1. Introduction

Australia prides itself on being environmentally aware, and globally and intra-nationally, it promotes itself as being amongst the refined global community of the environmentally conscious. Historically, Australia appeared to be in the vanguard in environmental consciousness. For instance, it was one of the first nations to inscribe a large National Park,

viz., The Royal National Park in 1879 [

1] it was one of the first countries to become a Contracting Party to the Ramsar Convention (1971) [

2] (an inter-governmental treaty to protect wetlands globally,) and designated the world’s first Ramsar site, Cobourg Peninsula, in 1974 [

3], one of the earliest signatories to the World Heritage Convention (1972); and it is the only country in the world to enact specific domestic legislation that sets out the powers and responsibilities of the national government under the

World Heritage Protection Conservation Act 1981, as amended by the Conservation Legislation Act in 1988 [

4] and now protected under the

Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) [

5] However, as resource exploitation and population increased, there were pressures on land uses as well as economic and political pressures to maintain national employment levels, as the nation as a whole and the average Australian family pursued national and individual wealth, respectively. Consequently, cracks appeared in this façade of environmental consciousness.

Recent developments at the international, national, and State levels exemplify this, for example the initial refusal of Australia to sign the Kyoto accords in regard to controlling CO

2 emissions using its economy and national employment issues as the rationale. The World Heritage Committee, at its last meeting in June 2013, expressed concern for the Great Barrier Reef [

6,

7] and requested Australia ensure that the property remains well-protected Other examples include the dismantling of the (National)

Environmental Protection of Biodiversity and Protection Act (EPBC Act 1999) [

5] to give state governments responsibility for both the assessment and final decision to approve projects with impacts on nationally significant environmental matters (this gives rise to potential conflict of interests where the protection of Australia’s national heritage may be compromised to benefit State economic policy and development interests); the degradation, threatened delistings, and partial urban and canal estate development of numerous internationally significant Ramsar-listed sites throughout Australia (e.g., the Becher Wetlands and Peel-Harvey Wetlands in southern Western Australia, and the Coorong Lagoon in South Australia.

In the arena of geoheritage, the establishment of Australia’s first, and only, globally listed Geopark, Kanawinka, was met with criticism by agencies of the federal government who, in 2013, blocked the annual Global Geopark Network (GGN) assessment of Kanawinka, which has now been delisted by the GGN, and opposes the establishment of any future global geoparks [

8]. There are currently no geoparks, and innumerable counter-environmental decisions are regularly undertaken by development-oriented governments against well-articulated pro-environment data and information (e.g., oil and gas development is proceeding in a globally significant rock art archaeological area in the Dampier Archipelago oil and gas development in a globally significant coastal zone in the Dampier Peninsula, north of Broome Western Australia, amongst others) [

9].

Often, when there is a conflict of environmental (resource) values, development-oriented political decisions are taken in spite of the provision of well-publicised and well-informed cultural and scientific environmental data and information to contest the environmental assessments underpinning pro-developmental proposals and environmentally adverse decisions. In addition, political decisions are taken where the public and qualified scientists were not afforded the opportunity to contest the process or the decision making (e.g., the port facility at Cape Preston or the solar salt ponds at Onslow, both in coastal northern Western Australia).

Apart from a few examples, such as the Gordon below Franklin Dam debate in the 1960s and 1970s, and the old growth forest logging debate in southern Western Australia (a 30-year debate, culminating in the Regional Forests Agreement in 2001), only few of the environmentally adverse conflicts in Australia have been documented as ignoring or dismissing independent scientific evidence in favour of advice by pro-development consultants who put forward theoretical “solutions” to manage environmental issues. Often ill-informed and human elements underpin the decision making (where, for example, computer modelling software is used in preference to using existing fieldwork-generated scientific data and information, or taking the time to ground truth or obtain information upon which to design a development), the historical unfolding of an environmental conflict, and the economic or political bases to the [

10,

11]. As such, the details of the arguments and the core knowledge of scientists, community groups, and pro-environment agency office-bearers, contrasting with the ultimate political decision, more commonly are lost to the public and formal scientific literature and, during the conflict, generally were reduced to a series of media comments and perhaps editorials. Primary data and information in letters and reports now held in government office archives are lost to the public and forgotten. All that remains is the fact that the conflict to protect the environment in a particular area was entirely or partially lost.

This contribution records the history of the Boronia Ridge urban development, in Walpole, SW Western Australia, Australia, and its associated waste water treatment development in the mid to early 2000s in terms of the primary planning and urban structure, the planning and implementation of sewerage infrastructure against a background of the natural history of the region, the environmental significance of Boronia Ridge, and the data and information made known to the politicians and decision makers at the time of the conflict in an attempt to avert the proposed development.

We provide this case study of the destruction of a unique hilltop wetland, as an example of the ethics (and of course the implied lack of ethics) and, more specifically, geoethics involved against a backdrop that industrialised, urbanised, and overpopulated global communities elsewhere largely view the Australian continent from afar as one of the last remnant wildernesses in the world, and one where it is assumed that there is care exercised within Australia to protect what is essentially considered to be global assets. What we intend to show, in this case study, is that, at the planning level, firstly, there is generally little or no effective or legal protection offered for globally, nationally, or state-wide or regionally significant environmental assets and, more specifically, for natural heritage features (of geology, geoheritage, and biodiversity) and secondly, in this case study, that government agency personnel have no regard for data and information provided by internationally recognised experts in their field when it conflicts with development interests.

2. Materials and Methods

Brocx (2008) and Brocx and Semeniuk (2007) [

1,

12] provided a semi-quantitative method to identify and assign levels of significance to geoheritage features. The levels of significance and their criteria for identification are as follows: (1) international—one of, a few of, or the best of a given feature globally; (2) national—though globally relatively common, one of, or a few, or the best of a given feature nationally; (3) State-wide/regional—though globally relatively common, and occurring throughout a nation, one of, a few of, or the best of a given feature state-wide or regionally; and (4) local—occurring commonly through the world, as well as nationally to regionally, but especially important to local communities.

A range of field and laboratory methods were used in this study. Wetlands were identified using Semeniuk and Semeniuk [

13,

14]. Stratigraphy and soil sequences were determined by coring, augering, excavating pits, and the examination of cliff exposures [

15]. Hydrology and hydrochemistry were studied by monthly monitoring of water levels and water sampling in arrays of piezometers along transects [

15]. The details of vegetation mapping and floristic determinations are provided in Semeniuk et al. [

15]. To specifically document and determine the precise boundary between the upland/dryland and the palusmont at Boronia Ridge, independent experts were invited into the study; Professor Pate (formerly Head of the Department of Botany, University of Western Australia) and Dr Meney, both botanists and co-editors of and contributing authors to the book on Restionaceae [

16], undertook field ecological and laboratory histological and anatomical studies into the rhizomatous response of wetland and dryland species of Restionaceae and Cyperaceae to the conditions of waterlogging and soil moisture in order to better define the upland/wetland boundary and the upland to wetland transition zone. Details of their methods are contained in Syrinx Environmental P/L and Pate [

17]. Finally, to resolve the issue of whether the surface material blanketing Boronia Ridge was

in situ saprolite or a sedimentary deposit (a matter that became important to explain why groundwater was being perched under Boronia Ridge), Dr Glassford (an independent geomorphologist and pedologist) was invited by the V & C Semeniuk Research Group for WANISAC to undertake a granulometric and petrographic study of the surface materials of Boronia Ridge. Dr Glassford obtained samples in the region of undisputed saprolite, undisputed sedimentary material, and a range of material from the shallow stratigraphy of Boronia Ridge and compared them granulometrically by sieving and petrographically/microscopically to determine mineralogy. The reports with details of the methods by Syrinx Environmental P/L and Pate and Glassford [

17,

18] are housed by The Wetlands Research Association [

19] in the Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia, Australia.

Definitions

The wetland terms used in this paper that readers may not be familiar with are [

13,

14] as follows: palusmont—a seasonally wetted hilltop, after

palus, the Latin for ‘marshy’, and

mont, the Latin for ‘mountain’ or ‘hill’; paluslope—a seasonally wetted slope; slopemire—a permanently waterlogged slope, the term is derived by combining ‘slope’ with ‘mire’, the latter derived from Middle English (from old Norse ‘myrr’) for a wet, soggy, or marshy ground.

WANISAC is the acronym for the ‘Walpole and Nornalup Inlets System Advisory Committee’, a formal community committee brought to existence and authorised by the local government (the Manjimup Shire) to investigate and advise the Shire on environmental matters in the region and especially on the estuary of the Walpole and Nornalup Inlets.

3. Regional Setting and Study Area

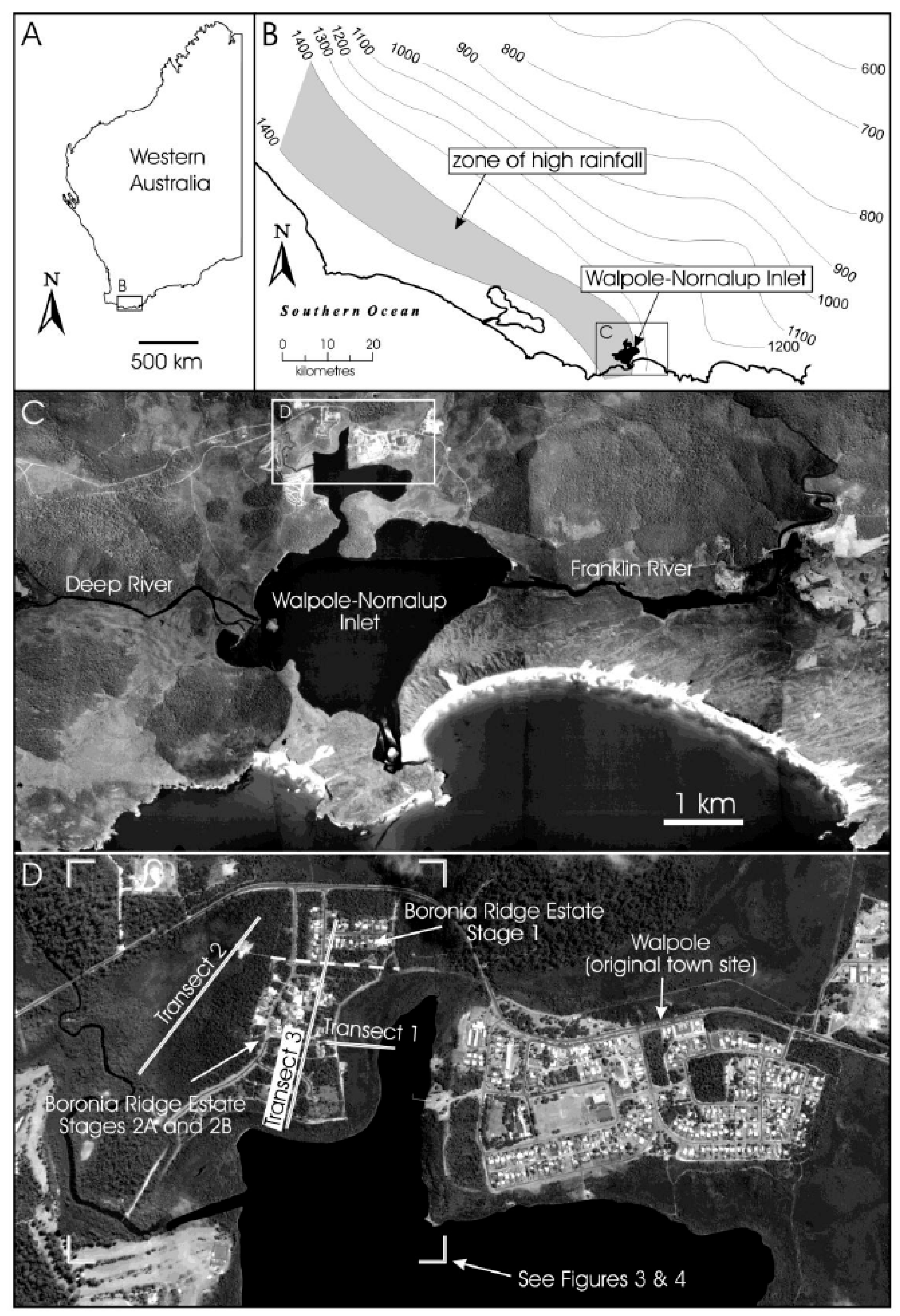

Walpole is a town in Western Australia, 432 km SSE of Perth and 66 km west of Denmark (latitude: −34°58′44.40″ S, longitude: 116°43′40.80″ E). The Boronia Ridge palusmont and its vegetation association occurring in the region of Walpole is unique in Western Australia, due to a number of factors as follows: (1) Precambrian granite/gneiss complex cropping out in this region along the Western Australian southern coast [

20]; (2) deep weathering of the granite/gneiss forming thick saprolite that can act as an aquatard to perch infiltrating meteoric water [

15]; (3) the occurrence of Boronia Ridge in the wettest part of Western Australia with 1400–1600 mm annual rainfall and low evaporation (

Figure 1); (4) the occurrence of a sheet of coarse to very coarse sand of tertiary age (the Walpole Sand) blanketing the granite/gneiss saprolite throughout the region [

15]; and (5) the terrain around Walpole consisting of dissected plateau and high relief hills and knolls, with the uplands being mantled by outliers of the Tertiary sand.

Because of the high rainfall, wetlands in the Walpole region occur in a variety of landscapes, from low-land valley floors and channels to basins and plains, to hill slopes and hill crests on the uplands. The focus in this paper is on wetlands in the hill-capping and hill slope settings.

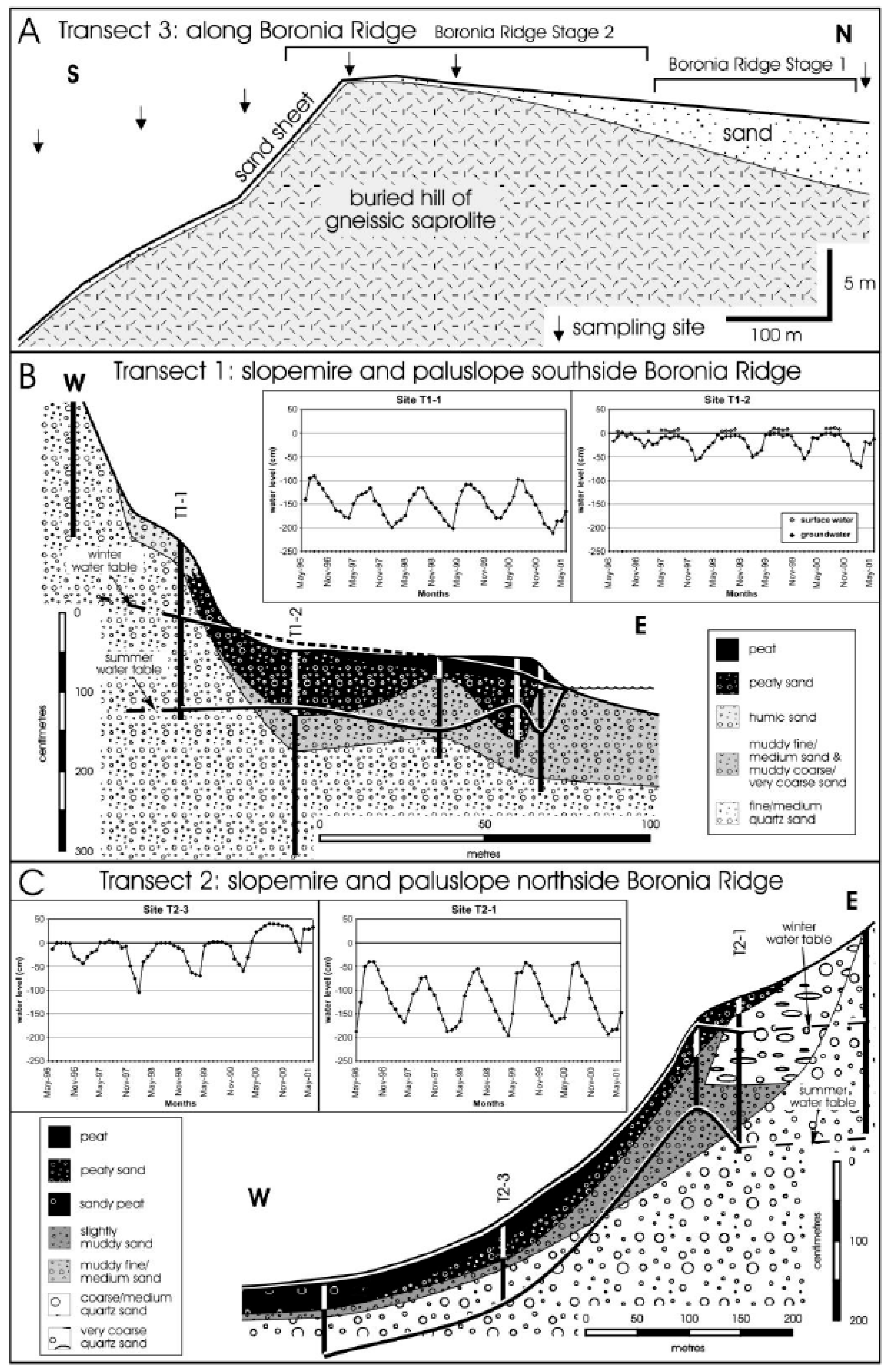

The reason there is a wetland hill environment (palusmont) at Boronia Ridge is that the combination of sand overlying the saprolite that is developed on the granite/gneiss complex acts to perch infiltrating rainfall. The stratigraphy and hydrology of the Boronia Ridge palusmont is shown in

Figure 2.

Rainfall infiltrating the tertiary coarse and very coarse sand perches on the relatively less permeable saprolite and the tertiary sand acts as a high-level aquifer. During winter, the groundwater rises to form a groundwater mound under the high ground of Boronia Ridge; as such, the water table of the perched groundwater rises to the ground surface or proximal to the ground surface to form waterlogged soils, i.e., a wetland. From this groundwater mound, groundwater discharges towards the lowlands that border Boronia Ridge (

Figure 2). As a result, the slopes bordering Boronia Ridge are wet slopes (or paluslopes and slopemires), whose groundwater is maintained by direct rainfall and by discharge from the groundwater mound under Boronia Ridge. These wetlands develop peat substrates, a feature unusual for slope wetlands in Western Australia [

15]

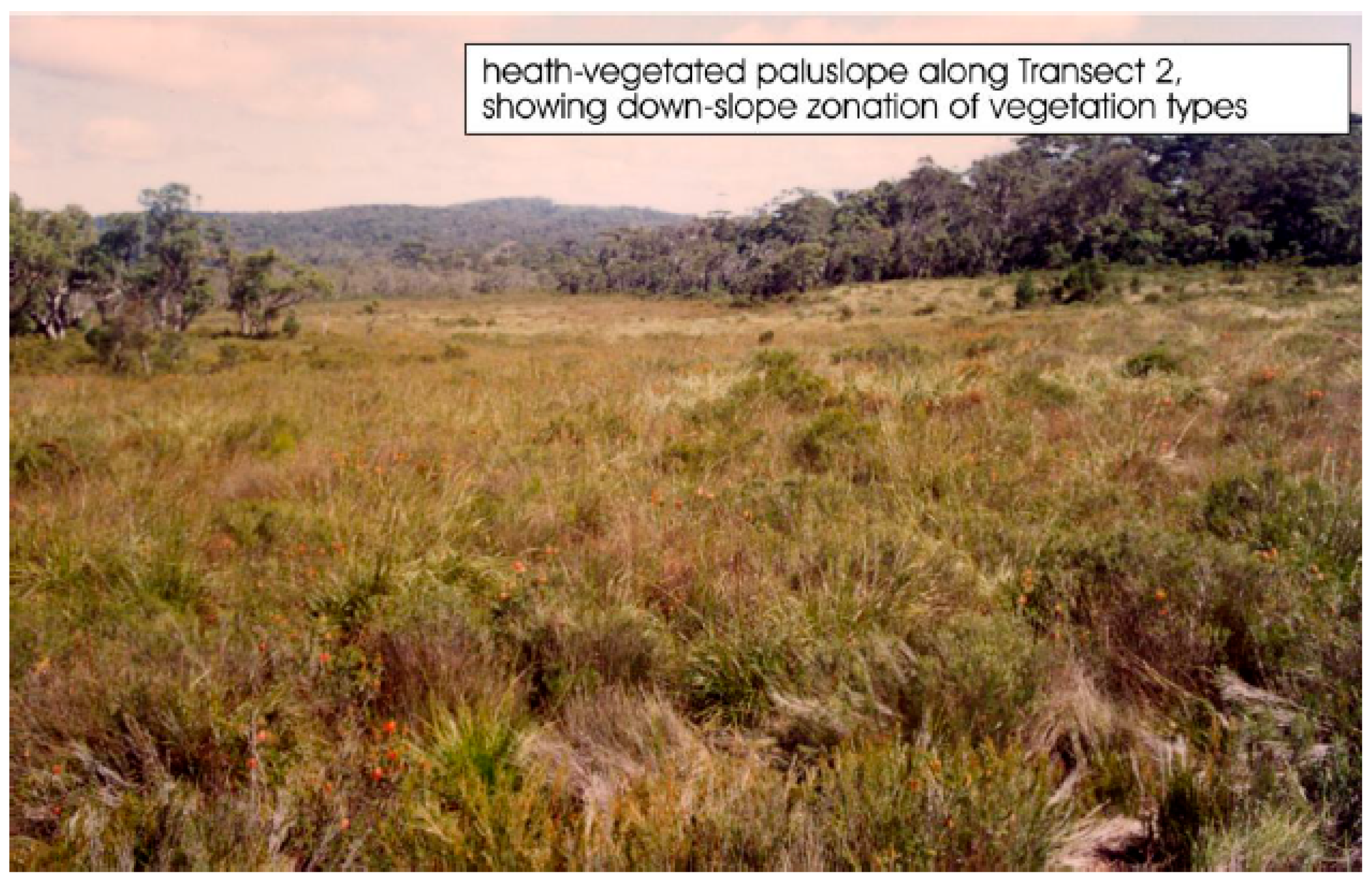

The Walpole area resides in a biogeographic region of high floristic biodiversity,

viz., the Warren Botanical Region, comprising some 490 species of flowering plants and representing a biodiversity ‘hotspot’ globally [

15,

21]. Consequently, there is a unique and unusual vegetation and floristics in the Walpole area around Boronia Ridge in relation to the types of landforms, stratigraphy, soils, and hydrology. Of particular interest is the vegetation of heath, sedges, and rushes that inhabit the wetland slopes bordering Boronia Ridge. Here, where the paluslopes/slopemires are underlain by peat, there is an assemblage dominated by a heath of

Astartea laricifolia,

Beaufortia sparsa, and

Homalospermum firmum and by sedges and rushes, such as

Empodisma gracillimum,

Evandra aristata, and

Taraxis grossa, amongst others [

15]. There is also the occurrence on these wetland slopes of the ancient sedge

Reedia spathacea, a Gondwanan relict endemic to humid southern Western Australia and the Walpole region (

Figure 3). Where the

Reedia is sufficiently abundant, the combination of vegetation formation and its associated peat soils have been termed a ‘

Reedia swamp’. There are two swamps that maintain

Reedia in the Boronia Ridge area; to the east, there is the slopemire with

Reedia occurring in the upper slopes, and to the west, there is an extensive occurrence of

Reedia inhabiting a broad basin-like paluslope and slopemire.

As a Gondwanan relict, and formerly inhabiting wetlands during the tertiary era when southern Australia in its northerly global migration after its split from Antarctica was further south in a very wet temperate climate [

22,

23,

24],

Reedia spathacea as a relictual plant today prefers quite wet environments. Consequently, it occurs in the high-rainfall zone of southern Western Australia and specifically occurs in the wettest habitats therein. When viewed regionally in terms of its patchy, sporadic, and specialised occurrence, it is considered to be a rare plant. Because of its Gondwanan history, its primitive sedge features, and its rarity,

Reedia spathacea has been recorded on the listing of the EPBC Act as wetland sedge of national significance.

3.1. The Significance of Boronia Ridge, Adjoining Wetlands, and the Reedia Swamps

Using the criteria developed by the Australian Heritage Commission (1990) [

25] generally to evaluate geological and biological heritage features, ie, features of natural significance, and by Brocx (2008) and Brocx and Semeniuk (2007) [

1,

12] to specifically evaluate geoheritage features, the palusmont of Boronia Ridge, as well as the paluslopes and slopemires bordering Boronia Ridge, are determined to be of national significance. Using the criteria of the Australian Heritage Commission (1990) [

25] to evaluate biological features, ‘

Reedia swamp’ bordering the south side of the palusmont of Boronia Ridge specifically is determined to be of national significance. Of particular importance is the stratigraphic–hydrological relationship of the ‘

Reedia swamp’, slopemire, and paluslope bordering Boronia Ridge in that part of the water budget, which maintains these slope wetlands and their specific vegetation associations, deriving from discharge from the groundwater mound under Boronia Ridge. As such, the Boronia Ridge uplands and the adjoining wetland slopes to the south side act as a geomorphic–stratigraphic–hydrologic–ecologic ensemble of national significance. The geoheritage evaluations of ‘

Reedia swamp’ on the south side of Boronia Ridge, the slopemire, and the paluslope and ‘

Reedia Swamp’ on the north side of Boronia Ridge using Brocx (2008) and Brocx and Semeniuk (2007) [

1,

12] are presented in

Table 1, and using the AHC (1990) criteria [

25], in

Table 2.

The current Australian Heritage Commission (AHC) [

25] criteria for the Register of the National Estate provide for the nomination and listing of sites illustrating geological, landform and soil features, and processes. The national estate is defined in

the Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975 [

26] as “those places… that have aesthetic, historic, scientific or social significance or other special value for future generations as well as the present community”. However, reference to the national estate criteria and perusal of the list of places already listed indicates that a broader interpretation of national estate values has usually been taken, often with consideration of biological and other ecological aspects of a particular site during the assessment process.

In developing criteria for selection of areas for Register on the National Estate, the AHC achieved several outcomes. It defined criteria in medium qualitative detail to capture features that might be of national heritage significance, including the attributes of diversity, the maintenance of existing regional processes, the maintenance of regional natural systems, rarity, historic value (natural and cultural history), representativeness of a range of landscapes, environments or ecosystems, and scientific value. The criteria for the selection of area for the Register on the National Estate by the Australian Heritage Commission are listed as four main types [

25]:

Criterion A: Importance of an area or site in the course, or pattern, of Australia’s natural or cultural history;

Criterion B: Possession of uncommon, rare, or endangered aspects of Australia’s natural or cultural history;

Criterion C: Potential of an area or site to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Australia’s natural or cultural history;

Criterion D: Importance of an area or site in demonstrating the principle characteristics of (i) a class of Australia’s natural or cultural place; or (ii) a class of Australia’s natural or cultural environments.

Using the criteria of the Australian Heritage Commission (1990) [

25], the Boronia Ridge palusmont and its adjoining wetland slopes, and the ensemble of groundwater mound and its relationship to the wetland slopes, also qualify as nationally significant.

3.2. The Drive for Urbanisation in the Boronia Ridge Area—Its Entrepreneurial Underpinning

Walpole resides in the heart of tourism in southern Western Australia. It is the gateway to the giant old-growth karri forests, the Denmark treetop walk amongst the karri canopy, impressive coastal scenery, diverse wildflowers in a biodiversity ‘hotspot’, boating, and fishing. While it is an old settlement, and it has not grown substantially as a town for decades, entrepreneurial developers saw Walpole as an ideal place for urban expansion.

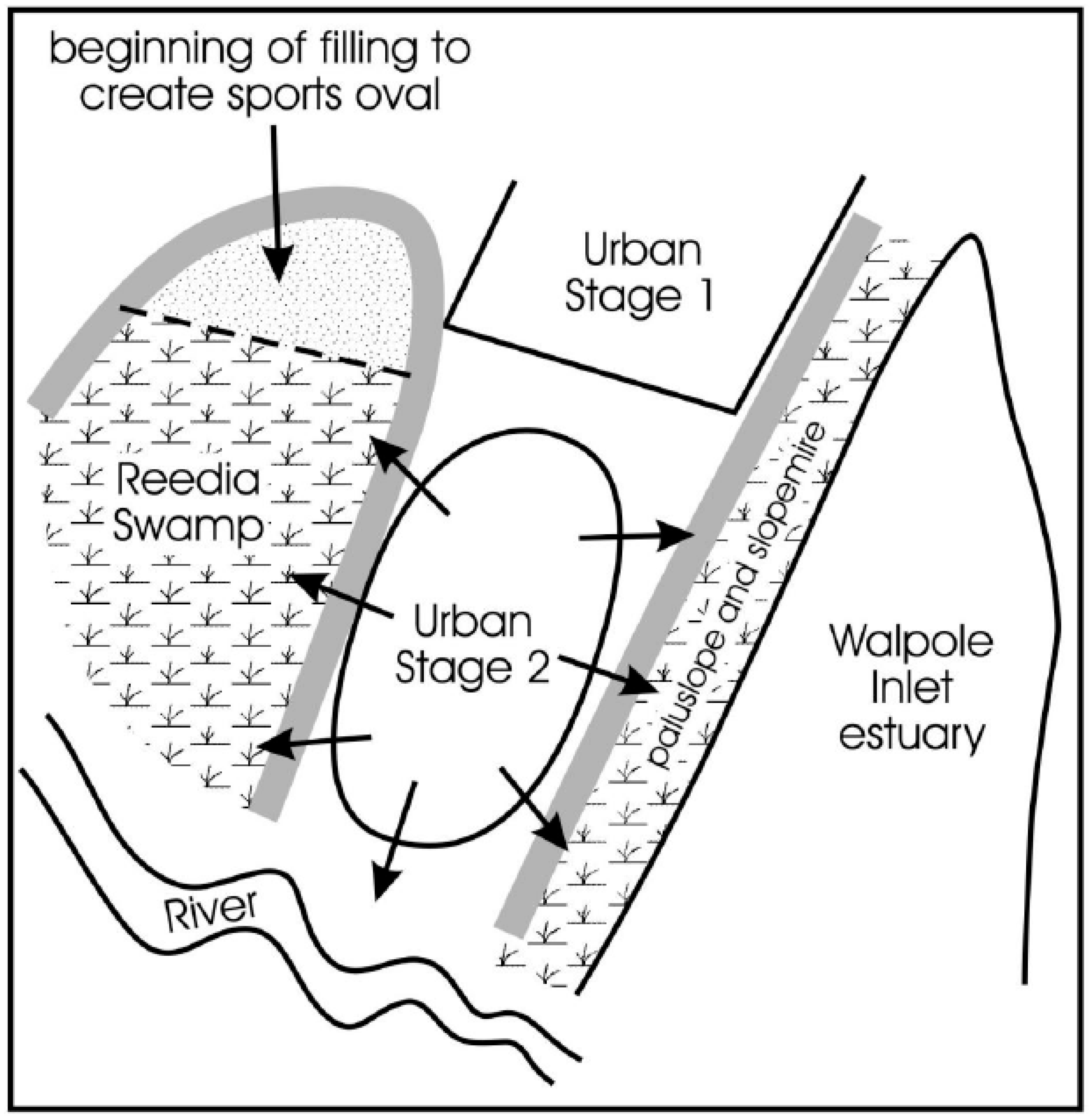

However, prior to geoheritage and biodiversity values being known, in the late 1980s, a pristine scenic area west of Walpole, adjacent to the Walpole River and Walpole Inlet, which at the time was inscribed as Class A National Park, was earmarked for urbanisation as a staged development, in spite of there being “very little demonstrated requirement for land in Walpole” [

19]. This was Stage 1 of an urban development; it was located on sandy dryland, and it received little interest. The demand for housing land in Walpole was tested in February 1987, when eight lots were offered for auction by the local government of the day; only one lot was sold, for AUD 11,500, and none afterwards, and the estimated cost of development (at AUD 15,000 per lot) exceeded the cost of the lot sold at auction). However, after being approached by a developer, the local government of the day also commenced action in 1987 to expand the existing residential area, i.e., a Stage 2 of the urban development, into nearby environmentally sensitive wetlands. The outcome of these initiatives was that a proposal was accepted, but many considered that the proposal did not meet the conditions required for development in this sensitive area, as set by the government in its call for expressions of interest to develop Stage 2.

In spite of there being no demonstrated demand for additional housing, the original proposal for increased urban development was as an outcome of political lobbying. As such, the proposal for an urban precinct referred to as Lot 650, and later known as Boronia Ridge, was born. The Boronia Ridge area was attractive to entrepreneurial developers in that it was proximal to the Walpole townsite and so could be serviced by the commercial centres of that town, and it was only 4 km away by road.

However, from the onset, it was clear that the proposed new urban area of Boronia Ridge appeared to be as a result of poor land-use planning. The main site of the proposed urbanisation was located on wetlands and would spill over to the Walpole River delta and wetlands. Urban infrastructures would impact on adjoining wetlands and the Walpole Inlet. In addition, the proposed urban development offered above-land surface wastewater treatment.

Meanwhile, if there was to be urban expansion, in regard to land use, there were serious constraints as to which direction to expand the township of Walpole; to the south was estuary and ocean, to the west and east were large rivers and national parks, to the north was agricultural land, wetlands and creeks, and a national park. (Interestingly, since the conflict, the Walpole and Nornalup Inlets are now designated as a marine park).

An opportunity arrived to contest the proposed urban development when the development proponent submitted a revised urban subdivision plan, because the earlier original Stage 2 urban development expired. However, with new information available in relation to the soils, wetlands, and environmental values of the area, in 1993, community groups and scientists combined, at a public local government meeting convened in Walpole, to demonstrate that any proposed further urban development at Boronia Ridge, with its above-land surface wastewater treatment, was inappropriate, both from an engineering perspective and due to the high conservation values of the area. With the support of local government of the day, who voted not to support approval of the Stage 2 development, and expert scientists who confirmed local environmental concerns, the community engaged in a 7-year conflict with the developer, the government agencies involved in decision making, and politicians of the day. Ultimately, the use of state-of-the-art science and traditional geomorphic, stratigraphic, hydrological geoheritage, and biodiversity principles failed to preserve the whole area as a wetland complex (see later) and failed to prevent the urbanisation of the area.

3.3. The Drive for Deep Sewerage in the Walpole—Boronia Ridge Area—Its Political Underpinning

Prior to the impetus to construct deep sewerage in the Walpole–Boronia Ridge area in the mid 1990s, the sewerage in the region was septic tanks. Each household disposed wastewater and sewage waste into individual concrete tanks buried shallowly in the ground, which discharged the waste into the underlying groundwater. However, septic tanks were failing as wastewater and sewage disposal systems. Much of the township of Walpole that had (preferred) estuary views was built on hill slopes that were wetlands (actually mostly paluslopes), because at the time of township construction, it was inconceivable that a hill slope could be a wetland. That hill slopes in Australia could be wetlands was only identified by Semeniuk and Semeniuk in 1995 [

13]. The consequences were that the septic tanks did not efficiently discharge into the groundwater in winter when water tables were either shallow or were at the ground surface, and as a result, odorous sewage discharged as springs on the ground slopes where housing was built on wetland slopes.

This prompted a desire by the residents to construct a deep sewerage network for the Walpole township, i.e., collect wastewater and sewerage waste from individual households and pipe it to a central sewerage processing installation. However, Walpole in terms of population numbers in the early to mid 1990s, i.e., with 400 residents, initially, was low on the priority of the state government for the construction of deep sewerage pipe-works and sewerage treatment works. In the early to mid 1990s in fact it was 20th on the list with other townships with populations numbering in the thousands obviously having higher priority. Yet, following the imposition of a centralised (piped) sewage treatment as a condition of development, through political lobbying, in an unprecedented action, in spite of the unjustifiable cost per capita, the responsible government agency moved the Walpole township from close to the bottom of the priority list to the top of the list for a sewage treatment plant. This effectively sealed the plans for the Boronia Ridge urban development, the environmental destruction of the Boronia Ridge palusmont, and the predicted disruption of the hydrological processes that maintained the adjacent slope wetlands that were to be conserved in reserves.

3.4. At the Foremost—Poor Land-Use Planning in the Proposed Boronia Ridge Area

The region was initially inhabited by Indigenous Australians over 20,000 years ago; however, as an outcome of colonisation by the British, in 1845, the first Englishmen settled on the Deep River and a permanent settlement followed in 1910. The district was opened for agriculture in 1930, and Walpole was gazetted as a town in 1934. The construction of its public buildings and housing, the infrastructure of roads, water supply, and electricity was largely completed in post-colonial Australia during a time when there was little public and town planning appreciation of land capability, and consequently, it can be understood how parts of the town grew and evolved amidst what would today be classified as “wetland”. In fact, elsewhere in Western Australia, at the same time, towns were settled without attention to the landscape, soils, and capability of the terrain to support urban systems in terms of housing support, potential rising damp, flooding, the suitability of refuse sites, the suitability of sewage disposal sites, and the impact of urban development on the surrounding natural environment. However, Boronia Ridge was planned and designed as a future extension to the Walpole townsite in the mid 1990s, when already, adverse environmental impacts elsewhere in Australia and in Western Australia had been documented, resulting from poor land-use planning or no land-use planning, and (supposedly) lessons had been learnt. However, in fact, the Boronia Ridge urban estate was approved for development even though it adjoined a national park, adjoined an estuary, and was to be sited on a wetland complex, without any further environmental report or land capability study. Furthermore, the consultants’ reports on the urban development were found to be flawed on a number of fronts (e.g., the stratigraphy underlying Stage 1 sites could not be transferred to Stage 2 sites). Even if the palusmont, such as that at Boronia Ridge, was widespread in the region (which it is not), in terms of the area being underlain by wetland, there was (at the least) a need for drainage, and the need to recognise that the proposed deep sewerage would alter the local hydrology and, particularly, the hydrology of adjoining wetlands of the national park and estuary shores (i.e., the “footprint” effect from the urban development would extend beyond the urban area). In regards to bordering the national park and estuary shores, there were significant species in the national park that would be impacted, but no studies of this factor nor of the buffer zone required to protect them were required under the revised development plans (after the relevant government authorities were advised that the environmental information on which the initial Stage 1 development was based could not be applied to adjacent areas in the proposed development, and after the environmental values of the site were known). The proposed Boronia Ridge urban estate simply represented poor land-use planning in the location of the urban estate and poor environmental management in how the urban estate would interface with the surrounding conservation estates.

3.5. Environmental Evidence Amassed by the Community Groups and the Scientists

From the onset, once the plans for the urban estate became public, the local community called a public meeting, and WANISAC was formed to obtain data to illustrate the inappropriate nature of the urban development (in terms of its location on a wetland and its potential effect on the adjoining slope wetlands and estuary) and the inappropriate nature of planned deep sewerage. The (then) President of WANISAC (M. Brocx) also approached the V & C Semeniuk Research Group (a Research and Development Group) to undertake stratigraphic, hydrogeological, and ecological studies on Boronia Ridge, the slope wetlands, the interface between Boronia Ridge and the estuarine shore, and the estuarine shore itself and to undertake studies of the ecological features of the area in a national context. The evidence amassed by the scientists and community groups was extensive (holistic) and thorough. They included the following:

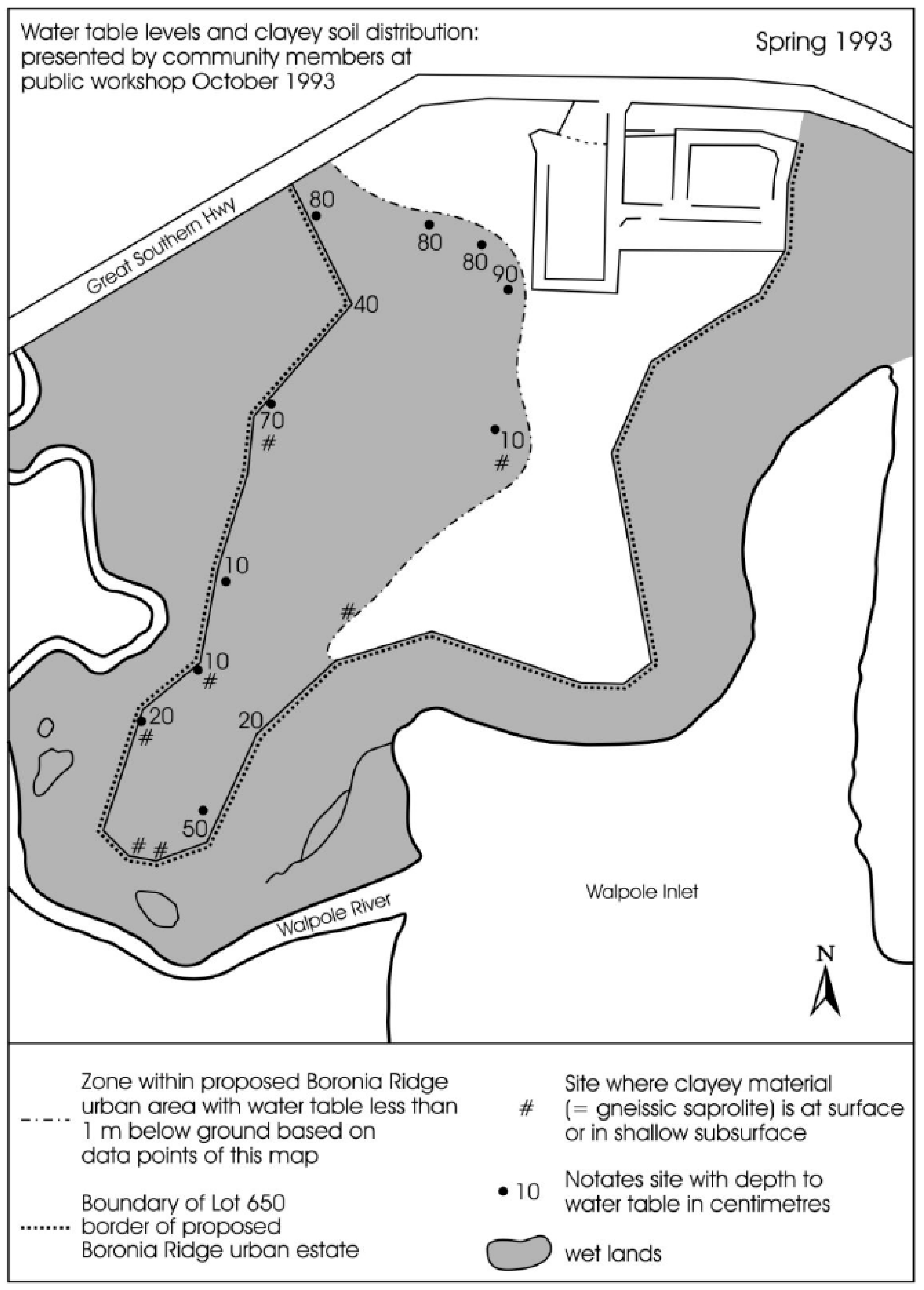

A map of the shallow groundwater and extent of the clayey substrates under Boronia Ridge (

Figure 4), concluding the terrain was a wetland;

Stratigraphic profile across Boronia Ridge to the adjoining slope wetlands;

Monitoring bores that showed the shallow water table came to the ground surface or proximal to the ground surface in winter, concluding the terrain was a wetland;

Monitoring bores across Boronia Ridge, ‘Reedia swamp’, the slopemire, and the paluslope that showed how the groundwater mound under Boronia Ridge maintained the adjoining slope wetlands;

Vegetation maps of the Boronia Ridge palusmont in a report by V & C Semeniuk Research Group;

Vegetation maps of ‘Reedia swamp’, the slopemire, and the paluslope in a report by V & C Semeniuk Research Group;

A Critical Assessment Lot 650 Stage 2 Boronia Ridge, Report by V & C Semeniuk Research Group 1997 to WANISAC, concluding that the terrain was significant;

Report on the National significance of Boronia Ridge and its adjoining ‘Reedia swamp’, the slopemire, and the paluslope written by V & C Semeniuk Research Group (1998) for WANISAC, concluding that the terrain was significant;

Report by Syrinx Environmental P/L and Pate on the distribution of indicator wetland plant species and their rhizomatous response on Boronia Ridge and its adjoining wetland slopes, commissioned as an independent study by V & C Semeniuk Research Group for WANISAC, concluding the terrain was a wetland and providing indicator species to delineate wetland boundaries and a map based on the indicators as to where on Boronia Ridge was the wetland boundary;

Report by Glassford [

18] on the saprolite and sand cover on Boronia Ridge; commissioned as an independent study by V & C Semeniuk Research Group for WANISAC, concluding the terrain was perching meteoric water to form a wetland;

Environmental Protection Authority 2001. Boronia Ridge Residential Subdivision Lot 650 Walpole, Shire of Manjimup-Sunland Pty Ltd. Report and Recommendations at the Senior Officers Technical Advisory Group to the Minister for the Environment;

South Coast Environment Group. Report to Michael Schramm, Manager Local Planning, Ministry for Planning, Bunbury, WA.

These documents and reports 1–12 have been lodged as archives in the JS Battye Library, in Perth, Western Australia, by the Wetlands Research Association as the The Boronia Ridge Archives [

19].

It should be noted at this point that the Minister for Lands of the day, based on advice received from his government agency, and the development proponent, did not believe that the Reedia Swamp was a wetland, and rejected submissions from the Walpole community that there was an error in landform described in the development submission. However, upon invitation from WANISAC, the Local Minister for Agriculture visited the area and was unable to step out of his vehicle onto the wetland without changing into rubber boots; for the first time, a Government representative directly witnessed the wet, boggy, peat-floored environment and could report back to the Minister for the Environment that indeed the terrain was wetland.

All this information resulted in convincing the (then) Western Australian Minister for Environment (and their successors) to review the situation that the environmental conflict was based on. Consequently, the Minister commissioned an ad hoc technical advisory group called ‘Senior Officers Technical Advisory Group’ (SOTAG) which was supposed to be comprised of highly qualified scientists (temporarily drawn from the various environmental departments of the State Government) who would have the skills to review the data and conclusions of WANISAC and its scientific advisors and provide recommendations. However, as will be shown below, in practice, this was not the case.

After reviewing the data and conclusion deriving from the Boronia Ridge area, SOTAG, WANISAC, and other stakeholders (the developer, the developer’s consultants, WANISAC’s scientific advisors, and other relevant community groups) were to attend a workshop on-site in the Walpole area to debate the environmental issues and resolve the significant wetland versus urban development issues.

It might be emphasised at this point that the chief environmental safeguard and watch body, the Environmental Protection Authority (the EPA), had earlier refused to assess the revised development proposal on the basis that the environmental studies conducted on the (existing) Stage 1 urban development as well as the (revised) Stage 2 urban proposal was within the same “footprint”. This stance was despite being provided with local and expert advice that the landforms in the proposed development envelope were not consistent with the developer’s report as being comprised of 5–6 m of well drained sandy soils, when in fact the landform was comprised of wetlands with clayey saprolitic soils and water table levels in the vicinity of 10–90 cm depth. This is evidence of both the problem of the information contained in the environmental report provided by the developer, and the developer’s consultants, in applying the landform of Stage 1 sites to Stage 2 sites, and the incapacity of the decision-making officer of the day to understand not only the adverse environmental impact that the revised development proposed would have on environmental values but on the future construction of houses if the development was to proceed based on the development proposal.

4. The Dynamics of SOTAG

Initially, the concept of a Senior Officers Review Group (SOTAG) was welcomed by WANISAC, its scientific advisors, and the environmental community groups in the region, because they assumed that highly qualified scientists would immediately see the problems of urbanisation and sewerage on Boronia Ridge. However, it soon became apparent after the selection of the SOTAG and its chairperson that there were problems. Contrary to a ministerial directive by the Minister for the Environment for a Senior Environmental Officer to head SOTAG, a junior level officer, with a degree in planning, was appointed, by the Department of Environmental Protection, as the chairperson. Only three of ten SOTAG members had higher degrees (and two of these did not attend SOTAG meetings). Most of the SOTAG team could not be called “senior officers” or trained in wetland sciences, as they included foresters, planners, and agricultural scientists. In contrast, there were four doctorates and one university professor who comprised the scientists who provided information in reports to WANISAC, each recognised internationally and highly qualified in their field as wetland scientists and landform/soil scientists. In the final analysis, the data, opinions, and conclusions of these professional scientists were either not used or dismissed by persons under-qualified or unqualified in the fields of wetland science that they were adjudicating.

As mentioned above, the chairperson of the Senior Officers Technical Group (SOTAG), established by the Minister for the Environment of the day, and appointed by Department of Environmental Protection on behalf of the Minister, was a low-level, young, and inexperienced employee in the Department of Environmental Protection, who had recently been seconded from the Department of Planning, with no environmental qualifications whatsoever. With a basic degree in planning, the chairperson was ill-suited to manage a senior environmental specialist group or understand the environmental issues forwarded by specialists in their field of expertise. Trained in urban planning, the chairperson clearly did not understand the geoheritage or biological values of the palusmont at the site visit and had an ethos for facilitating development as opposed to protecting natural heritage. In this situation, SOTAG failed because the (junior) chairperson took advice from government agency personnel without the educational background or experience to assess expert advice on the national importance of Boronia Ridge for its inherent geoheritage and biological values and its role in the complex hydrology of the area in maintaining the adjoining slope wetlands.

For instance, instead of accepting hydrological data and information from groundwater monitoring, the SOTAG officer relied on a government agency officer trained in modelling. One particular officer insisted on applying a theoretical model to the hydrodynamics of the Boronia Ridge area when there were no data in the model, at the same time rejecting the hydrological monitoring data collected in the region (obtained empirically from monthly monitoring over three years) that showed contrary patterns to the model. Another officer in the Department of Environment, trained only in agriculture (and not wetland science, wetland ecology, stratigraphy, and hydrology), provided misinformation and incorrect assessments on wetland boundaries and made scientifically incorrect conclusions, because they did not understand the environmental wetland issues and “did not know that they did not know”.

During a community SOTAG and WANISAC workshop, the essence of the problem of how Boronia Ridge was a wetland (a palusmont) and how the groundwater mound under Boronia Ridge delivered water to and maintained the adjoining slope wetlands was presented to the stakeholders and attending SOTAG members in an idealised diagram, as shown in

Figure 5.

4.1. Outcome of the SOTAG Workshop

The outcome of the SOTAG workshop was that urban development was conditionally approved (see below). There was a failure to adopt the expert advice of independent internationally renowned wetland and earth scientists to preserve the area’s unique palusmont, despite the science presented. There were some development conditions imposed by SOTAG that ought to have halted the development, but these were ignored by the Ministry for Planning.

Following the SOTAG meeting, the chair of SOTAG reviewed the findings and provided recommendations to the minister that the urbanisation of Boronia Ridge should be approved, subject to the development meeting a number of environmental conditions, over and above a centralised sewage treatment plant. These conditions included identifying adequate buffers to the foreshore/paluslope wetlands, the Reedia wetlands, and the palusmont wetland. In practice, SOTAG ignored the wetland boundaries submitted by the state’s foremost wetland scientists and advice to exclude the palusmont wetland from the proposed development and required a wetland buffer to be put around a spine road that axiomatically destroyed the palusmont wetland. Furthermore, the wetland buffer was determined by government agency staff in consultation with the developer.

4.2. Problems Subsequent to the SOTAG Workshop

As a final act of attempting to block the proposed urban estate, the local government of the day, i.e., the Shire of Manjimup, accepted the data, information, and conclusions of WANISAC, and its scientific advisors and passed a resolution not to approve the urban estate. However, using its higher legal powers, the state government’s Ministry for Planning over-rode this resolution, dismissed the scientific information provided, and approved the development based on the premise that all environmental issues raised in submissions could be managed. However, it was recommended that the adjoining

Reedia wetlands and other areas (which were to form the vegetation buffer) be reserved for flora and fauna; that is, subject to the planning conditions being met, Boronia Ridge urban estate could be built on the palusmont. The approval essentially was based on modelling and hypothetical management but with “no science” and “no data”, in contrast to and despite the scientific advice and information, based on data provided by WANISAC, its scientific advisors, and other community groups. The extent of the data obtained by WANISAC and its scientific advisors is reflected in the fact that a 600-page monograph deriving from these data later was published by the Western Australian Museum [

15]; this monograph was based on five years of monthly monitoring of hydrology and hydrochemistry (of which Boronia Ridge was a local study site) and twelve years of stratigraphic, pedologic, and ecologic studies.

At the end of the day, many environmental conditions were not met, not scientifically based, or modified, and the problems of environmental degradation and destruction predicted by WANISAC and its scientific advisors materialised.

For instance, the pipes for deep sewerage to Boronia were laid with the following three consequences: 1. the engineers discovered the reality of the slopemire and paluslope wetlands when they encountered waterlogged soils along the boundary between the wetland slopes and Boronia Ridge and so had to dewater the trench, thus perturbating the natural hydrological situation between the uplands of Boronia Ridge and the adjoining wetland slopes (an outcome that was unexpected for them); 2. the natural pathways of water flow from the uplands of Boronia Ridge and the adjoining wetland slopes were forever impacted and changed when an impervious large-diameter concrete pipe was buried along the ecotone length; and 3. leaks and disruption in the sewerage system resulted in sewerage occasionally over-spilling and discharging into the ‘Reedia swamp’, changing the natural nutrient levels of this nationally significant wetland and its vegetation.

Following the fact that various scientific studies highlighted that the Boronia Ridge upland was adjoined by slope wetlands, it became apparent to the Department of Environment that there was now a need to ascertain where exactly the boundary of the urban estate should be placed. This boundary was determined by two officers from the Department of Environment, one trained in forest management, the other in agriculture. However, rather than use the information of Syrinx Environmental P/L and Pate [

17], wherein the histological, anatomical, and ecological information showed key indicator species that could be used to delineate a boundary, the two officers reverted to the gross information and approach of the 1930s, essentially that paperbarks (

Melaleuca rhaphiophylla) represent wetland conditions (often the wettest part of a wetland), and jarrah trees (

Eucalyptus marginata) represent dryland conditions, with both species readily identifiable, and so, the upland/wetland boundary can be placed exactly halfway between the stands of paperbarks and those of jarrah. The nuances of using

Evandra aristata,

Kingia australis, or selected species of Restionaceae, as proffered by Syrinx Environmental P/L and Pate [

17], were not understood and/or were ignored, and so, the boundary was put in the wrong place by tens of metres and in some places by ~100 m. If the wetland boundary had been put in the correct place, the urban estate would have been forced by environmental law and planning law to be on dryland, and there would not have been enough dryland to build on.

5. Discussion—What Ethics Were Involved and Breached?

The urbanisation of Boronia Ridge on a nationally unique and significant palusmont and the effect of the urban estate on the adjoining wetland slope environments in terms of sewerage pipe emplacement and the alteration of the hydrology represents a failure of the environmental process in Western Australia. By all accounts, with the wealth of data and information, the urban development should not have proceeded.

The primary reason for the failure is that the decision makers in the state government’s environmental departments were not sufficiently prepared to address the issues at hand and were out of their depth. Despite engaging with highly credible and established wetland scientists and hydrologists, they did not heed their guidance. In addition, the advice of junior and inexperienced government workers was preferred to that of more highly trained (non-governmental) researchers and consultants. The state government’s environmental departments interfaced with highly credible and accomplished wetland scientists and hydrologists but were comfortable in their ignorance. In fact, they did not perceive their ignorance.

The problems of ethics related to the extent of the lack of open and transparent planning processes mired in and were influenced by discussions and decisions between the developer, their agents, and government agency officers.

The problems of ethics also related to the installing of a junior employee in a position of high responsibility in dealing with matters of national importance. SOTAG was initially promoted to WANISAC, its scientific advisors, and the other community groups to be a top-level, highly qualified adjudicating committee. In reality, its role was to justify a pre-ordained development and dispute scientific data and information provided without the evidence or educational background to do so.

The planning officer who made the ultimate decision in regard to conditions having to be met, for titles to be issued, can be assessed as essentially having not met the details and spirit of their office but also breached the power vested in the office to facilitate sustainable development based on community expectations for informed science-based decision making.