Evaluating Older Adults’ Engagement with Digital Interpretation Exhibits in Museums: A Universal Design-Based Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. Museum Visitor Research and Older Visitors

2.3. Museum Exhibitions, Universal Design (UD), and Digital Interpretation

- UD1: Equitable Use.

- UD2: Flexibility in Use.

- UD3: Simple and Intuitive Use.

- UD4: Perceptible Information.

- UD5: Tolerance for Error.

- UD6: Low Physical Effort.

- UD7: Size and Space for Approach and Use.

2.4. Museum and Visitor Experience Evaluation

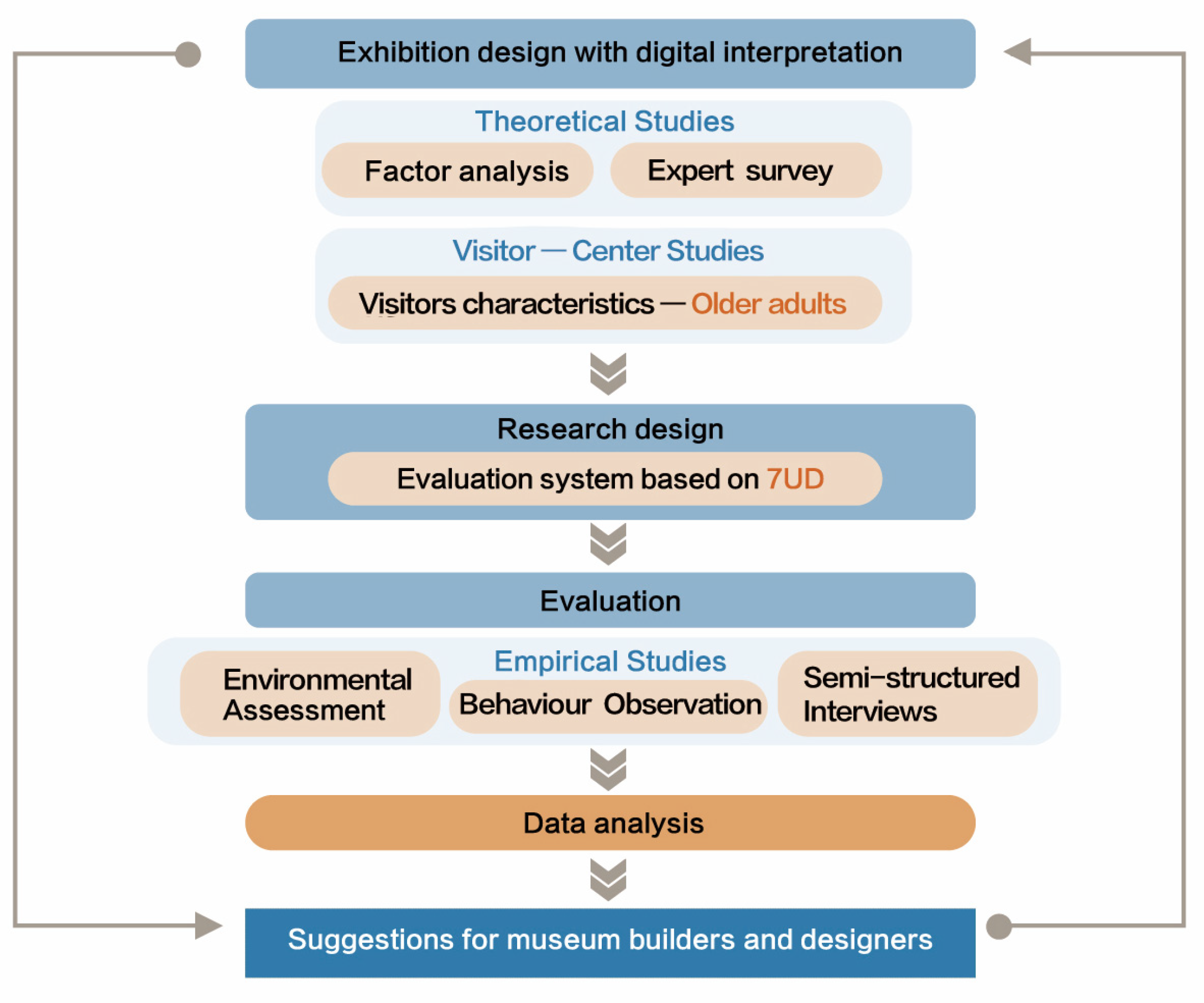

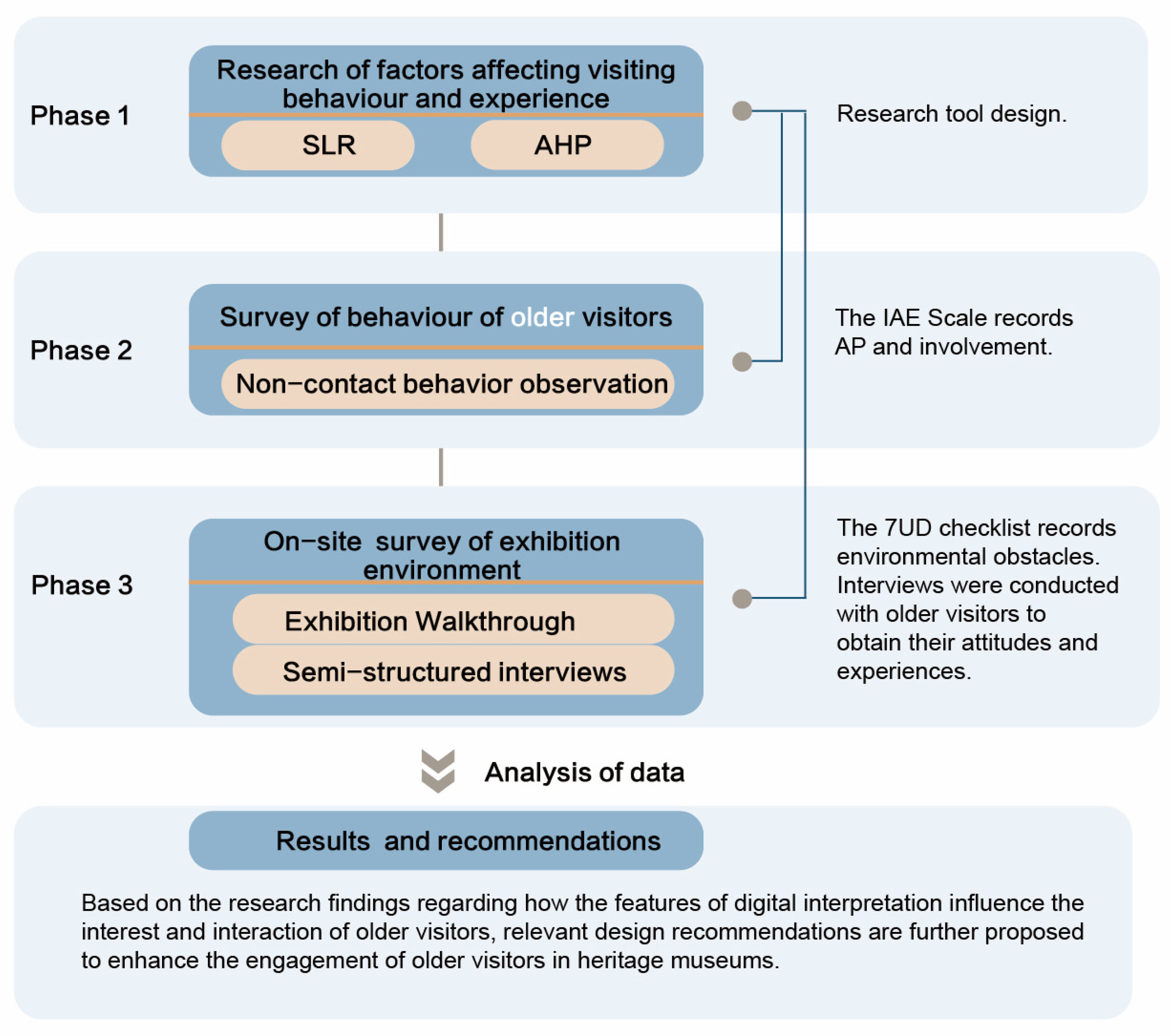

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Studies and Research Scope

3.1.1. Case Studies

3.1.2. Scope of This Research

3.2. Methods and Data Collection

3.2.1. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

3.2.2. Non-Contact Behavioural Observation Utilising the IAE Scale

3.2.3. Design Feature and Physical Environment Measurement by the 7UD Checklist

3.2.4. Semi-Structured Interviews

3.3. Population and Sample

3.3.1. Participants

3.3.2. Experts

4. Results

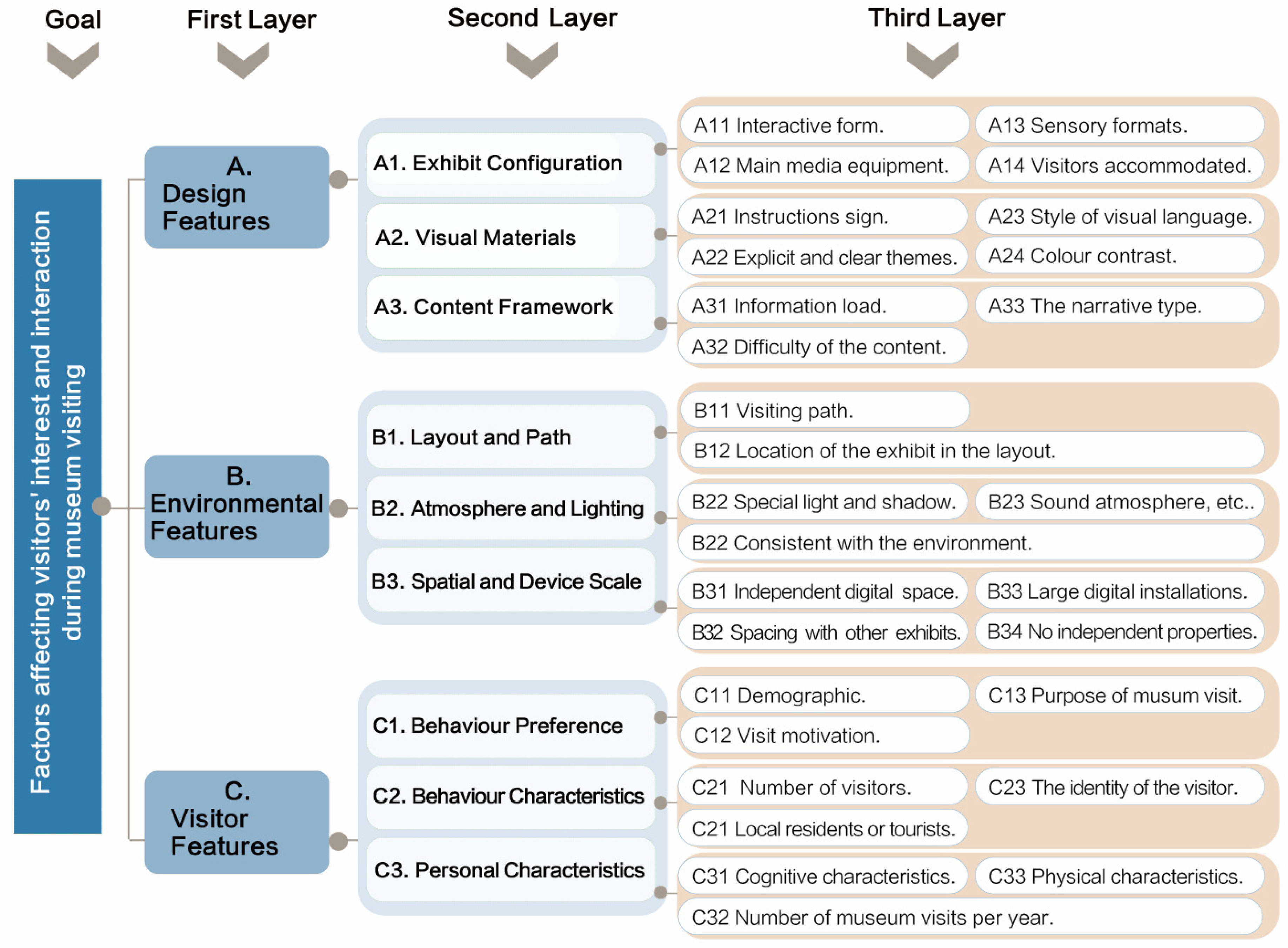

4.1. Factors Affecting the Interest and Engagement of Older Visitors

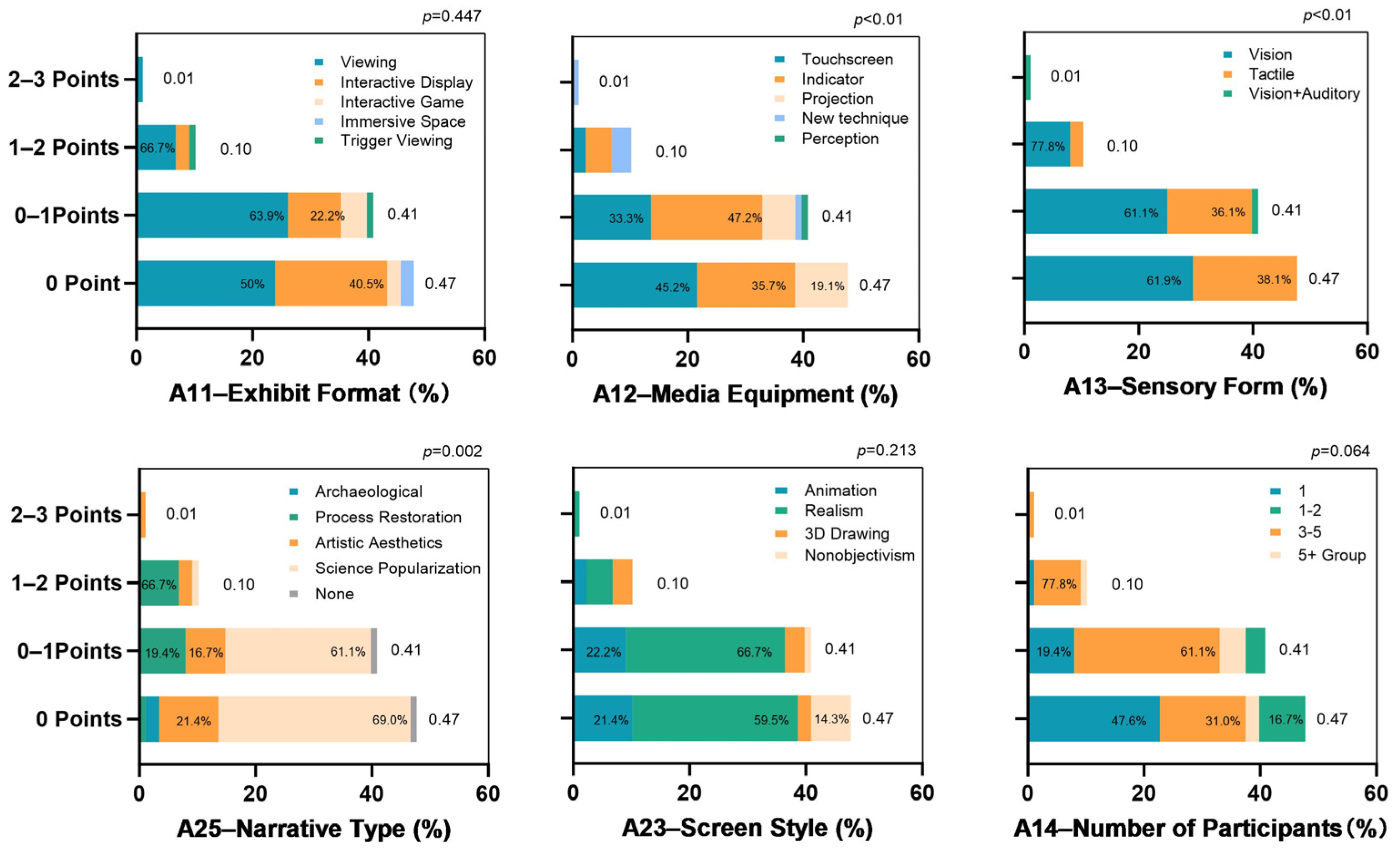

4.2. Analysis of Design Features of Digital Interpretation Exhibit

4.3. Analysing Behavioural Observation and Attraction Power (AP) of Digital Interpretation

4.4. Analysis of Environmental Features and UD Evaluation Results

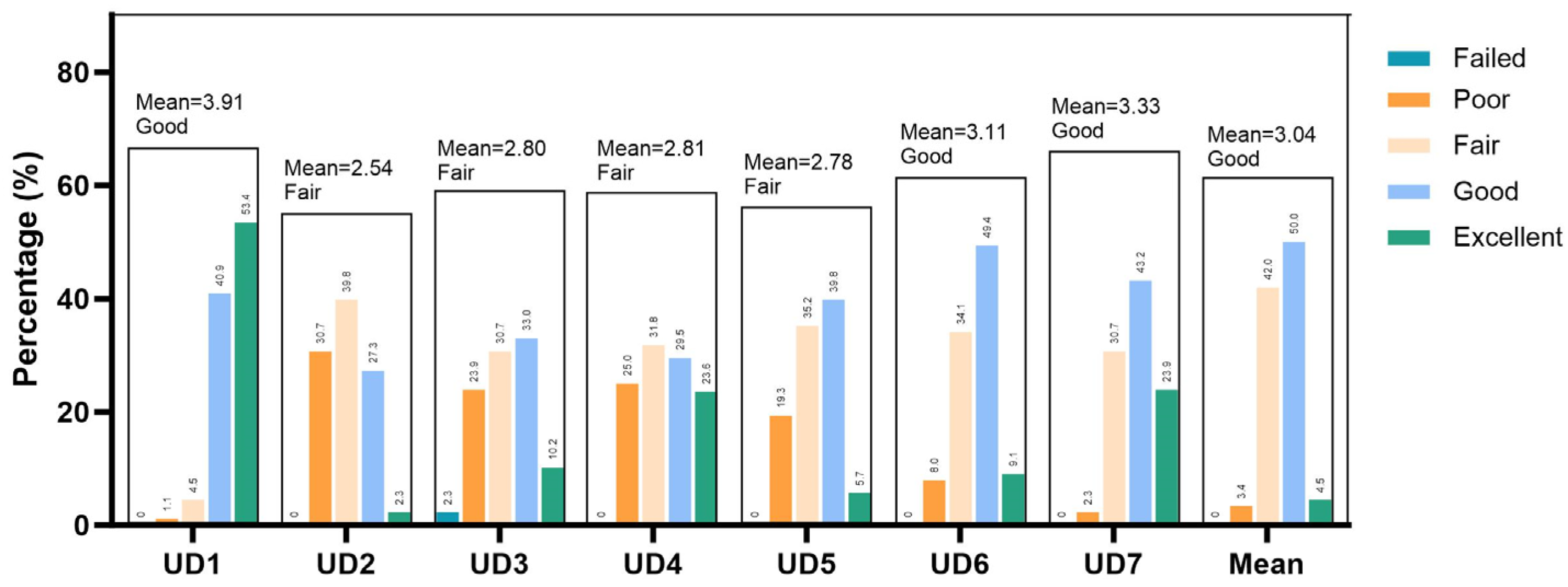

4.4.1. Analysis of UD Compliance Status for Digital Interpretation Exhibits

4.4.2. Analysis of the Correlation Between AP and UD Scores

4.4.3. Comparative Analysis of Visiting Barriers for Older Visitors and UD

4.5. Analysis of Interview Results with Older Visitors

4.5.1. Motivation and the First Impressions of the Digital Media

4.5.2. The Interactive Experience at the Behavioural Level of Engagement

4.5.3. Gains from Visit

4.6. Comparative Analysis: Three Museums

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of the Evaluation System

- (1)

- A satisfaction-based questionnaire survey aims to capture visitors’ attitudes and needs; however, the results are heavily reliant on participants’ responses [37], making it challenging to ascertain the actual behavioural reactions of older visitors when they encounter digital interpretation in museum settings. It is widely acknowledged that behavioural observation methods rely heavily on the subjective records of investigators. Consequently, standardised testing will enhance the reliability of a study [80]. In this evaluation system, rigorous scales are employed not only for behavioural observation but also for documenting design features and environmental features. Previous semantic analysis methods in research have largely depended on visitors’ linguistic proficiency and cognitive patterns [35]. However, the target demographic of this study—older adults—appears unsuitable for such an approach because of declines in cognitive abilities and physical perception. Thus, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), based on expert evaluation, was utilised to develop the scale and evaluation indicators for this study. Through a systematic literature review and a rigorous expert evaluation, potential biases of the researchers were minimised to the greatest extent possible.

- (2)

- Current evaluation practices are often influenced by a positivity bias in outcomes, where visitors report what museums wish to hear [92]. This became evident during our interview process. When asked about their impressions of digital media, the participants uniformly responded positively, expressing satisfaction. However, as conversations deepened, they became more willing to articulate the obstacles encountered during their visits and share more authentic perspectives.

- (3)

- The environment assessment, which incorporates universal design principles, offers a method for creating behavioural experiences for older visitors, with simultaneous attention to both physical and psychological environmental factors. It connects the concepts of exhibition designers with the behavioural responses and experiences of older visitors. This evaluation enables builders to identify which museum exhibition resources and efforts significantly impact elderly tourists and allows them to propose improvement suggestions based on these findings.

5.2. Discussion of Limitations

5.3. Discussion of the Evaluation Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UD | universal design |

| 7UD | seven principles of universal design |

| SLR | systematic literature review |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| AP | attraction power |

| UX | user experience |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Factors Affecting Visitors’ Interest and Participation Behaviour

| The Factors and Details Affecting Visitors’ Interest and Participation Behaviour |

|---|

| A11—Digital interaction form: 1. Viewing type; 2. Trigger Viewing Type; 3. Interactive Display Type; 4. Interactive Gaming Type; 5. Immersive Spaces Type. [29,39,52,72,80] |

| A12—Main media equipment: 1. Touchscreen or multi-touch screen; 2. intelligent sensing; 3. display; 4. projection; 5. new technologies, including VR, XR, or 3d mapping, etc., new technique. [18,19,73,74] |

| A13—Sensory participation format: 1. Visual; 2. visual + auditory; 3. tactile; 4. other senses or multisensory. [18,51,75,80,85] |

| A14—Number of people the digital exhibit can accommodate simultaneously: 1. One person; 2. 1–2 people operating or viewing; 3. 3–5 people simultaneously operating or viewing; 4. group. [8,80,87,88] |

| A21—Explicit signage or explanation systems. [34,79,83] |

| A22—Explicit and theme of the exhibit. [35,75] |

| A23—Visual styles presented: 1. Realistic style; 2. cartoon or animation style; 3. 3d drawing style; 4. abstract art style. [35,72,85] |

| A24—1. Contrast colour; 2. harmonising with surrounding colours. [65,81,82,87] |

| A31—Information load: 1. High; 2. moderate; 3. low. [11,34,82] |

| A32—Complexity of information: 1. Complex and difficult information; 2. concise and easy information. [11,34,46] |

| A32—Narrative type: 1. Archaeological documentation; 2. process interpretation and reappearance; 3. historical reappearance (including historical scenes, historical stories, architecture, etc.); 4. science popularisation; 5. artistic appreciation; 6. static image playback, non-narrative. [4,72,74] |

| B11—Layout: 1. Fixed single flow path; 2. flexible flow path; 3. located in complex multi-corridor flow paths. [29,34,46] |

| B12—Exhibit layout location: 1. Located along the main exhibition route; 2. situated on special exhibition routes; 3. positioned on secondary exhibition routes. [16,29,34] |

| B21—Dedicated lighting, projection, and other atmospheric elements. [18,51,64] |

| B22—Create a sound atmosphere. [51,53,65] |

| B31—Independent space. [30,34,47] |

| B32—There are partitions/separate desks/walls. [29,46,64] |

| B33—Configuration: 1. Large-scale media installations; 2. artistic installations; 3. comprehensive scenes; 4. independent digital device. [46,64,65,66] |

| B34—Does not possess independent attributes: 1. Large indicator; 2. small indicator. [46,64,65,66] |

| C11—Demographic characteristics. [4,8] |

| C12—Motivation and purposes. [4,8,36] |

| C13—Purposes of museum visiting. [4,8,36] |

| C23—Number and characteristics of visitors (alone or in a pair/group). [8,80] |

| C22—Out-of-town visitors or local visitors. [4,36] |

| C23 The identity characteristics of visitors, such as parent–child families, students, couples, experts, etc. [8,36,80] |

| C31—Cognitive characteristics, such as cultural background. [8,85] |

| C32—Number of museum visits/year. [8,11] |

| C33—Visitors’ physical characteristics and restrictions. [11] |

Appendix A.2. Research Tool

| Digital Media Attractiveness Record for Old Age Visitors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Museum: Location: | Date: | ||||||

| Page: | |||||||

| * Record declaration: F: Female; M: Male; D: People with disabilities Behavioural characteristics: whether it is a person, or two old people together, or with adult children, or with a preschool child | |||||||

| Item | Record time | ||||||

| NO. | Visitor Types | Score | Protocol | ||||

| F | M | D | Behavioural characteristics | Based | Add | ||

| e.g. | √ | Alone | 2 | 1 | An older man took photos. | ||

| 1. | |||||||

| 2. | |||||||

| 3. | |||||||

| 4. | |||||||

| 5. | |||||||

Appendix A.3. Research Results

| UD1 | UD2 | UD3 | UD4 | UD5 | UD6 | UD7 | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | 0.224 ** | 0.246 *** | 0.279 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.158 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.145 ** | 0.308 *** |

| +1 | 0.096 * | 0.147 ** | 0.151 *** | 0.158 *** | −0.018 | 0.121 ** | 0.03 | 0.141 ** |

| Total | 0.218 *** | 0.248 *** | 0.279 *** | 0.238 *** | 0.135 ** | 0.247 *** | 0.134 ** | 0.302 *** |

| 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 | 456 |

| β | SE | Beta | t | p | 95.0% Confidence Interval | Tolerance | VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.7 | 0.262 | −2.674 | 0.008 | −1.214 | −0.186 | ||||

| UD1 | 0.031 | 0.082 | 0.026 | 0.383 | 0.702 | −0.13 | 0.192 | 0.448 | 2.234 |

| UD2 | 0.053 | 0.088 | 0.047 | 0.608 | 0.543 | −0.119 | 0.226 | 0.34 | 2.941 |

| UD3 | 0.154 | 0.064 | 0.19 | 2.422 | 0.016 | 0.029 | 0.279 | 0.324 | 3.084 |

| UD4 | −0.014 | 0.054 | −0.018 | −0.251 | 0.802 | −0.12 | 0.093 | 0.378 | 2.645 |

| UD5 | 0.062 | 0.053 | 0.061 | 1.172 | 0.242 | −0.042 | 0.166 | 0.729 | 1.372 |

| UD6 | 0.128 | 0.059 | 0.128 | 2.189 | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.243 | 0.589 | 1.697 |

| UD7 | −0.028 | 0.058 | −0.028 | −0.486 | 0.627 | −0.142 | 0.086 | 0.612 | 1.634 |

| Category | Feature Words/Phrases | Frequency | Remarks/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature words | Favourable | 17 | Thought digital media was good/fine |

| Diversified forms | 10 | Positive evaluation of digital interpretation | |

| Unwilling | 9 | Digital devices are complicated or uninteresting | |

| Environment | 7 | Complain about dim lighting, crowded space, confusing routes, etc. | |

| Simple content | 6 | Criticism of the lack of depth in multimedia content | |

| Novelty | 5 | Digital media are novel and interesting | |

| Video playback | 5 | Specific forms, such as video playback | |

| Safe | 5 | Emphasise a safe and unblocked space | |

| Vivid content | 5 | Positive comments, such as “vivid picture” | |

| Physical objects | 4 | Focus on physical objects | |

| Needs of the elderly | 4 | Mention of elderly maladaptation problems, such as dizziness | |

| Unclear illustration | 4 | Interactive devices lack guidance | |

| Irrelevant content | 3 | Criticism of digital content is irrelevant to the exhibition | |

| Children | 3 | Controversy over interactive design for children | |

| Overlook | 3 | Not paying attention to digital interpretation | |

| Not interested | 3 | Not interested in digital interpretation | |

| Not for me | 3 | Not suitable for the elderly | |

| Gender | Female | 20 | The respondents were mainly female (64.52%) |

| Male | 11 | The proportion of respondents who are male was 35.48% | |

| Forms of visits | Couple | 10 | Common forms of tourists (such as couples travelling, friends group leisure) |

| Group | 9 | ||

| Companionship | 6 | The family visit form is mostly used for residents | |

| With kids | 3 | Take preschool children on a tour | |

| Visit alone | 3 | Common among professional visitors | |

| Motivation | Leisure and relaxation | 15 | Core needs are frequently mentioned by local tourists |

| Cultural tourism | 7 | Core motivation of non-local tourists | |

| Learning | 3 | Mentioned by professional visitors |

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Araujo, O.S.C.C.; Hinsliff-Smith, K.; Cachioni, M. Education and the relationships between museums and older audiences: A scoping review protocol. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 102, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. A study on age-friendly services in digital museums based on the psychology of aging seniors. Identif. Apprec. Cult. Relics 2024, 15, 78–81. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2024&filename=wwjs202415020 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Liu, Y. Evaluating visitor experience of digital interpretation and presentation technologies at cultural heritage sites: A case study of the old town, zuoying. Built Herit. 2020, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, Q.; Lacanienta, J.; Zhen, Z. Leisure participation and subjective well-being: Exploring gender differences among the elderly in Shanghai, China. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 69, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, H.; Noble, G. Museums, Health and Well-Being, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Harrison, D.; Nickpour, F. Applying inclusive design and digital storytelling to facilitate cultural tourism: A review and initial framework. Heritage 2023, 6, 1411–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, B.; Pajares, J.L.; Utray, F.; Moreno, L. Design for All in multimedia guides for museums. Soc. Humanist. Comput. Knowl. Soc. 2011, 27, 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filová, N.; Rollová, L.; Čerešňová, Z. Universal Design Principles Applied in Museums’ Historic Buildings. Prostor 2022, 30, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Sawadsri, A.; Harrison, D.; Nickpour, F. Museums for older adults and mobility-impaired people: Applying inclusive design principles and digital storytelling guidelines—a review. Heritage 2024, 7, 1893–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics Draft Compilation Guide. 2008. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/tradeserv/tourism/E-IRTS-Comp-Guide%202008%20For%20Web.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Kasemsarn, K.; Harrison, D.; Nickpour, F. Digital Storytelling Guideline Applied with Inclusive Design for Museum Presentation from Experts’ and Audiences’ Perspectives for Youth. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2023, 16, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, A.; Kares, E.M.; Abidin, H.Z. Digital cultural tourism: Older adults’ acceptance and use of digital cultural tourism services. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 23, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Nickpour, F. A conceptual framework for inclusive digital storytelling to increase diversity and motivation for cultural tourism in Thailand. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 229, 407–415. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324261317 (accessed on 16 January 2025). [PubMed]

- Mason, M. The elements of visitor experience in post·digital museum design. Des. Princ. Pract. Int. J. —Annu. Rev. 2020, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, N.A. Developing digital media for museum exhibitions: Environment, collaboration and delivery, Massey University. 2011. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10179/3188 (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Ken, F.-Y. The Real and the Virtual: Application of New Technological Media to Museum Exhibitions. Museol. Q. 2006, 20, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furferi, R.; Di Angelo, L.; Bertini, M.; Mazzanti, P.; De Vecchis, K.; Biffi, M. Enhancing traditional museum fruition: Current state and emerging tendencies. Heritage Sci. 2024, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.; Fernandes, P.; Veiga, A. Interactive technologies in museums: How digital installations and media are enhancing the visitors’ experience. In Handbook of Research on Technological Developments for Cultural Heritage and eTourism Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 30–53. [Google Scholar]

- Floch, J.; Jiang, S. One place, many stories digital storytelling for cultural heritage discovery in the landscape. In Proceedings of the 2015 Digital Heritage, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; Volume 2, pp. 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ibem, E.O.; Oni, O.O.; Umoren, E.; Ejiga, J. An appraisal of universal design compliance of museum buildings in southwest nigeria. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2017, 12, 13731–13741. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, R. Universal Design, Barrier-free Environments for Everyone; Designer West: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Charanya, P.; Sawadsri, A.; Bunyasakseri, T. Evidence-Based Research on Barriers and Physical Limitations in Hospital Public Zones Regarding the Universal Design Approach. Asian Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charanya, P.; Sawadsri, A.; Skates, H. An evaluation of public space accessibility using universal design principles at naresuan university hospital. In Designing Around People; Langdon, P., Lazar, J., Heylighen, A., Dong, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Excellence in Universal Design. Building for Everyone; a Universal Design Approach Building Types. 2012. Available online: https://universaldesign.ie/built-environment/building-for-everyone (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Schreffler, J.; Vasquez, I.E.; Chini, J.; James, W. Universal design for learning in postsecondary stem education for students with disabilities: A systematic literature review. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiak, M. A Sensory Place for All. In Contemporary Museum Architecture and Design: Theory and Practice of Place, 1st ed.; Lindsay, G., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-H. Relations between Museum Exhibition Layout and Visitor Behavior. Technol. Mus. Rev. 2012, 16, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Bahauddin, A.; Feng, J. Museum Fatigue: Spatial Design Narrative Strategies of the Mawangdui Han Tomb. Buildings 2024, 14, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antona, M.; Stephanidis, C. Universal Access in Human·Computer Interaction. In User and Context Diversity: 16th International Conference, UAHCI 2022. In Proceedings of the 24th HCI International Conference, HCII 2022, Part II, Virtual Event, 26 June–1 July 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 13309, pp. 371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. J. Math. Psychology. 1977, 15, 234–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duleba, S.; Moslem, S. Examining Pareto optimality in analytic hierarchy process on real Data: An application in public transport service development. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 116, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-J. Museum Fatigue: Weight Analysis of Spatial Factors. J. Mus. Cult. 2022, 23, 35–75. Available online: https://www.airitilibrary.com/Article/Detail?DocID=P20161128001-N202305260007-00003 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- King, E.; Smith, M.P.; Wilson, P.F.; Stott, J.F.; Williams, M.A. Evaluating museum exhibits: Quantifying visitor experience and museum impact with user experience methodologies. Curator Mus. J. 2025, 68, 163–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chang, P.-C.; Tsai, M.-F. How physical environment impacts visitors’ behavior in learning-based tourism—The example of technology museum. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharetha, S.; Hassanain, M.A.; Alshibani, A.; Ouis, D.; Gomaa, M.M.; Ezz, M.S. A post-occupancy evaluation framework for enhancing resident satisfaction and building performance in multi-story residential developments in saudi arabia. Architecture 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardia, S.; Khare, R.; Khare, A. Universal access in heritage sites: A case study on historic sites in jaipur, india. In Universal Design 2016: Learning from the Past, Designing for the Future; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 229, pp. 419–430. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Luo, T. Evaluating interactive digital exhibit characteristics in science museums and their effects on child engagement. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2024, 40, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Yang, M.; Liang, J.; Bai, H.; Li, R.; Law, A. A review of the tools and techniques used in the digital preservation of architectural heritage within disaster cycles. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.J.; Lockyer, B.; Camic, P.M.; Chatterjee, H.J. Effects of a museum-based social prescription intervention on quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing in older adults. Perspect. Public Health 2018, 138, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Older people’s attitudes towards emerging technologies: A systematic literature review. Public Underst. Sci. 2023, 32, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknecht, S. The role of new media in communicating and shaping older adult stories. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Acceptance, Communication and Participation: 4th International Conference, ITAP 2018, Held as Part of HCI International 2018, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–20 July 2018; Proceedings, Part I 4; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 478–491. [Google Scholar]

- Smiraglia, C. Targeted museum programs for older adults: A research and program review. Curator Mus. J. 2016, 59, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoespel, K.J. Navigating museum space. In Museum Configurations: An inquiry into the Design of Spatial Syntaxes; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood, S.; Huimei, C. Discussion on the issue of guiding visitors and visiting routes. Museol. Q. 1992, 6, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ken, F.-Y. The Body, Behavior and Museum Exhibits. Museol. Q. 2003, 17, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldamshiry, K.; Khalil, M. Museum Visitors Learning Identities Interrelationships with Their Experiences; The British University in Egypt: Cairo, Egypt, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhenrong, Y. Family visitors visit museums to explore parent-child interaction. Ling Tung J. 2009, 25, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chu, S.-C. Behaviors of Family Groups in a Science Museum: Interpretation of Identity Approach. Museol. Q. 2010, 24, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, S.I. Kid-friendly Museum Exhibit: A Case Study of “Paleontology Interactive Experience” Exhibition of NTM. Taiwan Nat. Sci. 2019, 38, 30–37. Available online: http://www.airitilibrary.cn/Publication/alDetailedMesh?DocID=P20150629002-201912-202004200006-202004200006-30-37 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Li, Q. Effects of different types of digital exhibits on children’s experiences in science museums. Des. J. 2022, 25, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaby, N.; Assaraf, O.B.Z.; Tal, T. The particular aspects of science museum exhibits that encourage students’ engagement. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2017, 26, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Xia, T.; Shu, T.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J. Watching nature through the window cannot be overlooked! Nexus between green window view, physical activity intention, and intensity among older adults. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 257, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovčič, A.; Taipale, S.; Rogelj, A.; Dolničar, V. Design of mobile phones for older adults: An empirical analysis of design guidelines and checklists for feature phones and smartphones. Int. J. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wineman, J.; Peponis, J. Constructing spatial meaning: Spatial affordances in museum design. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkranikal, J.; Powell, R. From history to reality–Engaging with visitors in the imperial war museum (north). Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2014, 29, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Backer, F.; Peeters, J.; Kindekens, A.; Brosens, D.; Elias, W.; Lombaerts, K. Adult visitors in museum learning environments. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 191, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElDamshiry, K.K.; Moussa, R.R. A Prototype Evaluation Tool for Museum Exhibition Design: Aligning Display Techniques with Learning Identities; The British University in Egypt: Cairo, Egypt, 2022; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Mavragani, E.; Constantine, L. Factors affecting museum visitors’ satisfaction: The case of greek museums. Tourism 2013, 8, 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Lin, S.; Tian, Y. Immersive museums in the digital age: Exploring the impact of virtual reality on visitor satisfaction and loyalty. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ito, H. Visitor’s experience evaluation of applied projection mapping technology at cultural heritage and tourism sites: The case of China Tangcheng. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, S.; Cesta, A.; Cortellessa, G.; De Benedictis, R.; Fracasso, F.; Leopardi, L.; Ligios, L.; Lombardi, E.; Malatesta, S.G.; Oddi, A.; et al. Evaluating visitors’ experience in museum: Comparing artificial intelligence and multi-partitioned analysis. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 33, e00340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitgood, S. An Attention-Value Model of Museum Visitors. 2013. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9159214/An_Attention_Value_Model_of_Museum_visitors63 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Vázquez, M.G. Attention and value: Keys to understanding museum visitors (atención y valor: Claves para comprender a los visitantes de museos), de stephen bitgood. Interv. Int. De Conserv. Restauracion Y Museol. 2010, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitgood, S. Exhibition Design That Provides High Value and Engages Visitor Attention. 2019. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/26693617/Exhibition_Design_that_Provides_High_Value_and_Engages_Visitor_Attention65 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Story, M.F.; Mueller, J.L.; Mace, R.L. The Universal Design File: Designing for People of All Ages and Abilities. Revised Edition’. Center for Universal Design, NC State University, Box 8613, Raleigh, NC 27695-8613 ($24). 1998. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED460554 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Tešin, A.; Bozic, S.; Pivac, T.; Vujicic, M.; Strålman, S.O. From children to seniors: Is culture accessible to everyone? Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 15, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Phaholthep, C. Evaluating museum environment composition containing digital media interaction to improve communication efficiency. Buildings 2025, 15, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Nogare, C.D.; Scuderi, R. Frequency of museum attendance: Motivation matters. J. Cult. Econ. 2016, 40, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chang, S. A study of digital exhibition visual design led by digital twin and VR technology. Meas. Sensors 2024, 31, 100970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T. Digital Narrative: Research on Museum Design in the Context of New Technology. J. Nanjing Arts (Fine Arts Des.) 2020, 43, 165–171+210. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFDLAST2020&filename=NJYS202003031 (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Guobin, W. The concept analysis of interactive museum in exhibition design. Packag. Eng. 2015, 36, 26–29. Available online: http://www.designartj.com/bzgcysb/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=201508007&flag=1 (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Ning, C.L.; Xu, J.; Yao, K.L. Interactive Experience Design and Knowledge Dissemination of Museum Exhibitions in the age of Digital Media:Taking WonderKamers 2.0 and MicroPia as Examples. Southeast Cult. 2022, 2, 169–177. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFDLAST2022&filename=DNWH202202019 (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Chen, L. A Rediscovery of Place: Digital Narratives for Museum Exhibitions. Southeast Acad. Res. 2023, 136–146. Available online: https://dnxsh.cbpt.cnki.net/WKG/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=df5e4a25-ad95-4ac0-9368-8d6bc43cbb4a (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Norman, D.A. Introduction to This Special Section on Beauty, Goodness, and Usability. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 2004, 19, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, D.; Ciolfi, L.; Van Dijk, D.; Hornecker, E.; Not, E.; Schmidt, A. Integrating material and digital. Interactions 2013, 20, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Spatial Presence: How Immersive Experiences Are Generated in Virtual Environments? Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Borhegyi, S.F. Visual Communication in the Science Museum. Curator: Mus. J. 1963, 6, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.C.; Fung, P.Y.; Din, H. A Micro-Study on the Attractiveness and Knowledge Transfer of Multimedia Interactive Devices in the Paleontological Exhibition Evolution of Life on Earth at National Taiwan Museum’s Natural History Branch. Museol. Q. 2023, 37, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.-S.; Chen, C.-Y. The Visitor Experience Study of Different Exhibition Types-Kaohsiung Museum of Shadow Puppet on Example. Vis. Arts Forum 2018, 13, 84–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood, S. Appendix B: Checklist for managing visitor attention. In Attention and Value: Keys to Understanding Museum Visitors; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Knez, E.I.; Wright, A.G. The Museum as a Communications System: An Assessment of Cameron’s Viewpoint. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1970.tb00404.x (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Ardoin, N.M.; Schuh, J.S.; Khalil, K.A. Environmental behavior of visitors to a science museum. Visit. Stud. 2016, 19, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brida, J.G.; Meleddu, M.; Pulina, M. Understanding museum visitors’ experience: A comparative study. J. Cult. Heritage Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiang, L.-R.; Lin, H.-J.; Huang, Y.L.; Hsiao, Y.-E.; Tsai, J.-J. An Analysis of Effectiveness on the Children-friendly Exhibit of National Taiwan Museum. J. Natl. Taiwan Mus. 2015, 68, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-W. Museum Visitor Experience and Evaluation of Multimedia Interaction: A Case Study of the Exhibition “Divine Guidance-Chance from God”. Museol. Q. 2014, 28, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, F.; Pigott, J.; Taylor, A.; Thorne, S.; Pinney, J. Creative environmental exhibition: Revealing insights through multi-sensory museum experiences and vignette analysis for enhanced audience engagement. Heritage 2023, 7, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalowitz, S.S.; Bronnenkant, K. Timing and tracking: Unlocking visitor behavior. Visit. Stud. 2009, 12, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.Y.; Qian, S.Q. Using TPB Theory to Discuss the Tourists’ Intention of Museum—A Case of the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts. Asia-Pac. Econ. Manag. 2013, 16, 39–59. Available online: http://www.airitilibrary.cn/Publication/alDetailedMesh?DocID=16828062-201303-201310080014-201310080014-39-59 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Johanson, K.; Glow, H. A Virtuous Circle: The positive evaluation phenomenon in arts audience research. Particip. J. Audience Recept. Stud. 2015, 12, 254–270. [Google Scholar]

| Name of the Museum | City and Year | Museum Features |

|---|---|---|

| Suzhou Museum West Branch • nternational Hall. • Historical and Cultural Hall. | SuZhou 2021 | Suzhou is a renowned tourist city in China. This museum won the 2022 National Top Ten Museum Exhibition Excellence Award; it interprets Suzhou’s regional culture and heritage through various digital interpretation devices, and the thematic exhibition in the International Hall features popular digital interpretation technologies. |

| Shanghai Museum East Branch • Ancient Bronze Gallery. • Ancient Chinese Jade Gallery. • Chinese Numismatics Gallery. • Ancient Ceramics Gallery. | ShangHai 2024 | The newly completed Shanghai Museum East Branch is dedicated to displaying ancient Chinese art and cultural heritage. Its promotional focus is on creating a “visitor-friendly” and “digitally intelligent” museum, which attract large numbers of residents, tourists, and culture enthusiasts of all age groups. |

| Chiangnan Watery Region Culture Museum of China • Basic Exhibition Hall. | HangZhou 2022 | Chiangnan Watery Town’s unique cultural and architectural heritage earned it the 2022 China Museum Top Ten Exhibition Excellence Recommendation Prize. The exhibition employs extensive digital media to interpret and display heritage and culture, and it has also been unanimously praised by the industry. |

| Outline of Semi-Structured Interview | |

|---|---|

| NO. | Questions that may be posed to interviewees during the interview |

| 1 | Why did you come to the museum? Do you like museums? |

| 2 | Which digital exhibit attracted you? What was the reason it caught your attention? |

| 3 | What are your thoughts on the design of the digital exhibits? Did it meet your expectations? |

| 4 | Did you use the digital interactive device? How was your experience with the entire operation process? |

| 5 | What issues have you encountered while engaging in digital interpretation and interactions? |

| 6 | What issues do you encounter during the process of acquiring knowledge or information? |

| 7 | How do you find the exhibition environment? |

| 8 | Do you have any other terrible experiences? |

| 9 | What suggestions do you have for the digital exhibits in this museum? |

| No. | Type | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topological Relationship Diagram | Example of a Photo from the Exhibition | ||

| 1 | Viewing-Based Type | Present the objects and content to the visitors through multimedia formats, such as audio or video. The exhibits automatically play and demonstrate without requiring any visitor interaction, with no option to control the playback progress [80]. | |

|  | ||

| 2 | Trigger Viewing Type | The exhibit is activated and triggered by visitors, with its dynamic process pre-set, and the visitors’ actions do not affect the progression of the display [80]. | |

|  | ||

| 3 | Interactive Display Type | An interactive system designed utilising machinery, electrical power, and related technologies, where the visitors can interact with designed programs through a computer screen and also with the exhibit, responding differently based on the operator’s input, with mutual feedback between the two [29,88]. | |

|  | ||

| 4 | Interactive Gaming Type | By applying gaming concepts, elements, or mechanics to interactive exhibits, visitors engage with various forms of participatory displays, such as gaming programs, artistic creations, competitive games, and physically interactive games, allowing participants to acquire knowledge through gameplay [39,72,80]. | |

|  | ||

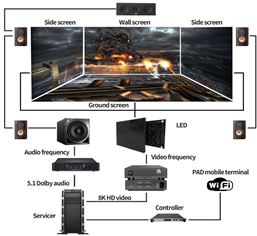

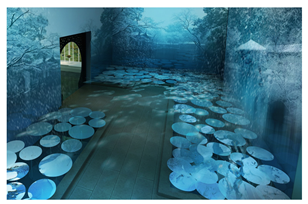

| 5 | Immersive Spaces Type | The information is aggregated into a complete spatial context, where interactive installations integrate emerging technologies with sensory experiences, aiming not only to provide visual experiences but also to deepen the audience’s multisensory engagement through technology [51,72]. | |

|  | ||

| AP Score | Female | Male | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 181 | 141 | 322 | 70.61% |

| 1 | 43 | 38 | 81 | 17.76% |

| 2 | 31 | 19 | 50 | 10.96% |

| 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.66% |

| Total | 258 | 198 | 456 | |

| +1 | 11 | 4 | 115 | 3.29% |

| Mean | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.45 |

| Suggestions for Digital Exhibit Design and Improvement Based on Seven Principles of UD | |

|---|---|

| Phenomenon 1: Older visitors were not attracted when approaching the digital interpretation. | |

| Problem analysis | • Older visitors cannot recognise the purpose and function of digital exhibits, considering them irrelevant to the exhibition. • The digital exhibit location deviates from the main content line. • Small scale, low recognition. |

| With UD | Not UD2; not UD3; not UD7 |

| Suggestions: • If possible, position digital exhibits along the main exhibition path, ensuring they are visible and easy to locate. When considering older visitors, digital interpretation should not be placed in cramped corners. • The visual presentation of digital exhibits should create a striking contrast with the surrounding environment to enhance their appeal. • Colour contrast in specific digital regions. • Create aesthetically pleasing and easily comprehensible logos and pictograms to aid in the recognition of the functions of digital exhibits. • Set appropriate partitions and dividers for screening. Independent exhibits are more effective at capturing visitors’ attention, particularly that of the elderly. • Considering the needs of various types of visitors, it is advisable to install displays of different sizes whenever possible. For instance, larger displays that align with the general public’s cognition, along with attractive headline descriptions, should be provided. Moreover, alternative avenues for interpretation and inquiry should be provided for professional visitors. • Clear directional signs or maps should be placed in areas prone to confusion—maps suitable for the elderly. | |

| Phenomenon 2: Older visitors noticed the digital interpretation but did not stay. | |

| Problem analysis | • Within the same exhibition, digital interpretation with similar content and visual materials loses its appeal. • The digital exhibit lacks a clear theme and is deemed as difficult-to-understand content. • The style of visual materials is judged to be exclusive to young people or children. • The environment being too dark or crowded is considered unsafe. • Located on a secondary route, requiring additional walking to reach. • Location is difficult to access. |

| With UD | Not UD1; not UD2; not UD3; not UD4; not UD5; not UD6 |

| Suggestions: • Use various communication methods to enable visitors to understand the content from different perspectives, avoiding repetitive content and narrative form and addressing the elderly’s need for concise and intuitive information. • A clear theme should be established for the digital interpretation exhibit, closely connected with the main content of the exhibition. This ensures that visitors with varying abilities can understand the forthcoming content. The theme should be clear and succinct. • Signage should be eye-catching and prominent to accommodate visitors of all types and cultural backgrounds. • Digital exhibits should have a visual identity and guidance that resonates with the psychological characteristics of different visitor types while steering clear of overly entertainment-focused or childishly styled guidance. • The digital display environment should have appropriate lighting, taking into account the visual characteristics of elderly audiences. Overly dim spatial conditions should not be created merely for atmospheric purposes. • The surrounding environment of digital equipment should be safeguarded against potential hazards, such as dark environments, protruding obstacles, and narrow passages. • Digital interpretation exhibits should be placed along the main route, but not at traffic nodes, to prevent congestion. • Digital exhibits should be established in relatively independent spaces or locations to prevent interference with surrounding exhibits. •Digital exhibits should be located in a manner that is accessible to all, avoiding obstacles such as steps, narrow bridges, sunken areas, or other features that could impede the access of elderly or disabled individuals. | |

| Phenomenon 3: Older visitors noticed the digital interpretation but only made brief stops. | |

| Problem analysis | • The content load is too heavy, making it difficult to capture important information. • The content is complex and considered overly specialised, requiring mental effort. • The content is simple and deemed meaningless. • The content requires interactive operation and is considered unrelated to oneself. • Glare, noise, and other uncomfortable physical environments. |

| With UD | Not UD3; not UD4; not UD6; not UD7 |

| Suggestions: • The content framework for digital interpretation organises information by importance, with presentation methods requiring intuitiveness and conciseness. • Establish a content framework that aligns with the cognitive levels of visitors from various age groups, avoiding excessive difficulty or oversimplification. Incorporate culture and knowledge that is more closely related to daily life, rather than emphasising specialisation. • Adopting a content framework that progresses from foundational to advanced levels can meet the needs of visitors with diverse professional backgrounds. • Sufficient space should be maintained between exhibits, such as the spacing between digital media and physical exhibits or explanatory information. Avoid information overload and an excessive cognitive burden. • Equip digital interactive exhibits with concise, visual operation instructions. Guide older visitors, as these are designed specifically for them. • Establish dedicated guidance instructions for older visitors near digital exhibits, indicating that these are interactive digital displays they can engage with. • Provide a suitable and comfortable viewing/experience space for non-operating users. • The media space should utilise glare-free spatial decorative materials. | |

| Phenomenon 4: Older visitors engage with digital exhibits, but do not involve or complete the full visit. | |

| Problems analysis | • The duration is lengthy, and the lack of rest seating leads to excessive physical exertion. • Prolonged exposure to unsuitable lighting conditions leads to visual fatigue. • Requires maintaining a highly physically demanding posture for extended periods, such as looking upward or bending over. • The content fails to meet expectations; for instance, instead of providing background interpretations, it merely offers displays of physical exhibits. |

| With UD | Not UD4; not UD5; not UD6 |

| Suggestions: • Comfortable operating, interaction time should not be too long. • Provide temporary seating for visitors, which should consist of chairs designed to accommodate the physical characteristics of elderly visitors. • Digital media exhibits require appropriate lighting and an environment conducive to easy identification and reading. • Digital devices should be placed within the normal line of sight, not positioned above display cabinets, on the floor, or on lower tabletops. • Considering the operational characteristics of visitors with different physical attributes, such as older visitors with reduced dexterity, the need for precise operations should be minimised. • The narrative structure of digital interpretation should eschew repetitive introductions of physical exhibits, as procedural, three-dimensional, and storytelling interpretations are more appealing to elderly visitors. Examples include procedural explanations and illustrations that restore historical scenes through scene reconstruction. • Adopt a visual interpretation approach to present engaging and entertaining content within an appropriate duration, ensuring to avoid excessive cognitive load to maintain attention. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ai, L.; Phaholthep, C. Evaluating Older Adults’ Engagement with Digital Interpretation Exhibits in Museums: A Universal Design-Based Approach. Heritage 2025, 8, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060229

Ai L, Phaholthep C. Evaluating Older Adults’ Engagement with Digital Interpretation Exhibits in Museums: A Universal Design-Based Approach. Heritage. 2025; 8(6):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060229

Chicago/Turabian StyleAi, Lu, and Charanya Phaholthep. 2025. "Evaluating Older Adults’ Engagement with Digital Interpretation Exhibits in Museums: A Universal Design-Based Approach" Heritage 8, no. 6: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060229

APA StyleAi, L., & Phaholthep, C. (2025). Evaluating Older Adults’ Engagement with Digital Interpretation Exhibits in Museums: A Universal Design-Based Approach. Heritage, 8(6), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060229