Abstract

This article describes the Heritage Sustainability Index (HSI), a benchmarking tool that draws on a series of key indicators to rate company actions as they relate to the protection of cultural heritage. The purpose of the HSI is to provide an independent framework for lenders, borrowers, and civil society, including Indigenous Peoples, to evaluate corporate safeguard policies and practices related to cultural heritage, enabling informed decision making. Given their importance and influence, the HSI focuses on the practices of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs), which were chosen to represent a baseline for comparison across all industry sectors. The HSI’s indicators (n = 12) and sub-indicators (n = 48) were successful in illustrating the variability that exists among the G-SIBs. Corporations with an HSI value below the upper quartile of the distribution should take steps to enhance their cultural heritage safeguard practices. This is crucial because scores below this value reflect weak practices, indicating higher financial and reputational risk exposures and poor outcomes for cultural heritage. By focusing on improving their HSI values, these corporations can better mitigate potential risks and enhance their overall sustainability profile. The success and longevity of the HSI will depend on industry goodwill and the perceived risk that cultural heritage poses to corporate financial performance and reputation. Given the potential financial and reputational damage from a significant failure in cultural heritage stewardship, corporations are expected to recognize these advantages and find it an easy decision to support the adoption of the HSI.

1. Introduction

As investors and corporations increasingly apply environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria to financial decisions, there is a need to benchmark corporations against industry peers to provide investors, stakeholders, and Indigenous Peoples1 with confidence that industry-leading good practices are being followed. While environmental and governance considerations are generally well represented in ESG assessments, social considerations, especially cultural heritage, require further development. Cultural heritage is a complex and often politically sensitive issue, with its definition and interpretation varying widely depending on the perspective [1]. For the purposes of this article, cultural heritage is broadly defined to encompass both tangible and intangible forms, as outlined in Welch [2] (p. 1).

Events such as Rio Tinto’s damage to two rockshelter sites in Juukan Gorge, Western Australia, containing evidence of human occupation spanning over 46,000 years, have elevated cultural heritage from what may have previously been a consideration with a limited profile and few adverse consequences for project sponsors to a matter of significant concern to both corporate executives and investors alike [3,4,5] (see Oestigaard [6] for an African example involving intangible cultural heritage). In the wake of the Juukan Gorge incident in May 2020, many major mining corporations have revised their cultural heritage safeguard policies, strengthened internal accountability, and sought the expertise of subject matter experts for guidance. Although these safeguard policies are often not made public, some companies have shared them (see, for example, [7,8,9]).

In contrast to the events described in the preceding paragraph, corporate actions that prioritize safeguarding cultural heritage can have a positive impact on a corporation’s reputation, which in turn can enhance its financial performance and long-term sustainability. One such example is Bloomberg L.P.’s European headquarters in London, which incorporates a temple dedicated to the Roman god Mithras, preserved in its original setting seven metres below the modern street level. Completed in 2017, the London Mithraeum Bloomberg SPACE is open to the public, showcasing the temple, a selection of Roman artifacts, and a space for contemporary art exhibitions [10].

In light of the risks and opportunities described above, the risk management function in financial institutions monitors a variety of risks, including credit, reputational, legal, environmental, and social risks. Some of these risks are tied to regulatory requirements, while others are part of internal processes designed to manage the company’s assets and liabilities. Investment decisions are evaluated to ensure alignment with internal risk management frameworks and appetite, typically structured in three levels. At the first level, relationship managers consult internal safeguard policies to identify and assess risks in proposed transactions, including the potential effects on cultural heritage and the customer’s ability to manage them. If elevated risks are identified, the transaction is escalated to a risk committee for further review. For significant reputational, environmental, or other risks, the transaction may be referred to the executive team for final consideration. Subject matter experts may also be consulted during the risk evaluation process.

At present, there are no ratings agencies or indices that comprehensively consider cultural heritage as a material risk to a company’s financial performance, reputation, or long-term sustainability. Dominant sustainability reporting standards, such as those offered by the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board [11] and the Global Reporting Initiative [12], are largely silent on cultural heritage, with only limited mentions in the Global Reporting Initiative sustainability reporting framework. Similarly, cultural heritage is not addressed in indices offered by commercial ESG rating agencies such as MSCI Inc. [13]. The Envision Rating System for Sustainable Infrastructure [14] and the proposed Cultural Heritage Assessment Tool [15] offer heritage indicators that are designed to evaluate projects but not corporate policies.

In response, this article demonstrates that it is possible to create an index that measures variability in company policies and practices related to cultural heritage safeguards. It introduces the Heritage Sustainability Index (HSI), a benchmarking tool that uses a series of key indicators to evaluate company actions related to the protection of cultural heritage. The HSI provides an independent framework for lenders, borrowers, and civil society, including Indigenous Peoples, to assess corporate safeguard policies and practices related to cultural heritage, enabling informed decision making. For example, can a prospective lender be confident that the recipient of the funds will adhere to internationally recognized good practices for the protection of cultural heritage, thereby safeguarding both the lender’s investment and reputation?

Since the article focuses on currently adopted practices, it does not evaluate the quality of, nor offer recommendations for improving, corporations’ existing cultural heritage safeguard policies and practices. Future case studies could explore this area. Furthermore, as this paper focuses on the private sector, the role of government agencies is not discussed in detail, as compliance with the legislation, policies, and guidelines of host nations is assumed. Corporations are not confined to these regulatory requirements and may choose to adopt additional measures beyond compliance to further safeguard cultural heritage.

This article demonstrates that the HSI indicators (n = 12) and sub-indicators (n = 48) effectively highlight the variability that exists among corporations. Corporations with an HSI value below the upper quartile of the distribution should take steps to enhance their cultural heritage safeguard practices. Scores below this threshold indicate weak practices, which translate to increased financial and reputational risks and negative outcomes for cultural heritage. By prioritizing improvements in their HSI values, corporations can reduce these risks and strengthen their overall sustainability profiles. The HSI offers significant benefits to industry, and given its low cost to sustain relative to potential financial and reputational risks of a major failure in cultural heritage stewardship, corporations are likely to recognize these advantages and find it an easy decision to adopt the HSI. A more detailed discussion of these benefits can be found in Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

The HSI draws on earlier research that examined the cultural heritage management practices of 25 major private sector banks [16] by focusing on the practices of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs), a group of 29 financial institutions whose systemic risk profile is deemed to be of such importance that a bank’s failure would trigger a wider financial crisis and threaten the global economy. These banks are colloquially referred to as “too big to fail”, and given their importance and influence, they were chosen to represent a baseline for comparison across all industry sectors. The Financial Stability Board’s list of G-SIBs is published annually in late November (Table 1) [17].

Table 1.

2023 Global Systemically Important Banks and national origin.

Research by Mason and Ying [16] (p. 7) on the cultural heritage safeguard practices of large private sector banks identified key policy documents and practices that influence the protection of cultural heritage. Building on this earlier work and select declarations, conventions, and initiatives from the International Finance Corporation (IFC); the United Nations (UN); and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), relevant search terms were developed based on prior experience with keyword searches, including all common permutations of terminology relevant to this topic. Some search terms (e.g., UN) were excluded to reduce the likelihood of generating high numbers of false positives. Additionally, known errors in source document naming conventions (e.g., Sustainability [sic] Development Goals) were included in the keyword list if considered material to the analysis.

Information related to the practices of G-SIBs was derived from English language data that reflect the most recent financial reporting cycle2 and current policies. The search focused exclusively on information that is accessible on corporate websites (online sourced material) and excluded non-public and third-party sources. For documents without a specified publication date, the “last modified” date from its “properties” metadata was adopted as the publication date. Downloaded sources used in the analysis were archived. Exclusively online sources of information (i.e., web pages) were screen captured and archived.

To identify HSI indicators and sub-indicators, a script containing the HSI search terms was applied to the online sourced material using the “exact matches” rule in the Text Search Query function of the NVivo 14 qualitative data analysis software. An iterative qualitative analysis of the results led to the development of mutually exclusive indicators and sub-indicators to capture variability among the G-SIBs (see Section 3).

Using NVivo 14’s Text Search Query function, the HSI search terms were again applied to the online sourced material compiled for each G-SIB to identify indicator and sub-indicator matches. In cases where only G-SIB subsidiaries met indicator requirements, those G-SIBs were treated as if they did not meet the requirement to ensure consistent comparison among G-SIBs. For example, Natixis has a Restricted Activities Policy, but its parent organization, Groupe BPCE, is silent on the indicator. Select indicators were validated with datasets maintained by UNESCO and the Equator Principles Association.

To score the G-SIBs and allow for comparison, the indicators were structured using a point allocation framework with sub-indicators translated to a numeric value and weighted based on their relative importance. Sub-indicators that are the best available option for each indicator were assigned the highest score (1), while scores for weaker options were reduced commensurately (0.9 to 0), resulting in a hierarchy of mutually exclusive sub-indicators. Sub-indicators with a core focus on cultural heritage were more heavily weighted than those with a more general treatment of the topic (Table 2). Similarly, those indicators that create an obligation (e.g., external reporting) receive a heavier weighting than those with non-binding “soft” commitments (see Lilley [18], p. 16).

Table 2.

Indicator scoring matrix example. Each of the 12 indicators is scored in a similar manner, with totals aggregated to form the HSI value for each G-SIB.

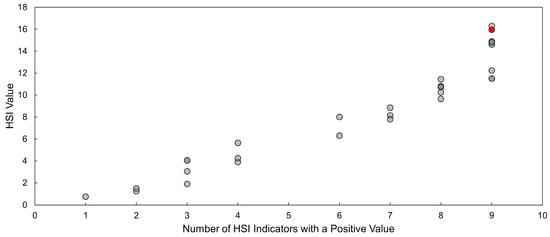

The score can be used independently or presented graphically to compare performance against industry peers (Figure 1), where the x-axis represents the number of HSI indicators with a positive value, while the y-axis shows the “HSI Value”.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of simulated data showing individual company performance (red point) relative to industry peers.

3. Results

HSI indicators (n = 12) reflect corporate practices, the cultural heritage protection measures of leading industry organizations, and global initiatives and conventions that reference cultural heritage. The sub-indicators (n = 48) are derived from the analysis of G-SIB online sourced material. The following outlines the indicators and sub-indicators, with their assigned scores and weights (e.g., 0.8, 2). In this example, 0.8 is the sub-indicator score and 2 is the assigned weight.

3.1. Indicator 1: Cultural Heritage Protection Policy

Corporations may have an explicit policy statement that recognizes the importance of cultural heritage. This indicator does not reflect commitments made through membership in the Equator Principles Association (see Indicator 7).

- 1.1

- Actions are aligned with or guided by IFC Performance Standard (PS) 8 (Cultural Heritage) [19] and include a commitment to protect cultural heritage sites beyond those inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (1, 2);

- 1.2

- Commitment to protect cultural heritage sites beyond those inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (0.9, 2);

- 1.3

- Commitment to safeguard cultural heritage sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (0.5, 2);

- 1.4

- None of the above (0, 1).

3.2. Indicator 2: Prohibited Activities Policy

To protect against commercial and reputational risks, many banks maintain prohibited activity policies3 that apply to all areas of banking, including prohibitions on financing projects that may adversely affect cultural heritage, particularly UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Prohibited activity statements are commonly included in environmental and social policy frameworks or ESG reports.

- 2.1

- Prohibited Activities Policy considers cultural heritage beyond those sites that are inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (1, 2);

- 2.2

- Prohibited Activities Policy only considers cultural heritage sites that are inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (0.5, 2);

- 2.3

- A Prohibited Activities Policy exists, but it does not include cultural heritage as a consideration (0, 1);

- 2.4

- None of the above (0, 1).

3.3. Indicator 3: Restricted Activities Policy

Banks may place financing restrictions on certain industry sectors or activities that they believe have higher commercial and reputational risk profiles. Examples include projects with the potential to adversely affect UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Restricted Activities Policies4 typically require enhanced environmental and social due diligence measures and higher levels of approval to ensure the financed projects are responsibly managed and are consistent with corporate objectives and risk appetite. Like Prohibited Activities Policies, Restricted Activities Policies are often a component of environmental and social policy frameworks and ESG reports. It is common for G-SIBs to reference UNESCO World Heritage Sites in both their Prohibited and Restricted Activities Policies, despite the overlap.

- 3.1

- Restricted Activities Policy exists, and cultural heritage is mentioned in >3 sectors (1, 2);

- 3.2

- Restricted Activities Policy exists, and cultural heritage is mentioned in >1 but <4 sectors (0.8, 2);

- 3.3

- Restricted Activities Policy exists, and cultural heritage is mentioned in 1 sector (0.7, 2);

- 3.4

- Restricted Activities Policy exists, but cultural heritage is not mentioned (0, 1);

- 3.5

- None of the above (0, 1).

3.4. Indicator 4: World Heritage “No-Go” Commitment

Some companies have pledged to protect UNESCO World Heritage Sites by refraining from undertaking or funding activities within sites, their buffer zones, or broader settings, which could damage sites and adversely affect their Outstanding Universal Value [20]. This is known as the World Heritage “no-go” commitment [21]. The process requires companies to inform UNESCO and the World Heritage Committee of their commitment by sending a letter and relevant supporting documents to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre signed by the organization’s Chief Executive Officer, Chair of the Board, or equivalent. The commitment is reviewed by UNESCO for compliance with the spirit of the World Heritage Convention and UNESCO guidance. If accepted, the name of the company is published on the UNESCO database of corporate sector World Heritage commitments [22].

- 4.1

- Corporation’s World Heritage no-go commitment is published in the UNESCO Database of Commitments (1, 2);

- 4.2

- Corporation has not submitted a World Heritage no-go commitment to UNESCO (0, 1).

3.5. Indicator 5: UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Indicators 1 to 4 all speak to UNESCO World Heritage Sites at some level. As the commitments made by each corporation to protect these sites vary, this indicator aggregates the commitments (like with like) and ranks them based on the quality of the safeguard (strongest to weakest), recognizing that a blanket prohibition on development in World Heritage Sites is not the best option.

- 5.1

- Will not participate in financings or investments located within, or near, UNESCO World Heritage Sites without prior consensus from both the relevant government authorities and UNESCO that such activities will not adversely affect the Outstanding Universal Value of the site (1, 2);

- 5.2

- Will not participate in financings or investments located within UNESCO World Heritage Sites without prior consensus from both the relevant government authorities and UNESCO that such activities will not adversely affect the Outstanding Universal Value of the site 0.9, 2);

- 5.3

- Will not participate in financings or investments for projects that threaten UNESCO World Heritage Sites (0.75, 2);

- 5.4

- Financing for natural resource extraction projects within UNESCO World Heritage Sites must consider all applicable risks and whether there is prior consensus from both the relevant government authorities and UNESCO that such activities will not adversely affect the site (0.65, 2);

- 5.5

- Will not participate in financings or investments located in UNESCO World Heritage Sites (0.65, 2);

- 5.6

- Will not participate in financings or investments for projects that have a significant adverse effect on UNESCO World Heritage Natural Sites or World Heritage Sites with high biodiversity value (0, 1);

- 5.7

- No policy for safeguarding UNESCO World Heritage Sites (0, 1).

3.6. Indicator 6: Indigenous Peoples

Corporations are responsible for recognizing the vulnerability of Indigenous Peoples and respecting their right to self-determination, cultural integrity, and the protection of their lands and resources in accordance with international and domestic law. This responsibility extends to the protection of their cultural heritage as described in instruments such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which speaks to the responsibility of States Parties to safeguard tangible and intangible cultural heritage [23]. Not all G-SIBs have a standalone policy or statement on Indigenous Peoples. In some cases, Indigenous rights are acknowledged in other documents such as annual reports, ESG reports, and human rights policies and statements. There is considerable variation within this indicator, with accountability typically residing with the G-SIBs, their suppliers, or their clients.

- 6.1

- Corporation recognizes the importance of cultural heritage to Indigenous Peoples and the goal of achieving the principle of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC5) (1, 2);

- 6.2

- Commitment to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples in alignment with UNDRIP and IFC PS 7 (Indigenous Peoples), including FPIC (0.9, 2);

- 6.3

- Commitment to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples in alignment with UNDRIP, including FPIC (0.85, 2);

- 6.4

- Commitment to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and adoption of IFC PS 7 as a guiding principle (0.75, 2);

- 6.5

- Commitment to obtain FPIC (0.65, 1);

- 6.6

- Commitment to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples (0.5, 1);

- 6.7

- No policy commitment to respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples (0, 1).

3.7. Indicator 7: Equator Principles

The Equator Principles Association is a group of the world’s leading financial institutions that has developed the “Equator Principles,” which is a voluntary credit risk management framework that includes a set of ten principles intended to serve as a common baseline and framework for financial institutions to identify, assess, and manage environmental and social risks when financing projects [24]. Financial institutions that adopt the Equator Principles are known as Equator Principles Financial Institutions (EPFIs).

The Equator Principles incorporate the IFC Performance Standards as their core guidelines, ensuring that projects financed by EPFIs meet the same standards of environmental and social performance [19]. The Equator Principles apply to new projects financed by five financial products: (1) Project Finance Advisory Services, (2) Project Finance, (3) Project-related Corporate Loans, (4) Bridge Loans, and (5) Project-Related Refinance and Project-Related Acquisition Finance. EPFIs will only support these activities if they meet the requirements of Principles 1 to 10—colloquially described as “bankable” projects. Principles 2 through 5 and 7 have the most bearing on the HSI as they describe measures that protect cultural heritage [16].

In some cases, only subsidiaries of G-SIBs are listed as EPFIs. For example, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank Ltd. and Natixis are listed as members of the Equator Principles Association, but their parent organizations, Sumitomo Mitsui FG and Groupe BPCE, are non-members. These G-SIBs are treated as if they are not members of the Equator Principles Association. Similarly, while some non-EPFIs may claim adherence to the Equator Principles (e.g., Bank of America), these corporations are treated as if they do not adhere to the Equator Principles as they are not bound by the conditions of membership in the Equator Principles Association.

- 7.1

- Equator Principles Financial Institution (1, 2);

- 7.2

- Not an Equator Principles Financial Institution (0, 1).

3.8. Indicator 8: International Organization for Standardization 26000

ISO 26000—Social Responsibility [25] was developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in collaboration with representatives from governments, NGOs, industry, consumer groups, and labour organizations. This standard serves as a statement of intent, offering guidance—not requirements—on how businesses and organizations can operate in a socially responsible way. While ISO 26000 is not intended for use in audits, certifications, or compliance statements, it encourages businesses to exceed legal obligations. It emphasizes ethical, transparent behaviour and actions that contribute to societal health and well-being. The standard achieves this by defining social responsibility, translating key principles into actionable steps, and providing examples of best practices for fostering social responsibility [26].

ISO 26000 promotes respect for human rights and the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Regarding cultural heritage, both intangible and tangible forms are addressed. In terms of the former, customs, culture, language, religion, and traditional knowledge are cited as examples. More broadly, under the category of Community Involvement and Development issue 2: Education and culture, related actions and expectations, ISO 26000 states: “An organization should…help conserve and protect cultural heritage, especially where the organization’s activities have an impact on it…” [26] (pp. 64–65). The standard also lists the following UNESCO declaration and conventions as authoritative sources for the recommendations in ISO 26000: Declaration Against the Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage [27], the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage [28], and the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions [29].

- 8.1

- Adoption of ISO 26000 (comprehensive) (1, 2);

- 8.2

- Adoption of ISO 26000, but with a narrow focus (e.g., human rights) that does not address cultural heritage (0.5, 1);

- 8.3

- Superficial reference to ISO 26000 (e.g., “…report prepared with reference to ISO 26000.”) (0.25, 1);

- 8.4

- None of the above (0, 1).

3.9. Indicator 9: Human Rights

The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights describes fundamental human rights to be universally protected. Of relevance to cultural heritage, Article 27(1) introduced the idea that culture is an aspect of human rights [30] (p. 4). It reads, “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits” [31]. Article 15(2) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which is a component of the International Bill of Human Rights [32], states that “The steps taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include those necessary for the conservation, the development and the diffusion of science and culture” [33].

While the UN human rights system has been historically criticized for the emphasis it has placed on civil and political rights rather than economic, social, and environmental rights [34] (p. 5), there has been a growing interest in the cultural dimension of human rights and cultural heritage is now recognized as an essential component of human rights [23,34].

Consistent with Principle 1 of the UN Global Compact, “Businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed human rights” [35]. Most G-SIBs have a Human Rights Policy or issue a Statement on Human Rights, taking guidance from UN instruments and the core conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) [36]. For G-SIBs that lack a standalone policy or statement on human rights, related documents were examined for human rights commitments, including statements on modern slavery and human trafficking6, ESG reports, and annual financial reports.

- 9.1

- Corporation recognizes that cultural heritage is a human right (1, 2);

- 9.2

- Commitment to respect human rights, including references to core UN or ILO human rights instruments (0.75, 1);

- 9.3

- Commitment to respect human rights, but no reference to core UN or ILO human rights instruments (0.5, 1);

- 9.4

- None of the above (0, 1).

3.10. Indicator 10: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) address global challenges, including those related to poverty, inequality, climate, environment, prosperity, and peace and justice. The SDGs were unanimously ratified by UN member states in 2015 and adopted as the foundation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [37]. The framework includes 17 goals and 169 targets to transform the world by 2030 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Although the SDGs [38] make multiple references to the world’s cultural and natural heritage, it is specifically highlighted in Target 11.4: “Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage.” This target is further supported by Indicator 11.4.1, which states:

“Total expenditure (public and private) per capita spent on the preservation, protection and conservation of all cultural and natural heritage, by type of heritage (cultural, natural, mixed and World Heritage Centre designation), level of government (national, regional and local/municipal), type of expenditure (operating expenditure/investment) and type of private funding (donations in kind, private non-profit sector and sponsorship).” [39] (p.13)

Most G-SIBs support the SDGs either generally or in a more selective manner, mapping their activities to the goals and targets best aligned with their business strategy. Accordingly, sustainable development has increasingly been integrated into the guidelines, policies, and strategies of financial institutions.

To demonstrate how private sector risk management practices can contribute to achieving the SDGs, the IFC developed a guide to illustrate how these actions are aligned with the IFC’s ESG Standard [40], comprising the IFC Performance Standards [19] and the IFC Corporate Governance Methodology [41]. This guide maps the IFC’s ESG Standards against the SDGs, targets, and indicators, including five targets that map to cultural heritage: 8.9, 11.4, 12.b, 15.6, and 16.7 (see also Labadi [42]). The HSI employs this framework to assess corporate alignment with the SDGs, focusing on the SDGs that map to the preservation and sustainable use of cultural heritage.

- 10.1

- Corporation makes specific mention of SDG Target 11.4 (strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage) (1, 2);

- 10.2

- Corporation maps its activities to the SDGs that advance cultural heritage indicators as identified by the IFC [40] (0.9, 2);

- 10.3

- Corporation acknowledges and maps its activities with certain SDGs, but not all five that advance cultural heritage indicators as identified by the IFC [40] (0.75, 1);

- 10.4

- Corporation recognizes that some of their activities contribute to the SDGs (0.5, 1);

- 10.5

- No recognition of the SDGs (0, 1).

3.11. Indicator 11: Values Expression

Value expression involves authentically embodying beliefs and principles in everyday actions and interactions, fostering a more positive reflection of core values, including respect for cultural heritage. This is not to be confused with virtue signalling, which simply seeks to enhance image or status rather than genuinely promoting positive change or addressing social issues.

- 11.1

- Significant support (investment in museums, conservation grants, and preservation of heritage sites and objects) (1, 2);

- 11.2

- Modest support (volunteering associated with cultural heritage, recognition of Heritage Day, marketing campaigns and branding that draws on cultural heritage) (0.5, 2);

- 11.3

- None of the above (0, 1).

3.12. Indicator 12: Financial Products

Financial institutions may offer financial products that are specifically designed to support enterprises that safeguard, promote, or sustainably develop cultural heritage. These products may offer lower interest rates or greater flexibility for collateral.

- 12.1

- Offers specialized financial products designed to support cultural heritage (1, 2);

- 12.2

- Does not offer financial products designed to support cultural heritage (0, 1).

4. Analysis

As described above, NVivo 14’s Text Search Query function was used in combination with the HSI keyword search terms to analyze the online sourced material compiled for each G-SIB, identifying matches for both indicators and sub-indicators. These results generated a score out of a possible 24 points (12 indicators, each with a maximum score of 1 and a weighting of 2). Since this article focuses on the methodology of the HSI, individual HSI values for each G-SIB are excluded to maintain emphasis on the approach rather than specific bank performance. Furthermore, providing detailed results for ESG indices is generally discouraged, as it may lead to score manipulation rather than fostering continuous improvement. This approach also helps avoid potential conflicts of interest with the G-SIBs.

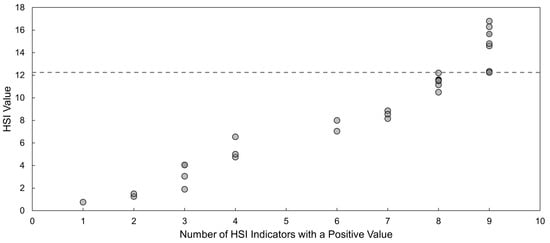

The G-SIB analysis indicates that the indicators and sub-indicators were successful in identifying the variability that exists among the 29 financial institutions, with HSI values ranging from 0.75 to 16.3 (Figure 3). The median value is 8.85, and the mean is 8.86, reflecting a relatively symmetrical distribution. The interquartile range of 7.85, a standard deviation of 4.84, and coefficient of variation of 54.66% indicate a substantial spread of values among the G-SIBs.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot showing heritage sustainability index results. The dashed line demarcates the 4th quartile cut point.

5. Discussion

This article introduces the HSI, a tool that identifies industry leaders and laggards and encourages corporations to make informed decisions regarding cultural heritage protection and sustainable development. The HSI uses a series of key indicators and sub-indicators to evaluate company actions related to cultural heritage safeguards. Given the influence of G-SIBs, they were selected to represent a baseline for comparison across all industry sectors, against which other corporations can be measured as the HSI continues to expand.

The HSI has several practical applications. For corporations, performance can be compared against peers (see Figure 1), with competition within this group driving innovation and improving collective performance with respect to cultural heritage safeguards. These steps will reduce reputational and financial risk exposure, improve outcomes for cultural heritage, and position these companies as attractive to shareholders seeking to invest in good, ethical companies. Corporations with high HSI ratings are more likely to be included in ESG funds.

With lenders, the HSI offers greater awareness of good international practice and will elevate expectations for borrower performance, resulting in more secure financing and increased profit. High-performing borrowers should benefit from a lower cost of capital, reduced insurance premiums [43] (p. 23, 175), and faster, more efficient regulatory reviews.

In the case of civil society, including Indigenous Peoples, the HSI can be used to encourage underperforming corporations to improve their practices for the protection of cultural heritage. It can also inform investment decisions.

For all adopters, the HSI is a significant and valuable addition to ESG assessments for businesses and organizations that finance or implement resource extraction projects (e.g., mining and oil and gas) or involve ground disturbance over a large area, such as transportation infrastructure. Corporations with an HSI value below the upper quartile of the distribution (<12.25) should consider reviewing and enhancing their cultural heritage safeguard practices. This is crucial because scores below this value reflect weak practices, indicating higher financial and reputational risk exposures and poor outcomes for cultural heritage. By focusing on improving their HSI values, these corporations can better mitigate potential risks and enhance their overall sustainability profile.

In its current form, the HSI compares performance among the 29 G-SIBs and allows for the seamless integration of additional, non-G-SIB, financial institutions. To include other industry sectors (e.g., mining, oil and gas, and transportation), HSI variants are proposed, as actions within these sectors can both positively and negatively affect cultural heritage. These variants would build on the existing framework but require some adjustments for cross-sectoral evaluation. For instance, Indicator 12 (Financial Products) would be removed from non-financial HSI variants, and sector-specific organizations would need to be replaced by their industry equivalent. For example, a mining-focused HSI variant would substitute the Equator Principles (Indicator 7) with the International Council of Mining and Minerals’ Mining Principles [44].

6. Conclusions

This article demonstrates that it is possible to create an index that measures the variability in company policies and practices related to cultural heritage safeguards. Future development of the HSI could focus on the variants proposed in this article (e.g., mining, oil and gas). Additionally, corporations would benefit from a critical analysis of the 12 indicators and 48 sub-indicators identified in this study, including recommendations for discarding ineffective indicators and suggestions for potential replacements. Provided that adequate safeguards are implemented to prevent manipulation, future case studies could examine HSI values at the corporate level to explore industry trends and opportunities for improvement. Such studies could determine where high-performing corporations are typically domiciled relative to underperforming ones and whether differences are linked to factors such as ideological perspectives (e.g., state ownership), disclosure requirements, or voluntary actions.

The HSI is a dynamic and adaptive framework that will continuously evolve to reflect the latest ESG trends and data, with updates proposed for annual release. For the HSI to succeed in the long term, industry partners are essential for maintaining the index, refining and adding new indicators, releasing annual updates to the G-SIB baseline, and expanding the HSI beyond the financial sector. Its success and longevity will depend on industry goodwill and the perceived risk that cultural heritage poses to corporate financial performance and reputation. Given the potential financial and reputational damage from a significant failure in cultural heritage stewardship, and considering the substantial benefits it offers to users, corporations are expected to recognize these advantages and find it an easy decision to support the adoption of the HSI.

Funding

The APC was funded by WSP Canada Inc.

Data Availability Statement

Reasonable requests for access to data, materials, and methods used in this study will be considered by the author.

Acknowledgments

This article was strengthened through conversations and correspondence with Scott Fraser, Warren Hill, Erin Hogg, Muriel Joyeux, Maeri Machado, Fergus Maclaren, John Ward, and Marion Werkheiser. David Pokotylo provided critical and timely suggestions that greatly improved the clarity of the paper, and he also assisted with the statistical analysis. Robbin Simão and Iain Begg from The University of British Columbia Office of the Vice-President, Research and Innovation, provided advice and encouragement. The University of British Columbia provided in-kind support. Jeremy Buhler of the UBC Research Commons provided helpful suggestions for coding the Text Search Query function of NVivo 14. Jonathan Skaggs prepared Figure 1 and Figure 3. The author would like to thank the four anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The author Andrew R. Mason is an employee of WSP Canada Inc. (WSP). The APC sponsor had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPCE | Banque Populaire Caisse d’Épargne |

| EPFIs | Equator Principles Financial Institutions |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FPIC | Free, Prior and Informed Consent |

| G-SIB | Global Systemically Important Bank |

| G-SIBs | Global Systemically Important Banks |

| HSI | Heritage Sustainability Index |

| IFC | International Finance Corporation |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| MSCI | Morgan Stanley Capital International |

| PS | Performance Standard |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNDRIP | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| USA | United States of America |

Notes

| 1 | The words Indigenous and Indigenous Peoples are capitalized throughout this article in recognition of their use as identities, not adjectives, in the same way that Canadian and Fijian are capitalized. |

| 2 | Timing can vary, but most banks align their fiscal year with the calendar year, and it is common for annual reports to be released between January and April. Some banks choose fiscal year-ends that do not coincide with the calendar year. These alternative fiscal year-ends can vary based on the bank’s specific requirements, regulatory considerations, or historical practices. For example, a bank might have a fiscal year-end that ends in March, June, or September instead of December. |

| 3 | Also known as Business Restrictions, Prohibited List, Prohibited Business, Prohibited Transactions, Restricted Business, and Restricted Transactions. |

| 4 | Also called Areas of Heightened Sensitivity, Areas of High Caution, Business Escalations, Critical Industrial Activities, High Impact Sectors, Sector Standards, Sensitive and Protected Locations, Sensitive Sector Policies or Guidelines, and Transactions of High Caution. |

| 5 | FPIC is a specific right recognized in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. It allows Indigenous Peoples to give or withhold consent to projects that may affect their lands, territories, and resources. While FPIC is a crucial principle that ensures Indigenous Peoples have a say in projects affecting their lands, it does not necessarily grant them veto power. The principle emphasizes that consent should be sought and obtained freely, prior to project commencement, and with full information provided. However, the implementation of FPIC can vary and, in some cases, projects may proceed without explicit consent, depending on national laws and regulations. |

| 6 | Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom have enacted legislation to prevent slavery and human trafficking in business and supply chains. These laws require corporations to publish statements on their efforts, which may also address other human rights issues. The relevant legislation includes the Commonwealth Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Australia), the Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act (Canada), and the Modern Slavery Act 2015 (UK). These laws aim to increase transparency and accountability in business practices globally. |

References

- Bozoğlu, G.; Smith, L. Series General Co-Editors’ Foreword. In Intangible Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development: Inside a UNESCO Convention; Bortolotto, C., Skounti, A., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. vii–viii. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, J. Cultural Heritage: What Is It? Why Is It Important? Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage Project. 2014. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/sites/default/files/resources/fact_sheets/ipinch_chfactsheet_final.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Reuters. Australian Institutional Investor Sees Heritage Risk Across Mining Industry. 2022. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/australia-mining-indigenous-idINL1N2I30BW (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- ERM. Global Report: Independent Cultural Heritage Management Audit. 2023. Available online: https://cdn-rio.dataweavers.io/-/media/content/documents/news/trending-topics/juukan-gorge/rt-independent-cultural-heritage-management-audit.pdf?rev=36ec358ce0434e2093bcc28d9a1172ab (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Kaur, A.; Lodhia, S.; Lesue, A. Being left behind: Disclosure strategies to manage the Juukan Gorge cave blast. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestigaard, T. A billion-dollar ritual: Spirit appeasement ceremonies behind the Bujagali Dam. In From Aswan to Stiegler’s Gorge: Small Stories About Large Dams; Current African Issues No 66; Oestigaard, T., Beyene, A., Ögmundardóttir, H., Eds.; Nordiska Afrikainsitutet/The Nordic Africa Institute: Upsalla, Sweden, 2019; pp. 63–77. Available online: https://nai.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1357297/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- BHP. Indigenous Peoples Policy Statement. 2022. Available online: https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/ourapproach/operatingwithintegrity/indigenouspeoples/221110_indigenouspeoplespolicystatement_2022 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- BHP. Community and Indigenous Peoples Global Standard. 2024. Available online: https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/ourapproach/governance/240000_communityglobalstandard.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Newmont Corporation. Cultural Heritage Standard. 2021. Available online: https://s24.q4cdn.com/382246808/files/doc_downloads/sustainability/Cultural-Heritage-Standard-2021.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Museum of London Archaeology. Archaeology at Bloomberg. 2017. Available online: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/30/2017/11/BLA-web.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Download SASB Standards. Available online: https://sasb.ifrs.org/standards/download/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Global Reporting Initiative. Consolidated Set of the GRI Standards. 2022. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/how-to-use-the-gri-standards/gri-standards-english-language/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Giese, G.; Nágy, Z.; Lee, L.-E. Deconstructing ESG Ratings Performance: Risk and Return for E, S, and G by Time Horizon, Sector, and Weighting. JPM 2021, 473, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure. Envision Rating System for Sustainable Infrastructure (Version 3.9.7). 2018. Available online: https://sustainableinfrastructure.org/wp-content/uploads/EnvisionV3.9.7.2018.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Mason, A.R.; Martindale, A. Rethinking Cultural Heritage in the International Finance Corporation Performance Standards. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2023, 11, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.R.; Ying, M. Evaluating Standards for Private-Sector Financial Institutions and the Management of Cultural Heritage. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Stability Board. 2023 List of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs). 2023. Available online: https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P271123.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Lilley, I. How Can the G20 Best Protect Cultural Heritage? Policy Recommendations to Strengthen Commitment in Support of Hands-On Action. Antiquities Coalition Think Tank, December. 2024. Available online: https://acthinktank.scholasticahq.com/article/126327-how-can-the-g20-best-protect-cultural-heritage-policy-recommendations-to-strengthen-commitment-in-support-of-hands-on-action (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- International Finance Corporation. IFC Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. 2012. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2012/ifc-performance-standards (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Jokilehto, J. The World Heritage List: What is OUV? Defining the Outstanding Universal Value of Cultural World Heritage Properties. 2008. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/435/1/Monuments_and_Sites_16_What_is_OUV.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. UNESCO Guidance for the World Heritage ‘No-Go’ commitment: Global Standards for Corporate Sustainability. 2022. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000383811 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Database of Commitments. 2024. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-1173-24.xlsx (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Equator Principles Association. The Equator Principles (EP4). 2020. Available online: https://equator-principles.com/app/uploads/The-Equator-Principles_EP4_July2020.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- International Standard 26000; Guidance on Social Responsibility. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Garcia-Ortega, B.; Catalá-Pérez, D.; de-Miguel-Molina, B.; de-Miguel-Molina, M. Corporate Social Responsibility Challenges in the Mining Industry and ISO 26000. In The Strategic Paradigm of CSR and Sustainability; Poveda-Pareja, E., Marco-Lajara, B., Úbeda-García, M., Manresa-Marhuenda, E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 45–73. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-58889-1_3 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Declaration Against the Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage. 2003. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/unesco-declaration-concerning-intentional-destruction-cultural-heritage (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2003. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. 2005. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/convention-protection-and-promotion-diversity-cultural-expressions (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Silverman, H.; Fairchild Ruggles, D. Cultural Heritage and Human Rights. In Cultural Heritage and Human Rights; Silverman, H., Fairchild Ruggles, D., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations. Fact Sheet No. 2 (Rev.1), The International Bill of Human Rights. 1996. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/FactSheet2Rev.1en.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. 1966. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Reynold, M.-A.; Chechi, A. International Human Rights Law and Cultural Heritage. In Cultural Heritage and Mass Atrocities; Cuno, J., Weiss, T.G., Eds.; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 396–410. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/publications/cultural-heritage-mass-atrocities/downloads/pages/CunoWeiss_CHMA_part-4-23-renold-chechi.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations. United Nations Global Compact. 2020. Available online: https://unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- International Labour Organization. C169—Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169). 1989. Available online: https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C169 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Culture for the 2030 Agenda. 2018. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000264687 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- United Nations. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2024. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global-Indicator-Framework-after-2024-refinement-English.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- International Finance Corporation. Advancing UN Sustainable Development Goals Through IFC’s Environmental, Social, and Governance Standards: A Private Sector Guide. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2023/advancing-sdgs-through-ifc-esg-standards (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- International Finance Corporation. IFC Corporate Governance Methodology. 2023. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2023/ifc-corporate-governance-methodology.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Labadi, S. Rethinking Heritage for Sustainable Development; UCL Press: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://uclpress.co.uk/book/rethinking-heritage-for-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Kousky, C. Understanding Disaster Insurance: New Tools for a More Resilient Future; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ICMM Mining Principles. 2024. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/mining-principles/mining-principles.pdf?cb=59962 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).