3.1. Painted Tiles

The “painting” on ceramic pieces can be achieved through the use of various mediums, including enamels, slips, oxides, and pigments, either to provide comprehensive coverage of the object’s surface or to create intricate patterns and compositions. In academic discourse, painted tiles are frequently associated with ceramic pieces decorated akin to a canvas, typically characterised by brushstrokes of colour, forming compositions inspired by Renaissance aesthetics. Examples of such texts include those emphasising the development of painted maiolica, a technique in which Italy fully exploited the artistic potential of tiles as early as the 15th century [

19], and the production of Sevillian tiles (also known as

planos or

pisanos), which originated with the Italian ceramicist Francisco Niculoso, who established himself in Seville in the late 15th century [

20].

However, the origins of painted tiles predate the Renaissance, with examples existing long before the advent of this artistic movement. The earliest recorded use of painted tiles as architectural cladding is evidenced in the step pyramid of Pharaoh Djoser (2667–2648 BCE) in Saqqara. In this complex, the walls leading to the Royal Chamber were adorned with thousands of rectangular, blue-glazed tiles, intended to symbolically mark the pharaoh’s eternal path in the afterlife [

21]. Notable examples may also be found in the polychrome tiles of the Sumerian city of Uruk, specifically in the Eanna Complex, dating from 3600 to 3200 BCE. In this location, numerous polychrome conical tiles were utilised to clad the immense adobe and rammed-earth pillars and walls [

22]. These tiles, painted in red, white, or black, were arranged to form geometric patterns with the purpose of protecting the temple from deterioration and environmental factors while also serving as decorative elements [

23].

In accordance with the exceptional collections of the Alhambra, the classification of “painted” tiles is based on their primary generic concept, thus allowing for the inclusion of diverse forms, typologies, and designs across all relevant chronological periods (see

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Among the examined examples of the Alhambra Museum, several monochrome objects stand out, predominantly painted in green, white, or blue. These include, for example, several eight-pointed-star-shaped tiles ranging from R072164 to R072191 (

Figure 3a) painted in green, and registers from R072193 (

Figure 3b) to R072223 painted in blue. Of particular note are the tile R002786 (

Figure 3c), the

alizares R107125 (

Figure 3d) and R116376 to R116404 from the Queen’s Robing Room, also the fragments of a Nasrid-era rooflight, A085786/25 (

Figure 3e) and A085786/38 (

Figure 3f), which originate from the bathhouse of the Convent of San Francisco.

With regard to polychrome-painted decoration, a particularly noteworthy example is the Nasrid-period tile fragment R001285 (

Figure 4a) from the ground floor of the Queen’s Robing Room. This artefact is finely painted in green, blue, golden lustre (of which only vestiges remain), and purple on a white background, depicting the Nasrid royal emblem framed by geometric and vegetal motifs. Notably, the use of purple in this piece could be significant, as it may refer to tiles possibly produced by

Mudéjar artisans during the transition periods following the Granada Conquest in late 15th and early 16th centuries [

24].

Numerous polychrome objects featuring strictly vegetal compositions are also preserved within the museum’s collections. Examples include records ranging from R112677 to R112683, R112685 to R112691, R112695 (

Figure 4b) to R112703, and R112705 to R112715 (

Figure 4c), classified under the “oval pearl” series, which were painted in blue with yellow details on a white background; the tiles from R138679 (

Figure 4d) to R138720, that were painted in blue with additional details in bright yellow, ochre, and green; and the tiles R136222 and R136223, as well as the records ranging from R136215 to R136219 (

Figure 4e), belonging to the “diamond point with coiled petal flower” series, which were painted in blue with bright yellow, ochre, green, and, occasionally, black line details.

In addition, several pieces featuring human figures and Christian motifs are catalogued, including inventory R136773 (

Figure 5a) and records numbering from R136731 (

Figure 5b) to R136849, which bear close parallels to a Valencian-produced tile (reference number 72 of Onda Tile Museum). Of further interest are tiles depicting architectural elements, like temples, as in the cases of R123118 and R123116 (

Figure 5c), representations of castles and fortifications, as in the case of R123267 (

Figure 5d), and inventories from R135804 (

Figure 5e) to R135820, which were painted in blue and yellow on a white background.

It is also important to mention other elements, such as some types of architectural signs and funerary steles. Examples include the inventory numbers from R120517 to R120549, R120573 (

Figure 5f) to R120586, and numbers R120599 (

Figure 5g) to R120603, which feature epigraphic motifs inscribed in blue on a white background.

Finally, it is noteworthy that the tiles classified under the “oval pearl” and “diamond point” series, as well as the aforementioned tiles featuring human figures, are catalogued under the “Talavera style” classification within the Alhambra Museum collection. This has given rise to a discourse surrounding the possible origins of these series, evoking divergent opinions between the two pioneering centres of tin-glazed ceramic pieces in the Iberian Peninsula: Seville and Talavera. However, the undeniable hallmark of these pieces is their modern chronology, whereby the term “painted” served to unify both productions, emerging in response to the demand for ceramics that catered to the refined tastes of a clientele extending beyond the everyday use of ceramic wares [

25].

3.2. Relief Tiles

Relief is defined as a sculptural technique (although it can be made using moulds) that consists of a volumetric and three-dimensional representation of a compositional pattern on a ceramic support. The three main types of relief are high, medium, or bas-relief, the concepts of which are assigned according to the depth obtained between the planes of the composition.

Throughout antiquity, various cultures employed architectural ceramics crafted using the relief technique, primarily for educational and propagandistic purposes [

26]. In Egypt, particularly within the palaces of Ramses III (1184–1153 BCE), notable examples have been discovered featuring human and animal elements. Some examples include depictions of war prisoners captured in battle and a rekhyt bird representation, such as those recovered from the palace at Tell el-Yahudiya (British Museum reference numbers 1871,0619.347 and 1874,0314.131, respectively). Similarly, in Mesopotamia, widely regarded as a major centre for the production and use of glazed tiles and bricks, relief ceramics were extensively applied in architectural contexts. The most emblematic example is the monumental Ishtar Gate, constructed during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BCE). This structure was entirely adorned with cobalt-blue-glazed and relief bricks rendered in shades of yellow, orange, and white, depicting animal iconography [

22]. This gate also represents the earliest documented instance of large-scale ceramic production, incorporating distinct manufacturing stages for modelling, glazing, and a double-firing process [

23].

Another significant case is the Eastern Gate of the Achaemenid Palace at Susa, built under the rule of Darius I (521–486 BCE). This gateway featured the renowned Frieze of the Immortal Guards, a finely executed composition created using large-format bricks modelled in relief and vividly glazed to enhance visual impact. China, meanwhile, developed a parallel and independent tradition of architectural ceramics that flourished as early as the Eastern Zhou (8th–3rd BCE) and Han dynasties (3rd BCE–3rd CE). The Chinese traditional ceramic tiles emerged as an effective medium for the embellishment of roofs and walls of sacred structures, such as tomb complexes and Buddhist pagodas. During the Tang (7th–10th CE) and Song (10th–13th CE) dynasties, roof decorations using polychrome glazed tiles, often with figural or symbolic motifs, achieved new heights of technical and artistic refinement. Particularly notable are the sancai-glazed roof tiles and the glazed ceramic ornamentation of the Yongning Pagoda in Luoyang or the relief-decorated tiles of the tombs of the Wu family in the Shandong province from the Han dynasty, as well as in burial sites from the Song dynasty [

5,

6,

7]. Also of particular note are the Red Pagoda in Henan province, which was constructed in the 5th century CE and still preserves its ornamented relief bricks and tiles, and the

goutou relief roof tiles from the Ming dynasty (14th–17th CE) [

27].

In the Alhambra, relief tiles are among the least frequently encountered. However, a considerable number of objects have been preserved both in situ and within the museum storage collection [

18]. Most of these objects were specifically crafted to fit prominent locations of the Palatine City, such as the soffits of arches and the plinths of façades, as exemplified by the decorative elements of the Gate of Justice (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

The Gate of Justice, also known as the Gate of the Esplanade or the Gate of the Law, retains part of its original decorative scheme on its inner façade, consisting of ceramic rhomboidal motifs (

sebka) adorned with relief tiles featuring vegetal designs. The chromatic palette is primarily composed of cool tones, including shades of blue, green, and white. Notable examples include the tiles R132765 (

Figure 6a) and R132766 (

Figure 6b), which exhibit vegetal motifs combined with Arabic Kufic inscriptions glazed in blue and green. Furthermore, some of these pieces present perforations made prior to firing, as evidenced by tiles from numbers R139767 (

Figure 6c) to R139776 and R001278 (

Figure 6d). These perforations provided an additional point of attachment, in this case facilitated by the use of nails.

In general, the Alhambra relief tiles are stylistically similar to some of the interior decorative elements of the city, such as stucco work and muqarnas [

28]. However, the tiles have the advantage of greater durability in exterior environments and resistance to climatic conditions [

29]. Among the examined examples housed in the Alhambra collection, several pieces exhibit these decorative characteristics. Notable tiles include R003817, R078161, R086614, R000385 (

Figure 6e), R000387 to R000390, R000392, R000397, and R000398 (

Figure 6f), which are predominantly decorated in green.

Also noteworthy are the tiles catalogued from R132759 (

Figure 7a) to R132764, belonging to the “sebka of the Royal Gate” series, characterised by ataurique (vegetal) motifs decorated in white, including details in varying shades of blue and green. Furthermore, Arabic epigraphic tiles can be represented by the inventoried pieces ranging from R003831 to R003836 and R132511 (

Figure 7b) to R132521, as well as numbers R064222, R139624, R066165, R069437, R132770 (

Figure 7c), R139625, R129696, R119809, R118926, R118922, R078825, R077737, and R074026 (

Figure 7d). Finally, tiles with white enamel and gilded decoration are represented by the inventoried pieces R006687-1 to R006687-4, R001286, and R001288 (

Figure 7e), which possibly belong to the same frieze in the Machuca Gallery at Alhambra.

3.3. Lustre Tiles

Despite the origins of the lustre technique in Egypt, where copper and silver lustre were used to decorate glassware, it was in the 9th and 10th centuries that metallic lustre was introduced and subsequently applied to ceramics by Islamic potters in Baghdad and Basra, Iraq [

30]. These centuries were remarkable for their wealth of secular art, particularly in Islamic (both Christian and Muslim) architecture. During this period, buildings were often conceived as representations of the faith, and the idea of reinforcing the spiritual and symbolic function of these structures through architectural ornamentation was introduced. The tradition of wall ornamentation underwent a gradual evolution, although it was under the influence of Muslim models that a flourishing “Golden Age” emerged. The new artistic approach was marked by the use of golden backgrounds, initially in stone and stucco paintings and subsequently in tiles, to accentuate significant and sacred spaces [

31].

Documentary evidence suggests that this innovative ceramic decoration technique was first produced during the first one hundred and fifty years of Abbasid hegemony, although the issue of whether the Fatimids were the first in Egypt to utilise this Persian–Iraqian decorative technique has been a subject of debate [

32]. The earliest use of golden lustre tiles, which also refer to the initial Abbasid dynasty production, are represented by examples from Baghdad and Samarra, Iraq. The first conscious effort to outshine a building is represented by the Qayrawan Great Mosque in Tunisia, particularly the domed area in front of the mihrab and the qibla wall, where magnificent lustre tiles were used as the main ornamentation technique. It is notable that Abu Ibrahim Ahmad, an Aghlabid amir who ruled Qayrawan from 856 and 863 under the aegis of the Abbasids, had these ceramic tiles imported from Baghdad [

33]. Regarding Samarra, notable examples have been observed in some 9th-century-dated polychrome lustre square tiles originating from archaeological excavations carried out by Professor Ernst Herzfeld in Dar al-Khilafa [

34]. These tiles bear a central motif (often animal representations) in a wreath-like vegetal roundel and palmettes in the corners, such as the specimens found in British Museum under reference number OA+.10624.

During the initial phases of this technique’s evolution, the proficiency and dexterity necessary to produce lustre ware were exclusive to specific ceramic artisan families. This assertion is evidenced by the writings of Abu’l Qasim, a member of a traditional lineage of potters from Kashan in Iran, who provided the major technical source detailing the materials and execution of the lustre technique [

35]. Qasim referred to lustre technique as the “two-firing glaze”, indicating that the metallic mixture was applied to a previously fired ceramic surface, subjecting it to an ultimate firing in order to achieve their metallic sheen. He also described the removal of residual deposits that adhered to the pieces after a prolonged, smoke-rich firing process lasting seventy-two hours by stating “Rub them with damp earth so that the colour of gold emerges”, confirming that the second firing was carried out in low-temperature conditions and in a reducing atmosphere [

35] (§27). Additionally, his manuscript provides a detailed description of the colour variants of metallic lustre [

35] (§14 to §24).

Regardless, the prevailing hypothesis is that the technique of producing lustre ceramics pieces, especially tiles, spread from the production site at Al Qal’a of Beni Hammad in present-day Algeria and the subsequent Hammadid capital, Bougie, to Al-Andalus [

36]. The dating of this earlier Andalusian lusterware is provided by some examples of a group employed as

bacini (sing.

bacino) in the façades of Romanesque churches and/or campaniles in Italy, the dates of which range from the 11th until the third quarter of the 12th century [

37]. The collection, which contains over sixty bowls decorated with this technique and often accentuated with incised details, has been ascribed to Malaga [

38], noting that during this period of approximately one hundred years, the region was under the domination of the Zirids, ruling from Granada, and later of the Almoravids, until the arrival of the Almohads, and finally of the Nasrids [

39].

The significance of gold within the Alhambra is clearly evidenced by the collection of lustre tiles preserved in its museum holdings, showcasing a wide array of pieces executed using this technique. The decorative motifs vary from geometric, vegetal, and heraldic to epigraphic. While the majority are adorned in blue, white, and gold, some examples exhibit a simpler palette of white and gold (see

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

Among the inventoried objects, vegetal motifs are the most prevalent, often serving as framing elements for epigraphic or heraldic designs. Representative pieces include inventory numbers R003031, R107101 to R107107, R122933 (

Figure 8a) to R122946, R091319 to R091324, R051179, R051236, R051240, R051255, R051362, R051309, R051310, R051314 (

Figure 8b), R051316, R051325 (

Figure 8c), R051327, R051372, and R051430 (

Figure 8d), all decorated in blue and golden lustre over a white background.

The geometric designs include notable objects such as R003030 (

Figure 8e), which features a blue pattern with gold detailing over a white background and has been dated to the construction of the Palace of Alijares in 1375 [

40]. Also significant are the tiles R001303 (

Figure 8f), R001304 (

Figure 8g), and R066144 (

Figure 8h), which exhibit finely executed interlacing white ribbons set against a golden background.

The collection also includes significant epigraphic distinct pieces, such as the Nasrid funerary border R001319 (

Figure 9a), which displays a cursive Arabic inscription in blue with gold detailing over a white background, covering both the obverse and reverse surfaces of the piece.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the Alhambra Museum has preserved a significant number of artefacts categorised as “pottery tailings”. This finding leads to the hypothesis that a tile production centre may have existed in Granada, or even within the Alhambra itself. Of particular note are several Nasrid lustre tiles within this classification, including registration numbers R051434 (

Figure 9b), R051481 (

Figure 9c), and R051315/1 (

Figure 9d). These artefacts exhibit various manufacturing flaws, including over-firing of the glaze, the presence of a kiln support (

atifle) imprint created during the firing process, and a glaze stain resulting from pigment transfer during the firing process, respectively.

3.4. Alicatado

It is important to note that two remarkable applications of tiling compositions can be found in ancient architecture. The first of these relates to the use of individual ceramic tiles in the creation of tilework panels, whilst the second specifically relates to the tiling mosaic (

alicatado) technique. The

alicatado technique is distinguished by the creation of polychrome panels composed of small flat pieces (

aliceres), which are carefully cut into different geometric profiles and individually glazed in various colours to create highly intricate and aesthetically refined compositions (see

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). A further common feature of the

aliceres is that they are frequently bevelled on the back to facilitate the effective assembly of each individual piece into the tiling mosaic panel.

Examples of the first mentioned category can be better observed in epigraphic specimens executed using

incrustación and

cuerda seca techniques, which are further explained alongside this document. Concerning the

alicatado technique, the earliest documented pieces were identified on star-and-cross-shaped lustre specimens from Al Qal’a of Beni Hammad in Algeria (e.g., fragment of tiling mosaic panel number II.C.185 in the National Museum of Antiquities and Islamic Arts), on Qilich Arslan II Palace tiles at Konya in Turkey (e.g., tile number 1976.245 in the MET Museum), and lastly on the Ku-badabad Palace tiles (non-referenced pieces in the Konya Karatay Madrasa Museum virtual catalogue) dated in the early 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries, respectively [

8].

In Spain, the tiling mosaic technique is firstly documented on the qibla and the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, decorated under the supervision of Byzantine artisans from Constantinople between 965 and 971 CE [

41]. Later, tiling mosaic pieces from the early 13th century were identified in the spandrels of blind arches that adorn the second-tier wall surfaces of the Torre del Oro in Seville. The original cladding of the tower consisted of a tile mosaic comprising alternating white and green rhomboidal shapes. Despite being the result of modern restoration, these tiles appear to replicate the characteristics of the original specimens unearthed on site [

42]. In Granada, also in the early 13th century, the earliest documented examples are found in the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo. These tiles feature an interlacing star polygon composition, primarily executed in white, green, turquoise, black, and, on rare occasions, yellow [

42].

In the context of the Alhambra Palatine City, the earliest examples of tiling mosaic panels are observed in the Torre de las Damas in the Partal Palace, comprising black and green bands on a white background. These are analogous to those found in the Generalife and predate their more richly polychrome counterparts in the Comares Palace, all from the 13th century [

42]. Furthermore, the

alicatado artwork of the Tower of the Captive features a glazed decoration in white, black, green, blue, yellow, and a distinctive purple hue derived from manganese oxide, a colour found nowhere else in the Palatine City. Significant examples from the second half of the 14th century include the arches’ threshold of the Hall of the Two Sisters and the Mirador de Daraxa in the Palace of the Lions, both of which feature exquisite

alicatado work. These represent the pinnacle of technical perfection within the tiling mosaic technique, due to their execution using diminutive pre-cut and glazed

aliceres [

42].

The Alhambra Museum houses a considerable collection of single tiling mosaic pieces (

aliceres) and fragmented compositional panels [

18]. The

aliceres are generally grouped into series according to their geometric shape. The majority of the stored specimens are glazed in white and black, although numerous examples also appear in dark green, turquoise, ochre, and dark blue.

Notable examples of

aliceres include the following: the record numbers ranging from R141760 to R141776 (

Figure 10a), R141777 to R141782 (

Figure 10b), and R141783 to R141954 from the “candilejo and five-pointed star” series that are glazed in white; the white pieces ranging from R110998 (

Figure 10c) to R111057 from the “trisquel” series, as well as their parallel in black, inventoried from number R110796 (

Figure 10d) to R110847, and the dark-green (occasionally turquoise) variants ranging from R109562 (

Figure 10e) to R109603; the pieces from R122762 (

Figure 10f) to R122764 (

Figure 10g) of the “zafate and rhomboidal” series and the pieces from R128510 (

Figure 10h) to R128695 of the “cross” series, both of which are glazed in black; the “merlon” series ranging from R138969 (

Figure 10i) to R139093 and the “stepped merlon” series from R137243 to R137264 and R137269 to R137751 (

Figure 10j), with black and white specimens; the range of R093124 to R093145 (

Figure 10k), R093146 to R093169, and R093182 to R095519 of the “arrowhead” series, which includes several specimens glazed in dark blue; and, finally, the inventoried pieces ranging from R113944 to R113961 (

Figure 10l) and R113962 to R114025 belonging to the “ribbon” series, which include pieces decorated in ochre.

In addition, there are several significant fragmented compositional panels within the Alhambra Museum collection that require attention. The inventory numbers R091288 (

Figure 11a) and R091290 (

Figure 11b), for instance, alternate white square tiles with black rectangular tiles. It is noteworthy that both fragments were once part of the wall cladding of the Convent of San Francisco. Of particular note is the inventory number R002264 (

Figure 11c). This fragment of tiling mosaic panel comprises twenty

aliceres glazed in ochre, black, and green, interspersed with other arrowhead-shaped

aliceres in white, which are arranged around a central eight-pointed star

alicer (sing. form). It is also noteworthy that the provenance of this fragment is the Hall of the Kings in the Palace of the Lions, whose original

alicatado decorations were replaced by painted stucco imitations during 19th-century ornamental restoration works [

43,

44].

Another significant example is the register R001382 (

Figure 11d). This fragment comprises sixteen

aliceres glazed in ochre, black, and white. Of particular interest is the fact that the octagonal compositional pattern is still visible in situ in the central western alicatado plinth of the Hall of the Ambassadors and the Room of the Ship of the Comares Palace. A further noteworthy fragment is R001418 (

Figure 11e), which is of particular significance. It consists of ten

aliceres, including two square pieces decorated in black, four triangular pieces decorated in white, and four rectangular pieces decorated in turquoise. A notable similarity is observed between this fragment and the plinth observed in situ on the lower floor of the Queen’s Robing Room [

45]. The final fragment under consideration among the tiling fragmented panels is the register R124965 (

Figure 11f), which comprises twenty rectangular

aliceres glazed in blue, turquoise, and black, interspersed with white tiles. However, due to modern restoration, the precise location of these

aliceres in the Palatine City remains unknown.

Finally, it is essential to emphasise two points with particular attention. Firstly, it is noteworthy that a significant proportion of the tiling mosaic pieces examined for this study exhibit a dual decorative layer. This is distinguished by the presence of a white base layer (probably engobe) under the final superficial coloured glaze. This dual-layer production technique is particularly evident in Nasrid examples, whose superficial wear reveals the lower layer, and is especially pronounced in

aliceres decorated in black, creating a strong contrast with the white ground (see

Figure 12).

Secondly, a considerable number of specimens have been classified as “pottery tailings”, which further reinforces the hypothesis of a Granada or even an Alhambra-based production of architectural ceramics. Notable examples include the

aliceres R100416 (

Figure 13a), R122752, R122753, R122759, R122800, R122818, R141760 (

Figure 13b), R124876, and R124880, which exhibit unfinished carving, and the

aliceres R122784, R122815, R122835, R122836, R124890 (

Figure 13c), R137216, R137218, and R137220, which display evident signs of glaze overfiring. In addition, the

aliceres R124879 (

Figure 13d) and R112151 exhibit remnants of other pieces fused to the glaze surface. Finally, the

aliceres R111324 (

Figure 13e), R112158, R112177, R112178, R112183, R112192, R112193, and R112200 exhibit superficial glaze stains, possibly transferred from adjacent tiles during firing.

3.5. Incrustación Tiles

The inlay technique has been employed in ceramic artefacts since prehistoric times. The inlaid decoration, achieved by inserting coloured paste into a previously carved recess, was traditionally used as a complementary technique to incise decoration. Exquisite examples of this practice can be observed in the

cerámica campaniforme from the Iberian Peninsula, particularly within the style known as the “Ciempozuelos Style”. This style is exemplified by artefacts unearthed during archaeological excavations conducted in 1895 [

46]. Several specimens from Ciempozuelos are currently housed in the Spanish National Archaeological Museum, with notable examples including inventory numbers 32252, 32253, 32254, and 32255. Another remarkable example of inlaid decoration can be found in the perfume vessel of Amenhotep III (inventory number E4877 of the Louvre Museum), which is coated with an exclusive yellow glaze and adorned with finely inlaid blue hieroglyphs, executed using Egyptian paste or faience [

47].

Notwithstanding, a variant of this technique, referred to as

incrustación, can be observed in the Alhambra, where monochrome ceramic pieces of different hues were inserted into a previously carved and glazed tile, instead of using coloured paste, to achieve a polychrome composition (see

Figure 14). In this context, these objects were specifically utilised as wall cladding, forming epigraphic friezes or highlighting particular compositional panels within the Palatine City.

In comparison with the

alicatado technique, in which pieces are individually cut according to precise geometric designs, the

incrustación technique allows for greater design flexibility through the process of carving. This factor was highly significant within the Nasrid era of the Alhambra for the execution of calligraphic motifs with pronounced contours, as illustrated by fragment R001294 (

Figure 14a). This particular tile was produced using a monochrome, blue-glazed base, into which white ceramic pieces were inlaid, serving as the background of the composition and revealing a fluid cursive inscription. The provenance and chronology of this piece correspond with the frieze along the upper part of the plinth in the main hall of the Tower of the Captive of the Alhambra, where in situ examples date to the 14th century [

48].

From a chromatic point of view,

incrustación tiles tend to have a more limited palette of two or three cool tones compared to

alicatado tiles. Representative examples are the tiles from the Infantes Palace, later converted into the Convent of San Francisco [

49], which are considered to be the earliest examples currently registered in the Alhambra Museum. Thus, most of the objects in the collection come from the hammam (bathhouse) of this Nasrid palace. Its construction dates from the reign of Sultan Muhammad II (1273–1302), with later interventions, apparently from the time of Yusuf I, and a major refurbishment carried out after 1370 during the reign of Muhammad V [

50]. A stylistic parallel to these tiles can also be observed in situ at the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo in Granada. Notable examples inside Alhambra collections include R113685, R113687, R014297, R014297/1 to R014297/4, R001271, R001272 (

Figure 14b), and the tiles catalogued from R121585 to R121609 (excluding R121597), which have epigraphic motifs in black on a white background. Noteworthy artefacts originating from the hammam of San Francisco are also represented by A085786/19 (

Figure 14c) and A085786/20 (

Figure 14d), which were recovered during the most recent stratigraphic excavation campaign [

51]. The first piece is an

incrustación fragment featuring green decoration, seemingly with a geometric motif, while the second corresponds to the epigraphic typology, again displaying black inscription against a white background.

Further significant examples within the Alhambra Museum collection include tiles such as the green decorated R121708 (

Figure 14e), with stylistic parallels found in situ at the Gate of the Arms; the fragment R000384 (

Figure 14f), whose compositional motif of a forearm holding a key suggests a connection with the Palace of Abencerrajes; and finally, the fragment R121626 (

Figure 14g), which has been associated with the

Mudéjar panels preserved in situ in the Oratory of Mexuar [

48].

3.6. Cuerda Seca Tiles

Cuerda seca is a decorative technique characterised by the alternation of black contour lines with painted areas and, on occasion, sections that highlight the natural colour of the ceramic surfaces. The primary objective of this technique is to achieve a visual effect similar to that of the

alicatado technique, founded upon polychrome compositions. However, in this case, the separation of colours within the composition involves the application of manganese oxide mixed with animal fat or vegetable oil, thereby preventing the blending or overlapping of colours during the firing process. This concept of a ceramic surface decorated with compositions delineated in black and then filled in with other colours can be traced back to the ceramic tradition known as Verde-Manganeso ware style, which originated in Al-Andalus, where it was extensively utilised during the Taifa Kingdoms (1031–1086 CE) and persisted throughout the Almoravid (1086–1148 CE) and Almohad (1148–1232 CE) eras [

52].

The earliest known utilisation of this Andalusian technique in an architectural context is evidenced by a

cuerda seca tile panel fragment dating from the early 12th century. The fragment in question comprises two large red earthenware tiles with an opaque greenish-white glaze and a prominent Kufic inscription of Al-Fatiha in a dark purple glaze. Originally designed to be bolted to the wall, they may have decorated the striking frieze of the minaret of the Qasba mosque in Marrakech [

8,

32]. Despite the fact that a significant portion of the original frieze has been lost, this important archaeological discovery, which are currently displayed in the Badi Palace Museum (no reference number), provides crucial information on the production of

cuerda seca tiles.

However, the majority of

cuerda seca tilework is associated with the Timurid architectural decoration style, distinguished by extensive surfaces adorned with decorated bricks and tile panels made of intricate multicoloured friezes executed in the

cuerda seca technique [

53]. Timurid tiles are characterised by a rich and varied palette of colours, especially dark blue, turquoise, white, purple, and occasionally gold, with inscriptions and vegetal motifs predominating. Examples dated from the 14th century onwards include panels from Aq Saray Palace in Uzbekistan, those in Madrasa al-Ghiyathiyya and Hasht Bihisht in Iran, the panels from Çinili Köşk, the Yeşil Cami and Üç Şerefeli Mosques in Türkiye, and finally those of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. These artworks in question were signed by the “Masters of Tabriz”, a group of a tile-makers and tile-cutters specialised in tiled decoration [

31]. It is especially noteworthy that the expansion of this technique has been enabled by the exchange/importation of expertise labour and tiles [

54].

It is imperative to acknowledge that

cuerda seca tiles are categorised into two primary types: partial

cuerda seca and total

cuerda seca. The distinction between these categories directly corresponds to the proportion of the tile’s surface that is covered by glaze, whether partially or totally. Beyond this classification, further distinctions must be remarked, albeit in this case, not relating to the percentage of glazed surface but rather to the method used to reinforce the separation between the colours [

20]. This refined classification allows for the identification of various subtypes, such as the flat

cuerda seca, which is executed on a smooth surface; the incised

cuerda seca, where the design is impressed in negative using a mould; the recessed

cuerda seca, created by carving deeper grooves into the surface; and finally, the reinforced

cuerda seca (single or double), which is produced by pressing a mould in relief, forming one or two barriers on the ceramic surface (see

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

The total cuerda seca typology is the most prevalent within the Alhambra Museum collection, comprising numerous pieces and fragments of diverse provenance and chronology. These objects are also classified according to their specific subtype: flat, incised, recessed, or reinforced (either single or double). In addition, most of the cuerda seca tiles may be further grouped into series based on their compositional motifs, as much of them incorporate a particular design or style.

Within the classification of flat

cuerda seca, tiles from the Nasrid period, specifically R003816 (

Figure 15a), R001269, R001280, R092880, R092879, R092875 to R092877, R092869, R051165, R051163, and R051158 (

Figure 15b), are of particular note inside the Alhambra Museum collection. These pieces exhibit vegetal decoration in black delineated by manganese cordons on a white background and may belong to the same compositional panel inside the Palatine City. Further examples can also be found in the inventory records R001279, R092883 (

Figure 15c), R092890, R092891, R092886 (

Figure 15d), and R092887 (

Figure 15e), featuring ataurique motifs in green, blue, turquoise, and black, outlined by manganese cordons on a white background, which bear a striking resemblance to the tiles adorning the Gate of Wine in the Alhambra. The inventory records R092870 (

Figure 15f) to R092874 (

Figure 15g) also merit mention, as distinguished by their slightly curved rectangular format, specifically designed to clad water fountains within the Palatine City.

The Alhambra collection also includes several examples of post-mediaeval flat

cuerda seca tiles, which can be represented by the inventory numbers ranging from R091143 (

Figure 16a) to R091233. These pieces belong to the “flat geometric” series and present an unusual rectangular format designed to be displayed in vertical orientation. The composition specifically consists of glazed ribbons in various shades of blue, green, yellow, and black, outlined by characteristic manganese cordons, forming a crisscrossed octagonal pattern framed by a thick ribbon on the upper edge glazed in turquoise. Furthermore, the

alizares R112788 (

Figure 16b) and R113252 (

Figure 16c) belong to the “chain of arches” series, which were executed in a L-shaped format. This shape displays two decorated surfaces, located at the front and top, which were specifically designed to cover the edges of steps, sills, and other architectural elements.

In the context of the incised

cuerda seca classification, certain tiles merit consideration. The first example to cite is the tile R001284 (

Figure 16d) decorated in black and white, which probably dates from late 13th to the early 14th centuries, due to its original provenance at the hammam of the Convent of San Francisco in the Alhambra. Additionally, the record number R136578 (

Figure 16e) from the “cubical” series, decorated in white, black, ochre, and green, is notable for its in situ parallels identified in the Comares Palace, suggesting origins from the late 15th to the early 16th centuries. Furthermore, the composition of four tiles registered with the number R002037 (see

Figure 16f) from the “polygonal” series, also suggests an attribution to the 15th–16th centuries, as some parallels were identified in the courtyard of the Palace of the Lions [

55].

With regard to the recessed

cuerda seca typology, illustrative examples include the objects R136611, R136620 (

Figure 16g), and R140277 from the “zigzag” series, which likely originated from the Partal in the Alhambra. Furthermore, the pieces R132821 (

Figure 16h) and R132822 from the “recessed interlacing” series, which were recovered from the Garden of the Convent of San Francisco in the Alhambra, are also worthy of mention.

Finally, within the reinforced typology of the Alhambra Museum collections, single-reinforced

cuerda seca tiles such as R114429 (

Figure 16i) and R080373, belonging to the “stepped merlon and spur frieze” and “interlaced and scalloped zafates” series, respectively, are noteworthy, as both have in situ parallels in the Comares Palace. In addition, the double-reinforced

cuerda seca tiles R091107 (

Figure 16j), R000246, and R000255 are of particular importance due to their provenance from the Plaza de los Aljibes in the Alhambra [

55].

3.7. Arista Tiles

The

arista technique bears a strong resemblance to the

cuerda seca, as it has emerged as a visually analogous alternative to the

alicatado technique, which permitted the execution of intricate and polychrome compositional designs. Commonly described as “pseudo-mosaic” or “cuenca” in general literature [

23], the

arista is considered a variant within the impressed ceramic techniques, known as “stamping” in technical ceramic production terminology. The method involves the imprinting of the decorative pattern onto the raw surface of an object using a stamp, or occasionally a mould, which has been previously carved, in order to produce a raised relief on the clay surface. This relief-type design functions as a barrier during the firing process, effectively separating the colours of the composition by preventing the overlapping or blending of different decorative glazes (see

Figure 17).

The British Museum has two important pieces from the Alhambra (inventory numbers 1802, 0508.1.a and 1802, 0508.1.b) that are excellent examples of the

arista technique. The tiles, which were designated “azulejo del escudo de la banda”, are crafted using the

arista technique and are embellished with cobalt blue and golden lustre against a white background [

56]. The Nasrid coat of arms is prominently featured, accompanied by Arabic cursive inscriptions. Both specimens can be compared with numerous examples currently held in the Alhambra Museum, some of which bear records numbers ranging from R069017 to R069033, R069035 to R069042, R069050 to R069095, R069449 to R069478, R069880 to R069920, R070571 to R070584 (

Figure 17a), R070586 to R070608, and R070671 (

Figure 17b) to R070774. Furthermore, they correspond to in situ tiles found in the pavement of the Hall of the Comares Palace, which are dated between the late 15th and early 16th centuries [

56].

The production of

arista tiles underwent a period of significant growth and development in

Mudéjar pottery workshops following the conquest of Granada in the late 15th century, becoming increasingly prevalent from the first half of the 16th century onwards. This expansion can be attributed to the adoption of serial manufacturing techniques and the incorporation of design elements related to Renaissance and Gothic influences, resulting in a product with export potential from production centres such as Seville and Toledo [

25]. However, evidence of local production of

arista tiles has been found in archaeological excavations at the Alhambra [

57,

58]. The hypothesis of a local production centre could be supported by the existence of several pieces classified as “pottery tailings” in the Alhambra Museum. The collection includes numerous specimens that are unfinished or defective, particularly those awaiting the application of glazes or exhibiting manufacturing and firing defects such as glaze drips and

atifle imprint marks. Examples include inventory numbers R128249, R128251, R128254 (

Figure 17c), R128256 (

Figure 17d), R128257, R138721 to R138724, R130379, R139951 (

Figure 17e) to R140011, and R140373 to R140381.

Finally, notable examples of arista tiles include some pieces from the Baths of Comares Palace, such as the tiles ranging from R136394 (

Figure 17f) to R136536. These tiles bear the inscription “P.V.”, which has been interpreted as either the initials of “Philip V” or an abbreviation of “Plus Ultra” that symbolises the Christian expansion and power achieved by the Spanish Crown. It is noteworthy that during the 19th and 20th centuries, this type of decoration was discredited by critics in Spain, who disparagingly referred to it as “poor-quality tiles of the so-called Renaissance style” [

59]. Furthermore, the tiles R080561 (

Figure 17g) and R120557 (

Figure 17h) merit particular attention due to the presence of an inscribed date as part of their decorative composition, confirming a production date in the 16th century.

3.8. Final Reflections

3.8.1. Ancient Foundations and Early Transmissions

The utilisation of ceramics in architectural contexts emerged as a pivotal medium for visual and symbolic expression. As outlined in

Table 1, painted and relief ceramic tiles were utilised as early as the 4th millennium BCE in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Of particular note among these early precedents is the association of ceramic cladding with spiritual and ceremonial architecture, as well as the expertise in the manufacture of these objects, which prefigure the technical and artistic strategies later adopted by Islamic artisans. In addition to their evident decorative function, these artefacts are noteworthy in demonstrating that the multifaceted nature of architectural ceramic objects was firmly established in pre-Islamic architectural traditions, including their protective, educational, and propagandistic roles. This provides a rich conceptual foundation for subsequent Islamic reinterpretations and elaborations. Beyond the Near East, Persia played a foundational role in the development of architectural ceramics. From the Achaemenid period (c. 550–330 BCE) onwards, Persian palatial architecture employed the use of relief tiles and bricks for the purpose of adorning monumental façades. The works in question reflected a highly sophisticated level of craftsmanship, wherein architectural ceramic objects were used not only for decoration but also as vehicles of imperial identity and political legitimacy. Meanwhile, in China, ceramic tiles became a defining element in both sacred and secular architecture from the Zhou dynasty onwards. The Han dynasty expanded this use with high-fired roof tiles and wall bricks, often in relief, a tradition that was further enriched during the Tang, Song, and subsequently the Ming dynasties through the development of

sancai glazes and the application of painted porcelain tiles in tombs and pagodas. The technological sophistication of Chinese craftsmanship would later influence Islamic ceramicists via the Silk Road and through the transmission of technologies and stylistic principles [

60].

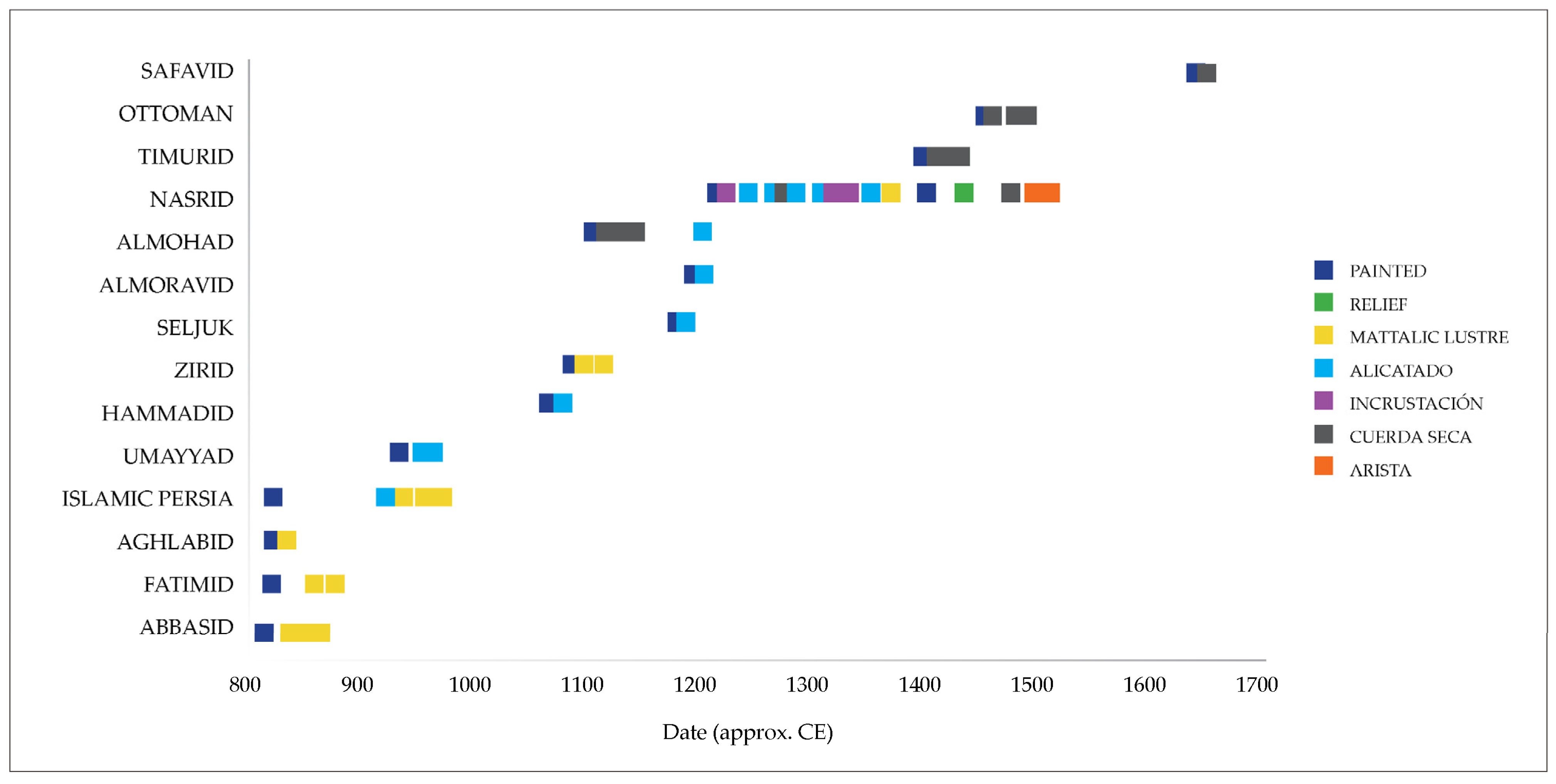

3.8.2. Islamic Transformations and Technological Dissemination

The evolution of Islamic architectural decoration was significantly impacted by the Arab expansion. From its formative centuries, the Islamic world inherited and expanded upon earlier ceramic traditions through technological innovation and the flourishing of transregional exchanges. During the Islamic period, various techniques were developed, including metallic lustre,

alicatado works, and

cuerda seca tile panels, each of which reflects technological advancements, artistic influences, and cultural exchanges (

Figure 18).

During the Abbasid period, significant centres such as Samarra, Baghdad, and Kashan experienced a period of notable prosperity, with the production of metallic lustre tiles becoming a prominent industry. As highlighted throughout this document, this technique is regarded as one of the most significant artistic and technological achievements in Islamic workshops, particularly in architectural applications such as golden lustre tiles. Within Andalusian production, the metallic lustre is documented from the 11th century onwards in Malaga, under the domination of the Zirids, ruling from Granada. Specifically in Granada, the Nasrid dynasty improved on the traditional gold lustre, which was mainly applied to a white tin-glazed base and often enhanced with cobalt blue decoration [

61,

62]. This aesthetic improvement ultimately led to the creation of the so-called Alhambra vases and exerted a significant influence on the subsequent production of lustre tiles in Spain [

42]. The application of copper and silver chloride in a third firing was described as “a process developed, and possibly invented, to produce, in a simpler and more cost-effective manner, metallic sheen rather than gold lustre” in Triana, Seville [

63]. Besides the high value of metallic lustre across Islamic world, a significant aspect of this tilework is the intrinsic association with divine illumination, a feature that is reflected in the use of the tiles in sacred and religious places.

The

alicatado is regarded as one of the most technically and visually compelling forms of ceramic decoration employed in Islamic architecture. This technique underwent a period of rapid evolution, spreading almost concurrently from the Umayyad dynasty in Córdoba to the Hammadid, Seljuk, Almohad, and Nasrid dynasties. In Al-Andalus, this evolution underwent a process of cultural fusion with local Roman and Visigoth building traditions, resulting in the creation of uniquely Andalusian forms [

64]. The significance of this decorative technique lies not only in its decorative complexity but also in its broader artistic and symbolic value. The absence of figural imagery in Islamic art over the centuries and the emphasis on geometric abstraction have led to the establishment of the principles of geometric representation, which reflect a metaphysical sense of order and infinity.

Concurrently, the

cuerda seca technique, initially developed in Andalusian

Verde-Manganeso wares of the Taifa period, became prevalent in Almoravid and Almohad decoration, reaching new heights in Timurid Central Asia and Nasrid Granada. During the Timurid period,

cuerda seca tiles became an integral decorative element in architecture and were extensively traded and exported across the Islamic world. The dissemination of this technique by Persian artisans, who were originally referred to as the “Masters of Tabriz”, is evidenced by its adoption by the Ottoman and subsequently the Safavid cultures (see

Figure 18).

3.8.3. Innovation and Cultural Legacy in the Alhambra Palatine City

Within the Alhambra Palatine City, the use of architectural ceramics achieved a technical and artistic apex.

The Nasrid period (1238–1492) marked the culmination of centuries of Islamic tradition, combining the different techniques into a cohesive decorative language inside the Palatine City.

As analysed in the preceding sections, the gold lustre technique employed in the Alhambra during the Nasrid period was both symbolically charged and materially sophisticated, with deep artistic roots in earlier Islamic traditions from Persia, Iraq, and North Africa, although it conformed to stricter aniconic norms, focusing instead on calligraphy, geometry, and vegetal motifs.

The Alhambra relief-sculpted tiles are also a testament to the refinement of Nasrid architectural ceramic production. The aesthetic and symbolic programme embodied by these objects constitutes a vital component of the architectural and cultural legacy. Despite their reduced numbers, these tiles were deliberately selected for application in prominent elements of the Palatine City, most often in exterior areas, such as soffits of arches and plinths of façades, which necessitated both high flexibility and durability. The majority of the examples found, both in situ and in the stored collection of the Alhambra Museum, are stylistically paired with stucco and muqarnas interior elements in the city. This particular characteristic is indicative of a conscious aesthetic decision to enhance surface dynamism, emphasise depth, and create a visual impact.

In the context of

alicatado panels, composed of individually cut and painted

aliceres, the creation of multicoloured geometric compositions with extraordinary precision was achieved, thereby linking intellectual, craft, and aesthetic sophistication. The execution of these panels demanded advanced mathematical knowledge, production expertise, and material understanding [

65]. The technique was prominent in the Alhambra and became a hallmark of the city, where it reached unparalleled refinement in the Palace of the Lions and the Comares Palace.

A further distinctive element of the Nasrid style was the use of incrustación tiles. The integration of prefabricated ceramic pieces into previously glazed ceramic bases, often for cursive inscriptions, represented a significant innovation in the Nasrid craftsmen’s approach to Islamic architecture. This innovation marked the introduction of a new aesthetic and technical paradigm, unparalleled in earlier Islamic architecture. This technique enabled greater freedom for epigraphic stylisation and colour juxtaposition, advancing both the visual and semantic layers of architectural decoration.

The cuerda seca technique represented a significant innovation in the field of architectural design in Nasrid contexts. Indeed, it facilitated the creation of vibrant polychrome modular tile panels, sometimes in large compositions. This innovation had a profound effect on the conception of tilework design, introducing inscribed verses and prayers as part of the architecture.

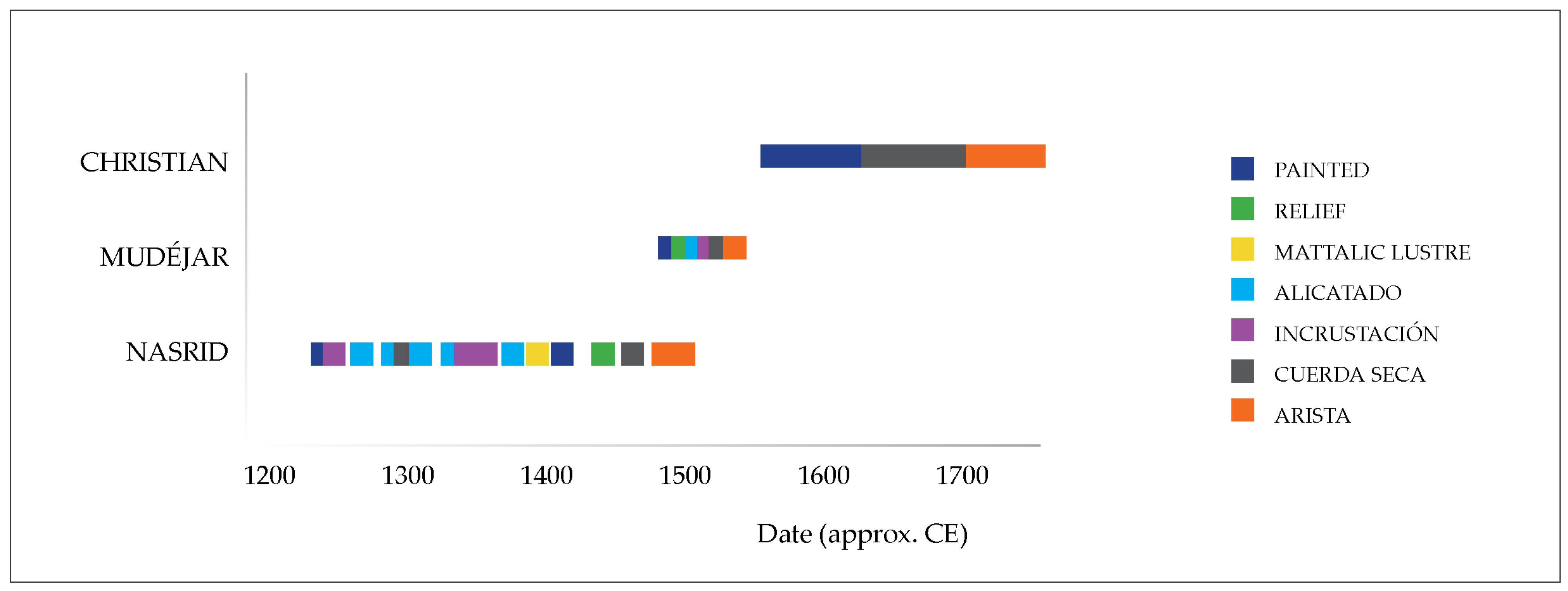

Following the Christian conquest of Granada in 1492,

Mudéjar artisans, often of Islamic descent, continued to produce different types of decorative techniques. Throughout the Christian period, ceramic traditions have endured, albeit undergoing significant transformation, particularly with regard to

cuerda seca, painted, and

arista techniques (see

Figure 19).

With regard to the cuerda seca tilework, Christian artisans were responsible for innovating the methodological execution and expanding the production of the different subtypes of this technique (flat, incised, recessed, or reinforced—either single or double) in the decorations of the Palatine City. Furthermore, the chromatic palette of a predominant cooler range, associated with a strong Islamic influence, was enriched by the gradual incorporation of warmer colours, such as yellow, ochre, and brownish tones. The production of other shapes of tiles, such as the L-shaped format (alizares), was also accentuated during the modern period.

In relation to the painted technique, new elements were introduced during the Christian period in the Palatine City, including royal and political emblems, Latin inscriptions, and Renaissance iconography. This resulted in a slight shift in focus from abstract geometry to figurative representation.

The production of arista tiles also underwent a period of significant growth and development in Mudéjar pottery workshops in the late 15th century, becoming increasingly prevalent from the first half of the 16th century onwards. This expansion can be attributed to the adoption of serial manufacturing techniques and the incorporation of design elements related to Renaissance and Gothic influences, resulting in a product of exportation from production centres such as Seville and Toledo. Initially associated with gold lustre, Arab inscriptions, and the Nasrid coat of arms (as seen in the most emblematic piece, known as “azulejo del escudo de la banda”), the arista tiles began to incorporate symbolism related to the Crown and the Christian expansion during this period.