Didactics with Art: A PRISMA Systematic Review on the Integration of Flamenco in Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

State of the Art

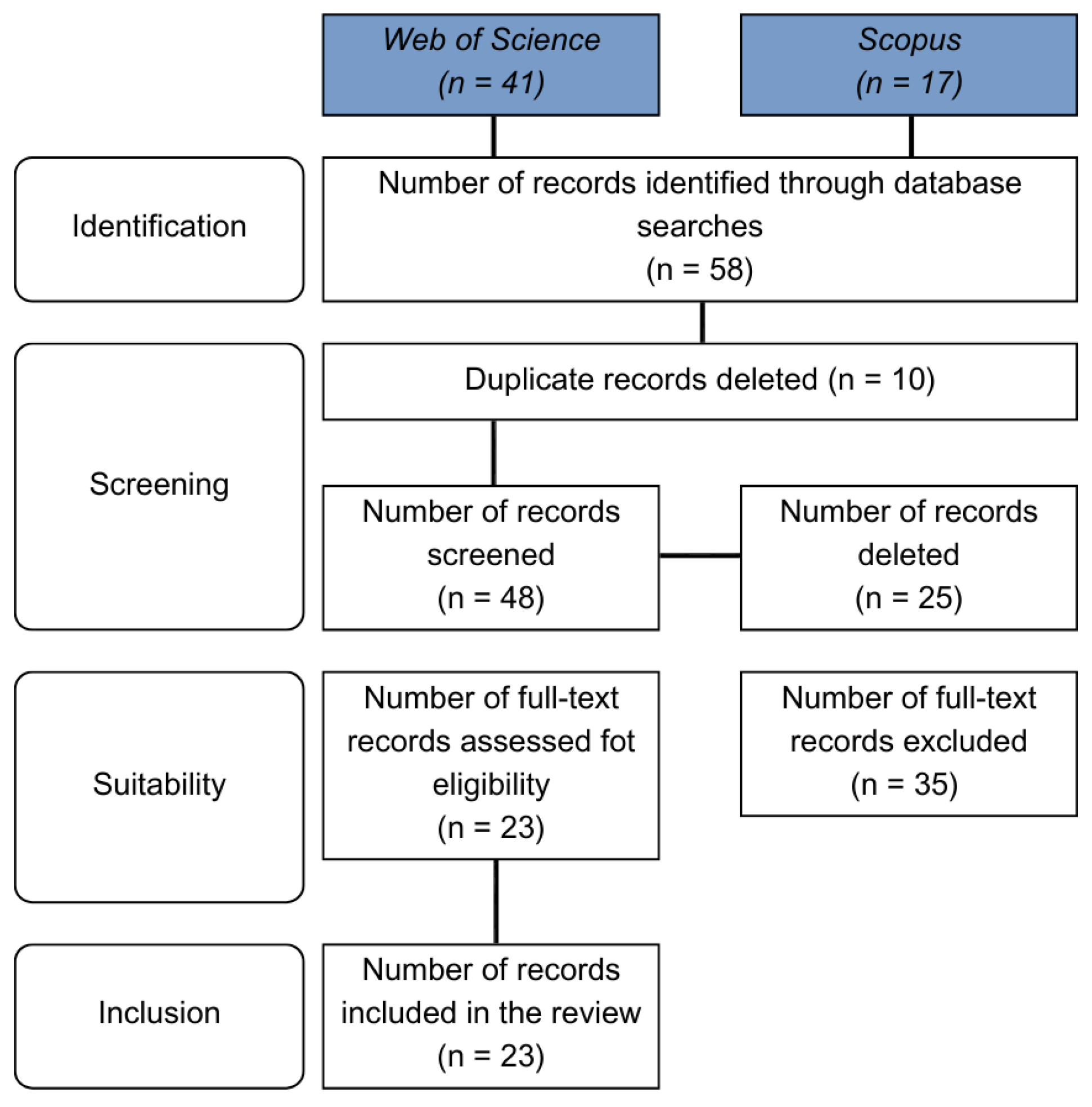

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

- To deepen comparative studies between autonomous communities or between countries to identify models of implementation of flamenco and its relationship with the cultural and educational context.

- To develop research focused on the evaluation of the impact of flamenco on specific student competencies, such as oral expression, self-esteem, creativity, intercultural awareness or historical memory.

- To explore the use of emerging technologies (virtual reality, gamification, artificial intelligence) in the teaching of flamenco, especially in environments where there is no living tradition of this manifestation.

- To extend research to other less explored educational stages, such as secondary education, adult education and vocational training, in order to understand the real scope of flamenco beyond the infant and primary stages.

- To investigate the role of flamenco as a tool for inclusive education in diverse groups, including students with disabilities, immigrants, cultural minorities or young people at risk of exclusion.

- To expand the research by incorporating books, book chapters and other non-indexed academic sources in order to build a more complete and diverse knowledge map on the use of flamenco in education.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Flamenco—UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2010. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/flamenco-00363 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Heredia-Carroza, J.; Díaz-Reyes, L.; Agheorghiesei, D.-T.; Stoica, R. Cultural Heritage in Education: Flamenco as a Pedagogical Tool for Future Teachers in Spain. Heritage 2025, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padial Ruz, R.; Ibáñez-Granados, D.; Fernández Hervás, M.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L. Proyecto de baile flamenco: Desarrollo motriz y emocional en educación infantil. Retos 2019, 35, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Vázquez, M.; Llorent-Bedmar, V. The training of flamenco dance teachers of the Escuela Sevillana. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Mas, A.; Pozo, J.I.; Montero, I. The influence of music learning cultures on the construction of teaching-learning conceptions. Br. J. Music Educ. 2014, 31, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballer-Tarazona, M.; Cuadrado-García, M.; Montoro-Pons, J.D. Enseñanza artística no formal como instrumento de inclusión socioeducativa de jóvenes gitanos. Rev. Int. Educ. Justicia Soc. 2022, 11, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Hurtado, C.; Pérez Colodrero, C.I. Escuelas de flamenco y diversidad funcional: Una mirada desde la inclusión en la ciudad de Granada. Rev. Electrónica LEEME 2023, 51, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin-Arias, P.; Alarcón Rodríguez, E.; Colomer Sánchez, A. De la escena a las aulas: Los artistas y la incorporación de la danza española y el baile flamenco a las enseñanzas generales (From the stage to the classrooms: Artists and the incorporation of Spanish and flamenco dance into the general education). Retos 2021, 40, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarría-Ortiz, C.; Heredia-Carroza, J.; Montero-Lobato, B.; Palma, L. La implantación del flamenco en el currículo educativo andaluz: Entre la tradición y la innovación tecnológica. Campus Virtuales 2024, 10, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. Decree 97/2015, of March 3, Establishing the Organization and Curriculum of Primary Education in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia; BOJA 50 (Repealed Provision); Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport: Seville, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pardal-Refoyo, J.L.; Pardal-Peláez, B. Anotaciones para estructurar una revisión sistemática. Rev. ORL 2020, 11, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraquero-Rodríguez, D.; Baena-González, R.; Chavarría-Ortíz, C.; Gallardo-Guerrero, A.M. Social media en el balonmano: Una revisión sistemática. Cult. Cienc. Y Deporte 2024, 19, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morejón-Llamas, N.; Ramos-Ruiz, Á.; Cristòfol, F.-J. Institutional and political communication on TikTok: Systematic review of scientific production in Web of Science and Scopus. Commun. Soc. 2024, 37, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez García, L.; Pinna-Perez, A. Expressive Flamenco ©: An emerging expressive arts-based practice. Am. J. Danc. Ther. 2021, 43, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomina-Molina, T. Aprendizaje de los palos flamencos mediante el uso de la pintura abstracta. Artseduca 2021, 29, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Aldeguer, S. Evaluación de un taller de intervención socioeducativa: El ritmo musical en la formación de la identidad de jóvenes recluidos. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2013, 31, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bustos, J.; Cervantes-Hernández, N.; Domínguez-Esparza, S.; Enríquez-Del Castillo, L. Intervención psicomotriz en un alumno con disgrafía: Estudio de caso. Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Act. Física Y El Deporte 2021, 10, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Alonso, D.; Soto-Moreno, E. Transformación de un centro educativo a través de las artes: El caso del mural de los aviones y Camarón. Educ. Artística Rev. Investig. (EARI) 2024, 15, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Ferrer, A. «¡Así se cría una juventud que pudiera ser tan útil si fuera la educación igual al talento!»: La juerga del Tío Gregorio de José Cadalso (1774). El flamenco y los conflictos de la Ilustración. Cuad. Ilus. Y Romant. 2024, 30, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.P.; Mollá, A.F.A.; Naranjo, F.J.R. Danzas tradicionales en España. Estudio bibliométrico basado en buscadores de alto impacto. Retos 2024, 51, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.; Cisneros, R.E.; Whatley, S. Motion capturing emotions. Open Cult. Stud. 2017, 1, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gértrudix-Barrio, F.; Estévez-García, Ó. Los saxofonistas en los conservatorios profesionales españoles: Su incorporación al mercado laboral. Artseduca 2021, 29, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Mas, A.; Pozo, J.I.; Scheuer, N. Musical Learning and Teaching Conceptions as Sociocultural Productions in Classical, Flamenco, and Jazz Cultures. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2015, 46, 1191–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Mas, A.; López-Íñiguez, G.; Pozo, J.I.; Montero, I. Function of private singing in instrumental music learning: A multiple case study of self-regulation and embodiment. Music. Sci. 2019, 23, 442–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel-Alvarado, R.; Casas-Mas, A.; López-Íñiguez, G.; Johnson, L. Patterns of variation in sociomusical identity of school-goers in a condition of social vulnerability and musical gaps in their education. Music Educ. Res. 2022, 25, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de las Heras-Fernández, R.; Bonastre Vallés, C.; Calderón-Garrido, D.; Anguita Acero, J.M. Implicit theories on teaching, learning, and evaluating flamenco dance in the classroom: Demographic comparison of Spain and Japan. Int. J. Instr. 2024, 17, 697–714. Available online: https://e-iji.net/ats/index.php/pub/article/view/540 (accessed on 1 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- de las Heras-Fernández, R.; Coll, M.V.G.; Espada, M. Receptiveness of Spanish and flamenco professional dancers in their training and development. Int. J. Instr. 2020, 13, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Mas, A.; Pozo, J.I.; Montero, I. Oral tradition as context for learning music from 4E cognition compared with literacy cultures: Case studies of flamenco guitar apprenticeship. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 733615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant | Any participant related to flamenco research and its use and implementation in the educational classroom. | None |

| Intervention | Any intervention related to flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom. | None |

| Comparator/Context | Open access, research articles, published research, articles written in any language, case studies, comparative analysis. | No open access, no research articles, unpublished research, articles written in a language other than Spanish. |

| Results | Records dealing with flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom. | Records that have no link to flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom. |

| Study design | Open-access articles in any language, with defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, quality assessment of sources and thematic analysis to identify trends and gaps in research. | Articles with restricted access, without clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, or without evaluation of the quality of the sources or structured analysis. Factors that hinder the identification of trends and gaps in the research. |

| Objectives | Research Questions | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| SO1. Study the characteristics of research on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom in academic and socioeconomic settings. | RQ1. How has research on flamenco and its use and implementation in the classroom evolved over time? | Year of publication |

| RQ2. What is the geographical distribution of publications on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom and is there international collaboration? | Countries with the highest publication rates (country of first author). Number of authors. Number of countries per paper | |

| RQ3. Which universities and institutions are leading research on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom? | First author affiliation | |

| RQ4. Which are the journals that publish the most about flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom and what impact do they have? | Journal name. Journal Citation Indicator (JCI) quartile/percentile | |

| RQ5. What keywords are identified in the literature on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom? | Keywords | |

| SO2. Define the methodologies used in the studies to understand how the phenomenon of territorial brands is being analyzed. | RQ6. What type of methodology and techniques are used in flamenco studies and their use and implementation in the educational classroom? | Methodology: quantitative, qualitative, mixed, descriptive, explanatory, cross-sectional or unspecified. Techniques: observation, surveys, interviews, content analysis, case studies, unspecified |

| RQ7. What is the sample size in studies on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom? | Sample size | |

| RQ8. What territories or regions are studied to understand flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom? | Selected country/territory | |

| SO3. Analyze the findings and limitations of studies on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom and depict future trends. | RQ9. What conclusions can be drawn from the studies on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom and what kind of applications do they have? | Summary of conclusions |

| RQ10. What are the main limitations identified in the articles on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom? | Description of limitations | |

| RQ11. What are the future trends in research on flamenco and its use and implementation in the educational classroom? | Description of future prospects |

| Database | Title | Authors | Journal/Media of Publication | Impact Index | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | Evaluación de un taller de intervención socioeducativa: el ritmo musical en la formación de la identidad de jóvenes recluidos | Santiago Pérez Aldeguer | Revista de Investigación Educativa | Q2 | Personal, relational, social and collective identity improved; self-esteem did not show significant changes. |

| Web Of Science | The influence of music learning cultures on the construction of teaching-learning conceptions | Amalia Casas-Mas, Juan Ignacio Pozo and Ignacio Montero | British Journal of Music Education | Q2 | The Flemish culture distances itself from the conception of teaching; it presents more direct profiles as opposed to the constructive ones of the classical sphere. |

| Web Of Science | Musical Learning and Teaching Conceptions as Sociocultural Productions in Classical, Flamenco, and Jazz Cultures | Amalia Casas-Mas, Juan Ignacio Pozo, Nora Scheuer | Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology | Q2 | Musical learning differs culturally: flamenco is implicit and embodied, classical is explicit and conceptual, jazz intermediate. |

| Scopus | Motion Capturing Emotions | Karen Wood, Rosemary E. Cisneros, Sarah Whatley | Open Cultural Studies | Q2 | The use of immersive environments enhances dancers’ bodily and emotional awareness, revealing new sensory experiences. |

| Web Of Science | Function of Private Singing in Instrumental Music Learning: A Multiple Case Study of Self-Regulation and Embodiment | Amalia Casas-Mas, Guadalupe López-Íñiguez, Juan Ignacio Pozo, Ignacio Montero | Musicae Scientiae | Q2 | Private singing aids self-regulation and learning embodied in instrumentalists; little used as a reflective tool. |

| Scopus | Proyecto de baile flamenco: desarrollo motriz y emocional en educación infantilFlamenco dance project: motor and emotional development in early childhood education | Rosario Padial-Ruz, Delia Ibáñez-Granados, Marina Fernández Hervás, José Luis Ubago-Jiménez | Retos | Q4 | Flamenco is an effective didactic resource for the integral development of students in early childhood education, improving motor skills, emotional expression, self-esteem and social cohesion. |

| Web Of Science | Receptiveness of Spanish and Flamenco Professional Dancers in Their Training and Development | Rosa de las Heras-Fernández, María Virginia García Coll, María Espada | International Journal of Instruction | Q3 | Receptiveness to coaching decreases with age and varies by company |

| Scopus | Escuelas de flamenco y diversidad funcional: una mirada desde la inclusión en la ciudad de Granada | Carmen Ramírez Hurtado, Consuelo Pérez Colodrer | Revista Electrónica de LEEME | Q4 | Flamenco is an inclusive practice; there is a lack of specific teacher training, although there is great empathy. |

| Web Of Science | Expressive Flamenco ©: An Emerging Expressive Arts-Based Practice | Laura Sánchez García, Angelica Pinna-Perez | American Journal of Dance Therapy | Q3 | Flamenco can facilitate therapeutic processes through the connection with the ‘duende’. |

| Web Of Science | Learning flamenco styles through the use of abstract painting | Teresa Colomina-Molina | ArtsEduca | Q4 | The use of abstract painting allows for a creative understanding of Flemish styles. |

| Web Of Science | Los saxofonistas en los conservatorios profesionales españoles: su incorporación al mercado laboral | Felipe Gértrudix-Barrio, Óscar Estévez-García | ArtsEduca | Q4 | Diversification and educational updating in conservatories are required to prepare saxophonists for the labor market. |

| Web Of Science | Intervención psicomotriz en un alumno con disgrafía: estudio de caso | J.B. González-Bustos, N. Cervantes-Hernández, S. Domínguez-Esparza, L.A. Enríquez-Del Castillo | Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte | Q4 | Significant psychomotor improvements after intervention; more effective handwriting. |

| Web Of Science | De la escena a las aulas: los artistas y la incorporación de la danza española y el baile flamenco a las enseñanzas generales | Patricia Bonnim-Arias, Estela Alarcón Rodríguez y Ana Colomer-Sánchez | Revista Retos | Q4 | The recreational and cognitive nature of extracurricular activities predominates; gender and economic inequalities persist. Shift towards cognitive activities such as robotics and programming. |

| Web Of Science | Oral Tradition as Context for Learning Music From 4E Cognition Compared With Literacy Cultures. Case Studies of Flamenco Guitar Apprenticeship | Amalia Casas-Mas, Juan Ignacio Pozo, Ignacio Montero | Frontiers in Psychology | Q1 | The oral tradition of flamenco implies an embodied and integrated learning with the environment and culture. |

| Web Of Science | Patterns of Variation in Sociomusical Identity of School-goers in a Condition of Social Vulnerability and Musical Gaps in their Education | Rolando Angel-Alvarado, Amalia Casas-Mas. Guadalupe López-Íñiguez y Lauren Johnson | Music Education Research | Q2 | Musical practice conditions sociomusical identity, with inequalities marked by social context. |

| Web Of Science | Enseñanza Artística no Formal como Instrumento de Inclusión Socioeducativa de Jóvenes Gitanos | María Caballer-Tarazona, Manuel Cuadrado-García, Juan De Dios Montoro-Pons | Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social | Q3 | Flamenco promotes personal development and socio-educational inclusion in young gypsies. |

| Web Of Science | Implicit theories on teaching, learning, and evaluating flamenco dance in the classroom: Demographic comparison of Spain and Japan | Rosa de las Heras-Fernández, Carolina Bonastre Vallés, Diego Calderón-Garrido, Juana María Anguita Acero | International Journal of Instruction | Q3 | Predominance of the constructivist approach; influences of country, age and gender on educational preferences. |

| Web Of Science | Transformación de un centro educativo a través de las artes: el caso del mural de los aviones y Camarón | Diego Ortega-Alonso, Estrella Soto-Moreno | Educación Artística: Revista de Investigación (EARI) | Q4 | The mural promoted ecological and heritage awareness and community cohesion. |

| Web Of Science | The Training of Flamenco Dance Teachers of the Escuela Sevillana (Sevillian School) | Macarena Cortés-Vázquez, Vicente Llorent-Bedmar | Education Sciences | Q2 | The teachers build their pedagogical knowledge from experience; it highlights the importance of teacher professionalization in flamenco. |

| Web Of Science | La implantación del flamenco en el currículo educativo andaluz: entre la tradición y la innovación tecnológica | Carlos Chavarría-Ortiz, Jesús Heredia-Carroza, Beatriz Montero-Lobato, Luis Palma | Campus Virtuales | Q1 | Flamenco is valued as a pedagogical tool, but there is a lack of training and cultural participation among teachers. |

| Web Of Science | «¡Así Se Cría Una Juventud Que Pudiera Ser Tan Útil Si Fuera La Educación Igual Al Talento!»: La Juerga Del Tío Gregorio De José Cadalso (1774). El Flamenco Y Los Conflictos De La Ilustracion | Alberto Romero Ferrer | Cuadernos de Ilustración y Romanticismo | Q4 | Flamenco was perceived negatively by the Enlightenment, linked to ignorance and backwardness. |

| Scopus | Cultural Heritage in Education: Flamenco as a Pedagogical Tool for Future Teachers in Spain | Jesús Heredia-Carroza, Laura Díaz-Reyes, Daniela-Tatiana Agheorghiesei, Raluca Stoica | Heritage | Q2 | Flamenco promotes emotional, social and cognitive development; it is valued as an effective pedagogical tool. |

| Scopus | Traditional dances in Spain. Bibliometric study based on high impact search engines | Roser Penalva Martínez, Antonio Francisco Arnau Mollá, Francisco Javier Romero Naranjo | Retos | Q3 | Flamenco is the most mentioned genre, and dance is the predominant area; it is suggested as a starting point for future research. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cortés-Vázquez, M.; Chavarría-Ortiz, C.; Berraquero-Rodríguez, D.; Heredia-Carroza, J. Didactics with Art: A PRISMA Systematic Review on the Integration of Flamenco in Education. Heritage 2025, 8, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060223

Cortés-Vázquez M, Chavarría-Ortiz C, Berraquero-Rodríguez D, Heredia-Carroza J. Didactics with Art: A PRISMA Systematic Review on the Integration of Flamenco in Education. Heritage. 2025; 8(6):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060223

Chicago/Turabian StyleCortés-Vázquez, Macarena, Carlos Chavarría-Ortiz, Diego Berraquero-Rodríguez, and Jesús Heredia-Carroza. 2025. "Didactics with Art: A PRISMA Systematic Review on the Integration of Flamenco in Education" Heritage 8, no. 6: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060223

APA StyleCortés-Vázquez, M., Chavarría-Ortiz, C., Berraquero-Rodríguez, D., & Heredia-Carroza, J. (2025). Didactics with Art: A PRISMA Systematic Review on the Integration of Flamenco in Education. Heritage, 8(6), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8060223