1. Introduction

Numic-speaking people (such as the Northern Paiutes, Southern Paiutes, Owens Valley Paiutes, Utes, and Western Shoshone) generally agree that they were Created in the western United States. Southern Paiute specify that all humans were Created in the Spring Mountains (or massif) located along the Pleistocene ecosystem that is centered along the ancient Las Vegas River. From this point of human Creation, they all dispersed to lands that would become their homelands. Additionally, most Native American Southwestern U.S. tribes and pueblos, including all Southern Paiute people, have a place where the people of their local groups (known as districts or bands) emerged during a Second Creation. Similarly to most Numic people, the Utes, Owens Valley Paiutes, and Western Shoshone recognize two Creation locations that are both visited in prayer, song, and in person to Celebrate Creation.

This paper is about a particular second Creation Place for Native Americans. The ceremonies at this location were marked by peckings. The paper is based on ethnographic interviews from six U.S. federally funded studies involving thirteen participating tribes and pueblos, whose representatives provided interpretations. According to Paiute elders who viewed the peckings, they were clearly commemorating a Southern Paiute Ocean Women Creation story (which is discussed later in this article). The cultural practice of making this Origin Burden Basked ceremony continued as a heritage activity into more recent times, as demonstrated by the basket on display at the Moab Museum, which was found in a cave along the Colorado River (

Figure 1). The oral history and archaeological evidence at this location suggest that it was a separate site of a Second Creation and celebration of that event, and that it may have been jointly used by Southern Paiutes, Utes, and other tribes and pueblos.

Intellectually, the analysis of this paper is framed by emerging terms and theories developed by scholars contributing to World Heritage interpretations, as defined and broadly accepted by the United Nations [

1,

2]. As such, the ethnographic heritage analysis builds on the burgeoning academic literature that has responded to the United Nations’ call for the identification of geological places and landscapes as cultural heritage that deserve preservation [

3,

4,

5]. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [

5] and the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) [

6] have a Geoheritage Specialist Group that has documented the need for such new heritage preservation approaches [

5]. This need is highlighted by the 20 published peer-reviewed papers in the Special Issue of the journal

Land, entitled Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism—Linking Geology, Geoheritages, and Geoeducation, edited by Brocx and Semeniuk.

The International Union on Geoheritage has responded by identifying significant geosites around the world using both their scientific and human significance as criteria [

5]. Illustrating our knowledge of and commitment to these UN goals, the authors of this manuscript have conducted research that argues for cultural heritage attachments to geosites when they are both geologically recognized as important to science and viewed by Native Americans as sentient and alive. These ethnographic research studies involve (1) more than 2000 living stone arches in a national park [

7], (2) portals to other dimensions through the openings of living stone arches [

8], (3) some of the largest living stone bridges in North America [

9], (4) a pilgrimage to a massive living volcano [

10], and (5) ceremonies at a living and active volcanic lava flow [

11]. In addition, the authors have contributed to the successful listing of Devils Tower, Mateo Tepe as one of the IUGS Second 100 USGS Geological Heritage Sites [

12]. The designation encompasses both Native American Heritage and Geological Science dimensions, which is in keeping with UN recommendations of combining the two for the purpose of heritage preservation, interpretation, and management.

2. Background

This analysis is situated within a series of progressively smaller geological regions or nested geoscapes, each of which contains geosites and geotrails that play a prominent role in Native American heritage. Over tens of thousands of years, Native American cultures and the region’s environment have co-evolved, each shaping and being shaped by the other through ongoing processes of adaptation, interaction, and meaning making. While the contributions have varied over time, the regions have collectively fostered an environmental understanding and cultural responses to shifts in species, climate, and to other people—and as such the culture has co-developed with the environment. In order to situate the interpretations of the rock peckings of the Colorado river, the topographical and climatological background of the analysis is presented by geological scale as (1) the western United States, (2) the Colorado Plateau, (3) the Mesa Verde World, and (4) the American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River.

2.1. The Western United States

The western portion of the United States has a long and complex geological history; however, for this Native American heritage analysis, two results of that geological past are particularly relevant [

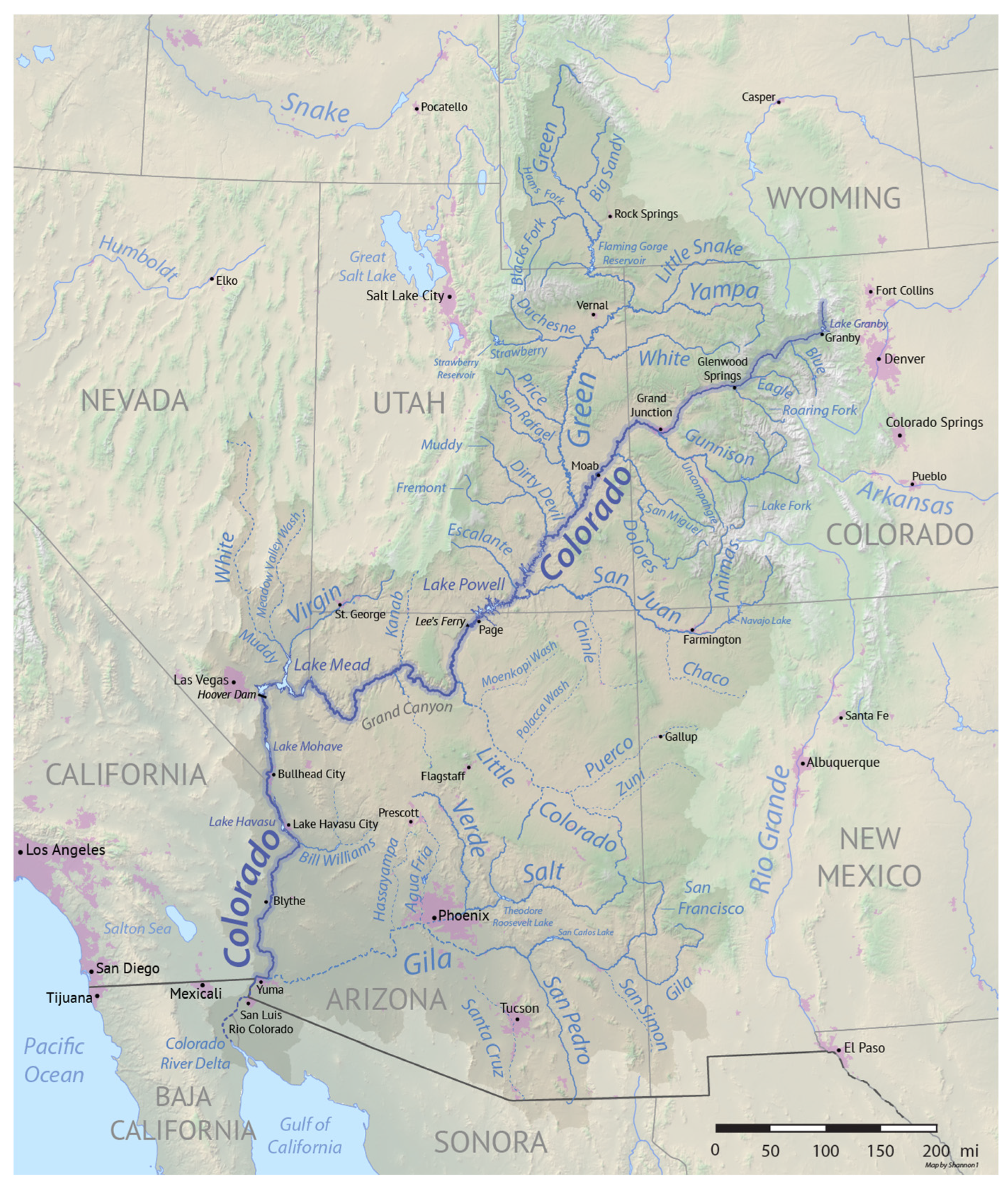

13]. After millions of years of tectonic shifts and ocean movements, the western U.S. is now characterized by a massive internally drained geological bowl, which is called the Great Basin. It comprises a hydrological system of small rivers that join to form the Colorado River, which drains the expansive Colorado Plateau (

Figure 2). The Great Basin has largely retained its water, thus forming, at various times, massive lakes. During drastic climatic shifts, these internal hydrological features have created unique wetlands, ponds, and sedimentary deposits that have both attracted and captured the Ice Age Megafauna. While the Great Basin slowly filled and emptied, the Colorado River finally found its way to the Gulf of California through a series of connected rivers, being linked a short 5.6 to 4.1 million years ago [

13]. Now, the extensive western ocean deposits were finally draining to the sea, and from this time forward, the Colorado River carried millions of years of ocean deposits out of the Southwestern U.S., forming an increasingly deep system of canyons ending in the underwater delta of the river in the Gulf of California. This hydrological system is both understood and celebrated in Native ceremonies.

The geological period known as the Pleistocene began approximately 2.6 million years ago and lasted until the Holocene, which began around 11,700 years ago. The Pleistocene Ice Age consisted of 13 glacial and interglacial cycles, which occurred and eventually covered most of North America with periodic warmer periods called pluvials, during which there was more precipitation and less evaporation. Most of the Megafauna found in the fossil record of this region lived during this epoch. Science has now confirmed Native American presence in the American Southwest from 22,000 years ago at White Sands National Park in New Mexico [

14,

15] and from 37,000 years ago in a deposit interpreted as a Columbian Mammoth (

Mammuthus columbi) kill site on the Rio Puerco, New Mexico [

16]. These new scientific findings extend the known period of human settlement on the continent and, as such, have broken the ‘Clovis Glass Ceiling’ that has dominated discussions of the Native American past in North America for more than 75 years [

17].

The panoramic painting created by artist Karen Carr for White Sands National Park (

Figure 3) is an artistic interpretation of Native American life 22,000 years ago during the Pleistocene epoch [

6]. Her art offers a glimpse into what daily life looked like across the Southwestern U.S. during this time.

Figure 3 was commissioned by the NPS for White Sands National Park after it was scientifically proven accurate by dating fossil footprints in an ancient lake where both Native children and Megafauna were present in the park 22,000 years ago. Instead of just converting this new scientific fact into text or verbal accounts by the interpretative rangers, the park commissioned a painter to prepare displays for the park visitors.

The confirmation of the 22,000 BP date at White Sands National Monument caused other archaeology sites of this age to emerge across North America, such as Parsons Island, Chesapeake Bay [

19,

20]. About this same time, the earliest date for the occupation of North America of 37,000 BP was established from the Rio Puerco, New Mexico [

16]. This revised date extended the temporal framework for analyzing Native presence in the Americas by more than 25,000 years, shifting it from the previously accepted benchmark of around 12,000 BP. The conceptual temporal shift for talking and studying about Native American activities in North America has been termed “Breaking the Clovis Glass Ceiling” [

17].

2.2. The Colorado Plateau

The Colorado River is a central cultural and geographical feature that links places across the Colorado Plateau—a region deeply embedded in the histories and lifeways of Native American peoples [

16], including the Numic-speaking peoples—Utes, Southern Paiutes, and Owens Valley Paiutes. From a Numic perspective, the river is one of the important veins of Mother Earth, and all the tributaries that flow into the river make up the functionally integrated sacred areas of the Colorado Plateau watershed (

Figure 4). A tribal elder offered the following environmental interpretation during ethnographic interviews conducted along the Colorado River [

21]:

Piapaxa‘uipi: The river there is like our veins. Some are like the small streams and tributaries that run into the river there. So, the same things; it’s like blood—it’s the veins of the world... This story has been carried down from generation to generation. It’s been given to them by the old people... it would be given to the new generation, too.

Like the hydrological veins of the Colorado Plateau, the ancient American Indian trail that crosses the Colorado River is both unique and sacred, holding a vital place in the heritage landscape perceptions of dozens of tribes for over ten thousand years.

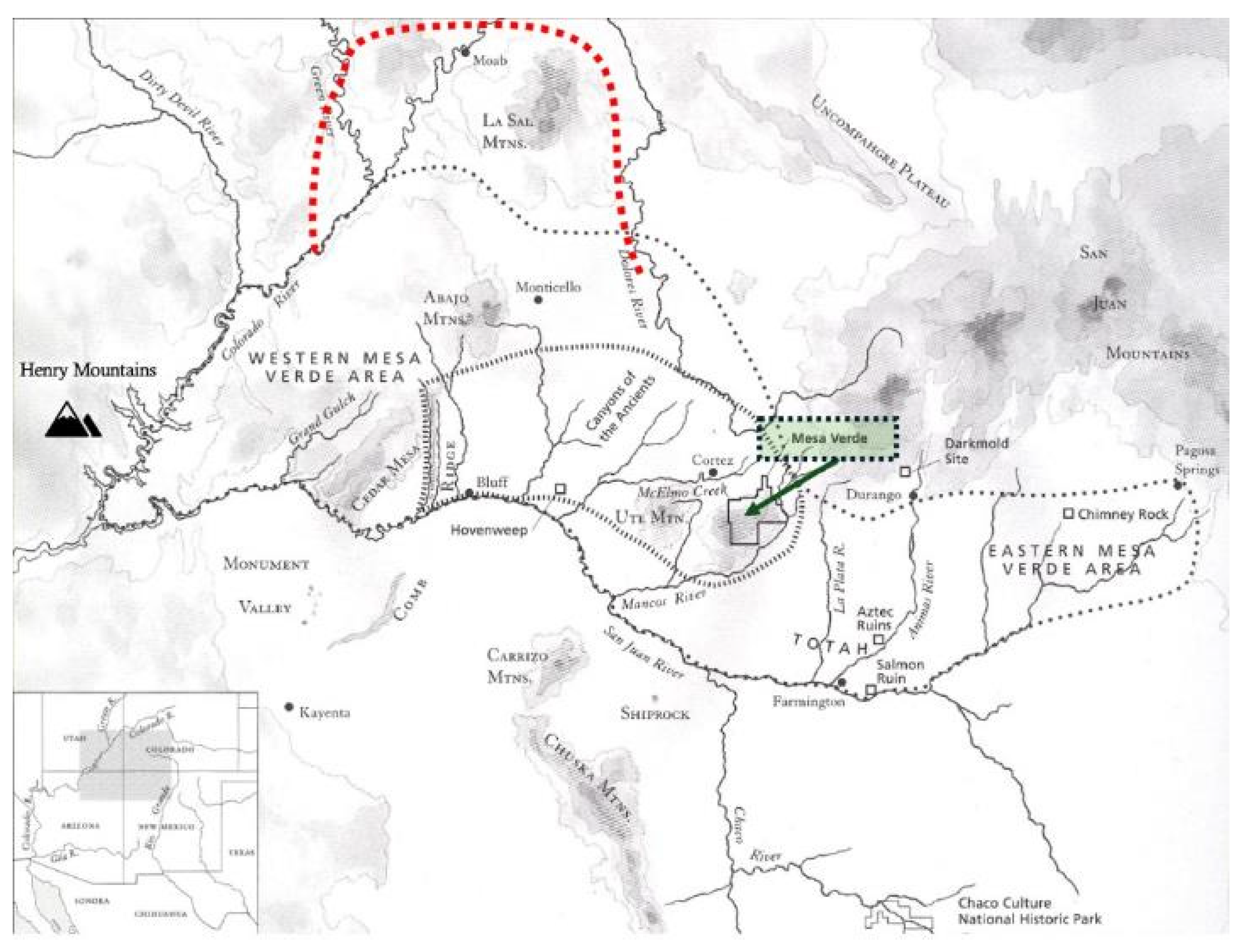

2.3. The Extension of the Mesa Verde World

The concept of the Mesa Verde World describes a large, culturally integrated region occupied between AD 500 and 1300, initially defined by Noble et al. [

22], and refined by subsequent scholarship [

23,

24,

25,

26]. It spans from the Colorado River in Utah to Pagosa Springs, Colorado, and from the La Sal Mountains to the San Juan River. Archaeologists now view the Mesa Verde World not as centered on Mesa Verde proper, but as encompassing extensive farming and ceremonial communities across areas such as the Great Sage Plain and Moab (see

Figure 5).

Ethnographic studies and recent archaeological surveys—including those related to Bears Ears and the Canyons of the Ancients—support population estimates of up to 80,000 people during the peak period [

22,

24,

26]. This includes agricultural and ceremonial settlements in Arches [

27], Canyonlands [

28], Hovenweep [

29], and Natural Bridges [

9]. These findings confirm that the Mesa Verde World extended into the Moab area and centered along the Colorado River, integrating both irrigated and dryland farming communities.

Based on the referenced studies and the oral histories from our studies, we suggest that another 10,000 people lived within these northern areas (

Figure 5). All four areas were primarily used for ceremonies; however, each had large agricultural communities nearby [

7,

30,

31]. Were these estimates to be further verified by archeology surveys and analyses, it would support the conclusion that a massive, socially and culturally integrated society of approximately 80,000 people lived in the Western and Central Mesa Verde World. These Native people and their ceremonial leaders were the primary active participants at the Creation Basket Pecking Panel.

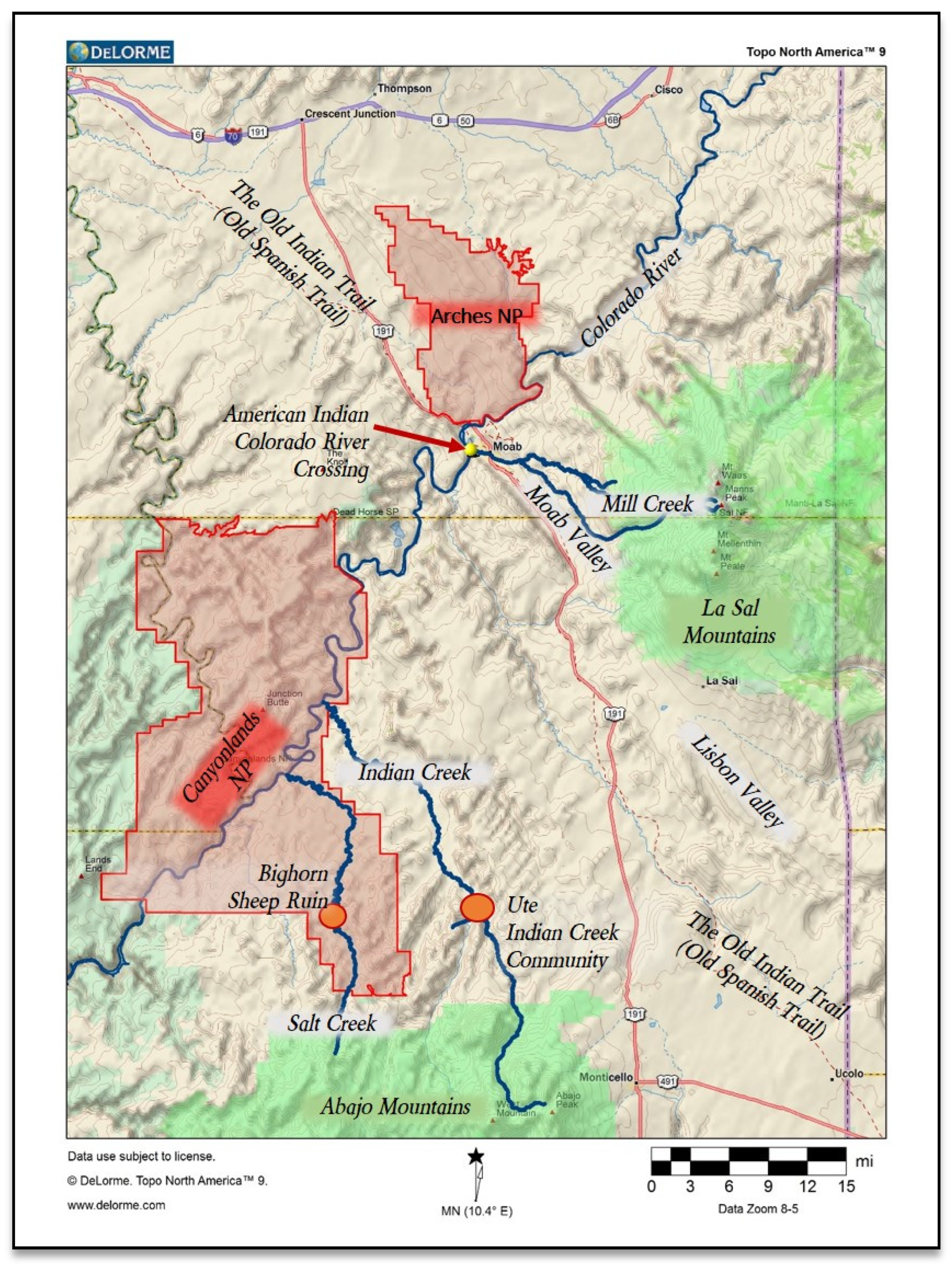

2.4. The American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River

Native Americans have many special and ancient Heritage Places of shared cultural significance located along the Colorado River and in the surrounding region, called here the American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (

Figure 6). Among the most significant are locations where individuals and groups gathered to conduct World-Balancing ceremonies—typically situated where the Colorado River is constricted by geological features and canyons. These places can only be fully understood in cultural terms through their embeddedness in geological formations, mountainous landscapes, and broader patterns of human society and ancient history.

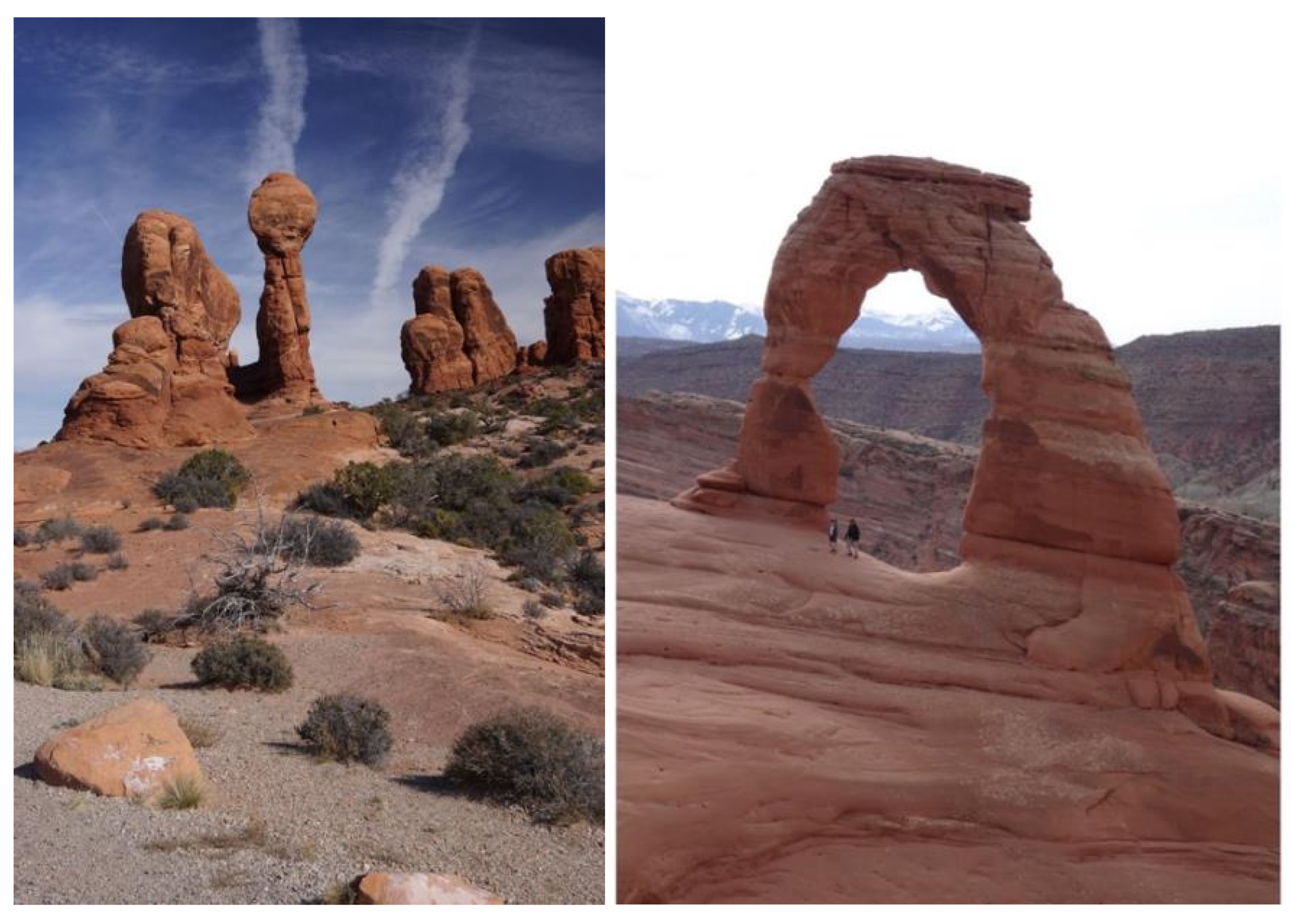

The landscape surrounding the AICC supported major irrigated farming communities in the Moab Valley, Castle Rock Valley, and Salt Creek. Ceremonial use of the Colorado River was widespread. Arches National Park to the northeast contains over 2000 stone arches used for timekeeping and ceremonial portals. Canyonlands National Park to the south features high mesas, eroded canyons, and sacred sites in both the park and nearby mountains. There, the Green and Colorado Rivers join, sending prayers for balance downstream.

Figure 7 illustrates this topographical diversity, from the Las Sal Mountains—a Sky Island Massif visible from Arches—to the eroded buttes near traditional farms in Castle Valley.

The photos in

Figure 8 are of Canyonlands National Park to the south of the AICC with the Abajo Mountains (a sky island massif). To the right is lower elevations in Canyonlands, where quiet streams provided large villages of Native people with irrigation for fields of Native food plants. Such villages existed for more than a thousand years (AD 500 to AD 1300) along Salt Creek that brings water from the Abajo Mountains Massif. Near the Salt Creek farming villages were sandy flats that provided abundant habitat for the dryland horticulture of traditional plants, such as Indian Rice Grass (

Figure 8).

While the primary traditional Native American trail through the area crosses the Colorado River near Moab, Utah, the broader region is crisscrossed with pilgrimage trails that carried travelers and prayers to dozens of known heritage locations (

Figure 9).

The AICC geoscape has been the focus of human activities for thousands of years, likely dating back to at least 37,000 years ago [

16]. Trade, ceremony, livelihoods, and residence are all uses of this location. Trails to and from the crossing have been developed and culturally constructed based on their locations and destinations. These major trail networks are still viewed as sacred by Native Americans.

Figure 10 is an image of the AICC at Moab. The geosite that is the focus of this analysis is where the river enters Meander Canyon south of Moab.

Figure 11 shows Vulcan’s Anvil, a remnant volcanic plug in the Colorado River at Lava Falls in Grand Canyon National Park. It formed during a series of massive magma flows that temporarily dammed the river, creating lakes upriver. As the river eventually eroded these dams, the plug remained and became a pilgrimage site for spiritual learning and healing, traditionally visited via long-established trails documented in ethnographic studies.

The canyons linked to the Colorado River form a spiritually powerful corridor infused with puha, or Creation energy. Spanning over 800 miles from Moab, to Needles, California, this chain includes seven major canyons—Meander, Cataract, Glen, Marble, Grand, Boulder, and Black. Of these, Moab Meander, Glen, Grand, and Black Canyons are the most documented ethnographically. Knowledge of sacred places and areas of ceremonial significance across these canyons has been documented through systematic ethnographic studies conducted by the authors. Official tribal governments participated in these efforts to help inform public and land managers of the need for culturally sensitive approaches to land and water management.

3. Methods

Native American heritage interpretations that form the foundation of this heritage analysis derive from six ethnographic studies funded by the U.S. National Park Service and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. These studies were directed by Drs. Stoffle and Van Vlack, who are the senior authors of this analysis. Dozens of additional scholars, including Heather Lim, made significant contributions to the studies. Ethnographic understandings of AICC regional geosites, geotrails, and geoscapes further derive from more than a dozen ethnographic studies involving these Native cultural groups, conducted by the authors.

The approaches of these studies apply a cultural heritage assessment framework modeled on the principles outlined in social impact assessments (SIAs) for Indigenous communities [

32]. Specifically, it follows a methodology that foregrounds tribal consultation, cultural landscape interpretation, and collaborative knowledge production. As such, the six ethnographic reports informing this analysis were not treated as mere data points but as expressions of sovereign cultural knowledge. The study privileges Indigenous narratives and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) through semi-structured interviews, oral histories, and spatial mapping techniques conducted in cooperation with tribal representatives.

Aligned with best practices in cultural heritage SIA, the research process integrated interdisciplinary methods—combining archaeology, ethnography, and historical ecology—to identify culturally significant places, including ceremonial sites and agricultural zones, within the broader Mesa Verde World. Emphasis was placed on Indigenous perspectives of landscape continuity, including connections between ancestral practices and contemporary cultural responsibilities. All interpretations were validated in dialogue with participating tribes and pueblos, in keeping with ethical standards of informed consent and representational authority. This approach situates the analysis not just within empirical archaeological frameworks but also within the lived cultural geographies articulated by descendant communities, thus reframing the Mesa Verde World as a dynamic heritage landscape co-produced through both material and intangible dimensions. As outlined in the Introduction, the study further aligns the interpretation of the paper with the UNESCOS contemporary approach to geoheritage that integrates geological features and landscapes with cultural history and cultural understandings.

The 13 Native American tribes and pueblos who participated in the 6 ethnographic foundation studies are listed in

Table 1 by tribal and study names.

Tribes and pueblos were invited to participate in these ethnographic studies, and each appointed representatives to provide cultural interpretations and recommendations to the sponsoring federal agencies. The recommendations were reviewed, edited, and approved by the participating tribes and pueblos. Ethnographic observations and recommendations were intended to be publicly available, thereby producing actionable cultural data for visitor interpretation and agency management. Our ethnographic field methods have been described and published elsewhere [

35]. Together, these six ethnographic studies involved 33 field sessions for 13 tribes and pueblos. These ethnographic field collection events form the foundation of this analysis regarding Native interpretations of the Moab Creation Basket Panel and surrounding geotails and geoscapes.

4. A Place of Creation Ceremony

The pecking panel, which is the focus of this analysis, is located south of Moab, where the Colorado River enters a steep-walled downriver canyon. This canyon marks the beginning of a more than 100-mile stretch in which the river is confined. As it flows through Meander Canyon, the Colorado River initially becomes deeper and calmer, but it eventually develops into churning rapids. The major constriction of the river at Meander Canyon, near Moab, is evident in the upper portion of the image (

Figure 12).

The American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (AICC) begins at the upper left corner of the image. The long agricultural Moab Valley is geologically remarkable inasmuch as it was created through the collapse of a massive salt dome, which is a very ancient ocean-based salt deposit [

36].

In many areas, Highway 191 follows the route of the AICC and portions of the traditional Native geotrail leading into and out of the crossing (

Figure 12). The Moab Valley was, for approximately a thousand years, from AD 500 to AD 1300, a traditional irrigated farming area populated with villages [

37].

Moab was a significant place for both spiritual activities, the cultivation of domestic crops, and the conduct of trade with people from distant communities. Trade with the latter included woven items from native cotton. Note the spindle whorls that were found during the archaeology excavation of the Pit House (or Kiva), discussed in the final portion of this analysis.

The geosite, which is the focus of this analysis, is indicated in the remote image presented in

Figure 13. The Burden Basket Panel is located in a narrow portion of the canyon and is immediately next to the western bank of the Colorado River. Across the river lies another culturally significant geosite, called Moonflower Canyon, which is significant for a broader Native interpretation of the geoscape area but is not included in this analysis.

The geological location of the Burden Basket Panel is unique in many ways. (1) It is at the beginning of a major constriction of the Colorado River, (2) it has been placed on a sheer cliff that is one of the highest portions of the canyon, (3) it faces to the east, and (4) it is located immediately next to the river (

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). Ceremonial activities, such as the dances depicted in the panel, would occur within the “smell of the river,” according to one tribal representative.

When the appointed tribal representatives shared cultural insights at the Burden Basket Panel (

Figure 16), they maintained that the Burden Basket Pecking had to be very old, given that it had a patina over it. Elders also noticed the height of the peckings above ground (

Figure 16). Some said it marks one or more portals to other dimensions, much like those that occur through the opening of the 2000 sandstone arches to the north.

This analysis begins with detailed cultural interpretations of two distinctive peckings. It is essential to understand that the geosite, the AICC geotrail, and the regional geoscape are being interpreted by representatives of the 13 tribes and pueblos who participated in the 6 ethnographic studies outlined in the

Section 3. While the Burden Basket Pecking is used in this analysis as the term of reference for the larger panel, it represents only a portion of what the pecking on the panel entails. Tribal representatives from all the participating cultures understand and express their ancient heritage connections with the geosite. As mentioned in the Introduction, it is common among tribes and pueblos of the Southwestern United States to identify a primary place of Creation for all humanity and a Second Creation place for a recognized local social group who are a portion of the larger society.

The elders stipulated that this and other nearby peckings (

Figure 17 and

Figure 18) represent the ancient people, often referred to in the Paiute language as the

Enugwuhype. One tribal representative stated that the peckings represent the Southern Paiute origin story and how Ocean Woman (

Hutsipamamaun;

Sichompa Kagon) carried all of humankind in her Burden Basket from the ocean to far inland and how, because of an early opening of the basket, the Southern Paiutes were placed in their traditional homelands. The dancing figures along the Moab Pecking Wall were interpreted as a part of a Celebration of a Second Creation geosite conducted at that location along the Colorado River.

The following origin account was first recorded by John Wesley Powell in the 1875 [

38]:

Sichompa Kagon (Ocean Women) came out of the sea with a sack (also Burden Basket) filled with something and securely tied. Then she went to the home of the Shinauav brothers carrying her burthen with her, which was very heavy, and bent her nearly to the ground. When she found the brothers, she delivered to them the sack and told them to carry it into the middle of the world and open it and enjoined upon them that they should not look into it until their arrival at the designated point and there they would meet Tavwots, who would tell them what to do with it. Then the old woman went back to the sea disappearing in the waters.

Shinauav Pavits gave the sack to Shinauav Skaits and told him to do as Sichompa Kagon had directed and especially enjoined upon him that he must not open the sack lest some calamity should befall him. He found it very heavy and with great difficulty he carried it along by short stages and as he proceeded, his curiosity to know what it contained became greater and greater. “Maybe,” said he, “it is sand; maybe it is dung! who knows but if the old woman is playing a trick!”

Many times, he tried to feel the outside of the sack to discover what it contained. At one time he thought it was full of snakes: at another, full of lizards. “So,” said he, “it is full of fishes.” At last, his curiosity overcame him, and he untied the sack, when out sprang hosts of people who passed out on the plain shouting and running toward the mountain. Shinauav Skaits overcome with fright, threw himself down on the sand. Then Tavwots suddenly appeared and grasping the neck of the sack tied it up, being very angry with Shinauav Skaits. “Why,” said he, “have you done this? I wanted these people to live in that good land to the east and here, foolish boy, you have let them out in a desert.”

The location of the original opening of the Burden Basket is understood as the Spring Mountains massif along the Las Vegas River. Some people indicate the location more specifically on the northeastern flank of Spring Mountains near Corn Creek. A Second Opening or Creation Event occurred for all people in their homelands.

Another crucial component for interpreting the Burden Basket portion of the panel is a seven-foot-long pecking of a Knotted String, which is a heritage component of all the participating tribes and pueblos as well as among the cultures along the Andes in South America [

39] (

Figure 19). The Knotted String is called the Khipu in Quechua, the language of the Inca in Peru. The Khipu were carried by runners and were used to keep records and convey information (ibid). They served many functions in the Incan Empire, where they fulfilled well-known cultural roles in communication and ceremony. They are now being called by scholars the Computer of the Incas.

In the Southwestern U.S. the Knotted Strings were used to coordinate the Native revolt of the tribes and pueblos against the colonial Spanish in 1680. Runners delivered specially prepared Knotted Strings in order to coordinate the rebellion in Northern New Spain, which today is called New Mexico.

Each Native American cultural group has their own term for the Knotted String. It is called tapitcapi in the Paiute language. Given that the Burden Basket Pecking is generally recognized as a key symbol of Paiute culture, this portion of the analysis draws upon that cultural group.

The large Knotted String Pecking is located just below the Burden Basket Pecking. Tribal representatives interpreted the Basket and Knotted Strings to be deliberately together in a single large panel located high on the wall and away from other peckings.

Traditionally, Southern Paiute groups planned important events and ceremonies by sending runners from village to village across the Southern Paiute Nation carrying the

tapitcapi. The number of knots signified the number of nights before a ceremony would begin, and it was the runner’s responsibility to inform people where the ceremony would occur. Peckings of the Knotted String have been repeatedly interpreted in ethnographic studies as marking the passing of spiritual people along a pilgrimage trail. Such trails occur as the spiritual people move toward and away from ceremonial destinations [

40].

According to the tribal representatives who shared cultural insights at this site, the presence of a long, elaborate Knotted String petroglyph was interpreted as distinct and meaningful. Unlike markings found along typical pilgrimage routes, this pecking area was understood to hold deeper spiritual and cultural significance. The extended length and intricacy of the Knotted String were seen as appropriate for a major ceremonial destination—possibly a World-Balancing location—rather than a transitional stop along a sacred journey.

Portions of the images of the

tapitcapi panel have been color-enhanced and enlarged for further discussion (

Figure 18 and

Figure 19). The first image enhancement involves what appears to be a single mountain sheep undergoing a transformation, moving through a portal. The hooves are typical of mountain sheep, which have transformed into another dimension to serve as spirit helpers for medicine persons [

31].

Note that the first and second sets of Knotted Strings are separated by a ceremonial figure who is connecting them with lines. Also present is a mountain sheep, which, according to representatives, is a spirit helper and often associated with rain.

Tapiticapi rock pecking and paintings serve to mark ceremonial locations and pilgrimage trails [

41]. Knotted Strings are traditionally associated with medicine people or Puha’gants, especially those involved with coordinating activities at ceremonies and along pilgrimage trails.

Dancing in Celebration

A consistent cultural interpretation by tribal and pueblo representatives of the various peckings at this geosite is that people came to this location to celebrate and to seek individual, group, and world balance. A significant component of these activities is dances.

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 illustrate two lines of the figures who are conducting dances hand to hand according to tribal land pueblo representatives. The large lone figure with a headdress, positioned below the dancers, was interpreted by some of the tribal representatives as a dance leader or coordinator.

Near the dancers are Spiritual Beings who are also in motion (

Figure 22). They were interpreted by Native representatives as sharing a role in the dances (

Figure 23 and

Figure 24). Such images as these occur throughout the panel, interspersed with dancing figures and symbols.

As one of our ethnographic guidelines, we do not interpret images that have not been interpreted by Native representatives. The photo below (

Figure 25), however, was selected by a pueblo representative participating in one of our ethnographic studies and interpreted as being of cultural interest. The overall meaning of the images on the river-facing wall was interpreted as Spiritual Beings who were sharing a role in the ceremonies (

Figure 26 and

Figure 27).

A painting on a pot in the collection of Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum in Blanding is shared for comparison (

Figure 27). The pot is from excavations to the south near Bears Ears. A figure on the pot is very similar to one in the center right of the panel photo above that has been rendered.

The figures on the pot are about water, and it has been suggested that they represent ceremonial activities associated with the Colorado River. The headdress or appendage from the head of the Spiritual Being holding the bow and arrow is like that from the pecking panel, which is a rendered image in

Figure 28. The Spiritual Being on the pot is adapted to the water, given that it has fins and webbed feet.

On a full panel located around a corner of the river-facing pecking wall are additional images of dancers (

Figure 28). Like those on the main river-facing wall, these dancing figures are holding hands. These figures too are surrounded by animal images, which were thought by tribal and pueblo elders to be Spirit Helpers. A curved vertical line at the far left of the panel was interpreted as either a rattlesnake or a symbol of the river.

The animals, diagrams, and dancers of this panel are enlarged and colorized for contrast (

Figure 29). In this enlarged image, the modified hooves of the mountain sheep can be seen, indicating it had been transformed in another dimension and passed through a portal to this dimension.

Although these dancing figures are holding hands like others on the river-facing panel, these figures all have headdresses. A mountain sheep with transformed hooves occurs above the dancers. The dancers may be transformed humans who have emerged from a portal to return to this dimension as medicine people, religious people, or one of more than a dozen kinds of Shamans [

42].

5. The Pit House or Kiva

A Pit House or Kiva was physically attached to the river-facing side of the Burden Basket Pecking wall. According to tribal and pueblo representatives, it served as a place for the ceremonial leaders to prepare themselves for events during which they serve as spiritual leaders. Participating in such ceremonies are much larger groups, which are represented by peckings on the wall. A pecking of some dancers and a dance leader can be seen in

Figure 30 and

Figure 31.

The cliff face served as the back wall of the Pit House. While tribal representatives understood the archaeological use of the term “Pit House,” they preferred the term “Kiva,” which better conveys the cultural significance of the structure and is subsequently used in further analysis. According to tribal representatives, a house would be constructed near agricultural fields and other homes and would not be built on a ceremonial wall within a few yards of a massive river.

It is important to recognize that the widening of Utah State Highway 278 occurred in 1961. It was a time with few heritage regulations and even fewer professionally trained local scholars. So, the excavation was conducted by members of an amateur archaeology society headquartered in Moab. There is no implied criticism of their efforts, but it does explain why no tribal people were consulted about the impending “salvage archaeology excavation” and why it took 20 years before any record of the excavation was made public [

43].

Tribal and pueblo representatives cautioned that their interpretations were limited by the excavation of the Pit House (Kiva), the removal of artifacts, a lack of photos, and that the excavated Kiva was filled in to serve as a foundation for the new highway. Nonetheless, tribal representatives maintained that the ceremonial songs performed in the Kiva and in front of the pecking wall remain and can be understood by cultural tribal representatives. These voices from the past, combined with traditional knowledge of the geosite itself, now permit some additional and new interpretations.

In 1961, during the road construction of Utah Highway 278, a Kiva was excavated. The Kiva was approximately 5 ½ feet deep and was circular in structure, with masonry lining [

43]. In the center of the structure was a circular adobe-rimmed fireplace that was 25 inches in diameter and 4 inches deep. Holes were dug in the floor southeast and southwest of the fireplace [

43]. To the north of the fireplace was a large flat sandstone slab that had scratched grooves. On top of the fireplace, a thin rock slab was documented, and it was believed that it was used as a cooking slab or

comale. The cliff face served as the back wall of the Kiva [

43].

Above where the Kiva roofline meets the rock wall is a series of ground holes in the wall and peckings that include images of mountain sheep and vulva-shaped cupules (

Figure 32) [

43]. Such peckings and ground holes or cupules were interpreted by tribal representatives as being used in celestial time-keeping and related ceremonies, where the circle holes represent planets or bright stars.

Ethnographic comparisons are useful for framing discussions. The purpose of the indented circles, which occurred at the rooftop level, can perhaps be expanded with ethnographic interpretations from elsewhere. Similar circles ground into vertical and horizontal sandstone surfaces were identified by ethnographic interviews on Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Park, Tonto National Monument, and the Cajon Group in Hovenweep National Monument. In all these cases, the smooth and deep holes, often called cupules by archaeologists, were identified as serving time calculations, celestial markings, and ceremonies involving solar system planets. Places with such rock indentations were interpreted as the center of a secret Kiva society from at least one of the contemporary New Mexico pueblos.

Figure 33 and

Figure 34 are offered here for comparison with the cupules found above the Kiva at the pecking wall. Near the top of Fajada Butte were a dozen rooms, now identified by tribal representatives as for teaching about the celestial system and telling time. Near the roofs of these rooms are various calendars, peckings, and cupules that have been identified as representing clans, origin beings, ancestral beings, and physical representations of time. In accordance with traditional and contemporary use patterns of pueblo households, the roofs of these rooms were seen as appropriate places to study, teach, and record the movements of the stars, sun, and moon [

44].

Here, we continue with Pierson’s description of the Kiva 1960 excavation. Found on the floor and in the fill of the Kiva were a quartz hammerstone, a mano, a flesher/scraper, two burned corn cobs, fourteen side-notched square-based points, two drills, four black-on-white sherd spindle whorls, one graver, one large bone bead, several small stone, bone, and shell beads, and two bone dice [

43].

Half of the pottery sherds found in the Kiva were identified as Mancos Black-on-White, which is typically dated from AD 920 to AD 1180 [

45]. The other half of the pottery sherds were identified as corrugated ware, which are difficult to date, but nearby were sherds of Tusayan Polychrome, which is typically dated from AD 1110 to AD 1320. Also on the floor were a polished red sherd and an unidentified black-on-white sherd with an indented corrugated exterior [

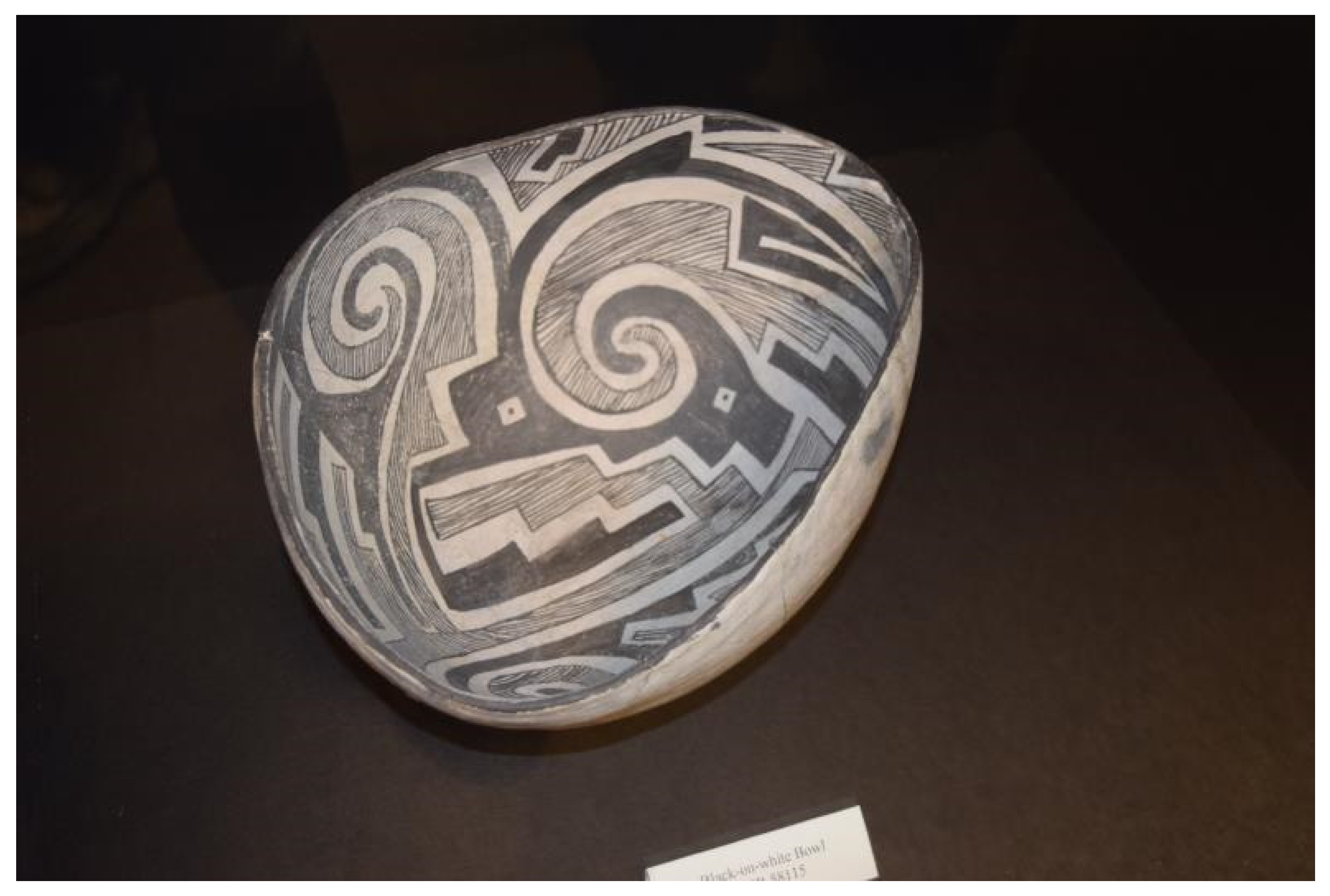

43]. A Mancos Black-on-White bowl excavated to the south of the panel is expected to be made at about the time of similar sherds in the Kiva (

Figure 35).

Mancos Black-on-White style pottery occurs throughout the region, far beyond the AICC study area, suggesting conceptual and social interactions between people over a broad area from Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, to Moab. The authors have argued elsewhere that the people in the AICC were culturally and socially integrated into a larger society that is called by archaeologists the Western Mesa Verde World [

31]. If the theory of regional cultural integration continues to gain support, it suggests that the Moab Burden Basket Pecking panel and Kiva were used in ceremonies by people from distant regions for over a thousand years. Such an assessment is in line with the views of the tribal and pueblo representatives who participated in the panel during our studies.