, Ivana Burianová, Dana Koňáková, Pavel Kejzlar, and Martin Böhm. 2025. "Balancing Hydrophobicity and Water-Vapor Transmission in Sol–Silicate Coatings Modified with Colloidal SiO2 and Silane Additives" Surfaces 8, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040088

APA StyleNěmcová, D., Kobetičová, K., Tichá, P., Burianová, I., Koňáková, D., Kejzlar, P., & Böhm, M. (2025). Balancing Hydrophobicity and Water-Vapor Transmission in Sol–Silicate Coatings Modified with Colloidal SiO2 and Silane Additives. Surfaces, 8(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040088