1. Introduction

1.1. Historic Background of the Synagogues of Greece

Greek Jewish history dates back to antiquity. Archaeological evidence attests to the existence of numerous vibrant organized Jewish communities [

1], wealthy enough to erect prominent synagogues adorned with magnificent mosaics. Notable examples include sites in Aegina [

2] (p. 30) (

Figure 1) and Chios [

3] (pp. 1385–1410), both dating to the 4th century CE.

The Greek speaking Romaniote Jewish communities had their own customs and liturgy, and their synagogues exhibited a very distinct architectural typology, especially in their interior organization. In western Greece, communities such as Ioannina, Kastoria, Arta, and Trikala were strongly influenced by Venetian traditions, such as the bipolar synagogue layout [

4] (

Figure 2). Another Romaniote tradition found on the island of Rhodes hints at a different typology [

5] (p. 144). There, the local synagogue architecture appears to have been strongly influenced by the magnificent basilica in Sardis, particularly in the adoption of a dual Holy Ark placed on the southeastern wall (

Figure 2). This typology has been recently documented and published on by the author, following site visits and field surveys of the historic synagogues Kahal Tikkun Hazot and Kahal Grande in Rhodes [

6], (pp. 192–198, 200–201).

After the 15th century, Spanish Jews (Sephardim) arrived in various Greek cities under Ottoman rule, establishing flourishing communities and revitalizing commercial activity throughout Greece. They developed a distinct synagogue architectural typology, inspired by the synagogues of Spain. During the Ottoman period, Jewish quarters were typically located in walled historic city centers, often enclosed and gated. Due to their proximity to the city center and shared market space, this vibrant Jewish life coexisted—although not always harmoniously—with Greeks, Muslims, and Armenians. Ottoman-era synagogues generally followed a different typology, characterized by a square or rectangular building with four central columns (

Figure 2). Within this defined space, under a decorated flat dome or a daylit lantern, stood the

Bimah, facing the Holy Ark, which was always oriented towards Jerusalem. Seating, in the form of benches and wooden chairs, was arranged around the

Bimah on all sides, except for the space between the

Bimah and the Holy Ark. Like synagogues elsewhere, all Greek synagogues, whatever the origin of their tradition, followed the rules of Halakhah [

7,

8]. The city of Thessaloniki, in particular, emerged as a prominent center of Jewish life, with distinguished institutions and nearly 60 synagogues

1 by the eve of the Second World War [

9] (pp. 286–288).

Before the Second World War, more than 70,000 Jews lived in Greece, spread across 27 organized communities throughout the country [

10] (pp. 36–37). Each community maintained at least one synagogue along with several communal institutions. Frequently, the Jewish community center (or club) was located adjacent to the synagogue. In Thessaloniki, Greece’s largest Jewish community of approximately 56,000 members, there were nearly 60 synagogues and

midrashim (small prayer halls) across the city center [

9] (pp. 285–288) as well as the eastern and northern parts of the city. A map created recently by the author for the Greek National Archaeological Registry [

11] (

Figure 3) and the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki indicates the exact location of about 70

2 known synagogues in Thessaloniki and nearly 270 other Jewish sites and synagogues across Greece. These visualizations underscore the substantial impact of Jewish presence in both Thessaloniki and Greece more generally prior to the Second World War.

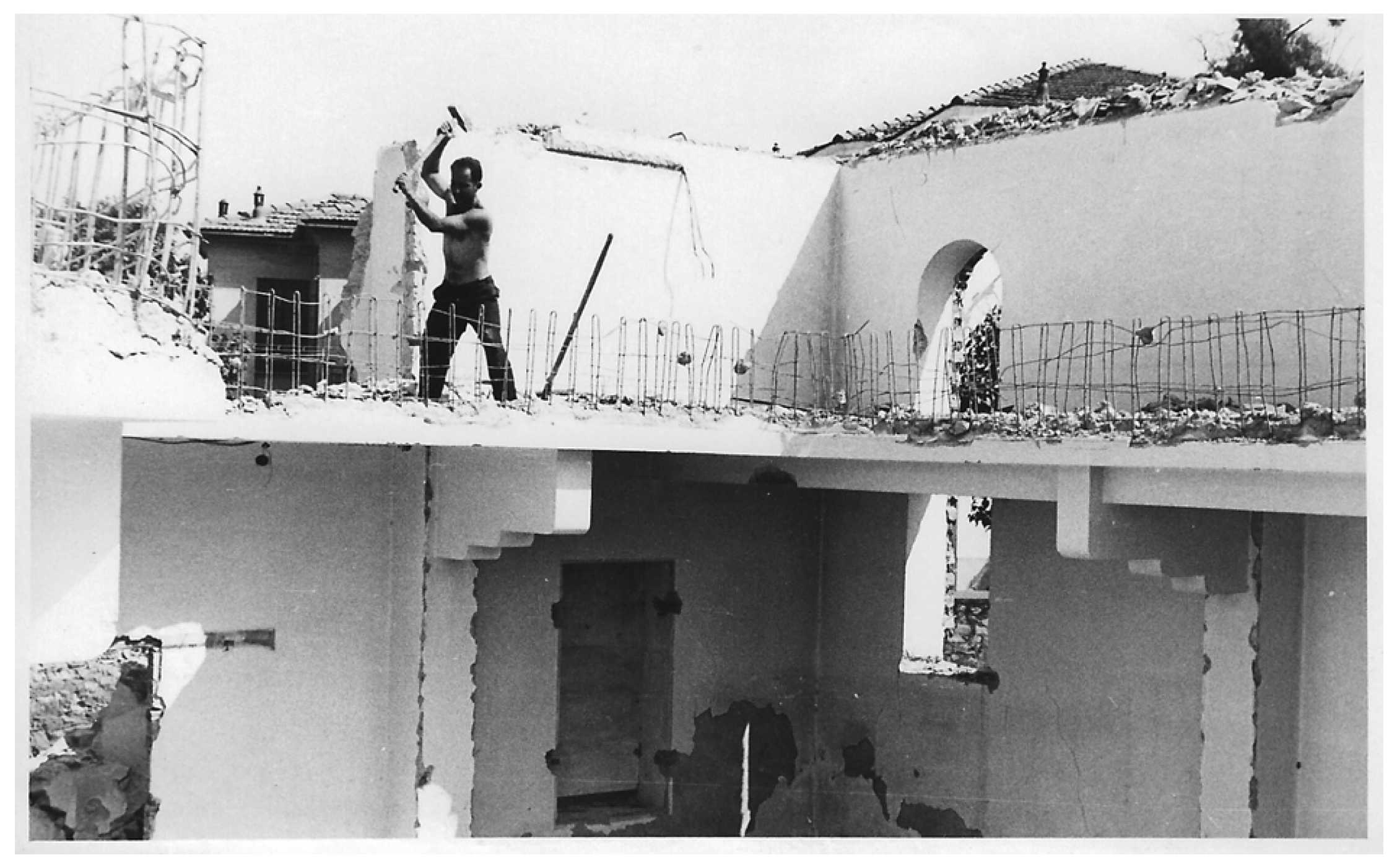

The deportation of the Greek Jewish communities took place between 1943 and 1944, under German and Bulgarian occupation. During the Holocaust, 87% of the Jewish communities were annihilated; in Thessaloniki, the figure reached 96%. This catastrophic loss devasted Jewish life in Greek cities. Jewish institutions such as hospitals, welfare organizations, and especially synagogues were vandalized, looted, occupied by new owners, or destroyed [

12] (pp. 57–138). Of the approximately 100 synagogues that once stood across Greece, only a fraction survived. Many were left in ruins—as in Volos and Ioannina—while others were appropriated by Christian organizations, such as in Xanthi, Alexandroupolis, and Didimoteicho (

Figure 4), where synagogues were converted into Sunday schools.

Postwar emigration to Israel, larger cities (primarily Athens), or abroad further diminished Jewish populations in many Greek cities. Starting in the 1970s, many surviving Jewish communities were officially dissolved, and their synagogues followed their fate. In most cases, the plots were sold and the buildings demolished.

Documentation of Greek synagogues prior to the Second World War is rare. Notable exceptions include architectural drawings of the Kahal Shalom synagogue in Kos, housed in the Italian archive in the Special Historical and Folklore Archive of the Municipality of Kos, and the diagrams for the synagogues Ricos and Talmud Torah found in the Land Registry in Rhodes. Apart from these and a few other exceptional cases, most synagogues demolished between the late 1970s and the mid-1990s left no traces or documentation behind.

1.2. The Reconstruction of Historic City Centers in Greece

With 54% of the world’s population now concentrated in urban areas [

13] (p. 1), cities are being reshaped to accommodate this shift. The post-Second World War reconstruction of city centers changed the face of many historic cities, as can be seen today particularly across regions such as Greece, Turkey, Egypt, and Malta were serial repetition of disorderly units replaced traditional urban form and hierarchy in the 20th century leading to a dramatic collapse of urban structure [

14] (p. 74). In particular, the transformation of traditional Istanbul, starting in the late 1960s, and portrayed in Orhan Pamuk’s

A Strangeness in My Mind, where the gradual replacement of the traditional urban cityscape with modern apartment blocks built to house migrants from Anatolia and the Black Sea is traced [

15]. In 2007, the World Heritage Committee warned of the harmful impacts of urban development amid a ‘crisis’ in urban conservation, citing historic districts in Istanbul and Cairo. Valletta, inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1980, exemplifies efforts to preserve historic fabric against modern encroachment—unlike adjacent Msida and the waterfront, where traditional low-rise blocks have been fragmented and overshadowed by high-rise development [

16].

In Greece, led primarily by engineers rather than architects, this reconstruction prioritized rapid solutions to housing shortages over heritage preservation. Greek journalist and writer Nikos Vatopoulos has expressed his nostalgia and concern over the future of historic buildings in Athens due to modern reconstruction [

17].

As a result, urban transformations often erased much of the historic built environment, such that the few surviving historic buildings struggle to maintain a visible link with their past. During this period, the architectural diversity of the urban context—once expressed by local and often eclectic styles—was largely lost. Historic residences and mansions, tobacco warehouses, public buildings, and movie theaters were replaced by uniform residential blocks devoid of character or connection to the historic cityscape. In Xanthi, Northern Greece, for example, until the early 1990s, the synagogue was one of the last remaining historic landmarks in a transforming urban context, a transformation that was to be completed some years later, with the demolition of the synagogue and the erection of a residential block in its place (

Figure 5).

These blank-side-walled structures dominate the urban view, standing in anticipation of adjacent buildings to fill remaining gaps. The juxtaposition of low-rise historic structures and towering new residential blocks emphasizes the uncomfortable transition from past to present. This gradual shift homogenizes, erases, and forgets. With a new paradigm of modernity, the glass-skyscraper-dominated cityscape has little tolerance for the modest historic monuments of the past.

Urban theorist Kevin Lynch [

18] (pp. 1–2) argues that the city is a spatial construct with layers beyond what the eye can see or the ear can hear. In Lynch’s view, exploring these hidden layers allows us to bring clarity, or “legibility”, to the cityscape, uncovering not only the present-day narrative but also the obscured narrative of its recent past. The Greek synagogues analyzed in this study illustrate how political or ideological projects may erase part a city’s architectural heritage, even when these elements have been integral to the city’s identity for centuries [

19]. The mechanisms that rendered Greek synagogues “invisible” reflect broader processes of marginalization, such as the erasure of Jewish heritage in the Polish city of Wroclaw, as examined by Cervinkova and Golden [

20].

Although integrated for centuries in historic city centers and embedded in the public consciousness as public buildings and urban landmarks, many Greek synagogues gradually disappeared after the abrupt deportation of Jewish communities in the Holocaust. Their absence become more pronounced as they faded from urban consciousness during the post-war period; they became an “invisible” heritage, discernible only to those with direct knowledge or memory. This loss affected both large and small cities, but its impact was particularly profound in smaller one. The Jewish community, historically cosmopolitan and associated with creativity, financial prosperity, and commercial vitality, played a driving role in local economies. Through commerce, light manufacturing and trade, these communities often connected remote towns to the cultural and economic centers of Europe, both East and West [

21] (p. 23). In many cases, their disappearance significantly weakened the city’s economic base, prompting younger, educated populations to emigrate to larger commercial centers in Greece or abroad, further diminishing the post-war commercial, cultural, and social potential of these cities.

1.3. The Survey and Study of the Synagogues of Greece

The project initiated by the author to document, survey, map, and represent demolished synagogues in Greece began during a period of relative indifference to the subject. Unsurprisingly, initial reactions ranged from indifference to resistance, as the project challenged the status quo and unearthed a suppressed yet endangered heritage. The urgency of this initiative was heightened by the ongoing reconstruction of historic city centers in the early 1990s. However, support from Jewish communities was often limited, as many were themselves participating in the wave of urban redevelopment that threatened the endangered synagogues being documented.

Today, both Jewish and non-Jewish communities recognize the value of reintegrating “lost” historic and architectural layers into the urban landscape. Doing so enriches the cityscape and deepens the uniqueness of the urban experience. Further, by making the “invisible” visible through technology, the project reconnects local communities and individuals to a not-so-distant past that urban modernization has abruptly rendered “invisible”.

Reconstructing the location and form of lost synagogues is not merely about preserving the memory of individual buildings. It seeks to safeguard the memory of urban diversity and multiculturalism that was erased through the homogenization of post-Second World War reconstruction. The author’s project moves beyond conventional architectural survey and documentation, incorporating historical archives and oral histories

3 from both Jewish and non-Jewish individuals. These narratives add more layers and infuse the synagogues with life, connecting them to the neighborhoods, cities, and communities they served before the war. The project aims not only to preserve but also to give form and voice to these now-“invisible” buildings and places once vibrant with Jewish life. To this end, VR can offer immersive spatial experiences that engage contemporary audiences. In parallel, traditional methods of dissemination—publications, exhibitions, lectures, and book presentations—help share stories and make research archival documents more accessible to wider audiences. With these combined tools, the project brings a nearly “invisible” heritage back into public view and collective memory [

22,

23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Documentation Project

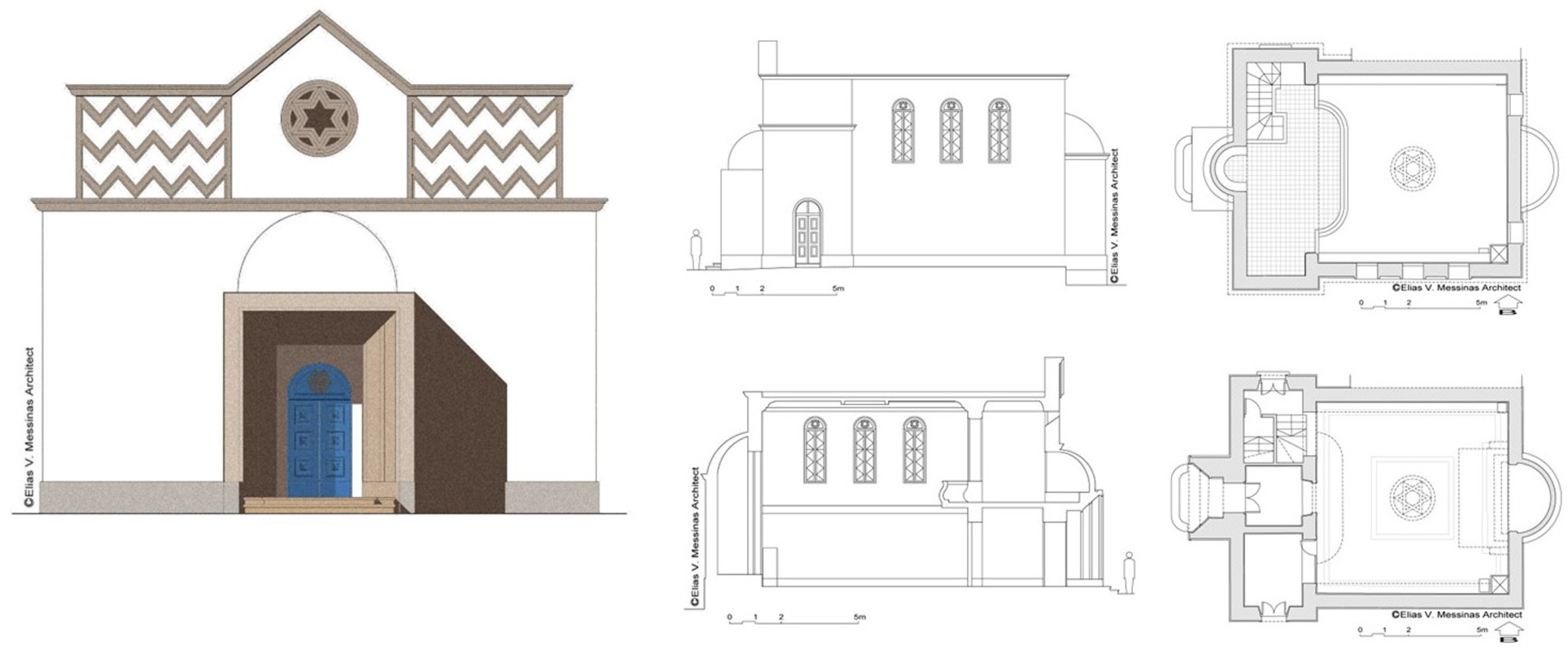

Preserving the architectural legacy of Greek synagogues requires a detailed survey of the actual structures. For those still standing, the project preserved their physical form through detailed architectural drawings and exhaustive photographic documentation. The project’s methodology consisted of a series of progressive steps undertaken between 1993 and 1996, as site visits were completed. The initial phases included in situ surveys of all standing synagogues—22 in total—followed by the digitization of these surveys and photographic documentations through scanning (

Figure 6). As digital technologies advanced, they were integrated into the project to enhance accuracy, engagement, and interactivity. For example, VR was employed so visitors could ‘experience’ the former interiors of these synagogues.

The project formed the basis for the author’s doctoral thesis at the National Technical University of Athens, supervised by Prof. Yiorgos Sariyiannis, Prof. Aleka Karadimou-Gerolympou, and Dr. Doron Chen. The dissertation was completed in 1999. Archival research complemented the fieldwork, primarily the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People now located at the National Library in Jerusalem, the archive of the Jewish Museum of Greece in Athens, and the archives of KISE and OPAIE. The in situ drawings were subsequently digitized into CAD architectural drawings, including floor plans, sections, and elevations. In some cases, elevations were rendered in color to reflect the building’s original appearance, alongside 3D digital models.

Findings from the research were published in 1997, 2011, and subsequently in various academic publications and articles. However, the recent discovery of new evidence has required further survey expeditions. Notably, as recently as November 2024, the author conducted a new survey of two ‘forgotten’ synagogues in Rhodes.

Either shortly before or during the author’s expeditions, several synagogues that had survived in abandoned states, such as those in Xanthi, Didimoteicho, and Alexandroupolis, were demolished or renovated to such an extent that their historic character was altered. Others, including those in Kavala and Komotini, were also demolished after prolonged abandonment. Fortunately, most of these were surveyed and documented before their loss.

2.2. The Shemtov Samuel Archive

However, what of the synagogues that were demolished in the 1960s, 70s, or 80s, prior to the author’s fieldwork, leaving behind no known architectural record? How can we accurately reconstruct these synagogues whose existence is preserved only in oral accounts? Can we recover any architectural data on their physical forms? For years, the author sought the answer to these questions by pursing any possible source of visual evidence of synagogues demolished before the early 1990s. Searches in museum archives, photographic collections, and aerial images yielded limited results.

This changed in May 2023, with the accidental discovery of a rare, previously unknown archive [

24]. Under unexpected circumstances, the author was contacted and subsequently granted full rights to an archive dating from 1960 to 1961. This archive belonged to architect Shemtov Samuel (1939–2009) from Volos, Greece and was discovered by his nephew in Greece, and by Samuel’s wife and son at their house in London, where the family had lived since 1969. The significance of this archive has recently been published by the author [

6].

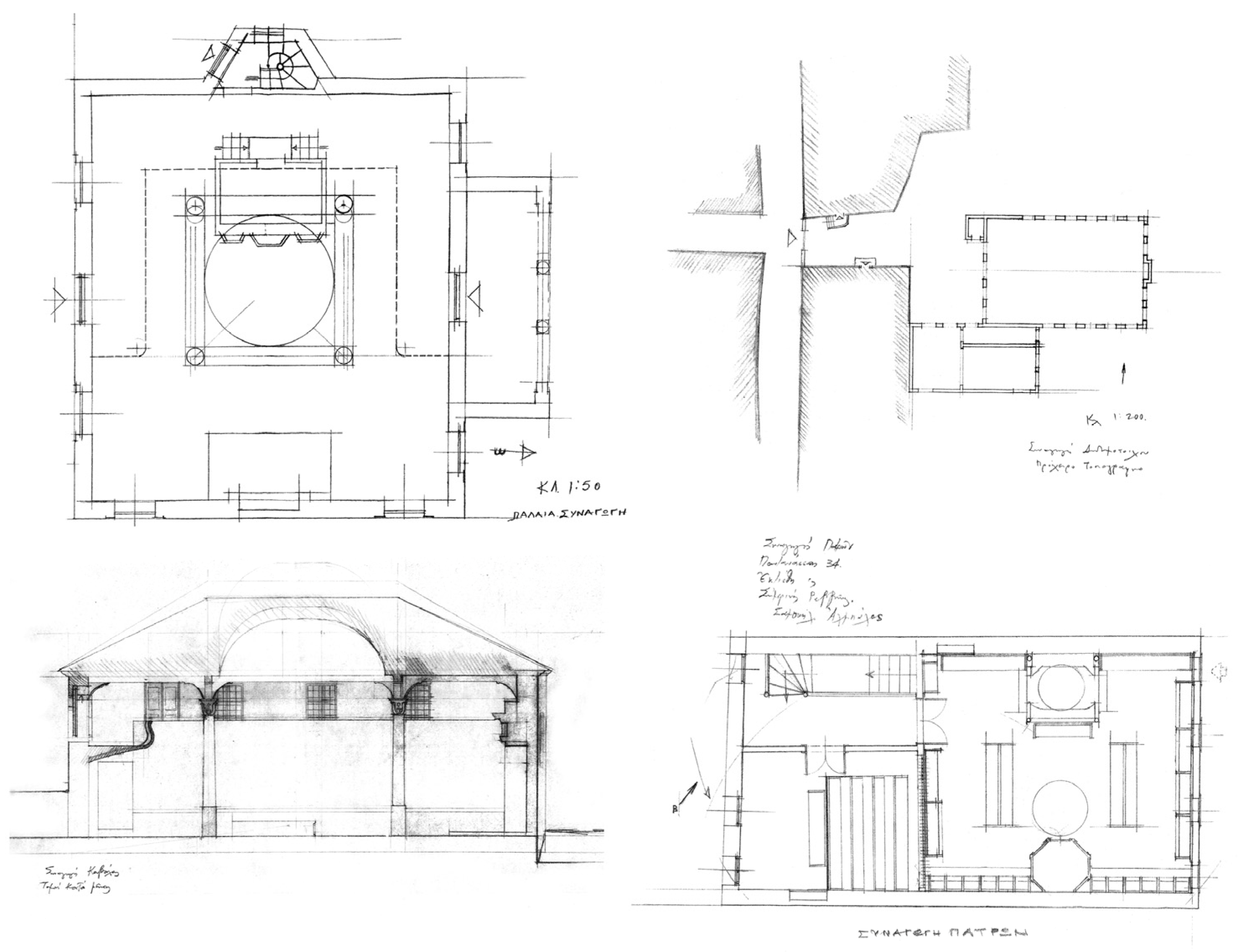

The Samuel archive contains some extraordinary surveys of synagogues that were later demolished (

Figure 7). Created in early 1960 in preparation for a lecture Samuel delivered to his class on 10 February 1961, these records—though incomplete—are invaluable. In many cases, they represent the only surviving evidence of these now-demolished synagogues. The Samuel archive is currently being digitized by the author, who is producing digital CAD drawings, including floor plans, sections, and elevations, from Samuel’s original survey sketches. These efforts aim to ensure the highest possible fidelity between the digital reconstruction and the synagogues’ original forms.

Among the Samuel archive’s contents are rare and previously unpublished materials documenting the pre-war synagogue in Volos, demolished in 1960 after sustaining earthquake damage on 19 April 1955 (

Figure 8); the synagogue in Drama, left unfinished during its construction (1940–1941) and later demolished; the synagogue in Didimoteicho and the adjacent Jewish community center, which was repurposed as a Christian Sunday school and then abandoned; and the Beth El synagogue in Kavala, damaged during the Bulgarian occupation, subsequently abandoned, and finally demolished in the 1970s.

The Samuel archive has left a full record of these buildings in both site surveys and photographic documentation. When combined with the author’s documentation archive, these two collections offer an unprecedented and accurate record of the majority of the synagogues that survived the Second World War in Greece.

3. Results

Physical and Digital Reconstruction

Starting in 2016, after two decades of research and publications on Greek synagogues, a series of architectural commissions began to apply this accumulated knowledge. The first project involved the Monastirioton synagogue (2016), the historic and central synagogue of Thessaloniki, designed in 1927 by Austro-Hungarian architect Ernst Loewy (1878–1943). Subsequent interventions in its interior and exterior, along with reinforcements after the earthquake of June 1978, had left the building in a state of neglect despite its continued use. In 2017, the author was commissioned to work on the Yad LeZikaron synagogue, constructed in 1984 on the ground floor of an office building on the former site of the pre-war synagogue Plassa (Burla). Notably, this synagogue houses the historic Holy Ark that belonged to the Ohel Yossef (Sarfati) synagogue of 1921, which was meticulously restored during the renovation.

In 2019, a commission to restore the Yavanim synagogue in Trikala followed. The historic building suffered from lack of waterproofing and needed structural reinforcements. Restoration involved replacing and repairing the interior finishes with materials compatible to the original. A bold intervention was the demolition of storefront additions from 1960 to 1962 that obscured the synagogue’s façade, thereby restoring the historic relationship of its visible presence on the street.

In 2022, a commission was received to restore the interior of the Kahal Shalom synagogue in Kos. Built in 1935 in the Italian Colonial style by the Italians who ruled the Dodecanese islands (1912–1948), this synagogue replaced an older one destroyed in the earthquake of April 1933. The restoration required extensive research on 1930s Italian synagogues and included the re-creation of the Holy Ark and

Bimah. Following the principles of circular economy and urban mining [

25] (pp. 122–123), these elements were constructed from repurposed furniture.

These restoration efforts required extensive research into original materials, colors, finishes, and construction techniques. Where needed, collaborations with experts in restoration, structural reinforcement, and electromechanical systems enhanced energy efficiency and long-term sustainability.

As the surveys and research progressed, visual evidence of certain lost synagogues was recovered. One such case was Beth Shaul, the central synagogue in Thessaloniki, designed by Vitaliano Poselli in 1898 and destroyed by the Nazis immediately after the deportation of the Jewish community in 1943. Through extensive research in city archives, a topographic plan of the synagogue was retrieved. Matched with numerous black and white photographs taken from different angles, this allowed for the development of a relatively accurate reconstruction of the synagogue in a full set of digital architectural drawings. To reconstruct Beth Shaul in a 3D model for the Yad Vashem Valley of the Communities exhibition (

Figure 9) in 1999–2000 [

26], the author consulted Holocaust survivors. To determine the colors of the finishes, floor tiles, and walls, the author interviewed the late Freddy Abravanel [

9] (pp. 265–272), who remembered praying at the synagogue with his family and vividly recalled these details. His testimony informed the first-ever reconstruction of the Beth Shaul synagogue, a laser-cut physical model at 1:20 scale that was exhibited at Yad Vashem.

A similar methodology guided the 3D reconstruction of the Aragon synagogue in Kastoria. Built in 1830, it was destroyed shortly after the deportation of the Jewish community in April 1944. Aerial photographs of 1945 and 1968 show many ‘voids’ in the Jewish quarter—Jewish homes that were confiscated and demolished—with the synagogue building clearly missing by 1968. A topographic plan of the Jewish quarter of Kastoria dating from 1965, commissioned by KISE, provided a fairly accurate footprint of the building in relation to the adjacent Jewish properties.

When the author was commissioned to create a 3D digital model and rendering of the interior and exterior of the synagogue for an exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki [

27], limited but sufficient visual material was available to successfully complete the task. An earlier schematic reconstruction by the late architect Panos Tsolakis had been published in 1994 [

28]. A 1935/1936 film [

29] by Sam Elias, captured during the visit of Bocko Mayo to Kastoria, provided footage that, when processed through screen shots into a collage image of the synagogue façade, formed the basis for the digital reconstruction. Together with the topographic plan and a handful of surviving photographs of the synagogue’s interior and exterior, this material allowed for a highly accurate digital reconstruction with correct proportions and relationships among the building parts (

Figure 10).

The 3D model reconstruction relied on an exhaustive collection of every surviving fragment of visual evidence to represent, as accurately as possible, a building that was demolished without a trace of physical evidence. Digital technology and publicly accessible online archives enabled this task to be completed successfully and within a very limited timeframe.

4. Discussion

This study underscores the transformative potential of digital technologies in reconstructing, preserving, and representing an almost obliterated architectural heritage: the synagogues of Greece. Many of these sites survive only in fragmented documentation or personal recollections, and yet, through the integration of CAD drafting, digital modeling, and virtual reality tools, it has become possible to effectively bridge the gap between incomplete historical documentation and contemporary visualization. When combined with physical in situ surveys of extant or similar buildings, these tools have enabled us to reconstruct the synagogues with a high degree of architectural fidelity and cultural relevance, even when physical remnants are scarce or lost.

One of the most significant contributions of this study lies in its interdisciplinary methodology, which combines architectural surveys, archival research, and survivor testimonies into a unified, digitally assisted reconstruction process. As shown in the study, this methodology has likewise proven useful in cases where a physical restoration is undertaken. Particularly significant was the rediscovery and digitization of the Shemtov Samuel archive, which proved a wealth of visual evidence on synagogues with limited prior documentation, such as the Beth El synagogue in Kavala and the pre-war synagogue of Volos [

6]. This methodology aligns with international best practices in digital heritage preservation, as exemplified by the digital reconstruction of Aleppo’s Great Synagogue, based primarily on a pre-destruction photographic survey [

30]. It has not only expanded the depth and scope of Greek synagogue studies, but it has also established a replicable model for the digital recovery of other lost heritage sites.

Beyond its architectural accomplishments, the project’s findings have illuminated the broader cultural, educational, and emotional significance of digital heritage work. These reconstructions do not merely visualize architectural forms; they reactivate collective memory, inspire further academic inquiry by inciting the minds of future researchers, and generate public engagement through physical and virtual exhibitions, immersive VR experiences, and storytelling. The Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki’s exhibitions, which combine traditional and digital curatorial practices, demonstrate the growing public interest in reclaiming lost cultural heritage and exploring the invisible layers of the urban landscape. Moreover, these reconstructions hold significant potential to inform contemporary urban planning by guiding the reintegration of both remaining and lost historic synagogues into their urban contexts.

Within an academic context, examining issues related to a city’s memory and collective identity in relation to the evolving built environments offers opportunities for urban exploration. One such example is a workshop held in September 2023 by the Architecture School of the Democritus University of Thrace, titled “Historical Walk: Visible and Memorable Landmarks of Xanthi.” [

31]. Faculty and students of architecture toured the historic city center of Xanthi, exploring both hidden and visible cultural heritage buildings, including the now-rebuilt location of the synagogue. The same year, an Erasmus+ Virtual Exchange program between the Architecture School of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Graz in Austria titled “European Jewish History: How do Cities ‘Think’ about and ‘Act’ on their Jewish Past?” [

32]. Completed in May 2023, the course examined human agency in appropriating urban space to construct meaning through individual practices, and qualitatively engaged with spatial making processes through annotated walking interviews, dealing with the visibility of Jewish history in urban space.

Nevertheless, the process has not been without challenges. Technically, reconciling inconsistent or incomplete data from disparate sources required careful interpretation and, at times, informed conjecture. Balancing scholarly accuracy with imaginative visualization highlighted the ethical complexities of digital heritage work. In many cases, the absence of complete documentation posed a persistent limitation, sometimes only partly offset by comparison with typologically similar sites. Social and institutional resistance in the early stages, compounded by the marginalization of Jewish heritage in public discourse, further complicated the author’s work, sometimes limiting access to sites, archives, and community narratives.

Yet, one of the most unexpected findings of this study was the enduring emotional resonance of these “lost” synagogues in the collective memory and identity of local communities. Even when physically erased, they endure as symbols of cultural plurality, economic vitality, and intercommunal coexistence—qualities that urban modernization has often subdued or replaced. As a result, the project evolved into more than an act of historical documentation: it became a catalyst for cultural reflection, public dialogue within the local communities, and ethical engagement with memory.

In scholarly terms, this study offers a methodological and conceptual framework that bridges heritage preservation, digital humanities, urban studies, and architectural history. It moves beyond conventional preservation to consider intangible dimensions such as lived memory, emotional dimensions, and spatial justice. Its approach—meticulously documenting not only what was reconstructed, but how—provides a valuable roadmap for similar efforts elsewhere, especially in regions where marginalized or minority heritage remains at risk. The project methodology may even offer a practical way for small or diminishing minority communities to preserve cultural memory by documenting what exists today, regardless of the potential for future preservation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the digital reconstruction of Greece’s lost synagogues is not only technically feasible but also intellectually and culturally vital. What began as a response to the physical disappearance of Jewish heritage in Greek cities has evolved into a broader initiative of historical restitution—reconnecting fragmented memory, architectural legacy, and communal identity. Through the combination of long-term fieldwork, rigorous archival research, and the innovative application of digital tools, the project bridges the gap between what has been erased and what can still be remembered, reimagined, and transmitted.

Since its inception in 1993, the project has shown how digital tools in drafting, storing, rendering, and creating 3D models can move beyond documentation to actively restore visibility to sites that have disappeared from the urban fabric. These technologies, applied to both in situ surveys and visual archival materials gathered from institutions and private collections worldwide, have allowed for the detailed reconstruction not only of synagogues surveyed prior to demolition but also of those demolished before the author’s project began. The integration of data from both surviving structures and demolished ones, such as those represented in the Shemtov Samuel archive, has enabled reconstructions with a remarkable degree of accuracy. The methodologies developed throughout this research process have also supported architectural commissions for the physical restoration of historic synagogues, enabling well-informed and sometimes bold interventions grounded in rigorous historical evidence.

Looking ahead, future research could explore more advanced digital tools, such as augmented reality (AR) applications, that would allow users to experience these synagogues in their original urban environments via mobile devices in situ. Additionally, AI-driven architectural reconstruction could explore machine learning to reconstruct lost heritage or refine missing architectural details, thereby enhancing the fidelity of digital reconstruction models. A comparative study with other lost Jewish heritage sites in Europe—such as in Italy, Turkey, or the Balkans—could also offer valuable methodological insights in recapturing the regional wealth of architectural styles, connected through shared traditions.

Equally important are the prospects for deeper collaboration with Greek Jewish communities and descendants of Holocaust survivors. Incorporating oral histories and personal testimonies into digital reconstructions would not only enhance the user’s historical experience but also create a powerful emotional connection between contemporary audiences and Greece’s lost Jewish heritage.

The field of the Greek synagogue studies, substantially shaped and expanded by the author over the past three decades, has entered a new trajectory. Renewed interest in Greek Jewish heritage, alongside the increasing dissemination of new knowledge in publications and exhibitions, continues to bring forth new materials that enriches both academic and public understandings of these synagogues. When combined with new technologies, these developments open new opportunities for study and interdisciplinary experimentation. Digitization not only increases access to this nearly lost heritage but also inspires broader public engagement and encourages the next generation of scholars to continue the work of preservation and recovery.