1. Introduction

The central and strategic role of museums in territorial developments is widely acknowledged by governments and cultural institutions across the world. In the last decade, the efforts of UNESCO for the recognition of the role of culture in sustainable development led to three milestone resolutions adopted by the United Nations’ General Assembly in 2010, 2011, and 2013, which culminated in the integration of culture in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted in 2015 and, particularly, in the SDG11, Target 4 [

1]. The contribution of culture to sustainable development is clearly stated also in other important global framework documents, such as the New Urban Agenda (Quito, 2016) [

2], and confirmed in the G20 Bali Leaders’ Declaration [

3]. The contribution of museums to sustainable development is an essential element also of the agenda of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), as museums “can enhance sustainability and climate change education by working with and empowering communities to bring about change to ensure an habitable planet, social justice and equitable economic exchanges for the long term” [

4].

Under the impetus given by the pronouncements of major international institutions, as well as the global scientific and cultural debate, acknowledging their role as catalyzers, enablers, hubs, or incubators of development in cultural, social, economic, and environmental terms [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] has set on museum institutions new expectations of policy and strategy development aimed at objectives well beyond the mere cultural sphere, pertaining to the social, economic, and environmental development of territories.

The big or outstanding cultural sites and museums are with no doubt drivers of socio-economic growth through the construction, promotion, and maintaining of an identity “brand” and tourist promotion activities, regardless of any close connection with the surrounding context; but is this true also with small municipalities and their less-known museums?

Whereas immovable, built heritage is, in general, unavoidably linked to its territorial component, and involved in development dynamics at least through urban and rural planning activities or adaptive reuse practices, in the case of museum heritages such connections are not as acquired or taken for granted in the literature.

The cultural value of shielded collections, given their potentiality to exert attraction and impacts both on residents and on tourists from all over the world, has a longstanding trend to be considered as an absolute value, regardless of geographic matters and almost ‘above’ them. The new museology [

15] and international reference institutions are now asking museums to be connected with the community [

16], but community is a multitude of actual and potential stakeholders distributed on a territory. If we simply try to invert that relationship and consider a museum as a stakeholder of any part of a community, it is probably easier to trace back this institution within a spatial network and understand how its position on the territory is a compelling feature and how museums can no longer think of themselves and their collections as independent from it.

The EU-LAC “MUSEUM TERRITORY” report [

17], in its focus on the permanent relationship between the community, the territory, and heritage, highlights the importance of the local territorial dimension of museums, proposing an interesting extension of the term ‘museum’ in its definition of ‘museum territory’:

Museum territory: an area that is held together by cultural, environmental, historical, and geographical links, with its heritage resources and elements providing its own distinctive identity.

With the consideration of museums’ “new formats”, the specificity of the museum “building” as a container of cultural objects loses in relative weight, in favor of the central and less exterior concept of ‘territoriality’, meant as a “defined area of cultural and social cohesion”: a value that is not an exclusive prerogative of conventional museums.

Leaving aside any theorization, the mere fact that museums represent the identity of their provenance culture and territory in a modern global context suggests that they should be integrated and considered in their current surrounding and that specific attention should be paid, then, to investigate the character and extent of their actual presence in the surrounding social and productive fabric.

On the one hand, museums enshrine, by their nature, material testimonies of a civilization; on the other hand, landscape is the footprint of that same civilization [

17]. It follows, then, that museums cannot be considered as separate from the territory but rather in natural continuity with it; such continuity must appropriately be reflected also in the visual and digital representation and in the supporting technologies.

In the national contest, many statistical and quantitative studies on museums have been produced, since they traditionally hold a huge importance for Italy in terms of significance and extent, but despite this, geographic studies are curiously missing. Indeed, in the international literature, specific research lines on “museum geographies” have emerged [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], but, based on heterogeneous interpretations of this definition, studies tend to an exhaustive and quantitative approach, with a multifaceted focus that does not include, for example, the relationships of museums with the stakeholders’ groups. Some works, actually, delve into the theme of physical proximity [

23,

24] but considerations remain limited to the strict museum sphere.

In the theorization of the ‘museum territory’, the creation of the territory as cultural product of local development involves actions for the identification and inventorying of major interest resources from the part of key stakeholders [

17]; in the museum territory, then, ‘resources’ are not only the objects kept within facilities, but also those ‘designated’ by stakeholders. Such connotation of the ‘museum territory’ is, on the other hand, fully in line with the Faro Convention [

25], stressing the active role of communities in heritage making.

Moreover, a practical, contingent reason also exists for paying attention to the connection between museums and territories through the relationships with local stakeholders: the growing pressure on the museum sector due to the global reduction in the public financial support of the last decades, forcing museum institutions to concretely prove their efficacy and their impacts on local socio-productive development [

6,

26,

27]. Those pushes are leading museums to experiment with new models of collaboration and interaction with local interest groups and actors, giving life to more and more variegated public–private partnerships.

Against such a changed context and the complex challenges facing museums of today, is the available technological equipment adequate? By virtue of their new mission and the repeated calls for greater inclusiveness and engagement, the existing literature reports a general trend to identify and assess the vitality and the presence of museums in their communities’ life essentially through their online presence [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] and their capability in up-taking the cross-cutting language of ICTs to communicate with their publics. In general, the museum sector is undoubtedly innovating through ICTs; the main objective is anyway the definition of innovative cultural offers with robust digital content for a captivating presentation of collections and immersive and astonishing experiences based on virtual (VR) and augmented reality (AR), ultimately pursuing an increase in visitors’ flows, whether in large or in small facilities. Besides the undeniable benefit of rejuvenating the exhibit of displayed objects, such a trend also brings along the twofold effect of emphasizing the immaterial component of tangible heritage, detaching it from its real context in terms of provenance and conservation places, and prioritizing the individual dimension of the relationship with cultural resources. More generally, remote fruition and distance communication are lending a growing immateriality to both the link with cultural resources (through virtuality) and the relationship with museums (through websites and social networks), emancipating them from the physical component of the interaction place and subtracting from them the richness that the plurality of places and of possible interlocutors can bring.

Moreover, the conviction that every museum is ‘a treasure apart’, unreplicable (as it surely is, at a strictly cultural level), entails the risk of getting to understand ‘uniqueness’ as self-referentiality and self-sufficiency, almost legitimating a sort of self-isolation of museums and their underestimation of their context.

In general terms, the dominant trend towards an experiential cultural consumption, when not supported through the plurality of interlocutors and visions, risks upstaging and delaying the new role expected of museums in the overall development of territories. On a technological level, it has already produced a shift in attention from well-tested and effective technologies for the recognition, visualization, and management of location-based processes in favor of objects’ visualization within customizable digital sceneries. Based on the territorial rooting of local museums, this article aims, then, to focus attention on geographic and spatial technologies, in order to address current challenges facing museums. Its basic research question is, then, the following: can mapping technologies prove useful to understand if and to what extent museums are an active part of the social and productive life of their communities and territories?

The present article aims to answer this question by illustrating, with the help of the graphic representation supplied by basic-level mapping technologies, the results of a survey carried out on a sample of small- and medium-sized archaeologic museums spread over the Puglia region (in southern Italy), investigating the museums’ territorial relationships through the collection of data on their locally partnered events and joint initiatives from the last years. In the following sections, an overview of the system of potential impacts of museums as engines for territorial development is firstly presented, in order to define the scope of the analysis—museums’ relationships with local stakeholders as they emerge from the surveyed events. Then, an outline of the use of mapping technologies in the field of material heritage and particularly in the museum sector is presented. The mentioned survey is then illustrated with a discussion of results, in the form of a showcase of indicative examples. In the final section, further implications of the study’s outcomes are discussed, outlining possible directions for future research.

2. Heritage and Local Development: From Potential Impacts to the Potential of Territorial Relationships

The role of cultural heritage, and tangible heritage in particular, in territorial development is widely acknowledged in scientific debates and at different government levels across the world. Cultural resources’ potential in exerting manifold effects beyond their intrinsic significance as testimony of past civilizations has emerged clearly in the literature for decades. This has led a large part of the research community to move attention from the original mission of museums and heritage institutions—the conservation and communication of knowledge and testimonies of the past, and education on cultural values and meanings—in the effort to systematize and categorize the possible impacts on the comprehensive growth of territories.

During a first phase, from the ’80s and throughout several decades, studies have focused on the economic impacts of cultural resources [

35], and particularly on the more immediate and visible relationship between heritage consumption (with cultural tourism in the frontline) and its direct and indirect effects: revenues from ticket sales and commercial trading tools, cultural tourism, and increase in property values [

36,

37,

38].

In time, especially due to a profound evolution of the functions, roles, and responsibilities of cultural institutions towards their belonging communities, analyses have extended to other impact categories—social, productive [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44], and, later, environmental [

45,

46], sometimes highlighting the strategic nature of important pre-conditions such as participation and stakeholder involvement [

42] and generally suggesting the idea of a continuous enlargement of the observation angle. Indeed, a gradual shift can be observed from a vision focused on direct economic impacts toward the indirect and induced ones, up to including issues relating to well-being, environmental quality, and social equity, as well as a growing attention to the integration of the role of cultural heritage in urban planning, in the direction of an ever-expanding sustainability perspective [

47]. More recently, attention has also extended to participation matters as a consequence of the establishment of social inclusion among the priority issues identified at the programmatic level by major global organizations and policymakers as well as in implemented projects [

10,

48]. Those new calls from heritage institutions have led the research community to wonder also about the effects of CH on local communities’ well-being, with the further, beneficial consequence to bring back in a general sustainability perspective—in some cases critically—as well as the specific links between heritage and tourism and between heritage and employment [

49,

50,

51].

It must be specified, however, that studies focusing on the sole economic impact of heritage are still to be found in the last decade’s literature, highlighting its more variegated and multifaceted nature compared to the past [

52,

53]. In analyzing economic impacts, Piekkola et al. (2014) [

54] focuses on visitors spending within and outside museums as well as on returns in tax revenues and better employment occurring locally, and the Network of European Museum Organizations has put the economic value of museums at the center of its 2016 Conference, with the stated goal of demonstrating to policymakers “the many ways in which museums can influence urban and regional planning” [

55]. Actually, it must be added that the economic dimension of the relationship between heritage and local development is currently regaining the scene also due to several circumstances such as shrinking in public support and in internal budget, which charge heritage institutions, and particularly museums, with stronger pressures and the push to demonstrate their effectiveness as economic growth engines of territories in order to legitimate their demand for governments’ financial support [

56,

57,

58,

59]. Along with those contingent issues, the strategic role of heritage in the economic growth of territories has gained, indeed, a primary importance, in program documents such as the European agenda, focused on specific objectives: identify influence and impact areas, impact measurement, and results’ comparison across territories [

60]. Nevertheless, in spite of this constant, though evolving, attention towards heritage economic impact, existing analysis methodologies do not constitute a routine yet, their application being rather episodic and geographically not homogeneously diffused [

61]. As the ESPON 2020 report [

62] has stressed in its foreword, also in the sphere of purely quantitative economic impacts, marked difficulties still persist in fully catching their real meaning. The lack of standardized data and metrics, as well as shared procedures, highlight the need for a common framework to collect harmonized and comparable data, leaving the theme of impact classification and measurement, substantially, an open question. In such a complex scenario, not immune to methodological and operational gaps, the report identifies three ‘macro’ impact indicators—employment, revenues, and GVA (Gross Value Added)—and eight areas of activities against which they can be assessed: archaeology, architecture, GLAMs (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums), tourism, construction, real estate, ICT, and insurance.

Despite this enduring mono-focus approach in the museum field, studies and deepening from the part of economists towards some specific issues are hard to be found [

6,

63,

64]. For instance, the work of [

63] highlights, against a general background of poor attention to the relationship between museums’ presence and the increase in the surrounding property values, how the effect in terms of desirability of the housing environment and of wage levels is more clearly observed at the local level (at the ‘neighborhood’ level in urban contexts) than at a wider scale. Such a circumstance seems to suggest that, in all probability, in small municipalities, where the presence of a museum institution can hardly remain unperceived by portions of the urban fabric, those effects can have a wider covering, reaching the whole local community. This consideration motivated the selection of the analysis’ scale for the present work.

More integrated, holistic approaches address, instead, the challenge of identifying culture’s impacts beyond the borders of economic benefits, according to different perspectives that look at cultural assets as something much more complex than mere cash flow generators.

a. Part of the existing literature, in the effort to systematize the whole of possible impacts, takes the concept of heritage ‘value’ as a starting point, distinguishing between ‘intrinsic’ (proximity, participation, experience) and ‘instrumental’ (well-being and economic impacts) values; OECD [

65] brings back the latter to the five categories of benefits identified by the Rand Corporation [

66]: cognitive (improved learning), behavioral (development of pro-social attitudes), healthy (therapeutic effects), social (interaction, development of the community’s identity, social capital construction), economic (employment, tax revenues, public expenditure).

The LEM report [

56], aiming to create an overview of research on the topic of museum impacts, tires to capture in a holistic approach all the shades of museums’ contribution, building upon the classifications of cultural value’s components formulated, among others, by Holden [

67] (

intrinsic value; instrumental value; institutional value) and the Netherland Museum Association [

68] (

collection value; connecting value; education value; experience value; economic value).

Many other studies refer to ‘multiple values’ generated by the museums’ activities, proposing possible categorizations [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74], with common components and punctual differences.

Although the cultural debate has not yet reached a punctual and exhaustive definition of the complex of impacts coming into play, and the economic perspective of cultural consumption is steady on the scene, the trend towards holistic and comprehensive approaches to relationships between material heritage and territorial development appears well established in literature. Many studies are to be found that aim to deliver organic and all-encompassing frameworks of possible impacts, while very few shed light on some existing criticalities. Some works underscore how, along with undeniable benefits, a substantial issue relating to the actual and fair distribution of those benefits across the community is also to be considered, a point mentioned anyway also in studies privileging the economic component [

37,

45,

63]. The LEM report [

56], instead, identifies some methodological concern areas relating to the possibility of measuring heritage impacts, namely measurement’s modalities and time horizon. It also points out the opportunity to consider primarily the ways heritage can exert its effects, rather than try to quantify them, lacking any certainty of their actual production. Indeed, many of the mentioned studies address the matter from a potential perspective rather than carrying out measurements [

56,

75].

Another critical point lies in the concrete possibility that, along with positive effects, projects and actions for heritage conservation, promotion, and fruition also have negative impacts, which are not unlikely in the absence of wise and sustainable management. In most cases, such effects are mainly identified in urban areas, affected by over-tourism, gentrification, misplacement of large groups of residents, “museification” of historical centers, increase in housing prices [

76], and the resulting tension between residents and tourists. In the general balance, however, the literature highlights positive impacts outweighing by far negative fallouts in terms of reach and extent.

Overall, it can be stated that a sound consensus exists in the literature about the positive influence of material cultural heritage on the local development of territories.

With specific reference to museums, it has clearly emerged in the last two decades that, beyond their role as carriers of culture, education, and local and national identity, they are, based on different processes and characters, at the heart of regeneration processes of both urban and rural territories [

17,

38,

65,

77,

78,

79,

80]. Differently from general considerations on heritage, the approach of studies in the museum field has mainly focused on social and general sustainability issues [

8,

59,

80].

b. One further observation perspective for the complex task of structuring an exhaustive framework of museums’ impacts on local development is identified, in the literature, in the three-pillar concept of sustainability. In the light of the considerations above, the LEM report [

56] proposes a taxonomy based on the three components of sustainability: (i) economic impacts; (ii) social impacts; (iii) environmental impacts.

Economic impacts: Following the regained importance of the economic component in the evaluation of museums’ impacts, the research community has adopted a wider angle in looking at the effects of museums’ activities as a variegated range of possible contributions to the local economy of a region, in terms of the following:

Employment;

Demand of goods and services;

Multiplier effect on local economies through direct and indirect spending (income and sales);

Attraction of tourist flows and investment;

Place branding;

Influence on real estate markets.

In this articulated scheme, some specific points still remain unclear, e.g., the following:

How museums can contribute to create and train new professional roles;

The possibility to quantify in economic terms possible unpaid labor;

Their actual ability to attract international investments.

In addition, there is the difficulty also to assess the following negative effects and possible offsets:

Rise in real estate values and in rent prices with consequent gentrification effects;

Increase in the cost of living and in taxes for residents;

Rise in the running and maintenance costs of new infrastructures;

Overproduction of waste and garbage, waste of scarce resources [

81].

Thus, these prevent an exhaustive evaluation.

Social impacts: The concept of social impact, in comparison to the economic one, is vaguer and more imprecise, and is susceptible to different interpretations by different social stakeholders. Indeed, this area is not adequately supported through objective data and metrics: shared and tested indicators [

57], unified and reliable templates [

82], and the consensus on the right time horizons to adopt (short vs. long term) are actually missing.

Moreover, museum institutions actually contribute to social development through two channels:

- -

Development of human capital, through learning (individual dimension);

- -

Development of social capital, through participation and the activation of interactions (social dimension).

Each of these, according to interpretations and points of view, can be in turn over-focused against the other.

As a result, the report proposes a matrix of possible social impacts, framed on value perspectives (‘intrinsic/instrumental’) and the nature of beneficiaries (‘individual/collective’) (

Figure 1). The map is shown only to give a hint of the extreme complexity of this impact category; actually, an exhaustive list of social impacts is probably impossible to be drawn, as they are largely dependent on definitions and the subjective nature of interpretations:

Environmental impacts: Environmental issues represent a more recent concern for some institutions that are often addressing them in partnership [

5,

56], as institutions become gradually aware of the importance of environmental challenges, launching awareness-raising initiatives. Guidelines and indications for the reduction of the ecological footprint inside facilities, as well as calculation tools, have been made available in the last decades [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87], but concrete efforts to thoroughly define the whole of impacts—e.g., by analyzing the different museum activities as impact sources in order to adequately support the most conscious institutions—are missing in the scientific literature. Moreover, studies investigating indirect emissions from sources “physically” external to the museum facility or produced through external activities (e.g., collection loans, traveling exhibits, staff and visitors traveling from and to the museum, waste disposal) are hard to be found.

Those gaps seem to suggest a sort of ‘responsibility removing’ from the part of the museum sector, deflecting the liability for environmental impacts on cultural tourism (i.e., travel and accommodation activities to reach and visit the museum), thus relieving museum institutions to a great extent.

In Europe, where the presence of museums is significant, the “Museums in the climate crisis Survey results and recommendations for the sustainable transition of Europe” report by the Network of European Museum Organisations [

88] revealed that, despite the marked environmental awareness and the proactive role in stimulating the public, expressed by the majority of institutions, still few of them, as of June 2022, have elaborated or adopted criteria for the assessment and measurement of their impacts or are consulted in decision-making, and very few are informed about local or national climate policies. The limited financial resources to support those actions represent the main barrier.

The perspective of three-pillar sustainability is also at the basis of other works, focusing on the definition of methodologies aimed at deducing economic, sociocultural, and environmental impacts from users’ (i.e., tourists’ and residents’) perceptions, rather than trying to deliver upstream classifications. The work of Orea-Giner et al. (2019) [

89] is based on a mixed approach, combining established quantitative methods for the evaluation of economic impacts with subjective indicators for the analysis of sociocultural ones, deduced through the attributes of single case studies as identified by expert panels. Another “ad hoc” method, suitable for case-based applications, has been delivered by Bryan [

79], taking the list of services offered by the specific facility as the starting point to derive the possible impacts.

All the considerations above provide a clear picture of the complex task of defining the system of possible impacts and the difficulties still inherent in this domain. Although a reference framework on the theme has not been traced yet, the studies available still allow identifying the range of the stakeholders with which museums have to interact to fully perform their acknowledged role as drivers of territorial development, beyond the representation of local identity and the preservation of cultural objects, and they trigger virtuous networks to boost the growth of their surrounding fabric. In order to assess the actual “presence” of the sample museums in local dynamics, the present study has then scrutinized the partnerships involved in their joint initiatives of the last years, assessing their extent against the resources offered by local contests, to understand if the potentialities outlined in the literature are fully put to good use by cultural institutions.

The system of museums’ internal stakeholders is very complex and includes different professional groups and competences. Nevertheless, the purpose of this article is in examining the connection of museums to their belonging territories; as a consequence, only external stakeholders were considered. Some of them are directly linked to the original and traditional mission of museums (e.g., schools and universities), whilst others can be deduced from the reflections on the different impacts generated by museum activities. The groups considered for the study are as follows:

Cultural sector:

• Museums, museum poles, and networks;

• Heritage institutions;

• Cultural non-profit associations.

Civic sector:

• Citizens (individuals and associations).

Education sector:

• Primary schools;

• Secondary schools (junior high);

• Secondary schools (high school);

• Universities;

• Other education institutions.

Economic and commercial sectors:

• Commerce operators;

• Hospitality operators;

• Tourist operators;

• Trade associations.

Public administrations:

• Municipalities;

• Provinces;

• Region;

• Territorial promotion agencies.

Volunteering:

• Associations for social support;

• Associations for cultural promotion;

• Other associations (temporary or permanent).

For the specific purpose of the study, and in order to adequately support the territorial component of analyses, the representation and interpretation of results have been supported through mapping technologies from the domain of geographic information systems (GISs).

3. Mapping and GIS Technologies in Heritage and Museums

The built heritage, both as cultural, historical, and architectural asset and as current building stock, with its diffused presence across territories, represents an exceptional application ground for mapping technologies, GIS in particular, where the variegated range of goals, actions, and project opportunities ideally match with variegated possibilities coming from those technologies’ features. Indeed, even in terms of mere representation of processes and scenarios, they offer multifaceted potentialities for the construction and visualization of thematic representations of geographically referenced information associated to physical entities with point (buildings, sites, elements of natural or anthropic landscape), line (e.g., roads, railways, rivers, paths), or surface (land use zones, lakes, green areas, buffer zones) geometry, having a specific location.

The possibility to create and visualize thematic mapping applications and to perform elaboration tasks such as complex queries, based on the entities’ attributes, allow users to investigate with extreme versatility both static (e.g., extent and features of an event in a given geographic context and at a given time) and dynamic representations of the studied processes (through a comparison of mapped descriptions at different times), and produce new knowledge through different topological and computational elaborations.

Such flexibility and above all the efficacy in visually returning the state of events or processes—even complex ones—has allowed GIS technologies to find an infinite application ground for a number of purposes related to territorial development, ranging from urban and regional planning to study and research purposes, tourism and cultural promotion, up to the monitoring of building stocks for management and rehabilitation programs. The variety of tasks that can be supported pertain to each phase of territorial development processes (knowledge building, evaluation, decision-making, control, and communication) as they range from the mapping of existing knowledge on a given topic to supporting assessment methodologies (e.g., risk assessment, threshold analysis), to the monitoring of policies’ effects, the elaboration of prevention and mitigation measures, the identification of optimum location or intervention priorities for development actions, up to the elaboration of indications and recommendations.

3.1. Mapping and GIS Technologies for Material Cultural Heritage

Among the possible uses of mapping technologies, the cultural heritage domain has turned out to be one of the most appropriate and lively application fields, giving life to long-lasting lines of applied research. Among all mapping technologies, geographic information systems (GISs) experienced the most consistent and successful development.

One of the first applications in the cultural field, of a pioneering nature, is probably the system developed by the Canadian surveyor R. Tomlinson in 1963, which highlighted its potential strategic nature in many sectors of cultural heritage [

90]. Since then, traditional practices have been progressively and deeply innovated thanks to the possibility to make available, for the different stakeholders involved in the governance of processes, digital platforms for the management of georeferenced multi-format and multidisciplinary knowledge (storing, analysis, elaboration, and sharing of data and derived information), supporting different tasks and facilitating interaction and participation. In Italy, between 1990 and 1996, the ICR (

Istituto Centrale per il Restauro, Central Institute for Restoration) realized the first GIS able to produce an updatable map of the loss risk of the built cultural heritage (MA.RIS.) [

91] for the scientific and administrative support of the state and local bodies in charge of heritage preservation. Actually, at the end of the ’90s, a wide spreading of GIS in the public administrations of the country could be observed [

92].

As Liu et al. underline [

90], in time the integration of GIS in the conservation of cultural heritage has been establishing itself as a continuously evolving and expanding pragmatic focus, with a stable growth at the level of practical applications even now. For decades, many authors have been acknowledging the potentialities of GIS and exploring the application progress in the field of built heritage through accurate reviews [

90,

93,

94,

95]. These studies highlight how applications have mainly privileged the goals of census campaigns of immovable assets for the set-up of “digital atlases” or archives supporting the task of knowledge organization for documental needs of heritage sites’ and buildings’ managing authorities. More specific purposes of planning and operational management of conservation projects—sometimes together with tourist promotion objectives—prevail instead in a large portion of case-based studies in the literature, referring to disparate geographic contexts [

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102]. Overall, a conscious use of GISs for the knowledge, understanding, preservation, and management of heritage has assigned them a more and more central role in the sphere of cultural resource conservation.

A specific field where mapping technologies have rapidly earned a wide space is the domain of archaeological studies, where the vital need to support the documentation and cataloguing of findings matches the equally important range of possibilities for the study, reconstruction, and visualization of the context and the landscape surrounding the findings’ sites. This application area is particularly long-lasting and consolidated—the first numerous applications appeared already at the end of the ’90s—and has led over decades to the establishment of a consistent and constantly growing international R&D line, due to its potential in supporting spatial analyses [

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110]. The main focuses of studies are heritage knowledge, management, and protection, but investigations in the field of promotion of heritage as tourist product are also numerous [

111,

112,

113].

Moreover, the suitability of GISs to integrate with other IC technologies has revitalized and enriched their use in the latest applications developing innovative solutions, above all the integration with three-dimensional modeling (3D GIS), the modeling of information on building objects (HBIM, Heritage Building Information Modeling), sensor networks and drones [

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124], as well as virtual and augmented reality (VR–AR) [

111,

125].

Overall, both in the specific application to archaeology and in the more general sphere of cultural heritage, the available reviews underline how Italy proves to have provided the largest contribution in terms of scientific studies [

95,

108].

The three emerging trends identified in the work of Liu et al. in the sector—sustainable conservation strategies for preserving the authenticity of damaged or obsolete heritage; proactive conservation models and preventive maintenance through 3D data and digital models; enhancement of public engagement through participation GIS (PPGIS) models—shed light on a considerable growth potential of practical applications, suggesting an increasing integration of technical issues of heritage conservation with the ‘spatial humanities’ perspective [

90]. In this suggested context, the integration capabilities of GISs with the mentioned ICT represent a key element.

3.2. Mapping and GIS Technologies in Museums

Initially, the application of the ‘mapping’ concept to the museum sector has mainly constituted the basis for profiling studies on user groups and actual as well as potential ‘publics’. Consistently, the use of spatial and GISs in museums has focused on supporting visit flow analyses [

126,

127], alongside objects’ cataloguing and geo-referencing activities, in order to correlate the information produced by qualitative research to specific geographic positions [

128].

Considering the ongoing evolution in museum institutions and in the definition of their new mission, much more complex and multifaceted compared to the past, the support offered by GISs and, more generally, by mapping technologies is even more precious due to their features and capabilities, in terms of both representation and information analysis and elaboration. Undoubtedly, they still keep an irreplaceable role in the locating of findings and evidence, supporting the recording, study, and interpretation of objects for research purpose. Nevertheless, their usefulness goes well beyond the research field and extends also to communication, management, and internal organization tasks, offering useful work tools to a variegated group of users, both internal and external to museums: institution managers and collection curators, scholars, volunteers engaged in the running of facilities, and staff. Actually, on a potential level, the literature has tried to outline the different potential uses of mapping technologies in the museum sector. The work by Dorter underscores how GISs can support museums in all their functional areas: collection management, collection design, exhibition, education, administration, and institutional cooperation [

129].

Nevertheless, differently from the general spreading of geographic information systems in the cultural heritage domain, part of the literature agrees that in the museum sector this technology is still underutilized [

130]. More precisely, its large potential appears as not fully understood; actually, scientific studies grasping those potentialities at a practical level are very few. Considered the gaps existing in official lists of institutions, often failing to detect new museum categories [

131], even the mere existence of museums would greatly benefit from exhaustive mappings of facilities in the territories, with descriptive and access information. Some interesting initiatives in this regard have been carried out, for example in the UK [

18]. Also, for the other mentioned museum activities, case studies and practical solutions are hardly found in the literature. In addition, the everlasting, intriguing challenge to connect the local dimension of narratives on material heritage with the intrinsic goal to convey the identity of the belonging region to a global audience, which long ago emerged on a theoretical level [

132], has made the usefulness of geographic spatial technologies evident without generating specific experimentation lines that could make the most of them.

Recent applications of mapping technologies to museums mainly aim to support the following:

- -

The increase in remote or on-site access to collections and in general engagement, in the form of analysis and visualization tools for collections [

130,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137], sometimes with the use of specific features such as storymaps for virtual exhibits [

138];

- -

Exhaustive digital documentation of museums’ buildings as ‘containers’ of collection for heritage protection and conservation purposes [

96,

139,

140].

A loss of attention can be observed, in the last decades, towards the study of visit paths through indoor spatial analysis, the visual optimization of objects’ placement, and the analysis of visitors’ flows [

127,

141,

142,

143,

144], despite the ongoing impulse toward the study of tracking methods and technologies in the museum sphere that could greatly benefit from an integration with GISs due to their computing capabilities and query features also in a predictive perspective [

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151].

Beyond the academic field, indeed, a growing direct commitment of museum facilities in GIS-based projects has been observed in the last decade [

152]. Regardless of the specific functional use, it must be noticed that the spreading of GIS across museums is not uniform; some institutions currently arrange digital maps of the whole facility to be used during on-site visits, and others make very little or no use at all of those technologies for any of their tasks. The main barriers are to be found in the lack of financial resources for technical training and license purchase, but also in a limited awareness of the range of their potential uses, exactly for the wide versatility of technologies, which make a clear and customized identification of the optimum application areas unavoidable [

130].

Overall, whether the focus is on the study of the museum publics or on the fruition of collections, the use of mapping and GIS technologies remains at the moment mostly bound to a ‘single museum’ perspective (most applications in the literature consist in “a museum’s GIS”). The approach adopted does not pay attention to the local context and its components, except for the relationship with real or potential ‘visitors’, showing a ‘closed’ and exclusive character. Studies that take into consideration institutions with their territorial connections, within and outside the strict museum sector, from a geographic perspective are missing. The analysis by Gardner [

135], focusing on major global museums’ heritage, allows to highlight how GISs greatly support studies on the global distribution of collections, in order to investigate historical and political implications of the interactions with their provenance countries, thanks to their capability in managing huge amounts of data. On the other hand, it also stresses the impossibility for the big data involved to keep trace of the more or less controversial history of each single object and to prevent the loss of data, due to the great number of possible database attributes related to the subsequent locations of objects and to the need to proceed by data aggregations [

135]. This seems to suggest the greater adequateness of mapping and GIS technologies for local dimensions.

Overall, apart from census mapping, the literature has mainly explored “internal” uses of GISs in museums, looking at the public as simple museum visitor rather than as territorial interlocutor. Actually, despite the essential territorial component of the processes it represents, this spatial technology is used far below its potential, giving priority to the single-building scale and limiting to tourist promotion purposes the consideration of other surrounding institutions for the planning of visit itineraries, as well as almost totally ignoring the other stakeholders of local development.

Such an ‘isolated’ vision of museums is no longer consistent with their new mission that puts them at the heart of local processes and assigns them also new social and economic roles, as explained in previous sections. In the effort to contribute to fill this gap, the present article focuses on mapping technologies’ use expanding the view to the “museum/publics/stakeholders” local system. The study aims to investigate the contribution that mapping can offer in assessing the actual “living” presence of museums in the local socioeconomic and productive fabric, through the relationships with other reference entities in the territories. Taking a sample with a marked nature of spatially ‘distributed’ heritage (the archaeological museums of the Puglia region, southern Italy) as the case study, the article presents a mapped representation of a questionnaire-based survey of museums’ territorial relationships established for the organization of recent joint initiatives.

Aside from the computing and elaboration capacity of geographic information systems, this article aims to identify a new application field for mapping activities at their basic level and to understand possible implications, taking into account time and skill requirements and the difficulties of small- and medium-sized local museums.

In particular, the goal of this paper is not to illustrate a single and complex elaboration, but rather to show how some specific issues, eluded by large-scale statistical surveys or reports on single facilities, can be instead easily identified and represented by availing their geographic component through mapping technologies, thus allowing museums to obtain a clear picture of their presence in the territory and conveniently orientate their decision-making also with limited resource effort.

4. Materials and Methods

As has emerged in the literature, against the impossibility to identify and measure the whole of real impacts of museums on local development, considering the potential nature of those impacts and focusing on the ways those impacts can be generated appears a more feasible task. This implies shifting the attention to the system of connections and relationships that can activate impact generation, in order to assess whether museums implement, in their outreach practice, adequate partnerships that really reflect the whole of components and resources of territories, mobilizing them for local development. The ultimate purpose of this work is in assessing whether mapping technologies can aid and support such investigation.

Assuming that the joint events’ partnerships and stakeholders’ engagement can be a reliable representation of museums’ active participation in the different sectors of local communities and territories, the work intended to assess if the museums’ actions strategically make the most of the resources locally available.

In this view, the methodology proceeded through the following steps:

Questionnaire-based survey across the sample museums, aimed at scrutinizing recent joint initiatives and events as to the features and composition of the involved partnerships; the questionnaire, handed out to museums’ managers, represents the main data source for the study (primary data) (further detailed in

Section 4.1);

Recognition of the main local resource systems existing in the museums’ territories from documental sources, in order to obtain a comprehensive representation of museums’ local contexts and identify the main potential resources available for local development, based on museums’ proximity to them (secondary data) (described in

Section 4.2);

Elaboration and mapping of data (described in

Section 4.3):

- -

Elaboration of charts on ‘macro’ level issues from questionnaire data;

- -

Geo-localization and thematic mapping of the resource systems within a basic geographic information system (GIS);

- -

Geo-localization and thematic mapping of events’ partnerships in the GIS, based on their actual position in the municipal, district, or regional territory.

Comparison, for each museum, of the characters (e.g., nature and localization) of involved partnerships with the complex of their respective potential resources on a case-by-case basis, in order to assess the coherence between the relationship systems and the resource systems. The assessment was performed, in particular, by examining the performance of each institution as to the richness and multidisciplinarity of partnerships (Query A) and the richness of local resource systems (Query B), which allowed to single out noteworthy cases out of the screening of all sample museums (described in

Section 5: Results).

The study upholds that the results of such a ‘geography-based’ assessment methodology, by delivering more in-depth and context-related knowledge compared to the simple statistical analysis of questionnaires, prove the usefulness of mapping technologies in assessing the geographic extent of museums’ partnerships and their actual consistence with the local socioeconomic and environmental fabric, thus answering the research question.

4.1. The Survey on Museums: Aims and Design Issues

The consideration of the articulated impacts that the museum sector exerts on the cultural, social, and economic fabric of territories led to focus attention, at the planning stage, on the analysis of the web of links existing in the museums’ operational activities with a variegated group of local stakeholders. The scope of the study was identified, then, in the relational systems of museums, analyzed through the joint initiatives or events carried out by museums together with their partners in the last five years, in order to understand to what extent museums are rooted in the socioeconomic fabric as an integral part of their territories’ life.

A previous study [

153] already analyzed the attitude of institutions towards museum networking in the same region; the results showed that regional museums do not rely on collaborations among institutions for addressing thematic or managerial issues on an ongoing basis, and even in the COVID-19 outbreak the possible advantages associated to museum collaboration were not really grasped by the managers. The present study anyway included museums and heritage institutions in the group of possible stakeholders.

At the time of writing, specific studies focusing on the Apulian museum field, as either descriptions of individual experiences and virtuous examples, or extended reviews at the regional scale, are not available. Widening the gaze, many studies on national, European, and worldwide institutions are based on direct interviews with museums’ directors, yet not addressing the topic of territorial relationships.

Considering the time and staff shortage issues expressed by managers, one-to-one direct interviews were shelved in favor of the questionnaire option, as this modality allows interviewees to better manage the collection of data and the compilation of initiatives’ cards. Studies sounding out the structural topic of museums’ role in a specific geographic and administrative context in this particular acquisition modality are missing in the international literature, as well as in national reports; thus, a dedicated questionnaire was specifically designed.

Supported by the mentioned outcomes of Sheppard [

63] about the spatial extent of museums’ presence effects and the findings of Štefan [

154] and Saotome [

155] about the local nature of community involvement and the role of small museums as agents of development, the study mainly focused on facilities located in small- and medium-sized municipalities, without however overlooking larger museums.

4.1.1. The Sample

In order to maintain a ‘narrative’ continuity with the previous study on museums’ collaboration and communication, the sample museums were initially identified in the same group of facilities.

The cultural landscape of Puglia is dominated by the presence of archaeological museums and sites, representing the majority of total institutions. They were, then, chosen as the representative sample, adding also museums from different reference categories hosting other archaeological collections, e.g., civic or ethno-anthropological museums (“primary category”) with an archaeological section (“secondary category”).

The initial geographic distribution of the selected museums across the region’s provinces substantially reproduced the actual geographic distribution of the total consistence. The region’s overall museum heritage is extremely diffused in the territory, with the majority of facilities located in municipalities, even in very small ones, rather than concentrated in the main cities. The sample is, then, characterized by a small-to-medium dimension, with medium-sized museums located in province seats and small ones in minor municipalities. As for the governance forms, municipal as well as private museums were included, together with a few state museums.

Of an initial list of 32 institutions participating in the previous study, 20 museums took part in the present survey. Data sources used for the definition of the sample consist of relatively dated works, in particular a printed guide by [

156] dating back to 2006, a 2013 study on regional museums and collections [

157], the constantly updated website of the Regional Directorate for Museums (for state museums), the “Cartapulia” database (an interactive platform based on a geo-referenced mapping of sites of cultural interest, elaborated by the Puglia Regional Administration) [

158], and the search on the Internet (keywords: “museum” + “archaeologic” + “puglia”).

Almost all responding museums pointed out the very limited time available for the participation in the survey, and the impossibility to return datasheets for all the initiatives performed, due to their commitment in ordinary activities and the reduced staff available.

Another issue was related to the heterogeneous functioning in the museums’ management. Some of the museums could rely on a substantial continuity in the management throughout the period considered for the survey (the last five years), whilst others experienced interruptions or temporary closures, which did not allow carrying out systematic planning and performing activities. Turnovers in the management roles also contributed to complicate the data sourcing on past running for directors and managers currently in charge.

4.1.2. The Questionnaire

Museums from the selected sample were handed out a questionnaire; the chosen modality was the sending through email of questionnaires in fillable module pdf format, fast and easy to use for almost anyone, together with a brief description of the research purpose as the reason for the invitation, together with direct telephone calls to solicit participation and offer support for compiling or further information. Museum directors and managers were asked to focus specifically on joint initiatives carried out in the last five years together with other operators from the museum sector as well as from other professional fields (e.g., schools, universities, educational institutions, cultural associations or centers, public administrations or agencies, professional associations, firms and manufacturers, trade associations, and others) at the municipal, district, and regional level. In a few cases, collaborations in the national or international scene were also mentioned by managers.

The questionnaire was mainly structured with open questions in relation to descriptive data about the museums’ joint initiatives or events (title, matter, location) and the partnering stakeholders, and also to collect the managers’ perceptions and evaluations about the events. Data about the target publics and the indoor/outdoor nature of events were obtained through close-ended questions.

The questionnaires’ main topical areas were as follows:

- (A)

Events;

- (B)

Stakeholders involved;

- (C)

Geographic location issues (museums, stakeholders, events);

- (D)

Roles and public participation level.

The museums’ managers were asked to fill in one data sheet for each initiative and could decide how many events to screen based on their evaluation of the events’ significance as well as on their time availability. In particular, specific questions addressed issues such as name and nature of public and private stakeholders involved in the initiatives, location of the stakeholders involved and of initiatives, subject or title of events, date of events, nature of events’ intended beneficiaries, and public engagement level. Open-ended questions about the subjective evaluation of the added value of events were also included.

4.2. The System of Local Resources

Extending the view from the events and initiatives to the local dimension and context of sample museums (

Figure 2), it is possible to obtain further important information. A thematic mapping of territorial resources was carried out for different local contexts. Given the exemplifying character of the work and the peculiar wealth of cultural, productive, and naturalistic elements (each deserving further deepening in dedicated studies), a selection of the most significant features was made.

The sample museums were located in the territory; then, the resources of the region were identified and categorized as follows:

Cultural resources: Officially formalized museum networks; ‘minor’ heritage; official cultural itineraries; the ancient Messapian “Dodecapolis”;

Identity landscape resources: The territorial premises identified by the Regional Territorial Landscape Plan (PPTR) and the Heritage Atlas;

Environmental and naturalistic resources: Biodiversity resources; historical rural landscapes; the Monumental Olive Trees system;

Production resources: Typical products;

Production resources: Manufacturing and industrial districts;

Production resources: Tourism districts;

Institutional resources: Municipal unions.

Along with conventional territorial resources, also quite recent administrative models such as the unions of municipalities, some having anyway very ancient roots, were included in the concept of “resource” for their capacity to support joint actions for local development in any sector.

For each resource, the position (geographic coordinates) for point-type ones, as well as extent and boundaries (for those resources covering whole municipal territories), were obtained from textual information, to be subsequently traced in the GIS. The purpose of this phase was to build the visual representation of the resource patrimony characterizing uniquely each of the municipalities hosting the sample museums.

The systems of local resources examined in the study and their detailed mapping in the GIS are exhaustively described in

Appendix A.

4.3. The Elaboration and Mapping of Data

In the responses’ elaboration phase, all data and information collected were processed in a twofold procedure. First, all data were used to obtain charts related to macro-level issues (topics’ distribution, events’ location, public’s role, museums’ orientation). Then, the open-ended responses were categorized in order to obtain a finite number of field values and used, together with close-ended responses, to build attribute tables to be associated to the shapefile entities representing the sample museums and the involved partnerships in a GIS environment based on open-source software (QuantumGIS, version 3.34 “Prizren”). A specific phase was dedicated to the construction of the system of territorial resources available to each of the sample museums and relevant for the study, through the elaboration of vector information layers.

For some territorial resources, digital data available in the Territorial Information System of the Regional Administration [

159] were acquired. For others, the consultation of textual documental sources represented the starting point to draw ad hoc georeferenced delimitations. Some design choices were made to better reflect the scope of the study:

- (a)

Only those resources specifically present in the territories of museums’ hosting municipalities were mapped, whilst the resources available across the whole regional territory were not considered: it is the case of some typical products, and of some material cultural resources from the built heritage with a marked distributed nature;

- (b)

Among the numerous productive districts established by regional regulations, only those deeply rooted in the identity of reference municipal territories were considered.

Finally, the two resulting series of shapefiles—those related to the mapping of events’ partnerships and the ones representing the local resource systems—were matched against each other, in order to examine the resulting overlapping.

5. Results

5.1. First ‘Macro’ Results from the Questionnaire Analysis

Prior to the mapping of museums’ partnerships, the questionnaire’s responses allow deriving some important information. It must be noticed that museums’ managers delivered their responses according to their respective time and data availability, thus returning a heterogeneous number of event cards. As a consequence, whenever useful and possible, numerical values were calculated—and are presented in the following—as referred both to the number of sample museums and to the number of total reported initiatives. An initial quantitative screening returned the following results (for a more fluent writing, museums will be referred to through the name of their hosting municipality instead of their full name).

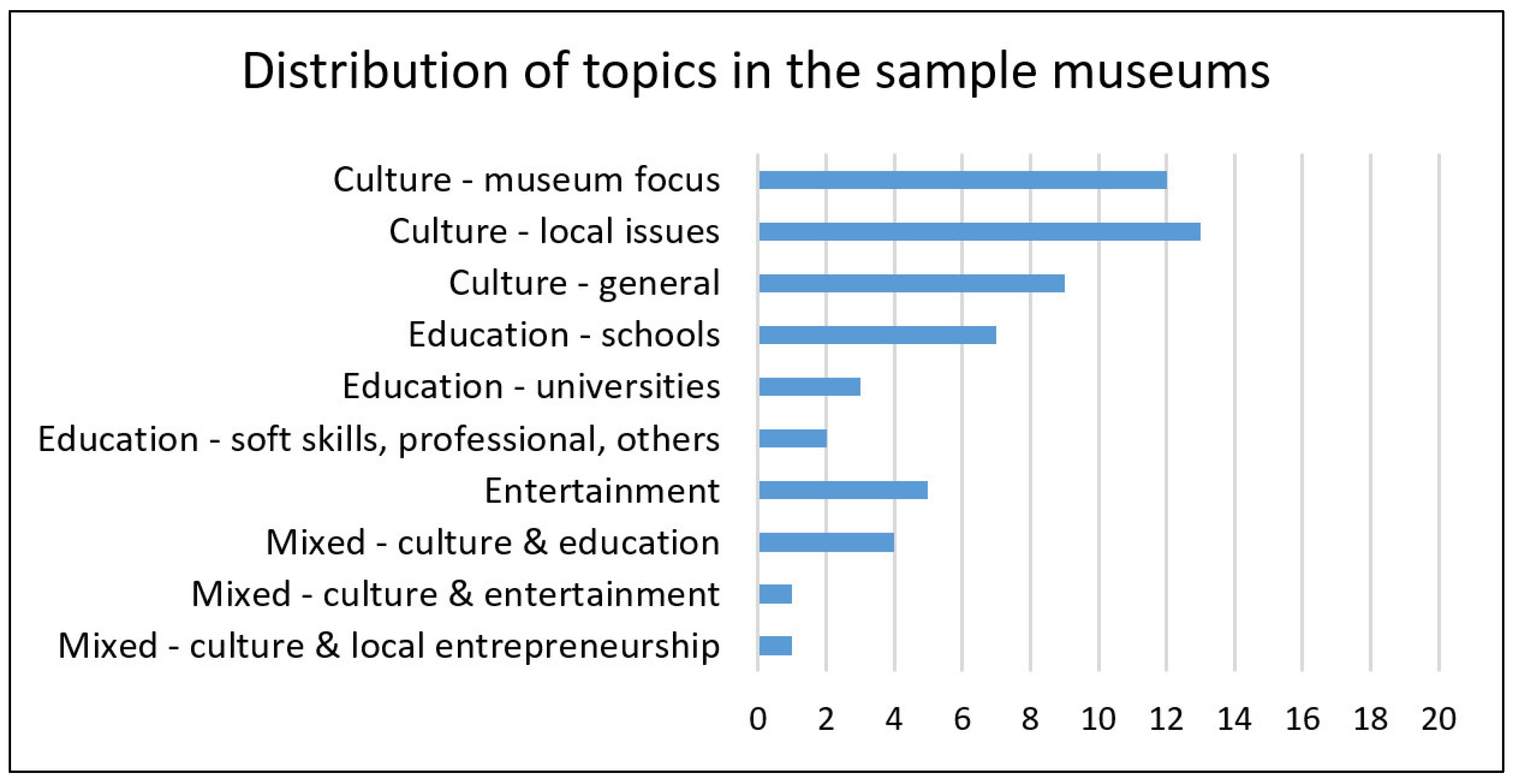

Initiatives reported by museums feature a wide range of topics. In the cultural sphere, collection-based events are largely overcome by initiatives focusing on general culture (23.48%) and themes of local interest (13.91%), as well as by the segment of entertaining events (25.22%). Overall, events strictly related to formal educational activities (university or school internships, study visits, etc.) included in curricula account for 13.05% of the whole number, and only 6.09% of initiatives pursue mixed purposes (

Figure 3).

As for the distribution of those topics across the sample museums (

Figure 4), culture-related events involve the highest numbers of institutions; in the educational sector, school activities are more popular than those included in university study plans. Only a few museums dedicate attention to less traditional themes such as professional training or soft skills (10%) or combine cultural purposes with entertainment or support to local entrepreneurship. Overall, the data confirm a steady orientation of museums towards their traditional mission in the transmission of cultural values and education (

Figure 5).

With reference to the public’s role in the surveyed initiatives, their engagement as mere visitors or spectators definitely prevails (67.83%) on a more direct and active one (32.17%); although such traditional orientation towards mono-directional communication is confirmed, the number of museums adopting a flexible approach on a case-by-case basis is not negligible (30%).

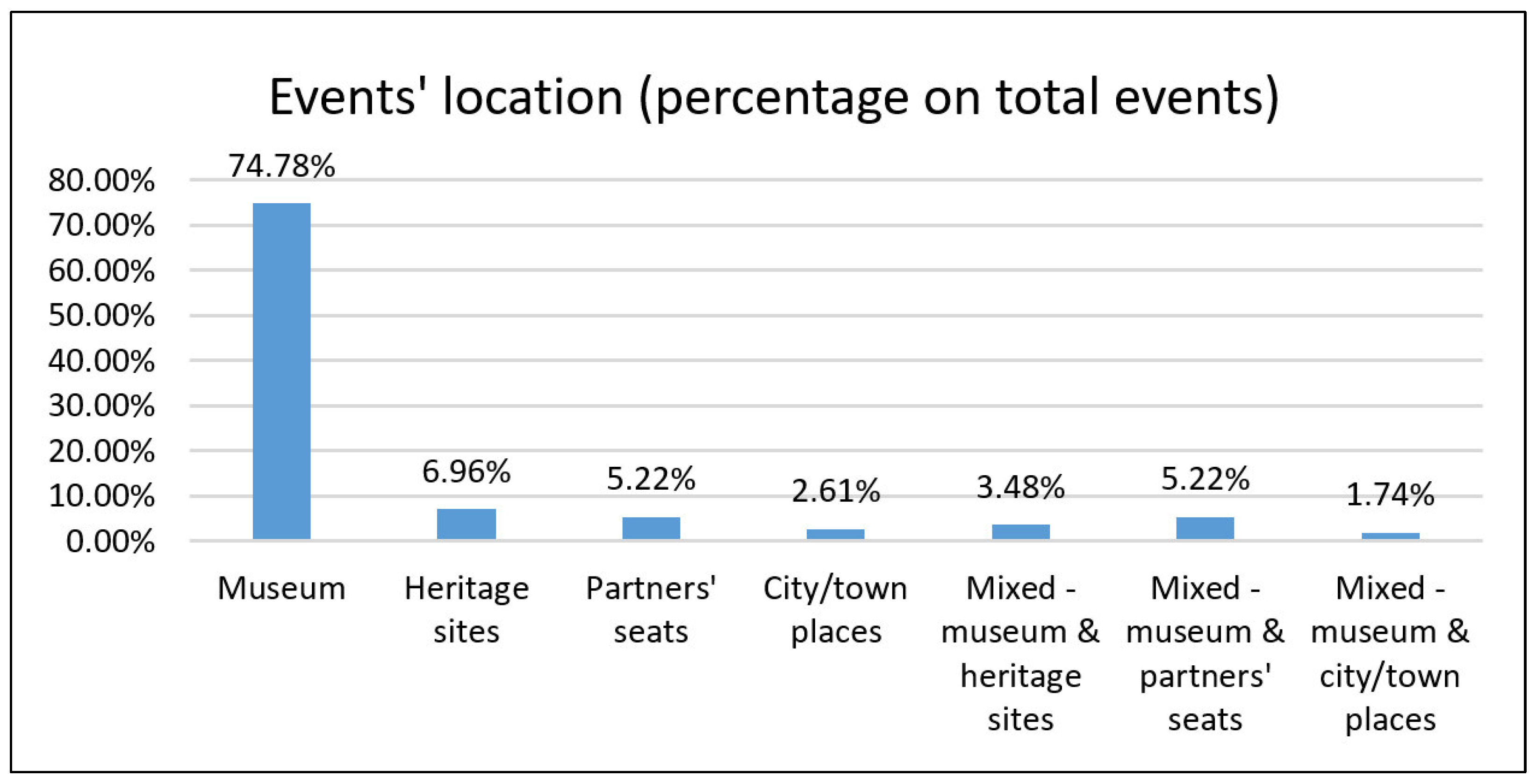

For the scope of the analysis, it is interesting to observe how, despite some openness towards themes of wider interest for the local community and not strictly connected to museums’ collections and contents, the location of reported initiatives is mainly the “museum” as physical place or, in lesser cases, other heritage (e.g., castles, churches) or ‘representative’ (e.g., partners’ seats) sites (

Figure 6). Interest towards other urban places of the local communities’ everyday life appears rather negligible, except for a few original initiatives engaging the surrounding urban fabric for the revitalization of commercial activities and public spaces.

Actually, one main limitation lies in the very few data supplied by some of the interviewees; as a matter of fact, museum managers responded by transmitting the information related to those initiatives considered by them as more indicative of their activity and role. The results obtained, then, are more useful for a general assessment of the museums’ prevailing orientation, rather than for an exhaustive evaluation of all initiatives in the region. In particular, differently from the other issues mentioned above, an evaluation of the distribution of partnering stakeholders referred to the total number of initiatives would be biased through the heterogeneity of the number of initiatives reported by each museum, making the calculation poorly indicative. For this reason, this issue was only referred to the number of museums, in order to draw indications about their prevailing outlook.

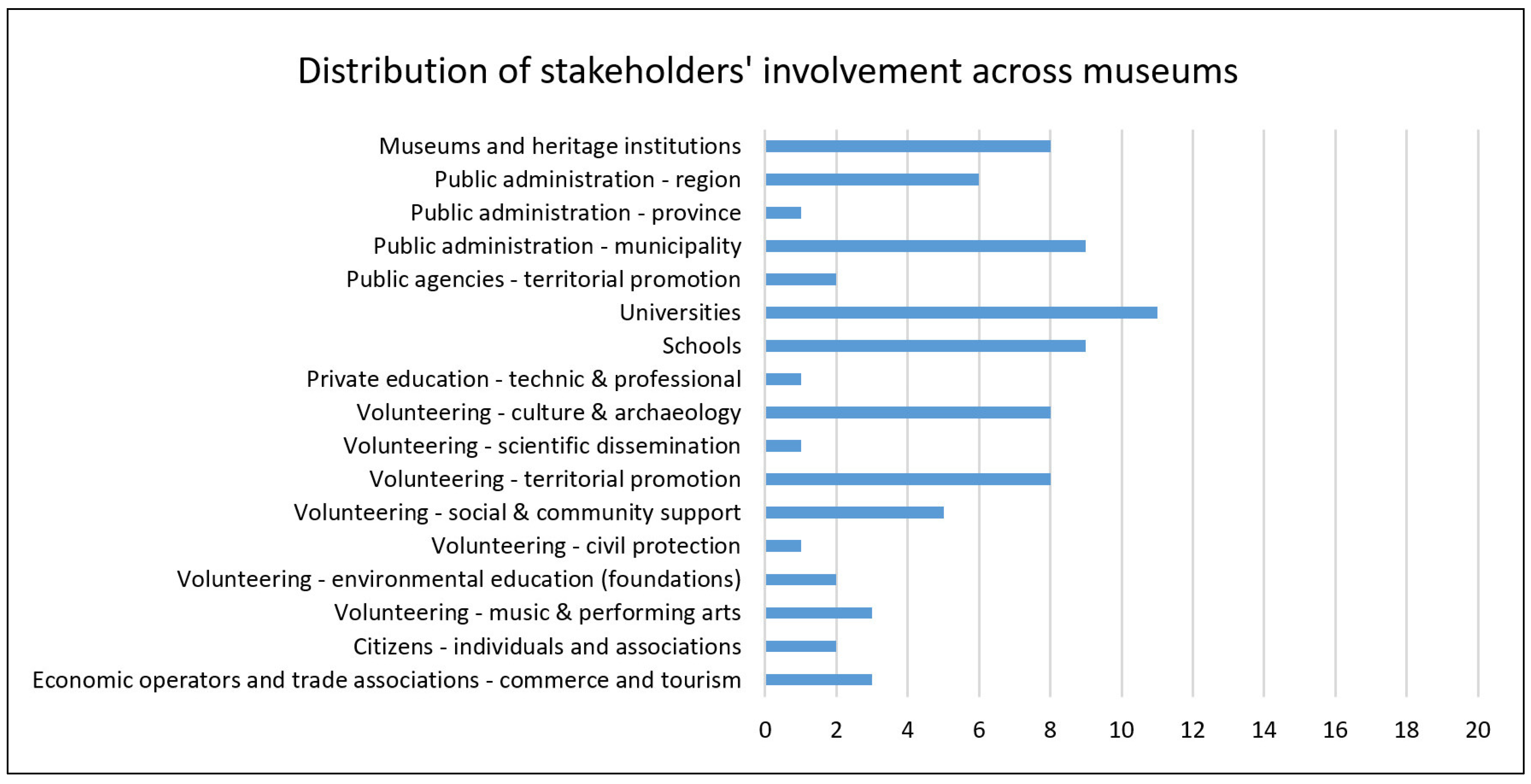

The stakeholders’ categories involved in the museums’ joint initiatives were identified as follows:

Museums and heritage institutions;

Public administration—region;

Public administration—province;

Public administration—municipality;

Public agencies—territorial promotion;

Education—universities;

Education—schools;

Education—technical and professional, soft skills;

Volunteering—culture and archaeology;

Volunteering—scientific dissemination;

Volunteering—territorial promotion;

Volunteering—social and community support;

Volunteering—civil protection;

Volunteering—environmental education (foundations);

Volunteering—music and performing arts;

Citizens—individuals and associations;

Economic operators and trade associations—commerce and tourism.

From the analysis of partnerships’ articulation according to their provenance sectors, a general trend towards a traditional vision of museums as representative places of cultural values and education emerges—with more or less elitist perspectives—mainly privileging contacts with universities and schools, together with other museums or heritage institutions, and volunteering in the fields of archaeology and territorial promotion. Overall, 16 out of 20 museums feature such a trend through one or more relationships of that nature. Stakeholders from the social, economic, and environmental domains are involved only in a small number of cases (

Figure 7).

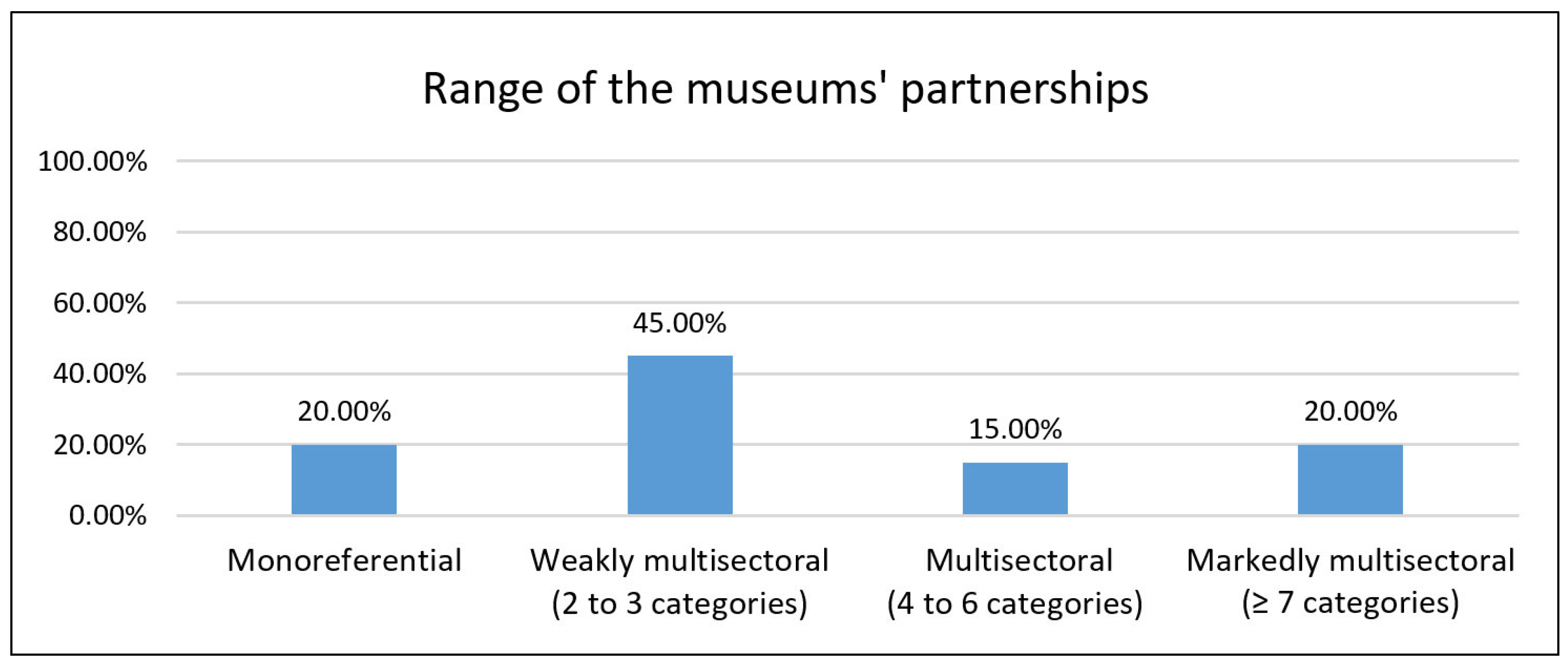

Based on the more or less articulated composition of museums’ partnerships, four groups of museums were identified (

Figure 8):

Mono-referenced museums (only one type of partner): They interact with a preferential type of stakeholders—other museums, universities, or schools—substantially suggesting a traditional view of the institution as a depositary of cultural resources and values and as an educational place; local public administrations are missing (four out of 20 museums: Bari, Mesagne, Nardò, Poggiardo, accounting for 20% of the sample).

Museums with weakly multisectoral partnerships (two to three types of partner): Still anchored to their traditional mission, they indicate a limited engagement of the volunteering sector and a generic inclination towards collections as resources for the promotion of the territorial identity, without specific interest for other potentialities; their partners are generally from the heritage, educational, and institutional sectors, with the regional administration as privileged institutional interlocutor (seven out of 20 museums: Altamura, Bitonto, Bovino, Castro, Calimera, Francavilla Fontana, Vieste, 45% of the sample).

Museums with multisectoral partnerships (four to six types of partner): Although they maintain a traditional vision of the museum’s mission (in some cases from an elitist perspective), they show a more appreciable involvement of local volunteering organizations, distinguishing themselves through a certain openness towards specific issues (e.g., social issues or local economic development); the relationship with local administrations is almost equally distributed between the regional and the municipal levels (four out of 20 museums: Gravina, Latiano, Manduria, Trinitapoli, 15% of the sample).

Museums with markedly multisectoral partnerships (seven+ types of partner): Their complex partnerships and a conspicuous presence of volunteering associations from different sectors of local communities’ life, often prevailing on other relationships, support a greater openness and a definite connection to specific aspects of a “bottom-up” social, environmental, and cultural sustainability. With a greater heterogeneity compared to the other three groups, museums still anchored to a ‘one-way’ transmission of knowledge coexist with examples of a novel orientation towards an ‘entertainment’ function, through the engagement of performative arts (theatre, music, dance, readings) in the effort to enrich traditional museum roles as places of community aggregation, and of a specific and factual attention towards local productive development. The public’s engagement in initiatives is also variegated as visitor and as active participant in the dialogue with stakeholders in events and laboratory activities; the privileged institutional interlocutor is the municipal administration, except for a single museum markedly oriented to international performances (five out of 20 museums: Cutrofiano, Fasano, Lecce, Molfetta, Muro Leccese, 20% of the sample).

Overall, the numerical data extracted from the questionnaire responses allow assessing one first distinction with reference to the degree of multidisciplinarity and inclusiveness of museums’ joint initiatives, and of their actual openness towards the different sides of the communities’ life. Nevertheless, they do not allow assessing the actual connection of museums to their context if that information is not linked to local territories, which deliver further knowledge and tell what quantitative data do not reveal. Apart from the strategies adopted, some points arise: do partnerships reflect all the potentialities offered to museums by their local contexts? Are museums making the most of the resources that territories have to offer? In other words, are the partnerships built by museums consistent with their real positioning?

5.2. Museums and the System of Local Resources: General Results from the Thematic Mapping

The contextual consideration of museums’ localization and the system of potential available resources, based on their mutual proximity, allowed to assess that museums do not generally make the most of local resources when conceiving joint initiatives and building the relevant partnerships.

Cultural resources: Considering the whole of cultural resources described, the participation of sample museums in the ‘networked’ cultural resources appears rather limited:

Only two museums from the sample (in the municipalities of Trinitapoli and Bovino) participate in the ‘Altapulia’ museum network, and only one out of the 52 museums of the ‘Altapulia’ network features as a partner in reported initiatives;

Only two museums from the sample (Bari and Molfetta) participate in the ‘Terra di Bari’ network, and only one out of the 26 museums of the network features as a partner in reported initiatives;

Ten museums from the sample (Calimera, Castro, Cutrofiano, Lecce, Muro Leccese, Nardò, Poggiardo, Francavilla Fontana, Mesagne, Manduria) participate in the ‘Salento’ museum network, and only four out of the 64 museums of the network feature as partners in reported initiatives;

Overall, 14 of the 20 sample museums are formally included in official museum networks, but less than six out of the 144 museums of the networks feature as partners in reported initiatives;

A total of 50% of the 20 municipalities hosting the sample museums (Bari, Altamura, Bitonto, Bovino, Gravina, Fasano, Mesagne, Francavilla Fontana, Lecce, Manduria), plus the hosting municipality of one of the partnering museums (MAR-TA, the Archaeologic Museum of Taranto), are part of the designated itineraries; nevertheless, none of the reported initiatives relates to one of those routes;

The sample museums’ hosting municipalities include the ancient Dodecapolis cities of Mesania (now Mesagne) and Mandyria (now Manduria), but no reference to that specific heritage is explicitly made in the reported initiatives.

Identity landscape resources: Reported initiatives do not represent the belonging of museum institutions to those systems with such ancient origin: partnerships do not generally include administrations or other stakeholders from the municipalities of the same territorial and socio-productive premise and initiatives do not generally address those identity values.

Environmental and naturalistic resources: Overall, 13 out of the 20 municipalities hosting the sample museums (Altamura, Bari, Bitonto, Bovino, Castro, Cutrofiano, Fasano, Gravina, Manduria, Mesagne, Molfetta, Vieste, Trinitapoli) are included in (or adjacent to) those premises, very important in naturalistic, environmental, and cultural terms, given their central presence in the ancient world. Nevertheless, the surveyed initiatives do not generally report efforts to connect museums’ collections to those territorial resources in a wide-scope narrative, able to enhance them by engaging their stakeholders for knowledge purposes, for the recovery of local identity and skills, and for socioeconomic development.

Production resources: typical products (olive oil, wine, agrifood): Despite the particular significance of these products for the ancient and present identity of the region, and the many possible connections with the other local resource systems, the surveyed museum activities do not report, in general, any initiative extending its focus from the strict archaeologic themes to this territorial resource system in search of connections across different sectors of the community’s productive life. That would instead represent an important bridge between today’s communities and the system of ancient identity values, while at the same time enriching with deep-rooted contents and significances the image of local production, increasing domestic and international visibility. Indeed, the possible declinations in the promotion of those products in global markets, and their implications in terms of exportation volume, are numerous: health and well-being, “Made in Italy”, gastronomy, Mediterranean diet (UNESCO intangible cultural heritage of humanity).

Across a large majority of the museum sample, reported partnerships do not include any economic operator, and the events’ topics do not mention those products, neither in pure cultural terms nor in terms of integration with social issues, knowledge recovery, or professional, entrepreneurial, or tourist growth.

Production resources: manufacturing and industrial districts: The Municipality of Fasano is the core of a production area strongly characterized and identified through its toponym (stone of Fasano–Ostuni), gathering 208 businesses, three universities and research centers, 34 institutions, trade associations, and labor unions, three private associations, eight service suppliers, and counseling agencies (see

Appendix A for details). Actually, no event among the reported initiatives refers to this potential resource or involves reference stakeholders from this sector.

Production resources: tourism districts: As of now, two Territorial Tourist Systems (STTs) have been formally acknowledged by the regulations: the “Puglia Imperiale Federico II” and “Sud Salento” systems. Despite the structural and strategic importance of STTs, and the relative proximity of many hosting municipalities (Trinitapoli, Castro, Muro Leccese, Poggiardo) to the most appealing coastal tourist areas, the reported initiatives do not mention a direct involvement of the STTs’ stakeholders (except for Cutrofiano, which will be further addressed).

Institutional resources: The sample museums’ initiatives do not feature the involvement, from the part of museums, of the other municipalities from their respective unions (also, in this case, the Museum of Cutrofiano is an exception).

Once tracing, in broad outline, the system of territorial resources available to museums to activate their potentialities as engines of local development, it was cross-checked with the data on the partnerships’ composition and location, connecting the latter to their context of action in order to assess their consistence.

5.3. Comparison of Local Resource Mapping with Museums’ Partnership Characteristics

The thematic mapping’s overlapping of sample museums with the local resource systems allows to identify those museums that are located in contexts marked by a greater or lesser richness in potential resources and stimuli, but it is, then, necessary to assess if that richness is perceived and incorporated within the sphere of museums’ actions, represented by the range of stakeholders involved in joint initiatives. The study has based this phase on two queries:

- -

Query A: what are the sample museums with the most or least multidisciplinary partnerships? (

Table 1);

- -

Query B: what are the sample museums with the richest contextual resources? (

Table 2).