Aviation Heritage in the Urban Landscape—Concept and Examples from Berlin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aviation Heritage—State-of-the-Art

3. Concept, Materials and Research Methods

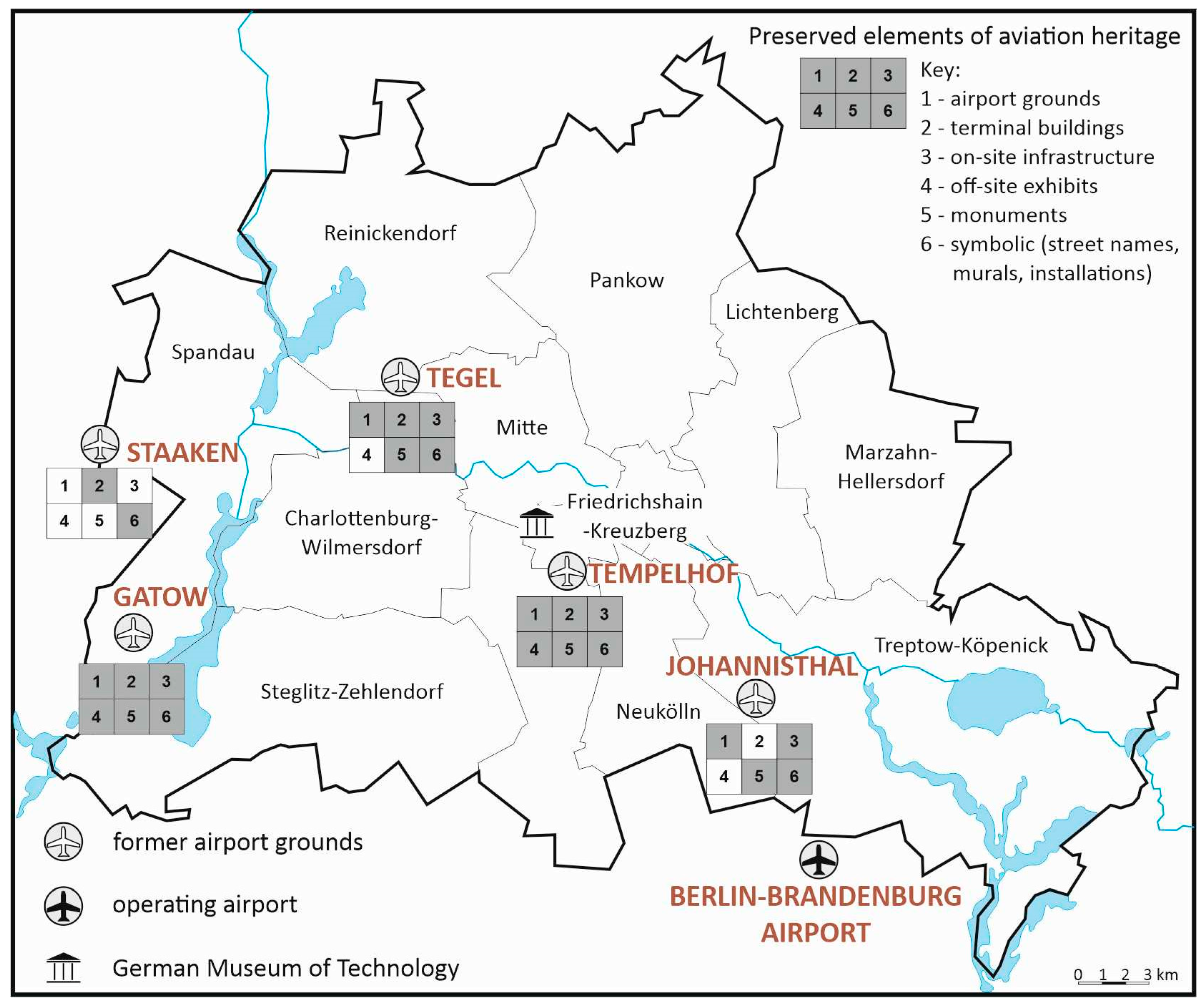

- Former airfield left as an open ground—maintaining (entirely or partially) an open space, although the use of this space may be variable;

- Airport buildings—mainly airport terminal buildings, air traffic control towers, and airport hotels that have been preserved and repurposed for new functions;

- Preserved aeronautical infrastructure (on-site)—includes valuable aviation infrastructure, such as innovative structures recognized as technical heritage and legally protected, as well as remnants of runways, taxiways and airport aprons;

- Aircraft and off-site exhibits—relocated from other locations (including other airports or museums) and displayed as either solitary objects or collections in museums;

- Monuments and symbols commemorating aviation history;

- Preservation of place identity (cultural and toponymic preservation of aviation history)—encompassing names of buildings, places, and streets, murals and street art that refer to the aviation traditions of the site, and aviation-themed playgrounds for children;

- Ground plan of a former airport area preserved in the urban fabric (this category has not been identified in Berlin).

4. Results

4.1. Complicated History of Aviation in Berlin

4.1.1. Johannisthal—The Birthplace of Aviation

4.1.2. Staaken—The Airship Airport

4.1.3. Tempelhof—The “Mother of All Airports”

4.1.4. Gatow—A British Legacy

4.1.5. Tegel Airport—A Symbol of Modernity

4.2. Tangible and Intagible Aviation Heritage of Berlin and How It Is Protected?

4.2.1. Former Airfield Left as Open Ground

4.2.2. Airport Buildings—Terminals and Control Towers

4.2.3. Preserved Aeronautical Infrastructure (On-Site)

4.2.4. Aircrafts and Off-Site Exhibits

4.2.5. Monuments and Symbols Commemorating Aviation History

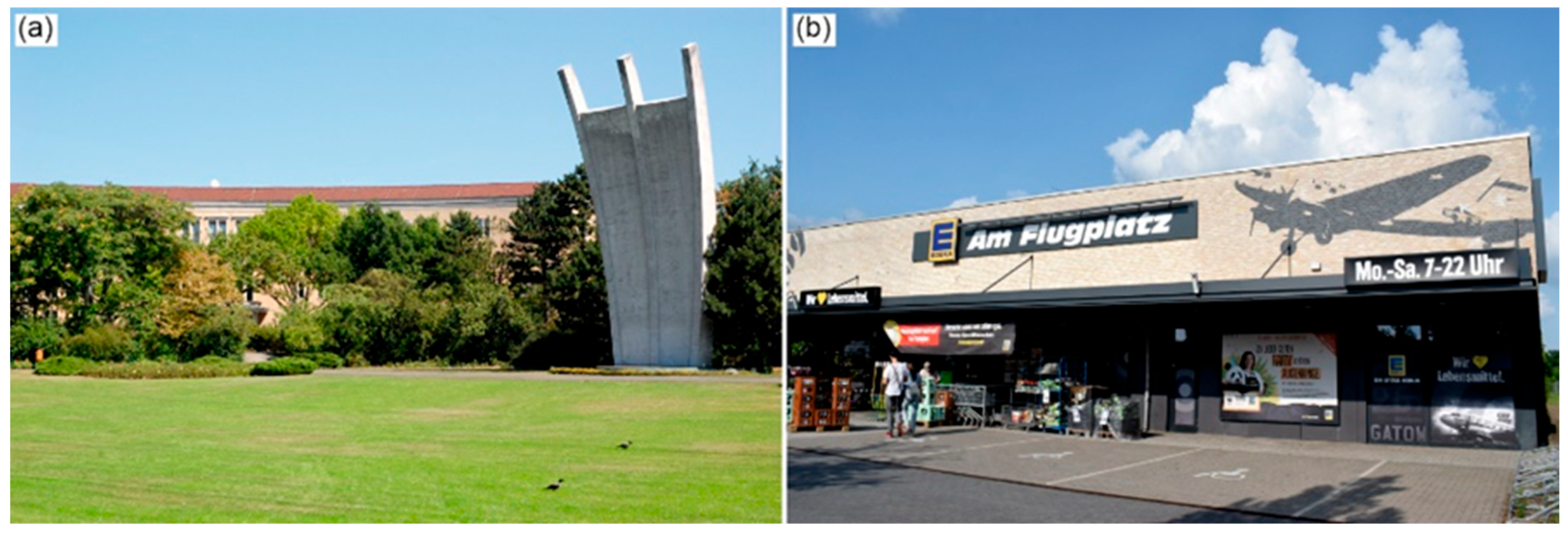

4.2.6. Cultural and Toponymic Preservation of Aviation Identity

4.2.7. Aviation Heritage at Former Airports of Berlin—A Summary

5. Discussion

5.1. Relevance of Aviation Heritage for the Local Population

5.2. Aviation Heritage as a Tourist Attraction

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simons, D.; Withington, T. The History of Flight; Parragon: Bath, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moyle, T. Art Deco Airports. Dream Designs of the 1920s & 1930s; New Holland Publishers Pty Ltd.: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Olipra, Ł. Changing Patterns and Social Determinants of Air Travel. In Air Transportation Industry; Majewski, R., Stasiczak, K., Huderek-Glapska, S., Olipra, Ł., Augustyniak, W., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2024; pp. 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijet-Migoń, E. Former Airports in the Landscape of European Cities. Diss. Cult. Landsc. Comm. 2019, 41, 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Douet, J. (Ed.) Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Carnegie Publishing: Lancaster, UK, 2012; p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- Wayland, K.A. World War II Warplanes as Cultural Heritage. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, T.; Harrison, A.; Brockwell, S. Materialities, Mobilities and Multiple Modernities: Heritage of the Air in Australia. Hist. Environ. 2020, 32, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Favargiotti, S. Airports On-Hold: Towards Resilience Infrastructure; ACC Art Books: Woodbridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.A.; Llurdés i Coit, J. Mines and Quarries: Industrial Heritage Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, T.; Myga-Piątek, U.; Solon, J. Typologia aktualnych krajobrazów Polski. Przegl. Geogr. 2015, 87, 377–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.; Maland, A.; Newchurch, J. Aboriginal Culture Meets Aviation: Kaurna Heritage and RAAF Base Edinburgh. Hist. Environ. 2020, 32, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dümpelmann, S.; Waldheim, C. Airport Landscape: Urban Ecologies in the Aerial Age; Harvard Design Studies: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Alfrey, J.; Putnam, T. The Industrial Heritage: Managing Resources and Uses; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Delang, C.O.; Ng, S.W. Urban Regeneration and Heritage Preservation with Public Participation: The Case of the Kai Tak Runway in Hong Kong. Open Geogr. J. 2009, 2, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favargiotti, S.; Yang, J. (Eds.) Airfield Manual. Field Guide to the Transformation on Abandoned Airports; Harvard University Graduate School of Design: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- Favargiotti, S. Renewed Landscapes: Obsolete Airfields as Landscape Reserves for Adaptive Reuse. J. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 13, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuta, A.F. Abandoned Heritage—The First European Airports. Tech. Trans. Archit. Urban Plan. 2019, 3, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, K.C.; Tamvakis, D.; Samiotakis, A.; Moropoulou, A. Re-use of Built Environment—Strategic Planning of Sampling Locations for the Environmental Impact Assessment of Former Airports: The Use-Case of the Former Hellenikon Airport in Athens, Greece. Dev. Built Environ. 2022, 10, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Duan, W. Mixed-Methods Approach to Land Use Renewal Strategies in and around Abandoned Airports: The Case of Beijing Nanyuan Airport. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. “I Can Still Remember the Roar of the Engines”: Memory, Attachment and Archaeology of the Rose Bay Flying Boat Base and the Fairy Firefly VX381 Wreck Site. Hist. Environ. 2020, 32, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cardow, A.; Emerson, A. Tourist Attraction? Or Reverence—The Royal New Zealand Air Force Museum A Case Study of the Tension between Intent and Presentation. Res. Work. Pap. Ser. 2007, 2, 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zengin, B.; Zeren, U. Can Aviation Enthusiasm Claim a Spot in Special Interest Tourism? In New Trends in Tourism; Gökçe, A., Ed.; Özgür Publications: Ankara, Turkey, 2023; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorontzy, U.; Schlütter, B. Lilienthals Vermächtnis. Lilienthal’s Legacy; Technomedia: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eiselin, S.; Frommberg, L.; Gutzmer, A. The Art of the Airport. The World’s Most Beautiful Terminals; Frances Lincoln: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nachama, A. (Ed.) A Broad Field: Tempelhof Airport and Its History; Stiftung Topographie des Terrors: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asisi, E.; Schlüter, O. Ready for Take Off. 100 Jahre Flughafen Tempelhof; Tempelhof Projekt GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2022; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Butter, A.; Dittrich, E.; Engler, H.; Popiołek-Roßkamp, M. Der Flughafen Tempelhof. Eine Stadtgeschichte; Lukas: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Suwala, L.; Kitzmann, R.; Kulke, E. Berlin’s Manifold Strategies Towards Commercial and Industrial Spaces: The Different Cases of Zukunftsorte. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschel, E.H.; Prem, H.; Madelung, G. Aeronautical Research in Germany: From Lilienthal Until Today; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pearman, H. Airports: A Century of Architecture; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roskamm, N.; Karge, T. Grand Opening Tempelhofer Feld; Universitätsverlag der Technischen Universität: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Southerland, J.; Canwell, D. Berlin Airlift: The Salvation of a City; Pelican Publishing Company: Gretna, LA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.G. The Complete History of Aviation; DK, Penguin Random House: London, UK, 2022; p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Best, P.B.; Gerlof, A. Gatow Airfield; Kai Homilius: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zadrazilova, D. Berlin Tempelhof: From Heritage Site to Creative Hub? Ex Novo J. Archaeol. 2020, 5, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A. Naked Airport: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Revolutionary Structure; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Roskamm, N. 4,000,000 m2 of Public Space: The Berlin “Tempelhofer Feld” and a Short Walk with Lefebvre and Laclau. In Public Space and Challenges of Urban Transformation in Europe; Madanipour, A., Knierbein, S., Degros, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- ERIH—European Route of Industrial Heritage. Adlershof Aerodynamic Park. Available online: https://www.erih.net/i-want-to-go-there/site/adlershof-aerodynamic-park (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Mroczkowski, K.; Wierzbicki, P.; Wielgus, K.; Drożdż, M.; Krzaczyński, T.; Wachowicz, I. Muzeum Lotnictwa Polskiego w Krakowie—60 Lat Tradycji; Muzeum Lotnictwa Polskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2023; p. 587. [Google Scholar]

- Adey, P. Airports and Air-Mindedness: Spacing, Timing and Using the Liverpool Airport, 1929–1939. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2006, 7, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adey, P. ‘May I Have Your Attention’: Airport Geographies of Spectatorship, Position, and (Im)Mobility. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2007, 25, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adey, P.; Budd, L.; Hubbard, P. Flying Lessons: Exploring the Social and Cultural Geographies of Global Air Travel. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempelhof Project GmbH. Flughafen Tempelhof aus den Archiven 1990–2023; Tempelhof Project GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Thierfelder, H.; Kabisch, N. Viewpoint Berlin: Strategic Urban Development in Berlin—Challenges for Future Urban Green Space Development. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. Growing Biodiverse Urban Futures: Renaturalization and Rewilding as Strategies to Strengthen Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempelhof Projekt GmbH. Available online: https://www.thf-berlin.de (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Pollalis, S.; Kouveli, A.; Kyriakopoulos; Papagianni, A.; Papapetrou, N.; Sagia, V.; Tritkaki, N. The Urban Development of Former Athens Airport. In Proceedings of the AESOP-ACSP Joint Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nikoloudis, C.; Strantzlli, E.; Aravossis, K. On the Comparative Financial and Risk Analysis of Urban Development Projects: The Case of Athens’ Hellinikon Airport. Prog. Int. Ecol. 2017, 11, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunbridge, J.E.; Ashworth, G.J. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Visit Berlin. Available online: www.visitberlin.de (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Tegel Projekt GmbH. Available online: https://tegelprojekt.de (accessed on 31 March 2025).

| Airport Name | Years of Operation | Location | Function/Specialization of the Airport | Current Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johannisthal | 1909–1952/1995 | Adlershof district, post-WWII in the Soviet zone | Early aviation—training and testing airport; post-WWII used by the Soviet Army and the East German Army | 65 ha of green areas, approx. 25 ha of Humboldt University campus and science/technology park |

| Staaken | 1916–1948 | Spandau district, post-WWII near the border of East Germany and West Berlin | Airship airport, later training and communication airport | Industrial and warehouse area, part of the area used as a solar panel field |

| Tempelhof | 1923–2008 | Tempelhof-Schöneberg district, post-WWII in the American zone | Civilian airport—one of the oldest airports in Europe, temporarily used as a military airport | Recreational areas |

| Gatow | 1935–1995 | Spandau district, post-WWII in the British zone | Military airport, used by Luftwaffe until 1945, then by the RAF | Military aviation museum, part of the area converted into a residential estate |

| Tegel | 1948/1974–8 November 2020 | Reinickendorf district, post-WWII in the French zone | Initially a military airport, from 1960 a passenger airport, in 1974 became Berlin’s main passenger airport | Adaptation work underway to implement the Tegel Project |

| Category | Johannisthal | Staaken | Tempelhof | Gatow | Tegel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Former airfield left as open ground | Partly preserved—Nature Reserve (26 ha) and Landscape Protection Area (39 ha) | Not preserved—area built over and partially occupied by a solar farm | Fully preserved—Tempelhofer Feld (386 ha) maintained as a public space | Partially preserved, repurposed as an open-air aviation exhibition | Planned partial preservation—transformation into landscape park (approx. 190 ha) |

| Terminal building, control tower | No remaining structures | Control tower preserved | Terminal building and control tower preserved | Control tower preserved | Terminal building and control tower preserved |

| On-site infrastructure and equipment | Hangars, Large wind tunnel, Spin Tower, sound absorbing engine test stand | No remaining infrastructure | Runways and apron | Key infrastructure elements retained—airfield still capable of supporting aviation-related functions | Preservation of historically significant hangars and pyramid-shaped engine test facility as heritage monuments |

| Aircrafts and off-site exhibits | No aircraft exhibits | No aircraft exhibits | Few aircraft of historical significance | Exhibits relocated from other places (mainly from the Bundeswehr Museum in Appen) | No aircraft display planned |

| Monuments and symbols commemorating aviation history | Memorial plaque, information panels | No commemorative elements | Informational panels on aviation history, visitor information centre, information panels, visitor centre | Exhibition on the history of the airport in a former hangar, memorial, mural on a local supermarket | Planned historical exhibition focusing on the airport’s legacy |

| Cultural and toponymic preservation of aviation identity | Air Borne Sound installation at the Aerodynamic Park, Street names and local landmarks referencing the site’s aviation heritage | Local business names (e.g., bar, business park) named after the Zeppelin Airship Factory | Names of local bars, restaurants and shops | Local street and place names | Following terminal redevelopment both interior and exterior elements will incorporate aviation-themed design references |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pijet-Migoń, E. Aviation Heritage in the Urban Landscape—Concept and Examples from Berlin. Heritage 2025, 8, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060225

Pijet-Migoń E. Aviation Heritage in the Urban Landscape—Concept and Examples from Berlin. Heritage. 2025; 8(6):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060225

Chicago/Turabian StylePijet-Migoń, Edyta. 2025. "Aviation Heritage in the Urban Landscape—Concept and Examples from Berlin" Heritage 8, no. 6: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060225

APA StylePijet-Migoń, E. (2025). Aviation Heritage in the Urban Landscape—Concept and Examples from Berlin. Heritage, 8(6), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060225