Degradation of Traditional Silicate Glass and Protective Coatings Under Simulated Unsheltered Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Glass

2.2. Protective Coatings

2.3. Artificial Aging Protocol

2.3.1. Rainwater Runoff

2.3.2. Climatic Chamber

2.4. Characterization

2.4.1. Surface

2.4.2. Runoff Solution

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pre-Aging Phase: Glass Weathering

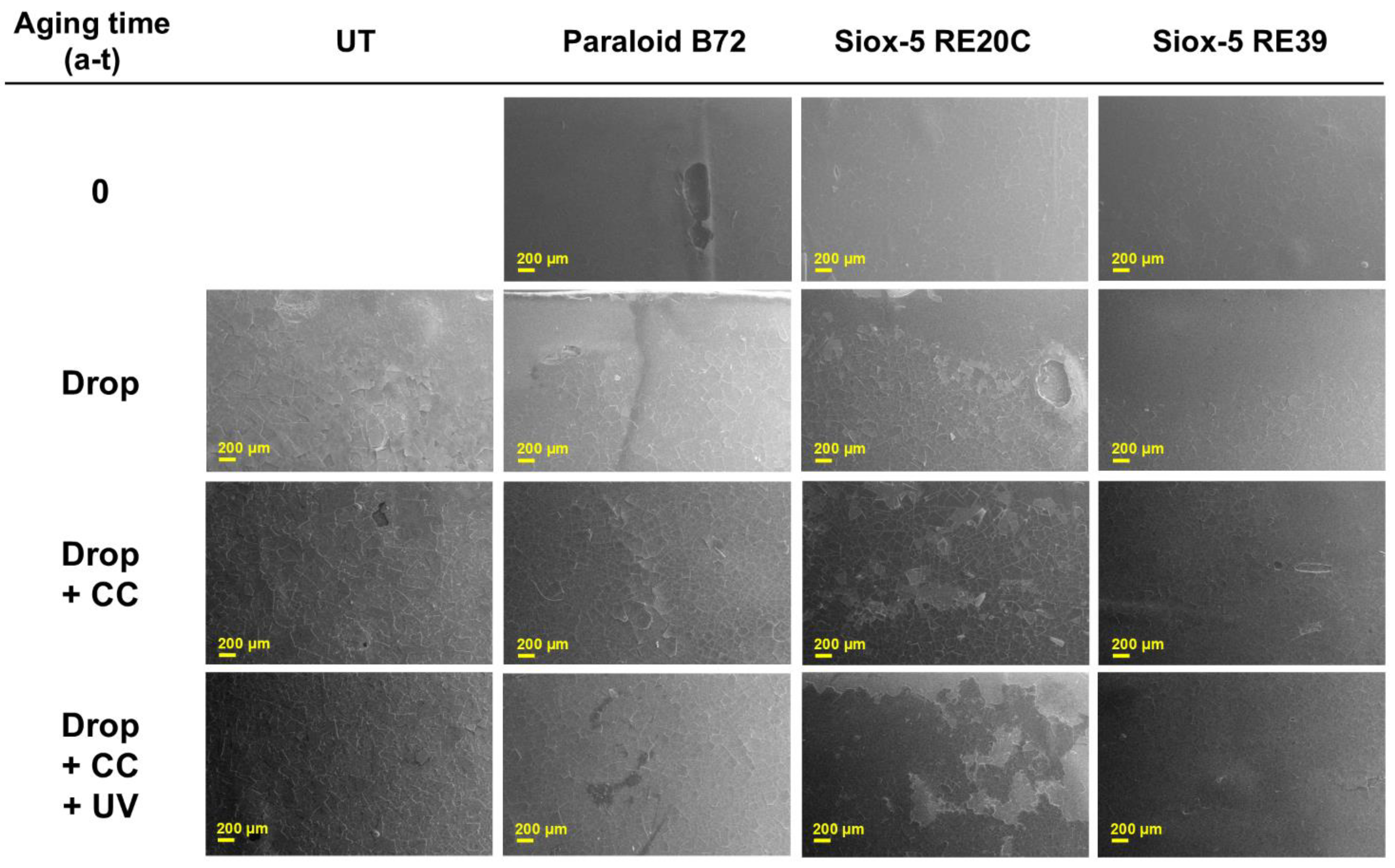

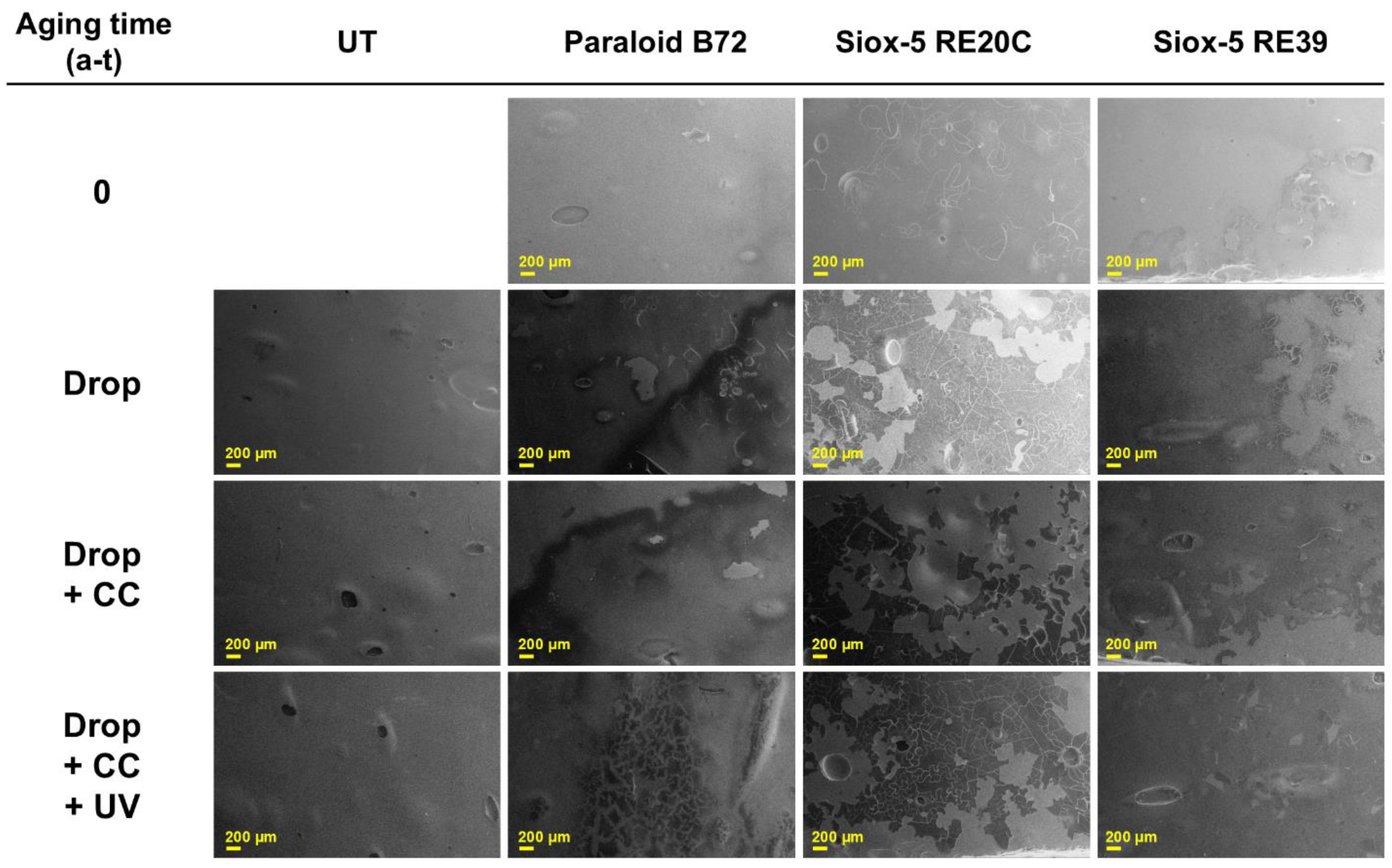

3.1.1. Surface Characterization

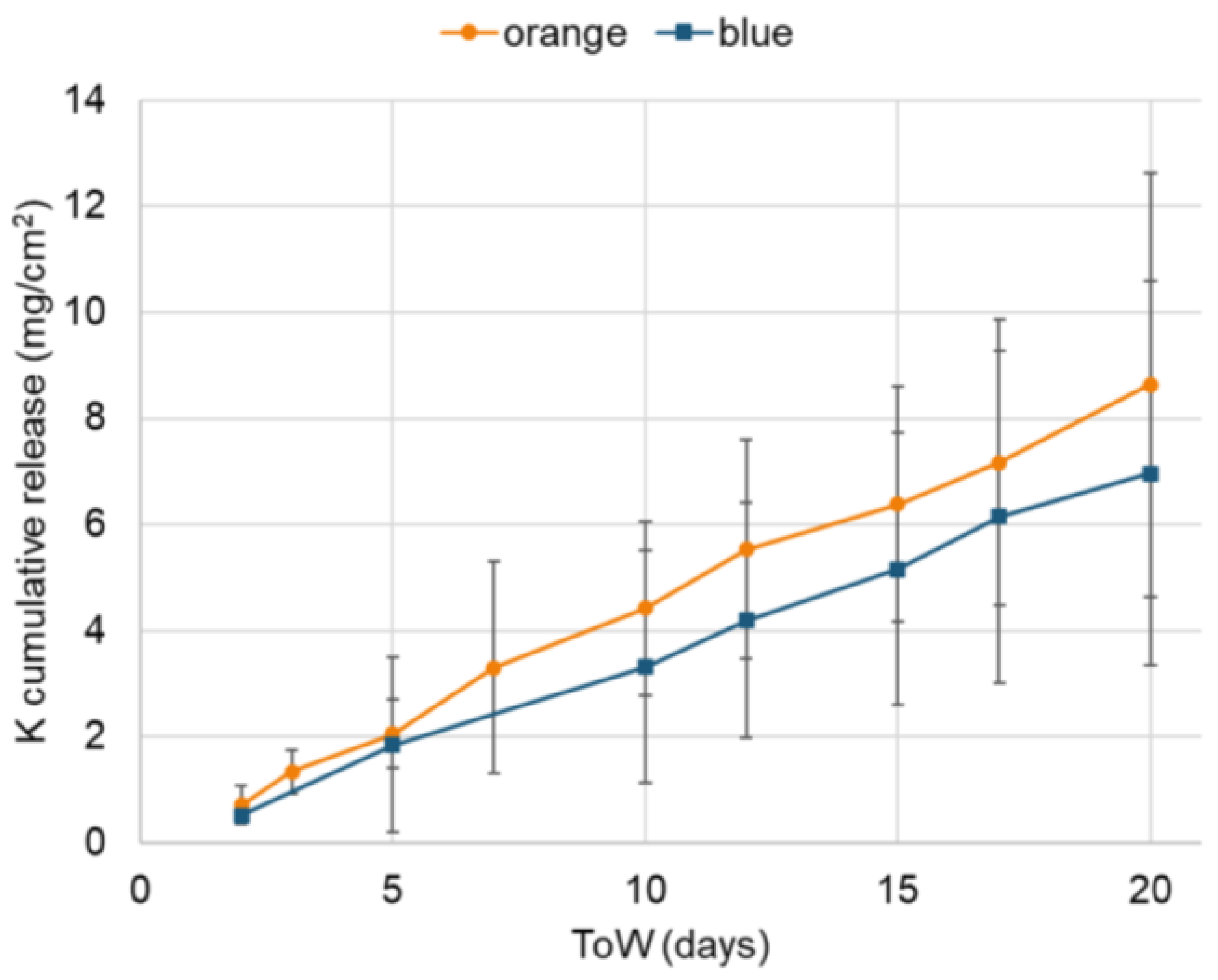

3.1.2. Runoff Solution

3.2. Aging Phase: Coating Evaluation

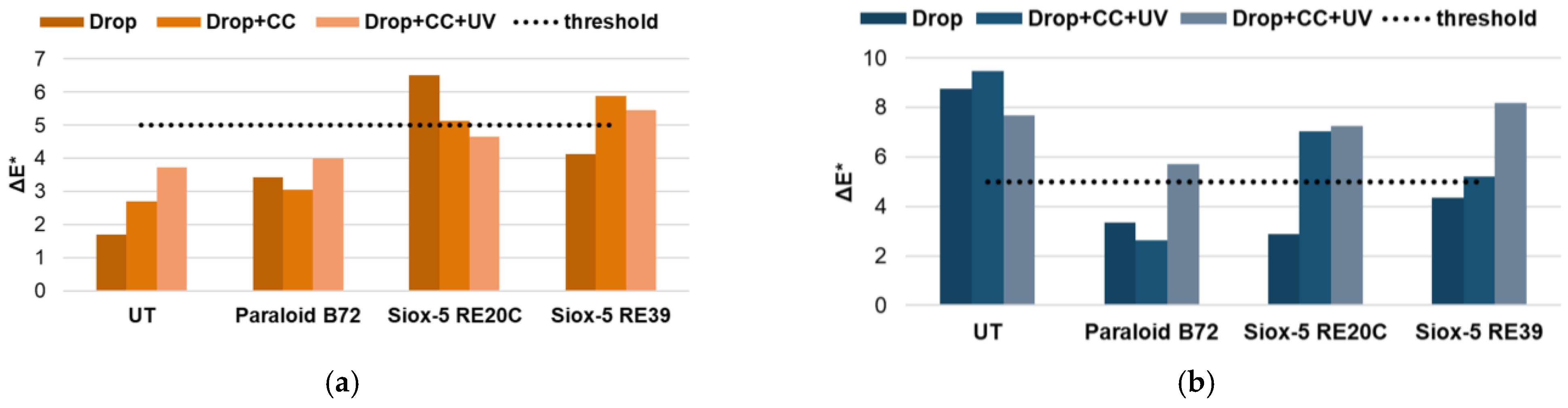

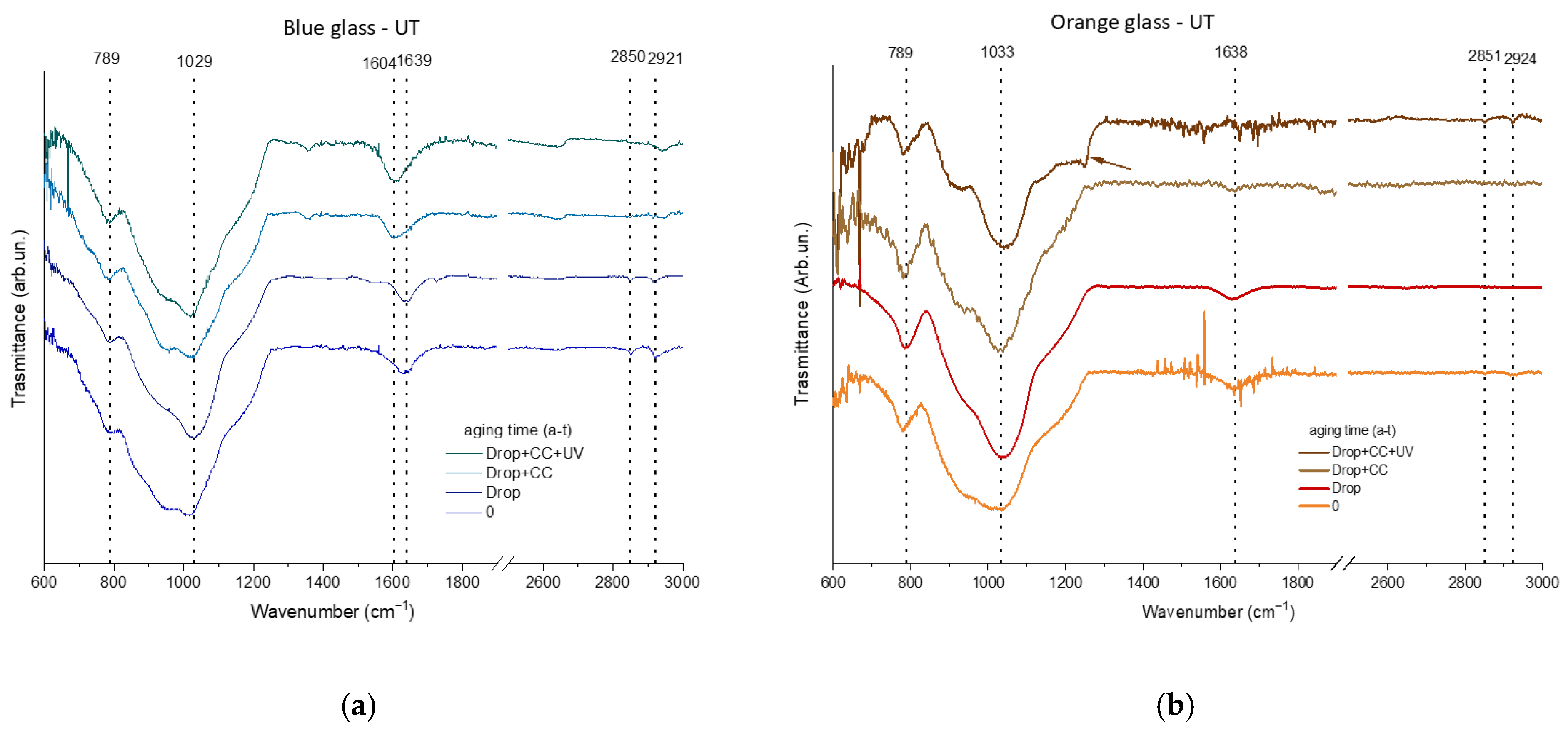

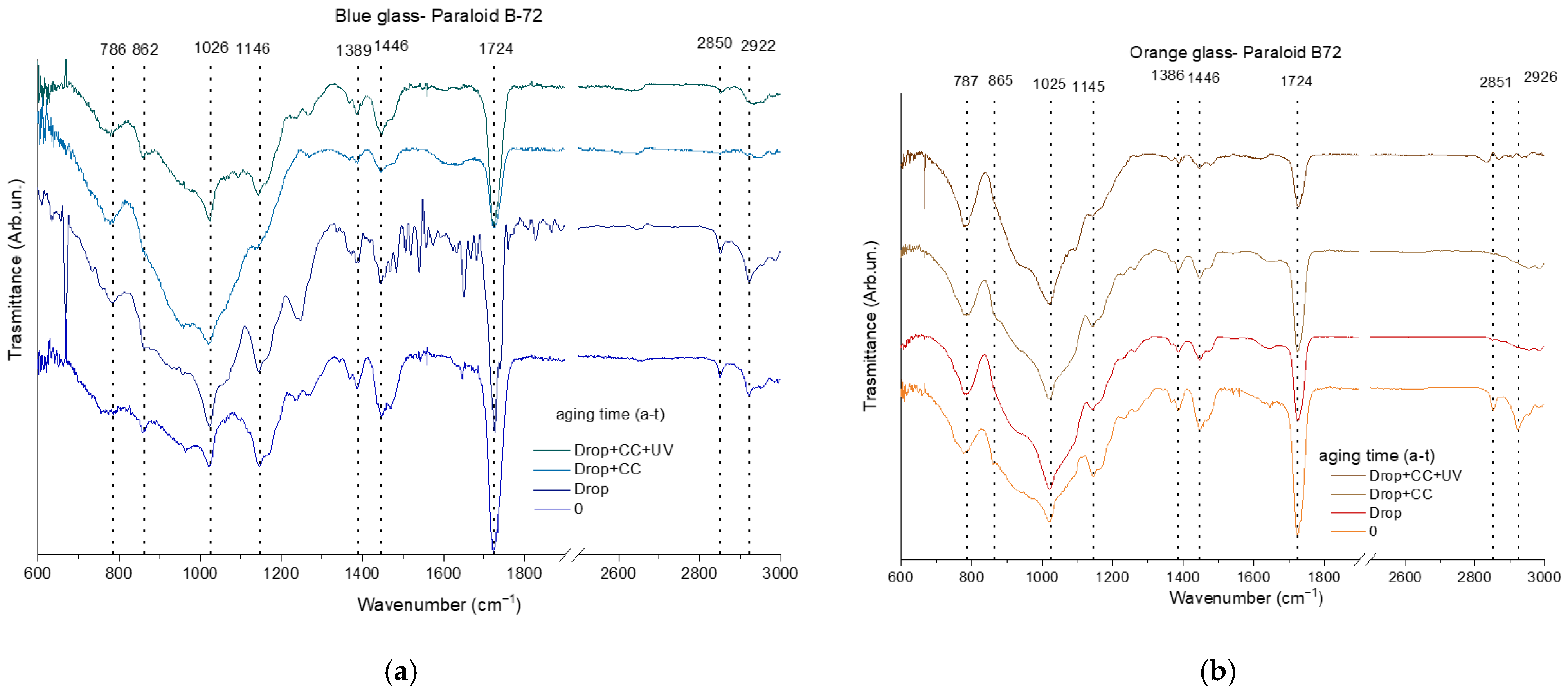

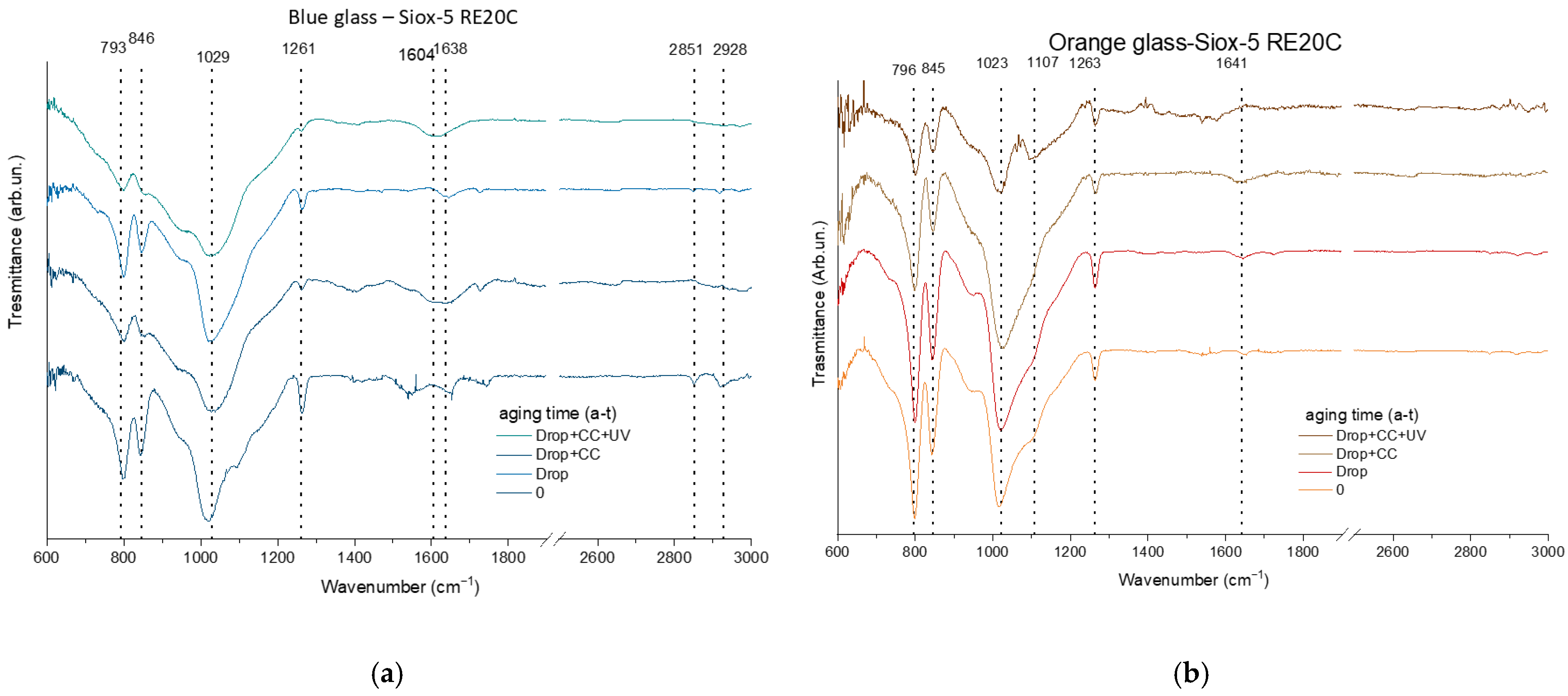

3.2.1. Surface Characterization

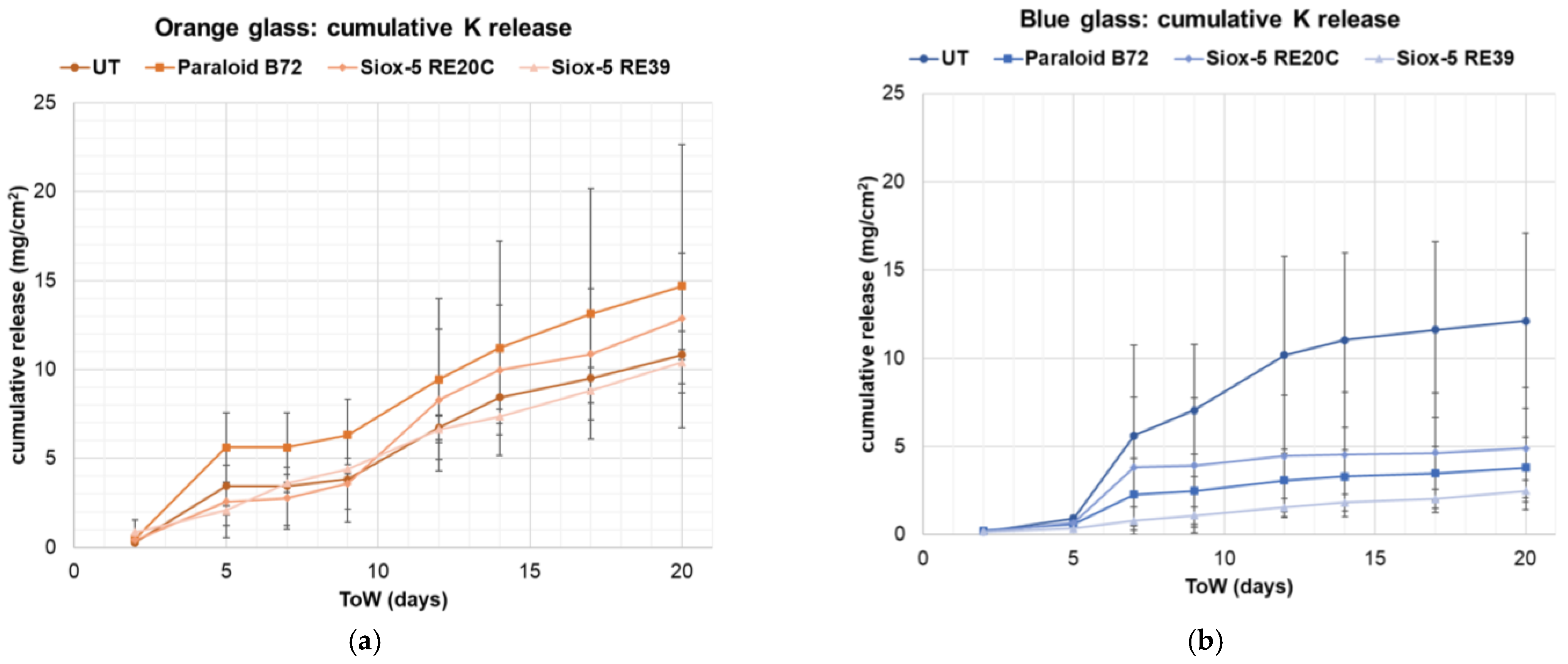

3.2.2. Runoff Solutions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UT | Untreated, uncoated glass |

| drop | Dripping test simulating rain runoff |

| CC | Climatic chamber |

| BO | Bridging oxygen |

| NBO | Non bridging oxygen |

References

- Scholze, H. Glass: Nature, Structure, and Properties; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-1-4613-9069-5. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, S.; Newton, R.G. Conservation and Restoration of Glass, 2nd ed.; Routledge, Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-08-056931-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zanini, R.; Fransceschin, G.; Cattaruzza, E.; Travigilia, A. A Review of Glass Corrosion: The Unique Contribution of Studying Ancient Glass to Validate Glass Alteration Models. npj Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández–Navarro, J.; Villegas, M. What Is Glass?: An Introduction to the Physics and Chemistry of Silicate Glasses. In Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass; Janssens, K., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-470-51614-0. [Google Scholar]

- Verità, M. Il Vetro: Proprietà, Resistenza Chimica e Processi Di Alterazione. In Mosaici Medievali a Roma Attraverso il Restauro Dell’ICR 1991–2004; Gangemi: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 507–516. [Google Scholar]

- Tite, M.S.; Freestone, I.; Mason, R.; Molera, J.; Vendrell-Saz, M.; Wood, N. Lead Glazes in Antiquity—Methods of Pro-duction and Reasons for Use. Archaeometry 1998, 40, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caurant, D.; Wallez, G.; Majérus, O.; Roisine, G.; Charpentier, T. Structure and Properties of Lead Silicate Glasses. In Lead in Glassy Materials in Cultural Heritage; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 35–92. ISBN 978-1-394-26541-1. [Google Scholar]

- Melcher, M.; Schreiner, M. Glass Degradation by Liquids and Atmospheric Agents. In Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass; Janssens, K., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 609–651. ISBN 978-0-470-51614-0. [Google Scholar]

- Melcher, M.; Schreiner, M. Leaching Studies on Naturally Weathered Potash-Lime–Silica Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2006, 352, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloteau, F.; Lehuédé, P.; Majérus, O.; Biron, I.; Dervanian, A.; Charpentier, T.; Caurant, D. New Insight into Atmospheric Alteration of Alkali-Lime Silicate Glasses. Corros. Sci. 2017, 122, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloteau, F.; Majérus, O.; Biron, I.; Lehuédé, P.; Caurant, D.; Charpentier, T.; Seyeux, A. Temperature-Dependent Mechanisms of the Atmospheric Alteration of a Mixed-Alkali Lime Silicate Glass. Corros. Sci. 2019, 159, 108129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, N.; García-Heras, M.; Gil, C.; Villegas, M.A. Chemical Degradation of Glasses under Simulated Marine Medium. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005, 94, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asay, D.B.; Seong, K.M. Evolution of the Adsorbed Water Layer Structure on Silicon Oxide at Room Temperature. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 16760–16763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalm, O.; Nuyts, G.; Janssens, K. Some Critical Observations about the Degradation of Glass: The Formation of Lamellae Explained. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 569, 120984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinton, C.W.; LaCourse, W.C. Experimental Survey of the Chemical Durability of Commercial Soda-Lime-Silicate Glasses. Mater. Res. Bull. 2001, 36, 2471–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shamy, T.M.; Morsi, S.E.; Taki-Eldin, H.D.; Ahemd, A.A. Chemical Durability of Na2O CaO SiO2 Glasses in Acid Solutions. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1975, 19, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, B.C. Molecular Mechanisms for Corrosion of Silica and Silicate Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1994, 179, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantzen, C.M.; Plodinec, M.J. Thermodynamic Model of Natural, Medieval and Nuclear Waste Glass Durability. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1984, 67, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centenaro, S.; Fransceschin, G.; Cattaruzza, E.; Travigilia, A. Consolidation and Coating Treatments for Glass in the Cultural Heritage Field: A Review. J. Cult. Heirtage 2023, 64, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncrieff, A. Problems and Potentialities in the Conservation of Vitreous Materials. Stud. Conserv. 1975, 20, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntasi, G.; Sbriglia, S.; Pitocchi, R.; Vinciguerra, R.; Melchiorre, C.; Dello Ioio, L.; Fatigati, G.; Crisci, E.; Bonaduce, I.; Carpentieri, A.; et al. Proteomic Characterization of Collagen-Based Animal Glues for Restoration. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 2173–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, S. A Review of Adhesives and Consolidants Used on Glass Antiquities. Stud. Conserv. 1984, 29, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Niu, Q.; Li, Z.; Xue, C. Investigation of Whitening Mechanism on Cultural Relic Surfaces Treated with Paraloid B72. Coatings 2024, 14, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artesani, A.; Di Turo, F.; Zucchelli, M.; Traviglia, A. Recent Advances in Protective Coatings for Cultural Heritage—An Overview. Coatings 2020, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, N.; Wittstadt, K.; Römich, H. Consolidation of Paint on Stained Glass Windows: Comparative Study and New Approaches. J. Cult. Heirtage 2009, 10, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bardi, M.; Hutter, H.; Schreiner, M.; Bertoncello, R. Potash-Lime-Silica Glass: Protection from Weathering. Herit. Sci. 2015, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bianco, B.; Bertoncello, R.; Bouquillon, A.; Dran, J.-C.; Milanese, L.; Roehrs, S.; Sada, C.; Salomon, J.; Voltolina, S. Investigation on Sol–Gel Silica Coatings for the Protection of Ancient Glass: Interaction with Glass Surface and Protection Efficiency. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2008, 354, 2983–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchin, M.; Bortolussi, C. La tecnologia sol-gel per la protezione della ceramica. In Il Restauro della Ceramica: Studio dei Materiali e delle Forme di Degrado, Progettazione di Iinterventi di Restauro e Conservazione: Giornata di Studio, MIC Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza, 29 Novembre 2019; Faenza Bollettino del Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza; Edizioni Polistampa: Firenze, Italy, 2019; pp. 74–82. ISBN 978-88-596-2059-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stoveland, L.P.; Ormsby, B.; Stols-Witlox, M.; Streeton, N.L.W. Mock-Ups and Materiality in Conservation Research. In Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation; ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Beijing, China, 17–21 May 2021; International Council of Museums: Paris, France, 2023; ISBN 978-2-491997-14-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dillis, S.; Van Ham-Meert, A.; Leeming, P.; Shortland, A.J.; Gobejishvili, G.; Abramishvili, M.; Degryse, P. Antimony as a Raw Material in Ancient Metal and Glass Making: Provenancing Georgian LBA Metallic Sb by Isotope Analysis. STAR Sci. Technol. Archaeol. Res. 2019, 5, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.; Stapleton, C.P. Composition Technology and Production of Coulerd Glasse from Roman Mosaic Vesseld. In Glass of the Roman World; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shortland, A.J. The Use and the Origin of Antimonate Colorants in Early Egyptian Glass. Archeometry 2002, 44, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Arruda, A.M.; Dias, L.; Barbosa, R.; Mirão, J.; Vandenabeele, P. The Combined Use of Raman and micro-X-ray Diffraction Analysis in the Study of Archaeological Glass Beads. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2019, 50, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsuk, O.; Fiocco, G.; Malagodi, M.; Re, A.; Lo Giudice, A.; Iaia, C.; Gulmini, M. The Non-Invasive Characterization of Iron Age Glass Finds from the “Gaetano Chierici” Collection in Reggio Emilia (Italy). Heritage 2023, 6, 5583–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, B.; Cristea-Stan, D.; Szokefalvi-Nagy, Z.; Kovács, I.; Harsányi, I. PIXE and PGAA–Complementary Methods for Studies on Ancient Glass Artefacts (from Byzantine, Late Medieval to Modern Murano Glass). Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2018, 417, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolussi, C.; Cecchin, M.; Checcucci, B.; Poggi, S. Conservazione preventiva ed innovazione: La tecnica sol-gel per le opere di Sosabravo e Carlè ad Albisola Superiore. In La Conservazione della Ceramica All’aperto: II Giornata di Studio, 10 giugno 2021; Faenza Bollettino del Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza; Edizioni Polistampa: Firenze, Italy, 2021; pp. 115–123. ISBN 978-88-596-2189-8. [Google Scholar]

- Vella, S.; Bortolussi, C.; Zanardi, B. The Eternal Youth of Capalbio’s Monsters: A Planned Preventive Conservation Project. In The Conservation of Sculpture Parks; Archetype Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; pp. 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Technical Data Sheet: Siox-5 RE20C 2025, SILTEA SRL Via Carlo Goldoni 18, Padova 35131 PD, Italia. Available online: https://www.siltea.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/CONSOLIDANTE-SIOX-5-RE20C-SCHEDA-TECNICA.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Kotlík, P.; Doubravová, K.; Jiˇrí, H.; Lubomír, K.; Jiˇrí, A. Acrylic Copolymer Coatings for Protection against UV Rays. J. Cult. Herit 2014, 15, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalarone, D.; Lazzari, M.; Chiantore, O. Acrylic Protective Coatings Modified with Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Comparative Study of Stability under Irradiation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 2136–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Mason, D. Literature Review: The Use of Paraloid B-72 as a Surface Consolidant for Stained Glass. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2003, 42, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, S.P. The Use of Paraloid B-72 as an Adhesive: Its Application for Archaeological Ceramics and Other Materials. Stud. Conserv. 1986, 31, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koob, S.P. Conservation and Care of Glass Objects; Archetype Publications: London, UK; The Corning Museum of Glass: Corning, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, E.; Chiavari, C.; Lenza, B.; Martini, C.; Morselli, L.; Ospitali, F.; Robbiola, L. The Atmospheric Corrosion of Quaternary Bronzes: The Leaching Action of Acid Rain. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadavecchia, S.; Chiavari, C.; Ospitali, F.; Gualtieri, S.; Hillar, A.C.; Bernardi, E. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Coatings for the Protection of Outdoor Terracotta Artworks through Artificial Ageing Tests. J. Cult. Herit 2024, 70, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavari, C.; Bernardi, E.; Martini, C.; Passarini, F.; Ospitali, F.; Robbiola, L. The Atmospheric Corrosion of Quaternary Bronzes: The Action of Stagnant Rain Water. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 3002–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, L.; Bernardi, E.; Vassura, I.; Passarini, F.; Tesini, E. Chemical Composition of Wet and Dry Atmospheric Depositions in an Urban Environment: Local, Regional and Long-Range Influences. J. Atmos. Chem. 2008, 59, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoncini, A.; Brattich, E.; Bernardi, E.; Chiavari, C.; Tositti, L. Safeguarding Outdoor Cultural Heritage Materials in an Ever-Changing Troposphere: Challenges and New Guidelines for Artificial Ageing Test. J. Cult. Herit 2023, 59, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Della Valle, A.; Becherini, F. A Critical Analysis of One Standard and Five Methods to Monitor Surface Wetness and Time-of-Wetness. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2018, 132, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.D.; Grossi, A. Indicators and Ratings for the Compatibility Assessment of Conservation Actions. J. Cult. Herit. 2007, 8, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, G. Transparent Coating on a Color Surface. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2024, 41, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, A.V.; Bodi, G.; Cernescu, A.; Spiridon, I.; Nicolescu, A.; Drobota, M.; Cotofana, C.; Simionescu, B.C.; Olaru, M. Protective Coatings for Ceramic Artefacts Exposed to UV Ageing. npj Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueli, A.M.; Pasquale, S.; Tanasi, D.; Hassam, S.; Lemasson, Q.; Moignard, B.; Pacheco, C.; Stella, G.; Politi, G. Weathering and Deterioration of Archeological Glasses from Late Roman Sicily. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2020, 11, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicki-Goldfinger, J.J. Unstable Historic Glass: Symptoms, Causes, Mechanisms and Conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2008, 53, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, R.H. CRIZZLING–A PROBLEM IN GLASS CONSERVATION. Stud. Conserv. 1975, 20, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.I.; Clark, G.L.; Alexander, H.W. THE DETERMINATION BY X-RAY METHODS OF CRYSTALLINE COMPOUNDS CAUSING OPACITY IN ENAMELS. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1933, 16, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinet, L.; Hall, C.; Eremin, K.; Fearn, S.; Tate, J. Alteration of Soda Silicate Glasses by Organic Pollutants in Museums: Mechanisms and Kinetics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2009, 355, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, F.; Brunswic, L.; Charpentier, T.; Gin, S. Lead Leaching in Industrial Crystal Glasses. In Lead in Glassy Materials in Cultural Heritage; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 295–330. ISBN 978-1-394-26541-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jialiang, Y. Further Studies on the IR Spectra of Silicate Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1986, 84, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handke, M.; Mozgawa, W.; Nocuń, M. Specific Features of the IR Spectra of Silicate Glasses. J. Mol. Struct. 1994, 325, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laso, E.; Aparicio, M.; Palomar, T. Influence of Humidity in the Alteration of Unstable Glasses. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2024, 15, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussoni, M.; Castiglioni, C. Infrared Intensities. Use of the CH-Stretching Band Intensity as a Tool for Evaluating the Acidity of Hydrogen Atoms in Hydrocarbons. J. Mol. Struct. 2000, 521, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyvandi, A.; Holmes, D.; Soroushian, P.; Balachandra, A.M. Monitoring of Sulfate Attack in Concrete by Al27 and Si29 MAS NMR Spectroscopy. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 27, 04014226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, N.; Ngo, D.; Banerjee, J.; Zhou, Y.; Pantano, C.G.; Kim, S.H. Probing Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions of Water Molecules Adsorbed on Silica, Sodium Calcium Silicate, and Calcium Aluminosilicate Glasses. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 17792–17801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.E.; Folz, D.C.; Clark, D.E. Use of FTIR Reflectance Spectroscopy to Monitor Corrosion Mechanisms on Glass Surfaces. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 2667–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintus, V.; Wei, S.; Schreiner, M. UV Ageing Studies: Evaluation of Lightfastness Declarations of Commercial Acrylic Paints. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 1567–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamuraglia, R.; Campostrini, A.; Ghedini, E.; De Lorenzi Pezzolo, A.; Di Michele, A.; Franceschin, G.; Menegazzo, F.; Signoretto, M.; Traviglia, A. A New Green Coating for the Protection of Frescoes: From the Synthesis to the Performances Evaluation. Coatings 2023, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiantore, O.; Lazzari, M. Photo-Oxidative Stability of Paraloid Acrylic Protective Polymers. Polymer 2001, 42, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, J.; Kanaki, E.; Fischer, D.; Herm, C. Evaluation of the Composition, Thermal and Mechanical Behavior, and Color Changes of Artificially and Naturally Aged Polymers for the Conservation of Stained Glass Windows. Polymers 2023, 15, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandracci, P.; Mussano, F.; Ceruti, P.; Pirri, C.F.; Carossa, S. Reduction of Bacterial Adhesion on Dental Composite Resins by Silicon–Oxygen Thin Film Coatings. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 10, 015017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, Y.; Ando, E.; Kawaguchi, T. Characterization of SiO2 Films on Glass Substrate by Sol-Gel and Vacuum Deposition Methods. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1992, 147–148, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| blue glass | C | O | Na | Al | Si | Sb | Cl | K | Ca | Co | Pb | |||||||||||

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ||||||||||||

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 38.6 | 0.5 | 9.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 24.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 20.1 | 0.7 | |

| orange glass | C | O | Na | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | F | Zn | Cd | |||||||||||

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ||||||||||||

| 1.2 | 0.6 | 41.3 | 0.2 | 18.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 27.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 9.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |||

| orange glass | pre-aging time (p-t) | C | O | Na | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | F | Zn | Cd | |||||||||||

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 41.3 | 0.2 | 18.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 27.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 9.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |||

| Drop (ToW 10d) | 3.0 | 0.6 | 49.8 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 36.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |||||||

| Drop (ToW 20d) | 3.0 | 3.7 | 50.7 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 33.6 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 7.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Drop+CC | 2.1 | 1.0 | 53.4 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 31.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| blue glass | pre-aging time (p-t) | C | O | Na | Al | Si | Sb | Cl | K | Ca | Co | Pb | |||||||||||

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 38.6 | 0.5 | 9.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 24.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 20.1 | 0.7 | |

| Drop (ToW 10d) | 2.6 | 48.6 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 25.5 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 17.2 | 0.2 | ||

| Drop (ToW 20d) | 4.9 | 2.7 | 45.5 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 26.0 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 17.9 | 1.5 | |

| Drop+CC | 2.5 | 0.8 | 47.4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 25.1 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 17.6 | 1.5 | |

| C | O | F | Na | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | Zn | Cd | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 12.4 | 0.2 | 44.9 | 0.3 | 25.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||

| 2 | 12.8 | 0.2 | 45.2 | 0.2 | 24.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 13.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||||

| 3 | 38.9 | 0.6 | 11.7 | 0.7 | 17.9 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 18.6 | 0.3 | 7.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||

| 4 | 15.0 | 0.9 | 48.8 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 26.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||

| 5 | 10.4 | 1.4 | 51.3 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 28.9 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | ||||

| 6 | 11.0 | 1.3 | 50.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 23.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||

| 7 | 29.1 | 1.4 | 40.7 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 15.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 11.8 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||||||||

| C | O | Ca | Na | Al | Si | Cl | K | Sb | Pb | |||||||||||||

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | |||||||||||||

| 8 | 32.7 | 1.3 | 37.5 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 14.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 9.2 | 0.3 | ||

| Orange Glass | Treatment | Aging Time (a-t) | C | O | Na | Al | Si | S | Cl | K | F | Zn | Cd | |||||||||||

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ||||||||||||||

| UT | 0 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 53.4 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 31.1 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| Drop | 3.5 | 1.9 | 50.9 | 0.8 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 32.3 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||

| Drop+CC | 1.8 | 2.5 | 51.6 | 0.4 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 33.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | ||

| Drop+CC+UV | 3.5 | 4.6 | 51.9 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 30.6 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 7.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| Paraloid B72 | 0 | 47.7 | 0.4 | 33.6 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 13.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||||||

| Drop | 44.3 | 4.6 | 33.9 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 16.5 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Drop+CC | 45.7 | 9.3 | 33.1 | 3.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 17.1 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Drop+CC+UV | 34.8 | 12.0 | 39.0 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 20.7 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Siox-5 RE20C | 0 | 16.4 | 0.7 | 44.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 35.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |||||||

| Drop | 17.0 | 2.6 | 44.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 33.8 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | ||||

| Drop+CC | 12.6 | 9.0 | 45.8 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 36.0 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Drop+CC+UV | 9.9 | 8.7 | 46.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 37.8 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||||

| Siox-5 RE39 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 54.5 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 34.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 5.8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |||||||

| Drop | 6.7 | 2.6 | 50.5 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 33.8 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| Drop+CC | 1.0 | 1.7 | 53.1 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 37.0 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 4.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Drop+CC+UV | 3.9 | 0.3 | 51.9 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 34.0 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | ||

| Blue Glass | Treatment | Aging time (a-t) | C | O | Na | Al | Si | Sb | Cl | K | Ca | Co | Pb | |||||||||||

| ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ± | ||||||||||||||

| UT | 0 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 38.6 | 0.5 | 9.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 24.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 20.1 | 0.7 | |

| Drop | 3.4 | 3.2 | 47.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 26.9 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 17.5 | 1.0 | ||

| Drop+CC | 5.2 | 1.3 | 47.3 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 25.8 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 15.8 | 0.4 | ||||

| Drop+CC+UV | 3.3 | 4.7 | 47.3 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 26.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 16.8 | 1.1 | ||

| Paraloid B72 | 0 | 41.6 | 1.1 | 32.4 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 13.8 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 8.7 | 0.3 | |||

| Drop | 42.0 | 7.8 | 31.1 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 15.0 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.2 | 1.1 | ||

| Drop+CC | 51.4 | 9.4 | 27.3 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 11.5 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.1 | 1.9 | ||

| Drop+CC+UV | 51.5 | 3.8 | 27.5 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 11.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.9 | 0.9 | ||

| Siox-5 RE20C | 0 | 17.2 | 3.0 | 44.4 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 34.9 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.3 | |||||

| Drop | 15.9 | 1.4 | 42.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 35.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 0.5 | ||||

| Drop+CC | 16.0 | 0.5 | 42.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 33.0 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 1.7 | ||

| Drop+CC+UV | 14.7 | 0.9 | 42.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 32.2 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.7 | 1.6 | ||

| Siox-5 RE39 | 0 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 52.4 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 28.3 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 11.1 | 0.2 | |||

| Drop | 8.1 | 1.4 | 48.4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 27.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.1 | 2.2 | ||

| Drop+CC | 7.1 | 2.5 | 48.6 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 27.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.5 | 3.2 | ||

| Drop+CC+UV | 5.0 | 3.2 | 50.0 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 29.8 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 10.6 | 1.7 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Schiattone, S.; Tomiato, E.; Bernardi, E.; Zangari, M.; Salzillo, T.; Vandini, M.; Chiavari, C. Degradation of Traditional Silicate Glass and Protective Coatings Under Simulated Unsheltered Conditions. Heritage 2026, 9, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010002

Schiattone S, Tomiato E, Bernardi E, Zangari M, Salzillo T, Vandini M, Chiavari C. Degradation of Traditional Silicate Glass and Protective Coatings Under Simulated Unsheltered Conditions. Heritage. 2026; 9(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchiattone, Sofia, Elisabetta Tomiato, Elena Bernardi, Martina Zangari, Tommaso Salzillo, Mariangela Vandini, and Cristina Chiavari. 2026. "Degradation of Traditional Silicate Glass and Protective Coatings Under Simulated Unsheltered Conditions" Heritage 9, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010002

APA StyleSchiattone, S., Tomiato, E., Bernardi, E., Zangari, M., Salzillo, T., Vandini, M., & Chiavari, C. (2026). Degradation of Traditional Silicate Glass and Protective Coatings Under Simulated Unsheltered Conditions. Heritage, 9(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010002