Abstract

This work explores issues related to traditional heritage, its evolution, and its transmission within construction practices. It focuses on a case study concerning the reintroduction in Tamentit, an oasis in southwestern Algeria, of a nearly forgotten construction technique: the use of a local stone known as “Agharf”, composed of saline pebbles, bound or assembled with a clay mortar enriched with salt, allowing the construction of robust structures adapted to their environment. Traditionally used in certain specific areas of the Sahara, it was notably employed in isolated regions such as Siwa in Egypt. After a long period of disuse, this technique is experiencing a renewed interest and appears to be gradually reintegrating into the local practices of artisans. This raises several questions: What justifies the return of this technique? What role does contemporary society assign to it, and what actions are being taken to ensure its sustainability? Fieldwork, consisting of on-site observations and semi-structured interviews with artisans and master artisans, the ma‘alem, was conducted to analyze their perception of this heritage, to understand the tangible and intangible aspects of the construction process, and to explore the challenges related to its transmission. The interviews reveal that, despite the challenges and reservations expressed by the community, the Agharf remains for the artisans a symbol of identity and craftsmanship, far from being a lost intangible heritage. The conditions and benefits of its use are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) encompasses practices and knowledge passed down through generations, constantly evolving and essential to collective identity. It is based on community recognition, respect for human rights, and a sustainable approach [1]. In this perspective, UNESCO highlights dynamic practices that contribute to strengthening collective identity, which it defines as an integral part of ICH. It is with this in mind that UNESCO emphasizes the “vitality of transmission” of cultural practices and skills that sustain traditional craftsmanship. UNESCO establishes several criteria for an element to be considered as ICH, including its intergenerational transmission, continuous adaptation, and role in cultural dialogue. It also recommends safeguarding actions such as documenting practices, education, and community involvement in their preservation [2]. Due to this necessity, UNESCO underscores that ICH should only be recognized as such with the approval of the communities, groups, or individuals who have shaped it, without any external imposition [2]. Although driven by practical needs, this dynamic is rooted in cultural and societal contexts that shape the construction process, among them the training and beliefs of builders [3]. These aspects combine functional imperatives with expressive needs, integrating cultural values, value judgments, diversity, and personal creativity [4]. The knowledge and skills of master craftsmen remain essential to legitimizing and transmitting cultural practices, forming the foundation of an authentic building culture [5]. However, while the transmission of knowledge has been widely studied, the transmission of know-how, skills acquired through practice and experience, which require field studies, has been less explored [6].

Many elements of ICH (Intangible Cultural Heritage) related to construction are threatened by the disappearance of preservation conditions and the lack of interest among younger generations in their transmission. In this context, the Algerian State, particularly in regions such as Tamentit, attempted to play a role by initiating the creation of a protected area to preserve the historic center, with the ambition of establishing a Preservation and Enhancement Plan for Protected Areas (PPMVSS). However, this project never came to fruition, thus hindering any structured and regulated conservation initiatives. However, when knowledge endures without completely disappearing, it becomes relevant to examine the practices that quietly persist [7]. Tamentit remains one of the rare examples where direct transmission endures, with apprentices receiving knowledge from master craftsmen while respecting local traditions. The training is based on the transformation of clay materials and the construction of earth-and-straw roofs. Conservation techniques, such as the use of salt to preserve wood, are also taught there. Agharf is the Berber Zeneta name for the salt stone technique used in Tamentit. Its implementation relies on precise expertise; builders assemble it with a clay mortar enriched with salt, which strengthens the cohesion of the walls and ensures their durability over time. This practice is certainly not unique to the region, as several sites—at least nine, most of which have disappeared—have been documented [8]. Nevertheless, these constructions persist in Tamentit as a living testimony to a technique deeply rooted in the collective memory, making it a vehicle for cultural values. Salt, as a key resource in Tamentit, has notably influenced the local architecture through its practical use and symbolic significance. Salt stone has been used in Tamentit since the earliest human settlements, dating back at least to AD 725 The technique has thus been passed down through generations as a fundamental artisanal knowledge of the local community. Research has also highlighted the use of this technique in Siwa, particularly in the Shali fortress [9]. Salt has thus proven to be a valuable construction material in desert regions. Extracted from the ground, it is highly prized for its durability and also stands out as an excellent heat accumulator [10]. Recent studies have explored the thermal insulation capacity of this material [11]. Due to these unique properties, salt is increasingly being considered a promising alternative in the face of the depletion of natural construction resources [12]. In Siwa, a prototype guesthouse was built by local labor using local materials, including salt stone and Karshif [13]. Recently, similar projects involving hotels built using salt blocks have emerged in Bolivia, taking advantage of the appeal of this material [14]. More recently, projects have begun using brine from desalination plants as an alternative to cement [15]. Despite its potential, the use of salt in construction remains an emerging topic and is still largely overlooked [16].

Agharf is now experiencing a renewed interest, albeit still in its early stages, as evidenced by artisans independently initiating participatory projects aimed at rehabilitating traditional ksour (traditional fortified North African villages) houses into guesthouses, which contributes to a rapidly growing tourism economy. As mentioned earlier, the use of Agharf proves to be particularly relevant in conservation efforts for palm wood roofs-terraces, which are currently in a state of significant fragility. The use of Agharf was traditionally favored for buildings of great importance, such as the homes of leaders or mosques, due to its durability. In the case of residential houses, it was especially well-suited to environments where relative humidity, common around constructions near gardens, required appropriate solutions.

The technique remains marginal compared to other traditional construction methods, such as adobe, and its transmission, although preserved by elder masters, remains limited. The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) has launched an ecotourism project in Tamentit to revitalize the local economy by promoting natural and artisanal resources. With the help of the IUCN, the Foggara Association of Aghmoul (in reference to an old underground drainage gallery) built a traditional house using Agharf [17].

We hypothesize that salt stone represents a viable alternative to imported materials, helping to enhance the durability of palm wood roof structures, which are often threatened by termites. This revival of the salt stone construction technique is understood as a choice rooted in shared cultural values that today influence construction methods. Moreover, redefining the uses of ancient structures allows for the transmission of ancestral know-how while addressing economic challenges. The validation of the hypotheses will be based on the analysis of testimonies collected through semi-structured interviews conducted with ma‘alems (master artisans) and local artisans who are still active today. The main objective of this research is to explore possible pathways to consolidate this historical tradition in Tamentit. Its current revival, although modest, reflects a recognition of this cultural heritage and a desire to preserve this ancestral know-how as part of intangible heritage. This article thus outlines the social and relational context surrounding the use of this technique, revealing the complexities associated with its transmission. It highlights, in particular, the potential health impacts on artisans, the difficulty of implementation, and other social and economic challenges. Finally, the article examines the prospects for transmitting this expertise to the generations of artisans still active today.

2. Materials and Methods

This research involved the exhaustive collection of all works related to the use of salt in construction. The documents consulted include scientific articles, specialized journals, and academic books, covering case studies, historical analyses, and future perspectives.

The selection of sources took into account the most relevant works, such as those of Laureano [18] (1991), Battesti [9] (2006), and Echallier (1972) [8], which provide both a historical and technical perspective.

2.1. Comparative Approach

Salt architecture, although rarely studied, has been the subject of some specific analyses, particularly through works that examine its use as a building material from different perspectives. Among them, two studies stand out due to their complementary approaches:

On the one hand, Ismail Hamed Ismail Ali, in his article “Some features of salt-architecture in the medieval Sudanic cities: Taghaza in Mali as a model” [19], highlights the central role of salt in the life of West African societies during the Islamic period. His study focuses on the city of Taghaza, located in northern Mali, known for its significant salt mines. The author cites it as the most emblematic example of the “salt cities” mentioned in historical accounts. He emphasizes the specific features of this architecture, considering it as a distinct architectural style unique to West Africa. To support his argument, he relies on historical sources as well as recent archaeological research, demonstrating that salt, due to its abundance and economic significance, contributed to the persistence of an architectural style closely linked to the collective memory of salt-based settlements.

On the other hand, Vincent Battesti, in “De l’habitation aux pieds d’argile. Les vicissitudes des matériaux et techniques de construction à Siwa (Égypte)” [9], conducted extensive field research in Siwa, working directly with the local community to collect firsthand accounts and observations on the use of traditional building techniques, particularly Karshif construction. He highlights the shift from traditional salt-clay mortar to cut limestone gypsum, which has led to rapid changes in construction methods and overall habitat design in the region. His work is also based on precise descriptions of Karshif, drawing from previous studies to reveal its implementation principles, its durability over time, its vulnerability to water, and the ancestral craftsmanship associated with it.

Our research builds on these works and other studies on built heritage in arid environments, which are primarily focused on the examination of the most constrained historical sites, revealing valuable adaptation approaches [20]. Similar to Battesti’s work, it offers a reflection on how this practice endures, adapts, and finds new ways of being valued. Beyond the insights provided by previous studies, our research is also grounded in a field-based approach. Direct observation allows us to grasp the dynamics of knowledge transmission during construction work, identifying the challenges encountered in this process. This approach is complemented by an ethnological dimension, considering the perceptions, narratives, and representations that artisans and the local community associate with these skills.

2.2. Research Methodology

Method of Selecting Respondents

The approach adopted in this study is based on qualitative field research, relying on interviews and direct observation of practices and restoration work carried out within the ksar of Ouled Ali Ben Moussa (Tamentit).

Given the absence of permanent residents within the ksar, the interviewees were selected from people present on site who possess in-depth knowledge of the area.

The investigation thus focused on those most directly involved in construction processes and knowledge transmission, in order to better understand the reality of these practices.

The main groups of respondents and the reasons for their selection are as follows:

- Ma‘alems or Master Artisans: Respected members of the community, recognized for their mastery of traditional techniques and know-how, meeting the expectations of clients. Their expertise was also confirmed through the observation of their work. Priority was given to those who still practice ancient techniques, often threatened with disappearance. However, some ma‘alems were rather brief in their responses, either due to lack of time or limited interest in participatory discussions;

- Active Local Artisans: More directly involved in rehabilitation work, these artisans provide a practical perspective on the current challenges they face, while still mastering part of the traditional techniques;

- Members of Heritage Associations: Positioned at the heart of heritage management projects, they have valuable insight into administrative issues and the limits of collective action. Some artisans are also members of these associations.

A total of 11 people were interviewed between November and December 2024.

The profile of the respondents is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Profile of the respondents.

2.3. Nature and Conditions of the Interviews

- ⮚

- The discussions were conducted in a semi-directive manner, allowing participants to freely express their ideas and develop their responses;

- ⮚

- The process was made possible through the intermediation of El Idrissi S, president of the heritage association of the ksar. His role was crucial in establishing a climate of trust and facilitating initial contact;

- ⮚

- Depending on the participants’ preferences, the interviews were conducted either orally—recorded and then manually transcribed—or in writing, using a questionnaire. However, oral exchanges generally proved richer and provided access to more spontaneously expressed discourses and perceptions;

- ⮚

- The interviews were conducted in Darija, Algerian spoken Arabic, which is the daily language used within the community. In the presence of former teachers whose accent or dialect sometimes complicated understanding, El Idrissi S. intervened to rephrase or clarify their remarks;

- ⮚

- The duration of the recorded interviews varied overall from 15 to 30 min, depending on the availability of the participants and the context of the exchange, as well as on the interest in the subject.

2.4. Investigation Locations

The interviews were held mainly inside the ksar or in its immediate surroundings, often at the very places where the artisans worked.

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the respondents, including their age, professional status, years of experience, and the modes of knowledge transmission.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the sample surveyed.

It is worth noting here that in the local context, the status of “ma‘alem” is not always associated with seniority or professional experience. Some craftsmen, despite having many years of practice, do not identify themselves as such. This is often linked to social recognition within the community, but also to the fact that in Algeria, vocational training diplomas mainly focus on modern techniques, thereby excluding traditional know-how.

2.5. Themes Explored

The interview included several themes aimed at better understanding the journey, practices, and representations of the artisans. However, the analysis presented here deliberately focuses on elements relating to the use of Agharf, its transmission, and the difficulties associated with it.

- Practices of transmitting artisanal know-how and the difficulties encountered;

- Knowledge related to the use of Agharf and its place in construction techniques;

- The methods of harvesting, supplying, and implementing Agharf;

- Craftsmen’s perceptions regarding the advantages, limitations, and risks associated with this technique;

- The main current difficulties encountered in exercising the profession (access to resources, technical mastery.

Other themes were addressed (relationship with institutions, future of the ksar, etc.), but they did not constitute sufficient material or were not directly relevant to the objectives of this article.

The following questions represent a sample of those asked: How are traditional construction techniques transmitted within your community? What are the main challenges encountered in this process? What do you know about the ancestral technique of Agharf (salt stone or salty earth)? What importance do you attribute to the Agharf technique in the current context of traditional construction? What advantages and disadvantages does this technique have compared to other methods? How does the community address challenges related to the scarcity of resources necessary for implementing traditional techniques?

The objective of these interviews was to explore the participants’ motivations, analyze the social, economic, and cultural issues related to the use of salt stone, and understand the methods of transmitting artisanal know-how. Additionally, it aimed to identify cultural and social barriers to the adoption of traditional techniques and examine practical challenges, such as the availability of salt stone and logistical constraints in construction projects.

2.6. Constraints and Limitations of the Study

The study was not without its challenges, particularly due to travel constraints. Despite prior knowledge of the field acquired during previous visits, Author 1 was unable to visit the site for this survey as often as he wished, thus limiting her direct participation in discussions with the artisans. As mentioned previously, the support of the president of the El Idrissi association was essential. For cultural reasons, author 1, as a woman, would not have been able to engage with the artisans alone. The authors wish to emphasize the importance of respecting local cultural codes and not imposing a presence that could be perceived as intrusive or inappropriate in this context. The mediation of the speaker thus helped establish a bond of trust essential for the smooth running of the interviews. In addition, efforts were made to facilitate communication, particularly with the older participants. Some, not proficient in writing, expressed themselves orally during recorded interviews with their consent. Difficulties related to understanding the local dialect could also arise.

Furthermore, some exchanges were particularly rich and in-depth, while others were limited to briefer exchanges, showing a more distant engagement on the part of some participants. The variations in the interviews demonstrate the limitations of this type of study.

2.7. Context of the Study

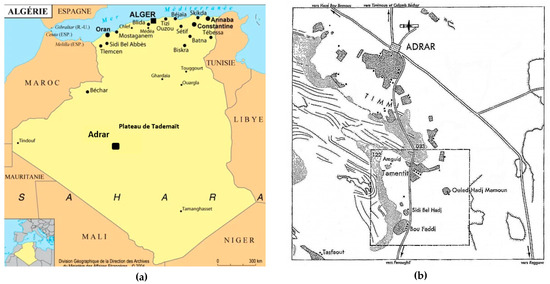

Tamentit is a municipality in the Adrar province, located about 1400 km southwest of Algiers. It lies in the heart of the vast historical region of Touat, which includes Touat proper, Gourara, and Tidikelt, an area that covers a large portion of the southwestern Saharan region of Algeria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area: (a) Location of the Adrar region in Algeria [21]; (b) Location of Tamentit [22].

2.8. Historical Context of Tamentit

Tamentit, meaning ‘perfection of the eye’, or Tem-n-tit, which translates to ‘eyebrow of the eye’ in Berber [23], is recognized as one of the oldest oases in the greater Touat region. The area is connected to both the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan worlds through important caravan routes, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and know-how between distant cultures.

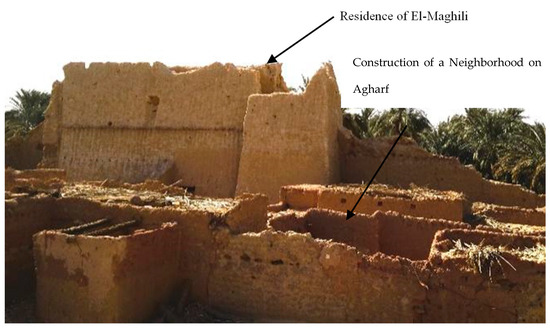

The city has thus been enriched by a remarkable cultural and historical diversity, marked by the arrival of multiple civilizations. Martin [23] first mentions the Getules, an indigenous Berber community that thrived until 100 AD. They are credited with creating the first stone-built structures. Next, Jews occupied the region from 100 to 600 AD. During this period, Tamentit transformed into a predominantly Jewish city, earning the nickname “Tamentit the Jewish” with its own ethnic identity. The Jews built cities in Tamentit called “ksour” (plural) and “ksar” (singular), with circular walls and houses that served as fortifications. Accounts specifically mention the presence of synagogues around the 6th century at the ksar of Ouled Hemmal, and later in the 8th century at the ksar of Ouled Mimoun, both built with salt stone. From the 7th to the 11th century, the region saw the continuous arrival of nomadic groups, mainly Zeneta. From this point on, the ksour expanded into larger neighborhoods, where houses and living spaces were organized within their protective walls. The 11th century marks the beginning of the Arab era, a turning point in the region’s history with the gradual Islamization of the local populations. In the 12th century, the ksar of Ouled Ali Ben Moussa [8] emerged, with its leaders playing prominent roles in Tamentit. This ksar is a testament to careful planning, with guesthouses as its main feature and a combined and diversified use of local materials, including salt stone. Many other techniques persist, the most widespread being Toub, a mud brick made of clay and sand. Prismatic bricks were also used, although much more rarely. Other masonry techniques combine stone with clay. In the 15th century, the preacher Sheikh Abdelkrim el-Maghili settled in Tamentit, where he ended the Jewish presence [24]. His house, built from salt stone and used as an arms depot, serves as a historical testament to this period. Today, although some ksour are in poor condition and many houses are abandoned, the ksar remains alive thanks to enduring traditions. Community gatherings, ceremonies, and meetings continue to be organized there, ensuring the transmission of customs and thus maintaining cultural vitality at the very heart of the ksar.

2.9. Climatic and Geomorphological Context

Tamentit is characterized by a desert climate, with very hot summers when temperatures often exceed 40 °C, and cool nights, sometimes dropping below 10 °C. In winter, the days are moderate (20–25 °C), but the nights can be freezing, approaching 0 °C. This thermal contrast, combined with annual rainfall of around 10 mm/year, creates a demanding environment.

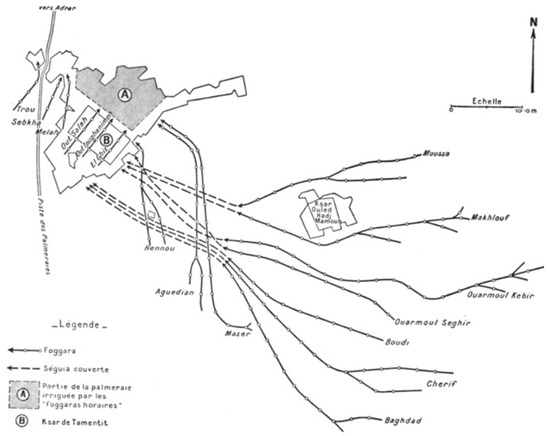

The landscape is not limited to the expanses of palm groves shading the oasis gardens, nor to the vast lakes in the depressions without outlets, fed by rainwater and the drainage of gardens/palm groves, where salts accumulate [9]. The desert landscapes around Tamentit consist of rocky formations, dunes, and plateaus. Ingenious use of local geological resources is evident in the underground water collection system, which consists of draining pipes known as foggara, which distribute water through a network of séguia, both underground and aboveground pipes. The ksar taps into water sources from two origins: at the foot of the ksar, from the Continental Intercalary sandstone, which rises 15 m above the sebkha, while to the east, water comes from the Tademaït glacis [25] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Water management through the foggaras of Tamentit [25].

The sebkha (Figure 3) here acts as a natural barrier, limiting both the spread of vegetation and the expansion of the ksar. This saline formation, called halite, appears as surface deposits or is extracted from shallow mines [26]. Martin describes it as the ‘upper basin of the great Touat depression’, receiving water from the western basin. Separated from the High Plateaus by the Erg Occidental massif, it borders the oases on its eastern shore, which utilize its water resources for the development of palm groves [23].

Figure 3.

The Natural Setting of the Tamentit Sebkha (Photos by El Idrissi. A).

The two water sources have allowed for the expansion of irrigated lands. The palm grove thus extends between the ksar and the sebkha, where it borders salty, infertile land, while on the other side, it stretches toward the path connecting neighboring localities [25]. These conditions and their history have given rise to exceptional biodiversity, which remains essential to the survival of many species today, earning it a place on the list of Wetlands of International Importance in 2001 [27].

3. Results

The Dynamics of Knowledge Transmission and Continuity of Traditions. The transmission of practices relies on ancestral know-how taught by the ma’alem, master artisans. Learning, which begins at a young age, combines practical techniques with traditional values. Apprentices refine their skills in soil fermentation (Tekhmar) and construction using earth and wood, essential elements of local architecture.

In the past, the reconstruction of ksour was a collective effort, with families preserving their heritage through intergenerational transmission of skills. In Tamentit, the Ziyara, associated with religious celebrations, allowed inhabitants to maintain their ksar in a spirit of cooperation. Today, participatory construction projects are restoring traditional houses into guesthouses, perpetuating local hospitality. Inspired by the Ziyara, this initiative emerged in response to the need to promote local heritage and harness its tourism potential, marking what could be the beginning of a heritage-making process [28].

Not all residents share the same vision. Some have converted their homes into enclosures for their animals, while others reject the idea of rehabilitation, considering it unnecessary or inappropriate. In response, artisans lament the lack of recognition for their work, which threatens the preservation of the ksar. Despite these resistances, they strive to restore what can still be saved, particularly the deteriorated roofs. Various solutions are being explored, including the use of salt as a valuable alternative to the increasingly scarce wood supply. Agharf, though little-known and perceived as outdated, still piques the interest of some artisans, though few of them still master its techniques.

The Agharf in Traditional Ksar Construction.

Agharf, a traditional Berber Zeneta term meaning “salt”, refers to a stone particularly valued for its strength. According to Laureano, in his study of the ksar of Tamentit, blocks of salt stone were used in the form of triangular-sectioned prismatic voussoirs for the construction of the fortified walls of Tamentit. The voussoirs are arranged in a way that interlocks with each other, forming a structure capable of supporting heavy loads. He also notes the presence of flat stones arranged in a herringbone pattern, creating a chevron motif that reinforces the stability of the whole structure [18]. Its use gradually spread across the ksour and in several old neighborhoods. Among them, Ouled Mimoun, founded by a Jewish community in the 8th century, is a significant example. The technique was then perpetuated in the construction of ksour such as Toufaghi, Ouled Ali Ben Moussa, Ouled Hemmali, Ouled Yakoub, Ouled Mohamed, Akris Sidi Cheikh, and among the houses, to name one, the residence of the preacher Cheikh El-Maghili (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

House of the preach er El-Maghili built in Agharf (Photo by the author).

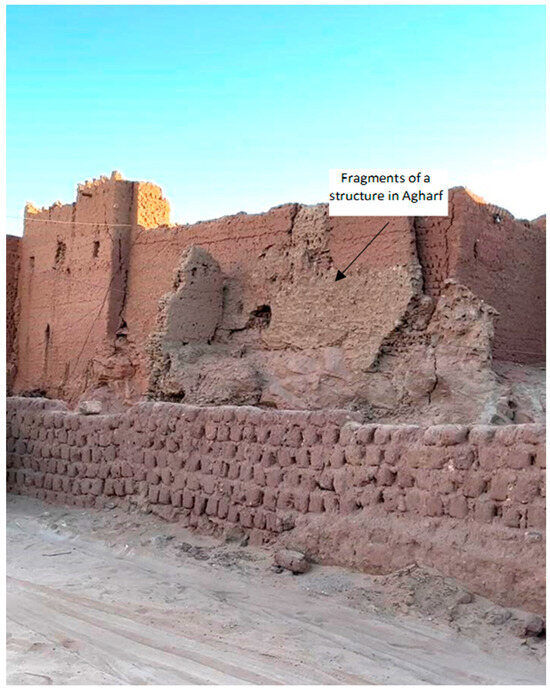

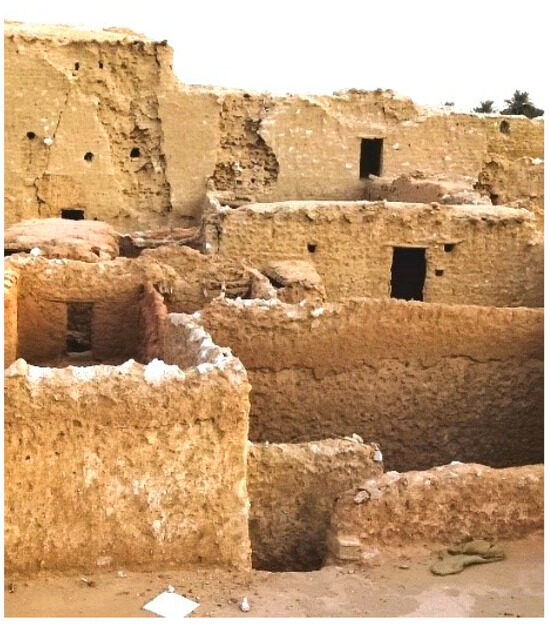

The Agharf technique gradually spread before declining with the arrival, in the 15th century, of raw earth (adobe) from southern Morocco [8] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Gradual replacement of Agharf with adobe (galba) (Photo by the author).

Over time, different construction techniques have evolved, gradually integrating new methods while maintaining the limited use of saltstone, which, although less common, has remained present enough to be known and highlighted by artisans.

3.1. The Agharf: A Material with Comfort and Protection Properties

The ma‘alem emphasize in their testimonies that their life experience in these houses led them to appreciate the distinctive properties of this material. According to their findings, salt provides superior comfort when integrated into the walls, purifying the indoor air, regulating bodily humidity, and ensuring a dry and healthy environment. Its remarkable thermal inertia allows it to absorb and release heat slowly, thus maintaining a stable and pleasant temperature inside despite variable outdoor conditions. In addition to its insulating properties, salt still plays a significant role in cultural and spiritual practices due to its strong symbolism and virtues. According to the ma‘alem, ancient purification rituals used a natural mixture of sand and salt, especially for newborns: this material was applied to babies’ legs to benefit from its healing and protective effects. Similarly, constructions made of salt were believed to repel evil spirits and protect against harmful influences.

3.2. The Implementation of Agharf in Traditional Construction

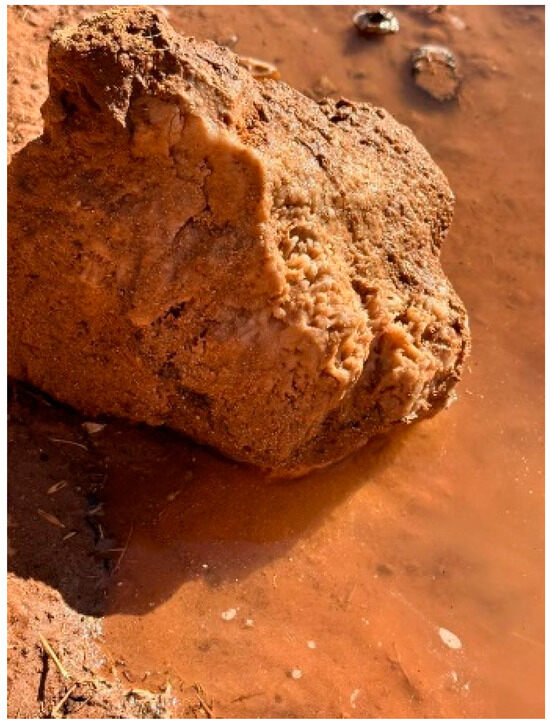

The Agharf technique primarily relies on salt stones, composed of salt crystals mixed with impurities such as sand and clay (Figure 6). Thus, salt is only one component of this complex material.

Figure 6.

Raw block of crystallized salt mixed with natural impurities (Photo by the author).

These large salt pebbles, locally called “Dhelaif el malh” in the plural and “Dhelf” in the singular, most likely derive their name from the classical Arabic word “ظِلْف”, meaning “animal hoof”, and may thus refer to the specific shape of these salt blocks. The ma’alam, however, considers the word to be of Berber origin, although the language is no longer spoken today. The ma’alam also commonly uses the expression “Ktayaa el malh” to refer to these blocks, as well as “Ktaa” and “Dhelf”, which locally mean “to cut”, referring to the process of shaping or extracting the blocks into their final form.

These salt blocks are extracted from the sebkha. For the ma’alam, materials like salt stone and salt mortar were easily accessible on-site. They were collected using simple tools such as shovels and picks. The artisans then used buckets or bags to transport the extracted clay and rock salt, typically with the help of pack animals. This collection typically took place at specific times of the year, usually after the rainy season, when the earth became more malleable. The construction technique uses cut blocks of salt stone as the main elements of the wall.

While artisans describe in detail the composition of the Agharf mixture, they only vaguely provide details on the masonry technique. This technique consists of directly integrating raw salt blocks into the thickness of the wall, without precise wedging. A generously applied salt-clay mortar fills the gaps and coats the surface to protect and stabilize the structure [9]. The blocks were bonded together with mortar made of earth, sand, and brackish water drawn from the sebkha. The experience of artisans reveals that the drying of salt contributes to the solidification of walls. Although sensitive to water, salt interacts with humidity by slightly dissolving on the surface and then, as it dries, hardens and strengthens the wall structure. The artisans go on to explain that during the process, after rain, the salts in the material rise to the surface and crystallize, creating a fine white, powdery layer. It is this accumulation of salt that strengthens the material by improving the bonds between the clay particles (Figure 7). This particular phenomenon gives the material a characteristic texture, marked by irregularities and reliefs, making it immediately recognizable.

Figure 7.

Manifestation of salt efflorescence on the surface of the ksar walls in Tamentit (Photo by the author).

To complete the mixture, clay extracted from areas outside the saline zones is added to reduce the solubility of this assembly and its vulnerability to humidity. This adjustment, based on the empirical knowledge of artisans, enhances the cohesion of the mortar and ensures greater durability of the constructions.

This less saline clay reduces the risk of moisture infiltration and limits its harmful effects on the salt contained in the structure. Stones of varying shapes and sizes are then incorporated to give cohesion and strength to the whole. The clay is extracted from a specific place called “Hefrat Etine”, or in Berber, “Tegazet El Tine”. The yellow clay is preferred for its exceptional quality and its traditional value within the community. It was primarily used for soap making, while also being employed in the construction of many ksour. Yellow clay has an additional practical advantage by reducing the risk of stains, unlike red clay, whose bright color and tendency to leave marks limited its use and made it less noble for the construction of ksour. However, its availability made it ideal for practical and inexpensive constructions, such as garden fences. Finally, yellow clay naturally combines with salt to the point that, as described by the ma’alem, these two materials seem to merge into a single substance. Its color and ability to better reflect light made it an ideal material for living spaces. Once all the materials are gathered, they are assembled on-site and bonded together to form robust walls.

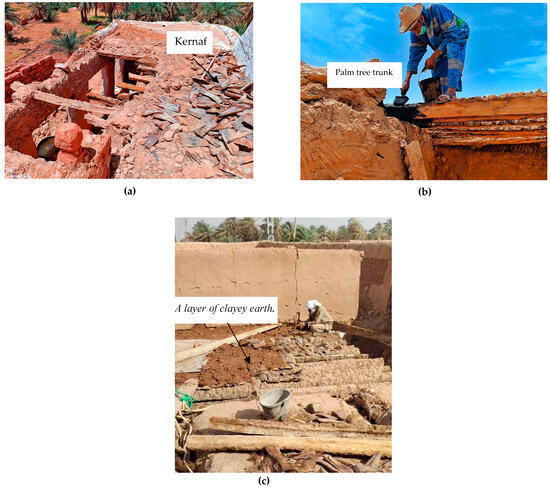

3.3. Traditional Practices of Roof Conservation and Construction Using Agharf

Artisans, as part of their initiatives, explore various approaches to ensure the longevity of palm and earth roofs, as highlighted. The roof framework made of palm trees consists of a primary supporting framework, solid and lightweight, made up of split and further split palm trunks, resulting in four beams, pieces the length of the trunk and with a quarter-circle cross-section. This structure is completed with the addition of palm-tree petioles, commonly called “kernaf,” which fill the gaps between the joists. The earth, thanks to its insulating properties, stabilizes the interior temperature and enhances the overall waterproofing of the roof (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Renovation of the terrace of the Tamentit mosque: (a) Placement of palm tree trunks and kernaf; (b) Preventive treatment of palm wood with linseed oil; (c) Application of a layer of soil after the complete installation of the supports (trunks and kernaf) (Photos by El Idrissi.A).

Regular maintenance ensures the waterproofing of the roof, allowing the palm wood to withstand the test of time. However, when exposed to moisture, the wood becomes vulnerable to termites. To prevent this, preventive methods are put in place. One such method is the application of linseed oil during reconstruction work (Figure 8b). Another solution involves placing Agharf at the top of the walls, typically at the junction between the walls and beams, thus bringing them into direct contact with the wood. The presence of salt prevents termites from settling. Thanks to its presence, salt prevents the installation of termites and, at the same time, limits the punching effect, thus reducing the risk of bending of the beams under the weight of the roof. Another method consists of soaking the palm wood in salty water; the salt prevents termite development and thus extends the lifespan of the palm wood. Builders could naturally source salty water from aquifer springs near the ksar.

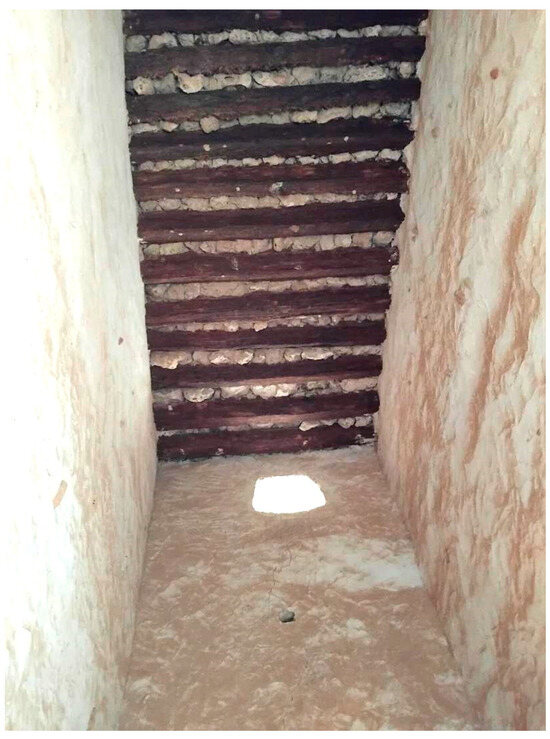

While Agharf is primarily used for protecting roofs, it can also be used to build a roof, as an alternative to petioles to fill the gaps between palm joists. This is what a ma‘alem explained, noting that this technique is applied when the quality of materials is prioritized, as is the case for certain dwellings belonging to tribal leaders or possibly mosques. This solution was especially used for constructions near gardens, where there may be relative humidity, making them more vulnerable to termites. Houses further from gardens favored kernaf, which is appreciated for its ease of access and implementation, unlike saltstone, which is heavier and more complicated to extract (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Roof made of palm wood and Agharf, covered with a layer of salt-impregnated soil (Photos by El Idrissi. S).

3.4. Constraints and Challenges Related to the Exploitation of Agharf

However, difficulties arise in the use and exploitation of saltstone. One major challenge is managing the durability of the walls, which can quickly discourage the use of the material. Several buildings in Tamentit, now abandoned, show significant deterioration due to a lack of maintenance, as one craftsman testified: “Salt is a living material; it reacts to moisture and climate. Without maintenance, the walls absorb water from the air or through rain infiltration, and over time, this dissolves the salt and creates holes. If we had done what was needed, like applying a layer of clay to seal cracks as soon as they appear, the wall would still be solid. But once the wind, water, and time act on it, the wall weakens and eventually crumbles”.

Thus, the effect of moisture on saltstone leads to its gradual dissolution on the surface, forming cavities that widen over time (Figure 10). Preventive maintenance, such as applying clay mortar, is therefore essential to protect and reinforce the weakened areas.

Figure 10.

The formation of cavities in the Agharf due to saline erosion (Photo by the author).

Access to materials is not without difficulties, as artisans prefer local materials by reusing earth from ruins or extracting it from nearby gardens and old ditches. However, quarrying Agharf requires trips of nearly 2 km to the sebkha for extraction, which is a significant constraint. During periods when the sebkha did not allow harvesting, access to the material became difficult. This forced artisans to go to the Oued Saoura, located more than 10 km west of Tamentit. The lack of modern tools also complicates the tasks considerably, especially during the winter period.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Results

International initiatives, such as those supported by IUCN and other international projects, illustrate the growing trend towards recognizing the importance of salt as a sustainable material in projects with a strong local identity.

However, the results of this study show that salt rock remains limited in its current use. The artisans interviewed highlighted certain technical difficulties related to its application, particularly in terms of access to materials, transport, and maintenance, which hinder its large-scale deployment.

The interviews conducted with the artisans provided a detailed overview of current practices and the challenges encountered.

Table 3 summarizes the main topics addressed, representative verbatim excerpts, and the key issues identified through the participants’ testimonies.

Table 3.

Analysis of interviews: topics covered, representative verbatim, and identified issues.

4.2. Discussion of Hypotheses

The results show that salt stone is perceived by artisans as a material with interesting technical qualities (durability, termite resistance, thermal comfort). However, its use remains marginal due to logistical constraints (difficult supply, expensive transport) and declining know-how. This hypothesis is therefore partially validated: the potential exists, but its viability remains limited in current conditions. We confirm the existence of a strong symbolic and heritage attachment to this technique, particularly in the context of tourism projects or cultural promotion. However, this anchoring remains fragile and does not yet constitute a driver of widespread transformation of practices. The hypothesis is therefore generally confirmed.

Finally, the results show that the transmission of know-how is currently very limited, essentially oral, and dependent on the presence of Maâlems. Some tourism projects, moreover, promote the valorization of this know-how on an ad hoc basis, but have not yet resulted in continuous transmission or a considerable economic impact on a larger scale. The hypothesis is therefore partially verified but remains conditioned by a specific and limited framework.

4.3. Reflections on the Results

The results of this study reveal that, despite logistical and technical challenges, some artisans have launched initiatives, such as the renovation of guest houses, aimed at preserving and promoting traditional practices as well as local cultural heritage. Thus, builders are rediscovering local resources and techniques, combining know-how, sustainability, and cultural heritage [29]. However, these initiatives are sometimes contested, revealing divergent views on the future of the ksar. The return to the use of salt, on the other hand, still seems hesitant. Discussions with artisans highlighted two key aspects of participatory construction sites. The first is access to economic resources. Earth, clay, and sometimes stone are generally abundant, making their extraction inexpensive and sustainable. Another important aspect is the proximity of materials, which allows for optimized project management. It is therefore not surprising to note that all the treated houses are located near gardens. This is not the case with the Agharf technique, which is hampered by the difficulty of accessing the necessary materials, which complicates its application. In addition, the still rudimentary methods of transporting the materials entail additional costs, and the need for regular maintenance is often too costly for local communities. Other significant challenges have been identified, particularly those related to material harvesting.

Furthermore, although salt rock is associated with certain benefits, particularly in terms of air purification, humidity regulation, and thermal comfort, its actual effects on health remain poorly documented. In addition, exposure to certain health risks has been proven [30]. The health risks for craftsmen are relatively low due to the significant decline in their integration into construction techniques. Today, craftsmen source salt pebbles directly from the sebkhas and occasionally recover them from old construction sites. However, caution remains necessary, particularly due to the risk of contamination of the sebkhas by urban waste.

Several constraints marked the conduct of this study: mobilizing ma’alem and artisans willing to answer our questions proved complex, their availability often being limited by their own professional constraints. In addition, a lack of knowledge about the materials and the variability of their composition was observed. As mentioned previously, young artisans appear not to have benefited from a complete transmission of these traditional skills, which is a significant indicator of the current state of this practice. These limitations underscore the need for in-depth fieldwork and more structured support to carry out such research in an environment where traditional knowledge, although valuable, remains fragile and difficult to document.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the initial hypotheses were largely confirmed: salt stone is indeed a viable alternative to imported materials, strengthening the durability of palm wood roof structures often threatened by termites. Moreover, the return to this construction technique reflects a connection to shared cultural values, positively influencing current practices. Finally, the reinterpretation of ancient structures represents a key leverage for the transmission of traditional knowledge and the development of the tourism economy.

The Agharf, long chosen for its structural and therapeutic qualities, was a response to the climatic constraints and cultural practices of the time. Today, its use has declined to the point of disappearance, replaced by techniques better suited to the evolving needs of the population. More accessible alternatives, such as adobe for occasional construction, and above all, the rise of modern materials, have gradually taken over. Its resurgence now fits into a desire to preserve heritage and improve living conditions through more sustainable tourism. This choice has become established as a response to local realities, taking into account both ecological and economic challenges.

From this perspective, salt stone is mainly used to compensate for the scarcity of wood rather than as a primary construction material. This is why a precise assessment of maintenance, transport, and durability costs remains essential to determine their relevance and ensure their transmission.

That being said, while the technique appears promising, further scientific studies are necessary, as its impacts—particularly on comfort and health—require more in-depth evaluation. While artisans consider this approach relevant for enhancing the durability of constructions or preserving the integrity of traditional dwellings, they also highlight the lack of resources to cover additional costs, implying that this responsibility falls on institutions. In this context, it is crucial for artisans to receive stronger institutional support. This should include improved transmission of knowledge related to Agharf and other traditional construction techniques, as well as continuous technical assistance to evaluate its adaptability and optimize its application. Such an approach would ensure the longevity and efficiency of this technique and reinforce its viability in contemporary practices.

Author Contributions

Data collection was carried out by the N.B.H. During the iterative analysis process, the N.B.H. conducted the initial data analysis, and both authors discussed the results. The N.B.H. led the manuscript writing, while the B.F. provided critical intellectual feedback on the draft and gave final approval for the version to be submitted to the journal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks go first and foremost to the artisans and master artisans who participated in the questionnaire, for their sincerity, availability, and trust. A special mention is given to artisan Boubeker Boumediene, who dedicatedly led the project of rehabilitating the traditional houses of the ksar. We also wish to thank Saleheddine El Idrissi, president of the tourism promotion association, whose invaluable support made the field interviews possible. Finally, my warmest thanks go to Tewfik Guerroudj, “artisan”, urban architect, for his technical guidance and attentive proofreading of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the existing affiliation information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Bortolotto, C. Le trouble du patrimoine culturel immatériel. Terrain Le Patrim. Cult. Immatériel 2011, 26, 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel de l’UNESCO. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/fr/qu-est-ce-que-le-patrimoine-immatériel-00003ar (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Akrich, M. La Construction d’un Système Socio-Technique. Esquisse Pour une Anthropologie des Techniques. In Sociologie de la Traduction; Presses des Mines: Paris, France, 1986; pp. 109–134. Available online: https://books.openedition.org/pressesmines/1195?lang=fr (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Karakul, Ö. Traditional Craftsmanship in Architecture, Conservation and Technology. In Craft, Technology and Design; Oksala, T., Orel, T., Mutanen, A., Friman, M., Lamberg, J., Hintsa, M., Eds.; HAMK e-publications: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360218975_Traditional_Craftsmanship_in_Architecture_Conservation_and_Technology (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Karakul, Ö. Traditional Earthen Architecture: Konya, a Case Study of Intangible Heriage and Local Building Practice. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2023, 14, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derex, M.; Morgan, T.J.H. The Cultural Transmission of Technological Skills. In The Oxford Handbook of Cultural Evolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, E.; Graezer Bideau, F.; Leimgruber, W.; Munz, H. Politiques de la Tradition: Le Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel. In Savoir Suisse; Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes: Lyon, France, 2018; Available online: https://edoc.unibas.ch/68569/1/12131_PolTradition_int_ebook.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Echallier, J.-C. Villages Désertés et Structures Agraires Anciennes du Touat-Gourara (Sahara Algérien); A.M.G.: Paris, France, 1972; pp. 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Battesti, V. De l’habitation aux pieds d’argile, Les vicissitudes des matériaux et techniques de construction à Siwa (Égypte). J. Des Afr. 2006, 76, 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Geboers, E.; Building with Salt in the Desert. An Architectural Engineering Research. Delft 2015. Available online: https://typeset.io/pdf/the-salt-project-356j3ubx9q.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Bassoud, A.; Khelafi, H.; Mokhtari, A.; Bada, A. Bâtiments construits en adobe salin, durabilité centenaire et confort thermique dans un climat désertique. In Proceedings of the NOMAD 2022-4e Conférence Internationale Francophone Nouveaux Matériaux et Durabilité, Montpellier, France, 16–17 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Van Daele, J. Le Sel Sera-t-il le Matériau de Construction du Futur? Renoscripto. 12 January 2023. Available online: https://www.renoscripto.be/fr/article/le-sel-sera-t-il-le-materiau-de-construction-du-futur (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- FELIX-DELUBAC Architectes. Ecolodge I. Architectes-paris.com. 2007. Available online: http://www.felix-delubac-architectes.com/siwa/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Frangeul, L. Construire Avec les Ressources de Proximité, L’exemple des Briques de sel en Bolivie. Ghara. 16 October 2023. Available online: https://www.ghara.fr/construction-briques-de-sel/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Gillett, K. À Dubaï, des Architectes Mettent Leur Grain de sel. Le Courr. L’UNESCO 2024, 1, 26–27. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388574 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Bell, D.; Burney, H. Salt of the Earth: The Past and Future of Building With Brine. Archit. Rev. 23 April 2024. Available online: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/salt-of-the-earth (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Un Nouveau Départ Pour L’oasis Ouled Yahia en Algérie. IUCN. 22 Mars 2022. Available online: https://iucn.org/news/mediterranean/202203/un-nouveau-depart-pour-loasis-ouled-yahia-en-algerie (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Laureano, P. Sahara Jardin Méconnu; Larousse: Paris, France, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, I.A. Some features of salt-architecture in the medieval Sudanic cities: Taghaza in Mali as a model. Afr. J. Econ. Politics Soc. Stud. 2023, 2, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gandreau, D.; Offroy, T. La rétro-ingénierie des cultures constructives locales pour répondre aux grands enjeux globaux actuels: L’expérience de CRAterre. Cult. Rech. 2024, 146, 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ritimo. CDTM 34. Carte et Repères sur l’Algérie. Algérie: Le Défi D’une Nécessaire Transition Energétique. 7 January 2016. Available online: https://www.ritimo.org/Carte-et-reperes-sur-l-Algerie (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Frey, J.-P. Adrar et l’urbanisme ou la sédentarisation erratique des oasis du Touat. Les Cah. D’emam 2014, 22, 7–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.G.P. Les Oasis Sahariennes (Gourara-Touat-Tidikelt). Volume 1. L’Imprimerie Algérienne; Nabu Press: London, UK, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Oliel, J. Les Juifs au Sahara. Encyclopédie Berbère; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2004; pp. 3962–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capot-Rey, R. Irrigation et Structure Agraire à Tamentit. Bulletin de l’Association de Géographes Français, 39ᵉ année, n°307–308. pp. 223–233, Paris. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/bagf_0004-5322_1962_num_39_307_5607 (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Cartwright, M.; Le Commerce du Sel de L’ancienne Afrique de L’Ouest. Traduit par B. Étiève-Cartwright. World History Encyclopedia. 6 Mars 2019. Available online: https://www.worldhistory.org/trans/fr/2-1342/le-commerce-du-sel-de-lancienne-afrique-de-louest/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Fiche Descriptive sur Les Zones humides Ramsar: Oasis de Tamantit et Sid Ahmed Timmi. Ramsar Sites Information Service. 28 January 2001, pp. 1–9, Gland, Switzerland. Available online: https://rsis.ramsar.org/RISapp/files/RISrep/DZ1061RISformer_161020.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Guerroudj, T. La Ville Expliquée. Le Dictionnaire de L’urbanisme; Alternatives Urbaines: Alger, Algérie, 2024; pp. 278–279. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, E.M. Construire à Partir de la Tradition: Matériaux et Méthodes Locaux Dans L’architecture Contemporaine, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INRS. Tableaux des Maladies Professionnelles: Régime Général Tableau 78; INRS: Villers-lès-Nancy, France, 1983; Available online: https://www.inrs.fr/publications/bdd/mp/tableau.html?refINRS=RG%2078 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).