1. Introduction

Cultural heritage, understood as the set of tangible and intangible assets inherited from past generations, constitutes an invaluable resource for contemporary societies. In this regard, architectural heritage holds a significant place within this broader concept, serving as a tangible representation of the history, identity, and values of the regions in which it resides. This type of heritage has a multifaceted dimension that encompasses cultural, social, territorial, and economic aspects, being not only a symbol of local, regional, or, in some cases, global identity but also a driving force for the development of economic activities, especially those related to tourism and cultural revitalization [

1].

Architectural monuments, as remnants of bygone eras, tell the stories of the civilizations that built them, showcasing the artistic styles, technological progress, and societal values of several periods. However, their historical and artistic values, as well as their roles in the formation of the collective memory, contrast with their inherent vulnerabilities. The fragility of the architectural heritage exposes it to multiple threats [

2], including (i) the passage of time and inclement weather in addition to the effects derived from climate change, such as rising sea levels or changes in rainfall and temperatures [

3]; (ii) abandonment and loss of functionality, common in rural or unpopulated areas, where the lack of use and maintenance accelerate its deterioration [

4,

5]; (iii) destructive human actions, such as vandalism and armed conflicts, which have devastated emblematic monuments in different regions of the world [

6,

7]; (iv) accidental disasters, such as fires, landslides, earthquakes, or volcanic eruptions, which have seriously affected heritage assets of great importance [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]; and (v) impacts caused by the mismanagement of human activities, including mass tourism, insufficient rehabilitation efforts, urban development projects that overlook the heritage value, and the lack of resources dedicated to the preservation of these cultural assets [

15,

16]. These and other causes underline the need for efficient management and active cooperation among governments, international institutions, local communities, and experts in different disciplines to ensure the protection of this valuable heritage. In this regard, government administrations, through specific laws; agencies such as UNESCO, thanks to its international programs and regulations; and other organizations at the national or international level, through innovative proposals, play crucial roles in safeguarding cultural heritage at the global level [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Their collaboration is essential to establish solid legal frameworks, promote sustainable conservation strategies, and ensure the effective protection of these assets against the multiple threats they face.

With the objective of fostering a global and coordinated approach, the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage was adopted in Paris in 1972 [

18]. This international treaty represents a global commitment to protect and preserve sites of exceptional cultural and natural values for future generations, recognizing their importance not only at the local or national level but also for humanity as a whole. Currently, there are 1223 World Heritage properties, distributed across 168 countries (the last consultation was on 21 January 2025—

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/). It is interesting to note that the World Heritage List has been supplemented with an intuitive color legend that clearly identifies the sites that are in danger. Through a red marking system, those places that face imminent risks are indicated, whether due to the threats of armed conflict, natural disasters, or the pressure of human activities, such as mass tourism or uncontrolled urbanization. This visual classification facilitates the immediate understanding of the areas that require urgent intervention to ensure their conservation. Another point to note about this proposal is that most of the properties on the World Heritage List are located in developed regions, especially in Europe, which leads to unequal representation. In order to address this lack of diversity, UNESCO launched the Global Strategy in 1994, which aimed to create a more balanced and representative list of the world’s cultural and natural treasures [

21]. The strategy encouraged countries to draw up tentative lists and to propose assets from underrepresented categories and regions in order to include greater geographical and cultural diversity on the World Heritage List and promote a more inclusive and diverse vision of human heritage. Furthermore, it is important to mention that despite UNESCO’s valuable work in creating the World Heritage List, only a tiny fraction of the existing heritage assets is selected to be included on it. In fact, there is a vast amount of cultural and natural assets that although not internationally recognized, requires appropriate management and conservation actions. These tasks must be tackled by government administrations as well as by other local and national initiatives that promote the protection of this heritage at the country level.

At the global scale, several major organizations play crucial roles in heritage preservation. The World Monuments Fund (WMF) produces the World Monuments Watch, a biennial list of cultural sites worldwide that are at risk due to factors such as environmental conditions, conflicts, or neglect. The WMF supports conservation projects and awareness campaigns in collaboration with local communities. Similarly, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) [

22,

23,

24] advises UNESCO on heritage management and publishes reports on sites at risk. Its Heritage-at-Risk Program assesses threats such as natural disasters, armed conflicts, and urban expansion, providing expert recommendations for mitigation and conservation.

Within Europe, Europa Nostra [

25] stands as a leading civil society organization dedicated to cultural heritage protection. Acting as a bridge between citizens and EU institutions, Europa Nostra raises awareness of the value of the cultural heritage, advocates for its integration into EU policies with appropriate funding, and actively shapes policy discussions and decision making at the European level. One of its flagship initiatives is the “Seven Most Endangered” [

26] program, developed in collaboration with the European Investment Bank Institute, which identifies and supports the conservation of heritage sites at risk across Europe. Additionally, Europa Nostra grants the European Heritage Awards to recognize outstanding projects in conservation, research, and heritage education.

In the case of Spain, in addition to the heritage protection laws, and as a complement to international efforts, an important initiative promoted by the association Hispania Nostra [

27] is being carried out. This approach takes the form of the Red List of Heritage (the last consultation was on 21 January 2025—

https://www.listarojapatrimonio.hispanianostra.org/), a project that identifies the Spanish cultural assets that are at serious risk of disappearing or deteriorating [

28]. The possible threats to these assets include abandonment, the lack of adequate maintenance, institutional disinterest, and the negative impacts of human activities, such as excessive urbanization or resource extraction. By highlighting these threats, the Red List seeks to raise public awareness and mobilize institutions and citizens to protect and conserve this heritage. Hispania Nostra aims to raise the awareness of the importance of preserving these assets not only for their historical and cultural values but also as key elements for the collective identity of communities. The initiative encourages collaboration among governments, the private sector, and civil society in order to implement effective conservation measures and ensure that these assets do not disappear but are preserved for future generations.

However, while these initiatives concentrate on highlighting the previously identified or anticipated issues, such as those caused by armed conflicts or the lack of maintenance, there are other unforeseen factors that can equally threaten our heritage in a devastating manner. One of the most alarming aspects of heritage conservation is that although some assets may seem to be out of immediate danger, they can suffer irreparable damage due to fortuitous incidents or natural disasters [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. This lack of preparedness causes widespread concern, as responses are often delayed or insufficient, worsening the impacts of such events. The 2019 fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris exemplifies how a sudden incident can compromise a globally recognized cultural symbol, threatening both its physical integrity and the intangible heritage it represents [

8,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Despite having withstood centuries of wars, revolutions, and natural disasters, the cathedral suffered significant damage due to a fire of an unknown origin and the absence of effective preventive measures. This event highlights the vulnerability of heritage sites, even those considered as well protected and maintained.

In addition to the above, in order to better situate the present study, it is important to clarify several key concepts that will be mentioned throughout this document.

Senses refer to the multisensory experiences (visual, auditory, tactile, and even olfactory) that shape how individuals perceive and engage with heritage spaces.

Emotions encompass the affective responses, such as nostalgia, grief, awe, or pride, that arise in relation to cultural landmarks and memories.

Related heritage includes not only officially designated monuments but also everyday spaces and sites that communities imbue with meaning, often through shared memories and traditions.

Monuments, in this context, are physical structures or places that commemorate historical events, figures, or values, serving as tangible symbols of the collective identity and historical memory. In the literature, heritage has long been linked to emotional and affective experiences [

40,

41]. Authors such as Nora [

42] have explored how monuments function as

lieux de mémoire (sites that anchor the collective memory), while recent scholarship [

43,

44] has examined how emotions not only shape individual responses to heritage but also influence heritage practices and policies. Furthermore, studies in post-conflict contexts [

45] highlight how emotional impact plays central roles in the reception and interpretation of heritage, suggesting that the evaluation of emotional responses is crucial in understanding the societal function and resonance of cultural sites.

Given the importance of the incident discussed before, the aim of this research is to analyze the public’s perception of the reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral after the 2019 fire. To achieve this, a survey was conducted during the inauguration of the restored building to assess the social and symbolic impacts of the event. Additionally, the study discusses the implications for cultural heritage conservation from the global perspective. The results of this research, which will be discussed in

Section 4, provide valuable insight into the public’s perception of the Notre Dame Cathedral fire, both during the event and following the restoration process. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the symbolic, emotional, social, and political dimensions of the event, as well as the factors that influenced public opinion and the mobilization of support for the cathedral’s recovery. The structure of the work is as follows: First, the definition of the building’s history and some chronology about the incident that took place in it, as well as the methodology to be implemented in this investigation, are included in

Section 2, and the evaluation and discussion of the results are addressed in

Section 3 and

Section 4. Finally, a chapter of conclusions is included (

Section 5), where the main findings of the investigation are established.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the contextual, historical, and methodological foundations of the study. It is divided into three main parts.

Section 2.1 offers a concise overview of the historical significance of the Notre Dame Cathedral, framing its symbolic and cultural relevance.

Section 2.2 provides a detailed chronology of key events, structured into three subsections: the 2019 fire that severely damaged the cathedral (

Section 2.2.1), the subsequent reconstruction process (

Section 2.2.2), and the 2024 reopening event (

Section 2.2.3), which served as the focal context for data collection. Finally,

Section 2.3 outlines the methodology adopted in this research, describing the development, validation, and implementation of the survey used to gather visitors’ perceptions and emotional responses. This includes information about the questionnaire design, the expert validation process, the conditions of the data collection, and the tools used for recording and organizing the responses. Together, these subsections provide a comprehensive understanding of the background, rationale, and research design that support the analysis presented in the following sections.

2.1. History of the Notre Dame Cathedral

The Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, with a history of over 850 years, stands as an iconic monument (

Figure 1). Its architecture, symbolism, and historical events highlight the progression of Gothic design and significant milestones that constitute French history [

46].

Before the construction of the Notre Dame Cathedral, the place already had a deep spiritual and cultural significance. According to historical and archaeological research, this space probably housed a Celtic place of worship associated with spiritual rituals and celebrations.

With the arrival of the Romans and the expansion of the Roman Empire, the area became more urbanized, and its religious function evolved. The Romans integrated local religious practices with their own pantheon. This temple was a part of the development of Lutetia, the Roman city that preceded modern Paris [

47].

With the Christianization of the region in later centuries, the Roman temple was replaced by a Christian church dedicated to Saint Stephen (Saint Étienne). This church, probably built between the 4th and 6th centuries, became the main center of Christian worship on the “Île de la Cité”. In the 12th century, it was decided to replace the church of Saint Stephen with a new cathedral that would reflect the power and faith of the expanding Christianity. Thus, in 1163, construction began on Notre Dame during the reign of Louis VII, with the aim of reflecting the growing power of Paris as a political and spiritual center. Driven by Bishop Maurice de Sully, the cathedral was designed to represent the splendor of Christianity. Notre Dame marked a significant advance in Gothic architecture, with innovations such as flying buttresses, ribbed vaults, and large stained-glass windows that allowed for great illumination. Although the main work was completed in 1345, the cathedral was subject to modifications and additions over centuries [

48].

During the Middle Ages, Notre Dame was an important place of pilgrimage and a center of religious life in Paris. However, in the Renaissance, the cathedral underwent changes due to the decline of the Gothic style in favor of classicism, leading to the modification or removal of some medieval structures [

49].

During the French Revolution, Notre Dame was ransacked, with many of its sculptures and treasures being destroyed or stolen. During this period, the Statue of the Virgin Mary was replaced by the figure of the goddess Liberty, reflecting the revolutionary rejection of the Church [

50].

In the 19th century, the cathedral was in ruins and on the verge of demolition, but the publication of Victor Hugo’s novel

Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) sparked public interest in its restoration. In 1844, the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc led a comprehensive restoration, which included rebuilding the spire (flèche) and the addition of new sculptures and details, such as the iconic gargoyles and chimeras that adorn the cathedral today [

51].

During the 20th century, Notre Dame witnessed key historical events. In 1944, its bells rang out to celebrate the liberation of Paris during World War II. In addition, it became the site of important national ceremonies, such as the funeral of Charles de Gaulle in 1970.

The Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1991, as a part of the ensemble called the “Banks of the Seine in Paris”. This recognition included several monuments and emblematic areas of the city that reflect its historical, cultural, and architectural importance, from the Eiffel Tower to the Louvre Museum, passing through the bridges, historical buildings, and urban landscapes that line the Seine River [

49].

The inclusion of Notre Dame on this list underscored its significance not only as a masterpiece of Gothic architecture but also as a symbol of France’s cultural identity and a testament to the exchange of artistic influences across centuries. The cathedral, with its innovative design, stained-glass windows, and sculptures, and its impact on the development of Gothic art, are considered as a heritage of universal value.

In addition, the Notre Dame Cathedral has been featured in several literary and cinematic works, such as the already mentioned Victor Hugo novel (1831), which revived interest in the cathedral and served as inspiration for numerous adaptations, or Disney’s animated version “

The Hunchback of Notre Dame” (1996). In cinema, notable classics, like “

The Hunchback of Notre Dame” (1939), starring Charles Laughton, have left their mark, while in video games, the cathedral is masterfully recreated in “Assassin’s Creed Unity” (2014). Additionally, productions such as the series “Notre Dame: The Share of Fire” (2022) and documentaries like “Saving Notre Dame” (2020) highlight its cultural significance and the restoration efforts following the 2019 fire. These are just a few examples of the many works inspired by this iconic landmark [

34].

2.2. Chronology of Events

2.2.1. Cathedral Fire

The fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on 15 April 2019 marked a tragic moment in the history of this iconic monument. The chronological overview of the key events related to the fire are presented below [

34,

52,

53].

15 April 2019

18:18 (local time): The fire starts in the cathedral’s attic, near the base of the spire (flèche). Initially, smoke is detected at the top of the building, and the first fire alarms are activated. However, security guards initially do not locate any visible flames.

18:45–18:51: A second fire alarm confirms the seriousness of the situation. Paris firefighters receive the emergency call and quickly move to the scene.

19:00: The flames spread rapidly due to the wooden roof structure, known as “the forest” (la forêt), which dates back to the 13th century. The density and age of the wood cause it to act as fuel, accelerating the spread of the fire.

At some point in this timeline, a group of firefighters entered the cathedral to recover the most precious relics, putting their own lives at risk, including pieces such as the Crown of Thorns, one of the most sacred relics of Christianity, believed to have been brought to Paris in the 13th century by King Louis IX, or the Tunic of Saint Louis, a symbol of the monarch’s devotion, and numerous chalices, crosses, and other liturgical objects of great historical value.

19:57: The cathedral’s spire, rebuilt in the 19th century by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, collapses in front of television cameras and the astonishment of the public present. This moment becomes a symbol of the disaster.

20:00: More than 400 firefighters work intensively to control the fire. Priority is given to protect the two main towers and the works of art housed in the cathedral.

21:45: The fire posed a significant risk of spreading to the towers, potentially causing the entire structure to collapse. However, the firefighters successfully mitigated this threat by cooling the stone and containing the flames in this crucial area.

23:50: After several hours of firefighting, the firefighters manage to partially control the fire. It is confirmed that much of the roof and spire has been destroyed, but the towers, the main façade, and the main stained-glass windows remain standing.

16 April 2019

01:00: The fire is completely extinguished. Authorities confirm that the main structure of the cathedral has been saved, including the towers and exterior walls.

Morning: The damage is assessed, and investigations are launched to determine the cause of the fire, which will later be attributed to an accident related to restoration work being carried out at the cathedral.

During the day: French President Emmanuel Macron visits the site and promises the reconstruction of Notre Dame, with an ambitious goal of completing it in five years.

Indeed, the fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral sent shockwaves through Parisians and people around the world. As the flames consumed the roof and spire of the iconic monument, Parisians spontaneously gathered near the “Île de la Cité”, many of them visibly moved and praying en masse for the cathedral’s salvation [

52].

Groups of people gathered in squares and streets, singing religious hymns, such as Ave Maria, and reciting prayers, as they helplessly watched the fire advance. The bells of other churches in Paris rang out as a symbol of solidarity and mourning, amplifying the emotional impact of the event. Among the crowd, some carried lit candles, while others consoled those who could not hold back their tears. The image of citizens kneeling in the streets, looking toward the burning monument, became a powerful testimony to the spiritual and cultural bond that unites Parisians with Notre Dame.

The event mobilized not only believers but also those who recognize in the cathedral a universal symbol of history and art. On social media, scenes of collective prayer and singing resonated strongly, reflecting the global impact of the disaster. This moment of unity showed how Notre Dame transcends religious and cultural borders, consolidating itself as a shared symbol for humanity.

In the days following the fire, special masses and vigils were organized throughout France as displays of hope and determination to rebuild the cathedral. The tragedy, although devastating, reaffirmed the central role of Notre Dame in the hearts and identities of Parisians [

53].

In less than 48 h, more than 900 million euros were pledged for the restoration of Notre Dame. French families and businesses were among the main donors. Leaders from around the world, including Pope Francis, expressed their dismay and offered support for the reconstruction. Millions of people shared messages of condolence and personal memories of visits to Notre Dame, highlighting its role as a cultural heritage for all of humanity.

However, this outpouring of donations also sparked a debate about social priorities, as some criticized the speed with which funds were mobilized for Notre Dame in the face of other social issues.

2.2.2. Cathedral Reconstruction

Once the fire was extinguished, experts immediately began working on damage analysis and reconstruction planning. President Emmanuel Macron set an ambitious goal of rebuilding the cathedral within five years so that it would be ready before the Paris Olympic Games in 2024 [

54].

Initial efforts focused on securing the structural stability of the cathedral. Although the façade and main towers survived the fire, the roof (nicknamed “the forest” due to its dense wooden framework) and the spire collapsed entirely. The restoration works included a series of structural interventions to consolidate the vaults and reinforce weakened areas, which were crucial for ensuring safety and preventing further deterioration [

35,

55].

Multiple assessments were conducted to detect damage that might compromise the cathedral’s stability. A major concern was the lead contamination resulting from the molten roof, which had released toxic particles into the surrounding environment. Consequently, a lengthy and meticulous cleaning process was required, which included removing lead residues and installing protective measures for workers and the general public [

56].

A multidisciplinary team of architects, restorers, historians, and craftsmen collaborated to ensure that the reconstruction adhered to traditional methods and respected the building’s original design. An international architectural competition was launched in 2019 to reimagine the spire. Some architects proposed modern, innovative designs incorporating contemporary aesthetics, while others favored a faithful reconstruction of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s nineteenth-century design. After extensive debate and public discussion, the French government ultimately decided to restore the spire according to Viollet-le-Duc’s vision to preserve the historical authenticity of the monument [

57,

58].

The restoration of Notre Dame was carried out using traditional construction techniques and authentic materials, such as limestone sourced from the same quarries used during earlier restorations. For the spire, wood identical in species and quality to those of the original wood was selected, preserving the monument’s architectural integrity [

35]. The original roof, which had been constructed from approximately 1300 oak trees during the medieval period, was entirely reconstructed with new oak timbers, following historical carpentry practices. This meticulous approach ensured that the rebuilt roof was both structurally faithful and symbolically representative of the original [

59,

60].

Although many stained-glass windows survived the blaze, a specialized restoration campaign addressed those that had suffered thermal and smoke damage. Among them, the iconic west rose window and other historical stained-glass pieces underwent delicate and precise conservation treatments carried out by expert artisans [

61].

Throughout the reconstruction, French authorities regularly shared updates and visual material with the public, highlighting the project’s symbolic importance as a collective commitment to preserving cultural heritage for future generations.

The academic and scientific community also played an active role, publishing research on the causes of the fire, the material’s degradation, and advanced conservation strategies. Notable examples include laser-scanning and photogrammetry studies, the use of dendrochronology to date and characterize wooden elements, and environmental analyses of post-fire contaminants [

8,

37,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. These contributions not only informed the ongoing restoration but also reinforced the existing best practices in heritage conservation at the international level.

While the current work has made significant progress, such as the reconstruction of the roof, the cleaning of the nave and transept, the installation of new LED lighting, and the restoration of the historical organ, the Notre Dame Cathedral still faces significant challenges to complete its full recovery. Beyond the restoration of the building itself, an ambitious project is underway to revitalize the surrounding environment and seeks to transform the visitor experience and improve the integration of the monument with its urban setting. Highlighted plans include the creation of accessible green spaces, a pedestrian promenade along the River Seine, and a viewing platform that will offer unique views of the iconic building. These works are scheduled for completion in 2027. A comprehensive renovation of Place Jean XXIII, located behind the cathedral, is also planned for completion in 2030.

These combined efforts aim not only to restore Notre Dame to its former splendor but also to reaffirm its status as a global cultural and tourism landmark.

2.2.3. Cathedral Reopening

The reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral after its devastating fire of 2019 took place on 7 December 2024, in a historical and solemn ceremony marking the return of this iconic monument to the life of Paris and the world. This event symbolized not only the material restoration of the cathedral but also France’s resilience in the face of adversity.

The inauguration ceremony for the restored Cathedral began at 7:00 p.m., when the bells of Notre Dame rang, announcing its reopening after more than five years of work. This event was an opportunity to pay tribute to both the history of the cathedral and all those involved in its reconstruction.

The event was attended by 50 heads of state, like the former and future President of the United States, Donald Trump; the British Crown Prince William; and the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky. The ceremony was also attended by political and religious authorities from France, including President Emmanuel Macron, his wife Brigitte Macron, and the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo. In an emotional tribute, a special recognition was given to the firefighters who risked their lives to put out the flames and save a large part of this historical symbol. Their bravery and dedication were praised as an example of commitment to the protection of cultural heritage.

President Macron delivered a speech highlighting the collective effort to restore the cathedral and the cultural and spiritual importance of Notre Dame. The ceremony continued with a religious act presided over by the Archbishop of Paris, Monsignor Laurent Ulrich, who led a liturgy to bless the return of Notre Dame to public life.

A particularly symbolic moment took place when Monsignor Ulrich used a wooden hammer, salvaged from the fire, to knock three times on the door of the cathedral, allowing it to open. This marked the moment when the doors of Notre Dame were reopened to the public following the reconstruction.

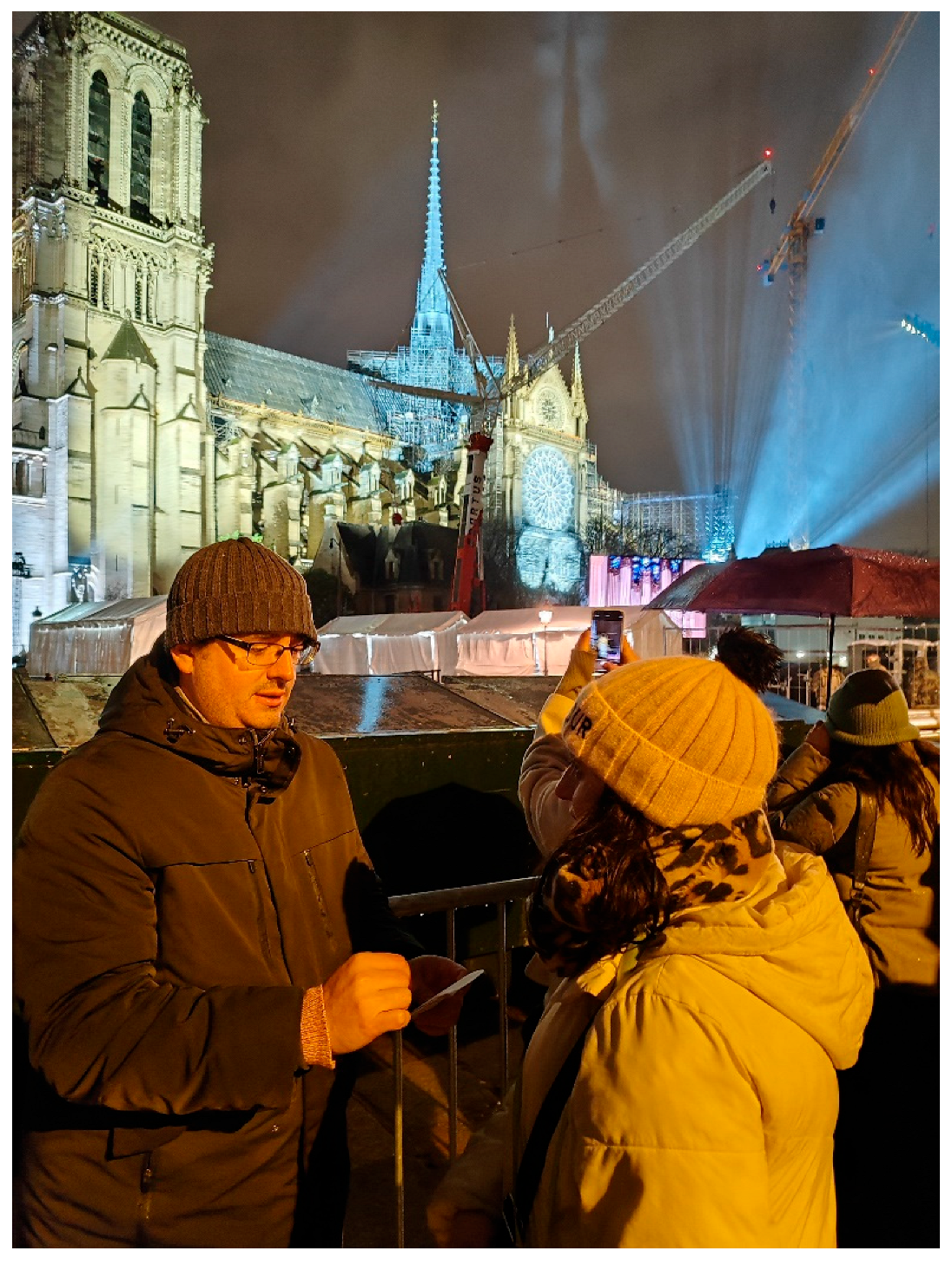

Throughout the day, access to the areas near the cathedral was regulated by a security system that limited entry to a capacity of 40,000 people, distributed in five reception areas, mainly located on the left bank of the Seine, between the Pont de la Tournelle and the Pont-Neuf. Despite the heavy rain that hit the city during the day, approximately 20,000 people gathered around the cathedral to witness this symbolic event. However, the constant rain and cold discouraged many of the attendees, resulting in a lower attendance compared to those of other large-scale events in Paris. The ceremony was followed mainly from the streets by those who could not access the interior due to entry restrictions. The attendees, including both Parisians and tourists, crowded in front of the giant screens installed along the banks of the Seine, from where they could watch the ceremony live.

The wristband system, which granted access to the designated areas, also helped to reduce the concentration of people, as they were distributed in a controlled manner (

Figure 2). However, the wait to access the designated areas was long, and the lack of services, such as the ban on opening nearby bars and restaurants from 3:00 p.m., increased the difficulties for the attendees.

Although the main event of Notre Dame’s reopening took place on 7 December 2024, the first mass open to the public was celebrated on the morning of 8 December, meaning the return of regular religious activity in the cathedral.

On that Sunday, 8 December, coinciding with the feast of the Immaculate Conception, the consecration of the new high altar took place in a solemn inaugural mass at 10:30 a.m., presided over by the Archbishop of Paris (

Figure 3). This event was one of the highlights of the reopening, underlining the spiritual importance of Notre Dame as a place of worship.

Over the upcoming months, further symbolic events will take place to restore the cathedral to its full historical and religious significance (

Figure 4). Among them, the return of the relic of the Crown of Thorns to the cathedral will be a step toward the full recovery of its functionality and symbolism in the cultural and religious landscape of Paris.

2.3. Methodology

The methodology considered in this work is based on the realization of surveys for collecting data about people’s values, thoughts, opinions, and beliefs. These surveys are carried out physically, ensuring the correct understanding of the questions and their corresponding answers. Once collected, the data are subsequently analyzed.

The mentioned survey was carried out in the surroundings of the Notre Dame Cathedral on 7 December 2024, during the inauguration ceremony, and on 8 December 2024, during the first mass open to the public. The exact location of the survey was Zone 3, on the left bank of the Seine River, between the Pont de la Tournelle and the Pont-Neuf (

Figure 5). This event was marked by strict security measures, including an anti-terrorist perimeter on both days, which limited access close to the cathedral and restricted the number of people who could directly participate in the survey. In turn, the bad weather, with constant rain and cold, influenced the willingness of the attendees to participate.

The methodological approach consisted of the use of structured surveys as a tool for gathering quantitative data on visitors’ values, opinions, and emotional responses toward cultural heritage. This technique is widely recognized in heritage and visitor studies for its ability to capture standardized, comparable data in a controlled format [

68,

69]. The use of closed-ended questions, formulated with clear and inclusive language, allowed for efficient participation and reliable analysis. Furthermore, the dual presentation of questions (both orally and in writing) ensured accessibility and minimized misunderstandings, in line with the best practices for inclusive and ethical data collection in public heritage contexts [

70,

71]. Emotional responses were assessed using structured Likert-type items inspired by environmental psychology and heritage interpretation models, which emphasize the affective dimensions of visitor engagement [

41,

72].

The data collection team consisted of four interviewers, who were responsible for administering the surveys to the attendees located around the cathedral. The choice to administer the surveys in English and French responded to the need to cover both the local and international populations, ensuring that participants could clearly understand the questions regardless of their country of origin. The questions were formulated orally to facilitate direct interaction; however, they were also provided in writing, offering an alternative for those who might have difficulty fully understanding them when listening. This strategy ensured greater accuracy in the responses and an inclusive experience for all the respondents.

The preliminary survey was designed during September and October and subsequently validated based on suggestions from various experts, which aimed to enhance its clarity and ensure more accurate responses. It is important to clarify that this validation is a well-established methodological approach in research, aimed at ensuring the appropriateness and accuracy of both the content and the format of the questions. Following the initial design of the questionnaire, a panel of experts was assembled. The selection criteria prioritized the diversity of the professional profiles to provide a multidisciplinary perspective while maintaining a direct and relevant connection to the subject matter of the study. The panel of experts in this case was composed of eight individuals, all of whom are researchers but from different disciplines: art history, civil engineering (2), architecture, education, psychology, and heritage studies (2).

The questionnaire was composed of 12 closed and clearly formulated questions, structured in a logical progression that moved from general demographic information to more specific issues concerning the event. It addressed key areas, such as gender, age, country of origin, and religious affiliation, as well as the participants’ perceptions of the reopening, their awareness of the fire and restoration efforts, and their views on the cultural, historical, and political relevance of the cathedral. The predefined answer choices were designed to simplify participation, allowing respondents to answer quickly and intuitively without requiring elaboration. This format not only enhanced the respondents’ engagement but also streamlined the data collection, making the results easier to organize, quantify, and compare (see

Supplementary Materials).

The interviewers were strategically positioned within Zone 3, ensuring good visibility of the cathedral and the giant screens broadcasting the ceremony so that the respondents could keep up to date with the event while completing the survey (

Figure 6).

Data collection was conducted in person, with interviewers approaching participants and briefly explaining the purpose of the survey. Although the constant rain discouraged some, numerous participants agreed to participate. Responses were recorded digitally via a mobile device, using a document specifically designed to streamline data entry. This method allowed interviewers to collect information more efficiently, without resorting to the use of paper and facilitating the subsequent organization of the data.

All the responses were entered in real time using a mobile document application, which allowed for the agile management of the information. Once the data were collected, they were entered in a centralized database, which was cleaned and organized to ensure its quality and facilitate its statistical analysis. The database was structured so that each response was linked to the corresponding question, allowing for a subsequent orderly and efficient analysis. This organization has been the key to the interpretation of the results and the extraction of relevant conclusions about the participants’ perceptions regarding the reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral.

Considering an expected attendance of approximately 40,000 people, the minimum required number of interviews was calculated at 382, based on a 95% confidence level. However, the actual attendance was significantly lower, with fewer than 20,000 spectators present for the reopening. Despite this, the minimum survey target was upheld, and a total of 418 interviews were ultimately conducted.

It is important to mention that all the data collected as a part of this research were collected in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and were obtained with the informed consent of the participants under the data protection normative. All the participants were informed about the anonymous nature of their participation, why the research was being conducted, how their data would be used, and that under no circumstances would their data be used to identify them.

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it did not involve experiments with humans. The source of the data was the answers to an anonymous survey.

3. Result Evaluation

This section provides a detailed analysis of the results obtained from the survey applied to those attending the reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral, with the aim of better understanding their perceptions of the event, its emotional impact, and the importance of the restoration. The results are structured according to the study’s key objectives: to define the demographic and sociocultural profile of the participants, to assess their perceptions of the reopening and restoration process, to analyze the emotional impact of the event, and to explore their opinions regarding the political and financial aspects related to the restoration. Each subsection begins with a brief summary that highlights the most relevant insights obtained.

3.1. Demographic and Sociocultural Profile of the Respondents

In the first part of the analysis, the profile of the respondents is examined, with the aim of better understanding the demographic and social characteristics of the survey participants. This profile offers valuable insights into the characteristics of the individuals who expressed interest in the reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral, allowing identifying trends and patterns regarding their relationship with the event, the cathedral, and the general cultural heritage.

The demographic profile of the participants shows a balanced gender distribution between men (45%) and women (50%), with a minority representation of other gender identities (2%) or those who preferred not to respond (3%). This balance allows us to assume that perceptions about Notre Dame and its restoration transcend gender.

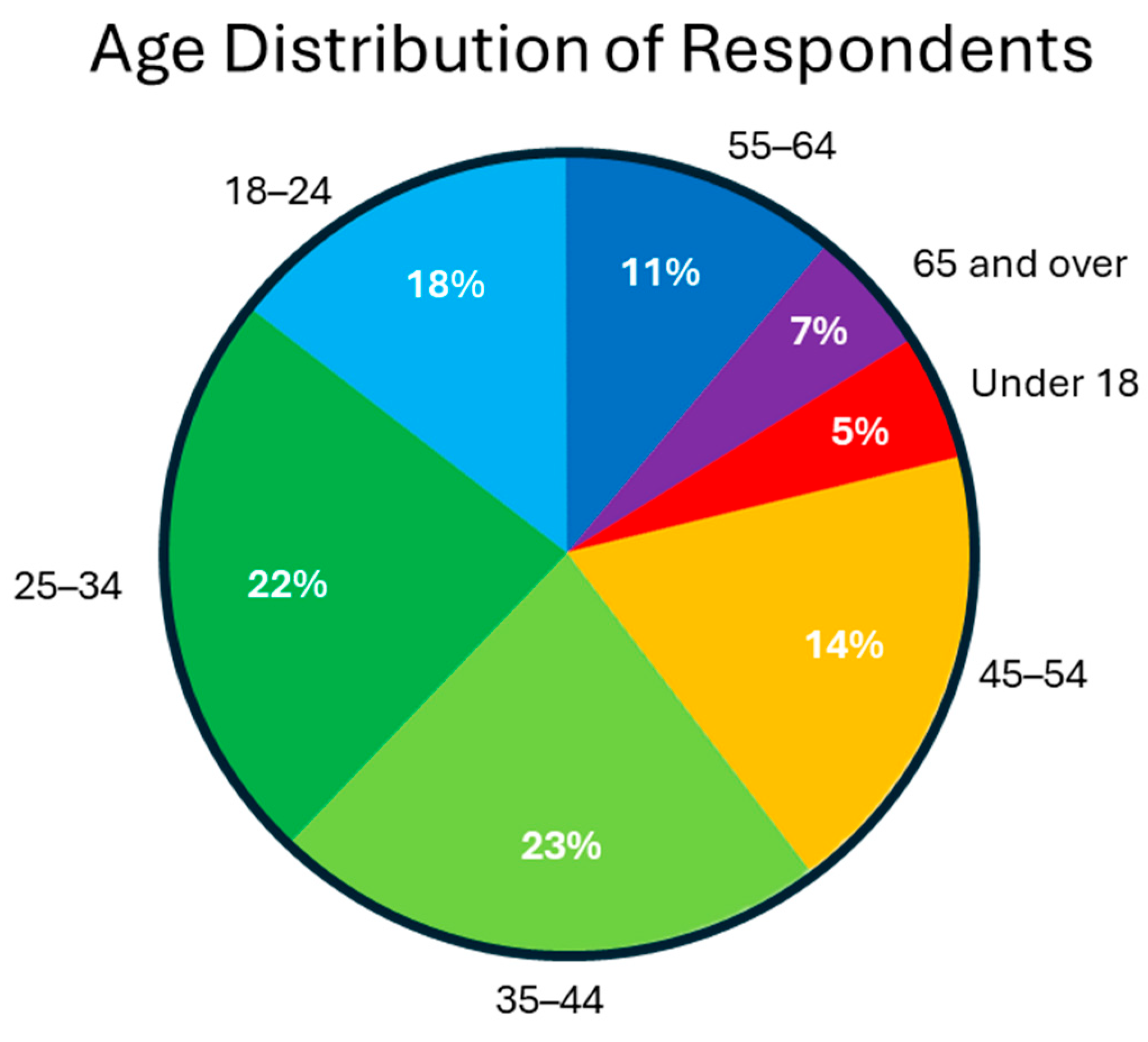

In terms of age, the majority of the respondents are between 18 and 44 years old (63%), suggesting a predominant interest among young and middle-aged adults. Those under 18 years old (5%) and those over 65 years old (7%) represent the least involved groups, which could be related to factors such as a lower emotional connection to the event or a lack of motivation to attend due to the bad weather (

Figure 7).

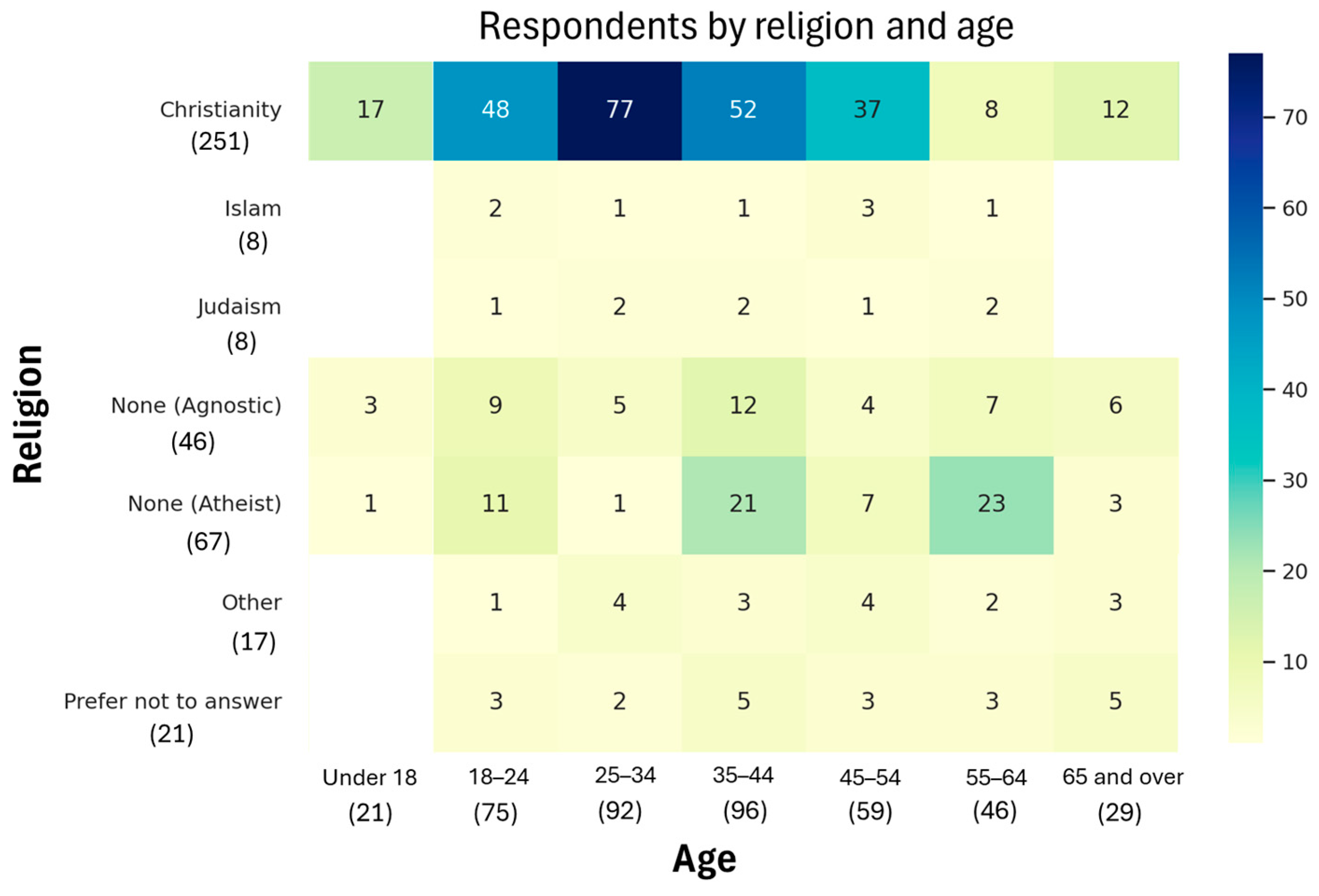

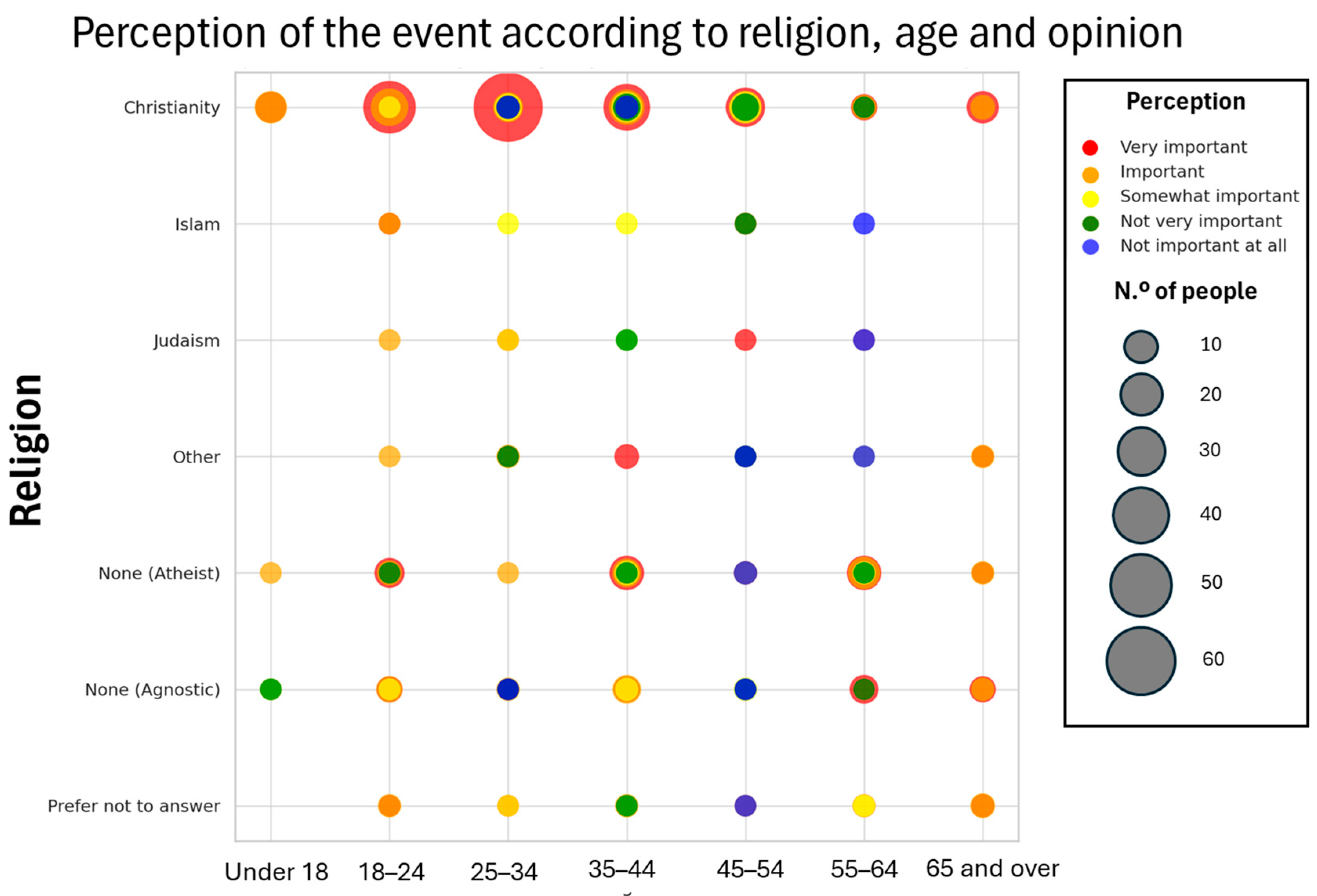

Regarding religion, Christianity predominates (60%), reflecting the relevance of Notre Dame as a symbol of this faith. However, 27% of the respondents identify with other religions or as non-religious (atheist/agnostic). To provide a more rigorous representation of the information, a correlation between the age and religion of the respondents is presented in

Figure 8.

The following paragraphs delve into the analysis of the geographical and sociocultural factors influencing the perception and evaluation of the reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral.

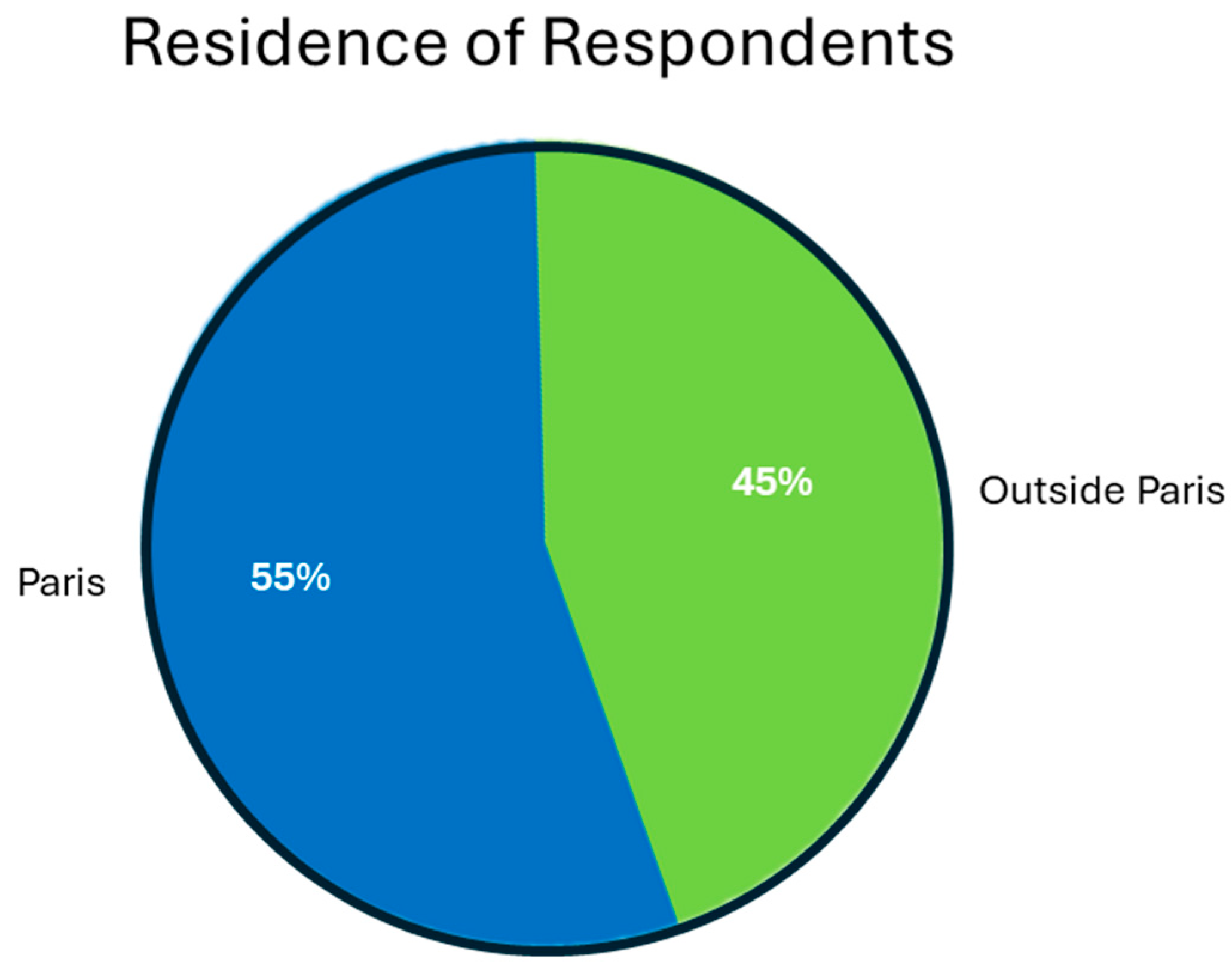

The survey revealed that (for the period of the year when the survey was made) 55% of the respondents resided in Paris, while 45% lived outside the city, highlighting Notre Dame’s global appeal beyond those with a direct connection to Paris (

Figure 9). Additionally, 65% of the contributions originated from within France, with the remaining 35% reflecting a diverse range of regions, primarily other European countries (20%), followed by North America (10%) and Asia (5%). This reinforces the idea of Notre Dame as a heritage site of an international scope.

In summary, the survey revealed a balanced gender distribution and a predominance of young and middle-aged adults. Participants came from a wide range of geographical and cultural backgrounds, with a notable presence of international visitors. While Christianity was the most represented religion, the presence of other beliefs highlights the cathedral’s cross-cultural impact.

3.2. Perceptions of the Reopening and Restoration, Emotional Impact, and Heritage Awareness

An overwhelming 85% consider the restoration and reopening of Notre Dame to be a historical event. This reflects a global consensus on the importance of the cathedral not only as an architectural monument but also as a cultural, spiritual, and touristic symbol of global impact.

When asked about the importance of the reopening, 80% rated it as “very important” or “important”. This result suggests that the respondents perceive the event as a significant achievement, both for its symbolism and for the collective effort behind the restoration following the devastating 2019 fire.

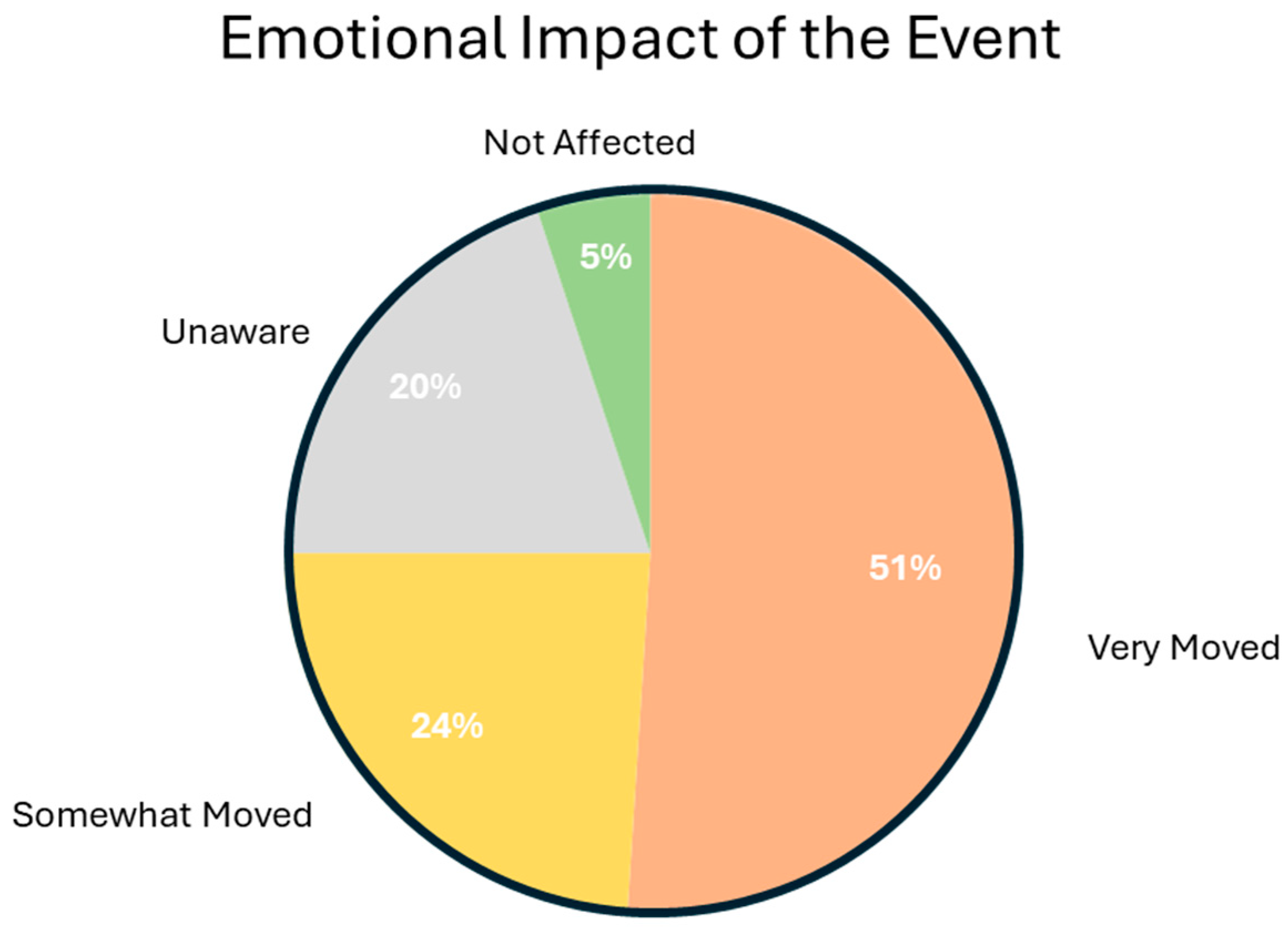

The emotional impacts of the fire and restoration are clear, as 75% of the respondents reported feeling “very moved” or “somewhat moved” by the event and the efforts to restore the monument (

Figure 10). Only 20% mentioned they were not strongly affected, while 5% admitted to being unaware of the event before taking part in the survey. This strong emotional connection underscores the profound significance of Notre Dame for many individuals, transcending geographical and religious boundaries.

Perceptions about the importance of preserving historical heritage changed positively for 60% of the respondents after attending the reopening. This underscores how events of this magnitude can foster greater cultural awareness and a deeper appreciation of historical heritage. Overall, 60% of the respondents aged 18–24 consider historical heritage preservation to be “very important” after attending the reopening of Notre Dame. This percentage decreases as age increases; only 51% of the people aged 25–34 and 55% of the people aged 35–44 share this opinion.

Figure 11 shows (in the form of a bubble chart) the correlation among the religions, ages, and opinions of the participants.

In relation to prior knowledge of Notre Dame, 70% of the respondents were aware of Notre Dame before the fire, although with varying degrees of appreciation, 20% of the respondents visited Notre Dame frequently and felt a strong emotional connection, while 50% were familiar with the cathedral but did not pay much attention to it. On the other hand, 25% indicated that their interest arose as a result of the fire, suggesting that the tragedy attracted new audiences to the cathedral. Only 5% were completely unaware of the existence of the monument before the event. Interestingly, most of the people within this 5% are under 24 years of age.

In summary, most respondents considered the reopening to be a historical event and viewed it as highly important for cultural and historical reasons. Prior knowledge of the cathedral influenced their perceptions, though the fire attracted new audiences and increased awareness of the monument’s significance.

The restoration evoked strong emotional responses in the majority of the participants, with many expressing a greater awareness of the importance of heritage conservation after the event. Emotional engagement varied across age groups and belief systems.

3.3. Perceptions of the Political and Financial Aspects

Finally, other political and social factors that influence the respondents’ perceptions and opinions on the restoration of the Notre Dame Cathedral are analyzed, considering the political context in which the restoration process took place and the social implications that arose from the mobilization of funds and resources for this purpose.

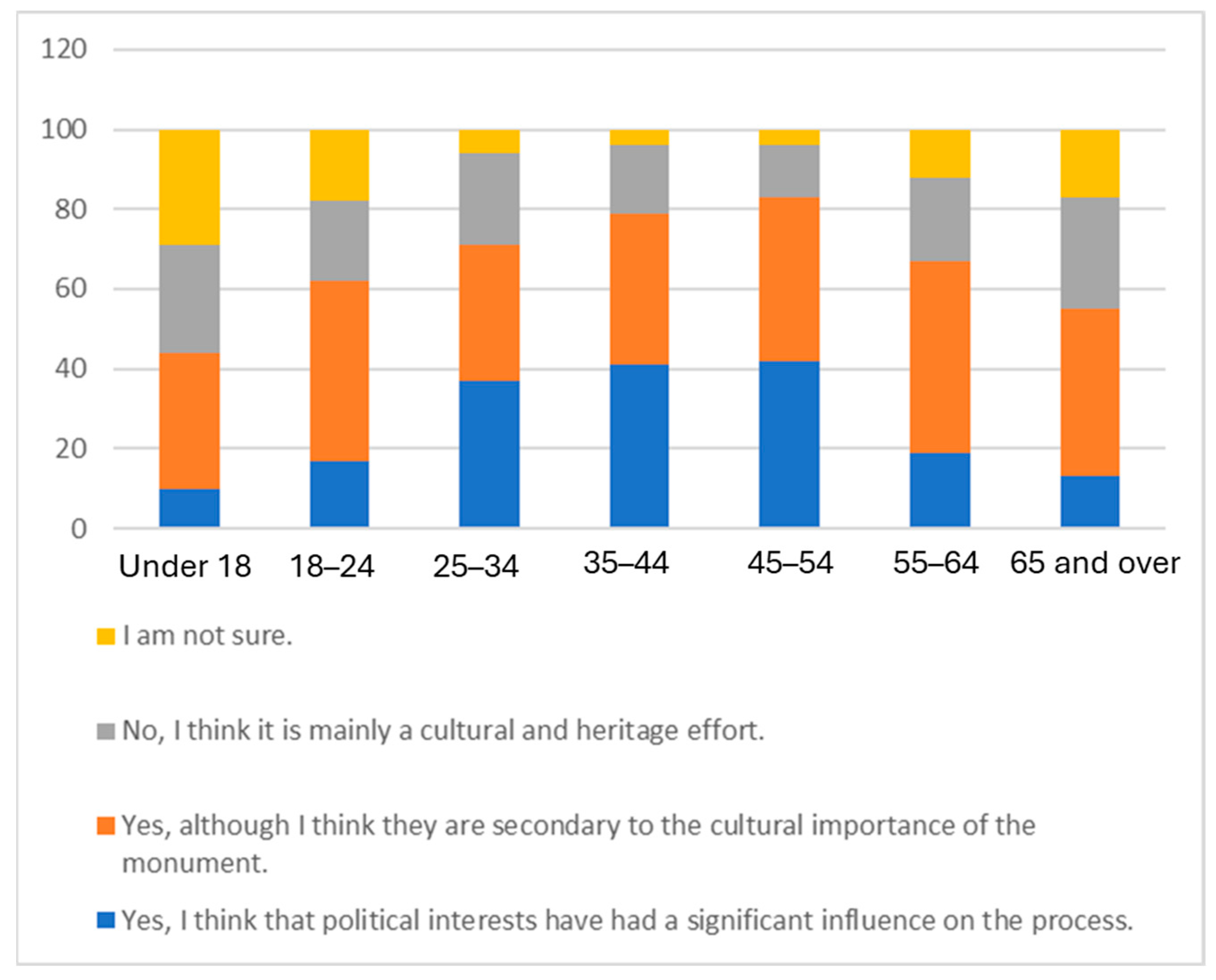

In this sense, 70% of the respondents believe that political interests are involved in the restoration of Notre Dame, though with varying perspectives. Of this group, 40% view these interests as secondary to the cultural value, while 30% believe they have had a significant impact. Only 20% perceive the effort as exclusively cultural and heritage, which indicates a certain level of skepticism about the motives behind the financing and management of the project.

A higher percentage of people between 25 and 44 years old (30%) consider that political interests have had a significant influence on the restoration of Notre Dame. On the other hand, people under 25 years old and over 45 are more divided: 40% of the people between 18 and 24 years old think that political interests are secondary (

Figure 12).

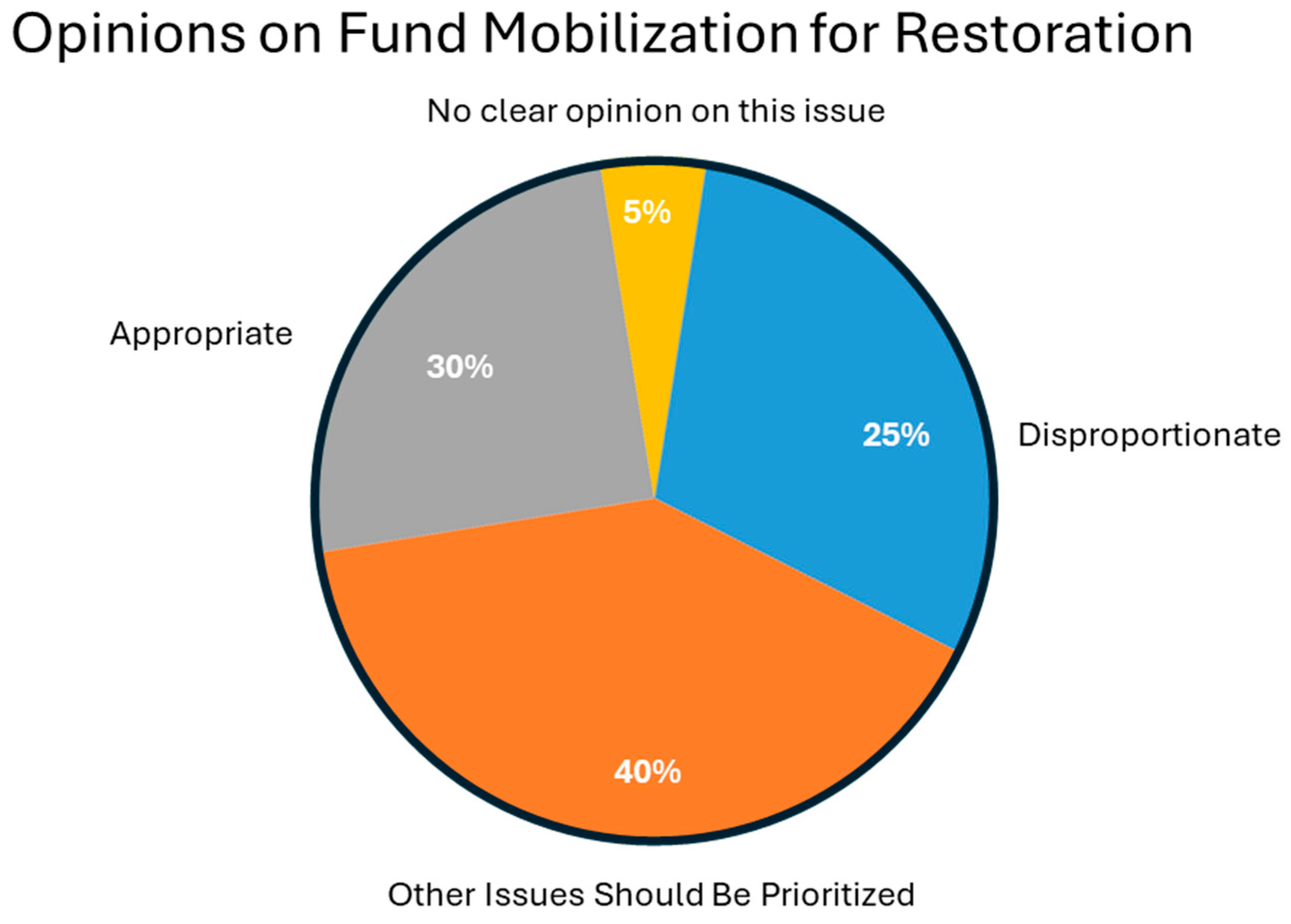

On the other hand, the mobilization of funds for the restoration generated divided opinions: 30% consider it as appropriate due to the cultural importance of Notre Dame. Overall, 40% believe that although it is understandable, other urgent social problems should be prioritized, and 25% perceive it as disproportionate compared to other social needs (

Figure 13).

The individuals who identify as atheists (16%) or agnostics (11%) appear to have a more critical view of the speed at which funds were mobilized for the restoration of Notre Dame. Overall, 40% of the atheists think that other social problems should have been prioritized. In contrast, religious people (mainly Christians) tend to justify the speed of the restoration as being appropriate due to the cultural importance of Notre Dame, with 33% of the Christians opting for the option “It is appropriate since Notre Dame is a cultural symbol of great importance.”

In summary, while most respondents recognized the cultural value of the restoration, many also perceived the presence of political interests. Opinions on the rapid mobilization of funds were divided, with some prioritizing heritage and others pointing to social needs. Belief systems influenced these views.

In the following section, a more in-depth analysis and discussion of these results is presented.

4. Discussion

The reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral has been an event of great significance not only for Paris but also globally, as reflected by the high turnout and emotional responses. This fact can be clearly observed based on the number of global media outlets that followed the event. This analysis reveals that although the cathedral is a symbol deeply linked to Christianity and the city of Paris, its impact extends beyond these spheres, reaching a diverse international audience represented by individuals of different ages, religions, and nationalities.

Regarding the demographic profile of the participants, it shows a predominantly young and adult audience (65% between 18 and 44 years old), suggesting that interest in the restoration of Notre Dame is not limited to those who might have a stronger religious or historical connection to the monument but also attracts a generation that values cultural heritage as a form of collective identity. This profile also highlights a higher participation rate of foreign people (45%), which shows that the cultural heritage of Notre Dame does not belong only to Parisians but is perceived as a common and universal asset. This fact is reinforced by observing that most respondents, regardless of their age, were familiar with Notre Dame in some way. Only 5% of the participants claimed to have no knowledge of this emblematic monument. This percentage mostly corresponds to people under 24 years of age, suggesting that younger generations may have a lower connection to or recognition of relevant historical monuments such as Notre Dame compared to older generations, who show a higher level of knowledge of or appreciation for cultural heritage.

In relation to the geographical diversity, the large representation of people outside of France underlines the global character of Notre Dame as a world heritage site. This aspect is also reflected in the responses about the cultural significance of the event, with 85% of the respondents recognizing the restoration as a historical milestone. In this sense, the perception of Notre Dame transcends the local symbolism and becomes a global symbol of resistance, resilience, and unity in the face of tragedy. This feeling of global connection is reinforced by the high percentage of individuals (75%) who expressed having been emotionally moved by the fire and the subsequent restoration, revealing the symbolic charge of the event beyond its immediate impact. It is interesting to note that young people, having experienced the fire and the reopening of the monument, reflect a greater interest and commitment to heritage conservation, possibly influenced by greater cultural awareness or participation in activities related to history and heritage.

Additionally, the analysis of the respondents’ attitudes toward the conservation of historical heritage also shows a significant change in the perceptions of the participants. Overall, 60% of the respondents expressed greater awareness of the importance of preserving these monuments after the reopening, reflecting a possible positive effect of the restoration on the valorization of cultural heritage. This phenomenon suggests that beyond admiration for the cathedral itself, the event has acted as a catalyst for promoting a more responsible and respectful attitude toward heritage assets.

Regarding the effects of these kinds of incidents, historically, the destruction of heritage has had devastating consequences for cultures and societies. From the practices of the Roman Empire, which dismantled the structures of conquered cultures to impose its order, to contemporary conflicts that erase religious and linguistic monuments, the loss of heritage has been a tool of domination and the erosion of collective identities. More recent examples, such as the devastation of cities during the world wars or the destruction of cultural assets in modern conflicts, illustrate how these losses deeply affect communities. Catastrophes, poor heritage management or the lack of funds for its conservation, acts of vandalism, or other devastating actions have also caused the loss of many heritage assets throughout history, with major social impacts. For this reason, initiatives such as the World Heritage List or the Red List of Heritage of Hispania Nostra take on crucial relevance [

27,

28]. By making assets in danger of disappearing visible, the aims are not only to preserve them but also to reaffirm the identities of communities and their rights to maintain and transmit their legacies to future generations. The protection of cultural heritage must be understood as a form of resistance against oblivion and the loss of identity. Furthermore, collaboration among public administrations, the private sector, and civil society is essential to carry out this task. The protection of heritage cannot be the sole responsibility of a single institution or group but must be a joint and collective effort to ensure that these assets, which constitute our shared memory, do not disappear and continue to be a source of pride and reflection for future generations.

Focusing now on the restoration of assets, in the case of Notre Dame, it has been a monumental effort in cultural and architectural terms and has been marked by political tensions. In this sense, 70% of the respondents perceived that political interests influenced the restoration process. At a time of tension for French President Emmanuel Macron, facing internal facts, such as the “yellow vest” [

73] protests and opposition to his reforms, the restoration of Notre Dame was used as an opportunity to project unity and leadership. Likewise, the involvement of big businessmen close to the government in the fundraising campaign raised criticism about the political use of the event. On the other hand, international figures, such as Volodymyr Zelensky, also took advantage of the symbolism of the restoration to reinforce messages of global solidarity through their presence at the event. In this context, it is interesting to note how middle-aged people (25–44) have a greater perception or distrust of the role of political interests in the restoration, while young individuals have a more flexible view or are less concerned about political factors.

Furthermore, the debate on the mobilization of funds also highlights the tensions inherent in the distribution of resources in contemporary societies. While 30% consider the allocation of funds for the restoration to be appropriate (given the cultural significance of Notre Dame), 40% believe that other more urgent social problems should be prioritized. This disagreement reflects a questioning of social priorities in times of crisis, where some sectors believe that investments in culture can be seen as disproportionate to immediate needs, such as poverty, education, or health. It is interesting to note how a fairly high percentage of religious people surveyed (mainly Christians) tend to justify the speed of the restoration as being appropriate due to the cultural significance of Notre Dame. This could indicate that religious beliefs are related to a greater cultural justification for the mobilization of resources, while people without a religious affiliation could question the fairness in the distribution of funds. These results reflect a latent debate on the priorities of modern societies and the speed with which resources are allocated to cultural projects versus social causes. However, the fact that most did not openly criticize the mobilization shows a widespread recognition of the relevance of Notre Dame as a cultural symbol.

As for the restoration of Notre Dame, it has represented not only an architectural endeavor but also a model for the integration of traditional techniques and technological advances. Thousands of craftsmen, restorers, and experts from around the world collaborated on a project that combined historical construction methods with cutting-edge technologies to ensure the long-term stability and safety of the monument. This underlines the importance of investing in innovative tools, such as 3D modeling, sensors for structural monitoring, and digital documentation for the preservation of cultural heritage [

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83].

Figure 14 graphically represents how the Notre Dame Cathedral functions as a multifaceted global symbol, structured into three main dimensions: identity, myth, and icon. Each dimension is broken down into key elements that reflect its cultural, spiritual, artistic, and historical impacts, both nationally and internationally.

There is no doubt that this unfortunate event has highlighted the profound symbolism that this monument represents, not only for France but also for European and global cultural identity. Beyond its impressive architecture and religious relevance, Notre Dame is a landmark that transcends borders, uniting people from different cultures with the same admiration and respect for its history. Its post-fire restoration has been not only an act of physical reconstruction but also a symbol of collective resilience, demonstrating that cultural heritage is a link that connects generations, nations, and peoples.

5. Conclusions

The reopening of the Notre Dame Cathedral represents a momentous milestone not only in the history of France but also in the global awareness of the importance of cultural heritage. The restoration of this iconic monument has revitalized its role as an architectural and spiritual symbol, also constituting a new dimension as an emblem of resilience, restoration, and hope. This process has not only restored the cathedral to its physical splendor but also rekindled a feeling of unity around the preservation of historical and cultural memories, projecting it as a compelling case of resilient heritage in the face of adversity.

The impact of this event has been amplified by the media, which has given global visibility to the collective effort behind the restoration. This dissemination has contributed to strengthening the recognition of Notre Dame as a universal symbol, transcending its original function as a place of worship to become a bridge connecting generations, cultures, and nations. The cathedral has reaffirmed its ability to inspire, mobilize resources, and generate dialog around the need to protect our common heritage in the face of the challenges of time and adversity.

However, this renaissance has also brought to light the complexities inherent in heritage management in a globalized world. While the restoration process has raised awareness of the importance of preserving our historical legacy, it has also generated intense political and social debates. These questions range from priorities in resource allocation to tensions between modernity and tradition, as well as the expectations of different sectors of society regarding how a monument of such magnitude should be interpreted and preserved.

In this context, the reopening of Notre Dame can be understood as a paradigmatic example of the duality surrounding major restoration projects. On the one hand, these initiatives highlight the ability to inspire unity and resilience, and on the other, they expose the ethical, financial, and social challenges that arise around them. This event invites a reflection of how contemporary societies value and prioritize their cultural heritage in an environment characterized by increasing social and economic demands.

Ultimately, Notre Dame stands not only as a restored monument but also as a living reminder of the human capacity to face adversity, rebuild what has been lost, and project into the future without forgetting the original roots. Beyond its walls, its recent history resonates as a call to collective action to protect and value the legacy that connects us to our past and that defines, to a large extent, our cultural and social identities.

The Notre Dame Cathedral is a symbol of the collective resilience that has transcended time, uniting generations and cultures and standing as an emblematic testament to humanity’s resilience in the face of adversity. Since Victor Hugo published his famous novel “Notre Dame de Paris” in 1831, the cathedral not only has been rescued from physical neglect but also has inspired a new artistic and heritage appreciation. Centuries later, the devastating fire of 2019 reawakened a deep sense of community and global solidarity, prompting a joint effort for its restoration. Thus, Notre Dame represents not only an architectural and literary icon but also the spirit of unity and shared strength in the face of adversity. The fire of April 2019 represented not only an incalculable material loss but also a symbolic wound in the collective memory, both for French citizens and the international community. However, the immediate reaction of solidarity, the commitment to the cathedral’s reconstruction, and the joint efforts of experts, institutions, and citizens reflect the deep emotional and cultural connections that societies establish with their heritage.

The restoration of Notre Dame transcends architectural and technical expertise; it stands foremost as a profound act of cultural resilience and identity reaffirmation. Rebuilding the cathedral underscores the vital roles of cultural heritage not merely as a remnant of the past but also as a shared asset that weaves together the history, spirituality, and collective memory of generations. This process also invites reflection on the need to strengthen the collective consciousness and shared responsibility for heritage protection. Notre Dame does not belong exclusively to one city or one nation; it is a part of the global imagination, a part of history shared by humanity. Its restoration, therefore, represents an opportunity to rethink the links between memory, conservation, and active citizenship, as well as to integrate new technologies, risk prevention strategies, and sustainable approaches that ensure its preservation for the future. Ultimately, Notre Dame symbolizes how, even in the face of destruction, heritage can be reborn with greater strength, consolidating itself as a fundamental element for social cohesion, intercultural dialog, and the construction of a common identity.

In parallel with this symbolic dimension, the aesthetic impact of the restoration is particularly evident in the renewed interior of the cathedral, where careful efforts were made to preserve the historical appearance while introducing subtle but meaningful improvements. Except for the spire (which has been rebuilt using fire-resistant materials to prevent incidents like the 2019 fire), the restoration maintained fidelity to the original architectural lines and stylistic coherence. Notably, the once-blackened walls have been meticulously cleaned, restoring their original white stone appearance, and the stained-glass windows, previously obscured by dirt and aging, now allow significantly more light to enter. As a result, the interior of Notre Dame has been transformed into a brighter, more luminous space that enhances both its spiritual atmosphere and architectural beauty without compromising its historical integrity.

In addition to the above, the results of this research highlight the need to establish different strategies to promote heritage protection. Identifying potential vulnerabilities and how they might affect heritage would be the first step in establishing these strategies, followed by defining prevention and mitigation actions, such as reinforcing structures, and digitizing heritage with activities such as generating 3D models or high-resolution photographs that allow for restoration if necessary. Establishing emergency plans that allow for rapid responses in the event of both natural and human-made disasters should also be a priority for heritage conservation. Public communication about heritage elements is another important asset in heritage protection. If properly designed, it fosters empathy, shared memory, and collective responsibility, powerful tools for mobilizing citizen support and participation.